Chapter 5 Theoretical considerations Factors of location The

- Slides: 32

Chapter 5: Theoretical considerations • • • Factors of location The Weberian model Technique and Scale considerations How and why firms grow Geographic organization of corporations Economic geography and social relations The Product cycle Business cycles and regional landscapes The State and economic geography

Introduction • Theory is a way of looking at the world, an explanation, a way of making sense of the relationships among variables. Theory is what separates description from explanation. • A theory allows us to establish causality, to test hypotheses, to justify arguments, and to make claims to truth. • Theories are simplifications about the world that allow us to gain understanding. • Theories are thus indispensable to knowing how the world works, whether in the formal intellectual world or in our everyday lives at home and at work. • Understanding theory is not a choice, because theory is inescapable. • This chapter offers an overview of some of the major conceptual approahes and topics in economic geography.

Factors of production • The major factors that shape a firm’s location include labor, land, capital, and managerial and technical skills. • All these are necessary for production, and all exhibit spatial variations in both quantity and quality.

Factors of production - Labor • For most industries (except those in the primary economic sector concerned with extractive activities), labor is the most important determinant of location, especially at the regional, national, and global scales. – At local scales, such as within a commuting field, other factors such as rents may become more significant. • When firms make location decisions, they often begin by examining the geography of labor availability, productivity, skills, and militancy. • The degree to which firms rely on labor, however, varies considerably among different sectors of the economy, and even among different firms, which may adopt different production techniques.

Factors of production - Labor • Relative contribution of labor to the cost structure and value added – E. g. automobile industry – high, petroleum industry – very low. • The demand for labor depends on how labor-intensive or capital-intensive a given production process is. – Over time, most industries have become increasingly capitalintensive (use of tractors in agriculture, machinery and robots in manufacturing, or computers in services and office work) • Supply of labor in a given region affects its cost – high birth rates → supply high → labor costs low → little incentive to mechanize – low birth rates → supply low → labor costs high → more capitalintensive

Factors of production - Labor • Demographic structure of a region and migration shape the supply of labor – E. g. fast food industry, prefers young workers who will work for minimum wage • In theory, because labor is relatively mobile, regional differences in the supply and demand for labor should move toward equilibrium over time. – E. g. 19 th century migration of people from rural areas to the city in countries such as UK and USA, and the 20 th century movement of labor from the Third World to the wealthy countries of northern Europe: from the Caribbean and South Asia to UK, from North Africa to France, and from Turkey to Germany. • Response of labor to changing market conditions is not instantaneous. – Variations in the cost of labor within and among countries

Factors of production - Labor • It is a common myth, but simply not true, that firms always want the cheapest labor possible. – Productivity is also important. • The skill level of a given occupation greatly affects the size of its labor market. • E. g. corporate management, professional services, and university professors • Labor is also important because the labor factor is saturated with politics. – Able to resist the conditions of exploitation, to go on strike, to engage in slowdowns, or to unionize. – In addition to costs of labor, firms should consider working conditions, . . . • On the world scale, developed countries have higher wage rates than newly industrializing countries. – older, established industrial countries → highly unionized workers – newly industrializing countries → less unionized workers

