Chapter 52 Introduction to the Biosphere Biology 2013

Chapter 52 – Introduction to the Biosphere Biology 2013 -2014 Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

• Overview: The Scope of Ecology • Ecology – Is the scientific study of the interactions between organisms and the environment • These interactions – Determine both the distribution of organisms and their abundance Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

Organisms and the Environment • The environment of any organism includes – Abiotic, or nonliving components (Temperature, light, Water, Nutrients, Landscape) – Biotic, or living components (food, predation, and competition of resources) – All the organisms living in the environment, the biota Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

• Interactions between organisms and the environment limit the distribution of species • Ecologists ask: 1. What factors limit distribution? 2. What factors limit abundance? Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

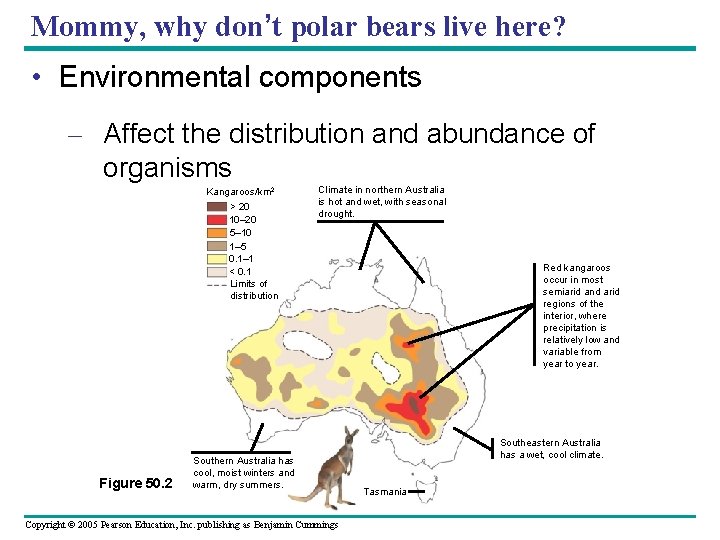

Mommy, why don’t polar bears live here? • Environmental components – Affect the distribution and abundance of organisms Kangaroos/km 2 > 20 10– 20 5– 10 1– 5 0. 1– 1 < 0. 1 Limits of distribution Figure 50. 2 Climate in northern Australia is hot and wet, with seasonal drought. Southern Australia has cool, moist winters and warm, dry summers. Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings Red kangaroos occur in most semiarid and arid regions of the interior, where precipitation is relatively low and variable from year to year. Southeastern Australia has a wet, cool climate. Tasmania

