Chapter 5 RNABased technology 1 Antisense RNA 2

Chapter 5 RNA-Based technology 國立台灣海洋大學養殖系 呂明偉

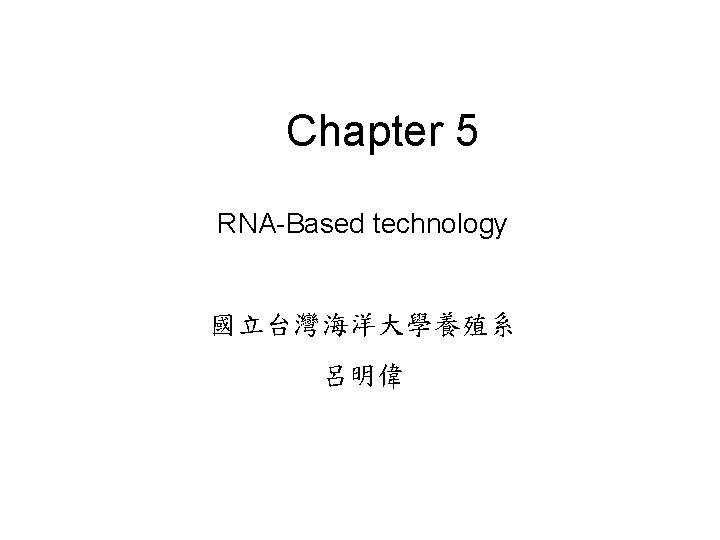

1. Antisense RNA 2. RNAi 3. Ribozyme FIGURE 5. 1 Antisense RNA Is Complementary to Messenger RNA Transcription from both strands of DNA creates two different RNA molecules, on the left, the messenger RNA, and on the right, antisense RNA. These two have complementary sequences and can form double-stranded RNA. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 2

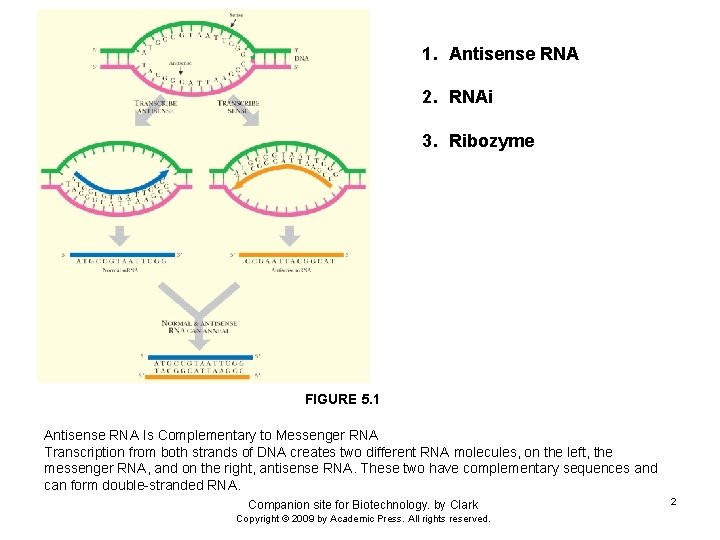

RNase H recognize 7 -base pair heteroduplex Need not very long Neurospora. frq gene. FIGURE 5. 2 Antisense RNA Blocks Protein Expression (A) The complementary sequence of antisense RNA binds to specific regions on m. RNA. This can block the ribosome binding sites or splice junctions. (B) Antisense DNA targets m. RNA for degradation. When antisense DNA binds to m. RNA, the heteroduplex of RNA and DNA triggers RNase H to degrade the m. RNA. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 3

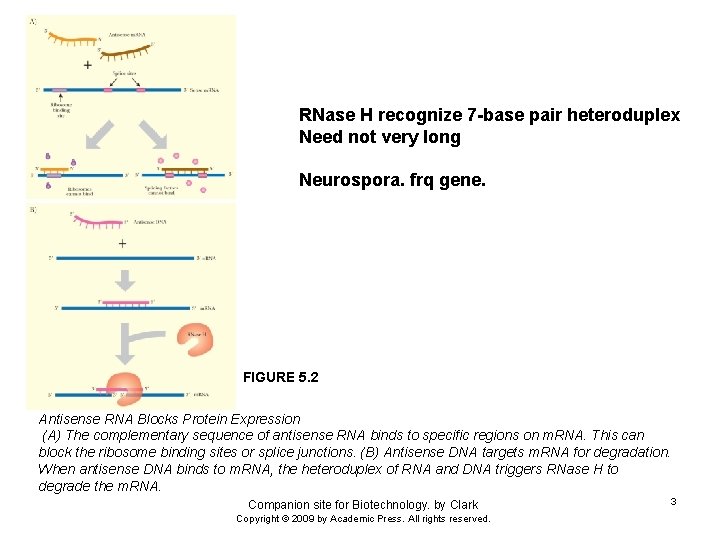

FIGURE 5. 3 Making Antisense in the Laboratory (A) Antisense oligonucleotides. Small oligonucleotides are synthesized chemically and injected into a cell to block m. RNA translation. (B) Antisense genes. Genes are cloned in inverted orientation so that the sense strand is transcribed. This yields antisense RNA that anneals to the normal m. RNA, preventing its expression. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 4

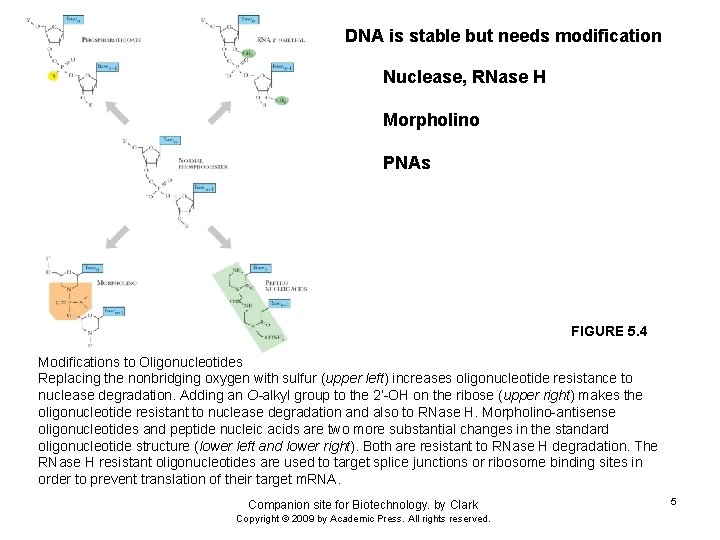

DNA is stable but needs modification Nuclease, RNase H Morpholino PNAs FIGURE 5. 4 Modifications to Oligonucleotides Replacing the nonbridging oxygen with sulfur (upper left) increases oligonucleotide resistance to nuclease degradation. Adding an O-alkyl group to the 2’-OH on the ribose (upper right) makes the oligonucleotide resistant to nuclease degradation and also to RNase H. Morpholino-antisense oligonucleotides and peptide nucleic acids are two more substantial changes in the standard oligonucleotide structure (lower left and lower right). Both are resistant to RNase H degradation. The RNase H resistant oligonucleotides are used to target splice junctions or ribosome binding sites in order to prevent translation of their target m. RNA. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 5

