Chapter 6 Clinical Chemistry Laboratory Copyright 2016 by

Chapter 6 Clinical Chemistry Laboratory Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved.

Chapter 6 Objectives At the end of this chapter, the reader should be able to do the following: Convert between absorbance and transmittance values. Calculate the concentration of unknown samples using Beer’s law. Calculate the concentrations of unknown samples by single standard, multiple standards, and millimolar absorptivity methods. Calculate the concentration of enzyme unknown samples using the principles of kinetic analysis. Calculate the p. H of solutions using the Henderson. Hasselbalch equation. Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 2

Chapter 6 Objectives (Cont. ) Calculate bicarbonate, p. H, and p. CO 2 of unknown samples using the derivation of the Henderson. Hasselbalch equation. Interpret a patient’s acid-base status. Calculate the anion gap of unknown samples. Calculate the serum and urine osmolality concentrations. Calculate the osmol gap in patient samples. Calculate the concentration of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) cholesterol. Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 3

Spectrophotometry Used to quantify the concentration of various analytes based on the amount of light that the analyte absorbs Based on theory of Beer’s law The darker the solution, the higher the absorbance and the more concentrated the solution. Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 4

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) Beer’s law: the amount of absorbance of a solution is directly proportional to the solution’s concentration A = abc Where: Ø A = absorbance Ø a = absorptivity coefficient Ø b = pathlength Ø c = concentration Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 5

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) Absorptivity coefficient (a) Amount of light absorbed by an analyte at a specific wavelength Ø Constant for a particular analyte at a particular wavelength if certain conditions such as temperature, solvent, and p. H remain constant Ø Pathlength (b) The distance that light travels through the solution Ø If the analysis is performed correctly, it is also a constant. Ø Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 6

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) By removing the two constants in the equation, the following equation is derived: A c Ø Absorbance is directly proportional to concentration. Beer’s law is possible because of the concept of transmittance. Ø Transmittance is the ratio of the amount of transmitted light divided by the amount of incident light. Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 7

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) Where: LT = transmitted light Ø LI = incident light Ø Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 8

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) Transmittance ratios range from 0. 000 and 1. 000. Multiply by 100 to obtain % transmittance values. Ø Values range from 0. 00 to 100. 00 on a linear scale. If all light is transmitted through a solution (no light absorbed by solution): Transmittance ratio = 1. 00 Ø Percent transmittance = 100% Ø Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 9

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) If no light is transmitted through the solution (100% absorbance of the light by the solution): Transmittance ratio = 0. 000 Ø 0% transmittance Ø Transmittance and absorbance are related by the following formula: A = −log. T Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 10

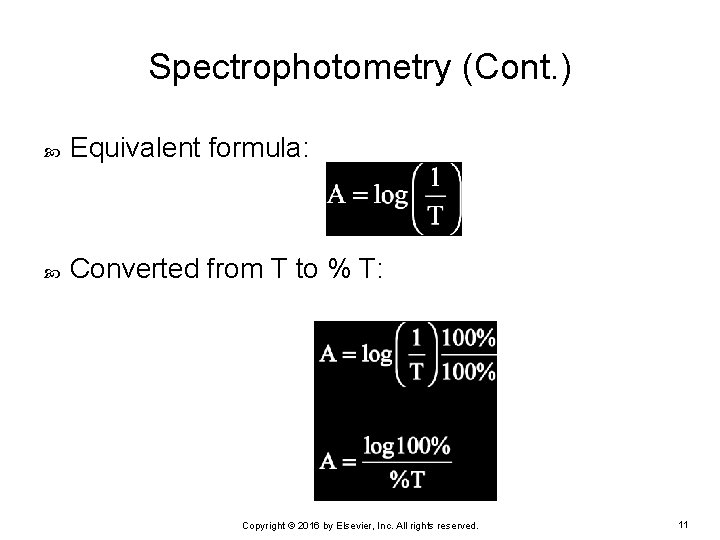

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) Equivalent formula: Converted from T to % T: Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 11

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) Solving this equation: A = log 100% – log%T OR A = 2. 00 – log%T Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 12

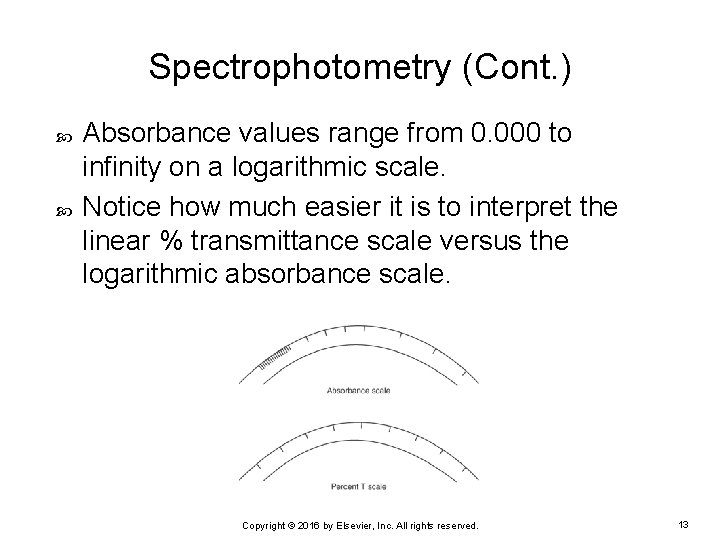

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) Absorbance values range from 0. 000 to infinity on a logarithmic scale. Notice how much easier it is to interpret the linear % transmittance scale versus the logarithmic absorbance scale. Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 13

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) EXAMPLE: A manual creatinine assay was performed using the Jaffé method in an MLT student laboratory. A 45% T reading was obtained for the cuvette containing the level 1 creatinine control and reagent. What is the absorbance value? Ø To solve this problem, use the following formula: A = 2. 00 – log%T Ø Substitute the % T value: A = 2. 00 – log 45 Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 14

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) Using a calculator or the logarithm table in Appendix 2 -A, determine the log of 45: log 45 = 1. 653 A = 2. 00 – 1. 653 A = 0. 347 The % T value of 45% = an absorbance value of 0. 347 Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 15

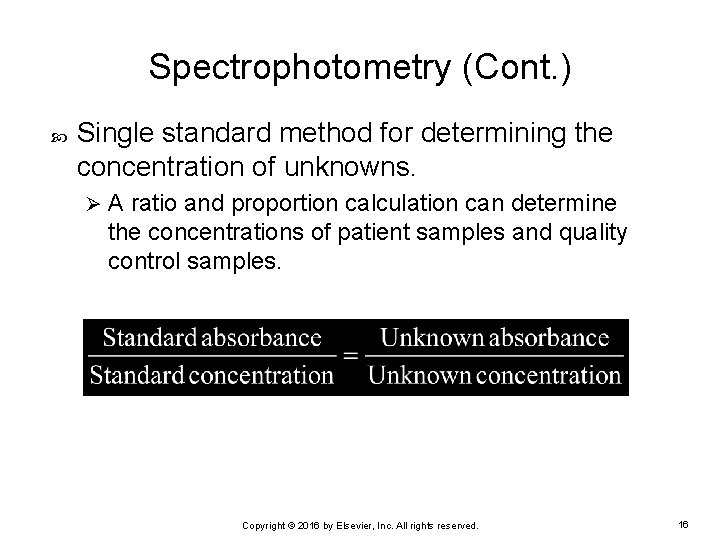

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) Single standard method for determining the concentration of unknowns. Ø A ratio and proportion calculation can determine the concentrations of patient samples and quality control samples. Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 16

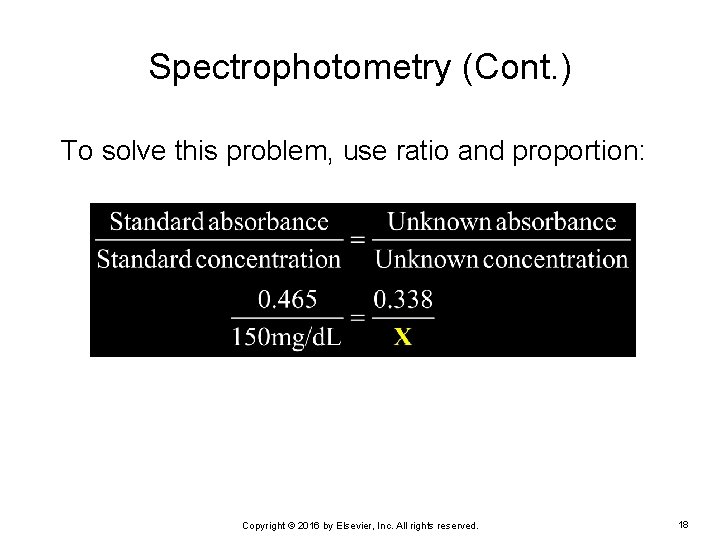

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) EXAMPLE: A manual glucose assay is performed using a single 150 -mg/d. L standard. Upon analysis, the absorbance of the standard is 0. 465. The absorbance of a patient’s sample is 0. 338. What is the concentration of the patient’s sample? Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 17

