Chapter 2 Relational Model Database Web Engineering Lab

Chapter 2: Relational Model Database & Web Engineering Lab. Faculty of Computer and Multimedia Dongguk University Database System Concepts, 5 th Ed. ©Silberschatz, Korth and Sudarshan See www. db-book. com for conditions on re-use 1

Chapter 2: Relational Model n Structure of Relational Databases n Fundamental Relational-Algebra-Operations n Additional Relational-Algebra-Operations n Extended Relational-Algebra-Operations n Null Values n Modification of the Database

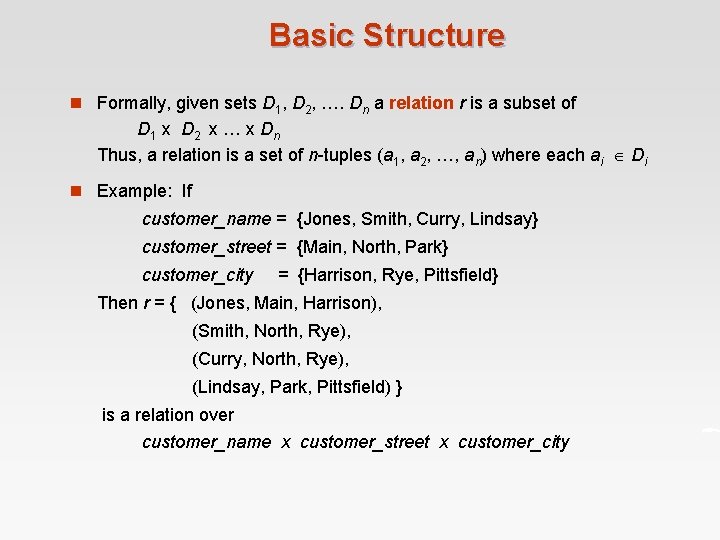

Basic Structure n Formally, given sets D 1, D 2, …. Dn a relation r is a subset of D 1 x D 2 x … x Dn Thus, a relation is a set of n-tuples (a 1, a 2, …, an) where each ai Di n Example: If customer_name = {Jones, Smith, Curry, Lindsay} customer_street = {Main, North, Park} customer_city = {Harrison, Rye, Pittsfield} Then r = { (Jones, Main, Harrison), (Smith, North, Rye), (Curry, North, Rye), (Lindsay, Park, Pittsfield) } is a relation over customer_name x customer_street x customer_city

