Chapter 4 Topics External Structures Cell Envelope Internal

- Slides: 49

Chapter 4 Topics – External Structures – Cell Envelope – Internal Structures – Cell Shapes, Arrangement, and Sizes – Classification

External Structures • Flagella • Pili and fimbriae • Glycocalyx

Flagella • Composed of protein subunits • Motility (chemotaxis) • Varied arrangement (ex. Monotrichous, lophotrichous, amphitrichous)

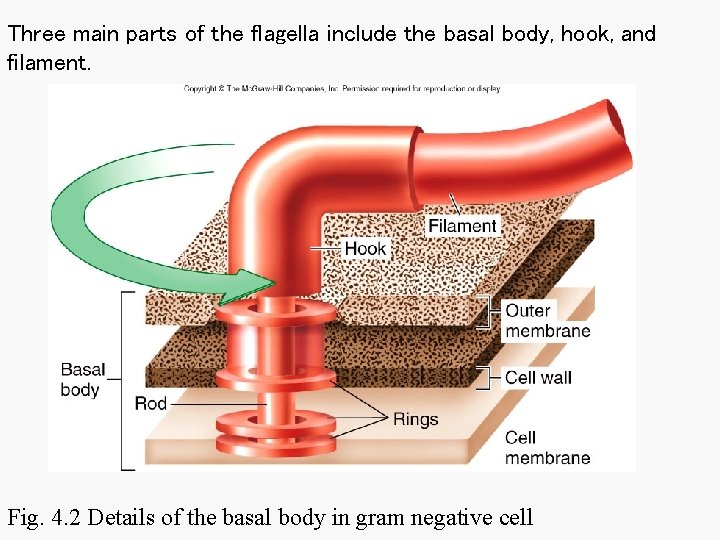

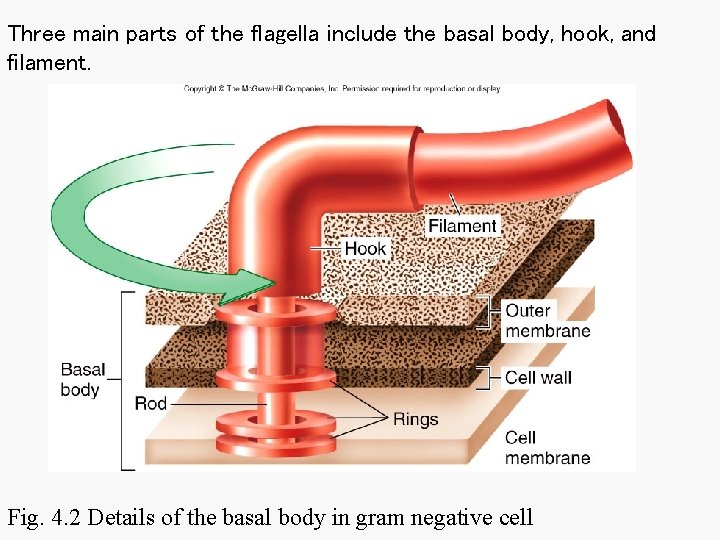

Three main parts of the flagella include the basal body, hook, and filament. Fig. 4. 2 Details of the basal body in gram negative cell

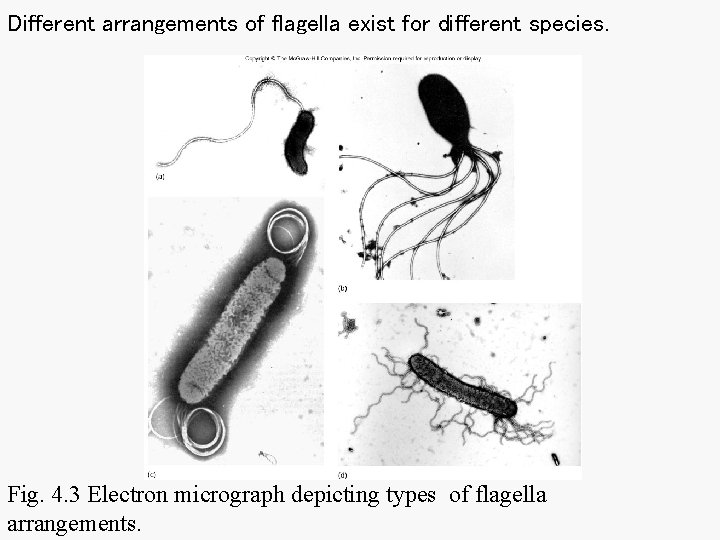

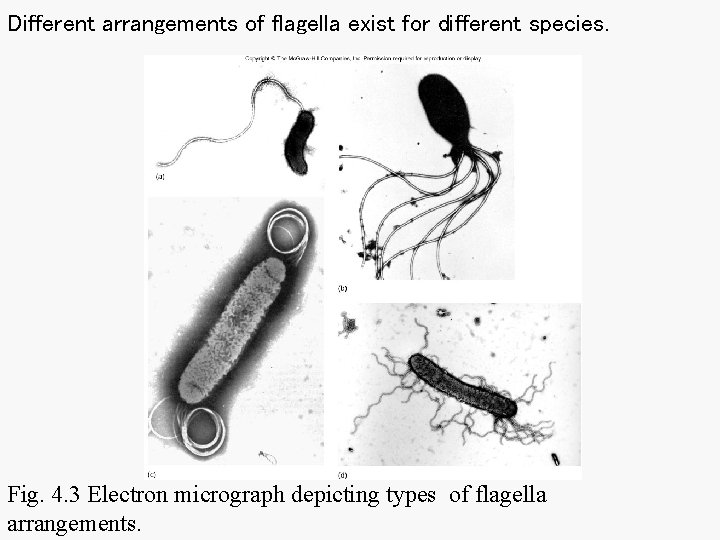

Different arrangements of flagella exist for different species. Fig. 4. 3 Electron micrograph depicting types of flagella arrangements.

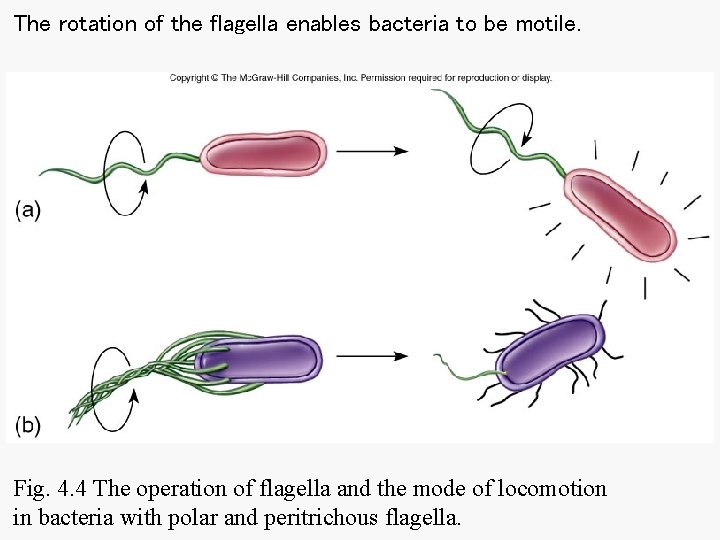

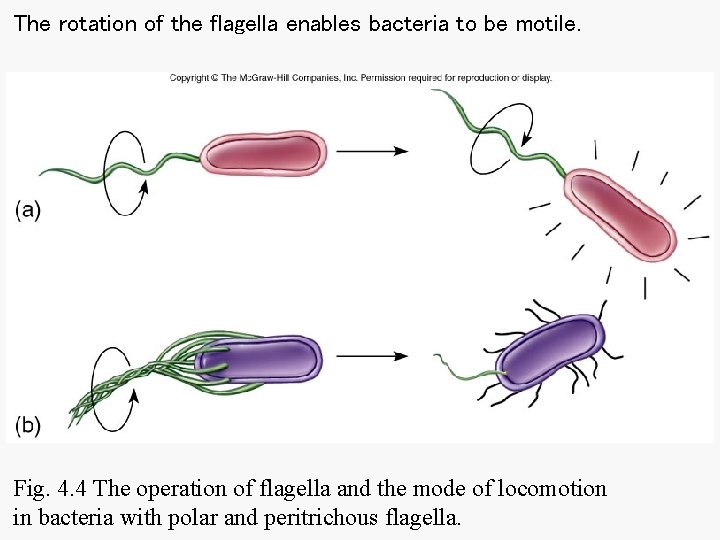

The rotation of the flagella enables bacteria to be motile. Fig. 4. 4 The operation of flagella and the mode of locomotion in bacteria with polar and peritrichous flagella.

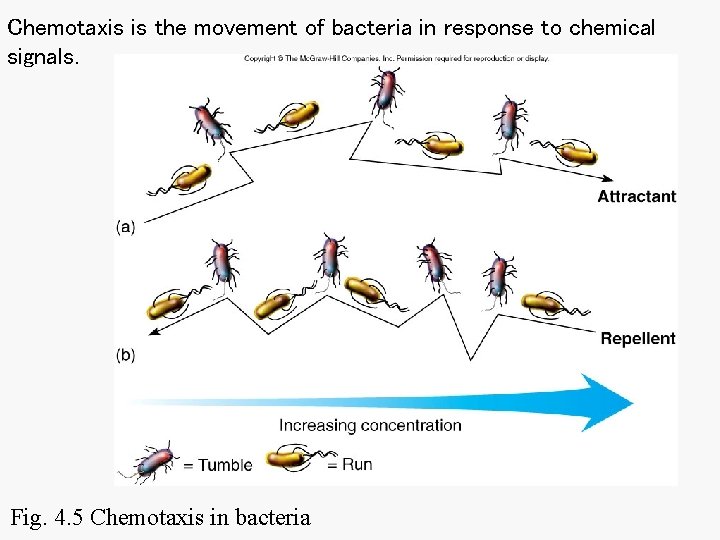

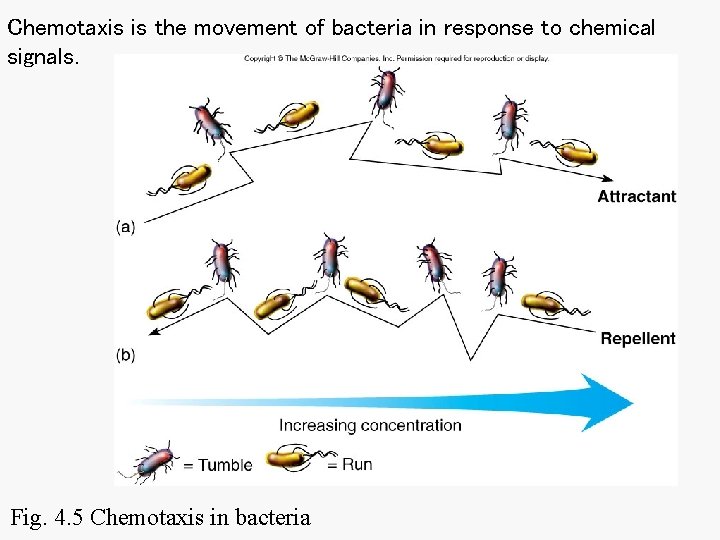

Chemotaxis is the movement of bacteria in response to chemical signals. Fig. 4. 5 Chemotaxis in bacteria