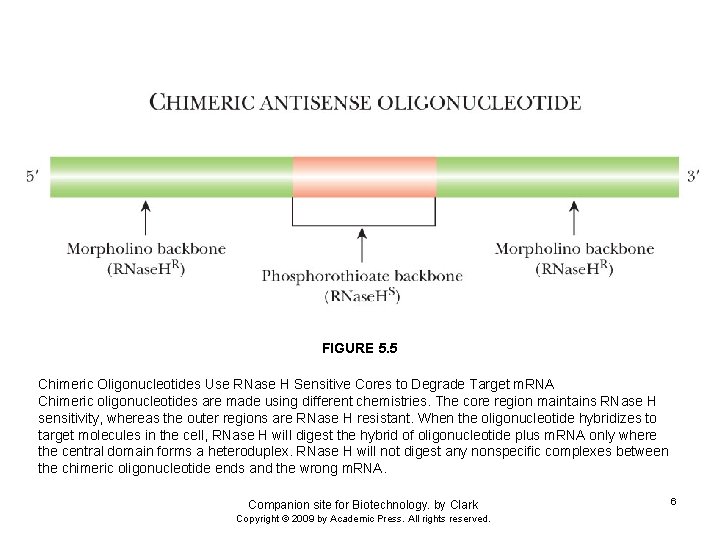

FIGURE 5. 5 Chimeric Oligonucleotides Use RNase H Sensitive Cores to Degrade Target m. RNA Chimeric oligonucleotides are made using different chemistries. The core region maintains RNase H sensitivity, whereas the outer regions are RNase H resistant. When the oligonucleotide hybridizes to target molecules in the cell, RNase H will digest the hybrid of oligonucleotide plus m. RNA only where the central domain forms a heteroduplex. RNase H will not digest any nonspecific complexes between the chimeric oligonucleotide ends and the wrong m. RNA. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 6

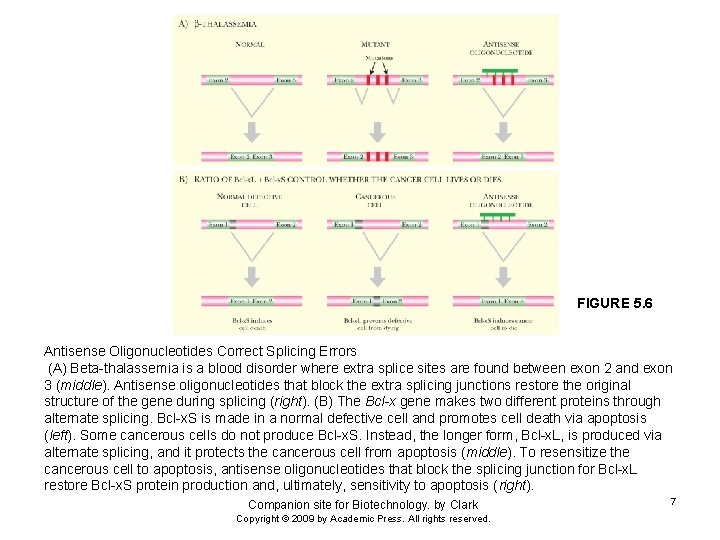

FIGURE 5. 6 Antisense Oligonucleotides Correct Splicing Errors (A) Beta-thalassemia is a blood disorder where extra splice sites are found between exon 2 and exon 3 (middle). Antisense oligonucleotides that block the extra splicing junctions restore the original structure of the gene during splicing (right). (B) The Bcl-x gene makes two different proteins through alternate splicing. Bcl-x. S is made in a normal defective cell and promotes cell death via apoptosis (left). Some cancerous cells do not produce Bcl-x. S. Instead, the longer form, Bcl-x. L, is produced via alternate splicing, and it protects the cancerous cell from apoptosis (middle). To resensitize the cancerous cell to apoptosis, antisense oligonucleotides that block the splicing junction for Bcl-x. L restore Bcl-x. S protein production and, ultimately, sensitivity to apoptosis (right). Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 7

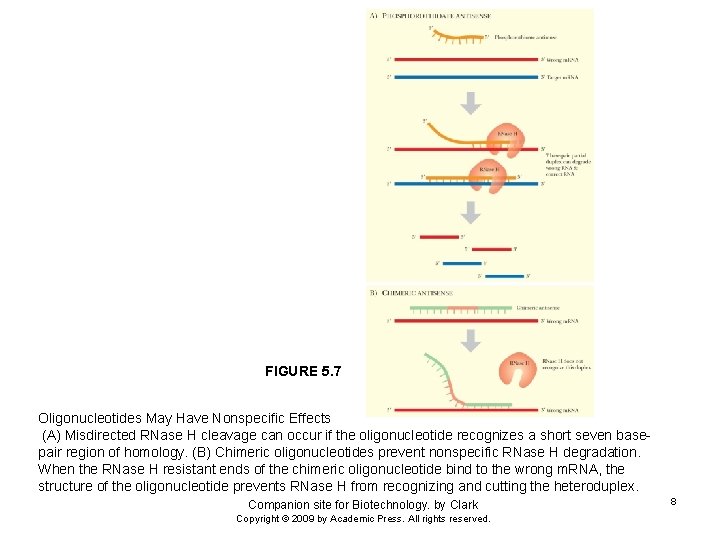

FIGURE 5. 7 Oligonucleotides May Have Nonspecific Effects (A) Misdirected RNase H cleavage can occur if the oligonucleotide recognizes a short seven basepair region of homology. (B) Chimeric oligonucleotides prevent nonspecific RNase H degradation. When the RNase H resistant ends of the chimeric oligonucleotide bind to the wrong m. RNA, the structure of the oligonucleotide prevents RNase H from recognizing and cutting the heteroduplex. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 8

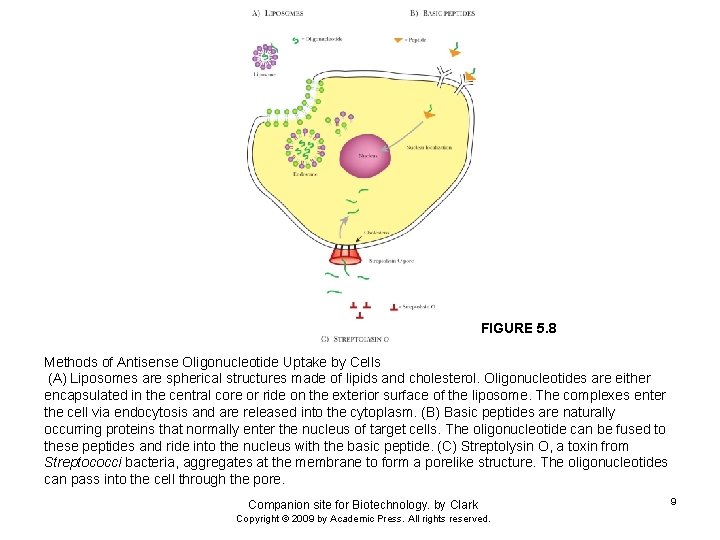

FIGURE 5. 8 Methods of Antisense Oligonucleotide Uptake by Cells (A) Liposomes are spherical structures made of lipids and cholesterol. Oligonucleotides are either encapsulated in the central core or ride on the exterior surface of the liposome. The complexes enter the cell via endocytosis and are released into the cytoplasm. (B) Basic peptides are naturally occurring proteins that normally enter the nucleus of target cells. The oligonucleotide can be fused to these peptides and ride into the nucleus with the basic peptide. (C) Streptolysin O, a toxin from Streptococci bacteria, aggregates at the membrane to form a porelike structure. The oligonucleotides can pass into the cell through the pore. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 9

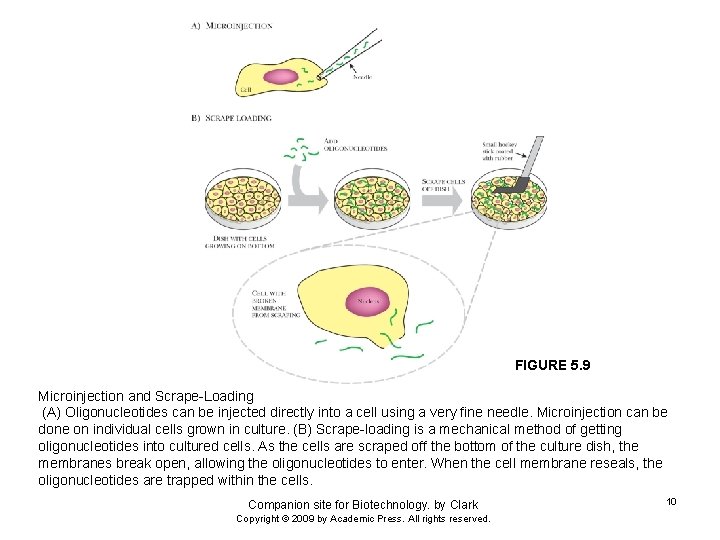

FIGURE 5. 9 Microinjection and Scrape-Loading (A) Oligonucleotides can be injected directly into a cell using a very fine needle. Microinjection can be done on individual cells grown in culture. (B) Scrape-loading is a mechanical method of getting oligonucleotides into cultured cells. As the cells are scraped off the bottom of the culture dish, the membranes break open, allowing the oligonucleotides to enter. When the cell membrane reseals, the oligonucleotides are trapped within the cells. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 10