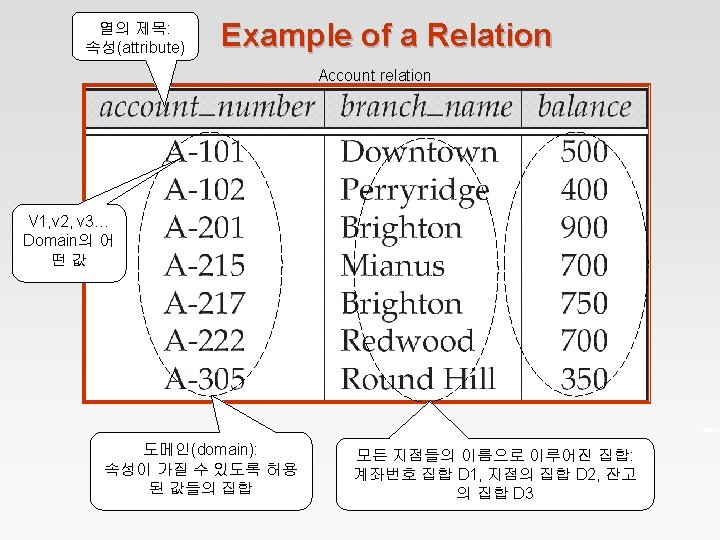

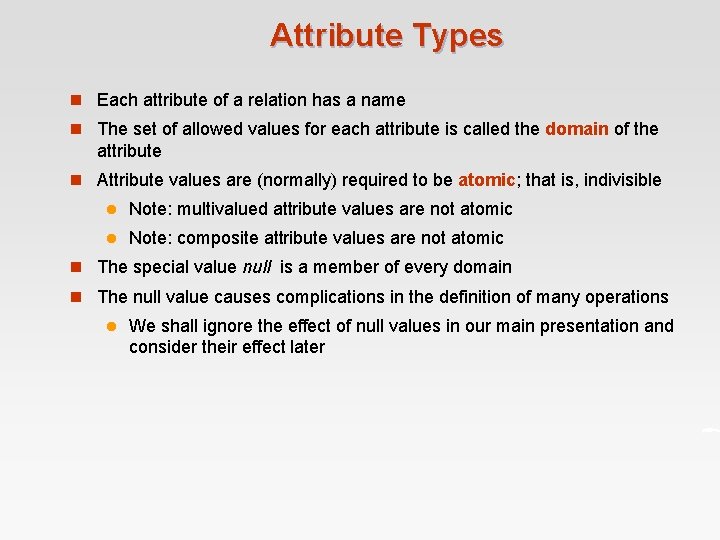

Attribute Types n Each attribute of a relation has a name n The set of allowed values for each attribute is called the domain of the attribute n Attribute values are (normally) required to be atomic; that is, indivisible l Note: multivalued attribute values are not atomic l Note: composite attribute values are not atomic n The special value null is a member of every domain n The null value causes complications in the definition of many operations l We shall ignore the effect of null values in our main presentation and consider their effect later

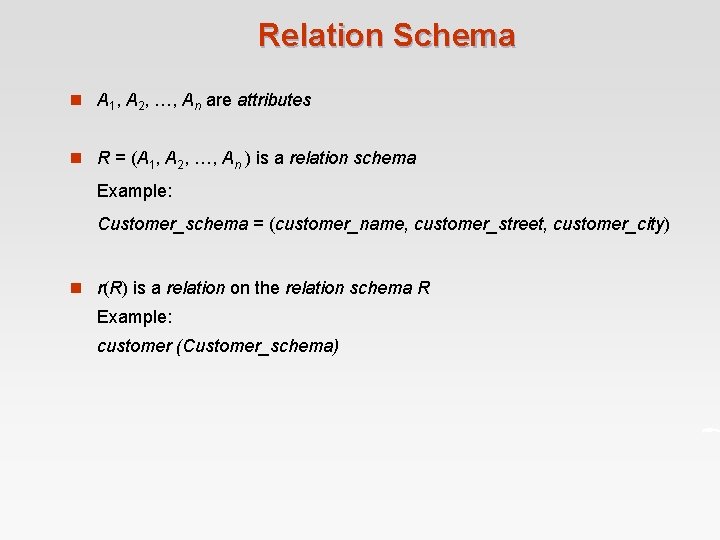

Relation Schema n A 1, A 2, …, An are attributes n R = (A 1, A 2, …, An ) is a relation schema Example: Customer_schema = (customer_name, customer_street, customer_city) n r(R) is a relation on the relation schema R Example: customer (Customer_schema)

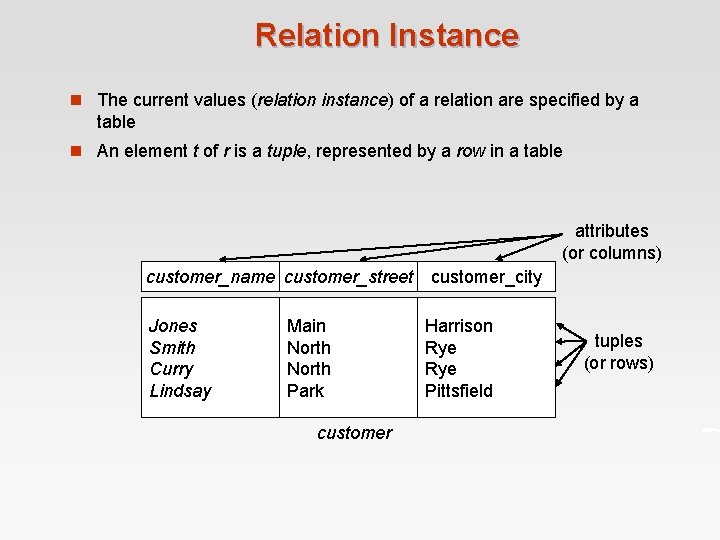

Relation Instance n The current values (relation instance) of a relation are specified by a table n An element t of r is a tuple, represented by a row in a table attributes (or columns) customer_name customer_street Jones Smith Curry Lindsay Main North Park customer_city Harrison Rye Pittsfield tuples (or rows)

