Chapter 6 Digital Design and Computer Architecture 2

![Accessing Arrays // C Code int array[5]; array[0] = array[0] * 2; array[1] = Accessing Arrays // C Code int array[5]; array[0] = array[0] * 2; array[1] =](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/91b4629b1b7b3ed4fff3b8edaf659558/image-77.jpg)

![Accessing Arrays // C Code int array[5]; array[0] = array[0] * 2; array[1] = Accessing Arrays // C Code int array[5]; array[0] = array[0] * 2; array[1] =](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/91b4629b1b7b3ed4fff3b8edaf659558/image-78.jpg)

![Arrays using For Loops // C Code int array[1000]; int i; for (i=0; i Arrays using For Loops // C Code int array[1000]; int i; for (i=0; i](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/91b4629b1b7b3ed4fff3b8edaf659558/image-79.jpg)

- Slides: 135

Chapter 6 Digital Design and Computer Architecture, 2 nd Edition David Money Harris and Sarah L. Harris Chapter 6 <1>

Chapter 6 : : Topics Introduction Assembly Language Machine Language Programming Addressing Modes Lights, Camera, Action: Compiling, Assembling, & Loading • Odds and Ends • • • Chapter 6 <2>

Introduction • Jumping up a few levels of abstraction • Architecture: programmer’s view of computer – Defined by instructions & operand locations • Microarchitecture: how to implement an architecture in hardware (covered in Chapter 7) Chapter 6 <3>

Assembly Language • Instructions: commands in a computer’s language – Assembly language: human-readable format of instructions – Machine language: computer-readable format (1’s and 0’s) • MIPS architecture: – Developed by John Hennessy and his colleagues at Stanford and in the 1980’s. – Used in many commercial systems, including Silicon Graphics, Nintendo, and Cisco Once you’ve learned one architecture, it’s easy to learn others Chapter 6 <4>

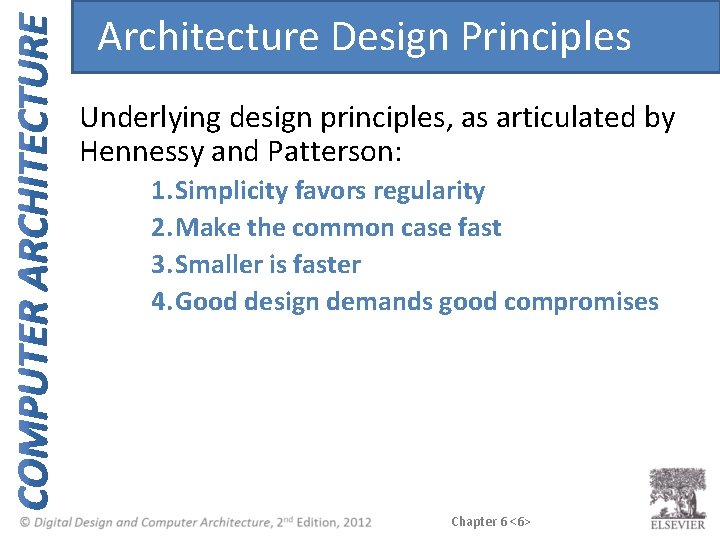

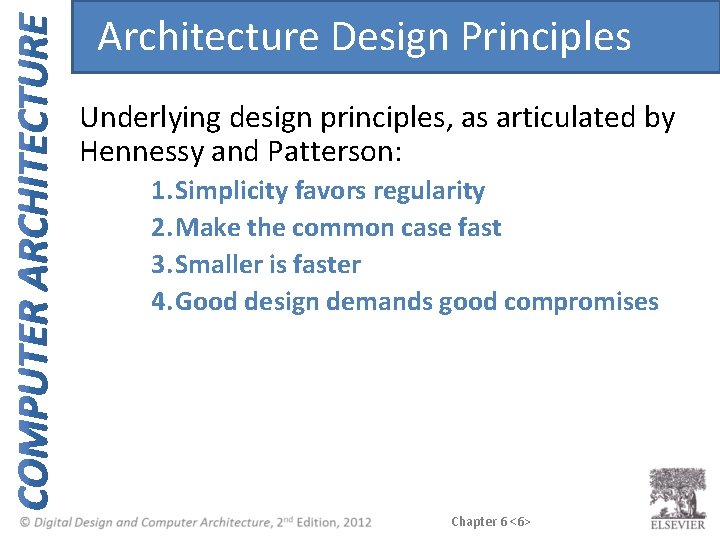

John Hennessy • President of Stanford University • Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at Stanford since 1977 • Coinvented the Reduced Instruction Set Computer (RISC) with David Patterson • Developed the MIPS architecture at Stanford in 1984 and cofounded MIPS Computer Systems • As of 2004, over 300 million MIPS microprocessors have been sold Chapter 6 <5>

Architecture Design Principles Underlying design principles, as articulated by Hennessy and Patterson: 1. Simplicity favors regularity 2. Make the common case fast 3. Smaller is faster 4. Good design demands good compromises Chapter 6 <6>

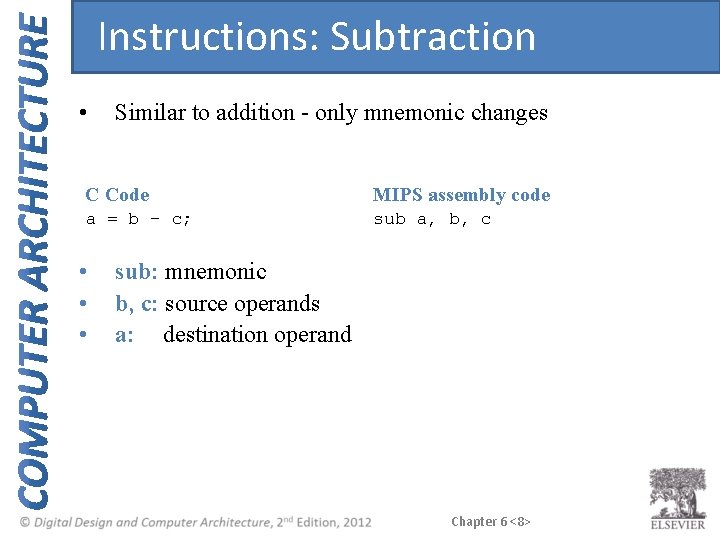

Instructions: Addition C Code MIPS assembly code a = b + c; add a, b, c • add: mnemonic indicates operation to perform • b, c: source operands (on which the operation is performed) • a: destination operand (to which the result is written) Chapter 6 <7>

Instructions: Subtraction • Similar to addition - only mnemonic changes C Code MIPS assembly code a = b - c; sub a, b, c • • • sub: mnemonic b, c: source operands a: destination operand Chapter 6 <8>

Design Principle 1 Simplicity favors regularity • Consistent instruction format • Same number of operands (two sources and one destination) • Easier to encode and handle in hardware Chapter 6 <9>

Multiple Instructions • More complex code is handled by multiple MIPS instructions. C Code MIPS assembly code a = b + c - d; add t, b, c sub a, t, d # t = b + c # a = t - d Chapter 6 <10>

Design Principle 2 Make the common case fast • MIPS includes only simple, commonly used instructions • Hardware to decode and execute instructions can be simple, small, and fast • More complex instructions (that are less common) performed using multiple simple instructions • MIPS is a reduced instruction set computer (RISC), with a small number of simple instructions • Other architectures, such as Intel’s x 86, are complex instruction set computers (CISC) Chapter 6 <11>

Operands • Operand location: physical location in computer – Registers – Memory – Constants (also called immediates) Chapter 6 <12>

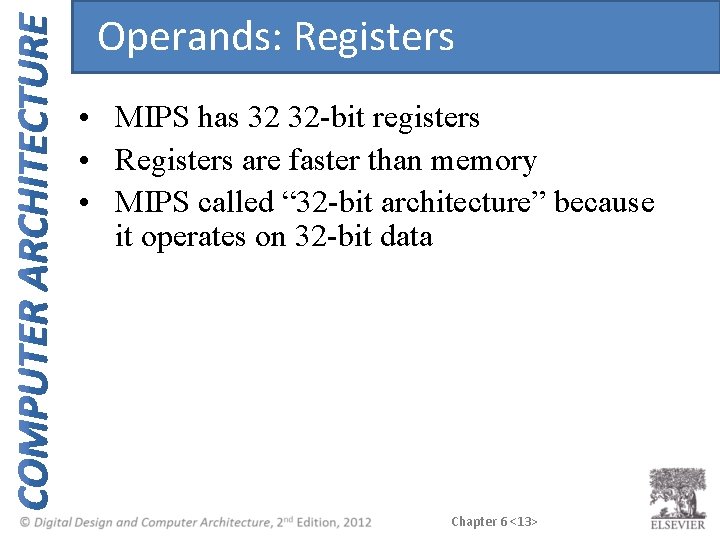

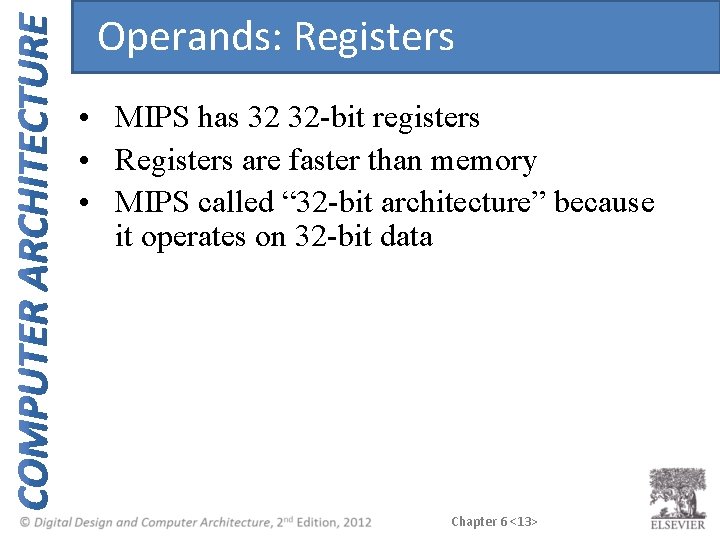

Operands: Registers • MIPS has 32 32 -bit registers • Registers are faster than memory • MIPS called “ 32 -bit architecture” because it operates on 32 -bit data Chapter 6 <13>

Design Principle 3 Smaller is Faster • MIPS includes only a small number of registers Chapter 6 <14>

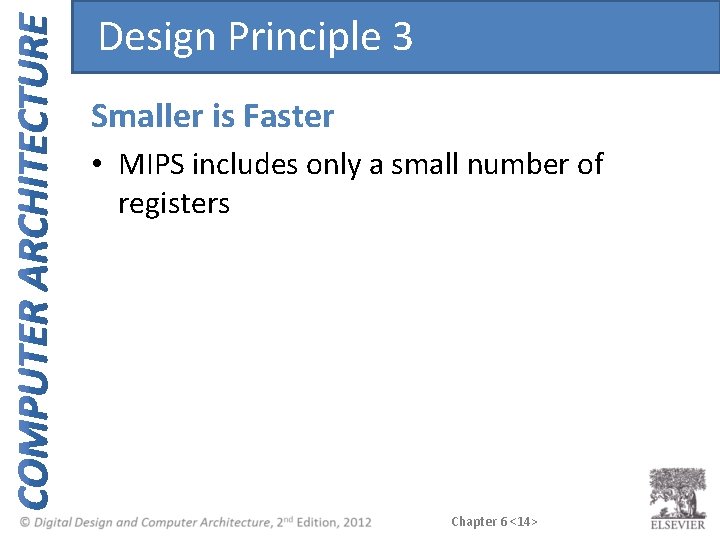

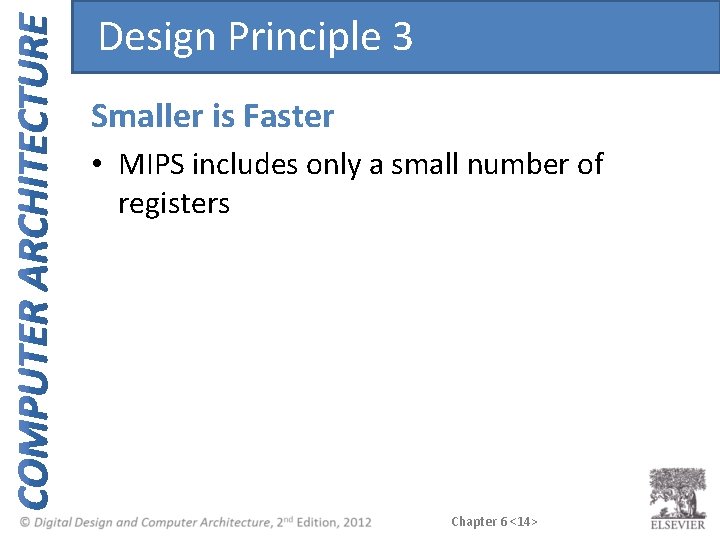

MIPS Register Set Name $0 Register Number Usage 0 the constant value 0 $at 1 assembler temporary $v 0 -$v 1 2 -3 Function return values $a 0 -$a 3 4 -7 Function arguments $t 0 -$t 7 8 -15 temporaries $s 0 -$s 7 16 -23 saved variables $t 8 -$t 9 24 -25 more temporaries $k 0 -$k 1 26 -27 OS temporaries $gp 28 global pointer $sp 29 stack pointer $fp 30 frame pointer $ra 31 Function return address Chapter 6 <15>

Operands: Registers • Registers: – $ before name – Example: $0, “register zero”, “dollar zero” • Registers used for specific purposes: • $0 always holds the constant value 0. • the saved registers, $s 0 -$s 7, used to hold variables • the temporary registers, $t 0 - $t 9, used to hold intermediate values during a larger computation • Discuss others later Chapter 6 <16>

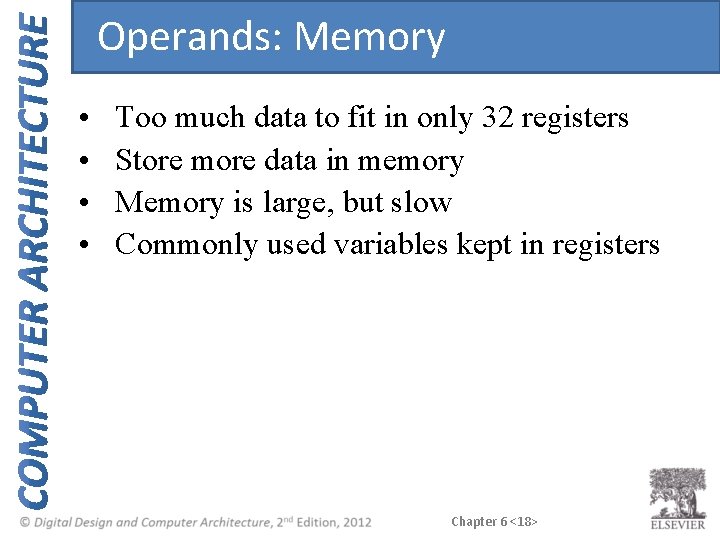

Instructions with Registers • Revisit add instruction C Code MIPS assembly code a = b + c # $s 0 = a, $s 1 = b, $s 2 = c add $s 0, $s 1, $s 2 Chapter 6 <17>

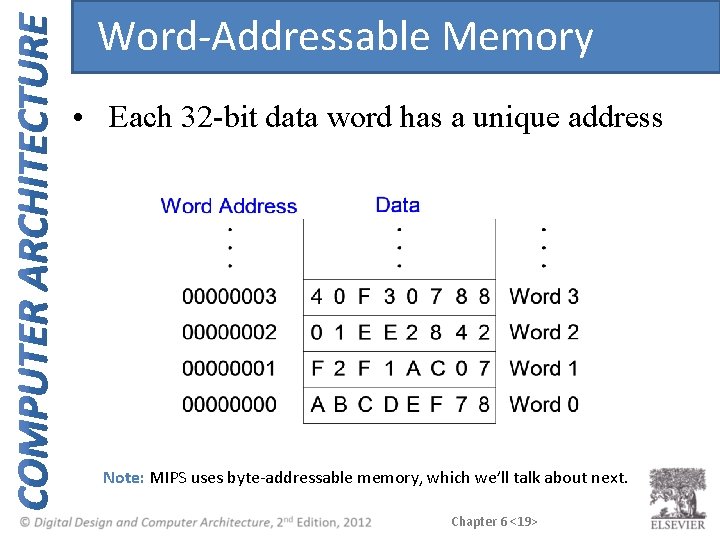

Operands: Memory • • Too much data to fit in only 32 registers Store more data in memory Memory is large, but slow Commonly used variables kept in registers Chapter 6 <18>

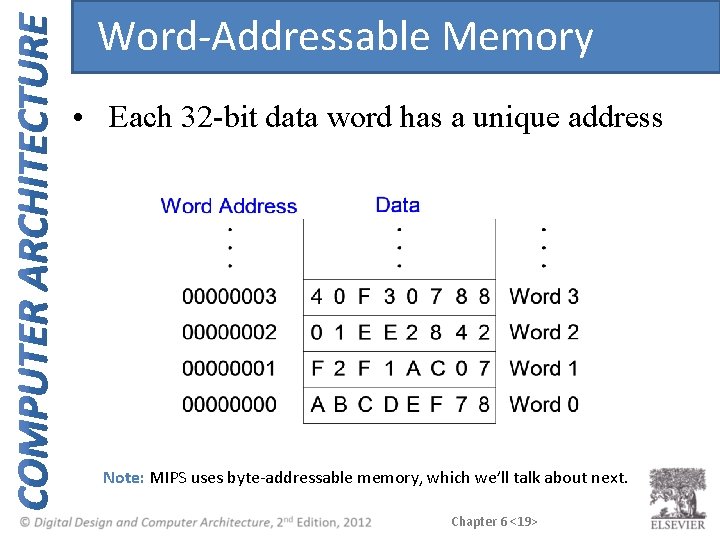

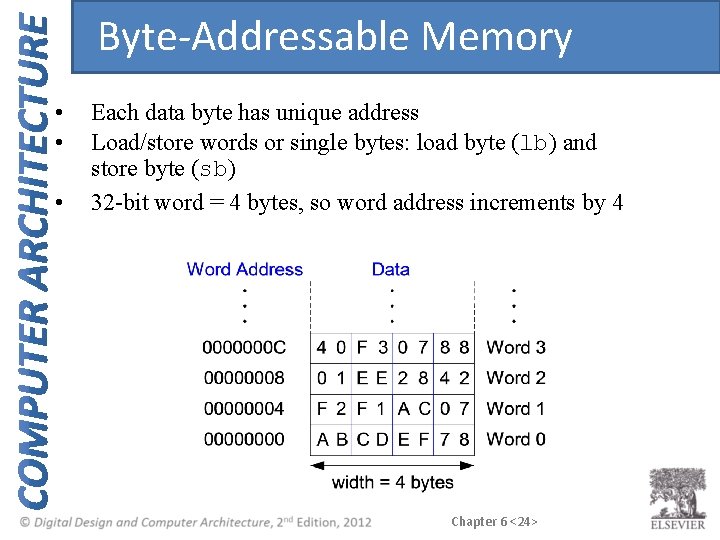

Word-Addressable Memory • Each 32 -bit data word has a unique address Note: MIPS uses byte-addressable memory, which we’ll talk about next. Chapter 6 <19>

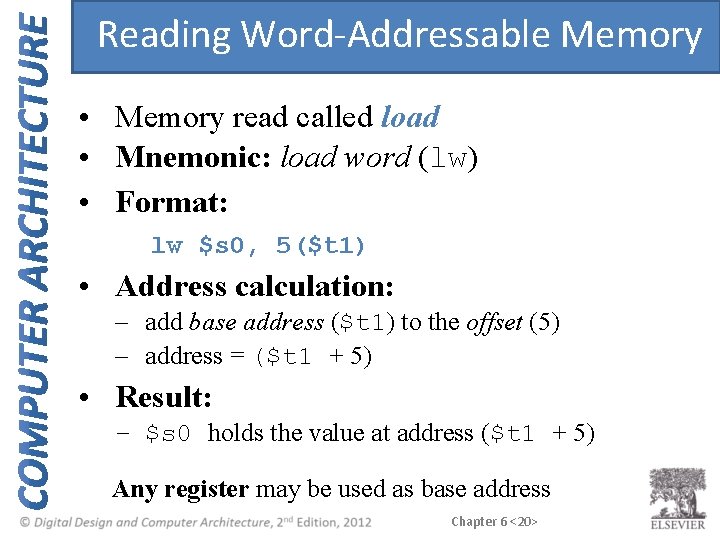

Reading Word-Addressable Memory • Memory read called load • Mnemonic: load word (lw) • Format: lw $s 0, 5($t 1) • Address calculation: – add base address ($t 1) to the offset (5) – address = ($t 1 + 5) • Result: – $s 0 holds the value at address ($t 1 + 5) Any register may be used as base address Chapter 6 <20>

Reading Word-Addressable Memory • Example: read a word of data at memory address 1 into $s 3 – address = ($0 + 1) = 1 – $s 3 = 0 x. F 2 F 1 AC 07 after load Assembly code lw $s 3, 1($0) # read memory word 1 into $s 3 Chapter 6 <21>

Writing Word-Addressable Memory • Memory write are called store • Mnemonic: store word (sw) Chapter 6 <22>

Writing Word-Addressable Memory • Example: Write (store) the value in $t 4 into memory address 7 – add the base address ($0) to the offset (0 x 7) – address: ($0 + 0 x 7) = 7 Offset can be written in decimal (default) or hexadecimal Assembly code sw $t 4, 0 x 7($0) # write the value in $t 4 # to memory word 7 Chapter 6 <23>

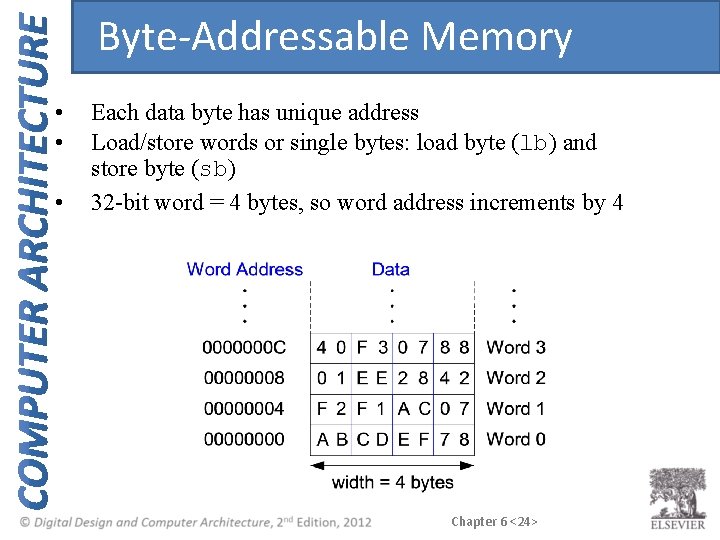

Byte-Addressable Memory • • • Each data byte has unique address Load/store words or single bytes: load byte (lb) and store byte (sb) 32 -bit word = 4 bytes, so word address increments by 4 Chapter 6 <24>

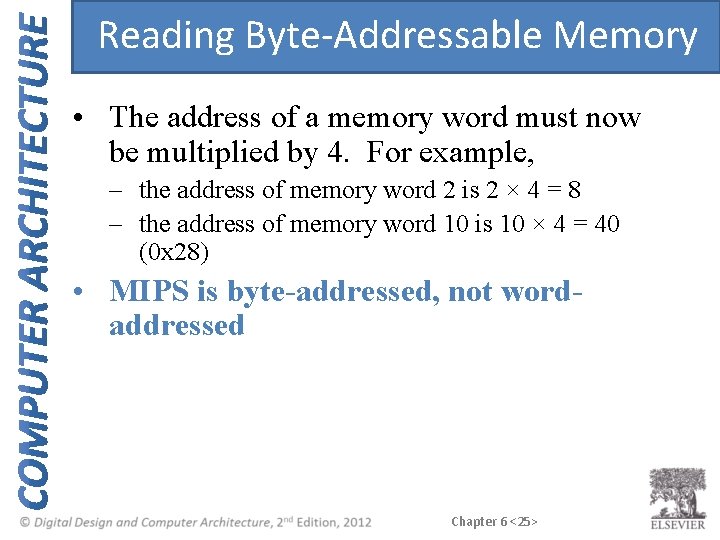

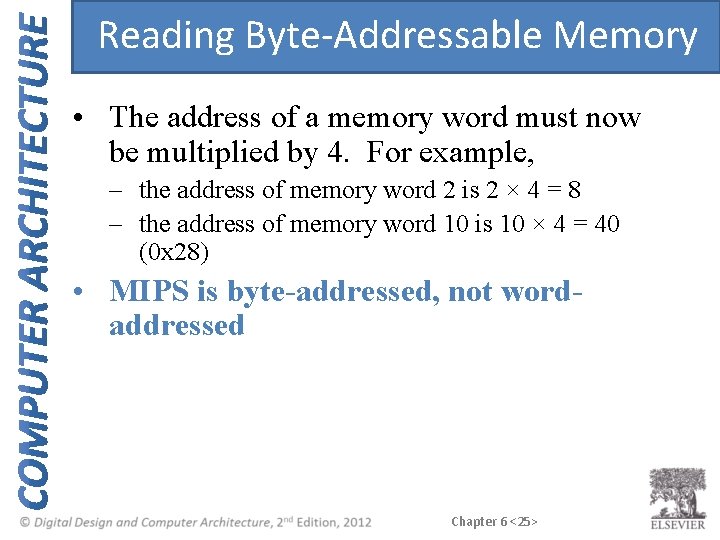

Reading Byte-Addressable Memory • The address of a memory word must now be multiplied by 4. For example, – the address of memory word 2 is 2 × 4 = 8 – the address of memory word 10 is 10 × 4 = 40 (0 x 28) • MIPS is byte-addressed, not wordaddressed Chapter 6 <25>

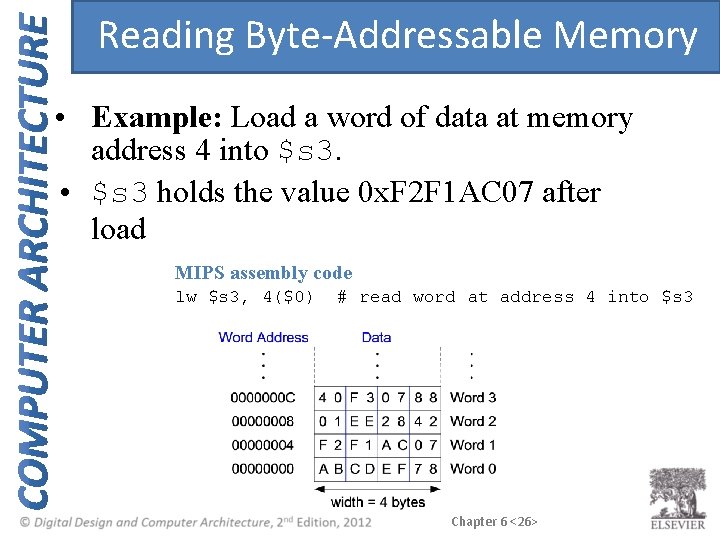

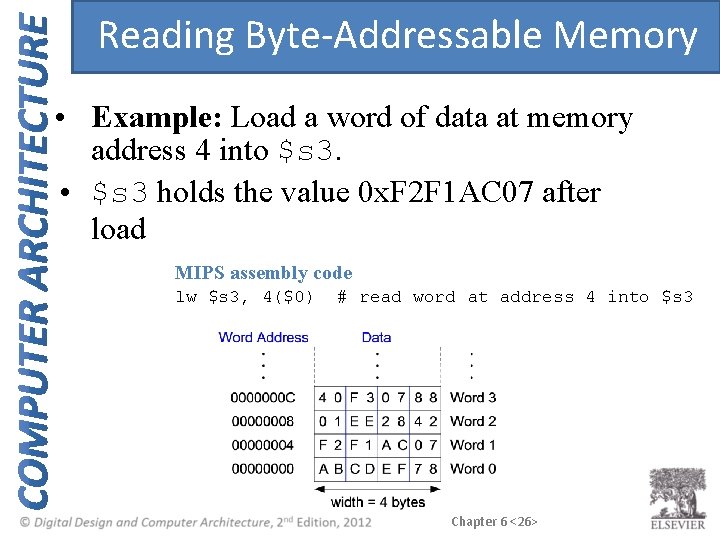

Reading Byte-Addressable Memory • Example: Load a word of data at memory address 4 into $s 3. • $s 3 holds the value 0 x. F 2 F 1 AC 07 after load MIPS assembly code lw $s 3, 4($0) # read word at address 4 into $s 3 Chapter 6 <26>

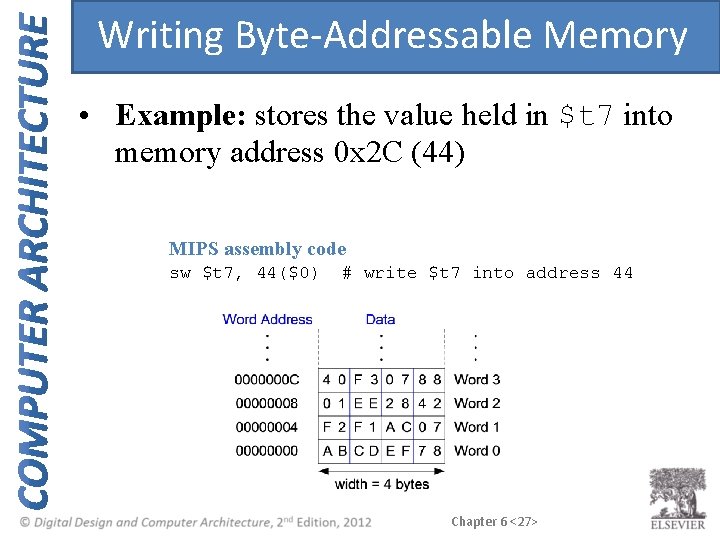

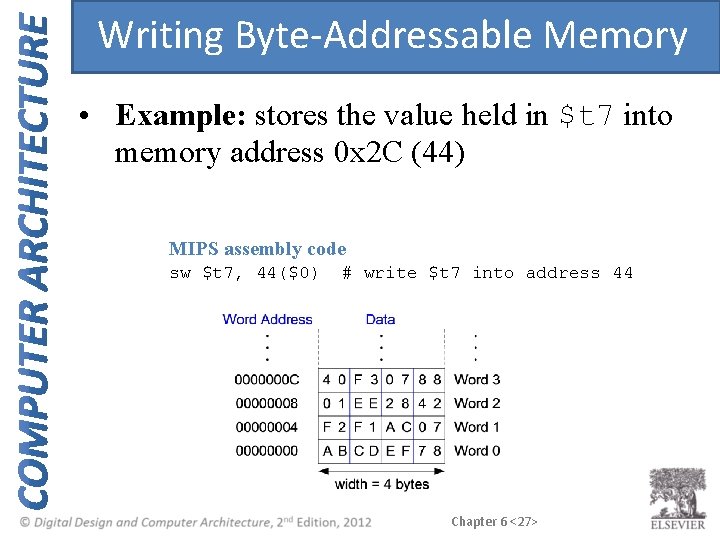

Writing Byte-Addressable Memory • Example: stores the value held in $t 7 into memory address 0 x 2 C (44) MIPS assembly code sw $t 7, 44($0) # write $t 7 into address 44 Chapter 6 <27>

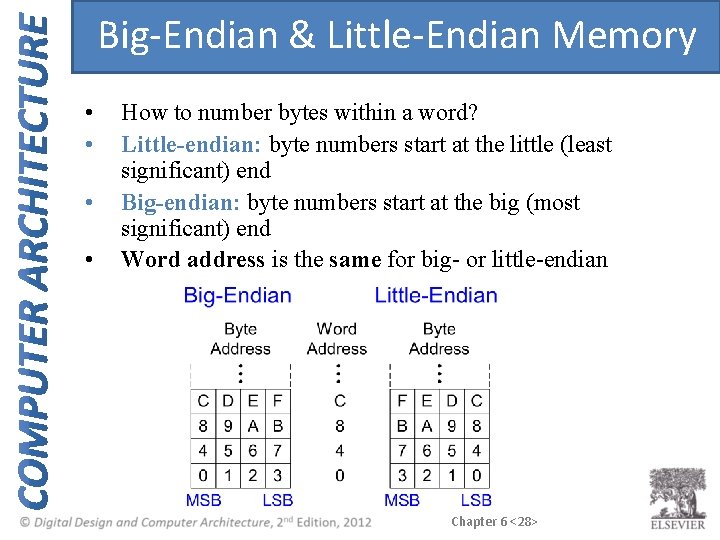

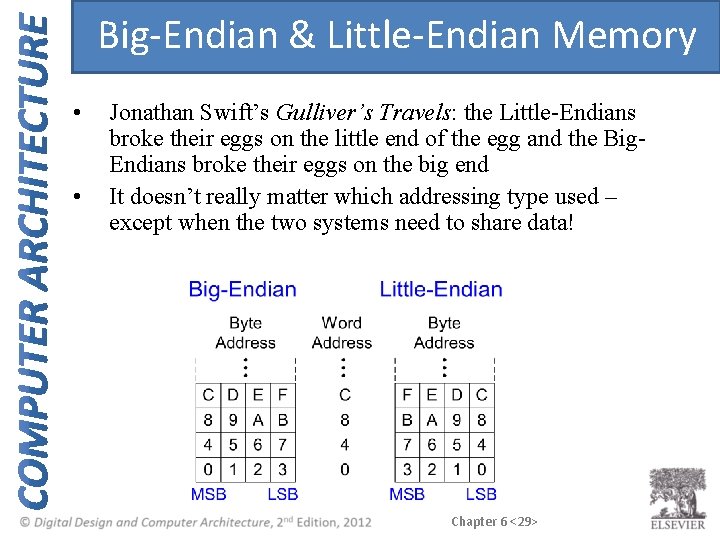

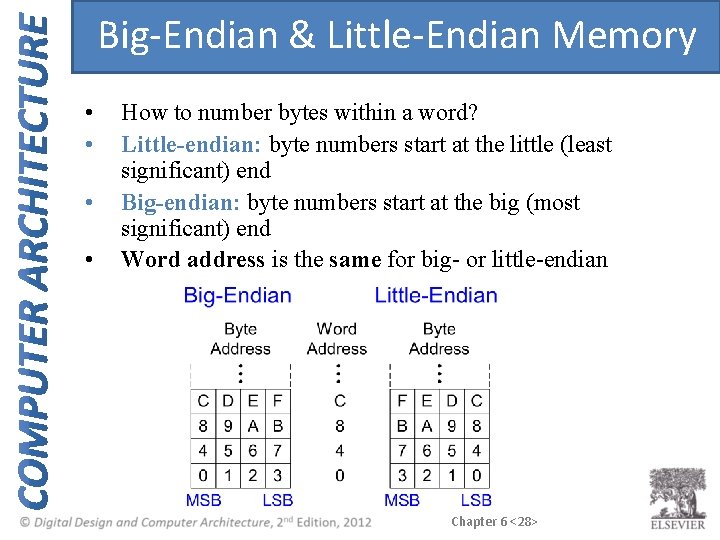

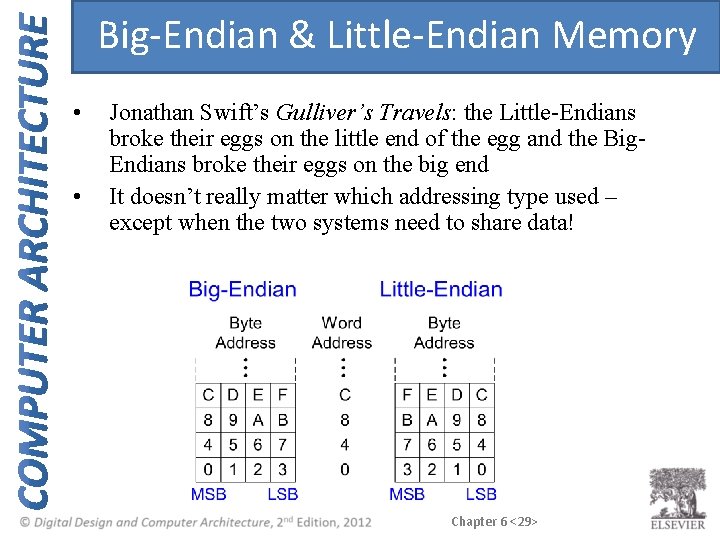

Big-Endian & Little-Endian Memory • • How to number bytes within a word? Little-endian: byte numbers start at the little (least significant) end Big-endian: byte numbers start at the big (most significant) end Word address is the same for big- or little-endian Chapter 6 <28>

Big-Endian & Little-Endian Memory • • Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels: the Little-Endians broke their eggs on the little end of the egg and the Big. Endians broke their eggs on the big end It doesn’t really matter which addressing type used – except when the two systems need to share data! Chapter 6 <29>

