Chapter 4 Lecture The Atmosphere An Introduction to

- Slides: 45

Chapter 4 Lecture The Atmosphere: An Introduction to Meteorology Thirteenth Edition Moisture and Atmospheric Stability Heather Gallacher Cleveland State University © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

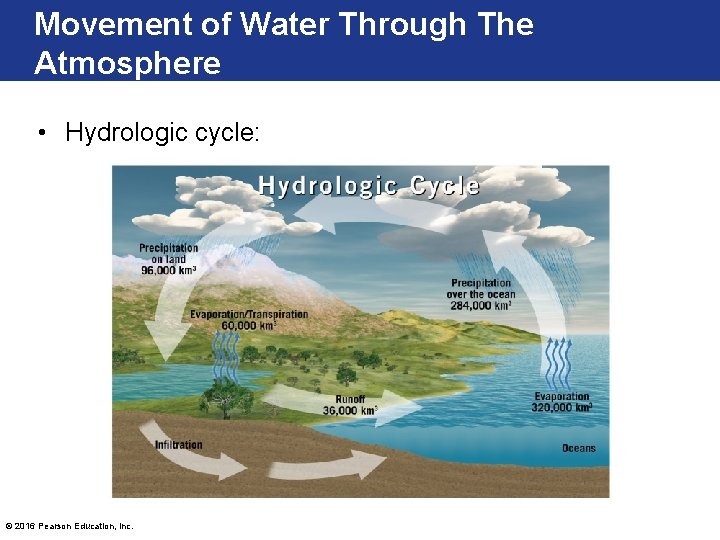

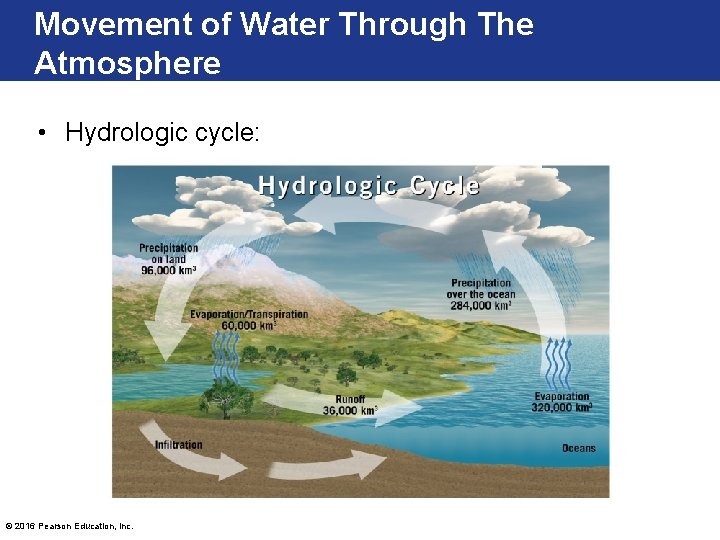

Movement of Water Through The Atmosphere • Hydrologic cycle: © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

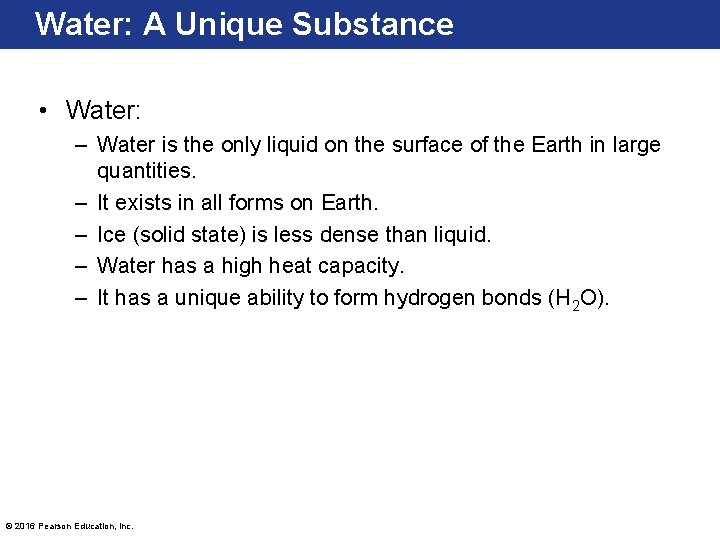

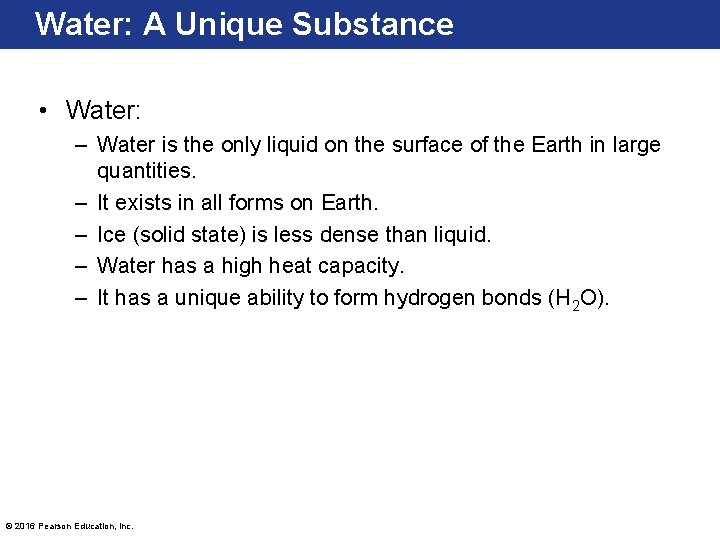

Water: A Unique Substance • Water: – Water is the only liquid on the surface of the Earth in large quantities. – It exists in all forms on Earth. – Ice (solid state) is less dense than liquid. – Water has a high heat capacity. – It has a unique ability to form hydrogen bonds (H 2 O). © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

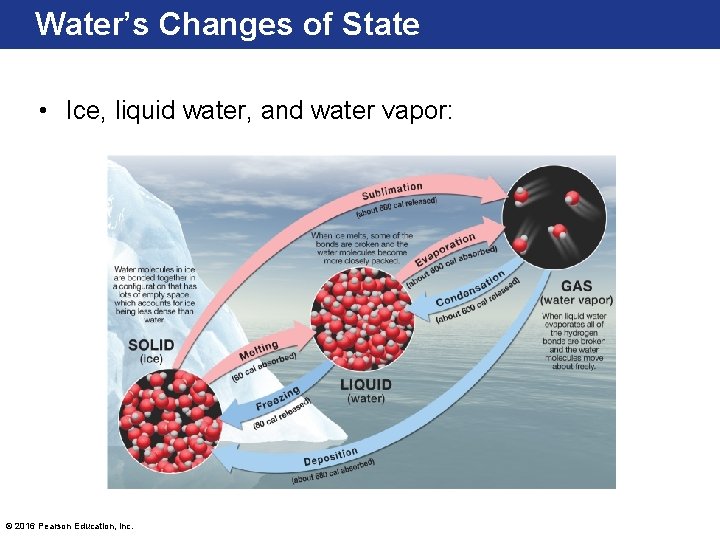

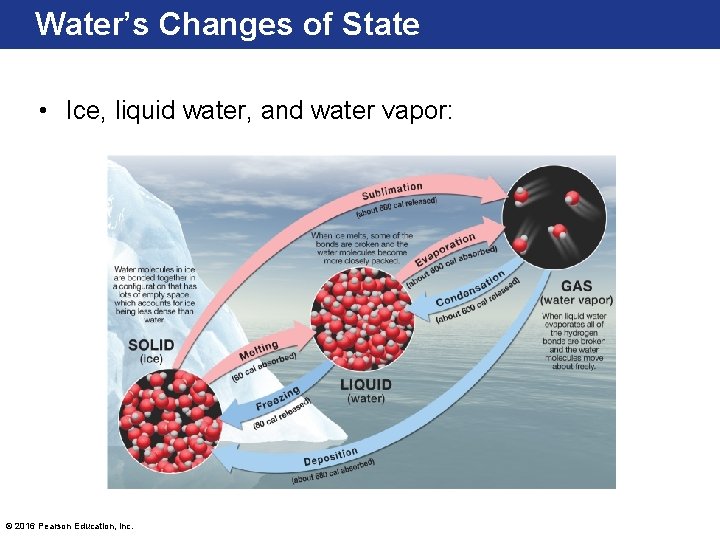

Water’s Changes of State • Ice, liquid water, and water vapor: © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

Latent Heat • Calories are the amount of heat required to raise the temperature of 1 gram of water 1°C. – Thus, when 10 calories of heat are absorbed by 1 gram of water, the molecules vibrate and a 10°C temperature rise occurs. • The energy absorbed or released during a change of state (of matter) is called latent heat. – Note: Temperature of a substance won’t change during a phase change (liquid to gas), but its amount of energy will increase if heat is continually added between phase changes. © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

Latent Heat • Remember: – if energy is required the reaction will use up heat and cause cooling – If energy is released the reaction will give off heat and cause warming • Melting 1 gram of ice requires 80 calories. – Latent heat of melting • Freezing 1 gram of water releases 80 calories. – Latent heat of fusion © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

Latent Heat • Latent heat is also during evaporation, the process of converting a liquid to a gas. – The latent heat of vaporization is the energy absorbed by water during evaporation. • ~ 600 calories/gram for water – Evaporation is a cooling process. • Condensation is the reverse process, converting a gas to a liquid. – The process when water vapor changes to the liquid state is the latent heat of condensation. – Energy is released, which warms the surrounding air. © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

Latent Heat • Sublimation: – Sublimation is the process that turns a solid to a gas • Example: dry ice turning to fog, snowflakes turning to gas on sunny day • Deposition: – Deposition is the reverse process of changing a vapor to a solid, requires a surface to stick to • Example: Frost on a window pane © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