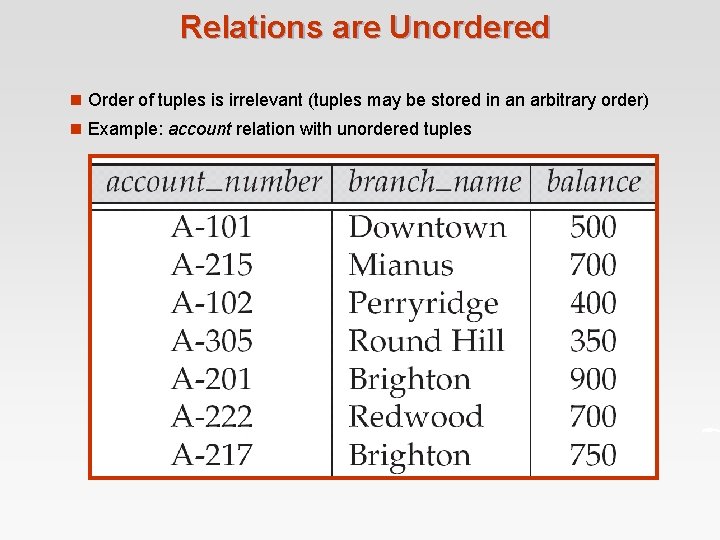

Relations are Unordered n Order of tuples is irrelevant (tuples may be stored in an arbitrary order) n Example: account relation with unordered tuples

Database n A database consists of multiple relations n Information about an enterprise is broken up into parts, with each relation storing one part of the information account : stores information about accounts depositor : stores information about which customer owns which account customer : stores information about customers n Storing all information as a single relation such as bank(account_number, balance, customer_name, . . ) results in l repetition of information (e. g. , two customers own an account) l the need for null values (e. g. , represent a customer without an account) n Normalization theory (Chapter 7) deals with how to design relational schemas

