Chapter 5 Process Scheduling Objectives n To introduce

Chapter 5: Process Scheduling

Objectives n To introduce CPU scheduling n To describe various CPU-scheduling algorithms n To discuss evaluation criteria for selecting the CPU- scheduling algorithm for a particular system Operating System Principles 5. 2 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

Chapter 5: Process Scheduling n Basic Concepts n Scheduling Criteria n Scheduling Algorithms n Multiple-Processor Scheduling n Operating Systems Examples (Linux) n Algorithm Evaluation Skip: 5. 4, 5. 5. 4 - 5. 6. 2 Operating System Principles 5. 3 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

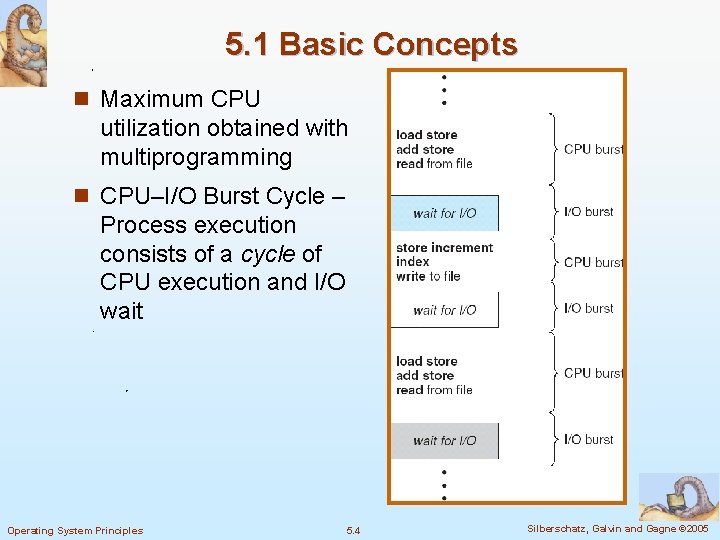

5. 1 Basic Concepts n Maximum CPU utilization obtained with multiprogramming n CPU–I/O Burst Cycle – Process execution consists of a cycle of CPU execution and I/O wait Operating System Principles 5. 4 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

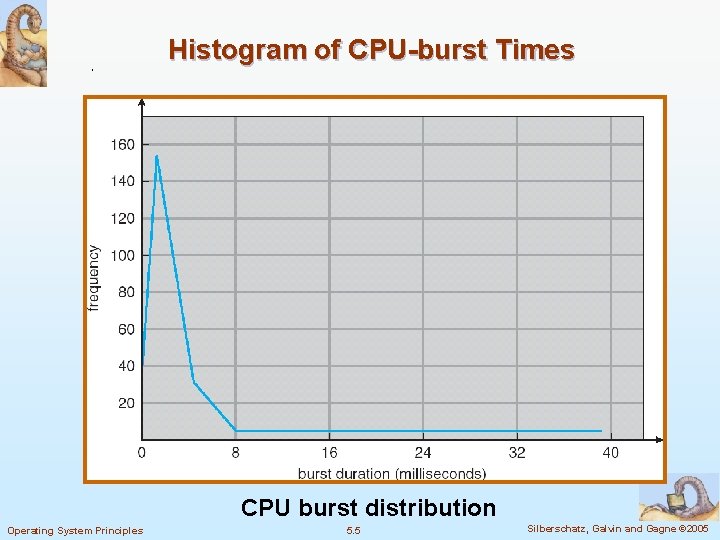

Histogram of CPU-burst Times CPU burst distribution Operating System Principles 5. 5 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

CPU Scheduler n Selects from among the processes in memory that are ready to execute, and allocates the CPU to one of them n CPU scheduling decisions may take place when a process: 1. Switches from running to waiting state 2. Switches from running to ready state 3. Switches from waiting to ready 4. Terminates n Scheduling only under 1 and 4 is nonpreemptive n All other scheduling is preemptive Operating System Principles 5. 6 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

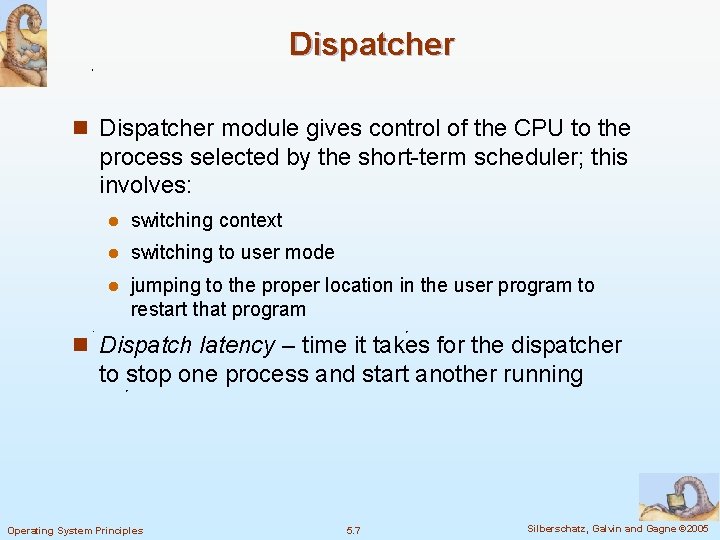

Dispatcher n Dispatcher module gives control of the CPU to the process selected by the short-term scheduler; this involves: l switching context l switching to user mode l jumping to the proper location in the user program to restart that program n Dispatch latency – time it takes for the dispatcher to stop one process and start another running Operating System Principles 5. 7 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

