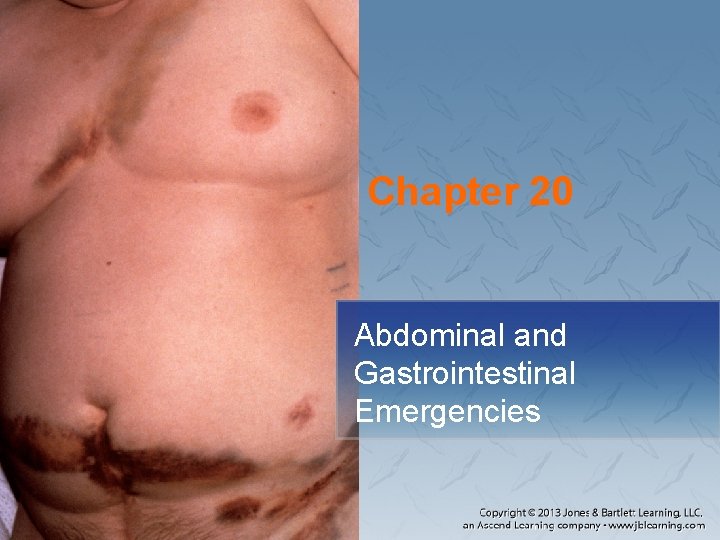

Chapter 20 Abdominal and Gastrointestinal Emergencies National EMS

Chapter 20 Abdominal and Gastrointestinal Emergencies

National EMS Education Standard Competencies Medicine Integrates assessment findings with principles of epidemiology and pathophysiology to formulate a field impression and implement a comprehensive treatment/disposition plan for a patient with a medical complaint.

National EMS Education Standard Competencies Abdominal and Gastrointestinal Disorders Anatomy, presentations, and management of shock associated with abdominal emergencies − Gastrointestinal bleeding

National EMS Education Standard Competencies Abdominal and Gastrointestinal Disorders Anatomy, physiology, epidemiology, pathophysiology, psychosocial impact, presentations, prognosis, and management of − − − Acute and chronic gastrointestinal hemorrhage Liver disorders Peritonitis Ulcerative diseases Irritable bowel syndrome

National EMS Education Standard Competencies Abdominal and Gastrointestinal Disorders Anatomy, physiology, epidemiology, pathophysiology, psychosocial impact, presentations, prognosis, and management of − − Inflammatory disorders Pancreatitis Bowel obstruction Hernias

National EMS Education Standard Competencies Abdominal and Gastrointestinal Disorders Anatomy, physiology, epidemiology, pathophysiology, psychosocial impact, presentations, prognosis, and management of − − − Infectious diseases Gallbladder and biliary tract disorders Rectal abscesses Rectal foreign body obstruction Mesenteric ischemia

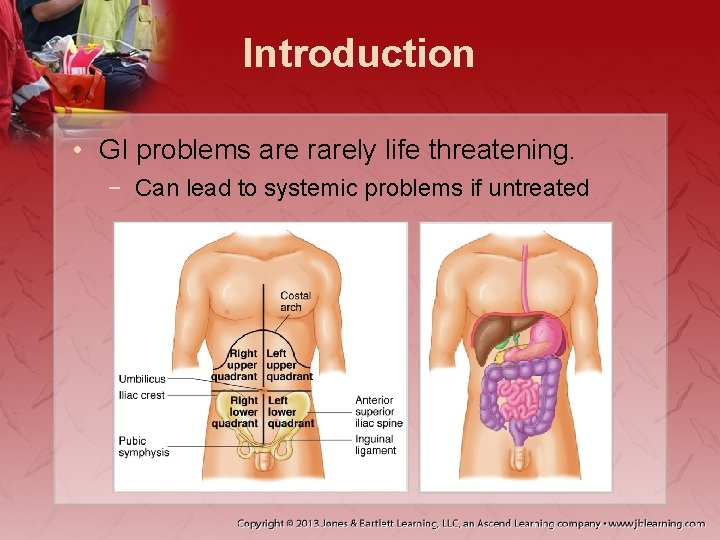

Introduction • GI problems are rarely life threatening. − Can lead to systemic problems if untreated

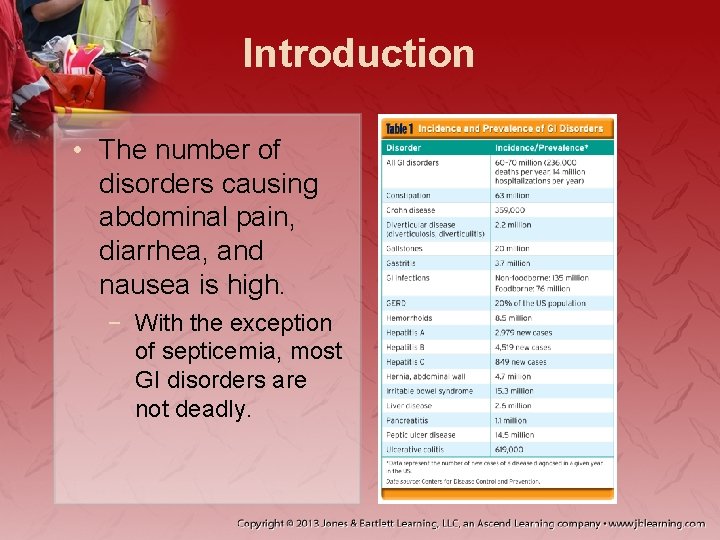

Introduction • The number of disorders causing abdominal pain, diarrhea, and nausea is high. − With the exception of septicemia, most GI disorders are not deadly.

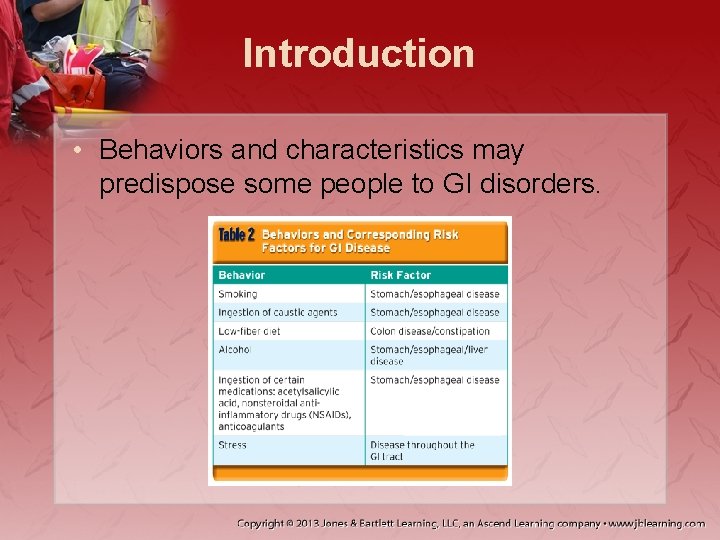

Introduction • Behaviors and characteristics may predispose some people to GI disorders.