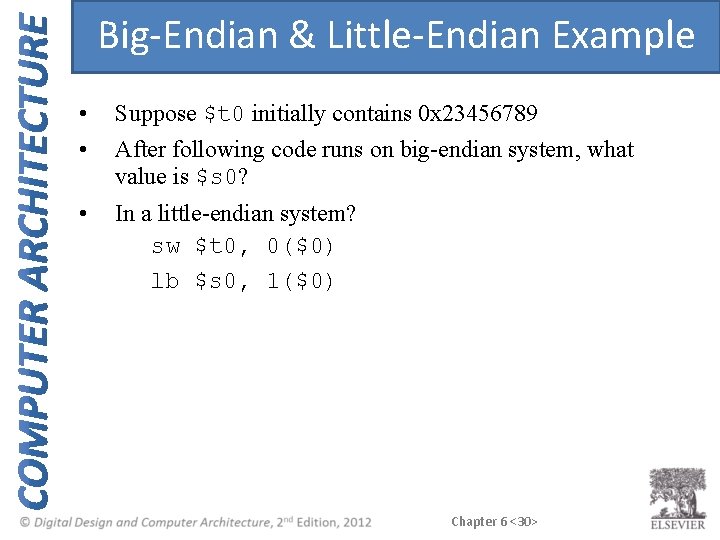

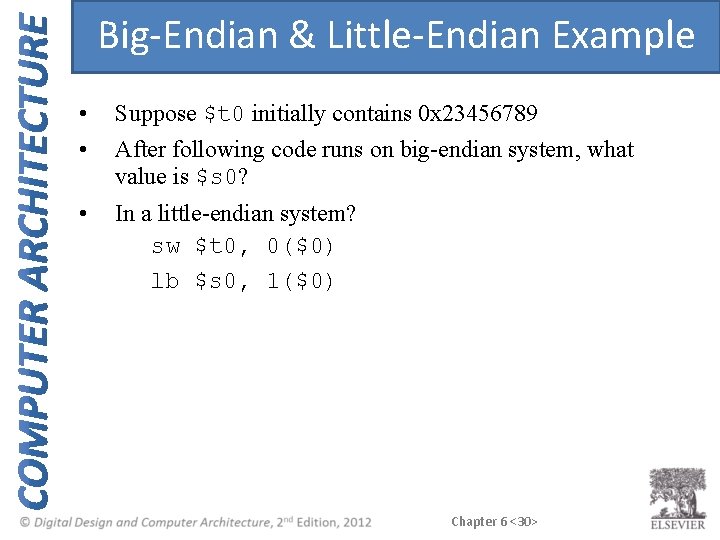

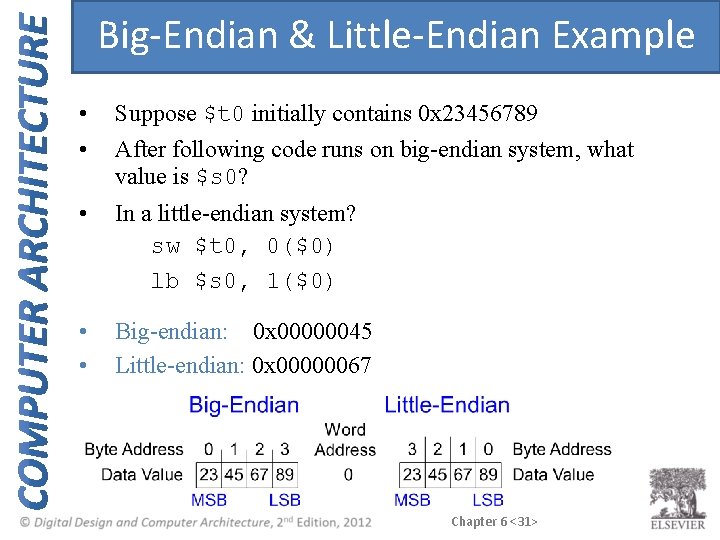

Big-Endian & Little-Endian Example • • Suppose $t 0 initially contains 0 x 23456789 • In a little-endian system? sw $t 0, 0($0) lb $s 0, 1($0) After following code runs on big-endian system, what value is $s 0? Chapter 6 <30>

Big-Endian & Little-Endian Example • • Suppose $t 0 initially contains 0 x 23456789 • In a little-endian system? sw $t 0, 0($0) lb $s 0, 1($0) • • Big-endian: 0 x 00000045 Little-endian: 0 x 00000067 After following code runs on big-endian system, what value is $s 0? Chapter 6 <31>

Design Principle 4 Good design demands good compromises • Multiple instruction formats allow flexibility - add, sub: use 3 register operands - lw, sw: use 2 register operands and a constant • Number of instruction formats kept small - to adhere to design principles 1 and 3 (simplicity favors regularity and smaller is faster). Chapter 6 <32>

Operands: Constants/Immediates • • • lw and sw use constants or immediates immediately available from instruction 16 -bit two’s complement number addi: add immediate Subtract immediate (subi) necessary? C Code MIPS assembly code a = a + 4; b = a – 12; # $s 0 = a, $s 1 = b addi $s 0, 4 addi $s 1, $s 0, -12 Chapter 6 <33>

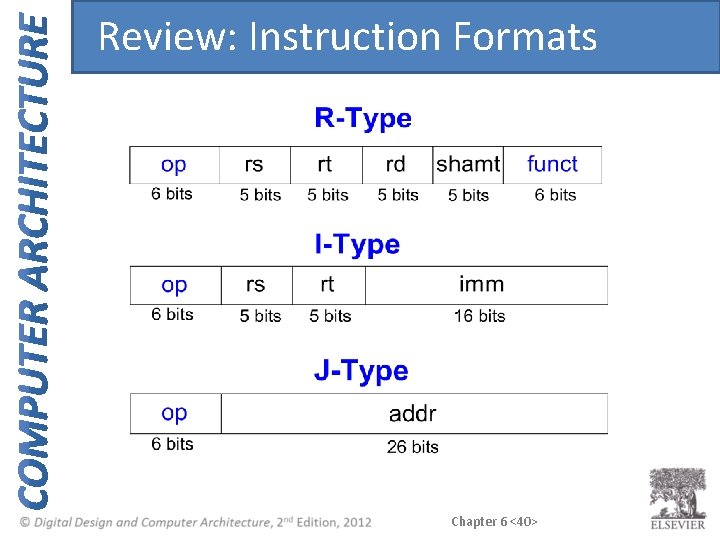

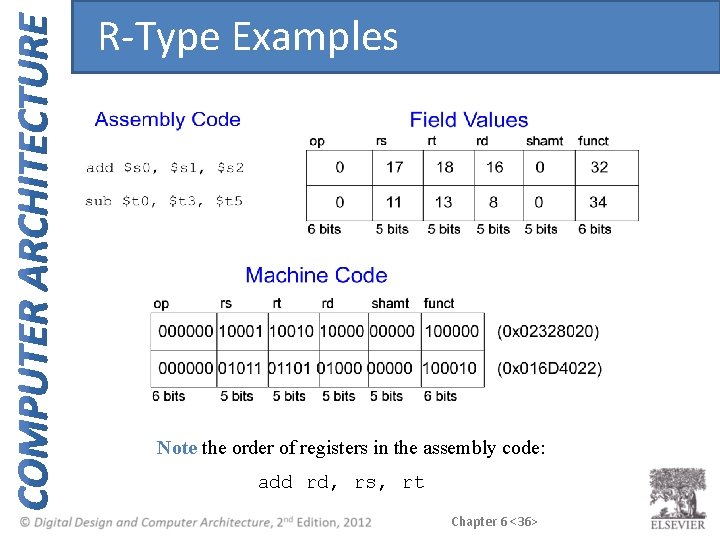

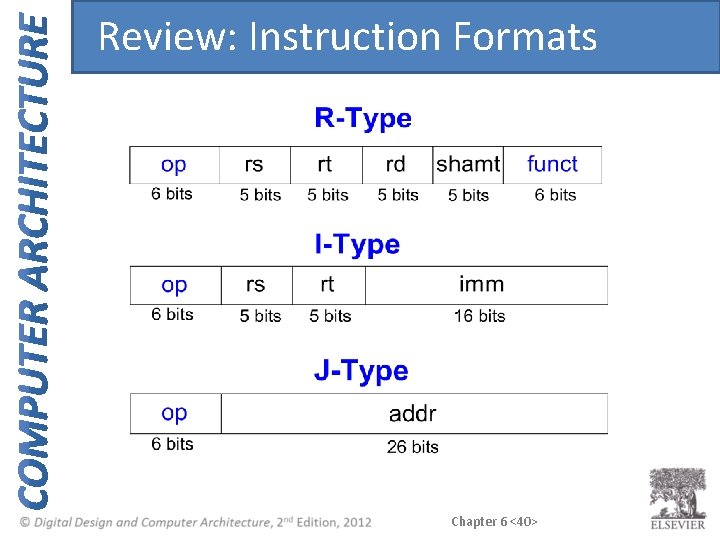

Machine Language • Binary representation of instructions • Computers only understand 1’s and 0’s • 32 -bit instructions – Simplicity favors regularity: 32 -bit data & instructions • 3 instruction formats: – R-Type: register operands – I-Type: immediate operand – J-Type: for jumping (discuss later) Chapter 6 <34>

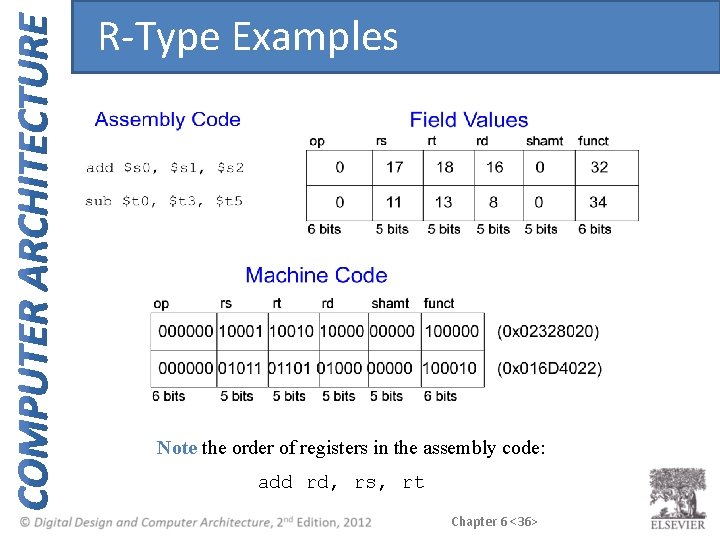

R-Type • • Register-type 3 register operands: – rs, rt: source registers – rd: destination register • Other fields: – op: the operation code or opcode (0 for R-type instructions) – funct: the function with opcode, tells computer what operation to perform – shamt: the shift amount for shift instructions, otherwise it’s 0 Chapter 6 <35>

R-Type Examples Note the order of registers in the assembly code: add rd, rs, rt Chapter 6 <36>

I-Type • • Immediate-type 3 operands: – rs, rt: register operands – imm: 16 -bit two’s complement immediate • Other fields: – op: the opcode – Simplicity favors regularity: all instructions have opcode – Operation is completely determined by opcode Chapter 6 <37>

I-Type Examples Note the differing order of registers in assembly and machine codes: addi rt, rs, imm lw rt, imm(rs) sw rt, imm(rs) Chapter 6 <38>

Machine Language: J-Type • Jump-type • 26 -bit address operand (addr) • Used for jump instructions (j) Chapter 6 <39>

Review: Instruction Formats Chapter 6 <40>

Power of the Stored Program • 32 -bit instructions & data stored in memory • Sequence of instructions: only difference between two applications • To run a new program: – No rewiring required – Simply store new program in memory • Program Execution: – Processor fetches (reads) instructions from memory in sequence – Processor performs the specified operation Chapter 6 <41>

The Stored Program Counter (PC): keeps track of current instruction Chapter 6 <42>

Interpreting Machine Code • Start with opcode: tells how to parse rest • If opcode all 0’s – R-type instruction – Function bits tell operation • Otherwise – opcode tells operation Chapter 6 <43>

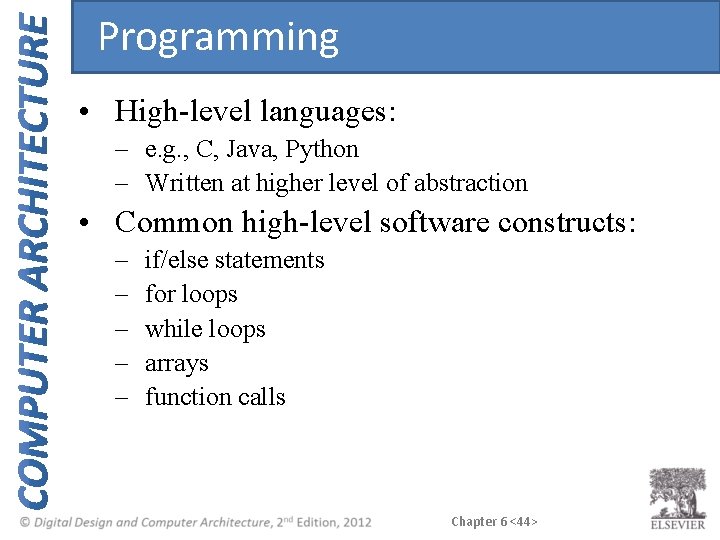

Programming • High-level languages: – e. g. , C, Java, Python – Written at higher level of abstraction • Common high-level software constructs: – – – if/else statements for loops while loops arrays function calls Chapter 6 <44>

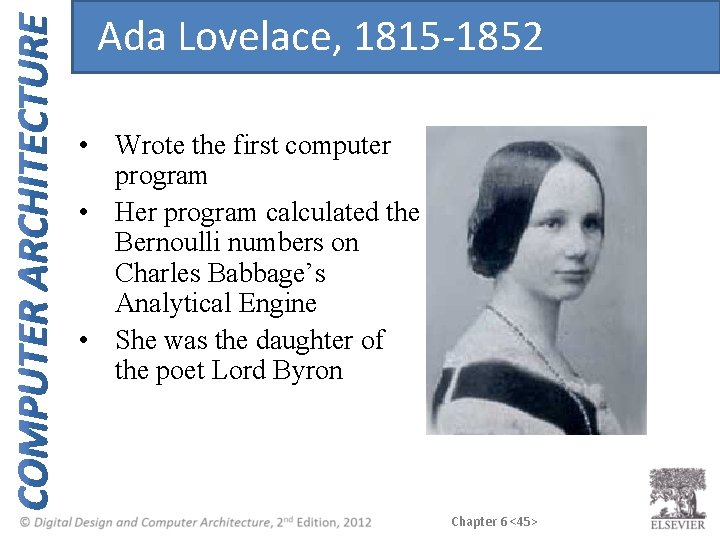

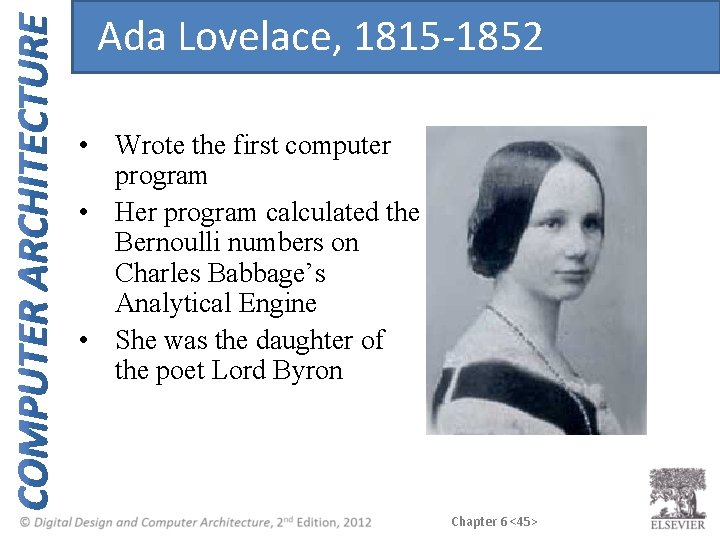

Ada Lovelace, 1815 -1852 • Wrote the first computer program • Her program calculated the Bernoulli numbers on Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine • She was the daughter of the poet Lord Byron Chapter 6 <45>

Logical Instructions • and, or, xor, nor – and: useful for masking bits • Masking all but the least significant byte of a value: 0 x. F 234012 F AND 0 x 000000 FF = 0 x 0000002 F – or: useful for combining bit fields • Combine 0 x. F 2340000 with 0 x 000012 BC: 0 x. F 2340000 OR 0 x 000012 BC = 0 x. F 23412 BC – nor: useful for inverting bits: • A NOR $0 = NOT A • andi, ori, xori – 16 -bit immediate is zero-extended (not sign-extended) – nori not needed Chapter 6 <46>

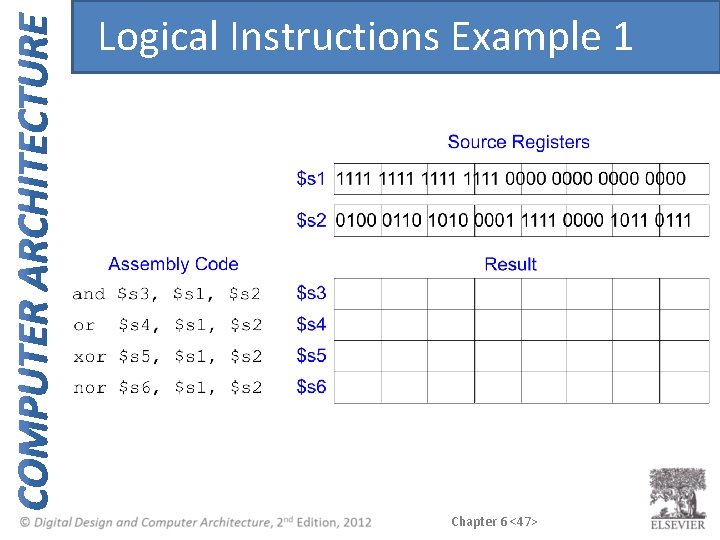

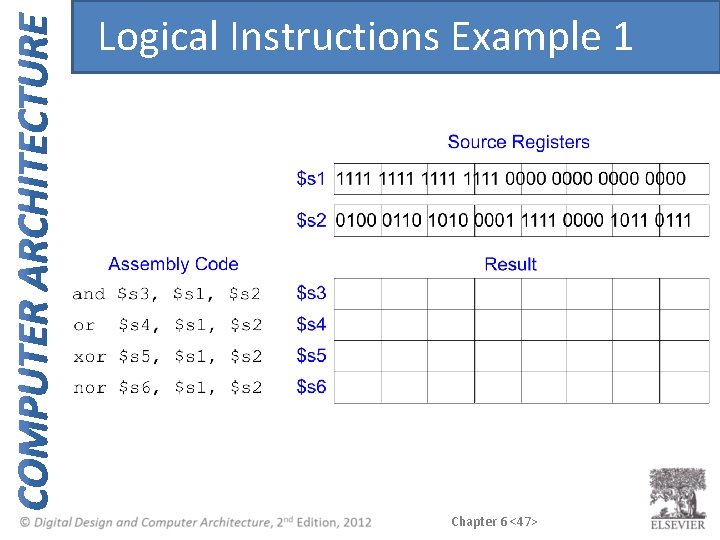

Logical Instructions Example 1 Chapter 6 <47>

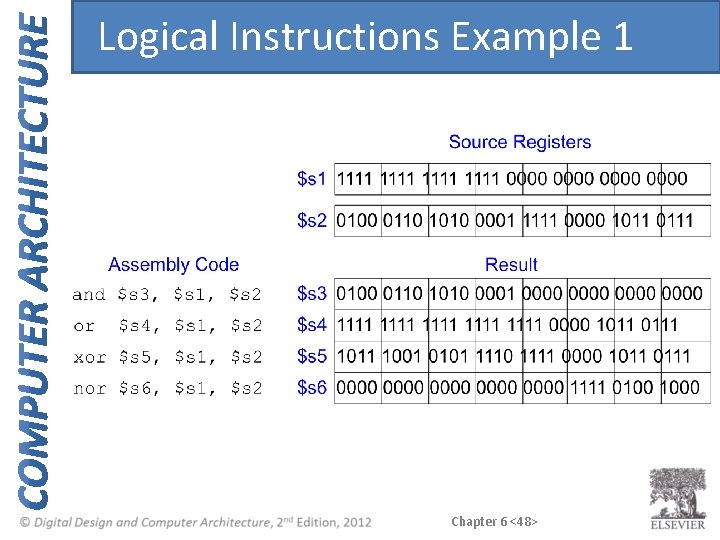

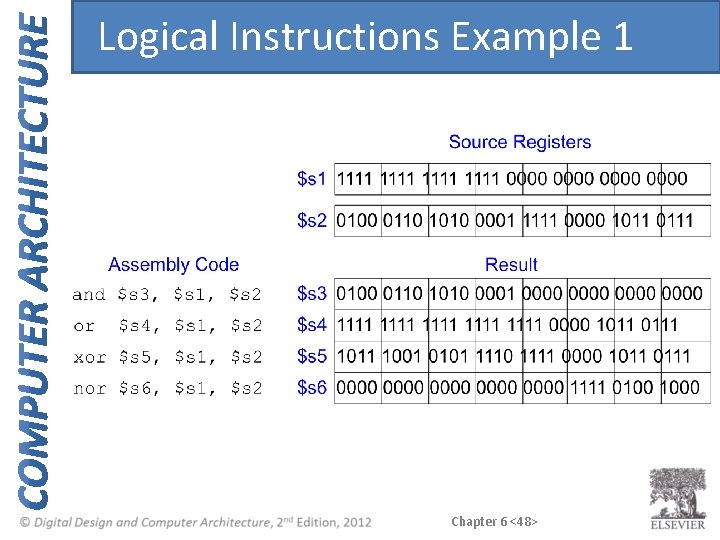

Logical Instructions Example 1 Chapter 6 <48>

Logical Instructions Example 2 Chapter 6 <49>

Logical Instructions Example 2 Chapter 6 <50>

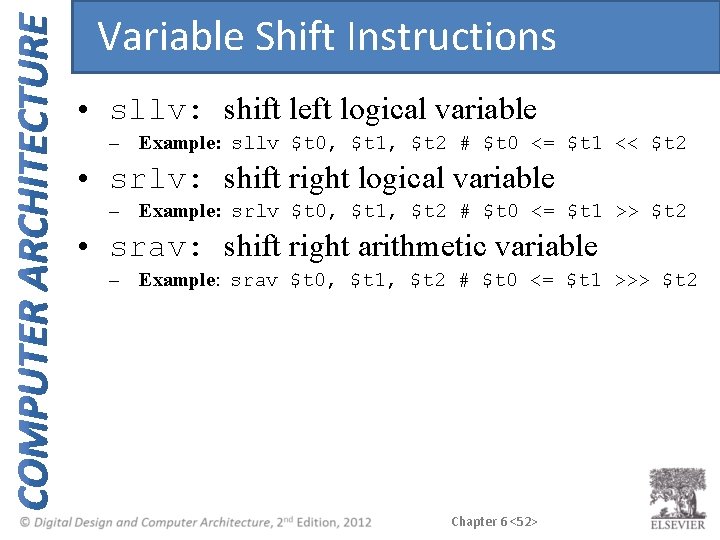

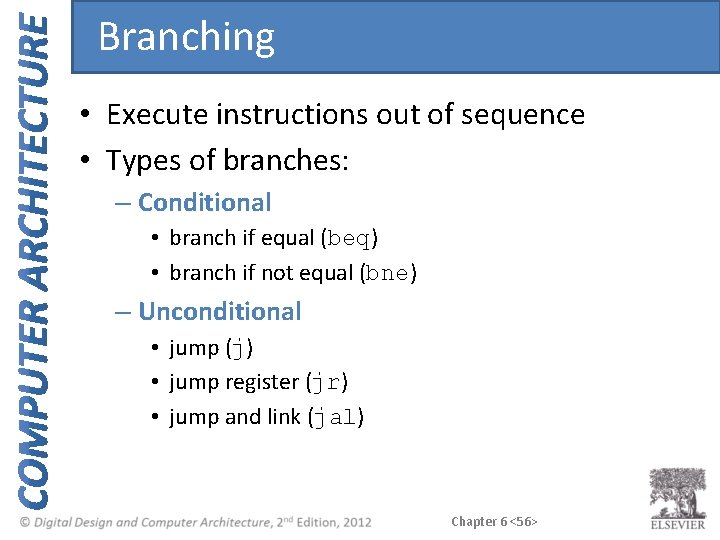

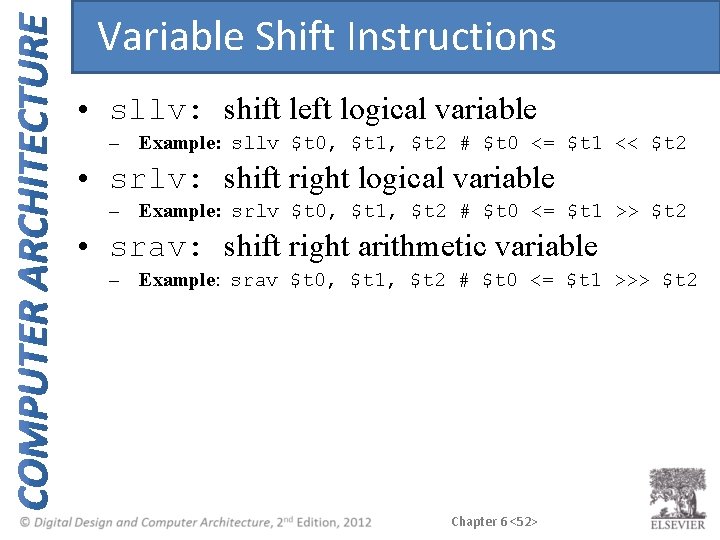

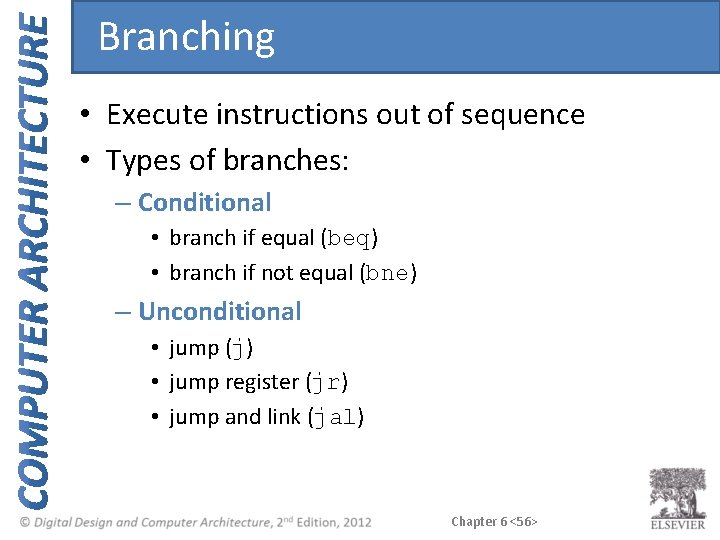

Shift Instructions • sll: shift left logical – Example: sll $t 0, $t 1, 5 # $t 0 <= $t 1 << 5 • srl: shift right logical – Example: srl $t 0, $t 1, 5 # $t 0 <= $t 1 >> 5 • sra: shift right arithmetic – Example: sra $t 0, $t 1, 5 # $t 0 <= $t 1 >>> 5 Chapter 6 <51>

Variable Shift Instructions • sllv: shift left logical variable – Example: sllv $t 0, $t 1, $t 2 # $t 0 <= $t 1 << $t 2 • srlv: shift right logical variable – Example: srlv $t 0, $t 1, $t 2 # $t 0 <= $t 1 >> $t 2 • srav: shift right arithmetic variable – Example: srav $t 0, $t 1, $t 2 # $t 0 <= $t 1 >>> $t 2 Chapter 6 <52>

Shift Instructions Chapter 6 <53>

Generating Constants • 16 -bit constants using addi: C Code MIPS assembly code // int is a 32 -bit signed word int a = 0 x 4 f 3 c; # $s 0 = a addi $s 0, $0, 0 x 4 f 3 c • 32 -bit constants using load upper immediate (lui) and ori: C Code MIPS assembly code int a = 0 x. FEDC 8765; # $s 0 = a lui $s 0, 0 x. FEDC ori $s 0, 0 x 8765 Chapter 6 <54>

Multiplication, Division • Special registers: lo, hi • 32 × 32 multiplication, 64 bit result – mult $s 0, $s 1 – Result in {hi, lo} • 32 -bit division, 32 -bit quotient, remainder – div $s 0, $s 1 – Quotient in lo – Remainder in hi • Moves from lo/hi special registers – mflo $s 2 – mfhi $s 3 Chapter 6 <55>

Branching • Execute instructions out of sequence • Types of branches: – Conditional • branch if equal (beq) • branch if not equal (bne) – Unconditional • jump (j) • jump register (jr) • jump and link (jal) Chapter 6 <56>

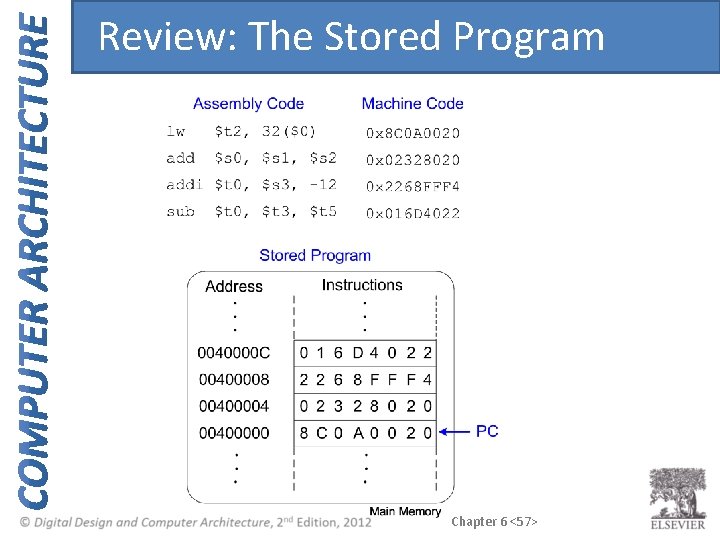

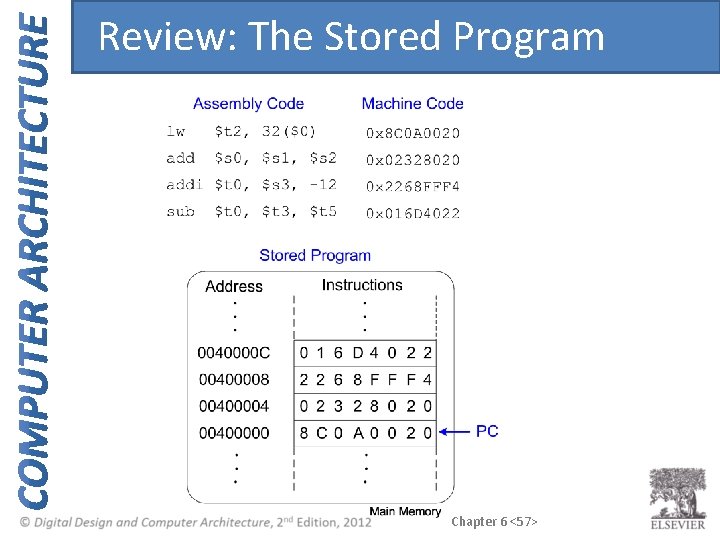

Review: The Stored Program Chapter 6 <57>

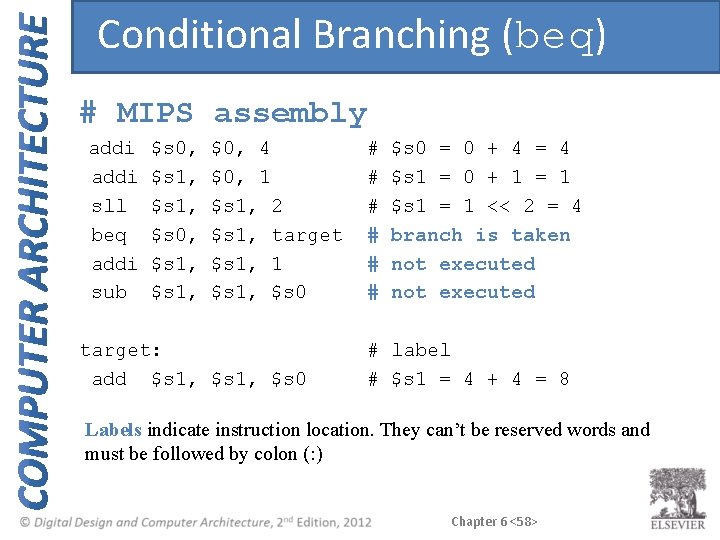

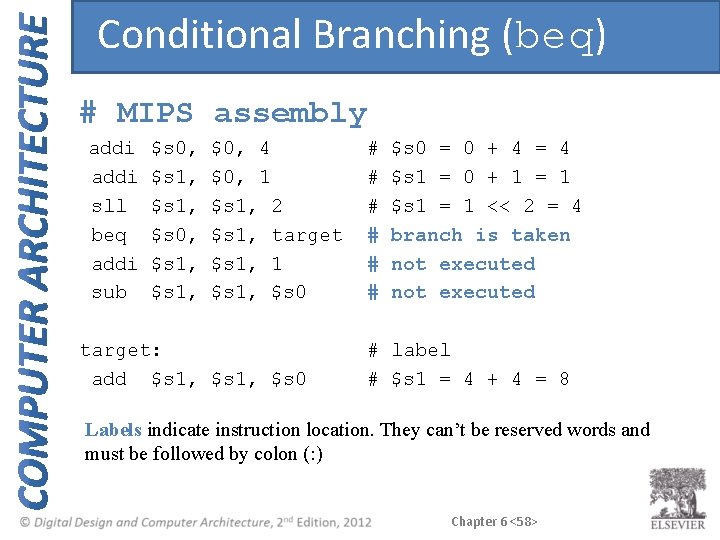

Conditional Branching (beq) # MIPS assembly addi sll beq addi sub $s 0, $s 1, $0, 4 $0, 1 $s 1, 2 $s 1, target $s 1, 1 $s 1, $s 0 target: add $s 1, $s 0 # # # $s 0 = 0 + 4 = 4 $s 1 = 0 + 1 = 1 $s 1 = 1 << 2 = 4 branch is taken not executed # label # $s 1 = 4 + 4 = 8 Labels indicate instruction location. They can’t be reserved words and must be followed by colon (: ) Chapter 6 <58>

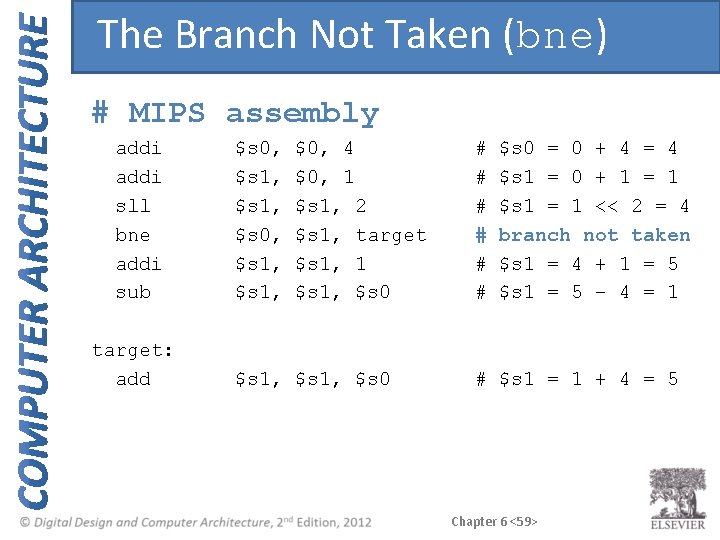

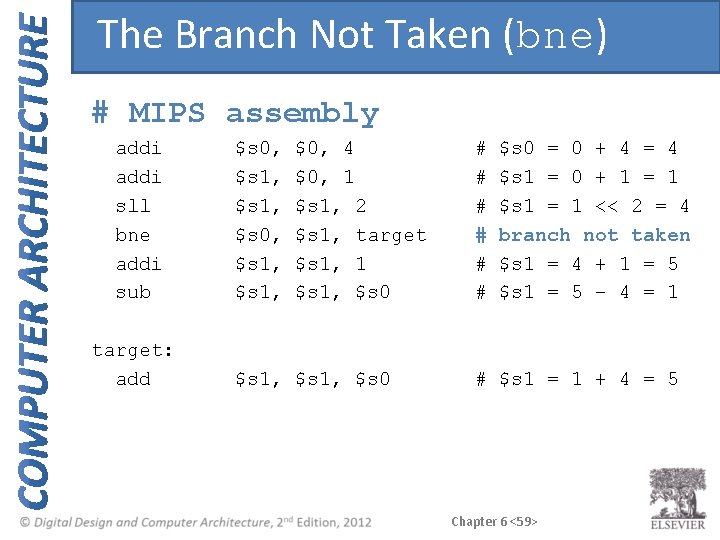

The Branch Not Taken (bne) # MIPS assembly addi sll bne addi sub target: add $s 0, $s 1, $0, 4 $0, 1 $s 1, 2 $s 1, target $s 1, 1 $s 1, $s 0 # # # $s 0 = 0 + 4 = 4 $s 1 = 0 + 1 = 1 $s 1 = 1 << 2 = 4 branch not taken $s 1 = 4 + 1 = 5 $s 1 = 5 – 4 = 1 # $s 1 = 1 + 4 = 5 Chapter 6 <59>