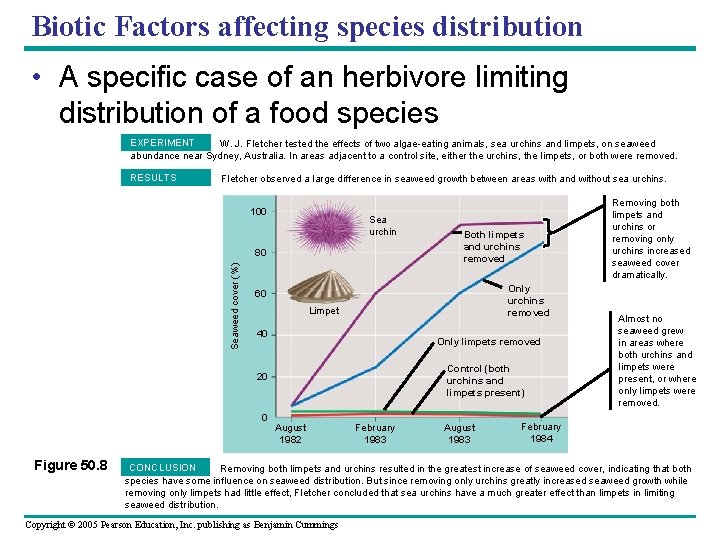

Biotic Factors affecting species distribution • A specific case of an herbivore limiting distribution of a food species EXPERIMENT W. J. Fletcher tested the effects of two algae-eating animals, sea urchins and limpets, on seaweed abundance near Sydney, Australia. In areas adjacent to a control site, either the urchins, the limpets, or both were removed. RESULTS Fletcher observed a large difference in seaweed growth between areas with and without sea urchins. 100 Sea urchin Seaweed cover (%) 80 Only urchins removed 60 Limpet 40 Only limpets removed Control (both urchins and limpets present) 20 0 Figure 50. 8 Both limpets and urchins removed August 1982 February 1983 August 1983 Removing both limpets and urchins or removing only urchins increased seaweed cover dramatically. Almost no seaweed grew in areas where both urchins and limpets were present, or where only limpets were removed. February 1984 CONCLUSION Removing both limpets and urchins resulted in the greatest increase of seaweed cover, indicating that both species have some influence on seaweed distribution. But since removing only urchins greatly increased seaweed growth while removing only limpets had little effect, Fletcher concluded that sea urchins have a much greater effect than limpets in limiting seaweed distribution. Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

Wind • Wind – Amplifies the effects of temperature on organisms by increasing heat loss due to evaporation and convection – Can change the morphology of plants Figure 50. 9 Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

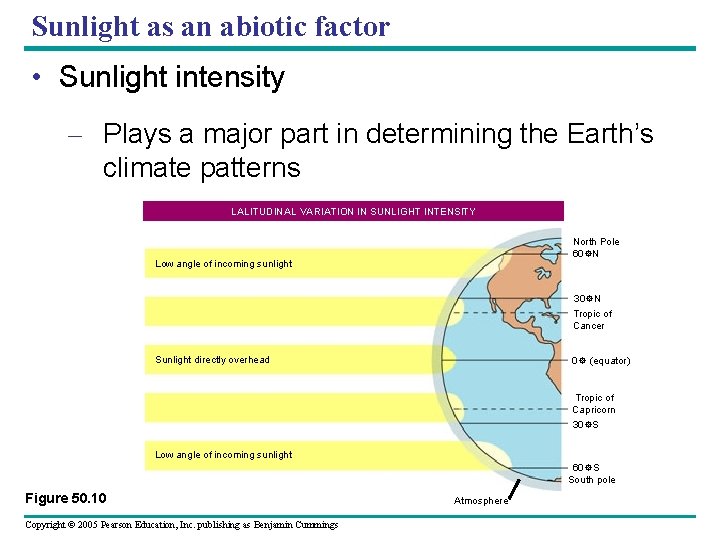

Sunlight as an abiotic factor • Sunlight intensity – Plays a major part in determining the Earth’s climate patterns LALITUDINAL VARIATION IN SUNLIGHT INTENSITY North Pole 60 N Low angle of incoming sunlight 30 N Tropic of Cancer Sunlight directly overhead 0 (equator) Tropic of Capricorn 30 S Low angle of incoming sunlight 60 S South pole Figure 50. 10 Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings Atmosphere

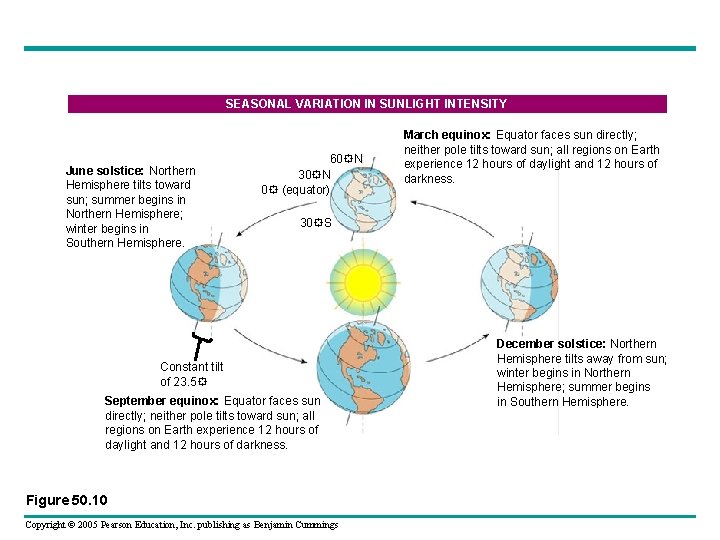

SEASONAL VARIATION IN SUNLIGHT INTENSITY June solstice: Northern Hemisphere tilts toward sun; summer begins in Northern Hemisphere; winter begins in Southern Hemisphere. 60 N 30 N 0 (equator) March equinox: Equator faces sun directly; neither pole tilts toward sun; all regions on Earth experience 12 hours of daylight and 12 hours of darkness. 30 S Constant tilt of 23. 5 September equinox: Equator faces sun directly; neither pole tilts toward sun; all regions on Earth experience 12 hours of daylight and 12 hours of darkness. Figure 50. 10 Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings December solstice: Northern Hemisphere tilts away from sun; winter begins in Northern Hemisphere; summer begins in Southern Hemisphere.