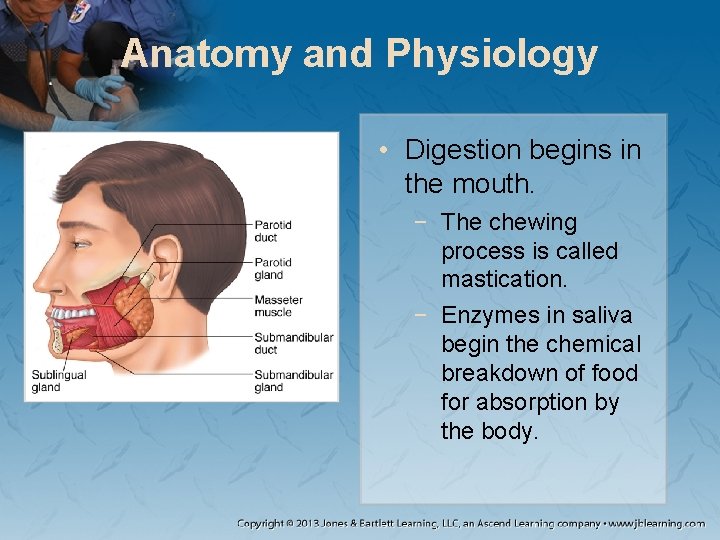

Anatomy and Physiology • Digestion begins in the mouth. − The chewing process is called mastication. − Enzymes in saliva begin the chemical breakdown of food for absorption by the body.

Anatomy and Physiology • Food reaches the esophagus. − Typically collapsed, allowing air to flow into the lungs instead of the stomach − Dilates when food or liquid travels through it • Explains gastric distention during positive-pressure ventilation

Anatomy and Physiology • The esophagus transports food using peristalsis. • The portal vein is intertwined around the esophagus. − Transports venous blood to the liver.

Anatomy and Physiology • Food travels through the diaphragm to the cardiac sphincter. − Connects the esophagus and the stomach − Controls amount of food that moves up the esophagus

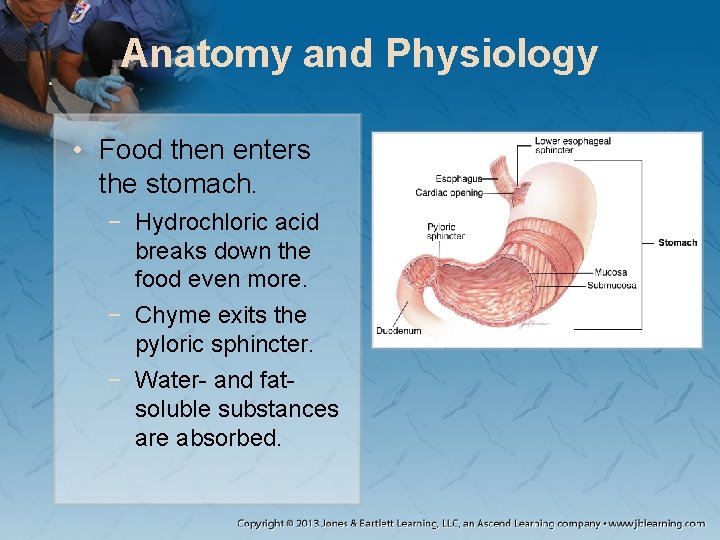

Anatomy and Physiology • Food then enters the stomach. − Hydrochloric acid breaks down the food even more. − Chyme exits the pyloric sphincter. − Water- and fatsoluble substances are absorbed.

Anatomy and Physiology • The main function of the GI system is to absorb the digested food. − The duodenum connects the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas to the digestive system. − The pancreas secretes enzymes to assist with digestion and neutralize gastric acid.

Anatomy and Physiology • The liver: − − − Produces bile, which breaks down fats Promotes carbohydrate metabolism Detoxifies drugs Completes the breakdown of dead blood cells Stores vitamins and minerals

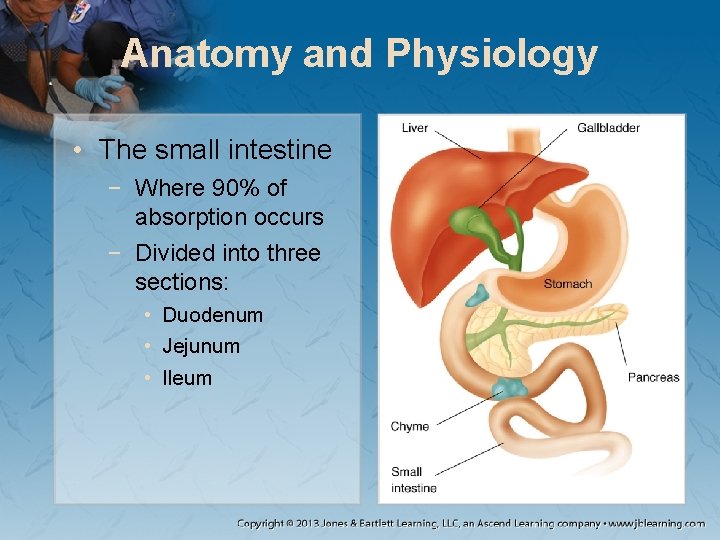

Anatomy and Physiology • The small intestine − Where 90% of absorption occurs − Divided into three sections: • Duodenum • Jejunum • Ileum

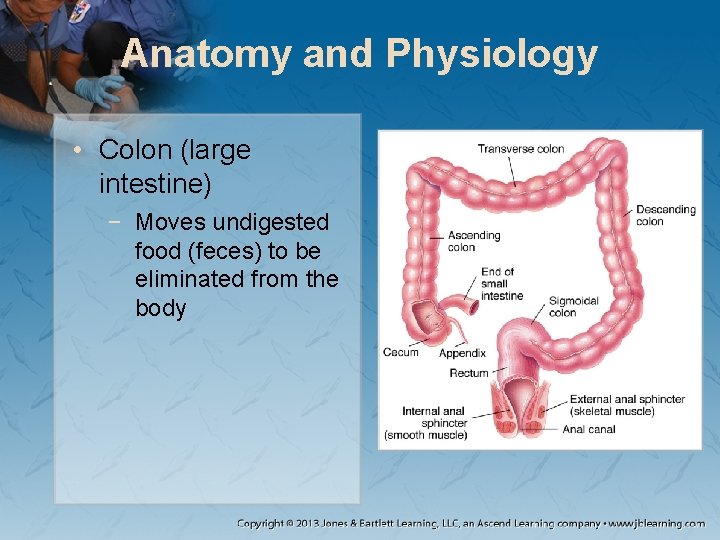

Anatomy and Physiology • Colon (large intestine) − Moves undigested food (feces) to be eliminated from the body

Anatomy and Physiology • The main role of the large intestine is to complete the reabsorption of water. • Bacterial digestion also occurs in the colon. • The journey from mouth to anus takes 8 to 72 hours.

Scene Size-Up • Ensure safety. • Look for MOI or NOI. • Take standard precautions. • Always have equipment for hygiene.

Primary Assessment • Form a general impression. − Where was the patient found? − What is the patient’s body posture? − Is there an odor?

Primary Assessment • Airway and breathing − − Patient who is vomiting may aspirate. Open the airway with the appropriate method. Remove or suction obstructions. Check for unusual odors

Primary Assessment • Circulation − − Assess skin color, temperature, and moisture. Determine pulse rate. Ensure blood pressure reading is accurate. Take note of amount of blood.

Primary Assessment • Transport decision − Based on primary assessment − If positive orthostatic vital signs, carefully consider how to move the patient. − Choose the mode of ambulance.

