CHAPTER 3 ATOMIC ELECTRONIC STRUCTURE ADVANCED CHEMISTRY Purpose

- Slides: 38

CHAPTER 3 : ATOMIC & ELECTRONIC STRUCTURE ADVANCED CHEMISTRY

Purpose � Know the nature of light. � Be able to predict the quantum number for each electrons. � Learn how to write the electron configuration. � To be able to explain the positions of elements in the periodic table.

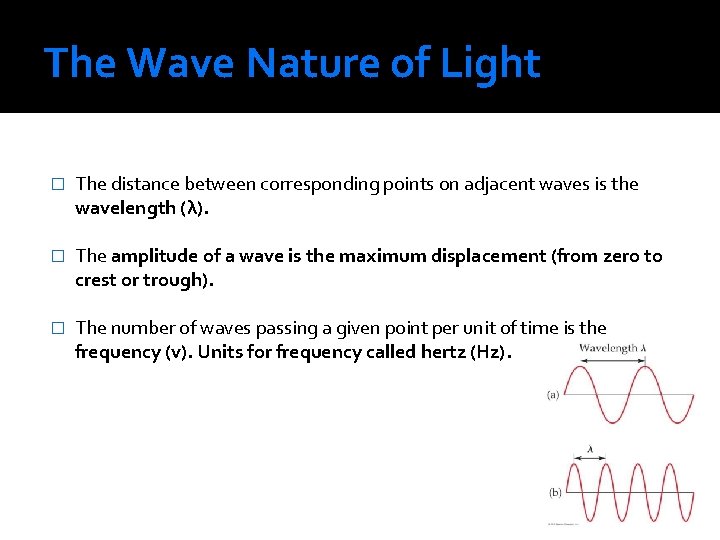

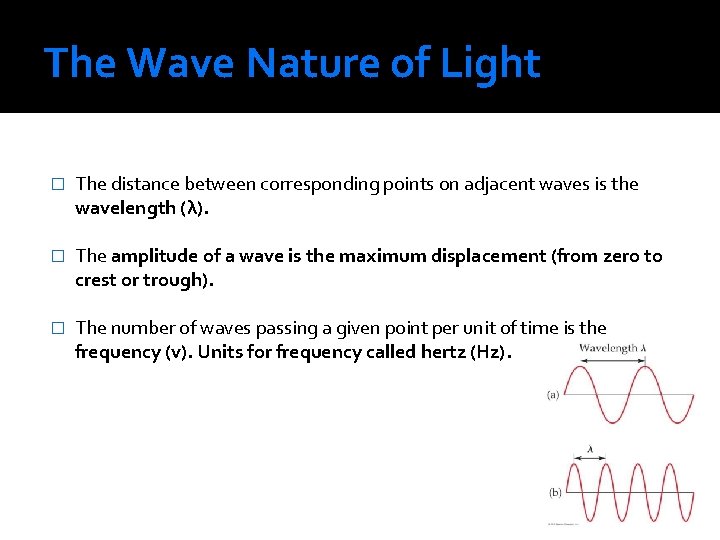

The Wave Nature of Light � The distance between corresponding points on adjacent waves is the wavelength (λ). � The amplitude of a wave is the maximum displacement (from zero to crest or trough). � The number of waves passing a given point per unit of time is the frequency (v). Units for frequency called hertz (Hz).

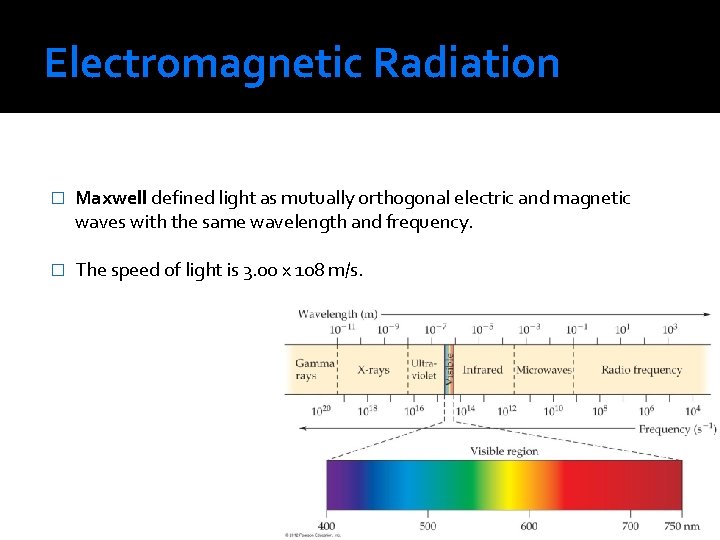

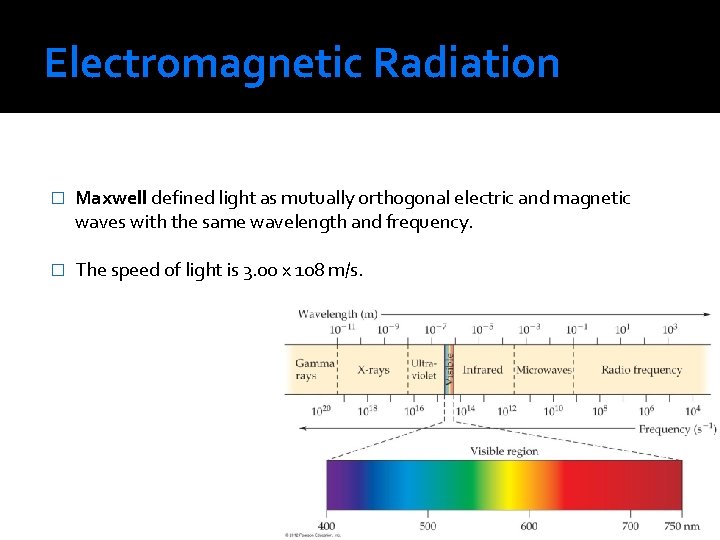

Electromagnetic Radiation � Maxwell defined light as mutually orthogonal electric and magnetic waves with the same wavelength and frequency. � The speed of light is 3. 00 x 108 m/s.

Quantized Energy and Photons � Max Planck explained the phenomena of energy absorption and emission by the concept that energy is comprised of discrete units, which he called quanta. � Frequency is directly related to energy by Planck’s constant (h) which is 6. 626 x 10 -34 j. s. � Therefore, if one knows the wavelength of light, one can calculate the energy in one photon, or packet, of that light: E = hv or E = hc/λ

� Albert Einstein in 1905, used Planck’s quantum theory to explain the photoelectric effect. � In the photoelectric effect, electrons are ejected when light shines on a metal. � A certain amount of energy work function is needed to overcome the attraction holding them in a metal. � Threshold energy, termed the binding energy (BE) was necessary to dislodge the electron from the cathode before it would migrate to the anode. � Electrons can only be dislodged if photons have greater energy than the work function of a particular metal.

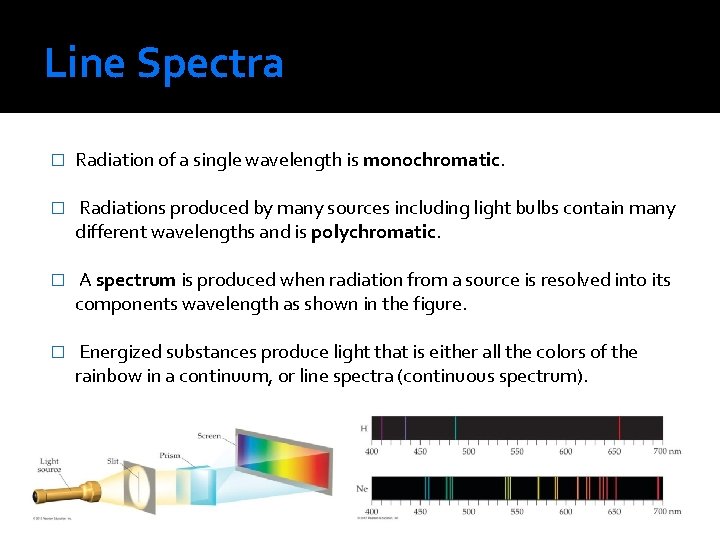

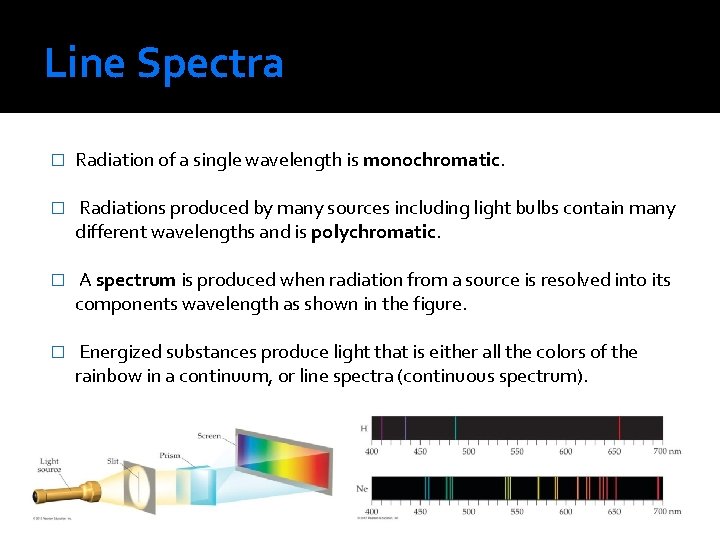

Line Spectra � Radiation of a single wavelength is monochromatic. � Radiations produced by many sources including light bulbs contain many different wavelengths and is polychromatic. � A spectrum is produced when radiation from a source is resolved into its components wavelength as shown in the figure. � Energized substances produce light that is either all the colors of the rainbow in a continuum, or line spectra (continuous spectrum).