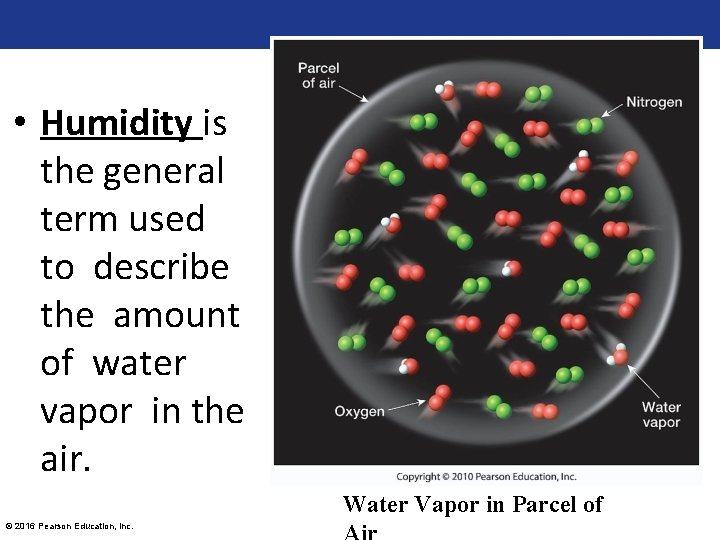

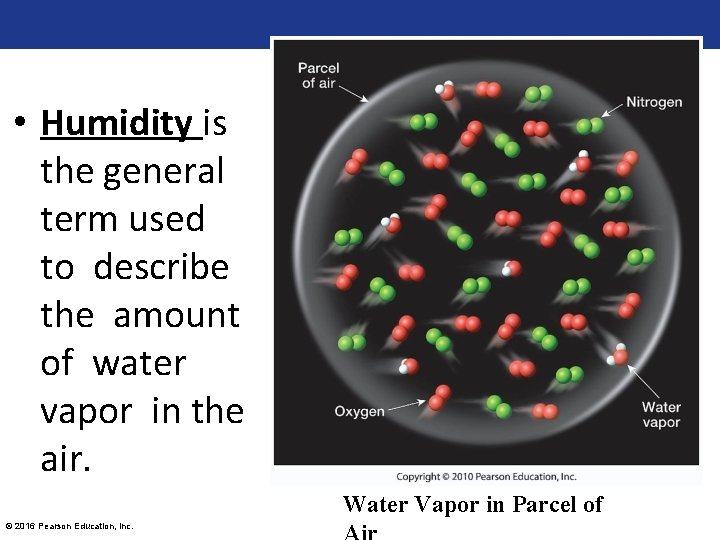

• Humidity is the general term used to describe the amount of water vapor in the air. Water Vapor in Parcel of © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

What % of Air Can Be Made of H 2 O Vapor? The average percentage of water as part of the air at sea level will only be from 1% to 3%, but can be as high as 5%. Which means: Even if the air is “saturated” with water, you’ll never have to worry about drowning in fog! © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

Meteorologists employ several methods to express the water vapor content of the air, including: 1. ) Absolute Humidity • Absolute humidity is the mass of water vapor in a given volume of air. • The formula for absolute humidity: Mass of vapor (grams) Volume of air (cubic meters ) • Since air is constantly moving, and changes in pressure and temperature cause changes in volume, it is difficult to monitor the water-vapor content if the absolute humidity formula is being used. Therefore, it is not used for practical measurement. © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

2. ) Mixing Ratio (Specific Humidity) • The mixing ratio is the mass of water vapor in a unit of air compared to the remaining mass of dry air. • The formula for the mixing ratio: Mass of vapor (grams) Mass of dry air (kilogramsin)units of mass, the mixing ratio is • Since it is measured not affected by changes in pressure or temperature. • Unfortunately, neither absolute humidity nor the mixing ratio can be easily determined by direct sampling. • Therefore, other easily measurable methods are used to express the moisture content of air. © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

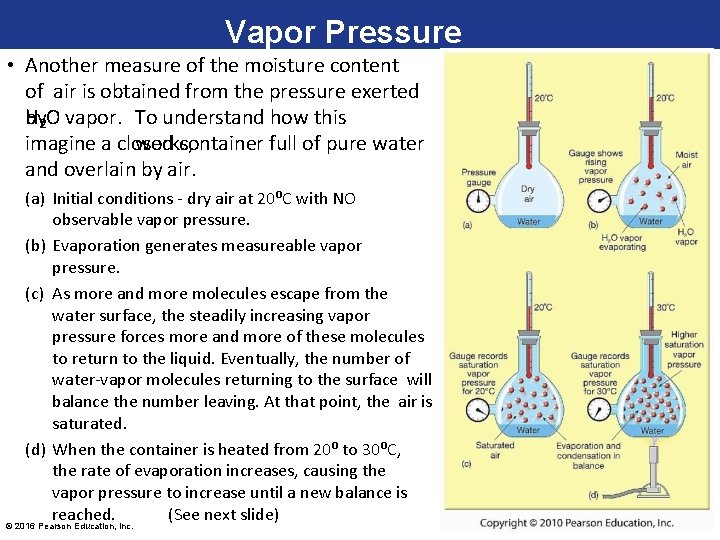

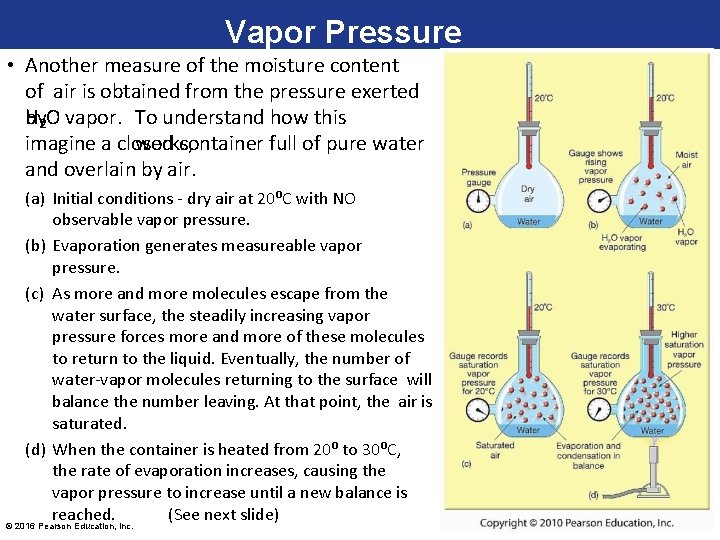

Vapor Pressure • Another measure of the moisture content of air is obtained from the pressure exerted H 2 O vapor. To understand how this by works, imagine a closed container full of pure water and overlain by air. (a) Initial conditions - dry air at 20⁰C with NO observable vapor pressure. (b) Evaporation generates measureable vapor pressure. (c) As more and more molecules escape from the water surface, the steadily increasing vapor pressure forces more and more of these molecules to return to the liquid. Eventually, the number of water-vapor molecules returning to the surface will balance the number leaving. At that point, the air is saturated. (d) When the container is heated from 20⁰ to 30⁰C, the rate of evaporation increases, causing the vapor pressure to increase until a new balance is reached. (See next slide) © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

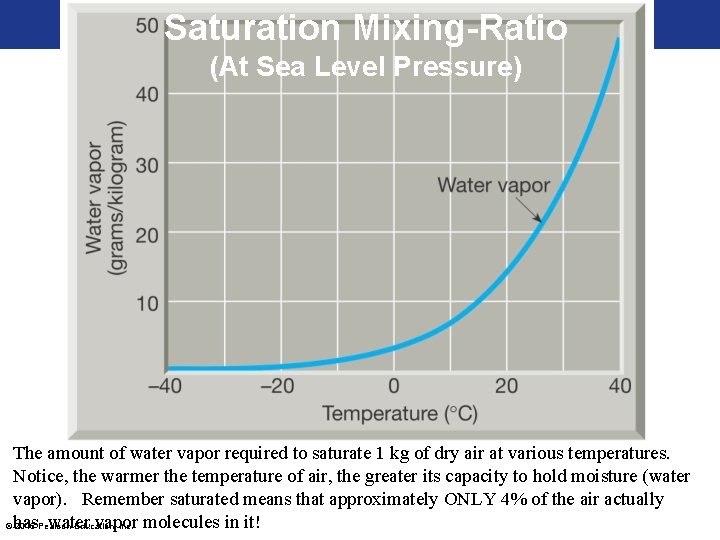

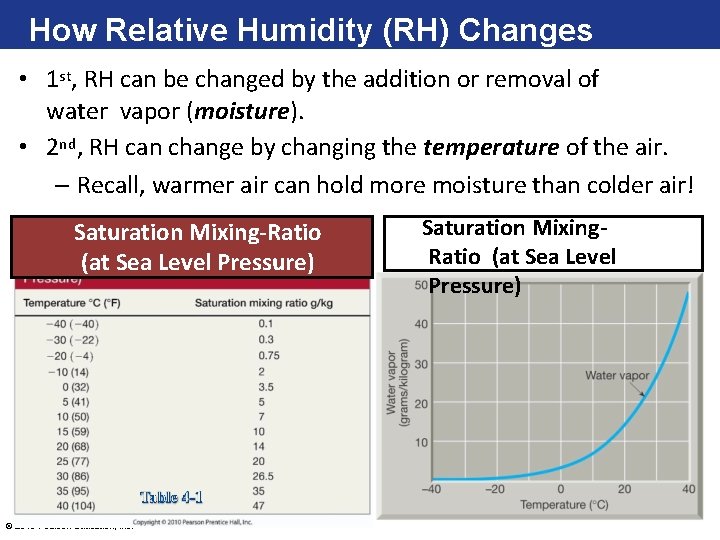

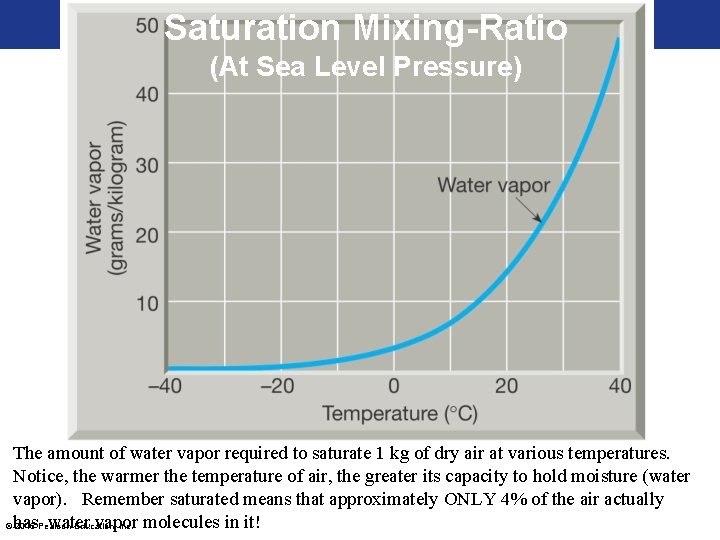

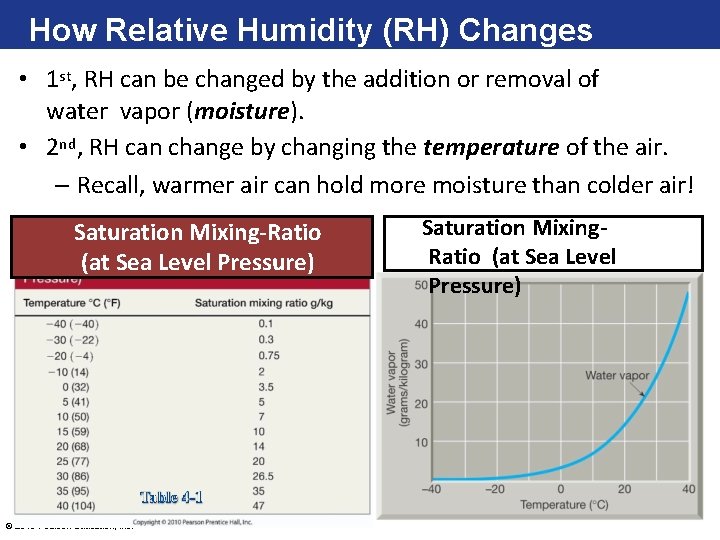

Saturation Mixing-Ratio (At Sea Level Pressure) The amount of water vapor required to saturate 1 kg of dry air at various temperatures. Notice, the warmer the temperature of air, the greater its capacity to hold moisture (water vapor). Remember saturated means that approximately ONLY 4% of the air actually water vapor © has 2016 Pearson Education, Inc. molecules in it!