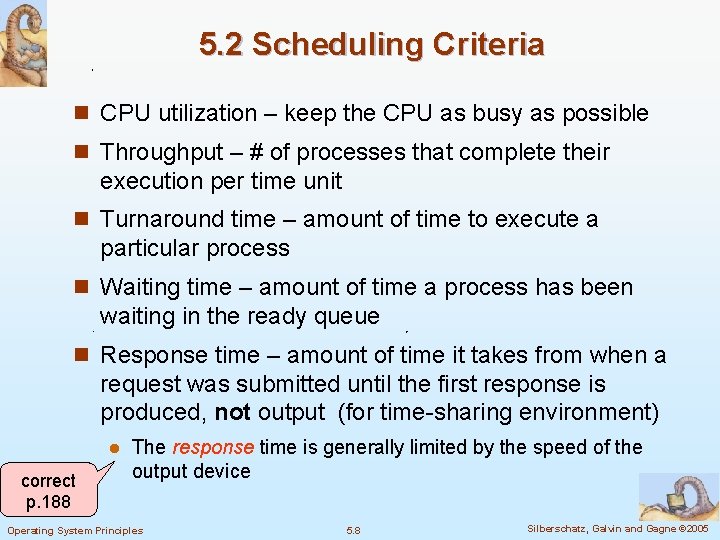

5. 2 Scheduling Criteria n CPU utilization – keep the CPU as busy as possible n Throughput – # of processes that complete their execution per time unit n Turnaround time – amount of time to execute a particular process n Waiting time – amount of time a process has been waiting in the ready queue n Response time – amount of time it takes from when a request was submitted until the first response is produced, not output (for time-sharing environment) l correct p. 188 The response time is generally limited by the speed of the output device Operating System Principles 5. 8 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

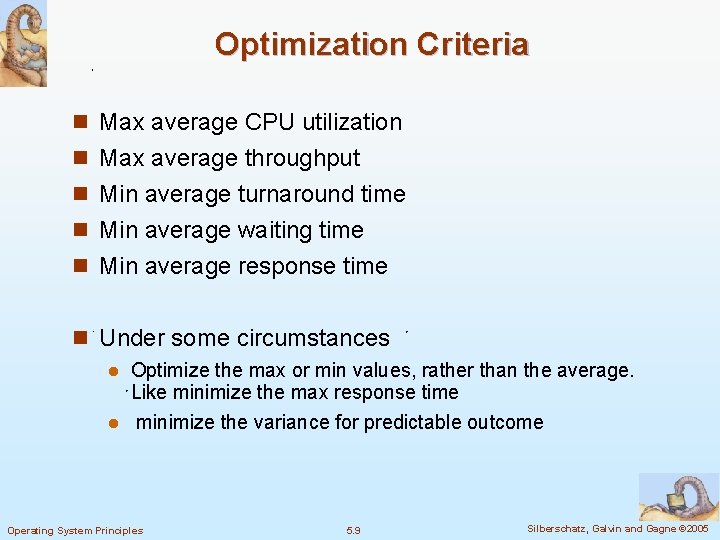

Optimization Criteria n Max average CPU utilization n Max average throughput n Min average turnaround time n Min average waiting time n Min average response time n Under some circumstances Optimize the max or min values, rather than the average. Like minimize the max response time l minimize the variance for predictable outcome l Operating System Principles 5. 9 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

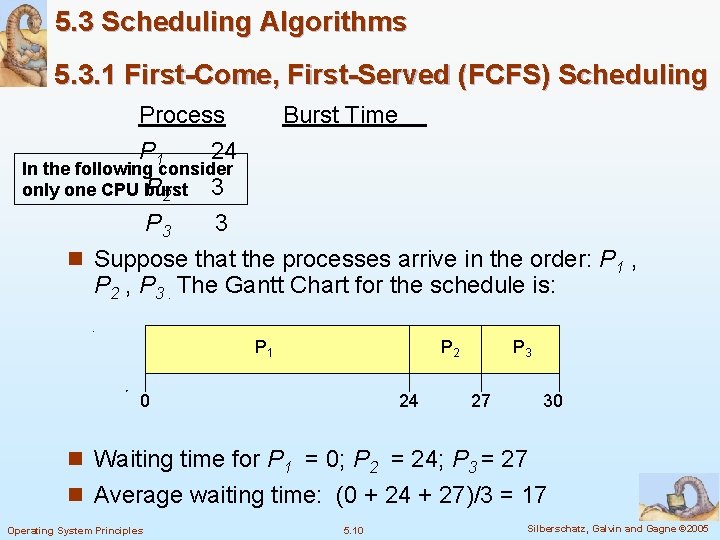

5. 3 Scheduling Algorithms 5. 3. 1 First-Come, First-Served (FCFS) Scheduling Process Burst Time P 1 24 In the following consider P 2 3 only one CPU burst P 3 3 n Suppose that the processes arrive in the order: P 1 , P 2 , P 3. The Gantt Chart for the schedule is: P 1 P 2 0 24 P 3 27 30 n Waiting time for P 1 = 0; P 2 = 24; P 3 = 27 n Average waiting time: (0 + 24 + 27)/3 = 17 Operating System Principles 5. 10 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