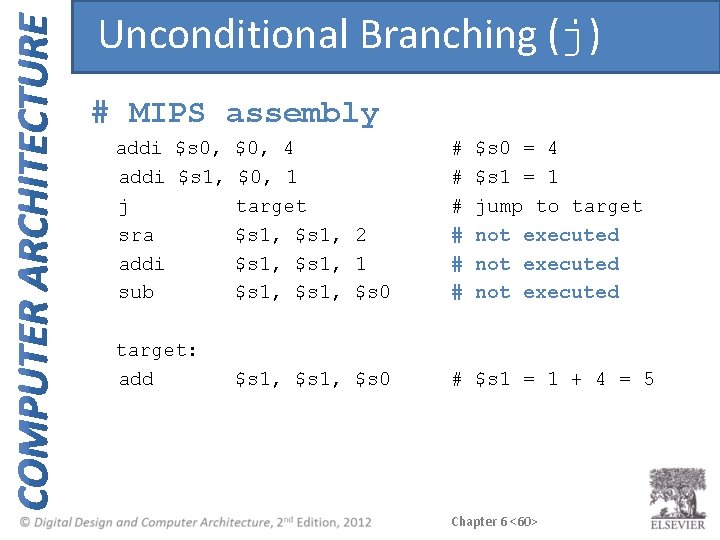

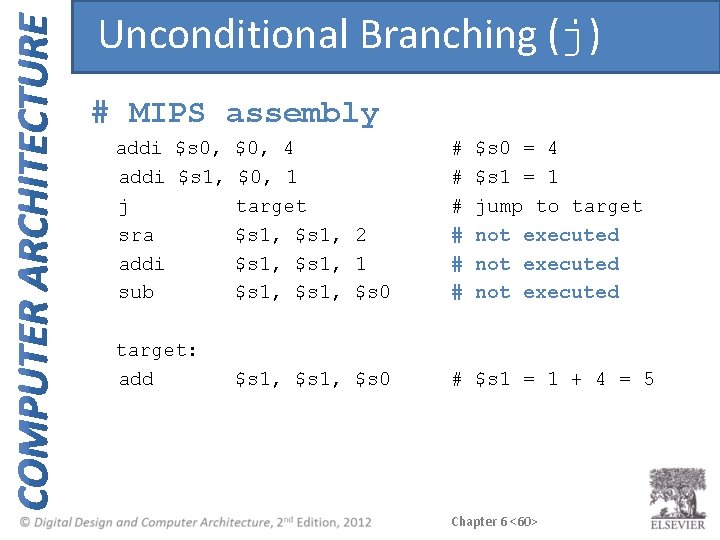

Unconditional Branching (j) # MIPS assembly addi $s 0, $0, 4 addi $s 1, $0, 1 j target sra $s 1, 2 addi $s 1, 1 sub $s 1, $s 0 # # # target: add # $s 1 = 1 + 4 = 5 $s 1, $s 0 = 4 $s 1 = 1 jump to target not executed Chapter 6 <60>

Unconditional Branching (jr) # MIPS assembly 0 x 00002000 0 x 00002004 0 x 00002008 0 x 0000200 C 0 x 00002010 addi jr addi sra lw $s 0, $s 0 $s 1, $s 3, $0, 0 x 2010 $0, 1 $s 1, 2 44($s 1) jr is an R-type instruction. Chapter 6 <61>

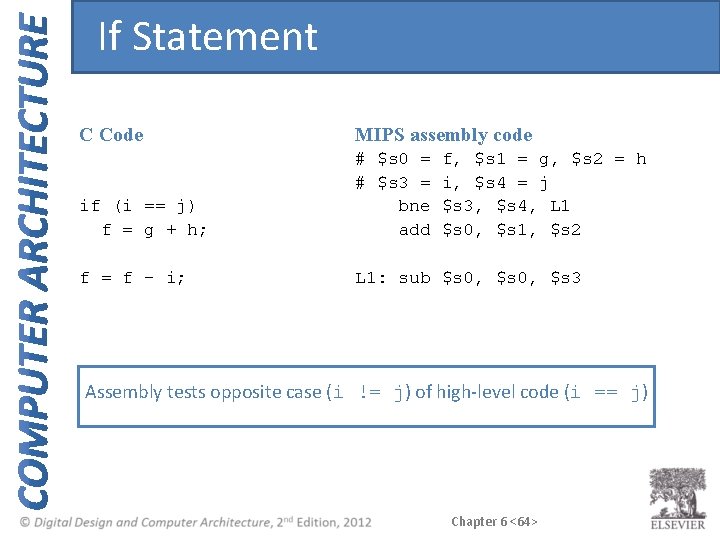

High-Level Code Constructs • • if statements if/else statements while loops for loops Chapter 6 <62>

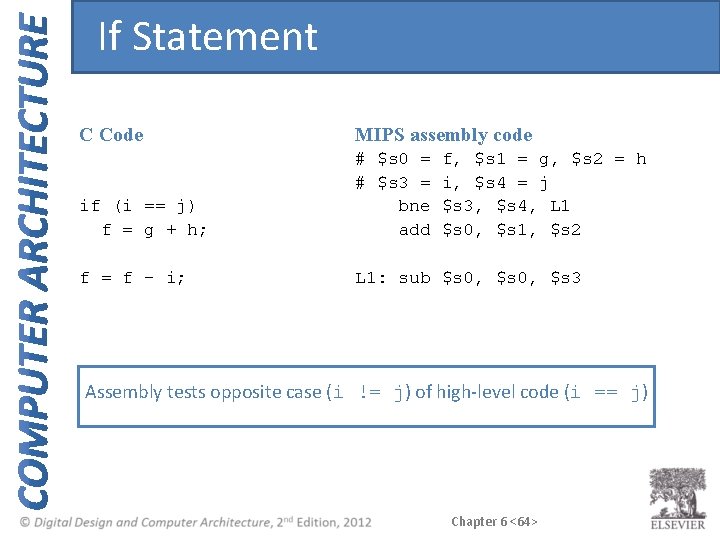

If Statement C Code MIPS assembly code # $s 0 = f, $s 1 = g, $s 2 = h # $s 3 = i, $s 4 = j if (i == j) f = g + h; f = f – i; Chapter 6 <63>

If Statement C Code MIPS assembly code if (i == j) f = g + h; # $s 0 = # $s 3 = bne add f = f – i; L 1: sub $s 0, $s 3 f, $s 1 = g, $s 2 = h i, $s 4 = j $s 3, $s 4, L 1 $s 0, $s 1, $s 2 Assembly tests opposite case (i != j) of high-level code (i == j) Chapter 6 <64>

If/Else Statement C Code MIPS assembly code if (i == j) f = g + h; else f = f – i; Chapter 6 <65>

If/Else Statement C Code if (i == j) f = g + h; else f = f – i; MIPS assembly code # $s 0 = f, $s 1 # $s 3 = i, $s 4 bne $s 3, add $s 0, j done L 1: sub $s 0, done: = g, $s 2 = h = j $s 4, L 1 $s 1, $s 2 $s 0, $s 3 Chapter 6 <66>

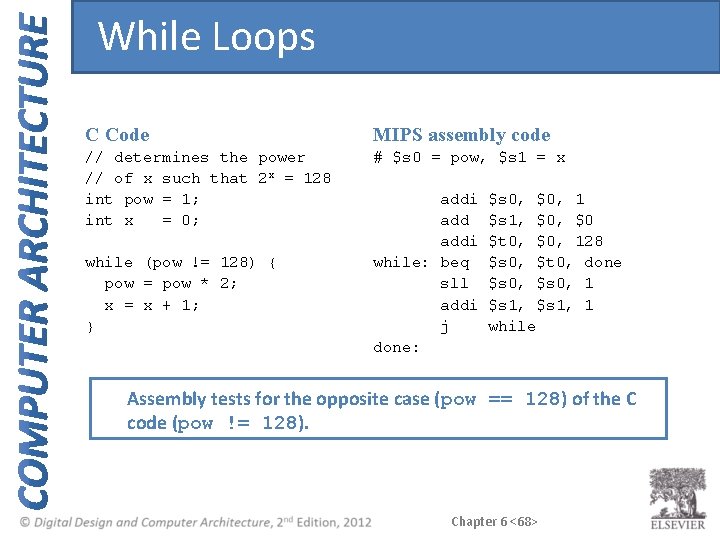

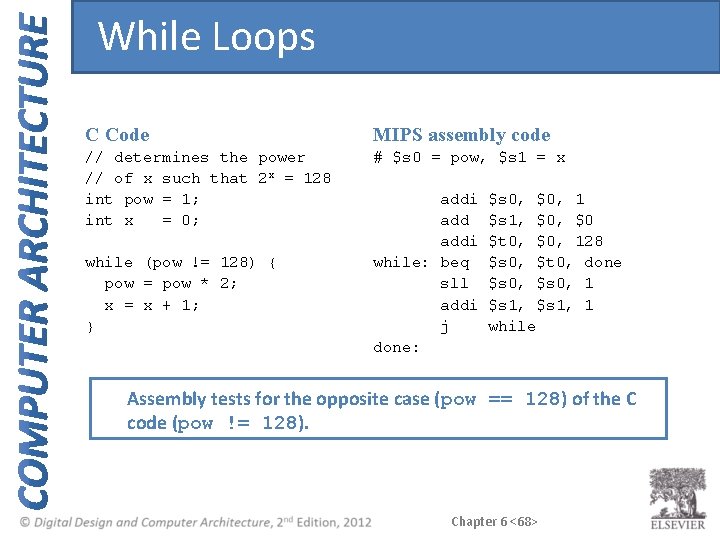

While Loops C Code MIPS assembly code // determines the power // of x such that 2 x = 128 int pow = 1; int x = 0; while (pow != 128) { pow = pow * 2; x = x + 1; } Assembly tests for the opposite case (pow == 128) of the C code (pow != 128). Chapter 6 <67>

While Loops C Code MIPS assembly code // determines the power // of x such that 2 x = 128 int pow = 1; int x = 0; # $s 0 = pow, $s 1 = x while (pow != 128) { pow = pow * 2; x = x + 1; } addi while: beq sll addi j done: $s 0, $0, 1 $s 1, $0 $t 0, $0, 128 $s 0, $t 0, done $s 0, 1 $s 1, 1 while Assembly tests for the opposite case (pow == 128) of the C code (pow != 128). Chapter 6 <68>

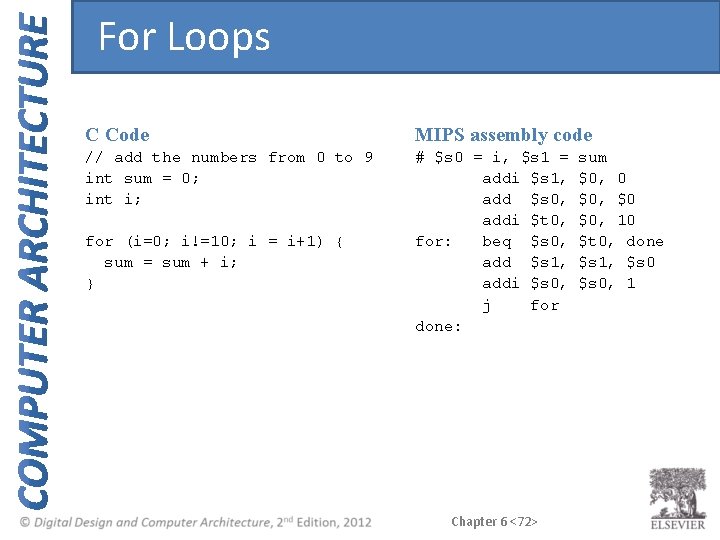

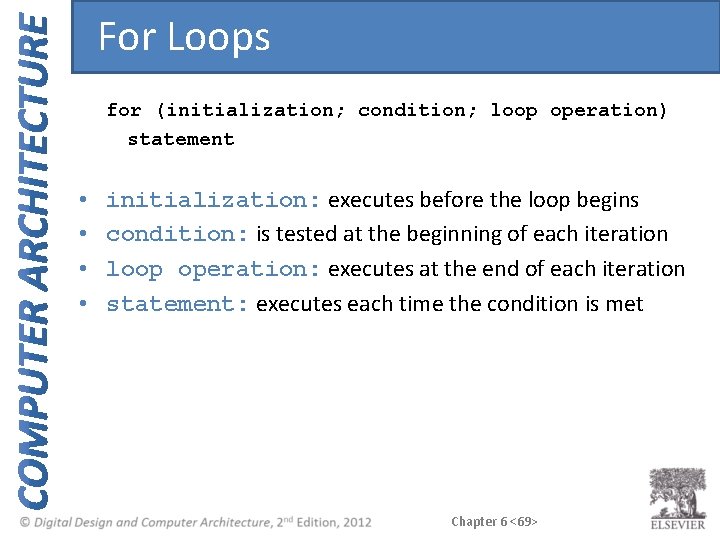

For Loops for (initialization; condition; loop operation) statement • • initialization: executes before the loop begins condition: is tested at the beginning of each iteration loop operation: executes at the end of each iteration statement: executes each time the condition is met Chapter 6 <69>

For Loops High-level code MIPS assembly code // add the numbers from 0 to 9 int sum = 0; int i; # $s 0 = i, $s 1 = sum for (i=0; i!=10; i = i+1) { sum = sum + i; } Chapter 6 <70>

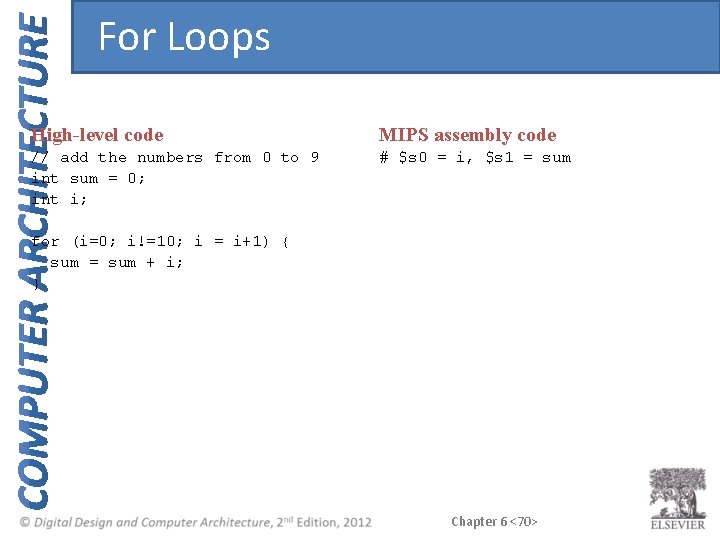

For Loops C Code MIPS assembly code // add the numbers from 0 to 9 int sum = 0; int i; for (i=0; i!=10; i = i+1) { sum = sum + i; } Chapter 6 <71>

For Loops C Code MIPS assembly code // add the numbers from 0 to 9 int sum = 0; int i; # $s 0 = i, $s 1 = addi $s 1, add $s 0, addi $t 0, for: beq $s 0, add $s 1, addi $s 0, j for done: for (i=0; i!=10; i = i+1) { sum = sum + i; } Chapter 6 <72> sum $0, 0 $0, $0 $0, 10 $t 0, done $s 1, $s 0, 1

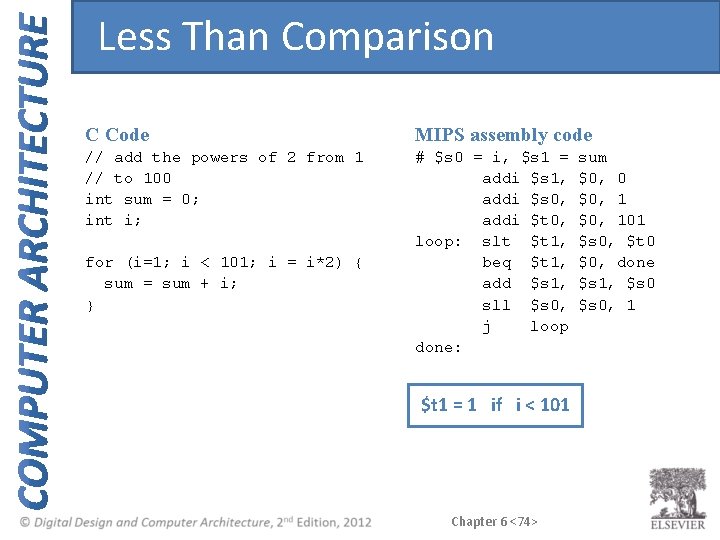

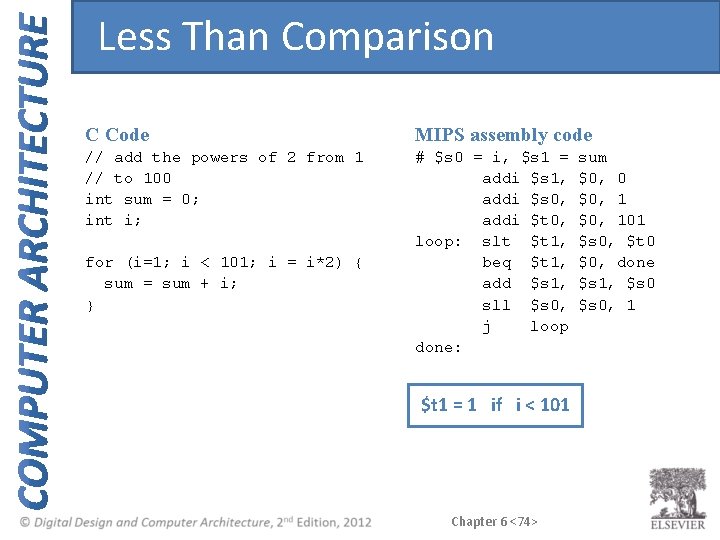

Less Than Comparison C Code MIPS assembly code // add the powers of 2 from 1 // to 100 int sum = 0; int i; for (i=1; i < 101; i = i*2) { sum = sum + i; } Chapter 6 <73>

Less Than Comparison C Code MIPS assembly code // add the powers of 2 from 1 // to 100 int sum = 0; int i; # $s 0 = i, $s 1 = addi $s 1, addi $s 0, addi $t 0, loop: slt $t 1, beq $t 1, add $s 1, sll $s 0, j loop done: for (i=1; i < 101; i = i*2) { sum = sum + i; } $t 1 = 1 if i < 101 Chapter 6 <74> sum $0, 0 $0, 101 $s 0, $t 0 $0, done $s 1, $s 0, 1

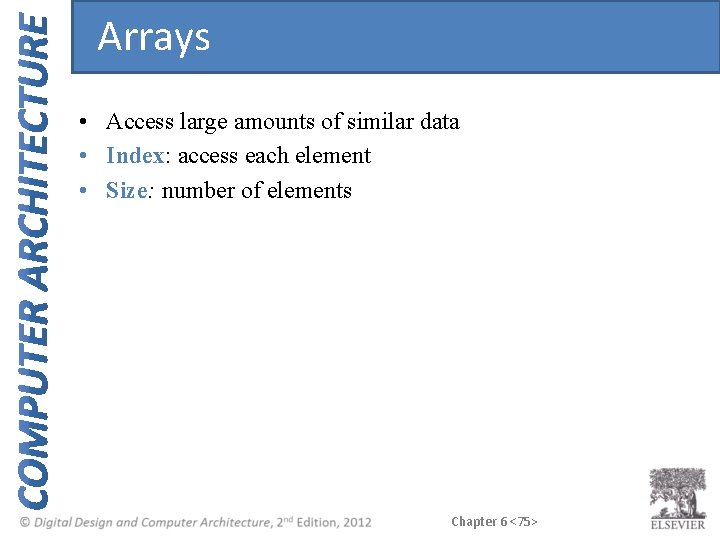

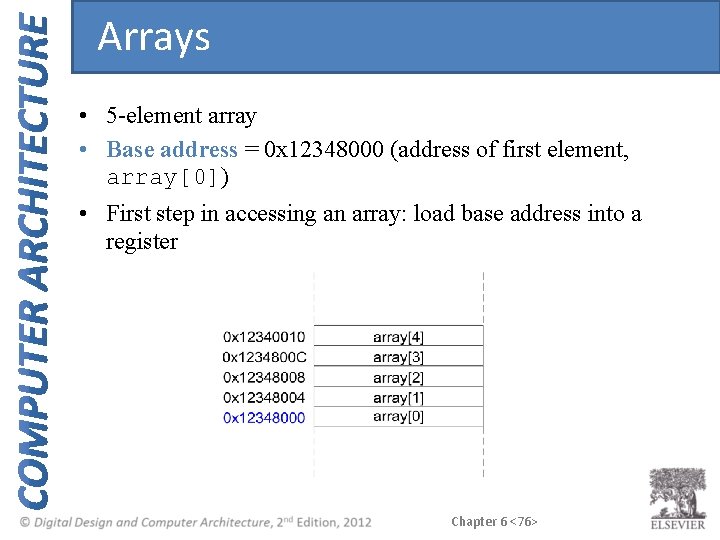

Arrays • Access large amounts of similar data • Index: access each element • Size: number of elements Chapter 6 <75>

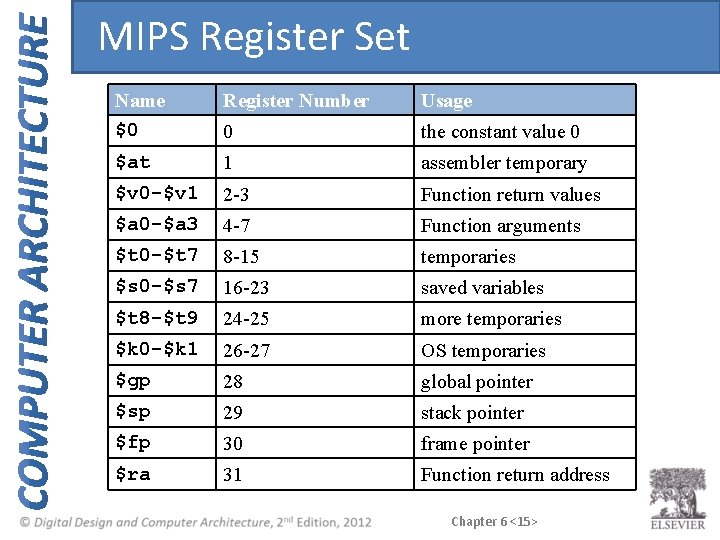

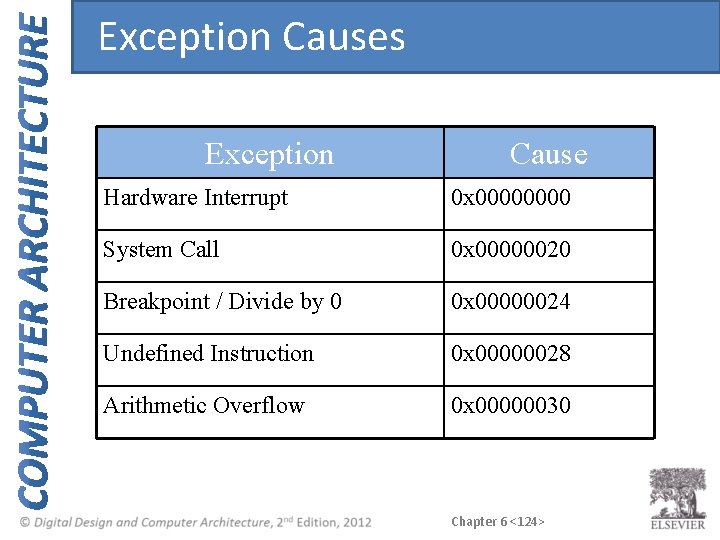

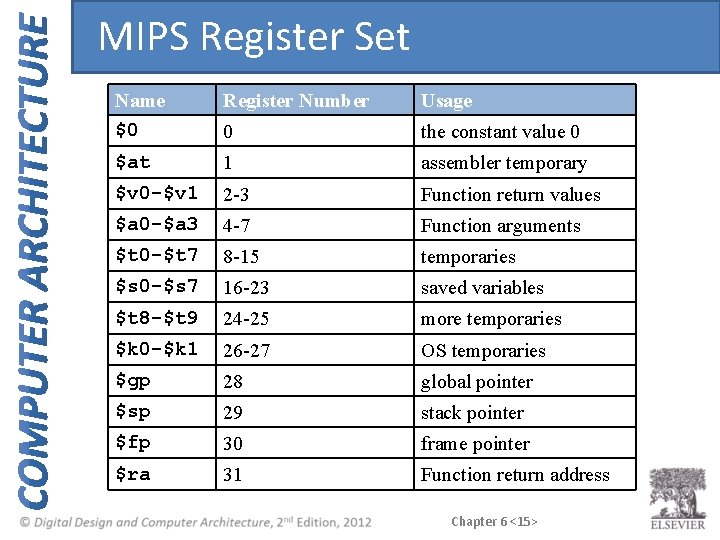

Arrays • 5 -element array • Base address = 0 x 12348000 (address of first element, array[0]) • First step in accessing an array: load base address into a register Chapter 6 <76>

![Accessing Arrays C Code int array5 array0 array0 2 array1 Accessing Arrays // C Code int array[5]; array[0] = array[0] * 2; array[1] =](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/91b4629b1b7b3ed4fff3b8edaf659558/image-77.jpg)