History Taking • Patients may have a history of issues. − SAMPLE helps you gather information. • Changes in bowel patterns or stool • Onset of diarrhea, constipation, or nausea/vomiting • Recent weight loss • Patient’s last meal

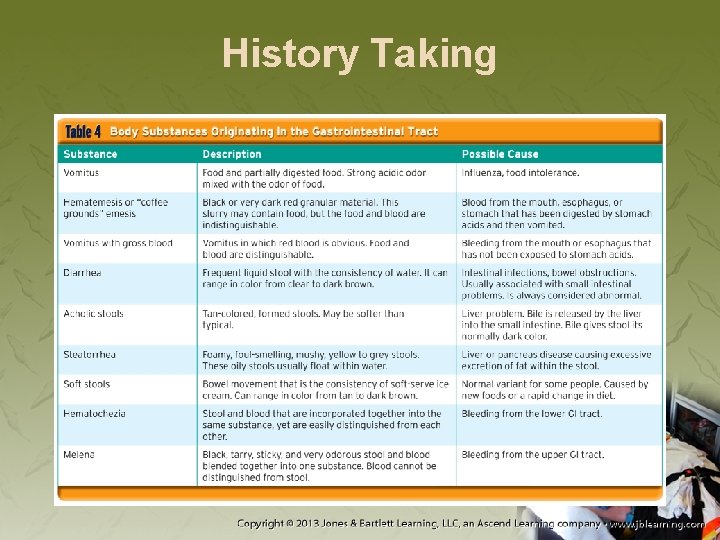

History Taking

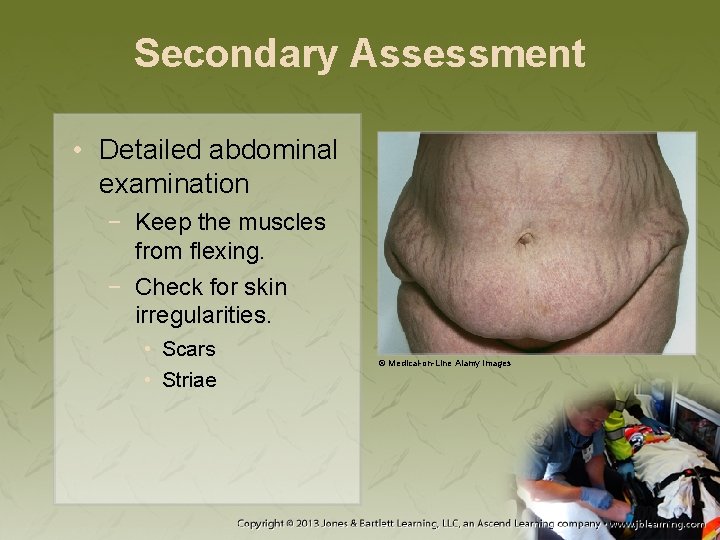

Secondary Assessment • Detailed abdominal examination − Keep the muscles from flexing. − Check for skin irregularities. • Scars • Striae © Medical-on-Line Alamy Images

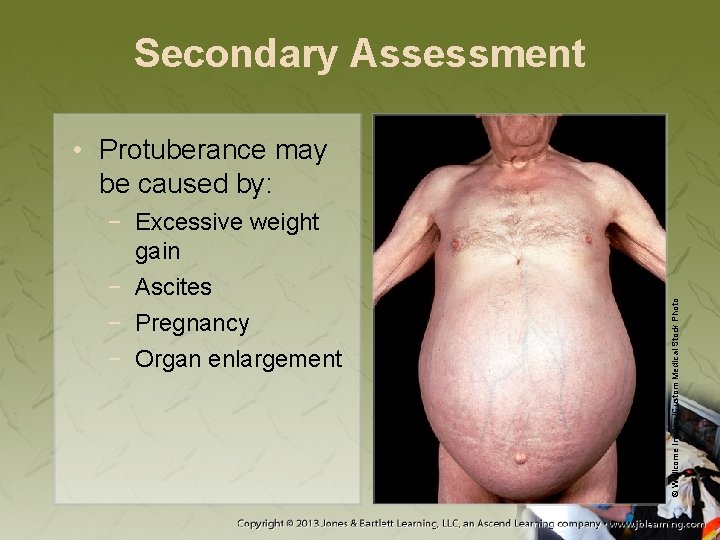

Secondary Assessment • Asymmetric abdomen could mean: − − Tumors Hernia Enlarged organs Pregnancy • Check shape of the abdomen.

Secondary Assessment − Excessive weight gain − Ascites − Pregnancy − Organ enlargement © Wellcome Images/Custom Medical Stock Photo • Protuberance may be caused by:

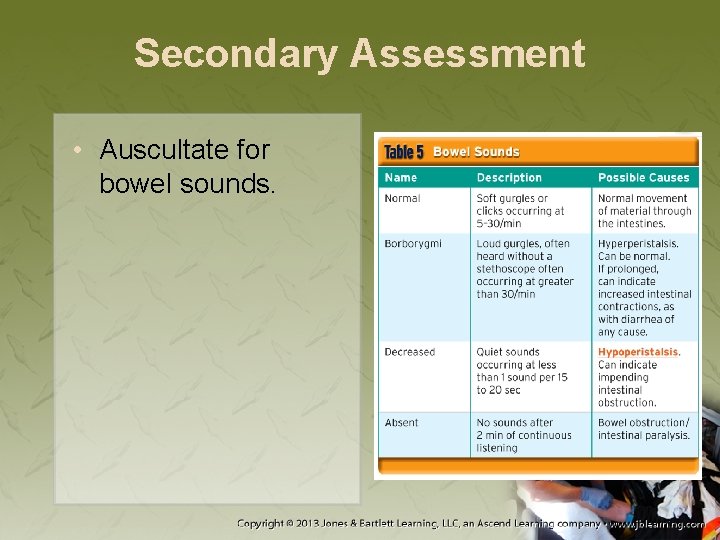

Secondary Assessment • Auscultate for bowel sounds.

Secondary Assessment • Percuss the abdomen. − The abdomen should sound tympanic. − The upper left and upper right quadrants will sound duller.

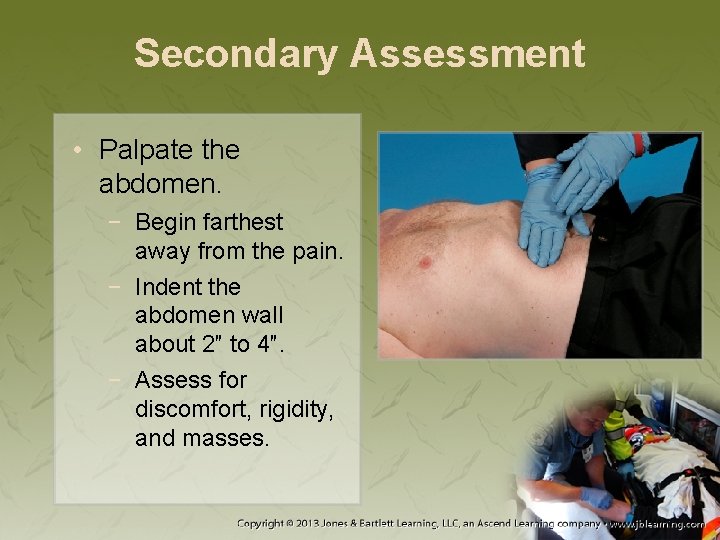

Secondary Assessment • Palpate the abdomen. − Begin farthest away from the pain. − Indent the abdomen wall about 2″ to 4″. − Assess for discomfort, rigidity, and masses.