FCFS Scheduling (Cont. ) Nonpreemptive Suppose that the processes arrive in the order P 2 , P 3 , P 1 n The Gantt chart for the schedule is: P 2 0 P 3 3 P 1 6 30 n Waiting time for P 1 = 6; P 2 = 0; P 3 = 3 n Average waiting time: (6 + 0 + 3)/3 = 3 n Much better than previous case n Convoy effect short process behind long process Operating System Principles 5. 11 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

5. 3. 2 Shortest-Job-First (SJR) Scheduling n Associate with each process the length of its next CPU burst. Use these lengths to schedule the process with the shortest time n Two schemes: l nonpreemptive – once CPU given to the process it cannot be preempted until completes its CPU burst l preemptive – if a new process arrives with CPU burst length less than remaining time of current executing process, preempt. This scheme is know as the Shortest-Remaining-Time-First (SRTF) n SJF is optimal – gives minimum average waiting time for a given set of processes Operating System Principles 5. 12 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

Example of Non-Preemptive SJF Process Arrival Time Burst Time P 1 0. 0 7 P 2 2. 0 4 P 3 4. 0 1 P 4 5. 0 4 n SJF (non-preemptive) P 1 0 3 P 3 7 P 2 8 P 4 12 16 n Average waiting time = (0 + 6 + 3 + 7)/4 = 4 Operating System Principles 5. 13 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

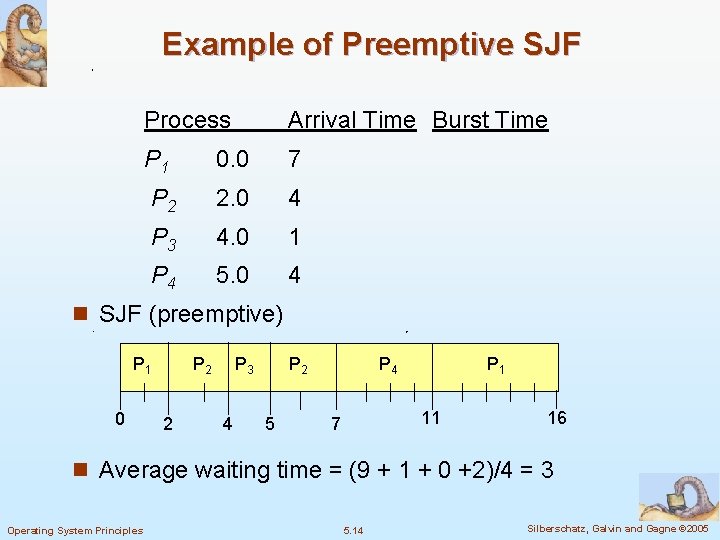

Example of Preemptive SJF Process Arrival Time Burst Time P 1 0. 0 7 P 2 2. 0 4 P 3 4. 0 1 P 4 5. 0 4 n SJF (preemptive) P 1 0 P 2 2 P 3 4 P 2 5 P 4 P 1 11 7 16 n Average waiting time = (9 + 1 + 0 +2)/4 = 3 Operating System Principles 5. 14 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

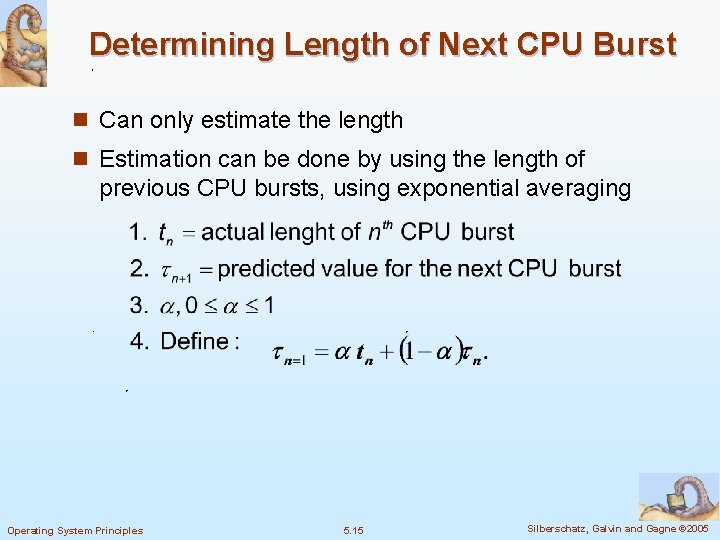

Determining Length of Next CPU Burst n Can only estimate the length n Estimation can be done by using the length of previous CPU bursts, using exponential averaging Operating System Principles 5. 15 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

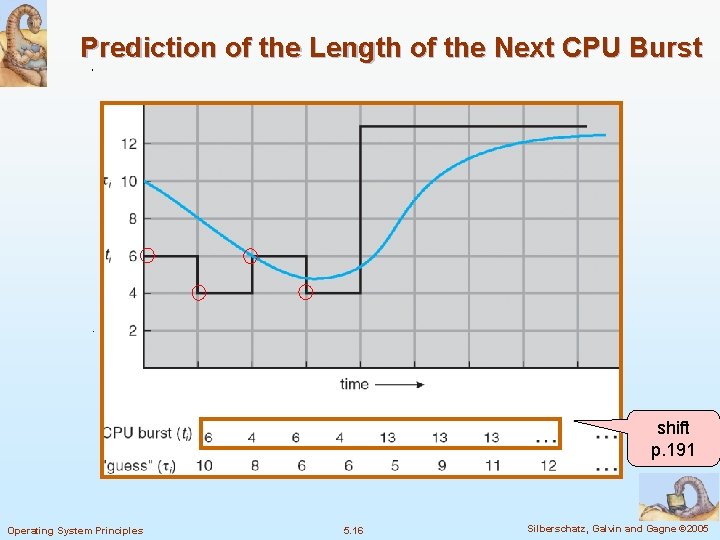

Prediction of the Length of the Next CPU Burst shift p. 191 Operating System Principles 5. 16 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