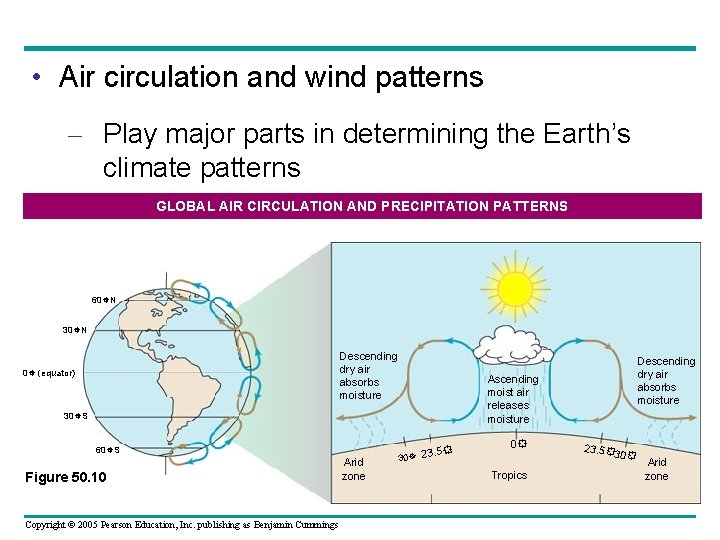

• Air circulation and wind patterns – Play major parts in determining the Earth’s climate patterns GLOBAL AIR CIRCULATION AND PRECIPITATION PATTERNS 60 N 30 N Descending dry air absorbs moisture 0 (equator) Ascending moist air releases moisture 30 S 60 S Figure 50. 10 Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings Arid zone Descending dry air absorbs moisture 30 23. 5 0 Tropics 23. 5 30 Arid zone

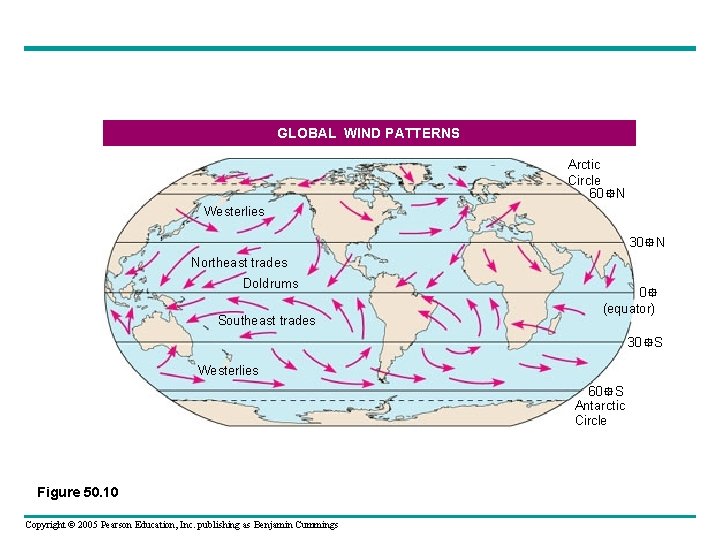

GLOBAL WIND PATTERNS Arctic Circle 60 N Westerlies 30 N Northeast trades Doldrums Southeast trades 0 (equator) 30 S Westerlies 60 S Antarctic Circle Figure 50. 10 Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