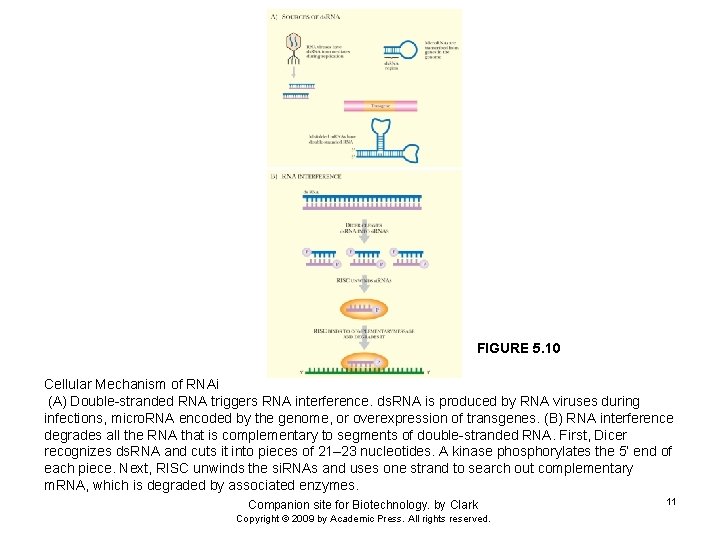

FIGURE 5. 10 Cellular Mechanism of RNAi (A) Double-stranded RNA triggers RNA interference. ds. RNA is produced by RNA viruses during infections, micro. RNA encoded by the genome, or overexpression of transgenes. (B) RNA interference degrades all the RNA that is complementary to segments of double-stranded RNA. First, Dicer recognizes ds. RNA and cuts it into pieces of 21– 23 nucleotides. A kinase phosphorylates the 5’ end of each piece. Next, RISC unwinds the si. RNAs and uses one strand to search out complementary m. RNA, which is degraded by associated enzymes. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 11

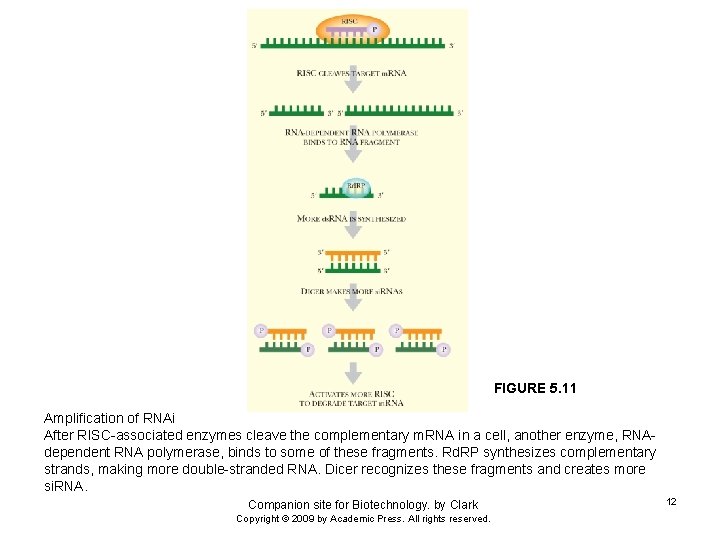

FIGURE 5. 11 Amplification of RNAi After RISC-associated enzymes cleave the complementary m. RNA in a cell, another enzyme, RNAdependent RNA polymerase, binds to some of these fragments. Rd. RP synthesizes complementary strands, making more double-stranded RNA. Dicer recognizes these fragments and creates more si. RNA. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 12

FIGURE 5. 12 Heterochromatin Formation by RNAi The RISC complex containing single-stranded si. RNA can also recognize and bind to complementary DNA sequences. When RISC associates with a repetitive DNA element, various histone modifying enzymes and silencing complexes are activated to turn that region of DNA into heterochromatin. Once this is done, the region is no longer transcribed into m. RNA. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 13

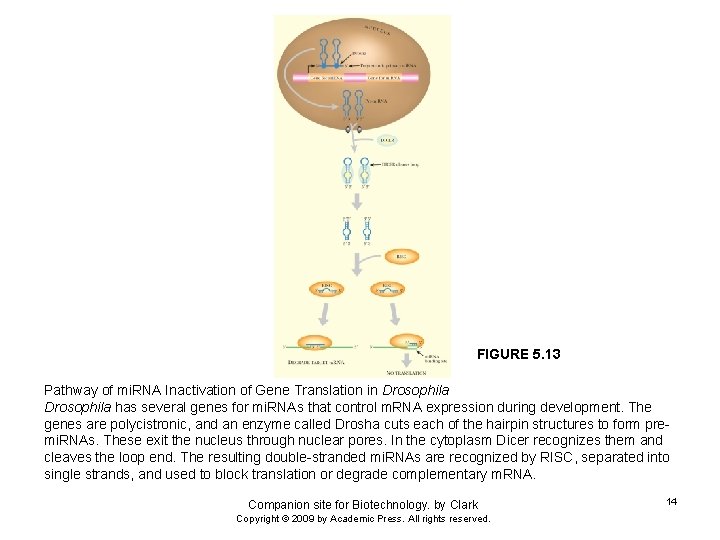

FIGURE 5. 13 Pathway of mi. RNA Inactivation of Gene Translation in Drosophila has several genes for mi. RNAs that control m. RNA expression during development. The genes are polycistronic, and an enzyme called Drosha cuts each of the hairpin structures to form premi. RNAs. These exit the nucleus through nuclear pores. In the cytoplasm Dicer recognizes them and cleaves the loop end. The resulting double-stranded mi. RNAs are recognized by RISC, separated into single strands, and used to block translation or degrade complementary m. RNA. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 14

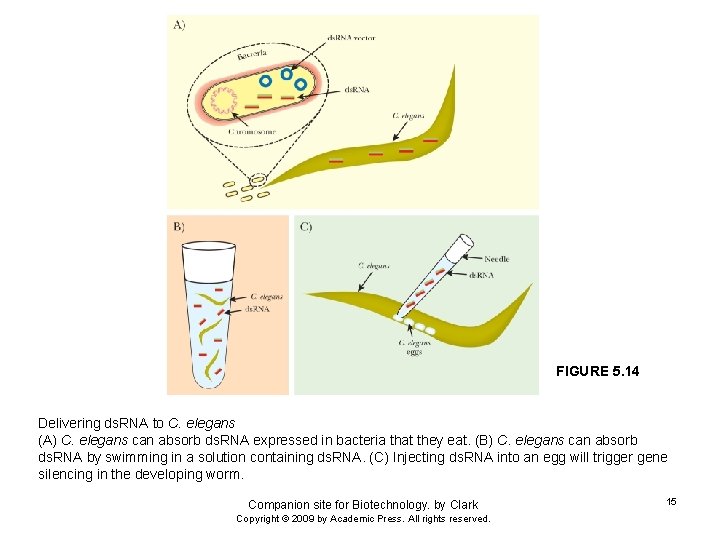

FIGURE 5. 14 Delivering ds. RNA to C. elegans (A) C. elegans can absorb ds. RNA expressed in bacteria that they eat. (B) C. elegans can absorb ds. RNA by swimming in a solution containing ds. RNA. (C) Injecting ds. RNA into an egg will trigger gene silencing in the developing worm. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 15