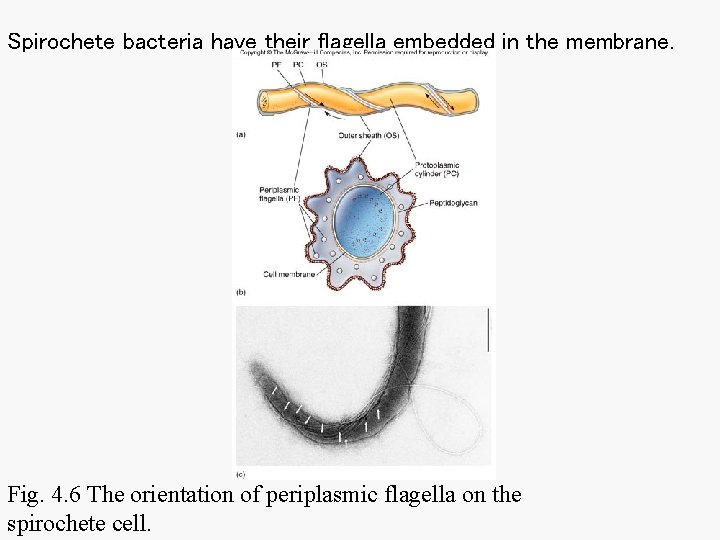

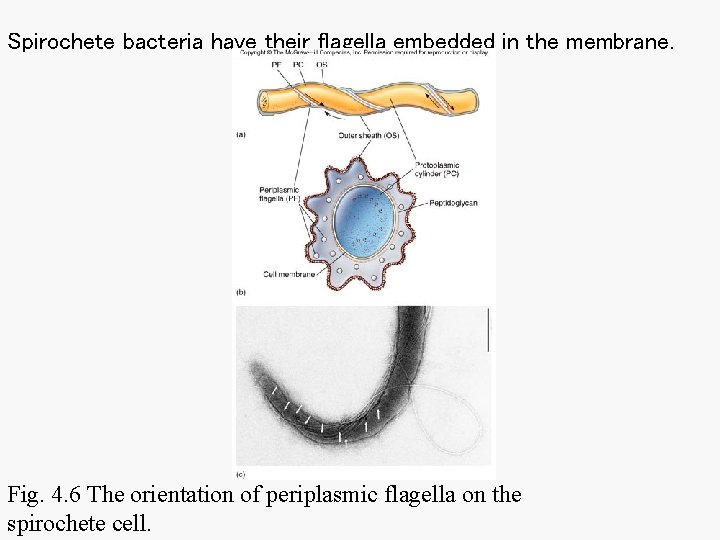

Spirochete bacteria have their flagella embedded in the membrane. Fig. 4. 6 The orientation of periplasmic flagella on the spirochete cell.

Pili and fimbriae • Attachment • Mating (Conjugation)

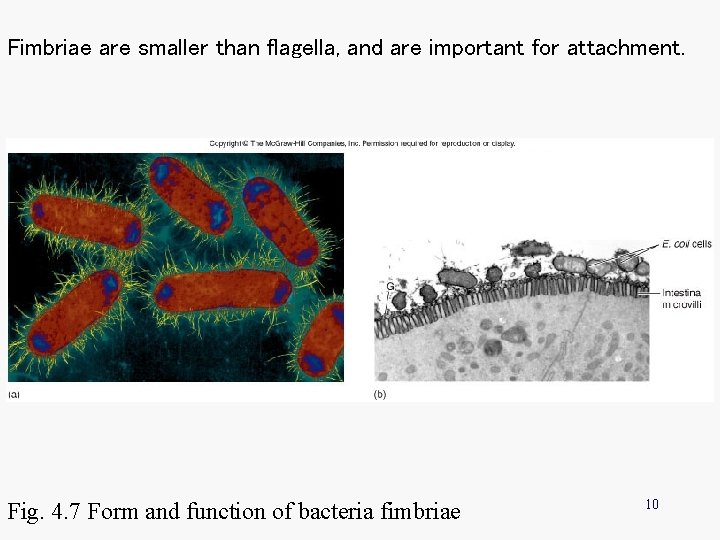

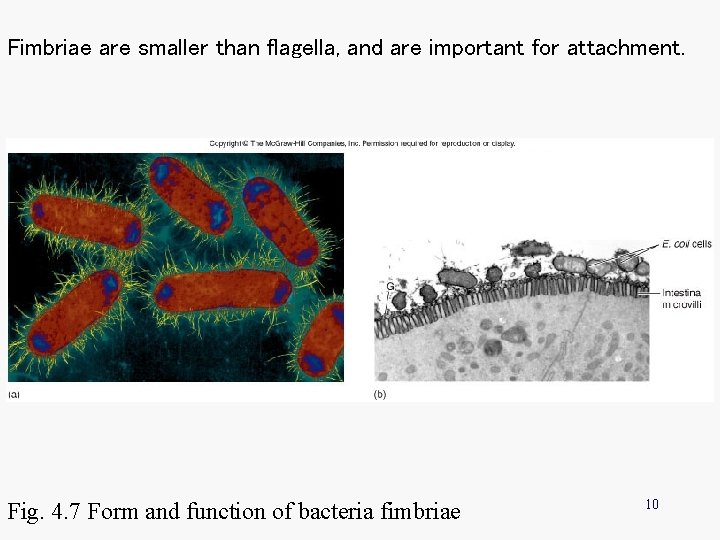

Fimbriae are smaller than flagella, and are important for attachment. Fig. 4. 7 Form and function of bacteria fimbriae 10

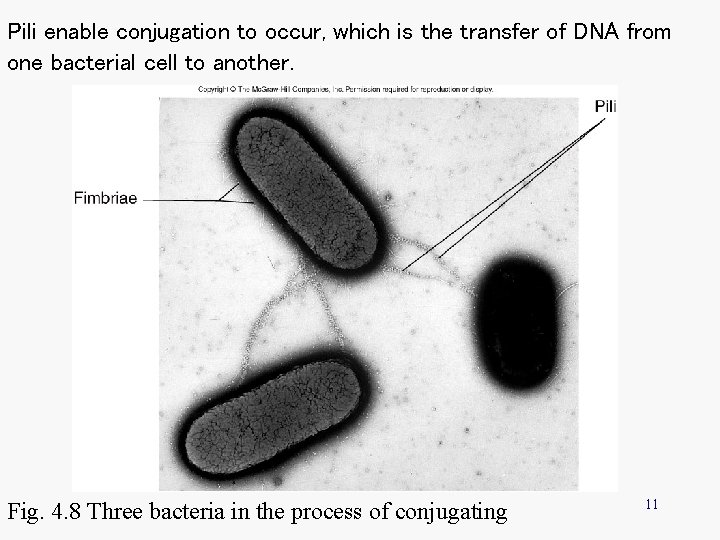

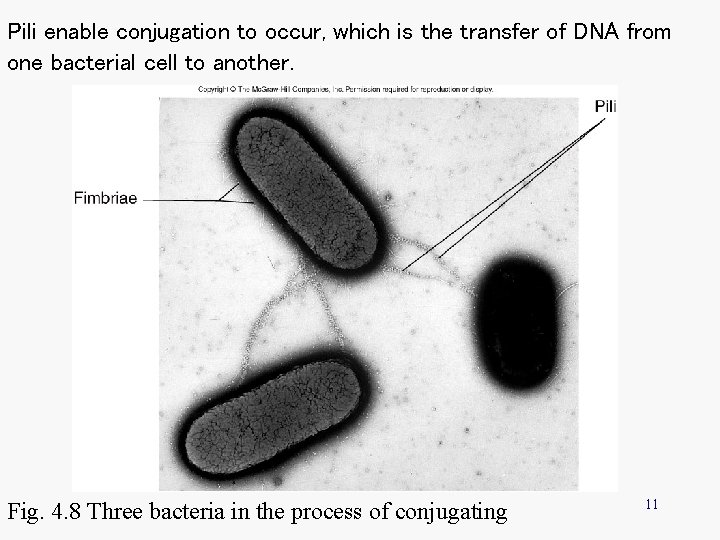

Pili enable conjugation to occur, which is the transfer of DNA from one bacterial cell to another. Fig. 4. 8 Three bacteria in the process of conjugating 11

