Chapter 3 ContextFree Grammars Pushdown Store Automata Properties

![Conversion template w, A|ε q p Idea: [q, A, p] ⇒* w iff That Conversion template w, A|ε q p Idea: [q, A, p] ⇒* w iff That](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/29f1389ef2e4c2e4aa43cf0eed3afb5d/image-33.jpg)

![Example: S S → [q, S, f] a, A|AA a, B|ε a, S|AS ε, Example: S S → [q, S, f] a, A|AA a, B|ε a, S|AS ε,](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/29f1389ef2e4c2e4aa43cf0eed3afb5d/image-34.jpg)

- Slides: 41

Chapter 3 Context-Free Grammars Pushdown Store Automata Properties of the CFLs

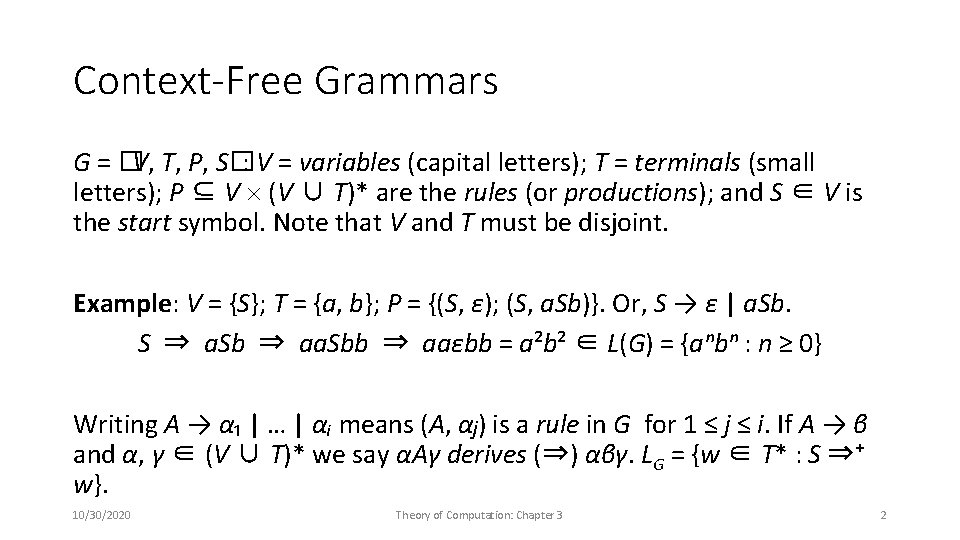

Context-Free Grammars G = �V, T, P, S�: V = variables (capital letters); T = terminals (small letters); P ⊆ V (V ∪ T)* are the rules (or productions); and S ∈ V is the start symbol. Note that V and T must be disjoint. Example: V = {S}; T = {a, b}; P = {(S, ε); (S, a. Sb)}. Or, S → ε | a. Sb. S ⇒ a. Sb ⇒ aa. Sbb ⇒ aaεbb = a²b² ∈ L(G) = {aⁿbⁿ : n ≥ 0} Writing A → α₁ | … | αᵢ means (A, αⱼ) is a rule in G for 1 ≤ j ≤ i. If A → β and α, γ ∈ (V ∪ T)* we say αAγ derives (⇒) αβγ. LG = {w ∈ T* : S ⇒⁺ w}. 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 2

Equal number of a ’s and b’s: L = {w ∈ {a , b}* : |w|a = |w|b} S → ε | a. B | b. A A → a | a. S | b. AA B → b | b. S | a. BB (equal number) (an extra a) (an extra b) LG ⊆ L: Show S ⇒* w only if |ω|a, A = |ω|b, B by proving each production preserves the surplus of a’s (A’s) vs. b’s (B’s); so ω has an equal number. L ⊆ LG: Show S ⇒* all strings with an equal number, A ⇒* all strings with an extra a, and B ⇒* all strings with an extra b, by induction Basis: S ⇒ ε; A ⇒ a; B ⇒ b. 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 3

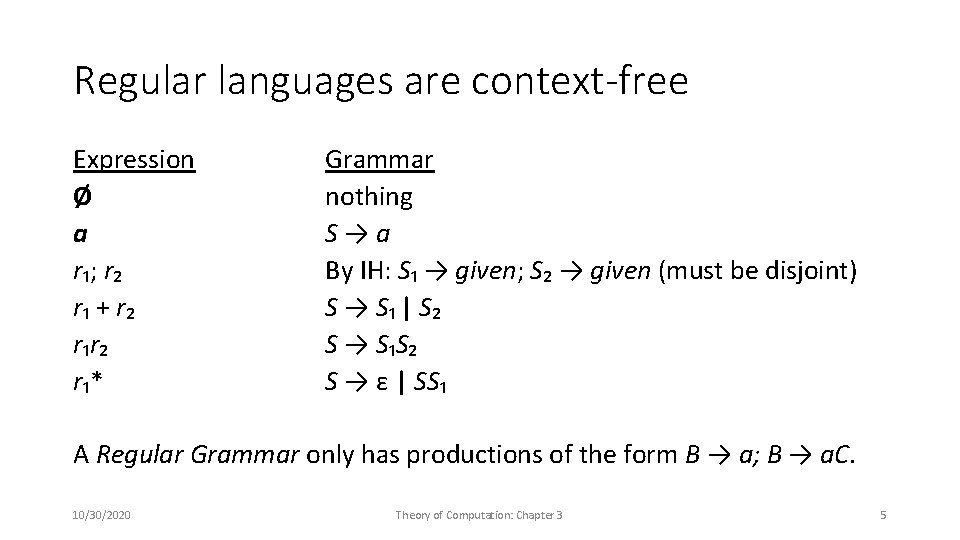

Simultaneous induction Inductive Cases (B is similar) / w = az z has an extra b S: ⇒ w = bz z has an extra a S ⇒ a. B ⇒* az Use by IH S ⇒ b. A ⇒* bz / w = az ⇒ z has equal nos. Use A ⇒ a. S ⇒* az by IH A: w = bz ⇒ z has 2 extra a’s ⇒ z = xy each with one extra a Use A ⇒ b. AA ⇒* bxy by IH 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 4

Regular languages are context-free Expression Ø a r₁; r₂ r₁ + r₂ r₁* Grammar nothing S → a By IH: S₁ → given; S₂ → given (must be disjoint) S → S₁ | S₂ S → S₁S₂ S → ε | SS₁ A Regular Grammar only has productions of the form B → a; B → a. C. 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 5

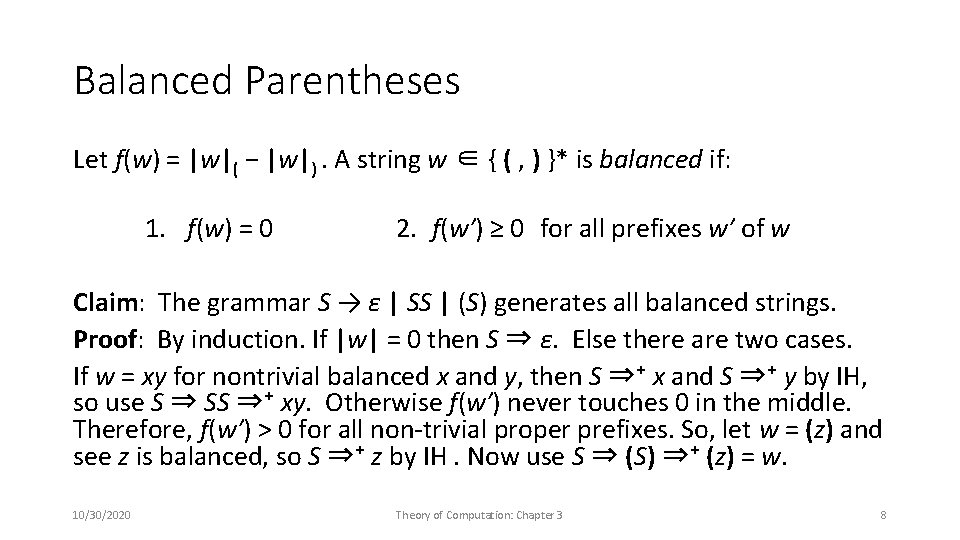

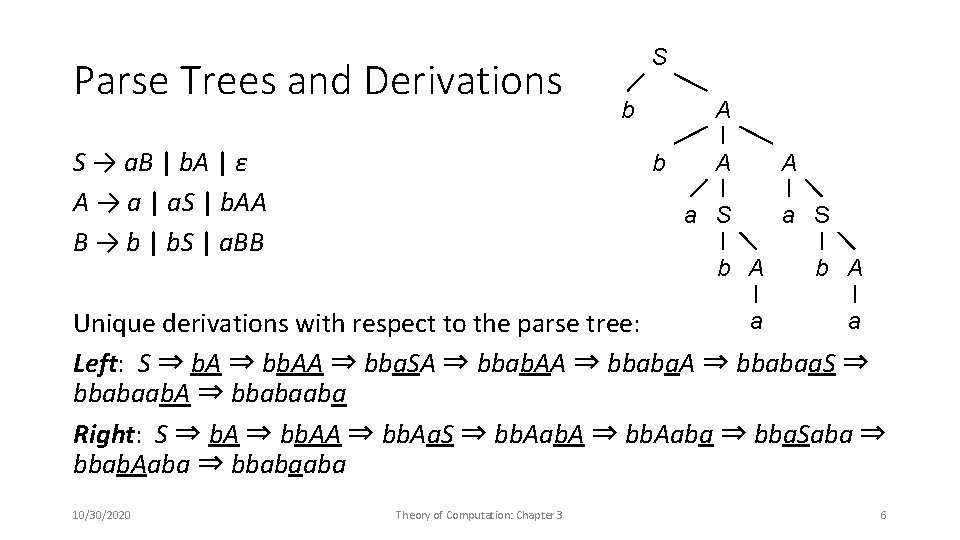

Parse Trees and Derivations S → a. B | b. A | ε A → a | a. S | b. AA B → b | b. S | a. BB S b A a S b A a a Unique derivations with respect to the parse tree: Left: S ⇒ b. A ⇒ bb. AA ⇒ bba. SA ⇒ bbab. AA ⇒ bbabaa. S ⇒ bbabaab. A ⇒ bbabaaba Right: S ⇒ b. A ⇒ bb. Aa. S ⇒ bb. Aab. A ⇒ bb. Aaba ⇒ bba. Saba ⇒ bbab. Aaba ⇒ bbabaaba 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 6

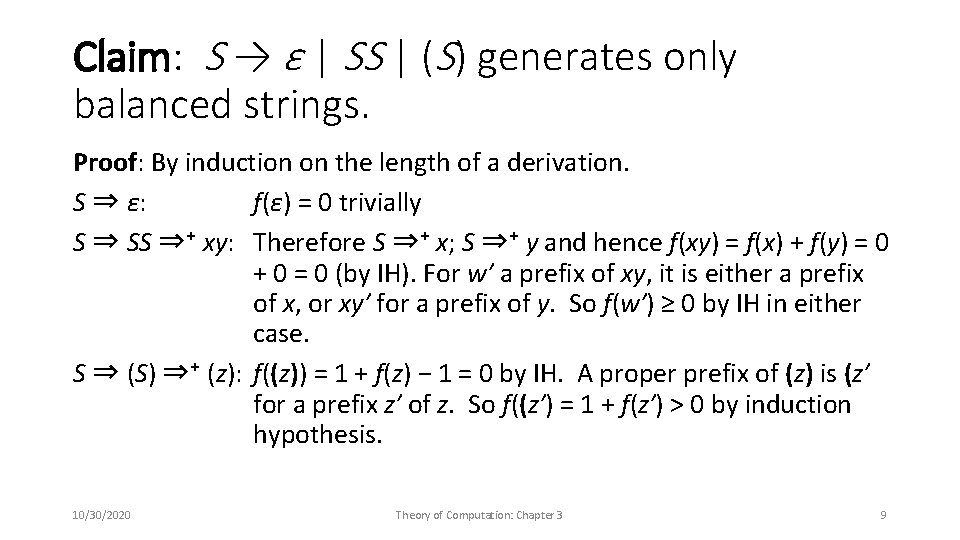

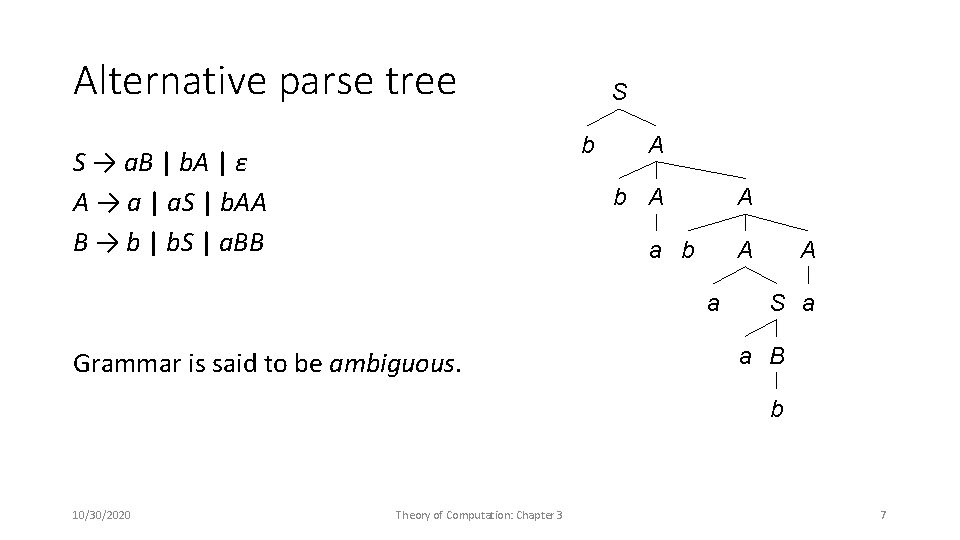

Alternative parse tree S b S → a. B | b. A | ε A → a | a. S | b. AA B → b | b. S | a. BB A b A A a b A a Grammar is said to be ambiguous. A S a a B b 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 7