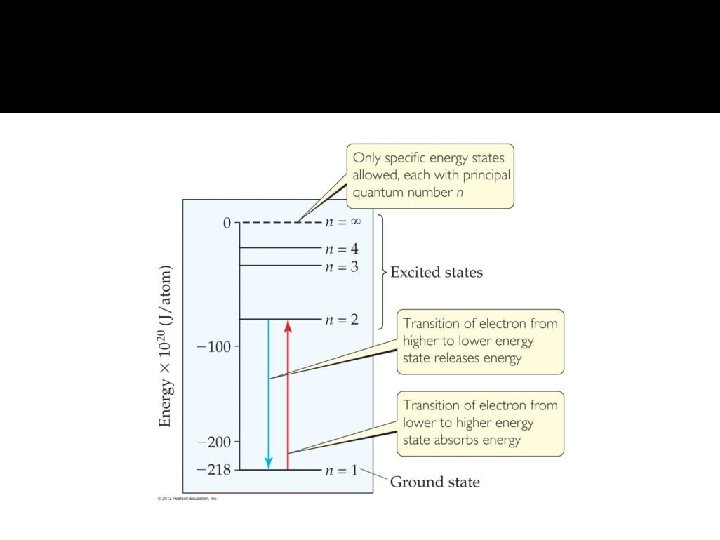

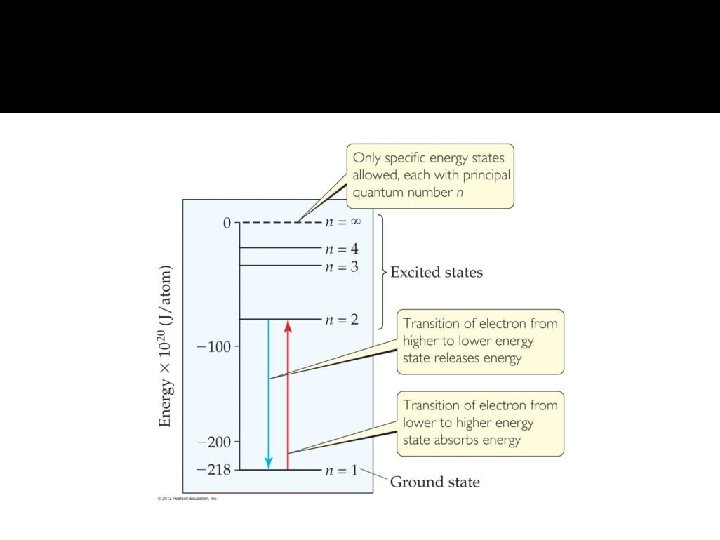

Bohr Model � When the electron has its lowest possible energy, the atom is in its ground state. � Energy is absorbed when an electron is excited to a higher energy level and an atom goes to an excited state. � When an electron is dropped from a higher level to a lower, it would emit a photon equal to the difference in energy between the levels. In order for an electron to move to a higher state, energy needs to be absorbed.

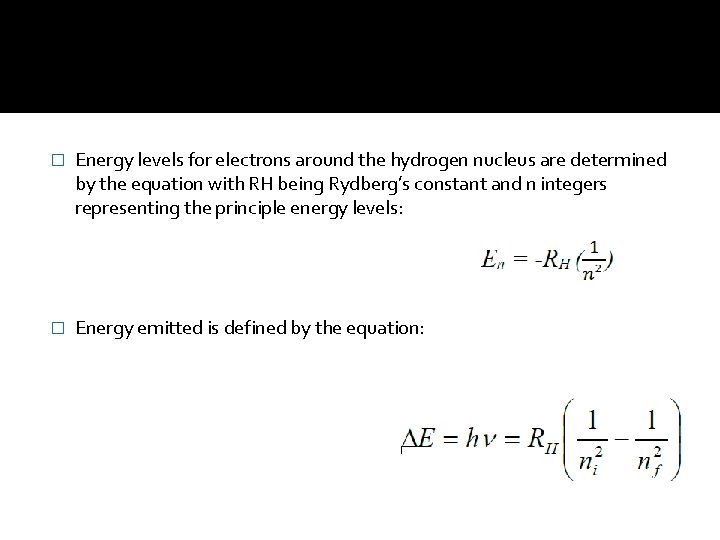

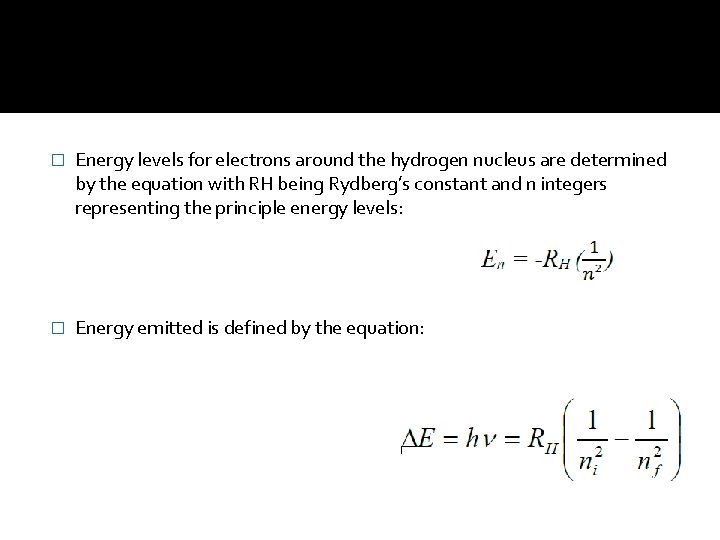

� Energy levels for electrons around the hydrogen nucleus are determined by the equation with RH being Rydberg’s constant and n integers representing the principle energy levels: � Energy emitted is defined by the equation:

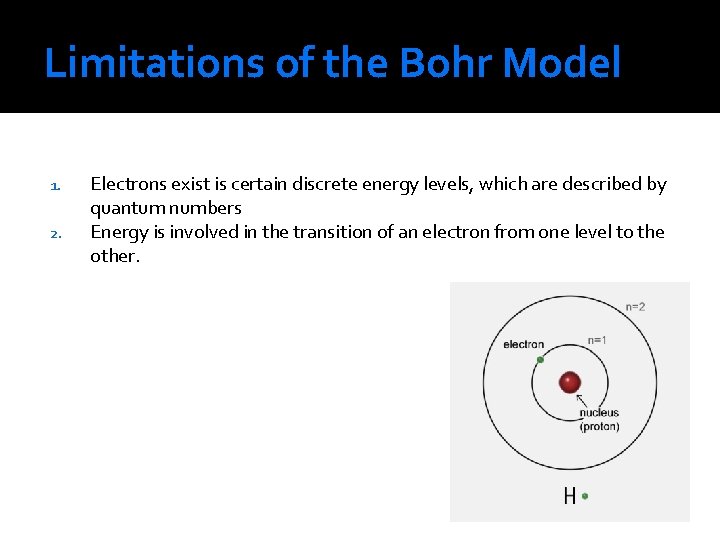

Limitations of the Bohr Model 1. 2. Electrons exist is certain discrete energy levels, which are described by quantum numbers Energy is involved in the transition of an electron from one level to the other.

The Wave Behavior of Matter � Louis de Broglie posited that if light can have material properties, matter should exhibit wave properties. � He demonstrated that the relationship between mass and wavelength was λ = h/mv. � All moving objects have a wavelike behavior. For larger masses, the wavelength is unnoticeable because of large mass.