Relative Humidity • The most familiar and, unfortunately, the most misunderstood term used to describe the moisture content of air is relative humidity. Relative humidity is a ratio of the air’s actual water-vapor content compared with the amount of water vapor required for saturation at that temperature (and pressure). • Thus, relative humidity indicates how near the air is to saturation rather than the actual quantity of water vapor in the air. © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

How Relative Humidity (RH) Changes • 1 st, RH can be changed by the addition or removal of water vapor (moisture). • 2 nd, RH can change by changing the temperature of the air. – Recall, warmer air can hold more moisture than colder air! Saturation Mixing-Ratio (at Sea Level Pressure) © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc. Saturation Mixing. Ratio (at Sea Level Pressure)

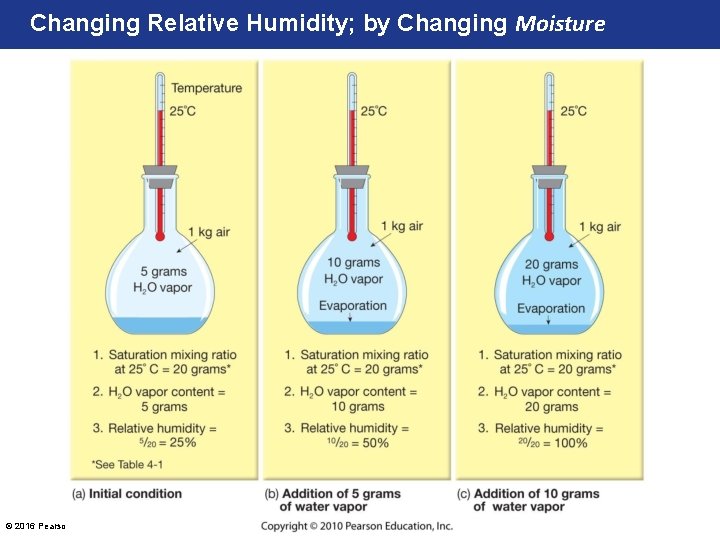

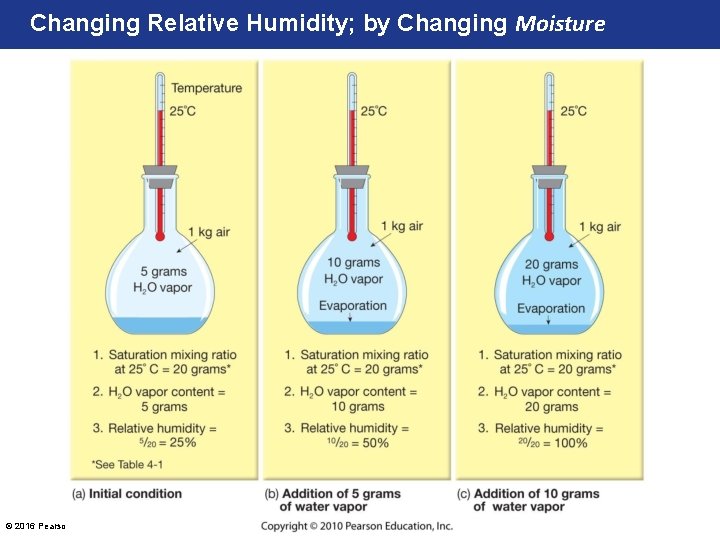

Changing Relative Humidity; by Changing Moisture © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

Changing Relative Humidity: by Changing Temperature Relative Humidity Increases with Decrease of © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

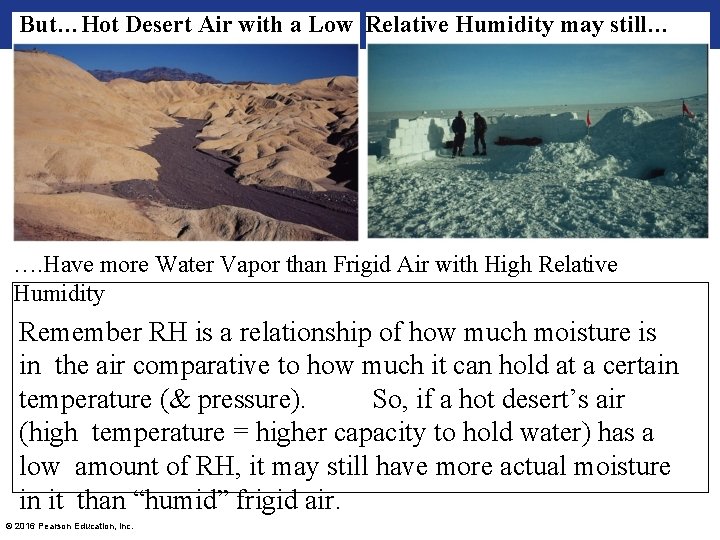

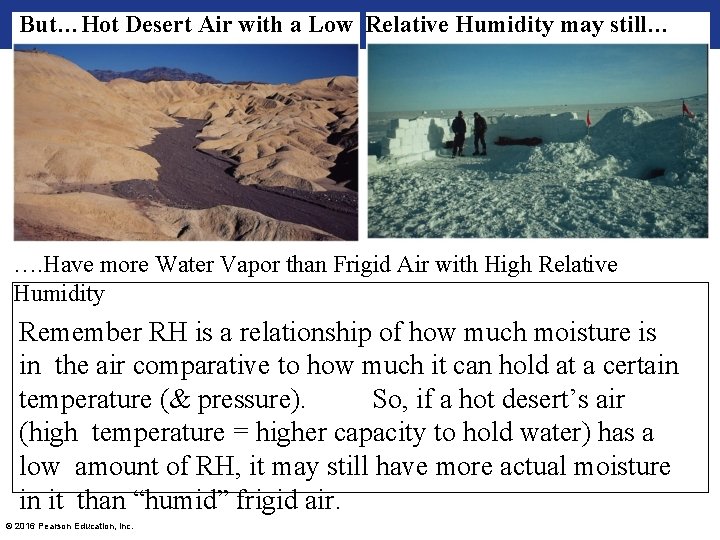

But…Hot Desert Air with a Low Relative Humidity may still… …. Have more Water Vapor than Frigid Air with High Relative Humidity Remember RH is a relationship of how much moisture is in the air comparative to how much it can hold at a certain temperature (& pressure). So, if a hot desert’s air (high temperature = higher capacity to hold water) has a low amount of RH, it may still have more actual moisture in it than “humid” frigid air. © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

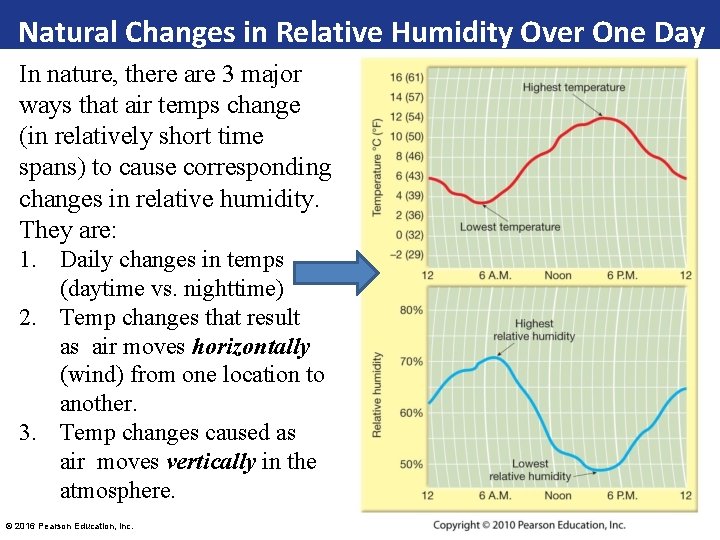

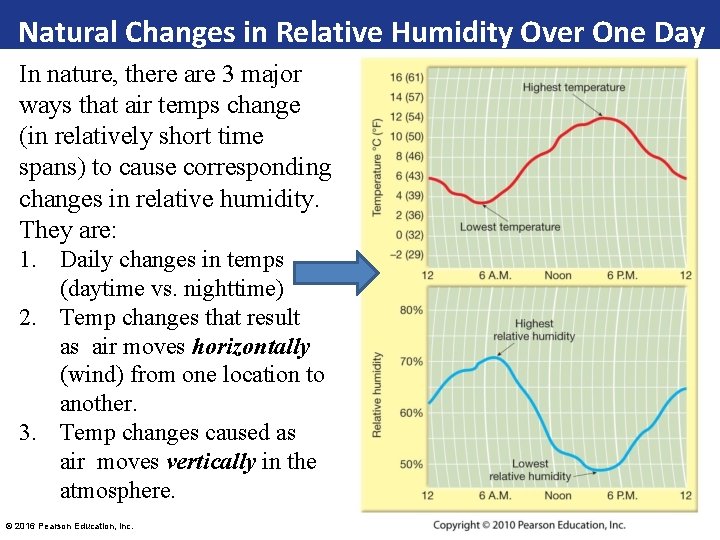

Natural Changes in Relative Humidity Over One Day In nature, there are 3 major ways that air temps change (in relatively short time spans) to cause corresponding changes in relative humidity. They are: 1. Daily changes in temps (daytime vs. nighttime) 2. Temp changes that result as air moves horizontally (wind) from one location to another. 3. Temp changes caused as air moves vertically in the atmosphere. © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