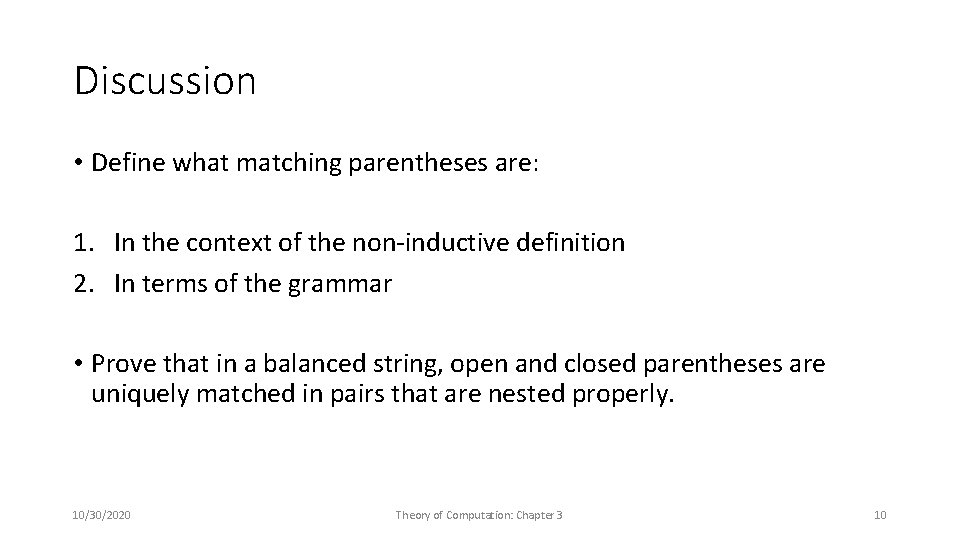

Balanced Parentheses Let f(w) = |w|( − |w|). A string w ∈ { ( , ) }* is balanced if: 1. f(w) = 0 2. f(w′) ≥ 0 for all prefixes w′ of w Claim: The grammar S → ε | SS | (S) generates all balanced strings. Proof: By induction. If |w| = 0 then S ⇒ ε. Else there are two cases. If w = xy for nontrivial balanced x and y, then S ⇒⁺ x and S ⇒⁺ y by IH, so use S ⇒ SS ⇒⁺ xy. Otherwise f(w′) never touches 0 in the middle. Therefore, f(w′) > 0 for all non-trivial proper prefixes. So, let w = (z) and see z is balanced, so S ⇒⁺ z by IH. Now use S ⇒ (S) ⇒⁺ (z) = w. 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 8

Claim: S → ε | SS | (S) generates only balanced strings. Proof: By induction on the length of a derivation. S ⇒ ε: f(ε) = 0 trivially S ⇒ SS ⇒⁺ xy: Therefore S ⇒⁺ x; S ⇒⁺ y and hence f(xy) = f(x) + f(y) = 0 + 0 = 0 (by IH). For w′ a prefix of xy, it is either a prefix of x, or xy′ for a prefix of y. So f(w′) ≥ 0 by IH in either case. S ⇒ (S) ⇒⁺ (z): f((z)) = 1 + f(z) − 1 = 0 by IH. A proper prefix of (z) is (z′ for a prefix z′ of z. So f((z′) = 1 + f(z′) > 0 by induction hypothesis. 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 9

Discussion • Define what matching parentheses are: 1. In the context of the non-inductive definition 2. In terms of the grammar • Prove that in a balanced string, open and closed parentheses are uniquely matched in pairs that are nested properly. 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 10

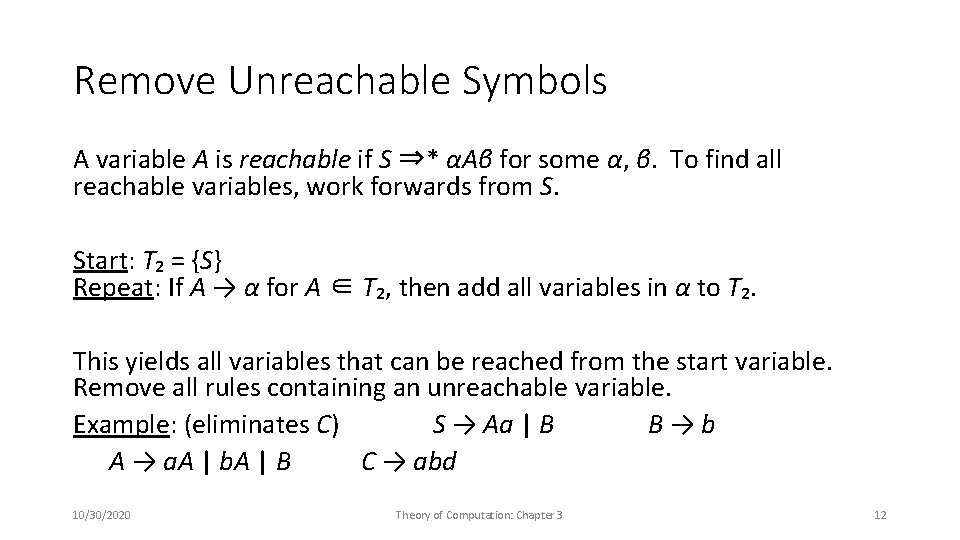

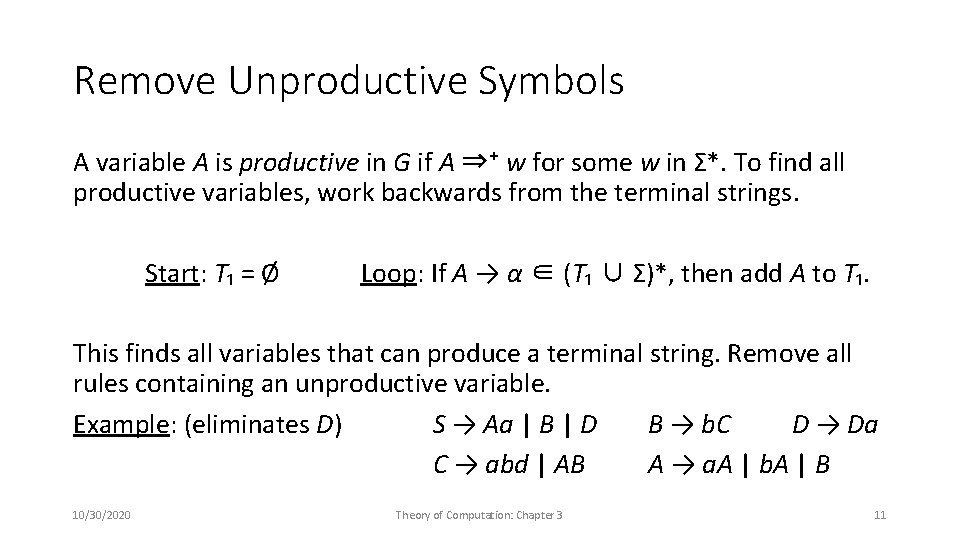

Remove Unproductive Symbols A variable A is productive in G if A ⇒⁺ w for some w in Σ*. To find all productive variables, work backwards from the terminal strings. Start: T₁ = Ø Loop: If A → α ∈ (T₁ ∪ Σ)*, then add A to T₁. This finds all variables that can produce a terminal string. Remove all rules containing an unproductive variable. Example: (eliminates D) S → Aa | B | D B → b. C D → Da C → abd | AB A → a. A | b. A | B 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 11

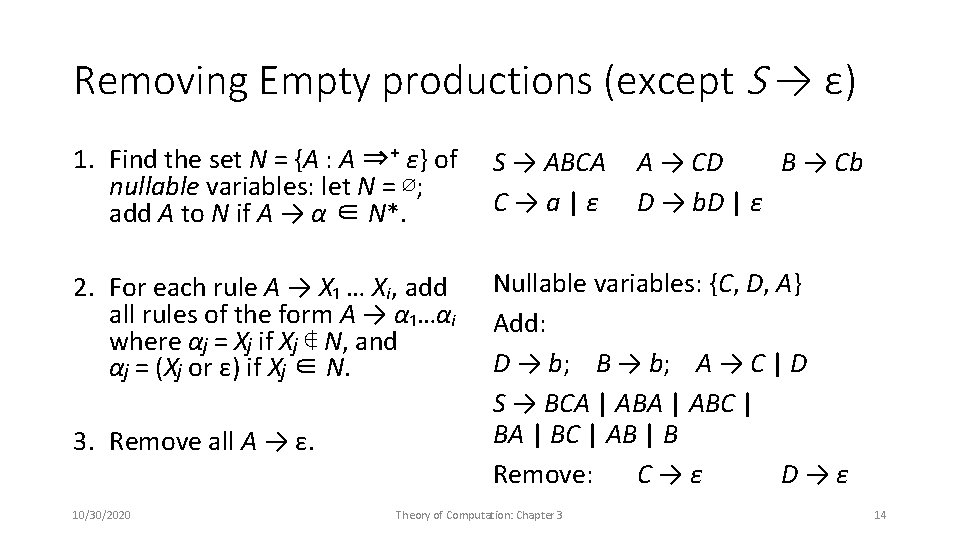

Remove Unreachable Symbols A variable A is reachable if S ⇒* αAβ for some α, β. To find all reachable variables, work forwards from S. Start: T₂ = {S} Repeat: If A → α for A ∈ T₂, then add all variables in α to T₂. This yields all variables that can be reached from the start variable. Remove all rules containing an unreachable variable. Example: (eliminates C) S → Aa | B B → b A → a. A | b. A | B C → abd 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 12

Removing Useless Symbols Definition: A variable A is useful if S ⇒* αAβ ⇒⁺ w ∈ Σ*. I. e. it participates in a derivation. (Even if all strings could be derived without using A, i. e. A is redundant. ) N. b. A must be productive and reachable. Theorem: Every non-empty CFL can be generated by a CFG without useless symbols. Proof: (1) First remove unproductive variables to get G₁. (2) Then remove unreachable variables to get G₂. Take any A ∈ T₂. By (2), there are α and β such that S ⇒₂* αAβ. But since αAβ ∈ (T₂ ∪ Σ)* and T₂ ⊆ T₁ (1) gives αAβ ⇒₁* w. But since all variables in this derivation are reachable from S, they are in T₂ also, and hence αAβ ⇒₂* w. Therefore A is useful in G₂. 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 13

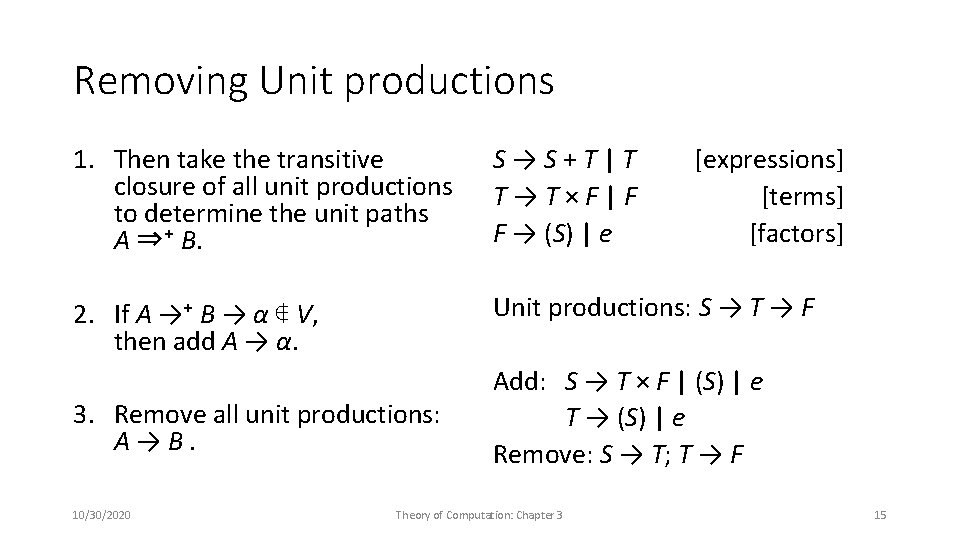

Removing Empty productions (except S → ε) 1. Find the set N = {A : A ⇒⁺ ε} of nullable variables: let N = ∅; add A to N if A → α ∈ N*. S → ABCA A → CD B → Cb C → a | ε D → b. D | ε 2. For each rule A → X₁ … Xᵢ, add all rules of the form A → α₁…αᵢ where αⱼ = Xⱼ if Xⱼ ∉ N, and αⱼ = (Xⱼ or ε) if Xⱼ ∈ N. Nullable variables: {C, D, A} Add: D → b; B → b; A → C | D S → BCA | ABC | BA | BC | AB | B Remove: C → ε D → ε 3. Remove all A → ε. 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 14

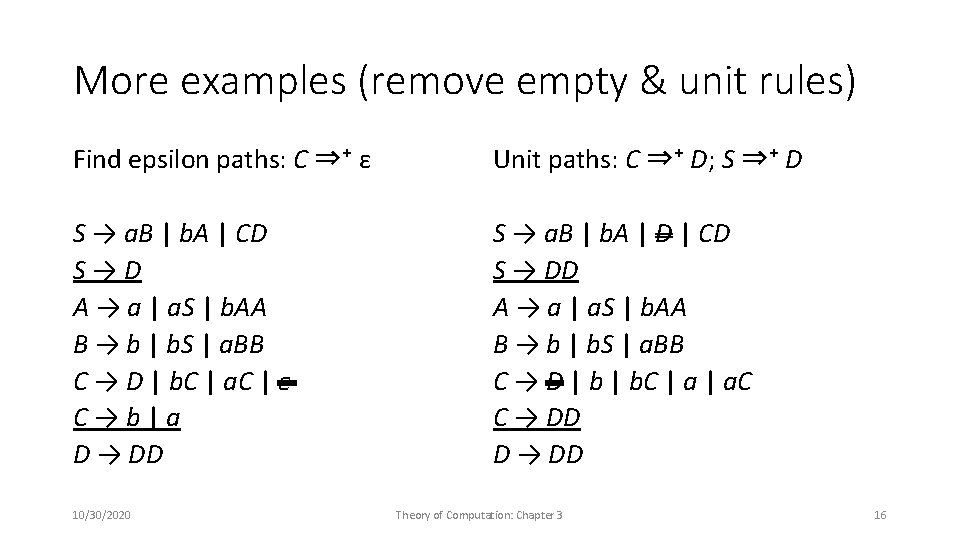

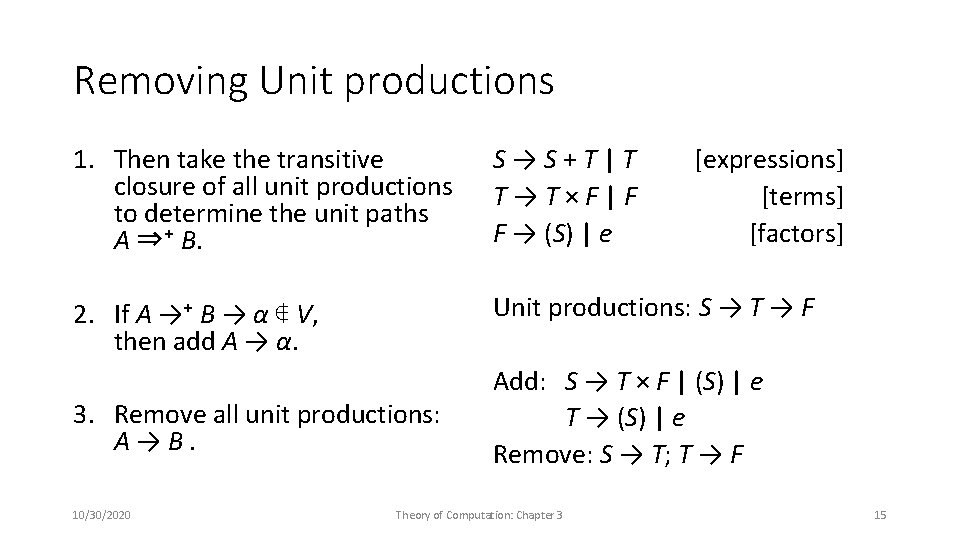

Removing Unit productions 1. Then take the transitive closure of all unit productions to determine the unit paths A ⇒⁺ B. S → S + T | T T → T × F | F F → (S) | e 2. If A →⁺ B → α ∉ V, then add A → α. Unit productions: S → T → F 3. Remove all unit productions: A → B. 10/30/2020 [expressions] [terms] [factors] Add: S → T × F | (S) | e T → (S) | e Remove: S → T; T → F Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 15