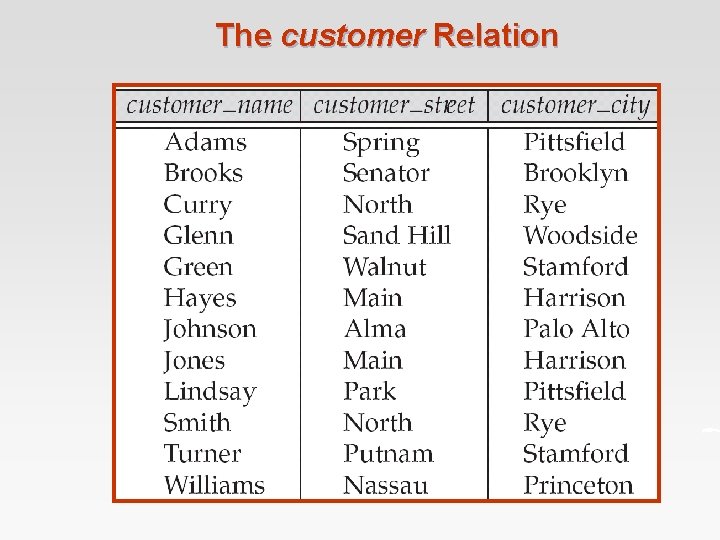

The customer Relation

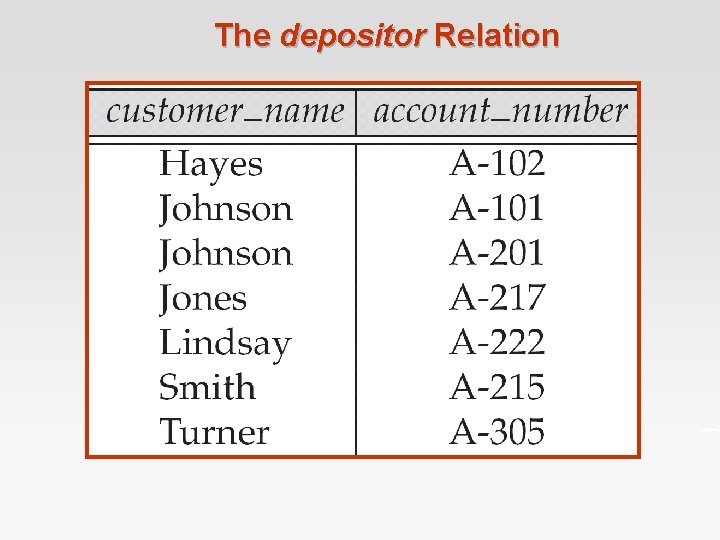

The depositor Relation

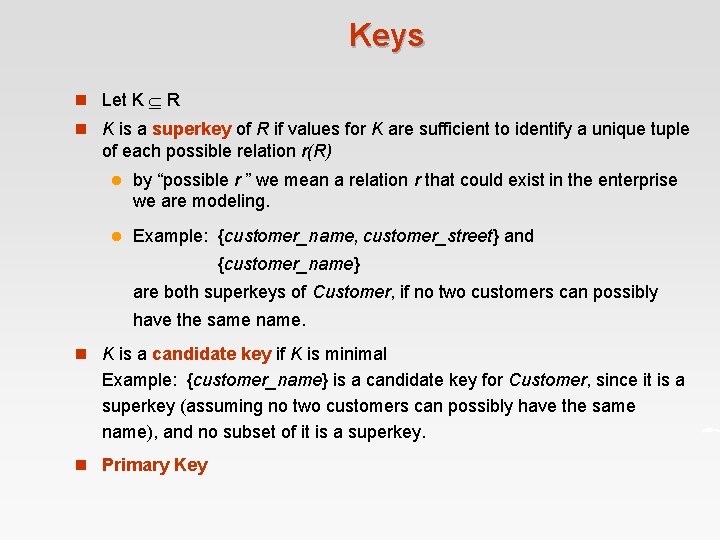

Keys n Let K R n K is a superkey of R if values for K are sufficient to identify a unique tuple of each possible relation r(R) l by “possible r ” we mean a relation r that could exist in the enterprise we are modeling. l Example: {customer_name, customer_street} and {customer_name} are both superkeys of Customer, if no two customers can possibly have the same name. n K is a candidate key if K is minimal Example: {customer_name} is a candidate key for Customer, since it is a superkey (assuming no two customers can possibly have the same name), and no subset of it is a superkey. n Primary Key

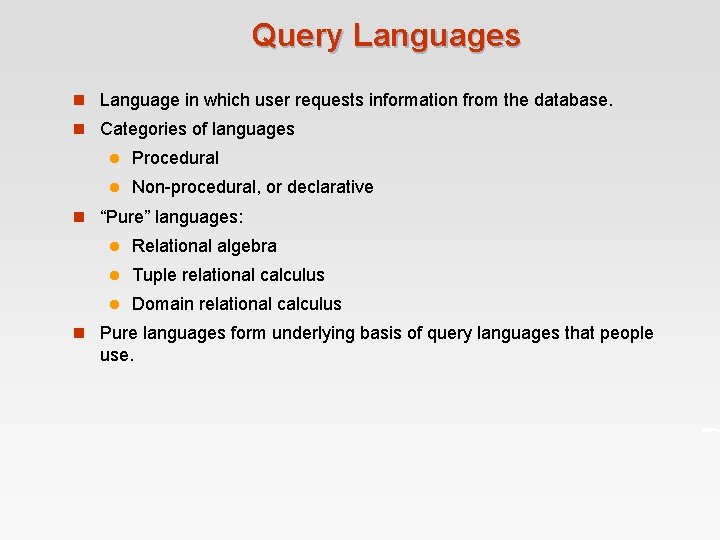

Query Languages n Language in which user requests information from the database. n Categories of languages l Procedural l Non-procedural, or declarative n “Pure” languages: l Relational algebra l Tuple relational calculus l Domain relational calculus n Pure languages form underlying basis of query languages that people use.