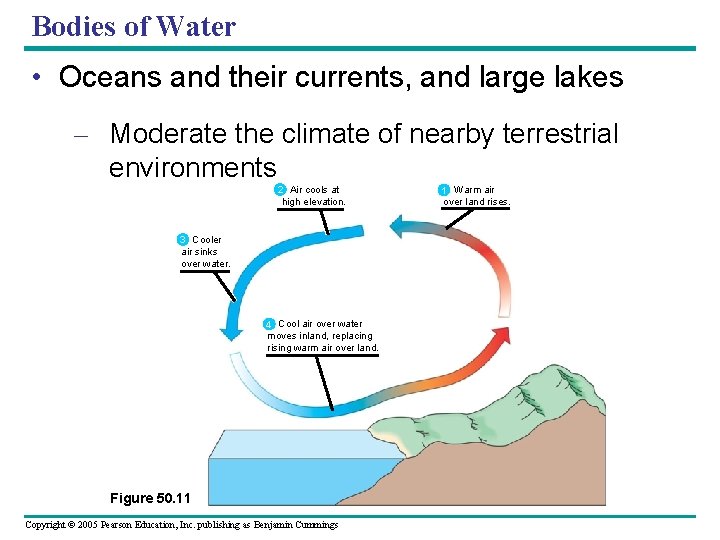

Bodies of Water • Oceans and their currents, and large lakes – Moderate the climate of nearby terrestrial environments 2 Air cools at high elevation. 3 Cooler air sinks over water. 4 Cool air over water moves inland, replacing rising warm air over land. Figure 50. 11 Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings 1 Warm air over land rises.

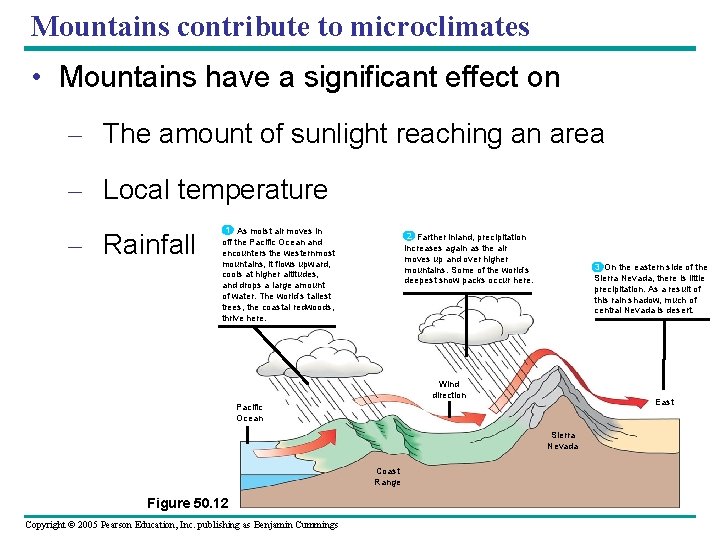

Mountains contribute to microclimates • Mountains have a significant effect on – The amount of sunlight reaching an area – Local temperature – Rainfall 1 As moist air moves in off the Pacific Ocean and encounters the westernmost mountains, it flows upward, cools at higher altitudes, and drops a large amount of water. The world’s tallest trees, the coastal redwoods, thrive here. 2 Farther inland, precipitation increases again as the air moves up and over higher mountains. Some of the world’s deepest snow packs occur here. 3 On the eastern side of the Sierra Nevada, there is little precipitation. As a result of this rain shadow, much of central Nevada is desert. Wind direction East Pacific Ocean Sierra Nevada Coast Range Figure 50. 12 Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