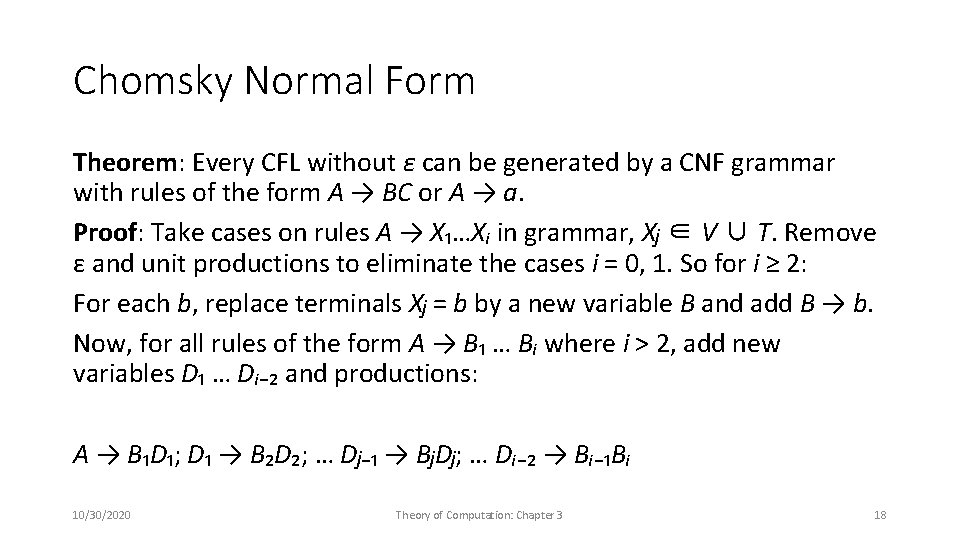

More examples (remove empty & unit rules) Find epsilon paths: C ⇒⁺ ε Unit paths: C ⇒⁺ D; S ⇒⁺ D S → a. B | b. A | CD S → D A → a | a. S | b. AA B → b | b. S | a. BB C → D | b. C | a. C | ε C → b | a D → DD S → a. B | b. A | D | CD S → DD A → a | a. S | b. AA B → b | b. S | a. BB C → D | b. C | a. C C → DD D → DD 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 16

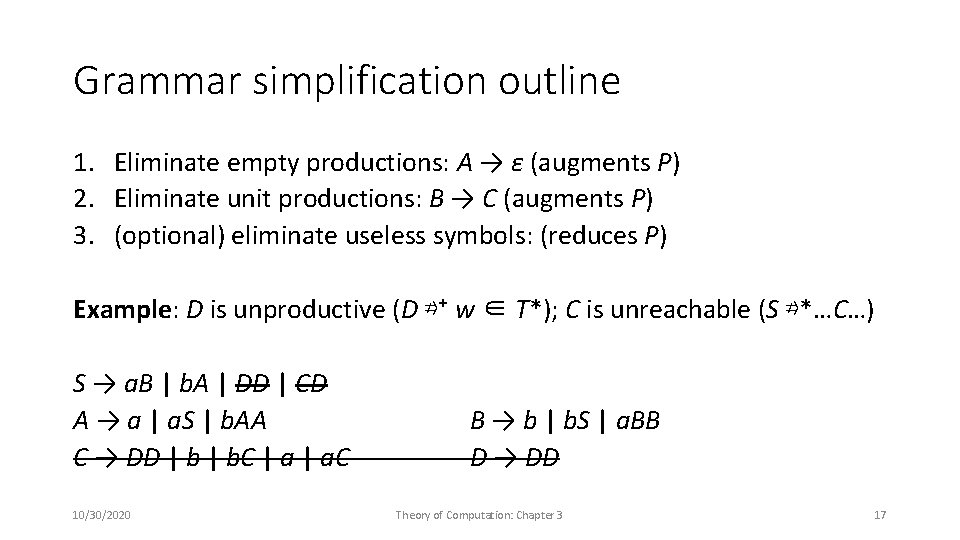

Grammar simplification outline 1. Eliminate empty productions: A → ε (augments P) 2. Eliminate unit productions: B → C (augments P) 3. (optional) eliminate useless symbols: (reduces P) Example: D is unproductive (D ⇏⁺ w ∈ T*); C is unreachable (S ⇏*…C…) S → a. B | b. A | DD | CD A → a | a. S | b. AA C → DD | b. C | a. C 10/30/2020 B → b | b. S | a. BB D → DD Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 17

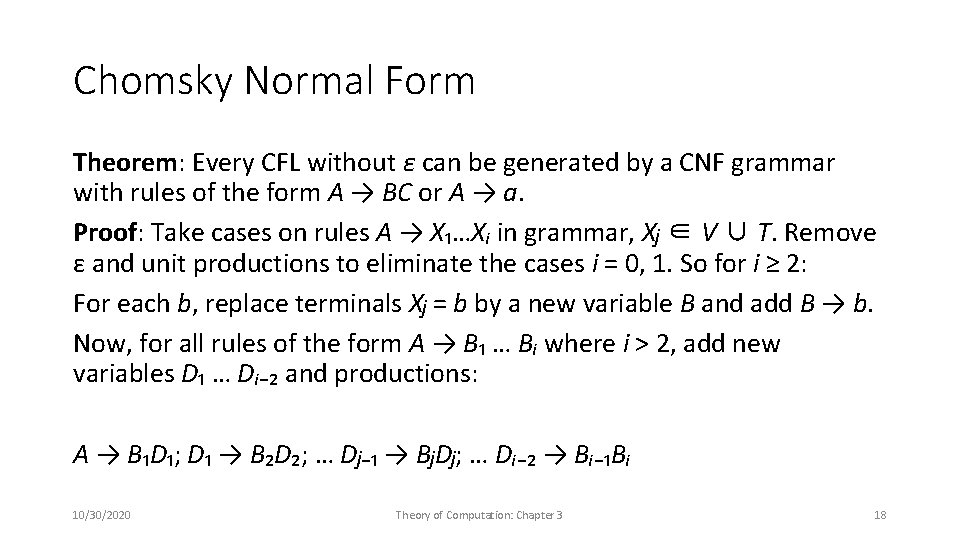

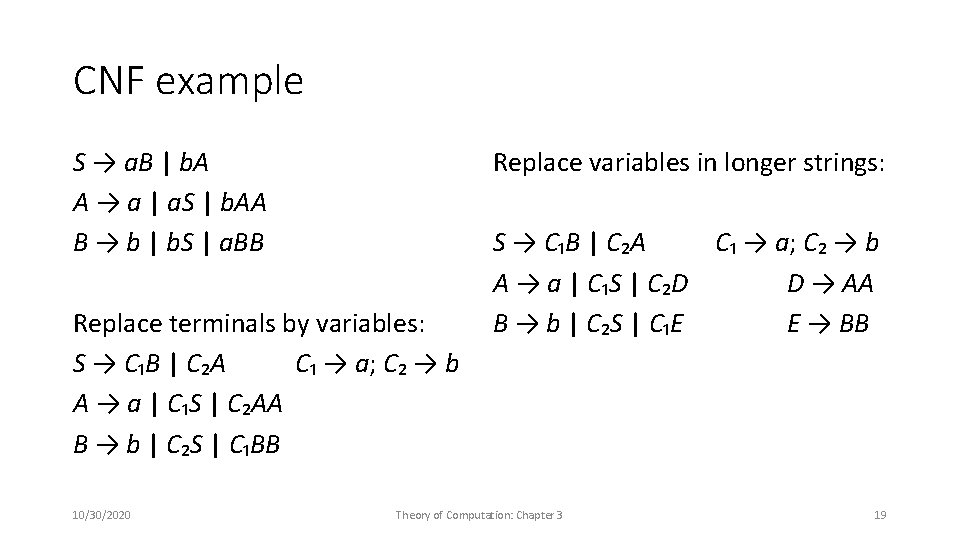

Chomsky Normal Form Theorem: Every CFL without ε can be generated by a CNF grammar with rules of the form A → BC or A → a. Proof: Take cases on rules A → X₁…Xᵢ in grammar, Xⱼ ∈ V ∪ T. Remove ε and unit productions to eliminate the cases i = 0, 1. So for i ≥ 2: For each b, replace terminals Xⱼ = b by a new variable B and add B → b. Now, for all rules of the form A → B₁ … Bᵢ where i > 2, add new variables D₁ … Dᵢ₋₂ and productions: A → B₁D₁; D₁ → B₂D₂; … Dⱼ₋₁ → BⱼDⱼ; … Dᵢ₋₂ → Bᵢ₋₁Bᵢ 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 18

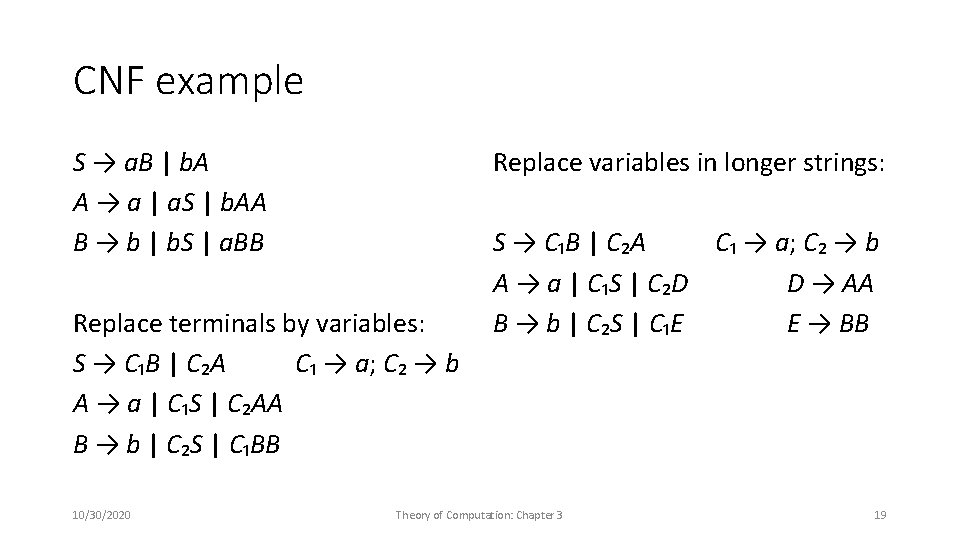

CNF example S → a. B | b. A A → a | a. S | b. AA B → b | b. S | a. BB Replace terminals by variables: S → C₁B | C₂A C₁ → a; C₂ → b A → a | C₁S | C₂AA B → b | C₂S | C₁BB 10/30/2020 Replace variables in longer strings: S → C₁B | C₂A C₁ → a; C₂ → b A → a | C₁S | C₂D D → AA B → b | C₂S | C₁E E → BB Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 19

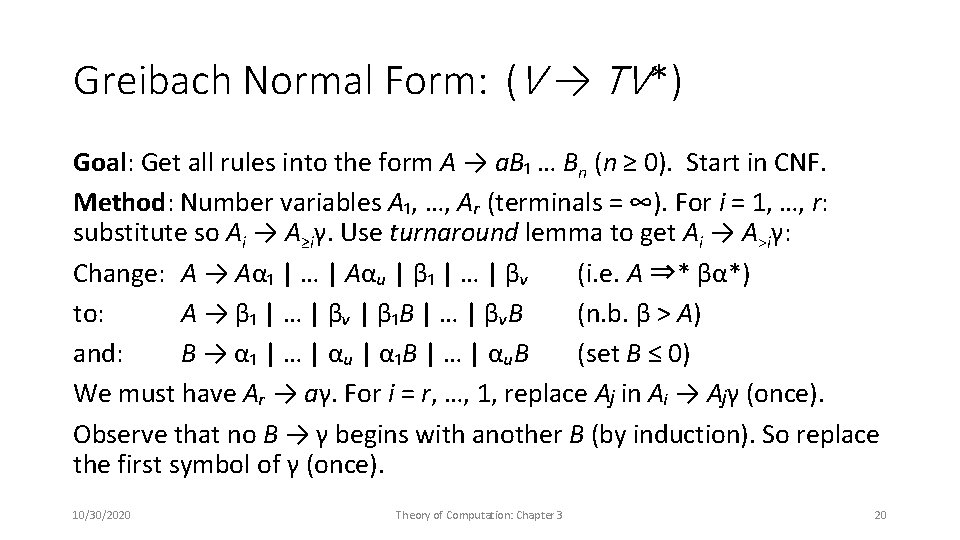

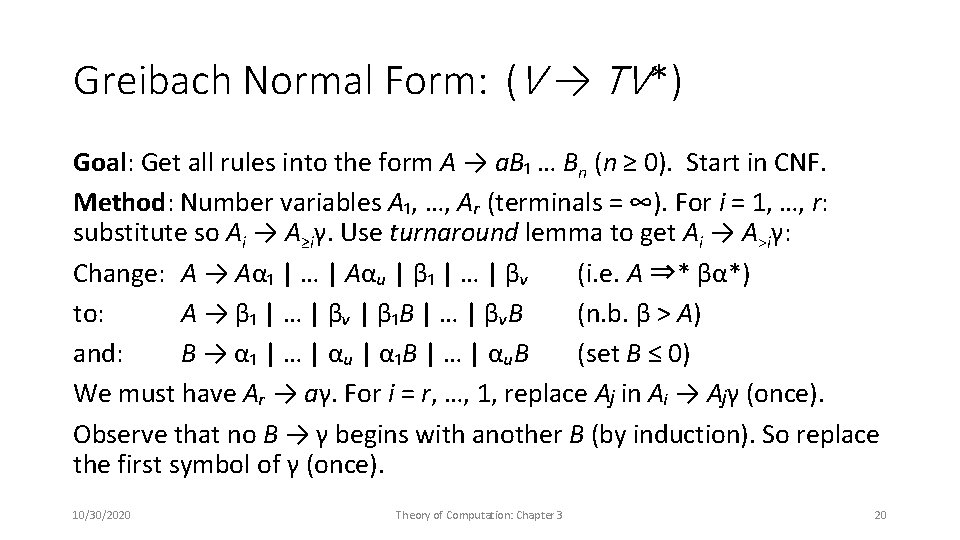

Greibach Normal Form: (V → TV*) Goal: Get all rules into the form A → a. B₁ … Bn (n ≥ 0). Start in CNF. Method: Number variables A₁, …, Aᵣ (terminals = ∞). For i = 1, …, r: substitute so Ai → A≥iγ. Use turnaround lemma to get Ai → A>iγ: Change: A → Aα₁ | … | Aαᵤ | β₁ | … | βᵥ (i. e. A ⇒* βα*) to: A → β₁ | … | βᵥ | β₁B | … | βᵥB (n. b. β > A) and: B → α₁ | … | αᵤ | α₁B | … | αᵤB (set B ≤ 0) We must have Aᵣ → aγ. For i = r, …, 1, replace Aⱼ in Aᵢ → Aⱼγ (once). Observe that no B → γ begins with another B (by induction). So replace the first symbol of γ (once). 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 20