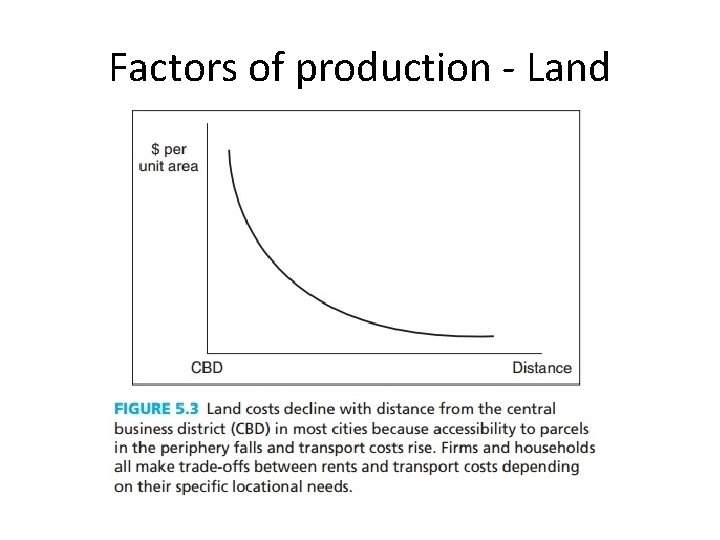

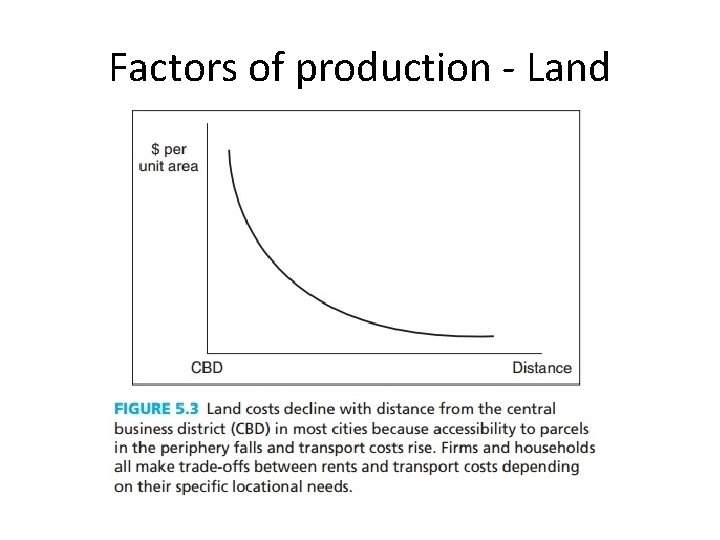

Factors of production - Land • At local scale, land availability and cost are the most important locational factors affecting firms’ location decisions. • The primary determinant of the cost of land is its accessibility. Transport costs (the measure of accessibility) determine the location rent of parcels at different distances from the city. • However, not all firms necessarily seek out low-cost land. The imperative to do so depends on the trade-off between land transportation costs that firms make to maximize their profits. – The demand for land the need to agglomerate are inversely related.

Factors of production - Land

Factors of production - Capital • Under capitalism, capital plays a dominant role in structuring the production process. – fixed capital (machinery, equipment, and plant buildings) –often expensive – financial capital (intangible revenues, including corporate profits, savings, loans, stocks, bonds, and other financial instruments) - most mobile production factor • The age of the capital stock of a region, or how recent the technology it deploys is, greatly affects its overall productivity levels. • E. g. after World War II, countries like Japan and Germany have enjoyed high level of productivity growth • One of capital’s crucial geographic mobility; advantages over labor is – Shifting production to low wage, low unionization, or offer incentives regions.

