CHAPTER 20 Measuring a Nations Production and Income

- Slides: 31

CHAPTER 20 Measuring a Nation’s Production and Income © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin 1

Macroeconomics u Macroeconomics is the branch of economics that deals with any nation’s economy as a whole. u Macroeconomics focuses on issues such as unemployment, inflation, growth, trade, and the gross domestic product. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin

Macroeconomics u Macroeconomics focuses on two key issues: l l Understanding economic growth in the long run and the factors behind the rise in living standards in modern economies Understanding economic fluctuations— the ups and downs of the economy over time © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin

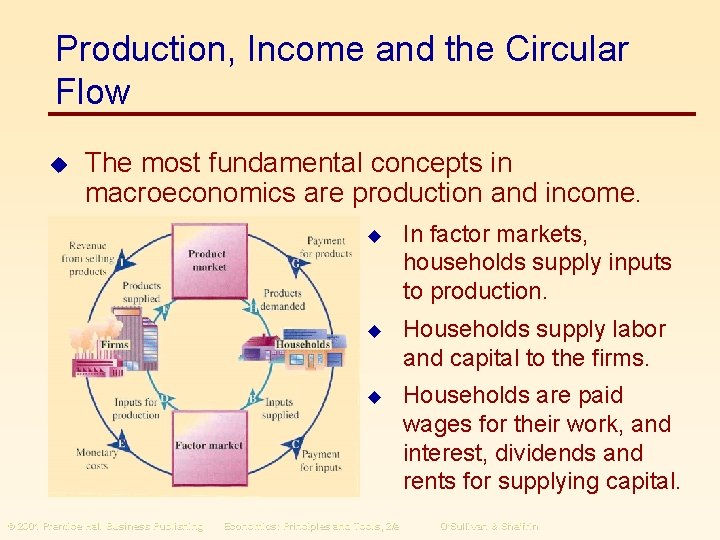

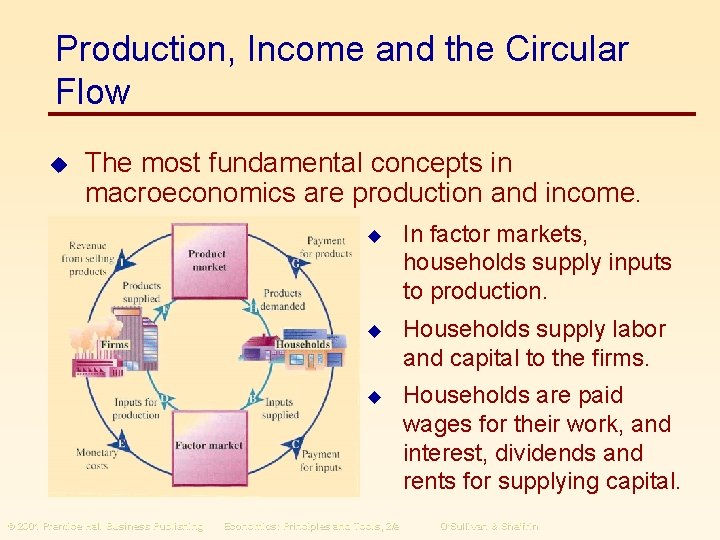

Production, Income and the Circular Flow u The most fundamental concepts in macroeconomics are production and income. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing u In factor markets, households supply inputs to production. u Households supply labor and capital to the firms. u Households are paid wages for their work, and interest, dividends and rents for supplying capital. Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin

Production, Income and the Circular Flow u u u © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e Households use their income to purchase goods and services in product markets. The payments received by firms are used to pay for factors of production. In sum, corresponding to the production of goods and services in the economy are flows of income to households. O’Sullivan & Sheffrin

Measuring Gross Domestic Product u The most common measure of the total output of an economy is gross domestic product, the total market value of all the final goods and services produced within an economy in a given year. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin

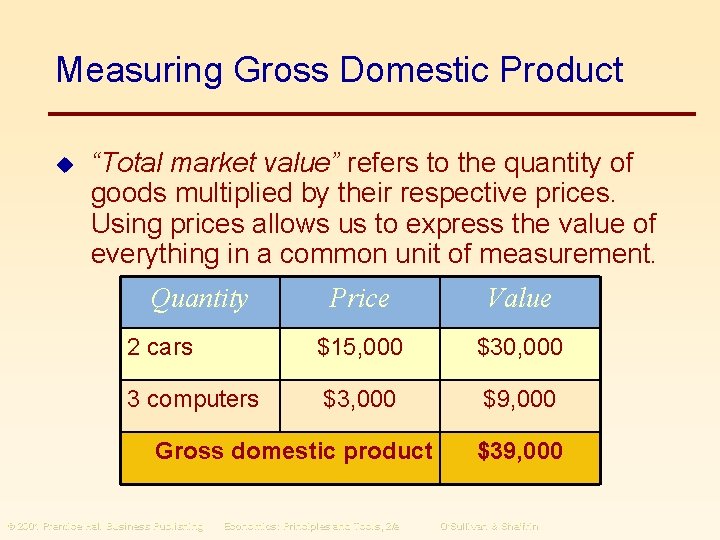

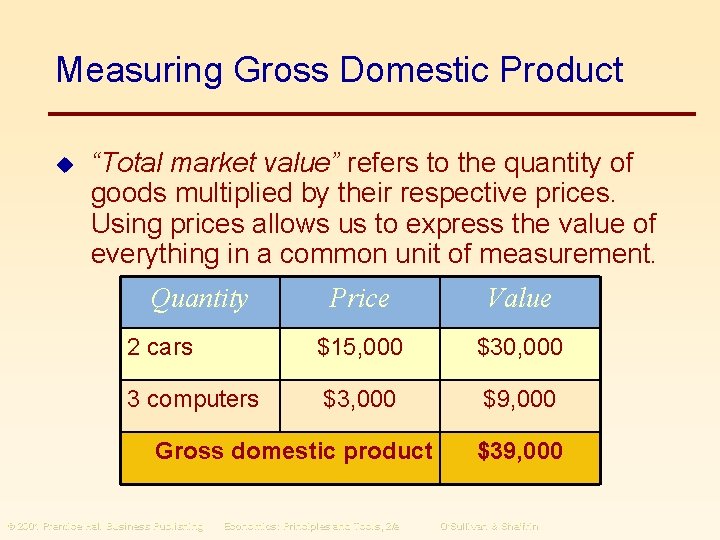

Measuring Gross Domestic Product u “Total market value” refers to the quantity of goods multiplied by their respective prices. Using prices allows us to express the value of everything in a common unit of measurement. Quantity Price Value 2 cars $15, 000 $30, 000 3 computers $3, 000 $9, 000 Gross domestic product © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e $39, 000 O’Sullivan & Sheffrin

Measuring Gross Domestic Product u u u “Final goods and services” refers to the goods and services that are sold to the ultimate, or final, purchasers. In order to avoid double counting, we do not count intermediate goods, or goods used in the production process. The value of the final good already reflects the price of the intermediate goods contained in it. “In a given year” means that the sale of goods produced in prior years, for example, used cars, are not included in GDP this year. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin

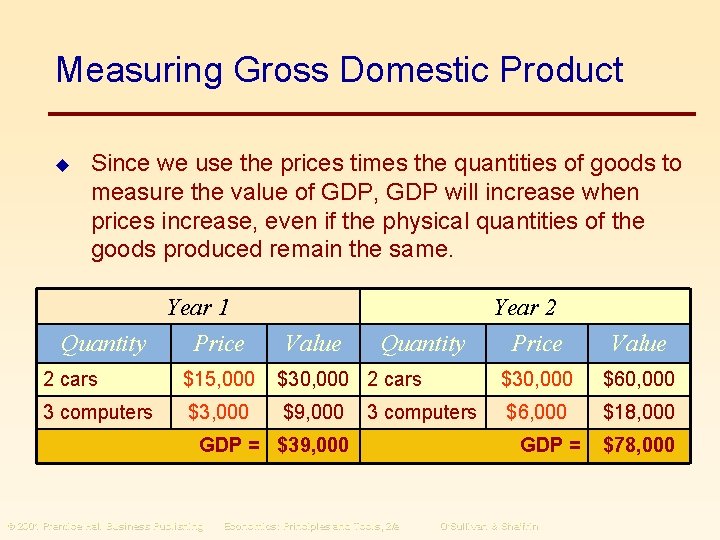

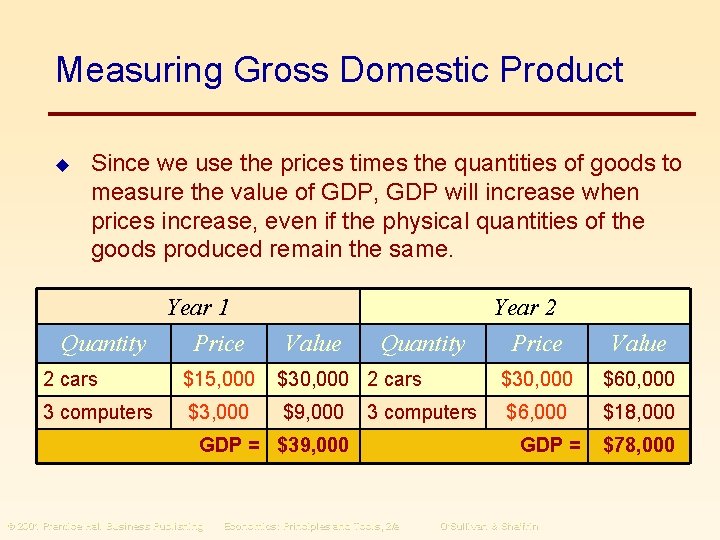

Measuring Gross Domestic Product u Since we use the prices times the quantities of goods to measure the value of GDP, GDP will increase when prices increase, even if the physical quantities of the goods produced remain the same. Year 1 Quantity Price Value Quantity Year 2 Price Value 2 cars $15, 000 $30, 000 2 cars $30, 000 $60, 000 3 computers $3, 000 $9, 000 $6, 000 $18, 000 3 computers GDP = $39, 000 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e GDP = O’Sullivan & Sheffrin $78, 000

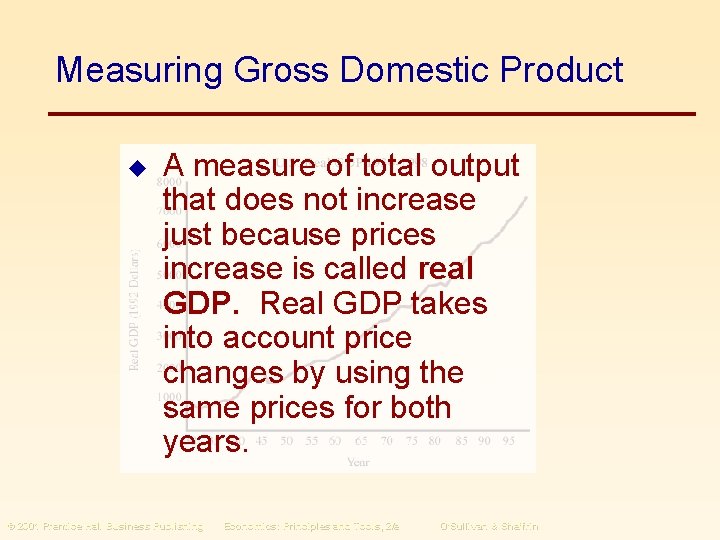

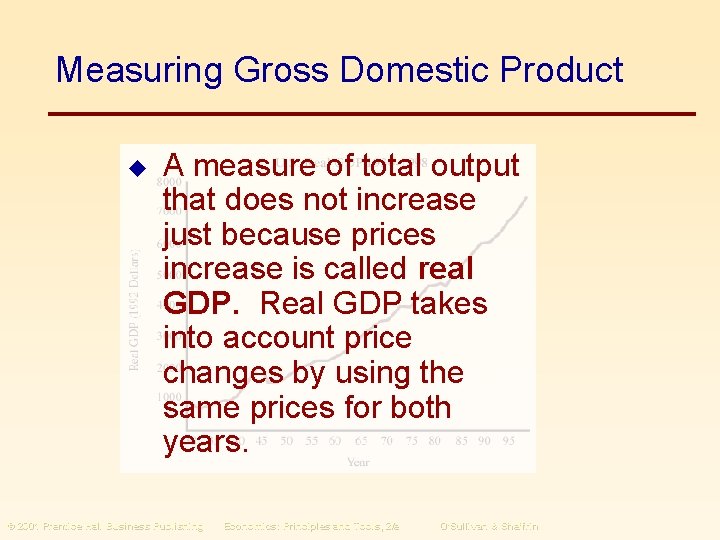

Measuring Gross Domestic Product u A measure of total output that does not increase just because prices increase is called real GDP. Real GDP takes into account price changes by using the same prices for both years. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin

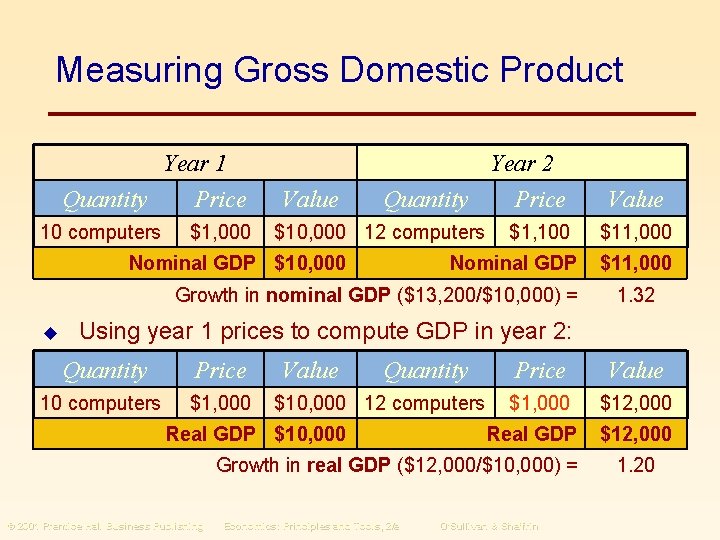

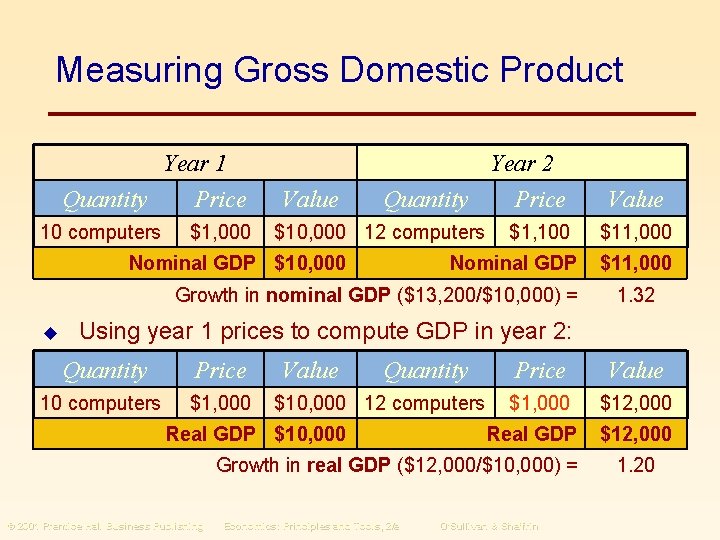

Measuring Gross Domestic Product Year 1 Quantity Price 10 computers $1, 000 Value Year 2 Quantity Price $10, 000 12 computers Nominal GDP $10, 000 $1, 100 Nominal GDP Growth in nominal GDP ($13, 200/$10, 000) = u Value $11, 000 1. 32 Using year 1 prices to compute GDP in year 2: Quantity Price 10 computers $1, 000 Value Quantity $10, 000 12 computers Real GDP $10, 000 Price Value $1, 000 $12, 000 Real GDP Growth in real GDP ($12, 000/$10, 000) = © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin $12, 000 1. 20

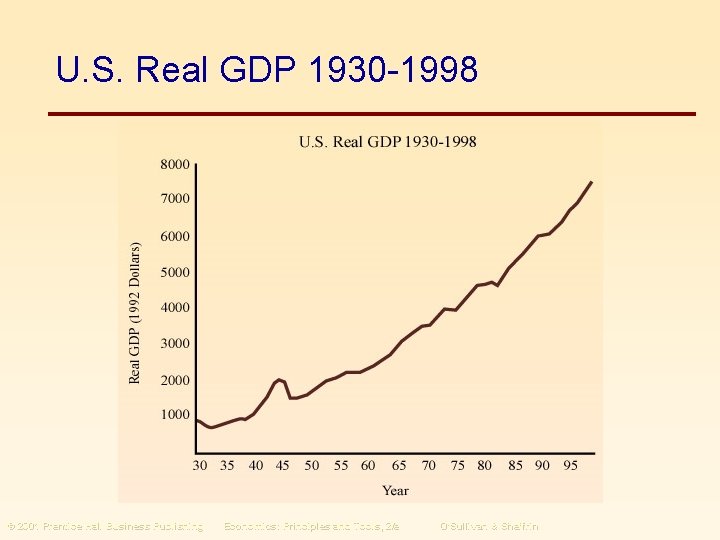

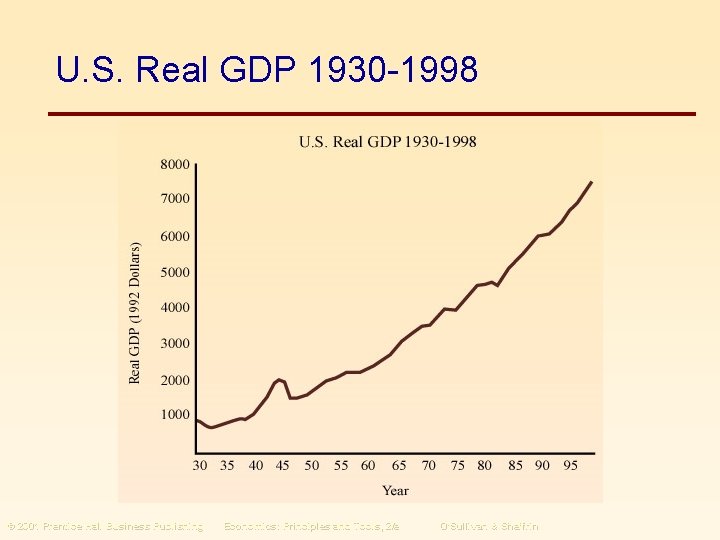

U. S. Real GDP 1930 -1998 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin

Who Purchases GDP? u Economists divide GDP into four broad expenditure categories: 1. Consumption expenditures: purchases by consumers 2. Private investment expenditures: purchases by firms 3. Government purchases: purchases by federal, state, and local governments 4. Net exports: net purchases by the foreign sector, or domestic exports minus domestic imports © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin

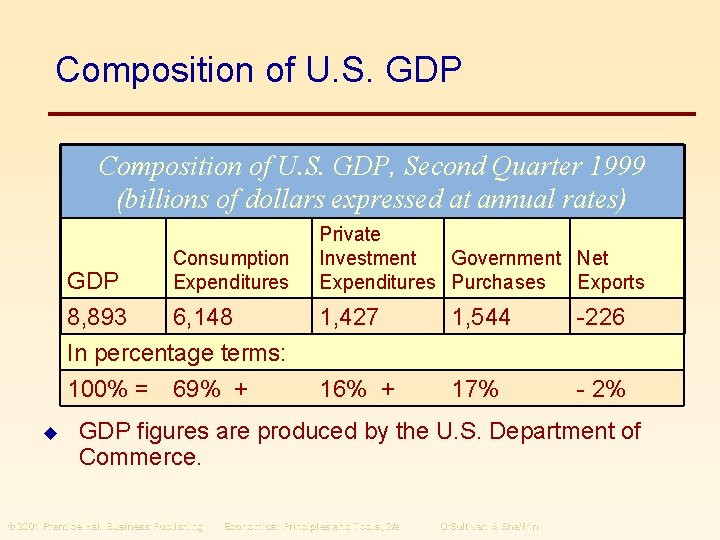

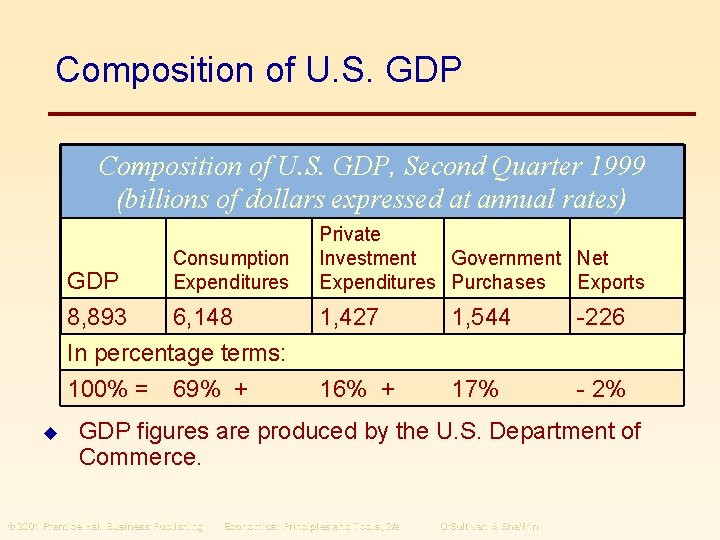

Composition of U. S. GDP, Second Quarter 1999 (billions of dollars expressed at annual rates) Consumption Expenditures GDP 8, 893 6, 148 In percentage terms: 100% = 69% + u Private Investment Government Net Expenditures Purchases Exports 1, 427 1, 544 -226 16% + 17% - 2% GDP figures are produced by the U. S. Department of Commerce. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin

Consumption Expenditures u u u Consumption expenditures comprise purchases of currently produced, domestic or foreign, goods and services. Consumption is broken down into: l Durable goods. l Nondurable goods. l Services, the fastest growing component of consumption. Consumption comprises 68% of total purchases. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin

Private Investment Expenditures u Private investment expenditures include: u Spending on new plants and equipment. l Newly produced housing. l Increase in inventories during the current year. Note: investment in everyday talk refers to the purchase of an existing financial asset. Investment in GDP accounts refers to the purchase of new final goods and services by firms. Don’t confuse the two. l © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin

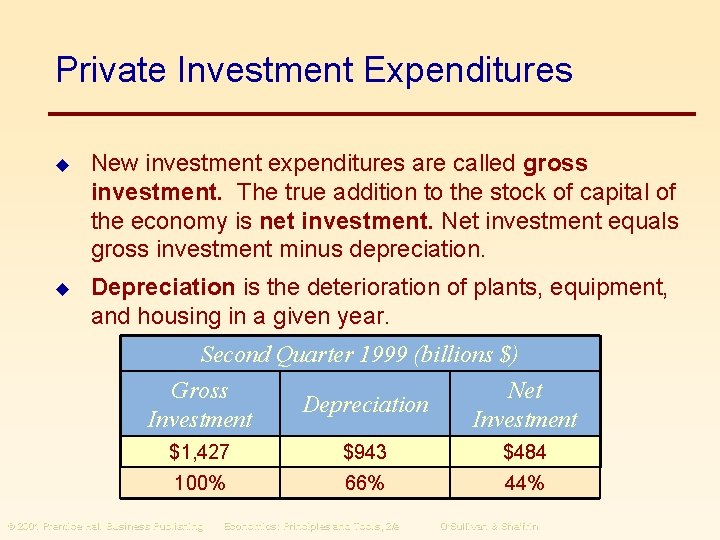

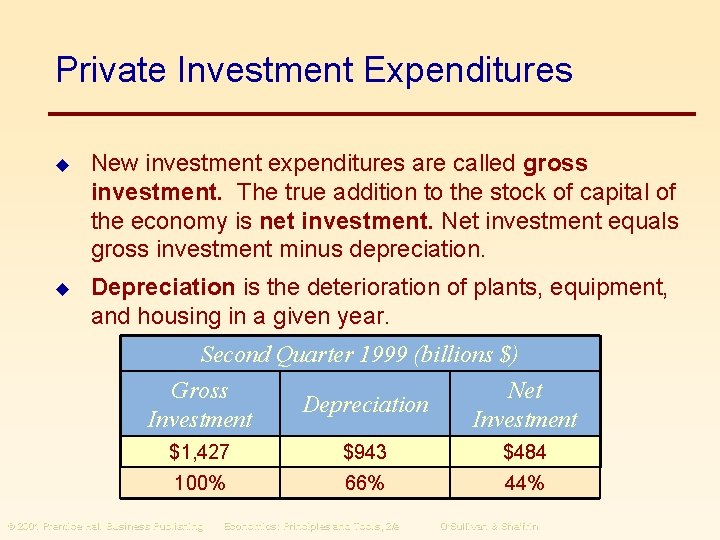

Private Investment Expenditures u New investment expenditures are called gross investment. The true addition to the stock of capital of the economy is net investment. Net investment equals gross investment minus depreciation. u Depreciation is the deterioration of plants, equipment, and housing in a given year. Second Quarter 1999 (billions $) Gross Net Depreciation Investment $1, 427 $943 $484 100% 66% 44% © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin

Government Purchases u Includes any goods the government purchases plus the wages and benefits of all government employees; but does not include all the government spending. l l Transfer payments, or government payments to individuals which are not associated with the production of any goods and services, are not included in government purchases. This means that a large part of the federal government budget is not part of GDP. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin

Net Exports u Net exports are total exports minus total imports. By including net exports in GDP, we correctly measure U. S. production—by adding exports and subtracting imports. l l Purchases of foreign goods (imports) are subtracted from GDP because these goods were not produced in the U. S. Any goods that are produced in the U. S. and sold abroad (exports) are included in GDP. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin

Net Exports u u Net exports for the U. S. in 1999 were $226. This means that the U. S. bought $226 billion more goods and services from abroad than it sold abroad. The balance of trade: l l l Trade deficit: imports > exports Trade surplus: imports < exports Trade balance: imports = exports © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin

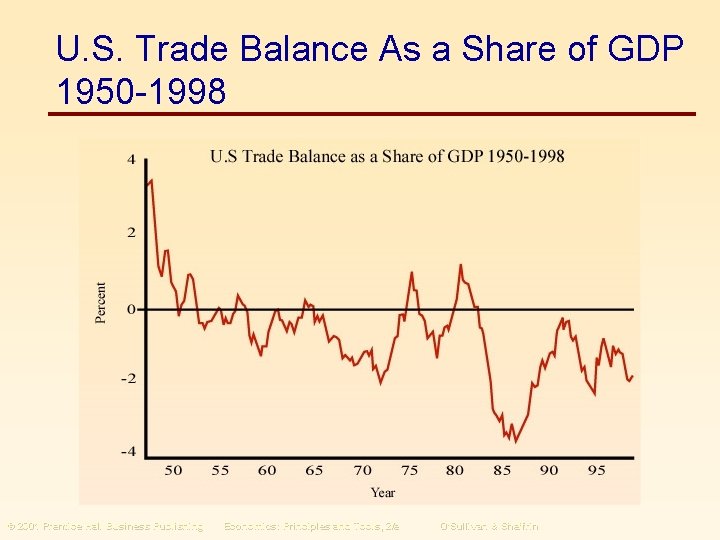

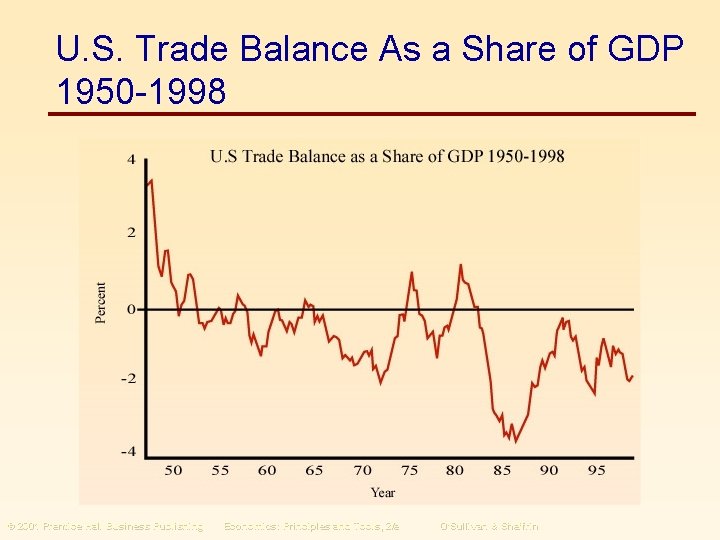

U. S. Trade Balance As a Share of GDP 1950 -1998 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin

The Meaning of Continued Trade Deficits u u u When the U. S. runs a trade deficit, we are forced to sell some of our assets to individuals or governments in foreign countries. We give up more dollars from exports than we receive from imports. Excess dollars in the hands of foreigners are used to buy U. S. assets such as stocks, bonds or real estate. If a country runs a trade surplus with one country and an equally large deficit with another, it does not add to its stock of foreign assets. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin

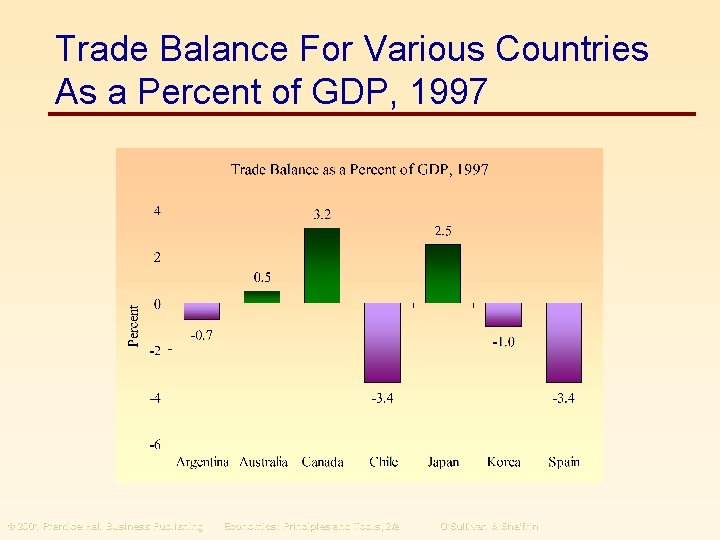

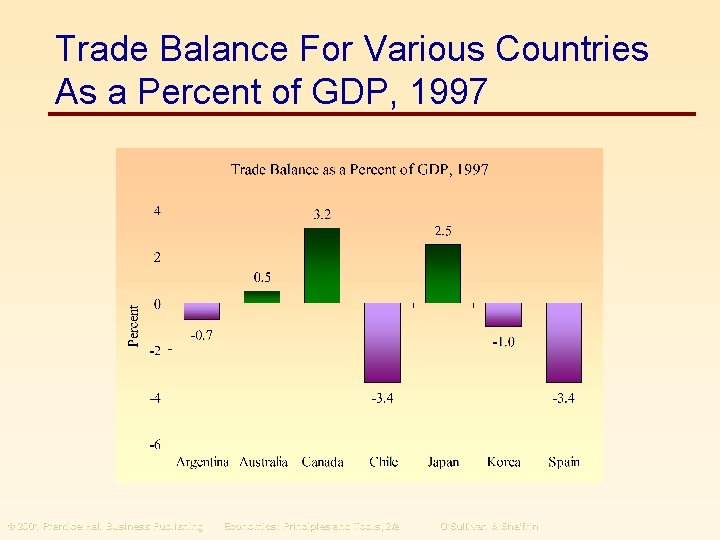

Trade Balance For Various Countries As a Percent of GDP, 1997 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin

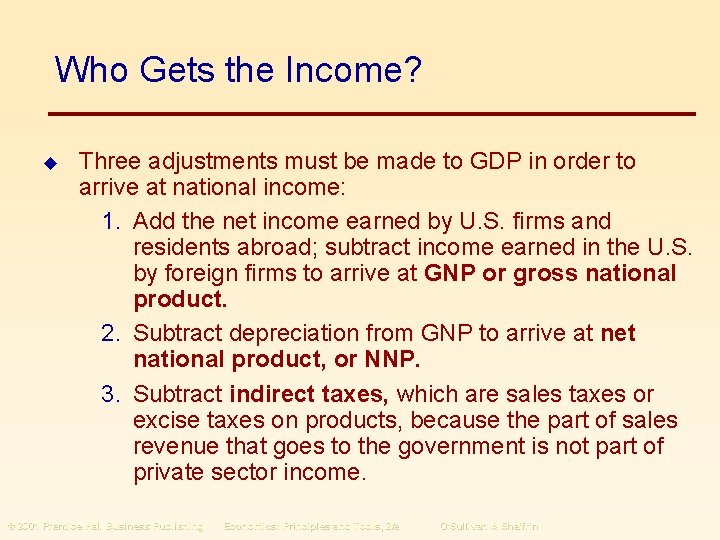

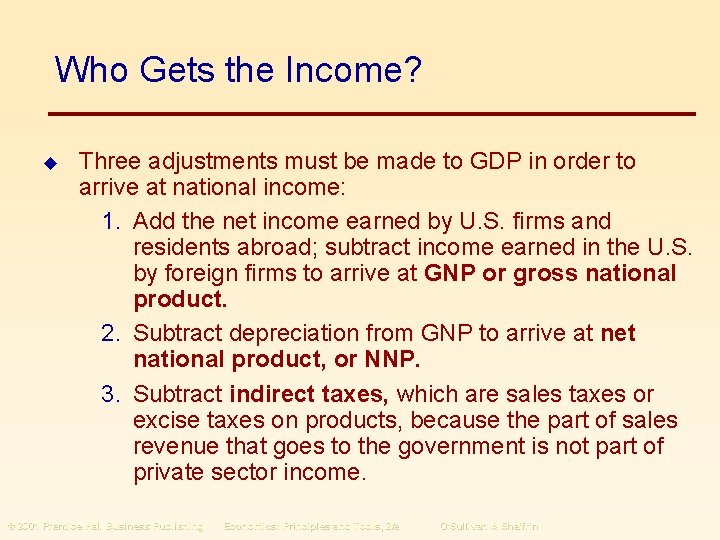

Who Gets the Income? u Three adjustments must be made to GDP in order to arrive at national income: 1. Add the net income earned by U. S. firms and residents abroad; subtract income earned in the U. S. by foreign firms to arrive at GNP or gross national product. 2. Subtract depreciation from GNP to arrive at net national product, or NNP. 3. Subtract indirect taxes, which are sales taxes or excise taxes on products, because the part of sales revenue that goes to the government is not part of private sector income. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin

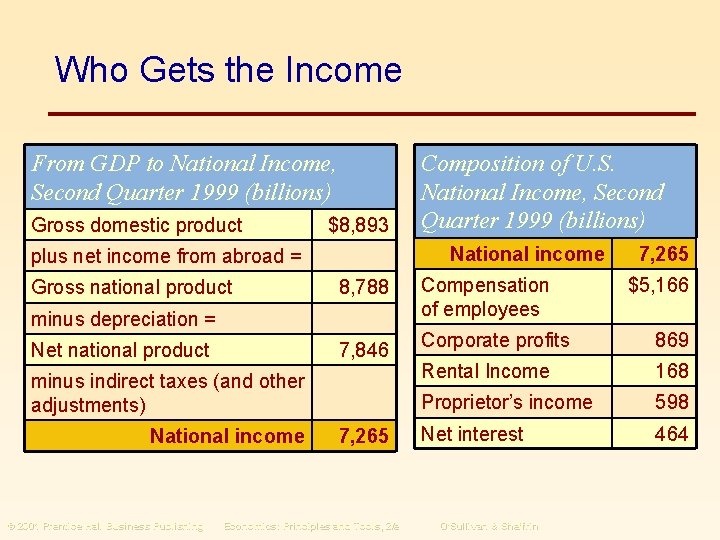

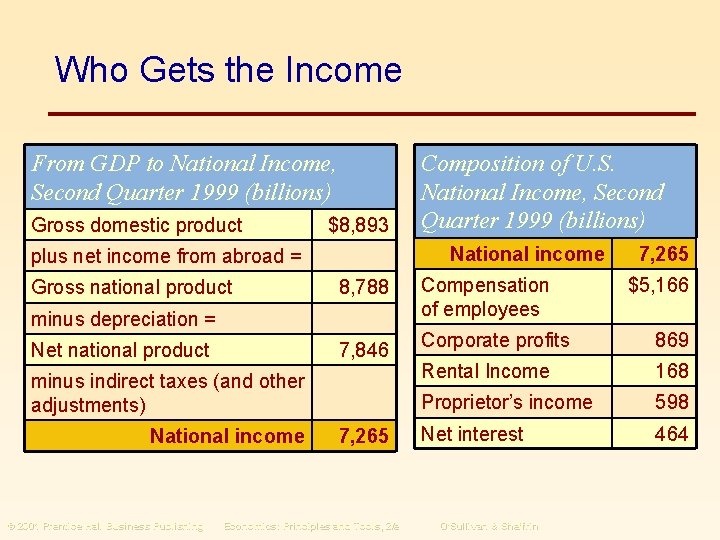

Who Gets the Income From GDP to National Income, Second Quarter 1999 (billions) Gross domestic product $8, 893 National income plus net income from abroad = Gross national product Compensation of employees 7, 846 Corporate profits 869 Rental Income 168 Proprietor’s income 598 Net interest 464 minus indirect taxes (and other adjustments) National income © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing 7, 265 8, 788 minus depreciation = Net national product Composition of U. S. National Income, Second Quarter 1999 (billions) 7, 265 Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin $5, 166

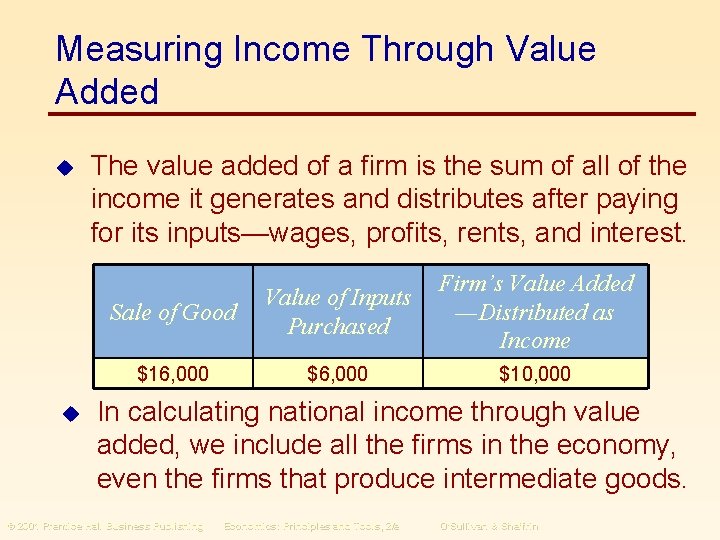

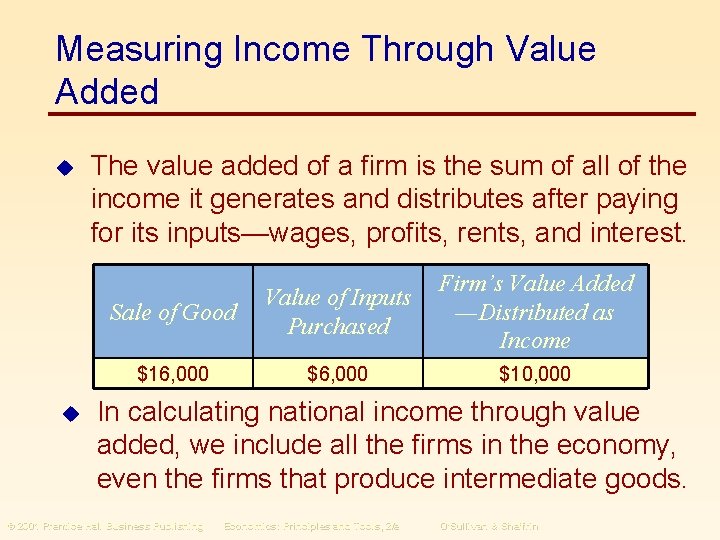

Measuring Income Through Value Added u u The value added of a firm is the sum of all of the income it generates and distributes after paying for its inputs—wages, profits, rents, and interest. Sale of Good Value of Inputs Purchased Firm’s Value Added —Distributed as Income $16, 000 $10, 000 In calculating national income through value added, we include all the firms in the economy, even the firms that produce intermediate goods. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin

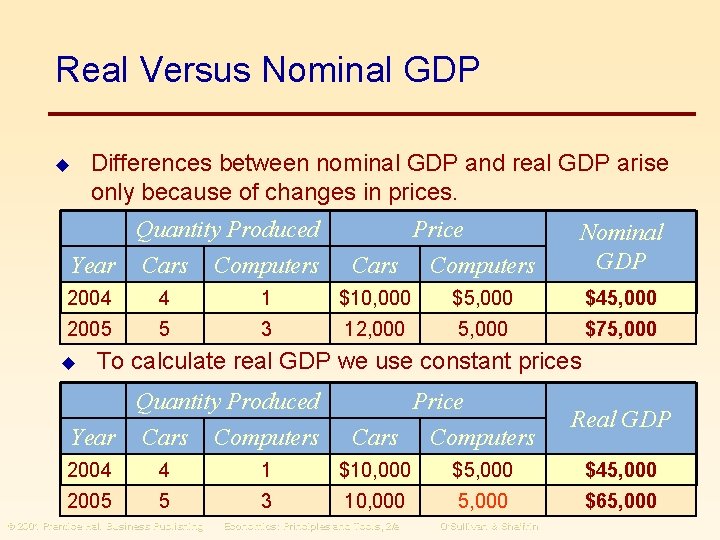

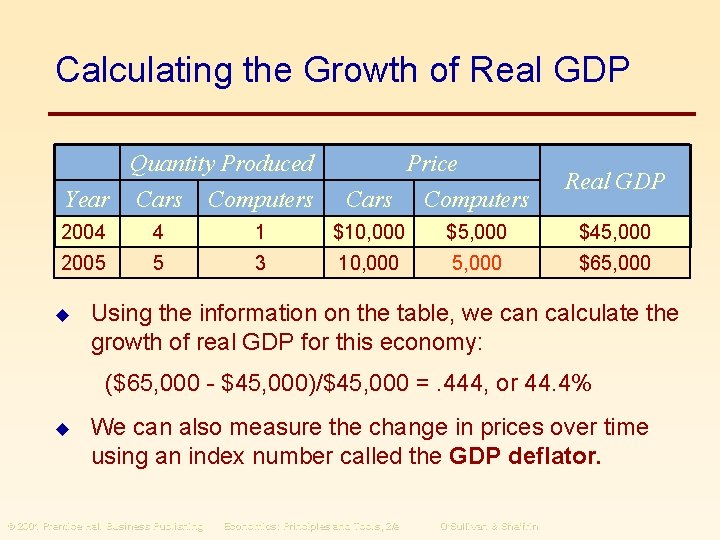

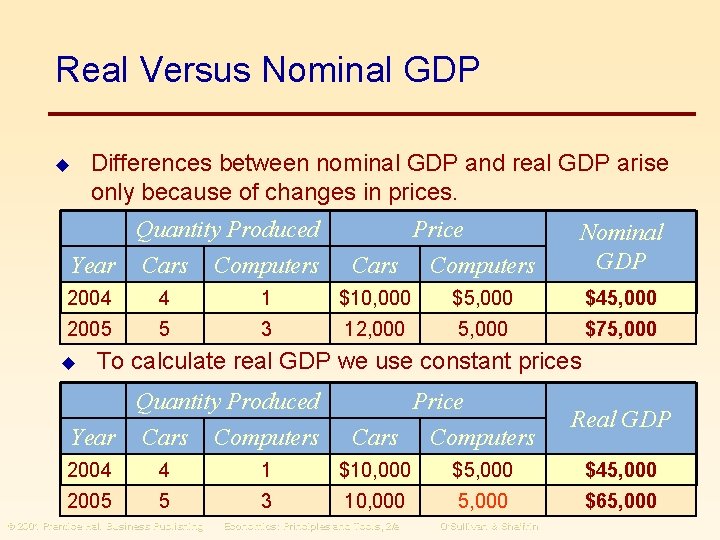

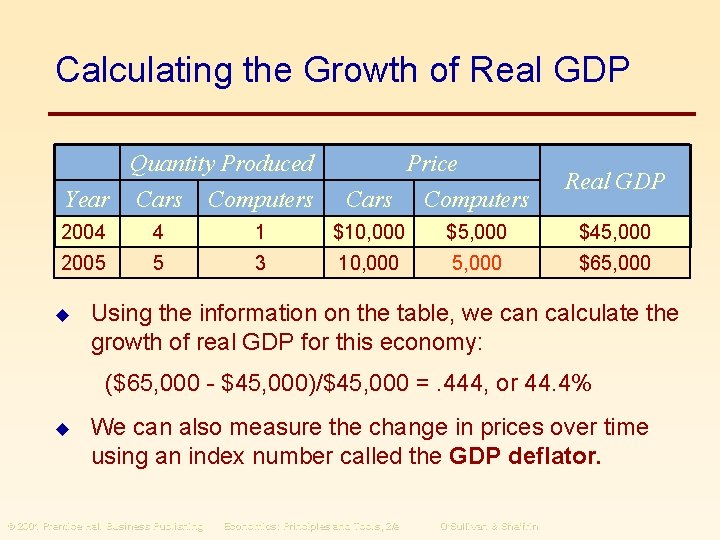

Real Versus Nominal GDP u Differences between nominal GDP and real GDP arise only because of changes in prices. Quantity Produced Year Cars Computers Price Cars Computers Nominal GDP 2004 4 1 $10, 000 $5, 000 $45, 000 2005 5 3 12, 000 5, 000 $75, 000 u To calculate real GDP we use constant prices Quantity Produced Year Cars Computers Price Cars Computers Real GDP 2004 4 1 $10, 000 $5, 000 $45, 000 2005 5 3 10, 000 5, 000 $65, 000 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin

Calculating the Growth of Real GDP Quantity Produced Year Cars Computers Price Cars Computers Real GDP 2004 4 1 $10, 000 $5, 000 $45, 000 2005 5 3 10, 000 5, 000 $65, 000 u Using the information on the table, we can calculate the growth of real GDP for this economy: ($65, 000 - $45, 000)/$45, 000 =. 444, or 44. 4% u We can also measure the change in prices over time using an index number called the GDP deflator. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin

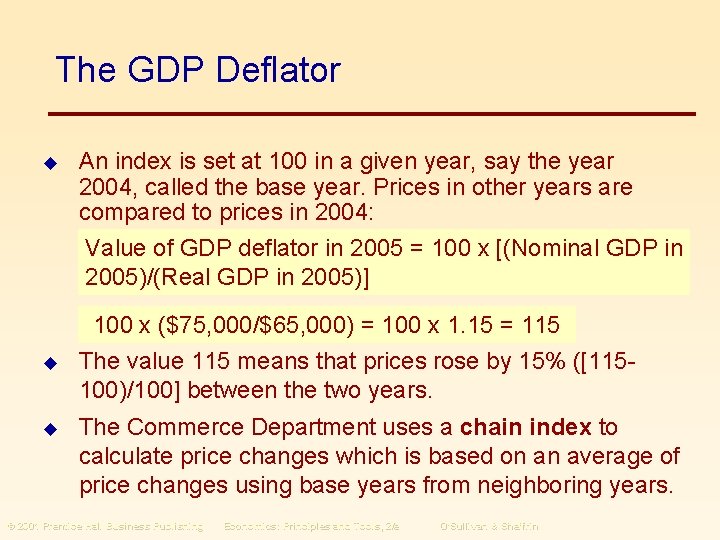

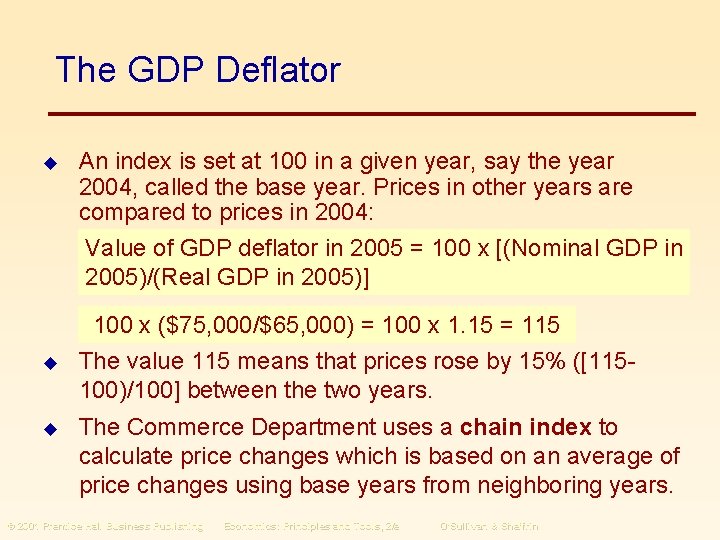

The GDP Deflator u u u An index is set at 100 in a given year, say the year 2004, called the base year. Prices in other years are compared to prices in 2004: Value of GDP deflator in 2005 = 100 x [(Nominal GDP in 2005)/(Real GDP in 2005)] 100 x ($75, 000/$65, 000) = 100 x 1. 15 = 115 The value 115 means that prices rose by 15% ([115100)/100] between the two years. The Commerce Department uses a chain index to calculate price changes which is based on an average of price changes using base years from neighboring years. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin

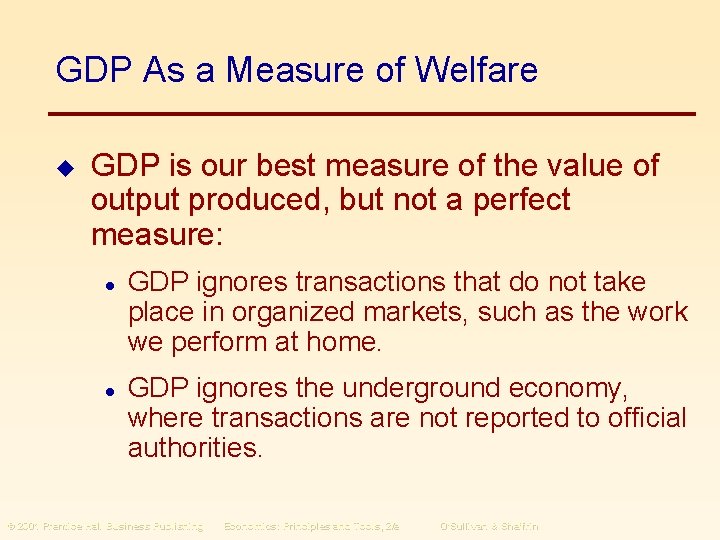

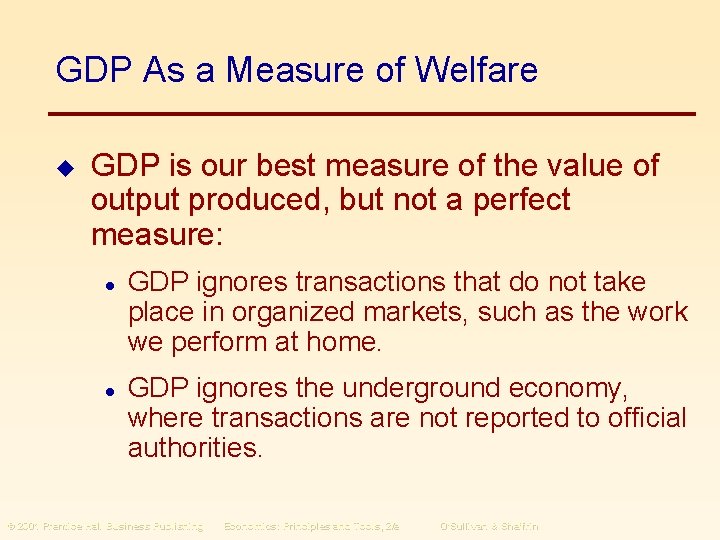

GDP As a Measure of Welfare u GDP is our best measure of the value of output produced, but not a perfect measure: l l GDP ignores transactions that do not take place in organized markets, such as the work we perform at home. GDP ignores the underground economy, where transactions are not reported to official authorities. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin

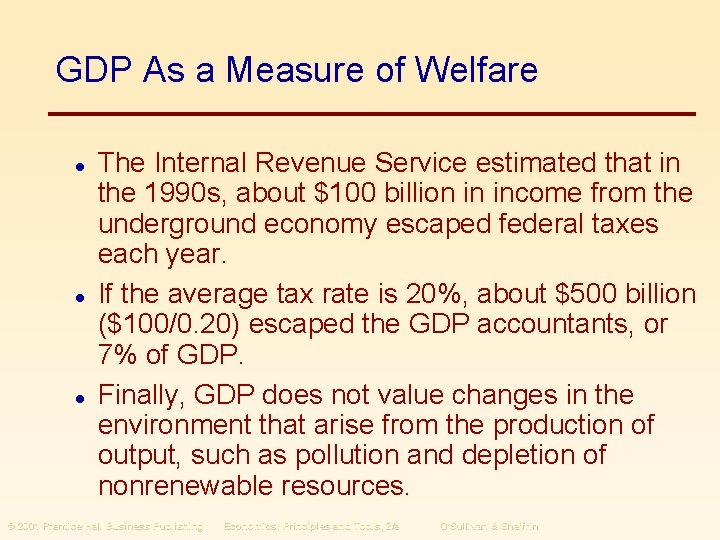

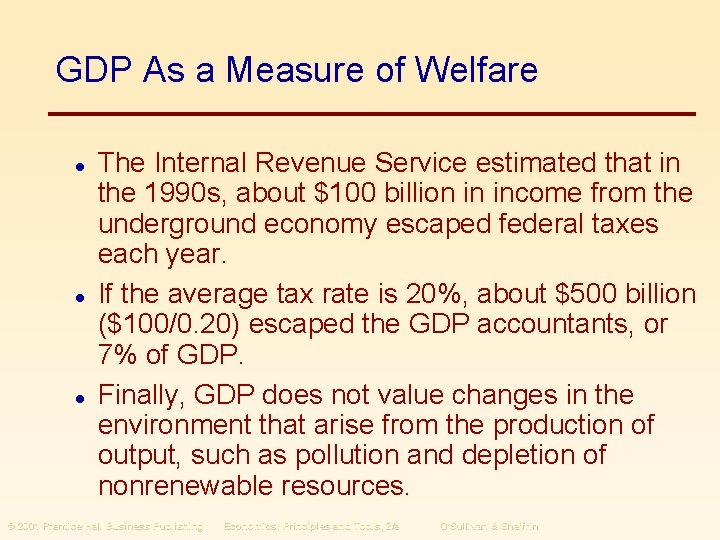

GDP As a Measure of Welfare l l l The Internal Revenue Service estimated that in the 1990 s, about $100 billion in income from the underground economy escaped federal taxes each year. If the average tax rate is 20%, about $500 billion ($100/0. 20) escaped the GDP accountants, or 7% of GDP. Finally, GDP does not value changes in the environment that arise from the production of output, such as pollution and depletion of nonrenewable resources. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics: Principles and Tools, 2/e O’Sullivan & Sheffrin