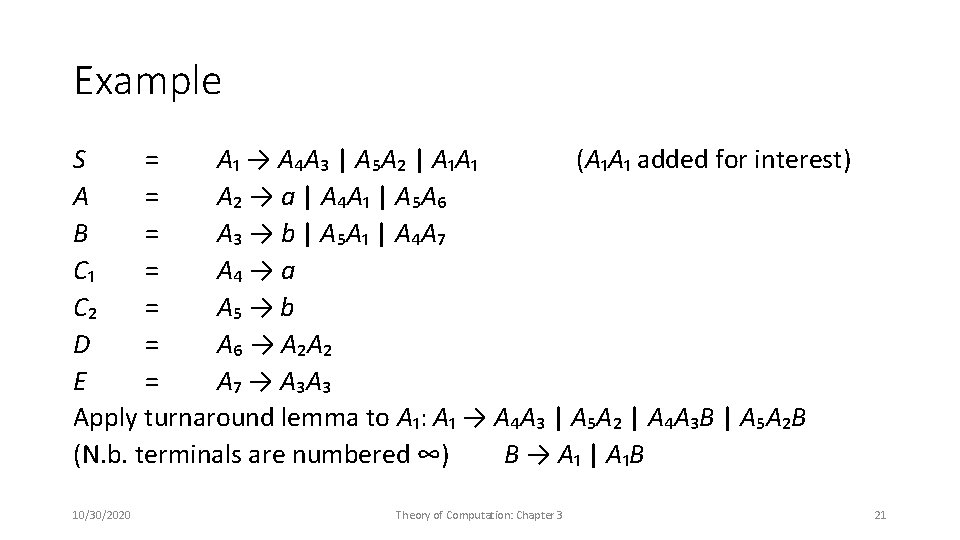

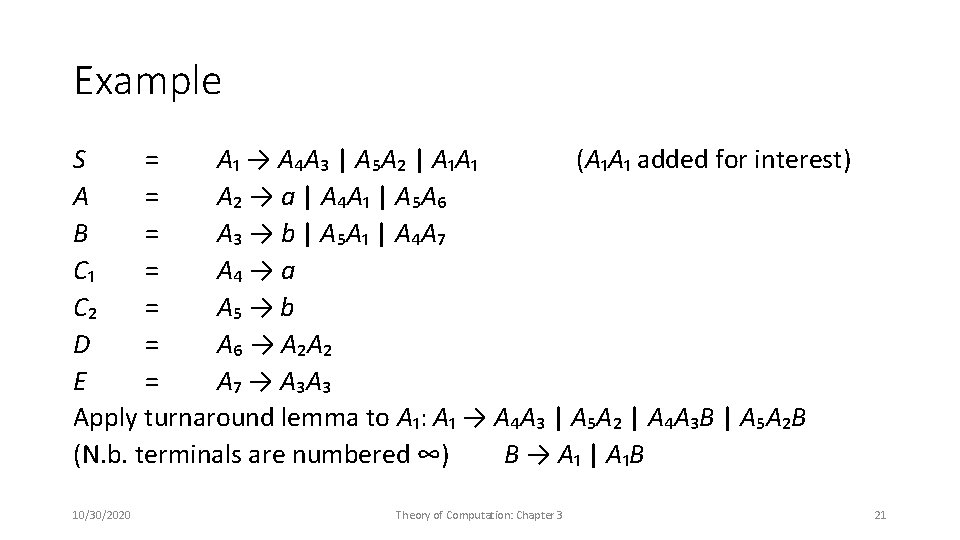

Example S = A₁ → A₄A₃ | A₅A₂ | A₁A₁ (A₁A₁ added for interest) A = A₂ → a | A₄A₁ | A₅A₆ B = A₃ → b | A₅A₁ | A₄A₇ C₁ = A₄ → a C₂ = A₅ → b D = A₆ → A₂A₂ E = A₇ → A₃A₃ Apply turnaround lemma to A₁: A₁ → A₄A₃ | A₅A₂ | A₄A₃B | A₅A₂B (N. b. terminals are numbered ∞) B → A₁ | A₁B 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 21

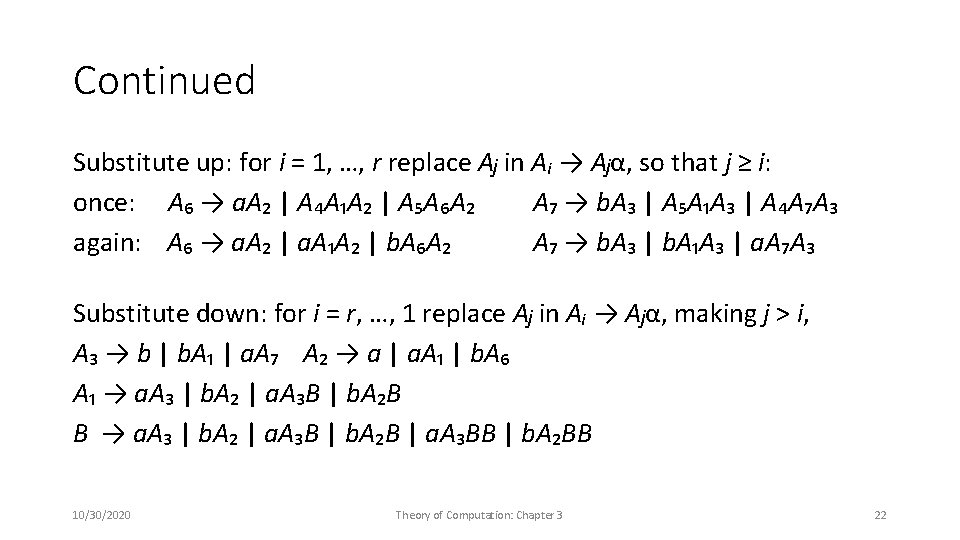

Continued Substitute up: for i = 1, …, r replace Aⱼ in Aᵢ → Aⱼα, so that j ≥ i: once: A₆ → a. A₂ | A₄A₁A₂ | A₅A₆A₂ A₇ → b. A₃ | A₅A₁A₃ | A₄A₇A₃ again: A₆ → a. A₂ | a. A₁A₂ | b. A₆A₂ A₇ → b. A₃ | b. A₁A₃ | a. A₇A₃ Substitute down: for i = r, …, 1 replace Aⱼ in Aᵢ → Aⱼα, making j > i, A₃ → b | b. A₁ | a. A₇ A₂ → a | a. A₁ | b. A₆ A₁ → a. A₃ | b. A₂ | a. A₃B | b. A₂B B → a. A₃ | b. A₂ | a. A₃B | b. A₂B | a. A₃BB | b. A₂BB 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 22

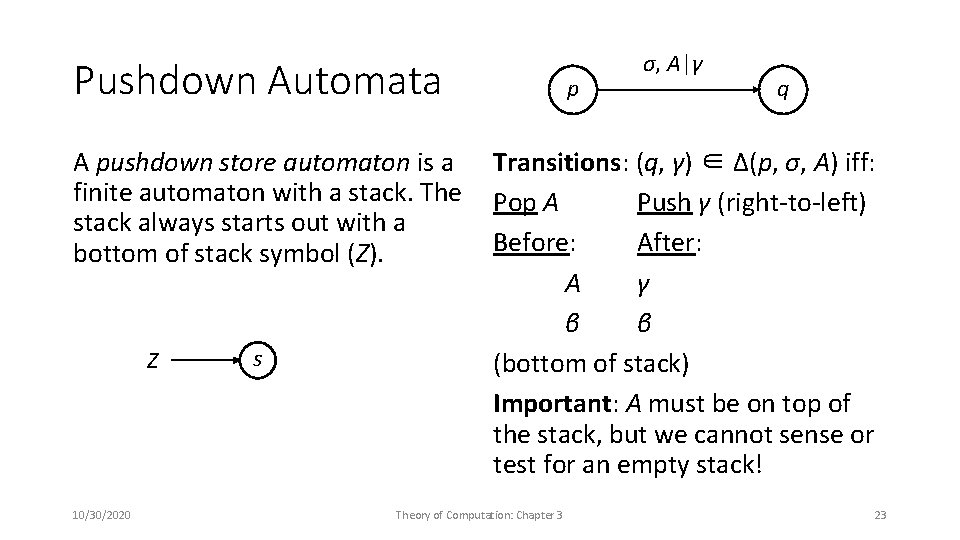

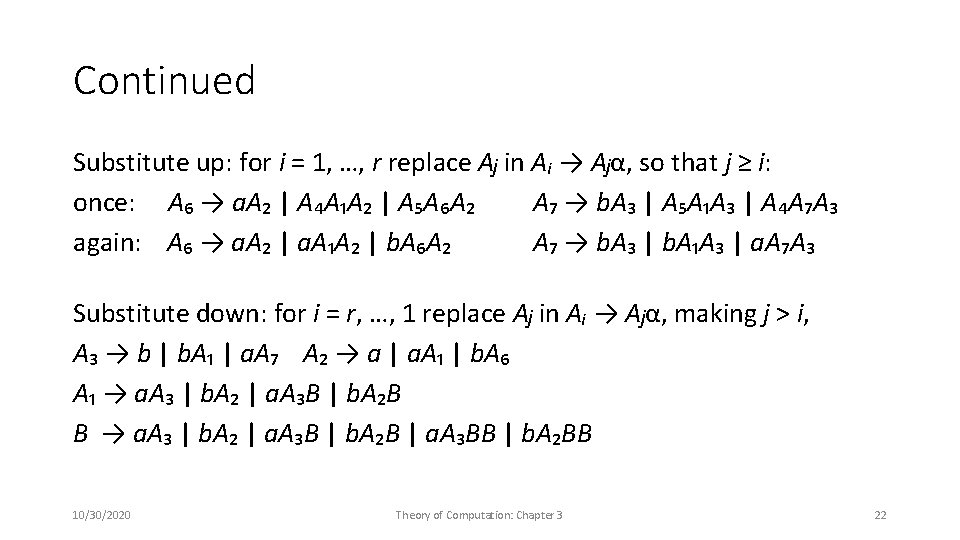

Pushdown Automata p σ, A|γ q A pushdown store automaton is a Transitions: (q, γ) ∈ Δ(p, σ, A) iff: finite automaton with a stack. The Pop A Push γ (right-to-left) stack always starts out with a Before: After: bottom of stack symbol (Z). A γ β β s Z (bottom of stack) Important: A must be on top of the stack, but we cannot sense or test for an empty stack! 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 23

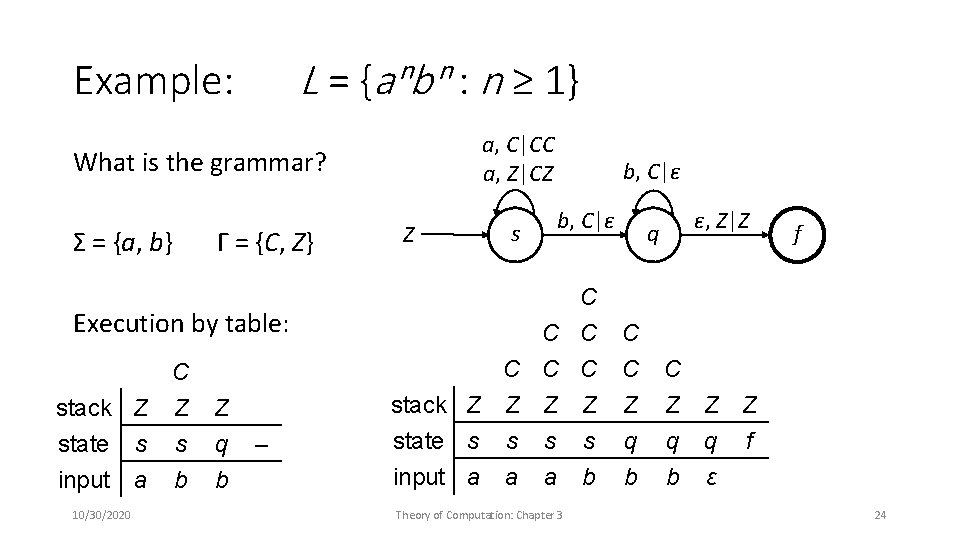

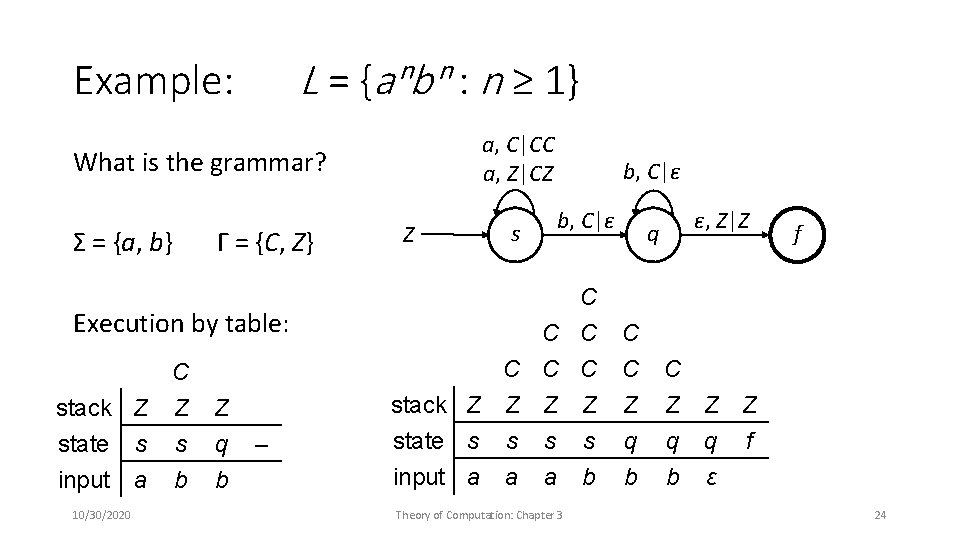

L = {aⁿbⁿ : n ≥ 1} Example: a, C|CC a, Z|CZ What is the grammar? Σ = {a, b} Γ = {C, Z} Execution by table: stack Z state s input a 10/30/2020 C Z s b Z q b – Z s b, C|ε ε, Z|Z q C C C stack Z Z C C Z Z Z state s input a q b s a Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 s b q ε f f 24