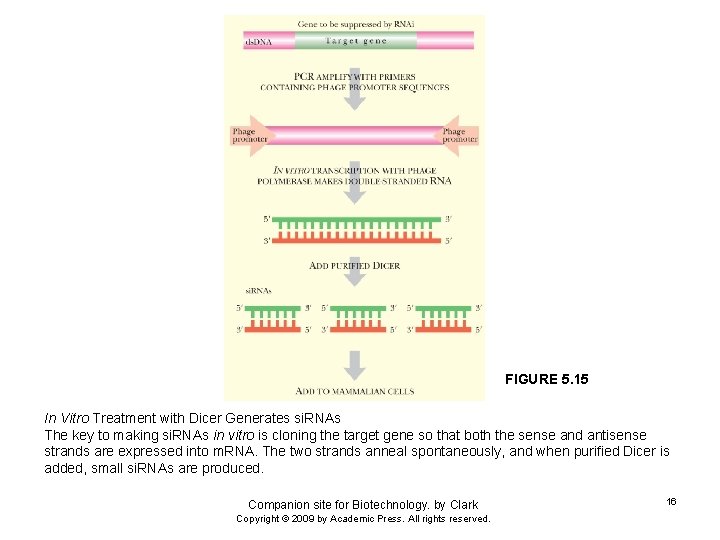

FIGURE 5. 15 In Vitro Treatment with Dicer Generates si. RNAs The key to making si. RNAs in vitro is cloning the target gene so that both the sense and antisense strands are expressed into m. RNA. The two strands anneal spontaneously, and when purified Dicer is added, small si. RNAs are produced. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 16

FIGURE 5. 16 Design of sh. RNA Expression Vectors to Activate RNAi Vectors can be designed to express different sh. RNA molecules. This retrovirus-based vector has two complementary sequences about 20 nucleotides in length that form a stem, separated by a loop region. When the vector is transformed into a cell, the sh. RNA is transcribed and activates gene silencing. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 17

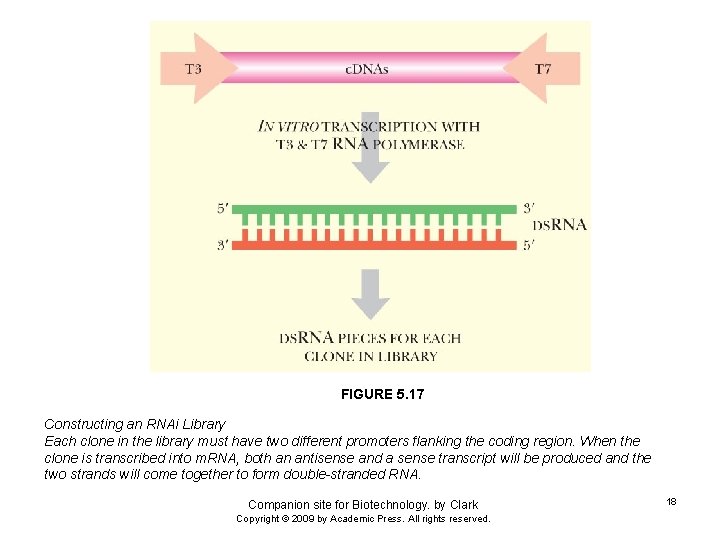

FIGURE 5. 17 Constructing an RNAi Library Each clone in the library must have two different promoters flanking the coding region. When the clone is transcribed into m. RNA, both an antisense and a sense transcript will be produced and the two strands will come together to form double-stranded RNA. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 18

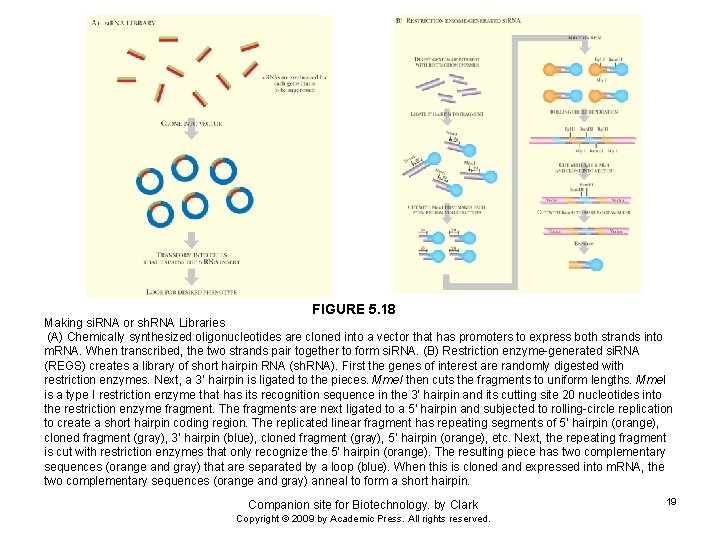

FIGURE 5. 18 Making si. RNA or sh. RNA Libraries (A) Chemically synthesized oligonucleotides are cloned into a vector that has promoters to express both strands into m. RNA. When transcribed, the two strands pair together to form si. RNA. (B) Restriction enzyme-generated si. RNA (REGS) creates a library of short hairpin RNA (sh. RNA). First the genes of interest are randomly digested with restriction enzymes. Next, a 3’ hairpin is ligated to the pieces. Mme. I then cuts the fragments to uniform lengths. Mme. I is a type I restriction enzyme that has its recognition sequence in the 3’ hairpin and its cutting site 20 nucleotides into the restriction enzyme fragment. The fragments are next ligated to a 5’ hairpin and subjected to rolling-circle replication to create a short hairpin coding region. The replicated linear fragment has repeating segments of 5’ hairpin (orange), cloned fragment (gray), 3’ hairpin (blue), cloned fragment (gray), 5’ hairpin (orange), etc. Next, the repeating fragment is cut with restriction enzymes that only recognize the 5’ hairpin (orange). The resulting piece has two complementary sequences (orange and gray) that are separated by a loop (blue). When this is cloned and expressed into m. RNA, the two complementary sequences (orange and gray) anneal to form a short hairpin. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 19

FIGURE 5. 19 Multiwell Plate Assays and Live Cell Microarrays (A) Short-interfering RNA and short-hairpin RNA libraries can assess the function of mammalian proteins. If the library is transfected into mammalian cells, each cell can be assessed for different physical phenotypes, such as loss of adherence, mitotic arrest, or changed cell shape. The sh. RNA or si. RNA that causes an interesting phenotype can be isolated and sequenced to identify the protein that was suppressed. (B) Rather than transforming cells, the si. RNA or sh. RNA can be spotted onto microscope slides. As cells grow and divide on the slide, the si. RNAs are taken up by the cells and initiate RNAi. The cells over each spot are assessed for a particular phenotype. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 20

A brief History 1982: Self-splicing in Tetrahymena pre-r. RNA (group I intron) Kruger et al, and Cech, Cell 31, 147 -157 (1982) 1983: RNAse P is a ribozyme Guerrier-Takada et al, and Altman, Cell, 35, 849 -857 (1983)

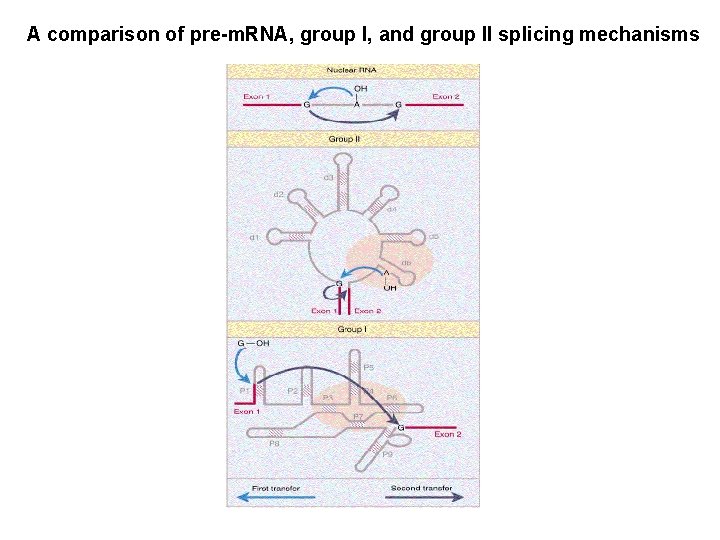

Classes of Ribozymes 1. Group I tetrahymena – Self-splicing – Initiate splicing with a G nucleotide – Uses a phosphoester transfer mechanism – Does not require ATP hydrolysis. 2. Group II self-splicing – Initiate splicing with an internal A – Uses a phosphoester transfer mechanism – Does not require ATP hydrolysis