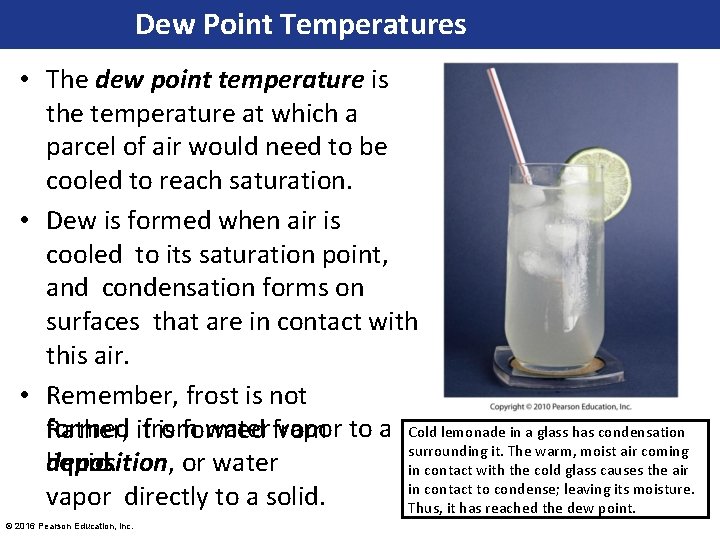

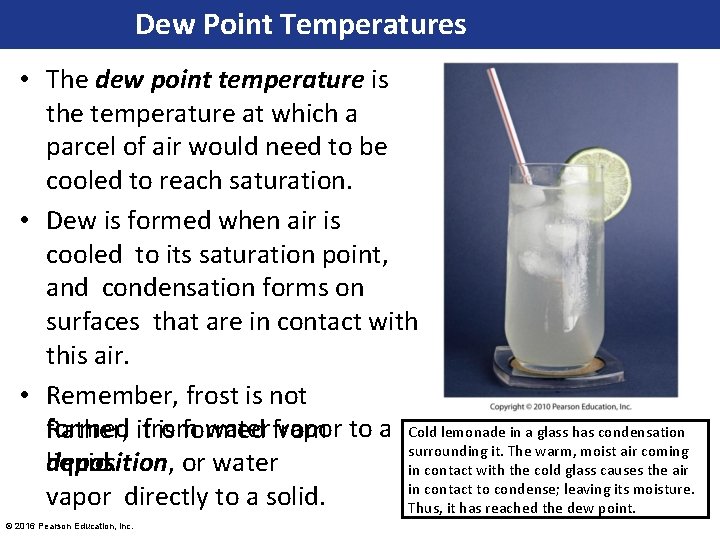

Dew Point Temperatures • The dew point temperature is the temperature at which a parcel of air would need to be cooled to reach saturation. • Dew is formed when air is cooled to its saturation point, and condensation forms on surfaces that are in contact with this air. • Remember, frost is not formed water from vapor to a Cold lemonade in a glass has condensation Rather, itfrom is formed surrounding it. The warm, moist air coming liquid. deposition, or water in contact with the cold glass causes the air in contact to condense; leaving its moisture. vapor directly to a solid. Thus, it has reached the dew point. © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

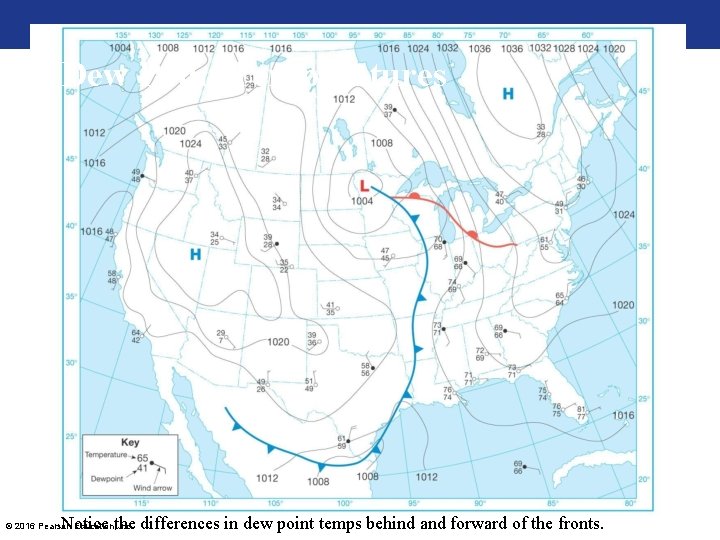

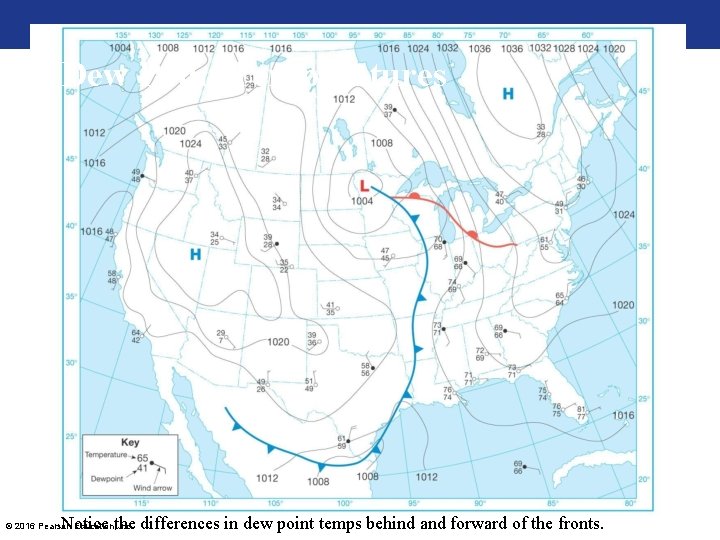

Dew Point Temperatures Notice the differences in dew point temps behind and forward of the fronts. © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

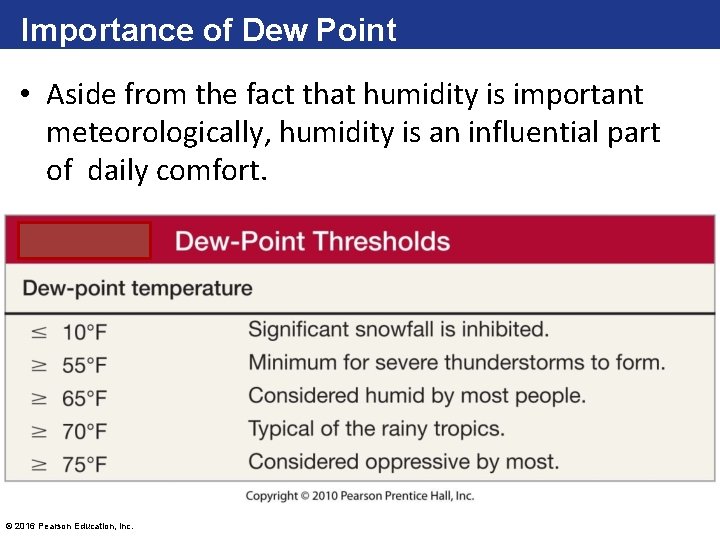

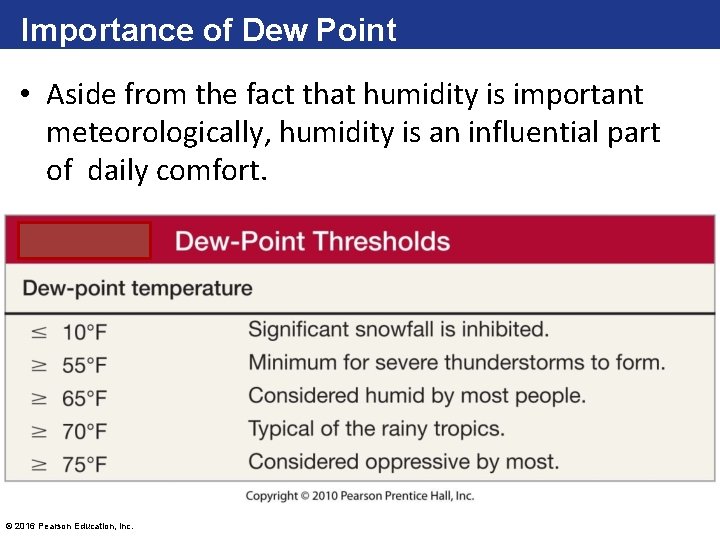

Importance of Dew Point • Aside from the fact that humidity is important meteorologically, humidity is an influential part of daily comfort. © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

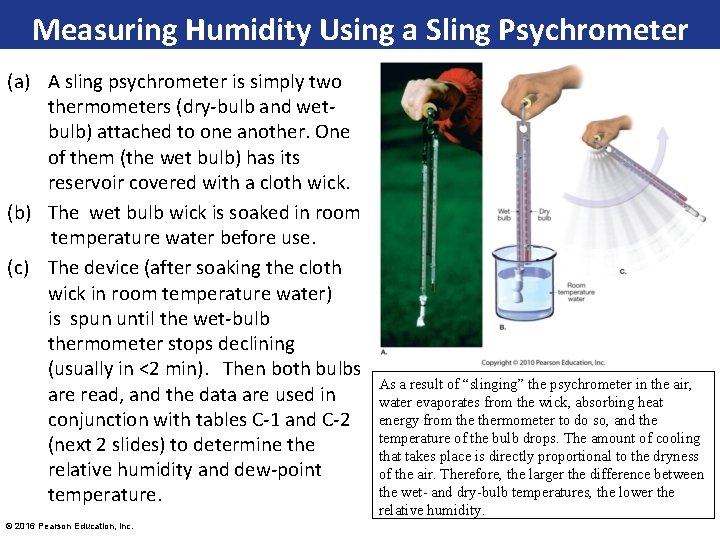

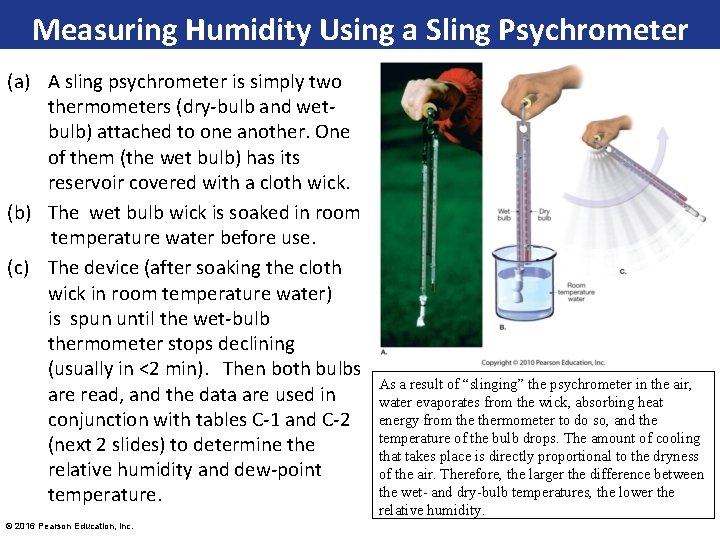

Measuring Humidity Using a Sling Psychrometer (a) A sling psychrometer is simply two thermometers (dry-bulb and wetbulb) attached to one another. One of them (the wet bulb) has its reservoir covered with a cloth wick. (b) The wet bulb wick is soaked in room temperature water before use. (c) The device (after soaking the cloth wick in room temperature water) is spun until the wet-bulb thermometer stops declining (usually in <2 min). Then both bulbs are read, and the data are used in conjunction with tables C-1 and C-2 (next 2 slides) to determine the relative humidity and dew-point temperature. © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc. As a result of “slinging” the psychrometer in the air, water evaporates from the wick, absorbing heat energy from thermometer to do so, and the temperature of the bulb drops. The amount of cooling that takes place is directly proportional to the dryness of the air. Therefore, the larger the difference between the wet- and dry-bulb temperatures, the lower the relative humidity.

