Chapter 3 Writing Functions in Assembly Part 1

Chapter 3 Writing Functions in Assembly Part 1: Embedded Application Development

Approach • Most of a program is written in a high-level language (HLL) such as C – easier to implement – easier to understand – easier to maintain • Only a few functions are written in assembly – to improve performance, or – because it’s difficult or impossible to do in a HLL.

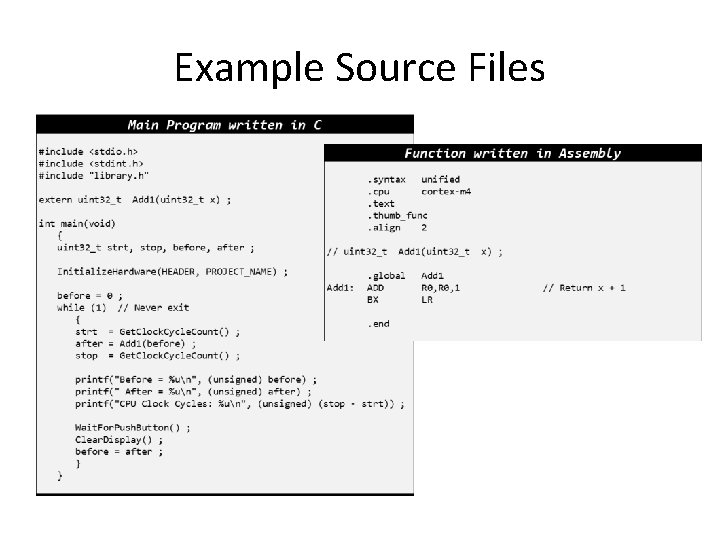

Example Source Files

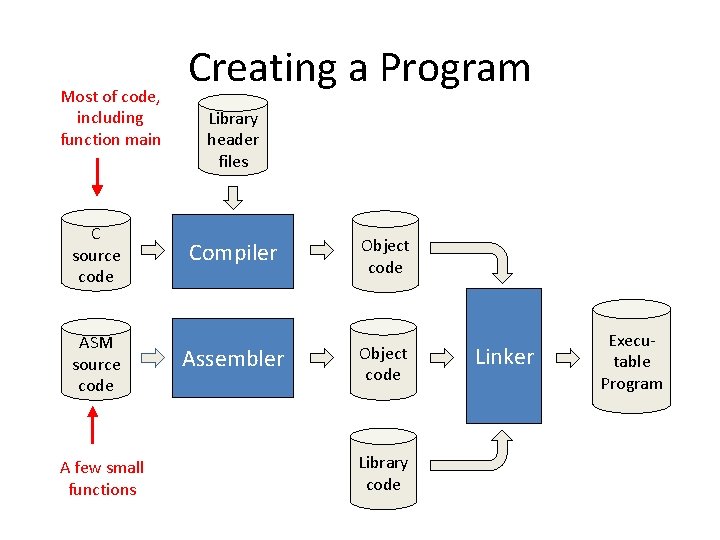

Most of code, including function main C source code ASM source code A few small functions Creating a Program Library header files Compiler Object code Assembler Object code Library code Linker Executable Program

Consequence Assembly functions must be compatible with instructions generated by the C compiler to … 1. 2. 3. 4. Call a function Pass parameters Receive return value Use CPU registers

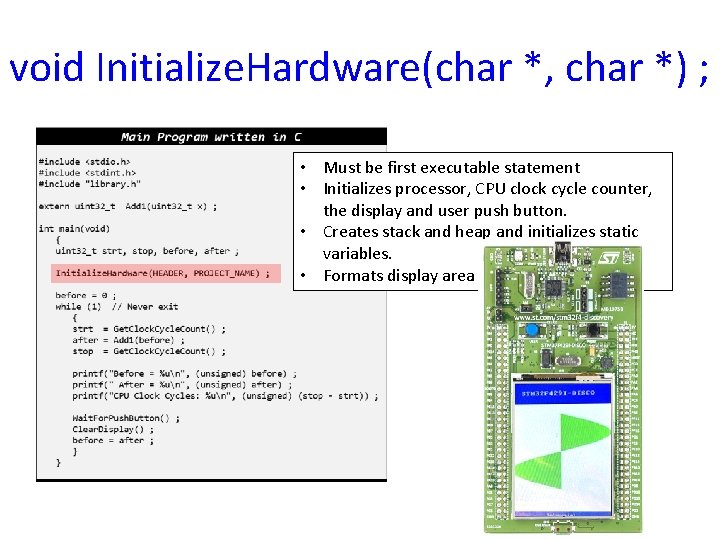

void Initialize. Hardware(char *, char *) ; • Must be first executable statement • Initializes processor, CPU clock cycle counter, the display and user push button. • Creates stack and heap and initializes static variables. • Formats display area

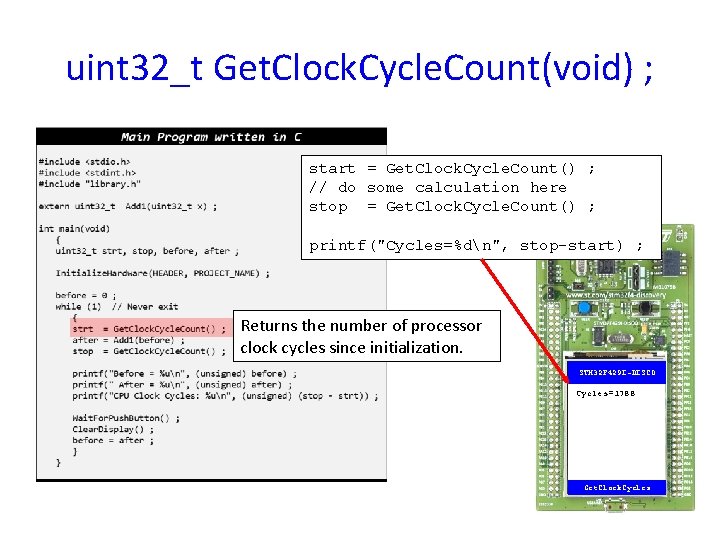

uint 32_t Get. Clock. Cycle. Count(void) ; start = Get. Clock. Cycle. Count() ; // do some calculation here stop = Get. Clock. Cycle. Count() ; printf("Cycles=%dn", stop-start) ; Returns the number of processor clock cycles since initialization. STM 32 F 429 I-DISCO Cycles=1788 Get. Clock. Cycles

void Wait. For. Push. Button(void) ; Causes program to pause and wait for user to push the blue push button on the board.