Secondary Assessment • Abdominal pain may indicate: − − − Trauma Hemorrhage Infection Obstruction Other serious problems • Types of pain include: − Visceral pain − Parietal pain (rebound) − Somatic pain − Referred pain

Secondary Assessment • Rebound tenderness occurs when the peritoneum is irritated. − Once a tender area is found: • Depress the skin with your fingertips 2" to 4". • Quickly pull your fingers off the abdomen. − An alternative is the Markle heel drop test.

Secondary Assessment • If there is pain in the right upper quadrant, use Murphy sign to assess for cholecystitis. − − Ask the patient to breathe out. Palpate deeply along the upper right quadrant. Ask the patient to inhale deeply. Sharp increase in pain: positive Murphy sign

Secondary Assessment • Obtain orthostatic vital signs. − Determine the blood pressure and pulse rate. • Have the patient change positions and retake. − Significant blood loss may be indicated by: • 10 -mm Hg drop in blood pressure • 10 -beat increase in pulse rate

Secondary Assessment • Many GI diseases affect electrolyte levels. − Use a handheld blood analyzer to test. • Ultrasonography and intra-abdominal pressure testing may also be available.

Reassessment • Routine monitoring includes: − − − Pulse rate Electrocardiogram Blood pressure Respiratory rate Pulse oximetry

Reassessment • Pain medication includes: − − − Meperidine hydrochloride Morphine Ketorolac Nalbuphine Fentanyl

Reassessment • Nausea medications include: − − Ondansetron Diphenhydramine Hydroxyzine Promethazine

Emergency Medical Care • Repeat assessment if patient’s condition suddenly changes dramatically. • Do not let patients eat or drink anything.

Airway Management • Airway concerns include possible aspiration or obstruction due to blood or vomitus. − Place patient so material can drain from mouth. • Make sure suction equipment is available. • You may need to use a nasogastric tube.

Breathing • Associated with decreased hemoglobin levels − Administer high-concentration oxygen. − Prevent aspiration. − Auscultate lung sounds.

Circulation • Concerns: dehydration and hemorrhage − Fluids depend on circulatory perfusion status. • Hypotonic solution for stable conditions • Isotonic solution for profound dehydration

Circulation • Hemorrhaging care should be directed at maintaining perfusion of vital organs. − Titrate fluids to a blood pressure of 90 to 100 mm Hg. − If blood pressure cannot be maintained, vasoactive medications may be needed.

Specific Abdominal and Gastrointestinal Emergencies • The paramedic must have an understanding of many conditions. − In the future, paramedics may be asked to help determine where a patient should be directed. − The more you understand, the more you can educate patients.

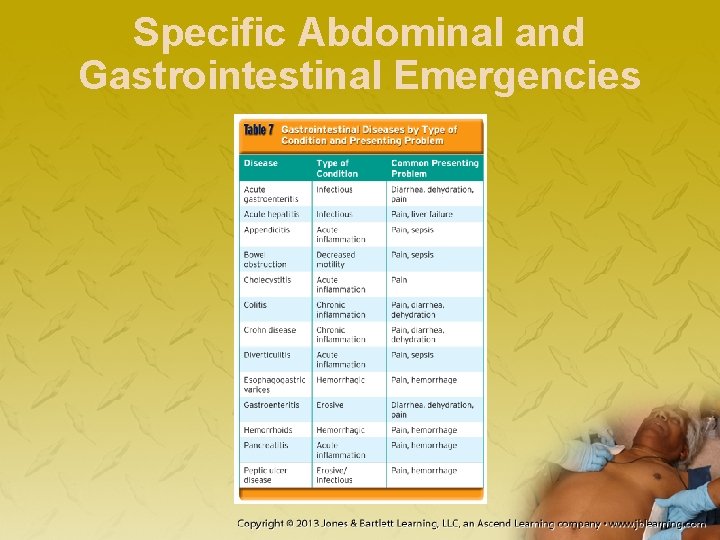

Specific Abdominal and Gastrointestinal Emergencies

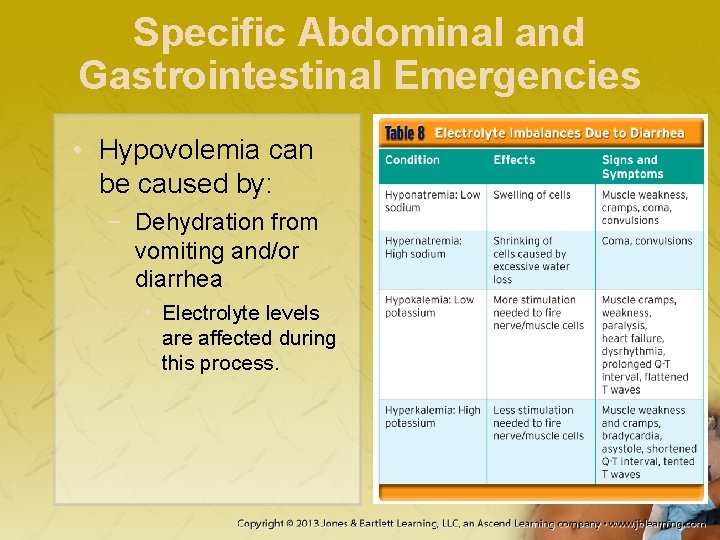

Specific Abdominal and Gastrointestinal Emergencies • Hypovolemia can be caused by: − Dehydration from vomiting and/or diarrhea • Electrolyte levels are affected during this process.

Specific Abdominal and Gastrointestinal Emergencies • Hypovolemia can be caused by (cont’d): − Hemorrhage • Potential to be fatal • Signs of shock are typically present. • Drop in blood pressure indicates significant volume loss

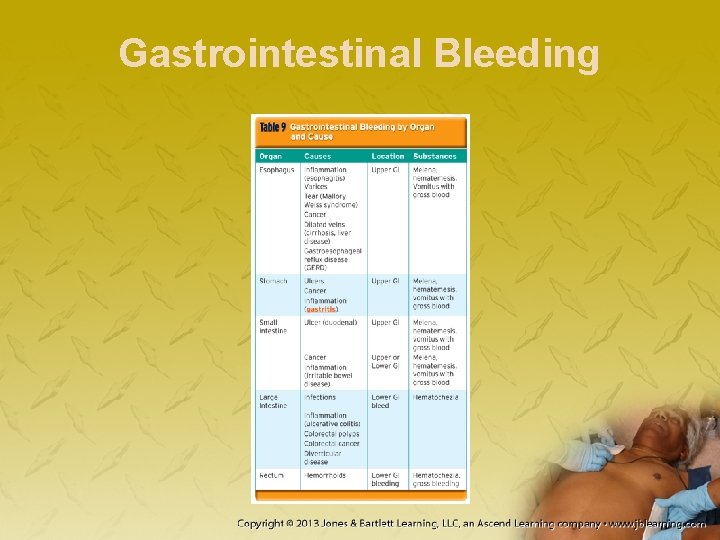

Gastrointestinal Bleeding • GI bleeding is a symptom, not the disease. − Determine onset and medical history. − Treatment includes: • Fluid resuscitation • Establish an IV line.

Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Esophagogastric Varices • Pathophysiology − Caused by pressure increases in blood vessels surrounding the esophagus and stomach − Blood cannot easily flow through damaged liver. • Blood backs up into the portal vessels.

Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Esophagogastric Varices • Assessment − Initial presentation • Fatigue • Jaundice • Anorexia • Pruritus • Abdominal pain − When the varices rupture: • Abrupt discomfort in the throat • Severe dysphagia • Vomiting bright red blood • Signs of shock

Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Esophagogastric Varices • Management − General management guidelines • Accurate assessment of blood loss − In-hospital treatment includes: • Stopping the bleeding • Aggressive fluid resuscitation • Possible endoscopy

Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Mallory-Weiss Syndrome • Pathophysiology − Junction between the esophagus and the stomach tears • Generally due to severe vomiting

Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Mallory-Weiss Syndrome • Assessment − Bleeding may be light to severe. − In extreme cases, patients will have: • • Signs and symptoms of shock Epigastric abdominal pain Hematemesis Melena

Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Mallory-Weiss Syndrome • Management − Aimed at determining the extent of blood loss − In-hospital management may include: • Volume resuscitation • Endoscopy • Attempt to repair the tear

Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Peptic Ulcer Disease (PUD) • Pathophysiology − Erosion of the mucous that lines the stomach and duodenum − Typically occurs over weeks, months, or years − Variety of causes • Infection with Helicobacter pylori • Erosive gastritis

Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Peptic Ulcer Disease (PUD) • Assessment − Burning or gnawing pain in the stomach • Disappears after eating, but returns hours later − Other common symptoms may include: • Vomiting • Belching • Heartburn

Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Peptic Ulcer Disease (PUD) • Management − Assess blood loss and manage hypotension. − Monitor orthostatic vital signs. − In-hospital management includes: • Acid neutralization • Reduction therapies • Endoscopy if needed

Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease • Pathophysiology − Sphincter between the esophagus and stomach opens, allowing stomach acids to travel up − Can cause a burning sensation within the chest − Over time it can cause damage to the esophageal wall and possible bleeding.

Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease • Assessment − Signs and symptoms • Heartburn • Coughing or difficulty swallowing • Bleeding, resulting in hematemesis and melena

Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease • Management − Treatment focuses on decreasing acidity. • Antacids, proton pump inhibitors, H 2 blockers − Symptoms can be confused with myocardial infarction.

Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Hemorrhoids • Pathophysiology − Swelling and inflammation of blood vessels around the rectum − Caused by increased rectal pressure or irritation

Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Hemorrhoids • Assessment − Signs and symptoms: • Hematochezia • Rectal itching • Small mass on rectum

Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Hemorrhoids • Management − − Prehospital management is supportive. Obtain orthostatic vital signs. In-hospital management may include creams. Prevention includes eating a high-fiber diet.

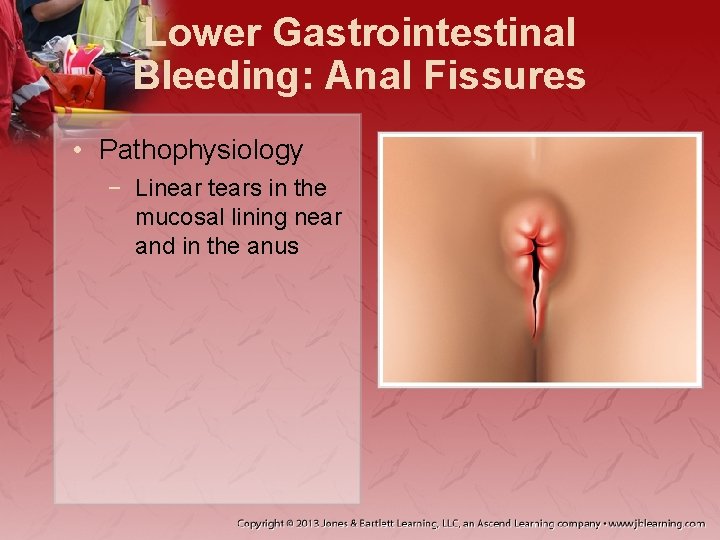

Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Anal Fissures • Pathophysiology − Linear tears in the mucosal lining near and in the anus

Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Anal Fissures • Assessment − Painful defecation • Management − Place dressing over anus. − Do NOT pack fissure or anus.

Acute Inflammatory Conditions • Inflammation helps white blood cells destroy or seal off an invading agent. • Localized inflammation will cause localized signs and symptoms.

Acute Inflammatory Conditions • If bacteria moves into the bloodstream, sepsis occurs. − The body responds with a generalized inflammatory response. − Autoimmune condition: the body attacks and kills its own cells for no defined reason.

Cholecystitis and Biliary Tract Disorders • Pathophysiology − Inflammation of the gallbladder • • Choleangitis—inflammation of bile duct Cholelithiasis—stones in the gallbladder Cholecystitis—inflammation of the gallbladder Acalculus cholecystitis—inflammation without gallstones

Cholecystitis and Biliary Tract Disorders • Pathophysiology (cont’d) − May arise from decreased flow of biliary materials − Patient may present with: • Murphy sign • Nausea/vomiting • Jaundice

Cholecystitis and Biliary Tract Disorders • Assessment − After eating a fatty meal, severe upper right quadrant abdominal pain develops. • Management − Pain medications: meperidine and morphine − Medication for nausea is often necessary.

Appendicitis • Pathophysiology − Fecal and other matter builds up in appendix. − Build-up of pressure will eventually cause the organ to rupture, resulting in: • Peritonitis • Sepsis • Death

Appendicitis • Assessment − Stages of presentation • Early—periumbilical pain, nausea, vomiting • Ripe—pain in lower right quadrant • Rupture—decrease in pain (decrease in pressure) − Evaluate for peritonitis with Dunphy sign.

Appendicitis • Management − Assess for septicemia. − Volume resuscitation • Use dopamine if crystalloids are not effective. − Administer pain and antinausea medications.

Diverticulitis • Pathophysiology − Diverticulum: weak area in the colon that begins to have pockets (diverticula) − Diverticulosis: condition of having diverticula − Diverticulitis: Inflammation of diverticuli

Diverticulitis • Pathophysiology − A diet low in fiber creates more solid stool. − If feces gets trapped in diverticula, inflammation and infection occur and may cause: • Scarring • Adhesions • Fistula

Diverticulitis • Assessment − Signs and symptoms include: • Abdominal pain, usually localized on the left lower abdomen • Classic infection signs • Constipation or diarrhea

Diverticulitis • Management − Ensure severe infection is not present. − Patients may need fluids and/or dopamine. − In-hospital treatment includes: • Antibiotics • Liquid diet • Surgery

Pancreatitis • Pathophysiology − Inflammation of the pancreas − Occurs when the tube carrying enzymes becomes blocked, leading to autodigestion − Can occur suddenly or over many months − May be single or episodic attacks

Pancreatitis • Assessment − Signs and symptoms may include: • Sharp pain in the epigastric area or right upper abdomen • Pain radiating to the back • Muscle spasms