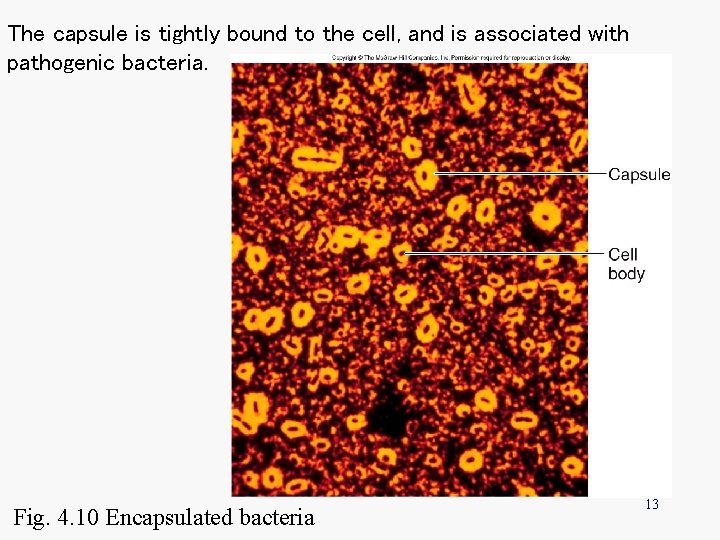

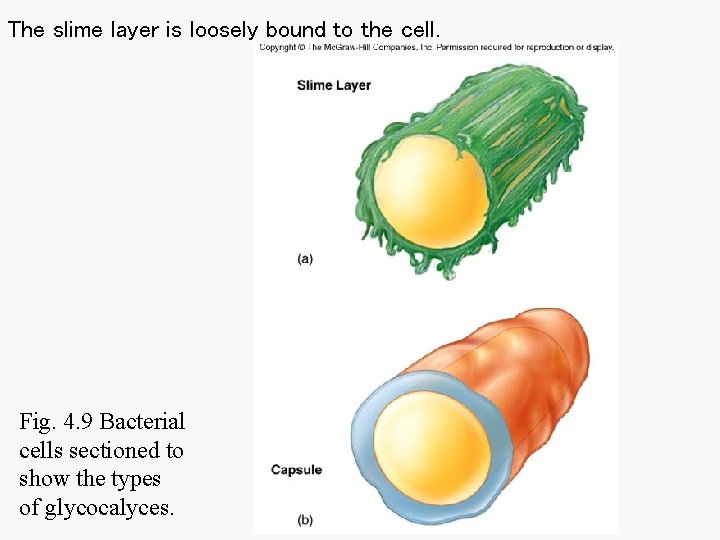

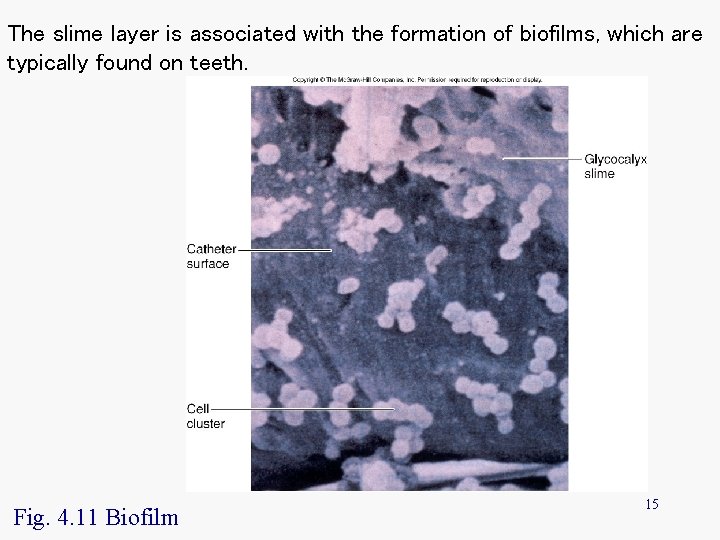

Glycocalyx • Capsule – Protects bacteria from immune cells • Slime layer – Enable attachment and aggregation of bacterial cells

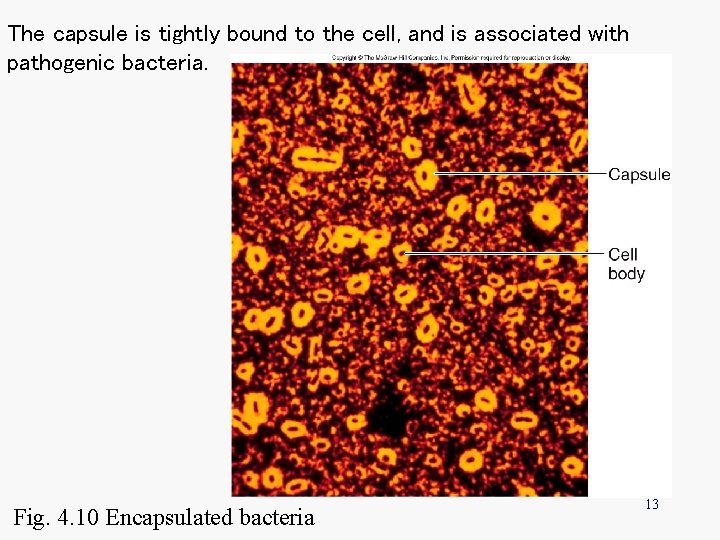

The capsule is tightly bound to the cell, and is associated with pathogenic bacteria. Fig. 4. 10 Encapsulated bacteria 13

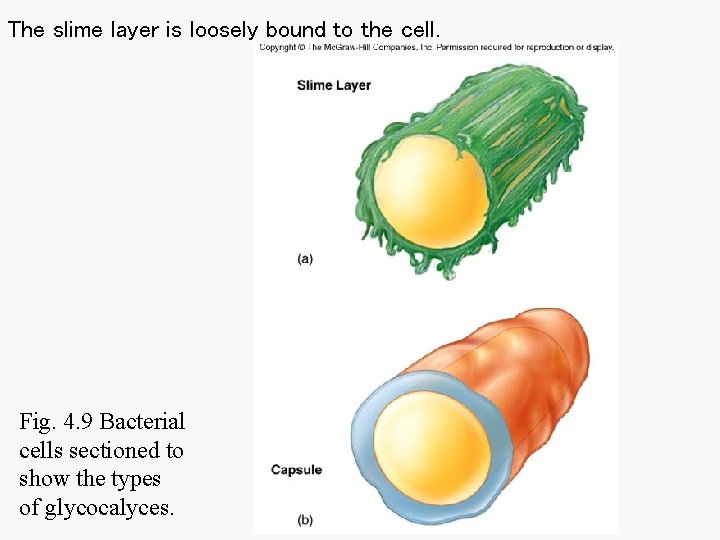

The slime layer is loosely bound to the cell. Fig. 4. 9 Bacterial cells sectioned to show the types of glycocalyces.

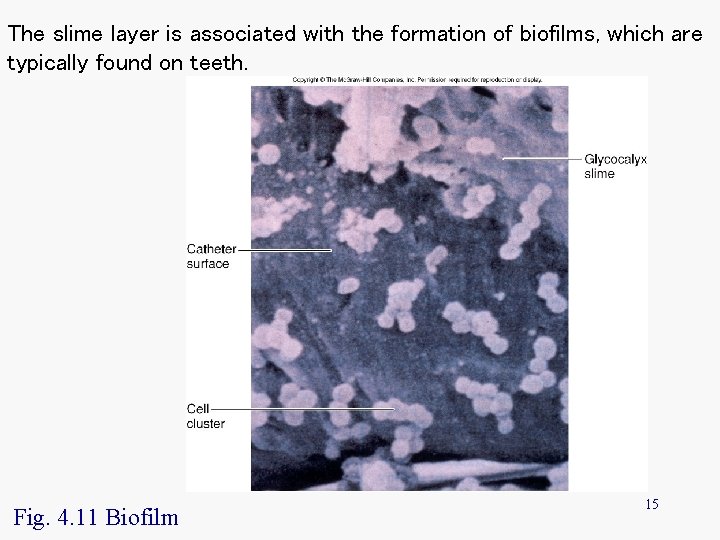

The slime layer is associated with the formation of biofilms, which are typically found on teeth. Fig. 4. 11 Biofilm 15

Cell envelope • Cell wall – Gram-positive – Gram-negative • Cytoplasmic membrane • Non cell wall

Cell wall • Gram positive cell wall – Thick peptidoglycan (PG) layer – Acidic polysaccharides – Teichoic acid and lipoteichoic acid • Gram-negative cell wall – – Thin PG layer Outer membrane Lipid polysaccharide Porins

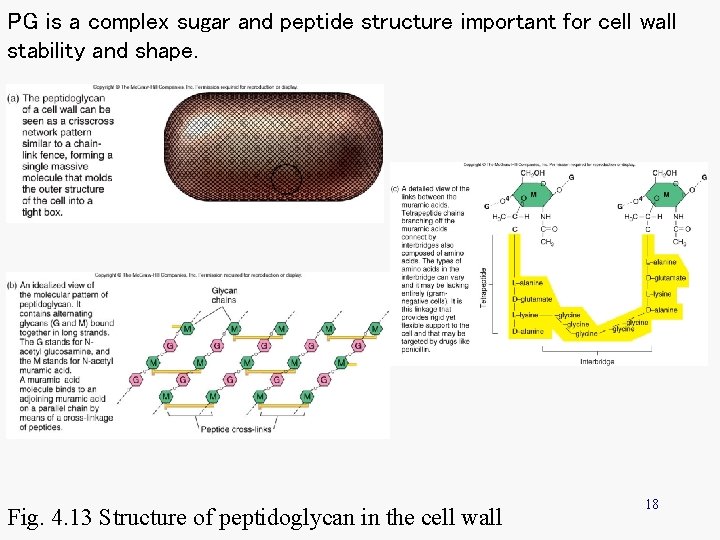

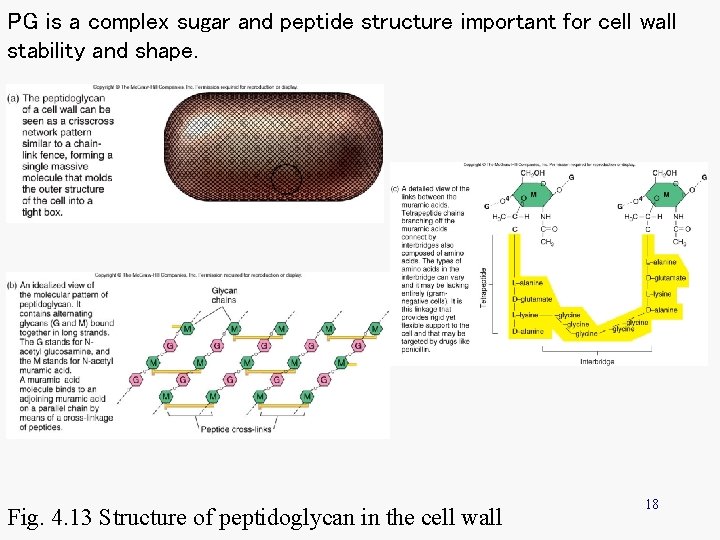

PG is a complex sugar and peptide structure important for cell wall stability and shape. Fig. 4. 13 Structure of peptidoglycan in the cell wall 18

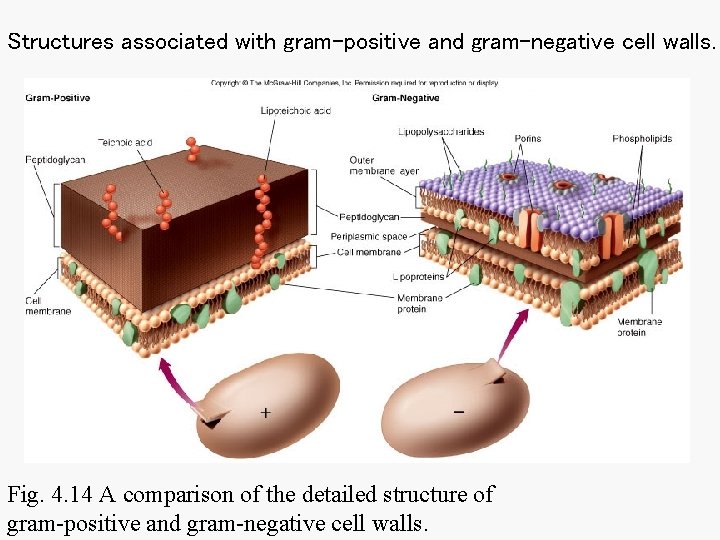

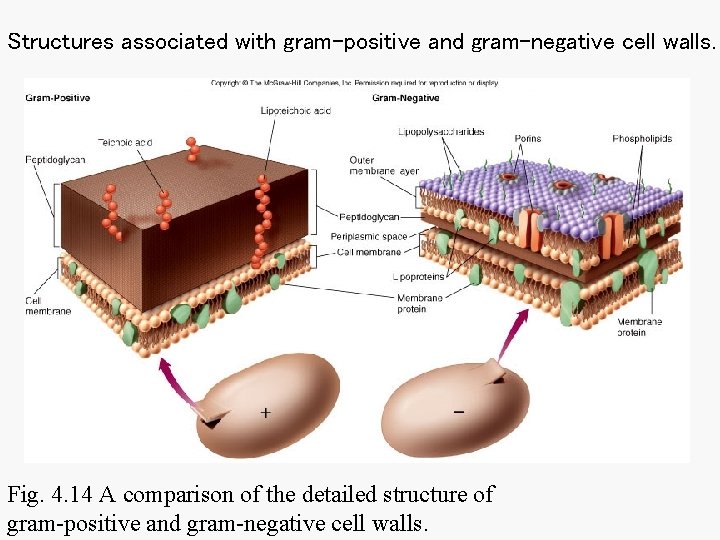

Structures associated with gram-positive and gram-negative cell walls. Fig. 4. 14 A comparison of the detailed structure of gram-positive and gram-negative cell walls.