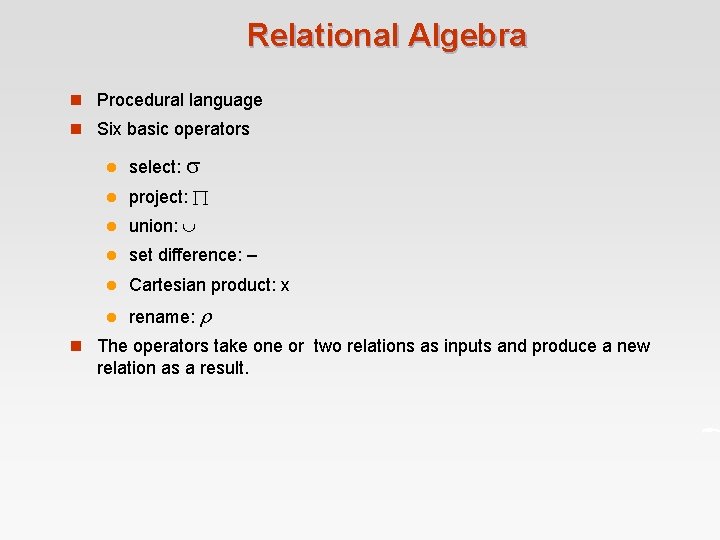

Relational Algebra n Procedural language n Six basic operators l select: l project: l union: l set difference: – l Cartesian product: x l rename: n The operators take one or two relations as inputs and produce a new relation as a result.

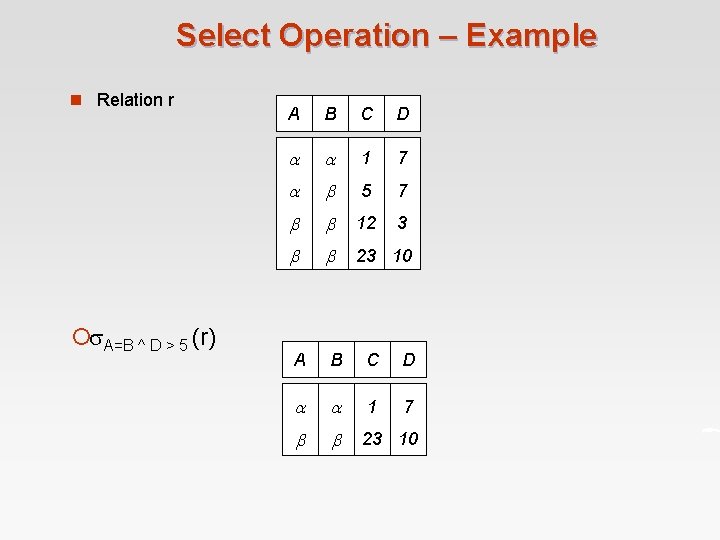

Select Operation – Example n Relation r ¡ A=B ^ D > 5 (r) A B C D 1 7 5 7 12 3 23 10 A B C D 1 7 23 10

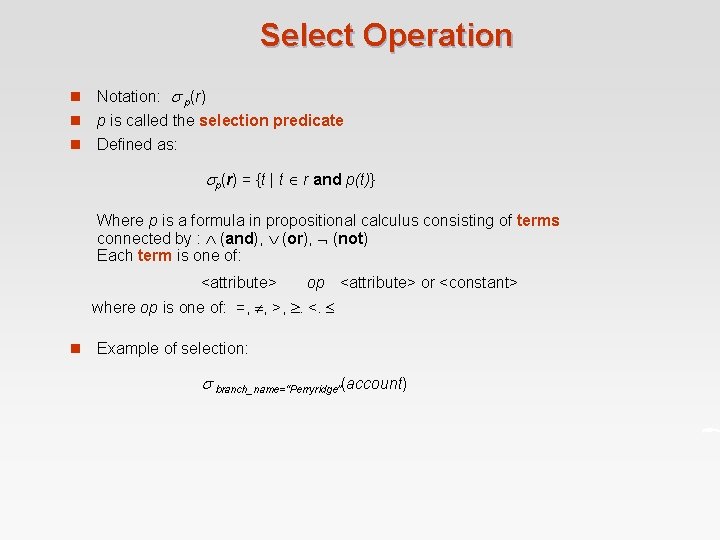

Select Operation n Notation: p(r) n p is called the selection predicate n Defined as: p(r) = {t | t r and p(t)} Where p is a formula in propositional calculus consisting of terms connected by : (and), (or), (not) Each term is one of: <attribute> op <attribute> or <constant> where op is one of: =, , >, . <. n Example of selection: branch_name=“Perryridge”(account)