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) To solve this problem, use ratio and proportion: Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 18

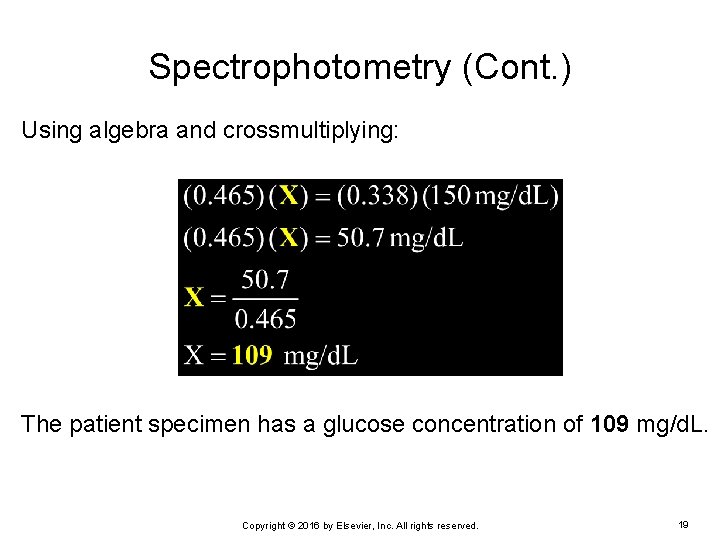

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) Using algebra and crossmultiplying: The patient specimen has a glucose concentration of 109 mg/d. L. Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 19

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) Standard curve method for determining the concentration of unknowns Most assays do not use a single standard to quantify unknowns. Ø Four to six standards of different concentrations are used. Ø Standards spread evenly across the linear range of the method. Ø More of the linear range of the assay is covered by the standards compared with the single standard method. Ø Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 20

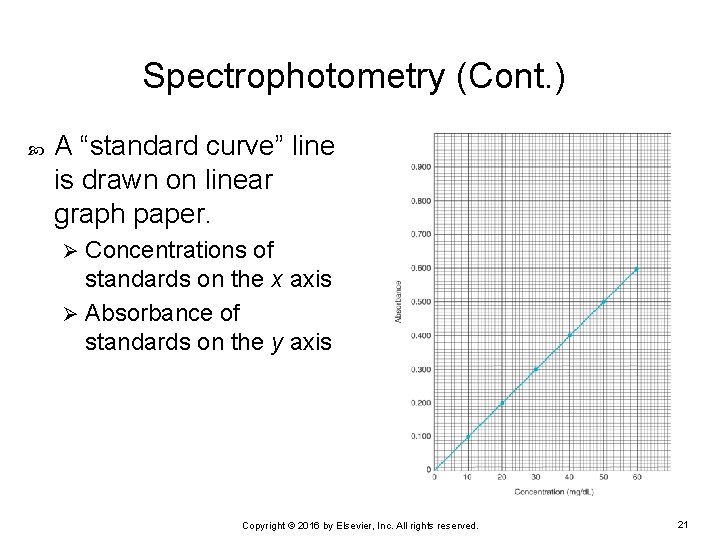

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) A “standard curve” line is drawn on linear graph paper. Concentrations of standards on the x axis Ø Absorbance of standards on the y axis Ø Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 21

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) In a manual assay that follows Beer’s law: Ø Ø Ø Standard curve of the absorbances should be a straight line. Concentrations of the standards should range between the highest and lowest linear range and two to three concentrations evenly spaced between the two outermost limits. Standard curve line should be a “best fit” line, not “point to point” or “connect the dots. ” Standard curve line should never extend beyond the highest standard. Patient samples that have absorbances higher than the highest concentration of standard must be diluted and reanalyzed so that the absorbance obtained falls within the linear range. Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 22

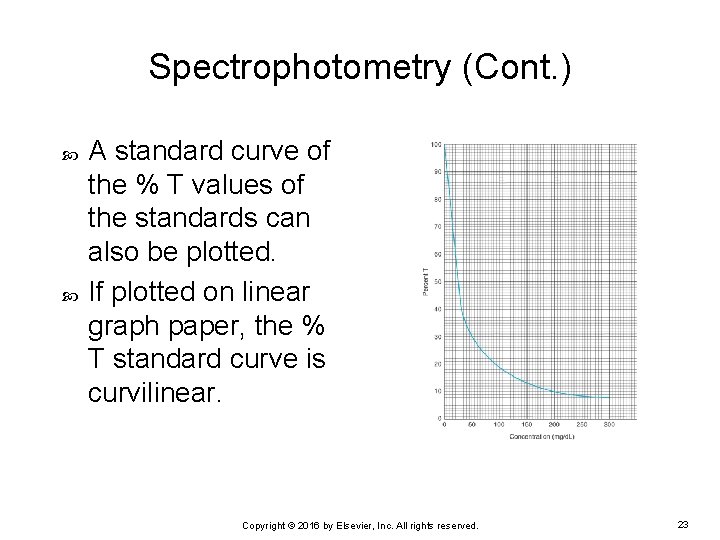

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) A standard curve of the % T values of the standards can also be plotted. If plotted on linear graph paper, the % T standard curve is curvilinear. Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 23

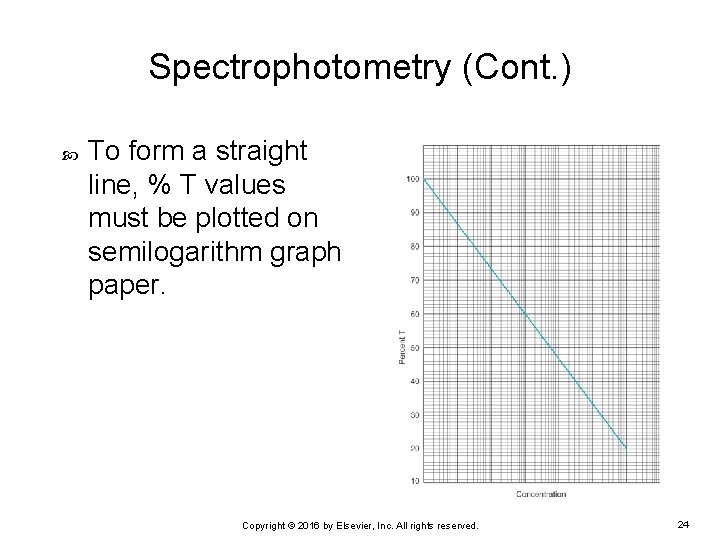

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) To form a straight line, % T values must be plotted on semilogarithm graph paper. Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 24

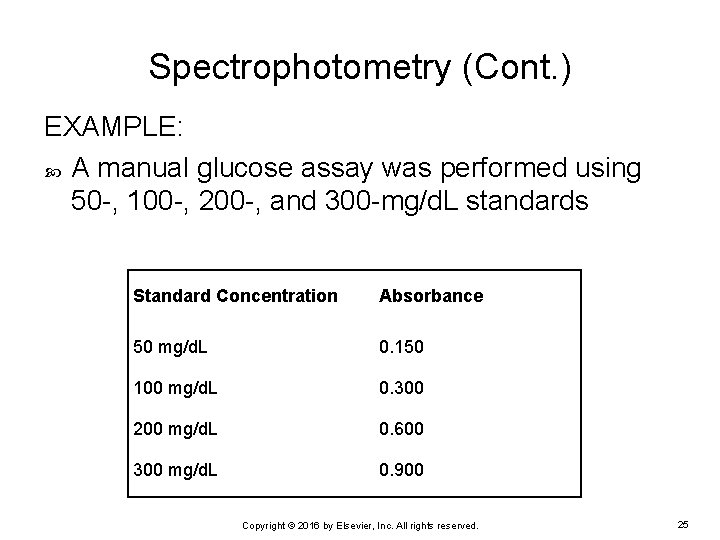

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) EXAMPLE: A manual glucose assay was performed using 50 -, 100 -, 200 -, and 300 -mg/d. L standards Standard Concentration Absorbance 50 mg/d. L 0. 150 100 mg/d. L 0. 300 200 mg/d. L 0. 600 300 mg/d. L 0. 900 Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 25