Cytoplasmic membrane • • L-forms Embedded proteins Energy generation Transport

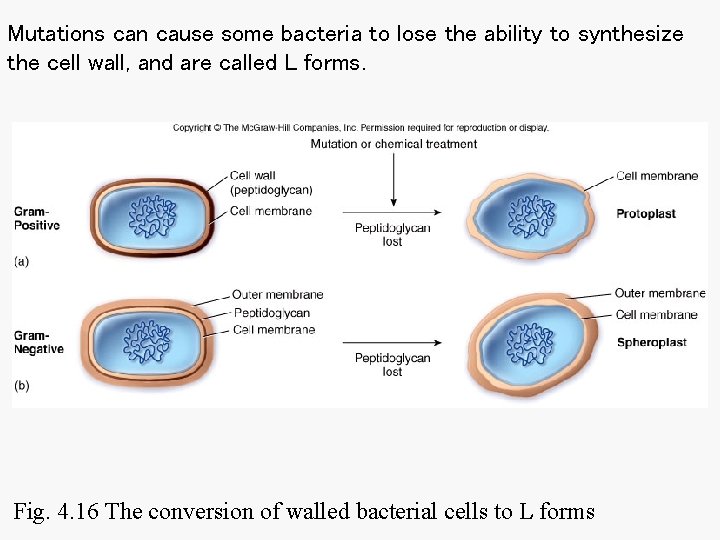

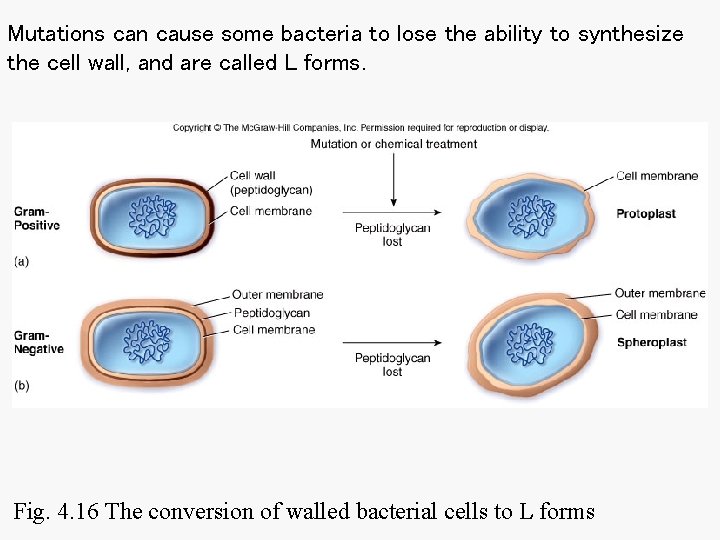

Mutations can cause some bacteria to lose the ability to synthesize the cell wall, and are called L forms. Fig. 4. 16 The conversion of walled bacterial cells to L forms

No cell wall • No PG layer • Cell membrane contain sterols for stability

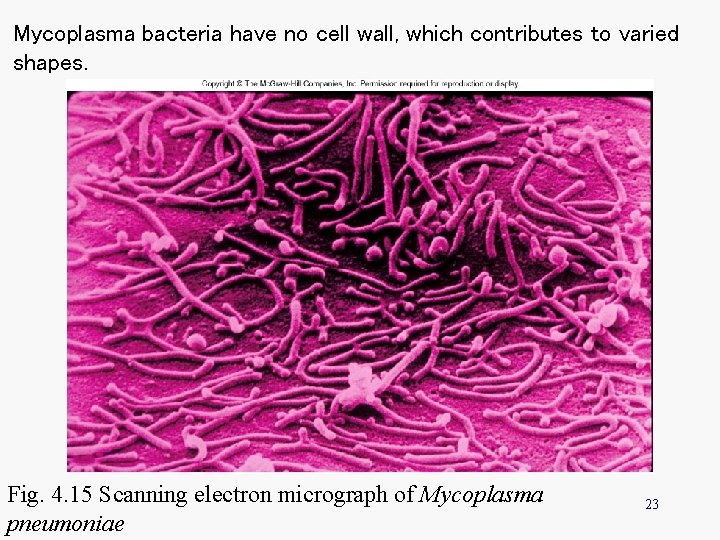

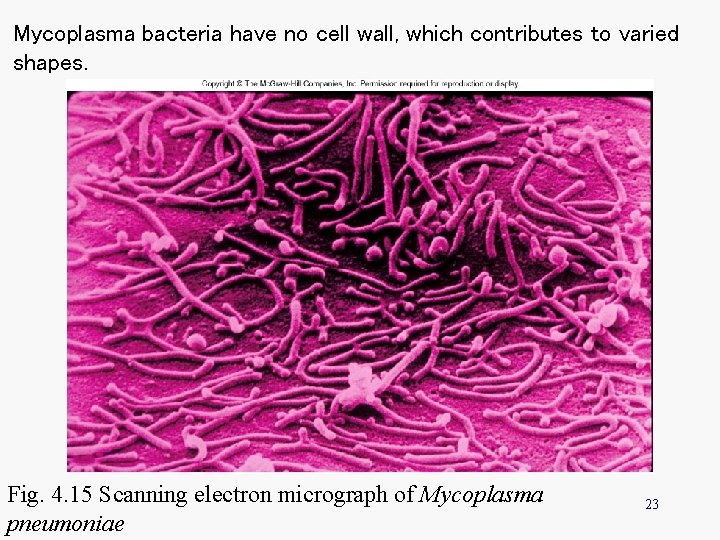

Mycoplasma bacteria have no cell wall, which contributes to varied shapes. Fig. 4. 15 Scanning electron micrograph of Mycoplasma pneumoniae 23

Internal Structures • • • Cytoplasm Genetic structures Storage bodies Actin Endospore

Cytoplasm • Gelatinous solution containing water, nutrients, proteins, and genetic material. • Site for cell metabolism

Genetic structures • Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) • Ribonucleic acid (RNA) • Ribosomes

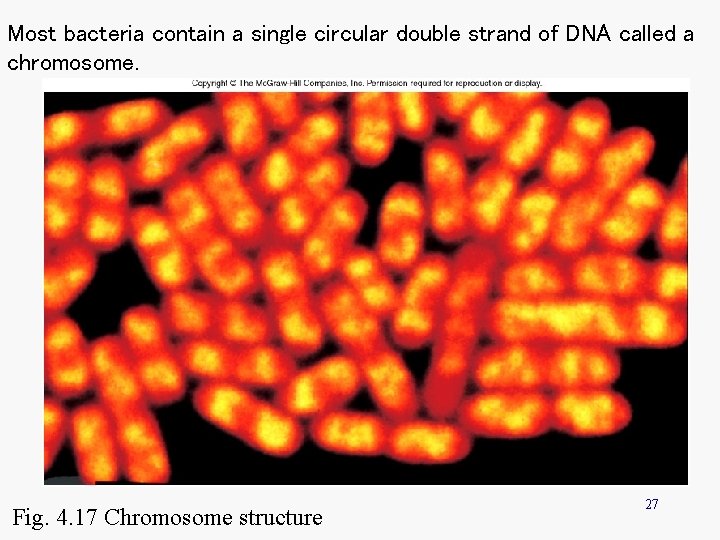

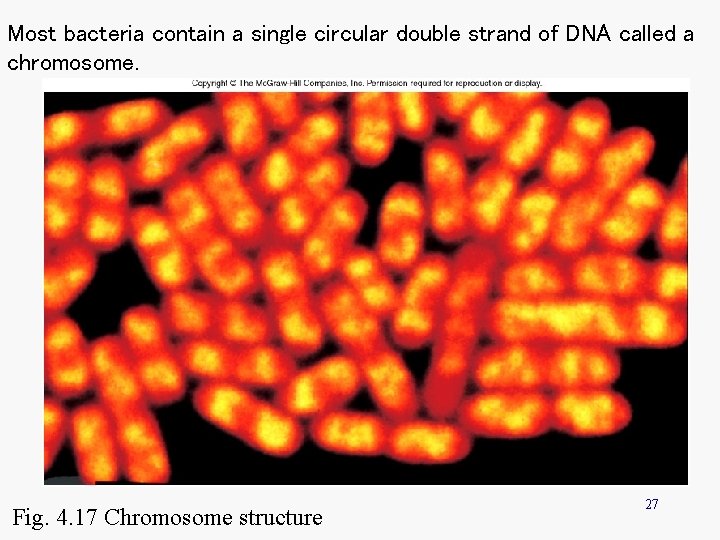

Most bacteria contain a single circular double strand of DNA called a chromosome. Fig. 4. 17 Chromosome structure 27