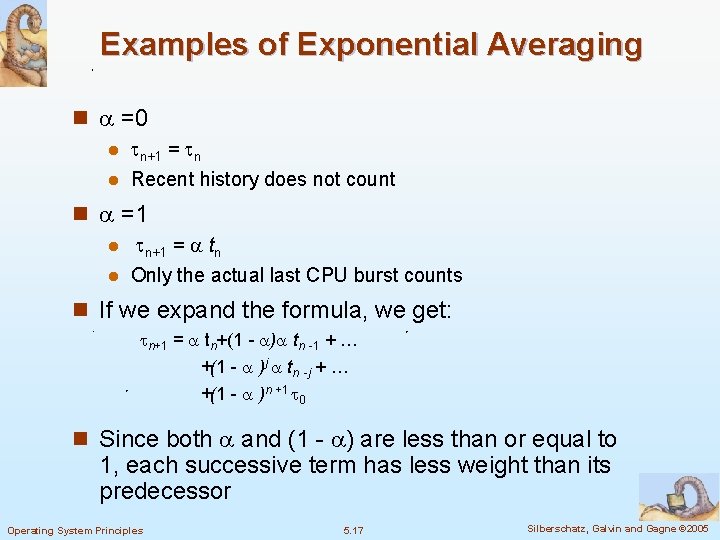

Examples of Exponential Averaging n =0 n+1 = n l Recent history does not count l n =1 n+1 = tn l Only the actual last CPU burst counts l n If we expand the formula, we get: n+1 = tn+(1 - ) tn -1 + … +(1 - )j tn -j + … +(1 - )n +1 0 n Since both and (1 - ) are less than or equal to 1, each successive term has less weight than its predecessor Operating System Principles 5. 17 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

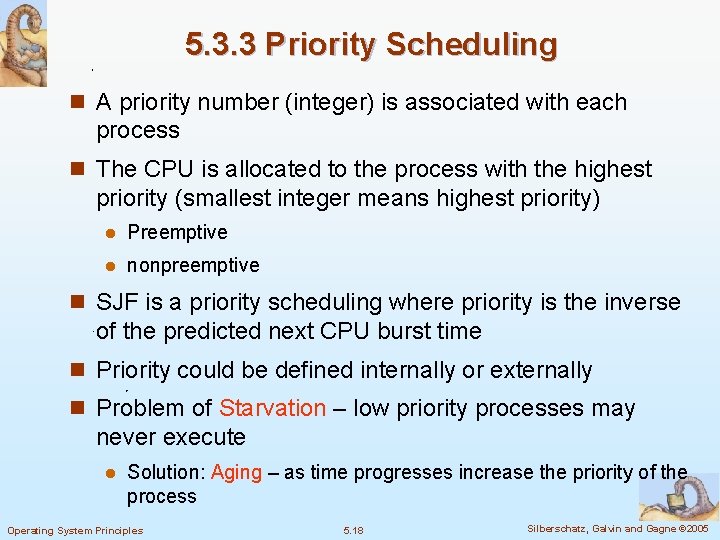

5. 3. 3 Priority Scheduling n A priority number (integer) is associated with each process n The CPU is allocated to the process with the highest priority (smallest integer means highest priority) l Preemptive l nonpreemptive n SJF is a priority scheduling where priority is the inverse of the predicted next CPU burst time n Priority could be defined internally or externally n Problem of Starvation – low priority processes may never execute l Solution: Aging – as time progresses increase the priority of the process Operating System Principles 5. 18 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

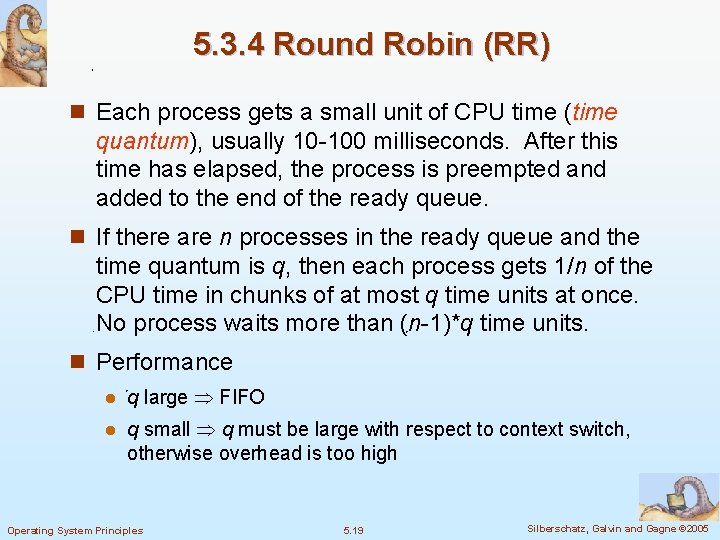

5. 3. 4 Round Robin (RR) n Each process gets a small unit of CPU time (time quantum), usually 10 -100 milliseconds. After this time has elapsed, the process is preempted and added to the end of the ready queue. n If there are n processes in the ready queue and the time quantum is q, then each process gets 1/n of the CPU time in chunks of at most q time units at once. No process waits more than (n-1)*q time units. n Performance l q large FIFO l q small q must be large with respect to context switch, otherwise overhead is too high Operating System Principles 5. 19 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