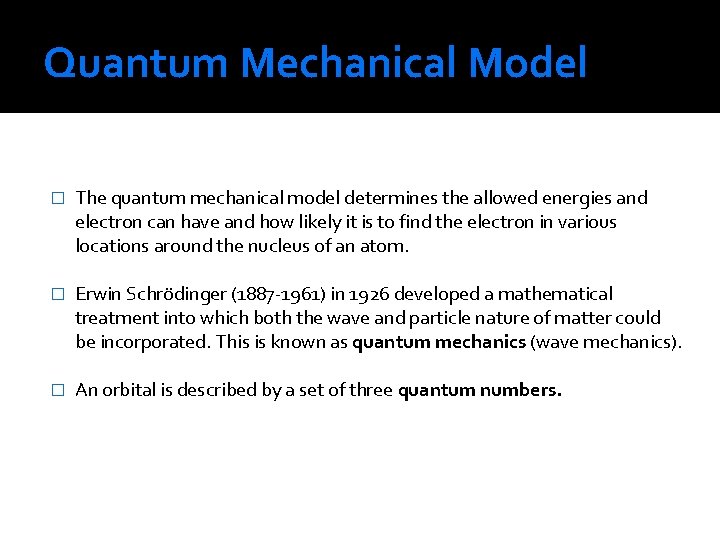

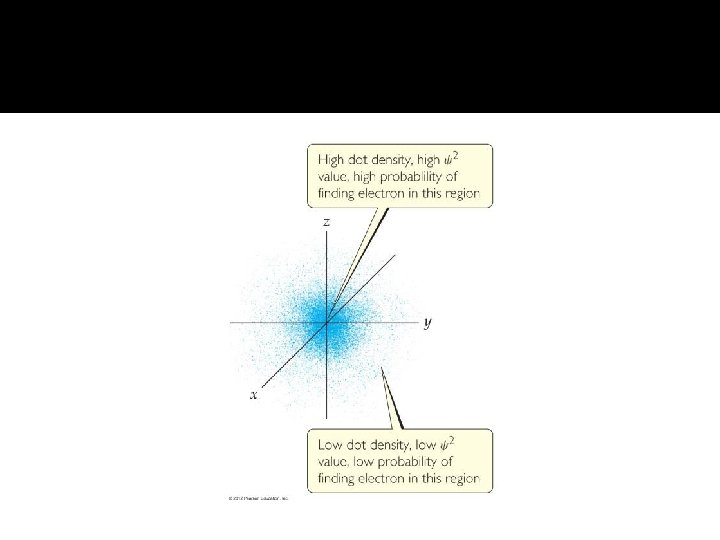

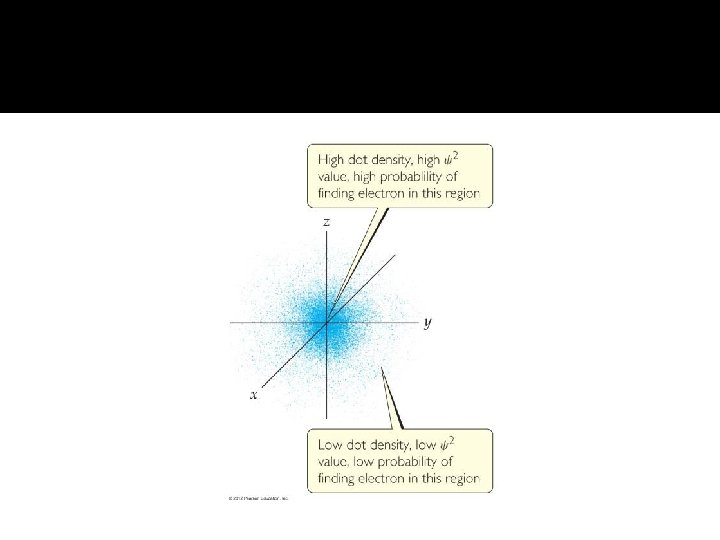

Quantum Mechanical Model � The quantum mechanical model determines the allowed energies and electron can have and how likely it is to find the electron in various locations around the nucleus of an atom. � Erwin Schrödinger (1887 -1961) in 1926 developed a mathematical treatment into which both the wave and particle nature of matter could be incorporated. This is known as quantum mechanics (wave mechanics). � An orbital is described by a set of three quantum numbers.

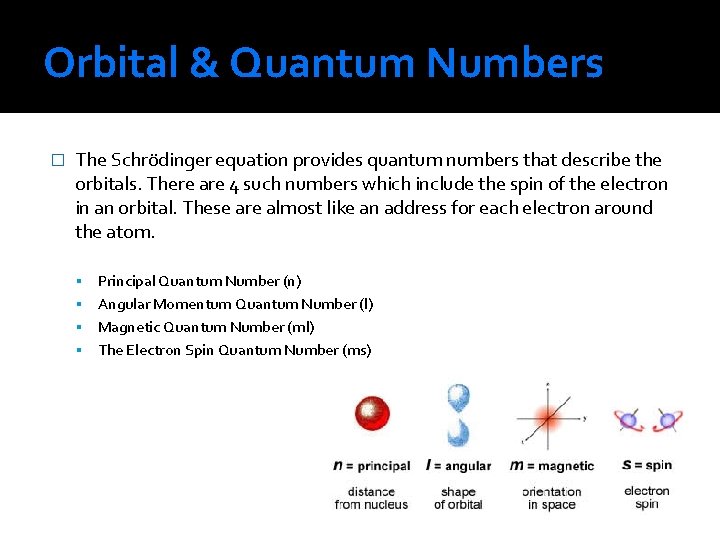

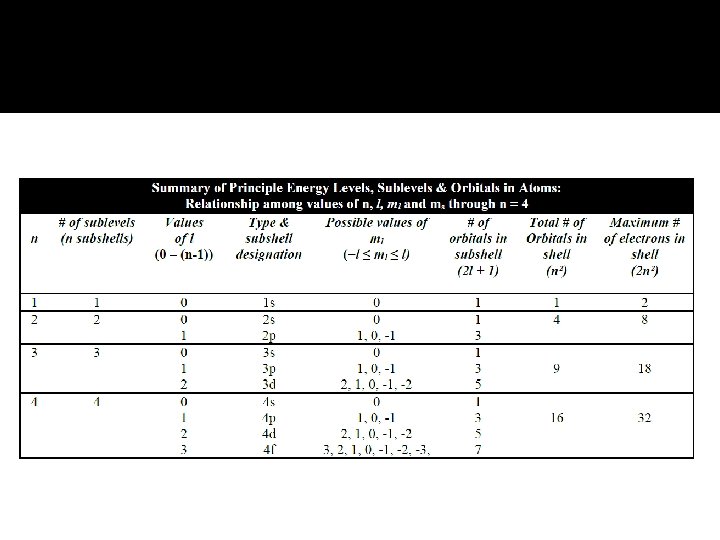

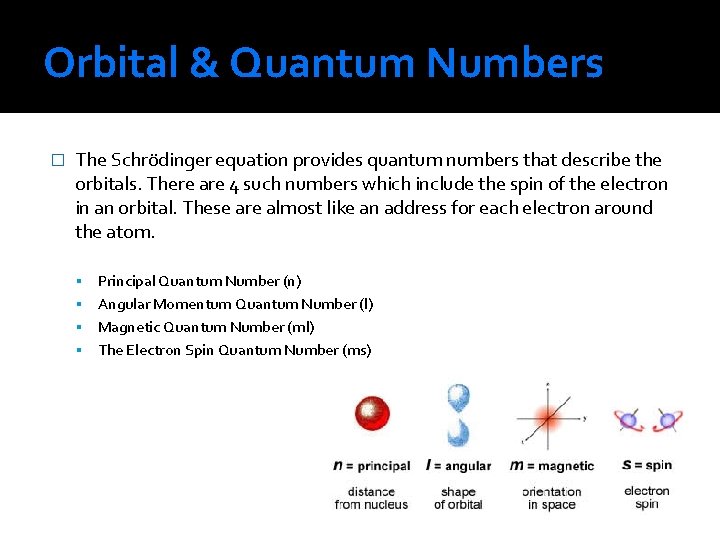

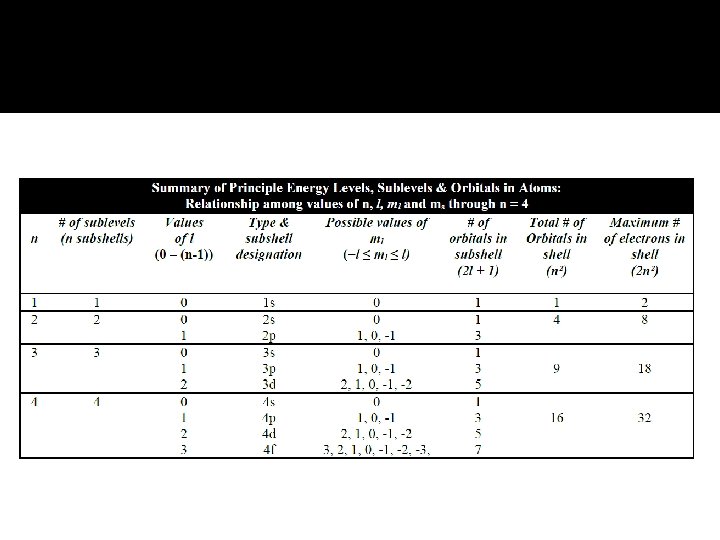

Orbital & Quantum Numbers � The Schrödinger equation provides quantum numbers that describe the orbitals. There are 4 such numbers which include the spin of the electron in an orbital. These are almost like an address for each electron around the atom. Principal Quantum Number (n) Angular Momentum Quantum Number (l) Magnetic Quantum Number (ml) The Electron Spin Quantum Number (ms)

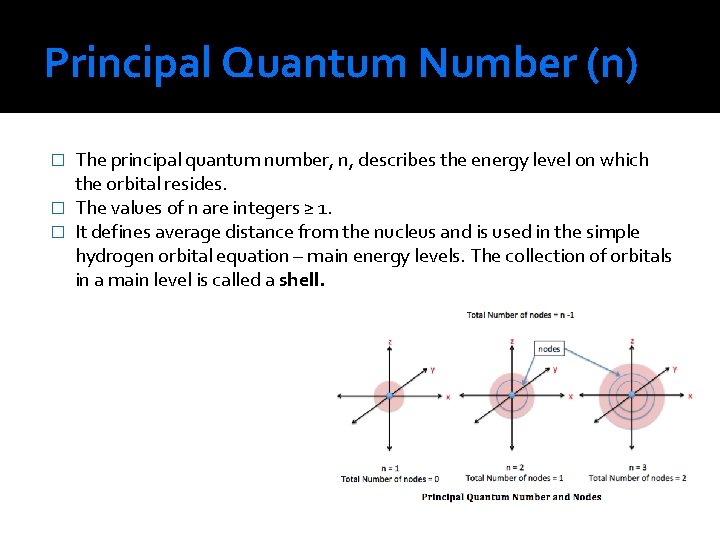

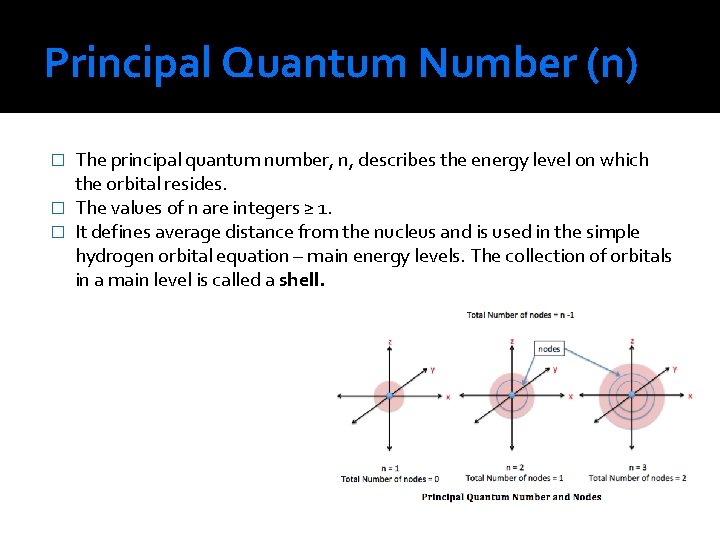

Principal Quantum Number (n) The principal quantum number, n, describes the energy level on which the orbital resides. � The values of n are integers ≥ 1. � It defines average distance from the nucleus and is used in the simple hydrogen orbital equation – main energy levels. The collection of orbitals in a main level is called a shell. �

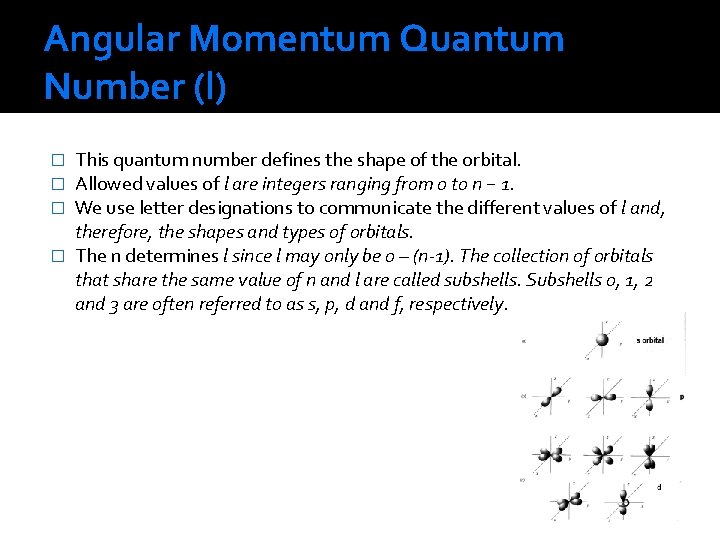

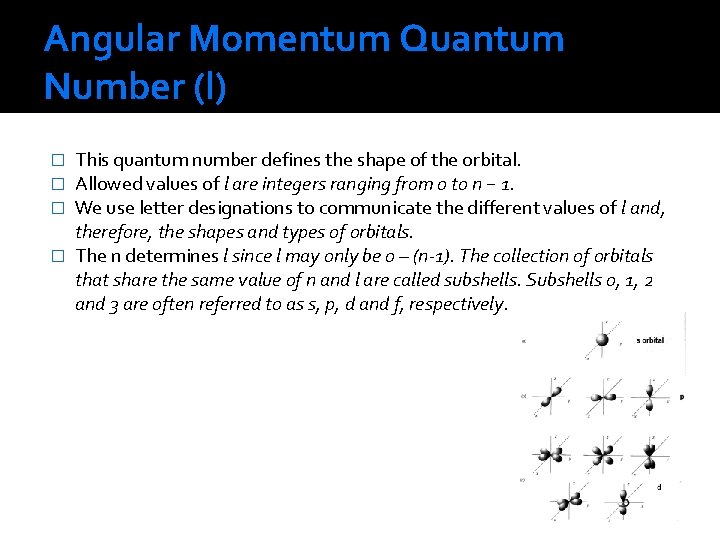

Angular Momentum Quantum Number (l) This quantum number defines the shape of the orbital. Allowed values of l are integers ranging from 0 to n − 1. We use letter designations to communicate the different values of l and, therefore, the shapes and types of orbitals. � The n determines l since l may only be 0 – (n-1). The collection of orbitals that share the same value of n and l are called subshells. Subshells 0, 1, 2 and 3 are often referred to as s, p, d and f, respectively. � � �

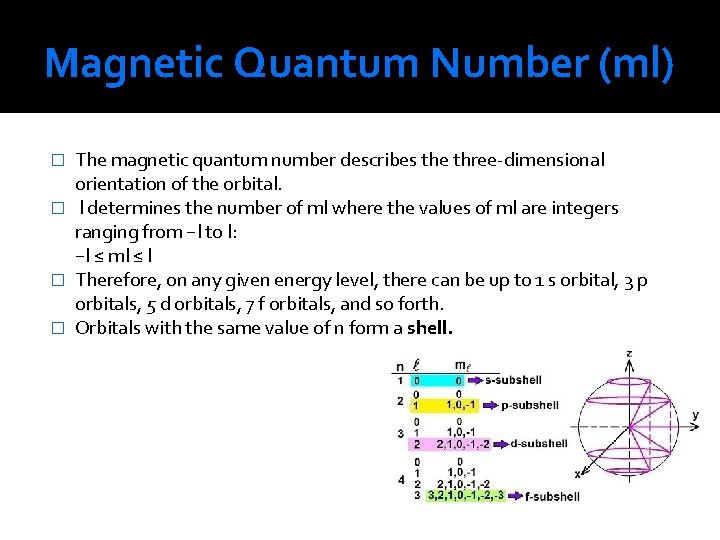

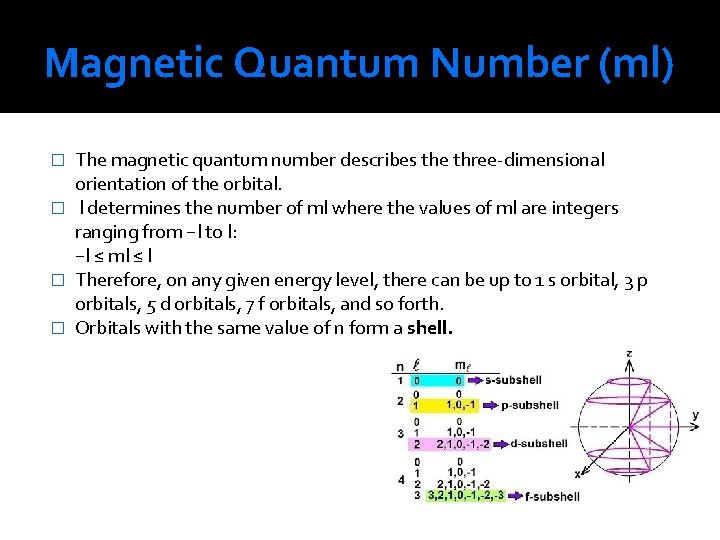

Magnetic Quantum Number (ml) The magnetic quantum number describes the three-dimensional orientation of the orbital. � l determines the number of ml where the values of ml are integers ranging from −l to l: −l ≤ ml ≤ l � Therefore, on any given energy level, there can be up to 1 s orbital, 3 p orbitals, 5 d orbitals, 7 f orbitals, and so forth. � Orbitals with the same value of n form a shell. �

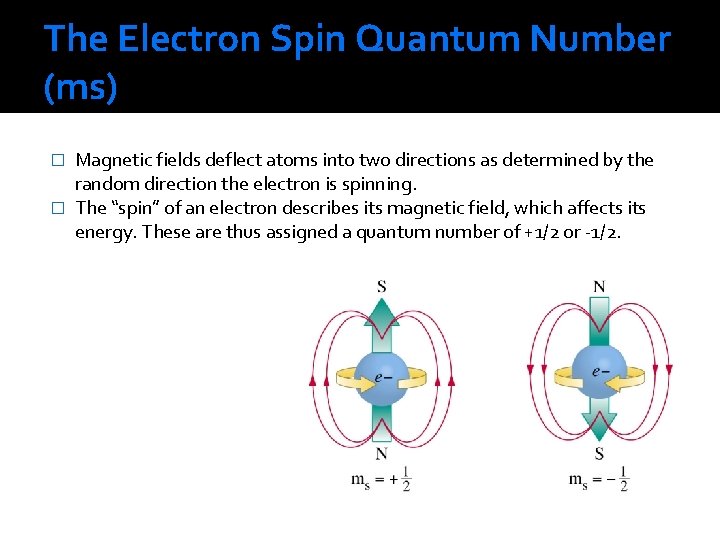

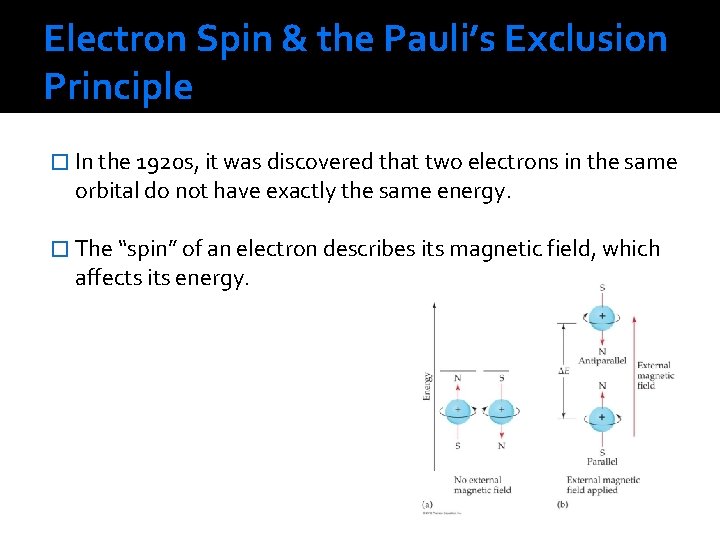

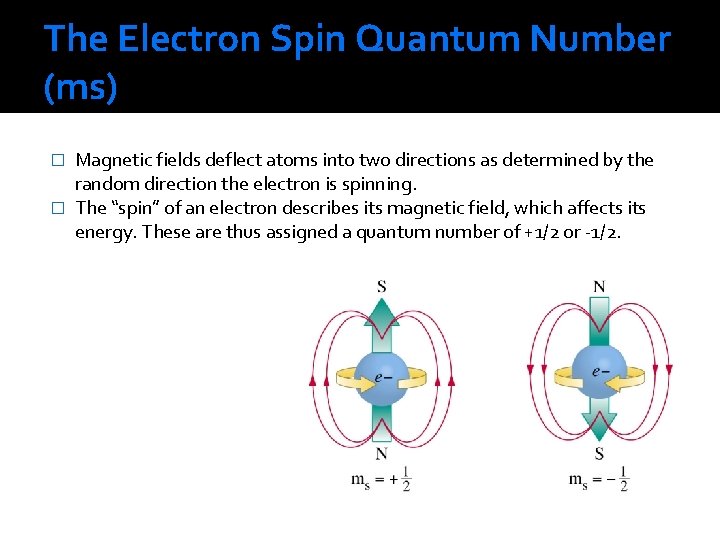

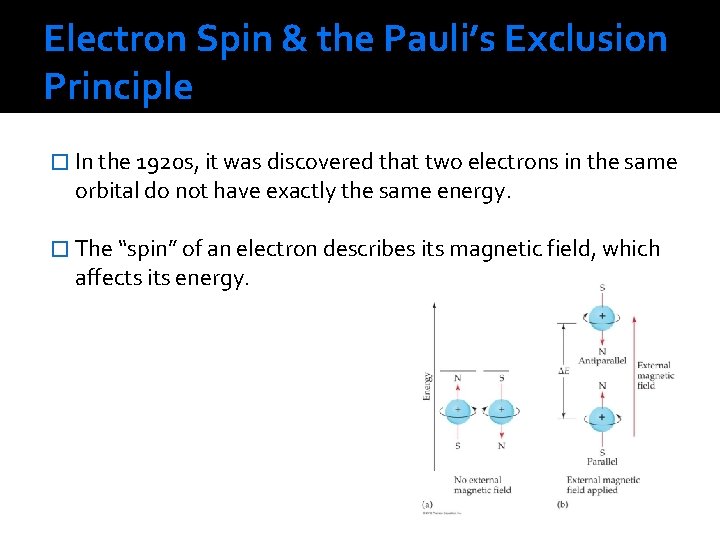

The Electron Spin Quantum Number (ms) Magnetic fields deflect atoms into two directions as determined by the random direction the electron is spinning. � The “spin” of an electron describes its magnetic field, which affects its energy. These are thus assigned a quantum number of +1/2 or -1/2. �

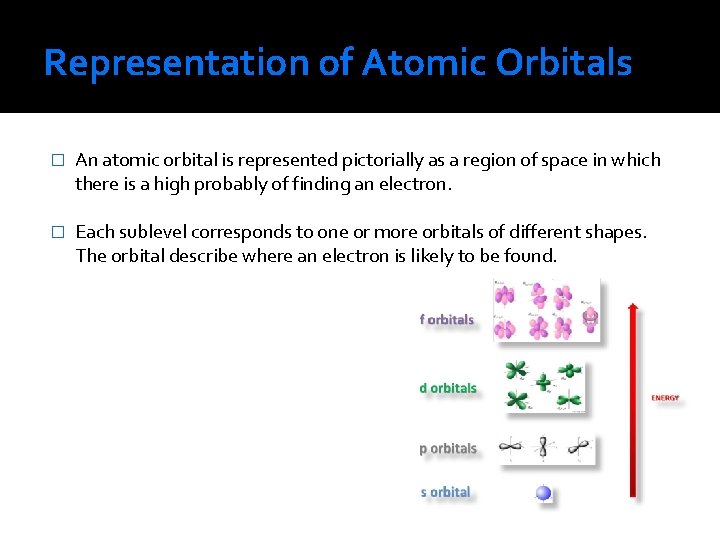

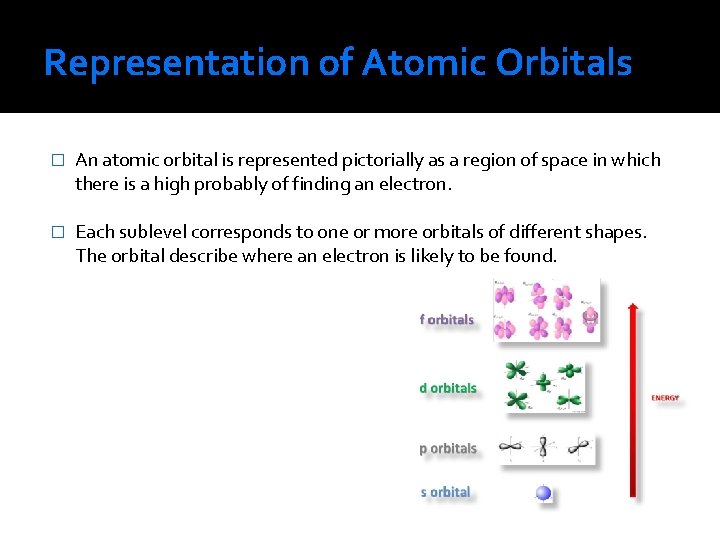

Representation of Atomic Orbitals � An atomic orbital is represented pictorially as a region of space in which there is a high probably of finding an electron. � Each sublevel corresponds to one or more orbitals of different shapes. The orbital describe where an electron is likely to be found.

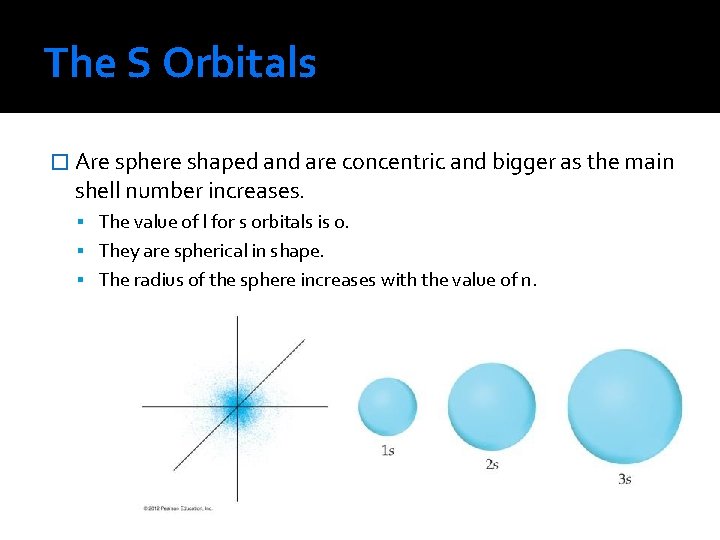

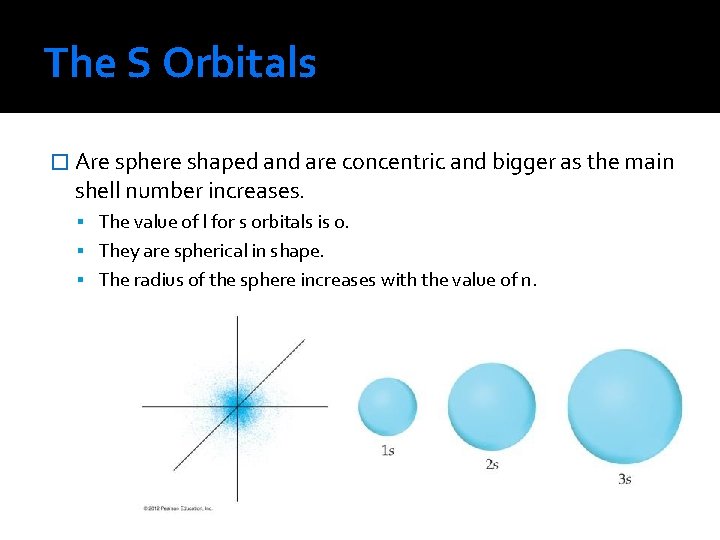

The S Orbitals � Are sphere shaped and are concentric and bigger as the main shell number increases. The value of l for s orbitals is 0. They are spherical in shape. The radius of the sphere increases with the value of n.

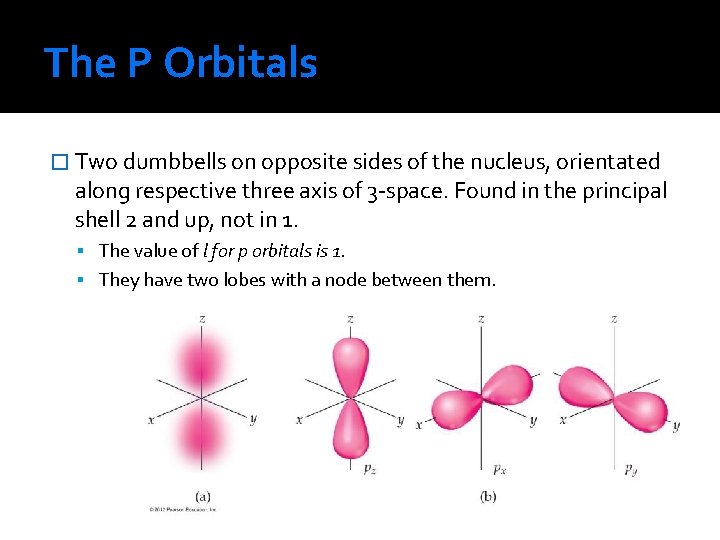

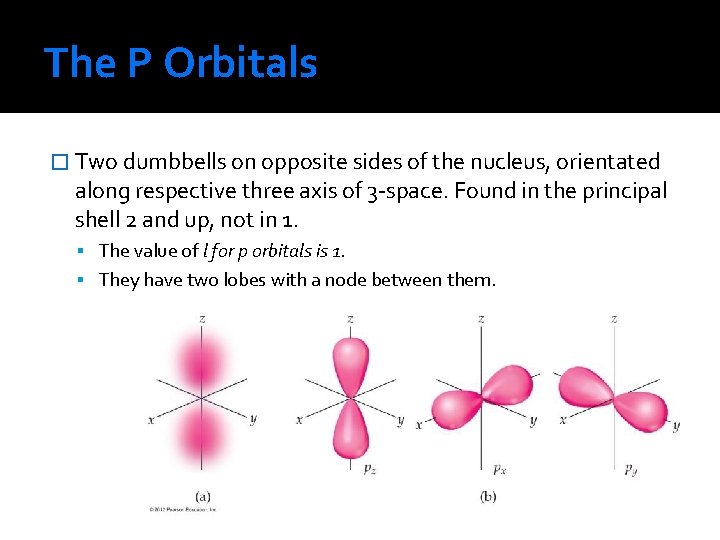

The P Orbitals � Two dumbbells on opposite sides of the nucleus, orientated along respective three axis of 3 -space. Found in the principal shell 2 and up, not in 1. The value of l for p orbitals is 1. They have two lobes with a node between them.