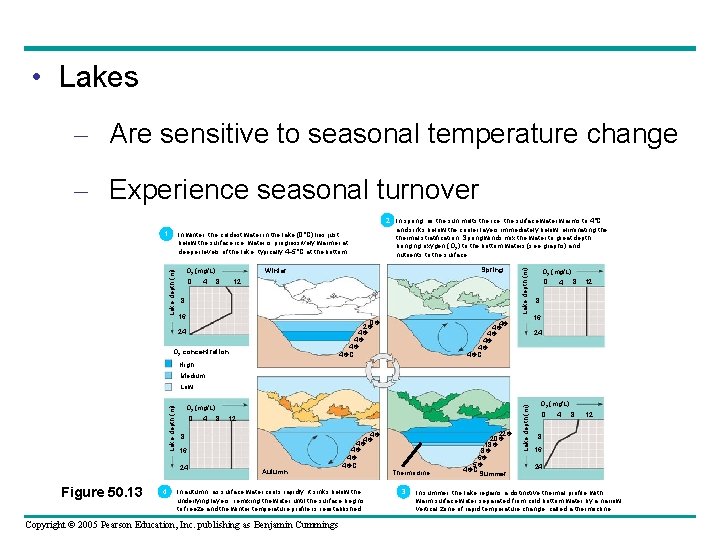

• Lakes – Are sensitive to seasonal temperature change – Experience seasonal turnover Lake depth (m) In winter, the coldest water in the lake (0°C) lies just below the surface ice; water is progressively warmer at deeper levels of the lake, typically 4– 5°C at the bottom. O 2 (mg/L) 0 4 Spring Winter 8 12 8 16 0 2 4 4 C 24 O 2 concentration Lake depth (m) 1 2 In spring, as the sun melts the ice, the surface water warms to 4°C and sinks below the cooler layers immediately below, eliminating thermal stratification. Spring winds mix the water to great depth, bringing oxygen (O 2) to the bottom waters (see graphs) and nutrients to the surface. 4 4 4 C O 2 (mg/L) 0 4 8 12 8 16 24 High Medium O 2 (mg/L) 0 4 8 12 8 16 24 Figure 50. 13 4 Autumn 4 4 4 C In autumn, as surface water cools rapidly, it sinks below the underlying layers, remixing the water until the surface begins to freeze and the winter temperature profile is reestablished. Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings Thermocline 3 22 20 18 8 6 5 4 C Summer Lake depth (m) Low O 2 (mg/L) 0 4 8 12 8 16 24 In summer, the lake regains a distinctive thermal profile, with warm surface water separated from cold bottom water by a narrow vertical zone of rapid temperature change, called a thermocline.

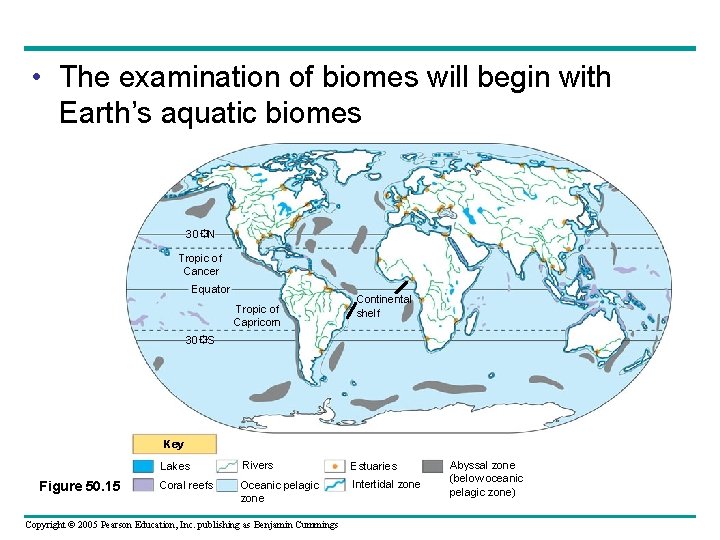

• The examination of biomes will begin with Earth’s aquatic biomes 30 N Tropic of Cancer Equator Tropic of Capricorn Continental shelf 30 S Key Figure 50. 15 Lakes Rivers Estuaries Coral reefs Oceanic pelagic zone Intertidal zone Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings Abyssal zone (below oceanic pelagic zone)