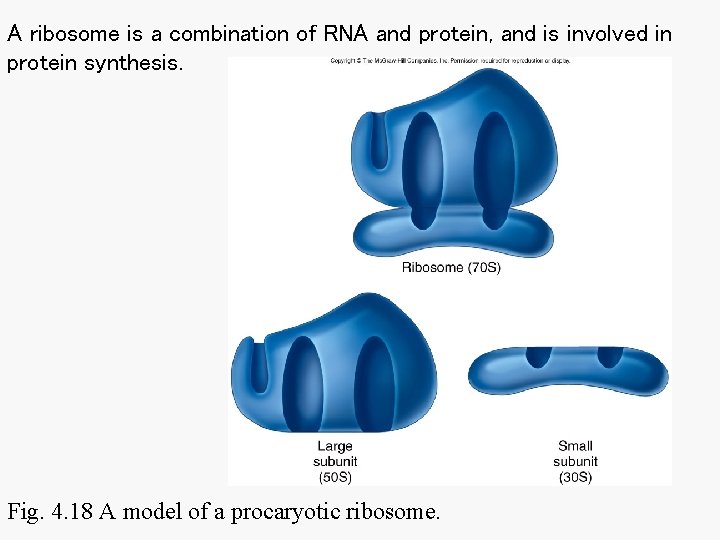

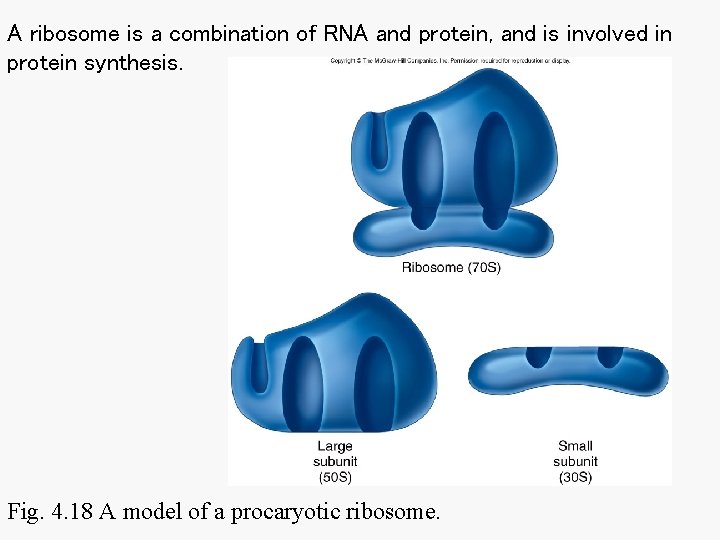

A ribosome is a combination of RNA and protein, and is involved in protein synthesis. Fig. 4. 18 A model of a procaryotic ribosome.

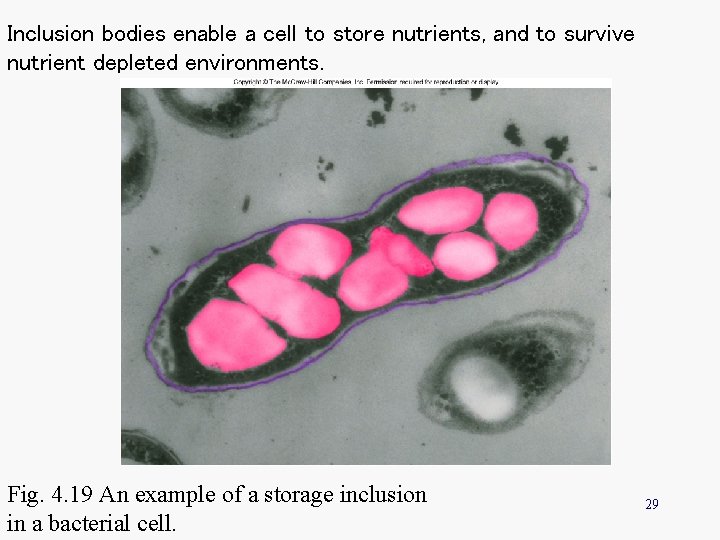

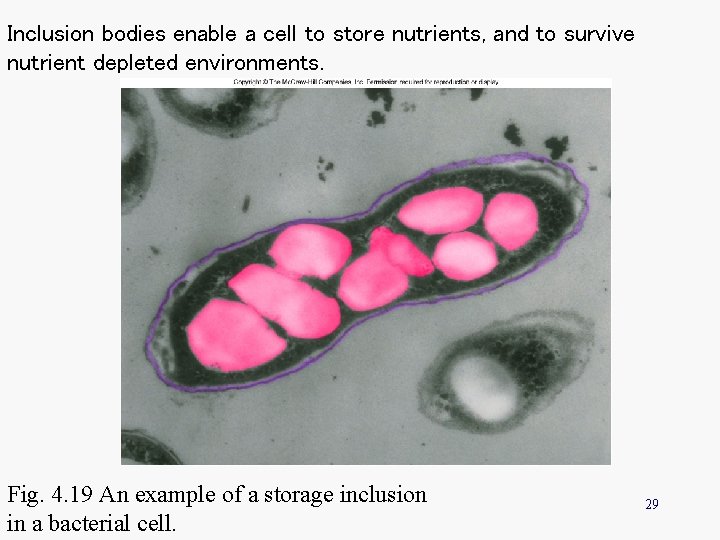

Inclusion bodies enable a cell to store nutrients, and to survive nutrient depleted environments. Fig. 4. 19 An example of a storage inclusion in a bacterial cell. 29

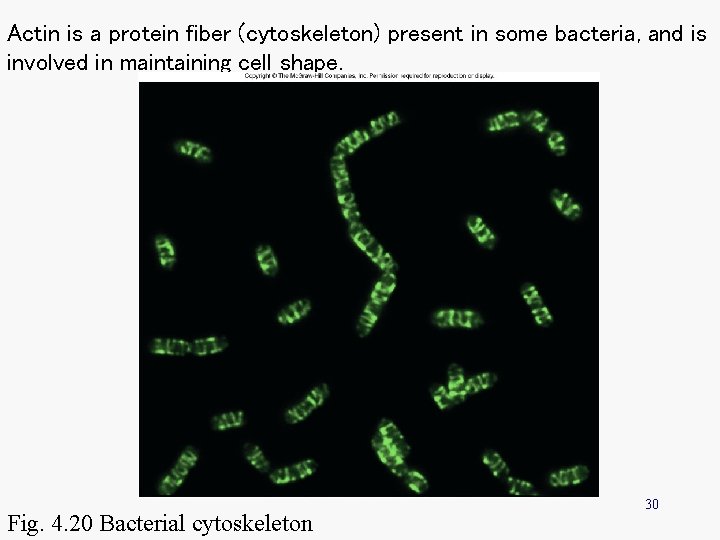

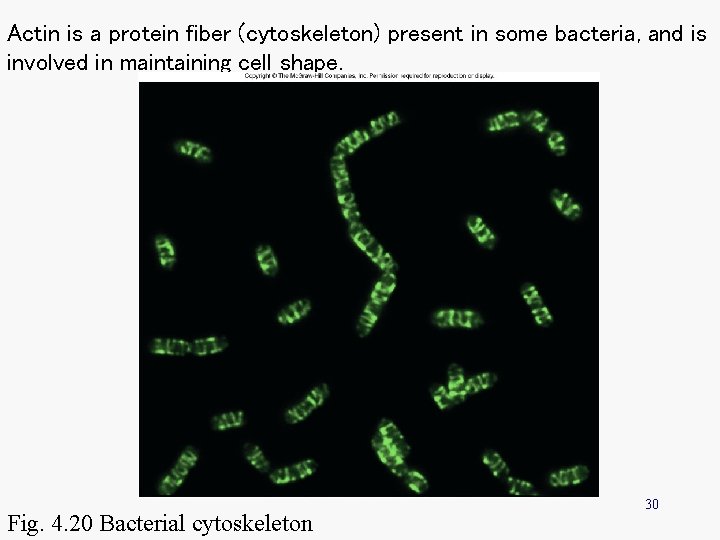

Actin is a protein fiber (cytoskeleton) present in some bacteria, and is involved in maintaining cell shape. Fig. 4. 20 Bacterial cytoskeleton 30

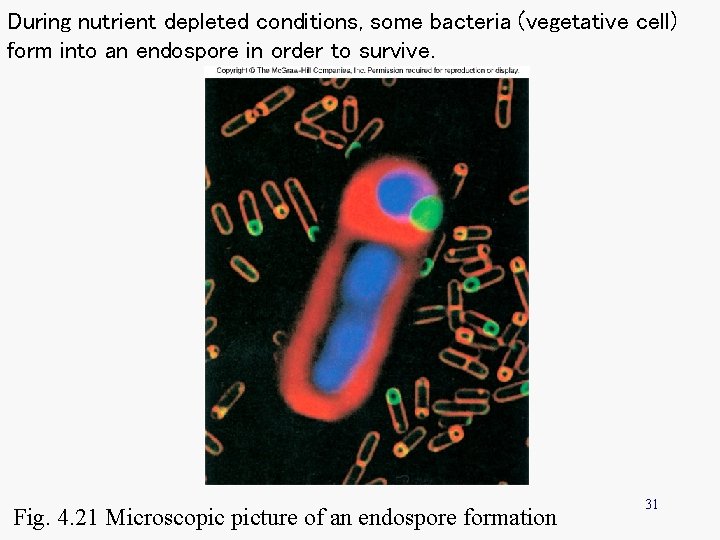

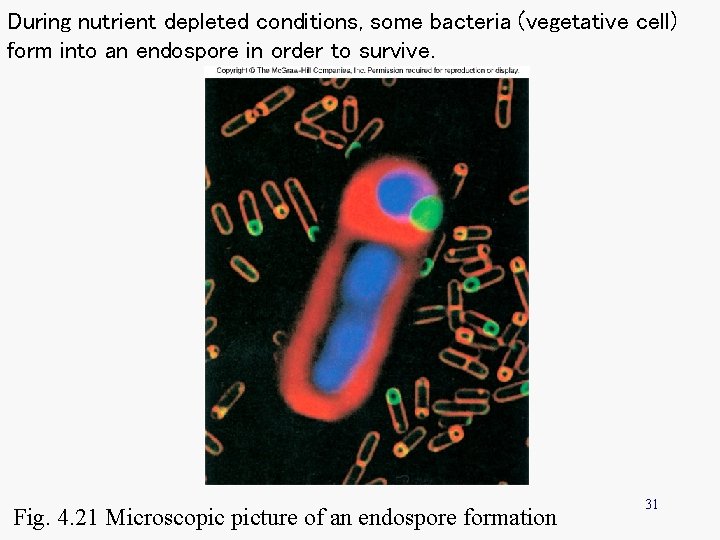

During nutrient depleted conditions, some bacteria (vegetative cell) form into an endospore in order to survive. Fig. 4. 21 Microscopic picture of an endospore formation 31