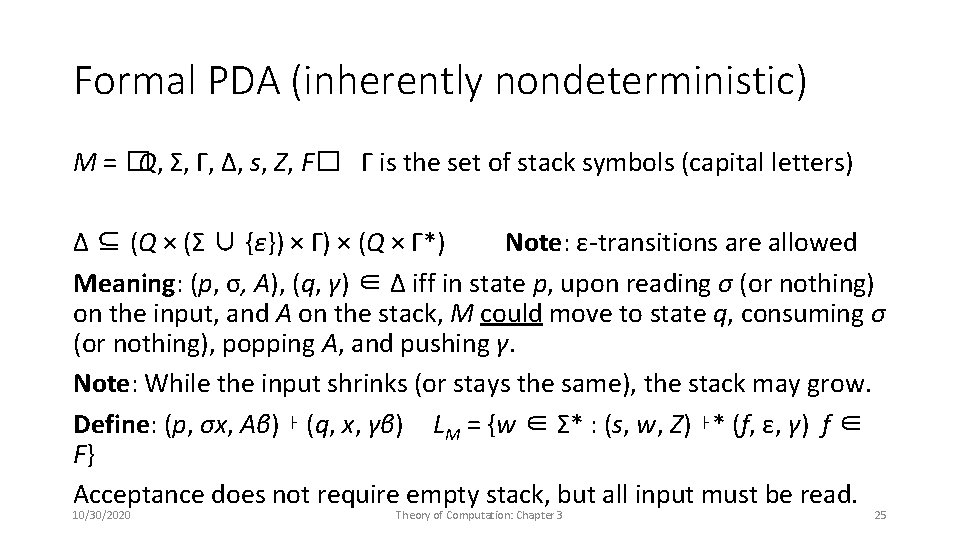

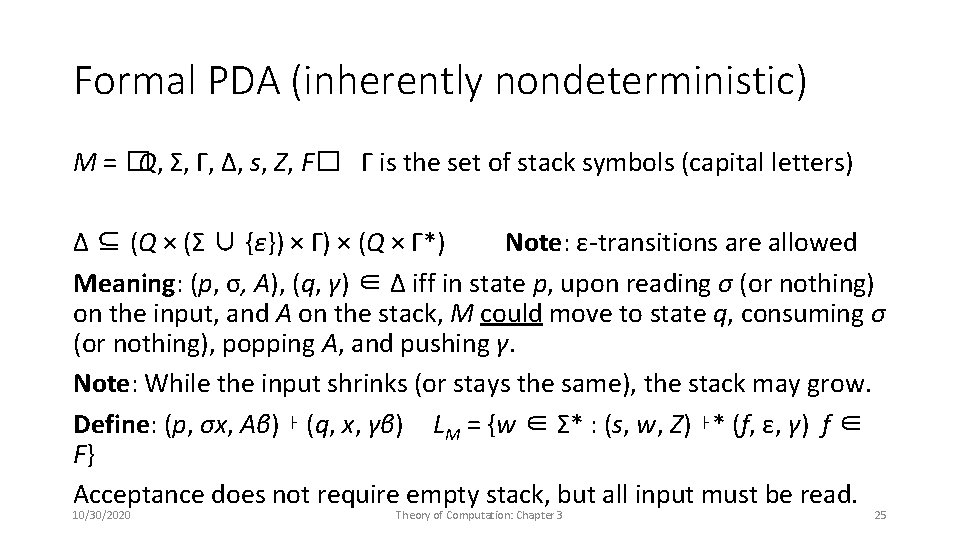

Formal PDA (inherently nondeterministic) M = �Q, Σ, Γ, Δ, s, Z, F� Γ is the set of stack symbols (capital letters) Δ ⊆ (Q × (Σ ∪ {ε}) × Γ) × (Q × Γ*) Note: ε-transitions are allowed Meaning: (p, σ, A), (q, γ) ∈ Δ iff in state p, upon reading σ (or nothing) on the input, and A on the stack, M could move to state q, consuming σ (or nothing), popping A, and pushing γ. Note: While the input shrinks (or stays the same), the stack may grow. Define: (p, σx, Aβ) ⊦ (q, x, γβ) LM = {w ∈ Σ* : (s, w, Z) ⊦* (f, ε, γ) f ∈ F} Acceptance does not require empty stack, but all input must be read. 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 25

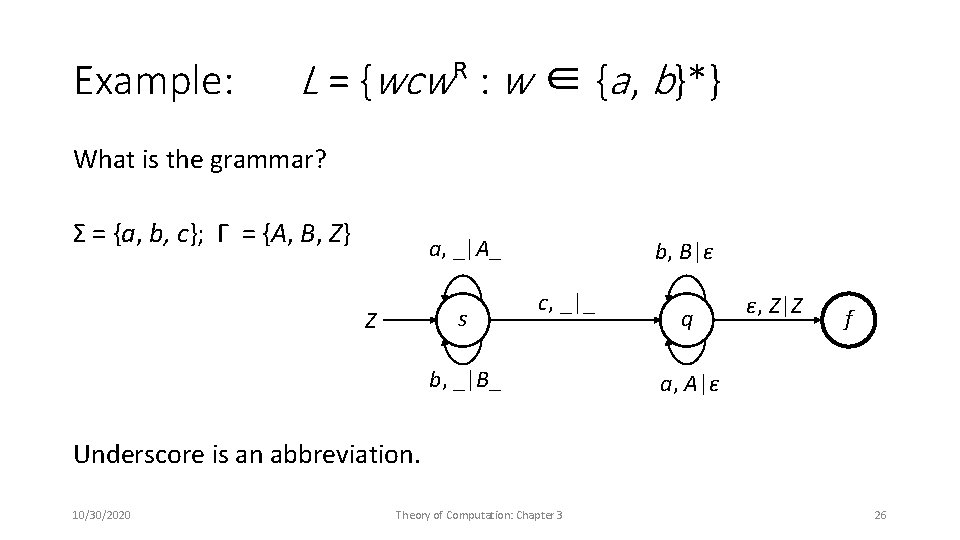

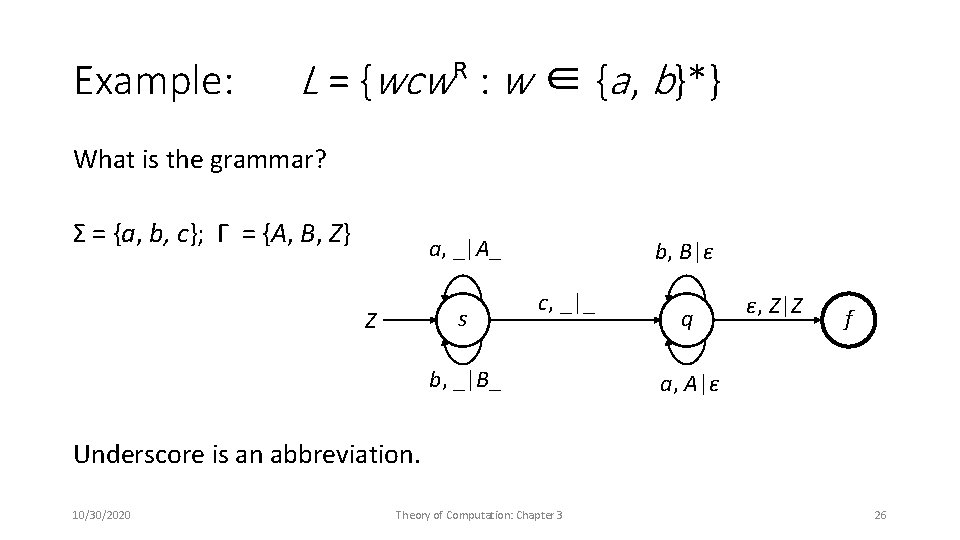

Example: L = {wcwᴿ : w ∈ {a , b}*} What is the grammar? Σ = {a, b, c}; Γ = {A, B, Z} a, _|A_ s Z b, B|ε c, _|_ b, _|B_ q ε, Z|Z f a, A|ε Underscore is an abbreviation. 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 26

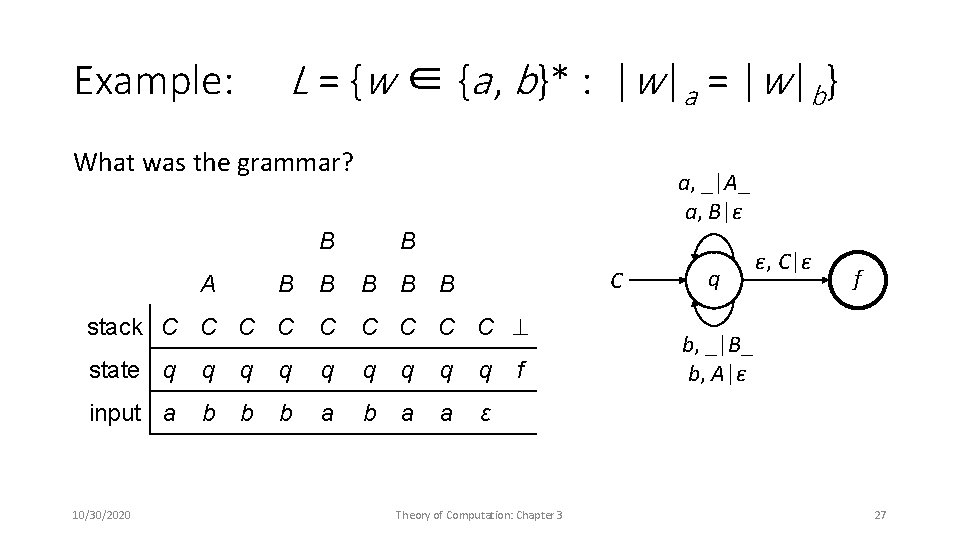

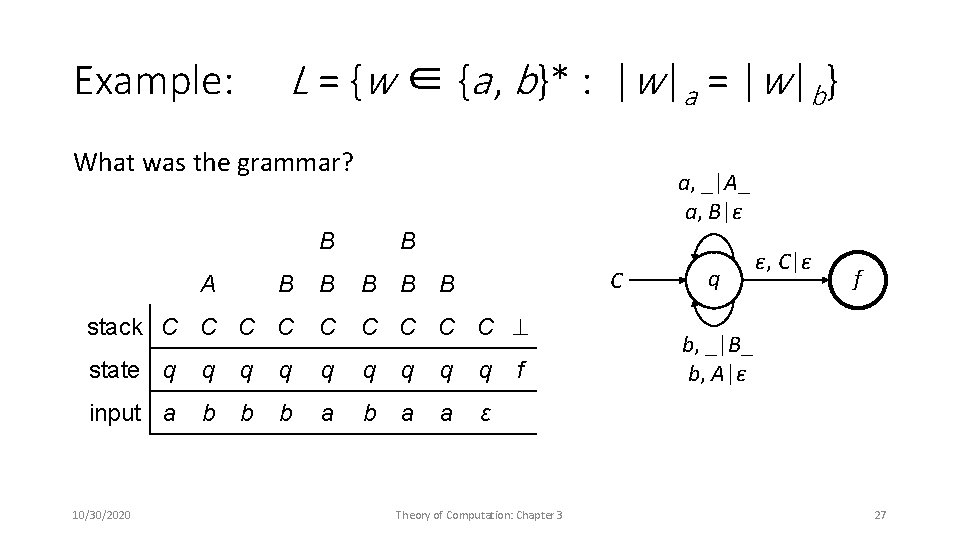

L = {w ∈ {a , b}* : |w|a = |w|b} Example: What was the grammar? a, _|A_ a, B|ε B B B B stack C C C C C state q q q q q input a b b b a a ε A 10/30/2020 C f Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 q ε, C|ε f b, _|B_ b, A|ε 27

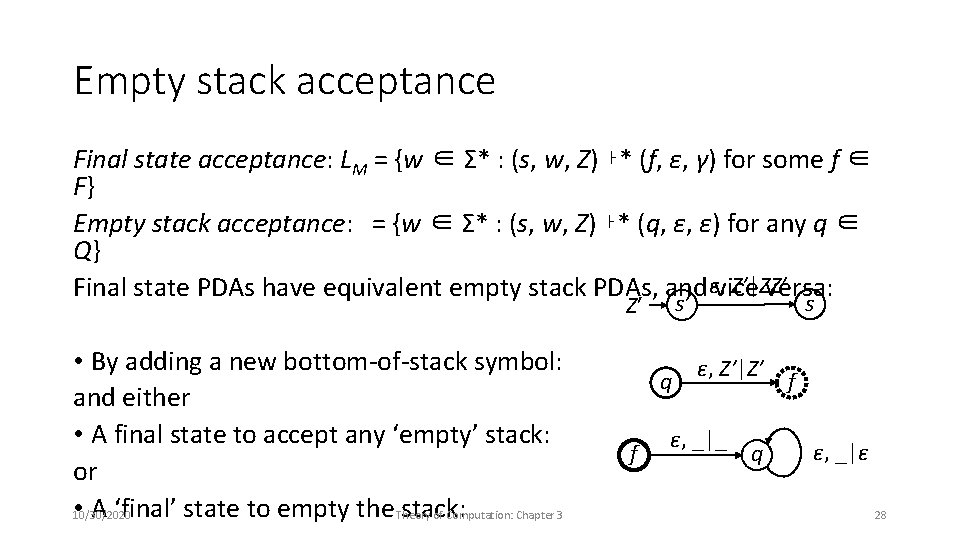

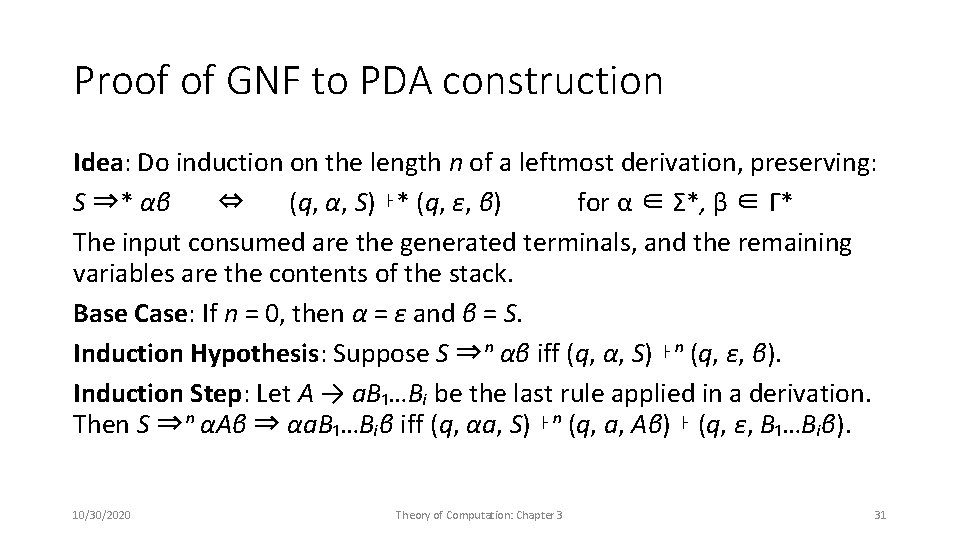

Empty stack acceptance Final state acceptance: LM = {w ∈ Σ* : (s, w, Z) ⊦* (f, ε, γ) for some f ∈ F} Empty stack acceptance: = {w ∈ Σ* : (s, w, Z) ⊦* (q, ε, ε) for any q ∈ Q} ε, Z′|ZZ′ Final state PDAs have equivalent empty stack PDAs, and vice versa: • By adding a new bottom-of-stack symbol: and either • A final state to accept any ‘empty’ stack: or • A ‘final’ state to empty the stack: 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 q f s s′ Z′ ε, Z′|Z′ ε, _|_ q f ε, _|ε 28