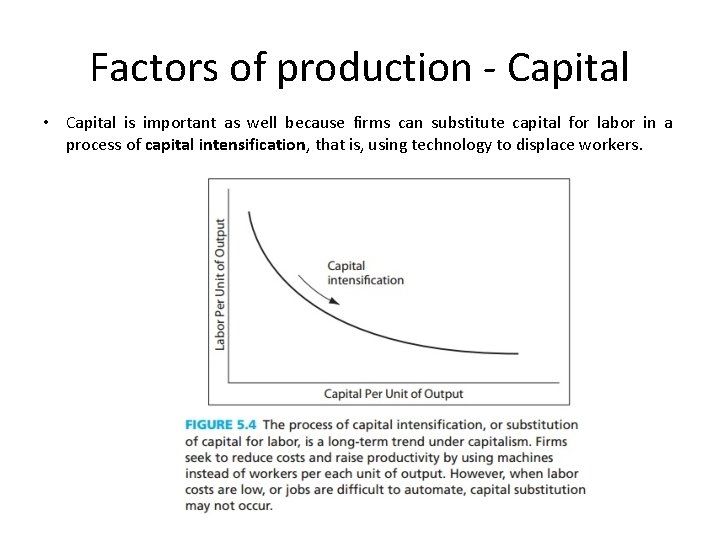

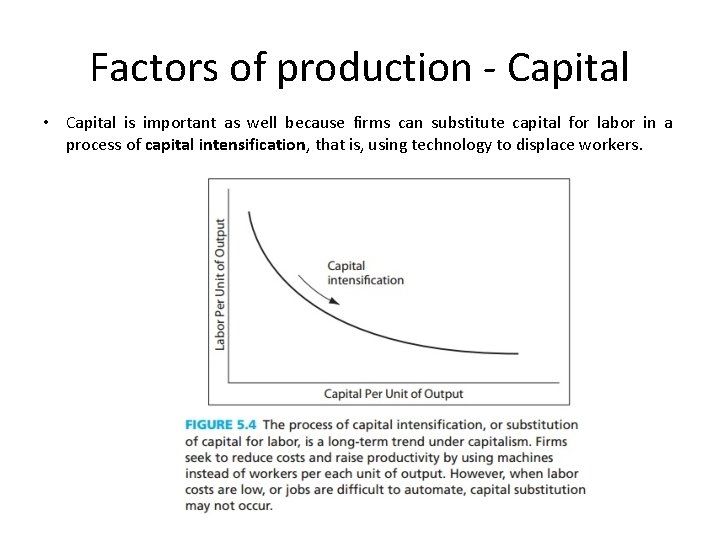

Factors of production - Capital • Capital is important as well because firms can substitute capital for labor in a process of capital intensification, that is, using technology to displace workers.

Managerial and Technical Skills • Managerial and technical skills are also required for any type of production. • Forms of management – Sole proprietorships, partnerships, corporations • Within firms, management forms an important part of the corporate division of labor. • In large firms, headquarters decides a firm’s overall competitive strategy, what markets and products to focus on, labor policies, mergers and acquisitions, and types of financing. • Technical skills are those necessary for the continued invention of new products and processes. These skills are generally categorized as research and development (R&D).

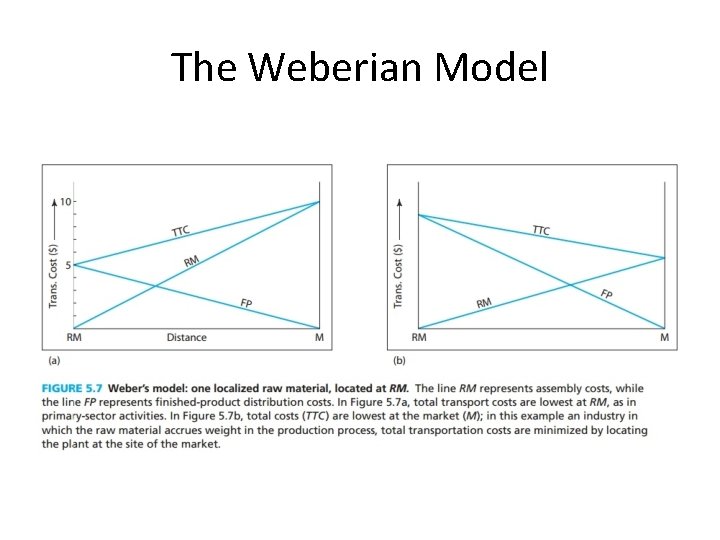

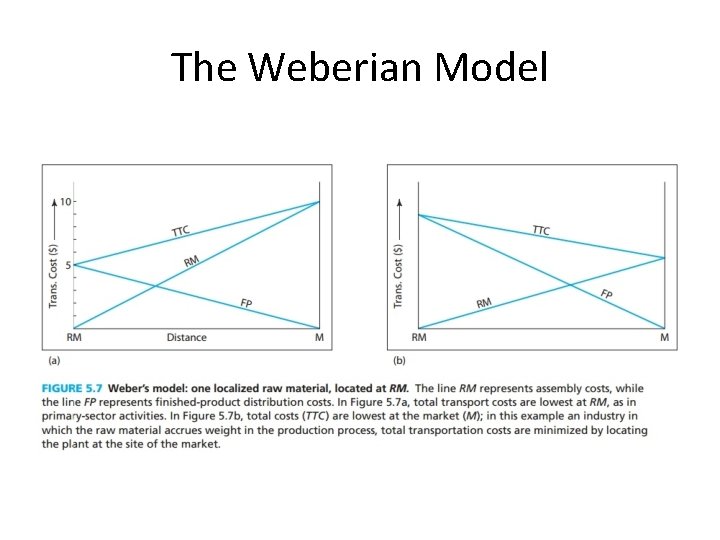

The Weberian Model • Weber’s approach emphasized the role of transportation costs in the location decisions of individual firms. • We must consider – (1) the costs of assembling raw materials (RM), – (2) the costs of distributing the finished product (FP), and – (3) the total transportation costs (TTC). – The best location for a manufacturing plant is the point at which total transportation costs are minimized.