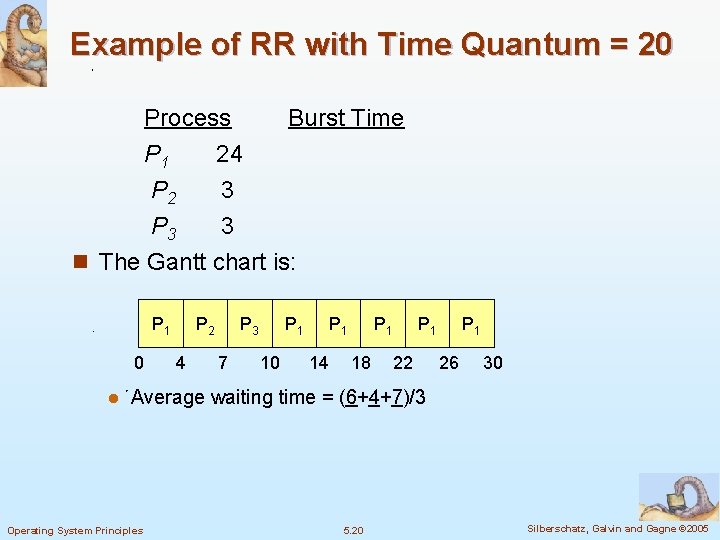

Example of RR with Time Quantum = 20 Process Burst Time P 1 24 P 2 3 P 3 3 n The Gantt chart is: P 1 0 l P 2 4 P 3 7 P 1 10 P 1 14 P 1 18 P 1 22 P 1 26 30 Average waiting time = (6+4+7)/3 Operating System Principles 5. 20 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

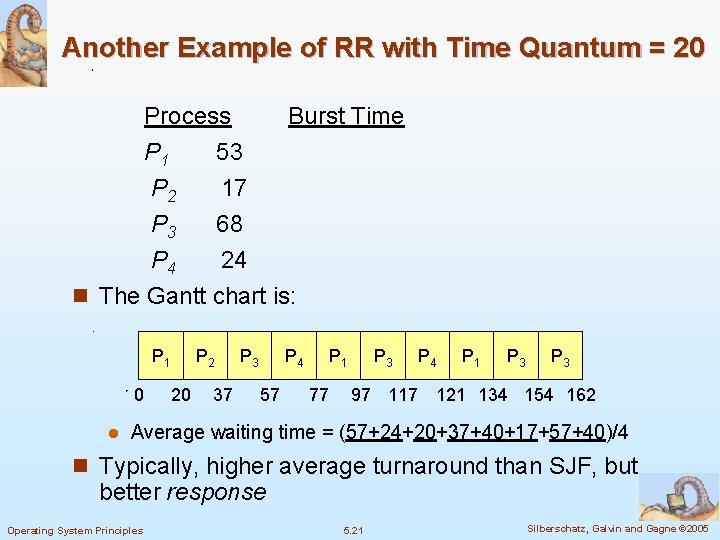

Another Example of RR with Time Quantum = 20 Process Burst Time P 1 53 P 2 17 P 3 68 P 4 24 n The Gantt chart is: P 1 0 l P 2 20 37 P 3 P 4 57 P 1 77 P 3 P 4 P 1 P 3 97 117 121 134 154 162 Average waiting time = (57+24+20+37+40+17+57+40)/4 n Typically, higher average turnaround than SJF, but better response Operating System Principles 5. 21 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

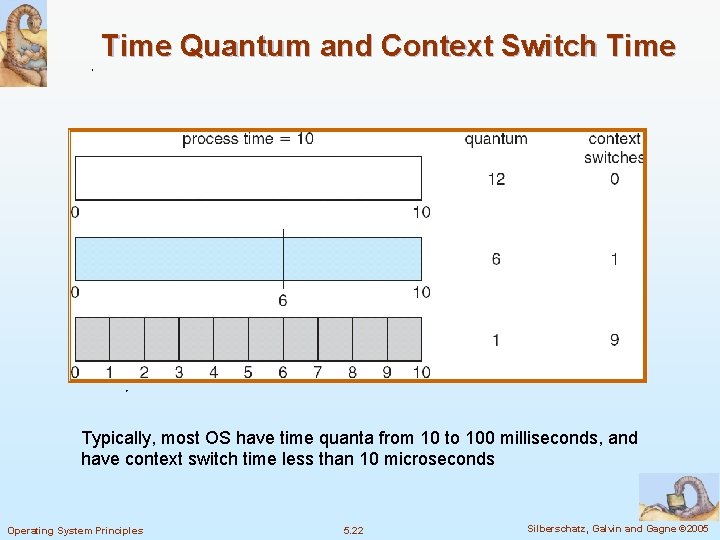

Time Quantum and Context Switch Time Typically, most OS have time quanta from 10 to 100 milliseconds, and have context switch time less than 10 microseconds Operating System Principles 5. 22 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