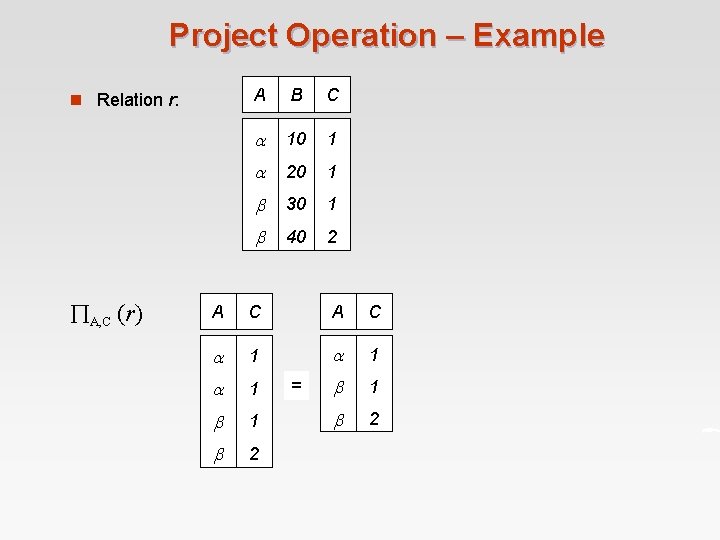

Project Operation – Example n Relation r: A, C (r) A B C 10 1 20 1 30 1 40 2 A C 1 1 1 2 2 =

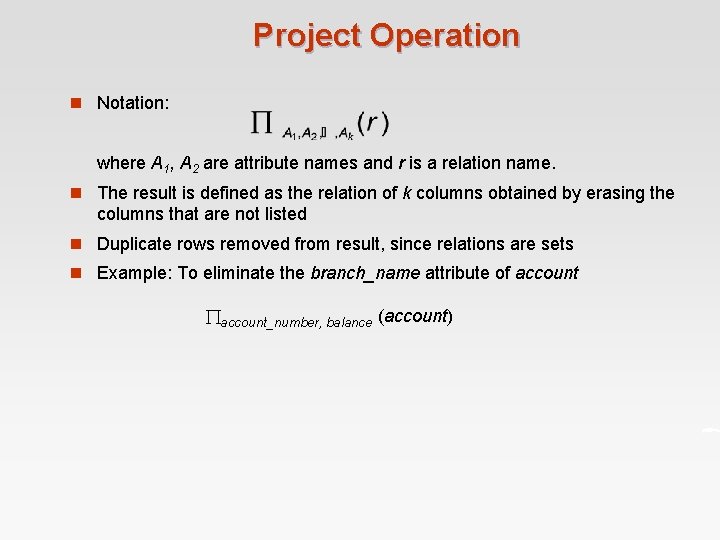

Project Operation n Notation: where A 1, A 2 are attribute names and r is a relation name. n The result is defined as the relation of k columns obtained by erasing the columns that are not listed n Duplicate rows removed from result, since relations are sets n Example: To eliminate the branch_name attribute of account_number, balance (account)