The Weberian Model

Weber in Today’s World • First, not all firms need to minimize transport costs. – rent–transport trade-off • Second, the production process is much more complex than it was in the early twentieth century. – Many plants begin with semifinished items and components rather than with raw materials. Producers’ goods seldom lose large amounts of weight; therefore, there is not much of a tendency to locate near raw materials. • Unrealistic view of transportation costs as a linear function of distance. • Because of fixed costs, especially terminal costs, the mileage costs of long hauls are less per unit of weight than those of short hauls.

Weber in Today’s World Two other developments have a bearing on how choices of industrial location have changed: 1. Transportation costs have been declining in the long run. – This decline increases the importance of other locational factors, particularly labor costs and productivity. 2. Brainpower has been steadily displacing muscle and machine power and transforming natural resources. – Widespread transmaterialization of resources has occurred as smaller, lighter products are made from resources to which high technology and brainpower have been added. 3. Finally, real-world patterns are evolutionary; they are not the result of decisions made by optimizers. – Most real-world decisions do not result in the selection of the best (most profitable) locations. – Locational decisions, once made, often lead to industrial inertia, the tendency to continue investing in a nonoptimal site even if more optimal locations exist.

Technique and Scale considerations • The establishment of any manufacturing plant in a market economy involves the interdependent decision-making criteria of scale—the size of the total output—and technique—the particular combination of inputs that are used to produce an output. • Technique has an important effect on a firm’s locational decision. • Whether or not substitution between production factors occurs depends on the relative costs and productivity of the two inputs and the scale and locational decisions already made by the firm. – E. g. labor costs rise at a given location, the firm may choose to substitute capital for labor at that location, or it may opt to change locations to take advantage of lower labor costs. – Textile firms in US migrated first from Northeast to Southeast, then further to Mexico, Brazil, Taiwan, South Korea, and Singapore, and then left many of those for even cheaper locations such as China. – Limits to substitution (petroleum refining, garment manufacture)

Principles of Scale Economies • Division of labor – Mass production, Workers get more efficient, Use of unskilled labor, Requires large scale – E. g. U. S. automobile industry – Three-shift firm versus single-shift firm • Economies of scale, or scale economies, refer to the reductions in costs associated with the production of output in large quantities.