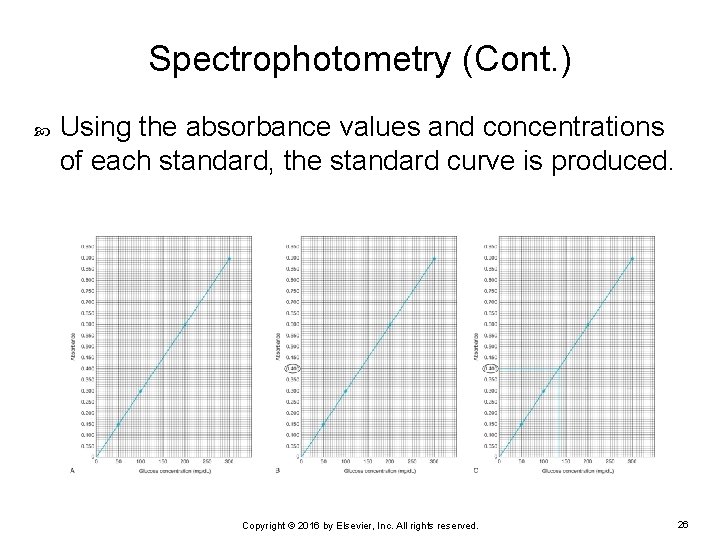

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) Using the absorbance values and concentrations of each standard, the standard curve is produced. Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 26

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) EXAMPLE: A patient sample was also analyzed at the same time that the standards were analyzed and had an absorbance value of 0. 400. What would the glucose concentration of the sample be? Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 27

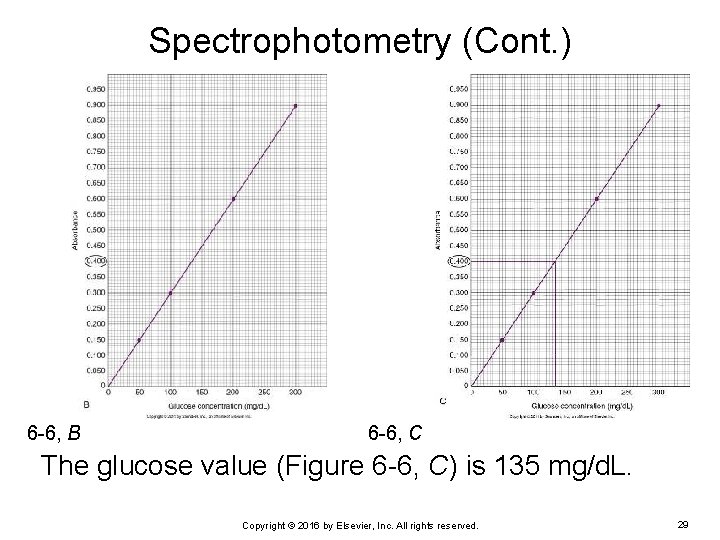

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) Use the graph of the standard curve (see Figure 6 -6, A). Find 0. 400 absorbance on the y axis scale (see Figure 6 -6, B). Use a ruler to draw a line across the graph until it intersects the standard curve line. Draw a line straight down to the x axis (see Figure 6 -6, C). The point where the vertical line intersects the x axis is the concentration of the patient sample with an absorbance of 0. 400. Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 28

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) 6 -6, B 6 -6, C The glucose value (Figure 6 -6, C) is 135 mg/d. L. Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 29

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) Preparing working standards for standard curves used for manual methods Obtained by buying them directly from a vendor Ø Also obtained by performing dilutions from one concentration of standard to prepare a series of working standards Ø Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 30

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) EXAMPLE: Standard curve needed for a total protein assay Stock standard = concentration of 10 g/d. L Ø Five working standards are necessary with a total volume each of 2 m. L and concentrations of: • 8. 0 g/d. L • 6. 0 g/d. L • 4. 0 g/d. L • 2. 0 g/d. L Ø Deionized water is used as the diluent. Ø What is the next step? Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 31

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) C 1 V 1 = C 2 V 2 is used to solve this problem Where: C 1 = original concentration (stock concentration of 10 g/d. L) Ø V 1 = unknown volume needed Ø C 2 = working standard concentration Ø V 2 = volume of working standard Ø Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 32

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) To determine how to prepare the 8. 0 -g/d. L working standard: Ø Substitute the data that are known into the equation: (10 g/d. L)(X volume) = (8 g/d. L)(2 m. L) 10 X = 16/10 X = 1. 6 Add 1. 6 m. L of the 10 -g/d. L stock standard to 0. 4 m. L of deionized water to make a total volume of 2. 0 m. L. The 6. 0 -, 4. 0 -, and 2. 0 -g/d. L working standards would be prepared using the same formula and preparation procedures. Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 33

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) Molar absorptivity method for determining the concentration of unknowns. Some automated methods may use this method. Ø Molar absorptivity for a compound is constant: • At a given wavelength • When conditions, such as temperature, remain constant Ø If the absorbance, pathlength, and molar absorptivity of an analyte are known, the concentration of the analyte can be determined. Ø Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 34

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) EXAMPLE: The molar absorptivity of NADH is 6. 22 × 103 M− 1 cm− 1 at 340 nm. If an assay of an analyte using NADH as an indicator was performed Using a 1 -cm light path and Ø A measured absorbance of NADH of 1. 650 Ø What would be the concentration of the NADH? Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 35

Spectrophotometry (Cont. ) Using Beer’s law that A = abc: 1. 650 = (6. 22 × 103 M− 1 cm− 1)(1 cm)(X molar) 1. 650 (6. 22 × 103 M− 1) = X molar X = 2. 65 × 10 -4 M Concentration of the compound = 2. 65 × 10 -4 M Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 36

End-Point versus Kinetic Reactions Chemical reactions may be end point or kinetic End-point assays: Measure the absorbance of the reaction at the completion of the reaction Ø Can use a single standard, a standard curve, or the molar absorptivity method to calculate the concentration of patient samples Ø May use enzymes within the reaction as part of the reagent Ø Analyses of enzymes are not performed as end-point reactions Ø Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 37

End-Point versus Kinetic Reactions (Cont. ) Kinetic reaction: Differs from an end-point assay Ø Does not go to completion Ø Absorbances are taken at certain intervals for short periods Ø Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 38

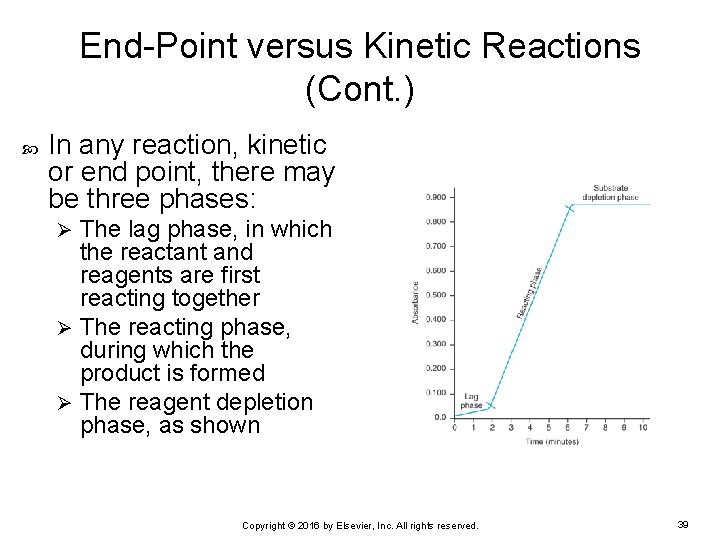

End-Point versus Kinetic Reactions (Cont. ) In any reaction, kinetic or end point, there may be three phases: The lag phase, in which the reactant and reagents are first reacting together Ø The reacting phase, during which the product is formed Ø The reagent depletion phase, as shown Ø Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 39