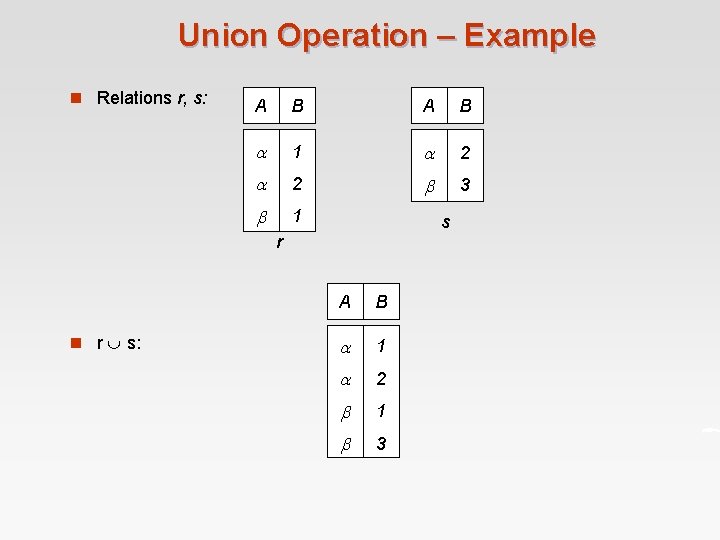

Union Operation – Example n Relations r, s: A B 1 2 2 3 1 s r n r s: A B 1 2 1 3

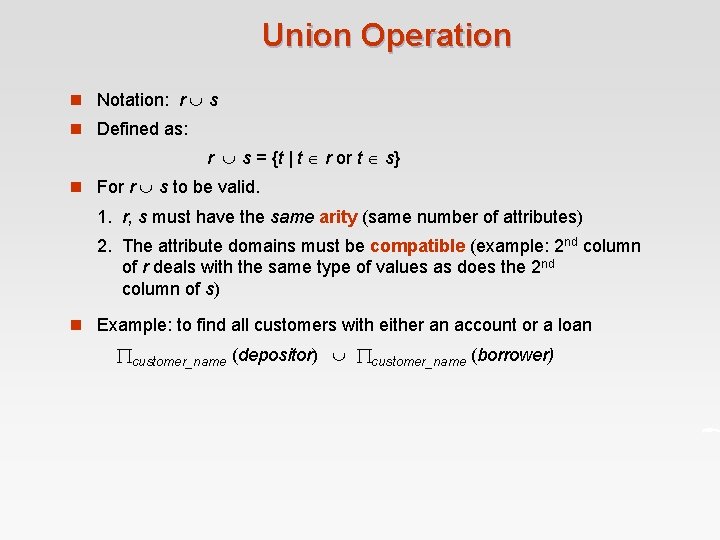

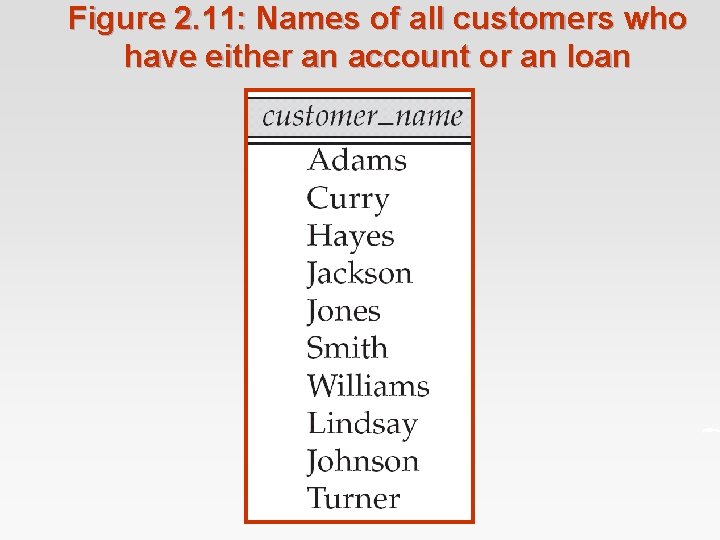

Union Operation n Notation: r s n Defined as: r s = {t | t r or t s} n For r s to be valid. 1. r, s must have the same arity (same number of attributes) 2. The attribute domains must be compatible (example: 2 nd column of r deals with the same type of values as does the 2 nd column of s) n Example: to find all customers with either an account or a loan customer_name (depositor) customer_name (borrower)

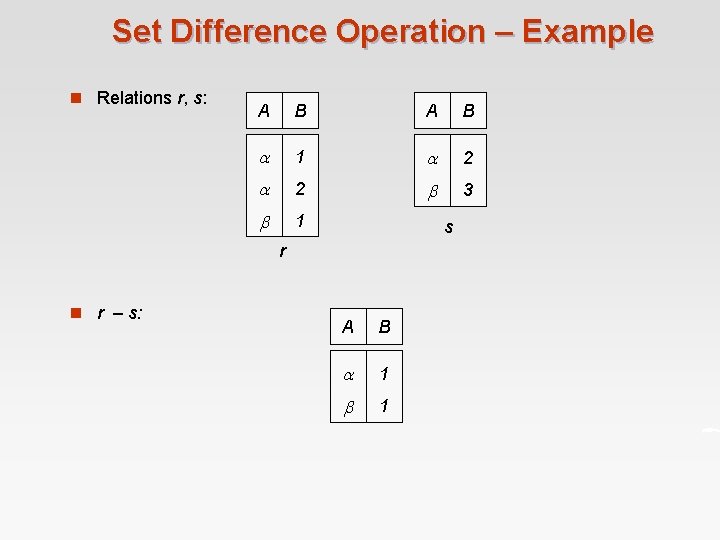

Set Difference Operation – Example n Relations r, s: A B 1 2 2 3 1 s r n r – s: A B 1 1