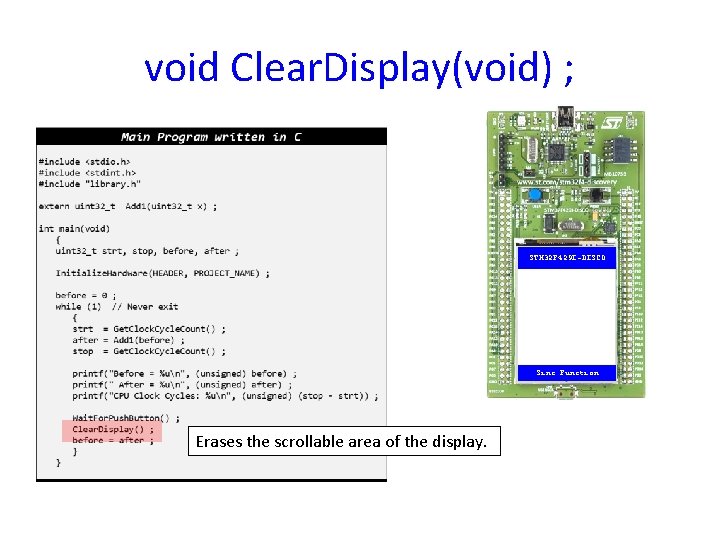

void Clear. Display(void) ; STM 32 F 429 I-DISCO Sine Function Erases the scrollable area of the display.

Chapter 3 Writing Functions in Assembly Part 2: Function Call and Return

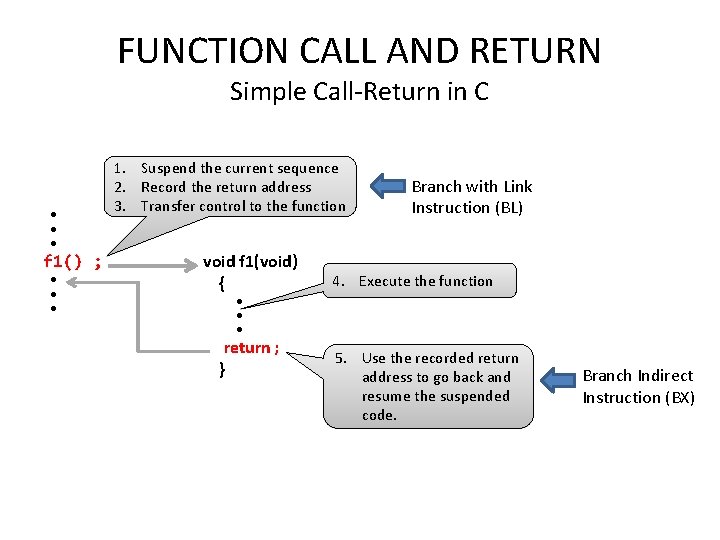

FUNCTION CALL AND RETURN Simple Call-Return in C ● ● ● f 1() ; ● ● ● 1. Suspend the current sequence 2. Record the return address 3. Transfer control to the function void f 1(void) { Branch with Link Instruction (BL) 4. Execute the function ● ● ● return ; } 5. Use the recorded return address to go back and resume the suspended code. Branch Indirect Instruction (BX)

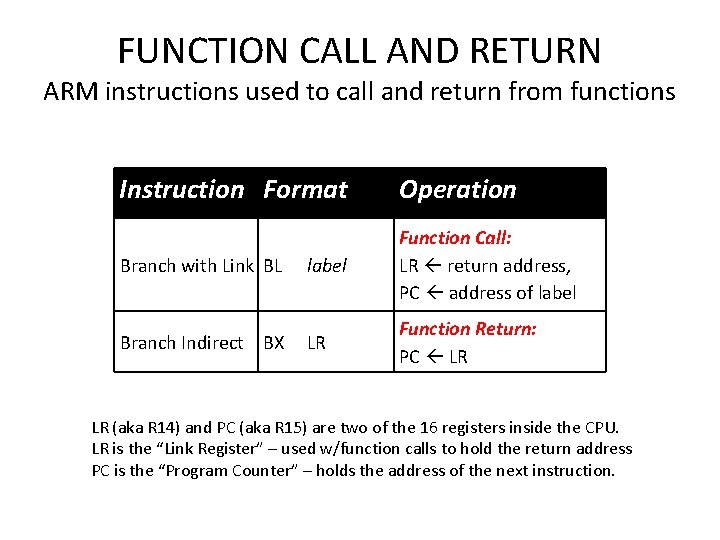

FUNCTION CALL AND RETURN ARM instructions used to call and return from functions Instruction Format Operation Branch with Link BL label Function Call: LR return address, PC address of label LR Function Return: PC LR Branch Indirect BX LR (aka R 14) and PC (aka R 15) are two of the 16 registers inside the CPU. LR is the “Link Register” – used w/function calls to hold the return address PC is the “Program Counter” – holds the address of the next instruction.

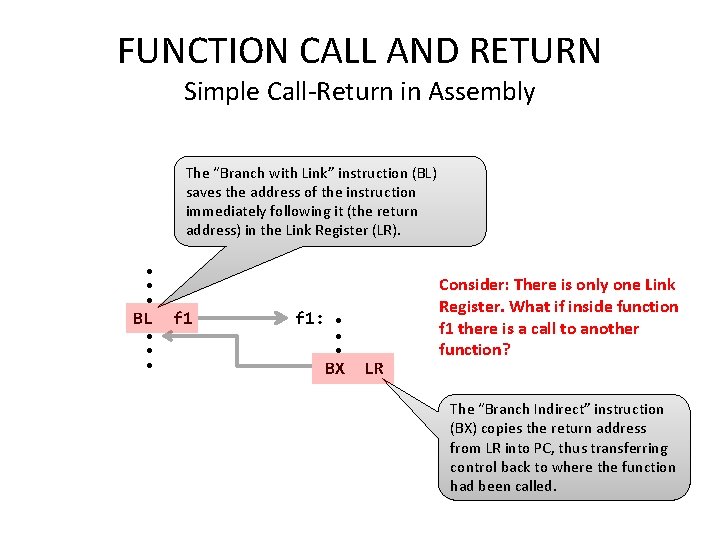

FUNCTION CALL AND RETURN Simple Call-Return in Assembly The “Branch with Link” instruction (BL) saves the address of the instruction immediately following it (the return address) in the Link Register (LR). ● ● ● BL ● ● ● f 1: ● ● ● BX LR Consider: There is only one Link Register. What if inside function f 1 there is a call to another function? The “Branch Indirect” instruction (BX) copies the return address from LR into PC, thus transferring control back to where the function had been called.