3. Self-cleaving RNAs encoded by viral genome to resolve the concatameric molecules of the viral genomic RNA produced a. HDV ribozyme b. Hairpin ribozyme c. Hammerhead ribozyme d. VS ribozyme 4. Rnase P

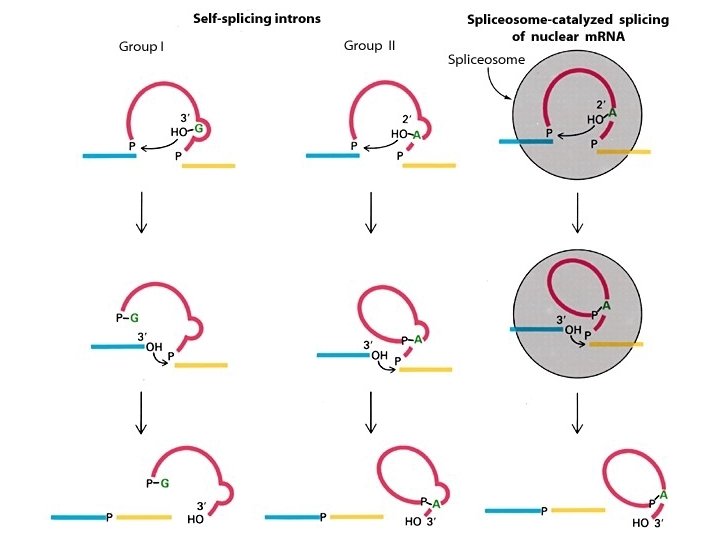

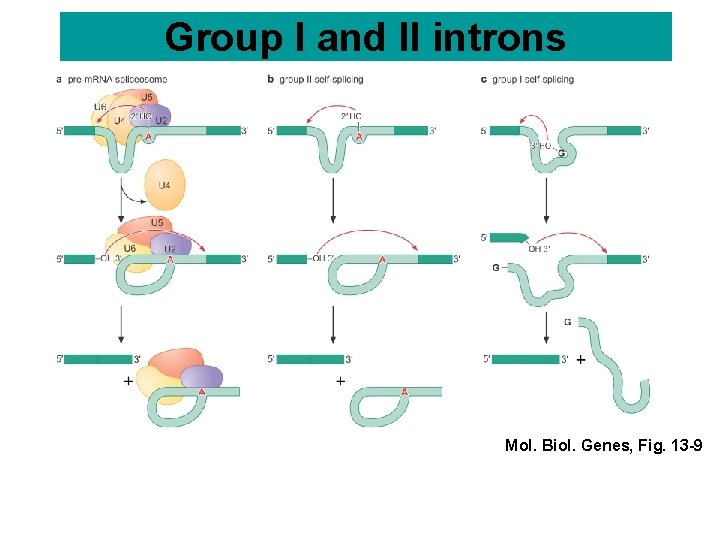

Group I and II introns Mol. Biol. Genes, Fig. 13 -9

A comparison of pre-m. RNA, group I, and group II splicing mechanisms

FIGURE 5. 20 Structure of the Twort Ribozyme (A) Primary and secondary structure of the wild-type intron. The P 1 -P 2 domain is highlighted in red, the P 3 -P 7 region is green, the P 4 -P 6 domain is blue, the P 9 -P 9. 1 region is purple, the P 7. 1 -P 7. 2 subdomain is yellow, and the product oligonucleotide is cyan. Dashed lines indicate key tertiary structure contacts. Nucleotides in italics (P 5 a region) are disordered in the crystal. IGS, internal guide sequence. (B) Ribbon diagram colored as in (A). The backbone ribbon is drawn through the phosphate positions in the backbone. From: Golden, Kim, and Chase (2004). Crystal structure of a phage Twort group I ribozyme-product complex. Reprinted by permission from: Macmillan Publishers Ltd. Nat Struct Mol Biol 12, 82– 89, copyright 2005. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 27

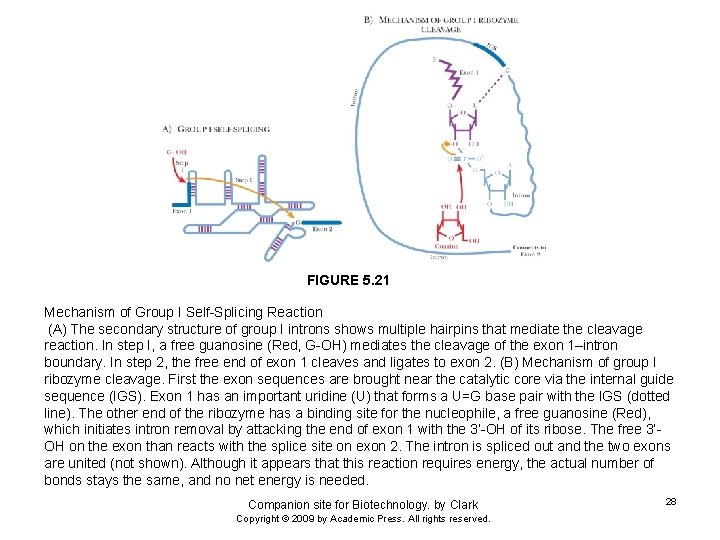

FIGURE 5. 21 Mechanism of Group I Self-Splicing Reaction (A) The secondary structure of group I introns shows multiple hairpins that mediate the cleavage reaction. In step I, a free guanosine (Red, G-OH) mediates the cleavage of the exon 1–intron boundary. In step 2, the free end of exon 1 cleaves and ligates to exon 2. (B) Mechanism of group I ribozyme cleavage. First the exon sequences are brought near the catalytic core via the internal guide sequence (IGS). Exon 1 has an important uridine (U) that forms a U=G base pair with the IGS (dotted line). The other end of the ribozyme has a binding site for the nucleophile, a free guanosine (Red), which initiates intron removal by attacking the end of exon 1 with the 3’-OH of its ribose. The free 3’OH on the exon than reacts with the splice site on exon 2. The intron is spliced out and the two exons are united (not shown). Although it appears that this reaction requires energy, the actual number of bonds stays the same, and no net energy is needed. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 28

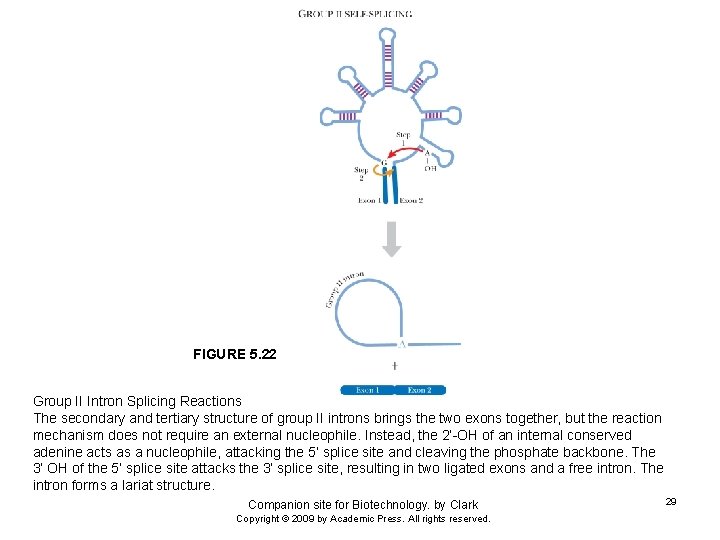

FIGURE 5. 22 Group II Intron Splicing Reactions The secondary and tertiary structure of group II introns brings the two exons together, but the reaction mechanism does not require an external nucleophile. Instead, the 2’-OH of an internal conserved adenine acts as a nucleophile, attacking the 5’ splice site and cleaving the phosphate backbone. The 3’ OH of the 5’ splice site attacks the 3’ splice site, resulting in two ligated exons and a free intron. The intron forms a lariat structure. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 29