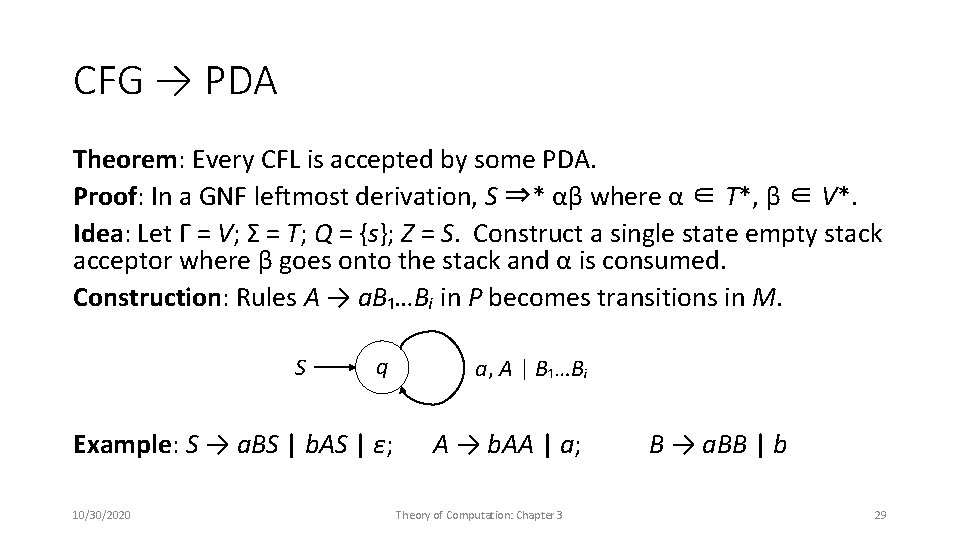

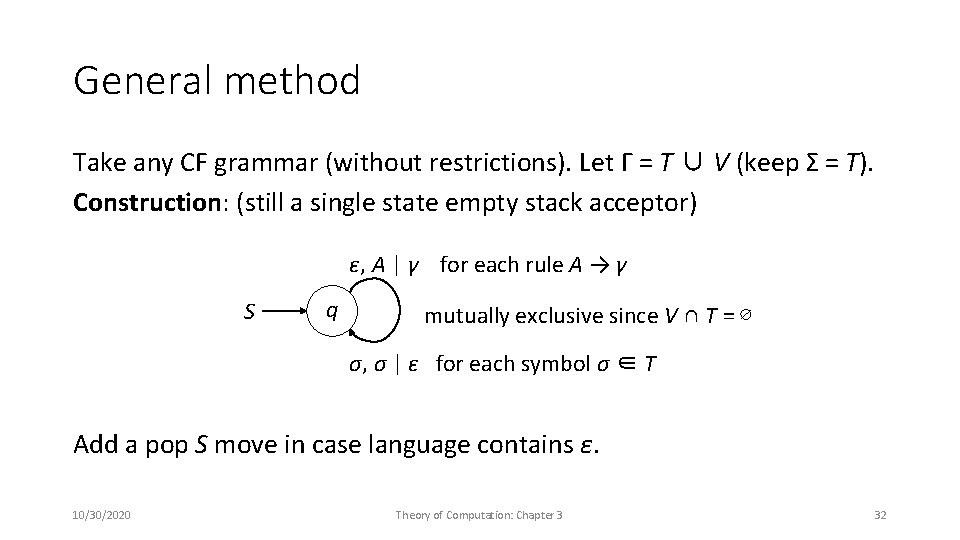

CFG → PDA Theorem: Every CFL is accepted by some PDA. Proof: In a GNF leftmost derivation, S ⇒* αβ where α ∈ T*, β ∈ V*. Idea: Let Γ = V; Σ = T; Q = {s}; Z = S. Construct a single state empty stack acceptor where β goes onto the stack and α is consumed. Construction: Rules A → a. B₁…Bᵢ in P becomes transitions in M. q a, A | B₁…Bᵢ Example: S → a. BS | b. AS | ε; A → b. AA | a; S 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 B → a. BB | b 29

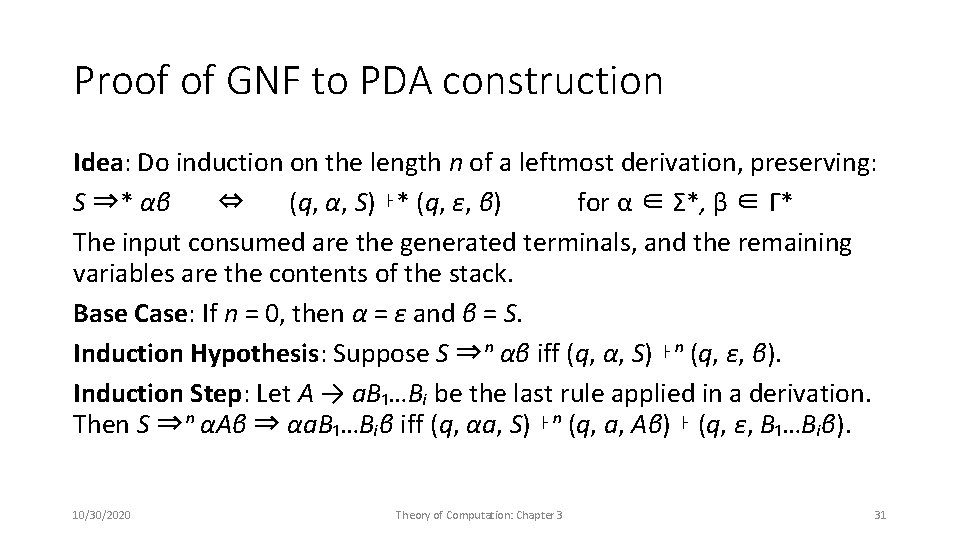

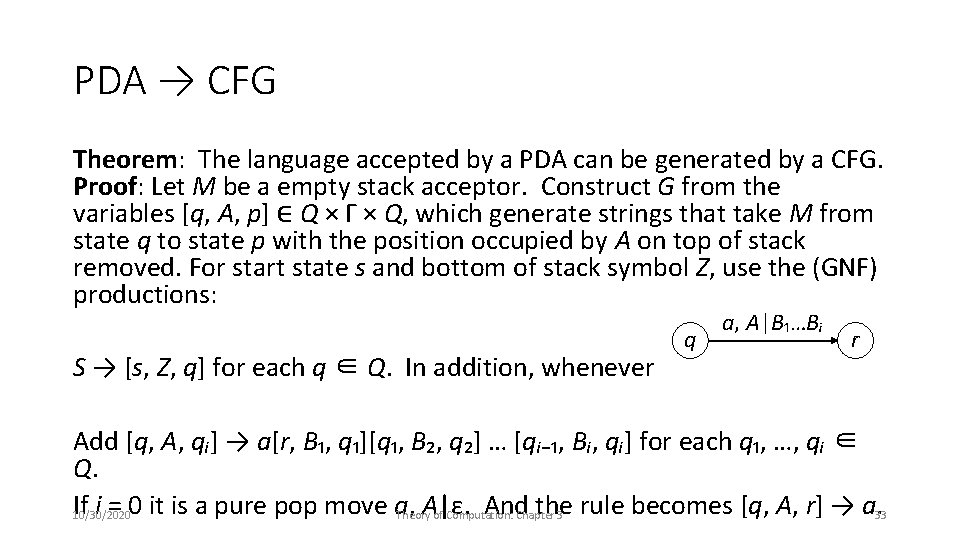

Proof of GNF to PDA construction Idea: Do induction on the length n of a leftmost derivation, preserving: S ⇒* αβ ⇔ (q, α, S) ⊦* (q, ε, β) for α ∈ Σ*, β ∈ Γ* The input consumed are the generated terminals, and the remaining variables are the contents of the stack. Base Case: If n = 0, then α = ε and β = S. Induction Hypothesis: Suppose S ⇒ⁿ αβ iff (q, α, S) ⊦ⁿ (q, ε, β). Induction Step: Let A → a. B₁…Bᵢ be the last rule applied in a derivation. Then S ⇒ⁿ αAβ ⇒ αa. B₁…Bᵢβ iff (q, αa, S) ⊦ⁿ (q, a, Aβ) ⊦ (q, ε, B₁…Bᵢβ). 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 31

General method Take any CF grammar (without restrictions). Let Γ = T ∪ V (keep Σ = T). Construction: (still a single state empty stack acceptor) ε, A | γ for each rule A → γ S q mutually exclusive since V ∩ T = ∅ σ, σ | ε for each symbol σ ∈ T Add a pop S move in case language contains ε. 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 32