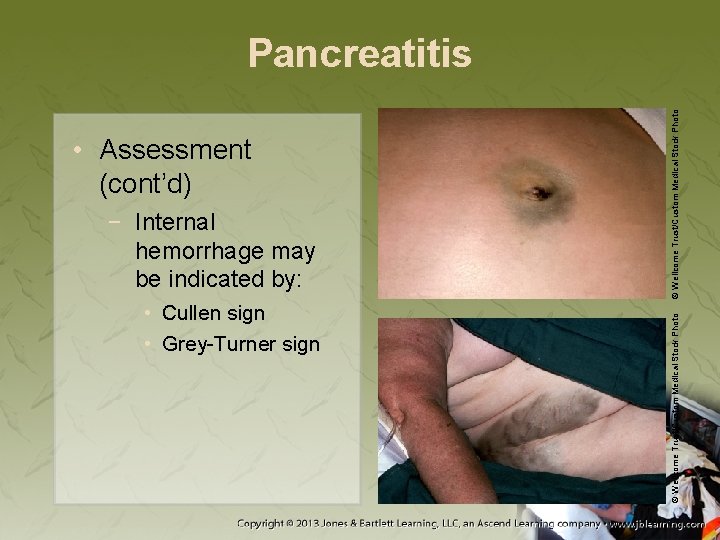

− Internal hemorrhage may be indicated by: • Cullen sign • Grey-Turner sign © Wellcome Trust/Custom Medical Stock Photo • Assessment (cont’d) © Wellcome Trust/Custom Medical Stock Photo Pancreatitis

Pancreatitis • Management − Directed by general management guidelines − Assess for signs of severe hemorrhage. − Meperidine is the choice for pain management.

Ulcerative Colitis • Pathophysiology − Generalized inflammation of the colon − Causes a thinning of the intestinal wall and a weakened rectum − Peaks between ages 15 and 25 years and 55 and 65 years

Ulcerative Colitis • Assessment − Signs and symptoms may include: • • Gradual onset of bloody diarrhea Hematochezia Mild to severe abdominal pain Skin lesions

Ulcerative Colitis • Management − Determine the degree of hemodynamic instability. − Administer fluids, if necessary. − Follow the general management guideline.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) • Pathophysiology − Patients often show: • Hypersensitivity of bowel pain receptors • Hyperresponsiveness of the smooth muscle • Psychiatric disorder connection

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) • Pathophysiology (cont’d) − Hyperresponsiveness can cause spasm. • Can cause constipation and bloating or diarrhea − Typically begins during childhood − Can be triggered by various stimuli

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) • Assessment − You will typically be called when the patient is having a flare-up of symptoms. • Management − Mainly supportive − Assessment should include the patient’s mood.

Crohn Disease • Pathophysiology − Involves the entire GI tract − A series of attacks leaves a scarred, narrowed, and weakened portion of the small intestine. • Can cause bowel obstruction

Crohn Disease • Assessment − Signs and symptoms may include: • Rectal bleeding • Weight loss • Skin disorders

Crohn Disease • Management − Prehospital care should focus on general management guidelines, including: • Volume resuscitation • Control of nausea and pain

Acute Infectious Conditions • GI infection occurs when contaminated food is ingested or when the GI tract ruptures. − People that have a difficulty combating infection: • Immunocompromised • Very old • Very young

Acute Infectious Conditions • Damage may allow contents to be released into surrounding tissues. − The body will begin to defend itself. − If the infection continues, it may leave the GI system and enter the bloodstream. • This is known as sepsis.

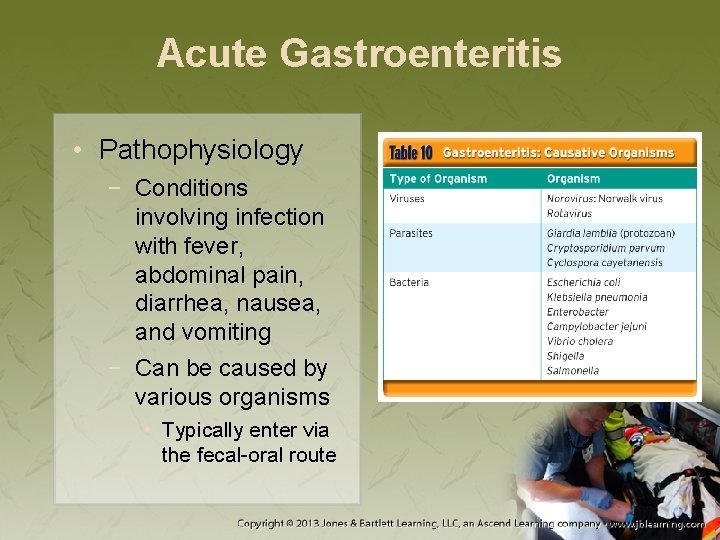

Acute Gastroenteritis • Pathophysiology − Conditions involving infection with fever, abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting − Can be caused by various organisms • Typically enter via the fecal-oral route

Acute Gastroenteritis • Assessment − Symptoms may show anywhere from several hours to several days from contact − Can last two or three days, or several weeks

Acute Gastroenteritis • Assessment (cont’d) − Signs and symptoms may include: • Diarrhea of various types • Nausea and vomiting • Anorexia − Assess for dehydration, hemodynamic instability, and electrolyte imbalance.

Acute Gastroenteritis • Management − − Determine the degree of fluid deficit. Obtain orthostatic vital signs. Analgesic and antiemetic medications Teach patients about safe food and water use.

Rectal Abscess • Pathophysiology − Caused when the ducts carrying mucus to the rectal area become blocked • Allows bacteria to grow and spread to the anus

Rectal Abscess • Assessment − Symptoms may include: • Rectal pain that increases with defecation • Rectal drainage • Constipation • Management − Focus on keeping the patient comfortable.

Liver Disease: Cirrhosis • Pathophysiology − Early liver failure, which may be hallmarked by: • Portal hypertension • Deficiencies with coagulation • Diminished detoxification

Liver Disease: Cirrhosis • Assessment − First stage may include: • • Weakness and fatigue Nausea and vomiting Anorexia Pruritus

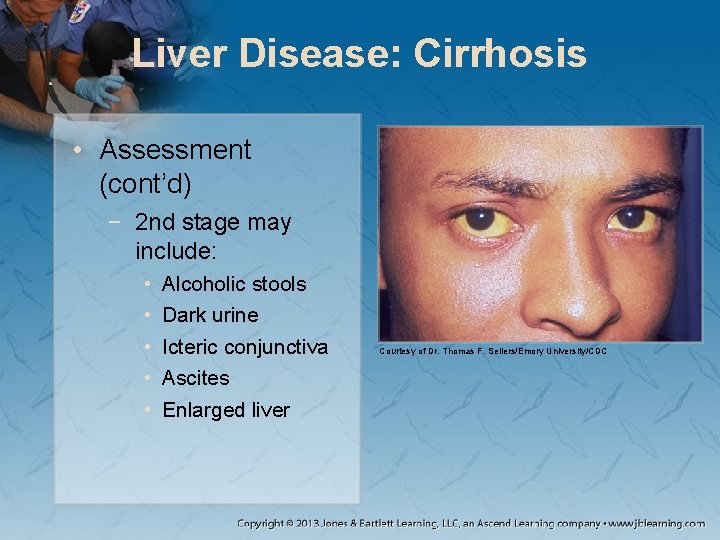

Liver Disease: Cirrhosis • Assessment (cont’d) − 2 nd stage may include: • • • Alcoholic stools Dark urine Icteric conjunctiva Ascites Enlarged liver Courtesy of Dr. Thomas F. Sellers/Emory University/CDC

Liver Disease: Cirrhosis • Assessment (cont’d) − Common blood tests: • • Aminotransferases Alkaline phosphatase Albumin Bilirubin

Liver Disease: Cirrhosis • Management − Prehospital care should be supportive. − Involves bleeding control and medication − Use lower ends of medication dose range.