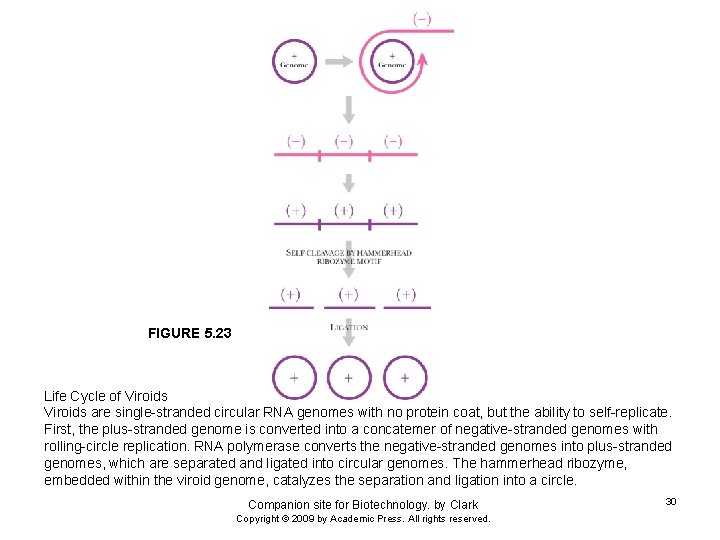

FIGURE 5. 23 Life Cycle of Viroids are single-stranded circular RNA genomes with no protein coat, but the ability to self-replicate. First, the plus-stranded genome is converted into a concatemer of negative-stranded genomes with rolling-circle replication. RNA polymerase converts the negative-stranded genomes into plus-stranded genomes, which are separated and ligated into circular genomes. The hammerhead ribozyme, embedded within the viroid genome, catalyzes the separation and ligation into a circle. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 30

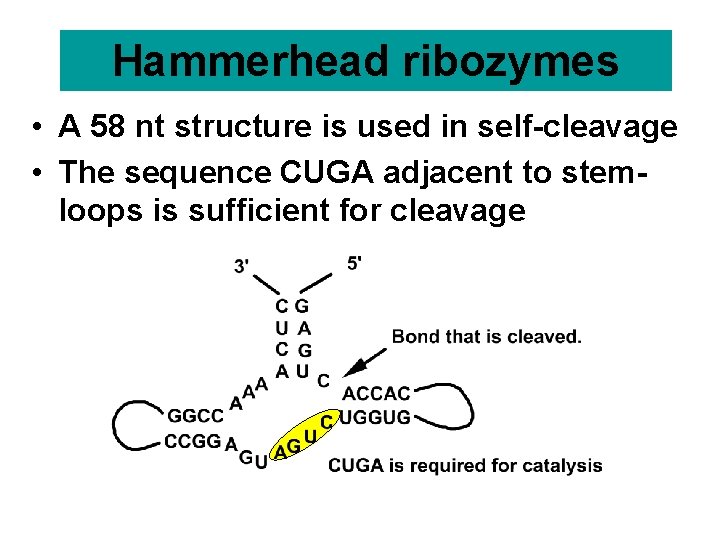

Hammerhead ribozymes • A 58 nt structure is used in self-cleavage • The sequence CUGA adjacent to stemloops is sufficient for cleavage

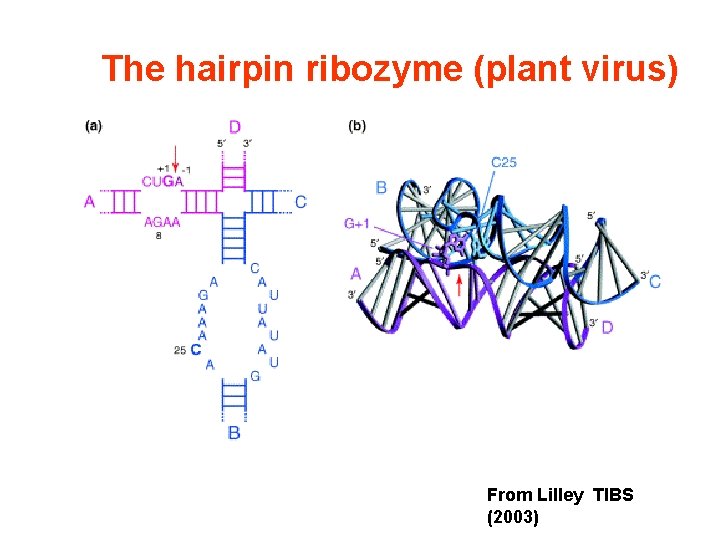

The hairpin ribozyme (plant virus) From Lilley TIBS (2003)

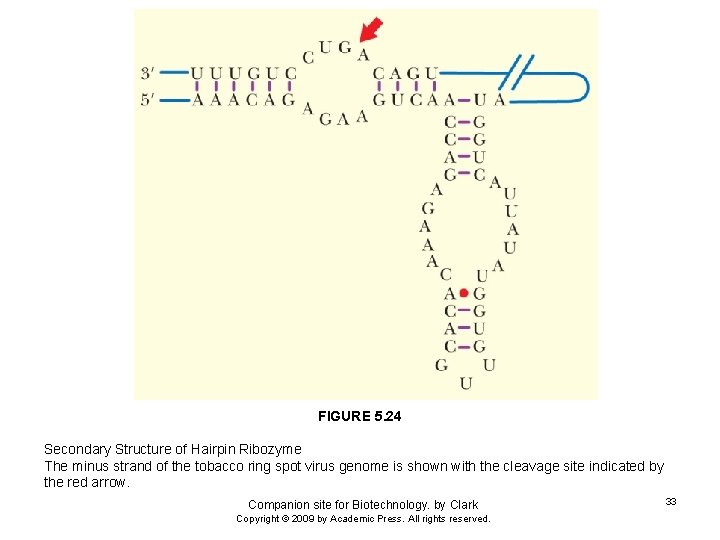

FIGURE 5. 24 Secondary Structure of Hairpin Ribozyme The minus strand of the tobacco ring spot virus genome is shown with the cleavage site indicated by the red arrow. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 33