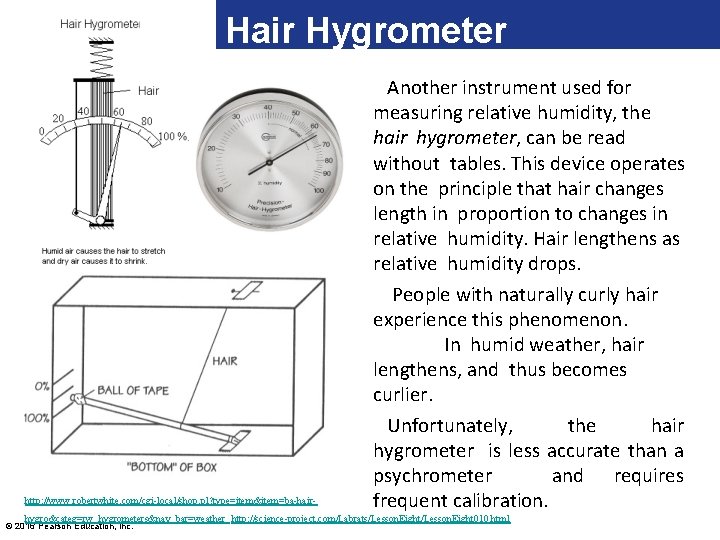

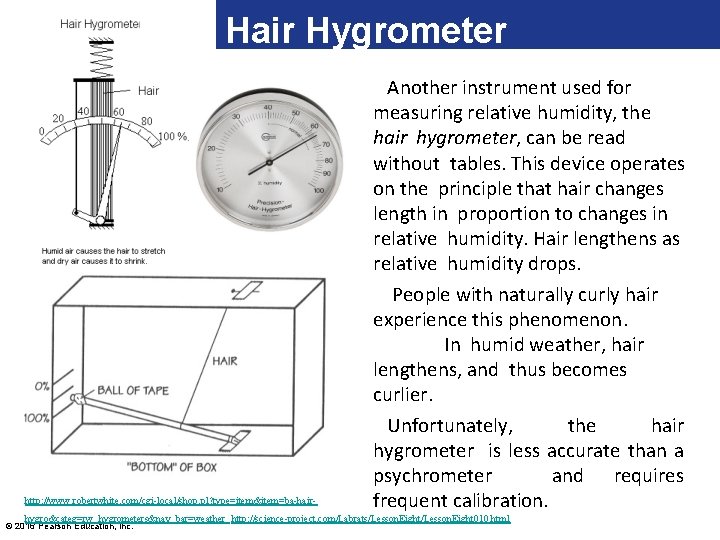

The Hair Hygrometer http: //www. robertwhite. com/cgi-local/shop. pl? type=item&item=ba-hair- Another instrument used for measuring relative humidity, the hair hygrometer, can be read without tables. This device operates on the principle that hair changes length in proportion to changes in relative humidity. Hair lengthens as relative humidity drops. People with naturally curly hair experience this phenomenon. In humid weather, hair lengthens, and thus becomes curlier. Unfortunately, the hair hygrometer is less accurate than a psychrometer and requires frequent calibration. hygro&categ=rw_hygrometers&nav_bar=weather http: //science-project. com/Labrats/Lesson. Eight 010. html © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

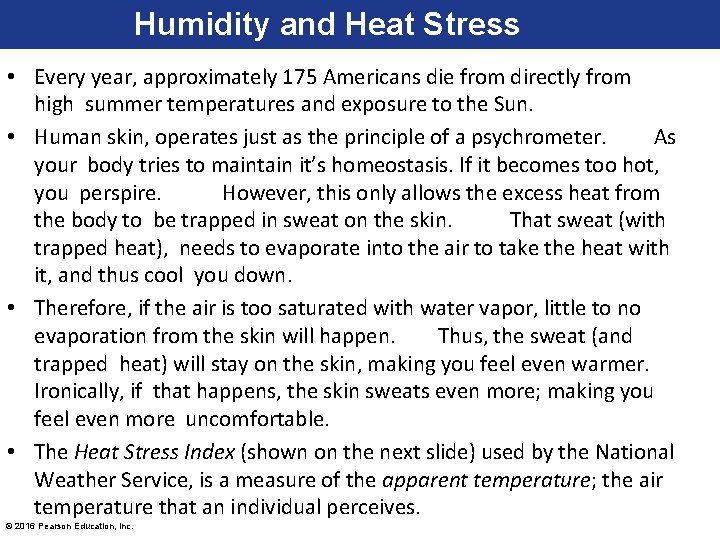

Humidity and Heat Stress • Every year, approximately 175 Americans die from directly from high summer temperatures and exposure to the Sun. • Human skin, operates just as the principle of a psychrometer. As your body tries to maintain it’s homeostasis. If it becomes too hot, you perspire. However, this only allows the excess heat from the body to be trapped in sweat on the skin. That sweat (with trapped heat), needs to evaporate into the air to take the heat with it, and thus cool you down. • Therefore, if the air is too saturated with water vapor, little to no evaporation from the skin will happen. Thus, the sweat (and trapped heat) will stay on the skin, making you feel even warmer. Ironically, if that happens, the skin sweats even more; making you feel even more uncomfortable. • The Heat Stress Index (shown on the next slide) used by the National Weather Service, is a measure of the apparent temperature; the air temperature that an individual perceives. © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

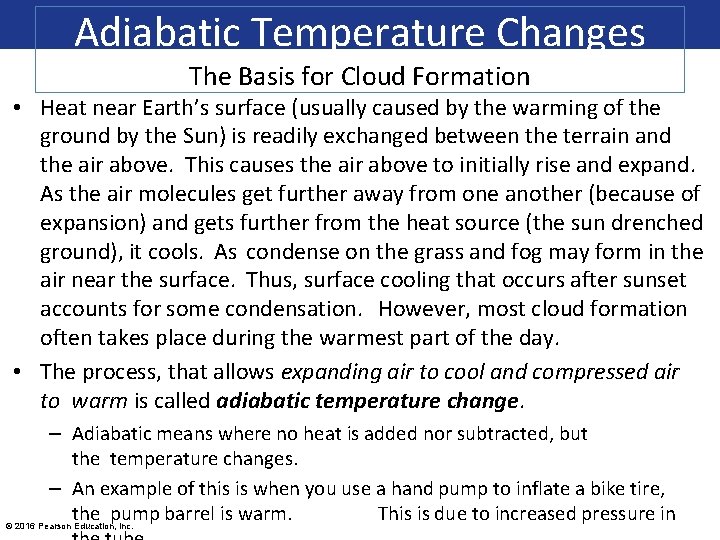

Adiabatic Temperature Changes The Basis for Cloud Formation • Heat near Earth’s surface (usually caused by the warming of the ground by the Sun) is readily exchanged between the terrain and the air above. This causes the air above to initially rise and expand. As the air molecules get further away from one another (because of expansion) and gets further from the heat source (the sun drenched ground), it cools. As condense on the grass and fog may form in the air near the surface. Thus, surface cooling that occurs after sunset accounts for some condensation. However, most cloud formation often takes place during the warmest part of the day. • The process, that allows expanding air to cool and compressed air to warm is called adiabatic temperature change. – Adiabatic means where no heat is added nor subtracted, but the temperature changes. – An example of this is when you use a hand pump to inflate a bike tire, the pump barrel is warm. This is due to increased pressure in © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