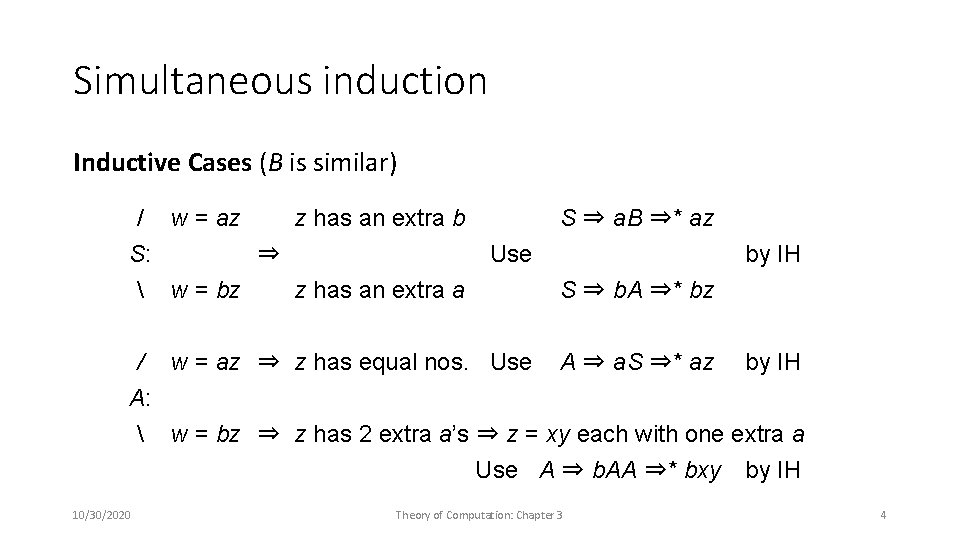

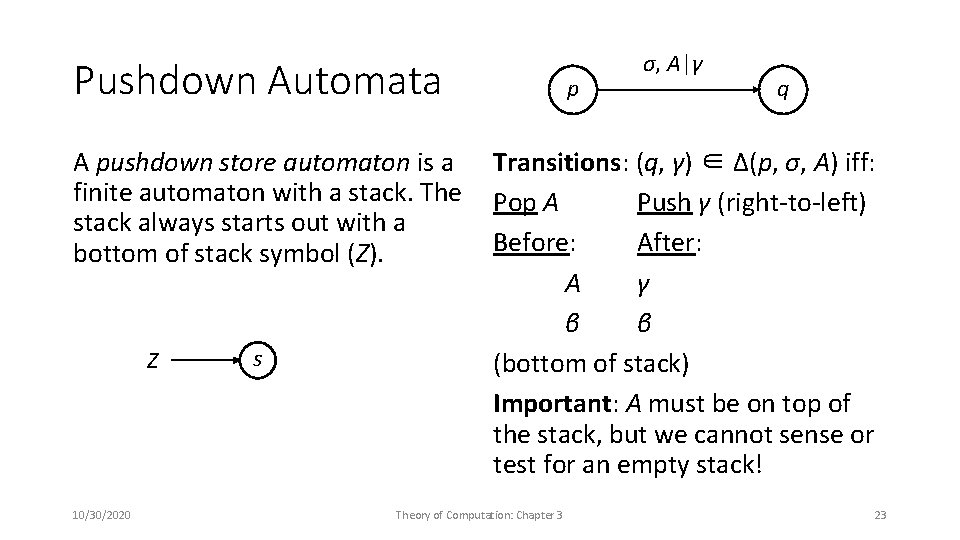

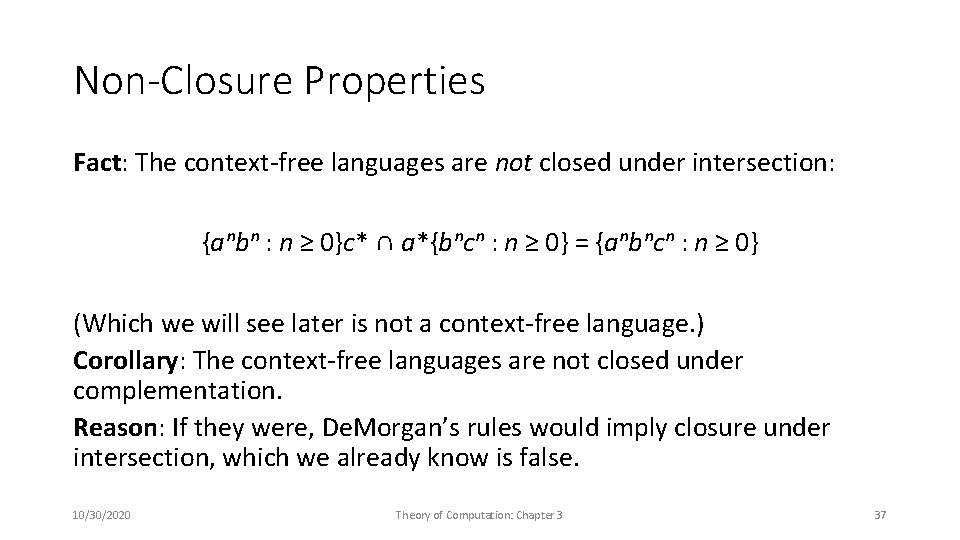

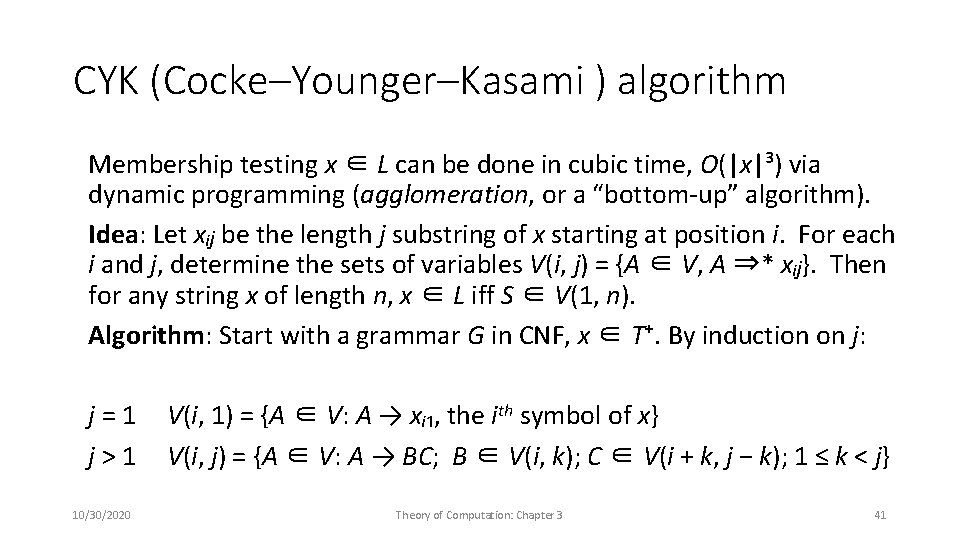

PDA → CFG Theorem: The language accepted by a PDA can be generated by a CFG. Proof: Let M be a empty stack acceptor. Construct G from the variables [q, A, p] ∈ Q × Γ × Q, which generate strings that take M from state q to state p with the position occupied by A on top of stack removed. For start state s and bottom of stack symbol Z, use the (GNF) productions: S → [s, Z, q] for each q ∈ Q. In addition, whenever q a, A|B₁…Bᵢ r Add [q, A, qᵢ] → a[r, B₁, q₁][q₁, B₂, q₂] … [qᵢ₋₁, Bᵢ, qᵢ] for each q₁, …, qᵢ ∈ Q. If i = 0 it is a pure pop move a, A|ε. And the rule becomes [q, A, r] → a. 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 33

![Conversion template w Aε q p Idea q A p w iff That Conversion template w, A|ε q p Idea: [q, A, p] ⇒* w iff That](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/29f1389ef2e4c2e4aa43cf0eed3afb5d/image-33.jpg)

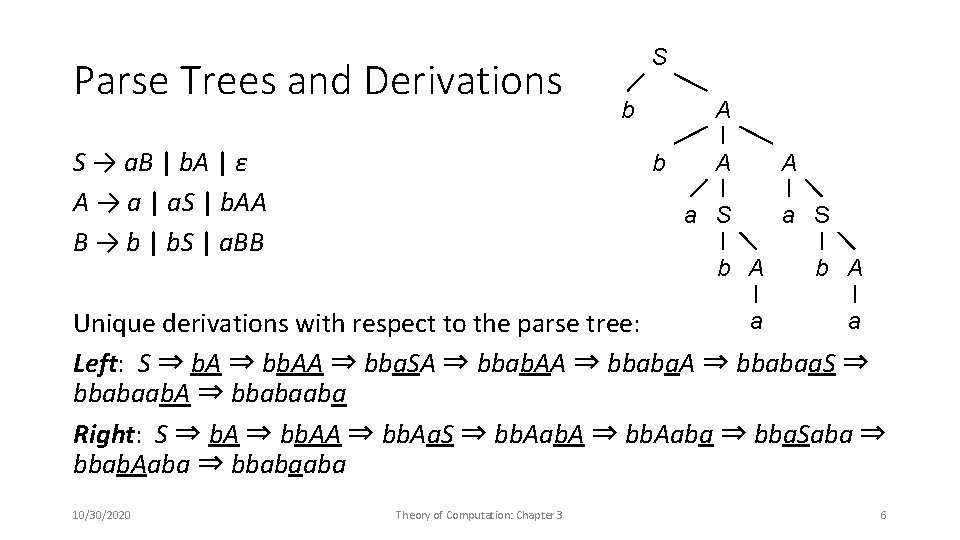

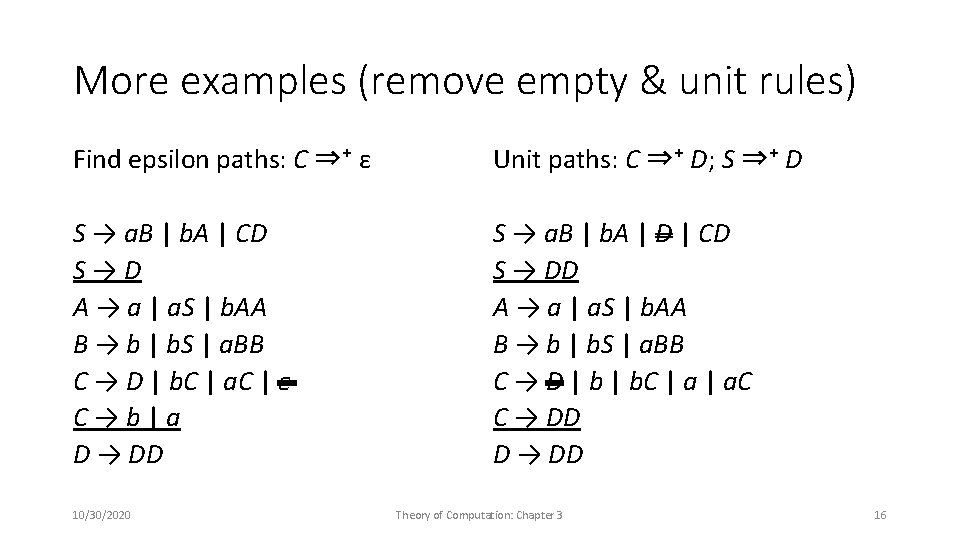

Conversion template w, A|ε q p Idea: [q, A, p] ⇒* w iff That is, the net effect is to consume w and erase A from stack: it diminishes by 1 and does not go below that point anytime previously. q a, A|B₁…Bᵢ unknown r qᵢ states B₁. . . A Bᵢ …… [q, A, qᵢ] → a[r, B₁, q₁][q₁, B₂, q₂] … [qᵢ₋₁, Bᵢ, qᵢ] If i = 0, this becomes [q, A, r] → a. 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 q r p w 34

![Example S S q S f a AAA a Bε a SAS ε Example: S S → [q, S, f] a, A|AA a, B|ε a, S|AS ε,](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/29f1389ef2e4c2e4aa43cf0eed3afb5d/image-34.jpg)

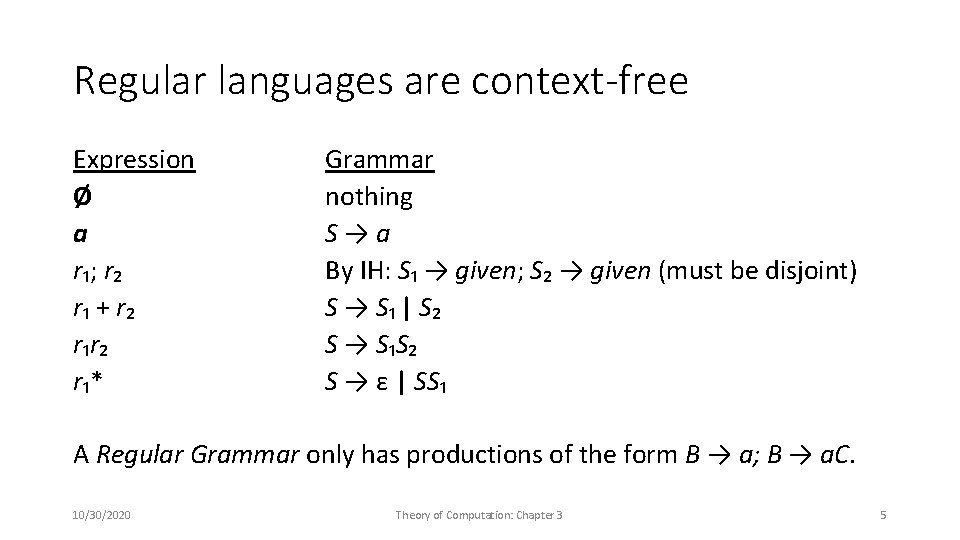

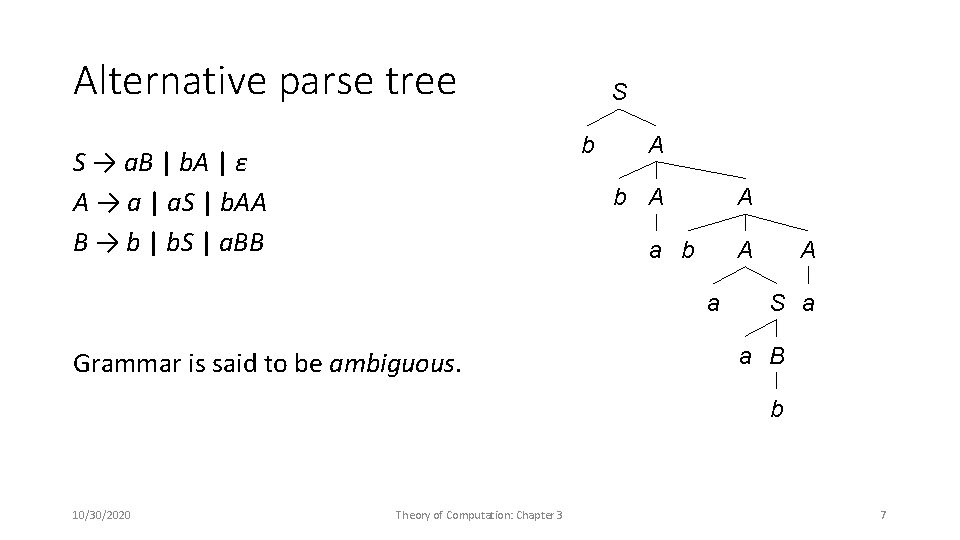

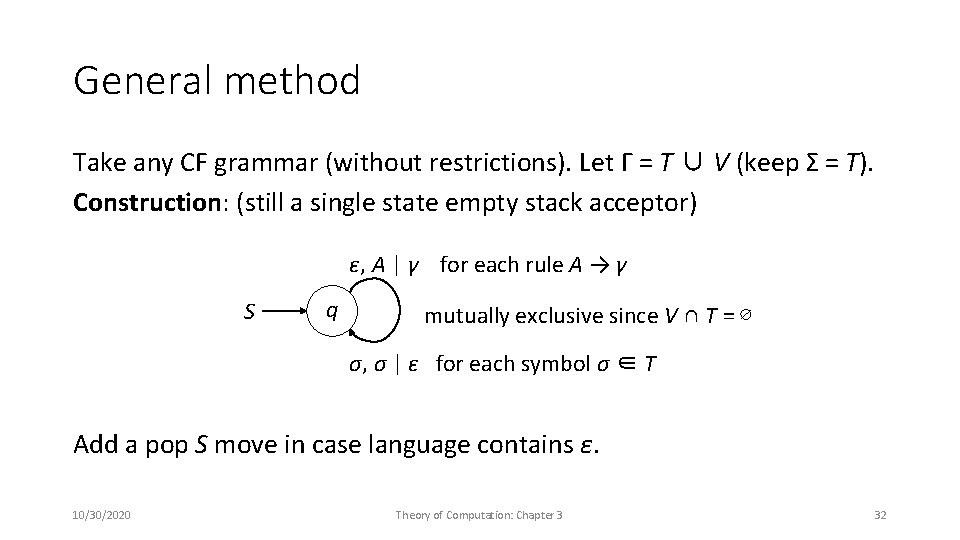

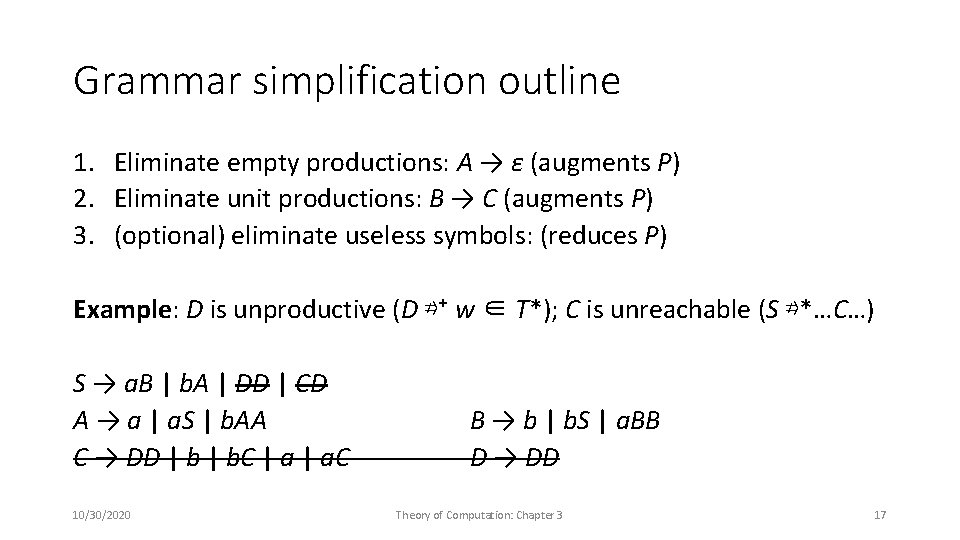

Example: S S → [q, S, f] a, A|AA a, B|ε a, S|AS ε, S|ε q b, A|ε b, B|BB b, S|BS [q, S, f] → a [q, A, q] [q, S, f] → a [q, A, f] [f, S, f] → b [q, B, q] [q, S, f] → b [q, B, f] [f, S, f] → ε [f, S, f] → (nothing) 10/30/2020 f [q, A, q]→ a[q, A, q] → a[q, A, f][f, A, q] → b [q, B, q]→ b[q, B, q] → b[q, B, f][f, B, q] → a [f, _, q] → (nothing) Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 35