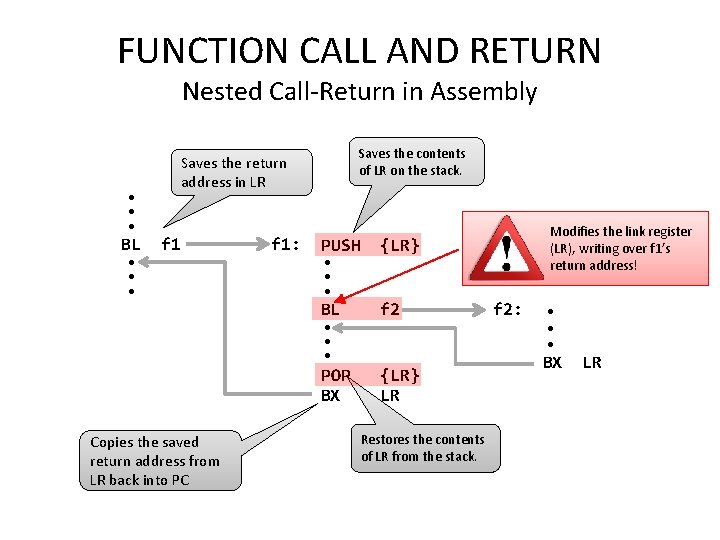

FUNCTION CALL AND RETURN Nested Call-Return in Assembly ● ● ● BL Saves the contents of LR on the stack. Saves the return address in LR f 1 ● ● ● f 1: PUSH {LR} BL f 2 ● ● ● POP BX Copies the saved return address from LR back into PC {LR} LR Restores the contents of LR from the stack. Modifies the link register (LR), writing over f 1’s return address! f 2: ● ● ● BX LR

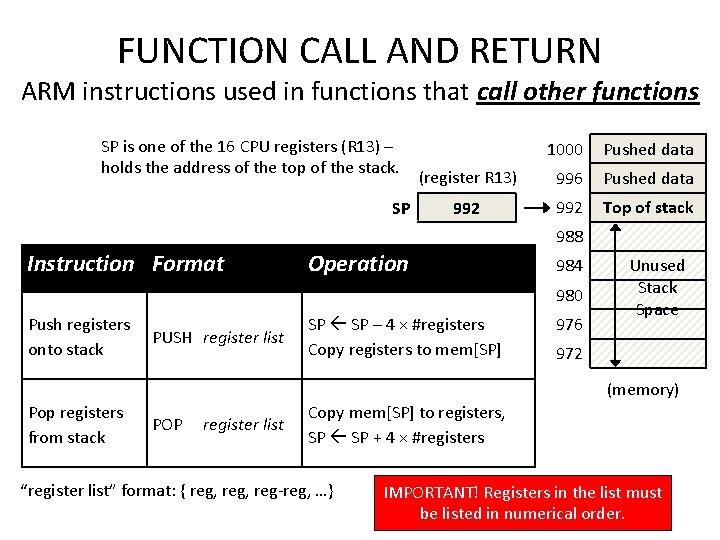

FUNCTION CALL AND RETURN ARM instructions used in functions that call other functions SP is one of the 16 CPU registers (R 13) – holds the address of the top of the stack. SP 1000 Pushed data (register R 13) 996 Pushed data 992 Top of stack 988 Instruction Format Operation 984 980 Push registers PUSH register list onto stack SP – 4 × #registers Copy registers to mem[SP] 976 Unused Stack Space 972 (memory) Pop registers from stack POP register list Copy mem[SP] to registers, SP + 4 × #registers “register list” format: { reg, reg-reg, …} IMPORTANT! Registers in the list must be listed in numerical order.

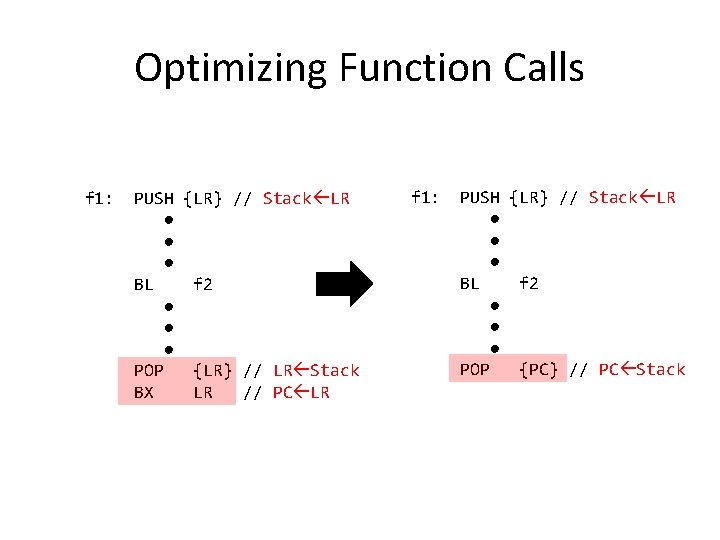

Optimizing Function Calls f 1: PUSH {LR} // Stack LR ● ● ● BL f 2 ● ● POP {LR} // LR Stack BX LR // PC LR f 1: PUSH {LR} // Stack LR ● ● ● BL f 2 ● ● POP {PC} // PC Stack

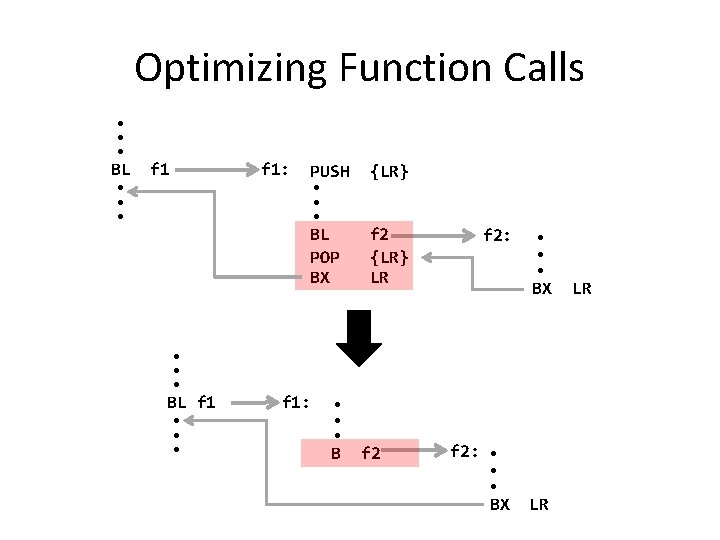

Optimizing Function Calls ● ● ● BL f 1: ● ● ● PUSH {LR} BL POP BX f 2 {LR} LR ● ● ● f 2: ● ● ● BX ● ● ● BL f 1 ● ● ● f 1: ● ● ● B f 2: ● ● ● BX LR LR

Chapter 3 Writing Functions in Assembly Part 3: Passing Parameters and Saving the Return Value