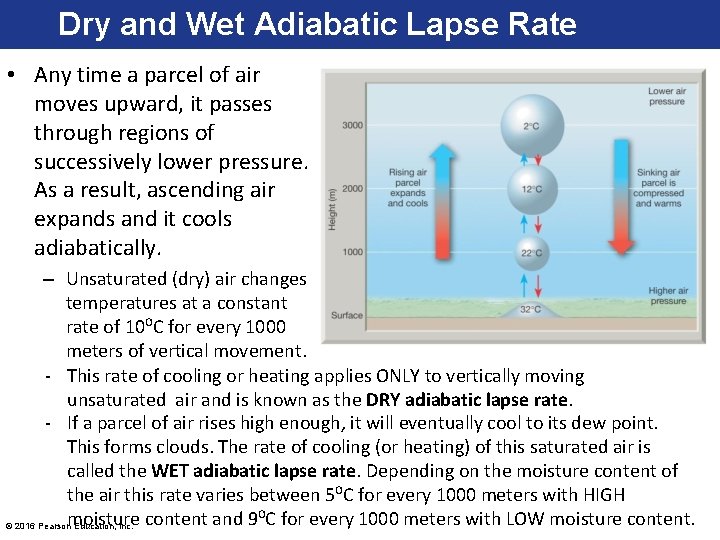

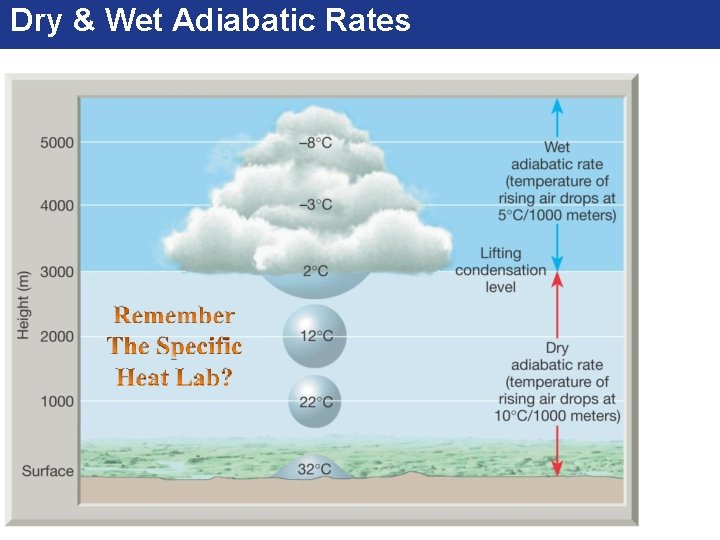

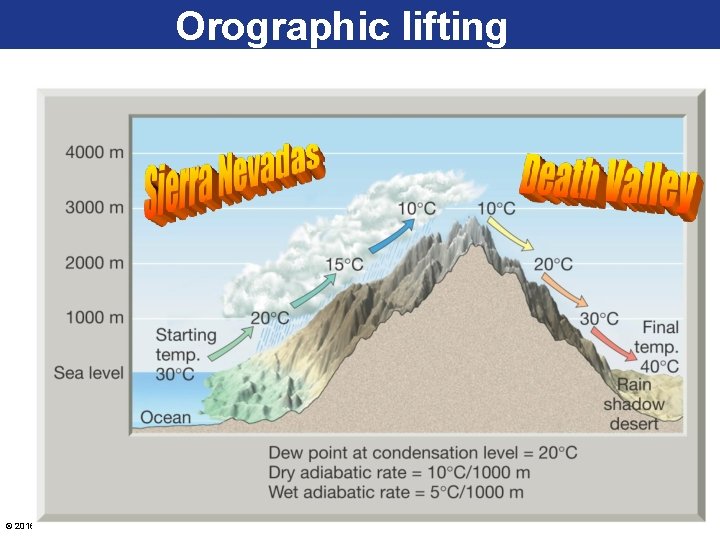

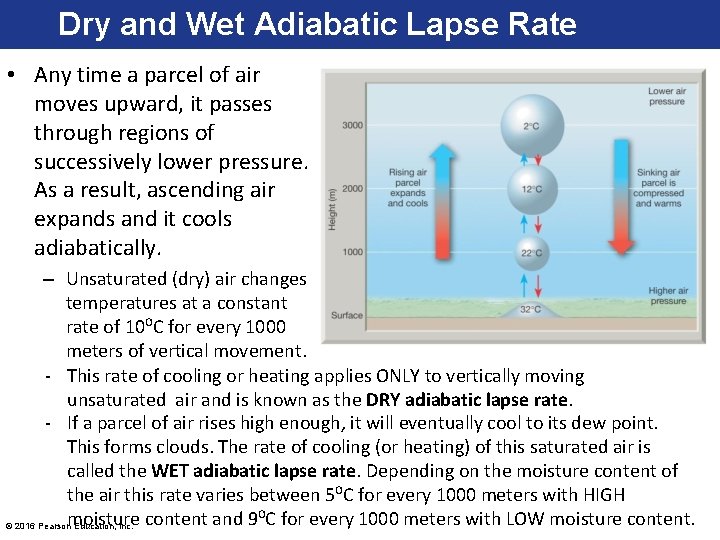

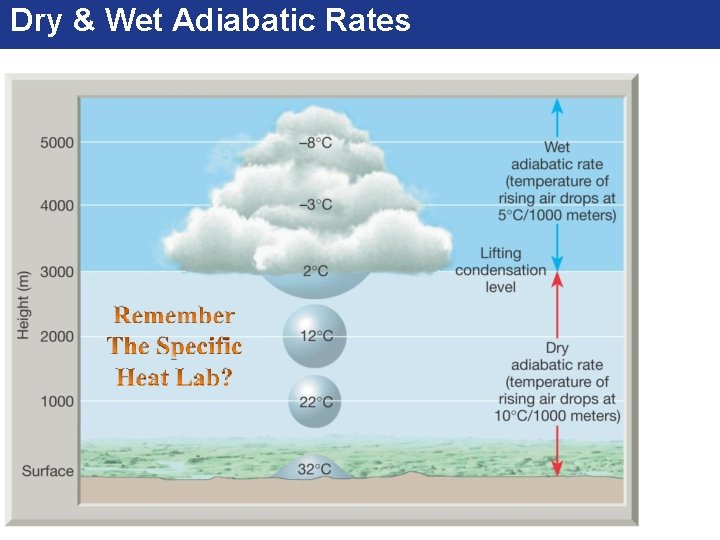

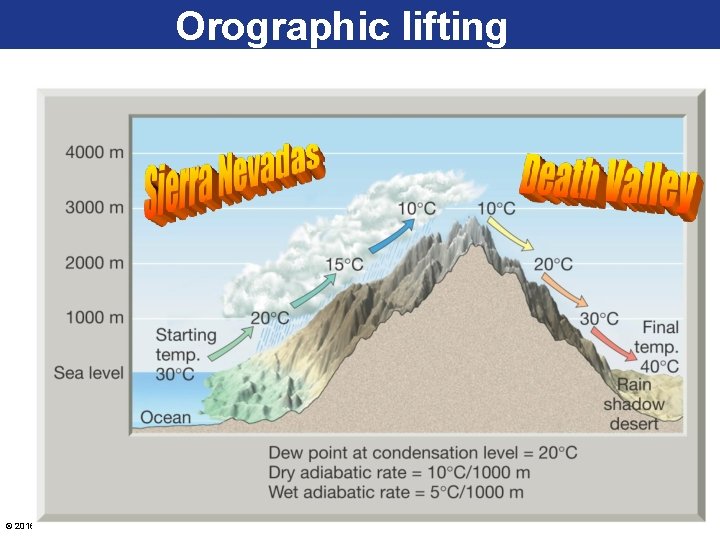

Dry and Wet Adiabatic Lapse Rate • Any time a parcel of air moves upward, it passes through regions of successively lower pressure. As a result, ascending air expands and it cools adiabatically. – Unsaturated (dry) air changes temperatures at a constant rate of 10⁰C for every 1000 meters of vertical movement. - This rate of cooling or heating applies ONLY to vertically moving unsaturated air and is known as the DRY adiabatic lapse rate. - If a parcel of air rises high enough, it will eventually cool to its dew point. This forms clouds. The rate of cooling (or heating) of this saturated air is called the WET adiabatic lapse rate. Depending on the moisture content of the air this rate varies between 5⁰C for every 1000 meters with HIGH © 2016 Pearsonmoisture Education, Inc. content and 9⁰C for every 1000 meters with LOW moisture content.

Dry & Wet Adiabatic Rates © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

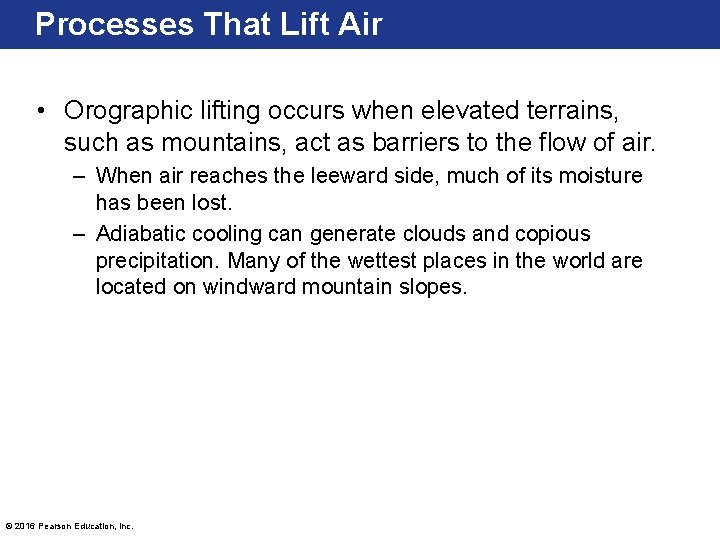

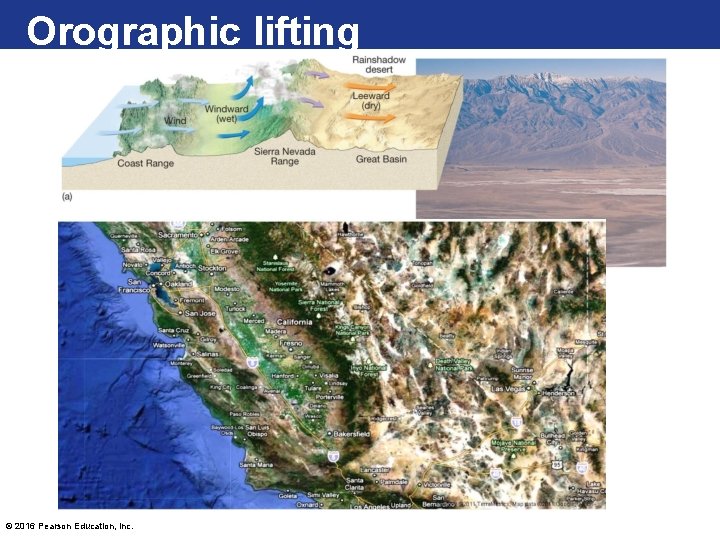

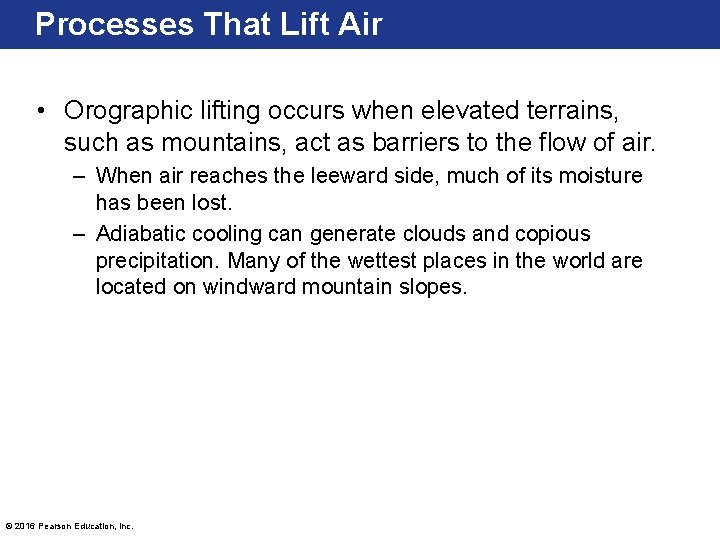

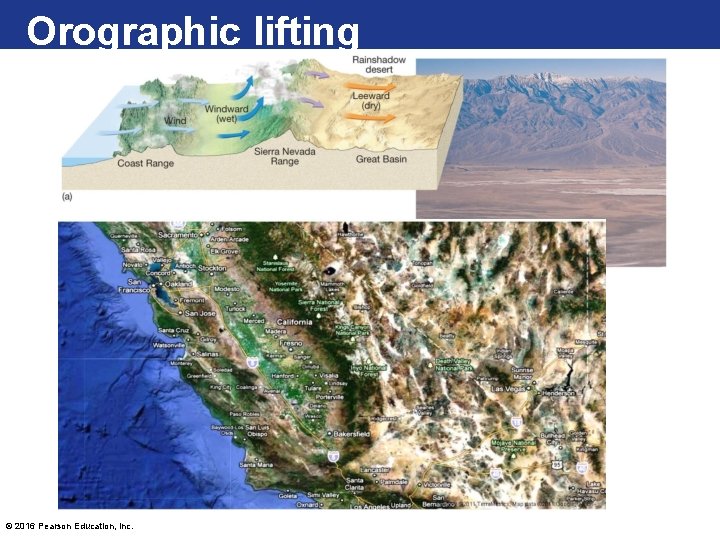

Processes That Lift Air • Orographic lifting occurs when elevated terrains, such as mountains, act as barriers to the flow of air. – When air reaches the leeward side, much of its moisture has been lost. – Adiabatic cooling can generate clouds and copious precipitation. Many of the wettest places in the world are located on windward mountain slopes. © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