Liver Disease: Hepatic Encephalopathy • Pathophysiology − Brain impairment due to diminished liver function − Underlying causes: • Increased levels of ammonia • Diminished cellular energy supplies • Change in blood-brain barrier permeability

Liver Disease: Hepatic Encephalopathy • Assessment − Can range from mild memory loss to coma − May be precipitated by: • • Infection Renal failure GI bleeding Constipation

Liver Disease: Hepatic Encephalopathy • Management − Mainly supportive − Ensure that LOC status is not from other cause. • Check blood glucose levels. • Assess for trauma and overdose. • Take a medical history.

Obstructive Conditions • Intestines are unable to move material through the digestive tract. − Two main reasons: • Paralysis of the intestines • Intestinal lumen diameter compromise

Small-Bowel Obstruction • Pathophysiology − Most often caused by post-operative adhesions − Other causes include: • • Cancer Crohn disease Hernias Foreign bodies

Small-Bowel Obstruction • Assessment − Signs and symptoms may include: • • Crampy and intermittent abdominal pain Initial diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting Increased pressure Constipation

Small-Bowel Obstruction • Management − Monitor blood pressure, and perform volume resuscitation. − Administer dopamine as needed. − Consider using a nasogastric tube. − Antiemetics are indicated.

Large-Bowel Obstruction • Pathophysiology − Caused by either mechanical obstruction or colon dilation − Imaging studies determine the location and extent of obstruction. • Once located, can be easily treated

Large-Bowel Obstruction • Assessment − Signs and symptoms may include: • • Nausea and vomiting Distended abdomen Absent bowel sounds Peritonitis signs if bowel has ruptured

Large-Bowel Obstruction • Management − Same as for small bowel obstruction

Hernia • Pathophysiology − Organ/structure protrusion into adjacent cavity − To check for an inguinal hernia: • Place fingers on lower abdomen. • Instruct patient to cough. • Weakness in abdominal wall will present as bulging.

Hernia • Pathophysiology (cont’d) − Caused by any condition that causes intraabdominal pressure: • • Obesity Standing for long periods Straining during bowel movements Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

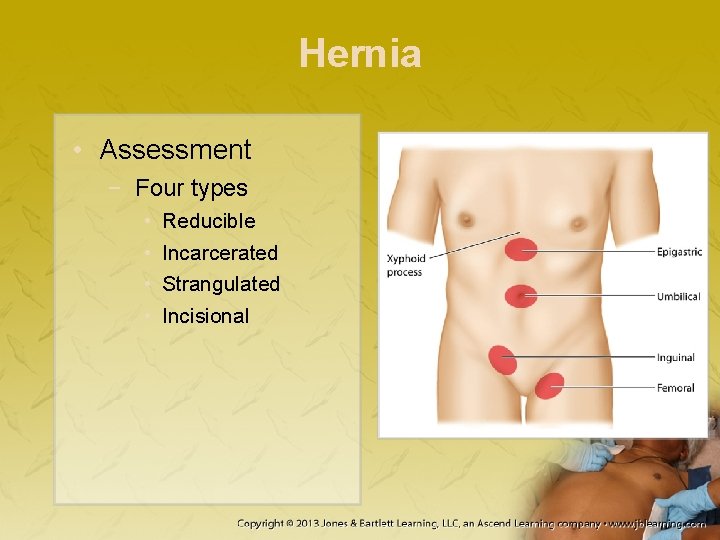

Hernia • Assessment − Four types • • Reducible Incarcerated Strangulated Incisional

Hernia • Management − Focus on supportive measures. − Pain management − Assess for sepsis

Rectal Foreign Body Obstruction • Pathophysiology − Originates from upper GI tract or anal insertion • Assessment − Presents with sudden rectal pain with defecation − Determine if the rectum has been perforated.

Rectal Foreign Body Obstruction • Management − Do NOT attempt to remove object. − Prehospital management should be limited to patient comfort. • Treat with analgesia if indicated. • Closely monitor vital signs.

Mesenteric Ischemia • Pathophysiology − Interruption of the blood supply to the mesentery − Can be caused by: • Arterial embolism • Thrombosis • Profound vasospasm

Mesenteric Ischemia • Assessment − Gradual or sudden onset − Symptoms include: • Severe pain with ill-defined location • Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea • Possible blood in stool

Mesenteric Ischemia • Management − − − Patients require rapid transportation. Monitor closely. Check vitals for signs of sepsis. Fluid resuscitation in cases of shock Give analgesics as needed.

Gastrointestinal Conditions in Pediatric Patients • GI complaints are common in children. − Prolonged vomiting, diarrhea, or bleeding can lead to severe changes in sodium and potassium levels.

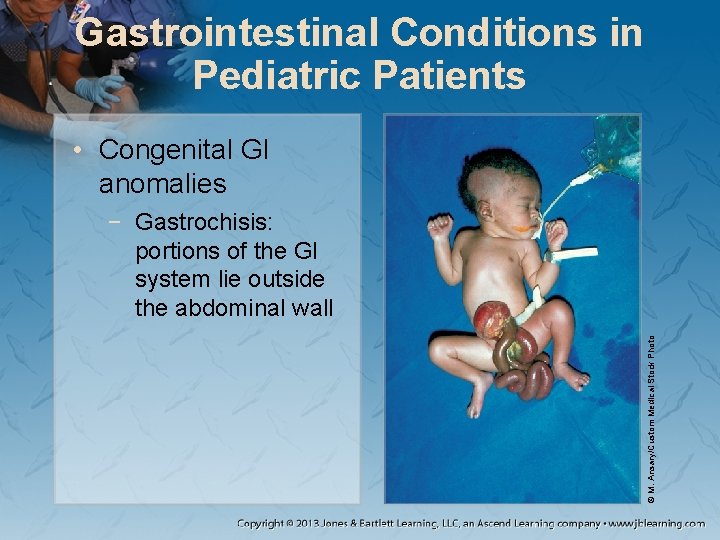

Gastrointestinal Conditions in Pediatric Patients • Congenital GI anomalies © M. Ansary/Custom Medical Stock Photo − Gastrochisis: portions of the GI system lie outside the abdominal wall

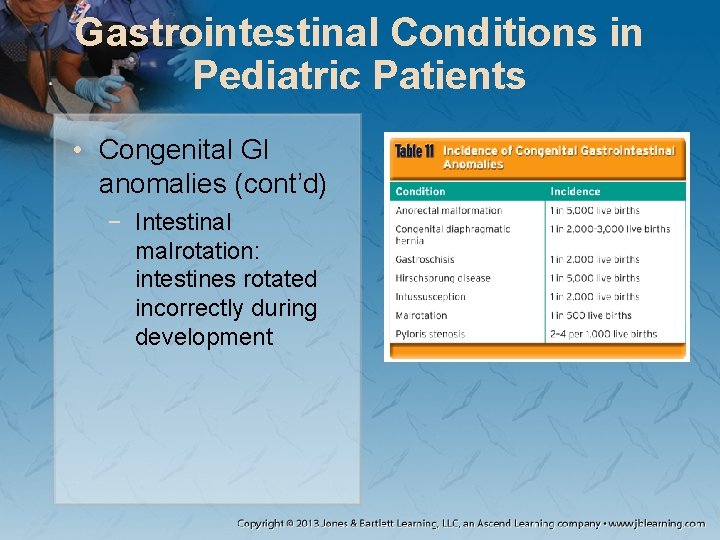

Gastrointestinal Conditions in Pediatric Patients • Congenital GI anomalies (cont’d) − Intestinal malrotation: intestines rotated incorrectly during development