Turnaround Time Varies With The Time Quantum • The average turnaround time does not necessary improve as the time-quantum size increases Operating System Principles 5. 23 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

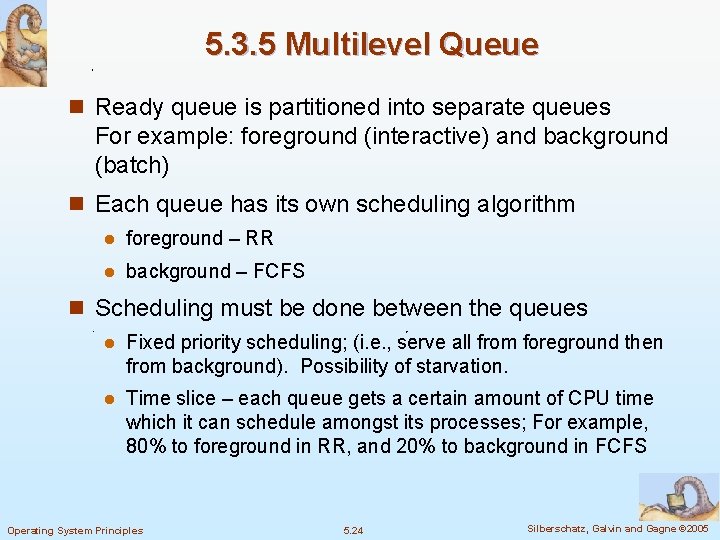

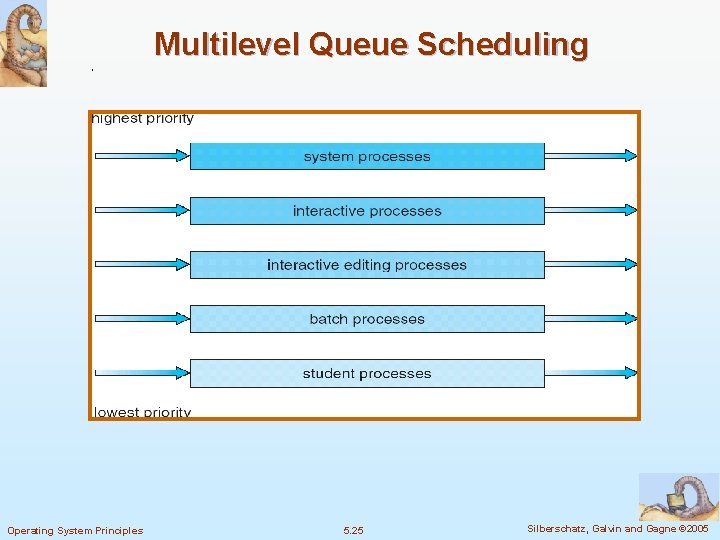

5. 3. 5 Multilevel Queue n Ready queue is partitioned into separate queues For example: foreground (interactive) and background (batch) n Each queue has its own scheduling algorithm l foreground – RR l background – FCFS n Scheduling must be done between the queues l Fixed priority scheduling; (i. e. , serve all from foreground then from background). Possibility of starvation. l Time slice – each queue gets a certain amount of CPU time which it can schedule amongst its processes; For example, 80% to foreground in RR, and 20% to background in FCFS Operating System Principles 5. 24 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

Multilevel Queue Scheduling Operating System Principles 5. 25 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