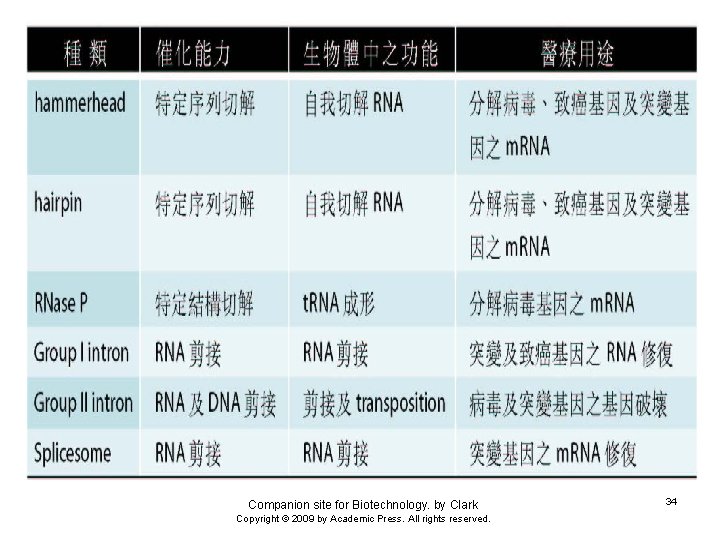

Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 34

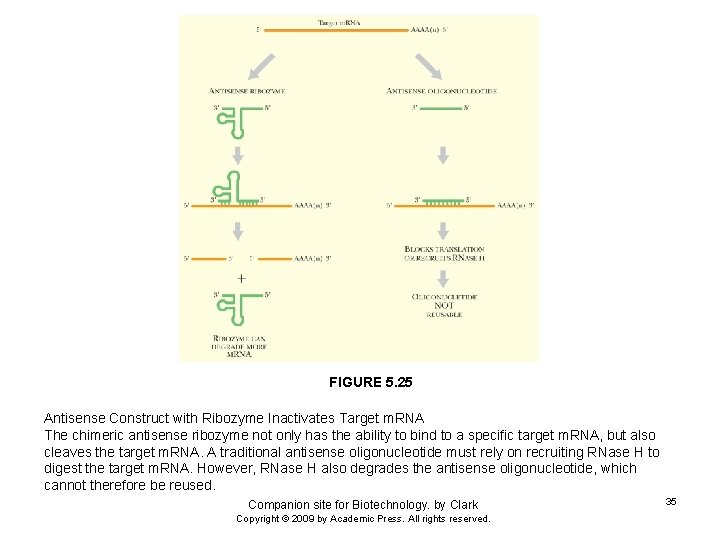

FIGURE 5. 25 Antisense Construct with Ribozyme Inactivates Target m. RNA The chimeric antisense ribozyme not only has the ability to bind to a specific target m. RNA, but also cleaves the target m. RNA. A traditional antisense oligonucleotide must rely on recruiting RNase H to digest the target m. RNA. However, RNase H also degrades the antisense oligonucleotide, which cannot therefore be reused. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 35

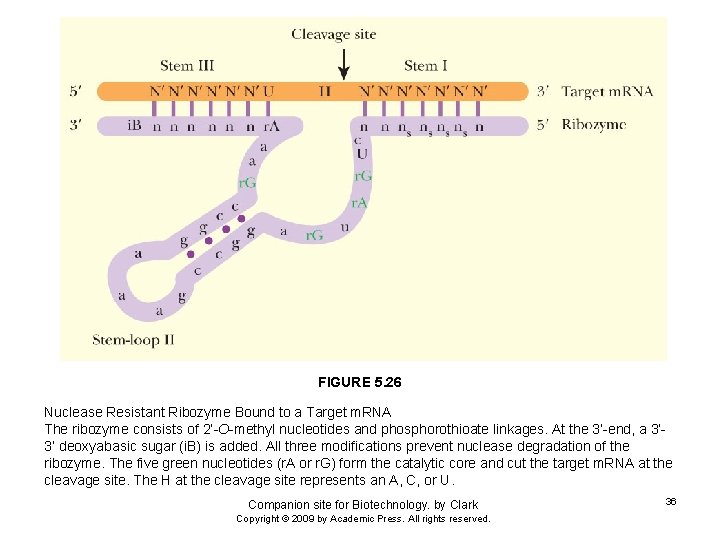

FIGURE 5. 26 Nuclease Resistant Ribozyme Bound to a Target m. RNA The ribozyme consists of 2’-O-methyl nucleotides and phosphorothioate linkages. At the 3’-end, a 3’ 3’ deoxyabasic sugar (i. B) is added. All three modifications prevent nuclease degradation of the ribozyme. The five green nucleotides (r. A or r. G) form the catalytic core and cut the target m. RNA at the cleavage site. The H at the cleavage site represents an A, C, or U. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 36

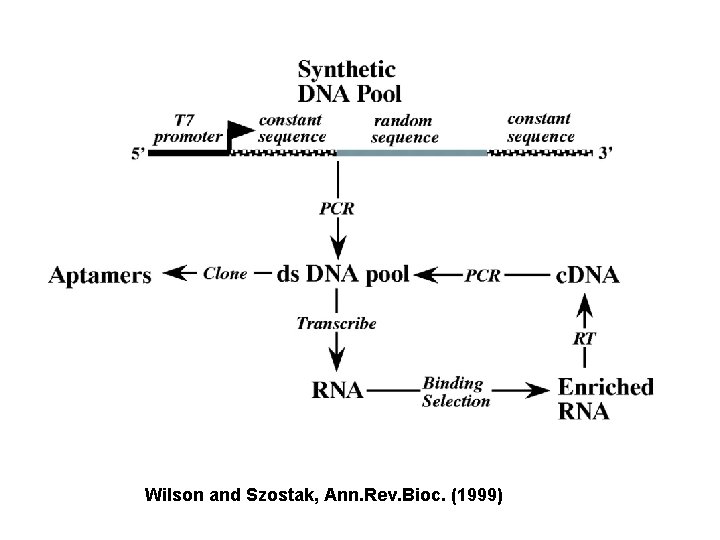

SELEX : Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential enrichment A brief History Ellington and Szostak, Nature (1990) Tuerk and Gold , Science (1990)

Wilson and Szostak, Ann. Rev. Bioc. (1999)

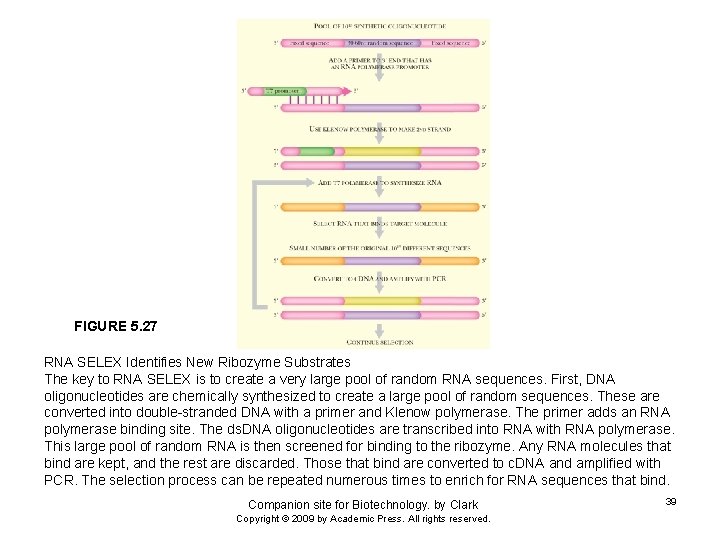

FIGURE 5. 27 RNA SELEX Identifies New Ribozyme Substrates The key to RNA SELEX is to create a very large pool of random RNA sequences. First, DNA oligonucleotides are chemically synthesized to create a large pool of random sequences. These are converted into double-stranded DNA with a primer and Klenow polymerase. The primer adds an RNA polymerase binding site. The ds. DNA oligonucleotides are transcribed into RNA with RNA polymerase. This large pool of random RNA is then screened for binding to the ribozyme. Any RNA molecules that bind are kept, and the rest are discarded. Those that bind are converted to c. DNA and amplified with PCR. The selection process can be repeated numerous times to enrich for RNA sequences that bind. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 39

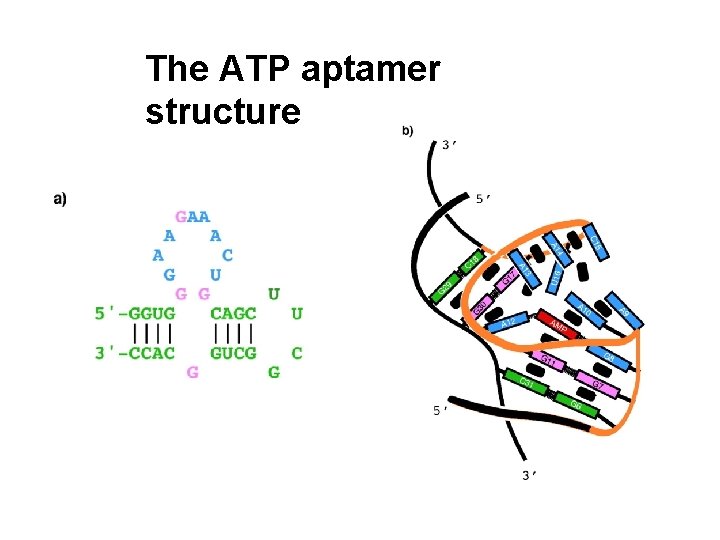

The ATP aptamer structure

- Selection against small molecules - Selection against proteins - Selection of new ribozymes (RNA world