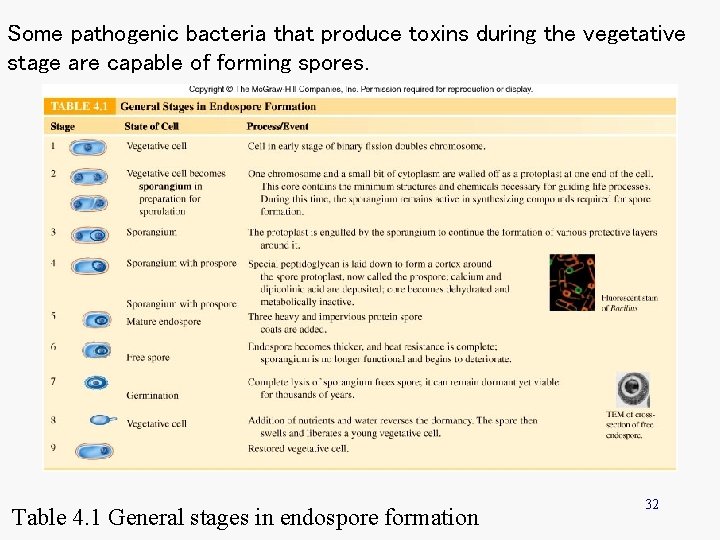

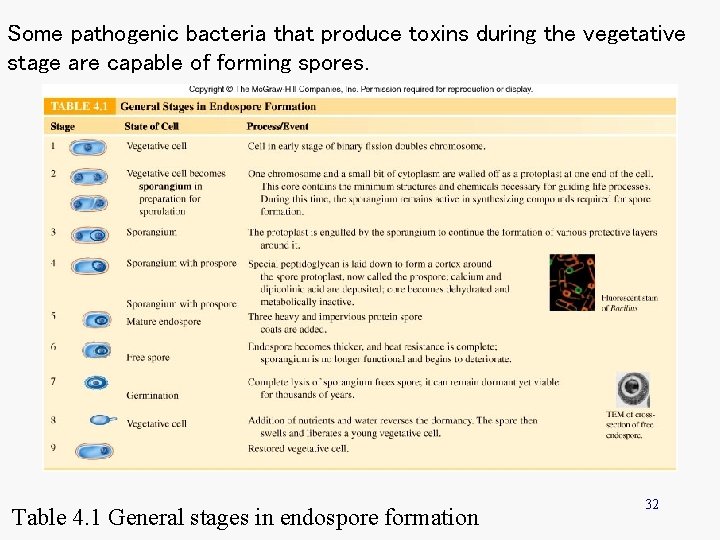

Some pathogenic bacteria that produce toxins during the vegetative stage are capable of forming spores. Table 4. 1 General stages in endospore formation 32

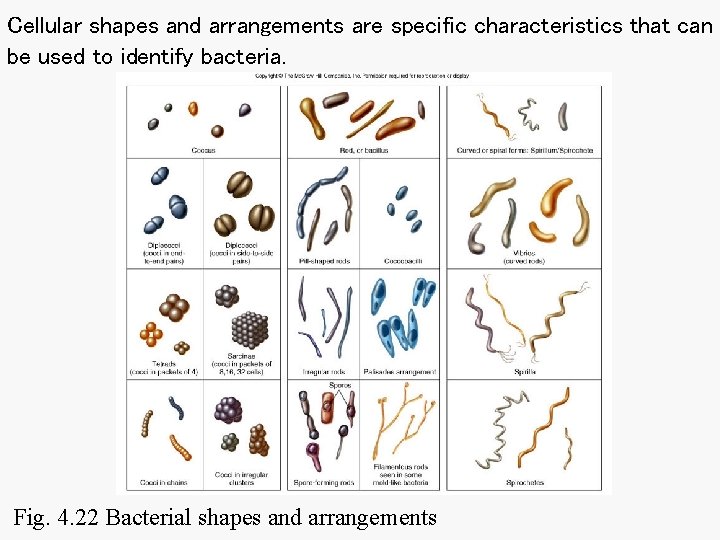

Cell shapes • • • Coccus Rod or bacillus Curved or spiral Cell arrangements Cell size

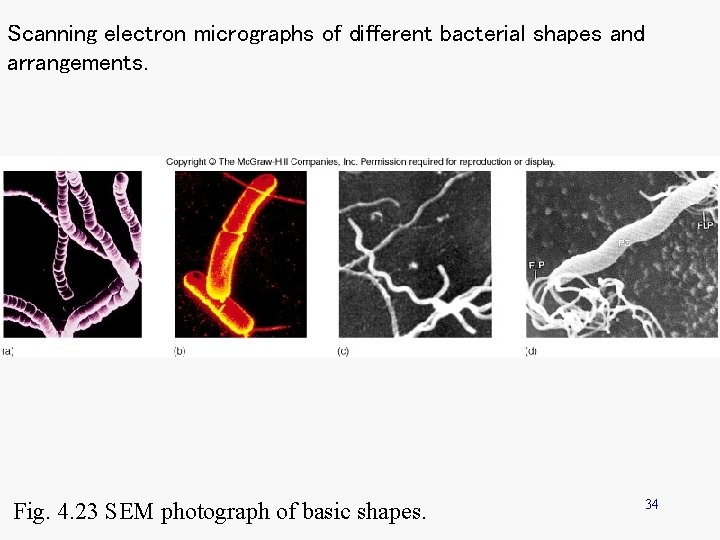

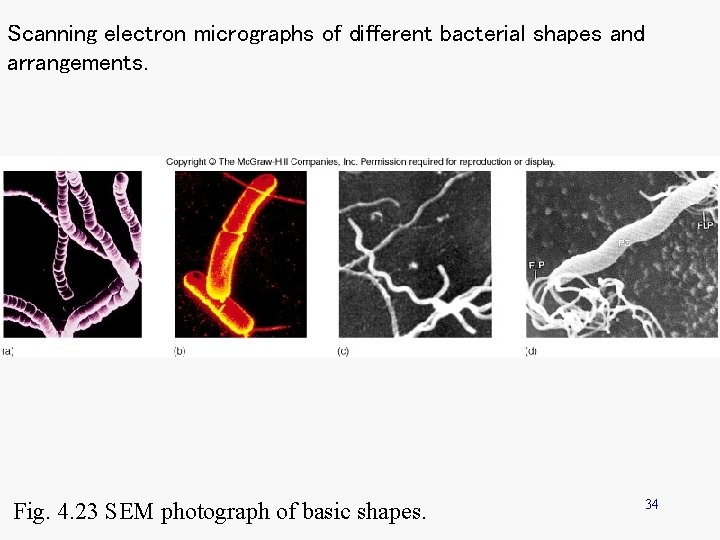

Scanning electron micrographs of different bacterial shapes and arrangements. Fig. 4. 23 SEM photograph of basic shapes. 34

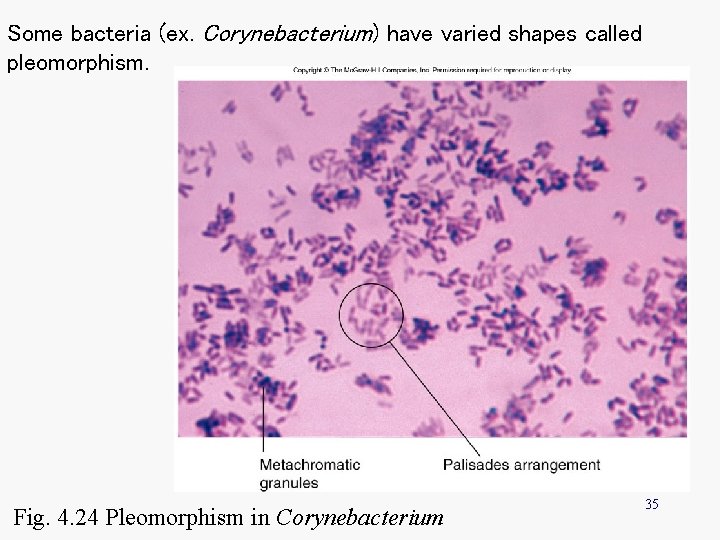

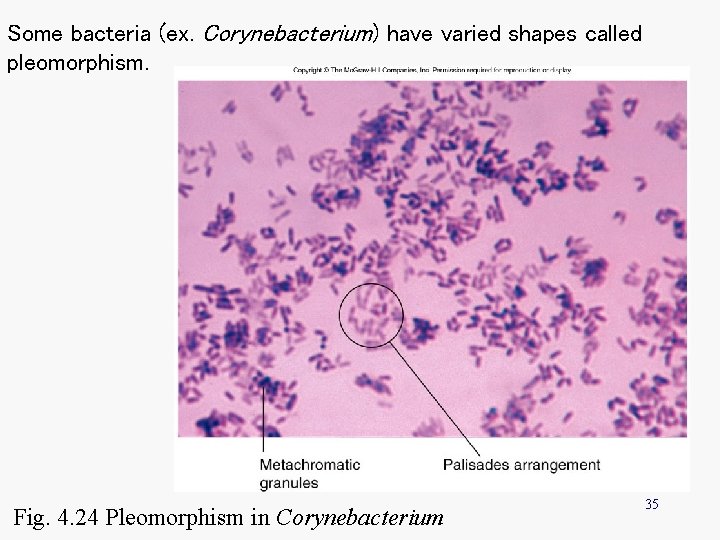

Some bacteria (ex. Corynebacterium) have varied shapes called pleomorphism. Fig. 4. 24 Pleomorphism in Corynebacterium 35

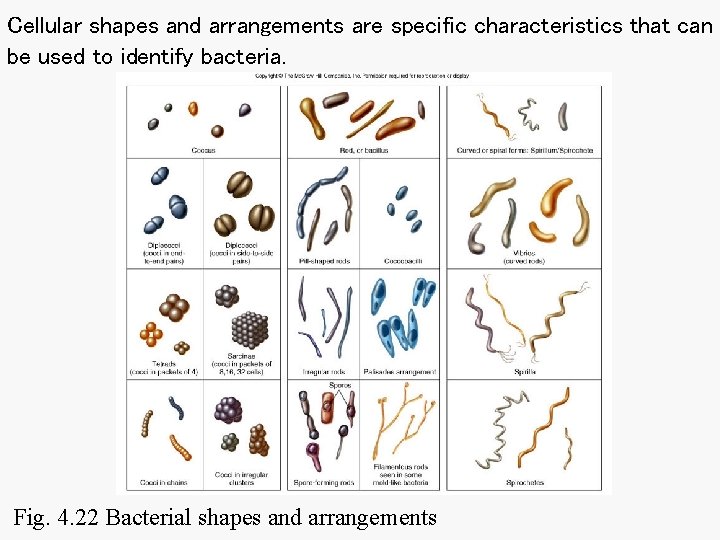

Cellular shapes and arrangements are specific characteristics that can be used to identify bacteria. Fig. 4. 22 Bacterial shapes and arrangements