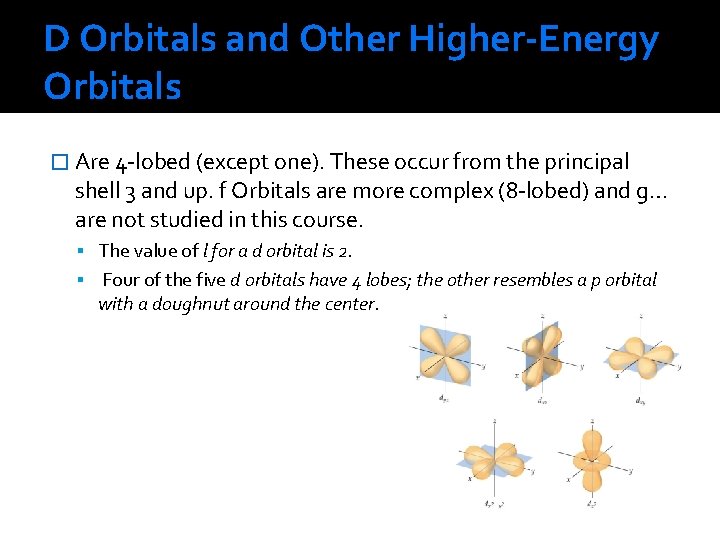

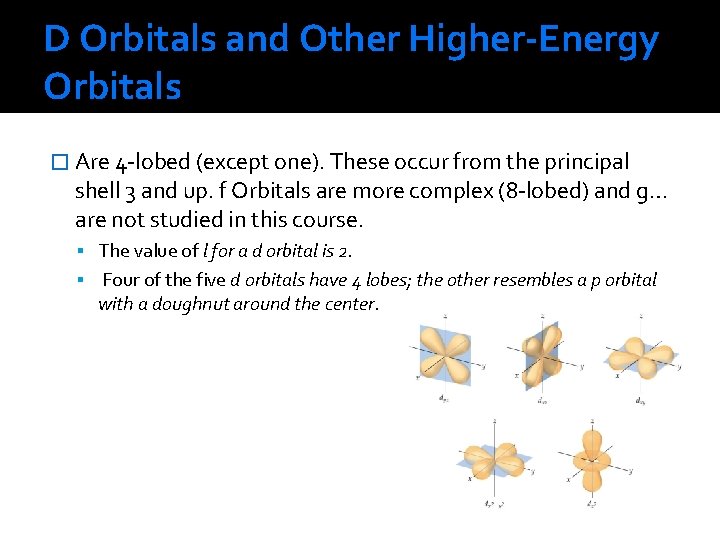

D Orbitals and Other Higher-Energy Orbitals � Are 4 -lobed (except one). These occur from the principal shell 3 and up. f Orbitals are more complex (8 -lobed) and g… are not studied in this course. The value of l for a d orbital is 2. Four of the five d orbitals have 4 lobes; the other resembles a p orbital with a doughnut around the center.

Orbitals & Their Energies � For a one-electron hydrogen atom, orbitals on the same energy level have the same energy. That is, they are degenerate. � As the number of electrons increases, though, so does the repulsion between them. � Therefore, in many-electron atoms, orbitals on the same energy level are no longer degenerate. � In many-electron atom, for a given value of n, the energy level of orbital increases with increasing value of l.

Electron Spin & the Pauli’s Exclusion Principle � In the 1920 s, it was discovered that two electrons in the same orbital do not have exactly the same energy. � The “spin” of an electron describes its magnetic field, which affects its energy.

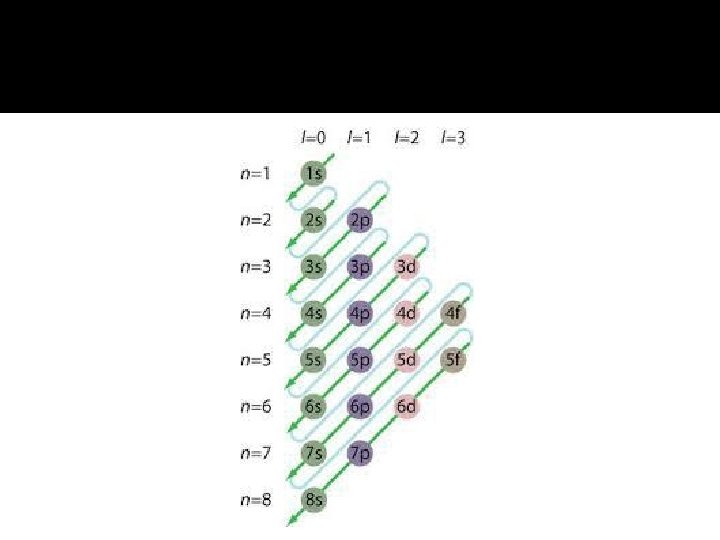

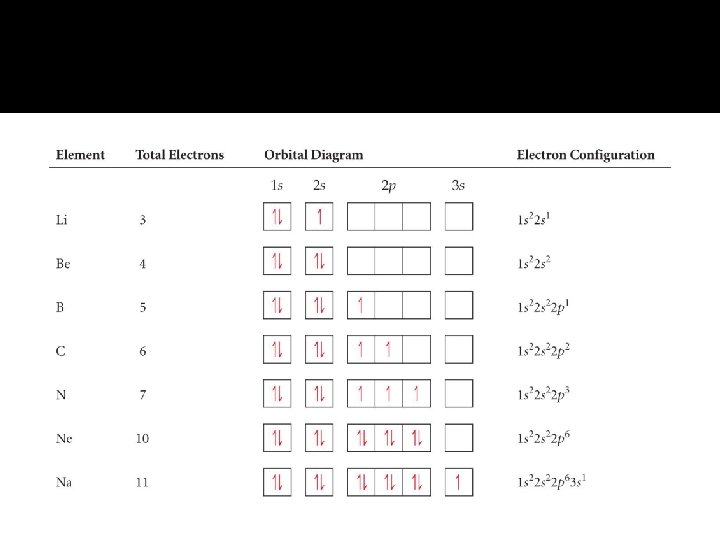

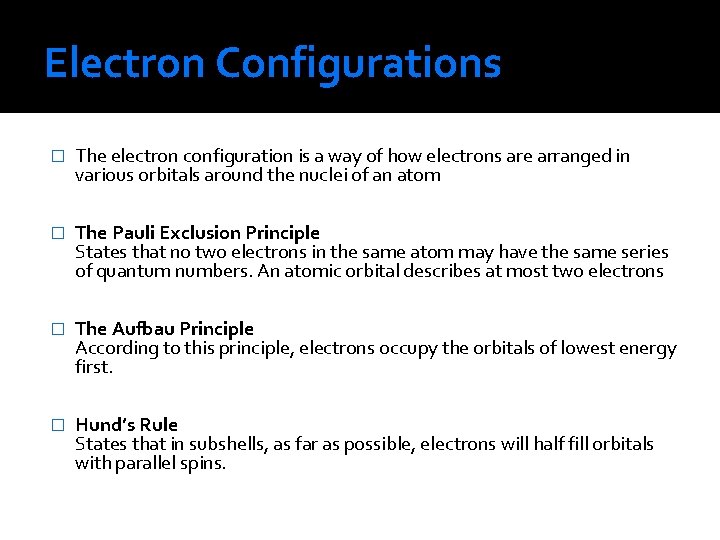

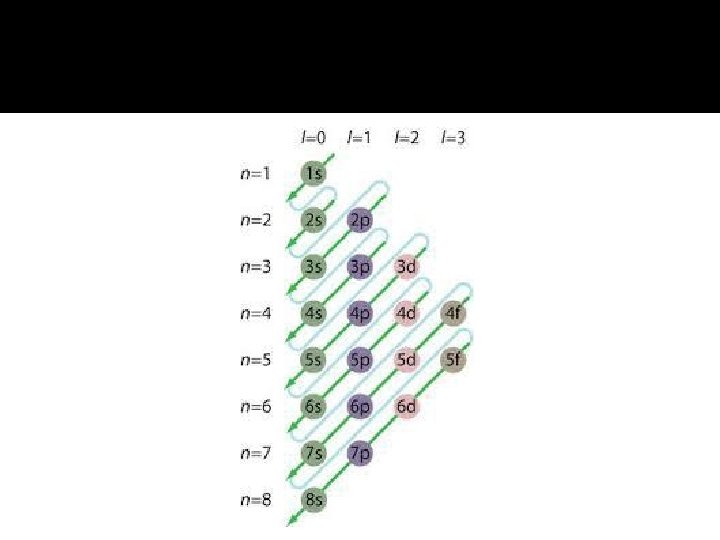

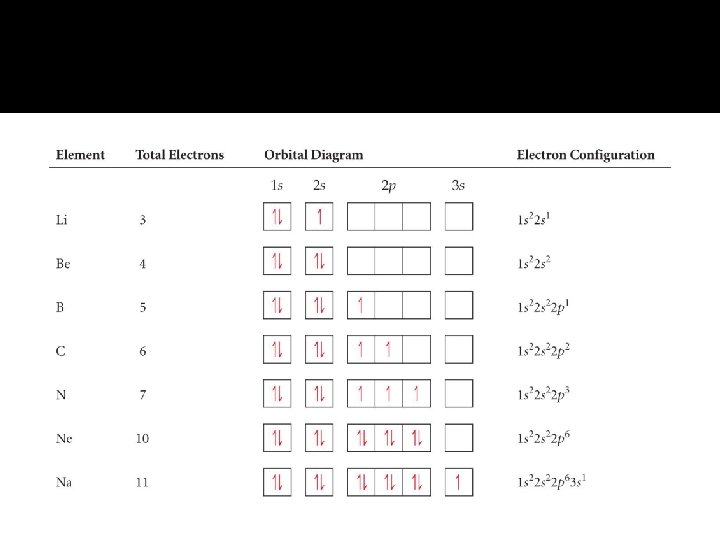

Electron Configurations � The electron configuration is a way of how electrons are arranged in various orbitals around the nuclei of an atom � The Pauli Exclusion Principle States that no two electrons in the same atom may have the same series of quantum numbers. An atomic orbital describes at most two electrons � The Aufbau Principle According to this principle, electrons occupy the orbitals of lowest energy first. � Hund’s Rule States that in subshells, as far as possible, electrons will half fill orbitals with parallel spins.