Enzyme Kinetics First-order reactions: reactions in which the enzyme is in excess and the substrate concentration (the concentration of the analyte to be measured) is the limiting factor The substrate concentration is low relative to the enzyme concentration. Ø The rate of the reaction is dependent on the substrate concentration. Ø Reactions tend to be used when nonenzyme analytes are measured and enzymes are used in the reaction sequence as a reagent. Ø Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 40

Enzyme Kinetics (Cont. ) Zero-order kinetics: reaction rate is directly proportional to the enzyme concentration and the rate of reaction is independent of the substrate concentration Ø When the activity of an enzyme needs to be measured, conditions of the assay are maintained to allow zeroorder kinetics to occur. Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 41

Enzyme Kinetics (Cont. ) The following reaction occurs when measuring enzyme activity: E + S E + P Where: E = enzyme Ø S = substrate Ø ES = enzyme–substrate complex Ø P = product Ø Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 42

Enzyme Kinetics (Cont. ) In a zero-order kinetic assay, the substrates are kept in excess; the rate-limiting factor is the concentration of the enzyme being analyzed. All other secondary enzymes used in the reaction are also kept in excess. Temperature, p. H, and other variables are kept constant during the reaction. Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 43

Enzyme Kinetics (Cont. ) The rate of the reaction can be calculated by the Michaelis-Menten equation: Where: v = velocity or rate of reaction (which is equal to the enzyme activity) Ø Vmax = the maximum velocity when the enzyme is saturated with substrate Ø [S] = substrate concentration Ø Km = Michaelis-Menten constant Ø Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 44

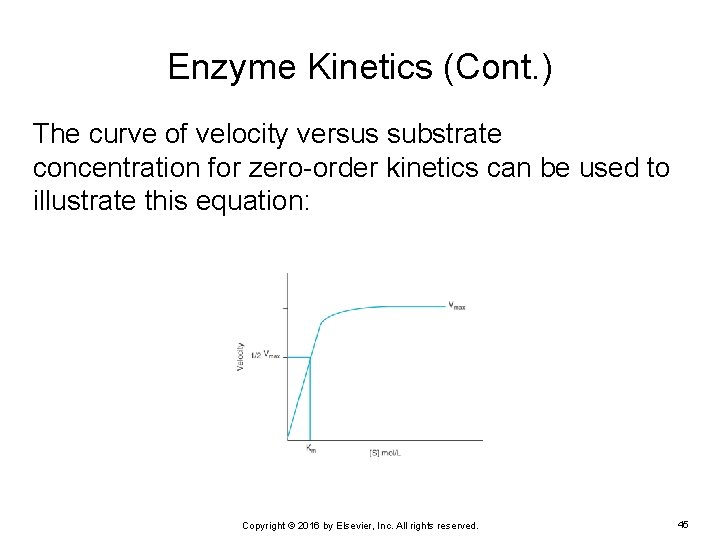

Enzyme Kinetics (Cont. ) The curve of velocity versus substrate concentration for zero-order kinetics can be used to illustrate this equation: Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 45

Enzyme Kinetics (Cont. ) The Michaelis-Menten constant (Km): the molar substrate concentration at which the velocity of the reaction is ½Vmax Specific for a particular enzyme–substrate complex under defined conditions Substrate concentration kept ≥ 10 to 20 times higher than the Km of the reaction to ensure zeroorder kinetics Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 46

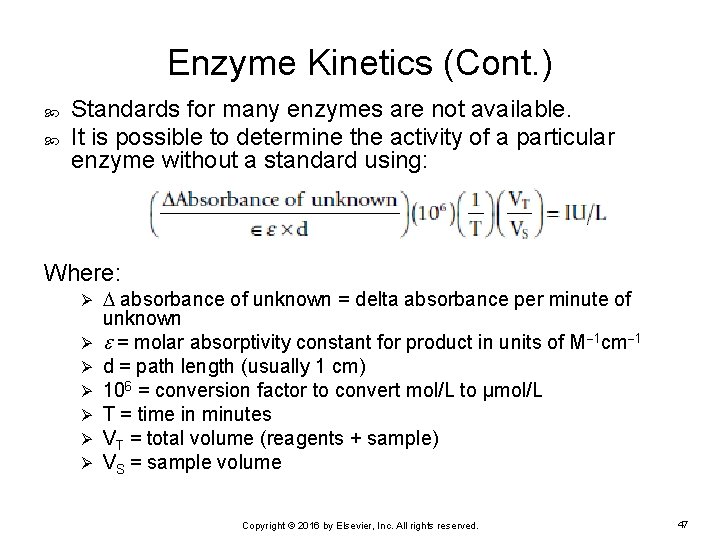

Enzyme Kinetics (Cont. ) Standards for many enzymes are not available. It is possible to determine the activity of a particular enzyme without a standard using: Where: Ø Ø Ø Ø absorbance of unknown = delta absorbance per minute of unknown = molar absorptivity constant for product in units of M 1 cm 1 d = path length (usually 1 cm) 106 = conversion factor to convert mol/L to μmol/L T = time in minutes VT = total volume (reagents + sample) VS = sample volume Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 47

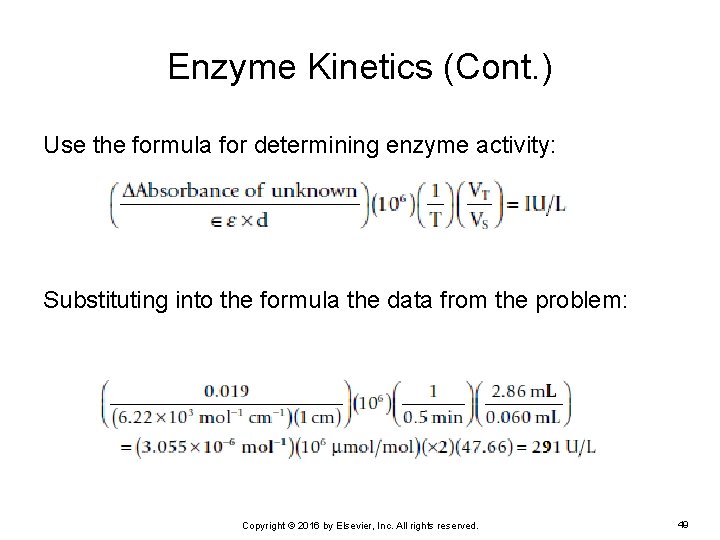

Enzyme Kinetics (Cont. ) EXAMPLE: A kinetic creatine kinase assay was performed manually using the coenzyme NADH as the reaction indicator. What is the concentration of the level 1 QC? Reagent volume was 2. 86 m. L. Ø Sample volume was 60. 0 μL. Ø Absorbance readings were taken every 30 seconds for 2 minutes. Ø Light path of the spectrophotometer was 1 cm. Ø Delta absorbance for the level 1 QC was 0. 019. Ø The molar extinction coefficient for NADH is 6. 22 × 103 M− 1 cm− 1. Ø Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 48

Enzyme Kinetics (Cont. ) Use the formula for determining enzyme activity: Substituting into the formula the data from the problem: Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 49

Buffer Calculations Buffers: solutions of weak acids or bases and their salts that resist changes in p. H Used in molecular diagnostics laboratory and the clinical laboratory The p. H of any solution is determined by its acidity Brønsted theory: Acid: substance that will donate a hydrogen ion (or a proton) Ø Base: substance that will accept the hydrogen ion or donate a hydroxyl ion Ø Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 50

Buffer Calculations (Cont. ) Conjugate acid: acid that has donated a hydrogen ion or proton Conjugate base: base that has accepted the hydrogen ion or donated a hydroxyl ion Strong acids or bases will completely dissociate when in solution Ka: dissociation constant; determines relative strength of an acid or base Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 51