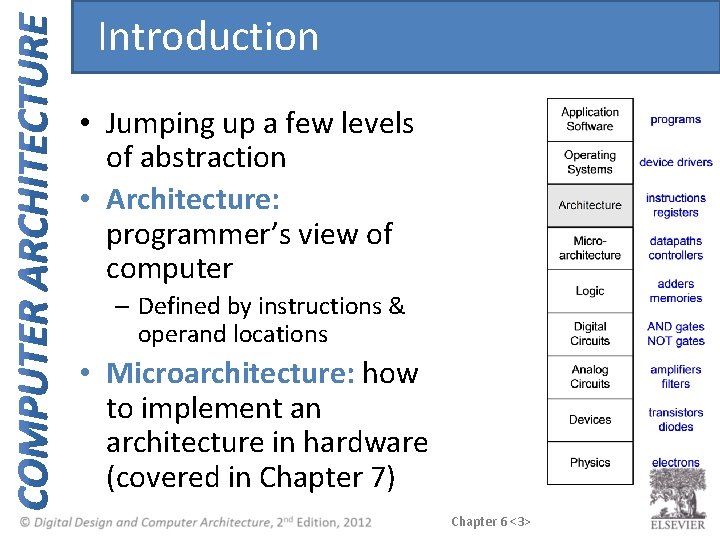

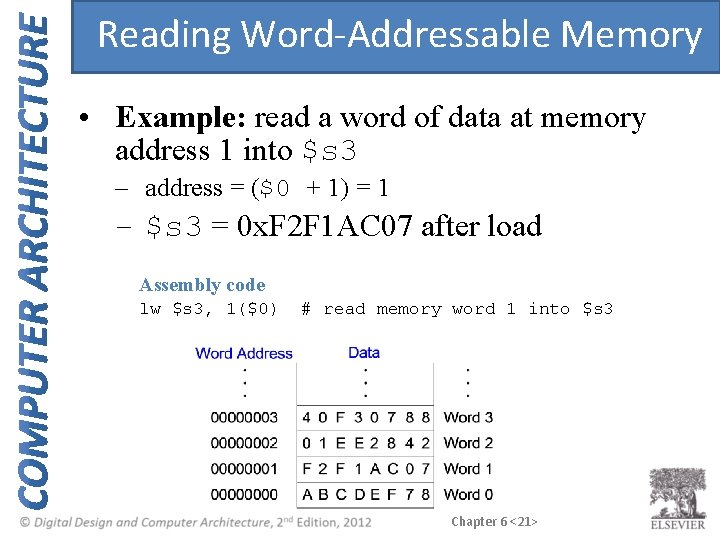

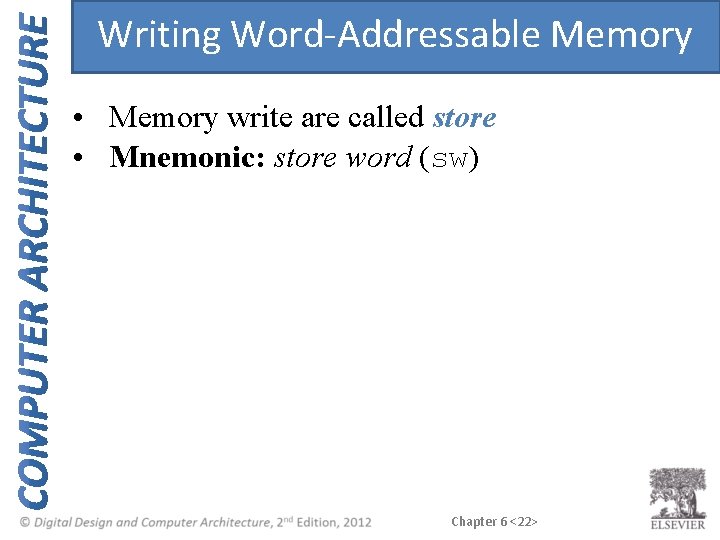

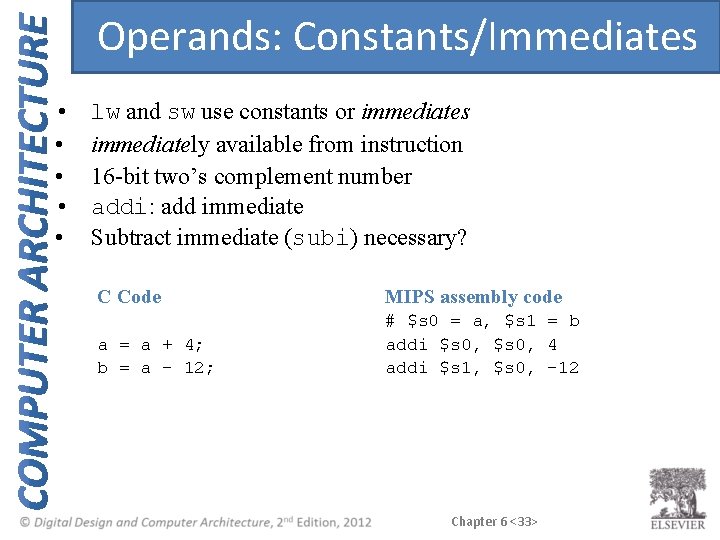

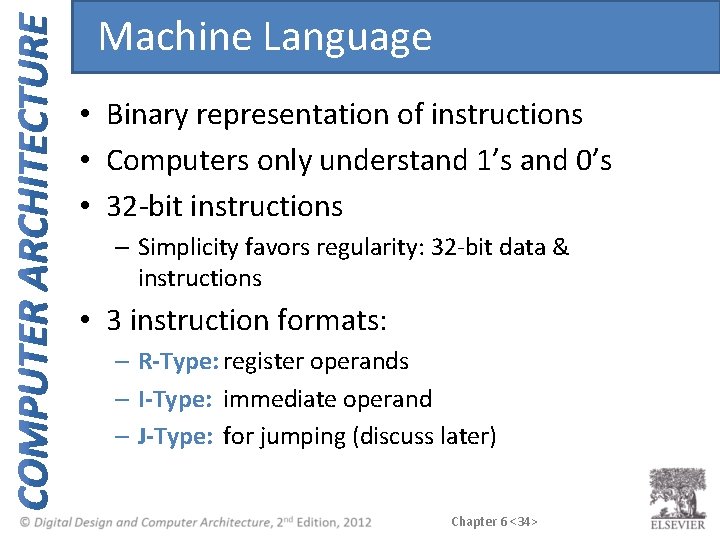

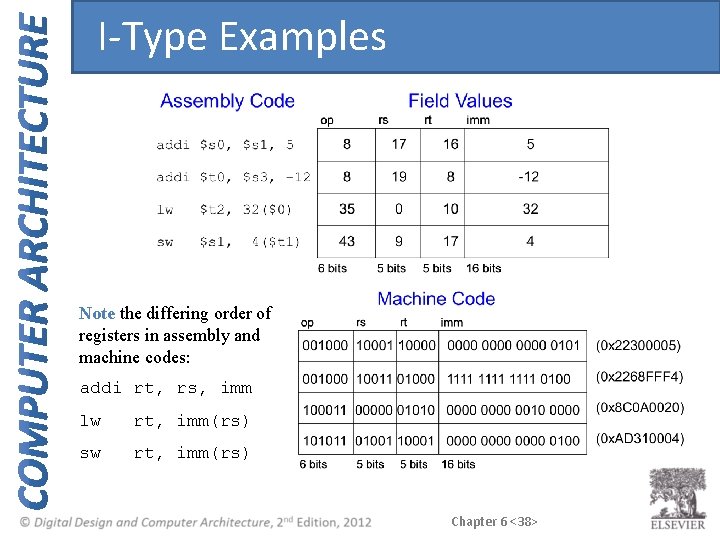

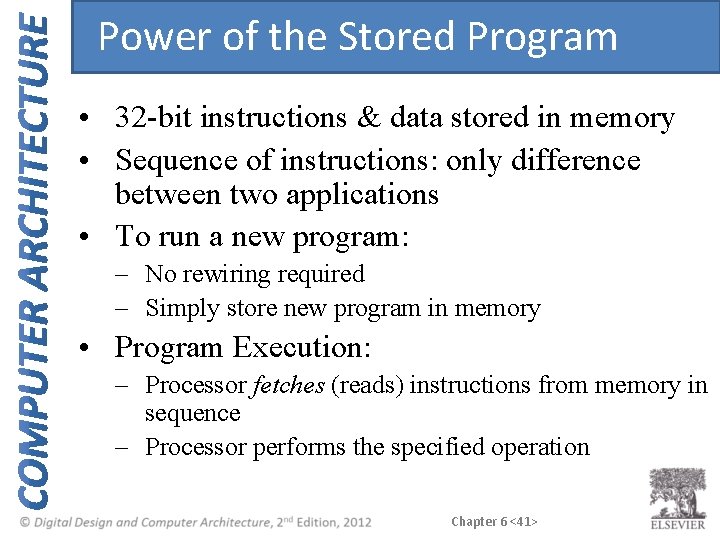

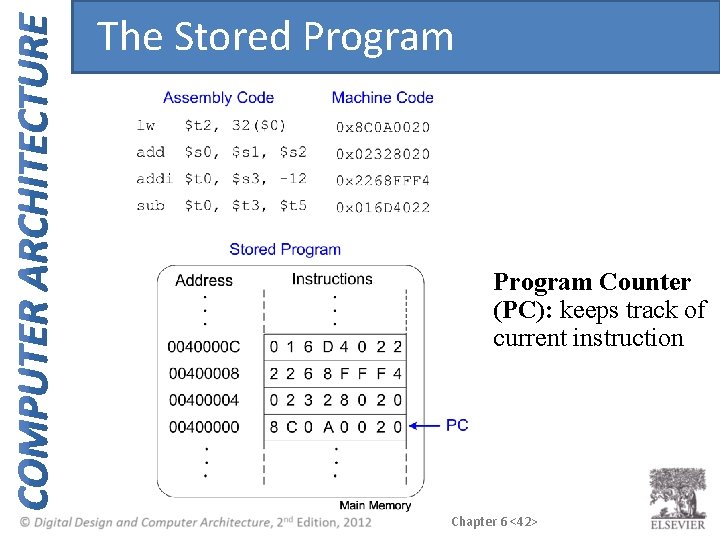

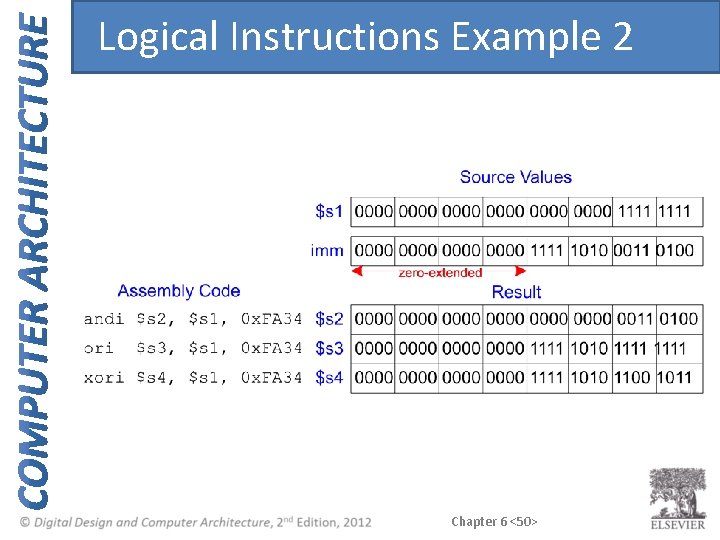

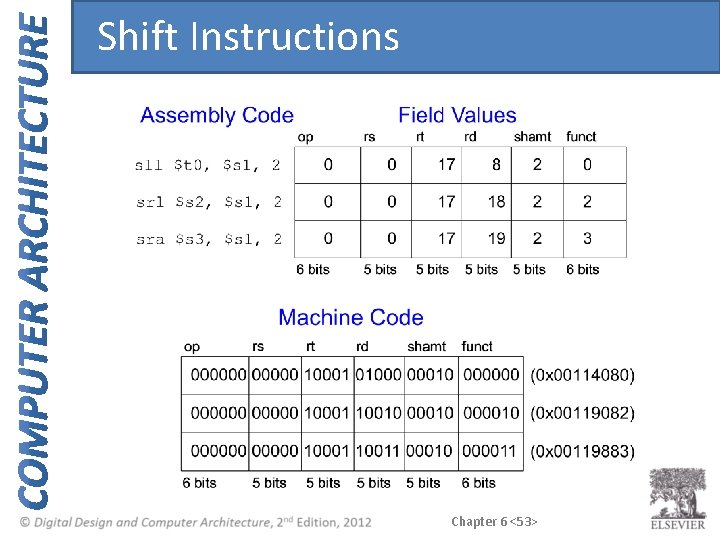

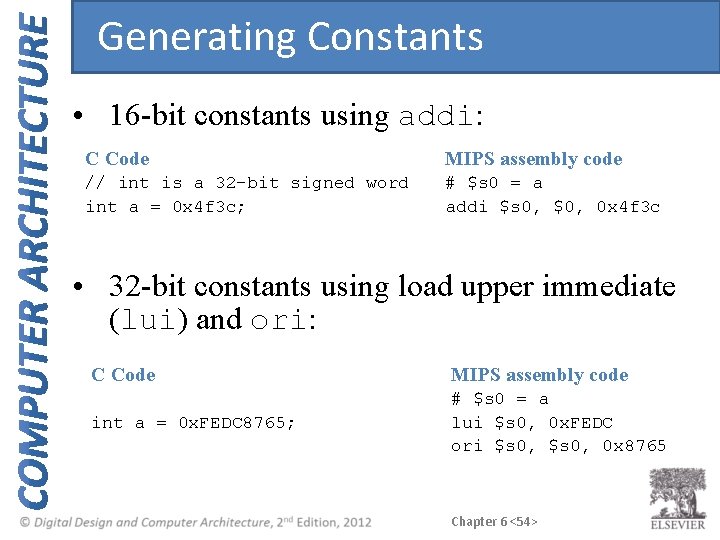

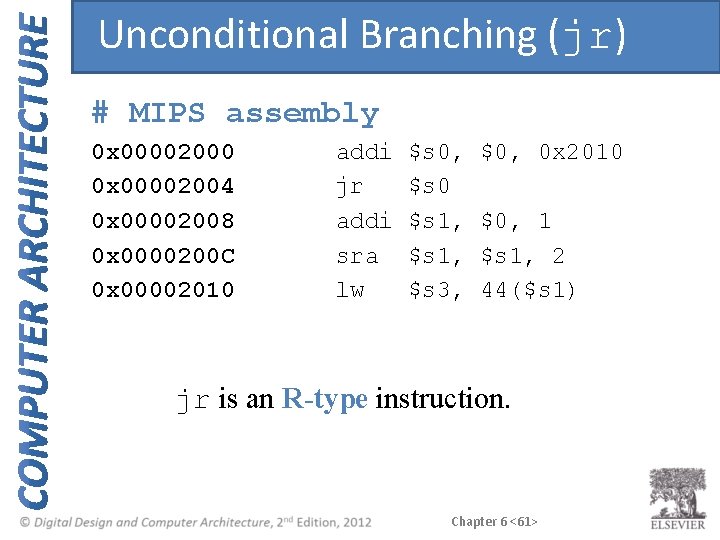

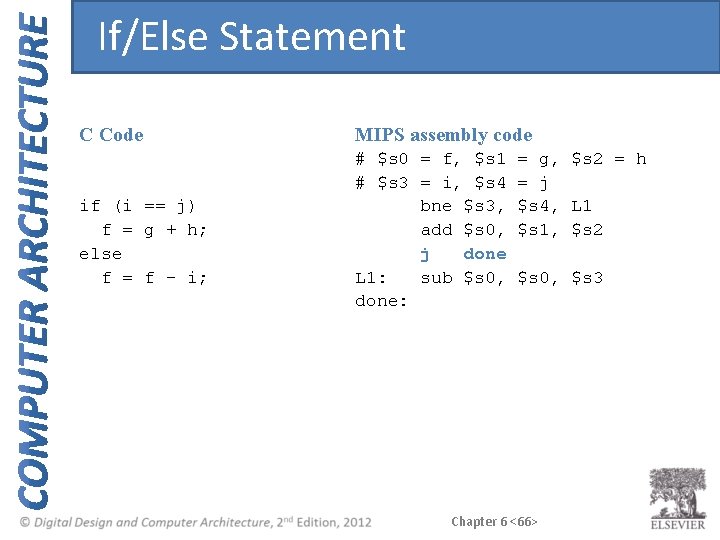

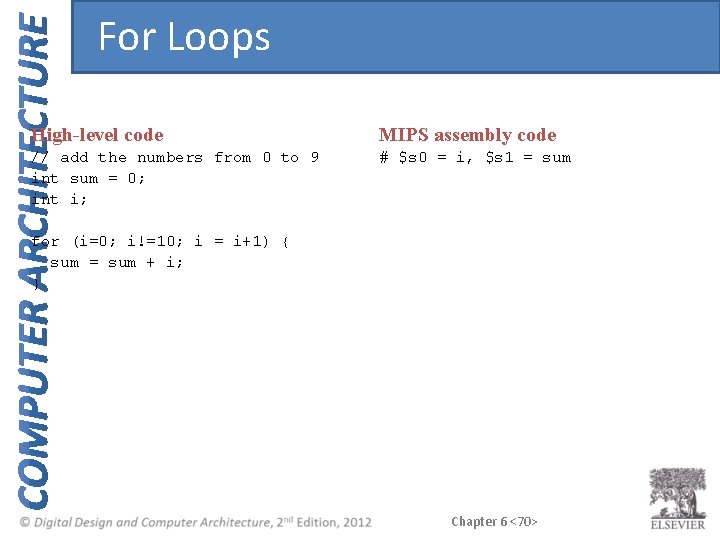

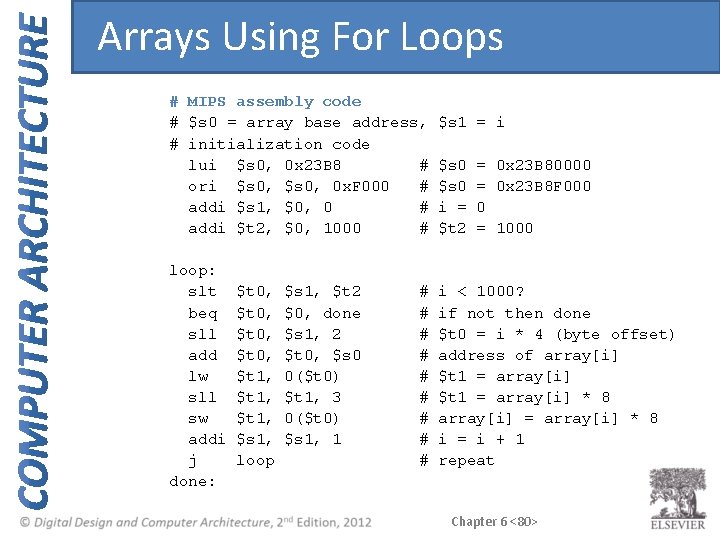

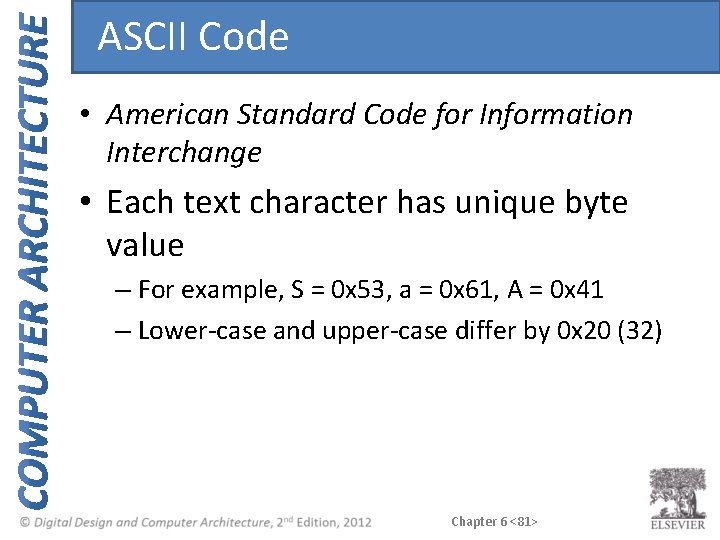

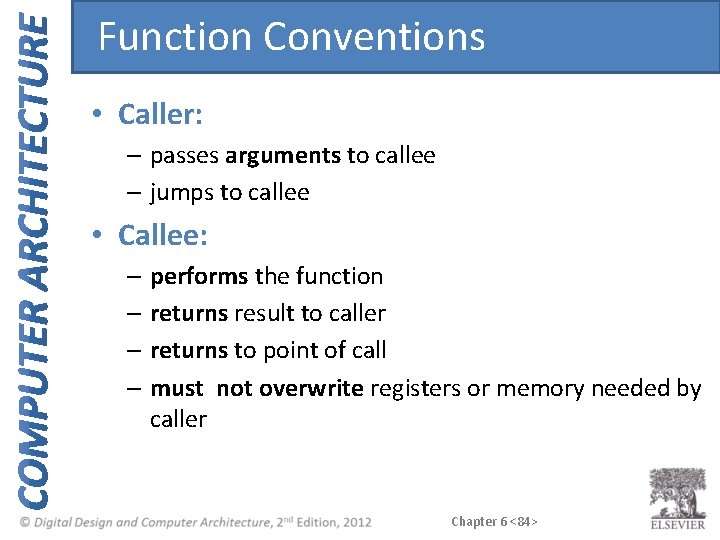

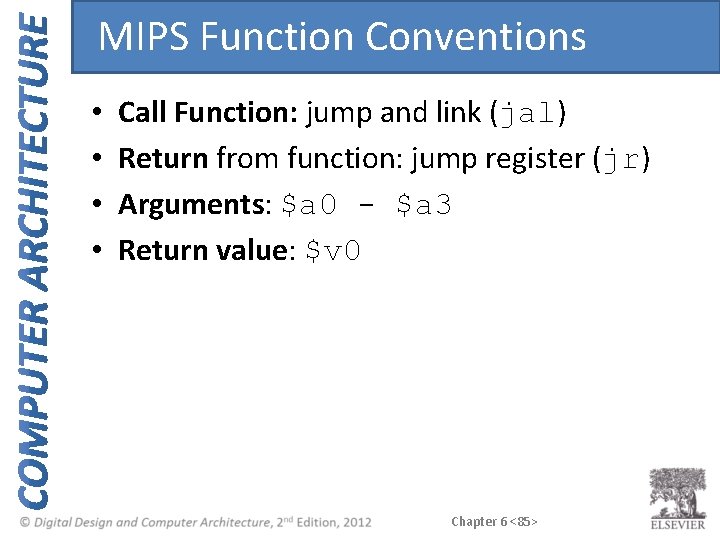

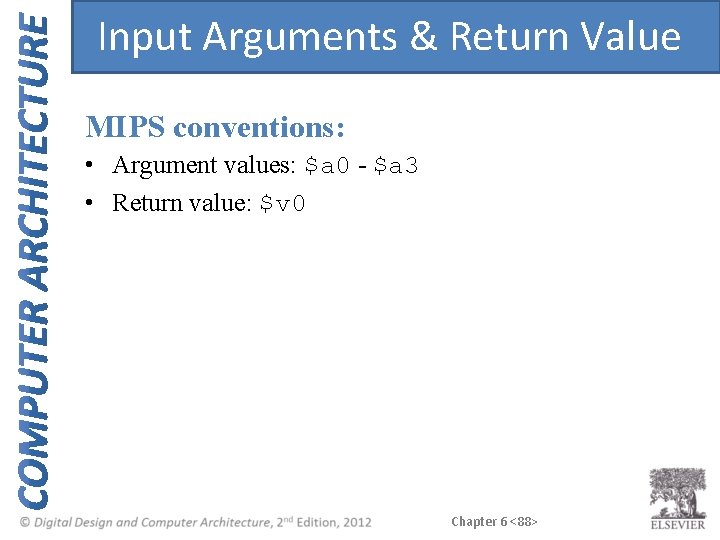

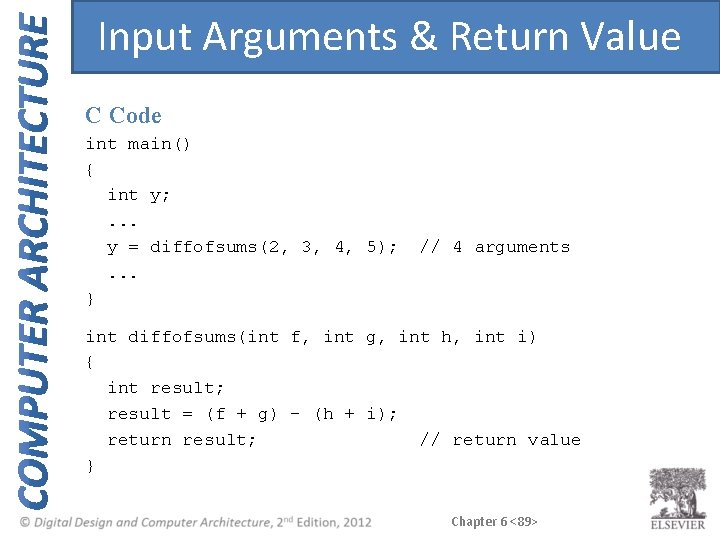

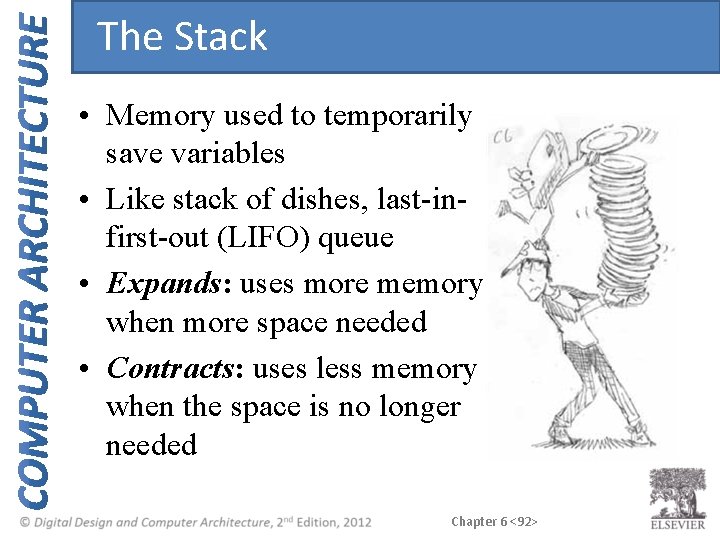

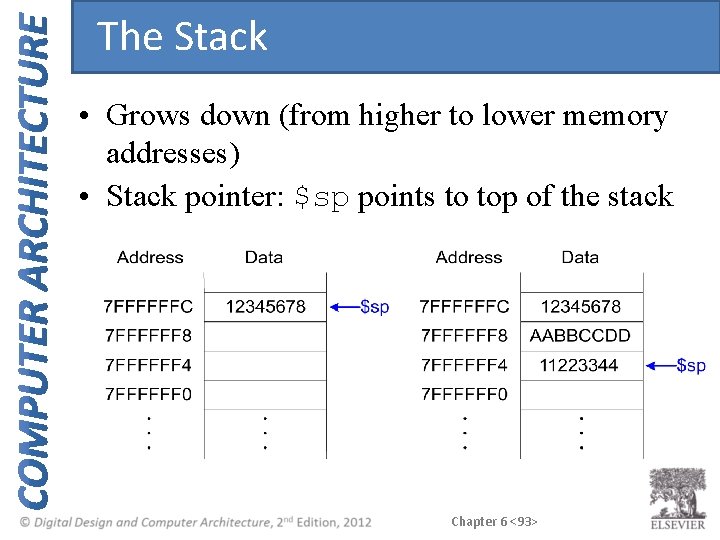

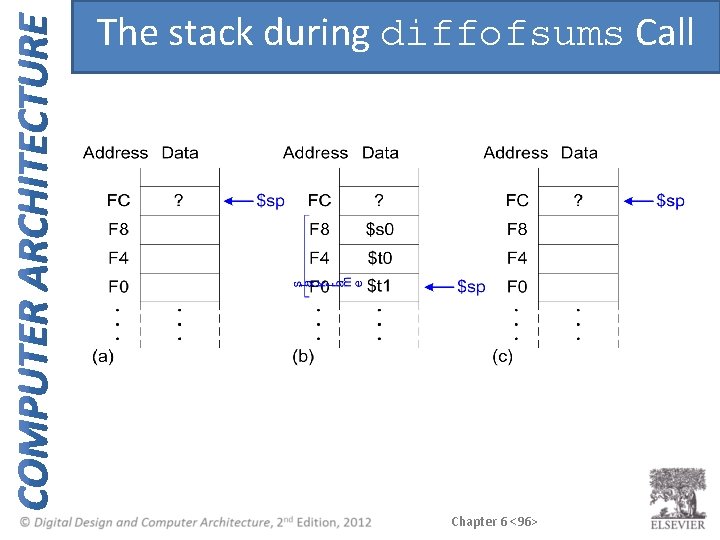

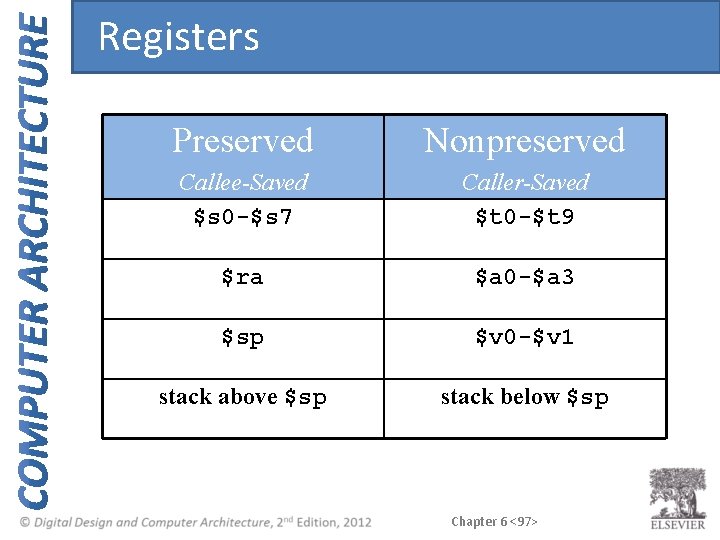

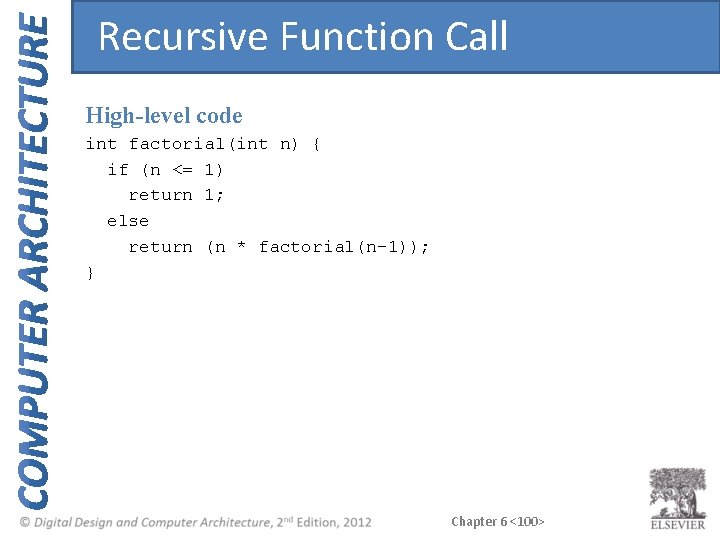

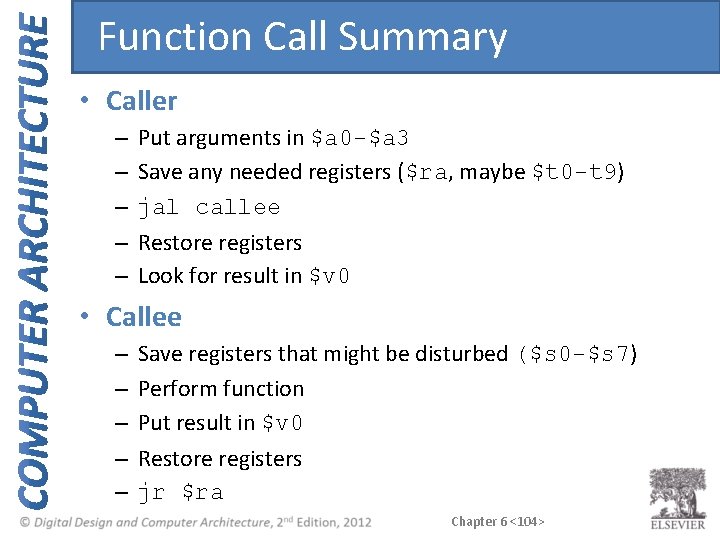

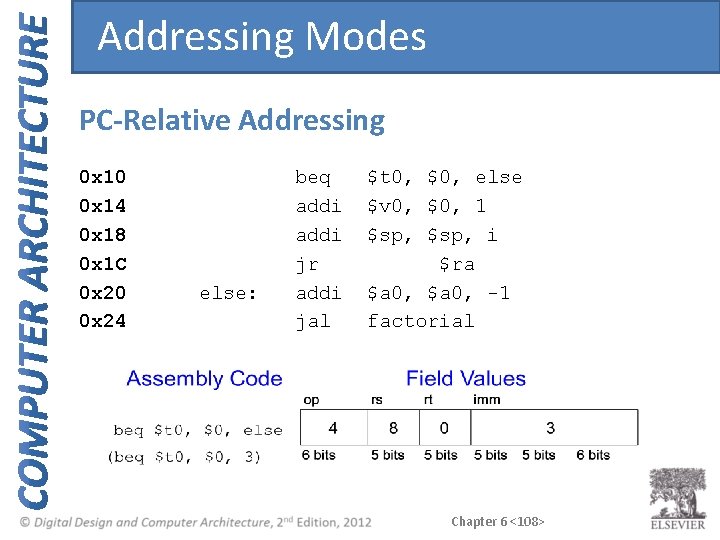

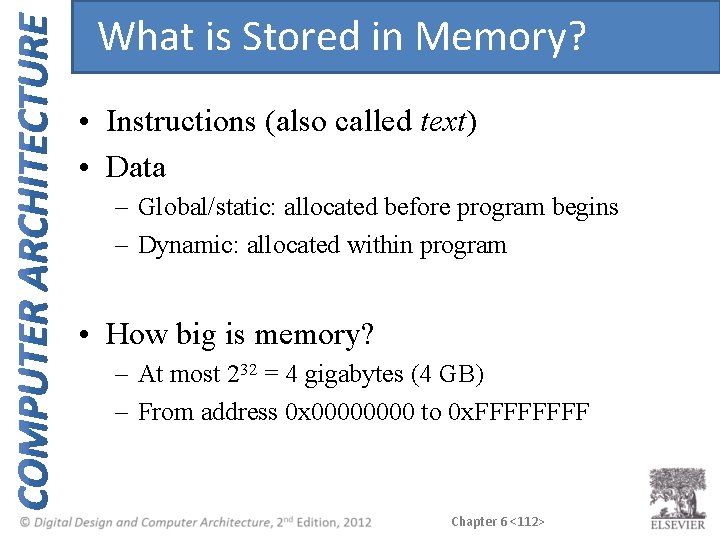

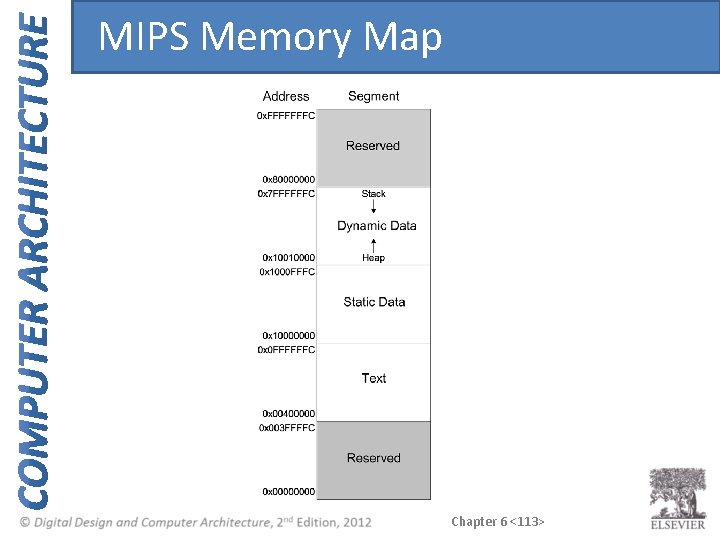

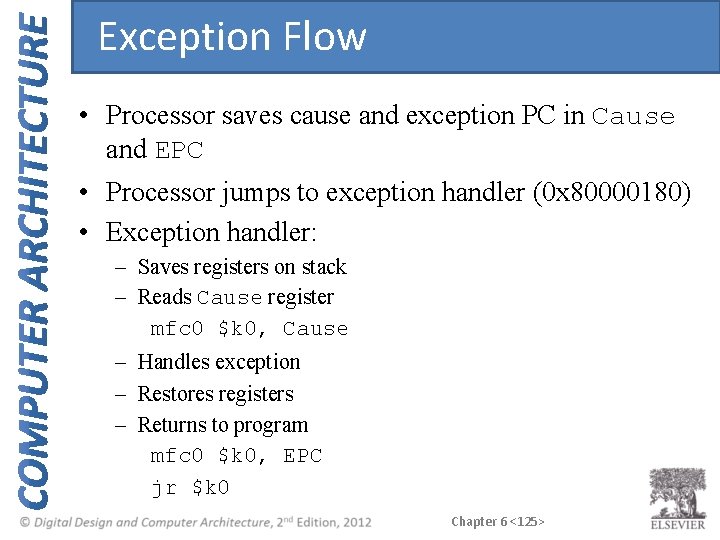

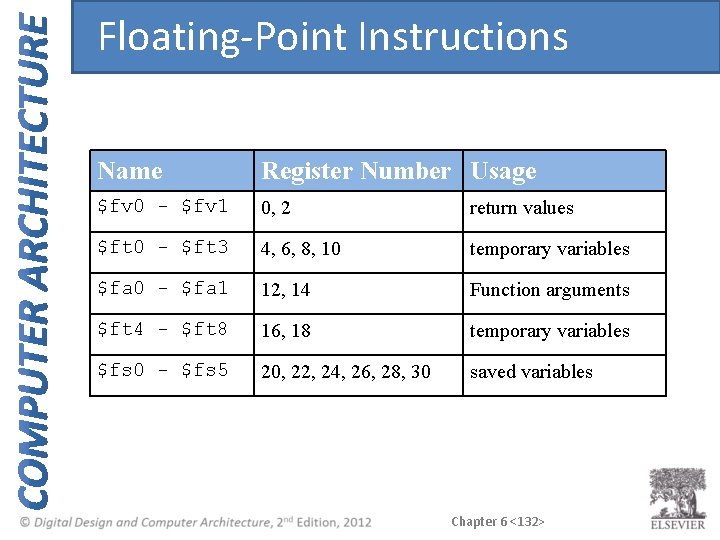

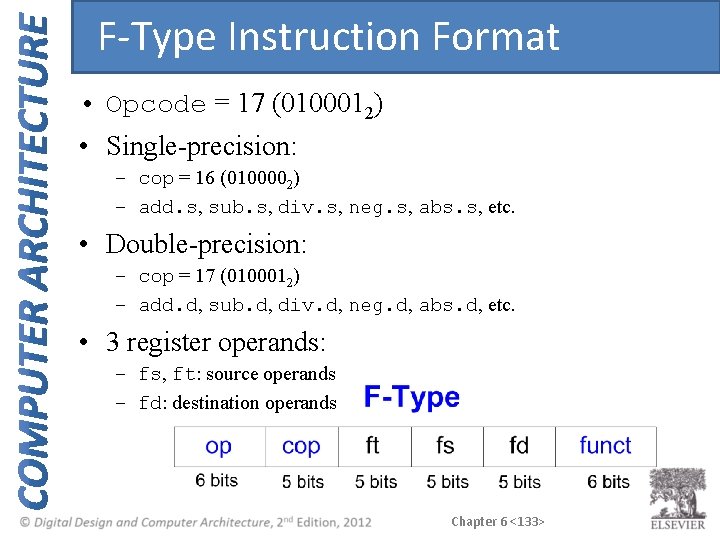

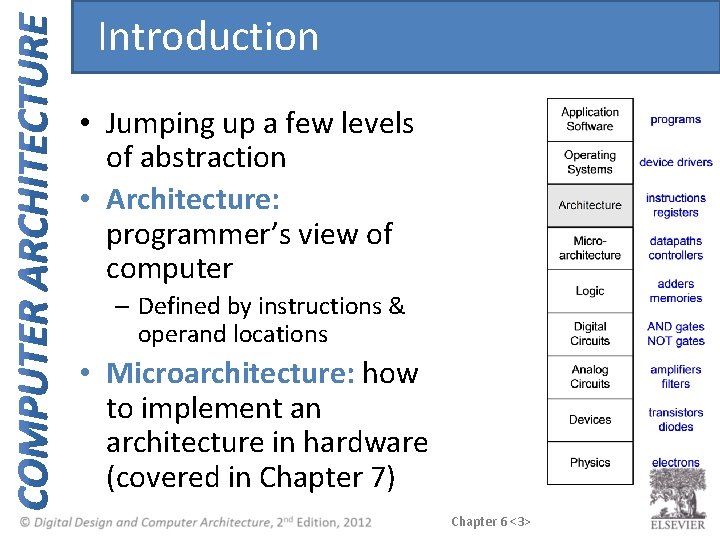

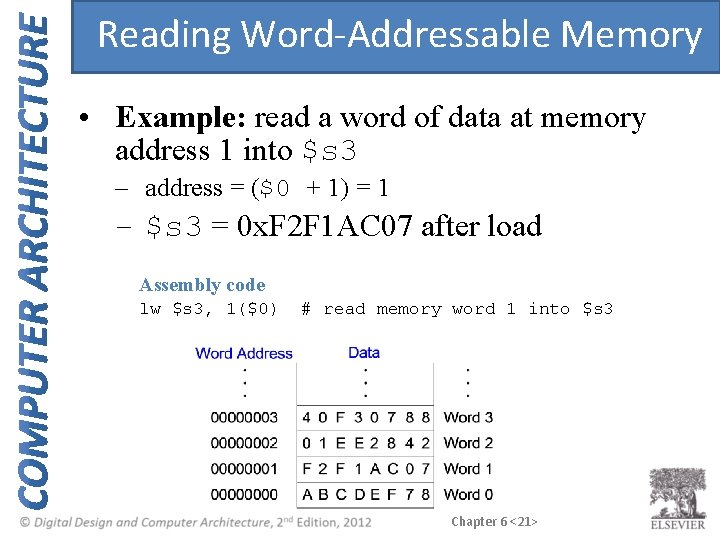

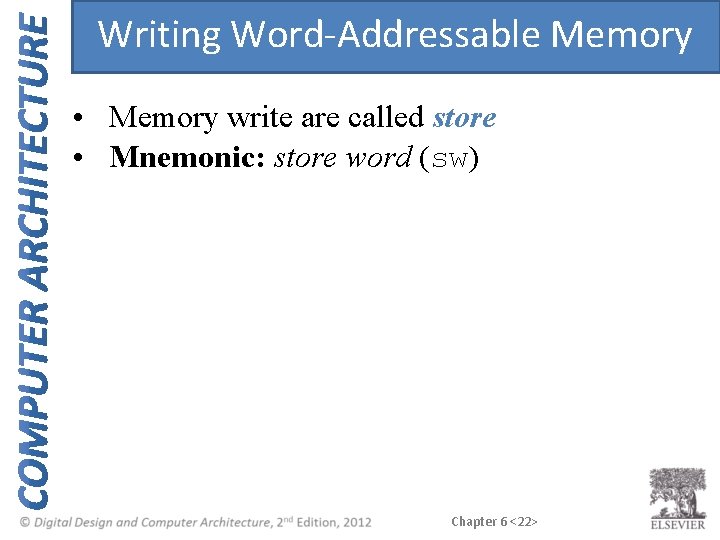