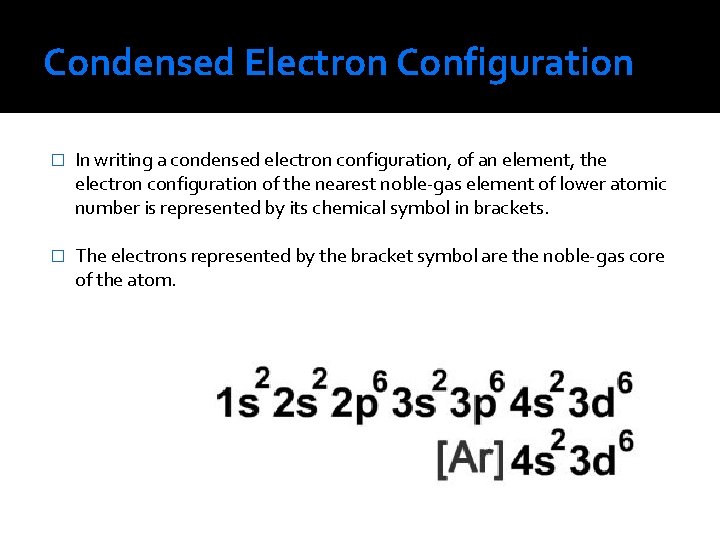

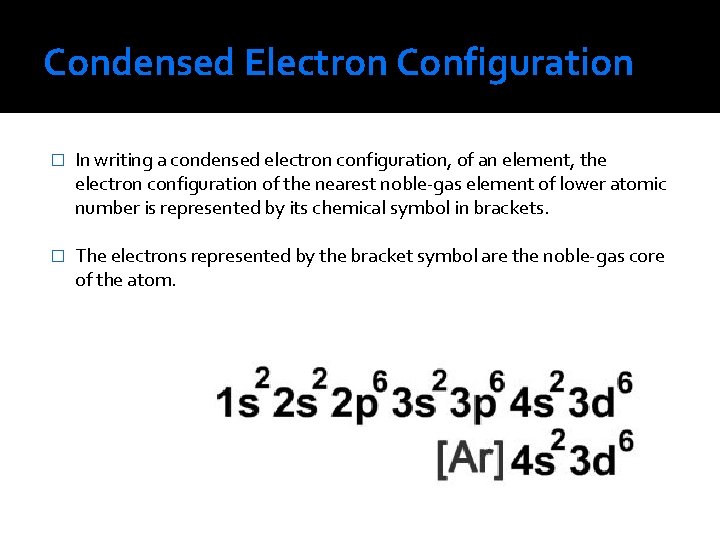

Condensed Electron Configuration � In writing a condensed electron configuration, of an element, the electron configuration of the nearest noble-gas element of lower atomic number is represented by its chemical symbol in brackets. � The electrons represented by the bracket symbol are the noble-gas core of the atom.

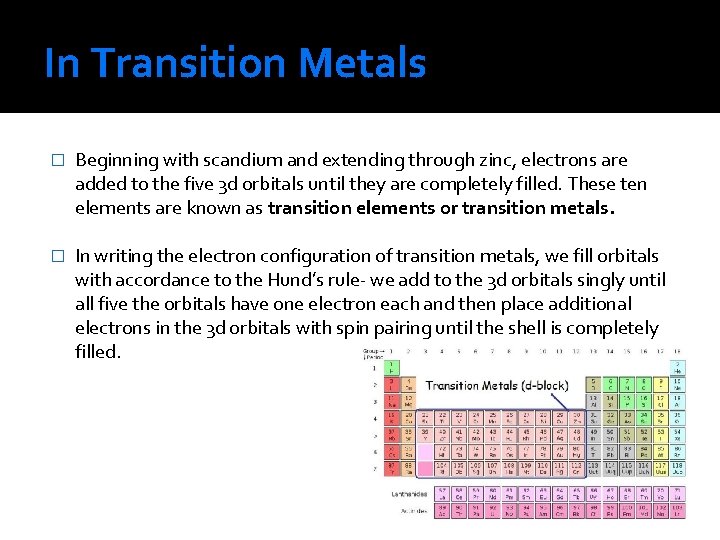

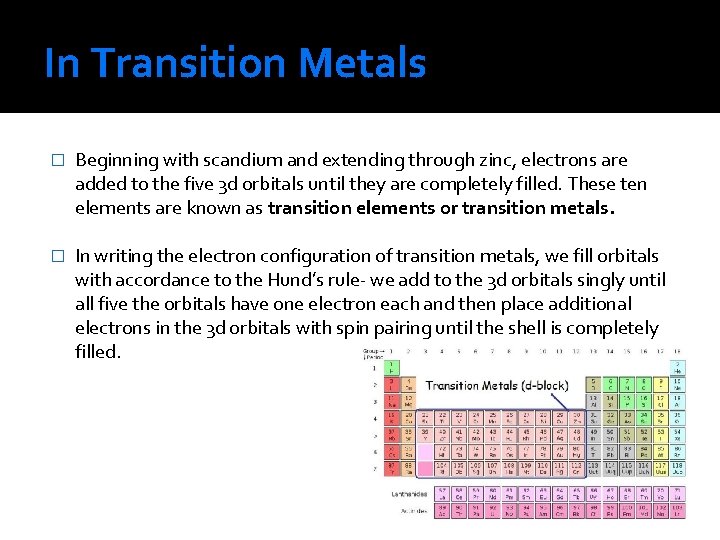

In Transition Metals � Beginning with scandium and extending through zinc, electrons are added to the five 3 d orbitals until they are completely filled. These ten elements are known as transition elements or transition metals. � In writing the electron configuration of transition metals, we fill orbitals with accordance to the Hund’s rule- we add to the 3 d orbitals singly until all five the orbitals have one electron each and then place additional electrons in the 3 d orbitals with spin pairing until the shell is completely filled.

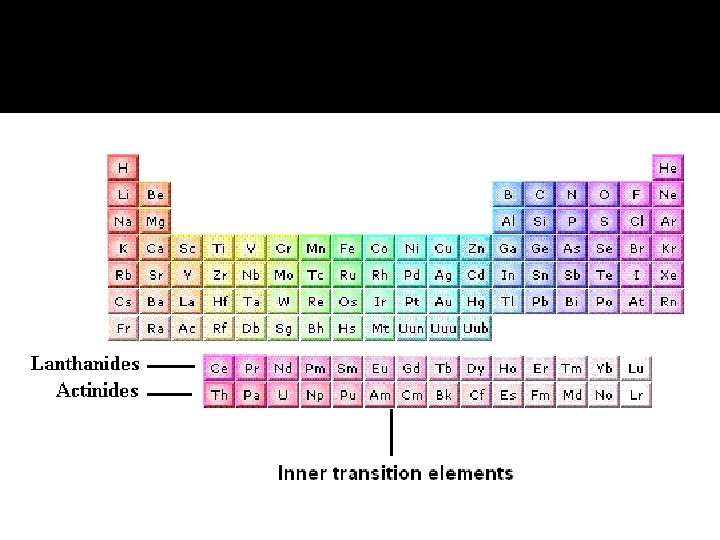

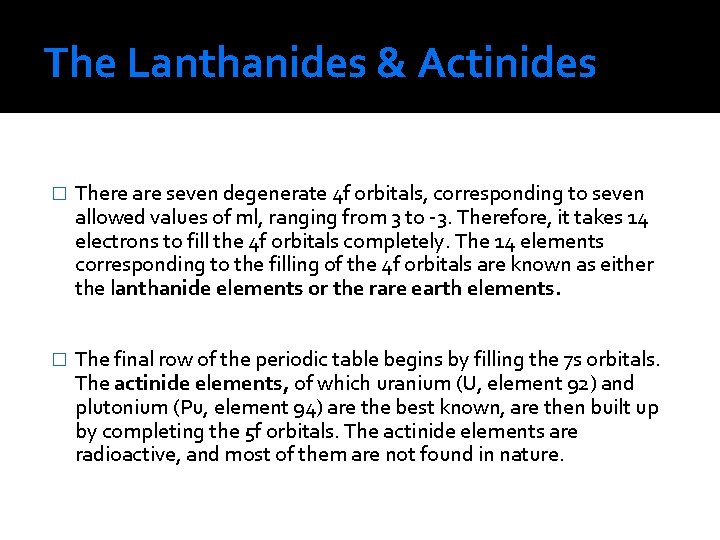

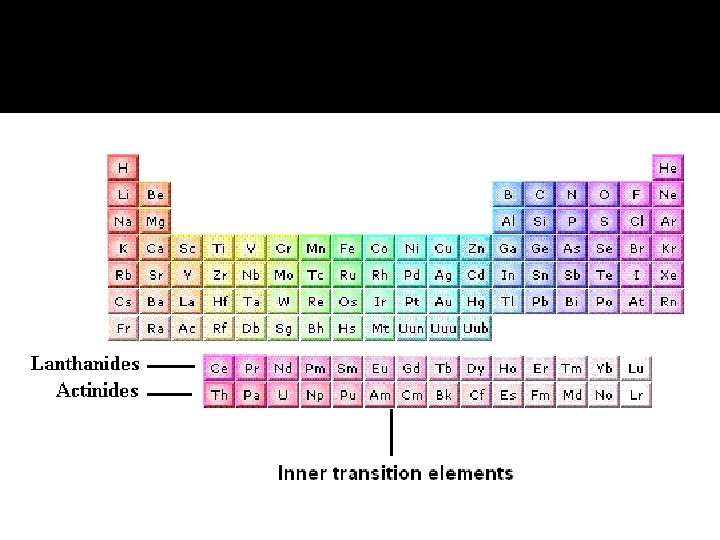

The Lanthanides & Actinides � There are seven degenerate 4 f orbitals, corresponding to seven allowed values of ml, ranging from 3 to -3. Therefore, it takes 14 electrons to fill the 4 f orbitals completely. The 14 elements corresponding to the filling of the 4 f orbitals are known as either the lanthanide elements or the rare earth elements. � The final row of the periodic table begins by filling the 7 s orbitals. The actinide elements, of which uranium (U, element 92) and plutonium (Pu, element 94) are the best known, are then built up by completing the 5 f orbitals. The actinide elements are radioactive, and most of them are not found in nature.