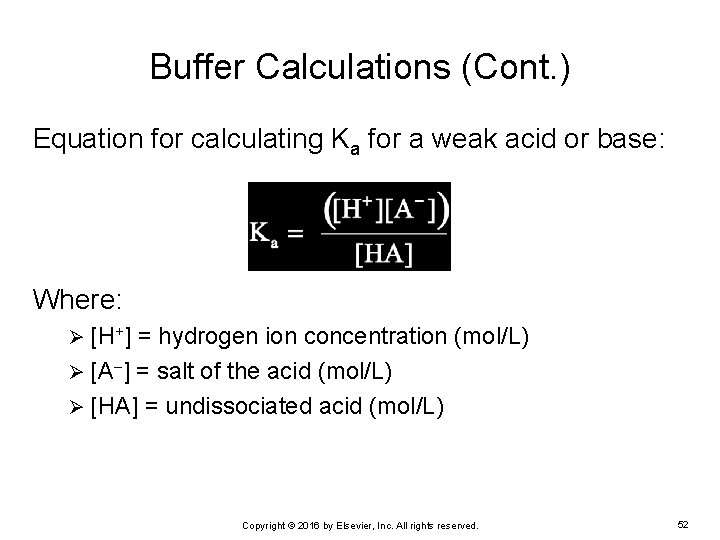

Buffer Calculations (Cont. ) Equation for calculating Ka for a weak acid or base: Where: [H+] = hydrogen ion concentration (mol/L) Ø [A ] = salt of the acid (mol/L) Ø [HA] = undissociated acid (mol/L) Ø Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 52

![Buffer Calculations (Cont. ) Substitute p. H for −log[H+] Use the rules of logarithms Buffer Calculations (Cont. ) Substitute p. H for −log[H+] Use the rules of logarithms](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/009ed1a4ca7421748087b6b3037fa4af/image-53.jpg)

Buffer Calculations (Cont. ) Substitute p. H for −log[H+] Use the rules of logarithms Ø Negative sign can be changed to a positive sign if the equation is inverted Henderson-Hasselbalch equation: Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 53

Buffer Calculations (Cont. ) If the ratio of salt to acid is 1, then p. H = p. Ka, and the buffer is at maximal buffering capacity. In an acid solution, raising the p. H above the p. Ka: Increases dissociation of the acid Ø Increases the amount of [H+] Ø Lowers the p. H Ø In a basic solution, if the p. H is below the p. Ka: More hydroxyl (OH ) ions will be released. Ø Lowers the p. H Ø Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 54

Buffer Calculations (Cont. ) EXAMPLE: A technologist prepared a phosphate buffer by adding 5. 874 g of KH 2 PO 4 and 1. 191 g of its salt K 2 HPO 4 qs to 1. 00 L of water. The p. Ka for the buffer is 7. 2. What is the p. H of the phosphate buffer? Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 55

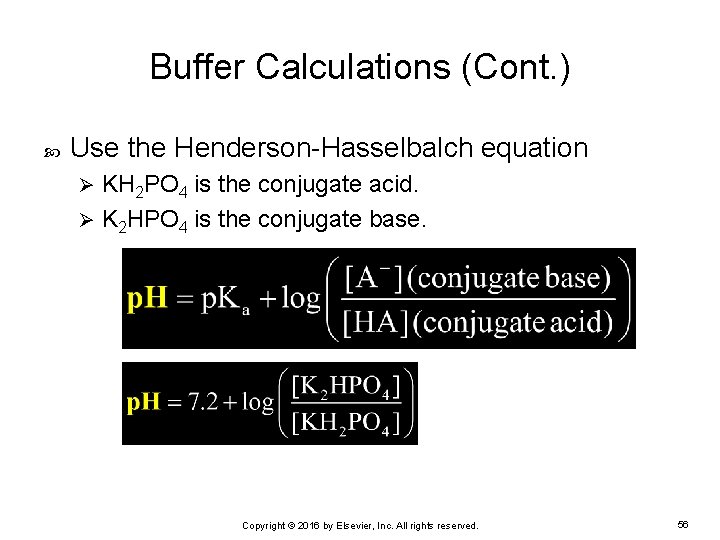

Buffer Calculations (Cont. ) Use the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation KH 2 PO 4 is the conjugate acid. Ø K 2 HPO 4 is the conjugate base. Ø Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 56

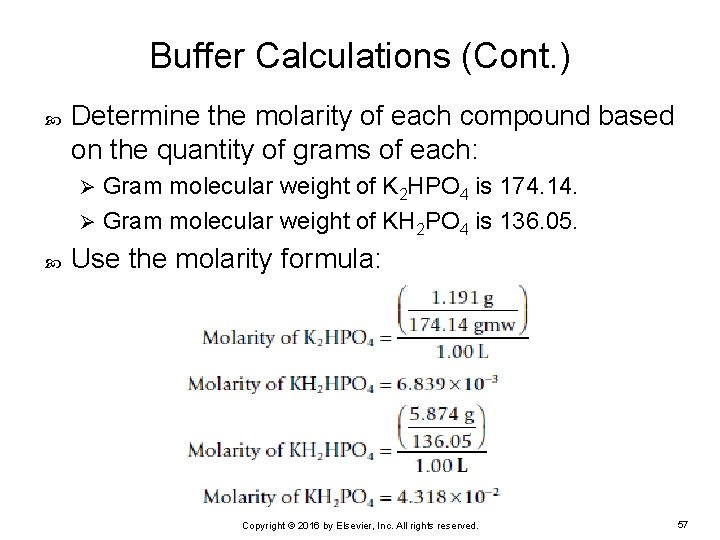

Buffer Calculations (Cont. ) Determine the molarity of each compound based on the quantity of grams of each: Gram molecular weight of K 2 HPO 4 is 174. 14. Ø Gram molecular weight of KH 2 PO 4 is 136. 05. Ø Use the molarity formula: Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 57

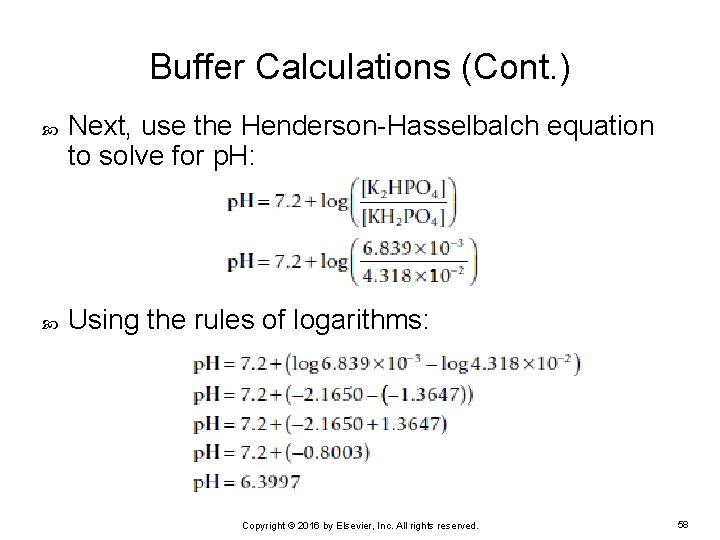

Buffer Calculations (Cont. ) Next, use the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation to solve for p. H: Using the rules of logarithms: Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 58

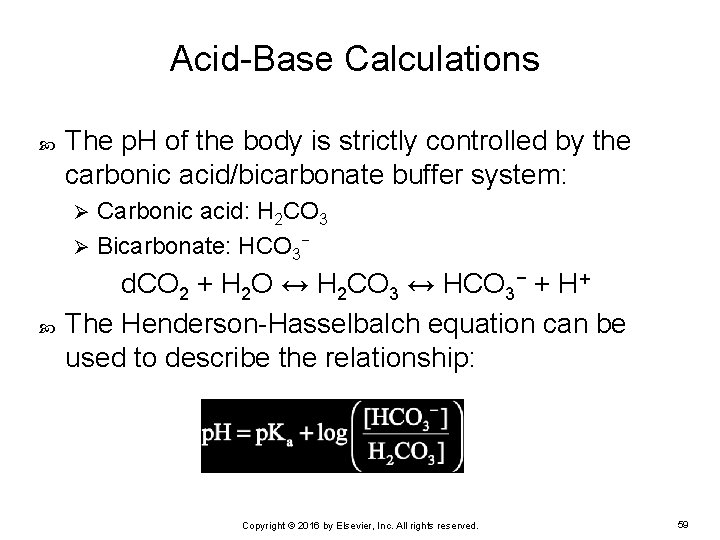

Acid-Base Calculations The p. H of the body is strictly controlled by the carbonic acid/bicarbonate buffer system: Carbonic acid: H 2 CO 3 Ø Bicarbonate: HCO 3− Ø d. CO 2 + H 2 O ↔ H 2 CO 3 ↔ HCO 3− + H+ The Henderson-Hasselbalch equation can be used to describe the relationship: Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 59

Acid-Base Calculations (Cont. ) p. Ka for the carbonic acid/bicarbonate buffer system = 6. 10 at 37° C Ratio of bicarbonate to carbonic acid = 20: 1 p. H of the blood is: Directly affected by the concentration of bicarbonate Ø Inversely affected by the concentration of carbonic acid Ø Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 60