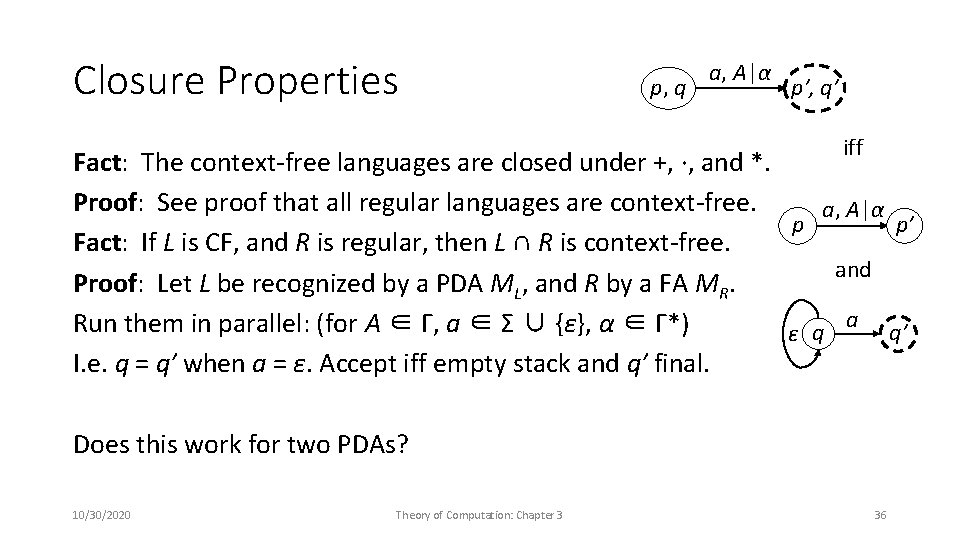

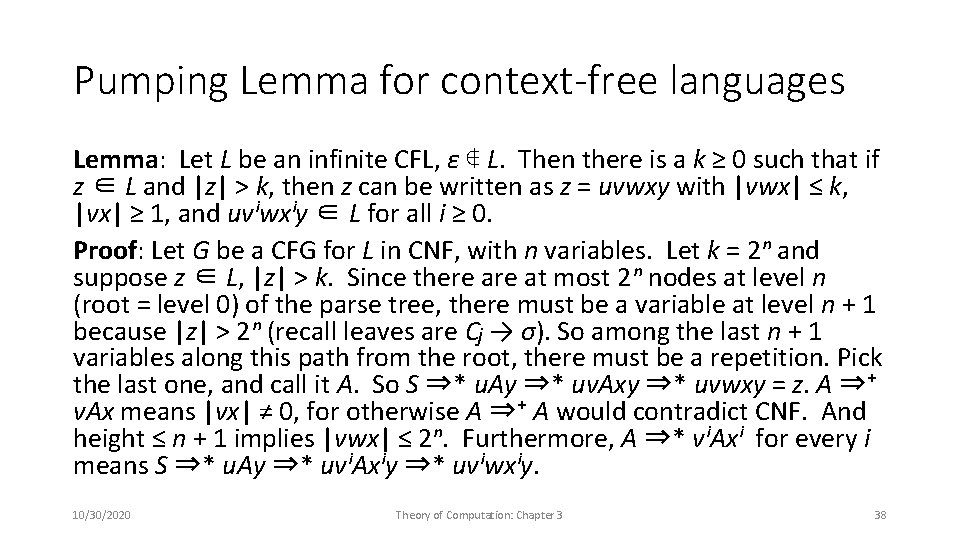

Closure Properties p, q a, A|α p′, q′ iff Fact: The context-free languages are closed under +, ·, and *. Proof: See proof that all regular languages are context-free. a, A|α p′ p Fact: If L is CF, and R is regular, then L ∩ R is context-free. and Proof: Let L be recognized by a PDA ML, and R by a FA MR. a Run them in parallel: (for A ∈ Γ, a ∈ Σ ∪ {ε}, α ∈ Γ*) q′ ε q I. e. q = q′ when a = ε. Accept iff empty stack and q′ final. Does this work for two PDAs? 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 36

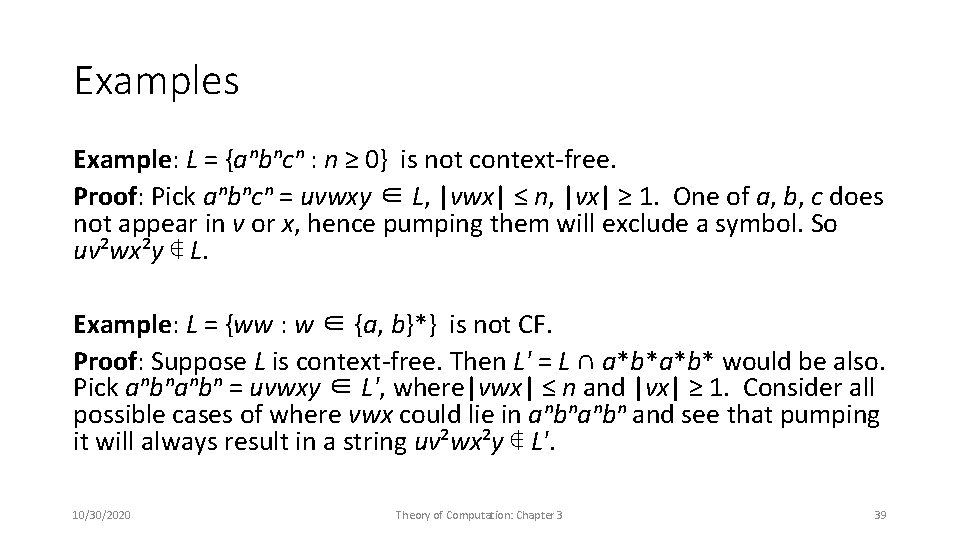

Non-Closure Properties Fact: The context-free languages are not closed under intersection: {aⁿbⁿ : n ≥ 0}c* ∩ a*{bⁿcⁿ : n ≥ 0} = {aⁿbⁿcⁿ : n ≥ 0} (Which we will see later is not a context-free language. ) Corollary: The context-free languages are not closed under complementation. Reason: If they were, De. Morgan’s rules would imply closure under intersection, which we already know is false. 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 37

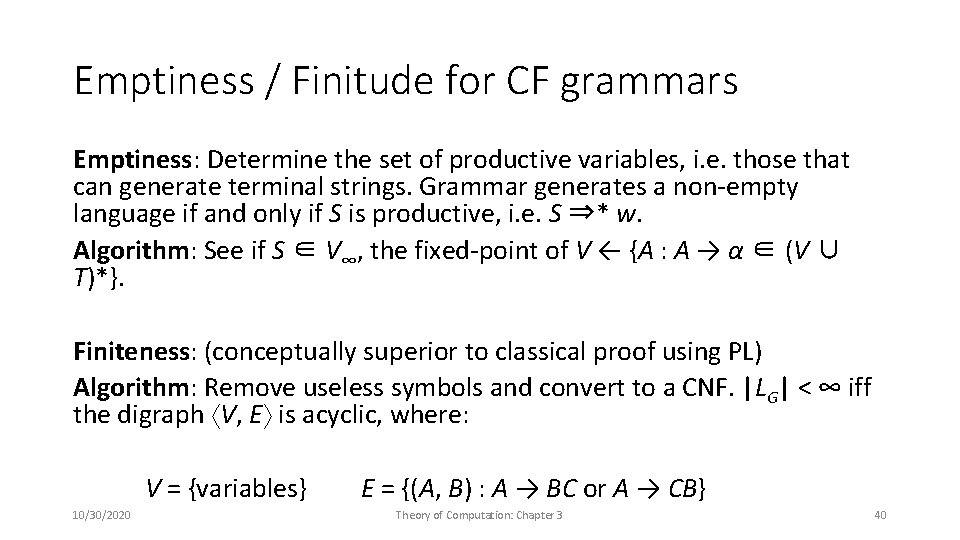

Pumping Lemma for context-free languages Lemma: Let L be an infinite CFL, ε ∉ L. Then there is a k ≥ 0 such that if z ∈ L and |z| > k, then z can be written as z = uvwxy with |vwx| ≤ k, |vx| ≥ 1, and uvⁱwxⁱy ∈ L for all i ≥ 0. Proof: Let G be a CFG for L in CNF, with n variables. Let k = 2ⁿ and suppose z ∈ L, |z| > k. Since there at most 2ⁿ nodes at level n (root = level 0) of the parse tree, there must be a variable at level n + 1 because |z| > 2ⁿ (recall leaves are Cⱼ → σ). So among the last n + 1 variables along this path from the root, there must be a repetition. Pick the last one, and call it A. So S ⇒* u. Ay ⇒* uv. Axy ⇒* uvwxy = z. A ⇒⁺ v. Ax means |vx| ≠ 0, for otherwise A ⇒⁺ A would contradict CNF. And height ≤ n + 1 implies |vwx| ≤ 2ⁿ. Furthermore, A ⇒* vⁱAxⁱ for every i means S ⇒* u. Ay ⇒* uvⁱAxⁱy ⇒* uvⁱwxⁱy. 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 38

Examples Example: L = {aⁿbⁿcⁿ : n ≥ 0} is not context-free. Proof: Pick aⁿbⁿcⁿ = uvwxy ∈ L, |vwx| ≤ n, |vx| ≥ 1. One of a, b, c does not appear in v or x, hence pumping them will exclude a symbol. So uv²wx²y ∉ L. Example: L = {ww : w ∈ {a, b}*} is not CF. Proof: Suppose L is context-free. Then L' = L ∩ a*b* would be also. Pick aⁿbⁿ = uvwxy ∈ L', where|vwx| ≤ n and |vx| ≥ 1. Consider all possible cases of where vwx could lie in aⁿbⁿ and see that pumping it will always result in a string uv²wx²y ∉ L'. 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 39

Emptiness / Finitude for CF grammars Emptiness: Determine the set of productive variables, i. e. those that can generate terminal strings. Grammar generates a non-empty language if and only if S is productive, i. e. S ⇒* w. Algorithm: See if S ∈ V∞, the fixed-point of V ← {A : A → α ∈ (V ∪ T)*}. Finiteness: (conceptually superior to classical proof using PL) Algorithm: Remove useless symbols and convert to a CNF. |LG| < ∞ iff the digraph V, E is acyclic, where: V = {variables} 10/30/2020 E = {(A, B) : A → BC or A → CB} Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 40

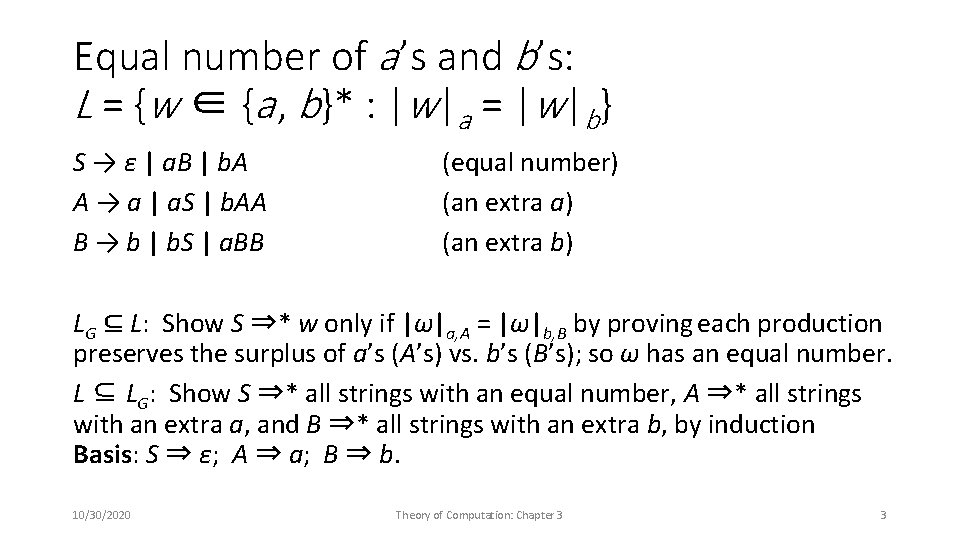

CYK (Cocke–Younger–Kasami ) algorithm Membership testing x ∈ L can be done in cubic time, O(|x|³) via dynamic programming (agglomeration, or a “bottom-up” algorithm). Idea: Let xᵢⱼ be the length j substring of x starting at position i. For each i and j, determine the sets of variables V(i, j) = {A ∈ V, A ⇒* xᵢⱼ}. Then for any string x of length n, x ∈ L iff S ∈ V(1, n). Algorithm: Start with a grammar G in CNF, x ∈ T⁺. By induction on j: j = 1 V(i, 1) = {A ∈ V: A → xᵢ₁, the ith symbol of x} j > 1 V(i, j) = {A ∈ V: A → BC; B ∈ V(i, k); C ∈ V(i + k, j − k); 1 ≤ k < j} 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 41

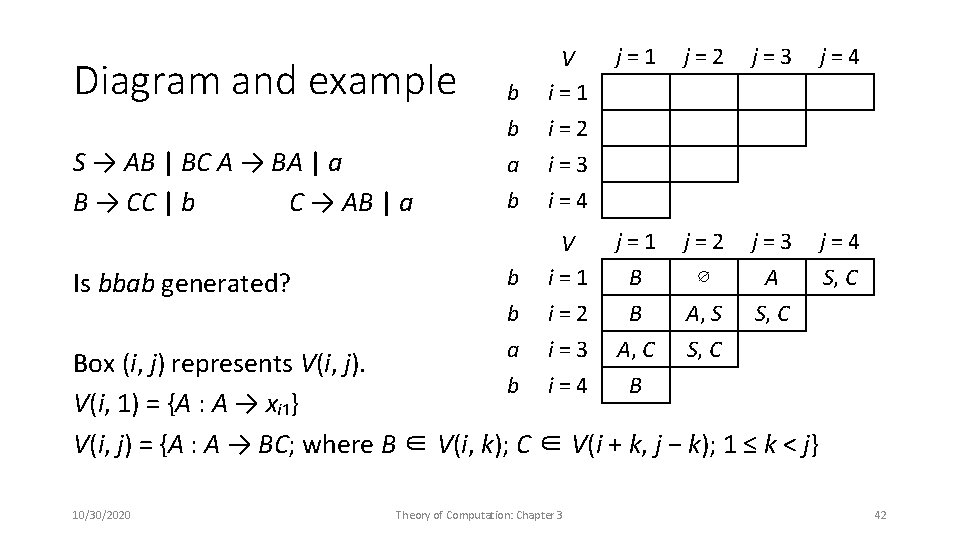

Diagram and example S → AB | BC A → BA | a B → CC | b C → AB | a Is bbab generated? b b a V i = 1 i = 2 i = 3 b i = 4 b b a b V i = 1 i = 2 i = 3 i = 4 j = 1 j = 2 j = 3 j = 4 j = 1 B B A, C B j = 2 ∅ A, S S, C j = 3 A S, C j = 4 S, C Box (i, j) represents V(i, j). V(i, 1) = {A : A → xᵢ₁} V(i, j) = {A : A → BC; where B ∈ V(i, k); C ∈ V(i + k, j − k); 1 ≤ k < j} 10/30/2020 Theory of Computation: Chapter 3 42