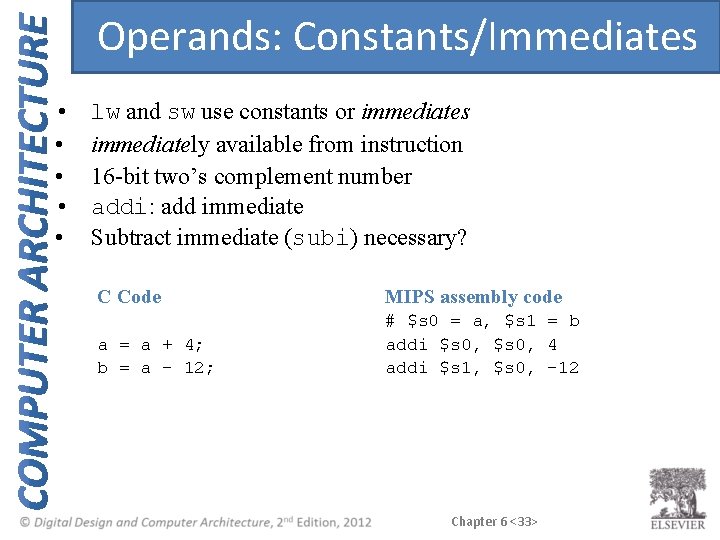

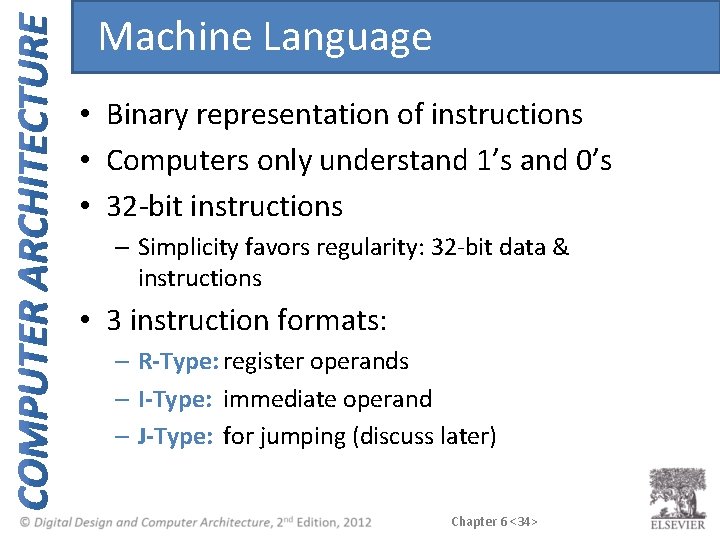

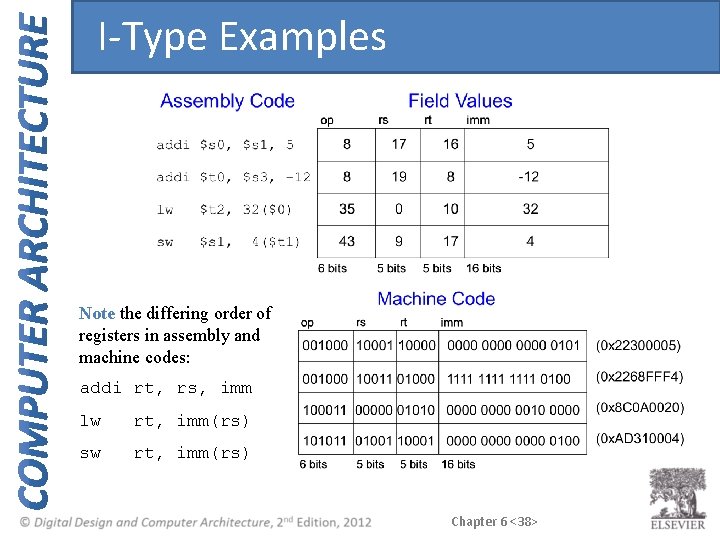

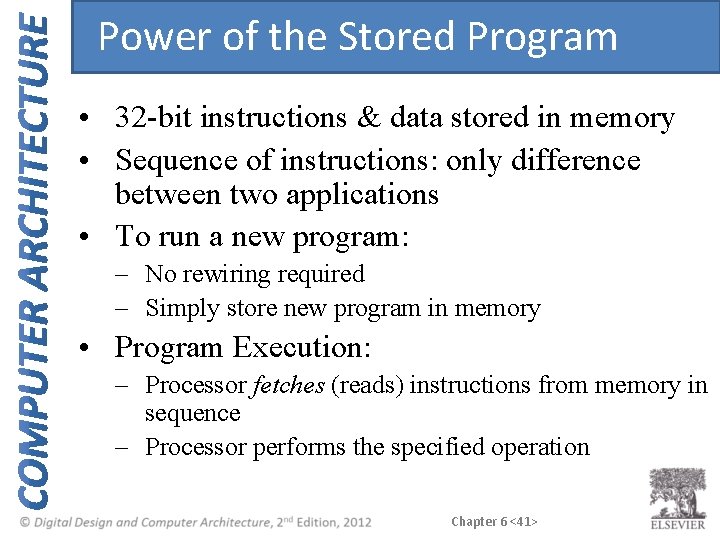

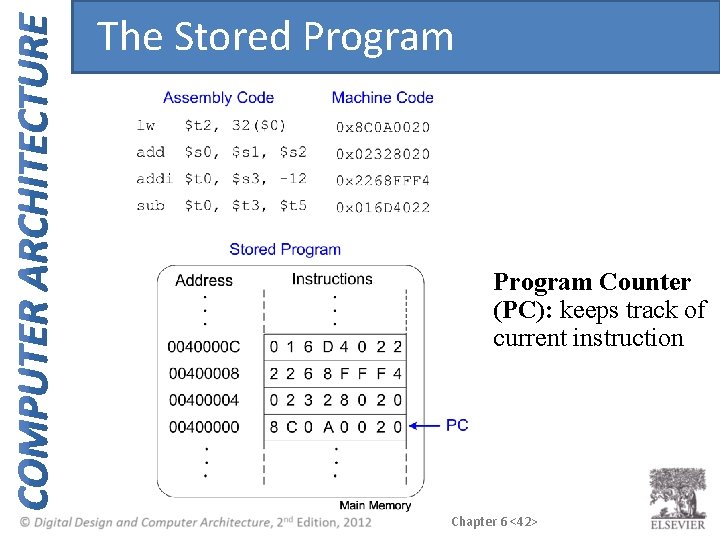

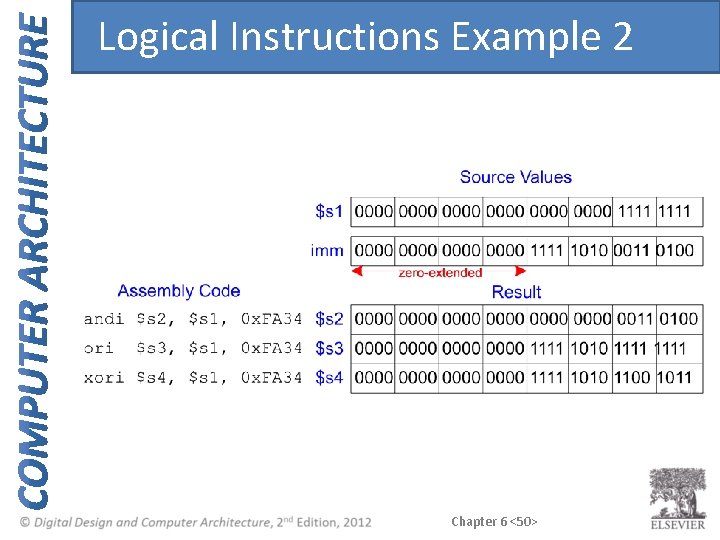

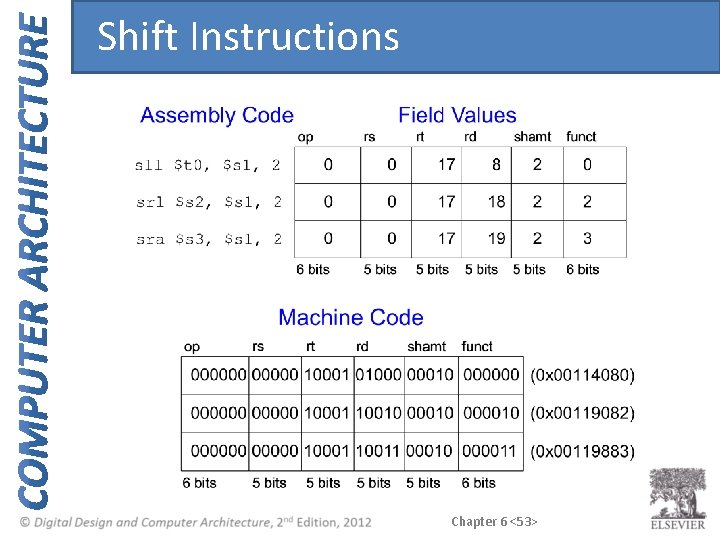

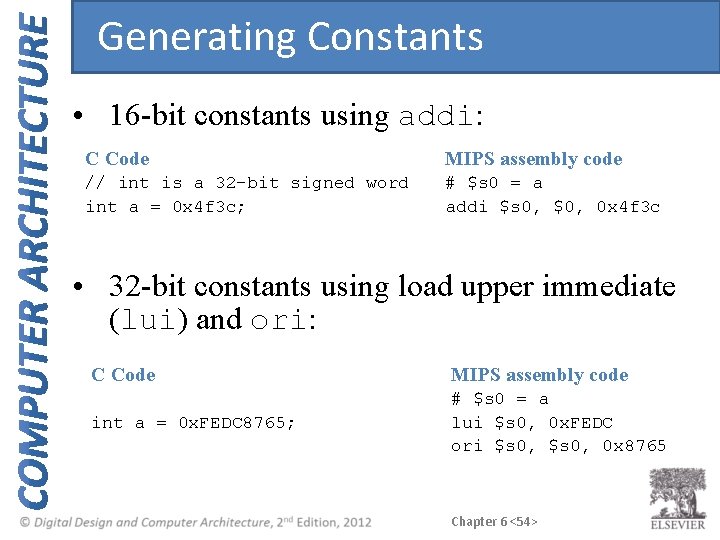

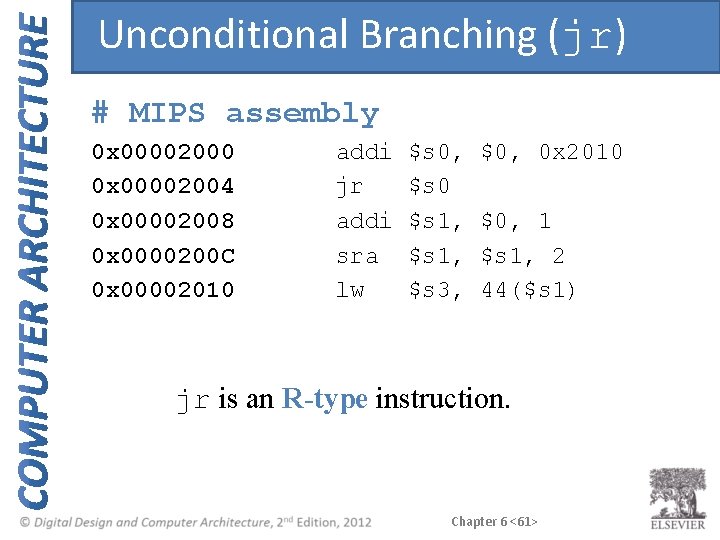

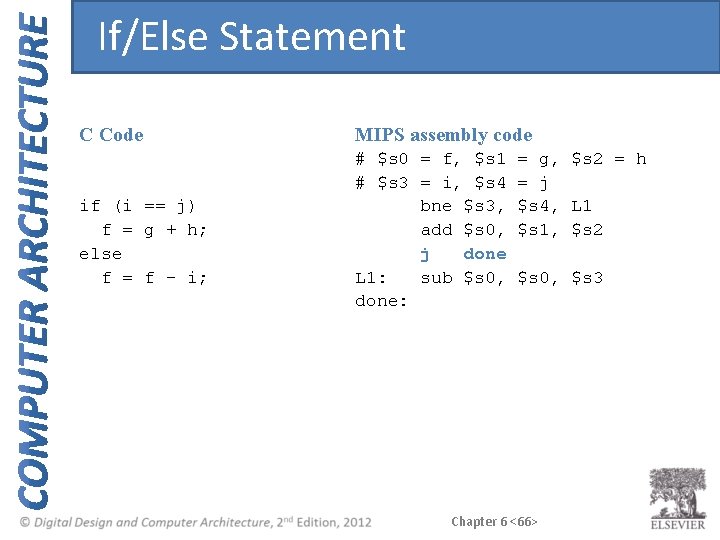

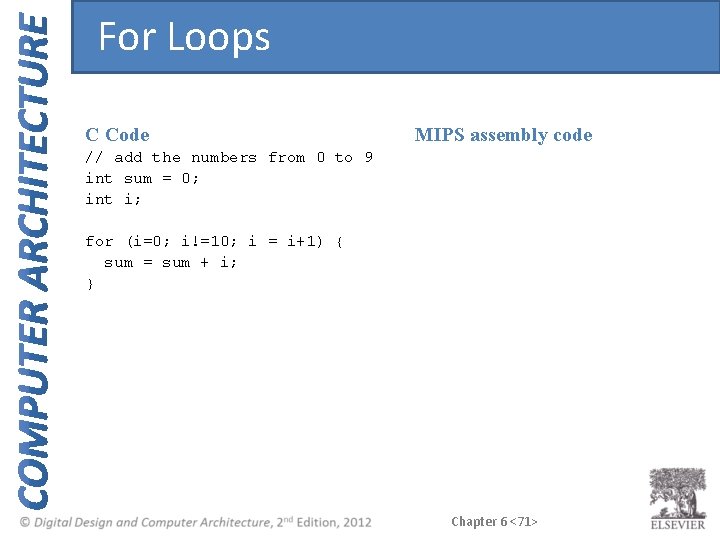

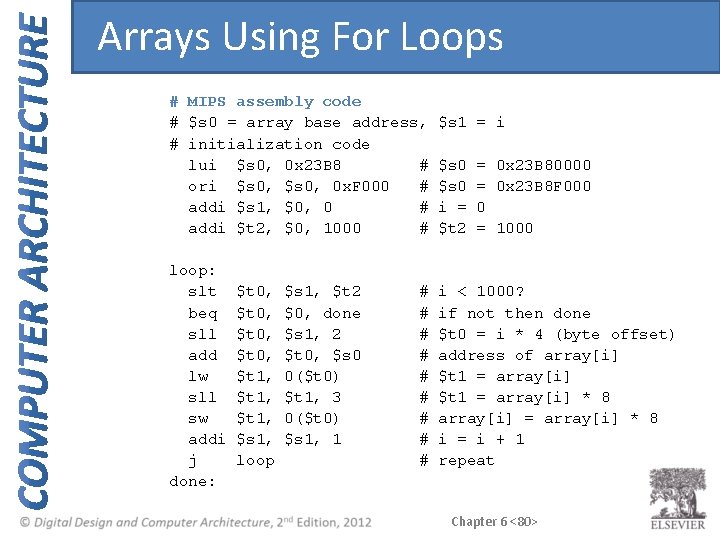

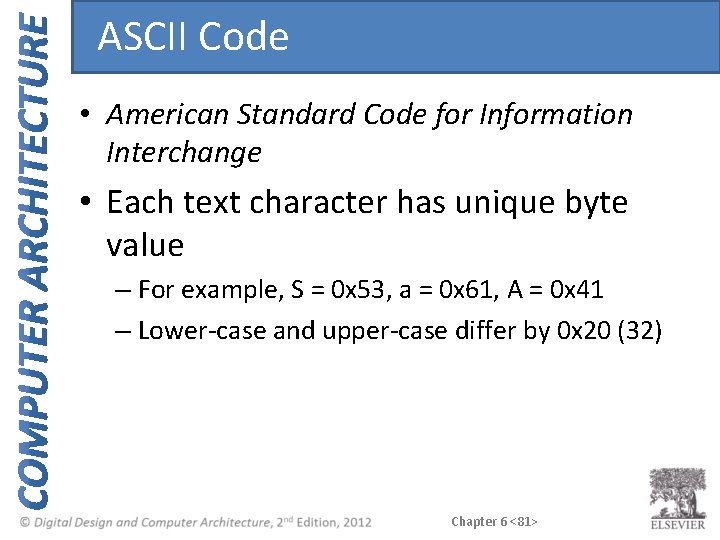

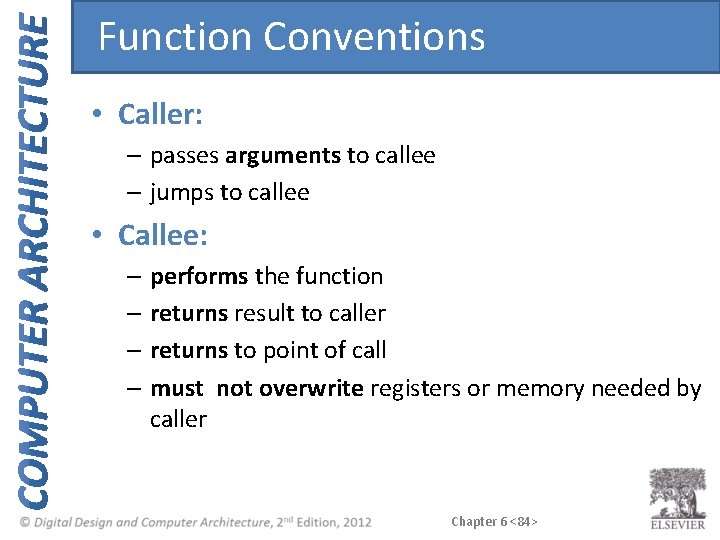

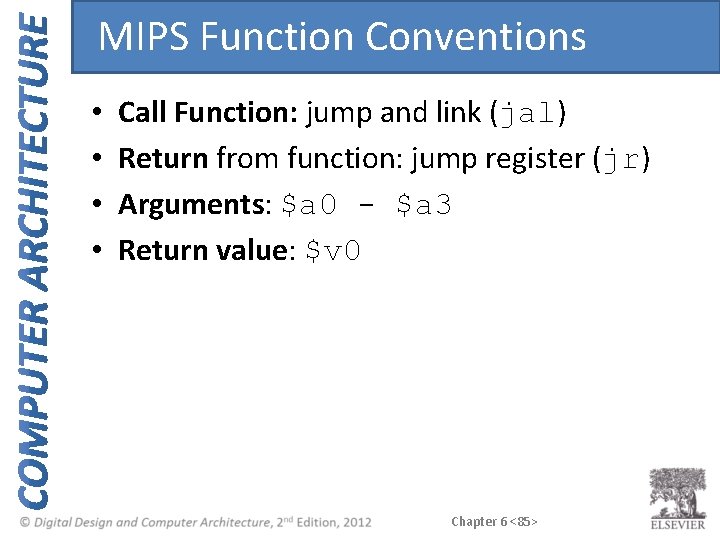

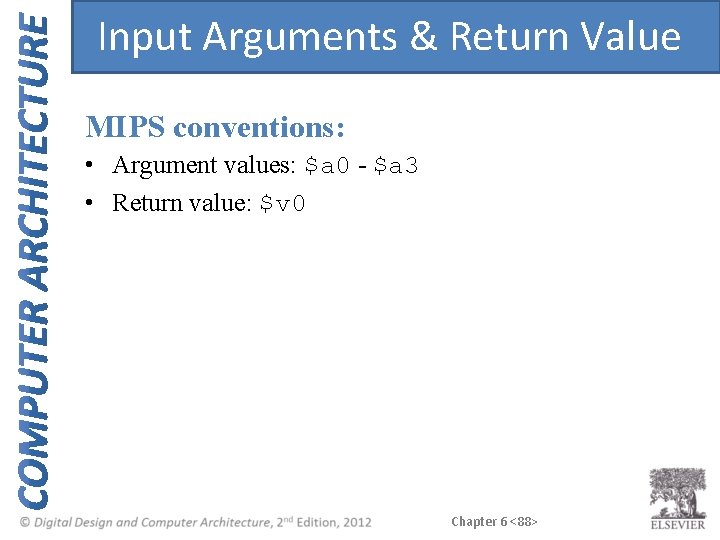

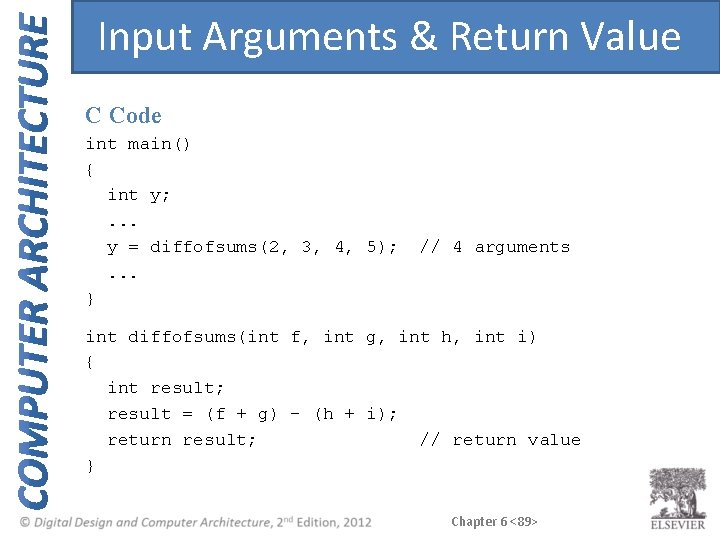

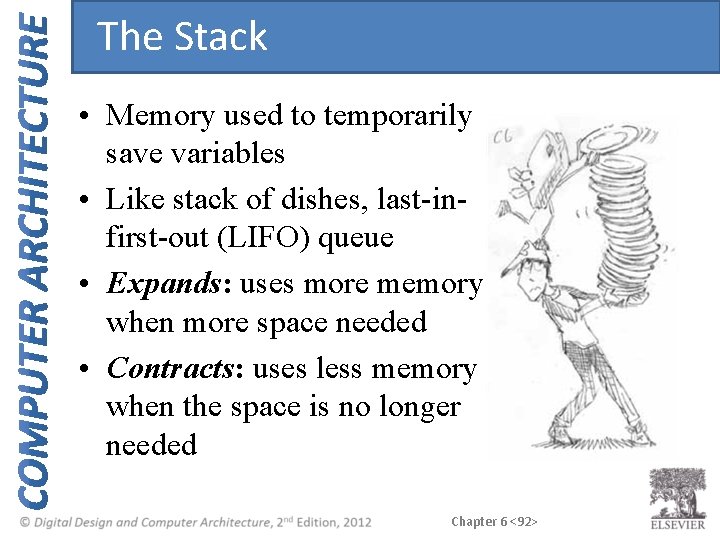

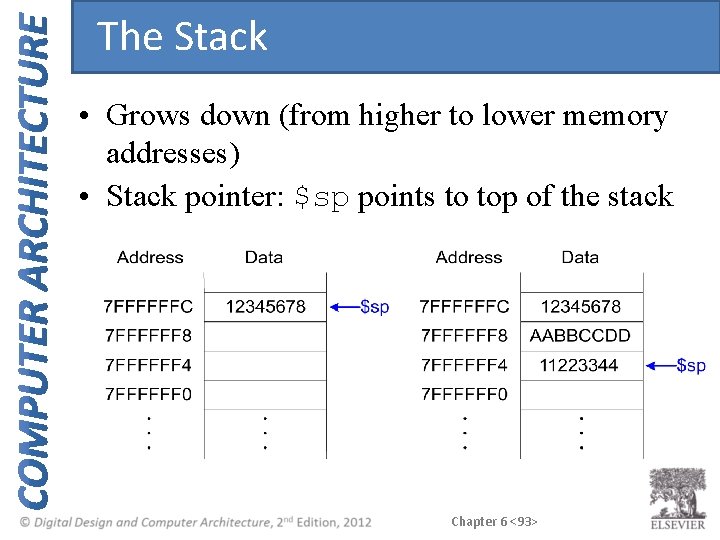

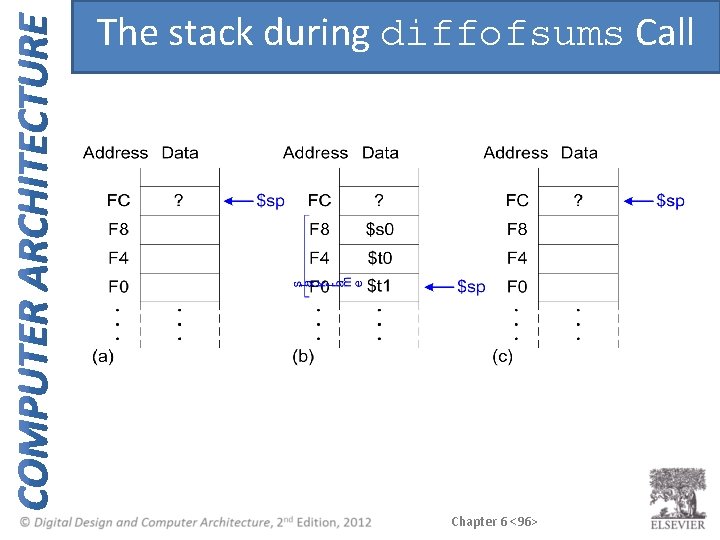

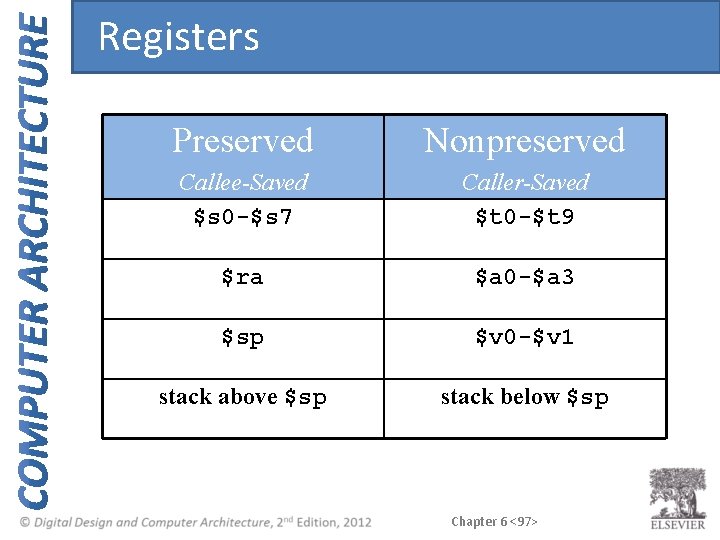

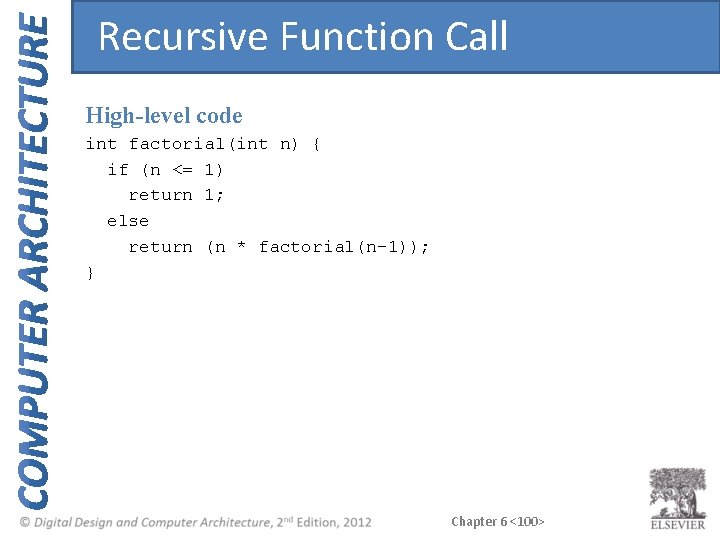

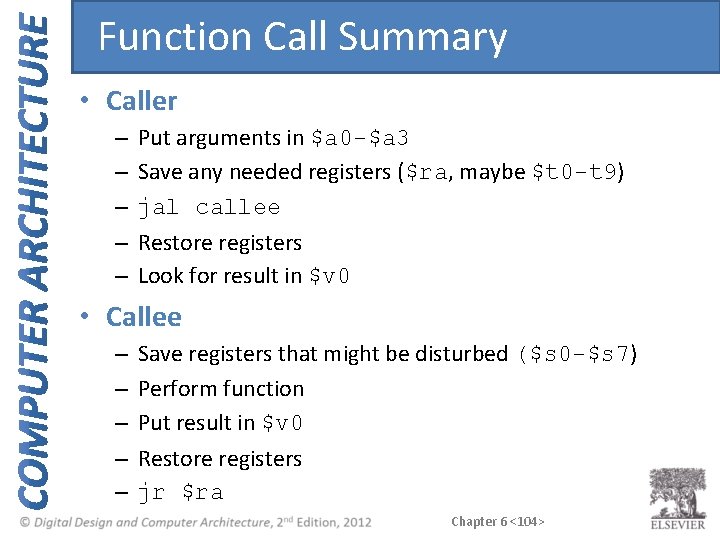

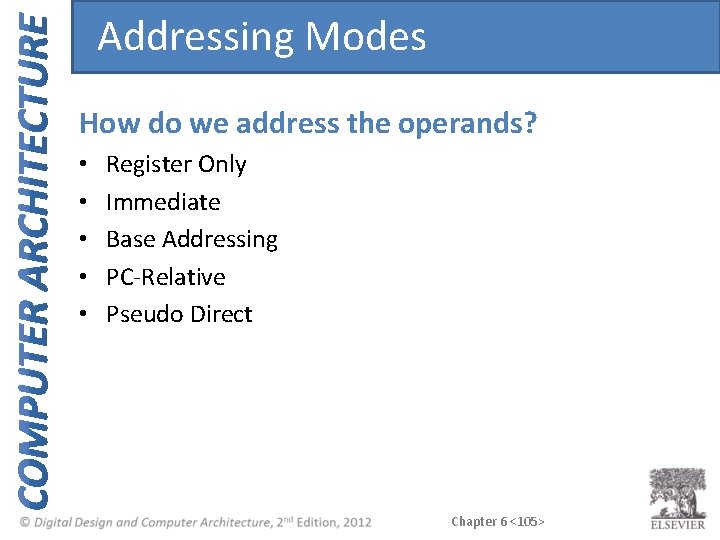

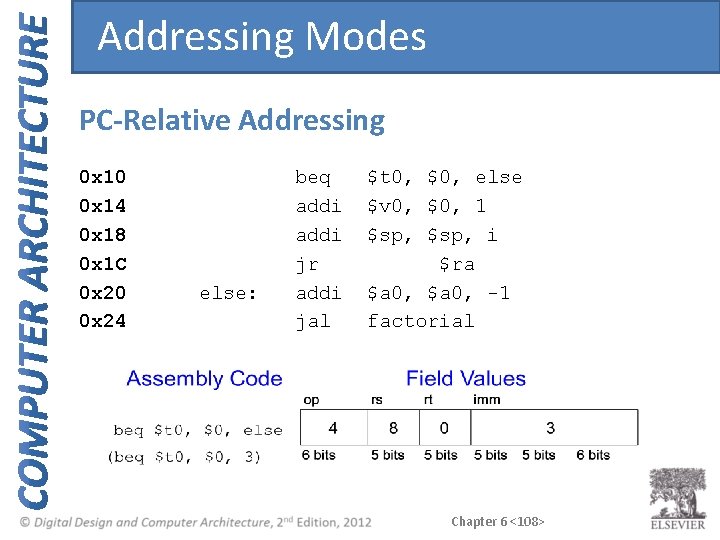

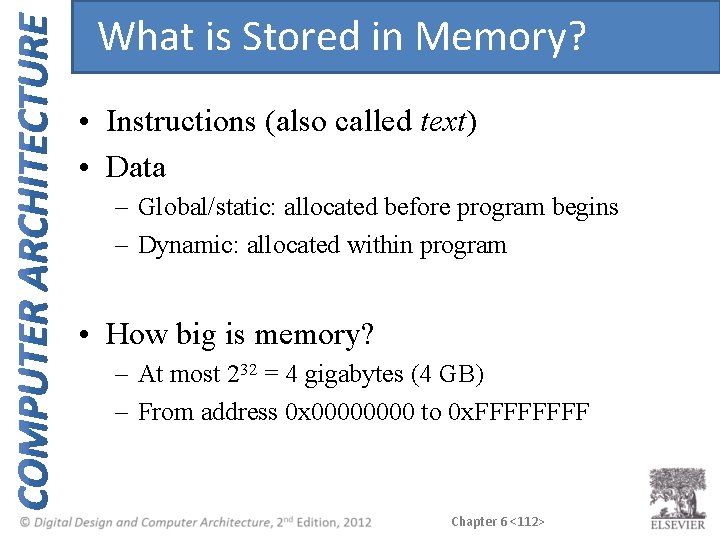

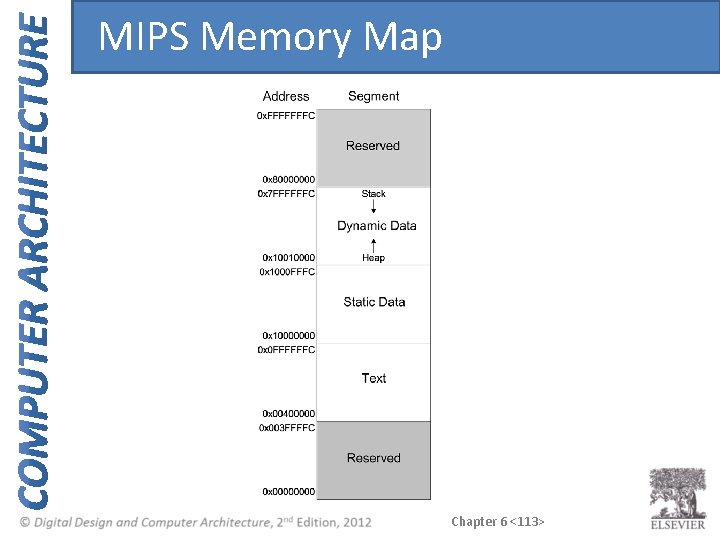

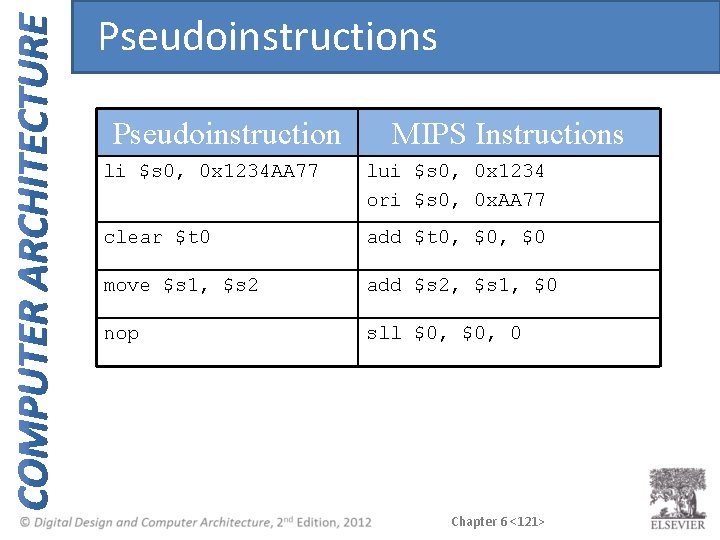

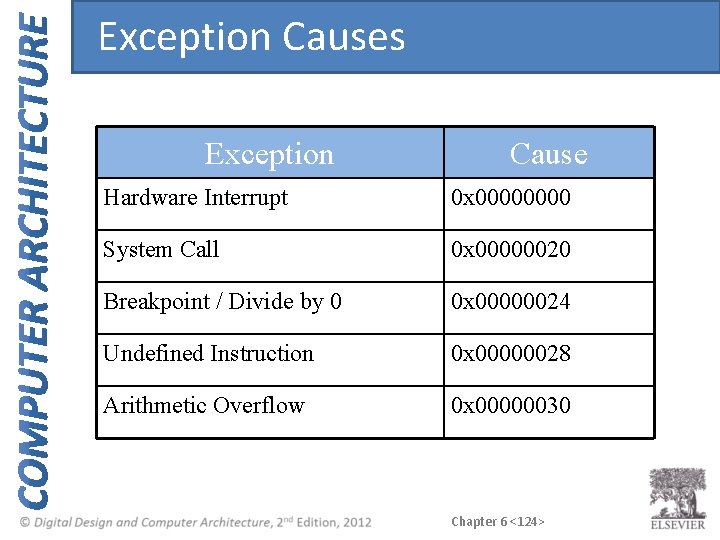

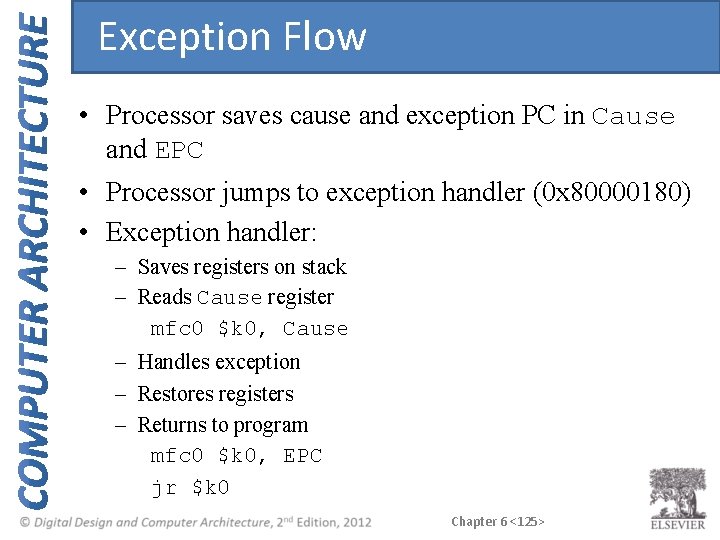

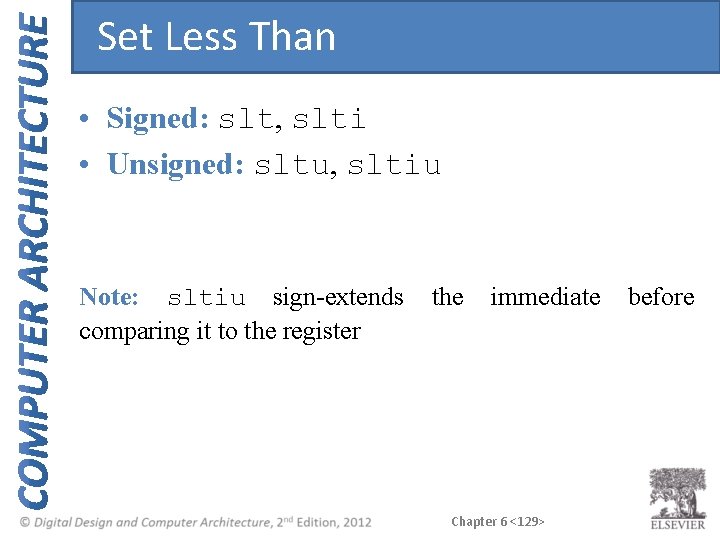

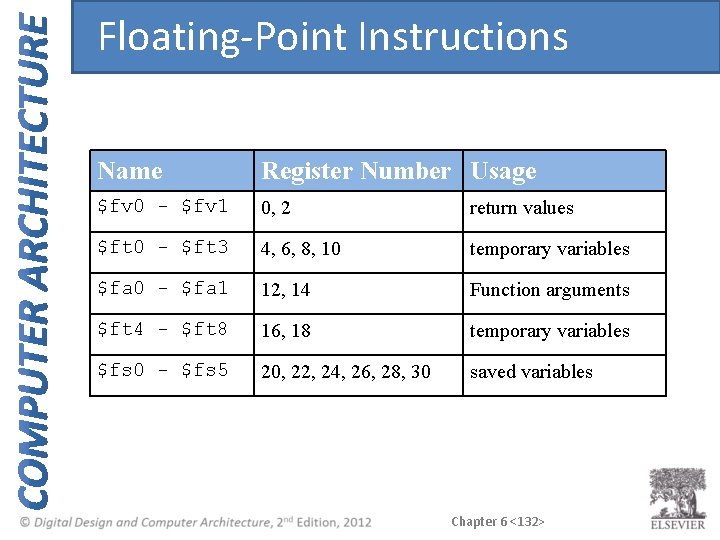

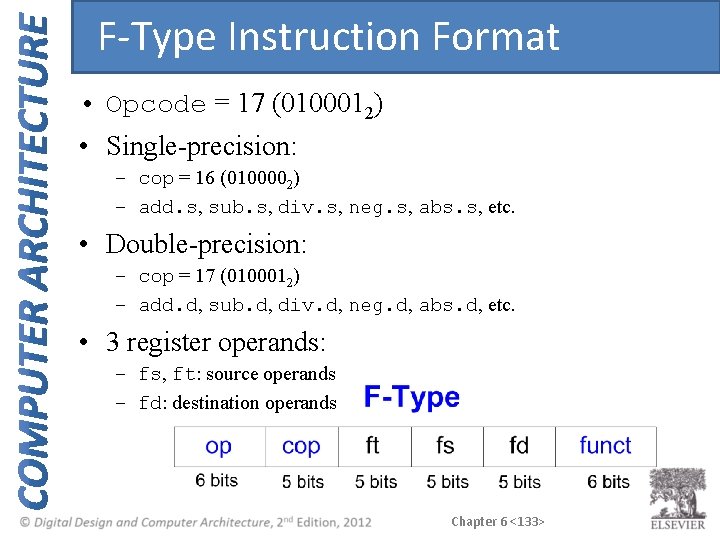

Accessing Arrays // C Code int array[5]; array[0] = array[0] * 2; array[1] = array[1] * 2; Chapter 6 <77>