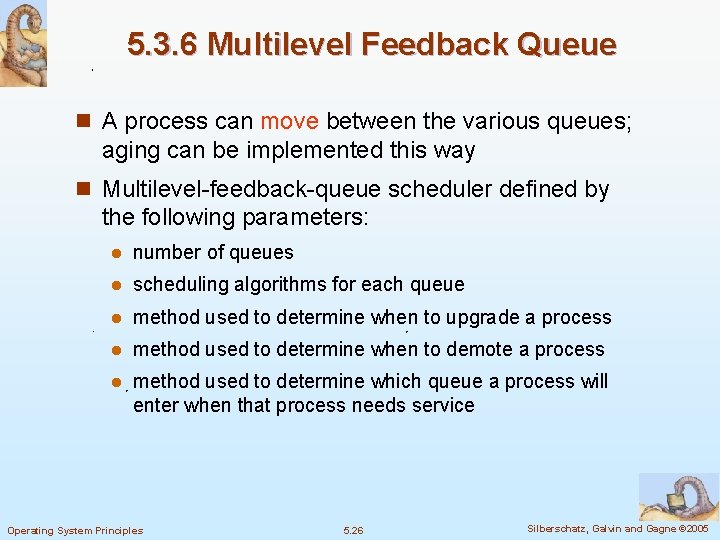

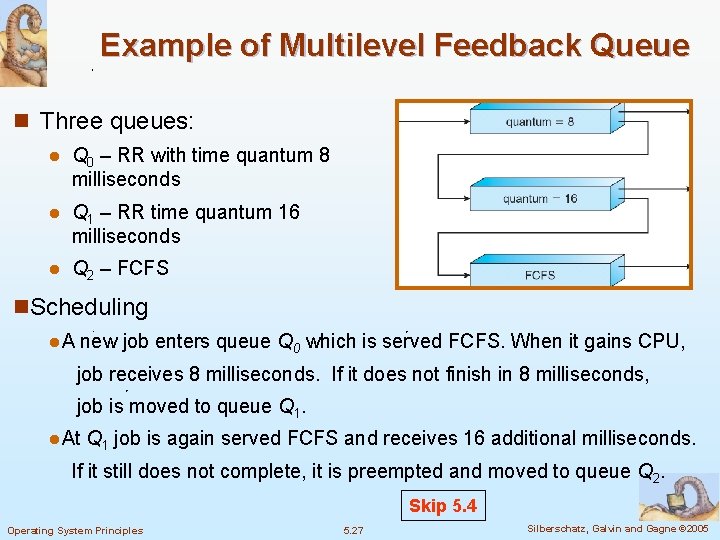

5. 3. 6 Multilevel Feedback Queue n A process can move between the various queues; aging can be implemented this way n Multilevel-feedback-queue scheduler defined by the following parameters: l number of queues l scheduling algorithms for each queue l method used to determine when to upgrade a process l method used to determine when to demote a process l method used to determine which queue a process will enter when that process needs service Operating System Principles 5. 26 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

Example of Multilevel Feedback Queue n Three queues: l Q 0 – RR with time quantum 8 milliseconds l Q 1 – RR time quantum 16 milliseconds l Q 2 – FCFS n. Scheduling l. A new job enters queue Q 0 which is served FCFS. When it gains CPU, job receives 8 milliseconds. If it does not finish in 8 milliseconds, job is moved to queue Q 1. l. At Q 1 job is again served FCFS and receives 16 additional milliseconds. If it still does not complete, it is preempted and moved to queue Q 2. Skip 5. 4 Operating System Principles 5. 27 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

5. 5 Multiple-Processor Scheduling n CPU scheduling more complex when multiple CPUs are available n Homogeneous processors within a multiprocessor l We can use any available processor to run any process n Load sharing n Approaches Asymmetric multiprocessing – only one processor accesses the system data structures, alleviating the need for data sharing l Symmetric multiprocessing (SMP) – each processor is self -scheduling l Operating System Principles 5. 28 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

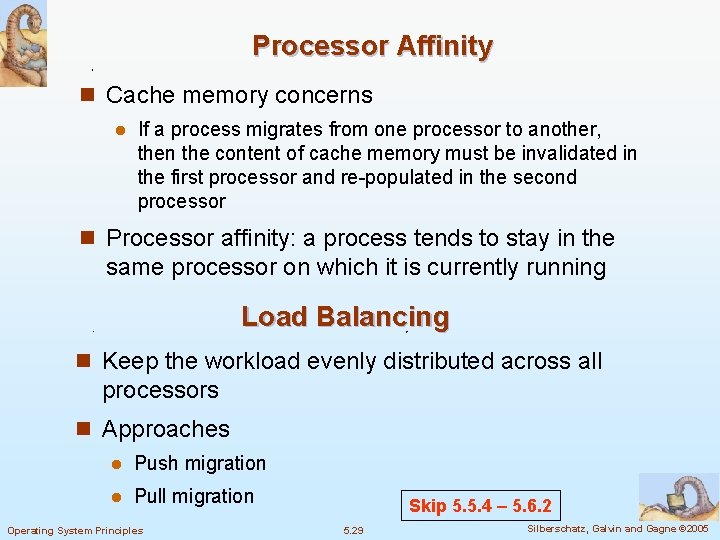

Processor Affinity n Cache memory concerns l If a process migrates from one processor to another, then the content of cache memory must be invalidated in the first processor and re-populated in the second processor n Processor affinity: a process tends to stay in the same processor on which it is currently running Load Balancing n Keep the workload evenly distributed across all processors n Approaches l Push migration l Pull migration Operating System Principles Skip 5. 5. 4 – 5. 6. 2 5. 29 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