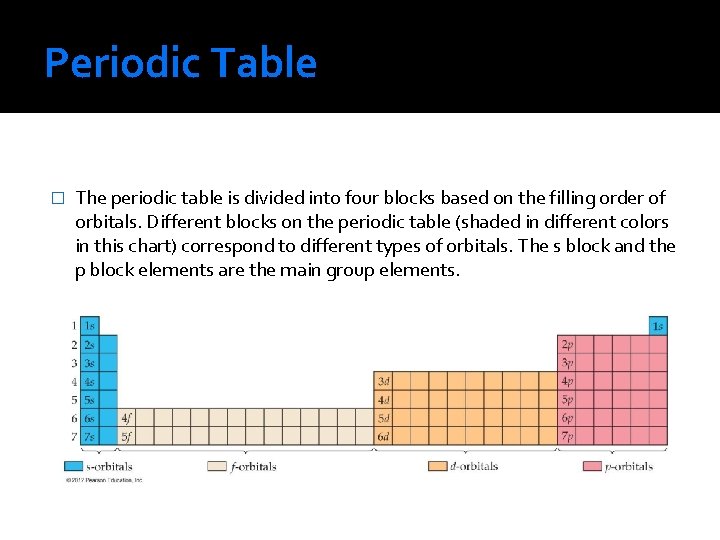

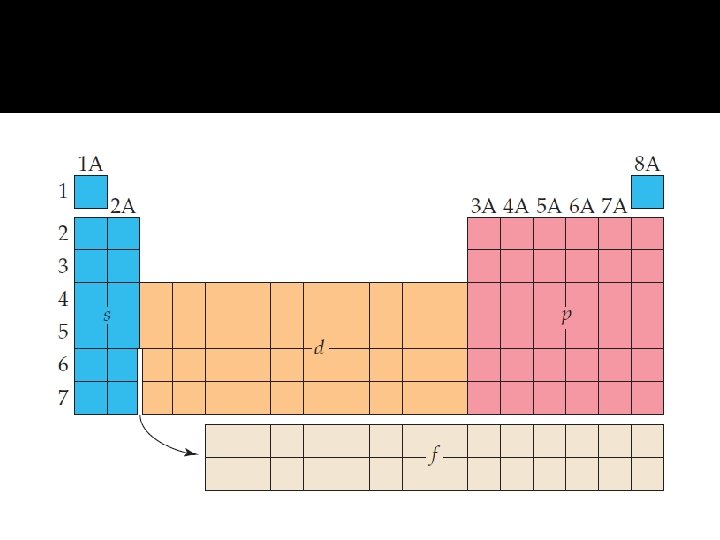

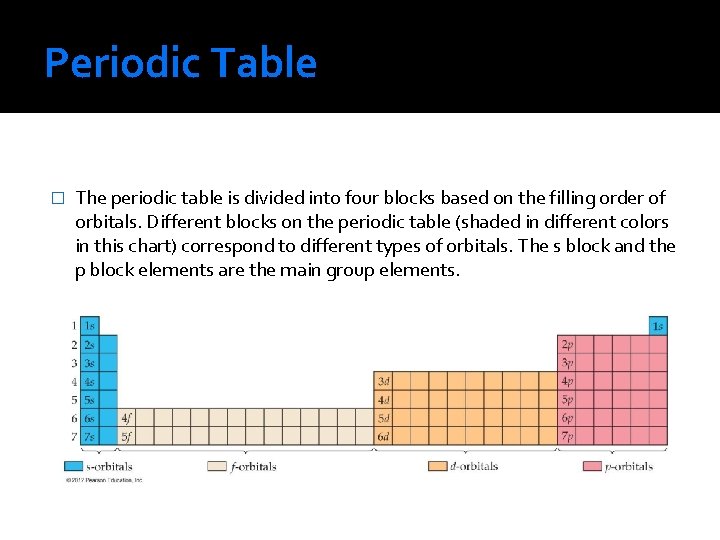

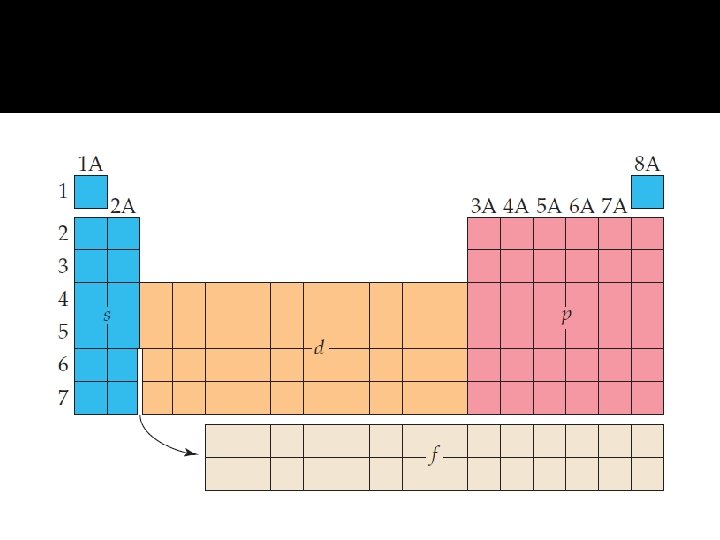

Periodic Table � The periodic table is divided into four blocks based on the filling order of orbitals. Different blocks on the periodic table (shaded in different colors in this chart) correspond to different types of orbitals. The s block and the p block elements are the main group elements.

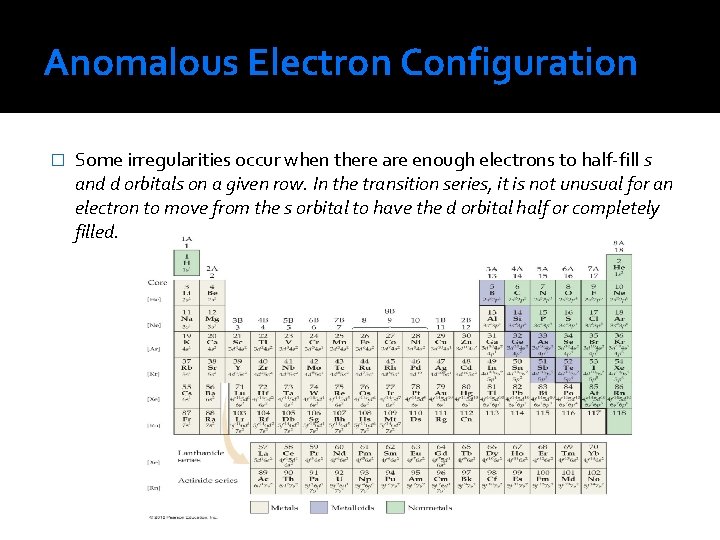

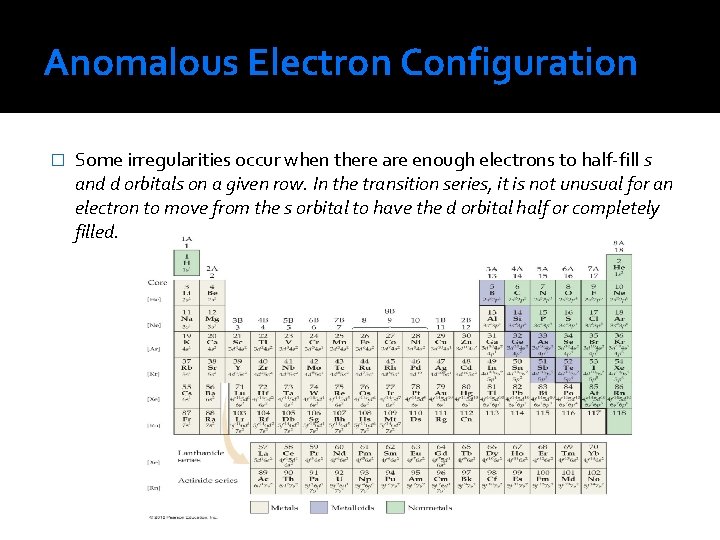

Anomalous Electron Configuration � Some irregularities occur when there are enough electrons to half-fill s and d orbitals on a given row. In the transition series, it is not unusual for an electron to move from the s orbital to have the d orbital half or completely filled.

References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Lecture: Theodore E. B. , Eugene, H. L. H. , Bruce E. B. , Catherine M. , Patrick W. , (2011). Chemistry: The Central Science (12 Ed). Prentice Hall. USA. Laboratory: Theodore E. B. , John H. N. , Kenneth C. K. , Matthew S. (2011). Laboratory Experiments for Chemistry: The Central Science (12 Ed). Prentice Hall. USA. Theodore E. B. , (2011). Solutions to Exercises for Chemistry: The Central Science. Prentice Hall. USA. John M. , Robert C. F. (2010). Chemistry (4 Ed): Prentice Hall Companion Website. http: //wps. prenhall. com/esm_mcmurry_chemistry_4/9/2408/616516. cw/inde x. html Chemistry Online at http: //preparatorychemistry. com/Bishop_Chemistry_First. htm Chemistry and You at http: //www. saskschools. ca/curr_content/science 9/chemistry/index. html Teachers Notes

END