![Accessing Arrays C Code int array5 array0 array0 2 array1 Accessing Arrays // C Code int array[5]; array[0] = array[0] * 2; array[1] =](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/91b4629b1b7b3ed4fff3b8edaf659558/image-78.jpg)

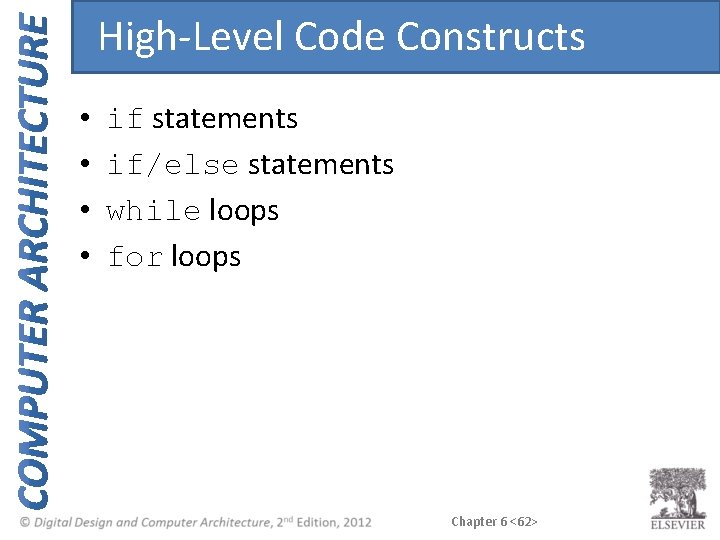

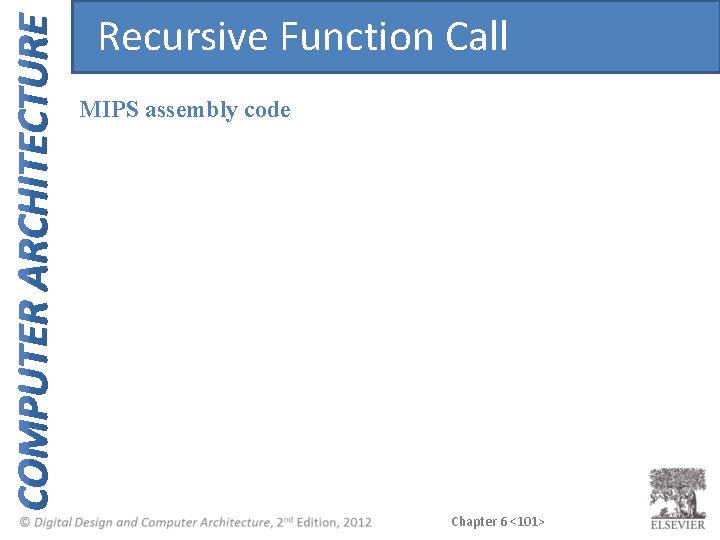

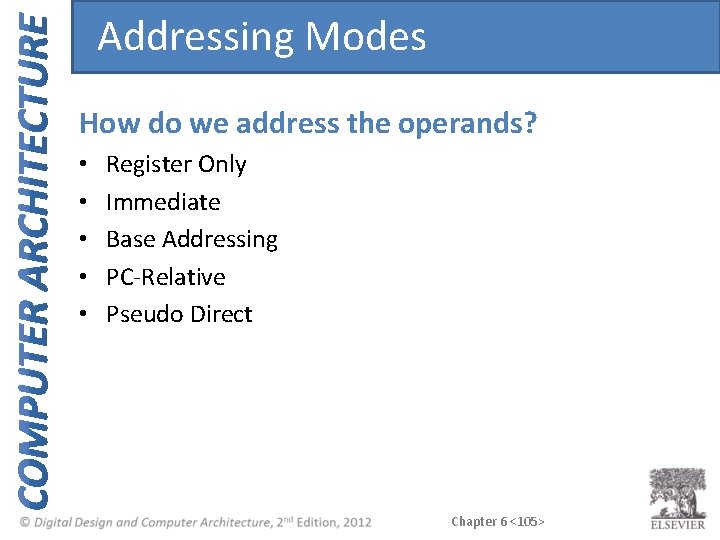

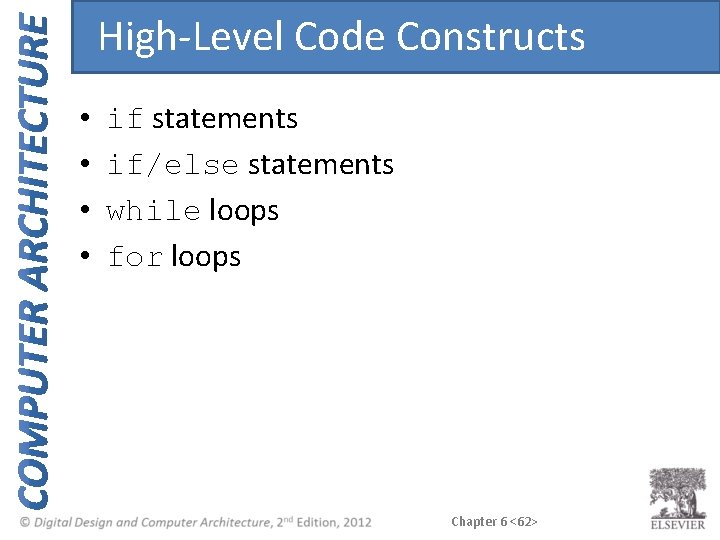

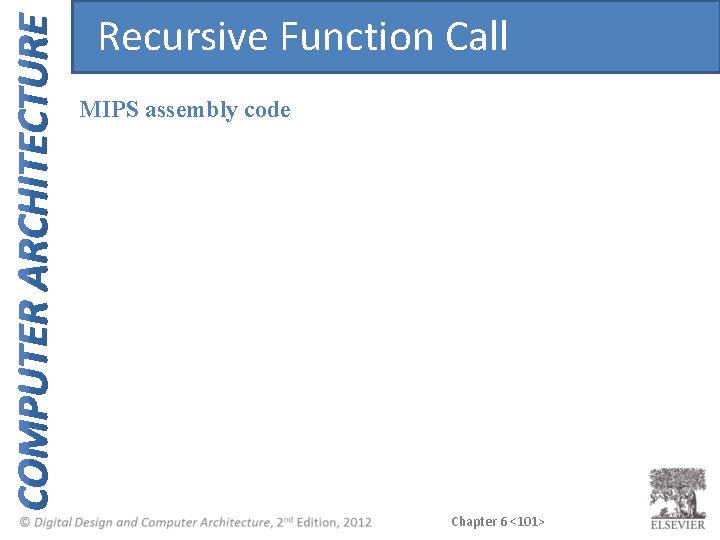

Accessing Arrays // C Code int array[5]; array[0] = array[0] * 2; array[1] = array[1] * 2; # MIPS assembly code # $s 0 = array base address lui $s 0, 0 x 1234 ori $s 0, 0 x 8000 # 0 x 1234 in upper half of $s 0 # 0 x 8000 in lower half of $s 0 lw sll sw $t 1, 0($s 0) $t 1, 1 $t 1, 0($s 0) # $t 1 = array[0] # $t 1 = $t 1 * 2 # array[0] = $t 1 lw sll sw $t 1, 4($s 0) $t 1, 1 $t 1, 4($s 0) # $t 1 = array[1] # $t 1 = $t 1 * 2 # array[1] = $t 1 Chapter 6 <78>

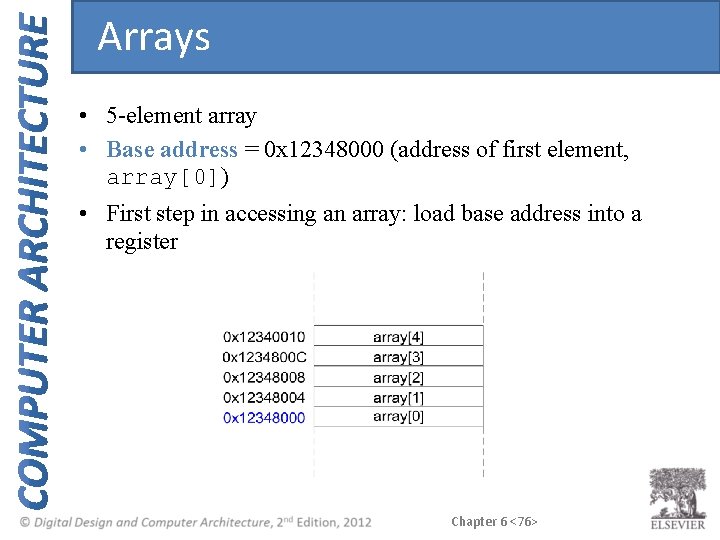

![Arrays using For Loops C Code int array1000 int i for i0 i Arrays using For Loops // C Code int array[1000]; int i; for (i=0; i](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/91b4629b1b7b3ed4fff3b8edaf659558/image-79.jpg)