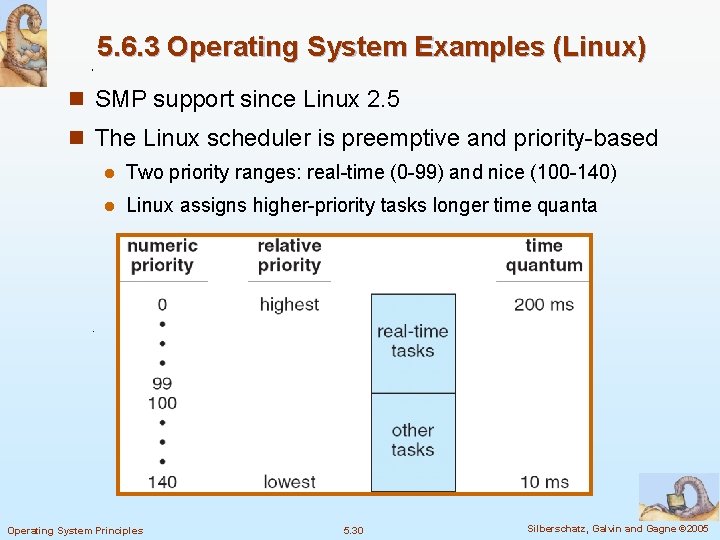

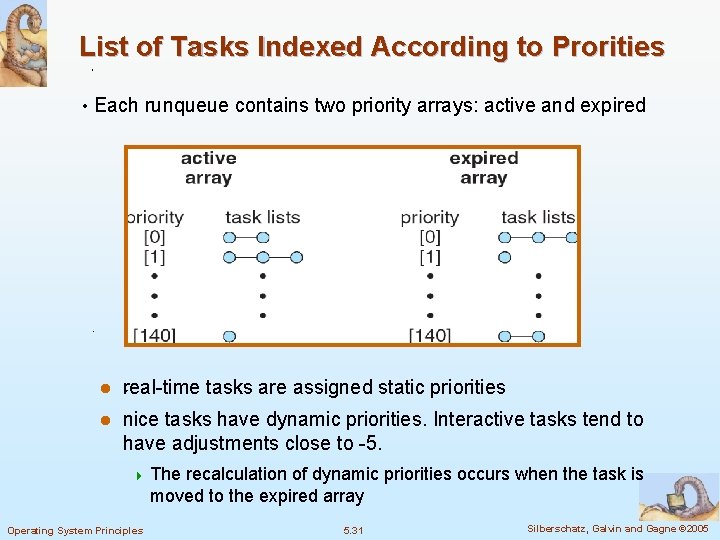

5. 6. 3 Operating System Examples (Linux) n SMP support since Linux 2. 5 n The Linux scheduler is preemptive and priority-based l Two priority ranges: real-time (0 -99) and nice (100 -140) l Linux assigns higher-priority tasks longer time quanta Operating System Principles 5. 30 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

List of Tasks Indexed According to Prorities • Each runqueue contains two priority arrays: active and expired l real-time tasks are assigned static priorities l nice tasks have dynamic priorities. Interactive tasks tend to have adjustments close to -5. 4 The recalculation of dynamic priorities occurs when the task is moved to the expired array Operating System Principles 5. 31 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

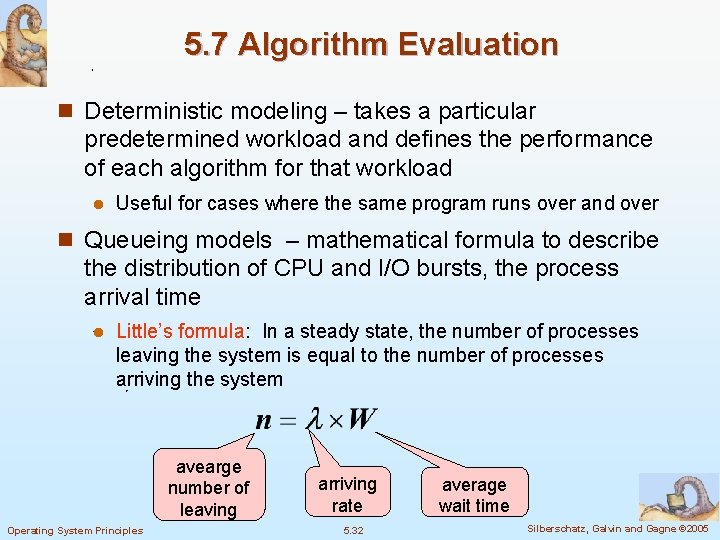

5. 7 Algorithm Evaluation n Deterministic modeling – takes a particular predetermined workload and defines the performance of each algorithm for that workload l Useful for cases where the same program runs over and over n Queueing models – mathematical formula to describe the distribution of CPU and I/O bursts, the process arrival time l Little’s formula: In a steady state, the number of processes leaving the system is equal to the number of processes arriving the system avearge number of leaving Operating System Principles arriving rate 5. 32 average wait time Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

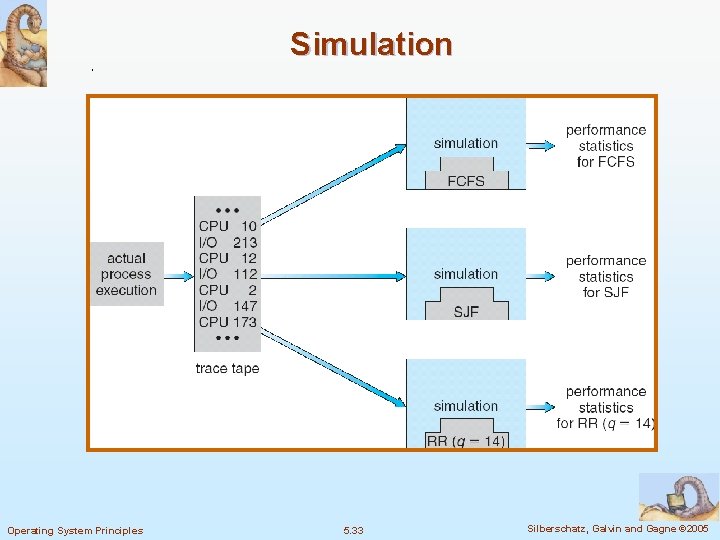

Simulation Operating System Principles 5. 33 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

Implementation n The only complete accurate way to evaluate a scheduling algorithm. l Difficulties: 4 High cost: coding and user reaction 4 Changing environment: users will find out and switch n Most flexible scheduling l Fine tunable for specific applications l Provide a command (like dispadmin in Solaris) to allow system administrators to modify the scheduling parameters l Provide API to modify the priority of a process Operating System Principles 5. 34 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

- Slides: 34