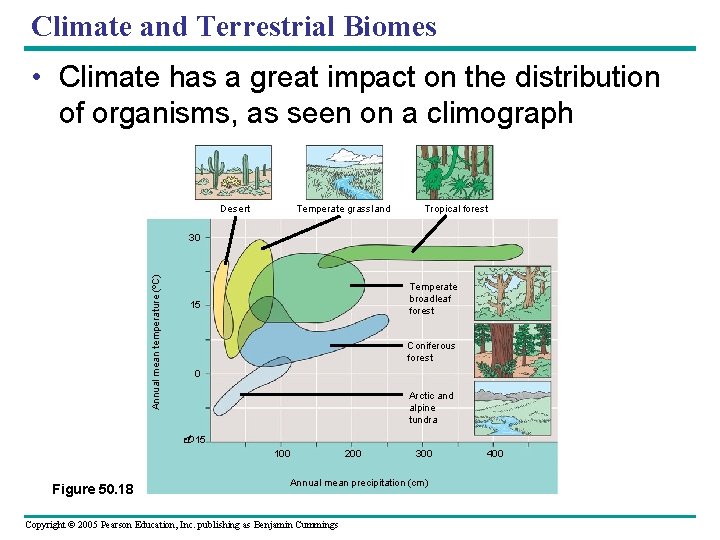

Climate and Terrestrial Biomes • Climate has a great impact on the distribution of organisms, as seen on a climograph Temperate grassland Desert Tropical forest Annual mean temperature (ºC) 30 Temperate broadleaf forest 15 Coniferous forest 0 Arctic and alpine tundra 15 100 Figure 50. 18 200 300 Annual mean precipitation (cm) Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings 400

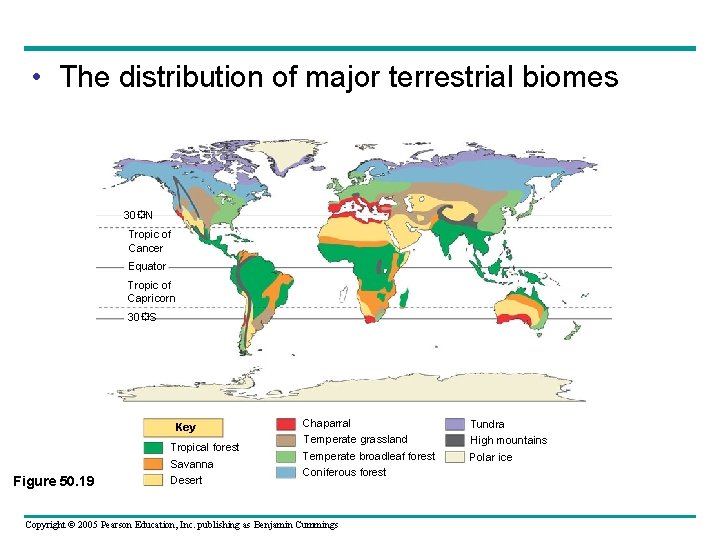

• The distribution of major terrestrial biomes 30 N Tropic of Cancer Equator Tropic of Capricorn 30 S Key Tropical forest Figure 50. 19 Savanna Desert Chaparral Temperate grassland Temperate broadleaf forest Coniferous forest Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings Tundra High mountains Polar ice

• Tropical forest TROPICAL FOREST Figure 50. 20 A tropical rain forest in Borneo Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

• Desert DESERT Figure 50. 20 The Sonoran Desert in southern Arizona Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

• Savanna SAVANNA Figure 50. 20 A typical savanna in Kenya Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

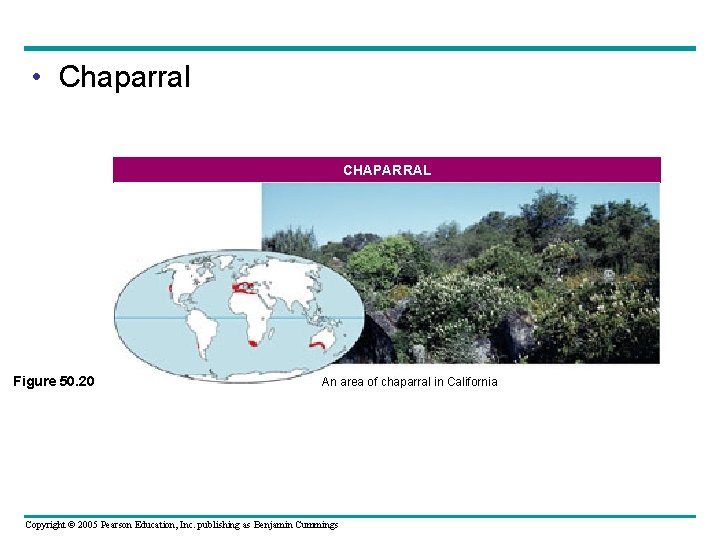

• Chaparral CHAPARRAL Figure 50. 20 An area of chaparral in California Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