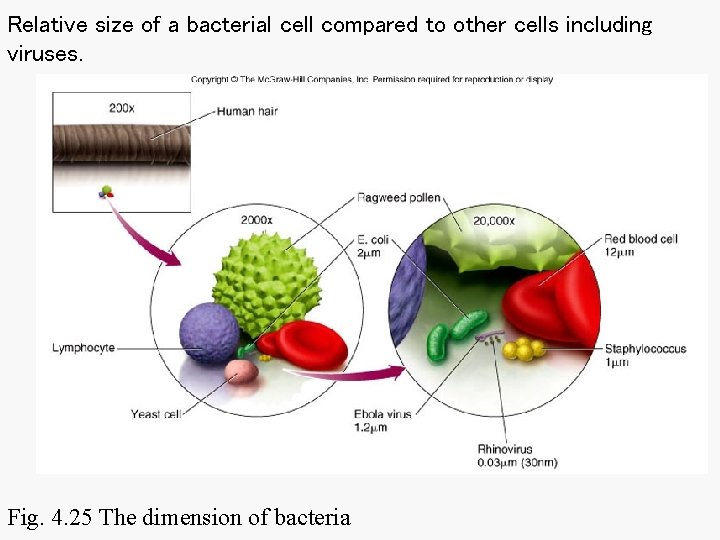

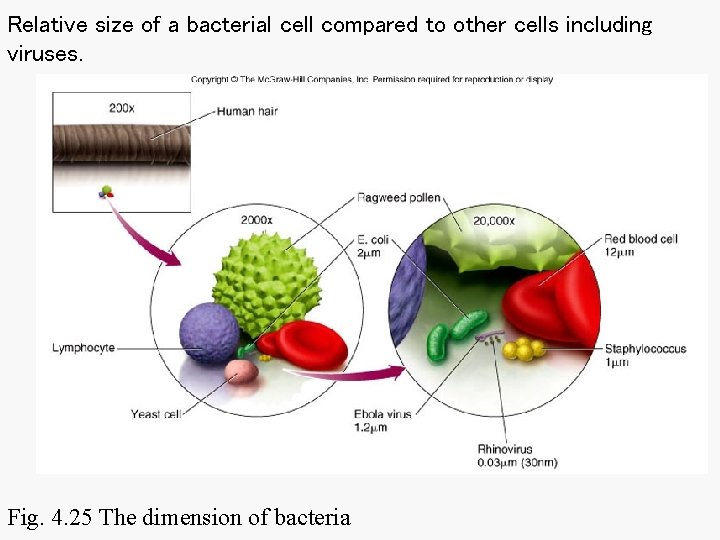

Relative size of a bacterial cell compared to other cells including viruses. Fig. 4. 25 The dimension of bacteria

Classification • • Phenotypic methods Molecular methods Taxonomic scheme Unique groups

Phenotypic methods • Cell morphology -staining • Biochemical test – enzyme test

Molecular methods • DNA sequence • 16 S RNA • Protein sequence

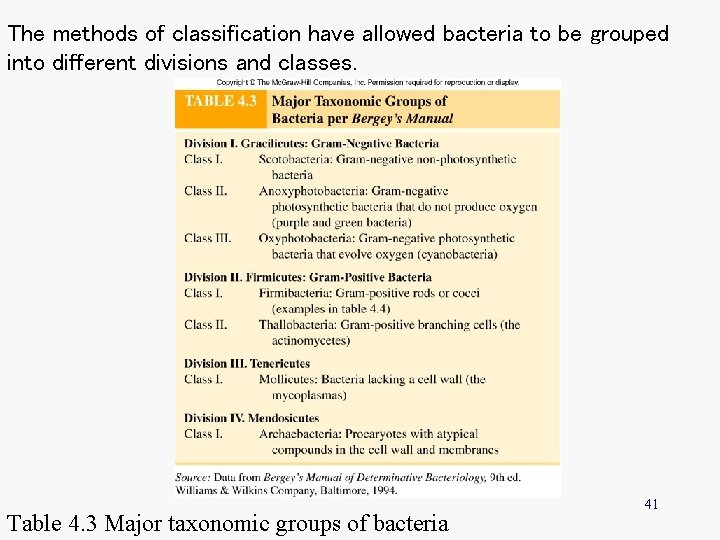

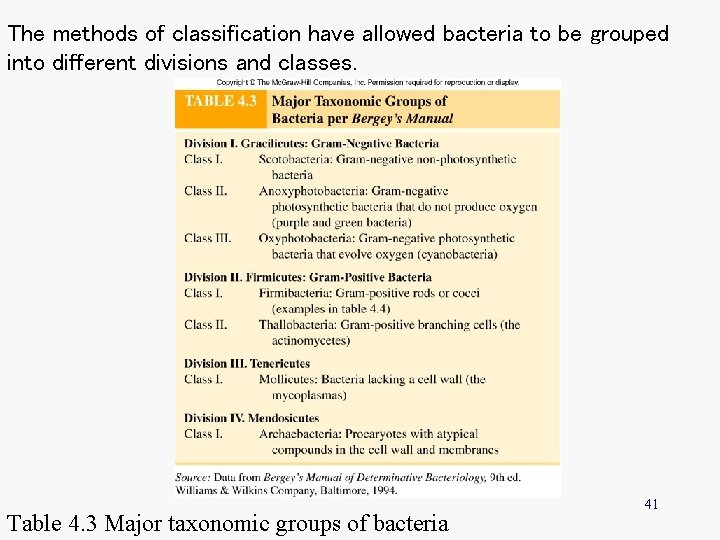

The methods of classification have allowed bacteria to be grouped into different divisions and classes. Table 4. 3 Major taxonomic groups of bacteria 41

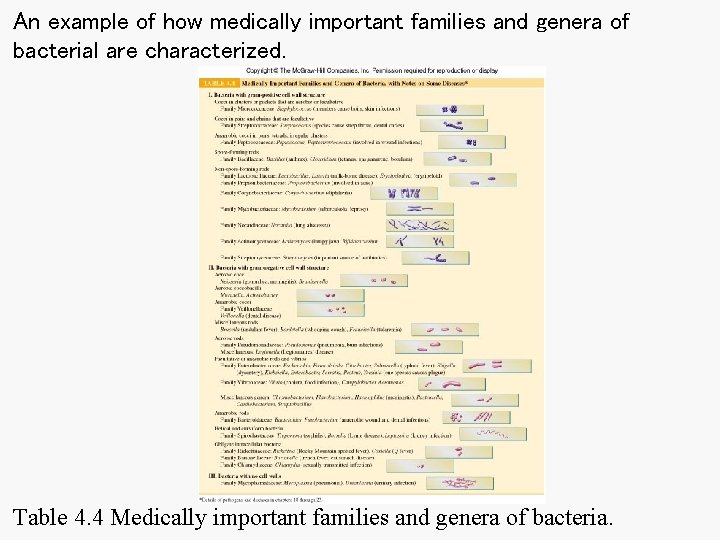

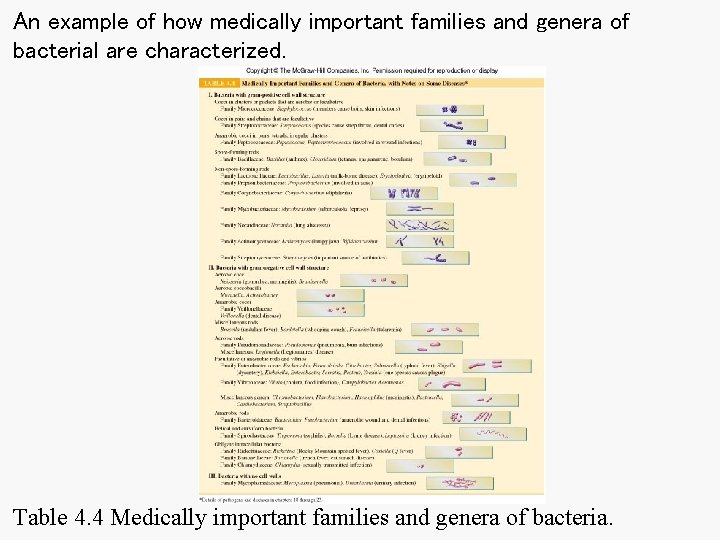

An example of how medically important families and genera of bacterial are characterized. Table 4. 4 Medically important families and genera of bacteria.