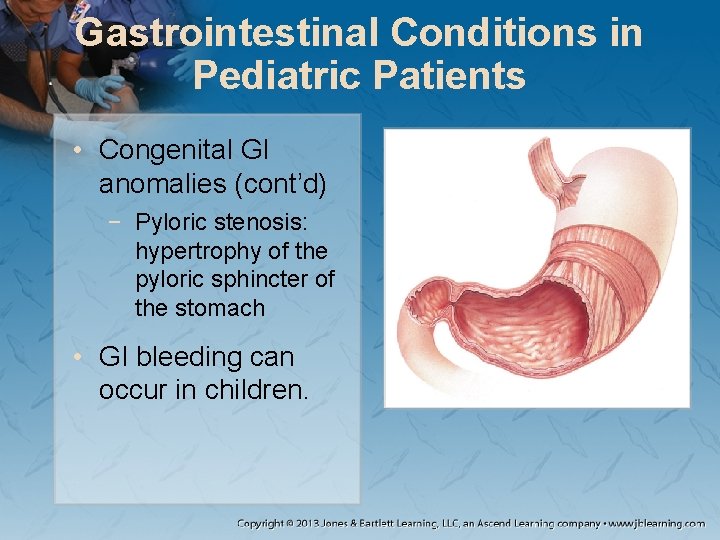

Gastrointestinal Conditions in Pediatric Patients • Congenital GI anomalies (cont’d) − Pyloric stenosis: hypertrophy of the pyloric sphincter of the stomach • GI bleeding can occur in children.

Gastrointestinal Conditions in Pediatric Patients • Careful assessment is critical. − Check skin turgor, pulse rate, and peripheral pulse status. − Severe fluid loss may cause diminished LOC. • Standard fluid resuscitation: 20 m. L/kg isotonic fluid − Get a detailed medical history from the parent.

Gastrointestinal Conditions in Pediatric Patients • Patients may have a gastrostomy tube. − If dislodged, place a sterile dressing over it. − If clogged, talk about ways to clear the tube. − If the blockage cannot be easily managed, turn off the feeding, clamp the tube, and transport.

Gastrointestinal Conditions in Older Adults • GI diseases more prevalent in older adults • Abdominal pain can also be a symptom of a cardiac condition. − Obtain a thorough history and physical exam. − Consider a 12 -lead ECG. − Monitor vital signs.

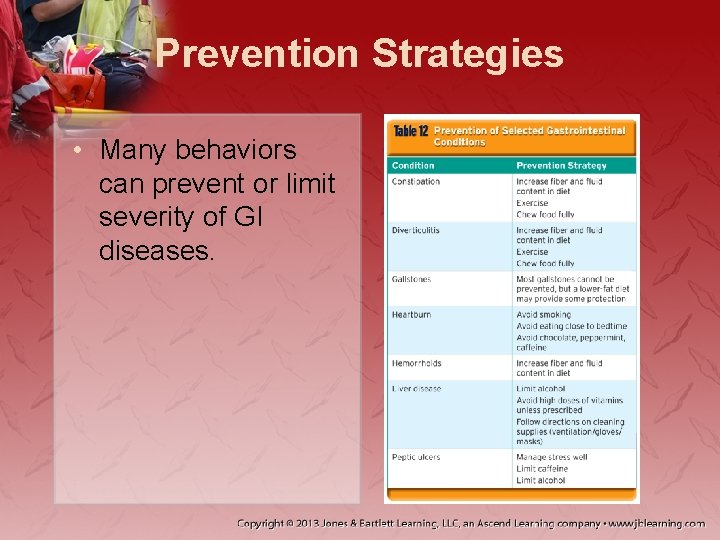

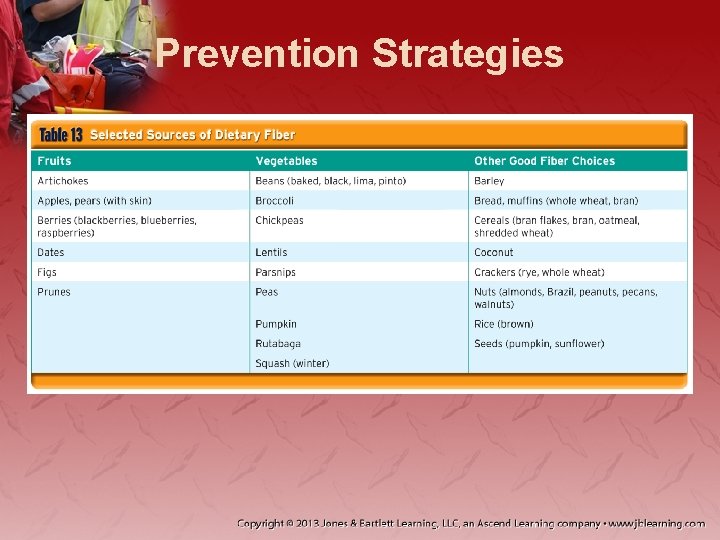

Prevention Strategies • Many behaviors can prevent or limit severity of GI diseases.

Prevention Strategies

Summary • GI illnesses are rarely life threatening, but systemic illnesses can occur if left untreated or undertreated. • The structures and functions of the GI system perform digestion, which begins in the mouth and ends in the anus. • It is likely you will come in contact with blood or other body fluids. A complete scene sizeup requires a survey of PPE.

Summary • Observe a patient presenting with GI symptoms to form a general impression. • Maintain airway and circulation; determine extent of bleeding. • Weigh patient stability and risk of injury when deciding on rapid transport. • The field impression and gathered information can determine cause of complaint.

Summary • The secondary assessment should include a physical examination. • Orthostatic vital sign changes of 10 -beat pulse rate increase and 10 -mm Hg drop in blood pressure is a likely sign of significant volume loss. • Reassess the patient by monitoring changes in condition.

Summary • Pain and nausea management can be given to most patients with GI emergencies. • Compassionate care and clear documentation are essential parts of delivering excellent patient care. • Perform new assessments and examinations if patient condition changes.

Summary • Perform airway management if necessary. • If circulation is compromised by dehydration or hemorrhage, fluid resuscitation is essential. • Paramedics must understand GI diseases to educate patients and to perform an increasing level of responsibilities.

Summary • The four major conditions responsible for abdominal and GI emergencies are: − − Hypovolemia Acute or chronic inflammation Infection Obstruction

Summary • GI tract bleeding is a symptom and can reflect many GI diseases. • Pediatric patients face special challenges because of their size, physiology, and possible GI congenital anomalies. • Treating older adults with GI emergencies is complicated by comorbidities, multiple medications, and other factors.

Credits • Chapter opener: © Wellcome Trust/Custom Medical Stock Photo • Backgrounds: Blue—Jones & Bartlett Learning. Courtesy of MIEMSS; Gold—Jones & Bartlett Learning. Courtesy of MIEMSS; Red—© Margo Harrison/Shutter. Stock, Inc. ; Green—Courtesy of Rhonda Beck • Unless otherwise indicated, all photographs and illustrations are under copyright of Jones & Bartlett Learning, courtesy of Maryland Institute for Emergency Medical Services Systems, or have been provided by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

- Slides: 142