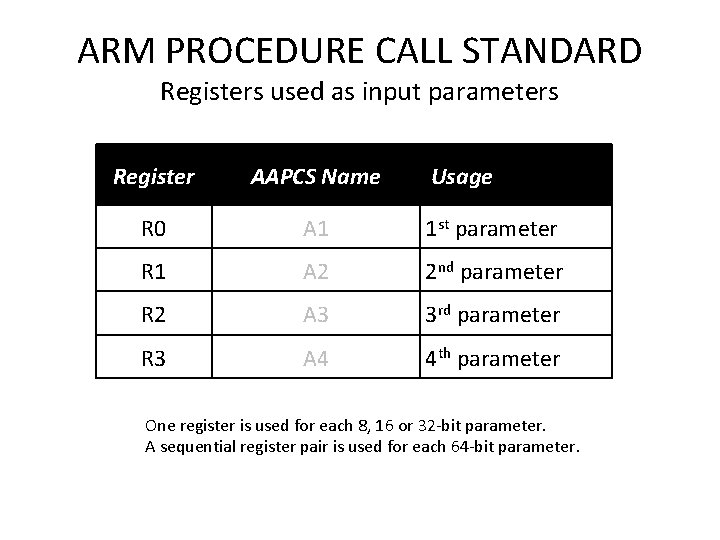

ARM PROCEDURE CALL STANDARD Registers used as input parameters Register AAPCS Name Usage R 0 A 1 1 st parameter R 1 A 2 2 nd parameter R 2 A 3 3 rd parameter R 3 A 4 4 th parameter One register is used for each 8, 16 or 32 -bit parameter. A sequential register pair is used for each 64 -bit parameter.

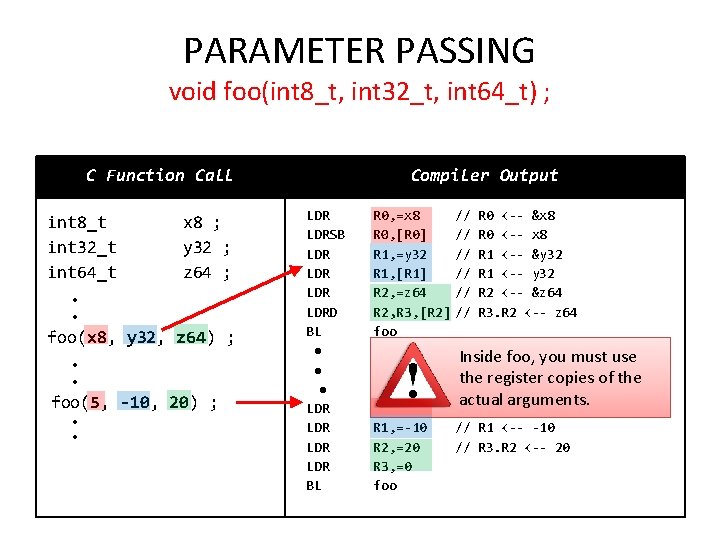

PARAMETER PASSING void foo(int 8_t, int 32_t, int 64_t) ; C Function Call int 8_t int 32_t int 64_t x 8 ; y 32 ; z 64 ; ● ● foo(x 8, y 32, z 64) ; ● ● foo(5, -10, 20) ; ● ● Compiler Output LDRSB LDR LDRD BL ● ● ● LDR LDR BL R 0, =x 8 R 0, [R 0] R 1, =y 32 R 1, [R 1] R 2, =z 64 R 2, R 3, [R 2] foo R 0, =5 R 1, =-10 R 2, =20 R 3, =0 foo // R 0 <-- &x 8 // R 0 <-- x 8 // R 1 <-- &y 32 // R 1 <-- y 32 // R 2 <-- &z 64 // R 3. R 2 <-- z 64 Inside foo, you must use the register copies of the actual arguments. // R 0 <-- 5 // R 1 <-- -10 // R 3. R 2 <-- 20

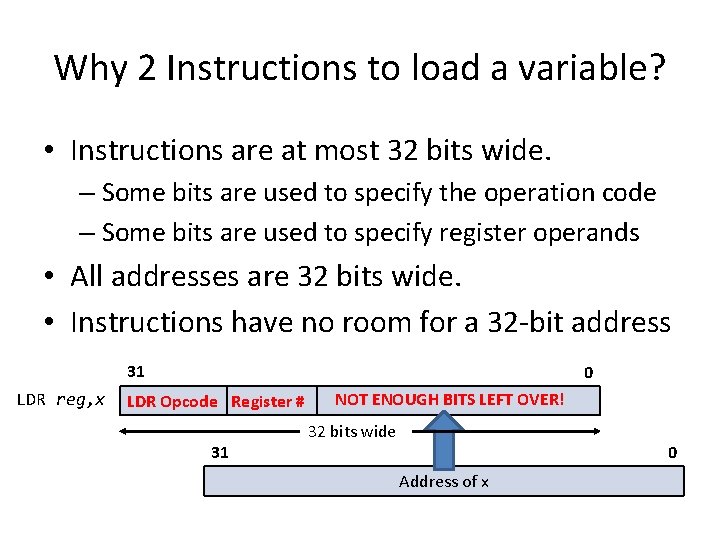

Why 2 Instructions to load a variable? • Instructions are at most 32 bits wide. – Some bits are used to specify the operation code – Some bits are used to specify register operands • All addresses are 32 bits wide. • Instructions have no room for a 32 -bit address 31 LDR reg, x 0 LDR Opcode Register # 31 NOT ENOUGH BITS LEFT OVER! 32 bits wide 0 Address of x

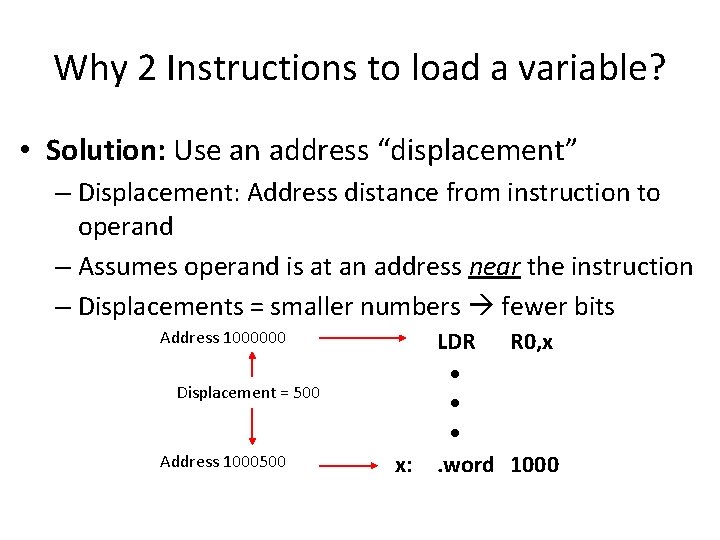

Why 2 Instructions to load a variable? • Solution: Use an address “displacement” – Displacement: Address distance from instruction to operand – Assumes operand is at an address near the instruction – Displacements = smaller numbers fewer bits Address 1000000 Displacement = 500 LDR R 0, x ● ● ● Address 1000500 x: . word 1000