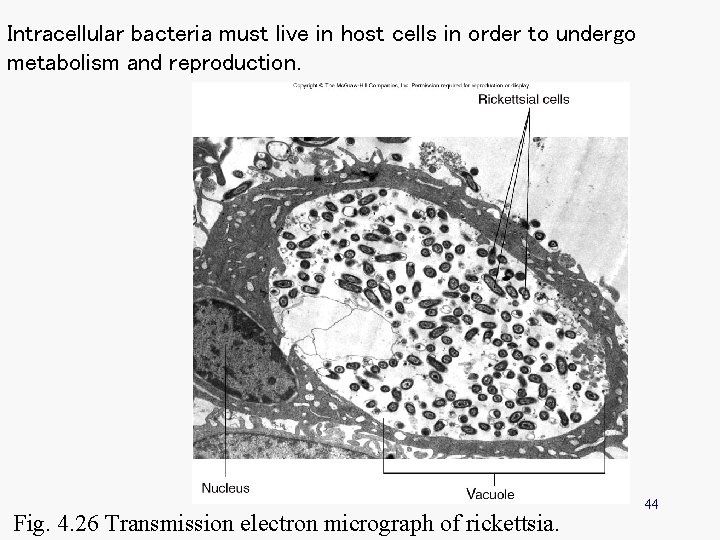

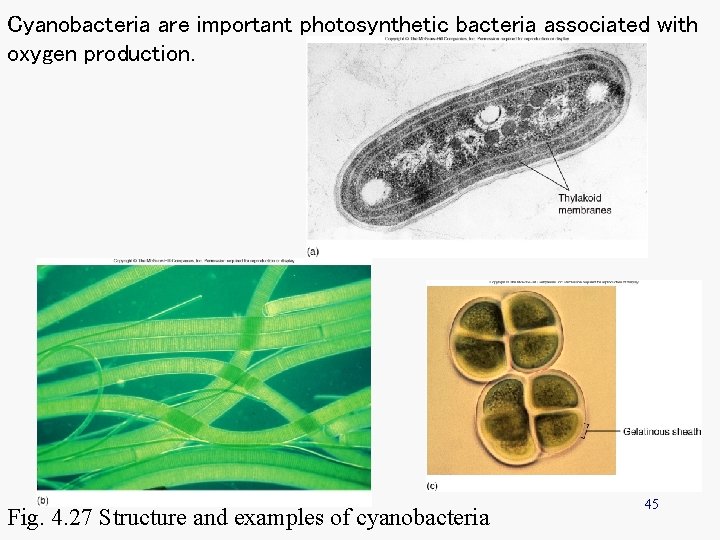

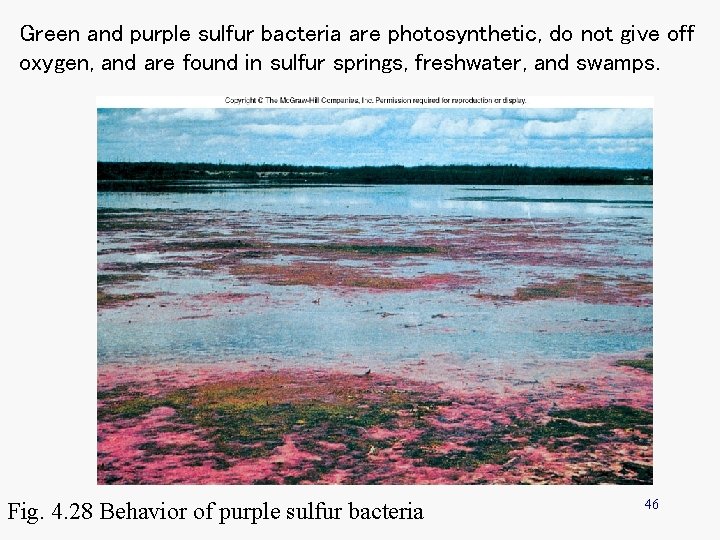

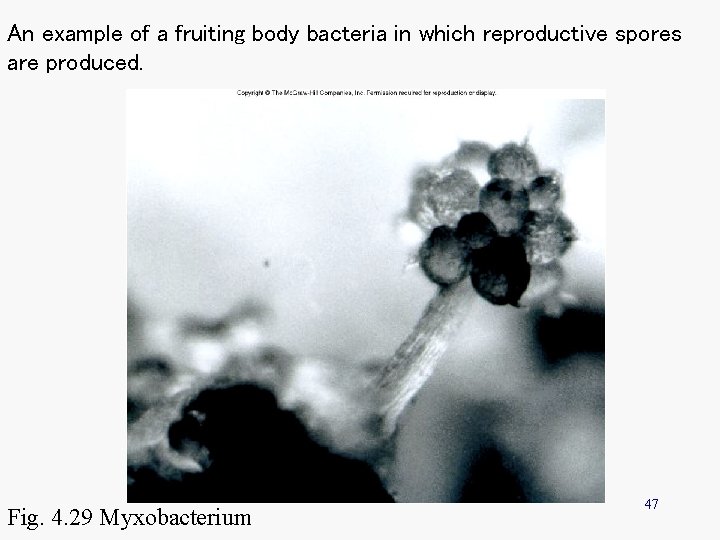

Unique groups of bacteria • • • Intracellular parasites Photosynthetic bacteria Green and purple sulfur bacteria Gliding and fruiting bacteria Archaea bacteria

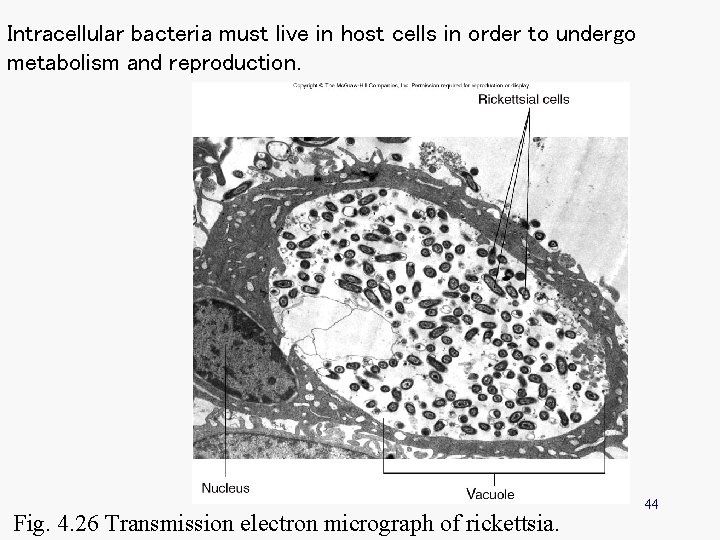

Intracellular bacteria must live in host cells in order to undergo metabolism and reproduction. Fig. 4. 26 Transmission electron micrograph of rickettsia. 44

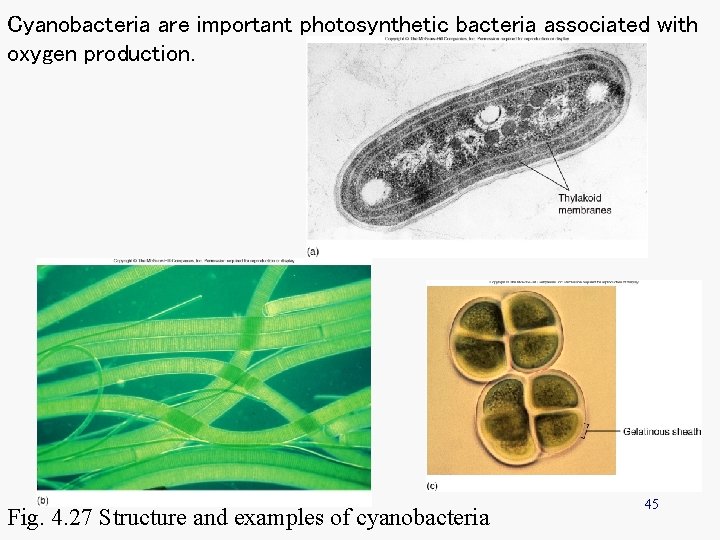

Cyanobacteria are important photosynthetic bacteria associated with oxygen production. Fig. 4. 27 Structure and examples of cyanobacteria 45

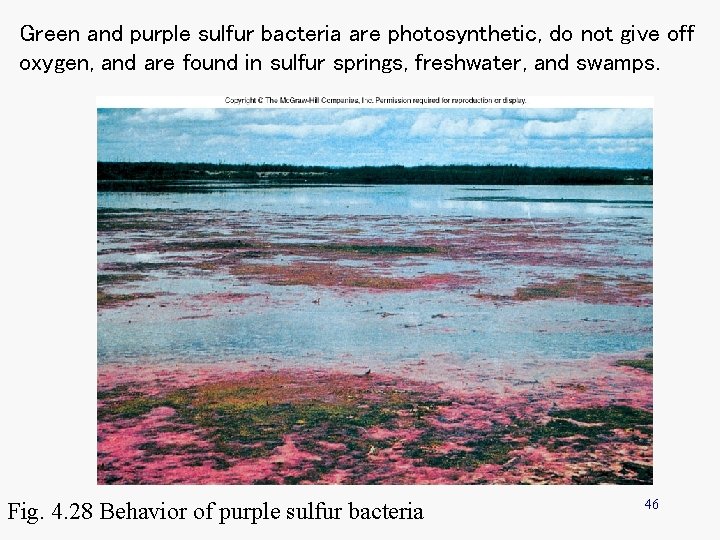

Green and purple sulfur bacteria are photosynthetic, do not give off oxygen, and are found in sulfur springs, freshwater, and swamps. Fig. 4. 28 Behavior of purple sulfur bacteria 46

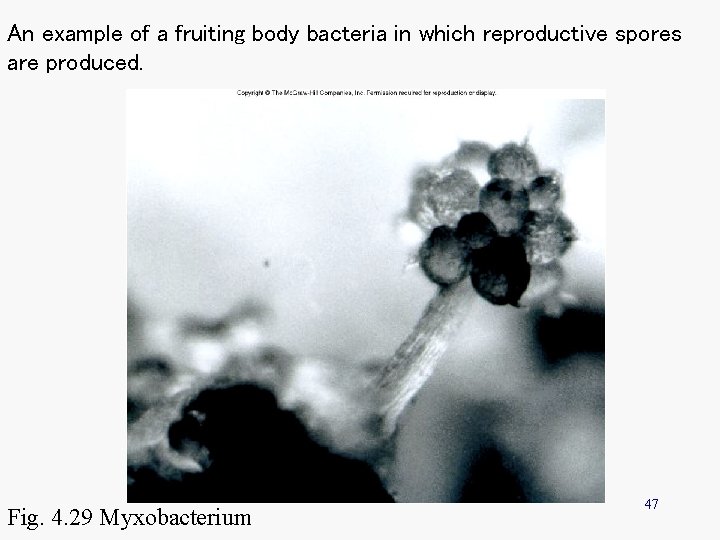

An example of a fruiting body bacteria in which reproductive spores are produced. Fig. 4. 29 Myxobacterium 47

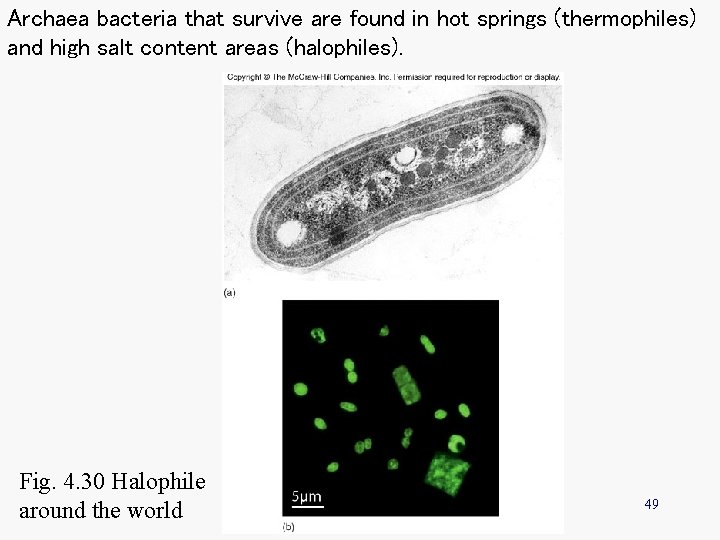

Archaea bacteria • Associated with extreme environments • Contain unique cell walls • Contain unique internal structures

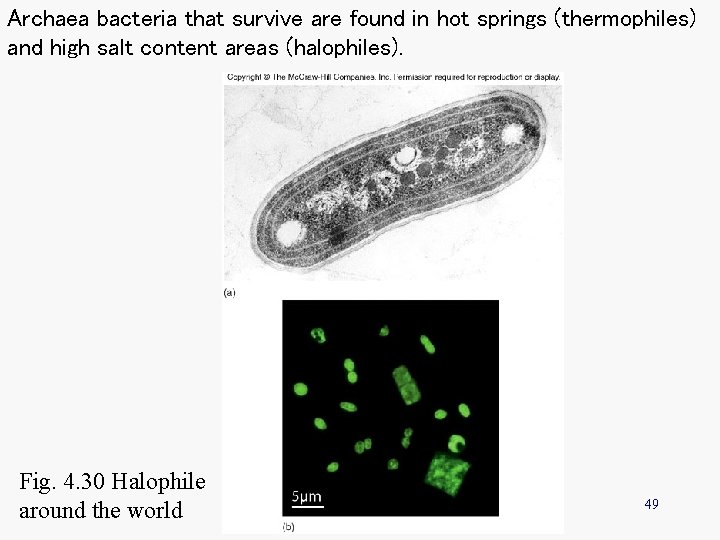

Archaea bacteria that survive are found in hot springs (thermophiles) and high salt content areas (halophiles). Fig. 4. 30 Halophile around the world 49