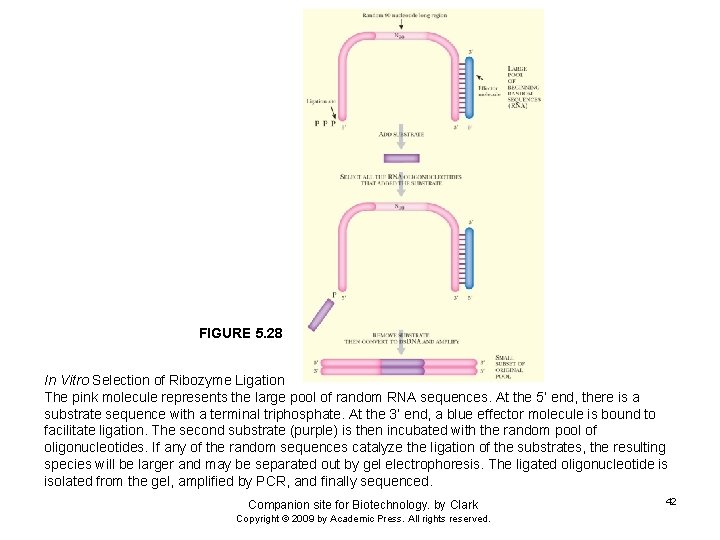

FIGURE 5. 28 In Vitro Selection of Ribozyme Ligation The pink molecule represents the large pool of random RNA sequences. At the 5’ end, there is a substrate sequence with a terminal triphosphate. At the 3’ end, a blue effector molecule is bound to facilitate ligation. The second substrate (purple) is then incubated with the random pool of oligonucleotides. If any of the random sequences catalyze the ligation of the substrates, the resulting species will be larger and may be separated out by gel electrophoresis. The ligated oligonucleotide is isolated from the gel, amplified by PCR, and finally sequenced. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 42

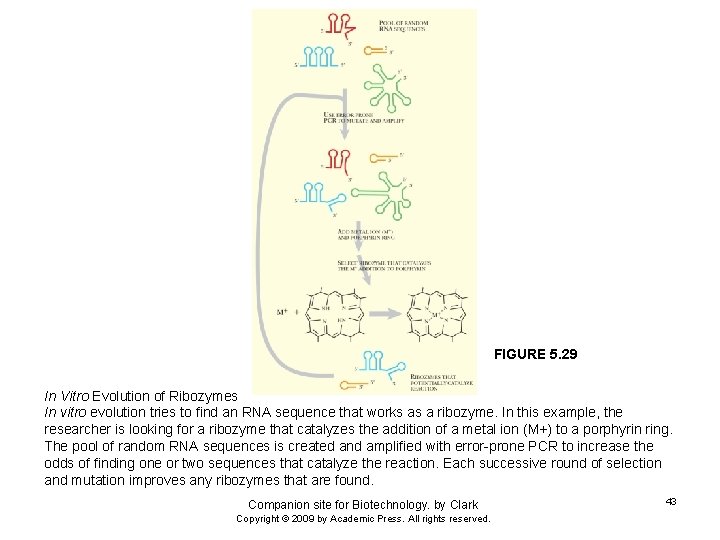

FIGURE 5. 29 In Vitro Evolution of Ribozymes In vitro evolution tries to find an RNA sequence that works as a ribozyme. In this example, the researcher is looking for a ribozyme that catalyzes the addition of a metal ion (M+) to a porphyrin ring. The pool of random RNA sequences is created and amplified with error-prone PCR to increase the odds of finding one or two sequences that catalyze the reaction. Each successive round of selection and mutation improves any ribozymes that are found. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 43

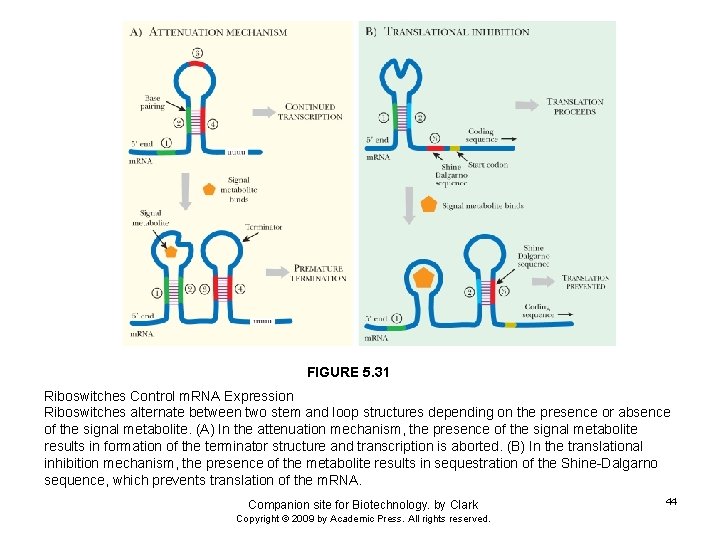

FIGURE 5. 31 Riboswitches Control m. RNA Expression Riboswitches alternate between two stem and loop structures depending on the presence or absence of the signal metabolite. (A) In the attenuation mechanism, the presence of the signal metabolite results in formation of the terminator structure and transcription is aborted. (B) In the translational inhibition mechanism, the presence of the metabolite results in sequestration of the Shine-Dalgarno sequence, which prevents translation of the m. RNA. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 44

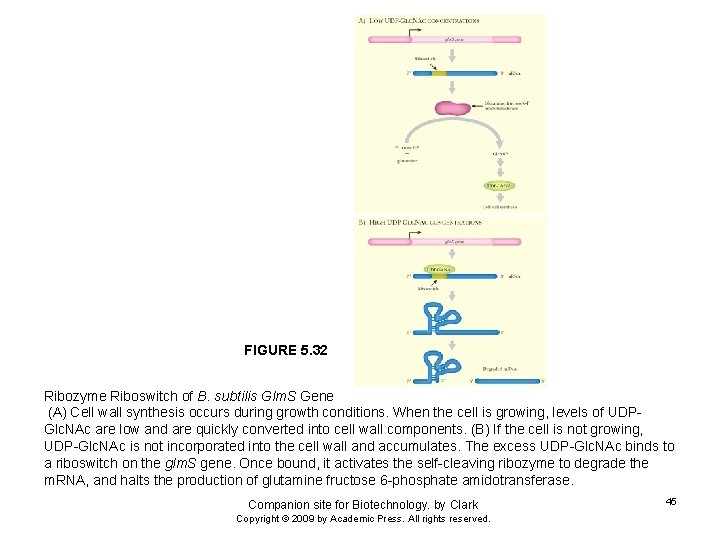

FIGURE 5. 32 Ribozyme Riboswitch of B. subtilis Glm. S Gene (A) Cell wall synthesis occurs during growth conditions. When the cell is growing, levels of UDPGlc. NAc are low and are quickly converted into cell wall components. (B) If the cell is not growing, UDP-Glc. NAc is not incorporated into the cell wall and accumulates. The excess UDP-Glc. NAc binds to a riboswitch on the glm. S gene. Once bound, it activates the self-cleaving ribozyme to degrade the m. RNA, and halts the production of glutamine fructose 6 -phosphate amidotransferase. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 45

FIGURE 5. 33 Designing Allosteric Ribozymes (A) Modular design of a ribozyme. The ribozyme has three different domains joined together. The substrate domain (light green background) base-pairs with the ribosyme domain (light purple background), and the aptamer domain binds the allosteric effector (ATP in this example). (B) In vitro selection scheme to identify ribozymes that are active only when bound to an effector (i. e. , are allosteric). First, all ribozymes that catalyze substrate cleavage without an effector are removed. If the substrate is cleaved without the effector, the ribozyme will move faster during electrophoresis. Only the uncleaved ribozyme/substrate band is isolated from the gel. Next, the ribozymes are mixed with an effector molecule. This time, the ribozymes that cleave the substrate are isolated. Repeated cycles of isolation will identify a ribozyme that works only with the effector. Companion site for Biotechnology. by Clark Copyright © 2009 by Academic Press. All rights reserved. 46

- Slides: 46