Acid-Base Calculations (Cont. ) With blood gas instruments, the partial pressure of CO 2 can be measured (p. CO 2). Relationship between d. CO 2 and p. CO 2: d. CO 2 = p. CO 2 = solubility coefficient of p. CO 2; 0. 0306 mmol/L/mm Hg Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 61

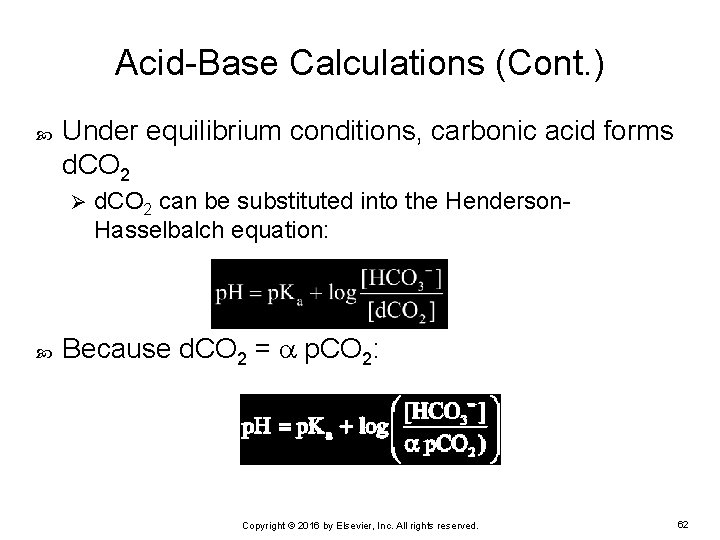

Acid-Base Calculations (Cont. ) Under equilibrium conditions, carbonic acid forms d. CO 2 Ø d. CO 2 can be substituted into the Henderson. Hasselbalch equation: Because d. CO 2 = p. CO 2: Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 62

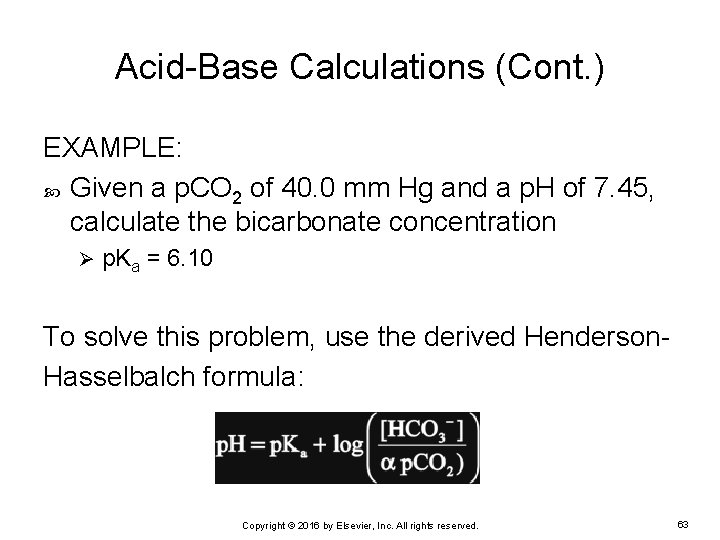

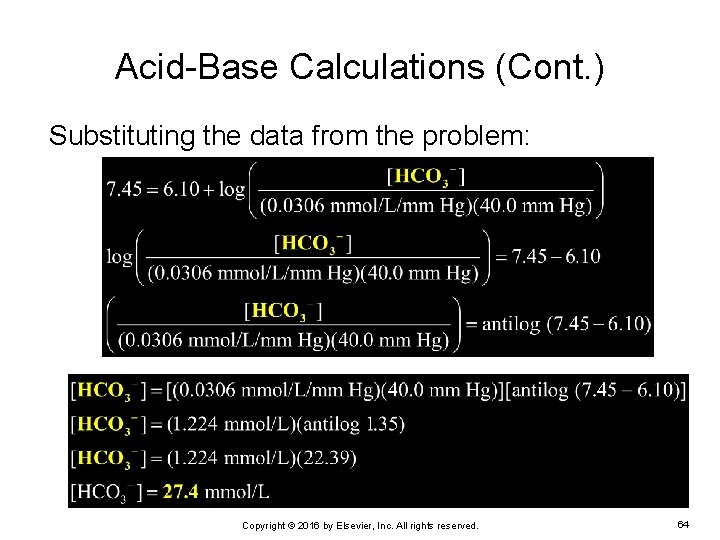

Acid-Base Calculations (Cont. ) EXAMPLE: Given a p. CO 2 of 40. 0 mm Hg and a p. H of 7. 45, calculate the bicarbonate concentration Ø p. Ka = 6. 10 To solve this problem, use the derived Henderson. Hasselbalch formula: Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 63

Acid-Base Calculations (Cont. ) Substituting the data from the problem: Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 64

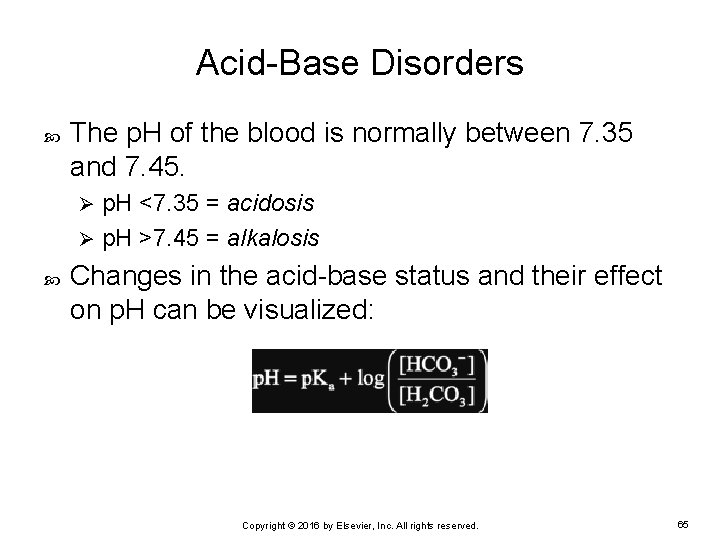

Acid-Base Disorders The p. H of the blood is normally between 7. 35 and 7. 45. p. H <7. 35 = acidosis Ø p. H >7. 45 = alkalosis Ø Changes in the acid-base status and their effect on p. H can be visualized: Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 65

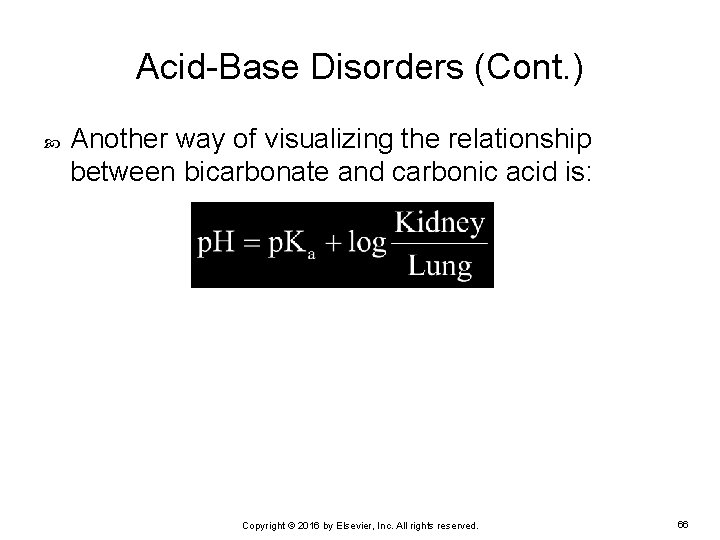

Acid-Base Disorders (Cont. ) Another way of visualizing the relationship between bicarbonate and carbonic acid is: Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 66

Acid-Base Disorders: Respiratory Acidosis Blood p. H is acidotic (<7. 35) Respiratory = major cause of the acidosis Ø If the lungs cannot adequately remove CO 2 • CO 2 will build up in the blood. • p. CO 2 level increases. • Results in lowering of p. H Reciprocal relationship between CO 2 concentration and p. H: ↑p. CO 2 = ↓p. H Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 67