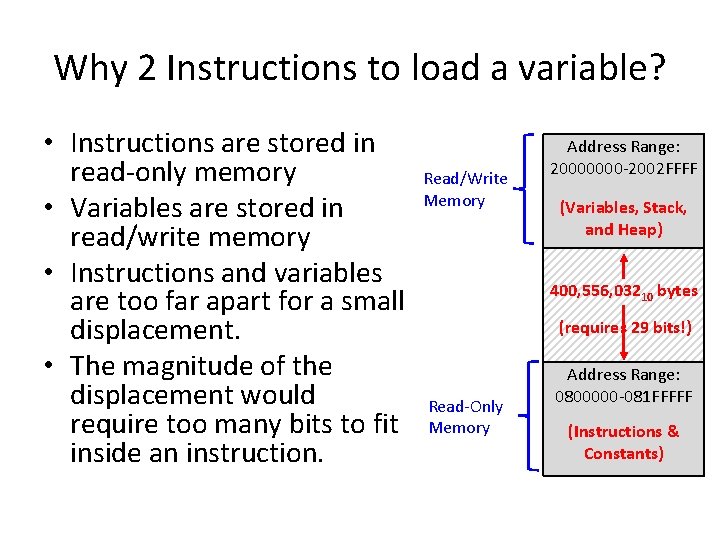

Why 2 Instructions to load a variable? • Instructions are stored in read-only memory • Variables are stored in read/write memory • Instructions and variables are too far apart for a small displacement. • The magnitude of the displacement would require too many bits to fit inside an instruction. Read/Write Memory Address Range: 20000000 -2002 FFFF (Variables, Stack, and Heap) 400, 556, 03210 bytes (requires 29 bits!) Read-Only Memory Address Range: 0800000 -081 FFFFF (Instructions & Constants)

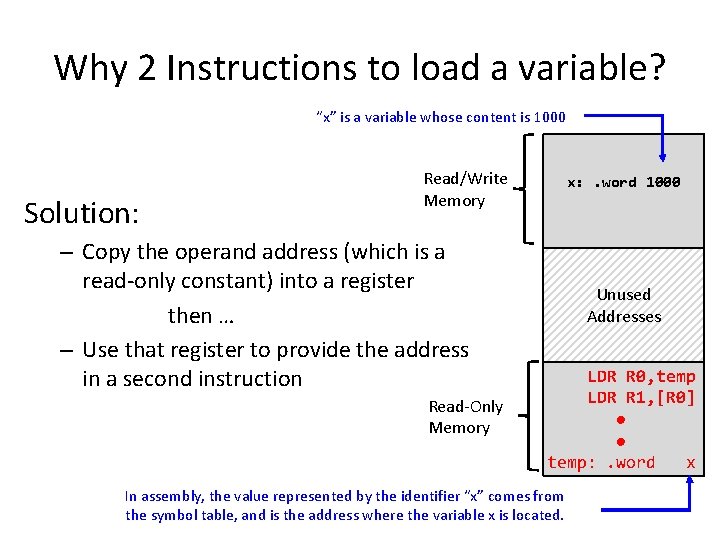

Why 2 Instructions to load a variable? “x” is a variable whose content is 1000 Solution: Read/Write Memory – Copy the operand address (which is a read-only constant) into a register then … – Use that register to provide the address in a second instruction Read-Only Memory x: . word 1000 Unused Addresses LDR R 0, temp LDR R 1, [R 0] ● ● temp: . word x In assembly, the value represented by the identifier “x” comes from the symbol table, and is the address where the variable x is located.

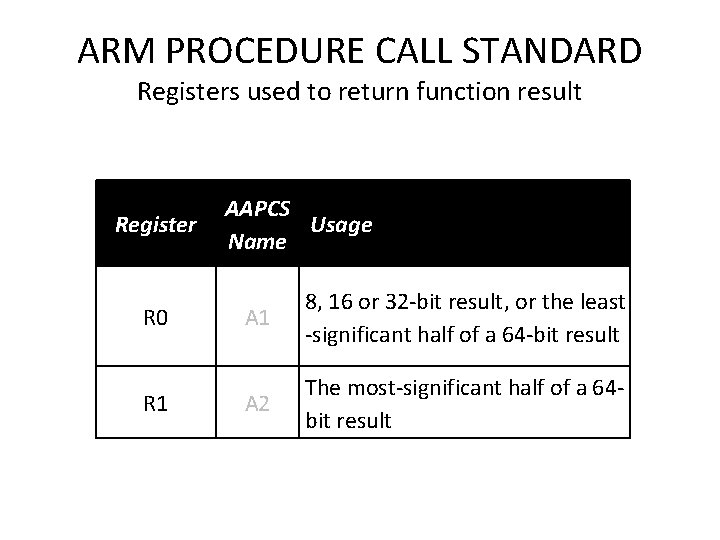

ARM PROCEDURE CALL STANDARD Registers used to return function result Register R 0 R 1 AAPCS Usage Name A 1 8, 16 or 32 -bit result, or the least -significant half of a 64 -bit result A 2 The most-significant half of a 64 bit result

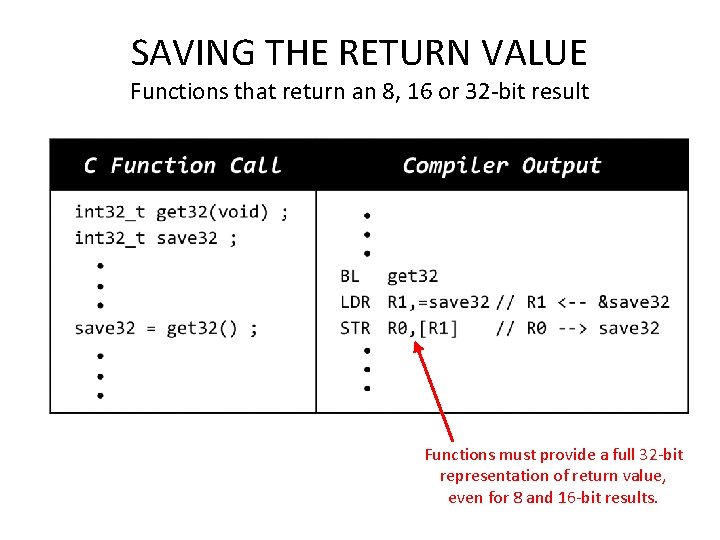

SAVING THE RETURN VALUE Functions that return an 8, 16 or 32 -bit result Functions must provide a full 32 -bit representation of return value, even for 8 and 16 -bit results.