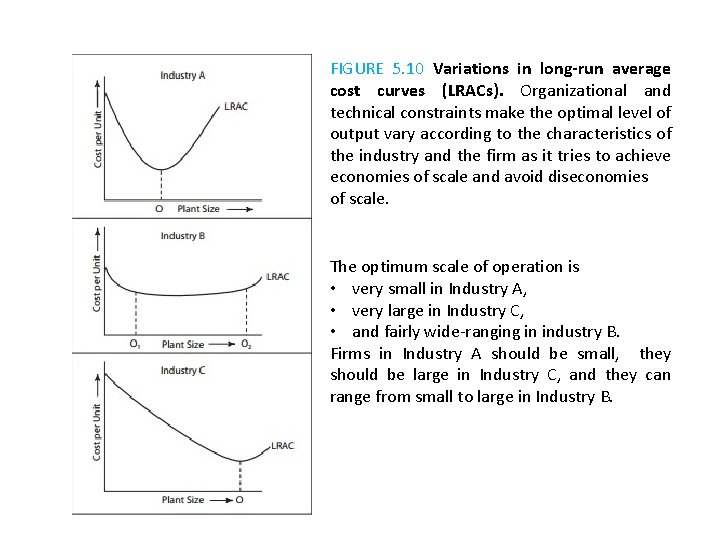

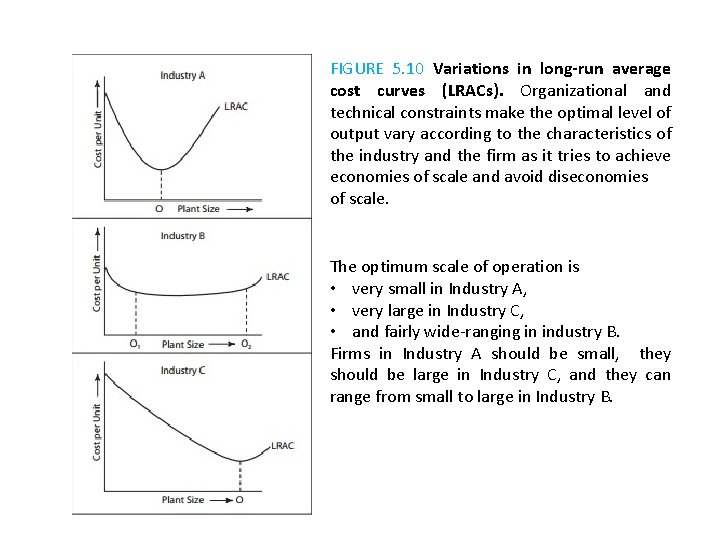

FIGURE 5. 10 Variations in long-run average cost curves (LRACs). Organizational and technical constraints make the optimal level of output vary according to the characteristics of the industry and the firm as it tries to achieve economies of scale and avoid diseconomies of scale. The optimum scale of operation is • very small in Industry A, • very large in Industry C, • and fairly wide-ranging in industry B. Firms in Industry A should be small, they should be large in Industry C, and they can range from small to large in Industry B.

Vertical and Horizontal Integration and Diversification • Besides simply increasing plant size, two other means are commonly employed for effecting scale changes. • Vertical integration - firms purchase raw material sources or distribution facilities. – E. g. Large oil companies are often vertically integrated; they control exploration, drilling, refining, and retailing. • Horizontal integration - firm gains an increasing market share of a given niche of a particular industry. – Oligopolistic market • Diversification - A company may produce many unrelated products, each of its operations having elements of horizontal and vertical integration.

Interfirm Scale Economies: Agglomeration • Scale economies also apply to clusters of firms in the same or related industries. By clustering, unit costs can be lowered for all firms, in ways that could not occur if they were spatially separate. – E. g. the computer firms located in California’s Silicon Valley. • These economies, called agglomeration economies, take several forms. – Production linkages, Service linkages, Marketing linkages • Positive external economies of scale - knowledge spillovers rely on frequent, repeated, and sustained interactions among individuals and firms in a given location, which creates synergies interactions that generate benefits (i. e. , ideas) that would not be possible if actors (firms, individuals) operated in isolation. – in most economic sectors, research and intellectual activity are concentrated in or near large metropolitan areas, whereas unskilled, low-wage occupations that involve little creative activity (e. g. , branch plants, back offices) tend to disperse to smaller towns.

Evaluation of Industrial Location Theory • • • The final location chosen by an industry is not always determined by transportation costs, nor by production costs at the site. There are several factors that complicate locational decisions: 1. A firm may have more than one critical site or situation factor, each of which suggests a different location. 2. Even if a firm clearly identifies its critical factor, more than one critical location may emerge. 3. A firm cannot always precisely calculate costs of situation and site factors within the company or at various locations due to unknown information. 4. A firm may select its location on the basis of inertia and company history. Once a firm is in a particular community, expansion in the same place is likely to be cheaper than moving to a new location. 5. The calculations of an optimal location can be altered by a government grant, loans, or tax breaks. 6. Noneconomic factors play important roles in footloose industries that have gravitated to coastal areas in the Sunbelt of the United States because of recreational opportunities and other amenities.

How and Why Firms Grow • Firms expand for two reasons: survival and growth. • The majority of firms in an economy remain small and peripheral. – Financial barriers (i. e. , lack of investment capital and necessary information and management skills) • How a firm grows depends on the strategy that it follows and the methods that it selects to implement its strategy. • Growth strategies are either integration or diversification. • Methods for achieving growth are internal or external to the firm. • Whatever strategy and method are adopted, corporate growth typically involves the addition of new factories and, thus, a change in geography.