Acid-Base Disorders: Respiratory Alkalosis Increased p. H caused by decreased CO 2 levels Compensation is by: Decreasing the respiration rate or Ø The kidneys retaining H+ Ø ↓p. CO 2 = ↑p. H Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 68

Acid-Base Disorders: Metabolic Acidosis Primary cause is metabolic increase in acids Most commonly seen in diabetic ketoacidosis Body compensates by: Increasing respiration rate to remove CO 2 Ø Raising the p. H Ø Kidneys respond by ↑ acid excretion and bicarbonate retention. Ø Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 69

Acid-Base Disorders: Metabolic Alkalosis Metabolic alkalosis Caused primarily by an excess of bicarbonate May result from: Insufficient excretion of bicarbonate by the kidney Ø Increased ingestion of bicarbonate such as antacids Ø Severe vomiting leading to the loss of hydrogen ions and a buildup of bicarbonate Ø Body compensates by: Lungs decrease respiration to retain CO 2. Ø Kidneys excrete more bicarbonate. Ø Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 70

Determining Acid-Base Status and Compensation Status To determine the acid-base status: Look at the p. H • Above 7. 45: The patient is alkalotic. • Below 7. 35: The patient is acidotic. Ø Look at the bicarbonate value: • Does it fit the p. H? (Bicarbonate values move in the same Ø direction as the p. H. ) • If p. H = alkalotic, is the bicarbonate elevated above normal? • If p. H = acidotic, is the bicarbonate below normal? Ø Look at the p. CO 2: • Is it what is expected, given the p. H? Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 71

Determining Acid-Base Status and Compensation Status (Cont. ) Compensation: Ø When a metabolic problem affects the p. H: • Lungs react immediately to bring the p. H back into the normal range. • Kidneys take longer to get the p. H back into the normal range. The body never overcompensates. The body has compensated when the p. H is back in the normal range. Ø The bicarbonate and p. CO 2 levels could be very abnormal, but as long as the p. H is in the normal range again, the body has compensated. Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 72

Determining Acid-Base Status and Compensation Status (Cont. ) To determine what caused the initial problem and what had to compensate: Ø Whereas the analyte that has moved in the anticipated direction of the p. H is the culprit, the analyte that has moved opposite of what you would expect to see of the p. H is the compensator. Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 73

Determining Acid-Base Status and Compensation Status (Cont. ) EXAMPLE: A patient arrives in the emergency department (ED) having an asthma attack with trouble exhaling Ø Blood gas results: • p. CO 2 = 28 mm Hg • Bicarbonate = 24 mmol/L • p. H = 7. 55 What is this patient’s acid-base status? Is the patient compensated for the acid-base status? Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 74

Determining Acid-Base Status and Compensation Status (Cont. ) p. H is 7. 55: Patient is alkalotic Ø Has not yet brought p. H into the normal range Ø p. CO 2 is abnormally low Ø Bicarbonate is normal. Ø Based on the patient’s asthma, this is uncompensated respiratory alkalosis. Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 75

Determining Acid-Base Status and Compensation Status (Cont. ) Blood gas analysis measures and calculations: p. H Ø p. O 2 Ø p. CO 2 Ø HCO 3Ø Base excess Ø % Oxygen saturation (%SO 2) %SO 2 = c. O 2 Hb c. O 2 Hb + c. HHb • c. O 2 Hb = concentration of oxyhemoglobin • c. HHb = concentration of deoxyhemoglobin Ø Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 76

Anion Gap The concentration of anions should equal the concentration of cations in the body. Anion gap measures anions or cations of the highest concentration to significantly alter the balance. Sodium is the cation found in highest concentration in the blood. Ø Chloride is the most abundant anion in the blood. Ø Bicarbonate also is an anion and is included in the anion gap. Ø Some labs include potassium in the anion gap; however, concentration of K+ is relatively low compared with the other electrolytes. Ø Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 77

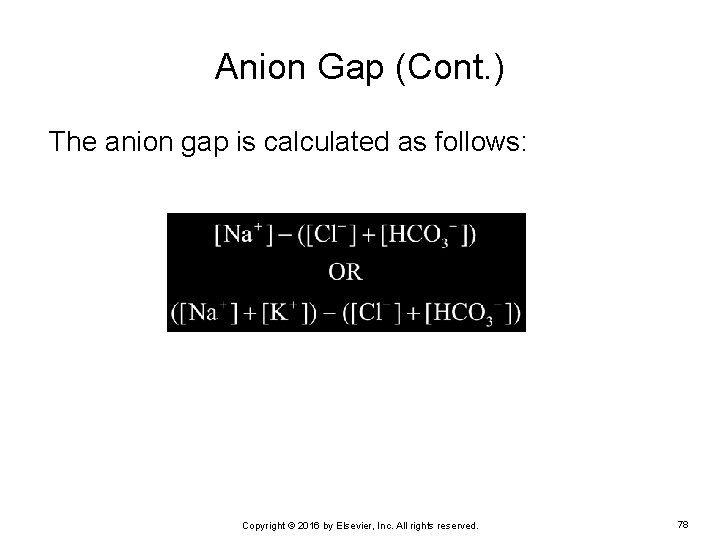

Anion Gap (Cont. ) The anion gap is calculated as follows: Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 78

Anion Gap (Cont. ) EXAMPLE: A 58 -year-old insulin-dependent woman with diabetes is admitted to the ED in a comatose state, with the following electrolyte profile: Sodium = 140 mmol/L Ø Potassium = 3. 5 mmol/L Ø Chloride = 105 mmol/L Ø Bicarbonate = 17 mmol/L Ø Calculate the anion gap using both formulas. Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 79

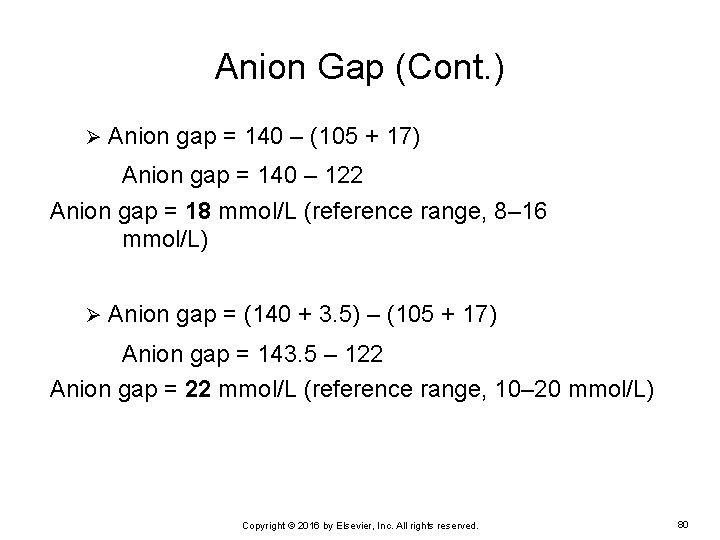

Anion Gap (Cont. ) Ø Anion gap = 140 – (105 + 17) Anion gap = 140 – 122 Anion gap = 18 mmol/L (reference range, 8– 16 mmol/L) Ø Anion gap = (140 + 3. 5) – (105 + 17) Anion gap = 143. 5 – 122 Anion gap = 22 mmol/L (reference range, 10– 20 mmol/L) Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 80

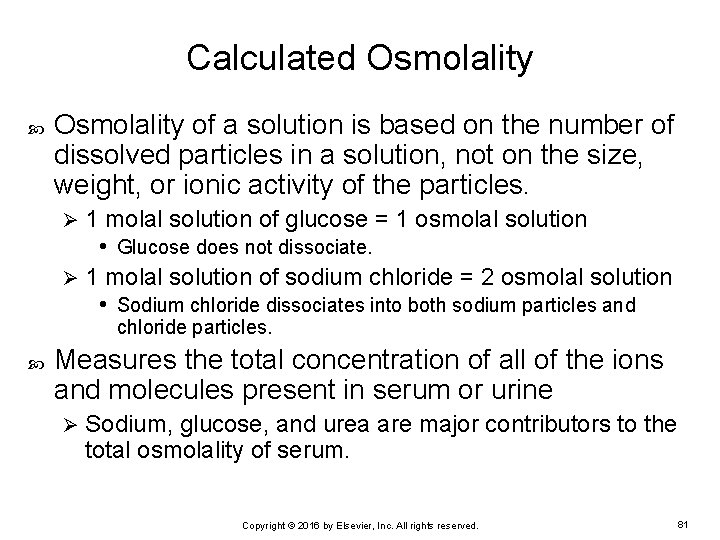

Calculated Osmolality of a solution is based on the number of dissolved particles in a solution, not on the size, weight, or ionic activity of the particles. 1 molal solution of glucose = 1 osmolal solution • Glucose does not dissociate. Ø 1 molal solution of sodium chloride = 2 osmolal solution • Sodium chloride dissociates into both sodium particles and Ø chloride particles. Measures the total concentration of all of the ions and molecules present in serum or urine Ø Sodium, glucose, and urea are major contributors to the total osmolality of serum. Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 81