Orographic lifting © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

Orographic lifting © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

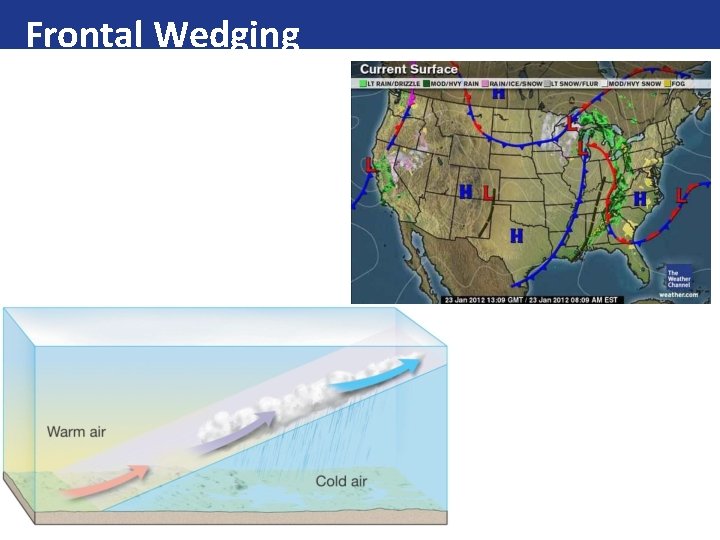

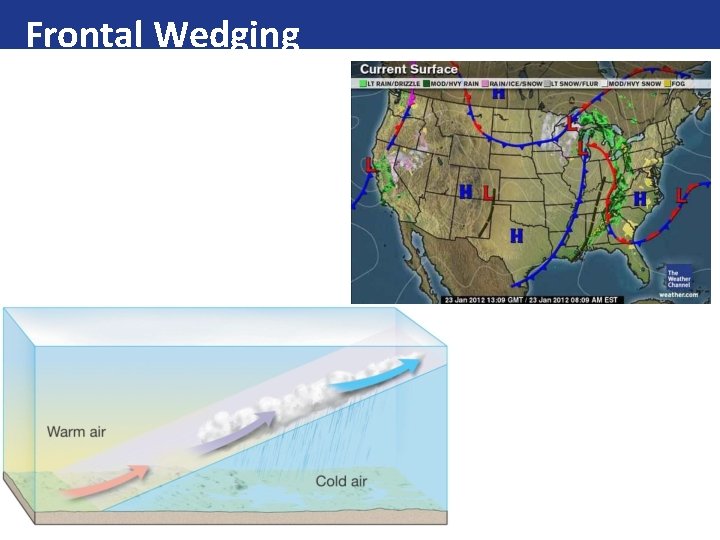

Frontal Wedging © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

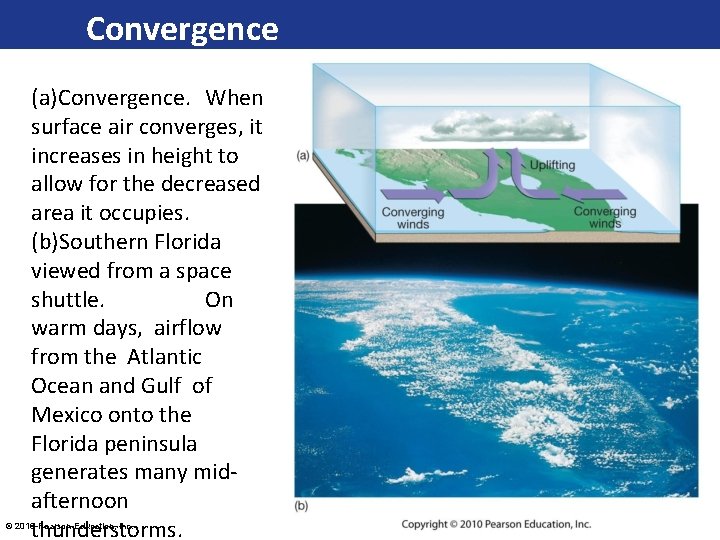

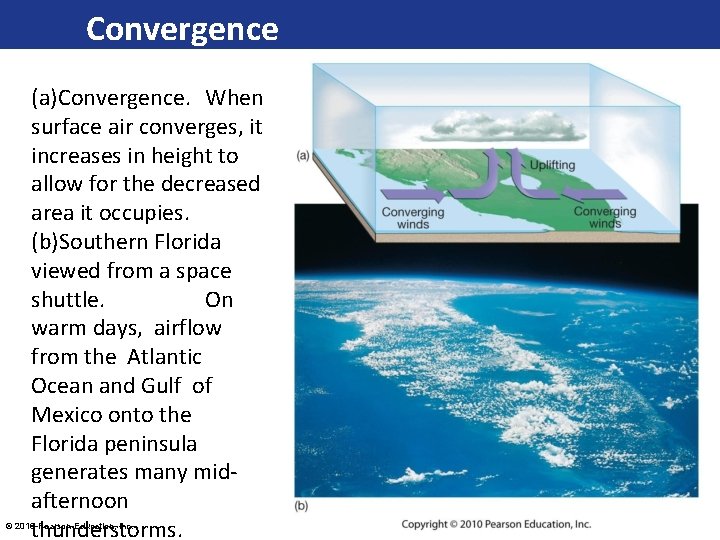

Convergence (a)Convergence. When surface air converges, it increases in height to allow for the decreased area it occupies. (b)Southern Florida viewed from a space shuttle. On warm days, airflow from the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico onto the Florida peninsula generates many midafternoon thunderstorms. © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

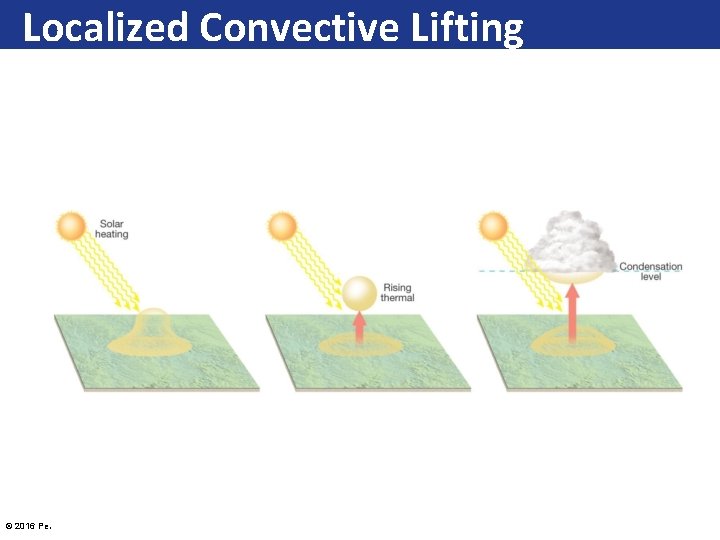

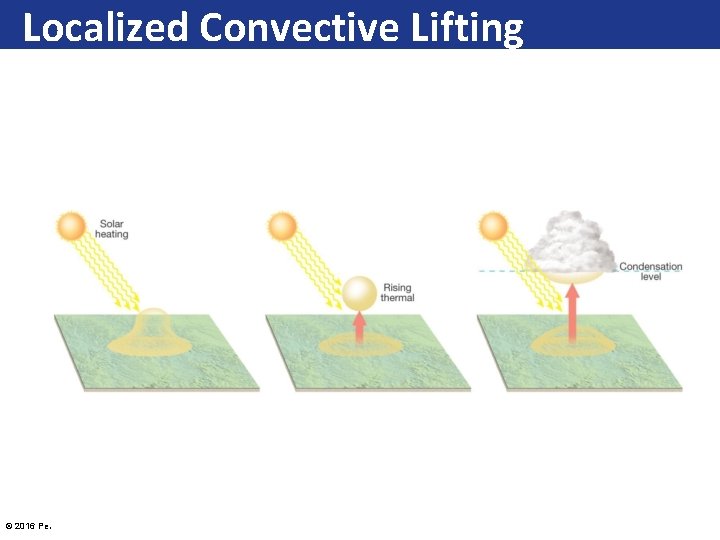

Localized Convective Lifting © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

The Critical Weather Maker: Atmospheric Stability © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