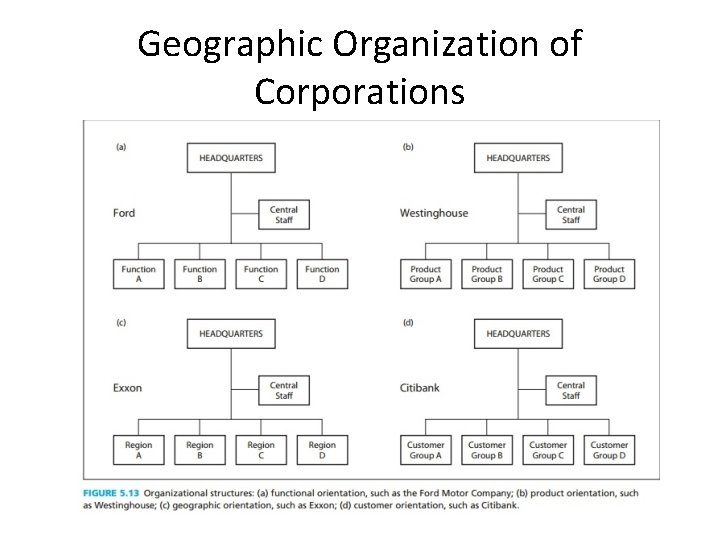

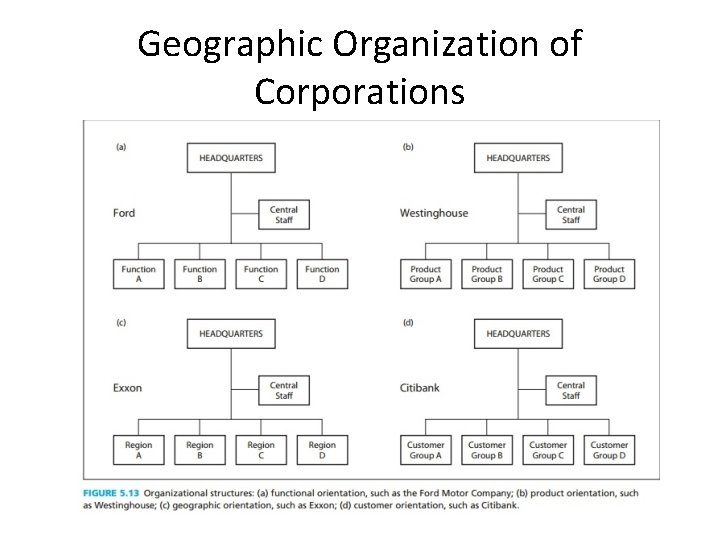

Geographic Organization of Corporations • Companies organize themselves hierarchically in a variety of ways to administer and coordinate their activities. The basic formats are • (1) functional orientation, • (2) product orientation, • (3) geographic orientation, and • (4) customer orientation. • A fifth format, which is a combination of at least two of the basic formats, is called a matrix structure.

Geographic Organization of Corporations

Economic Geography and Social Relations • The crucial social relation of production is between owners of the means of production and the workers employed to operate these means. • Under capitalism, the means of production are privately owned, which divides people into owners of capital and those who must sell their labor power in order to survive. • Owners of capital - the capitalist class that came to power beginning in the sixteenth century (Chapter 2)—control the labor process and extract surplus value through the exploitation of workers. • Competitive relations exist among owners; cooperative and antagonistic relations emerge between owners (capital) and workers (labor).

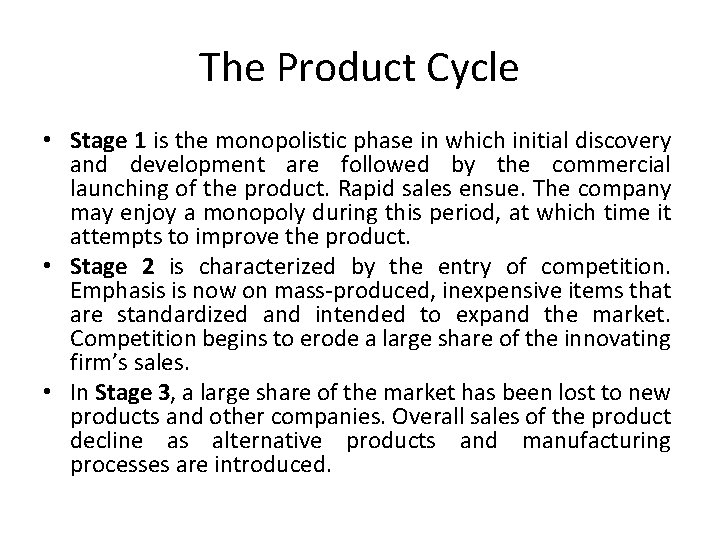

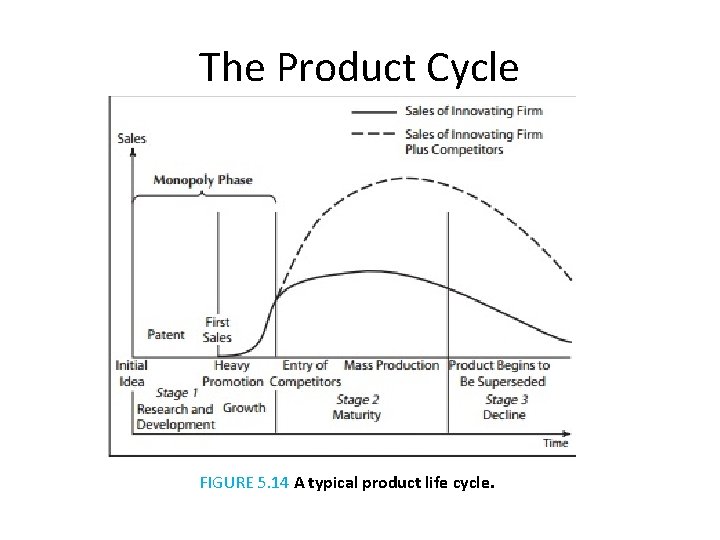

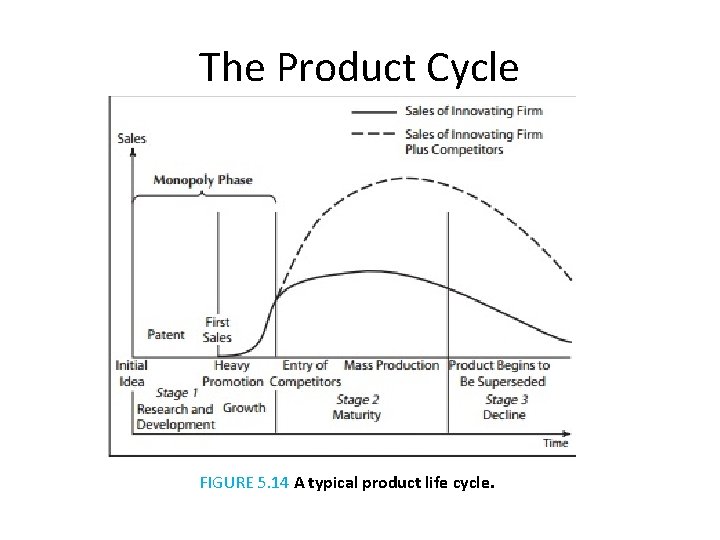

The Product Cycle • Stage 1 is the monopolistic phase in which initial discovery and development are followed by the commercial launching of the product. Rapid sales ensue. The company may enjoy a monopoly during this period, at which time it attempts to improve the product. • Stage 2 is characterized by the entry of competition. Emphasis is now on mass-produced, inexpensive items that are standardized and intended to expand the market. Competition begins to erode a large share of the innovating firm’s sales. • In Stage 3, a large share of the market has been lost to new products and other companies. Overall sales of the product decline as alternative products and manufacturing processes are introduced.

The Product Cycle FIGURE 5. 14 A typical product life cycle.

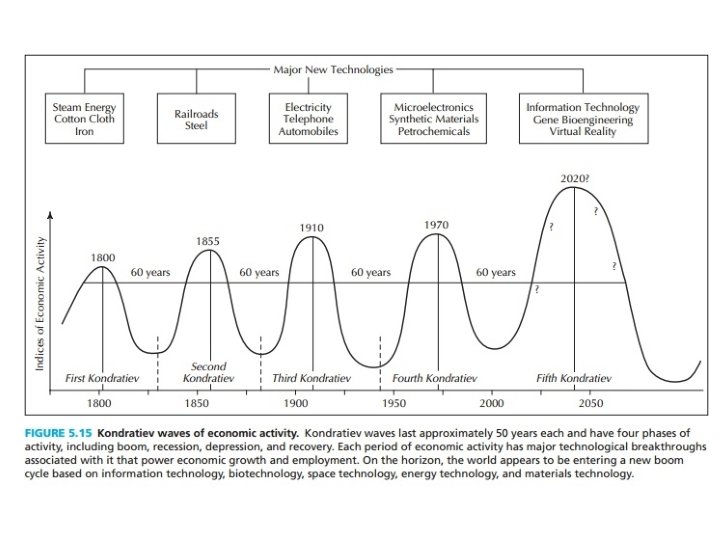

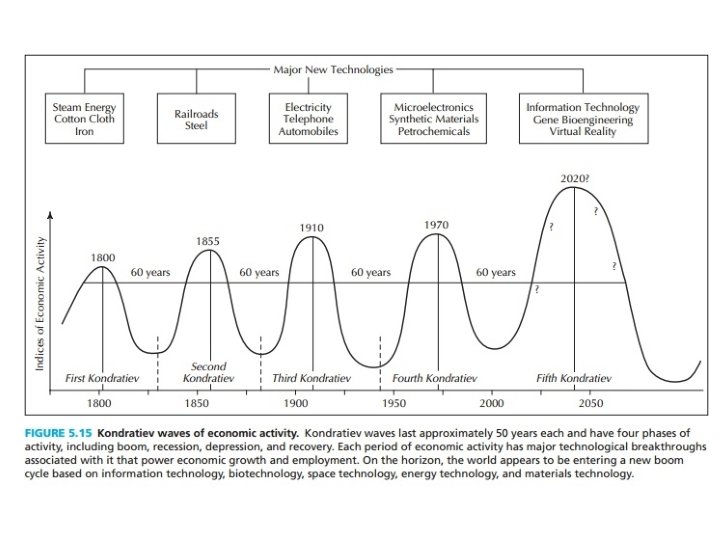

Business Cycles and Regional Landscapes • Examining historical data on changes in output, wages, prices, and profits, Kondratiev hypothesized that industrial countries of the world experienced successive waves of growth and decline since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. • Based on the emergence of key technologies, these long cycles have a periodicity of roughly 50 to 75 years’ duration. • The reasons that underlie the duration of these waves reflect long-term trends in the rate of capital formation and depreciation; as fixed capital investments reach the end of their useful economic life, the drag on productivity they create generates incentives to search for new technologies.

Business Cycles and Regional Landscapes • Over different business cycles, several industries may locate in one region, each leaving its own imprint on the local landscape. • Each constructs a labor force, invests in buildings, and shapes the infrastructure in ways that suit its needs (and profits). • From the perspective of each region, therefore, business cycles resemble waves of investment and disinvestment. • Each wave, or Kondratiev cycle, deeply shapes the local economy, landscape, and social structure and leaves a lasting imprint on a region that is not easily erased.

The State and Economic Geography • Economic landscapes of capitalism are not simply the products of “free markets, ” but also involve the role of the state. • The state does what no individual or firm can do, tackling problems too big for private firms and providing necessary, but unprofitable, services. • One way that states shape economies is through the creation and enforcement of a legal system. • The state is also heavily involved in setting fiscal and monetary policy. • The state has a huge impact on economic landscapes through the construction of an infrastructure, including transportation and communication networks, water and electrical supply systems. • The state provide public services. • The state shapes the labor markets of capitalist societies in many ways, both directly and indirectly. • Housing markets are another area shaped by the state. • Finally, the state acts as an agent in international issues.