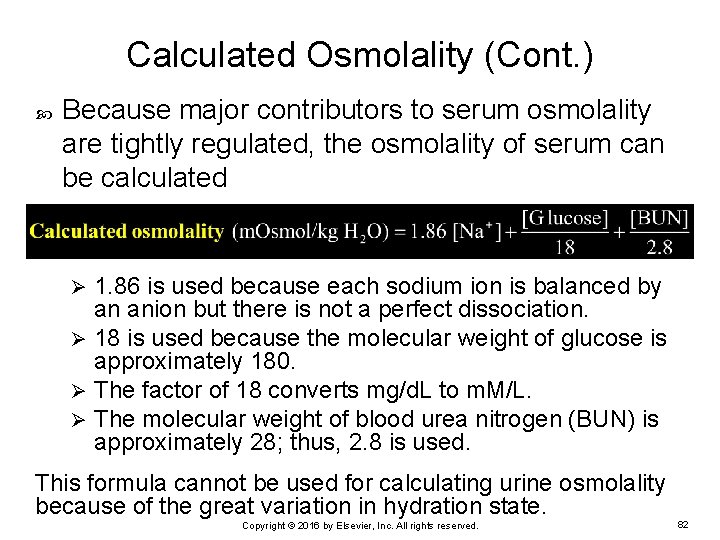

Calculated Osmolality (Cont. ) Because major contributors to serum osmolality are tightly regulated, the osmolality of serum can be calculated 1. 86 is used because each sodium ion is balanced by an anion but there is not a perfect dissociation. Ø 18 is used because the molecular weight of glucose is approximately 180. Ø The factor of 18 converts mg/d. L to m. M/L. Ø The molecular weight of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) is approximately 28; thus, 2. 8 is used. Ø This formula cannot be used for calculating urine osmolality because of the great variation in hydration state. Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 82

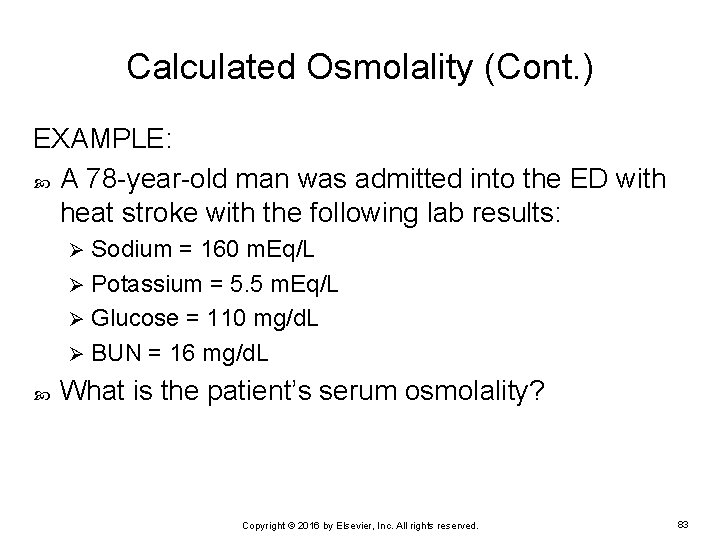

Calculated Osmolality (Cont. ) EXAMPLE: A 78 -year-old man was admitted into the ED with heat stroke with the following lab results: Sodium = 160 m. Eq/L Ø Potassium = 5. 5 m. Eq/L Ø Glucose = 110 mg/d. L Ø BUN = 16 mg/d. L Ø What is the patient’s serum osmolality? Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 83

Calculated Osmolality (Cont. ) To calculate the serum osmolality, use the following formula : Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 84

Osmolal Gap Osmolal gap: difference between the calculated osmolality and the measured osmolality Average osmolal gap = 0 to 10 m. Osm/kg H 2 O When the gap is elevated, it is usually due to particles other than sodium, glucose, or BUN. Ø The presence of ketones or alcohols such as ethanol in the serum can elevate the osmolal gap. Ø The gap may also be useful as a quality assurance measurement to detect technical errors. Ø Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 85

Osmolal Gap (Cont. ) EXAMPLE: A 54 -year-old woman was found unconscious and was admitted to the hospital with the following lab results: Sodium = 145 m. Eq/L Ø Potassium = 4. 5 m. Eq/L Ø Glucose = 95 mg/d. L Ø BUN = 12 mg/d. L Ø Serum osmolality = 320 m. Osm/kg Ø Serum Et. OH = 185 mg/d. L Ø What is the patient’s osmolal gap? Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 86

Osmolal Gap (Cont. ) First, calculate the osmolality: Calculated osmolality = 270 + 5. 3 + 4. 3 Calculated osmolality = 280 m. Osm/kg Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 87

Osmolal Gap (Cont. ) Osmolal gap = difference between calculated and measured osmolality 320 m. Osmol/kg – 280 m. Osmol/kg = 40 m. Osmol/kg Indicative of the presence of other dissolved particles in the serum Elevated ethanol concentration most likely the cause of the increased osmolal gap Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 88

Lipid Calculations Coronary artery disease (CAD) is one of the leading causes of death today Ø Determination of CAD risk factors is based on the following determinations: • Total cholesterol • High-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol • LDL cholesterol (LDL) • Triglycerides Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 89

Lipid Calculations (Cont. ) LDL cholesterol is calculated Ø The Friedewald formula is used for determining LDL cholesterol: Ø LDL cholesterol = Total cholesterol – (HDL + [Triglycerides ÷ 5]) Triglycerides/5 = estimation of VLDL cholesterol Ø Formula is not accurate if the triglyceride concentration is > 400 mg/d. L and assumes no other source of triglycerides such as chylomicrons Ø Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 90

Lipid Calculations (Cont. ) EXAMPLE: A 43 -year-old man with a family history of CAD has the following lipid profile analysis performed: Total cholesterol = 280 mg/d. L Ø Triglycerides = 150 mg/d. L Ø HDL cholesterol = 50 mg/d. L Ø Calculate the patient’s LDL cholesterol result. Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 91

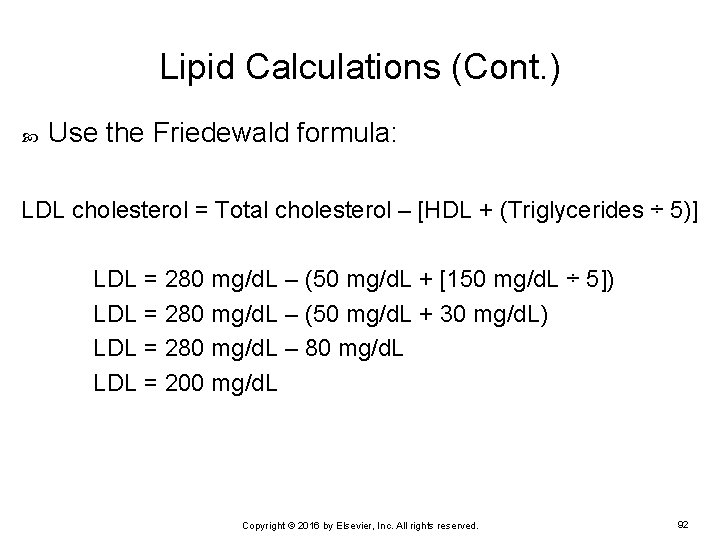

Lipid Calculations (Cont. ) Use the Friedewald formula: LDL cholesterol = Total cholesterol – [HDL + (Triglycerides ÷ 5)] LDL = 280 mg/d. L – (50 mg/d. L + [150 mg/d. L ÷ 5]) LDL = 280 mg/d. L – (50 mg/d. L + 30 mg/d. L) LDL = 280 mg/d. L – 80 mg/d. L LDL = 200 mg/d. L Copyright © 2016 by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 92

- Slides: 92