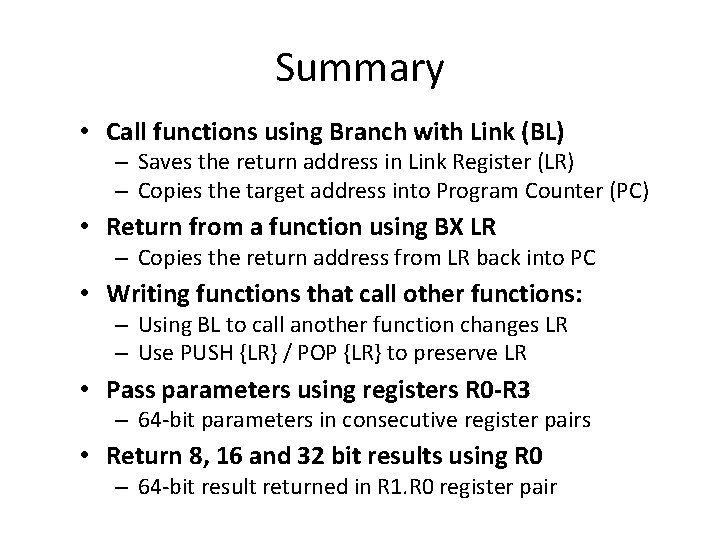

Summary • Call functions using Branch with Link (BL) – Saves the return address in Link Register (LR) – Copies the target address into Program Counter (PC) • Return from a function using BX LR – Copies the return address from LR back into PC • Writing functions that call other functions: – Using BL to call another function changes LR – Use PUSH {LR} / POP {LR} to preserve LR • Pass parameters using registers R 0 -R 3 – 64 -bit parameters in consecutive register pairs • Return 8, 16 and 32 bit results using R 0 – 64 -bit result returned in R 1. R 0 register pair

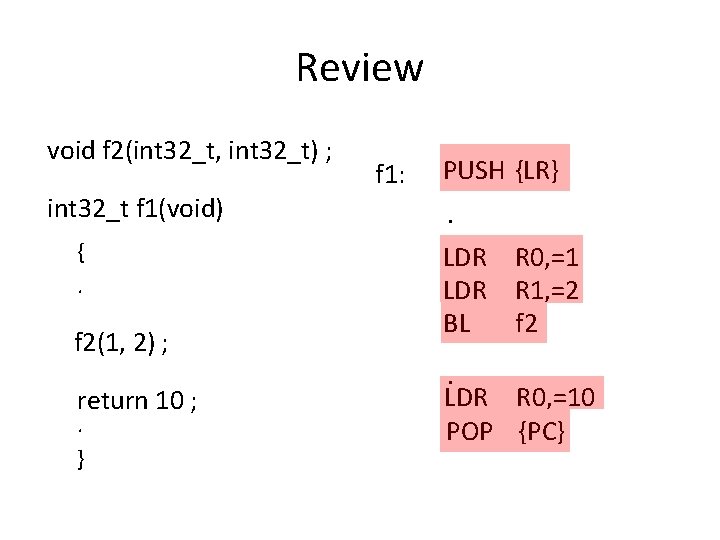

Review f 2(int 32_t, int 32_t) ; void f 2(void) ; int 32_t f 1(void) void f 1(void) {. . f 2() ; f 2(1, 2) ; . . return 10 ; . } f 1: PUSH {LR}. . . LDR R 0, =1 LDR R 1, =2. BL f 2. . LDR R 0, =10. POP {PC} BX LR

Chapter 3 Writing Functions in Assembly Part 4: Preparing and Using the Return Value

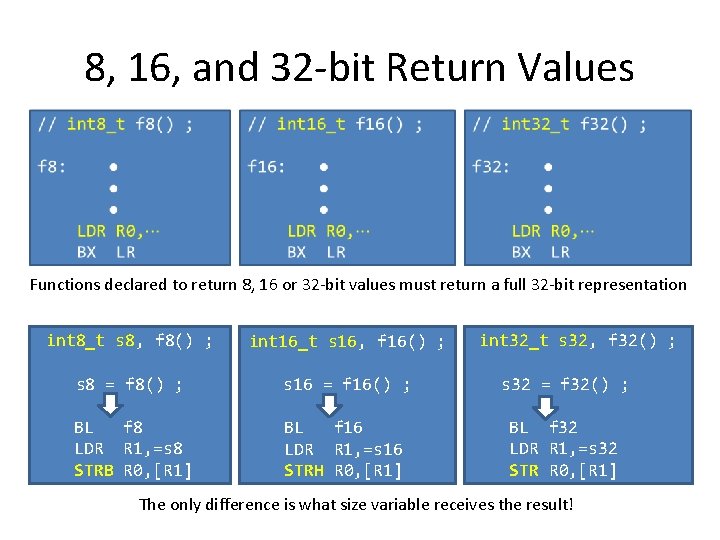

8, 16, and 32 -bit Return Values Functions declared to return 8, 16 or 32 -bit values must return a full 32 -bit representation int 8_t s 8, f 8() ; int 16_t s 16, f 16() ; s 8 = f 8() ; s 16 = f 16() ; BL f 8 LDR R 1, =s 8 STRB R 0, [R 1] BL f 16 LDR R 1, =s 16 STRH R 0, [R 1] int 32_t s 32, f 32() ; s 32 = f 32() ; BL f 32 LDR R 1, =s 32 STR R 0, [R 1] The only difference is what size variable receives the result!

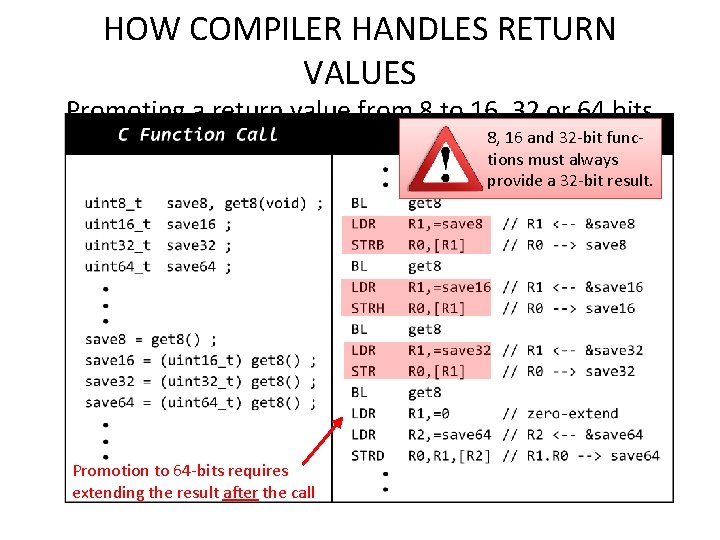

HOW COMPILER HANDLES RETURN VALUES Promoting a return value from 8 to 16, 32 or 64 bits 8, 16 and 32 -bit functions must always provide a 32 -bit result. Promotion to 64 -bits requires extending the result after the call

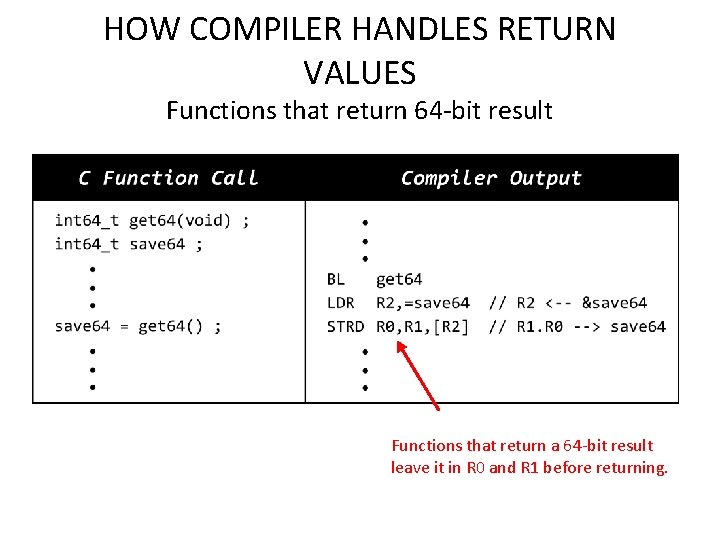

HOW COMPILER HANDLES RETURN VALUES Functions that return 64 -bit result Functions that return a 64 -bit result leave it in R 0 and R 1 before returning.

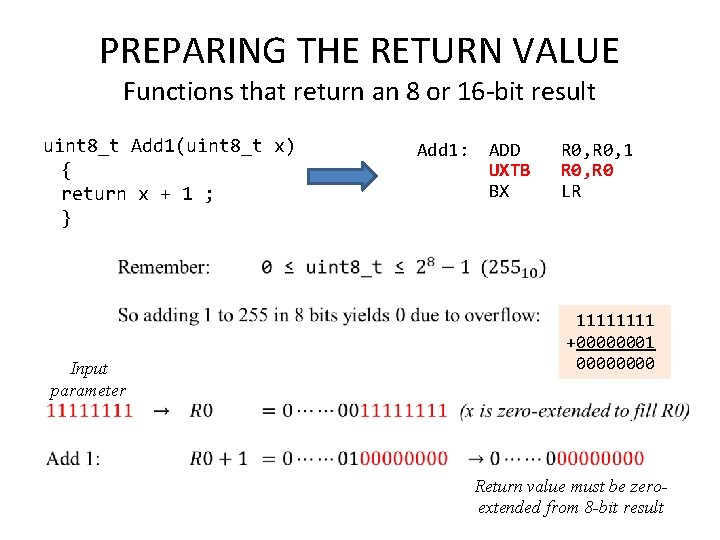

PREPARING THE RETURN VALUE Functions that return an 8 or 16 -bit result uint 8_t Add 1(uint 8_t x) { return x + 1 ; } Add 1: ADD UXTB BX R 0, 1 R 0, R 0 LR Input parameter 1111 +00000001 0000 Return value must be zeroextended from 8 -bit result

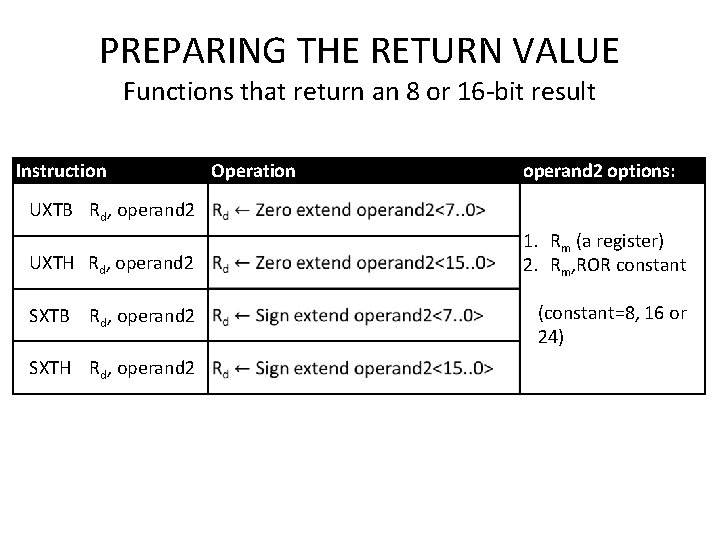

PREPARING THE RETURN VALUE Functions that return an 8 or 16 -bit result Instruction Operation operand 2 options: UXTB Rd, operand 2 UXTH Rd, operand 2 1. Rm (a register) 2. Rm, ROR constant SXTB Rd, operand 2 (constant=8, 16 or 24) SXTH Rd, operand 2

Chapter 3 Writing Functions in Assembly Part 5: Coding Conventions

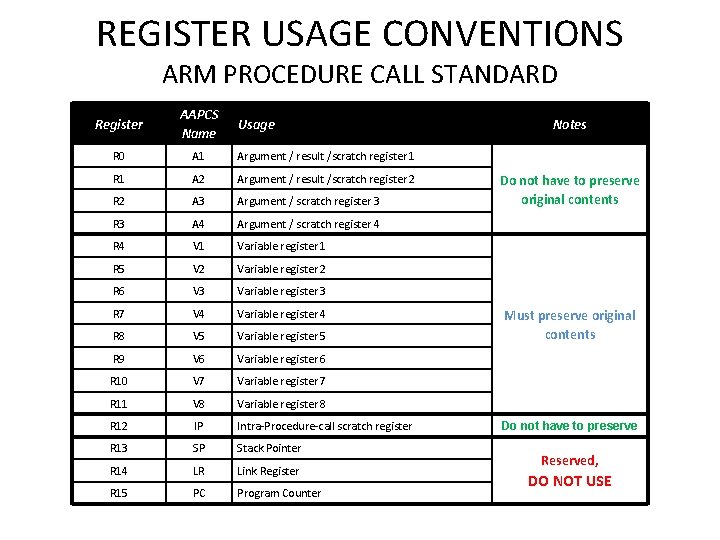

REGISTER USAGE CONVENTIONS ARM PROCEDURE CALL STANDARD Register AAPCS Name R 0 A 1 Argument / result /scratch register 1 R 1 A 2 Argument / result /scratch register 2 R 2 A 3 Argument / scratch register 3 R 3 A 4 Argument / scratch register 4 R 4 V 1 Variable register 1 R 5 V 2 Variable register 2 R 6 V 3 Variable register 3 R 7 V 4 Variable register 4 R 8 V 5 Variable register 5 R 9 V 6 Variable register 6 R 10 V 7 Variable register 7 R 11 V 8 Variable register 8 R 12 IP Intra-Procedure-call scratch register R 13 SP Stack Pointer R 14 LR Link Register R 15 PC Program Counter Usage Notes Do not have to preserve original contents Must preserve original contents Do not have to preserve Reserved, DO NOT USE

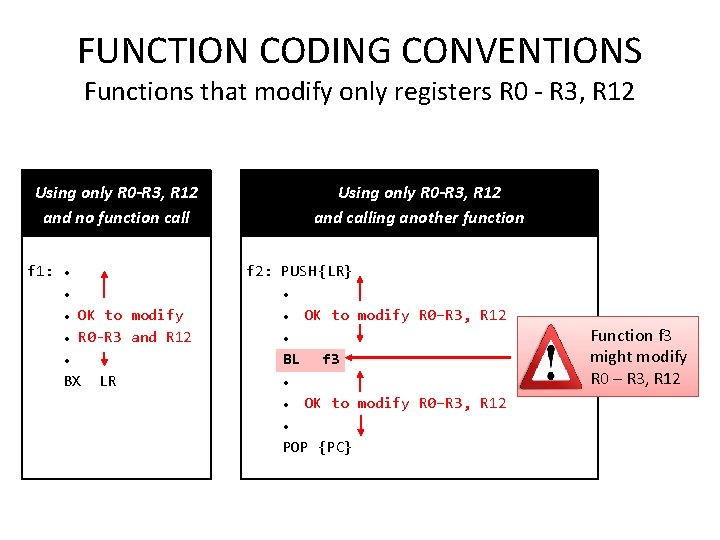

FUNCTION CODING CONVENTIONS Functions that modify only registers R 0 - R 3, R 12 Using only R 0 -R 3, R 12 and no function call f 1: ● Using only R 0 -R 3, R 12 and calling another function f 2: PUSH {LR} ● ● ● OK to modify ● ● R 0 -R 3 and R 12 ● ● BL BX LR OK to modify R 0–R 3, R 12 f 3 ● ● OK to modify R 0–R 3, R 12 ● POP {PC} Function f 3 might modify R 0 – R 3, R 12

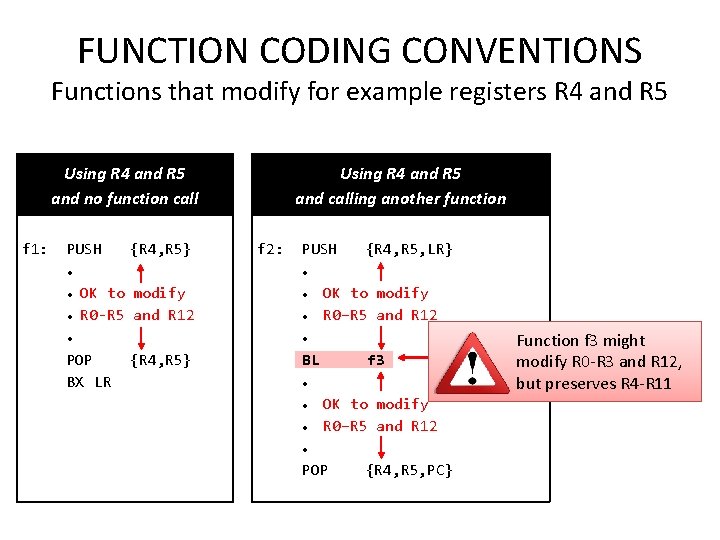

FUNCTION CODING CONVENTIONS Functions that modify for example registers R 4 and R 5 Using R 4 and R 5 and no function call f 1: PUSH {R 4, R 5} Using R 4 and R 5 and calling another function f 2: PUSH ● ● ● {R 4, R 5, LR} ● OK to modify R 0 -R 5 and R 12 ● ● ● POP BX LR OK to modify R 0–R 5 and R 12 ● {R 4, R 5} BL f 3 ● ● ● OK to modify R 0–R 5 and R 12 ● POP {R 4, R 5, PC} Function f 3 might modify R 0 -R 3 and R 12, but preserves R 4 -R 11

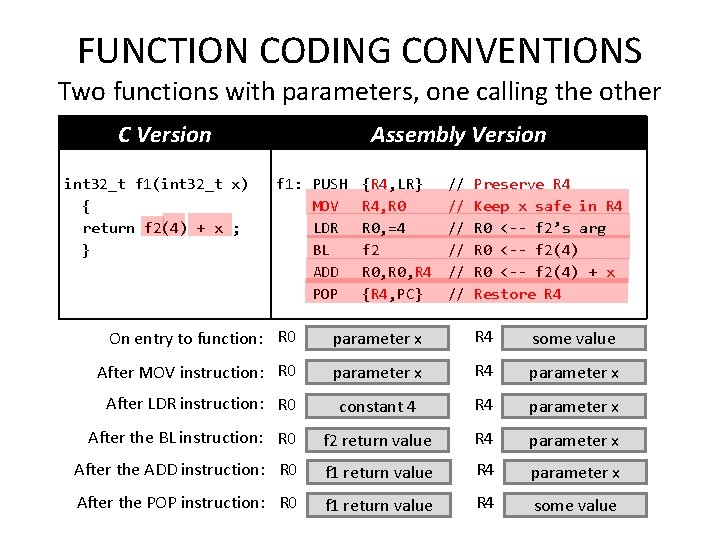

FUNCTION CODING CONVENTIONS Two functions with parameters, one calling the other C Version int 32_t f 1(int 32_t x) { return f 2(4) + x ; } Assembly Version f 1: PUSH MOV LDR BL ADD POP {R 4, LR} R 4, R 0, =4 f 2 R 0, R 4 {R 4, PC} // Preserve R 4 // Keep x safe in R 4 // R 0 <-- f 2’s arg // R 0 <-- f 2(4) + x // Restore R 4 On entry to function: R 0 parameter x R 4 some value After MOV instruction: R 0 parameter x R 4 parameter x After LDR instruction: R 0 constant 4 R 4 parameter x After the BL instruction: R 0 f 2 return value R 4 parameter x After the ADD instruction: R 0 f 1 return value R 4 parameter x After the POP instruction: R 0 f 1 return value R 4 some value

- Slides: 39