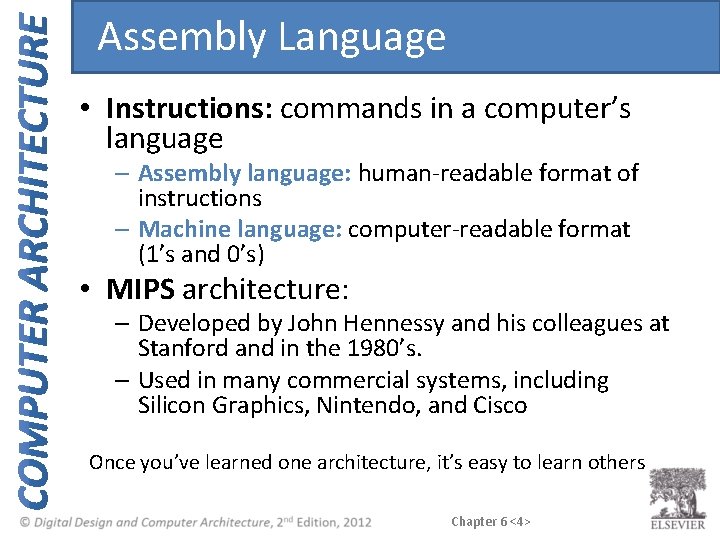

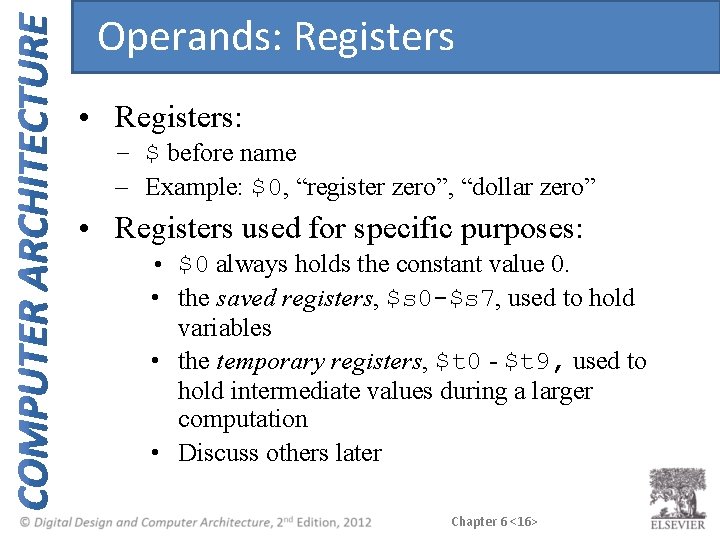

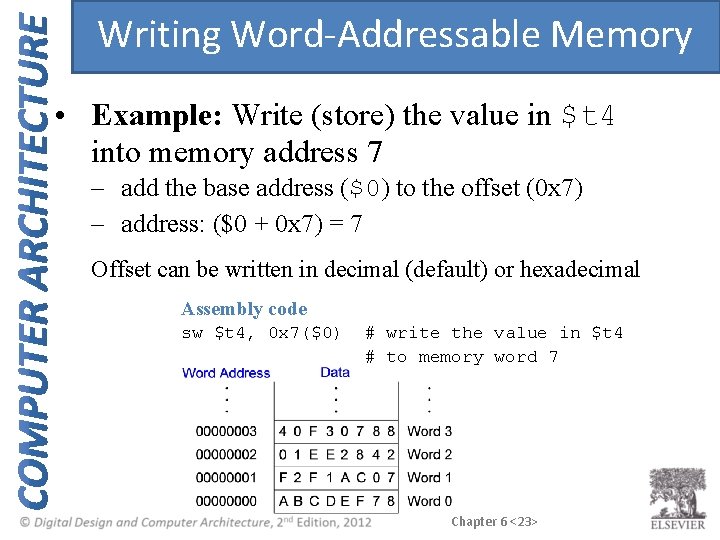

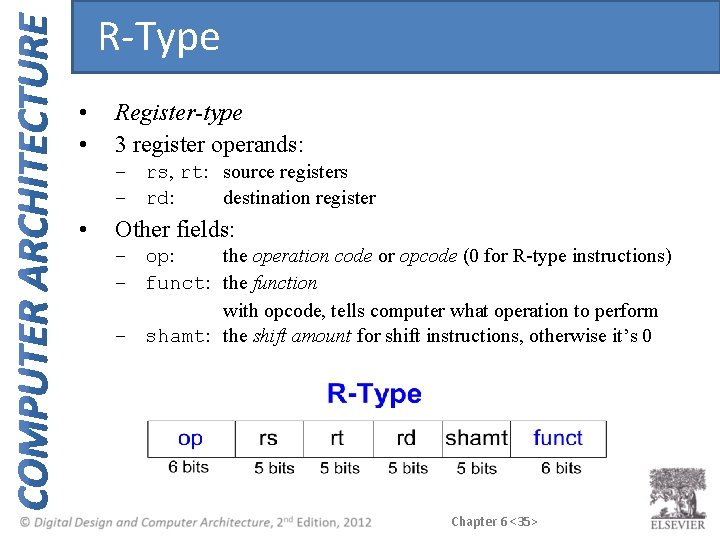

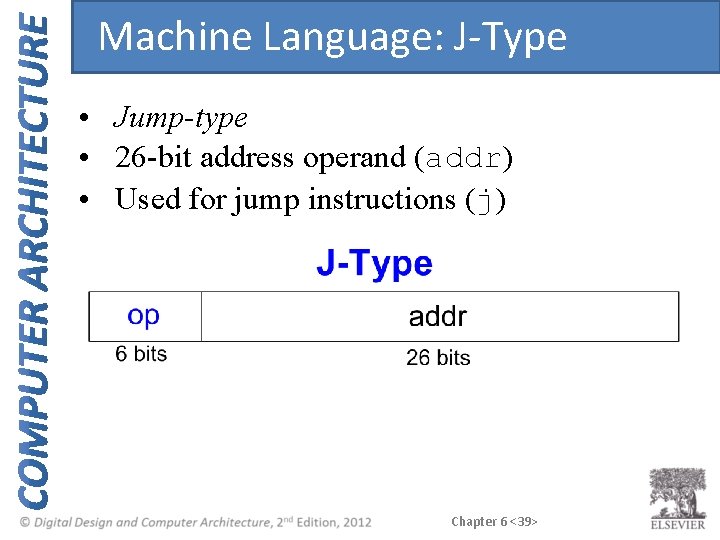

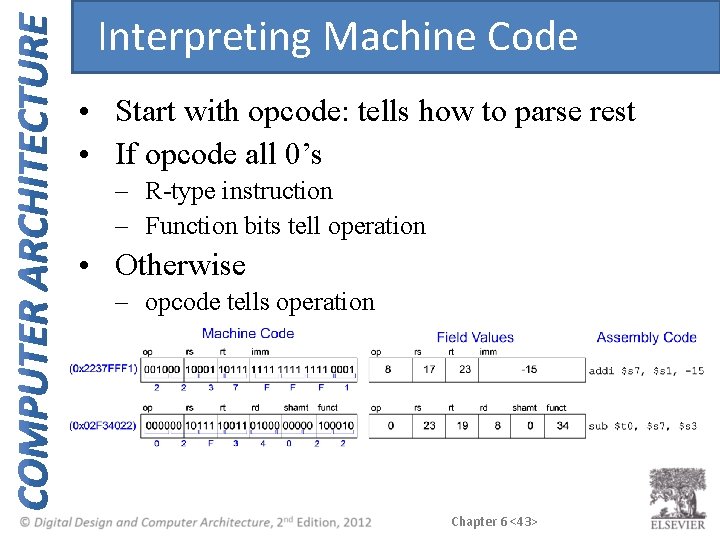

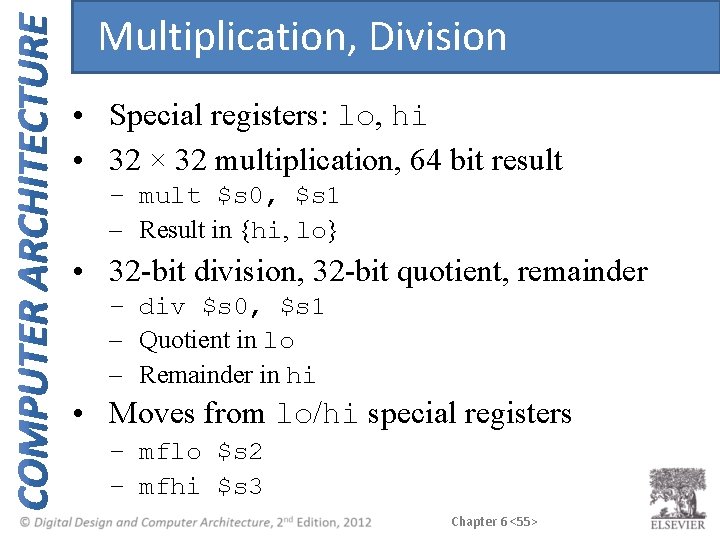

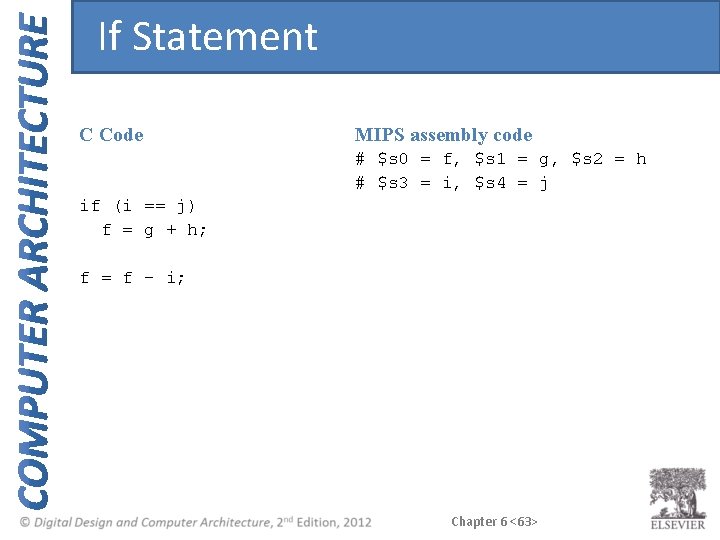

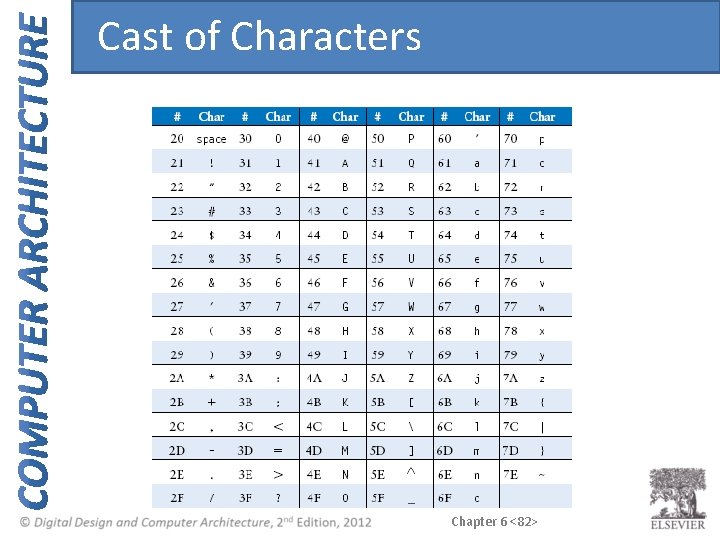

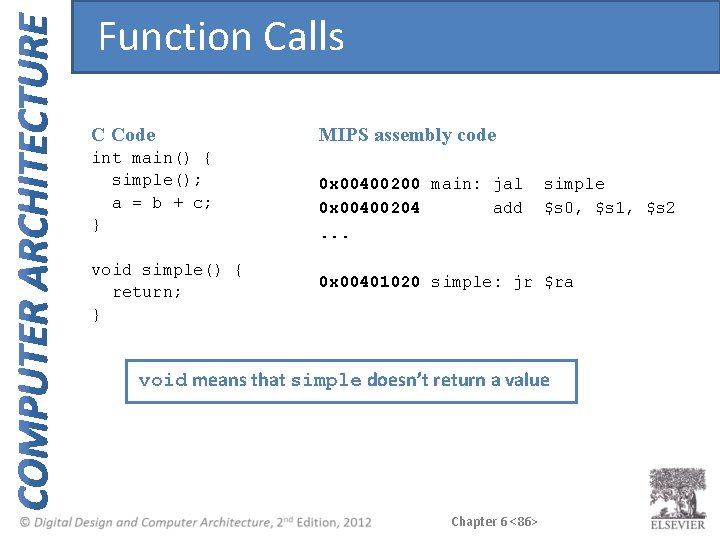

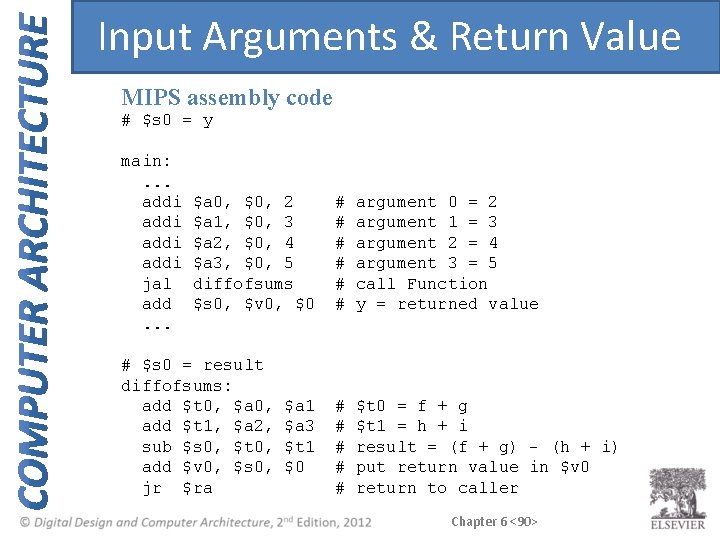

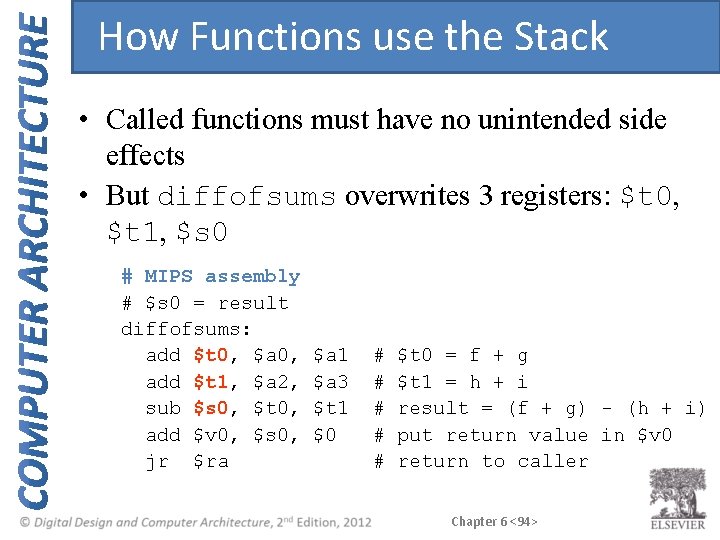

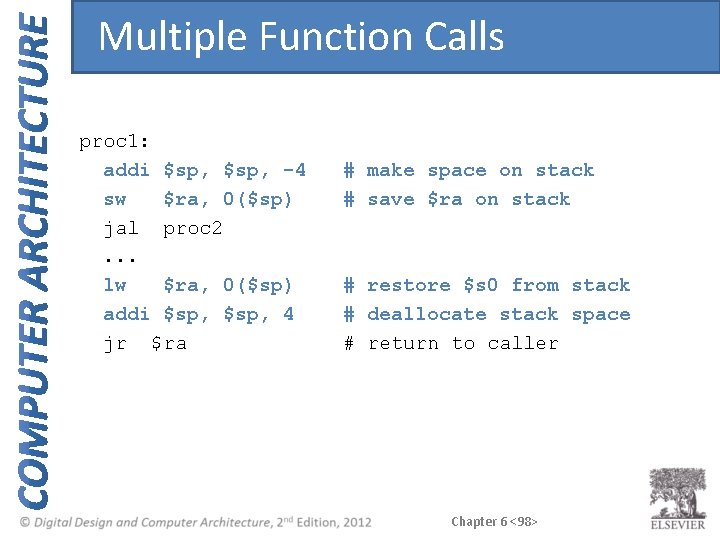

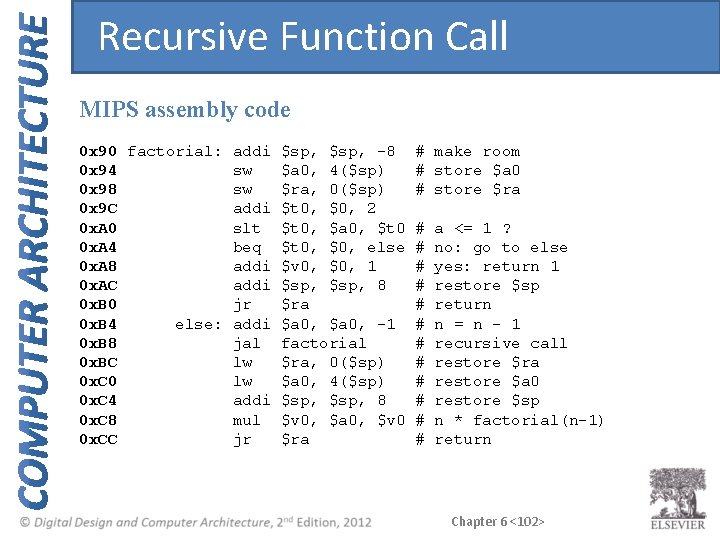

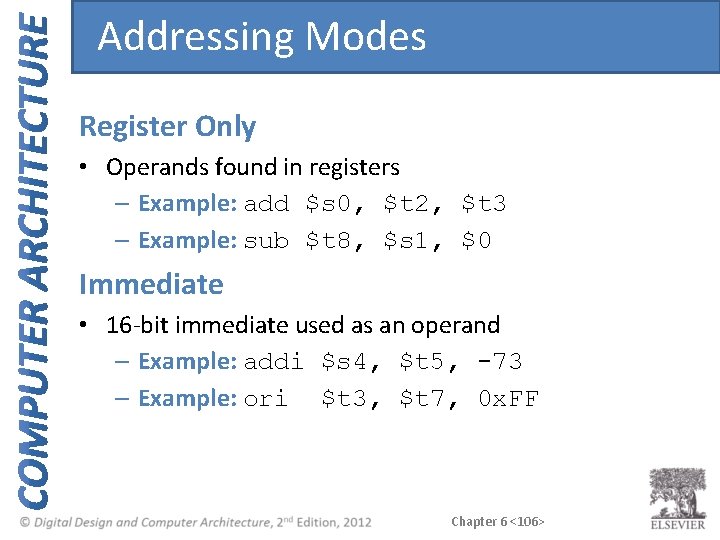

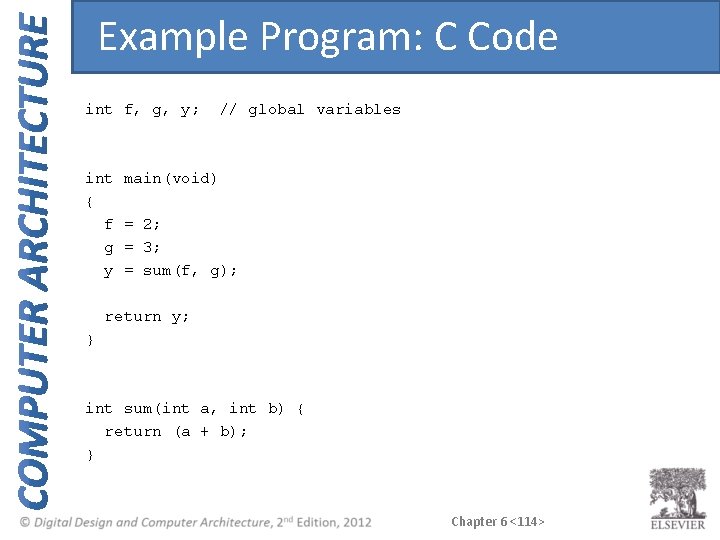

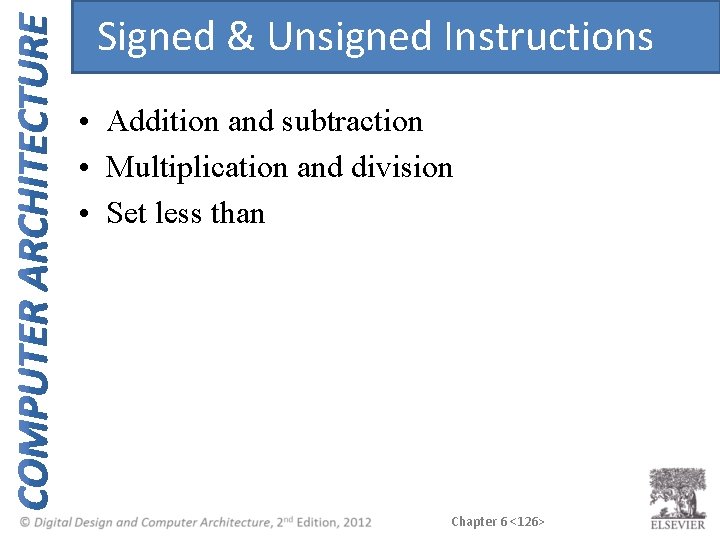

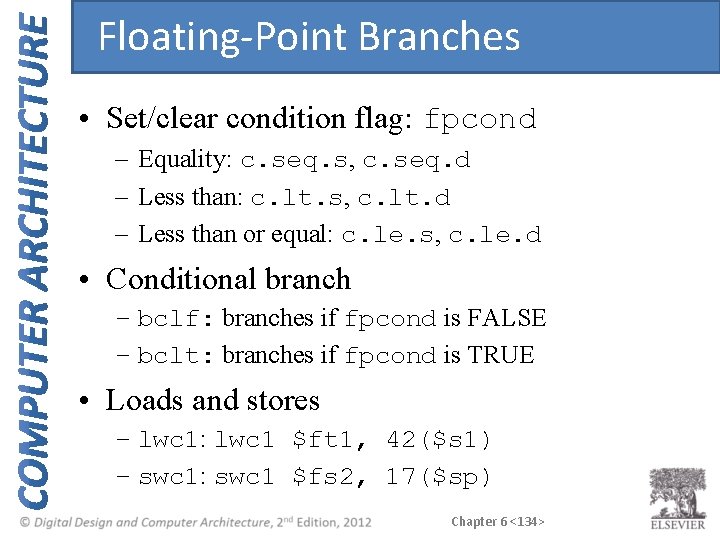

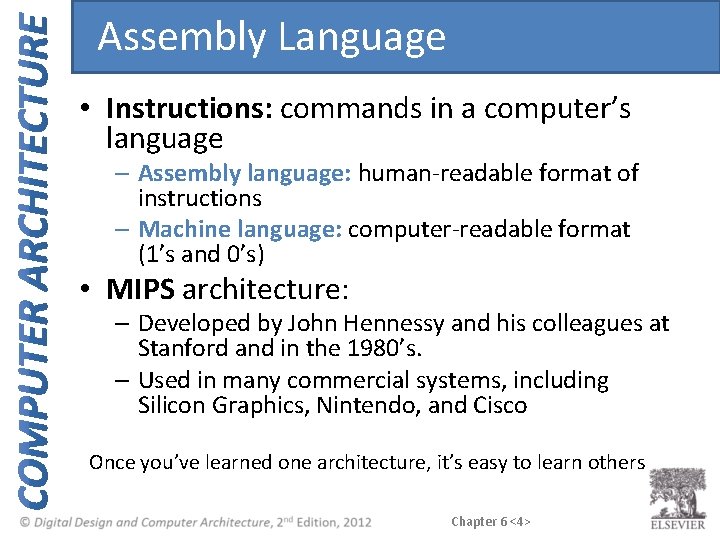

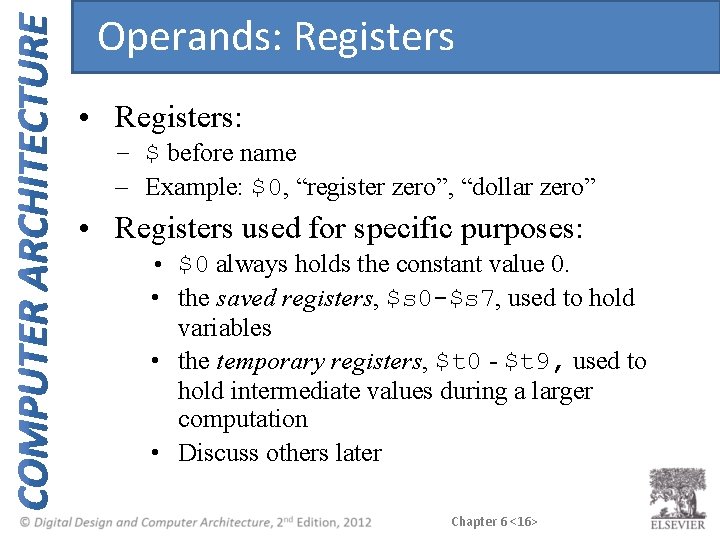

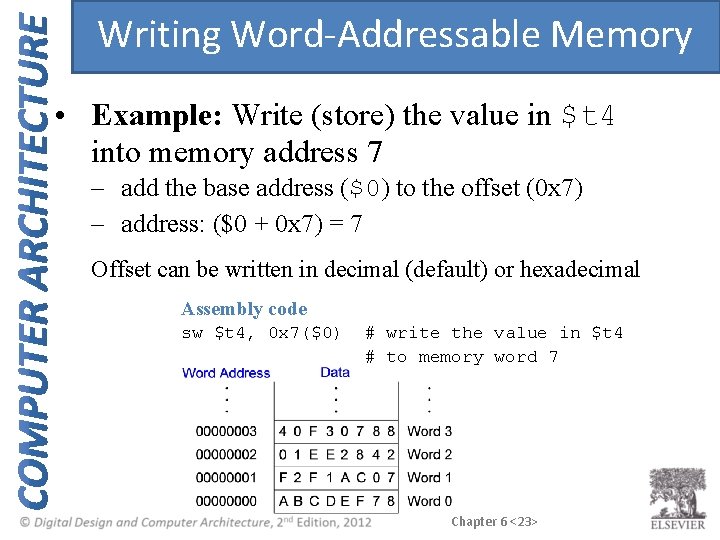

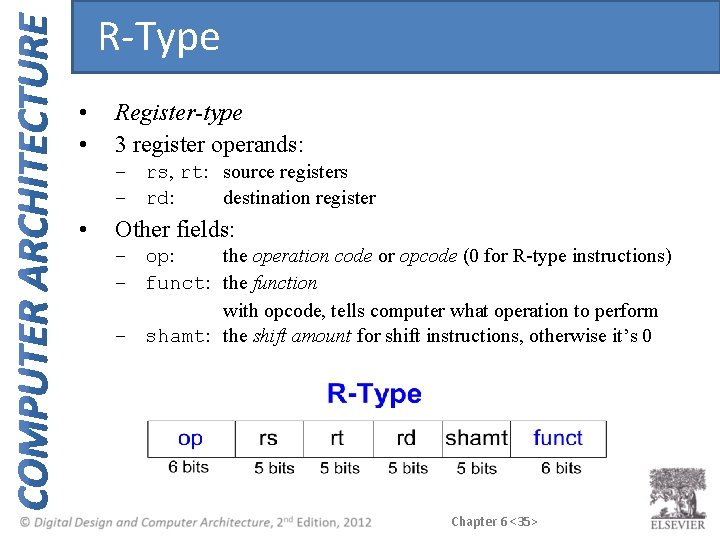

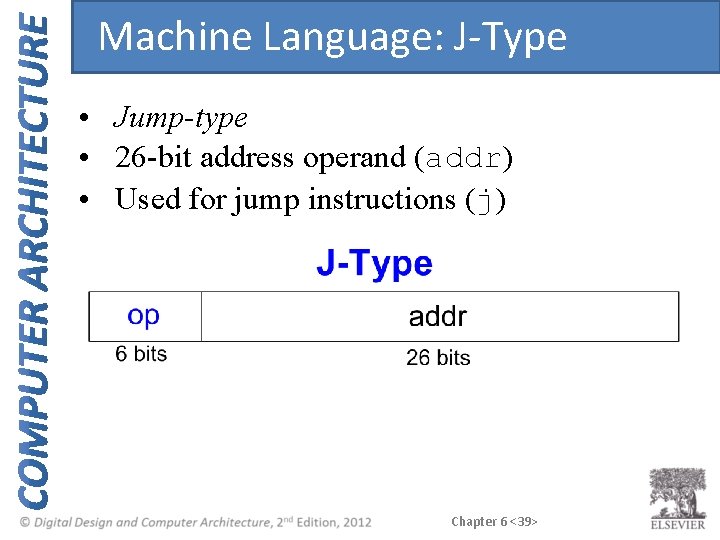

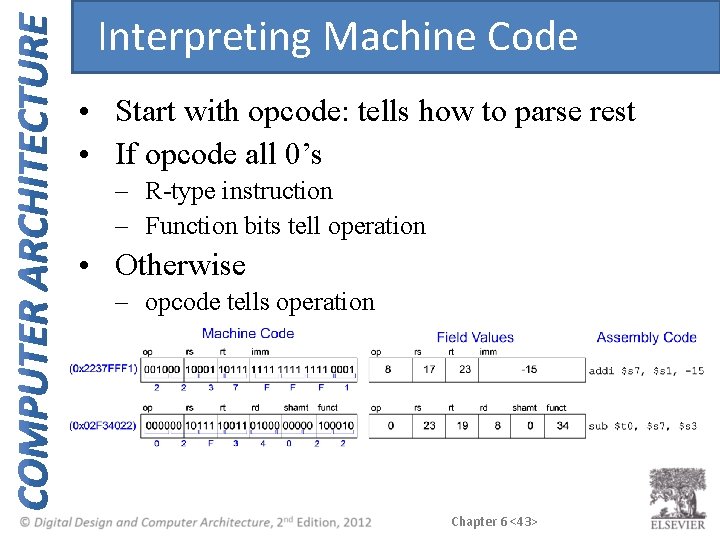

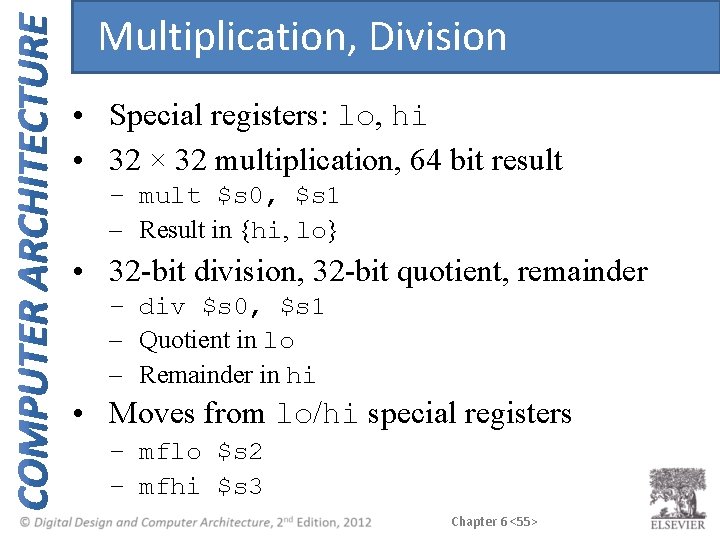

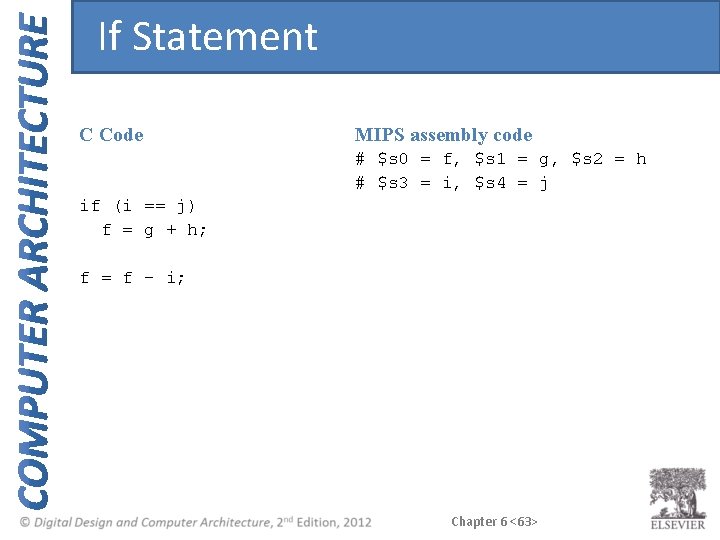

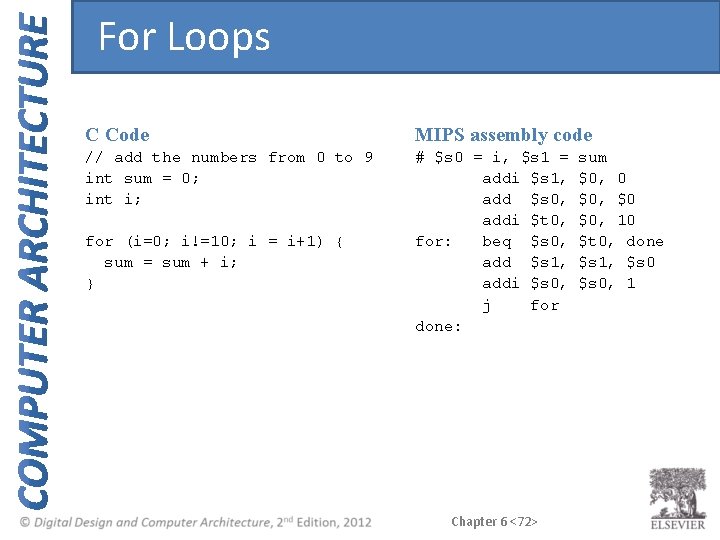

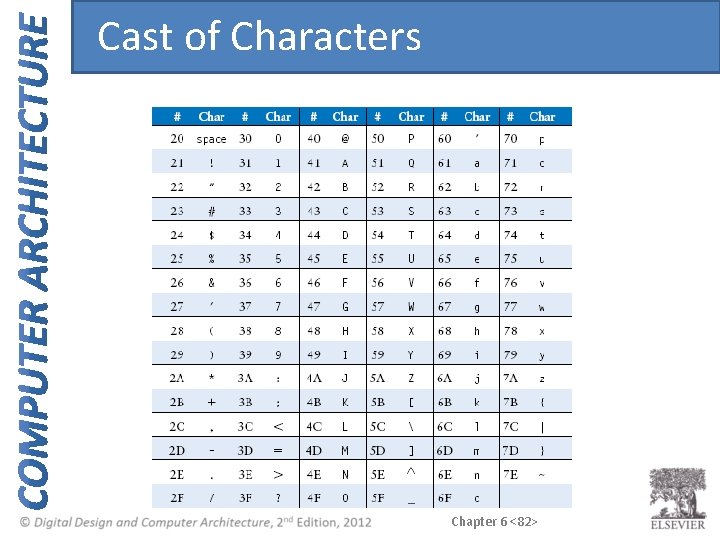

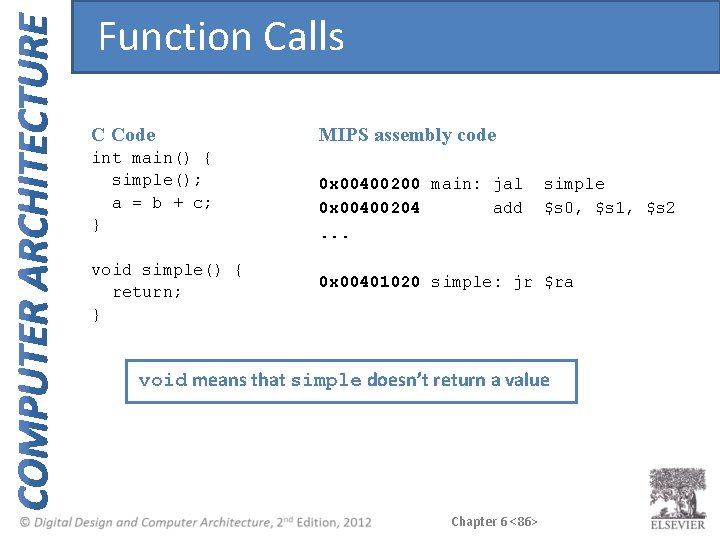

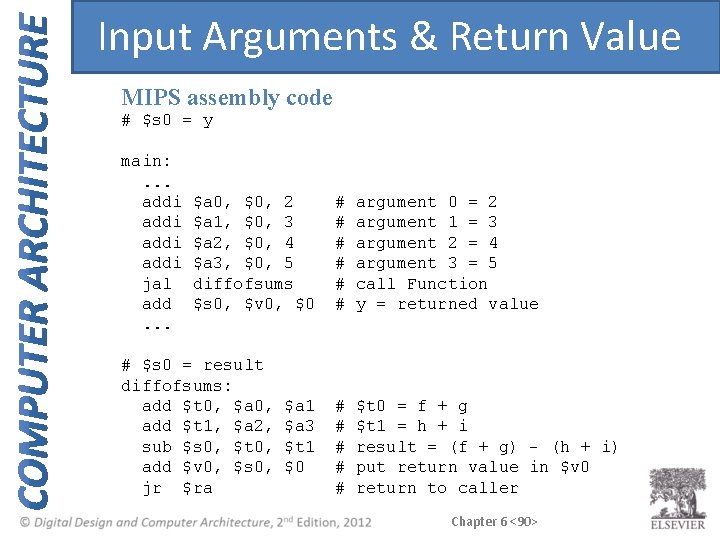

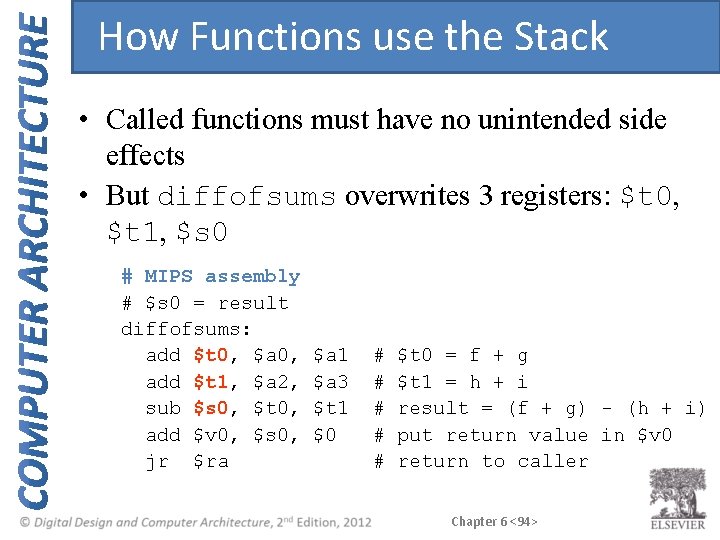

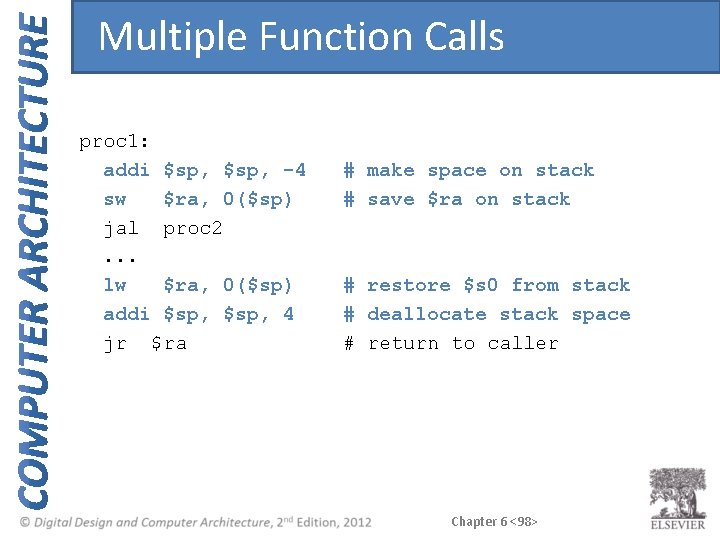

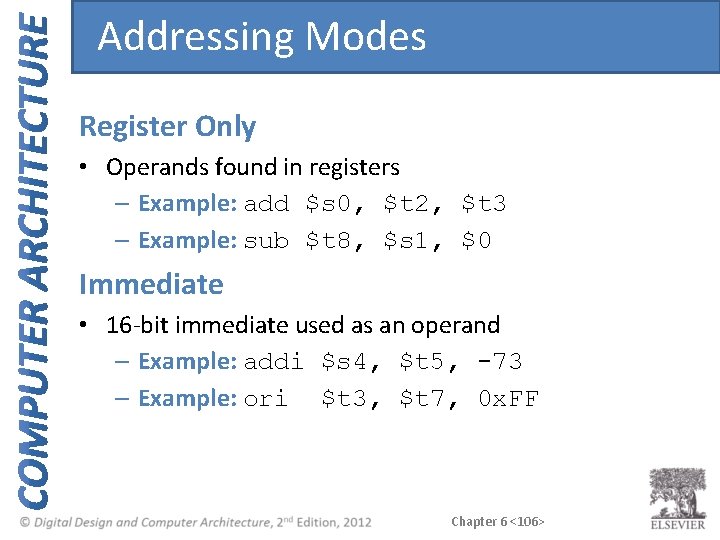

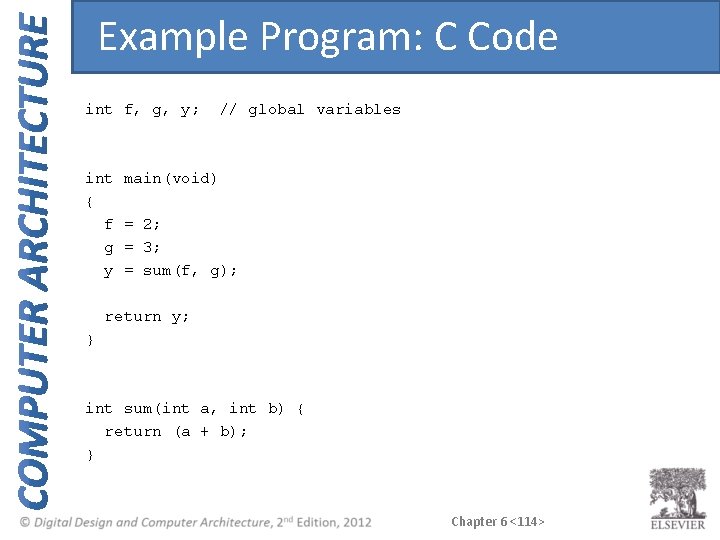

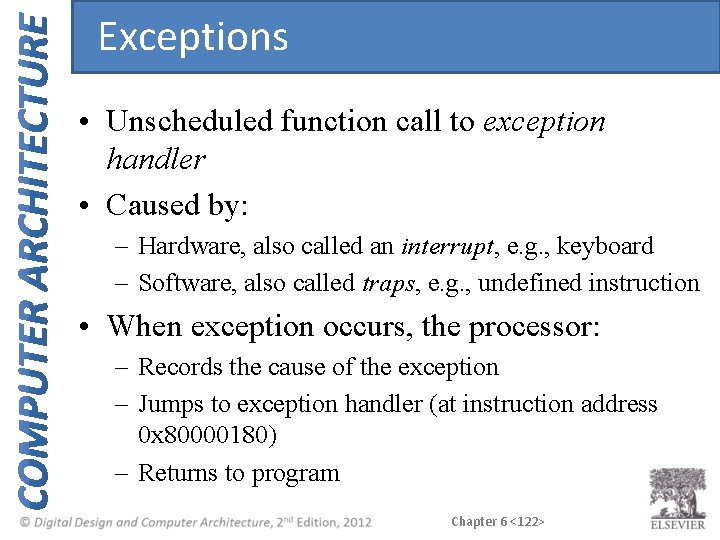

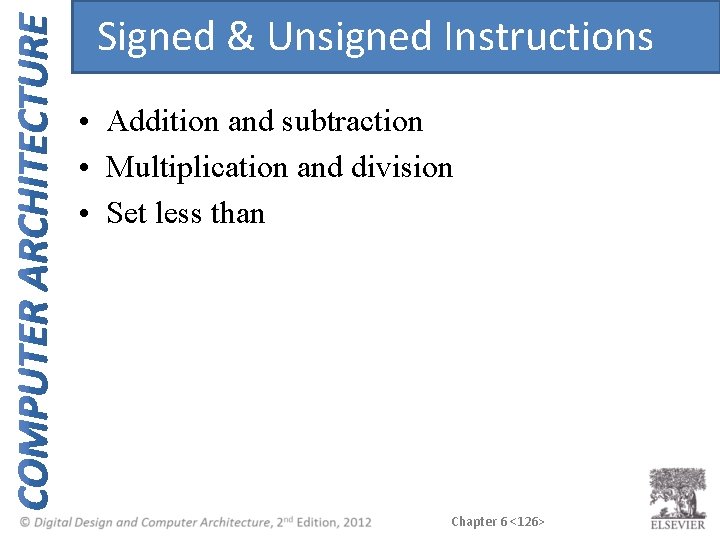

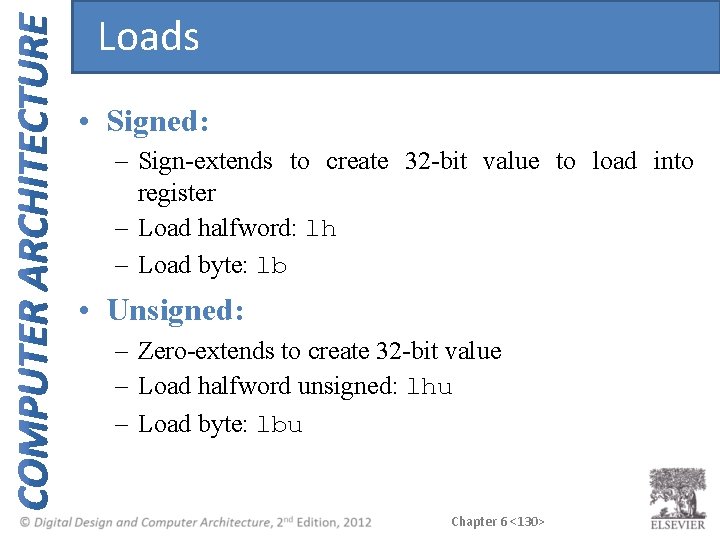

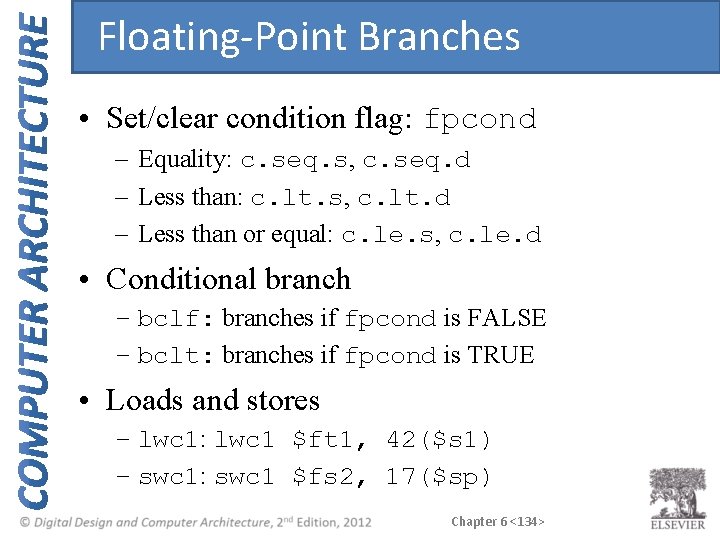

Arrays using For Loops // C Code int array[1000]; int i; for (i=0; i < 1000; i = i + 1) array[i] = array[i] * 8; # MIPS assembly code # $s 0 = array base address, $s 1 = i Chapter 6 <79>

Arrays Using For Loops # MIPS assembly code # $s 0 = array base address, # initialization code lui $s 0, 0 x 23 B 8 # ori $s 0, 0 x. F 000 # addi $s 1, $0, 0 # addi $t 2, $0, 1000 # loop: slt beq sll add lw sll sw addi j done: $t 0, $t 1, $s 1, loop $s 1, $t 2 $0, done $s 1, 2 $t 0, $s 0 0($t 0) $t 1, 3 0($t 0) $s 1, 1 # # # # # $s 1 = i $s 0 i = $t 2 = 0 x 23 B 80000 = 0 x 23 B 8 F 000 0 = 1000 i < 1000? if not then done $t 0 = i * 4 (byte offset) address of array[i] $t 1 = array[i] * 8 array[i] = array[i] * 8 i = i + 1 repeat Chapter 6 <80>

ASCII Code • American Standard Code for Information Interchange • Each text character has unique byte value – For example, S = 0 x 53, a = 0 x 61, A = 0 x 41 – Lower-case and upper-case differ by 0 x 20 (32) Chapter 6 <81>

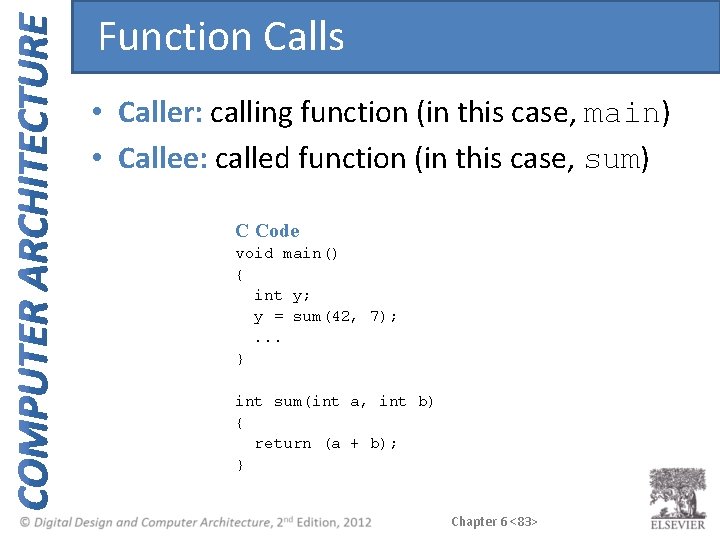

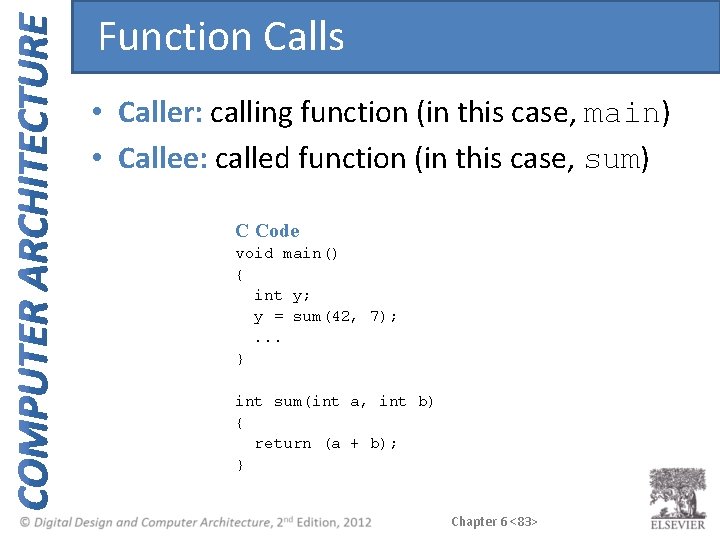

Cast of Characters Chapter 6 <82>

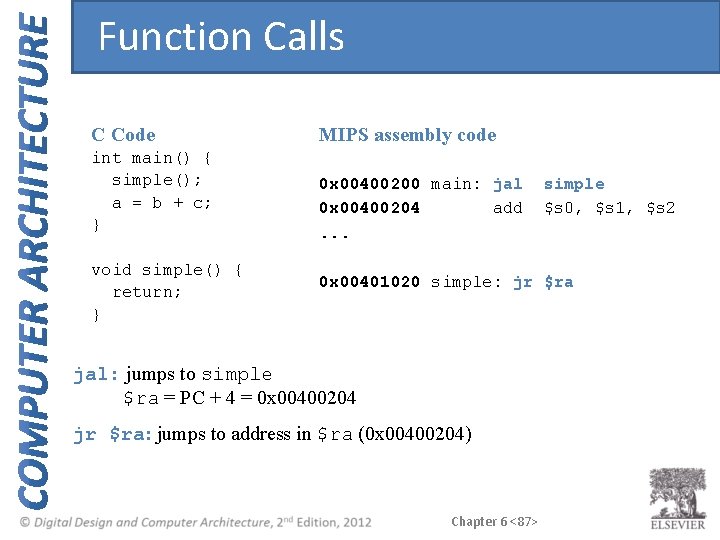

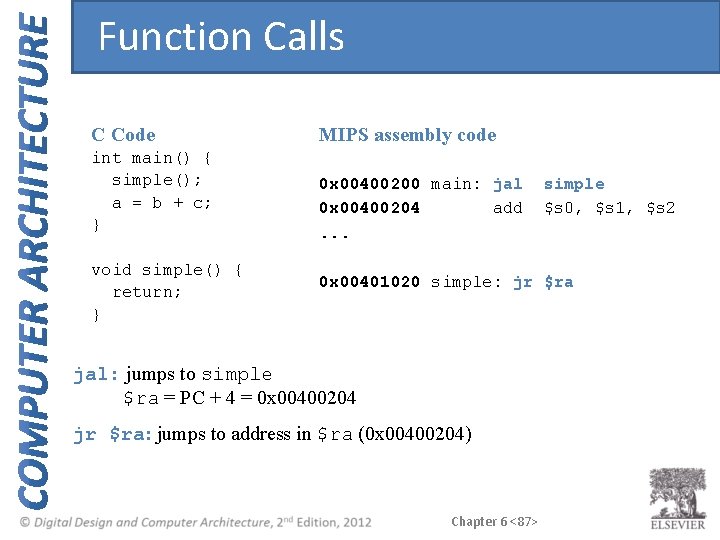

Function Calls • Caller: calling function (in this case, main) • Callee: called function (in this case, sum) C Code void main() { int y; y = sum(42, 7); . . . } int sum(int a, int b) { return (a + b); } Chapter 6 <83>

Function Conventions • Caller: – passes arguments to callee – jumps to callee • Callee: – performs the function – returns result to caller – returns to point of call – must not overwrite registers or memory needed by caller Chapter 6 <84>

MIPS Function Conventions • • Call Function: jump and link (jal) Return from function: jump register (jr) Arguments: $a 0 - $a 3 Return value: $v 0 Chapter 6 <85>

Function Calls C Code MIPS assembly code int main() { simple(); a = b + c; } 0 x 00400200 main: jal 0 x 00400204 add. . . void simple() { return; } simple $s 0, $s 1, $s 2 0 x 00401020 simple: jr $ra void means that simple doesn’t return a value Chapter 6 <86>

Function Calls C Code MIPS assembly code int main() { simple(); a = b + c; } 0 x 00400200 main: jal 0 x 00400204 add. . . void simple() { return; } simple $s 0, $s 1, $s 2 0 x 00401020 simple: jr $ra jal: jumps to simple $ra = PC + 4 = 0 x 00400204 jr $ra: jumps to address in $ra (0 x 00400204) Chapter 6 <87>

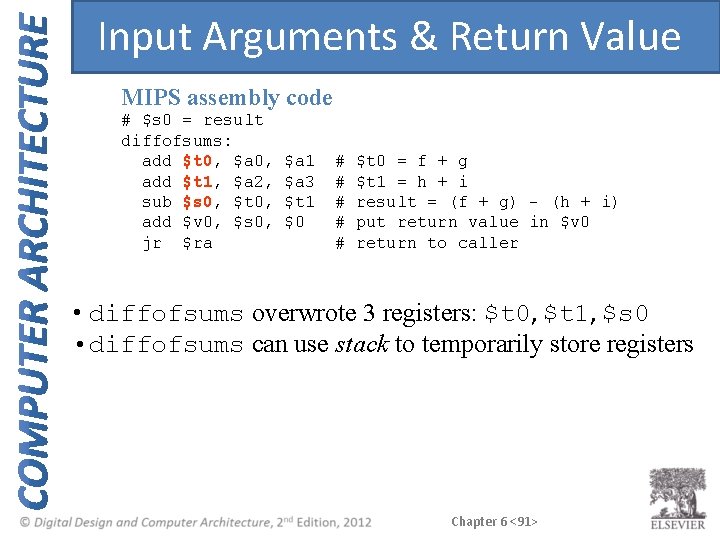

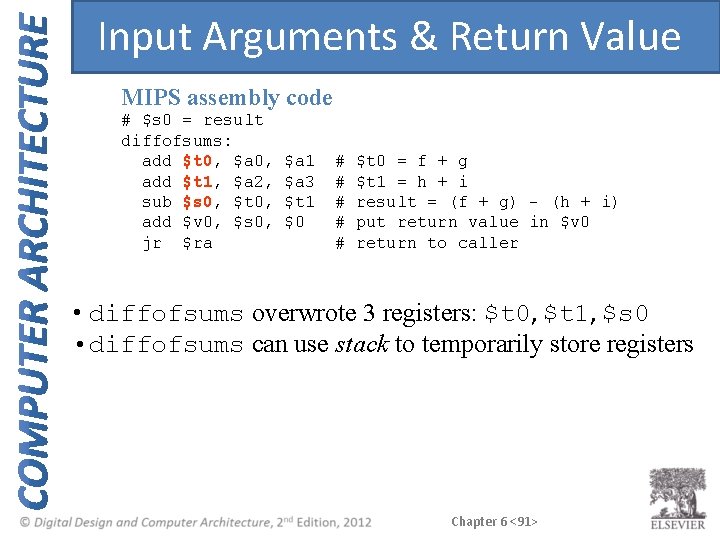

Input Arguments & Return Value MIPS conventions: • Argument values: $a 0 - $a 3 • Return value: $v 0 Chapter 6 <88>

Input Arguments & Return Value C Code int main() { int y; . . . y = diffofsums(2, 3, 4, 5); . . . } // 4 arguments int diffofsums(int f, int g, int h, int i) { int result; result = (f + g) - (h + i); return result; // return value } Chapter 6 <89>

Input Arguments & Return Value MIPS assembly code # $s 0 = y main: . . . addi jal add. . . $a 0, $0, 2 $a 1, $0, 3 $a 2, $0, 4 $a 3, $0, 5 diffofsums $s 0, $v 0, $0 # $s 0 = result diffofsums: add $t 0, $a 0, add $t 1, $a 2, sub $s 0, $t 0, add $v 0, $s 0, jr $ra $a 1 $a 3 $t 1 $0 # # # argument 0 = 2 argument 1 = 3 argument 2 = 4 argument 3 = 5 call Function y = returned value # # # $t 0 = f + g $t 1 = h + i result = (f + g) - (h + i) put return value in $v 0 return to caller Chapter 6 <90>

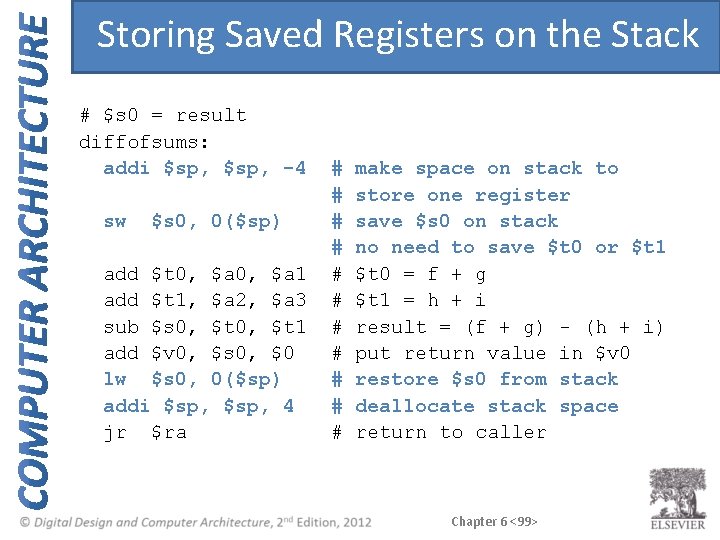

Input Arguments & Return Value MIPS assembly code # $s 0 = result diffofsums: add $t 0, $a 0, add $t 1, $a 2, sub $s 0, $t 0, add $v 0, $s 0, jr $ra $a 1 $a 3 $t 1 $0 # # # $t 0 = f + g $t 1 = h + i result = (f + g) - (h + i) put return value in $v 0 return to caller • diffofsums overwrote 3 registers: $t 0, $t 1, $s 0 • diffofsums can use stack to temporarily store registers Chapter 6 <91>

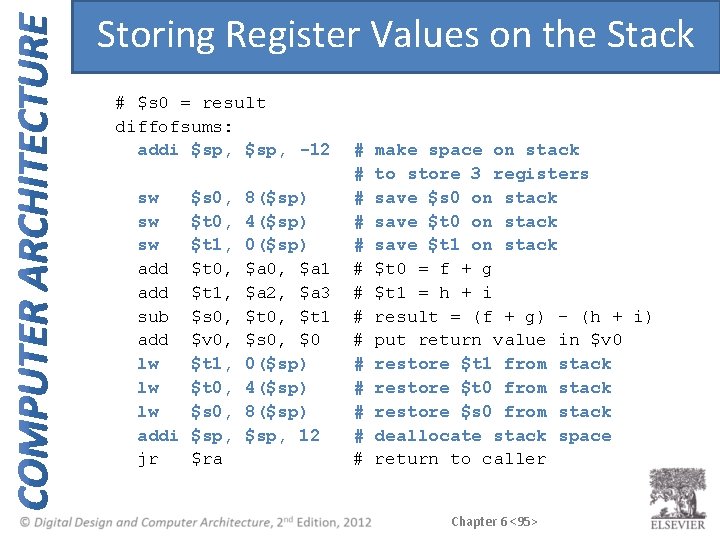

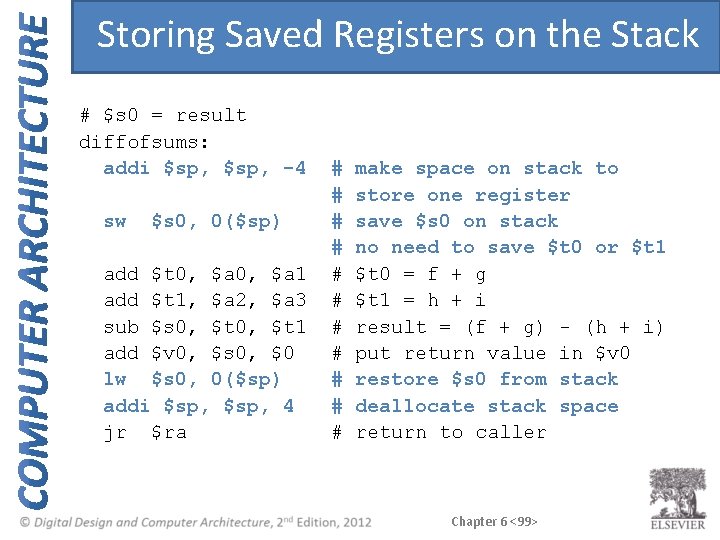

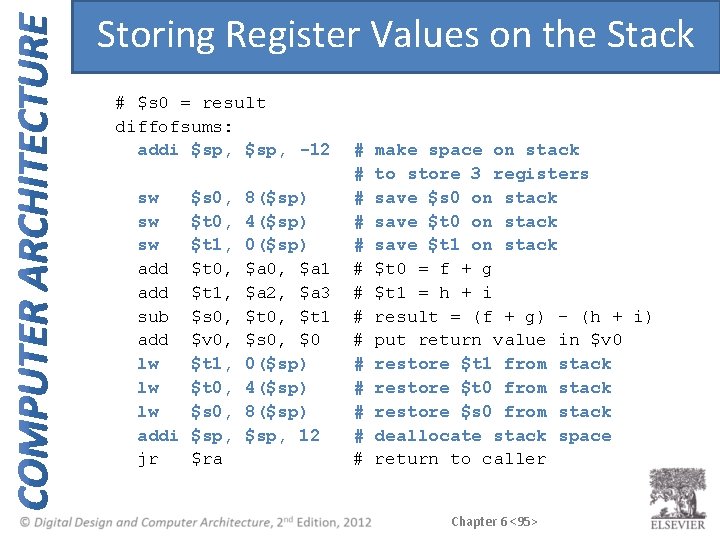

The Stack • Memory used to temporarily save variables • Like stack of dishes, last-infirst-out (LIFO) queue • Expands: uses more memory when more space needed • Contracts: uses less memory when the space is no longer needed Chapter 6 <92>