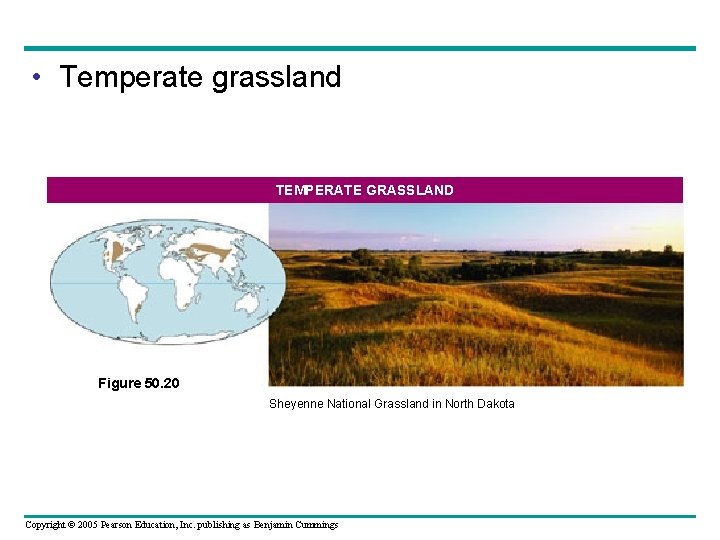

• Temperate grassland TEMPERATE GRASSLAND Figure 50. 20 Sheyenne National Grassland in North Dakota Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

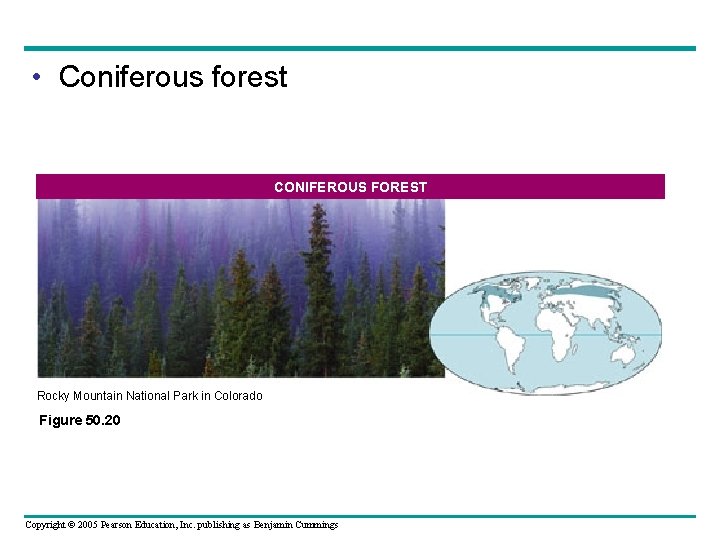

• Coniferous forest CONIFEROUS FOREST Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado Figure 50. 20 Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

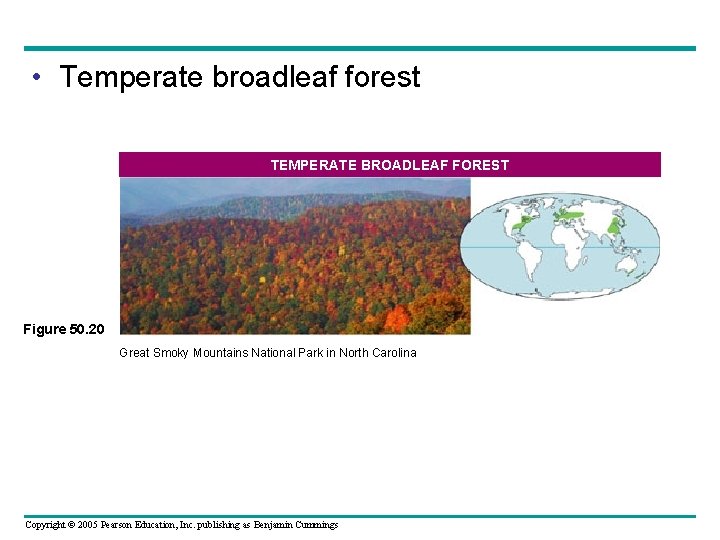

• Temperate broadleaf forest TEMPERATE BROADLEAF FOREST Figure 50. 20 Great Smoky Mountains National Park in North Carolina Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

• Tundra TUNDRA Figure 50. 20 Denali National Park, Alaska, in autumn Copyright © 2005 Pearson Education, Inc. publishing as Benjamin Cummings

- Slides: 25