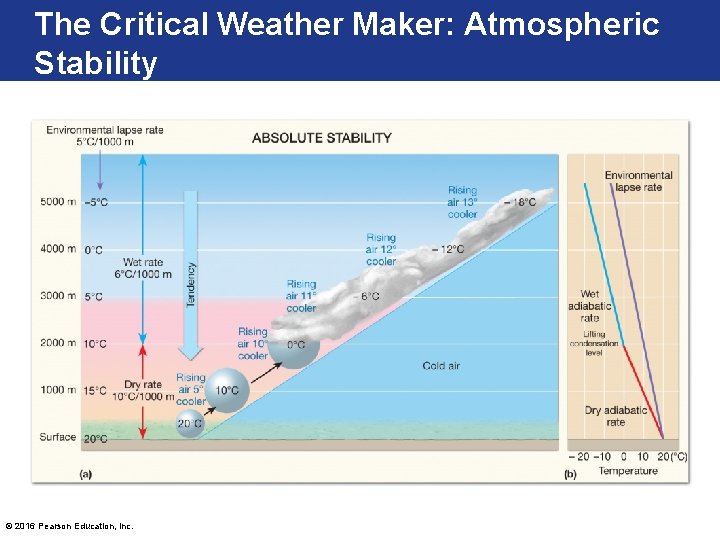

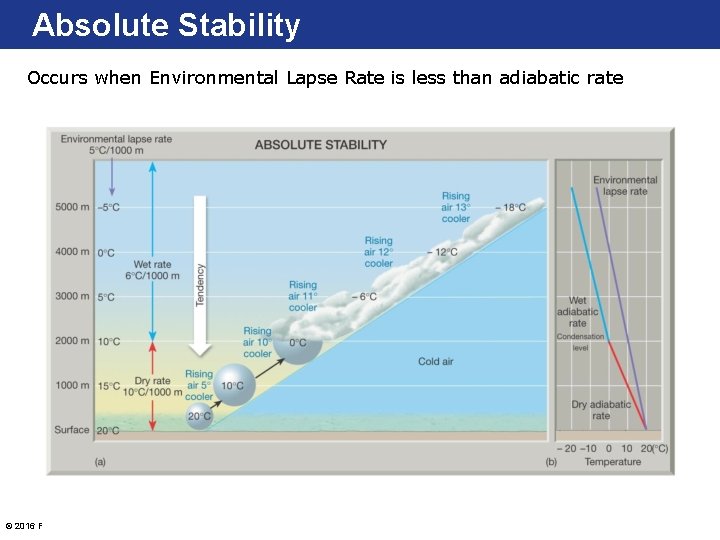

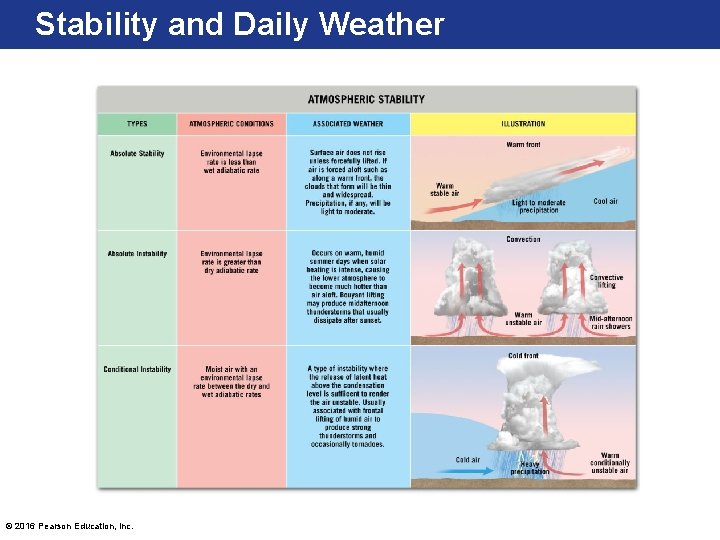

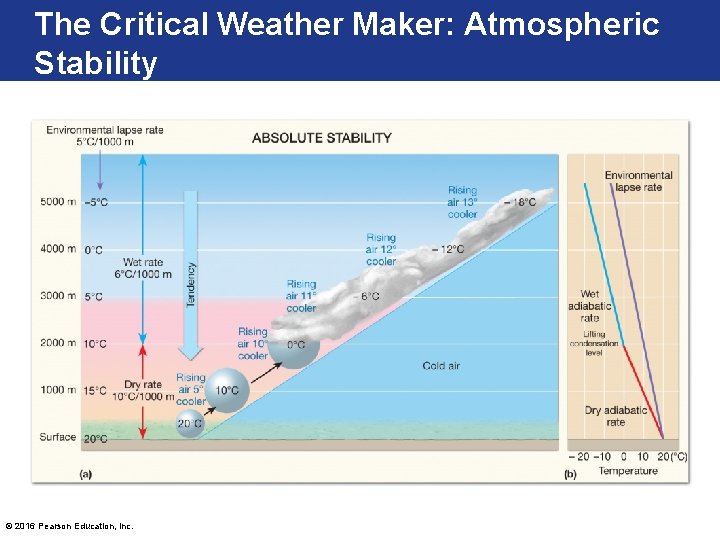

The Critical Weathermaker: Atmospheric Stability • Stable Air- air that resists vertical distribution of atmospheric pressure (as well as temperature and density), which is taken to represent average conditions in the real atmosphere. • Unstable Air - air that does NOT resist vertical displacement. • If it is lifted, its temperature will not cool as rapidly as the surrounding environment and so it will continue to rise on its own. • Environmental Lapse Rate: the rate of temperature decrease with height in the troposphere. • Typically equivalent to -5°C per increase of every 1000 meter rise. © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

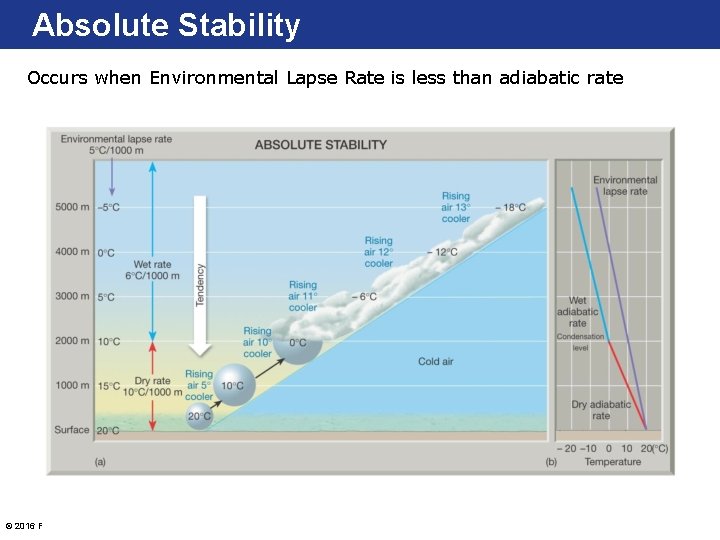

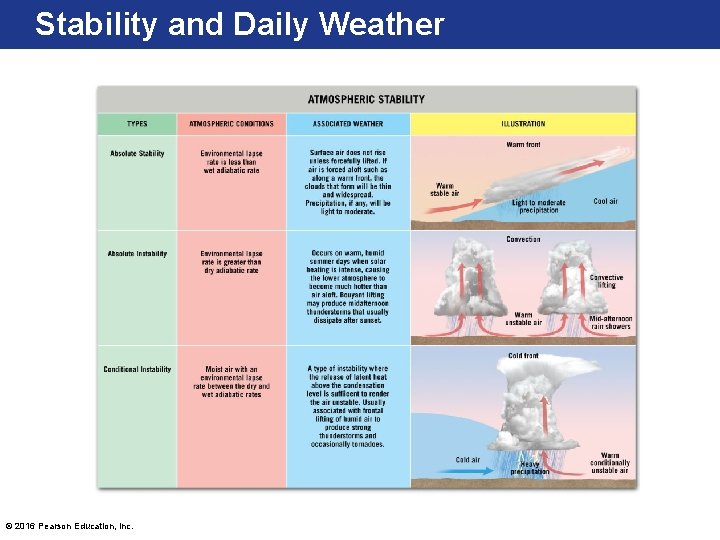

Absolute Stability Occurs when Environmental Lapse Rate is less than adiabatic rate © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

Stability and Daily Weather • How stability changes: – Stability is enhanced by the following: • Radiation cooling of Earth’s surface after sunset • Cooling of an air mass from below as it traverses cold surfaces • General subsidence within an air column © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

The Critical Weather Maker: Atmospheric Stability Occurs when Environmental Lapse Rate is greater than adiabatic rate © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

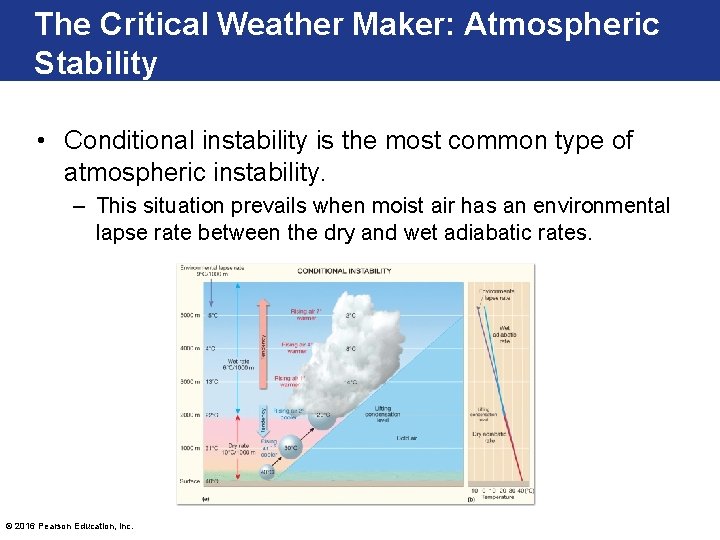

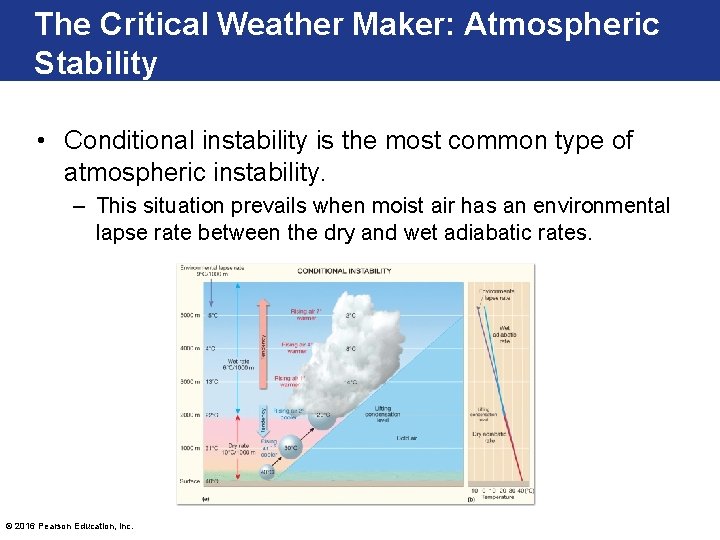

The Critical Weather Maker: Atmospheric Stability • Conditional instability is the most common type of atmospheric instability. – This situation prevails when moist air has an environmental lapse rate between the dry and wet adiabatic rates. © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

Stability and Daily Weather • How stability changes: – Instability is enhanced by the following: • Intense warming of the lowest layer of the atmosphere • Heating of an air mass from below • General upward movement of air caused by orographic lifting, frontal wedging, and convergence • Radiation cooling from cloud tops © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

Stability and Daily Weather • Temperature changes and stability: – When air is cooled from below, it becomes more stable, often producing widespread fog. – In winter, air is rendered sufficiently unstable when cold, dry air passes over a warm, wet surface, which can often produce lake effect snow over the Great Lakes. © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

Stability and Daily Weather © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

Vertical Air Movement and Stability • Subsidence is a general, downward air flow. – Usually, surface air is not involved. – This results with stable air and clear, blue, cloudless skies. © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc.