Chapter 3 Digital Transmission Fundamentals Digital Representation of

- Slides: 143

Chapter 3 Digital Transmission Fundamentals Digital Representation of Information Characterization of Communication Channels Fundamental Limits in Digital Transmission Line Coding and Digital Modulation Properties of Transmission Media Error Detection and Correction

Present the fundamental concepts concerning digital transmission Give the basis for the design of digital transmission systems (physical layer)

Questions of Interest How long will it take to transmit a message? Can a network/system handle a voice or video call? How many bits/sec does voice/video require? At what quality? Can we transmit a message without errors? How many bits are in the message (text, image)? How fast does the network/system transfer information? How are errors introduced? How are errors detected and/or corrected? What transmission speed is possible over radio, copper cables, fiber, infrared, …?

Digital representation of Info Applications over net: involve the transfer of info of various types Two basic types Block-oriented info: Documents, Email, images Stream-oriented info: telephony, TV

Block-oriented info: Info that appears in single block Documents, Email, images We are interested in no. of bits to represent block How can we reduce no. of bits? § § Files contain some form of redundancy Use Data compression techniques Compression ratio = no of bits before/no of bits after By how much does this affect the transmission spead? What is the total delay incurred in transmitting a file with L bits? How can we reduce this delay?

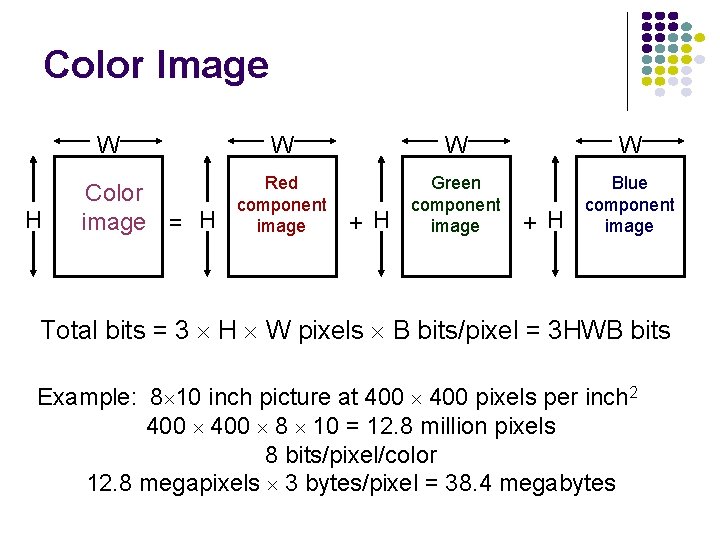

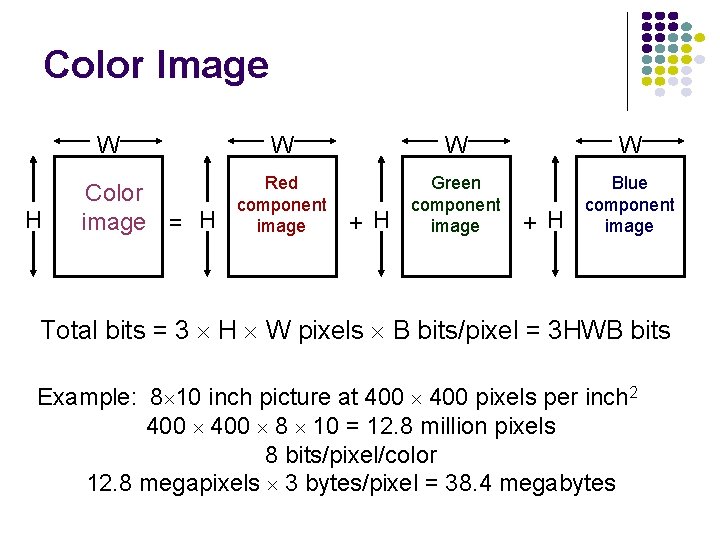

Color Image W H Color image = H W W W Red component image Green component image Blue component image + H Total bits = 3 H W pixels B bits/pixel = 3 HWB bits Example: 8 10 inch picture at 400 pixels per inch 2 400 8 10 = 12. 8 million pixels 8 bits/pixel/color 12. 8 megapixels 3 bytes/pixel = 38. 4 megabytes

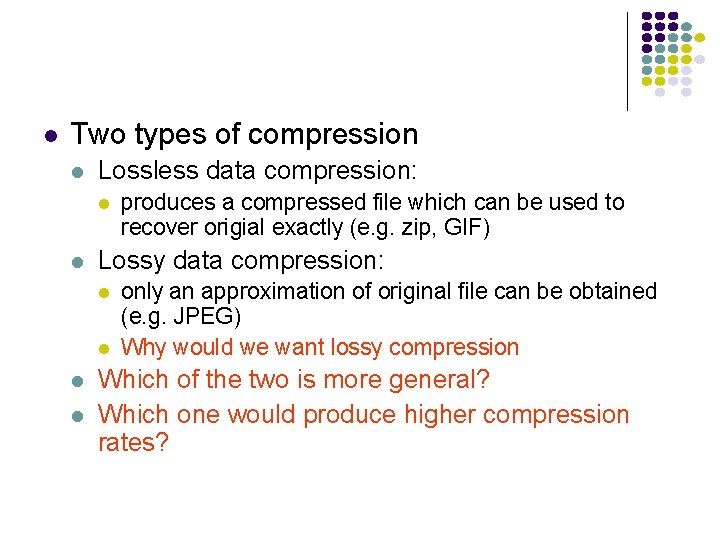

Two types of compression Lossless data compression: Lossy data compression: produces a compressed file which can be used to recover origial exactly (e. g. zip, GIF) only an approximation of original file can be obtained (e. g. JPEG) Why would we want lossy compression Which of the two is more general? Which one would produce higher compression rates?

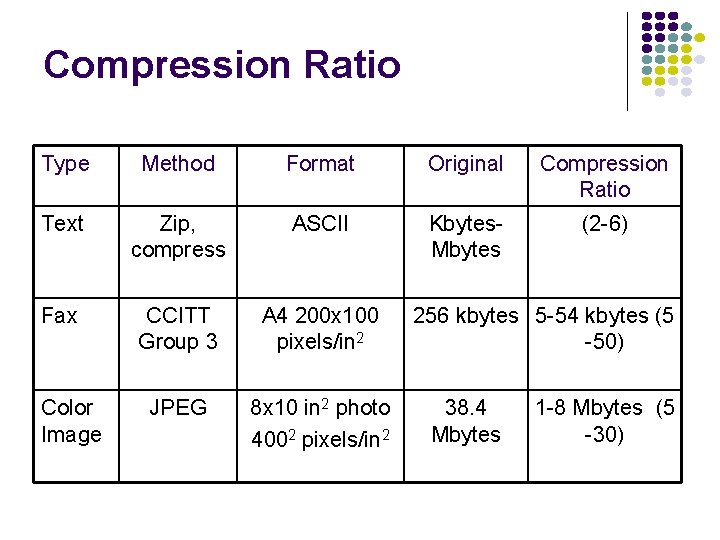

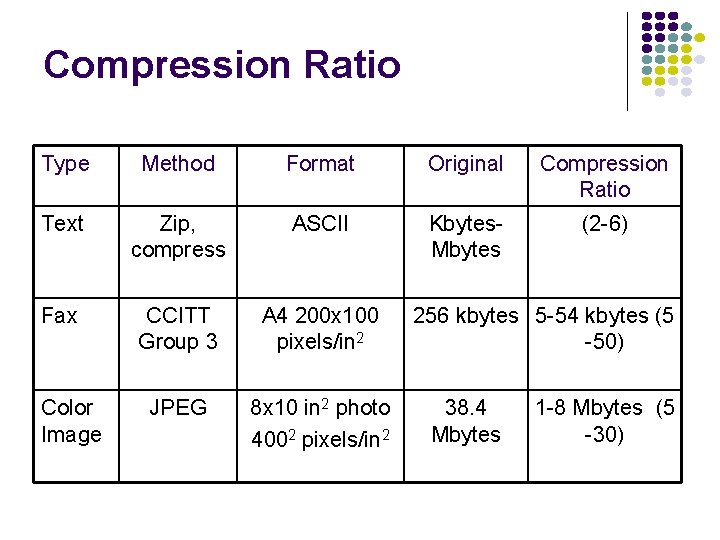

Compression Ratio Type Method Format Original Compression Ratio Text Zip, compress ASCII Kbytes. Mbytes (2 -6) Fax CCITT Group 3 A 4 200 x 100 pixels/in 2 JPEG 8 x 10 in 2 photo 4002 pixels/in 2 Color Image 256 kbytes 5 -54 kbytes (5 -50) 38. 4 Mbytes 1 -8 Mbytes (5 -30)

Stream-oriented info: Info that is produced continuously; needs to be transmitted as it is produced Music, voice, video We are interested in bit rate required to represent info To do so, we need to analog to digital conversion § § Sampling (at rate more than 2 X signal BW) Quantization When do we consider a voice signal to be a block oriented info and when do we consider it to be stream –oriented info?

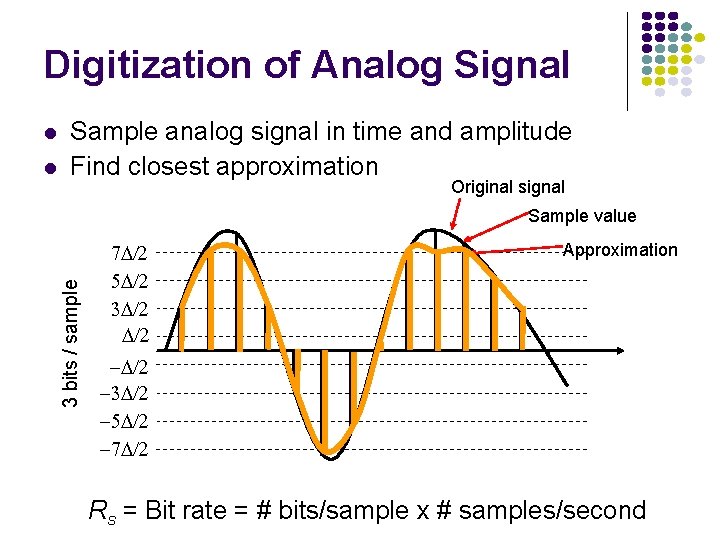

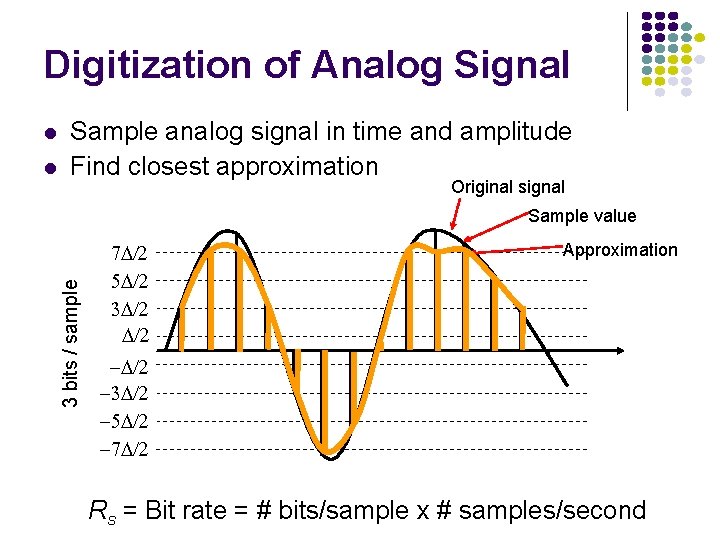

Digitization of Analog Signal Sample analog signal in time and amplitude Find closest approximation Original signal Sample value 3 bits / sample 7 D/2 5 D/2 3 D/2 Approximation -D/2 -3 D/2 -5 D/2 -7 D/2 Rs = Bit rate = # bits/sample x # samples/second

Bit Rate of Digitized Signal Bandwidth Ws Hertz: how fast the signal changes Higher bandwidth → more frequent samples Minimum sampling rate = 2 x Ws Representation accuracy: approximation error Higher accuracy → smaller spacing between approximation values → more bits per sample At what rate are the bits produced? At what rate should the communication channel transmit information?

Example: Voice & Audio Telephone voice (PCM) Ws = 4 k. Hz → 8000 samples/sec 8 bits/sample Rs=8 x 8000 = 64 kbps Cellular phones use more powerful compression algorithms: 8 -12 kbps (e. g. DPCM, ADPCM, and Linear prediction coding) Are these compression techniques lossy or lossless? CD Audio Ws = 22 k. Hertz → 44000 samples/sec 16 bits/sample Rs=16 x 44000= 704 kbps per audio channel MP 3 uses more powerful compression algorithms: 50 kbps per audio channel

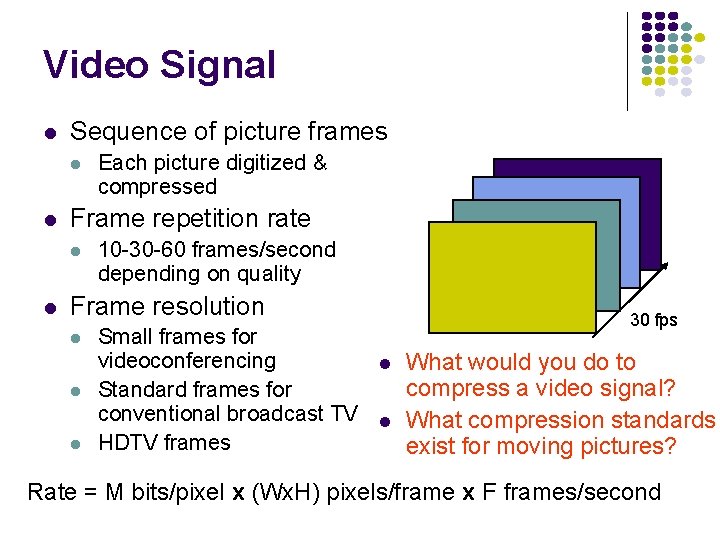

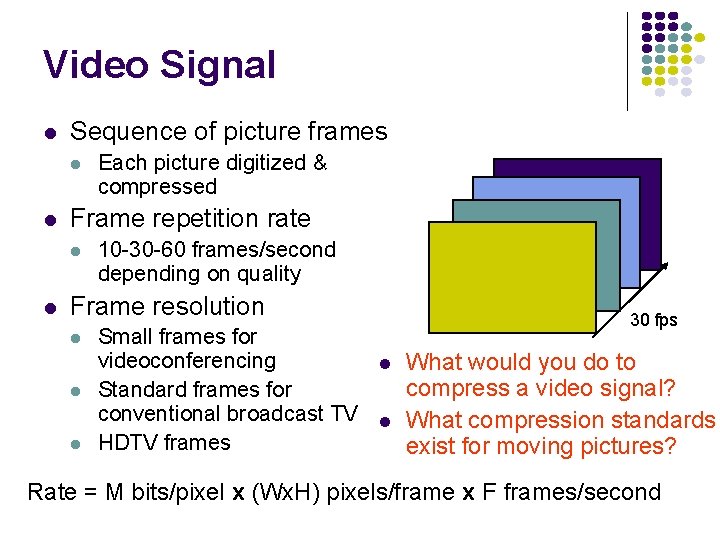

Video Signal Sequence of picture frames Frame repetition rate Each picture digitized & compressed 10 -30 -60 frames/second depending on quality Frame resolution Small frames for videoconferencing Standard frames for conventional broadcast TV HDTV frames 30 fps What would you do to compress a video signal? What compression standards exist for moving pictures? Rate = M bits/pixel x (Wx. H) pixels/frame x F frames/second

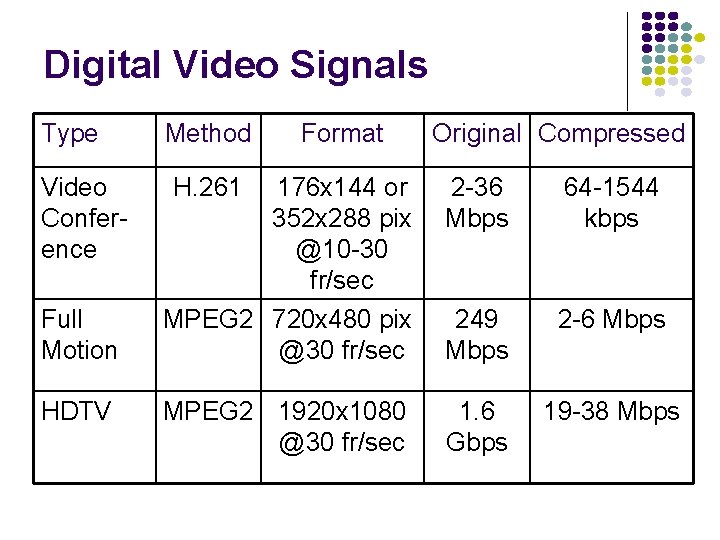

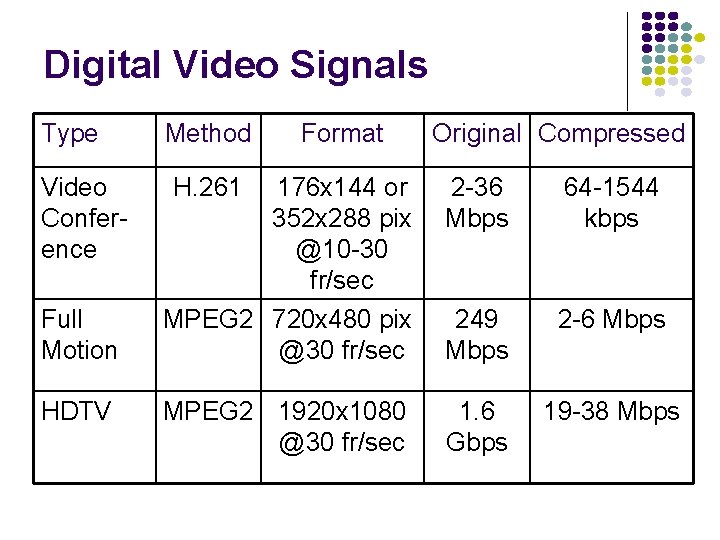

Digital Video Signals Type Video Conference Full Motion HDTV Method Format H. 261 Original Compressed 176 x 144 or 352 x 288 pix @10 -30 fr/sec MPEG 2 720 x 480 pix @30 fr/sec 2 -36 Mbps 64 -1544 kbps 249 Mbps 2 -6 Mbps MPEG 2 1920 x 1080 @30 fr/sec 1. 6 Gbps 19 -38 Mbps

The cost of compression vs. transmission Same info can be represented with wide range of bit rates (depending on quality you ask for) There is a cost of signal processing required to compress (increases as compression rate increases) There is a cost associated with bit rate to tx There should be a trade-off Give an example where: cost of transmission is low cost of transmission is expensive

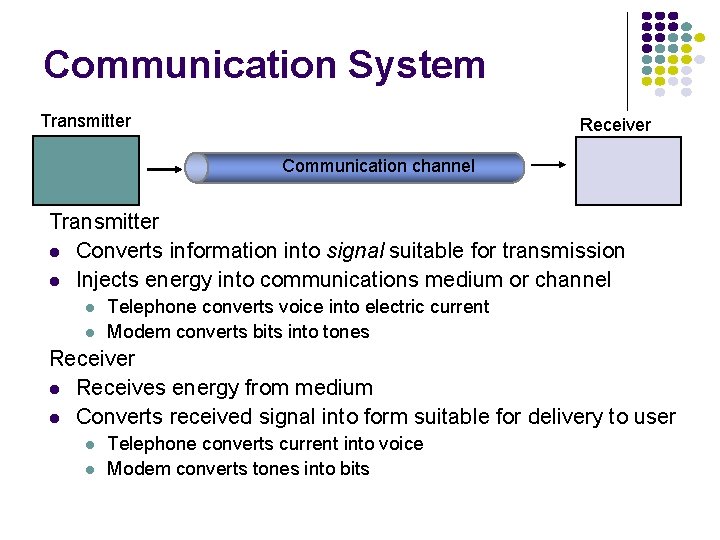

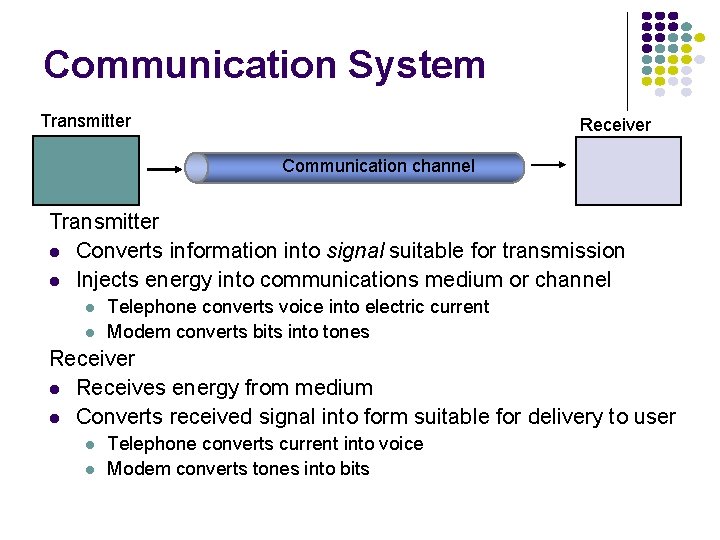

Communication System Transmitter Receiver Communication channel Transmitter Converts information into signal suitable for transmission Injects energy into communications medium or channel Telephone converts voice into electric current Modem converts bits into tones Receiver Receives energy from medium Converts received signal into form suitable for delivery to user Telephone converts current into voice Modem converts tones into bits

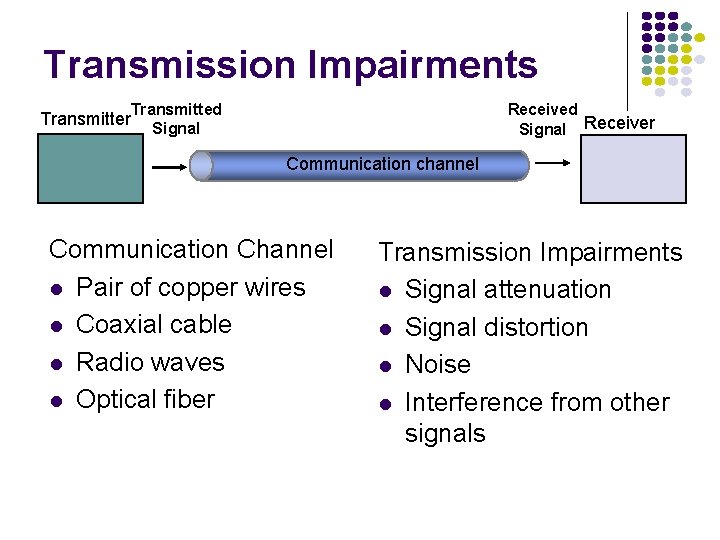

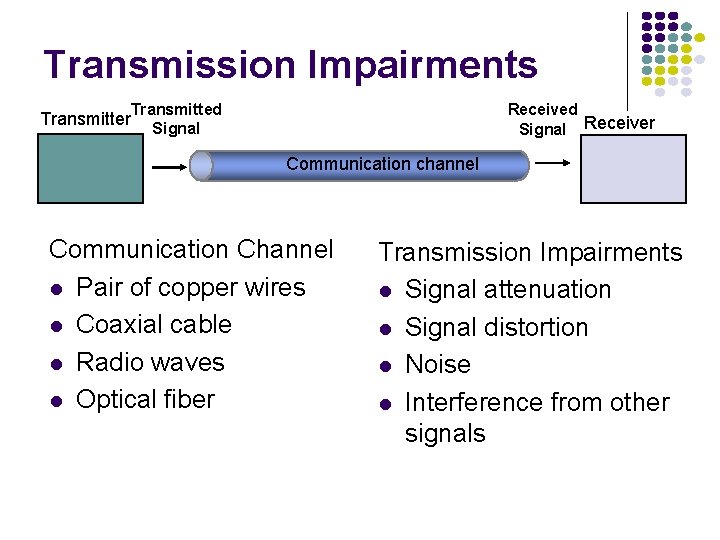

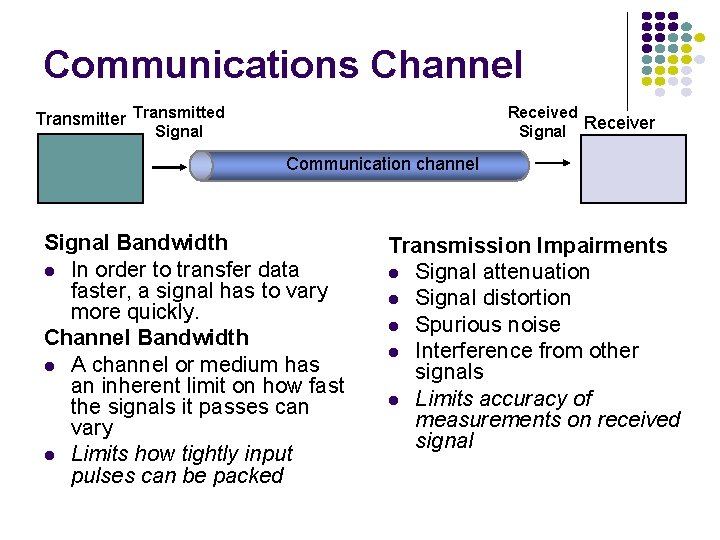

Transmission Impairments Transmitter Transmitted Signal Receiver Communication channel Communication Channel Pair of copper wires Coaxial cable Radio waves Optical fiber Transmission Impairments Signal attenuation Signal distortion Noise Interference from other signals

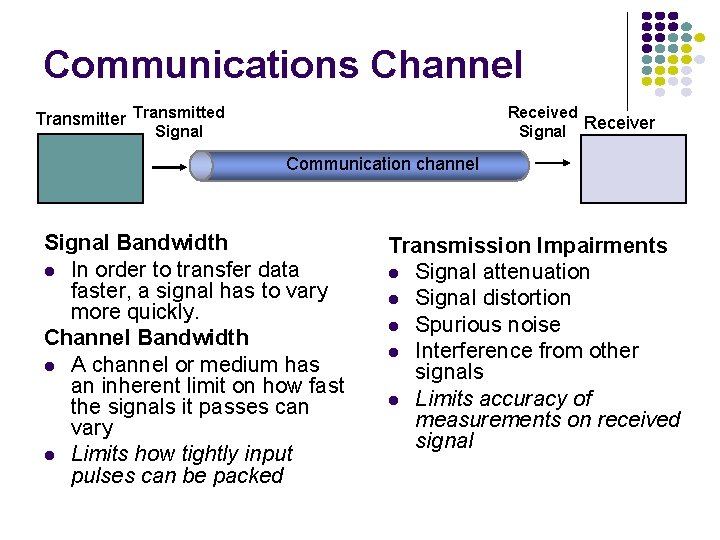

Communications Channel Transmitter Transmitted Receiver Signal Communication channel Signal Bandwidth In order to transfer data faster, a signal has to vary more quickly. Channel Bandwidth A channel or medium has an inherent limit on how fast the signals it passes can vary Limits how tightly input pulses can be packed Transmission Impairments Signal attenuation Signal distortion Spurious noise Interference from other signals Limits accuracy of measurements on received signal

Comparsion of Analog and Digital Transmission Cost advantage of digital over analog Tx More cost savings with long distance: With distance, transmitted signal Attenuated and distorted Subject to more Interference: radio signals, car ignitions, noise inherent in electronic equip How to transmit over long distances? Repeaters

Repeaters in Analog Comm. Task: generate a signal as close to original signal as possible Where do you insert repeater: As signal is transmitted, signal is attinuated and distorted Random noise is added Repeater should be inserted before noise level becomes comparable to signal level

Repeaters in Analog Comm. (2) How to deal with attentuation Amplify signal How to deal with distortion: Employ an equalizer Two sources of distortion 1. Different freq. components attenuated differently Equalizer amplifies different components differently Different freq. components delayed differently Equalizer differential delays to realign components

Repeaters in Analog Comm. (3) How to deal with noise Limited ability to deal with noise (why? ) If noise out of band, filter it out If inside band, nothing can be done with it Signal recovered by repeater will contain some noise Effect of multiple repeaters is similar to what happens with repeated recordings of an audio cassette Making a photocopy of a photocopy

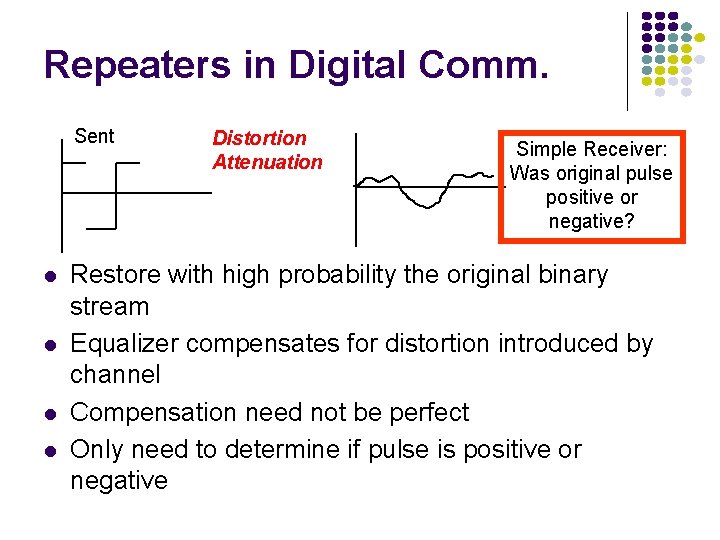

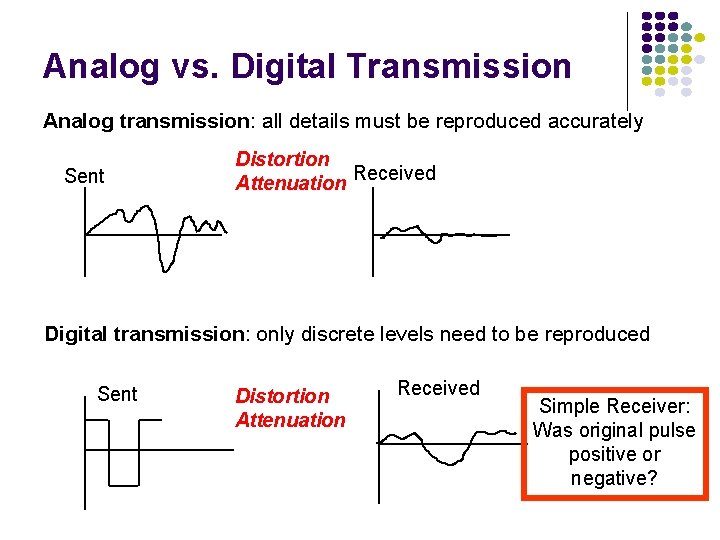

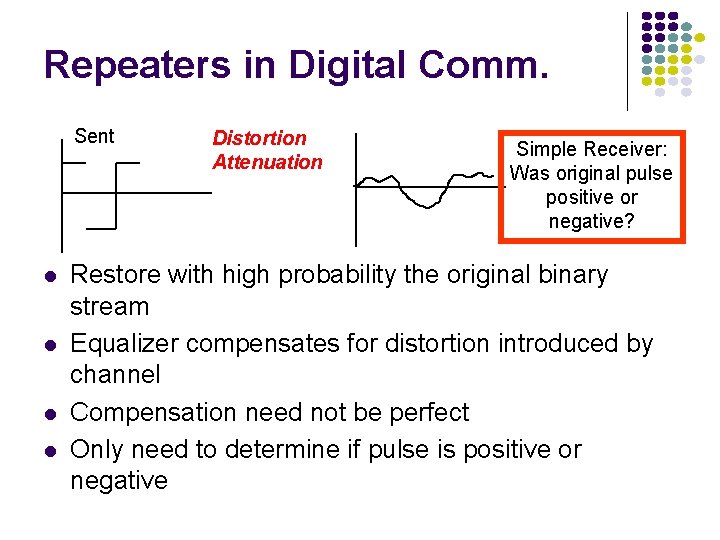

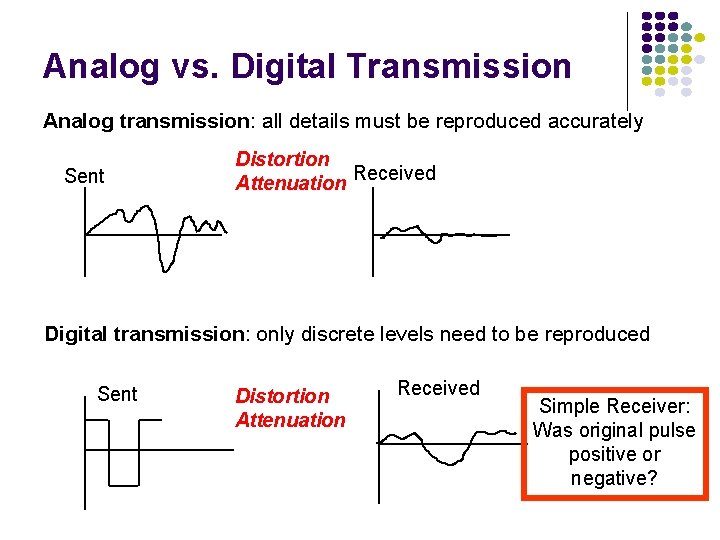

Repeaters in Digital Comm. Sent Distortion Attenuation Simple Receiver: Was original pulse positive or negative? Restore with high probability the original binary stream Equalizer compensates for distortion introduced by channel Compensation need not be perfect Only need to determine if pulse is positive or negative

Repeaters in Digital Comm. (2) In absence of noise, signal can be recovered perfectly With noise, error is unavoidable Error occurs if noise level is large enough to change polarity of signal

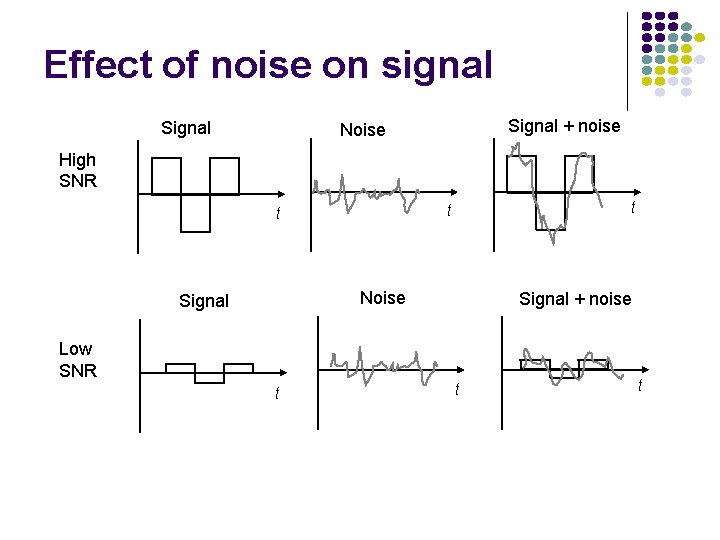

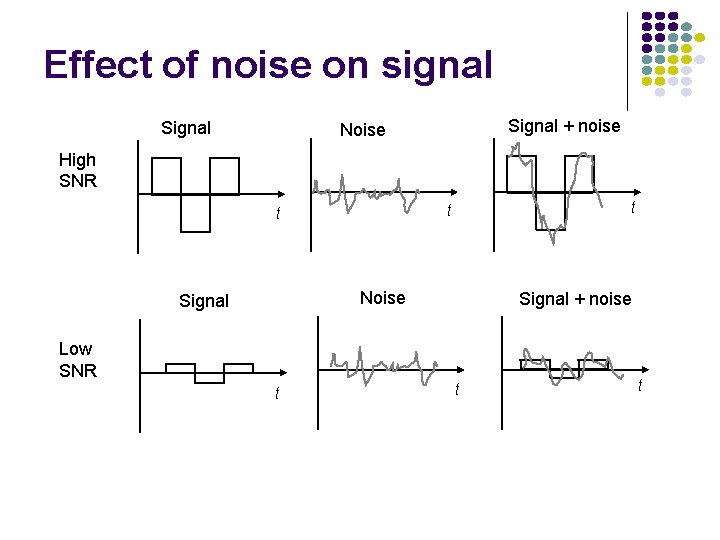

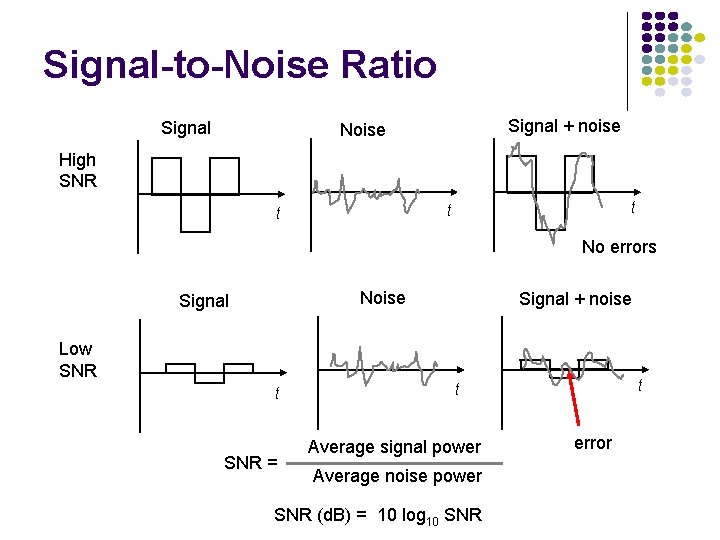

Effect of noise on signal Signal + noise Noise High SNR t t t Noise Signal + noise Low SNR t t t

Repeaters in Digital Comm. (3) Probability of bit errors is very low: Bit error rates of order 10^-7 (1 error every 10 million bits!!) or even lower This explains why multiple copying of file of music does not degrade quality (headache for recording companies)

Analog vs. Digital Transmission Analog transmission: all details must be reproduced accurately Sent Distortion Attenuation Received Digital transmission: only discrete levels need to be reproduced Sent Distortion Attenuation Received Simple Receiver: Was original pulse positive or negative?

Advantages of Digital Transmission over Analog Transmission From previous slides, what are the advantages of Digital Transmission over Analog transmission Discuss that on Web. CT See section 3. 2. 1

Why Digital Communications? Why Digital Communication? 1) Immunity to Noise: Can be reproduced by repeaters 2) Integration of services: voice, data, image, video can be transmitted over the same media 3) Advanced/sophisticated processing Error detection/correction Encryption Compression

4) Digital technology 5) Data integrity High bandwidth links economical High degree of multiplexing easier with digital techniques 7) Security & Privacy Longer distances over lower quality lines 6) Capacity utilization Low cost LSI/VLSI technology Encryption 8) Integration Can treat analog and digital data similarly

Basic Properties of a Digital Transmission System How do we compare various digital transmission systems? Digital transmission system transfers a sequence of bits from one end to another How fast does this transfer takes place (Bit rate) We want high bit rate We also want reliability There are fundamental limits on digital transmission when it comes to speed and reliability

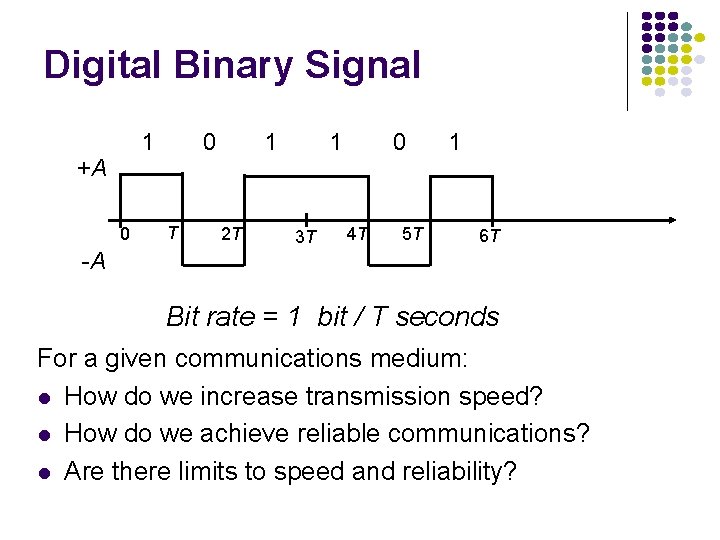

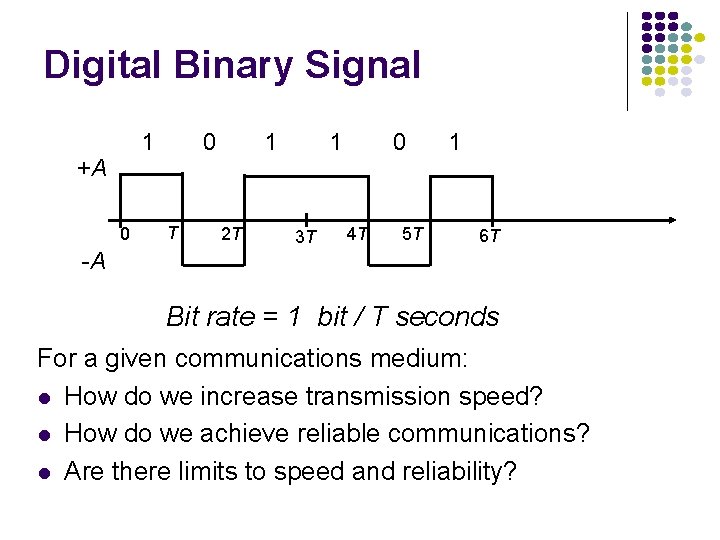

Digital Binary Signal 1 +A 0 -A 0 T 1 2 T 1 3 T 0 4 T 5 T 1 6 T Bit rate = 1 bit / T seconds For a given communications medium: How do we increase transmission speed? How do we achieve reliable communications? Are there limits to speed and reliability?

Speed and Reliability Speed and reliability are affected by Energy put into transmitting each signal Distance that signal has to traverese The amount of noise at receiver Bandwidth of communication channel

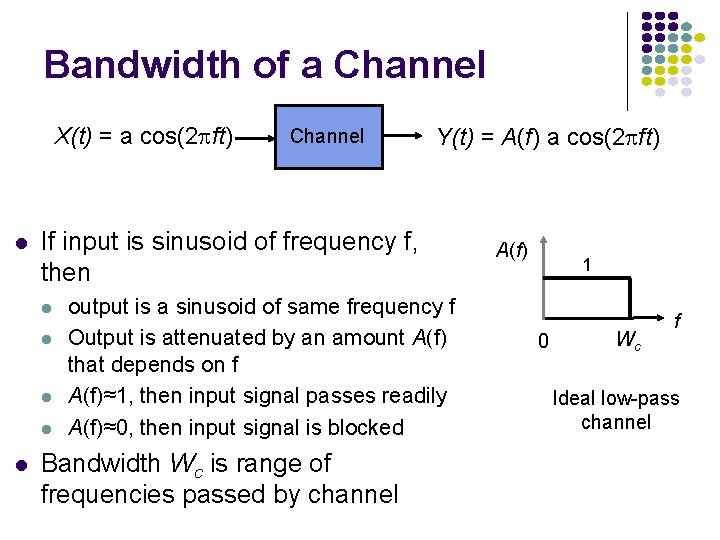

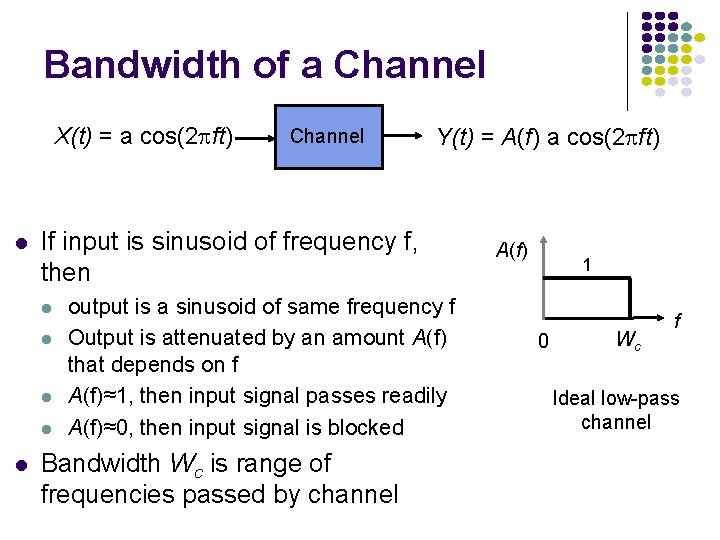

Bandwidth of a Channel X(t) = a cos(2 ft) Y(t) = A(f) a cos(2 ft) If input is sinusoid of frequency f, then Channel output is a sinusoid of same frequency f Output is attenuated by an amount A(f) that depends on f A(f)≈1, then input signal passes readily A(f)≈0, then input signal is blocked Bandwidth Wc is range of frequencies passed by channel A(f) 1 0 Wc f Ideal low-pass channel

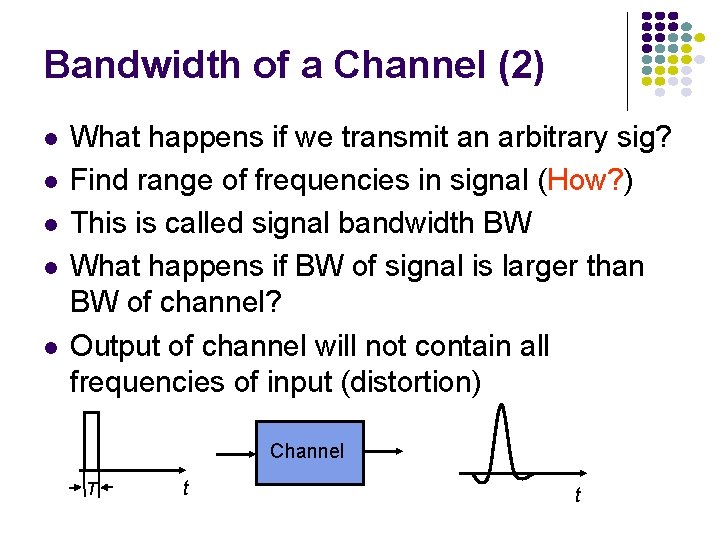

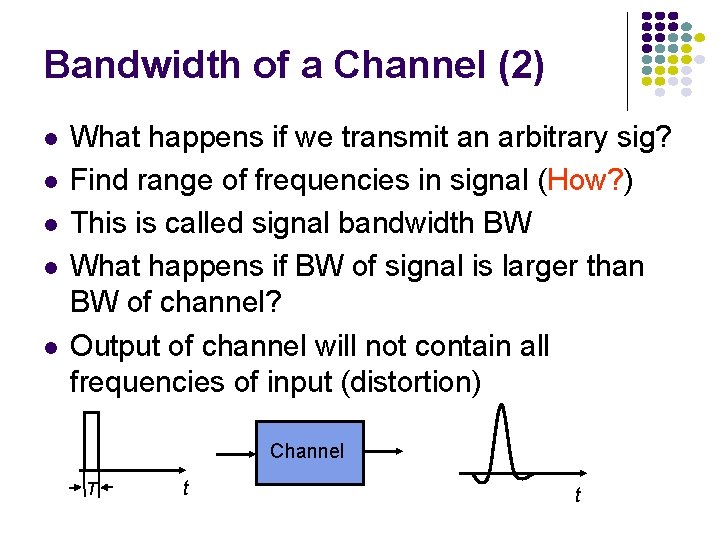

Bandwidth of a Channel (2) What happens if we transmit an arbitrary sig? Find range of frequencies in signal (How? ) This is called signal bandwidth BW What happens if BW of signal is larger than BW of channel? Output of channel will not contain all frequencies of input (distortion) Channel T t t

What happens as we increase signaling speed? Pulses narrow (vary more rapidly); so signal has higher BW BW of output limited by BW of channel giving more distortion

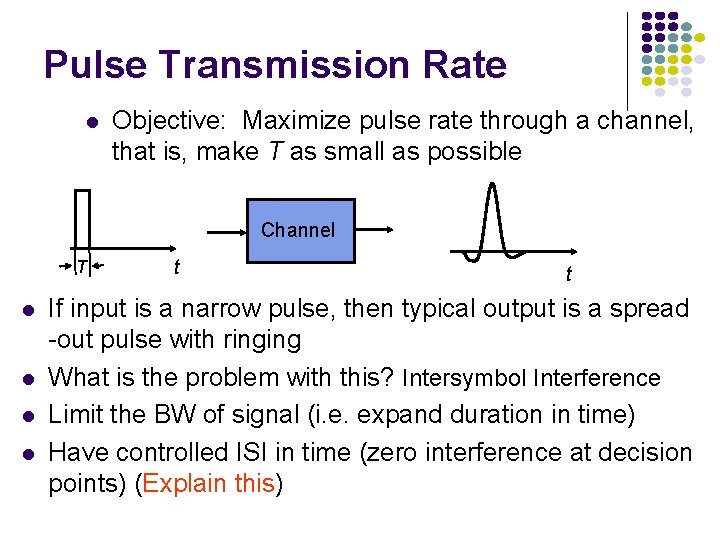

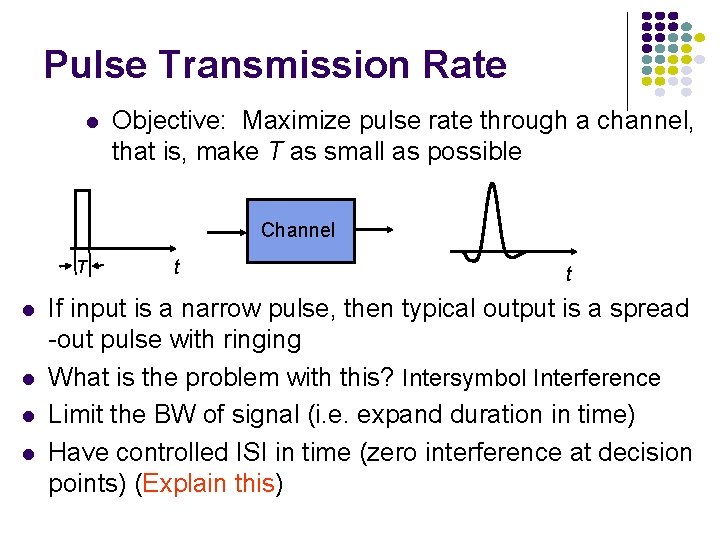

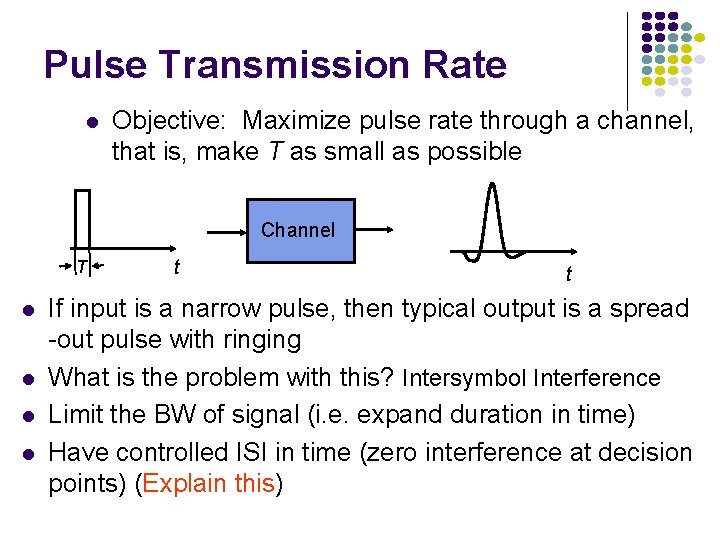

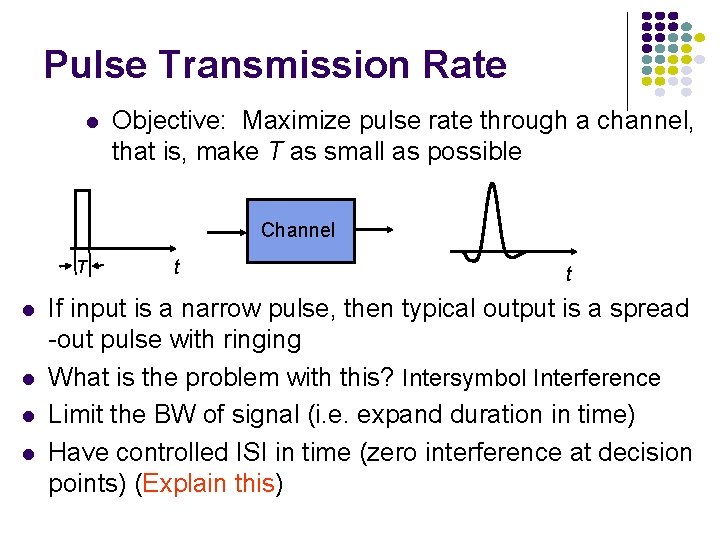

Pulse Transmission Rate Objective: Maximize pulse rate through a channel, that is, make T as small as possible Channel T t t If input is a narrow pulse, then typical output is a spread -out pulse with ringing What is the problem with this? Intersymbol Interference Limit the BW of signal (i. e. expand duration in time) Have controlled ISI in time (zero interference at decision points) (Explain this)

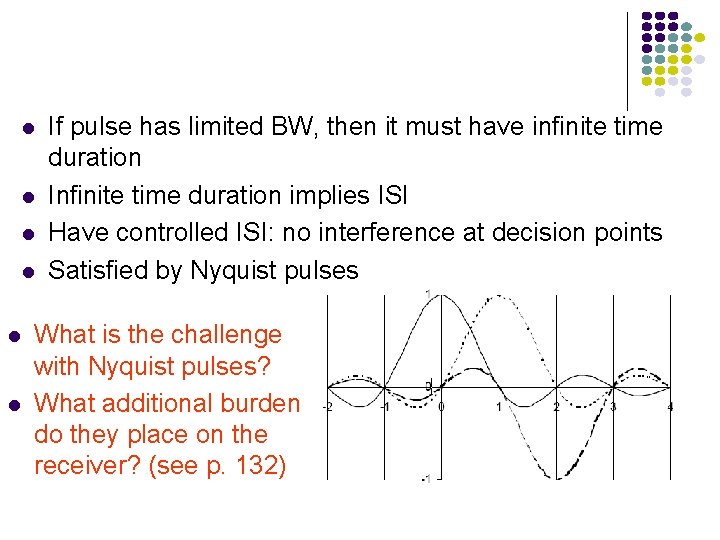

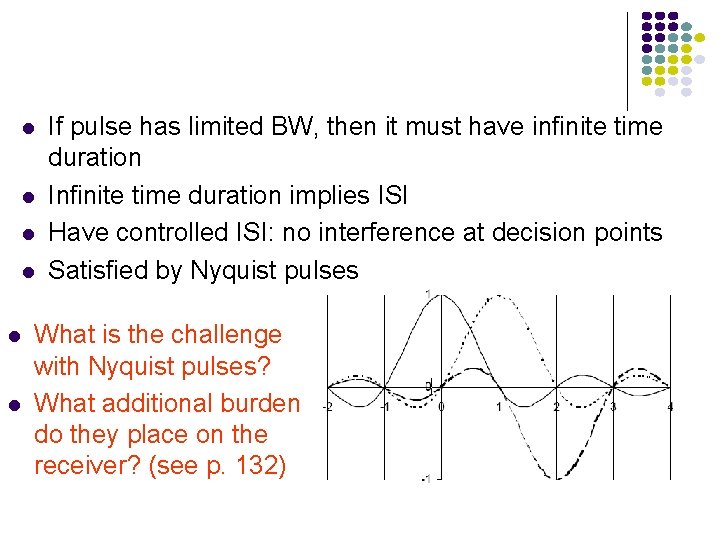

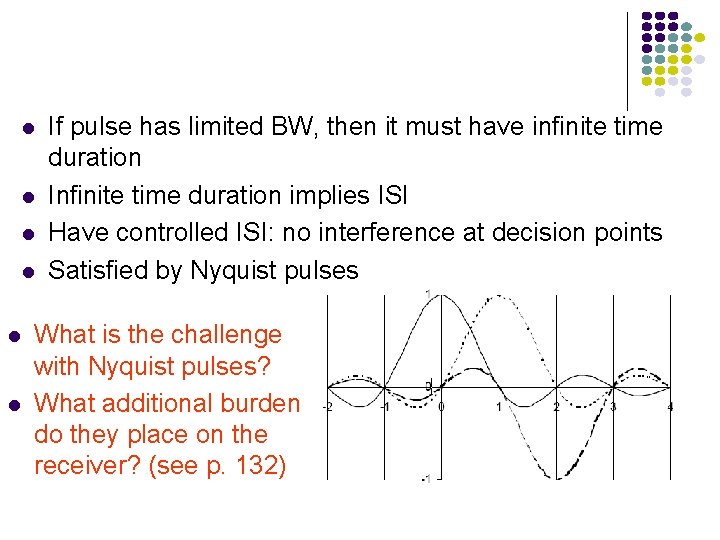

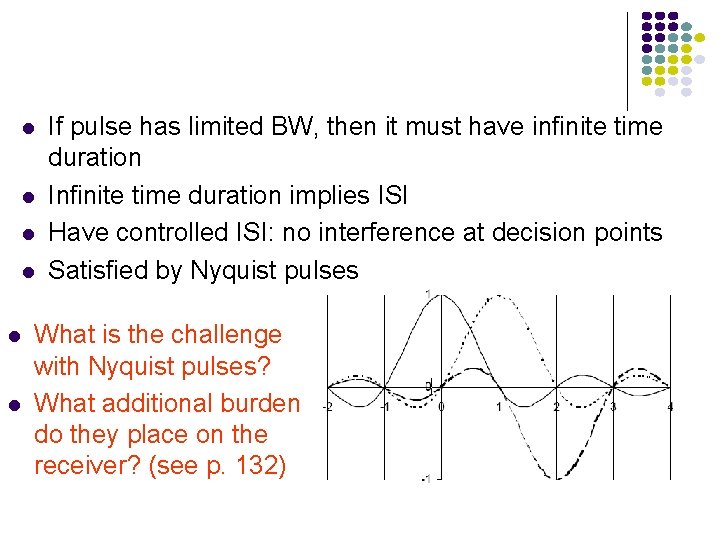

If pulse has limited BW, then it must have infinite time duration Infinite time duration implies ISI Have controlled ISI: no interference at decision points Satisfied by Nyquist pulses What is the challenge with Nyquist pulses? What additional burden do they place on the receiver? (see p. 132)

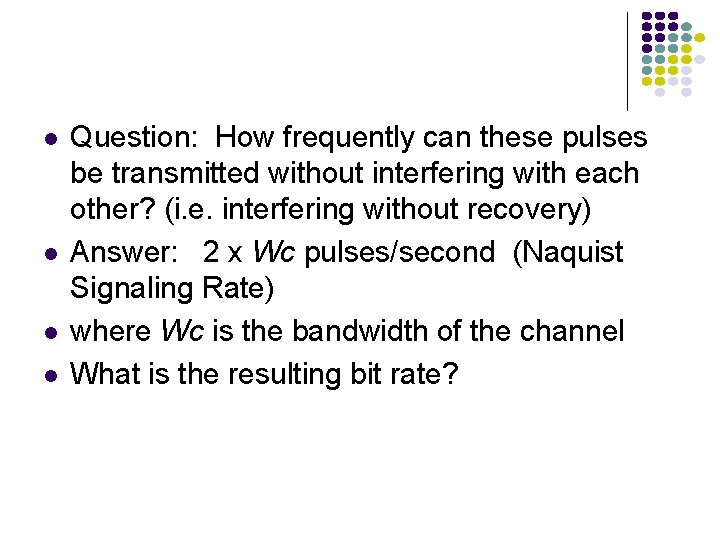

Question: How frequently can these pulses be transmitted without interfering with each other? (i. e. interfering without recovery) Answer: 2 x Wc pulses/second (Naquist Signaling Rate) where Wc is the bandwidth of the channel What is the resulting bit rate?

Multilevel Pulse Transmission Assume channel of bandwidth Wc, and transmit 2 Wc pulses/sec (without interference) If pulses amplitudes are either -A or +A, then each pulse conveys 1 bit, so Bit Rate = 1 bit/pulse x 2 Wc pulses/sec = 2 Wc bps If amplitudes are from {-3 A, -A, +3 A}, then bit rate is 2 x 2 Wc bps By going to M = 2 m amplitude levels, we achieve Bit Rate = m bits/pulse x 2 Wc pulses/sec = 2 m. Wc bps All we care about is that signaling does not exceed 2 Wc Without noise, bit rate capacity is proportional to bandwidth, and can be increased indefinitely (by increasing m).

Noise & Reliable Communications All physical systems have noise Electrons always vibrate at non-zero temperature Motion of electrons induces noise Presence of noise limits accuracy of measurement of received signal amplitude Errors occur if signal separation is comparable to noise level Bit Error Rate (BER) increases with decreasing signal-to-noise ratio Noise places a limit on how many amplitude levels can be used in pulse transmission

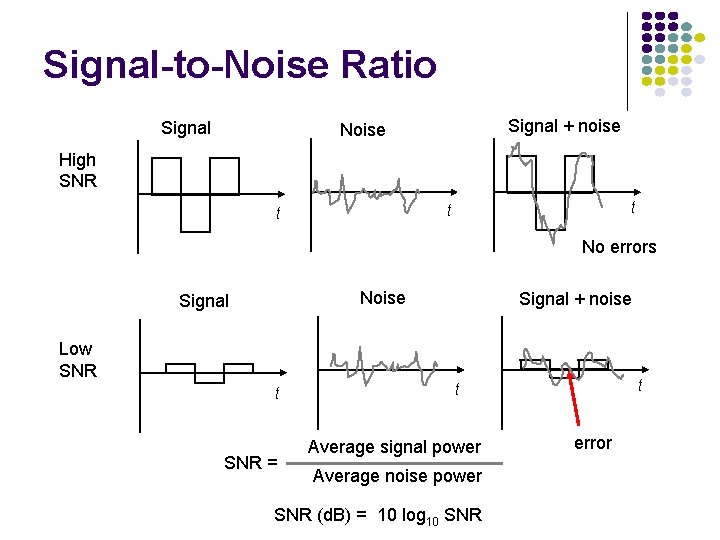

Signal-to-Noise Ratio Signal + noise Noise High SNR t t t No errors Noise Signal + noise Low SNR t SNR = t t Average signal power Average noise power SNR (d. B) = 10 log 10 SNR error

Multilevel Pulse Transmission What happens if we increase number of levels while keeping maximum signal levels fixed at A? Reduce spacing between levels Increase the probability of having a detection error Can not increase the number of levels (bit rate) without compromising reliability

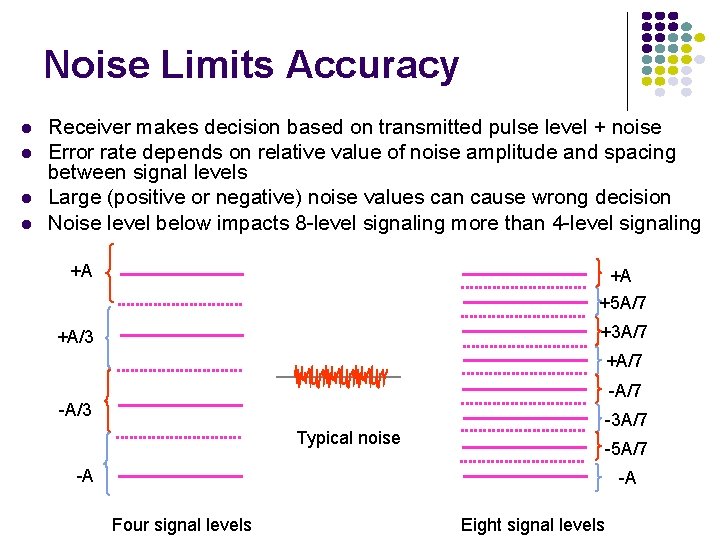

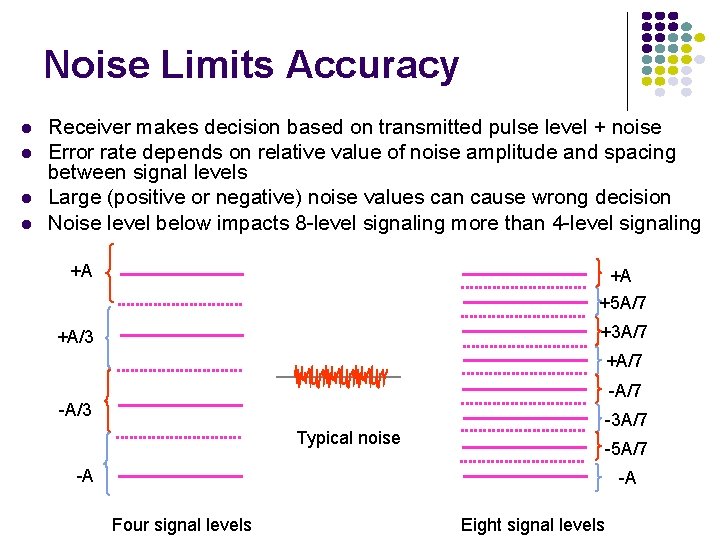

Noise Limits Accuracy Receiver makes decision based on transmitted pulse level + noise Error rate depends on relative value of noise amplitude and spacing between signal levels Large (positive or negative) noise values can cause wrong decision Noise level below impacts 8 -level signaling more than 4 -level signaling +A +A +5 A/7 +A/3 +3 A/7 +A/7 -A/3 -3 A/7 Typical noise -5 A/7 -A -A Four signal levels Eight signal levels

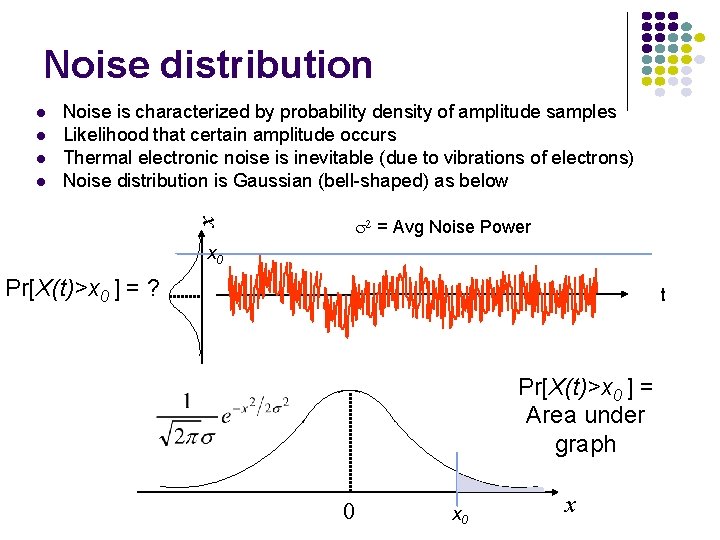

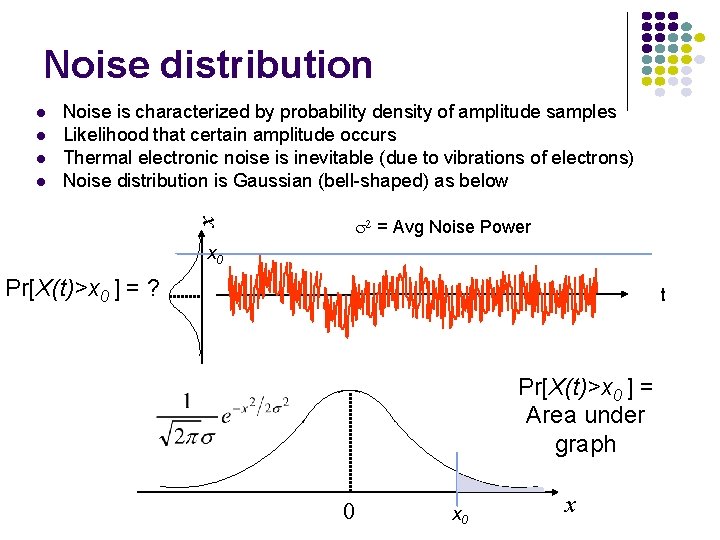

Noise distribution 2 = Avg Noise Power x Noise is characterized by probability density of amplitude samples Likelihood that certain amplitude occurs Thermal electronic noise is inevitable (due to vibrations of electrons) Noise distribution is Gaussian (bell-shaped) as below x 0 Pr[X(t)>x 0 ] = ? t Pr[X(t)>x 0 ] = Area under graph 0 x

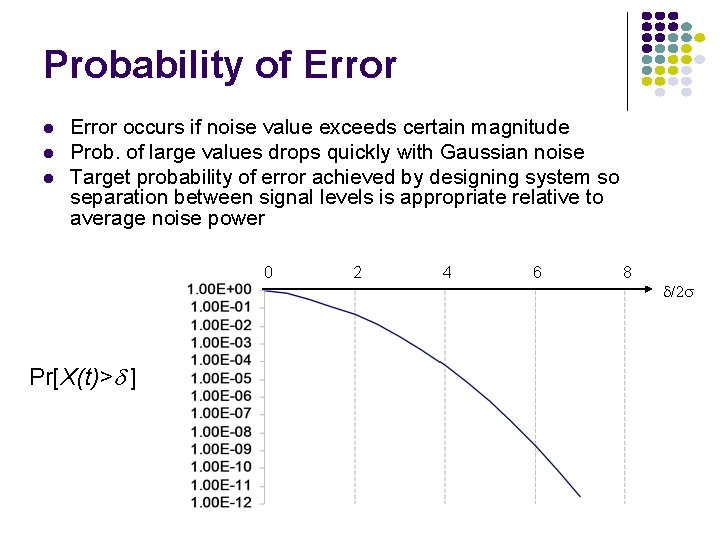

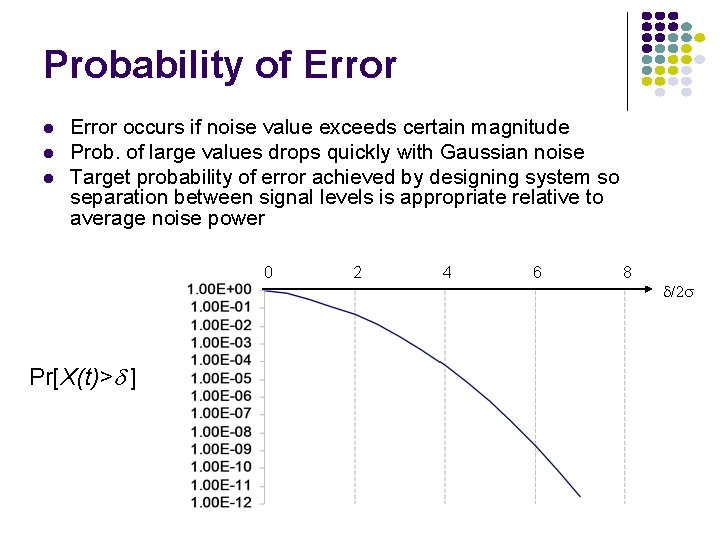

Probability of Error occurs if noise value exceeds certain magnitude Prob. of large values drops quickly with Gaussian noise Target probability of error achieved by designing system so separation between signal levels is appropriate relative to average noise power 0 Pr[X(t)>d ] 2 4 6 8 /2

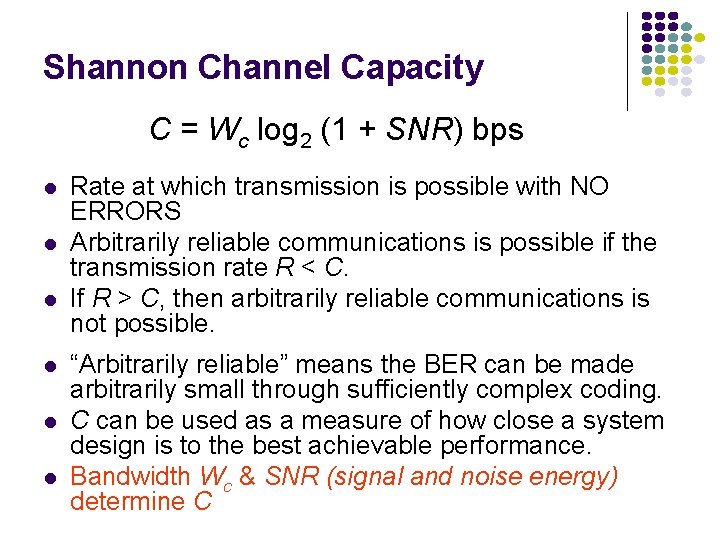

Shannon Channel Capacity C = Wc log 2 (1 + SNR) bps Rate at which transmission is possible with NO ERRORS Arbitrarily reliable communications is possible if the transmission rate R < C. If R > C, then arbitrarily reliable communications is not possible. “Arbitrarily reliable” means the BER can be made arbitrarily small through sufficiently complex coding. C can be used as a measure of how close a system design is to the best achievable performance. Bandwidth Wc & SNR (signal and noise energy) determine C

Example Find the Shannon channel capacity for a telephone channel with Wc = 3400 Hz and SNR = 10000 C = 3400 log 2 (1 + 10000) = 3400 log 10 (10001)/log 102 = 45200 bps Note that SNR = 10000 corresponds to SNR (d. B) = 10 log 10(10001) = 40 d. B

How many signaling levels are required? C = 2 W log_2(M) 45200 = 2 x 3400 x log_2(M) So M approximately 100 levels

Chapter 3 Digital Transmission Fundamentals Baseband Line Coding and Bandpass Digital Modulation

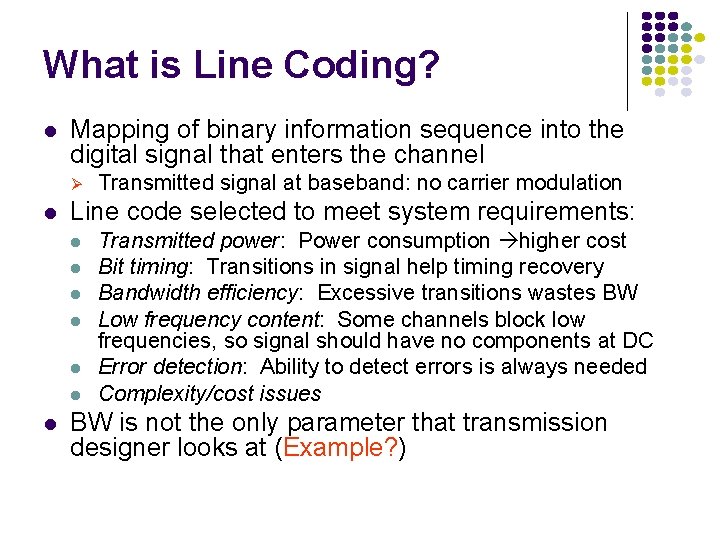

What is Line Coding? Mapping of binary information sequence into the digital signal that enters the channel Ø Line code selected to meet system requirements: Transmitted signal at baseband: no carrier modulation Transmitted power: Power consumption higher cost Bit timing: Transitions in signal help timing recovery Bandwidth efficiency: Excessive transitions wastes BW Low frequency content: Some channels block low frequencies, so signal should have no components at DC Error detection: Ability to detect errors is always needed Complexity/cost issues BW is not the only parameter that transmission designer looks at (Example? )

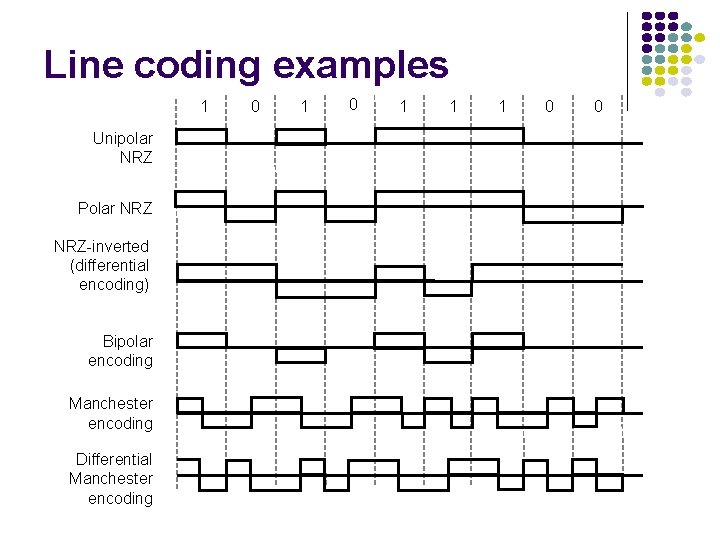

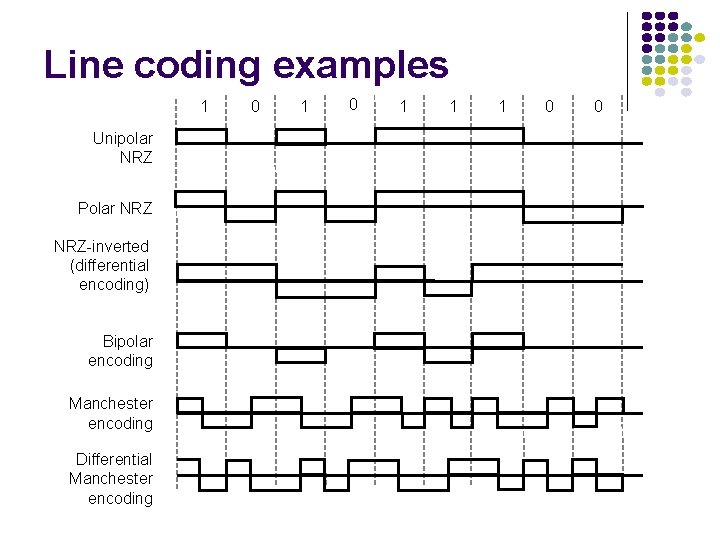

Line coding examples 1 Unipolar NRZ Polar NRZ-inverted (differential encoding) Bipolar encoding Manchester encoding Differential Manchester encoding 0 1 1 1 0 0

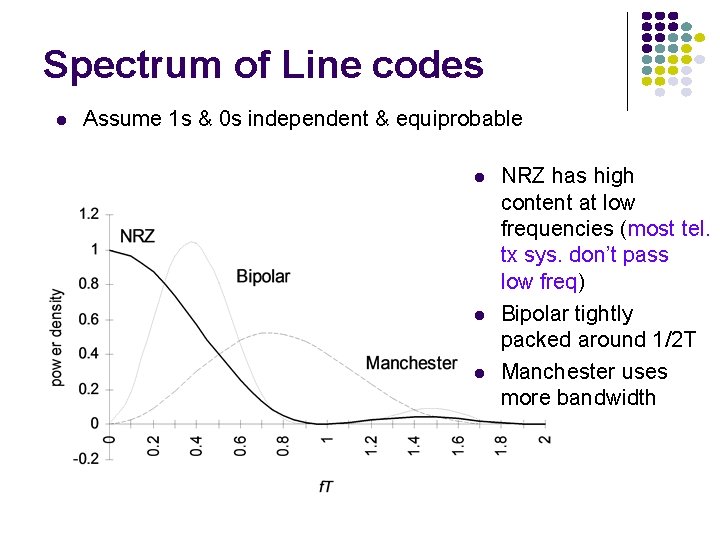

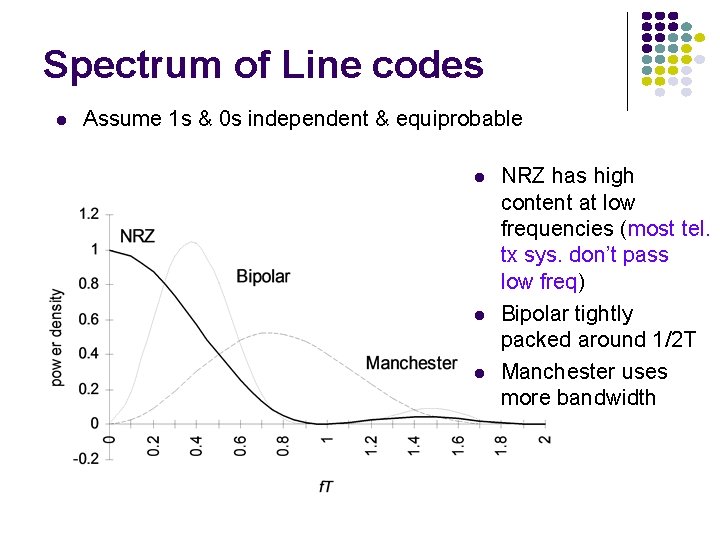

Spectrum of Line codes Assume 1 s & 0 s independent & equiprobable NRZ has high content at low frequencies (most tel. tx sys. don’t pass low freq) Bipolar tightly packed around 1/2 T Manchester uses more bandwidth

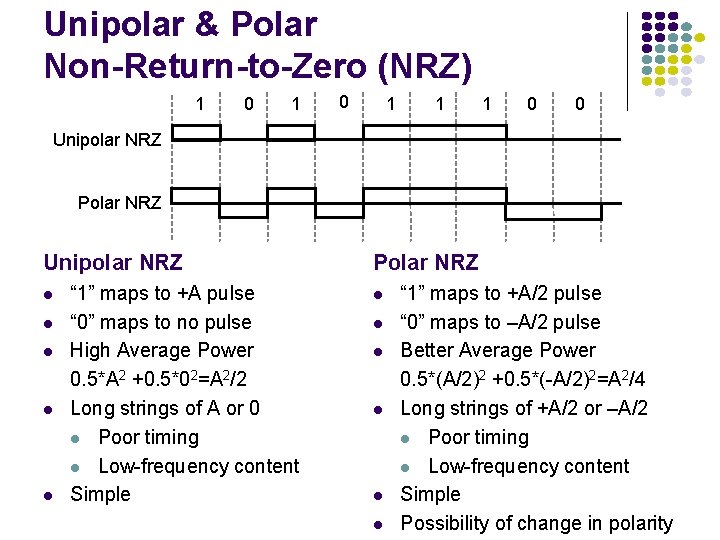

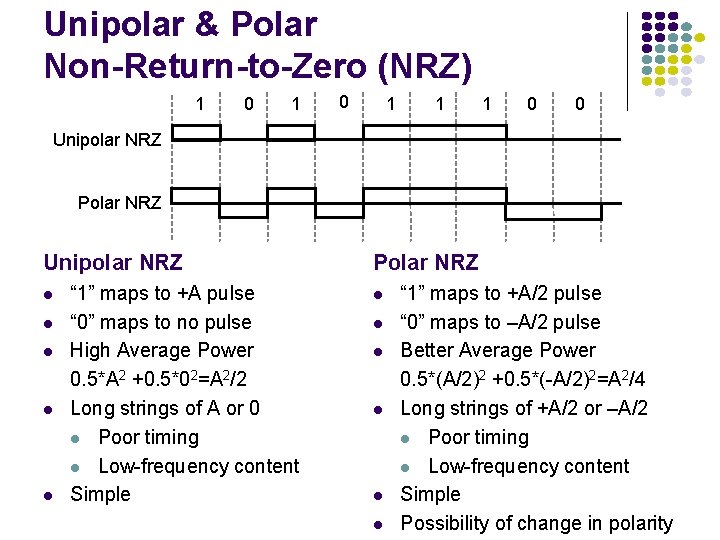

Unipolar & Polar Non-Return-to-Zero (NRZ) 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 Unipolar NRZ Polar NRZ Unipolar NRZ “ 1” maps to +A pulse “ 0” maps to no pulse High Average Power 0. 5*A 2 +0. 5*02=A 2/2 Long strings of A or 0 Poor timing Low-frequency content Simple Polar NRZ “ 1” maps to +A/2 pulse “ 0” maps to –A/2 pulse Better Average Power 0. 5*(A/2)2 +0. 5*(-A/2)2=A 2/4 Long strings of +A/2 or –A/2 Poor timing Low-frequency content Simple Possibility of change in polarity

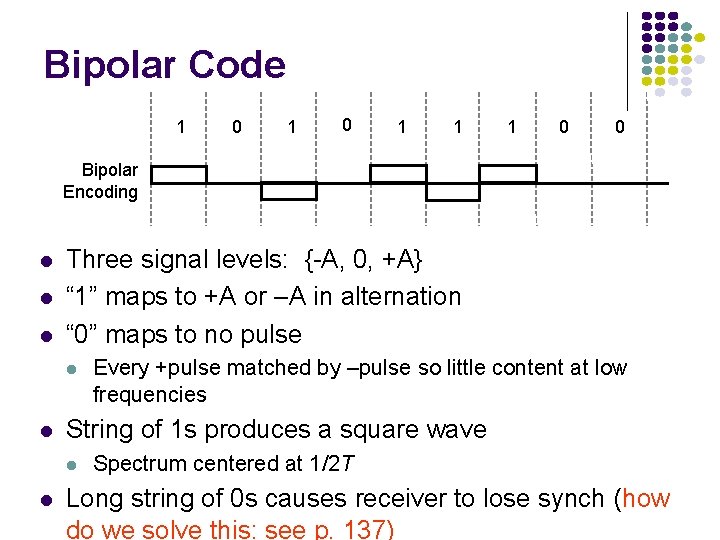

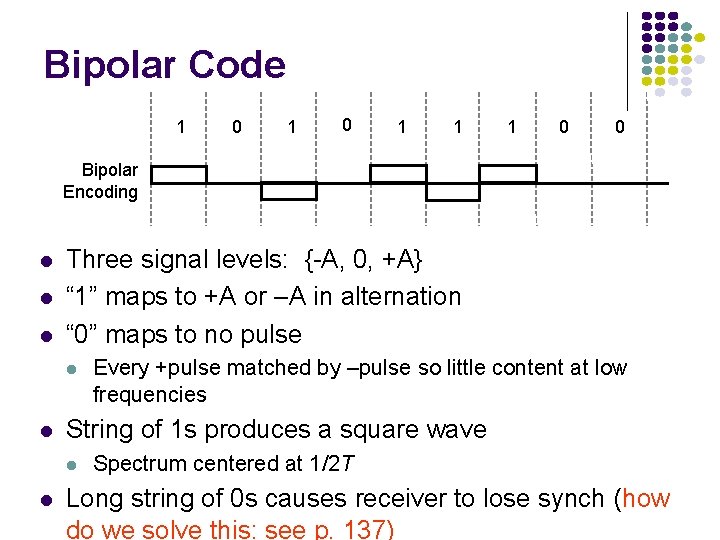

Bipolar Code 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 Bipolar Encoding Three signal levels: {-A, 0, +A} “ 1” maps to +A or –A in alternation “ 0” maps to no pulse String of 1 s produces a square wave Every +pulse matched by –pulse so little content at low frequencies Spectrum centered at 1/2 T Long string of 0 s causes receiver to lose synch (how do we solve this: see p. 137)

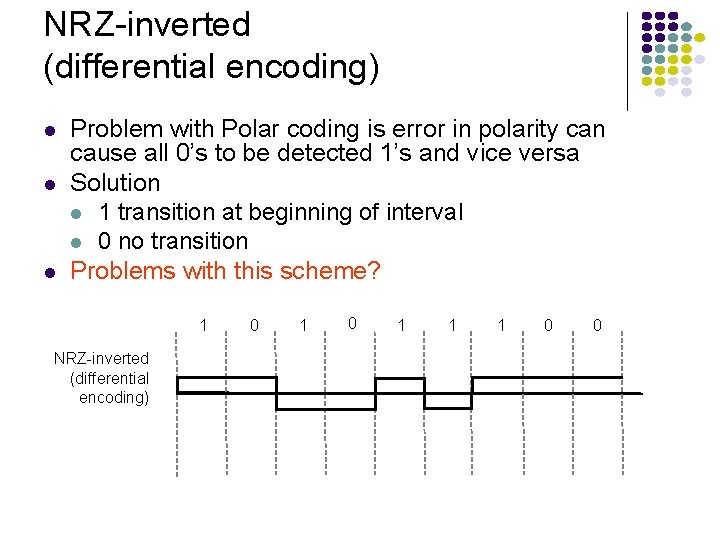

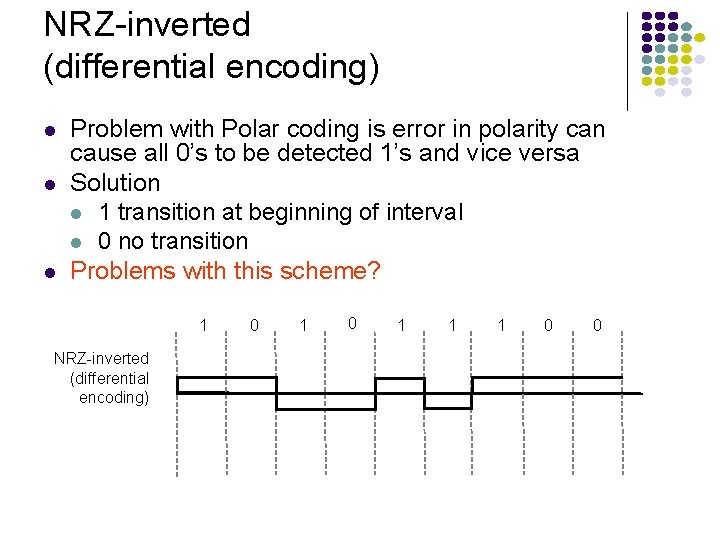

NRZ-inverted (differential encoding) Problem with Polar coding is error in polarity can cause all 0’s to be detected 1’s and vice versa Solution 1 transition at beginning of interval 0 no transition Problems with this scheme? 1 NRZ-inverted (differential encoding) 0 1 1 1 0 0

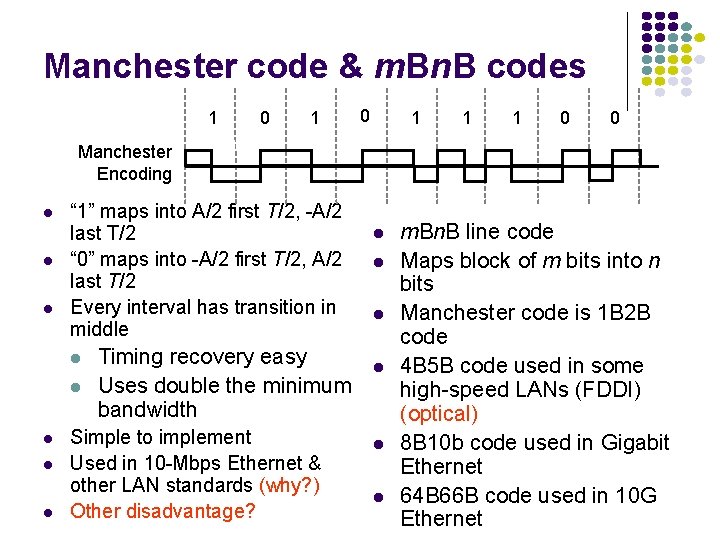

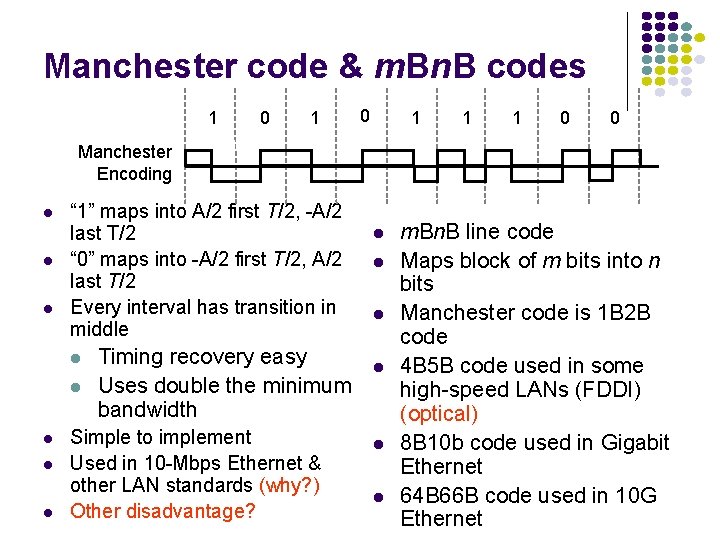

Manchester code & m. Bn. B codes 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 Manchester Encoding “ 1” maps into A/2 first T/2, -A/2 last T/2 “ 0” maps into -A/2 first T/2, A/2 last T/2 Every interval has transition in middle Timing recovery easy Uses double the minimum bandwidth Simple to implement Used in 10 -Mbps Ethernet & other LAN standards (why? ) Other disadvantage? m. Bn. B line code Maps block of m bits into n bits Manchester code is 1 B 2 B code 4 B 5 B code used in some high-speed LANs (FDDI) (optical) 8 B 10 b code used in Gigabit Ethernet 64 B 66 B code used in 10 G Ethernet

Chapter 3 Digital Transmission Fundamentals Band-pass Digital Modulation

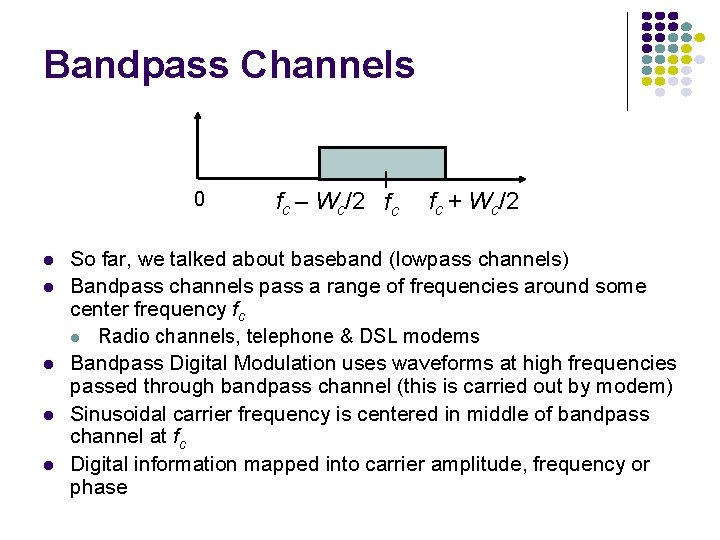

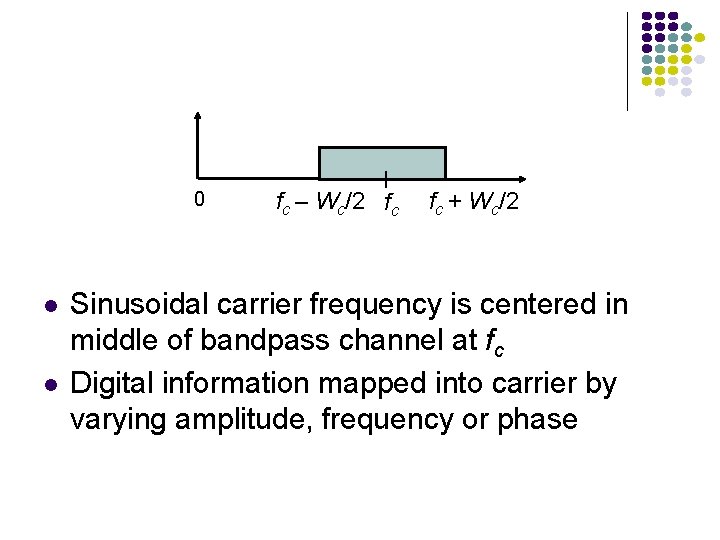

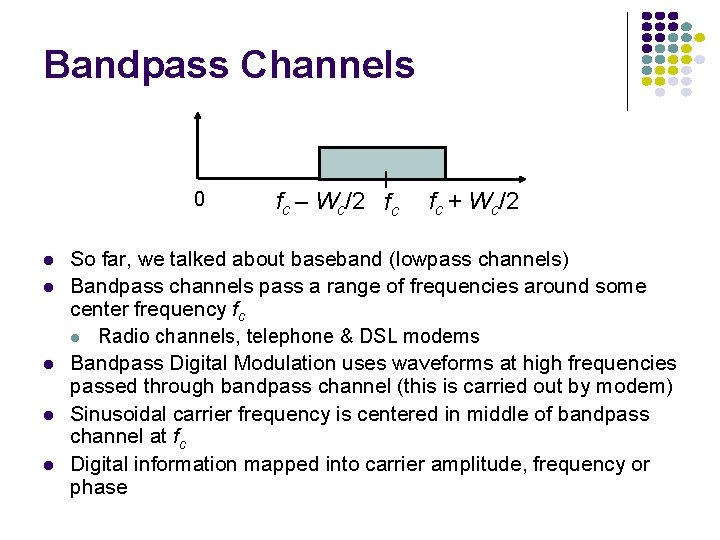

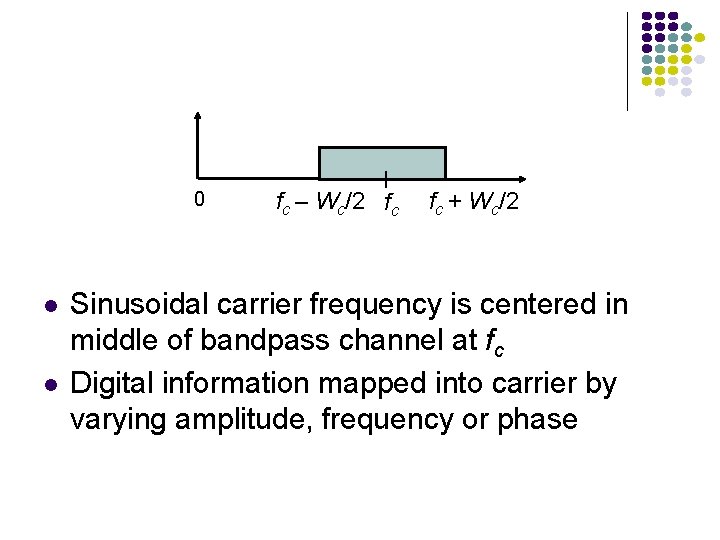

Bandpass Channels 0 fc – Wc/2 fc fc + Wc/2 So far, we talked about baseband (lowpass channels) Bandpass channels pass a range of frequencies around some center frequency fc Radio channels, telephone & DSL modems Bandpass Digital Modulation uses waveforms at high frequencies passed through bandpass channel (this is carried out by modem) Sinusoidal carrier frequency is centered in middle of bandpass channel at fc Digital information mapped into carrier amplitude, frequency or phase

0 fc – Wc/2 fc fc + Wc/2 Sinusoidal carrier frequency is centered in middle of bandpass channel at fc Digital information mapped into carrier by varying amplitude, frequency or phase

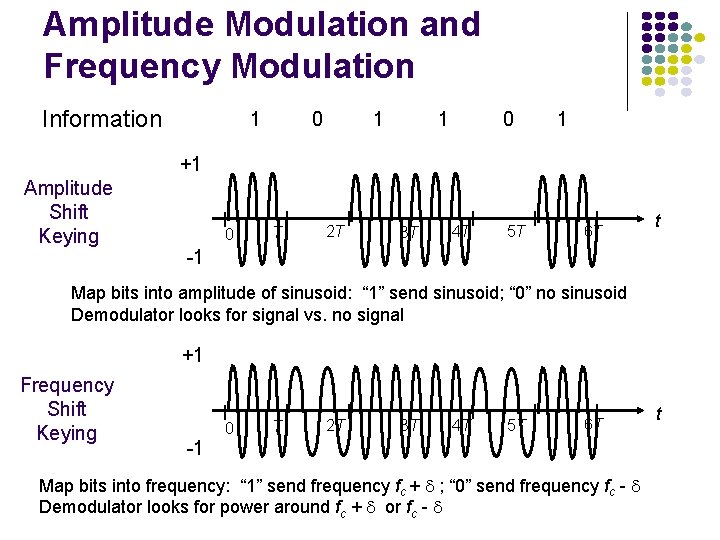

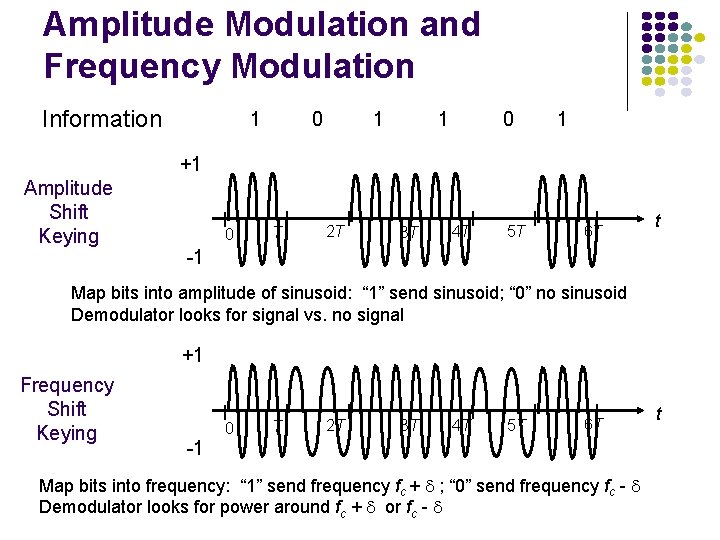

Amplitude Modulation and Frequency Modulation Information 1 0 1 +1 Amplitude Shift Keying 0 T 2 T 3 T 4 T 5 T 6 T t -1 Map bits into amplitude of sinusoid: “ 1” send sinusoid; “ 0” no sinusoid Demodulator looks for signal vs. no signal +1 Frequency Shift Keying 0 T 2 T 3 T 4 T 5 T 6 T -1 Map bits into frequency: “ 1” send frequency fc + ; “ 0” send frequency fc - Demodulator looks for power around fc + or fc - t

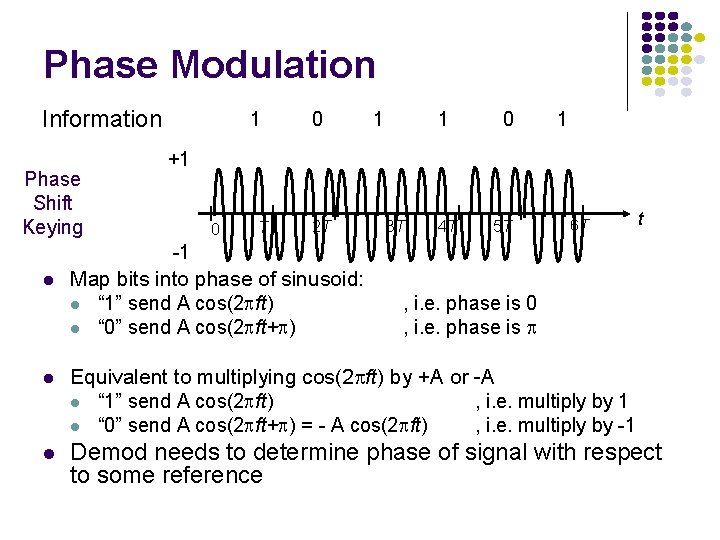

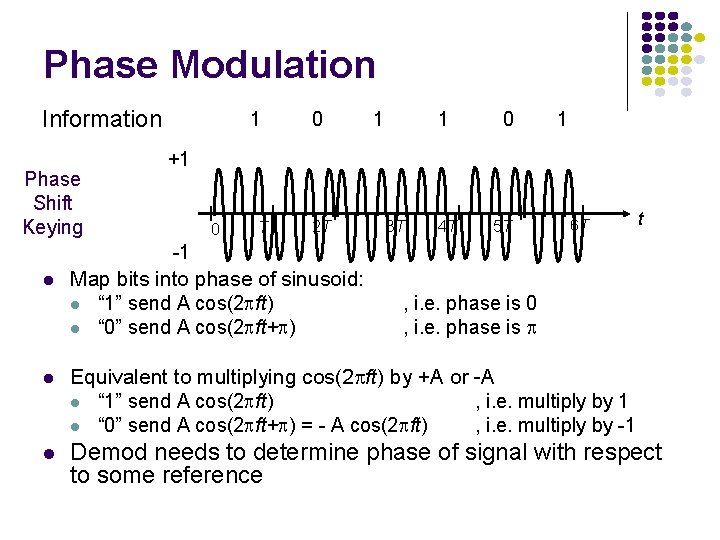

Phase Modulation Information Phase Shift Keying 1 0 1 +1 0 T 2 T 3 T 4 T 5 T 6 T t -1 Map bits into phase of sinusoid: “ 1” send A cos(2 ft) “ 0” send A cos(2 ft+ ) , i. e. phase is 0 , i. e. phase is Equivalent to multiplying cos(2 ft) by +A or -A “ 1” send A cos(2 ft) , i. e. multiply by 1 “ 0” send A cos(2 ft+ ) = - A cos(2 ft) , i. e. multiply by -1 Demod needs to determine phase of signal with respect to some reference

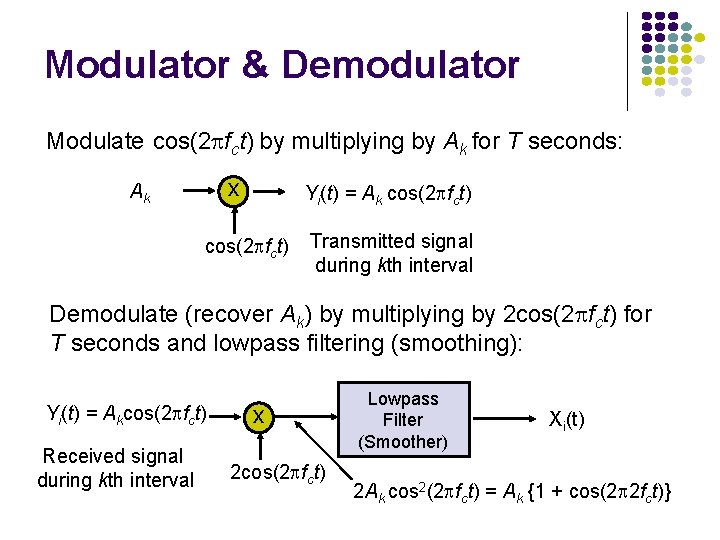

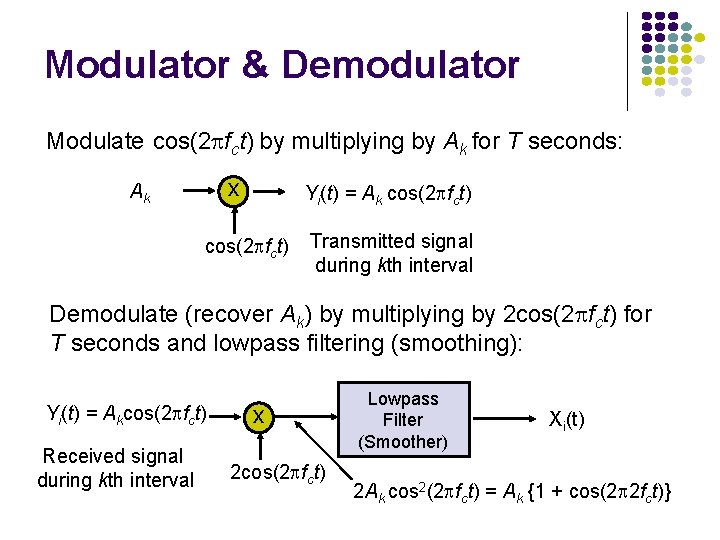

Modulator & Demodulator Modulate cos(2 fct) by multiplying by Ak for T seconds: x Ak Yi(t) = Ak cos(2 fct) Transmitted signal during kth interval Demodulate (recover Ak) by multiplying by 2 cos(2 fct) for T seconds and lowpass filtering (smoothing): Yi(t) = Akcos(2 fct) Received signal during kth interval x 2 cos(2 fct) Lowpass Filter (Smoother) Xi(t) 2 Ak cos 2(2 fct) = Ak {1 + cos(2 2 fct)}

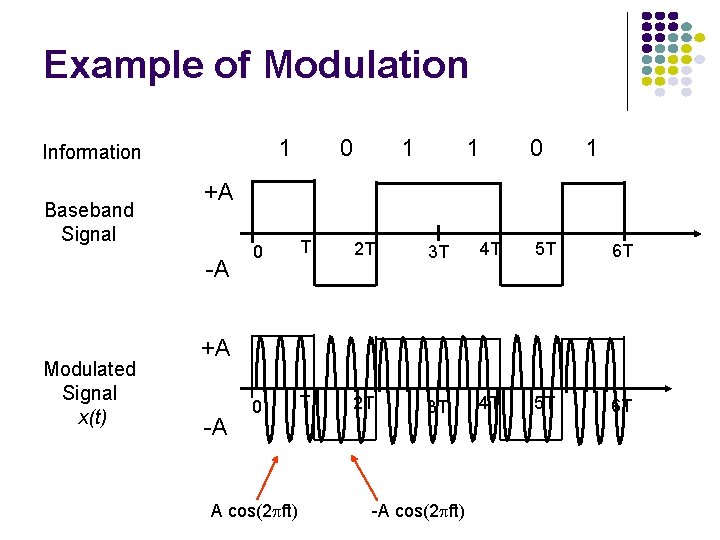

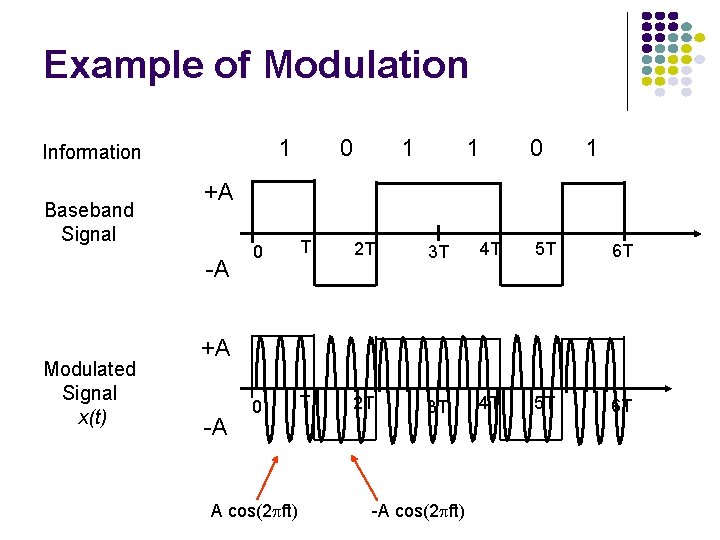

Example of Modulation 1 Information Baseband Signal 1 1 0 1 +A -A Modulated Signal x(t) 0 0 T 2 T 3 T 4 T 5 T 6 T +A -A A cos(2 ft) -A cos(2 ft)

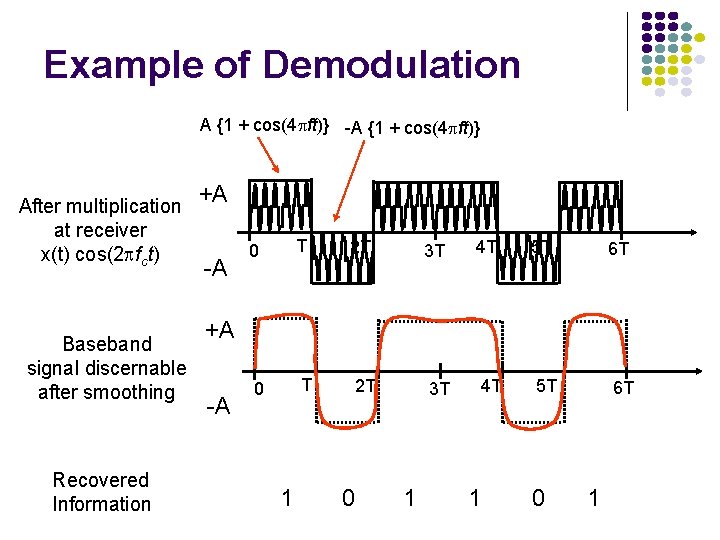

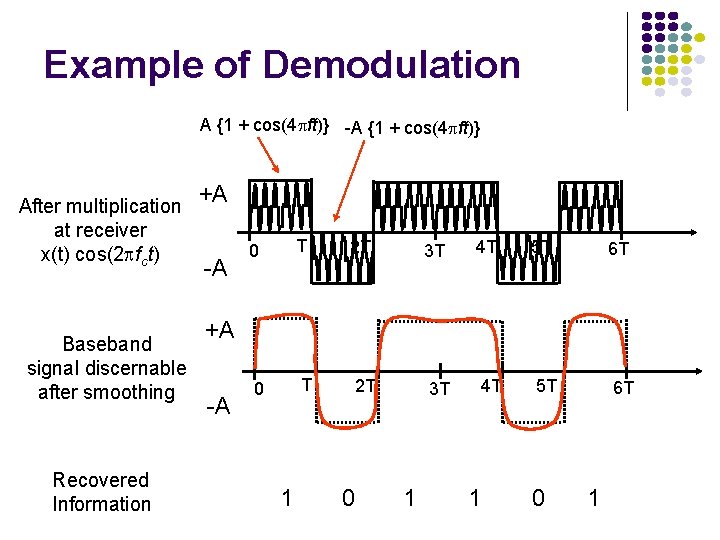

Example of Demodulation A {1 + cos(4 ft)} -A {1 + cos(4 ft)} After multiplication at receiver x(t) cos(2 fct) Baseband signal discernable after smoothing Recovered Information +A -A 0 T 2 T 3 T 4 T 5 T 6 T +A -A 1 0 1

Pulse Transmission Rate Objective: Maximize pulse rate through a channel, that is, make T as small as possible Channel T t t If input is a narrow pulse, then typical output is a spread -out pulse with ringing What is the problem with this? Intersymbol Interference Limit the BW of signal (i. e. expand duration in time) Have controlled ISI in time (zero interference at decision points) (Explain this)

If pulse has limited BW, then it must have infinite time duration Infinite time duration implies ISI Have controlled ISI: no interference at decision points Satisfied by Nyquist pulses What is the challenge with Nyquist pulses? What additional burden do they place on the receiver? (see p. 132)

Question: How frequently can these pulses be transmitted without interfering with each other? (i. e. interfering without recovery) Answer: 2 x Wc pulses/second (Naquist Signaling Rate) where Wc is the bandwidth of the channel What is the resulting bit rate?

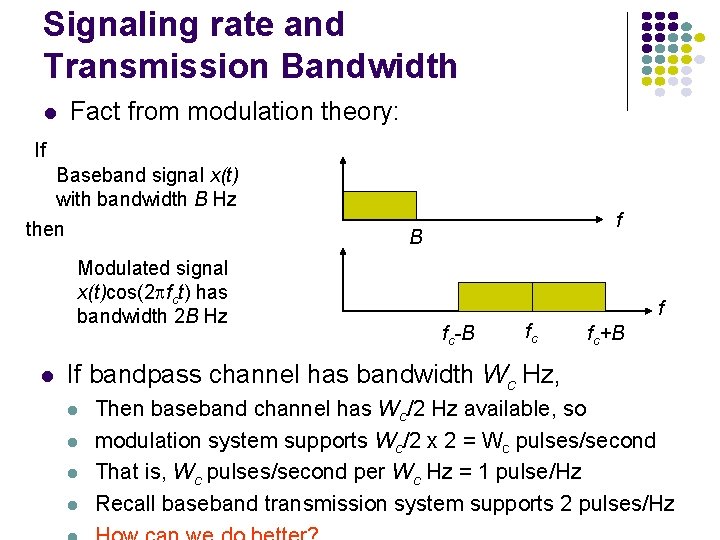

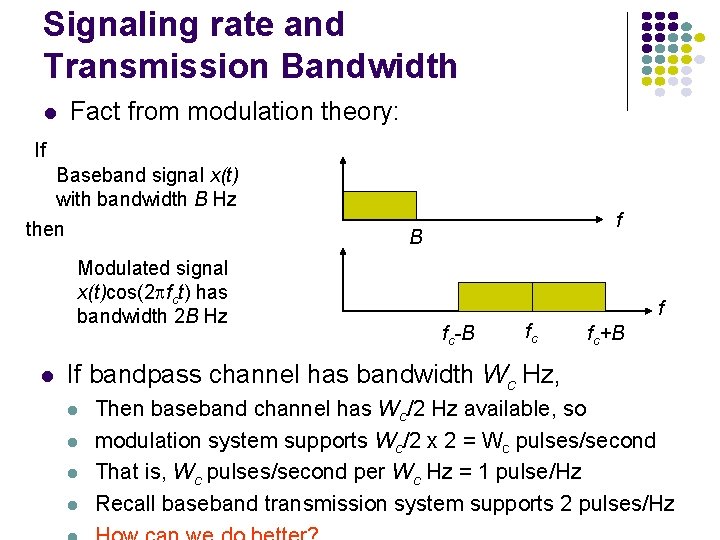

Signaling rate and Transmission Bandwidth Fact from modulation theory: If Baseband signal x(t) with bandwidth B Hz then Modulated signal x(t)cos(2 fct) has bandwidth 2 B Hz f B f fc-B fc fc+B If bandpass channel has bandwidth Wc Hz, Then baseband channel has Wc/2 Hz available, so modulation system supports Wc/2 x 2 = Wc pulses/second That is, Wc pulses/second per Wc Hz = 1 pulse/Hz Recall baseband transmission system supports 2 pulses/Hz

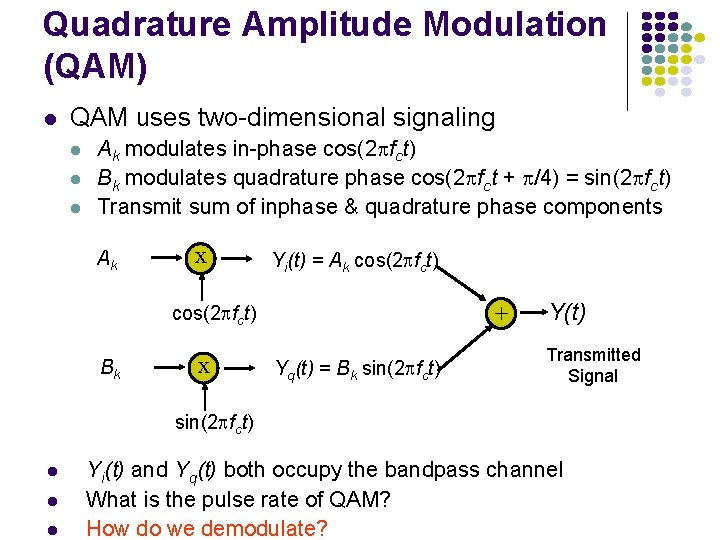

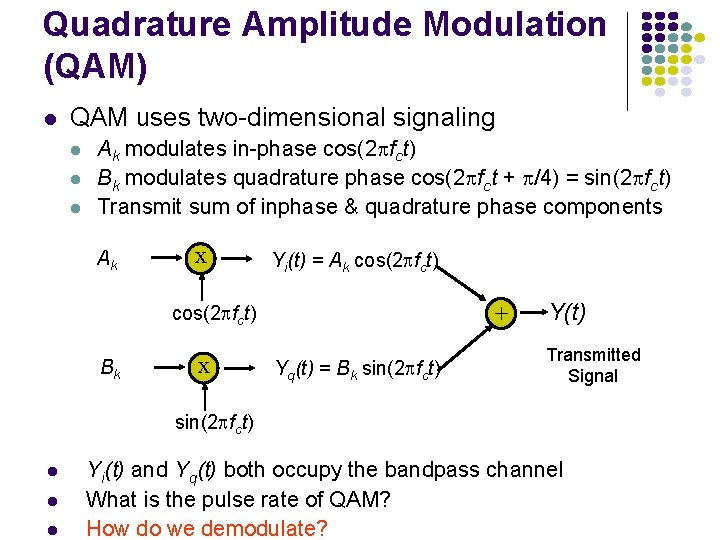

Quadrature Amplitude Modulation (QAM) QAM uses two-dimensional signaling Ak modulates in-phase cos(2 fct) Bk modulates quadrature phase cos(2 fct + /4) = sin(2 fct) Transmit sum of inphase & quadrature phase components Ak x Yi(t) = Ak cos(2 fct) + cos(2 fct) Bk x Yq(t) = Bk sin(2 fct) Y(t) Transmitted Signal sin(2 fct) Yi(t) and Yq(t) both occupy the bandpass channel What is the pulse rate of QAM? How do we demodulate?

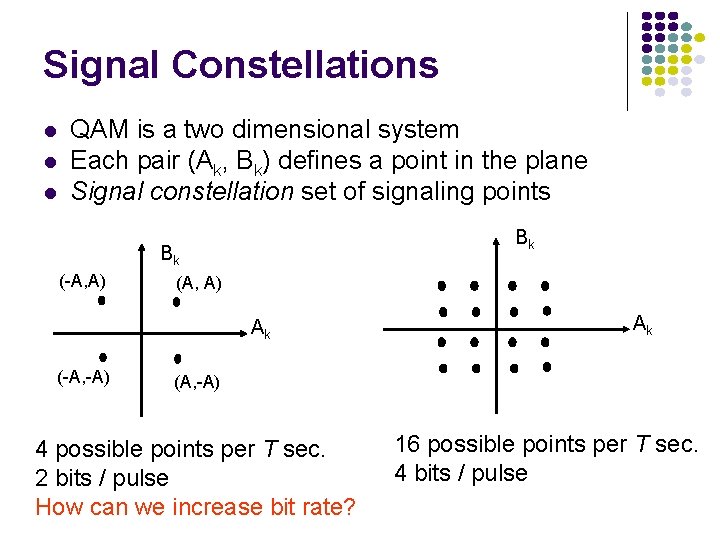

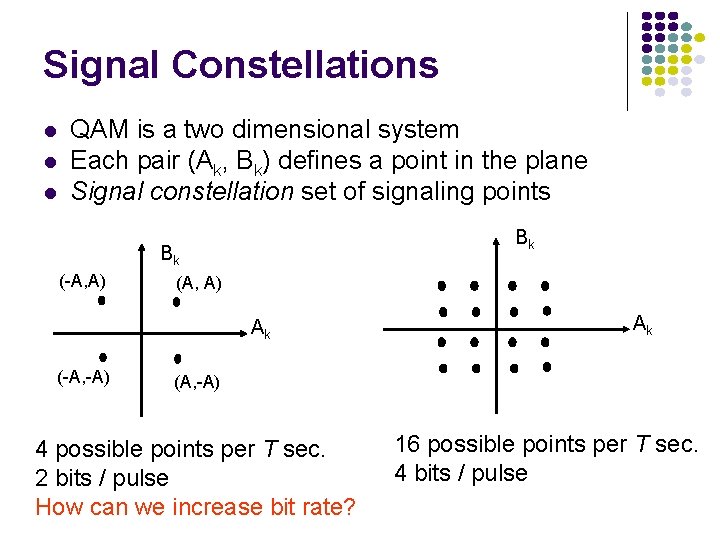

Signal Constellations QAM is a two dimensional system Each pair (Ak, Bk) defines a point in the plane Signal constellation set of signaling points Bk Bk (-A, A) (A, A) Ak (-A, -A) Ak (A, -A) 4 possible points per T sec. 2 bits / pulse How can we increase bit rate? 16 possible points per T sec. 4 bits / pulse

Chapter 3 Digital Transmission Fundamentals Properties of Media and Digital Transmission Systems

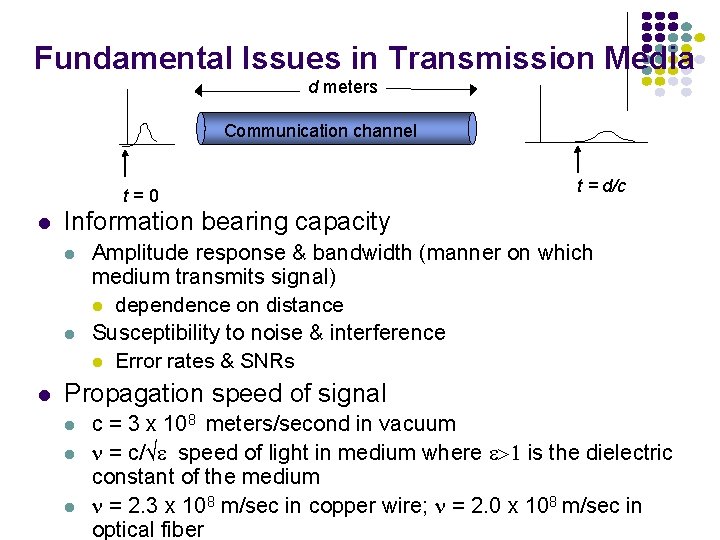

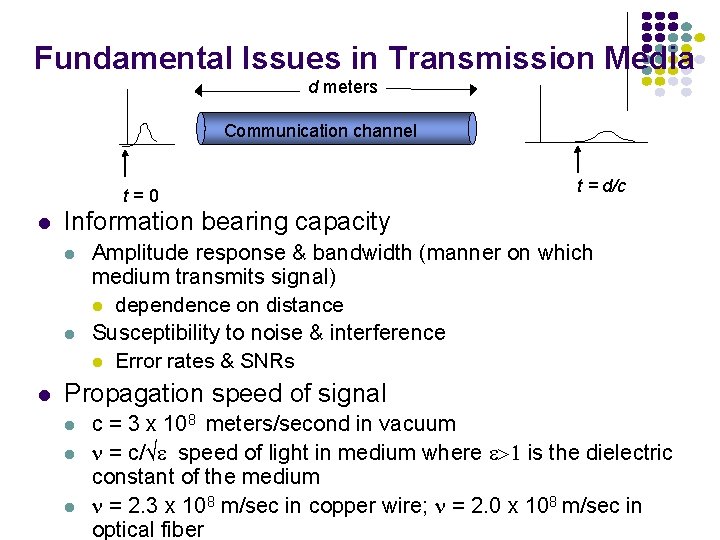

Fundamental Issues in Transmission Media d meters Communication channel t=0 Information bearing capacity t = d/c Amplitude response & bandwidth (manner on which medium transmits signal) dependence on distance Susceptibility to noise & interference Error rates & SNRs Propagation speed of signal c = 3 x 108 meters/second in vacuum n = c/√e speed of light in medium where e>1 is the dielectric constant of the medium n = 2. 3 x 108 m/sec in copper wire; n = 2. 0 x 108 m/sec in optical fiber

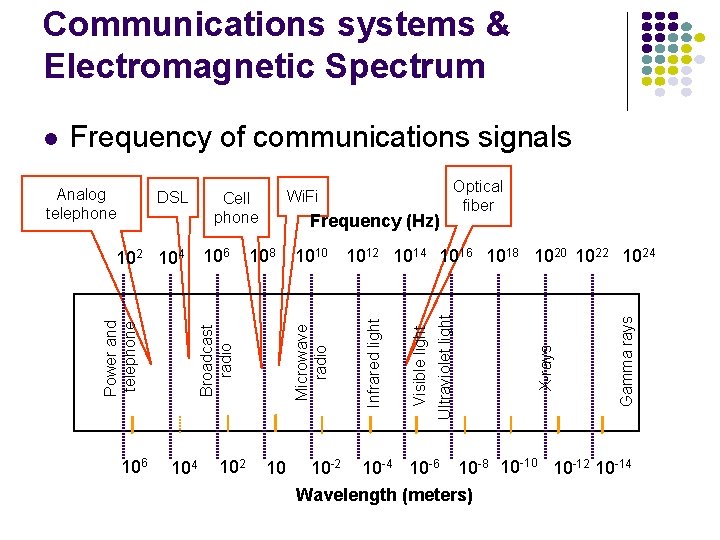

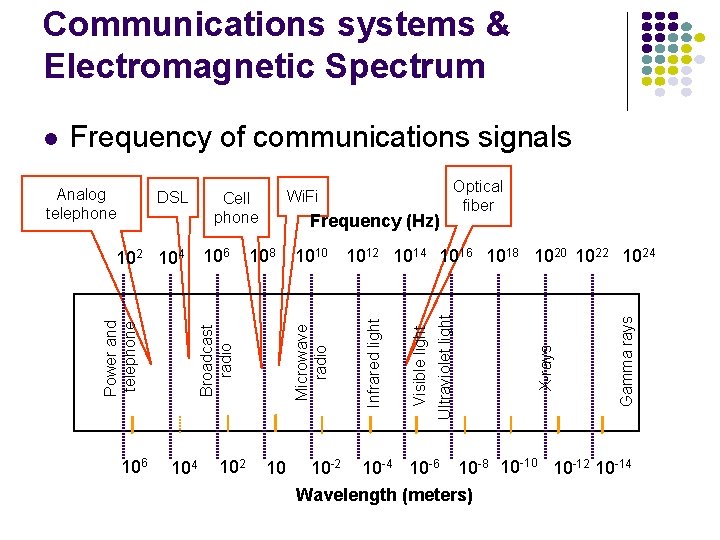

Communications systems & Electromagnetic Spectrum Frequency of communications signals 104 102 10 Gamma rays 1010 1012 1014 1016 1018 1020 1022 1024 X-rays 108 Optical fiber Ultraviolet light Power and telephone Frequency (Hz) Visible light 106 102 104 106 Wi. Fi Cell phone Infrared light DSL Microwave radio Analog telephone Broadcast radio 10 -2 10 -4 10 -6 10 -8 10 -10 10 -12 10 -14 Wavelength (meters)

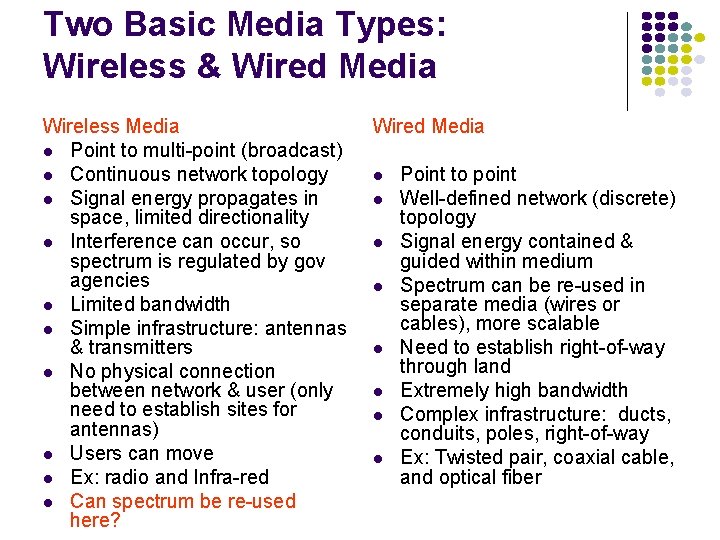

Two Basic Media Types: Wireless & Wired Media Wireless Media Point to multi-point (broadcast) Continuous network topology Signal energy propagates in space, limited directionality Interference can occur, so spectrum is regulated by gov agencies Limited bandwidth Simple infrastructure: antennas & transmitters No physical connection between network & user (only need to establish sites for antennas) Users can move Ex: radio and Infra-red Can spectrum be re-used here? Wired Media Point to point Well-defined network (discrete) topology Signal energy contained & guided within medium Spectrum can be re-used in separate media (wires or cables), more scalable Need to establish right-of-way through land Extremely high bandwidth Complex infrastructure: ducts, conduits, poles, right-of-way Ex: Twisted pair, coaxial cable, and optical fiber

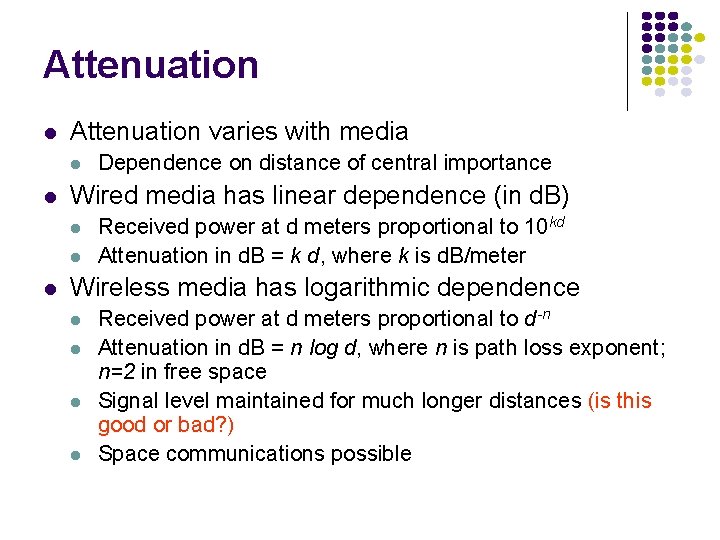

Attenuation varies with media Wired media has linear dependence (in d. B) Dependence on distance of central importance Received power at d meters proportional to 10 kd Attenuation in d. B = k d, where k is d. B/meter Wireless media has logarithmic dependence Received power at d meters proportional to d-n Attenuation in d. B = n log d, where n is path loss exponent; n=2 in free space Signal level maintained for much longer distances (is this good or bad? ) Space communications possible

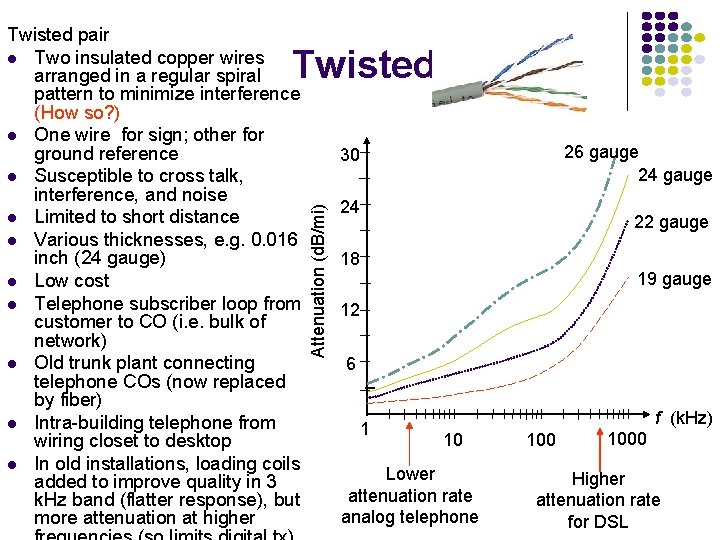

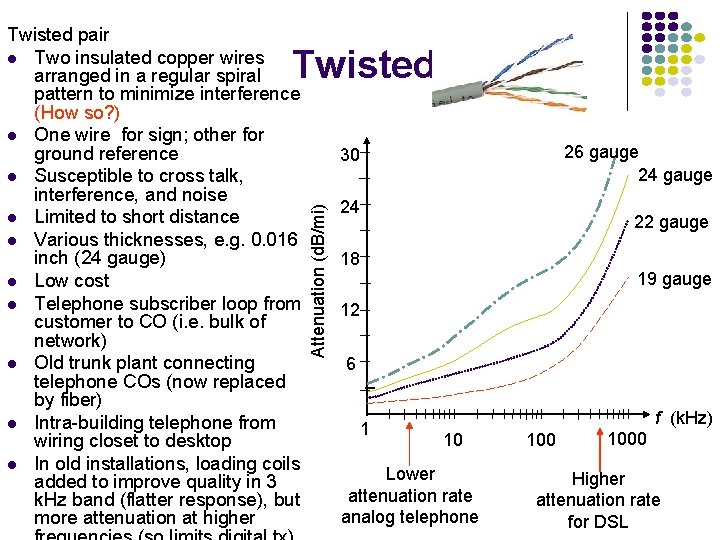

Twisted pair Two insulated copper wires arranged in a regular spiral pattern to minimize interference (How so? ) One wire for sign; other for ground reference Susceptible to cross talk, interference, and noise Limited to short distance Various thicknesses, e. g. 0. 016 inch (24 gauge) Low cost Telephone subscriber loop from customer to CO (i. e. bulk of network) Old trunk plant connecting telephone COs (now replaced by fiber) Intra-building telephone from wiring closet to desktop In old installations, loading coils added to improve quality in 3 k. Hz band (flatter response), but more attenuation at higher Twisted Pair 26 gauge 24 gauge Attenuation (d. B/mi) 30 24 22 gauge 18 19 gauge 12 6 1 f (k. Hz) 10 Lower attenuation rate analog telephone 1000 Higher attenuation rate for DSL

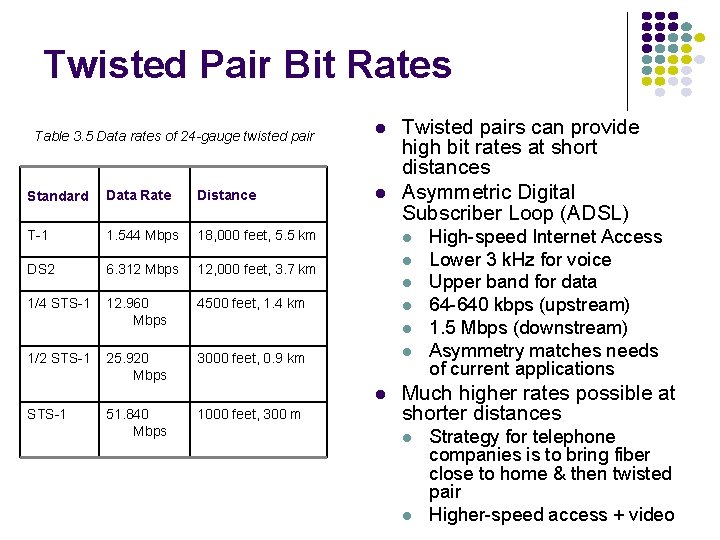

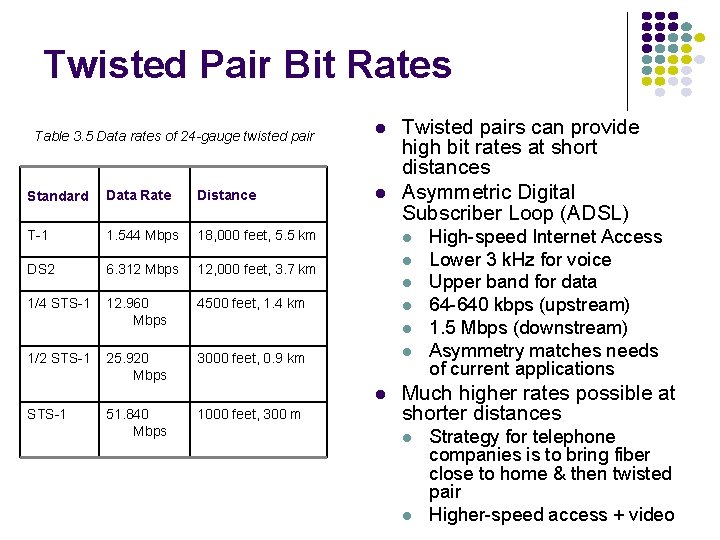

Twisted Pair Bit Rates Table 3. 5 Data rates of 24 -gauge twisted pair Standard Data Rate Distance T-1 1. 544 Mbps 18, 000 feet, 5. 5 km DS 2 6. 312 Mbps 12, 000 feet, 3. 7 km 1/4 STS-1 12. 960 Mbps 4500 feet, 1. 4 km 25. 920 Mbps 3000 feet, 0. 9 km 1/2 STS-1 STS-1 51. 840 Mbps Twisted pairs can provide high bit rates at short distances Asymmetric Digital Subscriber Loop (ADSL) 1000 feet, 300 m High-speed Internet Access Lower 3 k. Hz for voice Upper band for data 64 -640 kbps (upstream) 1. 5 Mbps (downstream) Asymmetry matches needs of current applications Much higher rates possible at shorter distances Strategy for telephone companies is to bring fiber close to home & then twisted pair Higher-speed access + video

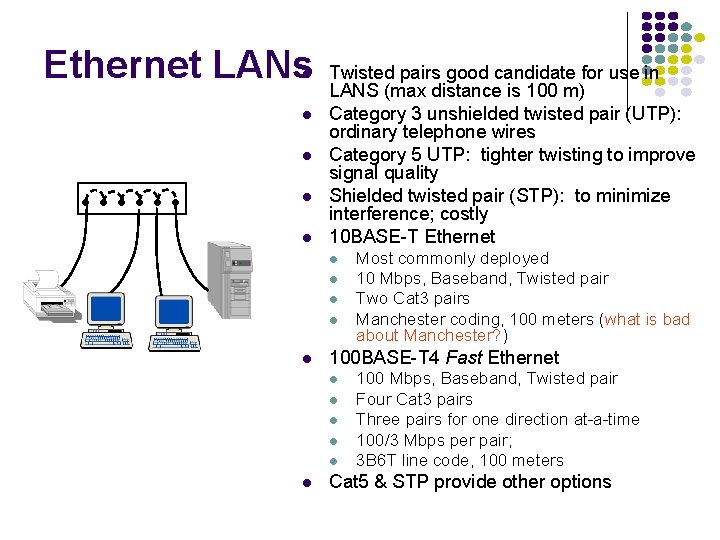

Ethernet LANs Twisted pairs good candidate for use in LANS (max distance is 100 m) Category 3 unshielded twisted pair (UTP): ordinary telephone wires Category 5 UTP: tighter twisting to improve signal quality Shielded twisted pair (STP): to minimize interference; costly 10 BASE-T Ethernet 100 BASE-T 4 Fast Ethernet Most commonly deployed 10 Mbps, Baseband, Twisted pair Two Cat 3 pairs Manchester coding, 100 meters (what is bad about Manchester? ) 100 Mbps, Baseband, Twisted pair Four Cat 3 pairs Three pairs for one direction at-a-time 100/3 Mbps per pair; 3 B 6 T line code, 100 meters Cat 5 & STP provide other options

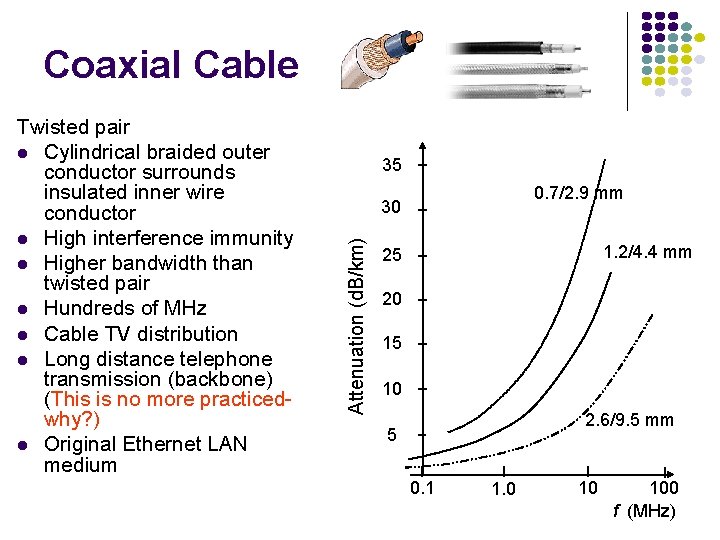

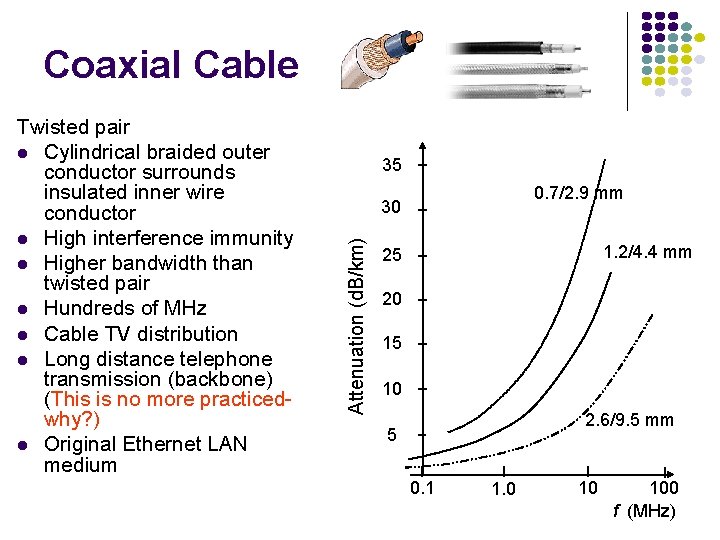

Coaxial Cable 35 0. 7/2. 9 mm 30 Attenuation (d. B/km) Twisted pair Cylindrical braided outer conductor surrounds insulated inner wire conductor High interference immunity Higher bandwidth than twisted pair Hundreds of MHz Cable TV distribution Long distance telephone transmission (backbone) (This is no more practicedwhy? ) Original Ethernet LAN medium 1. 2/4. 4 mm 25 20 15 10 2. 6/9. 5 mm 5 0. 1 1. 0 10 100 f (MHz)

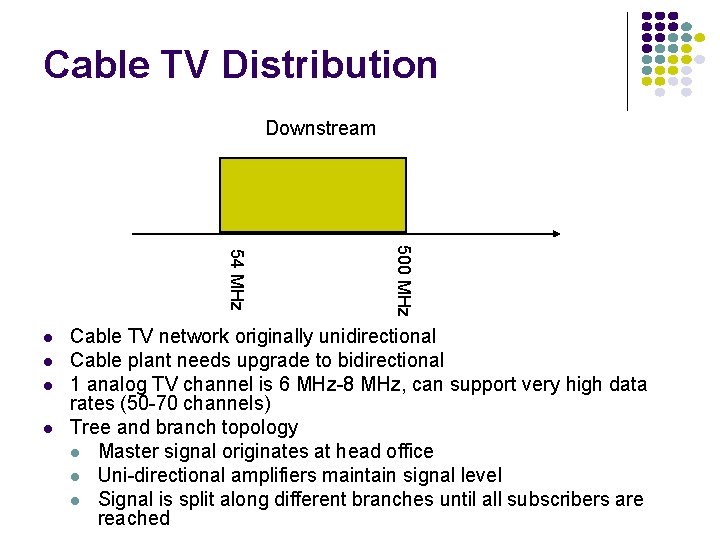

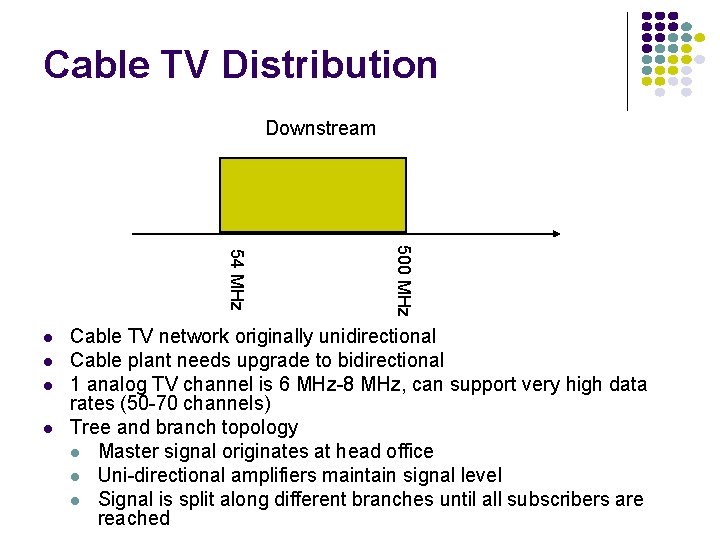

Cable TV Distribution Downstream 500 MHz 54 MHz Cable TV network originally unidirectional Cable plant needs upgrade to bidirectional 1 analog TV channel is 6 MHz-8 MHz, can support very high data rates (50 -70 channels) Tree and branch topology Master signal originates at head office Uni-directional amplifiers maintain signal level Signal is split along different branches until all subscribers are reached

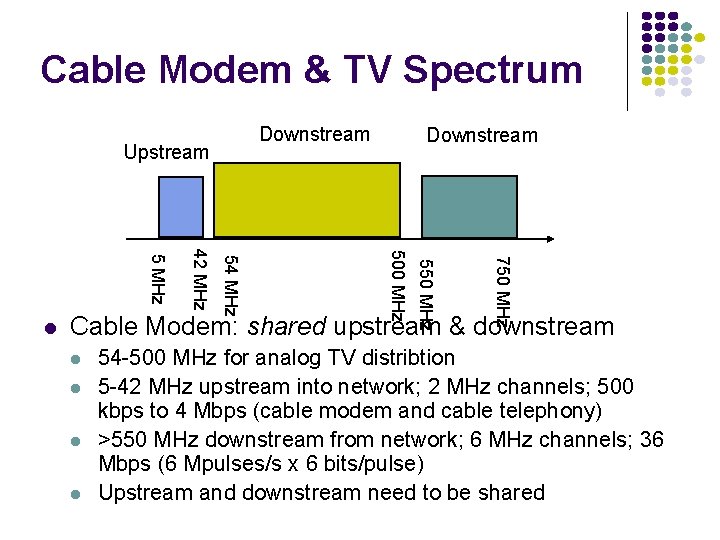

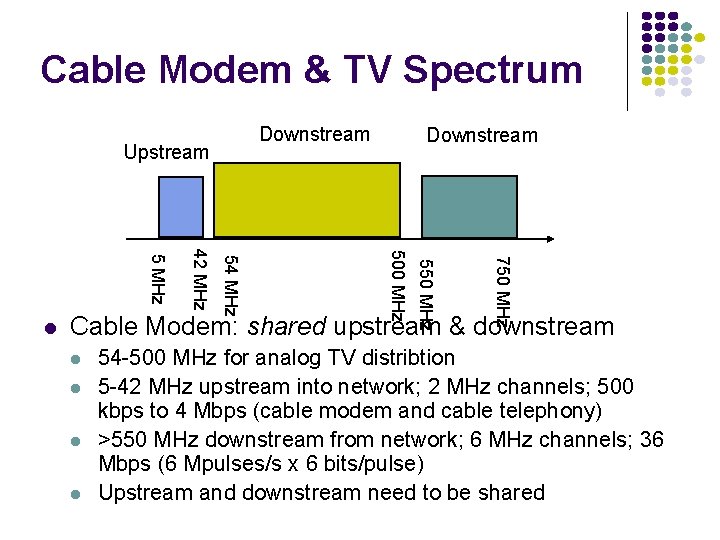

Cable Modem & TV Spectrum Downstream Upstream 750 MHz 500 MHz 54 MHz 42 MHz 5 MHz Downstream Cable Modem: shared upstream & downstream 54 -500 MHz for analog TV distribtion 5 -42 MHz upstream into network; 2 MHz channels; 500 kbps to 4 Mbps (cable modem and cable telephony) >550 MHz downstream from network; 6 MHz channels; 36 Mbps (6 Mpulses/s x 6 bits/pulse) Upstream and downstream need to be shared

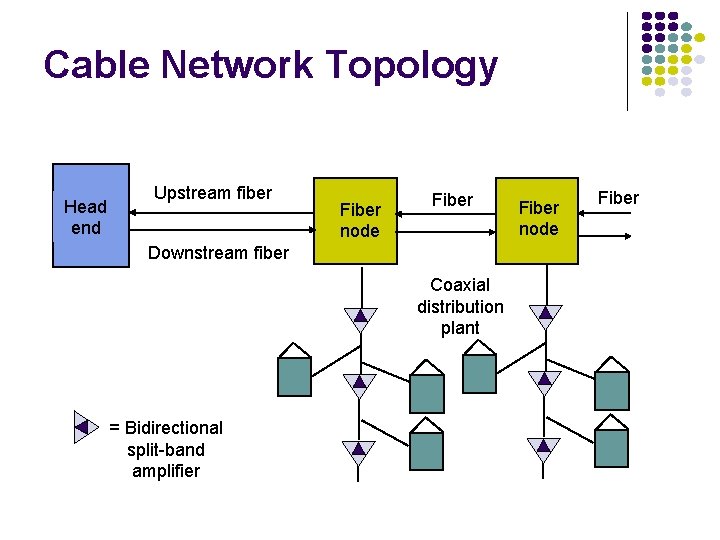

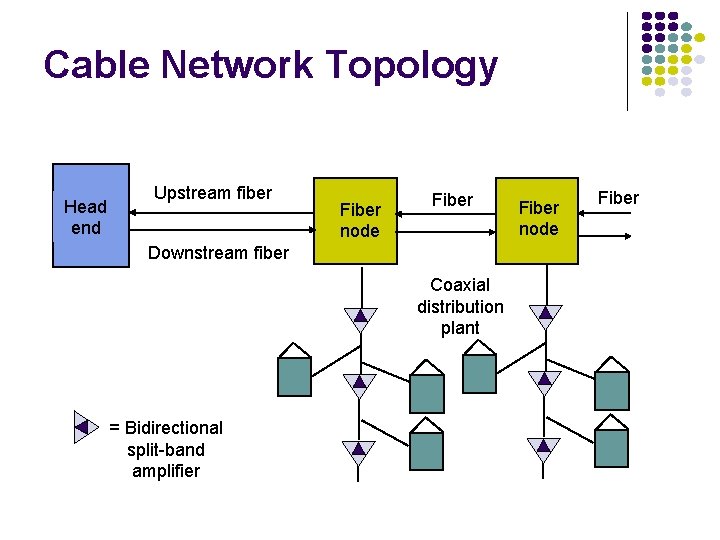

Cable Network Topology Head end Upstream fiber Fiber node Fiber Downstream fiber Coaxial distribution plant = Bidirectional split-band amplifier Fiber node Fiber

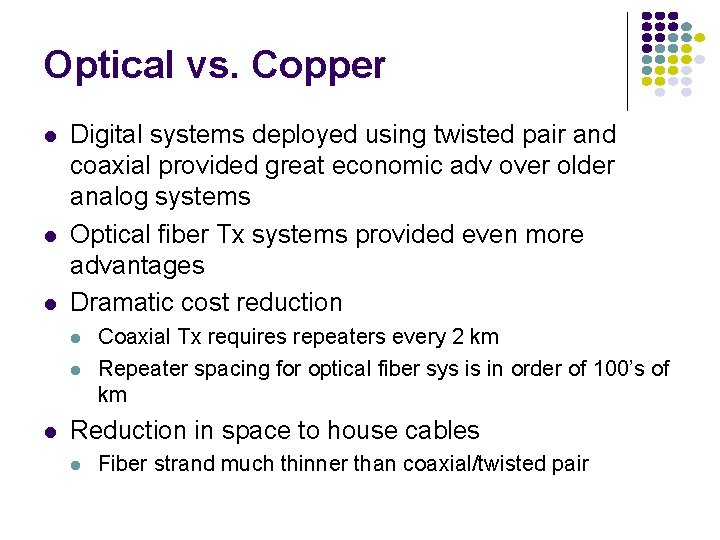

Optical vs. Copper Digital systems deployed using twisted pair and coaxial provided great economic adv over older analog systems Optical fiber Tx systems provided even more advantages Dramatic cost reduction Coaxial Tx requires repeaters every 2 km Repeater spacing for optical fiber sys is in order of 100’s of km Reduction in space to house cables Fiber strand much thinner than coaxial/twisted pair

Optical vs. Copper (2) Much higher BW Less Noise and Interference Single optical fiber can replace many copper cables Fiber does not radiate energy Fiber does pick up interference from external sources More secure from tapping

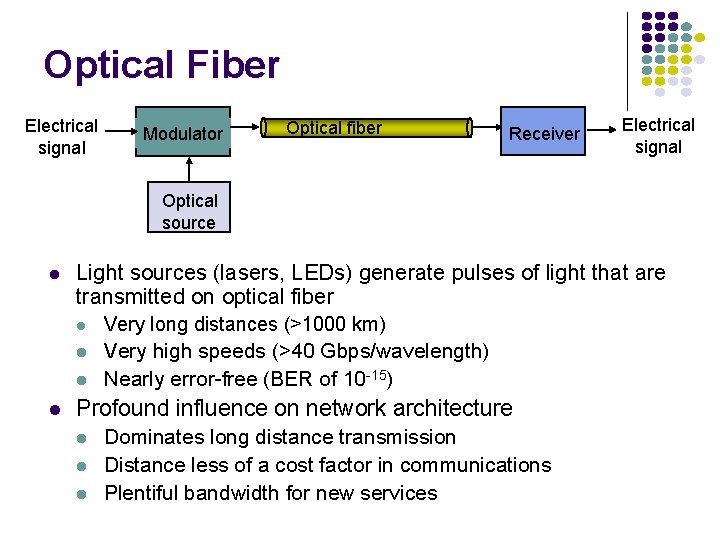

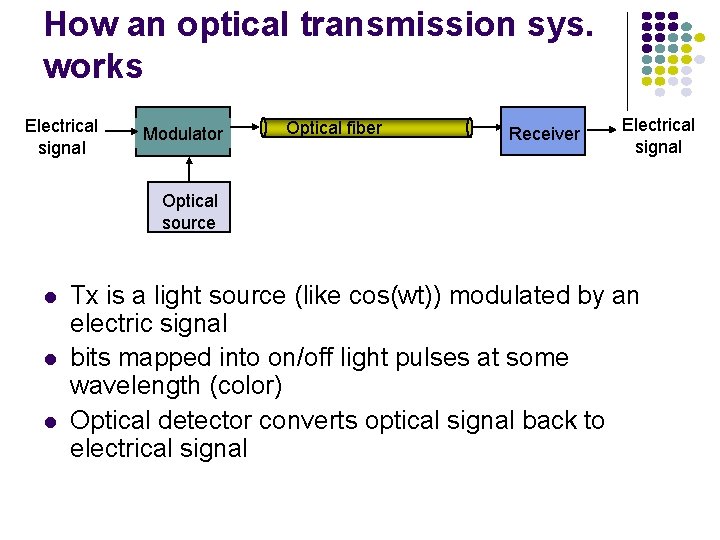

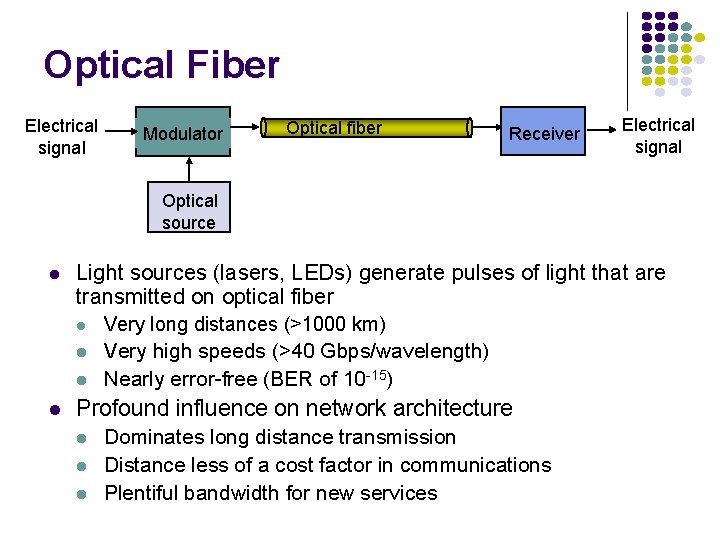

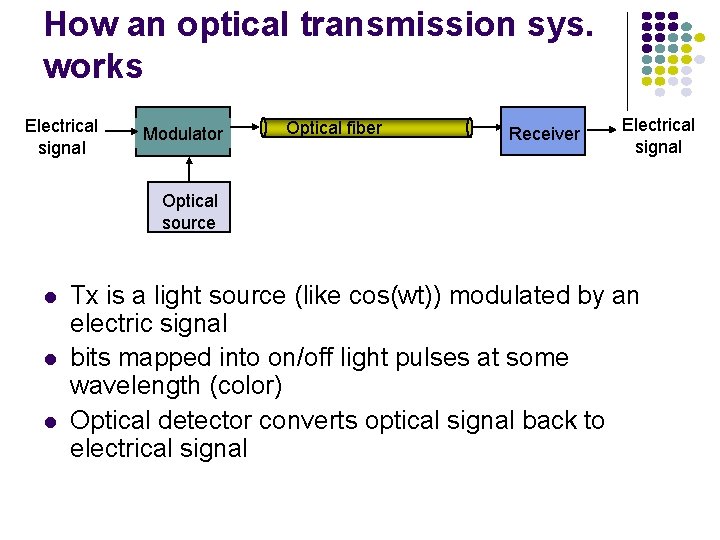

Optical Fiber Electrical signal Modulator Optical fiber Receiver Electrical signal Optical source Light sources (lasers, LEDs) generate pulses of light that are transmitted on optical fiber Very long distances (>1000 km) Very high speeds (>40 Gbps/wavelength) Nearly error-free (BER of 10 -15) Profound influence on network architecture Dominates long distance transmission Distance less of a cost factor in communications Plentiful bandwidth for new services

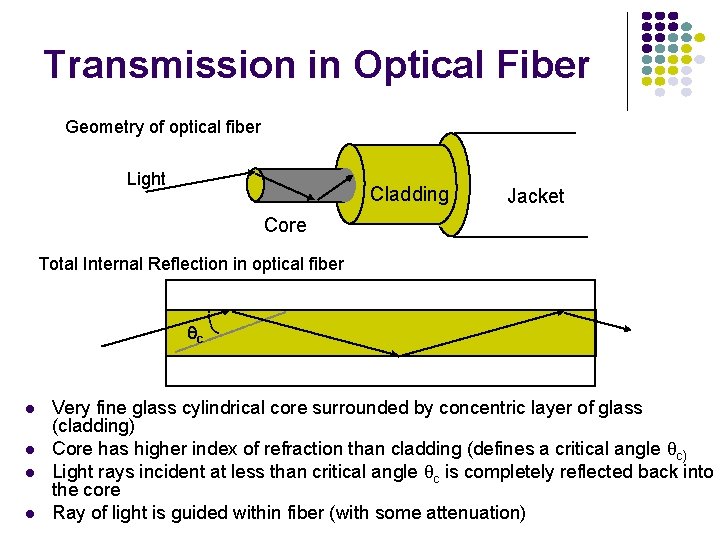

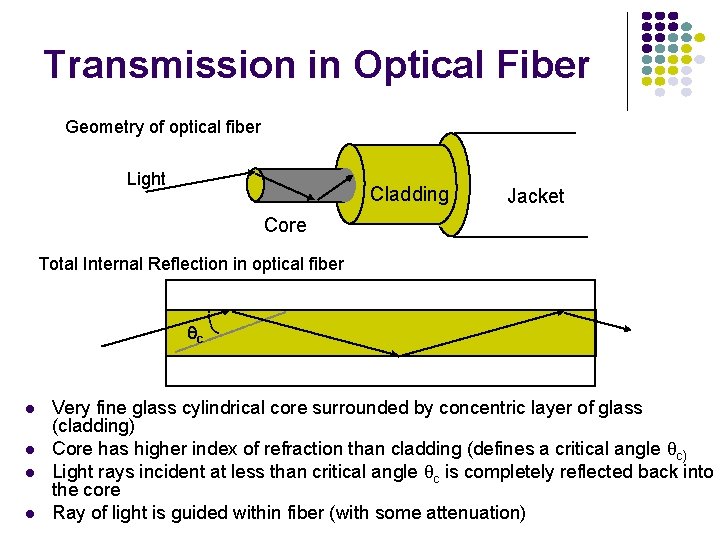

Transmission in Optical Fiber Geometry of optical fiber Light Cladding Jacket Core Total Internal Reflection in optical fiber c Very fine glass cylindrical core surrounded by concentric layer of glass (cladding) Core has higher index of refraction than cladding (defines a critical angle qc) Light rays incident at less than critical angle qc is completely reflected back into the core Ray of light is guided within fiber (with some attenuation)

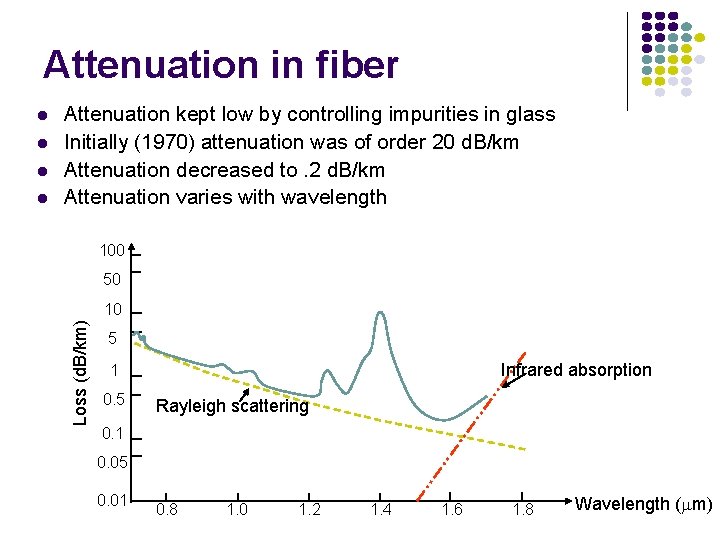

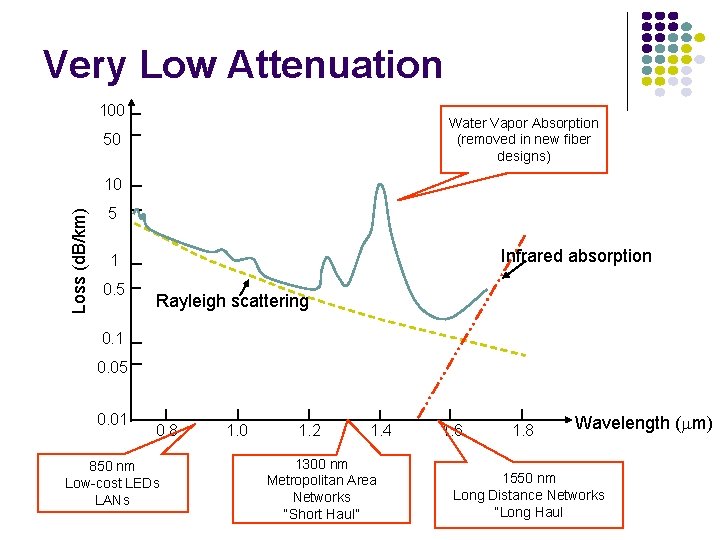

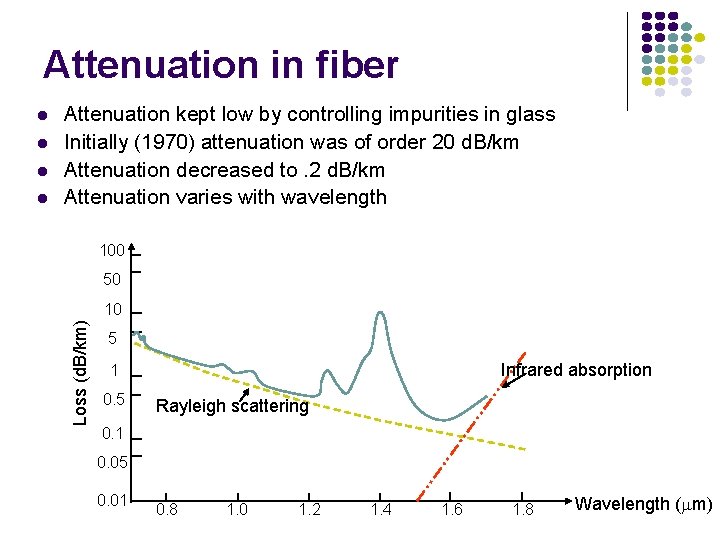

Attenuation in fiber Attenuation kept low by controlling impurities in glass Initially (1970) attenuation was of order 20 d. B/km Attenuation decreased to. 2 d. B/km Attenuation varies with wavelength 100 50 10 Loss (d. B/km) 5 Infrared absorption 1 0. 5 Rayleigh scattering 0. 1 0. 05 0. 01 0. 8 1. 0 1. 2 1. 4 1. 6 1. 8 Wavelength ( m)

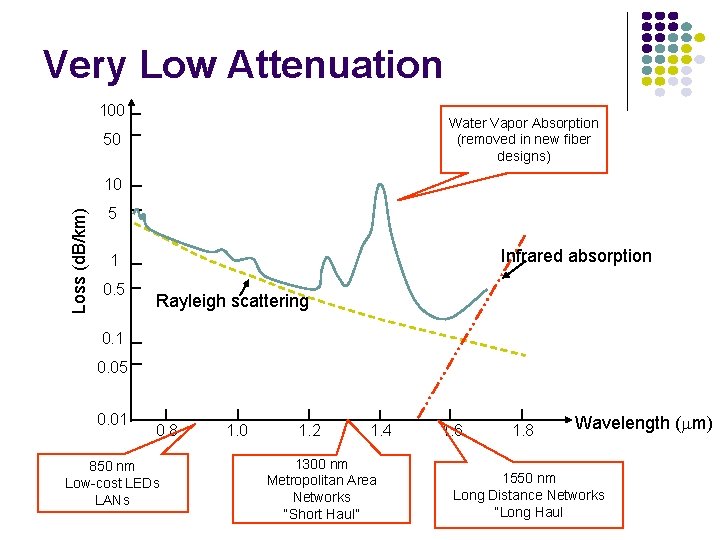

Very Low Attenuation 100 Water Vapor Absorption (removed in new fiber designs) 50 Loss (d. B/km) 10 5 Infrared absorption 1 0. 5 Rayleigh scattering 0. 1 0. 05 0. 01 0. 8 850 nm Low-cost LEDs LANs 1. 0 1. 2 1. 4 1300 nm Metropolitan Area Networks “Short Haul” 1. 6 1. 8 Wavelength ( m) 1550 nm Long Distance Networks “Long Haul

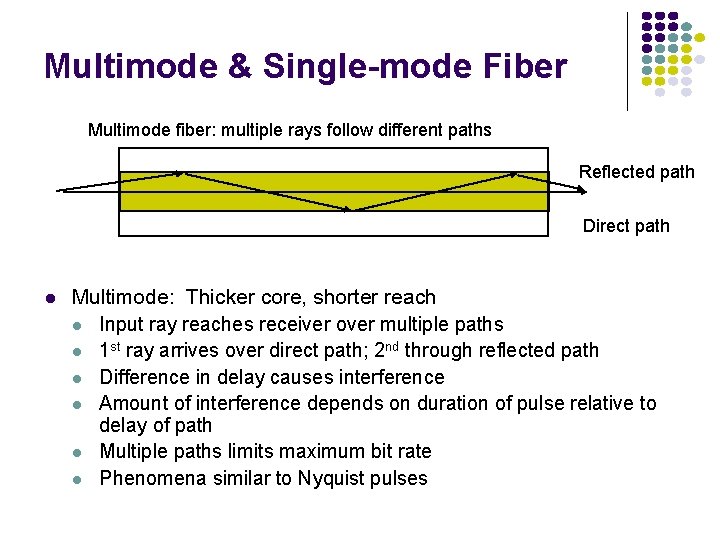

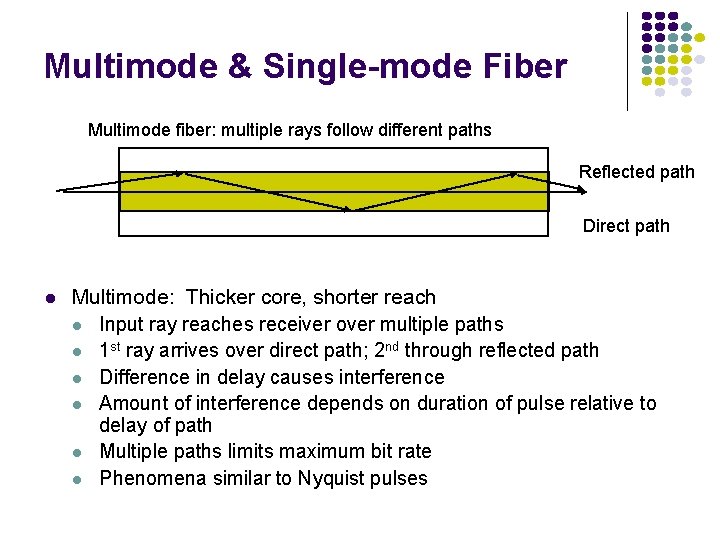

Multimode & Single-mode Fiber Multimode fiber: multiple rays follow different paths Reflected path Direct path Multimode: Thicker core, shorter reach Input ray reaches receiver over multiple paths 1 st ray arrives over direct path; 2 nd through reflected path Difference in delay causes interference Amount of interference depends on duration of pulse relative to delay of path Multiple paths limits maximum bit rate Phenomena similar to Nyquist pulses

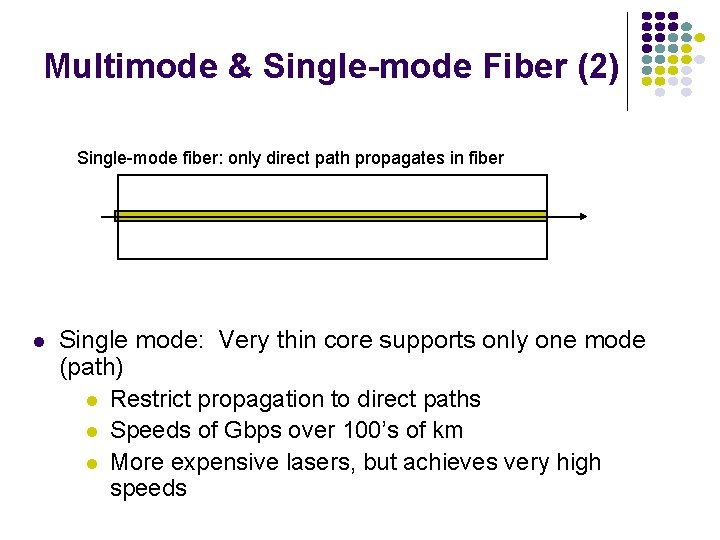

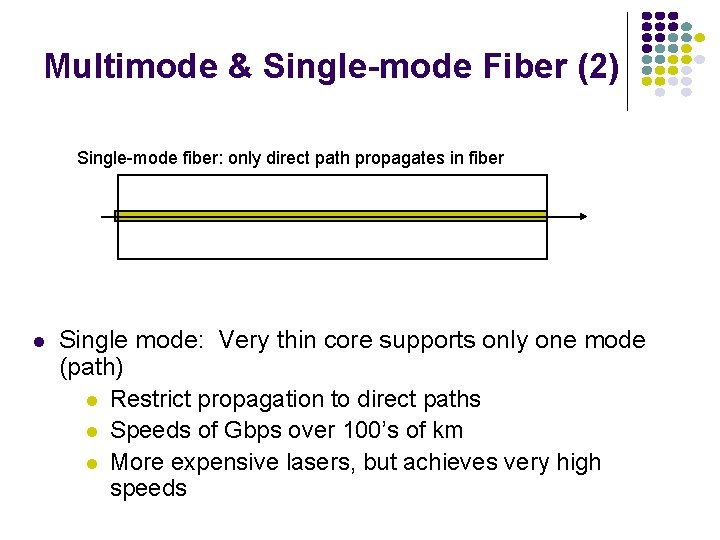

Multimode & Single-mode Fiber (2) Single-mode fiber: only direct path propagates in fiber Single mode: Very thin core supports only one mode (path) Restrict propagation to direct paths Speeds of Gbps over 100’s of km More expensive lasers, but achieves very high speeds

How an optical transmission sys. works Electrical signal Modulator Optical fiber Receiver Electrical signal Optical source Tx is a light source (like cos(wt)) modulated by an electric signal bits mapped into on/off light pulses at some wavelength (color) Optical detector converts optical signal back to electrical signal

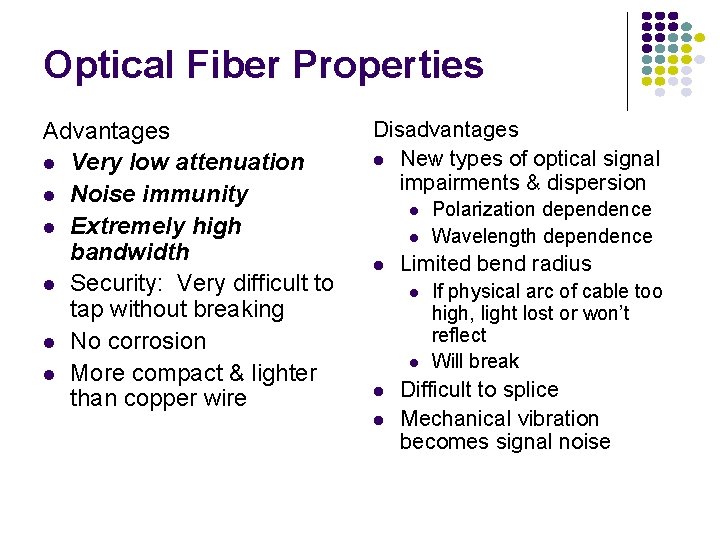

Optical Fiber Properties Advantages Very low attenuation Noise immunity Extremely high bandwidth Security: Very difficult to tap without breaking No corrosion More compact & lighter than copper wire Disadvantages New types of optical signal impairments & dispersion Limited bend radius Polarization dependence Wavelength dependence If physical arc of cable too high, light lost or won’t reflect Will break Difficult to splice Mechanical vibration becomes signal noise

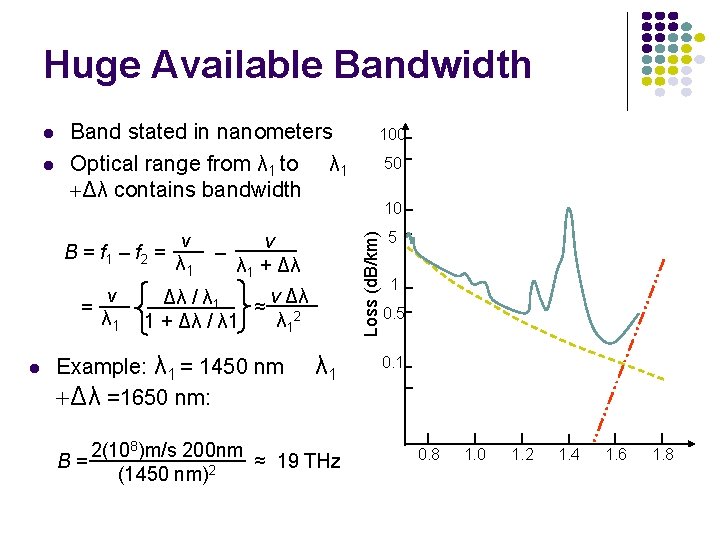

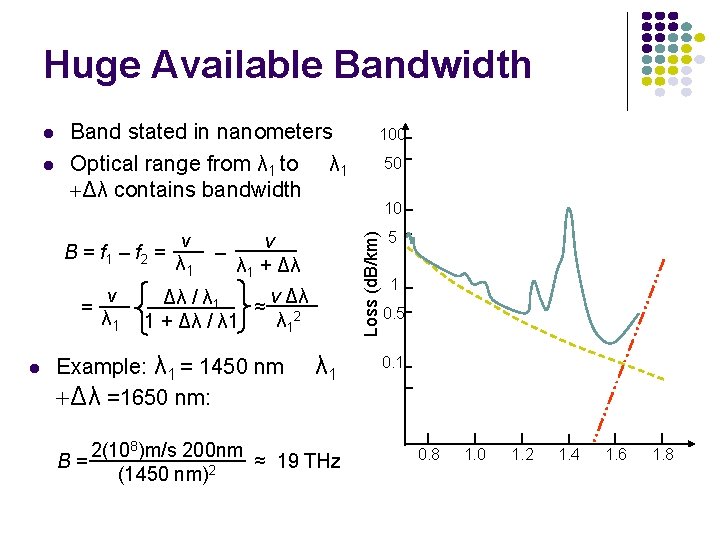

Huge Available Bandwidth Band stated in nanometers Optical range from λ 1 to λ 1 +Δλ contains bandwidth B = f 1 – f 2 = = v λ 1 v – λ 1 + Δλ v Δλ Δλ / λ 1 ≈ 2 λ 1 1 + Δλ / λ 1 Example: λ 1 = 1450 nm +Δλ =1650 nm: 100 50 10 Loss (d. B/km) λ 1 2(108)m/s 200 nm B= ≈ 19 THz (1450 nm)2 5 1 0. 5 0. 1 0. 8 1. 0 1. 2 1. 4 1. 6 1. 8

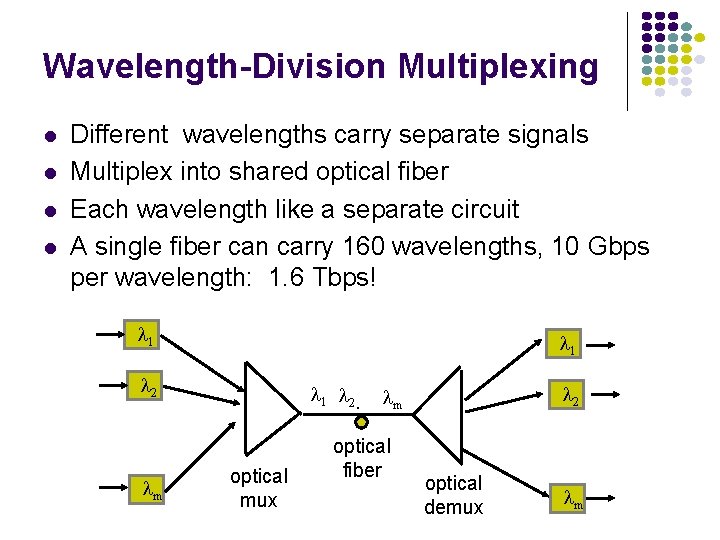

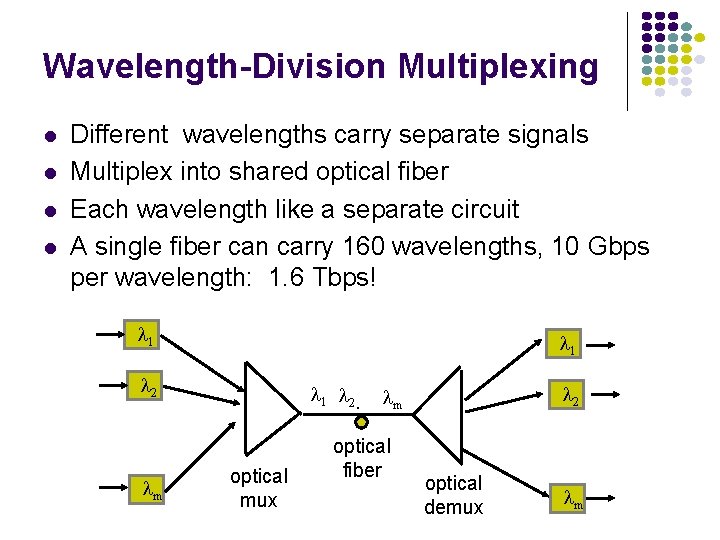

Wavelength-Division Multiplexing Different wavelengths carry separate signals Multiplex into shared optical fiber Each wavelength like a separate circuit A single fiber can carry 160 wavelengths, 10 Gbps per wavelength: 1. 6 Tbps! 1 1 2 m 1 2. optical mux 2 m optical fiber optical demux m

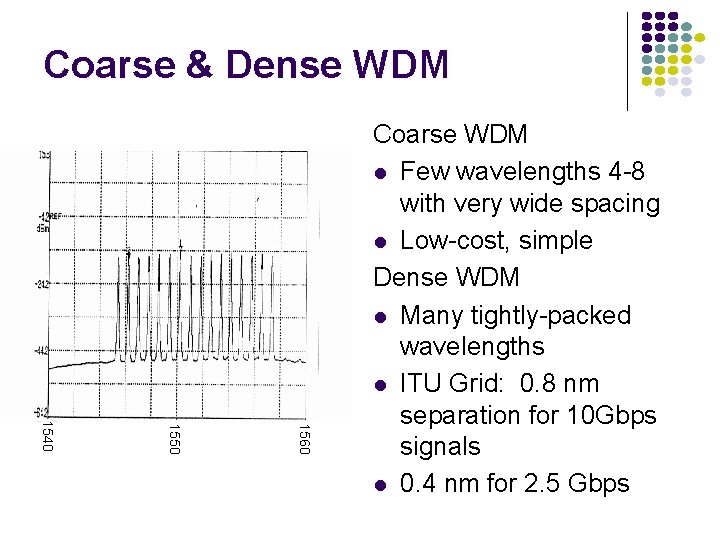

Coarse & Dense WDM 1560 1550 1540 Coarse WDM Few wavelengths 4 -8 with very wide spacing Low-cost, simple Dense WDM Many tightly-packed wavelengths ITU Grid: 0. 8 nm separation for 10 Gbps signals 0. 4 nm for 2. 5 Gbps

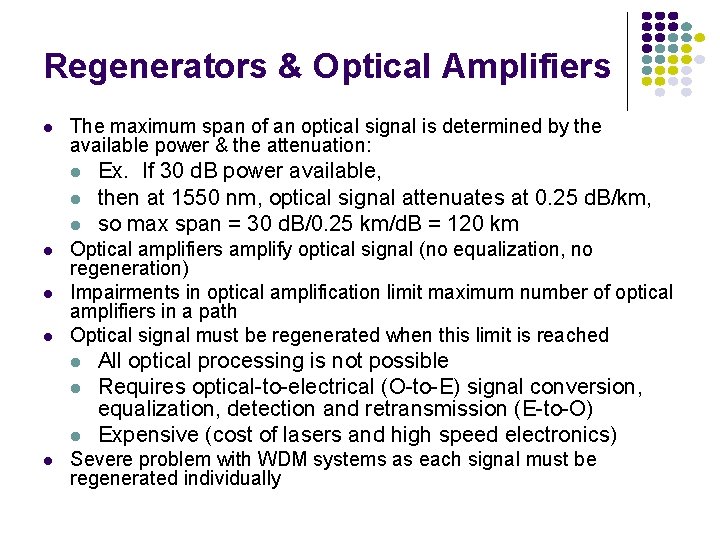

Regenerators & Optical Amplifiers The maximum span of an optical signal is determined by the available power & the attenuation: Optical amplifiers amplify optical signal (no equalization, no regeneration) Impairments in optical amplification limit maximum number of optical amplifiers in a path Optical signal must be regenerated when this limit is reached Ex. If 30 d. B power available, then at 1550 nm, optical signal attenuates at 0. 25 d. B/km, so max span = 30 d. B/0. 25 km/d. B = 120 km All optical processing is not possible Requires optical-to-electrical (O-to-E) signal conversion, equalization, detection and retransmission (E-to-O) Expensive (cost of lasers and high speed electronics) Severe problem with WDM systems as each signal must be regenerated individually

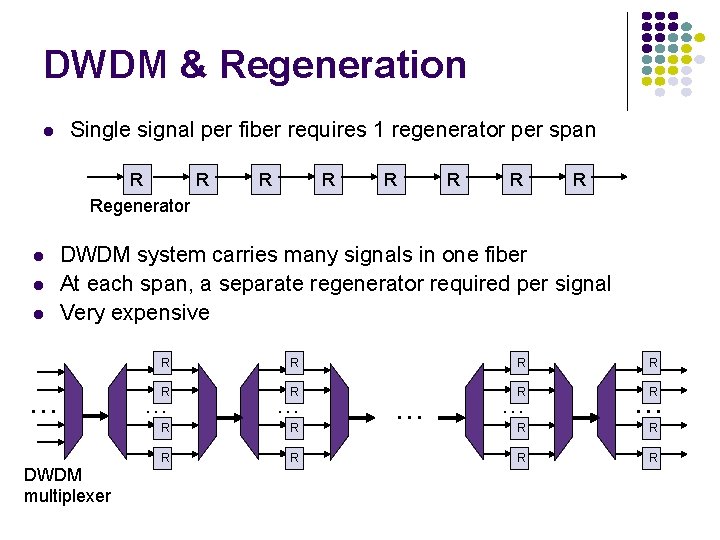

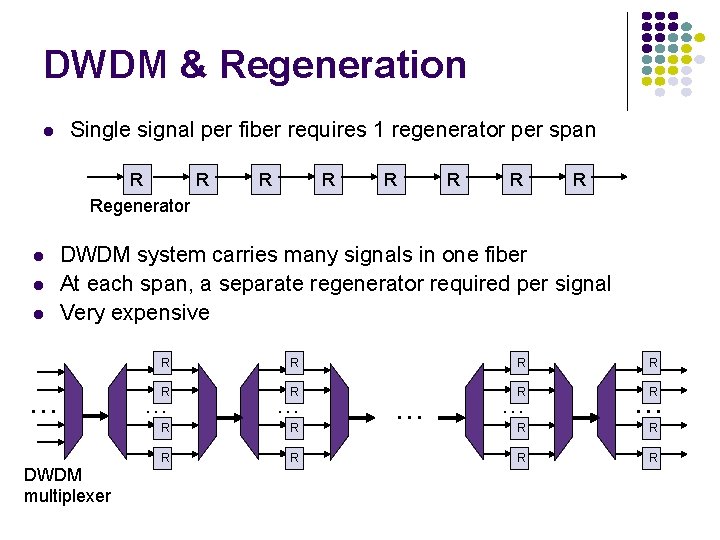

DWDM & Regeneration Single signal per fiber requires 1 regenerator per span R R Regenerator R R R DWDM system carries many signals in one fiber At each span, a separate regenerator required per signal Very expensive … DWDM multiplexer R R R … … R R R

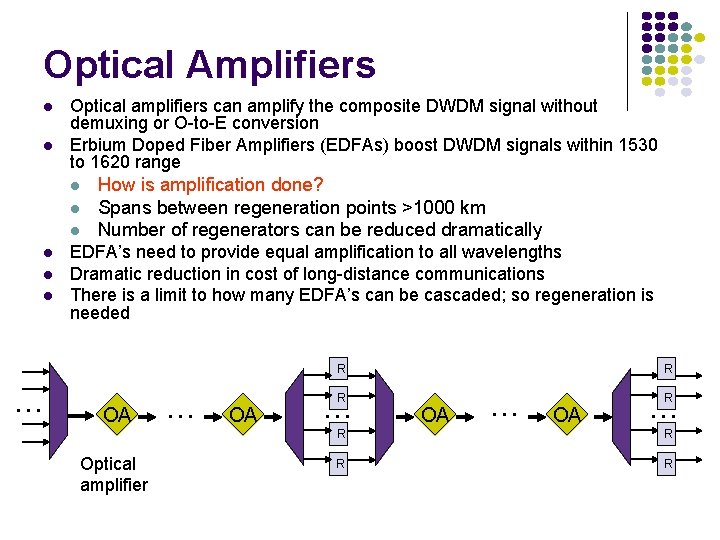

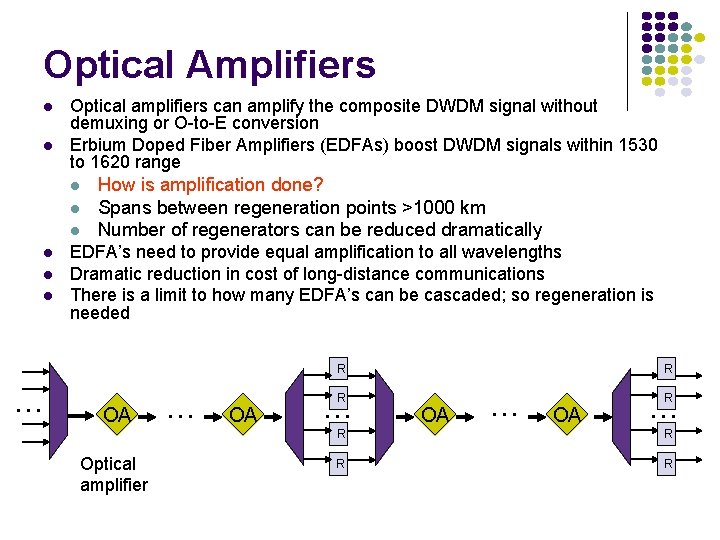

Optical Amplifiers Optical amplifiers can amplify the composite DWDM signal without demuxing or O-to-E conversion Erbium Doped Fiber Amplifiers (EDFAs) boost DWDM signals within 1530 to 1620 range How is amplification done? Spans between regeneration points >1000 km Number of regenerators can be reduced dramatically EDFA’s need to provide equal amplification to all wavelengths Dramatic reduction in cost of long-distance communications There is a limit to how many EDFA’s can be cascaded; so regeneration is needed R R … OA Optical amplifier … OA … R R R

Applications Should fibers use in the backbone network? Is it cost effective? How about installing fiber in subscriber portion of network (Fiber to home)? Is it cost effective? Anything in between (Fiber to curb)?

Applications (Gigabit Ethernet) Would you use a multimode or single mode fiber for Wide Area Network? Which of the two optical transmission syetems 850 nm and 1310 nm would create a larger local area network?

Radio Transmission Radio: communication in the electromagnetic spectrum of 3 k. Hz to 300 Ghz Radio signals: antenna transmits sinusoidal signal (“carrier”) that radiates in air/space Information embedded in carrier signal using modulation, e. g. QAM Two types of propagation depending on antenna and frequency Unidirectional: properly aligned antenna receives signal Omni directional: any antenna in area of coverage receives signal Communications without tethering Cellular phones, satellite transmissions, Wireless LANs

Propagation Impairments Attenuation varies logarithmically with distance d. B = n log d Attenuation increases with rain fall Multipath propagation causes fading: Interference when two or more versions of same signal arrive at slightly different times If signals arrive with same polarity, they will add If signals arrive with different polarity, they will cancel each other This creates fading in signal level Interference from other users in same or adjacent bands Spectrum regulated by national & international regulatory organizations

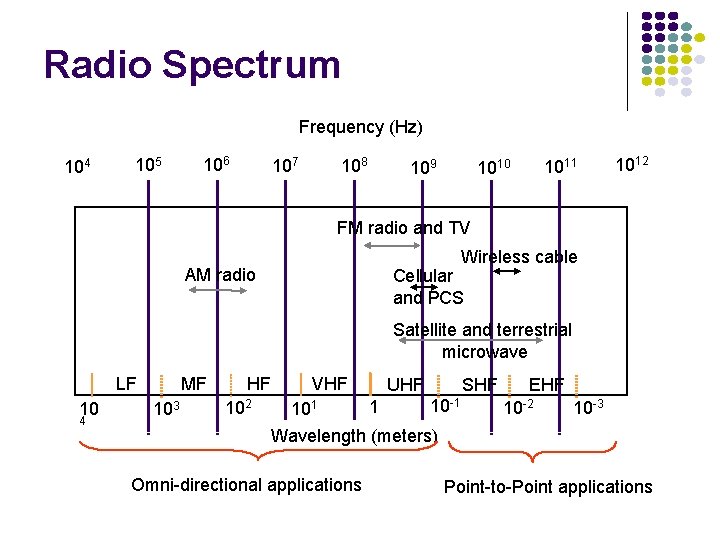

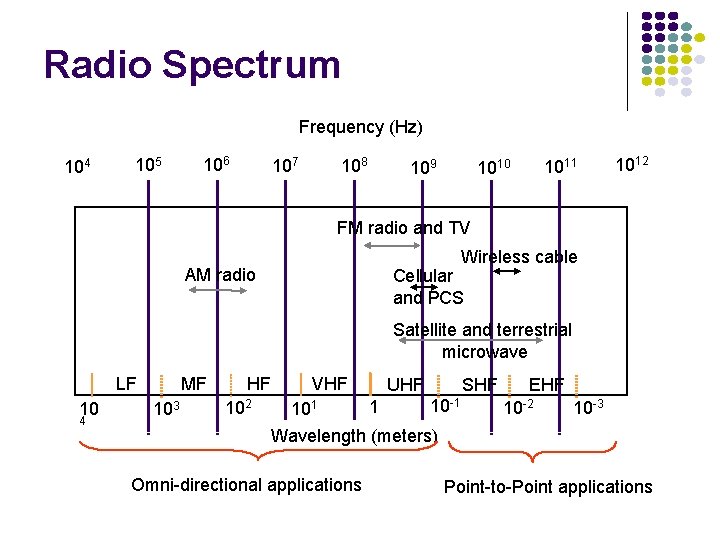

Radio Spectrum Frequency (Hz) 104 105 106 108 107 109 1011 1010 1012 FM radio and TV Wireless cable AM radio Cellular and PCS Satellite and terrestrial microwave LF 10 4 MF 103 HF 102 VHF 101 UHF 1 SHF 10 -1 EHF 10 -2 10 -3 Wavelength (meters) Omni-directional applications Point-to-Point applications

Propagation properties varies with distance How are the properties of VLF, MF, and HF different? Mention some applications. Why type of propagation (omni- or unidirectional) would you use for paging? For cordless phones?

Examples Cellular Phone Allocated spectrum First generation: 800, 900 MHz Initially analog voice Second generation: 1800 -1900 MHz Digital voice, messaging Wireless LAN Unlicenced ISM spectrum Industrial, Scientific, Medical 902 -928 MHz, 2. 400 -2. 4835 GHz, 5. 7255. 850 GHz IEEE 802. 11 LAN standard 11 -54 Mbps Point-to-Multipoint Systems Directional antennas at microwave frequencies High-speed digital communications between sites Logarithmic attenuation gives adv over coaxial cable (reduce repeater spacing) High-speed Internet Access Radio backbone links for rural areas Also used for wireless cable Satellite Communications Geostationary satellite @ 36000 km above equator Relays microwave signals from uplink frequency to downlink frequency Long distance telephone Satellite TV broadcast

Chapter 3 Digital Transmission Fundamentals Error Detection and Correction

Error Control Digital transmission systems introduce errors Applications require certain reliability level Data applications require error-free transfer Voice & video applications tolerate some errors Error control used when transmission system does not meet application requirement Error control ensures a data stream is transmitted to a certain level of accuracy despite errors Two basic approaches: Error detection & retransmission (ARQ) Forward error correction (FEC)

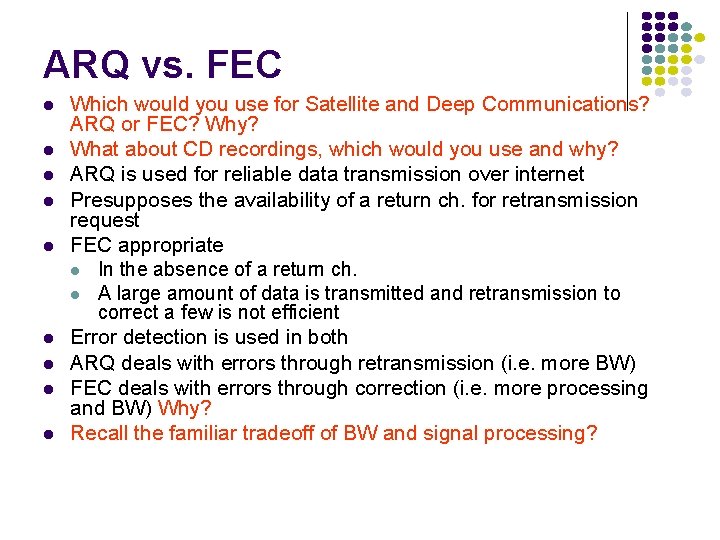

ARQ vs. FEC Which would you use for Satellite and Deep Communications? ARQ or FEC? Why? What about CD recordings, which would you use and why? ARQ is used for reliable data transmission over internet Presupposes the availability of a return ch. for retransmission request FEC appropriate In the absence of a return ch. A large amount of data is transmitted and retransmission to correct a few is not efficient Error detection is used in both ARQ deals with errors through retransmission (i. e. more BW) FEC deals with errors through correction (i. e. more processing and BW) Why? Recall the familiar tradeoff of BW and signal processing?

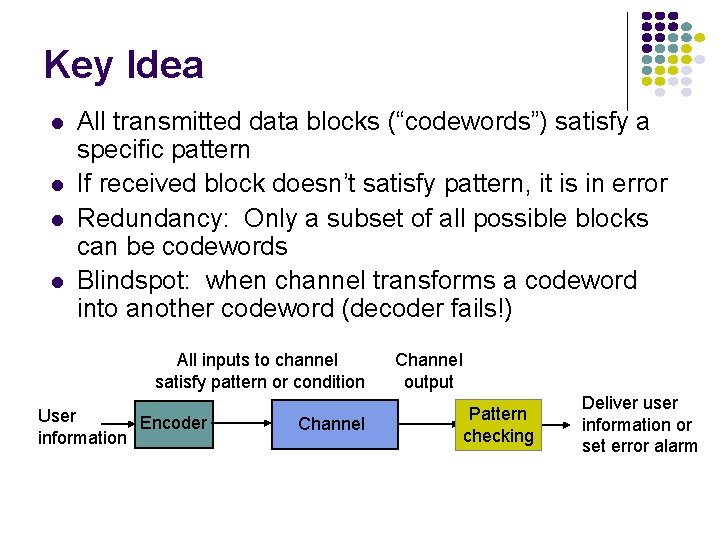

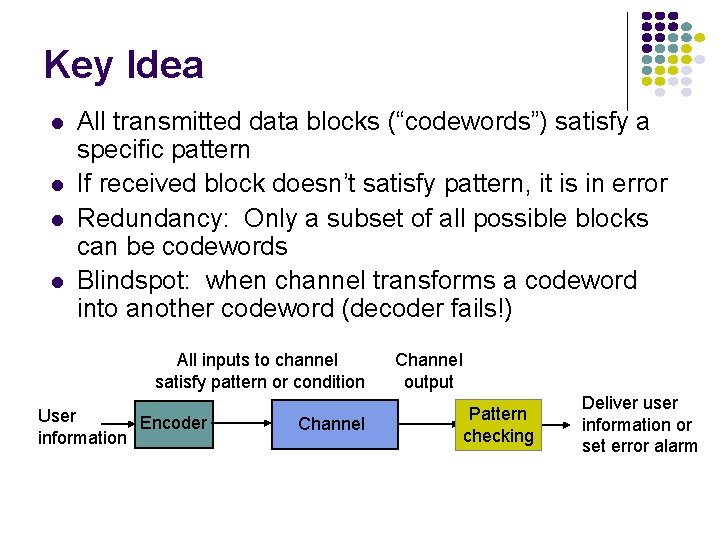

Key Idea All transmitted data blocks (“codewords”) satisfy a specific pattern If received block doesn’t satisfy pattern, it is in error Redundancy: Only a subset of all possible blocks can be codewords Blindspot: when channel transforms a codeword into another codeword (decoder fails!) All inputs to channel satisfy pattern or condition User Encoder information Channel output Pattern checking Deliver user information or set error alarm

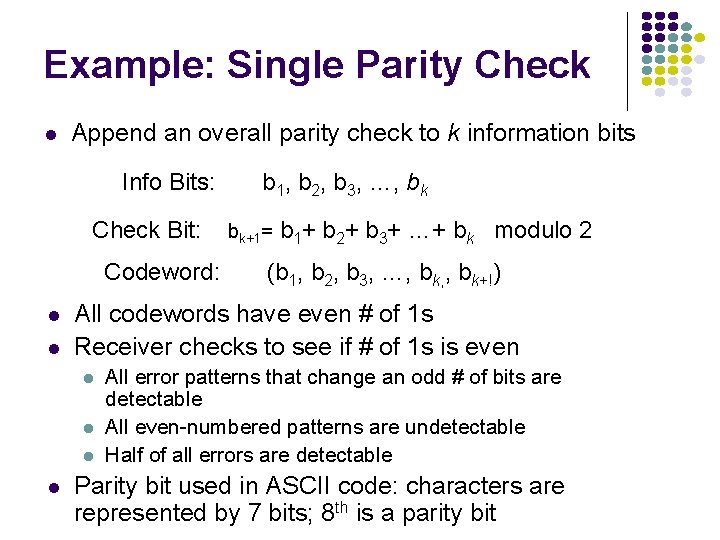

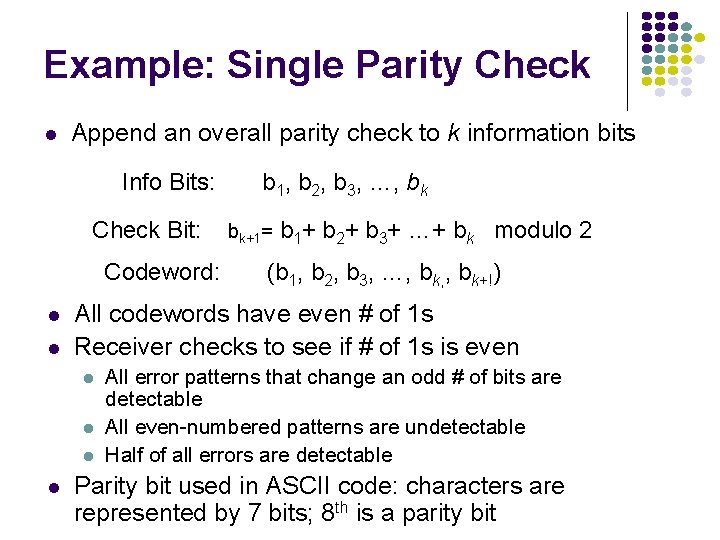

Example: Single Parity Check Append an overall parity check to k information bits Info Bits: Check Bit: Codeword: bk+1= b 1+ b 2+ b 3+ …+ bk modulo 2 (b 1, b 2, b 3, …, bk, , bk+!) All codewords have even # of 1 s Receiver checks to see if # of 1 s is even b 1, b 2, b 3, …, bk All error patterns that change an odd # of bits are detectable All even-numbered patterns are undetectable Half of all errors are detectable Parity bit used in ASCII code: characters are represented by 7 bits; 8 th is a parity bit

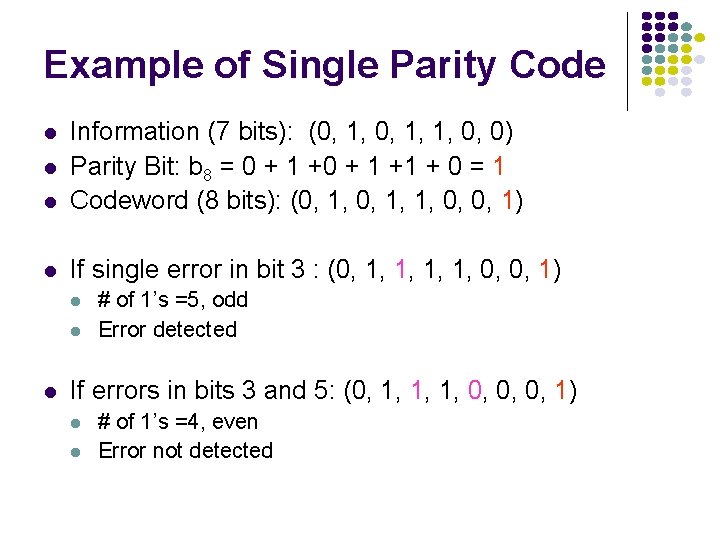

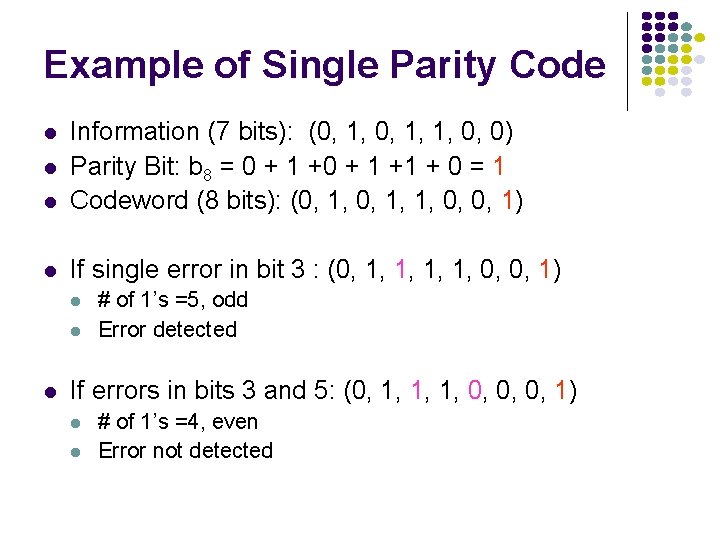

Example of Single Parity Code Information (7 bits): (0, 1, 1, 0, 0) Parity Bit: b 8 = 0 + 1 +1 + 0 = 1 Codeword (8 bits): (0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1) If single error in bit 3 : (0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1) # of 1’s =5, odd Error detected If errors in bits 3 and 5: (0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1) # of 1’s =4, even Error not detected

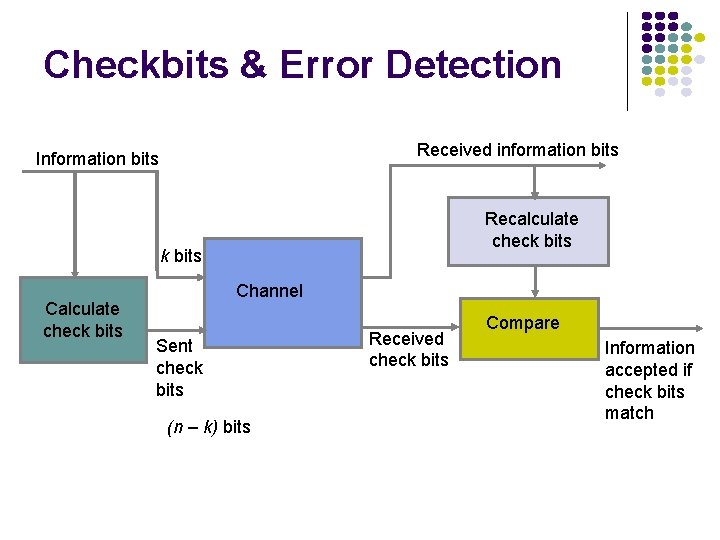

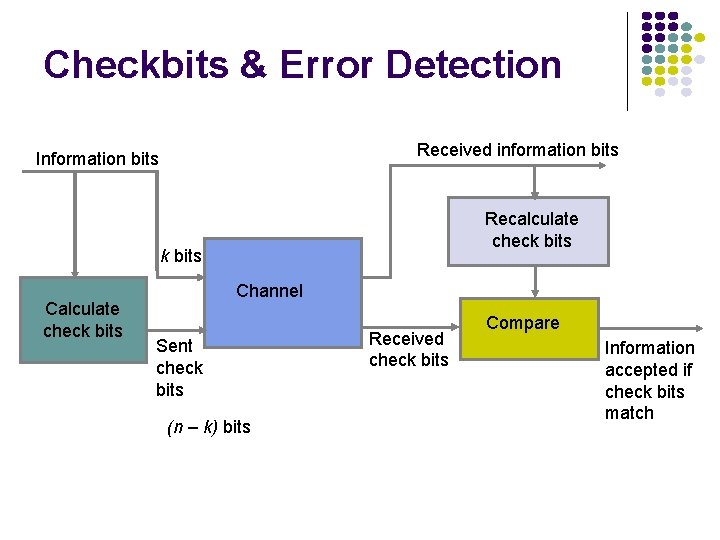

Checkbits & Error Detection Received information bits Information bits Recalculate check bits Calculate check bits Channel Sent check bits (n – k) bits Received check bits Compare Information accepted if check bits match

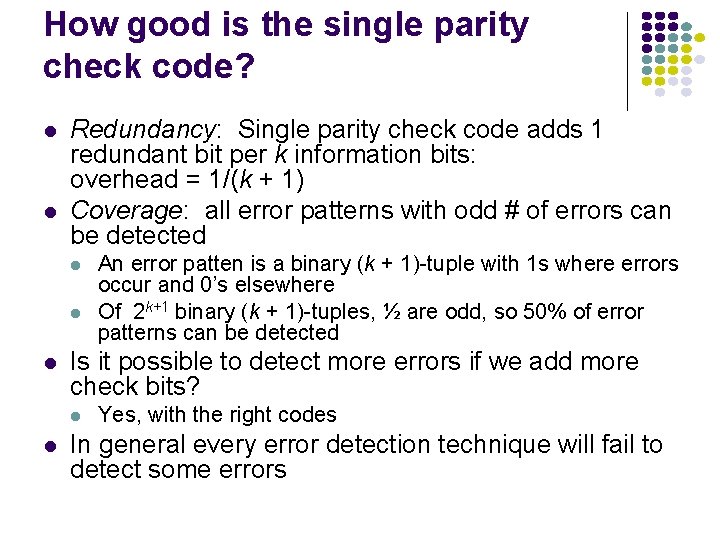

How good is the single parity check code? Redundancy: Single parity check code adds 1 redundant bit per k information bits: overhead = 1/(k + 1) Coverage: all error patterns with odd # of errors can be detected Is it possible to detect more errors if we add more check bits? An error patten is a binary (k + 1)-tuple with 1 s where errors occur and 0’s elsewhere Of 2 k+1 binary (k + 1)-tuples, ½ are odd, so 50% of error patterns can be detected Yes, with the right codes In general every error detection technique will fail to detect some errors

3 types of error modles Random error vector model: Transmit a codeword of length n all 2^n error vectors are equally likely to occur Error vec. (1, 0, …, 0) has same probability as (1, 1, …, 1) What is the prob of error detection failure of single parity check code? Random bit error model

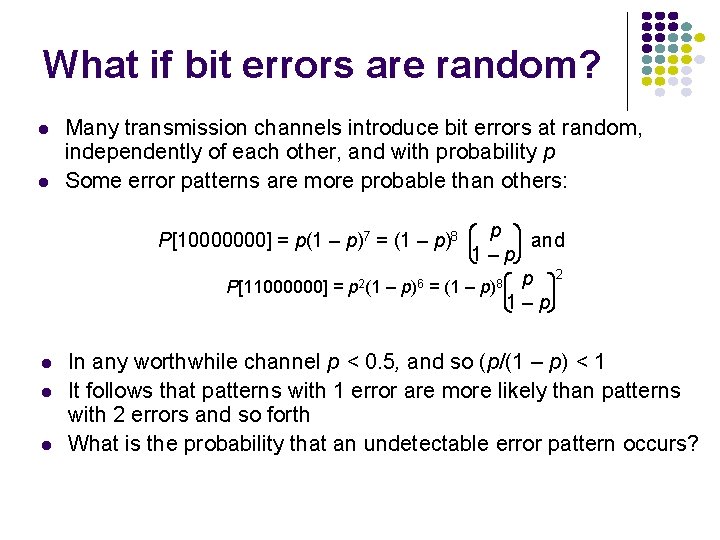

What if bit errors are random? Many transmission channels introduce bit errors at random, independently of each other, and with probability p Some error patterns are more probable than others: p and 1–p 2 6 8 P[11000000] = p (1 – p) = (1 – p) 1–p P[10000000] = p(1 – p)7 = (1 – p)8 In any worthwhile channel p < 0. 5, and so (p/(1 – p) < 1 It follows that patterns with 1 error are more likely than patterns with 2 errors and so forth What is the probability that an undetectable error pattern occurs?

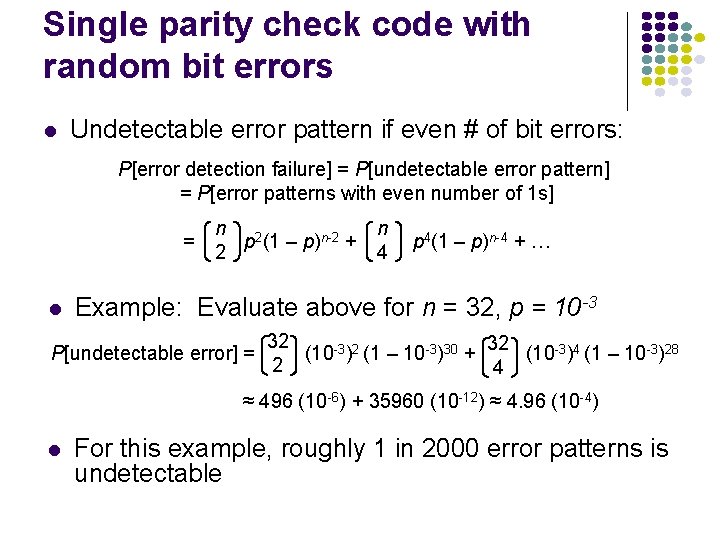

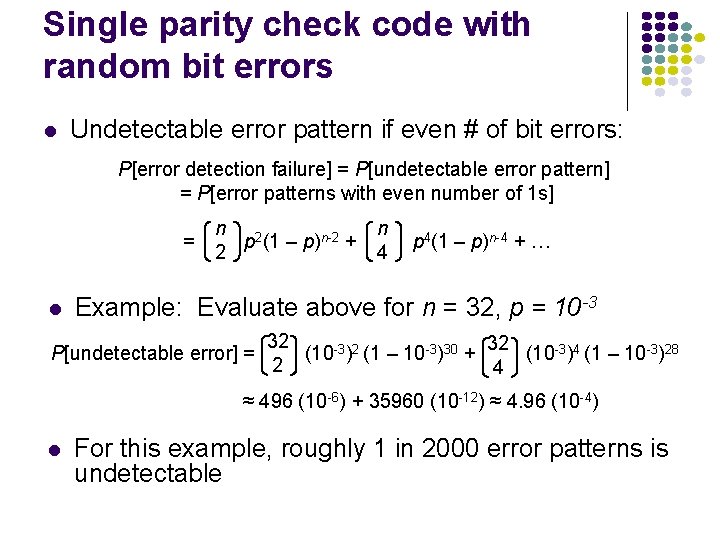

Single parity check code with random bit errors Undetectable error pattern if even # of bit errors: P[error detection failure] = P[undetectable error pattern] = P[error patterns with even number of 1 s] = n 2 p (1 – p)n-2 + 2 n 4 p 4(1 – p)n-4 + … Example: Evaluate above for n = 32, p = 10 -3 P[undetectable error] = 32 32 (10 -3)2 (1 – 10 -3)30 + (10 -3)4 (1 – 10 -3)28 2 4 ≈ 496 (10 -6) + 35960 (10 -12) ≈ 4. 96 (10 -4) For this example, roughly 1 in 2000 error patterns is undetectable

Burst of Errors Combination of two errors Periods of low error rate transmission (similar to random bit error) Periods with clusters of errors (similar to random error vecotor model)

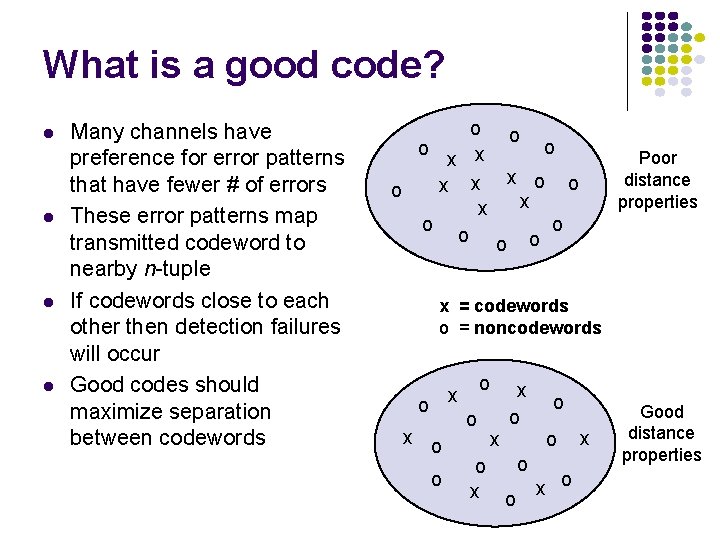

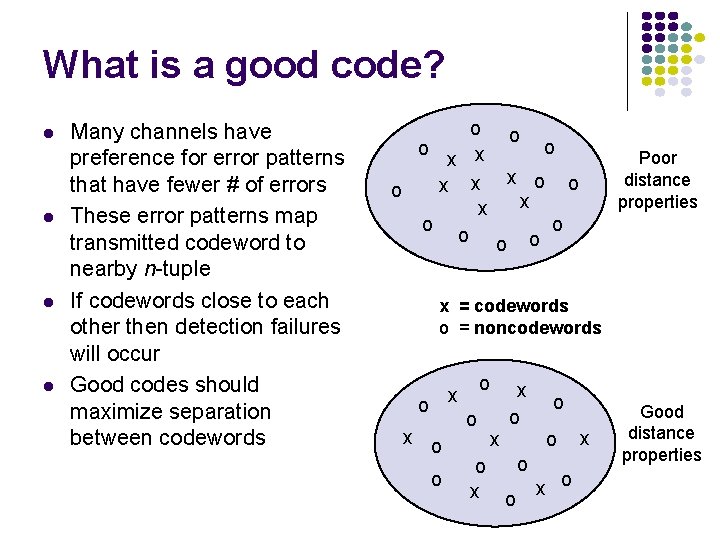

What is a good code? Many channels have preference for error patterns that have fewer # of errors These error patterns map transmitted codeword to nearby n-tuple If codewords close to each other then detection failures will occur Good codes should maximize separation between codewords o o x x x o o o Poor distance properties x = codewords o = noncodewords o x x o o o x x Good distance properties

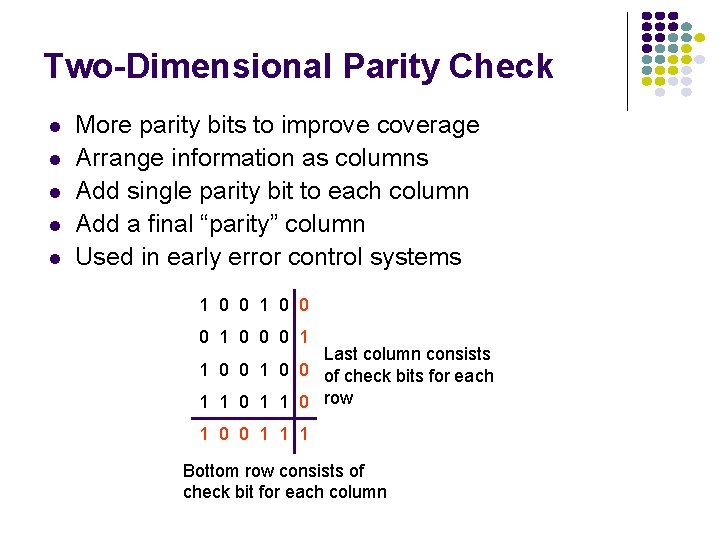

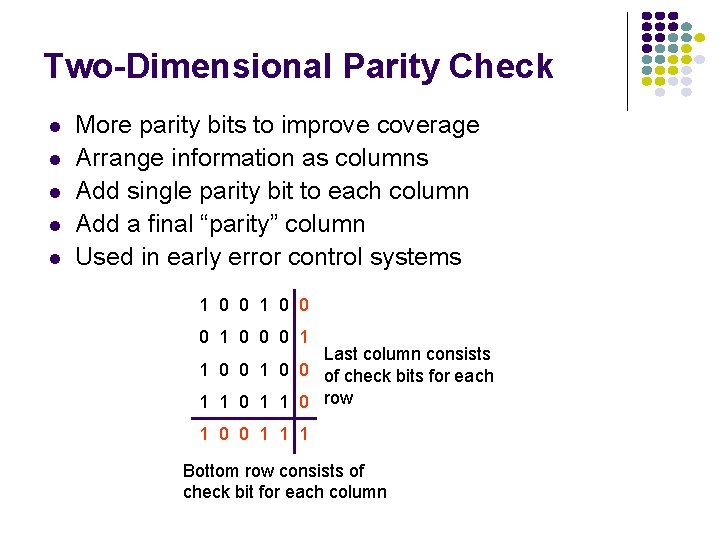

Two-Dimensional Parity Check More parity bits to improve coverage Arrange information as columns Add single parity bit to each column Add a final “parity” column Used in early error control systems 1 0 0 0 1 Last column consists 1 0 0 of check bits for each 1 1 0 row 1 0 0 1 1 1 Bottom row consists of check bit for each column

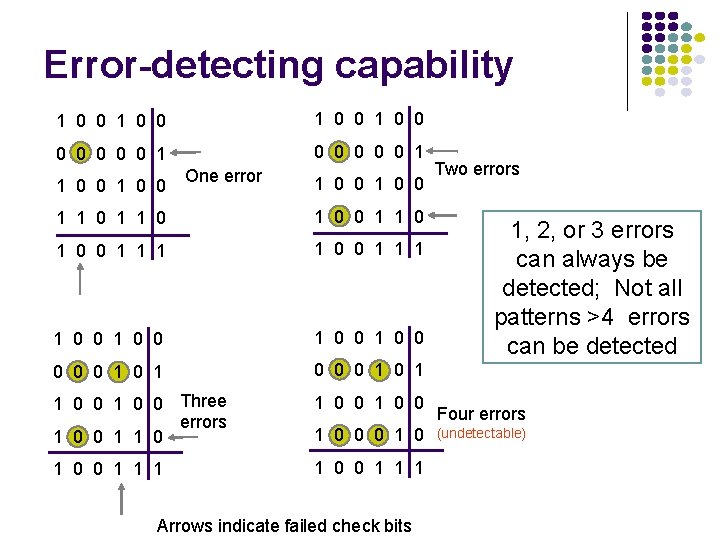

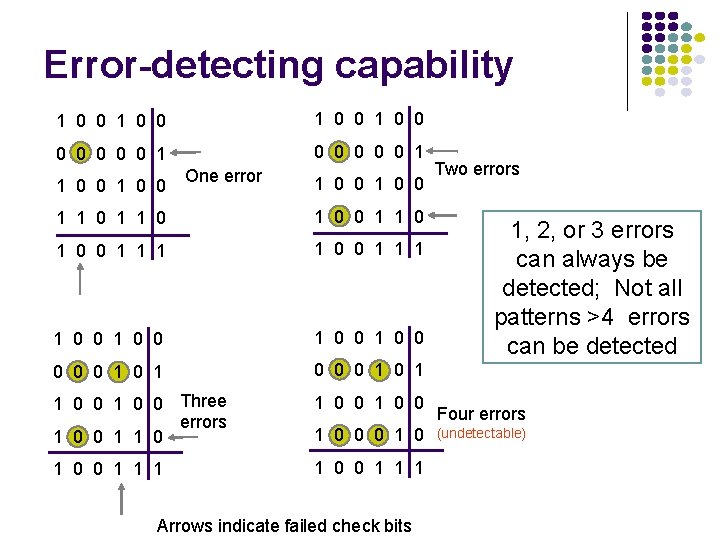

Error-detecting capability 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 One error 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 Three errors 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 Arrows indicate failed check bits Two errors 1, 2, or 3 errors can always be detected; Not all patterns >4 errors can be detected Four errors (undetectable)

Other Error Detection Codes Many applications require very low error rate Need codes that detect the vast majority of errors Single parity check codes do not detect enough errors Two-dimensional codes require too many check bits The following (powerful) error detecting codes are used in practice: Internet Check Sums CRC Polynomial Codes

Internet Checksum Several Internet protocols (e. g. IP, TCP, UDP) use check bits to detect errors in the IP header (or in the header and data for TCP/UDP) A checksum is calculated for header contents and included in a special field. Checksum recalculated at every router, so algorithm selected for ease of implementation in software Let header consist of L, 16 -bit words, b 0, b 1, b 2, . . . , b. L-1 The algorithm appends a 16 -bit checksum b. L

Checksum Calculation The checksum b. L is calculated as follows: Treating each 16 -bit word as an integer, find x = b 0 + b 1 + b 2+. . . + b. L-1 modulo 216 -1 The checksum is then given by: b. L = - x modulo 216 -1 Thus, the headers must satisfy the following pattern: 0 = b 0 + b 1 + b 2+. . . + b. L-1 + b. L modulo 216 -1 The checksum calculation is carried out in software using one’s complement arithmetic

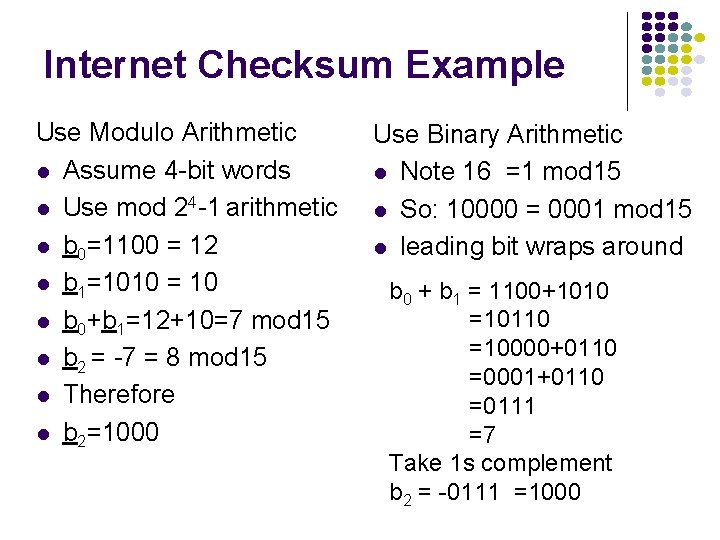

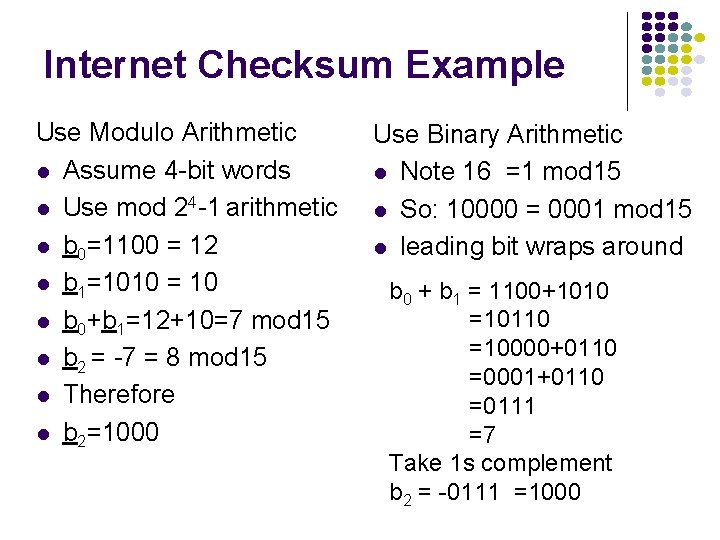

Internet Checksum Example Use Modulo Arithmetic Assume 4 -bit words Use mod 24 -1 arithmetic b 0=1100 = 12 b 1=1010 = 10 b 0+b 1=12+10=7 mod 15 b 2 = -7 = 8 mod 15 Therefore b 2=1000 Use Binary Arithmetic Note 16 =1 mod 15 So: 10000 = 0001 mod 15 leading bit wraps around b 0 + b 1 = 1100+1010 =10110 =10000+0110 =0001+0110 =0111 =7 Take 1 s complement b 2 = -0111 =1000

Polynomial Codes Polynomials instead of vectors for codewords Polynomial arithmetic instead of check sums Implemented using shift-register circuits Also called cyclic redundancy check (CRC) codes Most data communications standards use polynomial codes for error detection Polynomial codes also basis for powerful error-correction methods

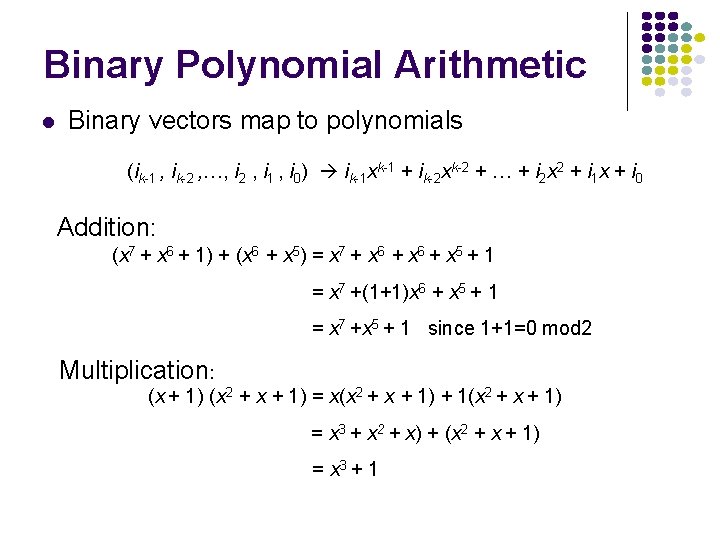

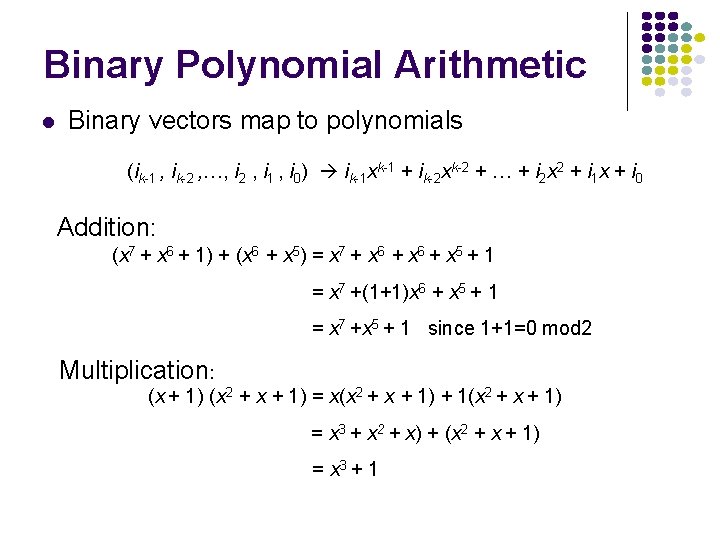

Binary Polynomial Arithmetic Binary vectors map to polynomials (ik-1 , ik-2 , …, i 2 , i 1 , i 0) ik-1 xk-1 + ik-2 xk-2 + … + i 2 x 2 + i 1 x + i 0 Addition: (x 7 + x 6 + 1) + (x 6 + x 5) = x 7 + x 6 + x 5 + 1 = x 7 +(1+1)x 6 + x 5 + 1 = x 7 +x 5 + 1 since 1+1=0 mod 2 Multiplication: (x + 1) (x 2 + x + 1) = x(x 2 + x + 1) + 1(x 2 + x + 1) = x 3 + x 2 + x) + (x 2 + x + 1) = x 3 + 1

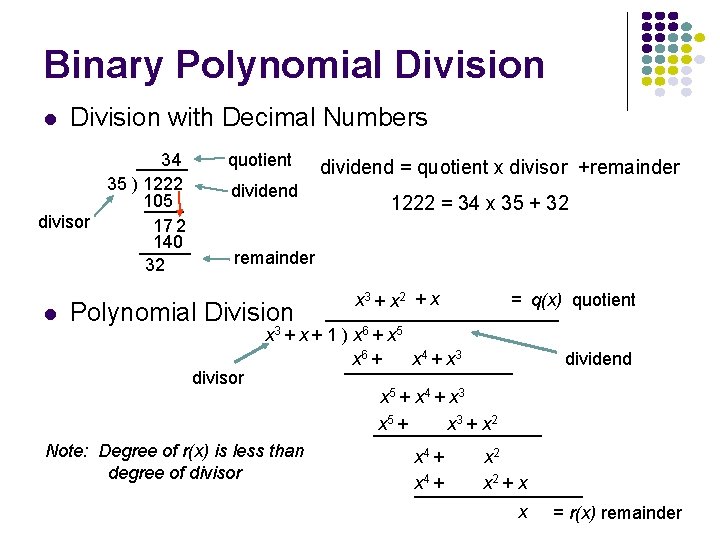

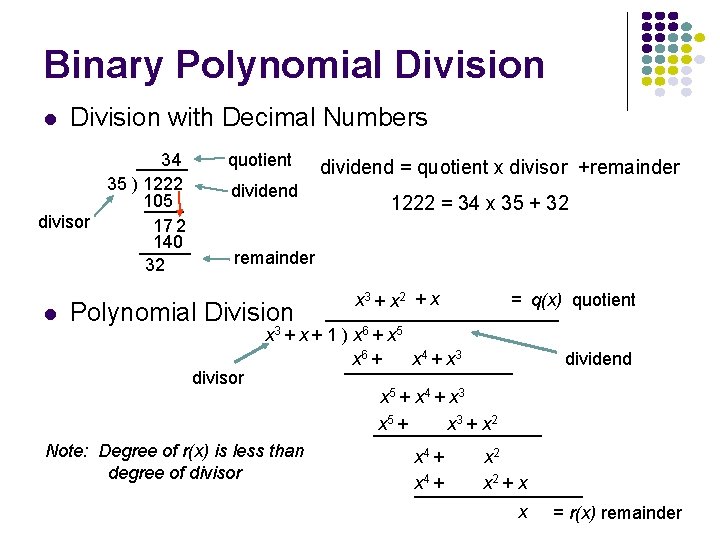

Binary Polynomial Division with Decimal Numbers 34 35 ) 1222 105 divisor 17 2 140 32 quotient dividend = quotient x divisor +remainder 1222 = 34 x 35 + 32 remainder Polynomial Division divisor x 3 + x 2 + x = q(x) quotient x 3 + x + 1 ) x 6 + x 5 x 6 + x 4 + x 3 Note: Degree of r(x) is less than degree of divisor dividend x 5 + x 4 + x 3 x 5 + x 3 + x 2 x 4 + x 2 + x x = r(x) remainder

Polynomial Coding An (n, k) code Codewords have n bits k information bits n-k check bits

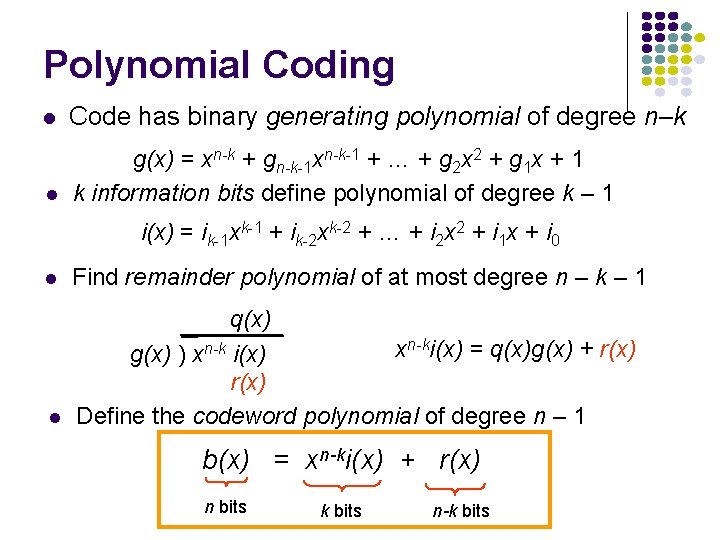

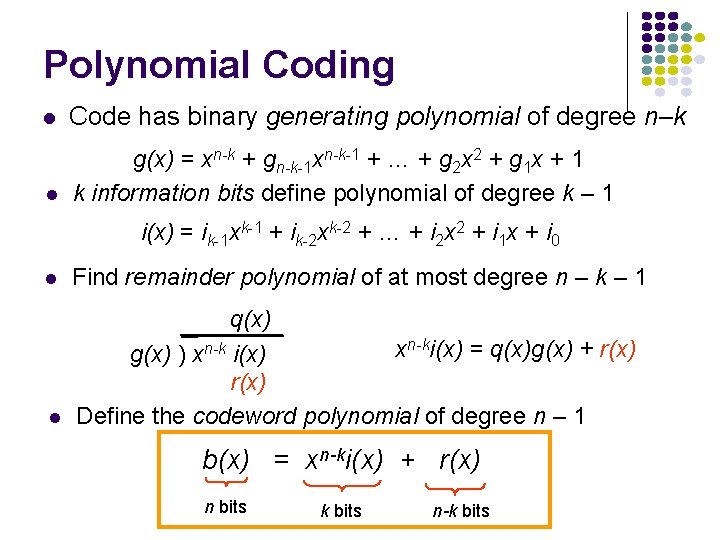

Polynomial Coding Code has binary generating polynomial of degree n–k g(x) = xn-k + gn-k-1 xn-k-1 + … + g 2 x 2 + g 1 x + 1 k information bits define polynomial of degree k – 1 i(x) = ik-1 xk-1 + ik-2 xk-2 + … + i 2 x 2 + i 1 x + i 0 Find remainder polynomial of at most degree n – k – 1 q(x) xn-ki(x) = q(x)g(x) + r(x) g(x) ) xn-k i(x) r(x) Define the codeword polynomial of degree n – 1 b(x) = xn-ki(x) + r(x) n bits k bits n-k bits

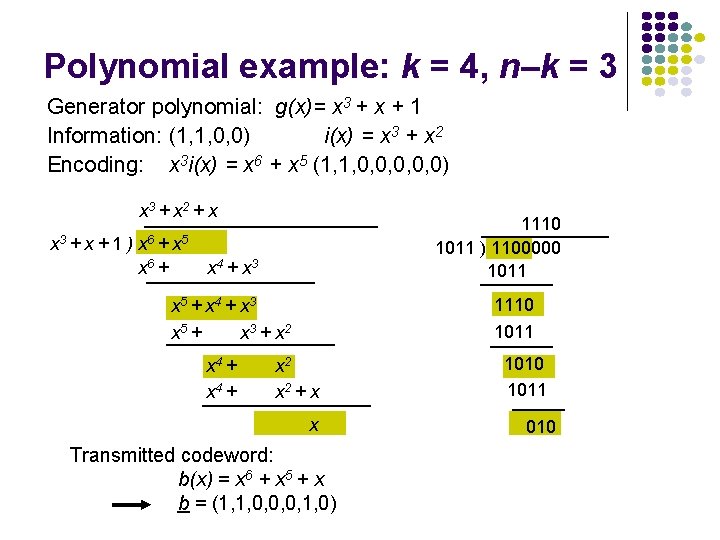

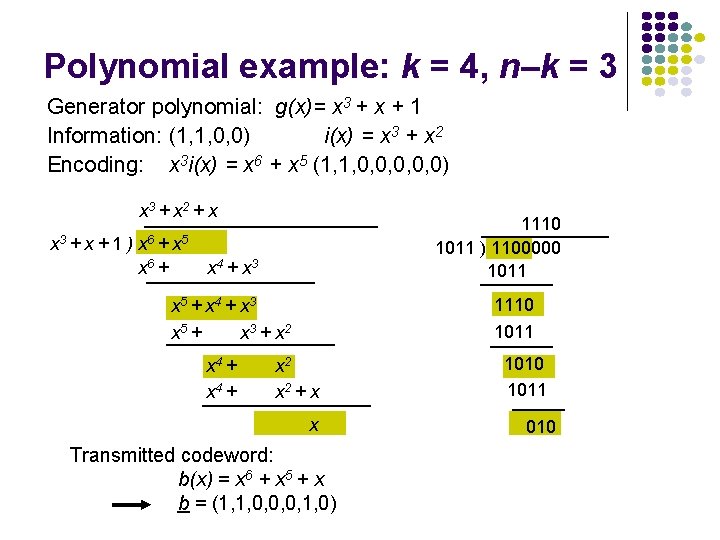

Polynomial example: k = 4, n–k = 3 Generator polynomial: g(x)= x 3 + x + 1 Information: (1, 1, 0, 0) i(x) = x 3 + x 2 Encoding: x 3 i(x) = x 6 + x 5 (1, 1, 0, 0, 0) x 3 + x 2 + x x 3 + x + 1 ) x 6 + x 5 x 6 + 1110 1011 ) 1100000 1011 x 4 + x 3 1110 1011 x 5 + x 4 + x 3 x 5 + x 3 + x 2 x 4 + x 2 + x x Transmitted codeword: b(x) = x 6 + x 5 + x b = (1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0) 1010 1011 010

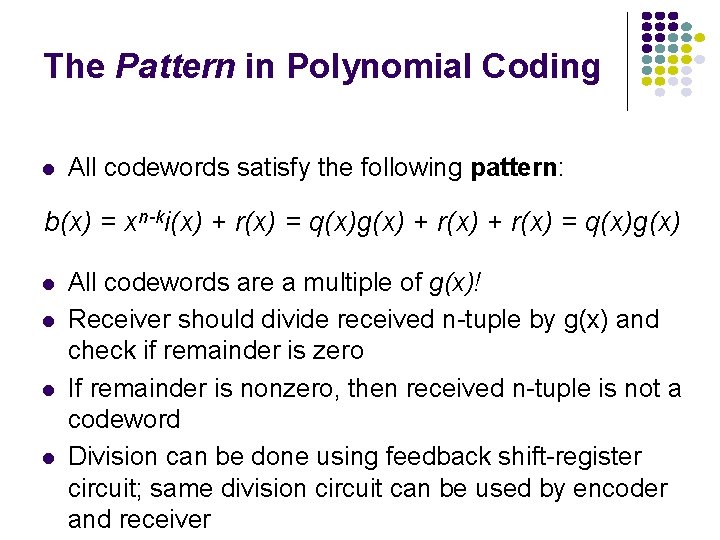

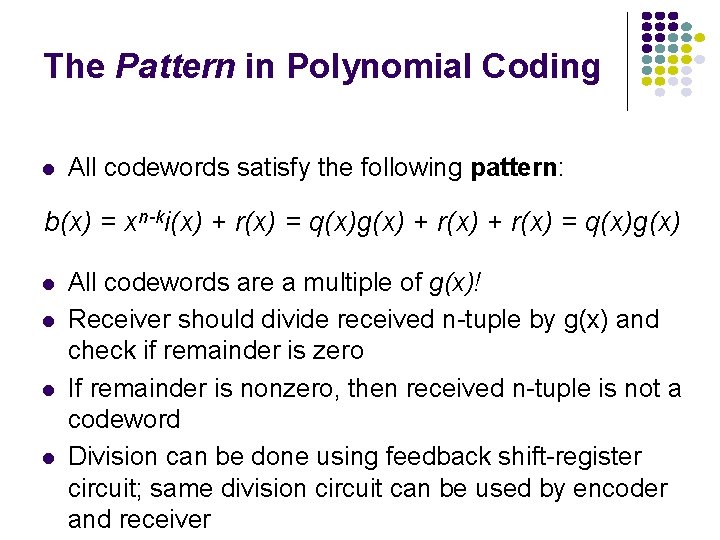

The Pattern in Polynomial Coding All codewords satisfy the following pattern: b(x) = xn-ki(x) + r(x) = q(x)g(x) All codewords are a multiple of g(x)! Receiver should divide received n-tuple by g(x) and check if remainder is zero If remainder is nonzero, then received n-tuple is not a codeword Division can be done using feedback shift-register circuit; same division circuit can be used by encoder and receiver

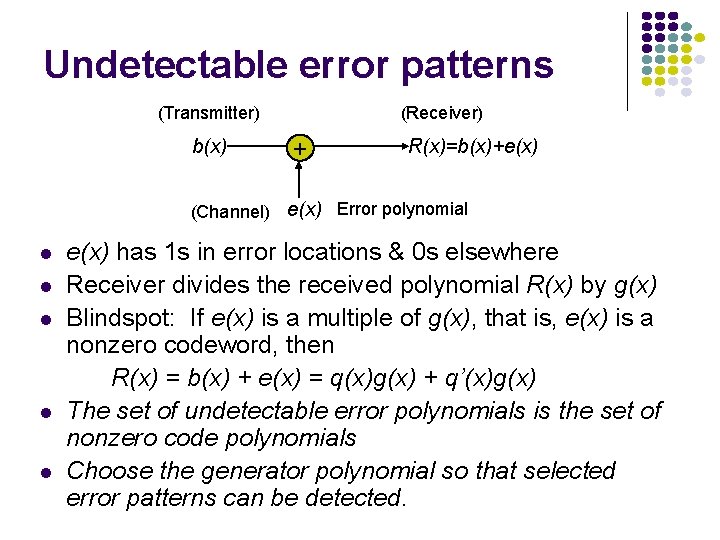

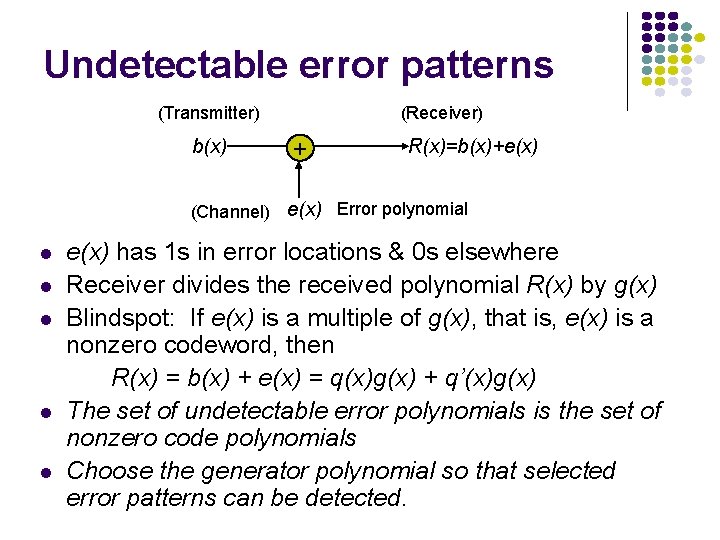

Undetectable error patterns (Transmitter) b(x) (Receiver) + R(x)=b(x)+e(x) (Channel) e(x) Error polynomial e(x) has 1 s in error locations & 0 s elsewhere Receiver divides the received polynomial R(x) by g(x) Blindspot: If e(x) is a multiple of g(x), that is, e(x) is a nonzero codeword, then R(x) = b(x) + e(x) = q(x)g(x) + q’(x)g(x) The set of undetectable error polynomials is the set of nonzero code polynomials Choose the generator polynomial so that selected error patterns can be detected.

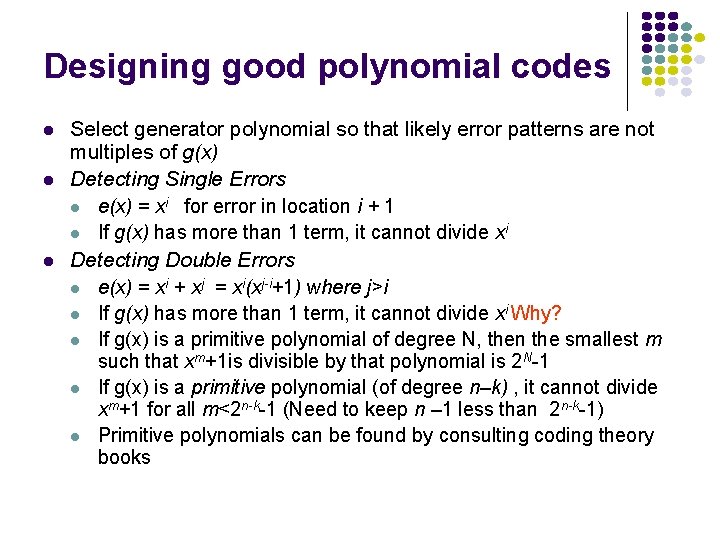

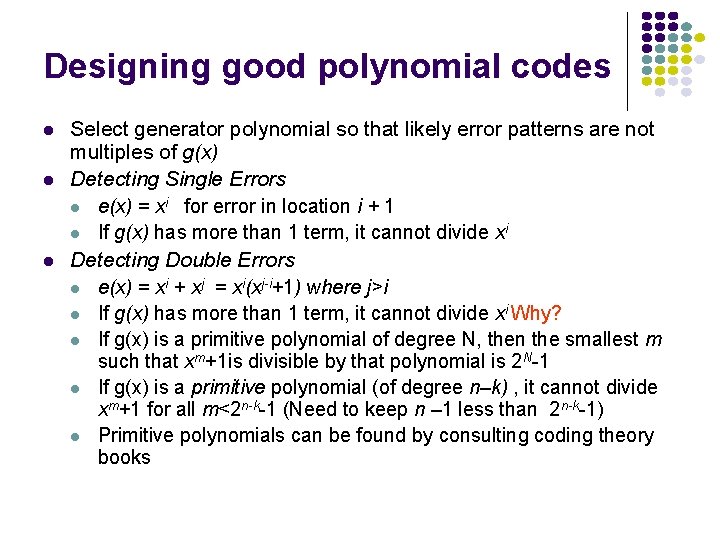

Designing good polynomial codes Select generator polynomial so that likely error patterns are not multiples of g(x) Detecting Single Errors e(x) = xi for error in location i + 1 If g(x) has more than 1 term, it cannot divide xi Detecting Double Errors e(x) = xi + xj = xi(xj-i+1) where j>i If g(x) has more than 1 term, it cannot divide xi Why? If g(x) is a primitive polynomial of degree N, then the smallest m such that xm+1 is divisible by that polynomial is 2 N-1 If g(x) is a primitive polynomial (of degree n–k) , it cannot divide xm+1 for all m<2 n-k-1 (Need to keep n – 1 less than 2 n-k-1) Primitive polynomials can be found by consulting coding theory books

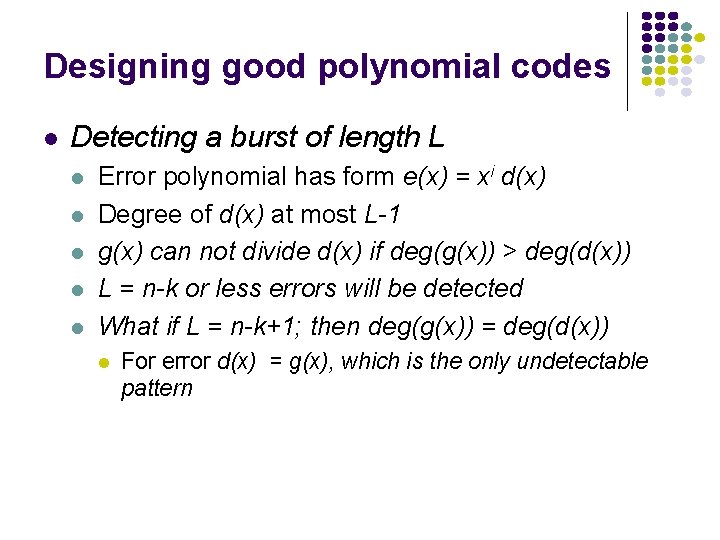

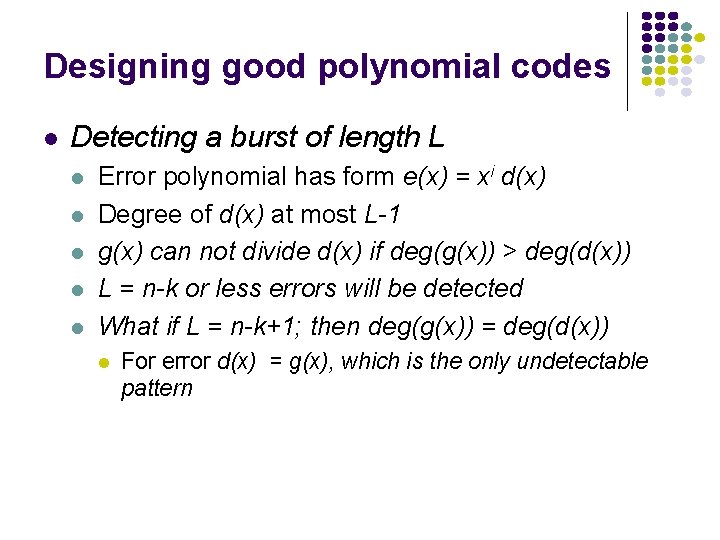

Designing good polynomial codes Detecting a burst of length L Error polynomial has form e(x) = xi d(x) Degree of d(x) at most L-1 g(x) can not divide d(x) if deg(g(x)) > deg(d(x)) L = n-k or less errors will be detected What if L = n-k+1; then deg(g(x)) = deg(d(x)) For error d(x) = g(x), which is the only undetectable pattern

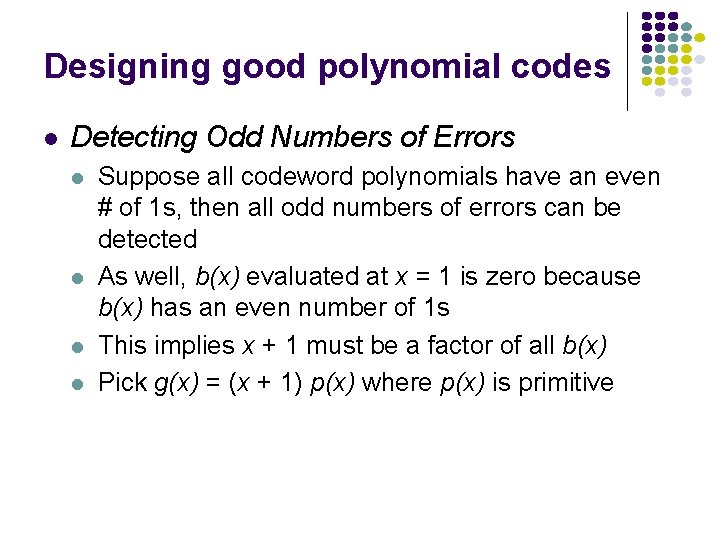

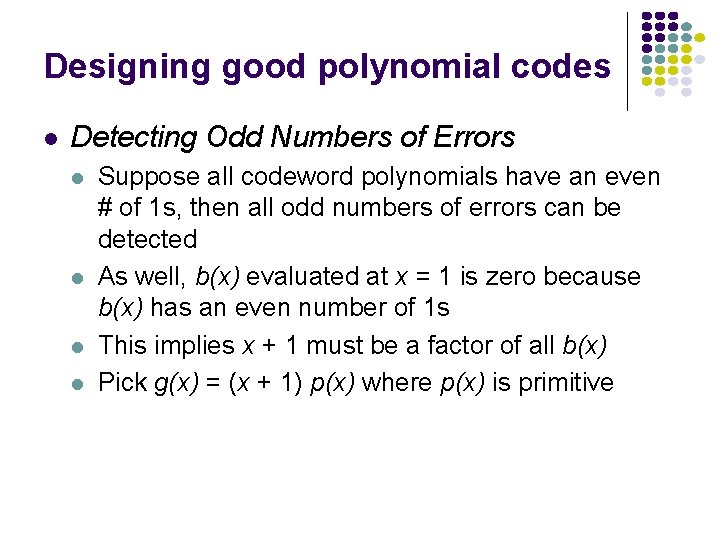

Designing good polynomial codes Detecting Odd Numbers of Errors Suppose all codeword polynomials have an even # of 1 s, then all odd numbers of errors can be detected As well, b(x) evaluated at x = 1 is zero because b(x) has an even number of 1 s This implies x + 1 must be a factor of all b(x) Pick g(x) = (x + 1) p(x) where p(x) is primitive

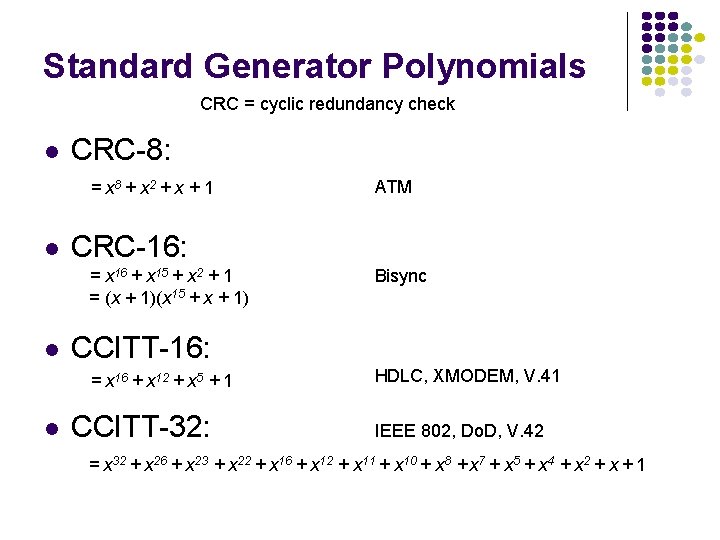

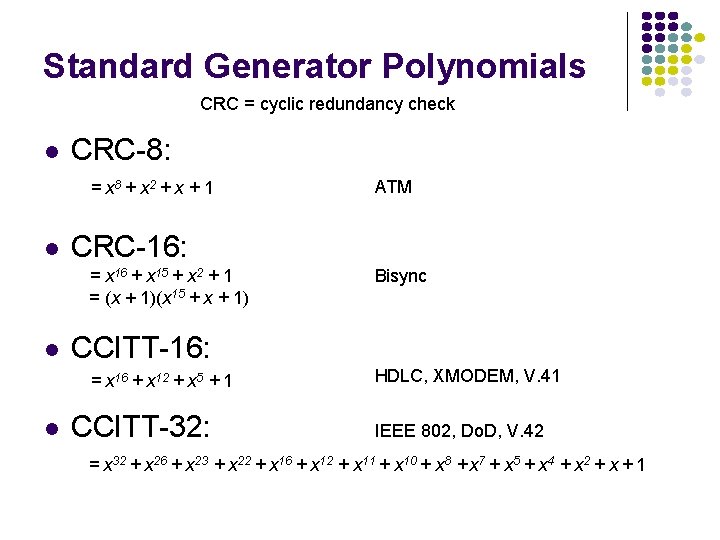

Standard Generator Polynomials CRC = cyclic redundancy check CRC-8: = x 8 + x 2 + x + 1 CRC-16: = x 16 + x 15 + x 2 + 1 = (x + 1)(x 15 + x + 1) Bisync CCITT-16: = x 16 + x 12 + x 5 + 1 ATM CCITT-32: HDLC, XMODEM, V. 41 IEEE 802, Do. D, V. 42 = x 32 + x 26 + x 23 + x 22 + x 16 + x 12 + x 11 + x 10 + x 8 + x 7 + x 5 + x 4 + x 2 + x + 1

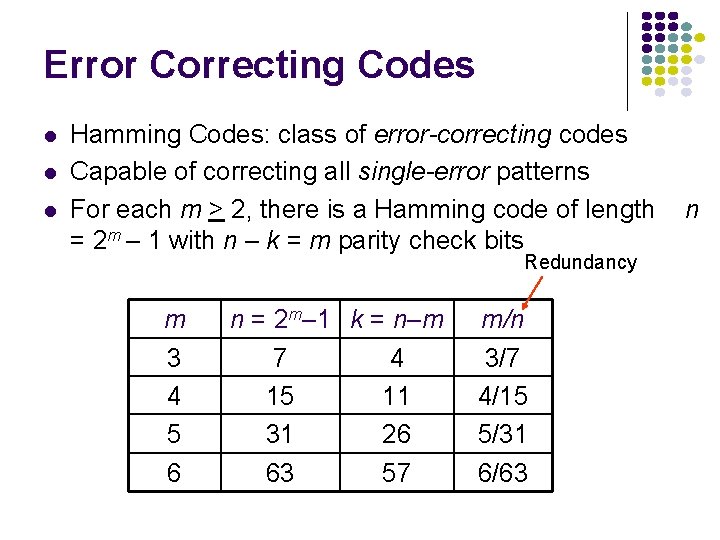

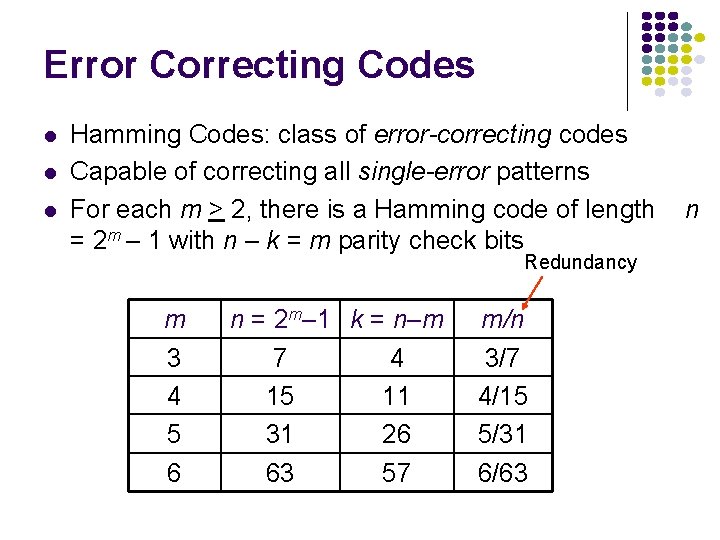

Error Correcting Codes Hamming Codes: class of error-correcting codes Capable of correcting all single-error patterns For each m > 2, there is a Hamming code of length = 2 m – 1 with n – k = m parity check bits Redundancy m 3 4 5 6 n = 2 m– 1 k = n–m 7 4 15 11 31 26 63 57 m/n 3/7 4/15 5/31 6/63 n

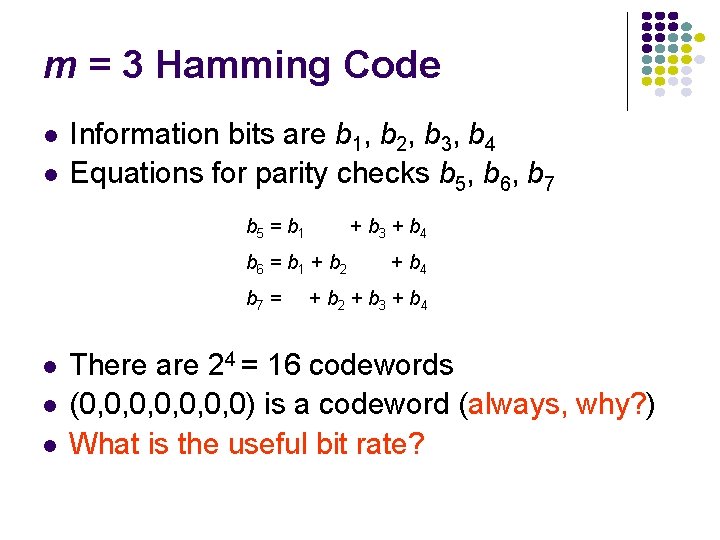

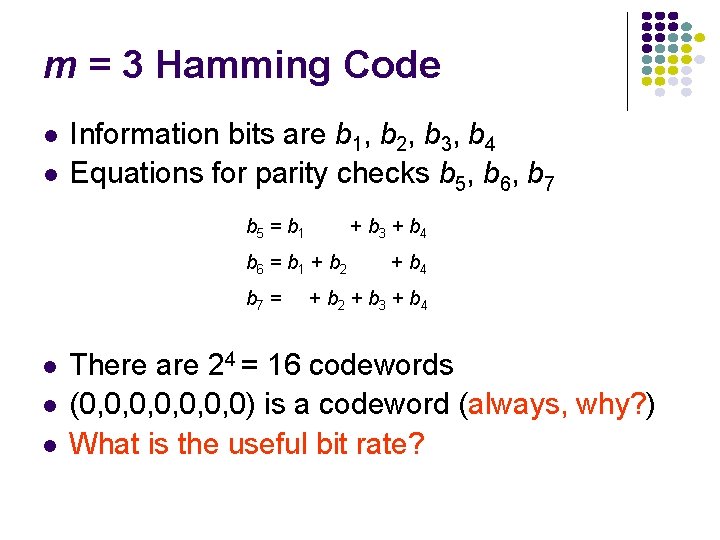

m = 3 Hamming Code Information bits are b 1, b 2, b 3, b 4 Equations for parity checks b 5, b 6, b 7 b 5 = b 1 + b 3 + b 4 b 6 = b 1 + b 2 b 7 = + b 4 + b 2 + b 3 + b 4 There are 24 = 16 codewords (0, 0, 0, 0) is a codeword (always, why? ) What is the useful bit rate?

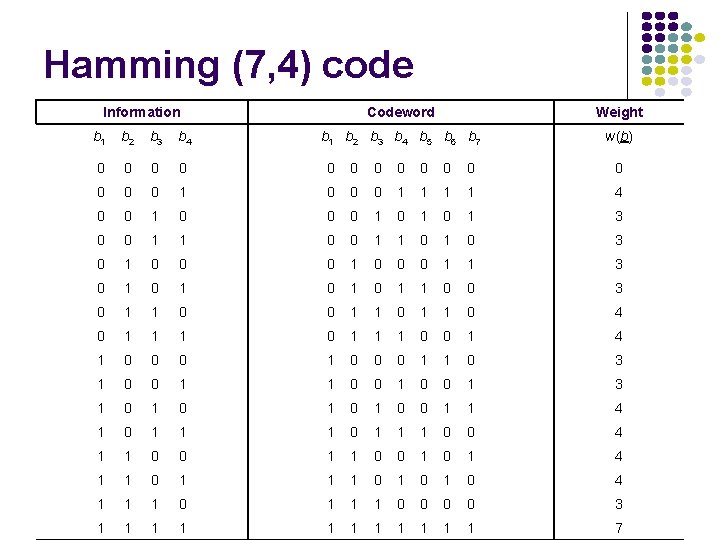

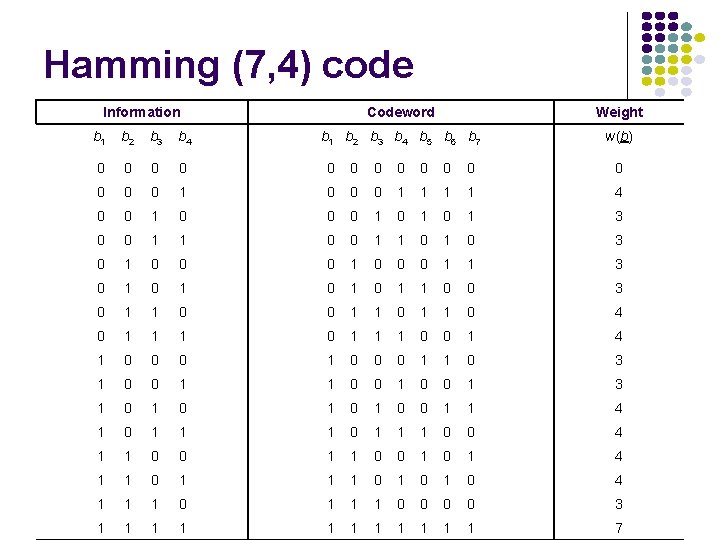

Hamming (7, 4) code Information Codeword Weight b 1 b 2 b 3 b 4 b 5 b 6 b 7 w(b) b 1 b 2 b 3 b 4 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 4 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 3 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 3 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 3 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 3 0 1 1 0 4 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 4 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 3 1 0 0 1 3 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 4 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 4 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 4 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 4 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 3 1 1 1 7

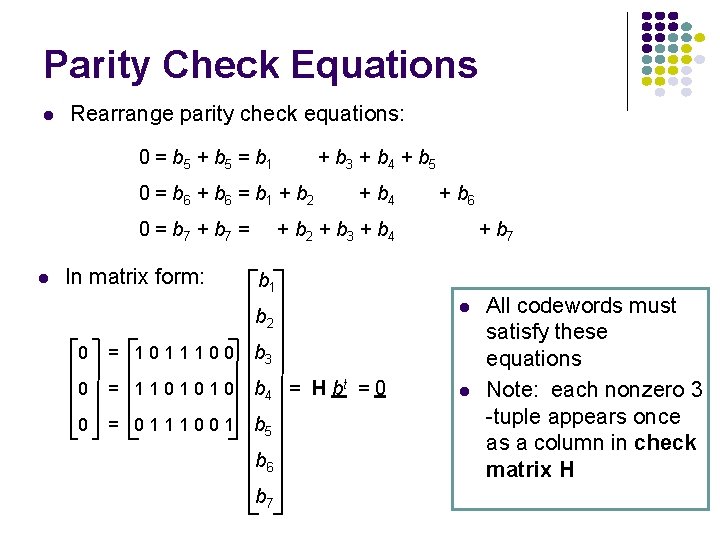

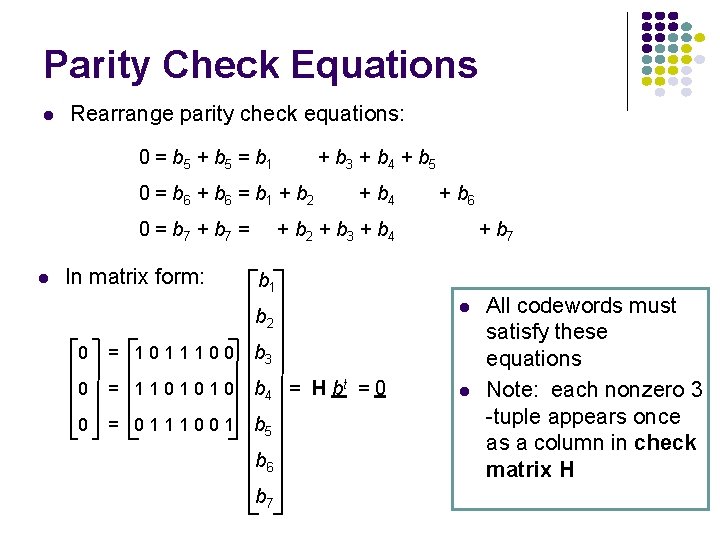

Parity Check Equations Rearrange parity check equations: 0 = b 5 + b 5 = b 1 + b 3 + b 4 + b 5 0 = b 6 + b 6 = b 1 + b 2 0 = b 7 + b 7 = In matrix form: + b 4 + b 6 + b 2 + b 3 + b 4 + b 7 b 1 b 2 0 = 1011100 b 3 0 = 1101010 b 4 = H bt = 0 0 = 0111001 b 5 b 6 b 7 All codewords must satisfy these equations Note: each nonzero 3 -tuple appears once as a column in check matrix H

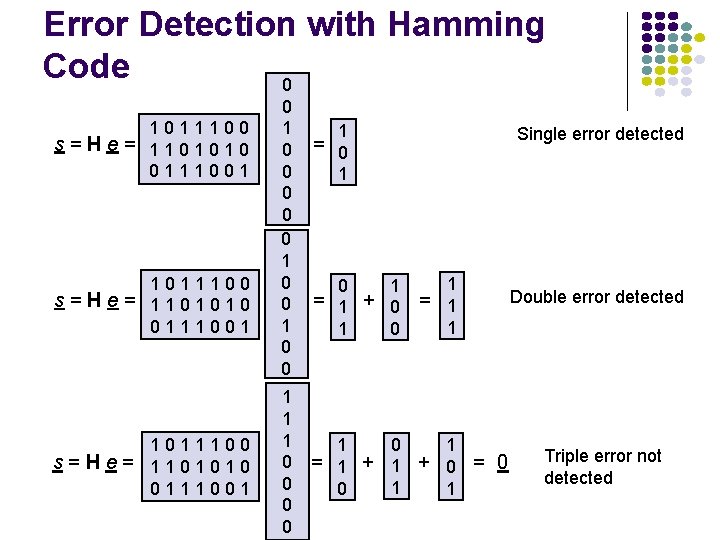

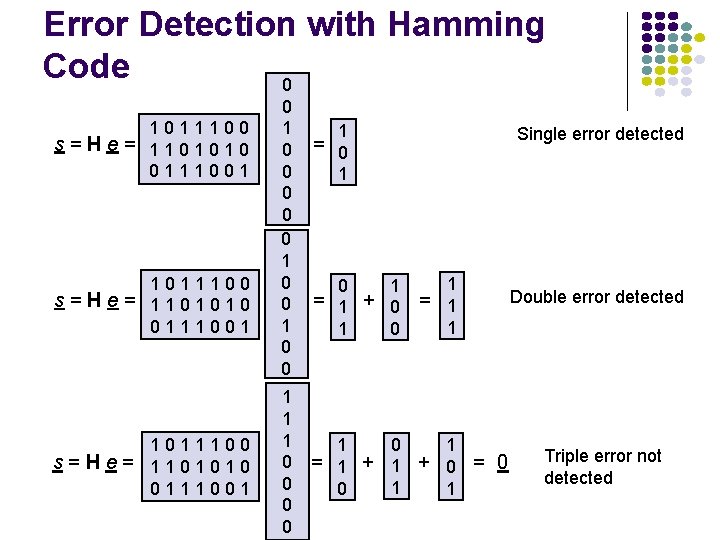

Error Detection with Hamming Code 0 1011100 s=He= 1101010 0111001 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 Single error detected = 0 1 0 1 = 1 + 0 1 = 1 1 0 1 1 + 0 = 0 1 1 Double error detected Triple error not detected

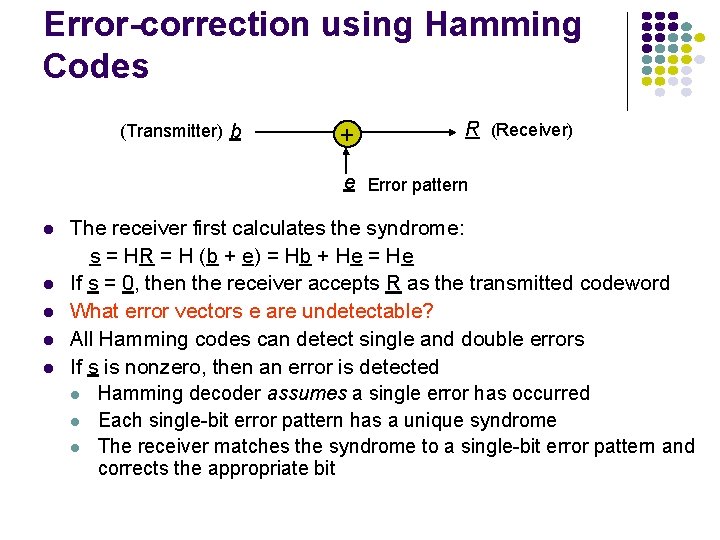

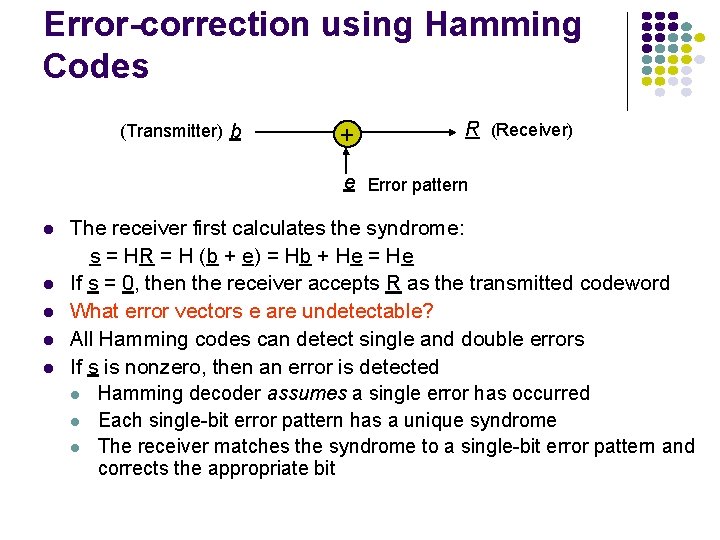

Error-correction using Hamming Codes (Transmitter) b + R (Receiver) e Error pattern The receiver first calculates the syndrome: s = HR = H (b + e) = Hb + He = He If s = 0, then the receiver accepts R as the transmitted codeword What error vectors e are undetectable? All Hamming codes can detect single and double errors If s is nonzero, then an error is detected Hamming decoder assumes a single error has occurred Each single-bit error pattern has a unique syndrome The receiver matches the syndrome to a single-bit error pattern and corrects the appropriate bit