The Stack • Grows down (from higher to lower memory addresses) • Stack pointer: $sp points to top of the stack Chapter 6 <93>

How Functions use the Stack • Called functions must have no unintended side effects • But diffofsums overwrites 3 registers: $t 0, $t 1, $s 0 # MIPS assembly # $s 0 = result diffofsums: add $t 0, $a 0, add $t 1, $a 2, sub $s 0, $t 0, add $v 0, $s 0, jr $ra $a 1 $a 3 $t 1 $0 # # # $t 0 = f + g $t 1 = h + i result = (f + g) - (h + i) put return value in $v 0 return to caller Chapter 6 <94>

Storing Register Values on the Stack # $s 0 = result diffofsums: addi $sp, -12 sw sw sw add sub add lw lw lw addi jr $s 0, $t 1, $t 0, $t 1, $s 0, $v 0, $t 1, $t 0, $sp, $ra 8($sp) 4($sp) 0($sp) $a 0, $a 1 $a 2, $a 3 $t 0, $t 1 $s 0, $0 0($sp) 4($sp) 8($sp) $sp, 12 # # # # make space on stack to store 3 registers save $s 0 on stack save $t 1 on stack $t 0 = f + g $t 1 = h + i result = (f + g) - (h + i) put return value in $v 0 restore $t 1 from stack restore $t 0 from stack restore $s 0 from stack deallocate stack space return to caller Chapter 6 <95>

The stack during diffofsums Call Chapter 6 <96>

Registers Preserved Nonpreserved Callee-Saved $s 0 -$s 7 Caller-Saved $t 0 -$t 9 $ra $a 0 -$a 3 $sp $v 0 -$v 1 stack above $sp stack below $sp Chapter 6 <97>

Multiple Function Calls proc 1: addi $sp, -4 sw $ra, 0($sp) jal proc 2. . . lw $ra, 0($sp) addi $sp, 4 jr $ra # make space on stack # save $ra on stack # restore $s 0 from stack # deallocate stack space # return to caller Chapter 6 <98>

Storing Saved Registers on the Stack # $s 0 = result diffofsums: addi $sp, -4 sw $s 0, 0($sp) add $t 0, $a 1 add $t 1, $a 2, $a 3 sub $s 0, $t 1 add $v 0, $s 0, $0 lw $s 0, 0($sp) addi $sp, 4 jr $ra # # # make space on stack to store one register save $s 0 on stack no need to save $t 0 or $t 1 $t 0 = f + g $t 1 = h + i result = (f + g) - (h + i) put return value in $v 0 restore $s 0 from stack deallocate stack space return to caller Chapter 6 <99>

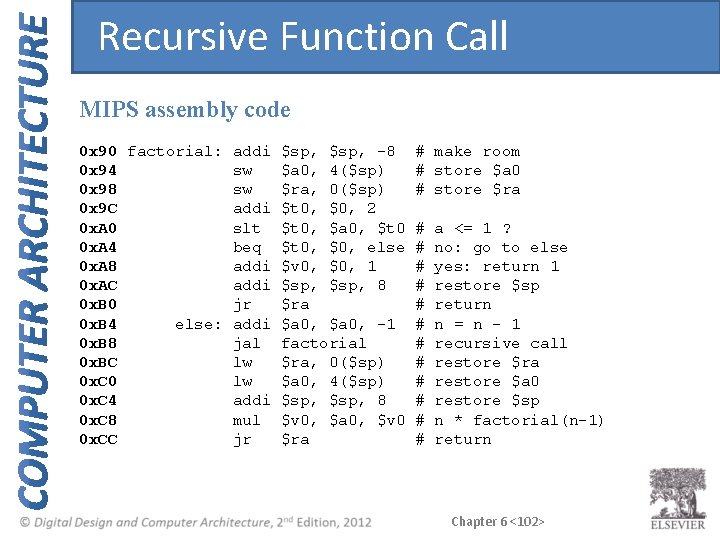

Recursive Function Call High-level code int factorial(int n) { if (n <= 1) return 1; else return (n * factorial(n-1)); } Chapter 6 <100>

Recursive Function Call MIPS assembly code Chapter 6 <101>

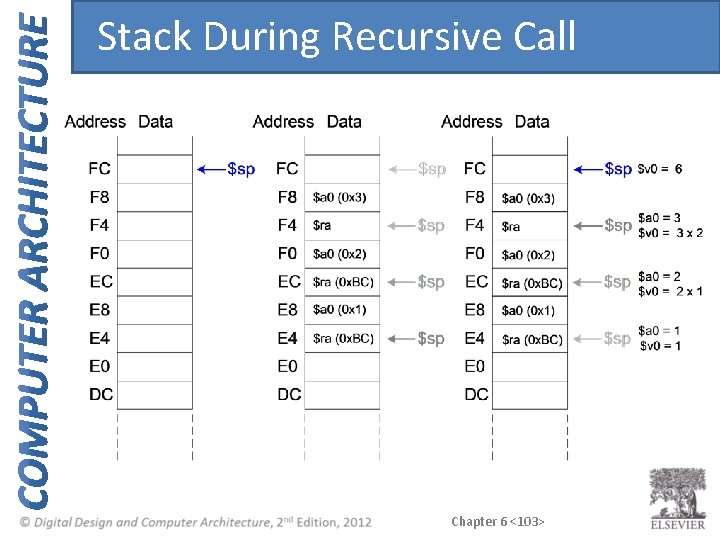

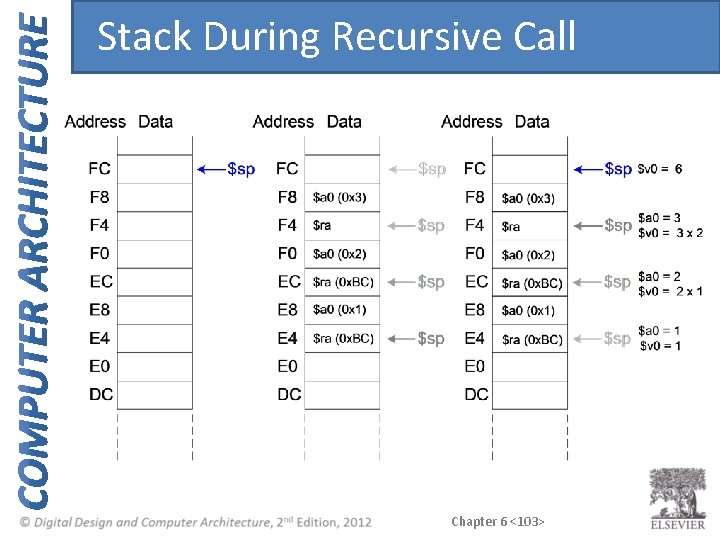

Recursive Function Call MIPS assembly code 0 x 90 factorial: addi 0 x 94 sw 0 x 98 sw 0 x 9 C addi 0 x. A 0 slt 0 x. A 4 beq 0 x. A 8 addi 0 x. AC addi 0 x. B 0 jr 0 x. B 4 else: addi 0 x. B 8 jal 0 x. BC lw 0 x. C 0 lw 0 x. C 4 addi 0 x. C 8 mul 0 x. CC jr $sp, -8 $a 0, 4($sp) $ra, 0($sp) $t 0, $0, 2 $t 0, $a 0, $t 0, $0, else $v 0, $0, 1 $sp, 8 $ra $a 0, -1 factorial $ra, 0($sp) $a 0, 4($sp) $sp, 8 $v 0, $a 0, $v 0 $ra # make room # store $a 0 # store $ra # # # a <= 1 ? no: go to else yes: return 1 restore $sp return n = n - 1 recursive call restore $ra restore $a 0 restore $sp n * factorial(n-1) return Chapter 6 <102>

Stack During Recursive Call Chapter 6 <103>

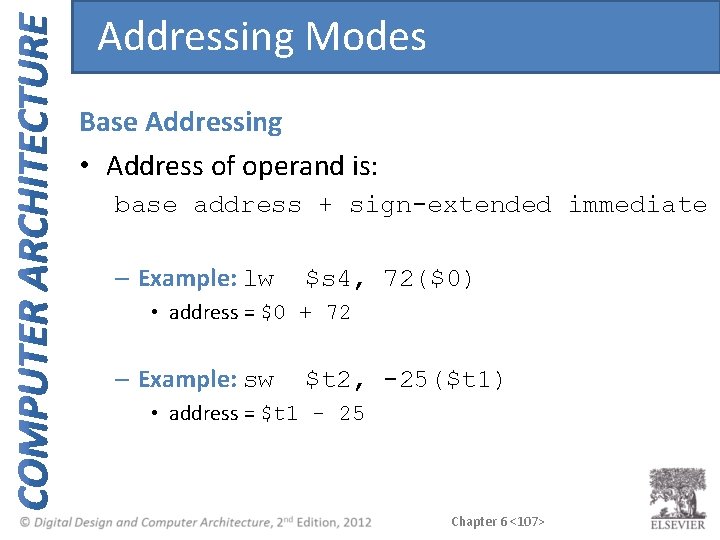

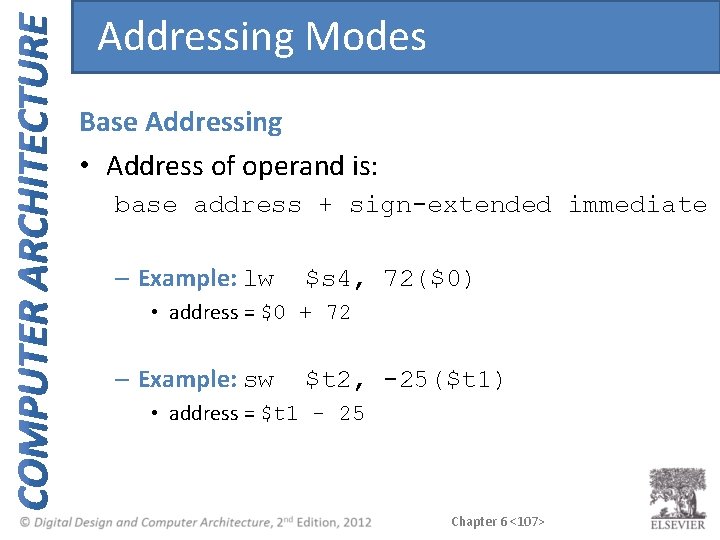

Function Call Summary • Caller – – – Put arguments in $a 0 -$a 3 Save any needed registers ($ra, maybe $t 0 -t 9) jal callee Restore registers Look for result in $v 0 • Callee – – – Save registers that might be disturbed ($s 0 -$s 7) Perform function Put result in $v 0 Restore registers jr $ra Chapter 6 <104>

Addressing Modes How do we address the operands? • • • Register Only Immediate Base Addressing PC-Relative Pseudo Direct Chapter 6 <105>

Addressing Modes Register Only • Operands found in registers – Example: add $s 0, $t 2, $t 3 – Example: sub $t 8, $s 1, $0 Immediate • 16 -bit immediate used as an operand – Example: addi $s 4, $t 5, -73 – Example: ori $t 3, $t 7, 0 x. FF Chapter 6 <106>

Addressing Modes Base Addressing • Address of operand is: base address + sign-extended immediate – Example: lw $s 4, 72($0) • address = $0 + 72 – Example: sw $t 2, -25($t 1) • address = $t 1 - 25 Chapter 6 <107>

Addressing Modes PC-Relative Addressing 0 x 10 0 x 14 0 x 18 0 x 1 C 0 x 20 0 x 24 else: beq addi jr addi jal $t 0, $0, else $v 0, $0, 1 $sp, i $ra $a 0, -1 factorial Chapter 6 <108>

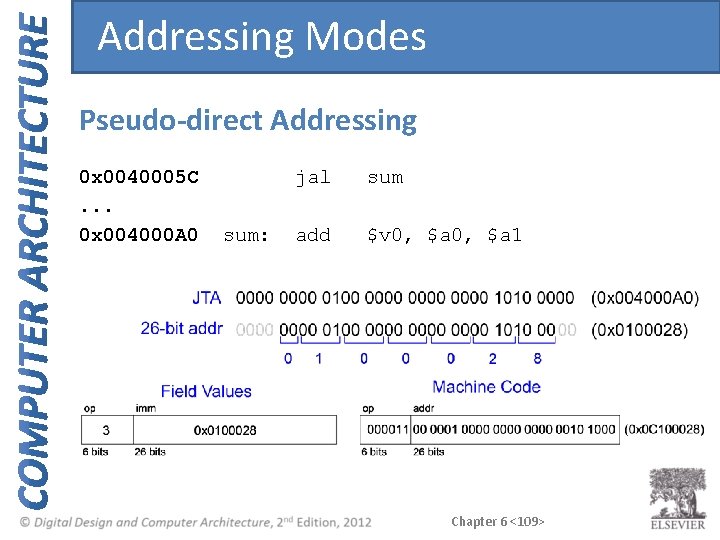

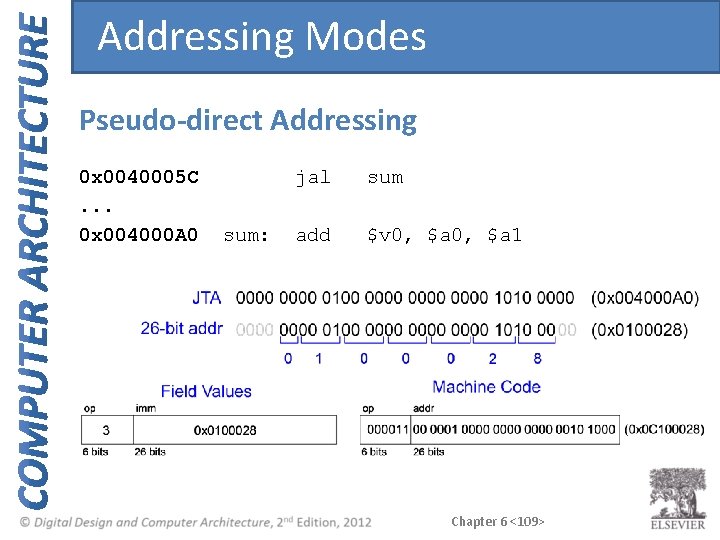

Addressing Modes Pseudo-direct Addressing 0 x 0040005 C. . . 0 x 004000 A 0 sum: jal sum add $v 0, $a 1 Chapter 6 <109>

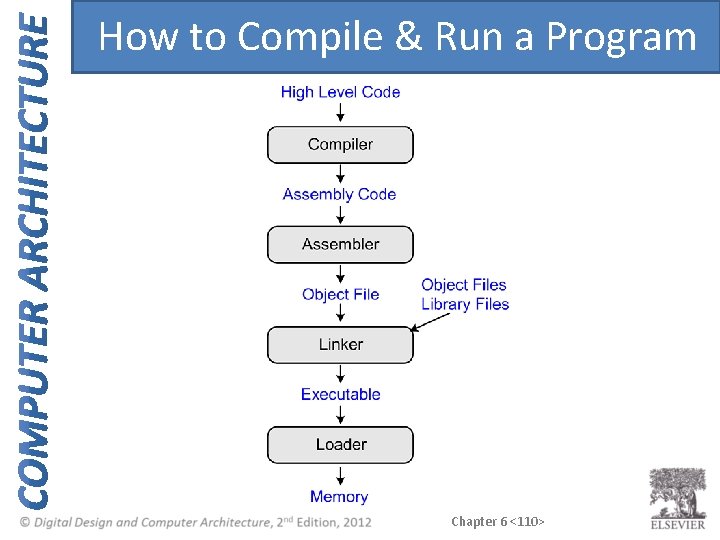

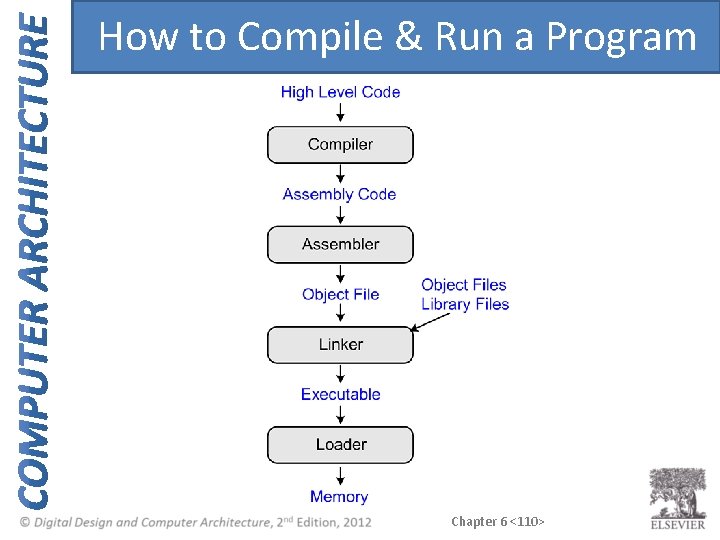

How to Compile & Run a Program Chapter 6 <110>

Grace Hopper, 1906 -1992 • Graduated from Yale University with a Ph. D. in mathematics • Developed first compiler • Helped develop the COBOL programming language • Highly awarded naval officer • Received World War II Victory Medal and National Defense Service Medal, among others Chapter 6 <111>

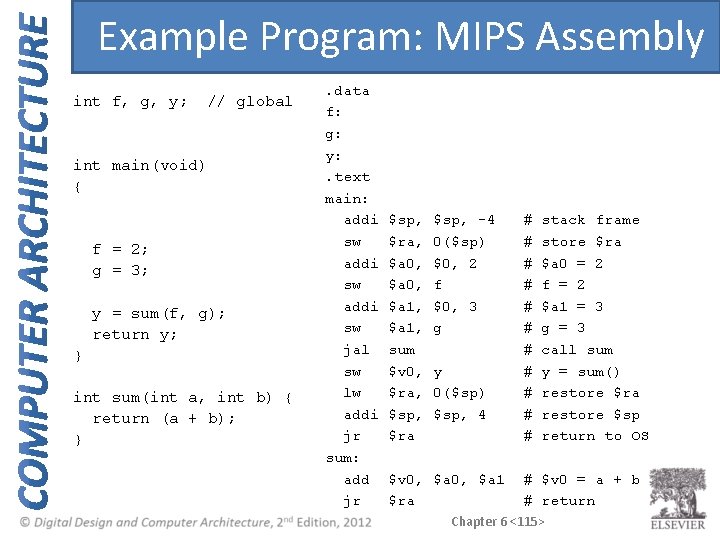

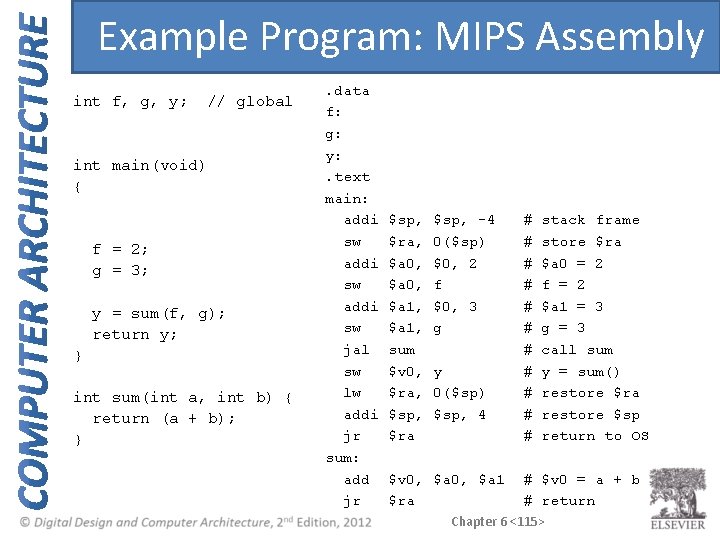

What is Stored in Memory? • Instructions (also called text) • Data – Global/static: allocated before program begins – Dynamic: allocated within program • How big is memory? – At most 232 = 4 gigabytes (4 GB) – From address 0 x 0000 to 0 x. FFFF Chapter 6 <112>

MIPS Memory Map Chapter 6 <113>

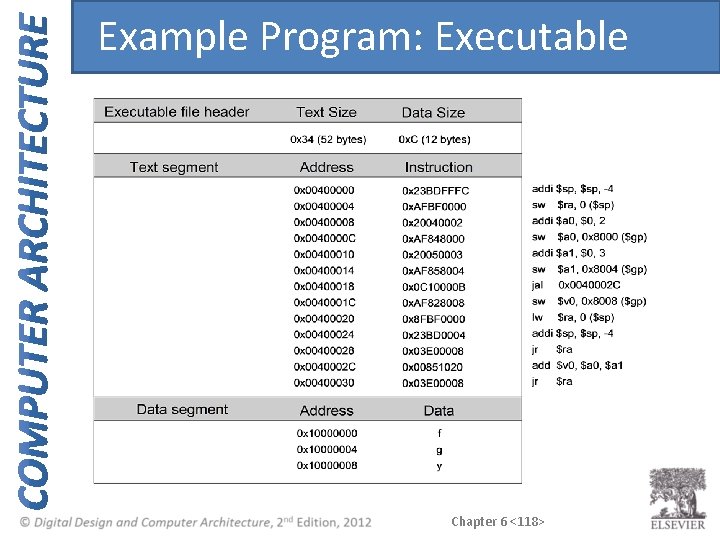

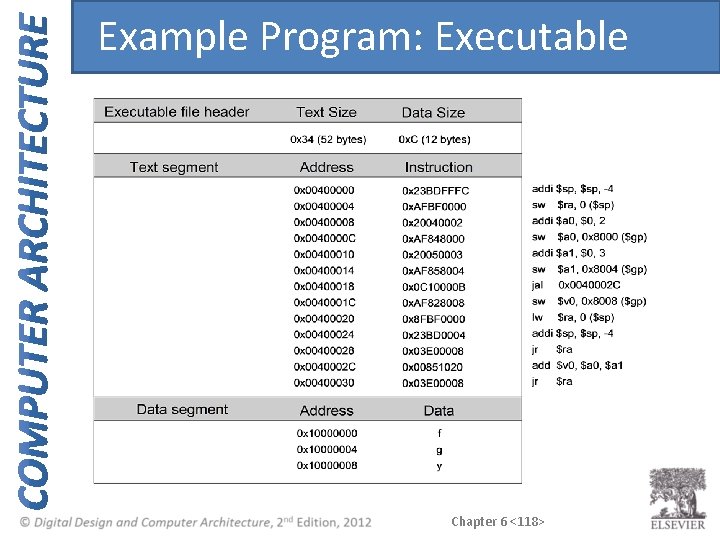

Example Program: C Code int f, g, y; int { f g y // global variables main(void) = 2; = 3; = sum(f, g); return y; } int sum(int a, int b) { return (a + b); } Chapter 6 <114>

Example Program: MIPS Assembly int f, g, y; // global int main(void) { f = 2; g = 3; y = sum(f, g); return y; } int sum(int a, int b) { return (a + b); } . data f: g: y: . text main: addi sw jal sw lw addi jr sum: add jr $sp, $ra, $a 0, $a 1, sum $v 0, $ra, $sp, $ra $sp, -4 0($sp) $0, 2 f $0, 3 g y 0($sp) $sp, 4 $v 0, $a 1 $ra # # # stack frame store $ra $a 0 = 2 f = 2 $a 1 = 3 g = 3 call sum y = sum() restore $ra restore $sp return to OS # $v 0 = a + b # return Chapter 6 <115>

Example Program: Symbol Table Symbol Address Chapter 6 <116>

Example Program: Symbol Table Symbol Address f 0 x 10000000 g 0 x 10000004 y 0 x 10000008 main 0 x 00400000 sum 0 x 0040002 C Chapter 6 <117>

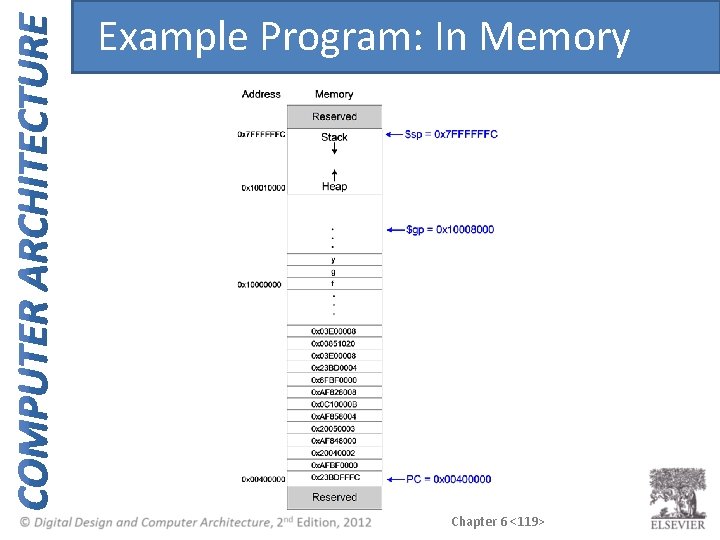

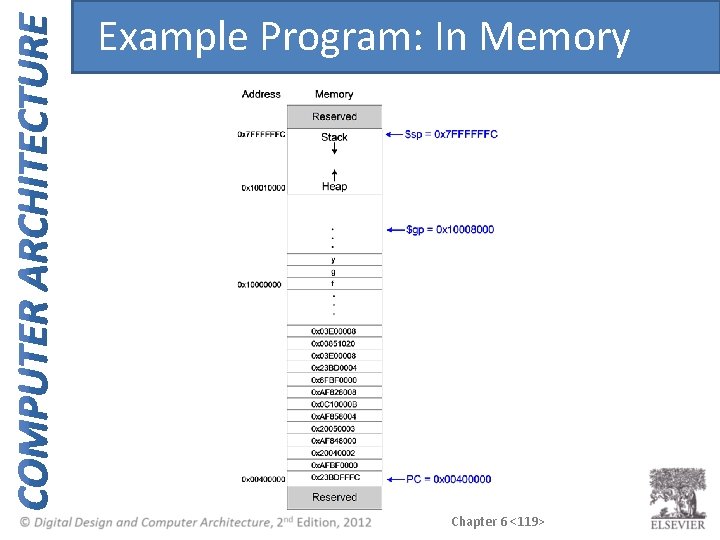

Example Program: Executable Chapter 6 <118>

Example Program: In Memory Chapter 6 <119>

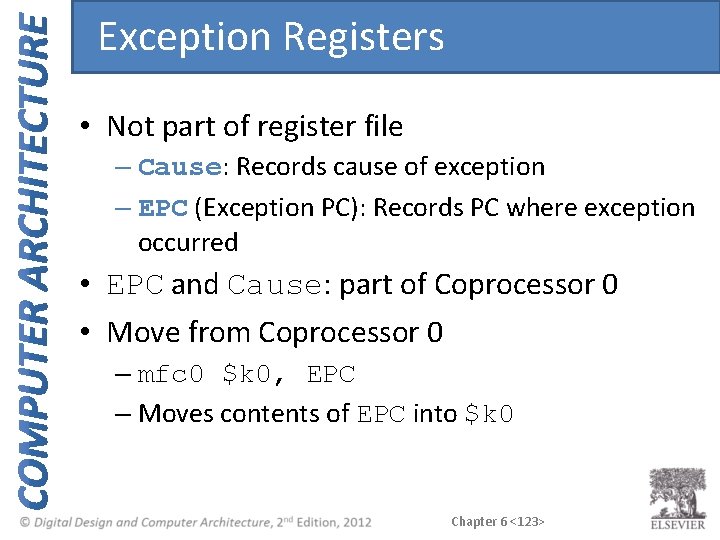

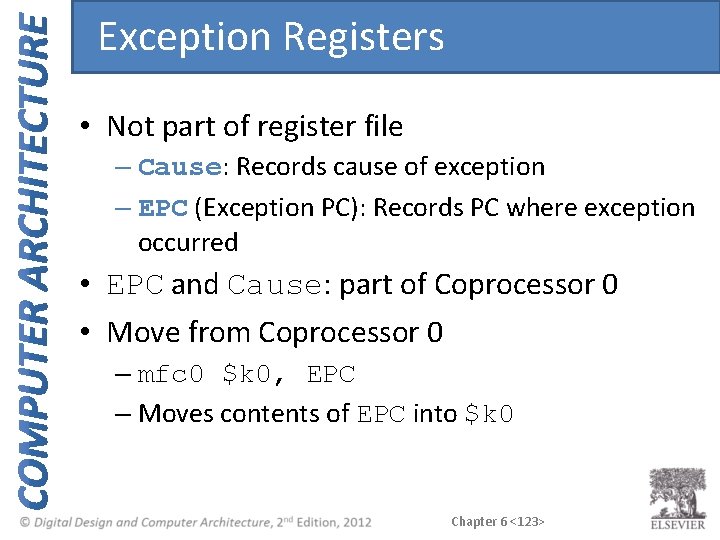

Odds & Ends • • Pseudoinstructions Exceptions Signed and unsigned instructions Floating-point instructions Chapter 6 <120>

Pseudoinstructions Pseudoinstruction MIPS Instructions li $s 0, 0 x 1234 AA 77 lui $s 0, 0 x 1234 ori $s 0, 0 x. AA 77 clear $t 0 add $t 0, $0 move $s 1, $s 2 add $s 2, $s 1, $0 nop sll $0, 0 Chapter 6 <121>

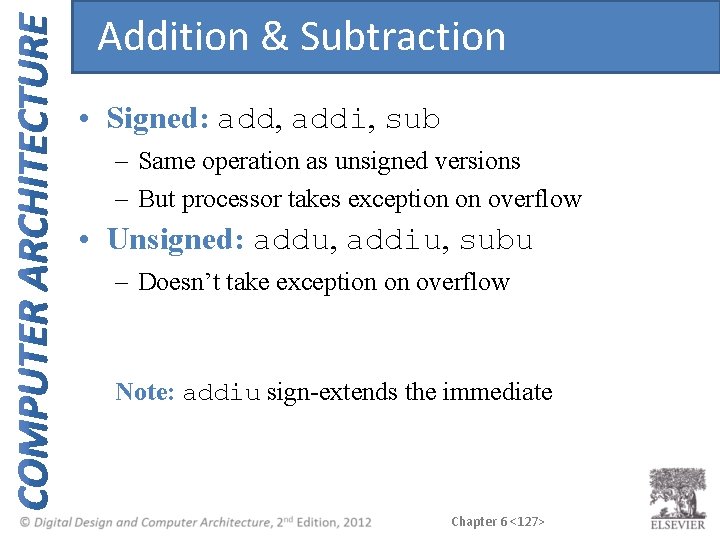

Exceptions • Unscheduled function call to exception handler • Caused by: – Hardware, also called an interrupt, e. g. , keyboard – Software, also called traps, e. g. , undefined instruction • When exception occurs, the processor: – Records the cause of the exception – Jumps to exception handler (at instruction address 0 x 80000180) – Returns to program Chapter 6 <122>

Exception Registers • Not part of register file – Cause: Records cause of exception – EPC (Exception PC): Records PC where exception occurred • EPC and Cause: part of Coprocessor 0 • Move from Coprocessor 0 – mfc 0 $k 0, EPC – Moves contents of EPC into $k 0 Chapter 6 <123>

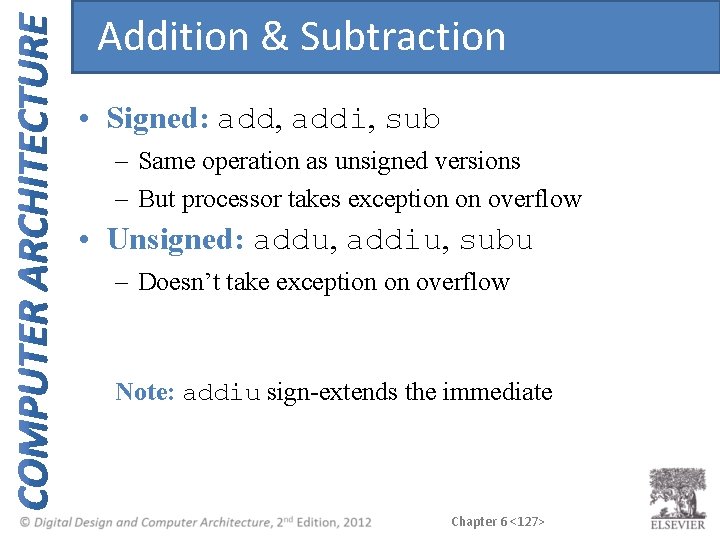

Exception Causes Exception Cause Hardware Interrupt 0 x 0000 System Call 0 x 00000020 Breakpoint / Divide by 0 0 x 00000024 Undefined Instruction 0 x 00000028 Arithmetic Overflow 0 x 00000030 Chapter 6 <124>

Exception Flow • Processor saves cause and exception PC in Cause and EPC • Processor jumps to exception handler (0 x 80000180) • Exception handler: – Saves registers on stack – Reads Cause register mfc 0 $k 0, Cause – Handles exception – Restores registers – Returns to program mfc 0 $k 0, EPC jr $k 0 Chapter 6 <125>

Signed & Unsigned Instructions • Addition and subtraction • Multiplication and division • Set less than Chapter 6 <126>

Addition & Subtraction • Signed: add, addi, sub – Same operation as unsigned versions – But processor takes exception on overflow • Unsigned: addu, addiu, subu – Doesn’t take exception on overflow Note: addiu sign-extends the immediate Chapter 6 <127>

Multiplication & Division • Signed: mult, div • Unsigned: multu, divu Chapter 6 <128>

Set Less Than • Signed: slt, slti • Unsigned: sltu, sltiu Note: sltiu sign-extends comparing it to the register the immediate Chapter 6 <129> before

Loads • Signed: – Sign-extends to create 32 -bit value to load into register – Load halfword: lh – Load byte: lb • Unsigned: – Zero-extends to create 32 -bit value – Load halfword unsigned: lhu – Load byte: lbu Chapter 6 <130>

Floating-Point Instructions • Floating-point coprocessor (Coprocessor 1) • 32 32 -bit floating-point registers ($f 0 -$f 31) • Double-precision values held in two floating point registers – e. g. , $f 0 and $f 1, $f 2 and $f 3, etc. – Double-precision floating point registers: $f 0, $f 2, $f 4, etc. Chapter 6 <131>

Floating-Point Instructions Name Register Number Usage $fv 0 - $fv 1 0, 2 return values $ft 0 - $ft 3 4, 6, 8, 10 temporary variables $fa 0 - $fa 1 12, 14 Function arguments $ft 4 - $ft 8 16, 18 temporary variables $fs 0 - $fs 5 20, 22, 24, 26, 28, 30 saved variables Chapter 6 <132>

F-Type Instruction Format • Opcode = 17 (0100012) • Single-precision: – cop = 16 (0100002) – add. s, sub. s, div. s, neg. s, abs. s, etc. • Double-precision: – cop = 17 (0100012) – add. d, sub. d, div. d, neg. d, abs. d, etc. • 3 register operands: – fs, ft: source operands – fd: destination operands Chapter 6 <133>

Floating-Point Branches • Set/clear condition flag: fpcond – Equality: c. seq. s, c. seq. d – Less than: c. lt. s, c. lt. d – Less than or equal: c. le. s, c. le. d • Conditional branch – bclf: branches if fpcond is FALSE – bclt: branches if fpcond is TRUE • Loads and stores – lwc 1: lwc 1 $ft 1, 42($s 1) – swc 1: swc 1 $fs 2, 17($sp) Chapter 6 <134>

Looking Ahead Microarchitecture – building MIPS processor in hardware Bring colored pencils Chapter 6 <135>