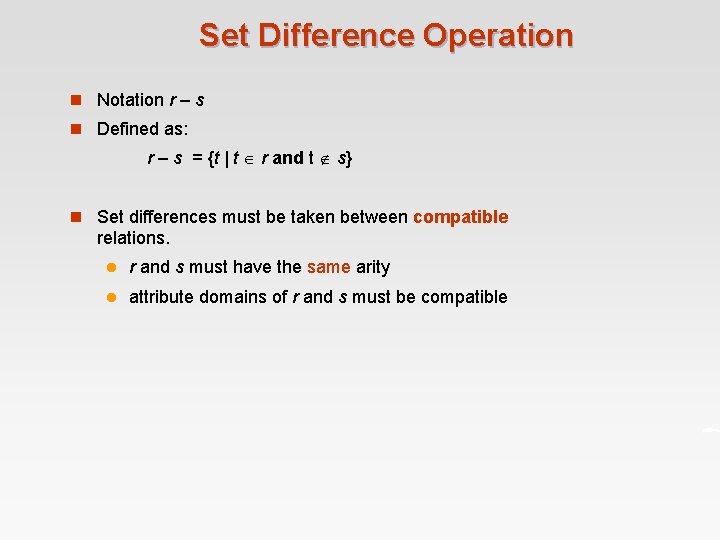

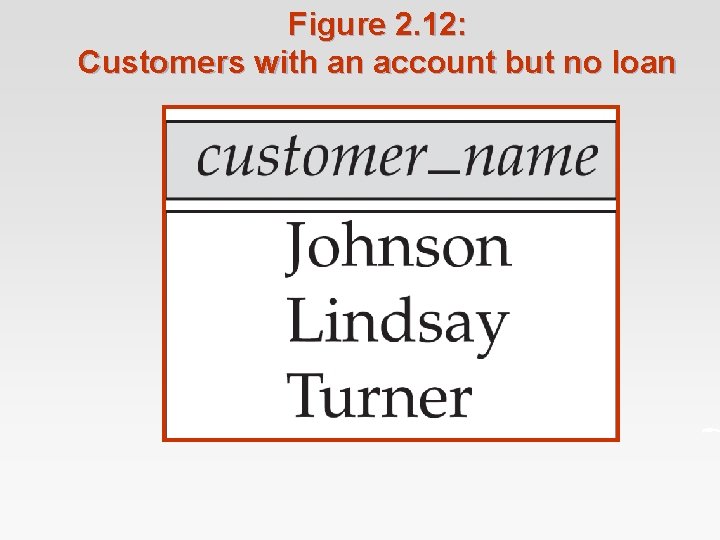

Set Difference Operation n Notation r – s n Defined as: r – s = {t | t r and t s} n Set differences must be taken between compatible relations. l r and s must have the same arity l attribute domains of r and s must be compatible

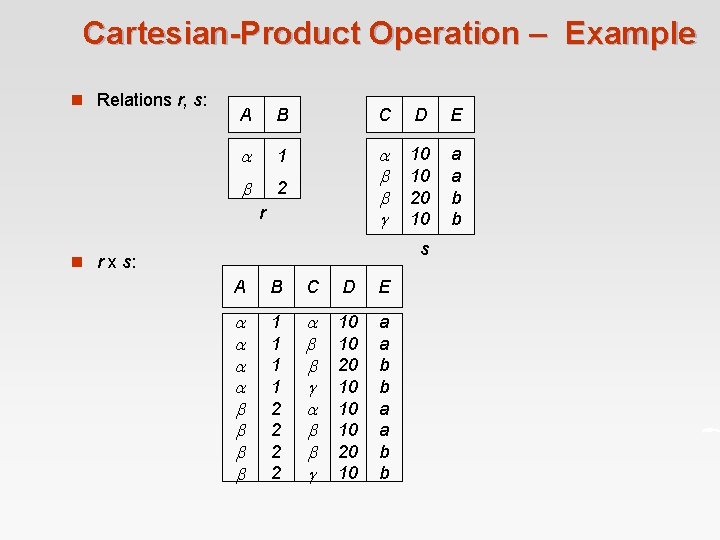

Cartesian-Product Operation – Example n Relations r, s: A B C D E 1 2 10 10 20 10 a a b b r s n r x s: A B C D E 1 1 2 2 10 10 20 10 a a b b

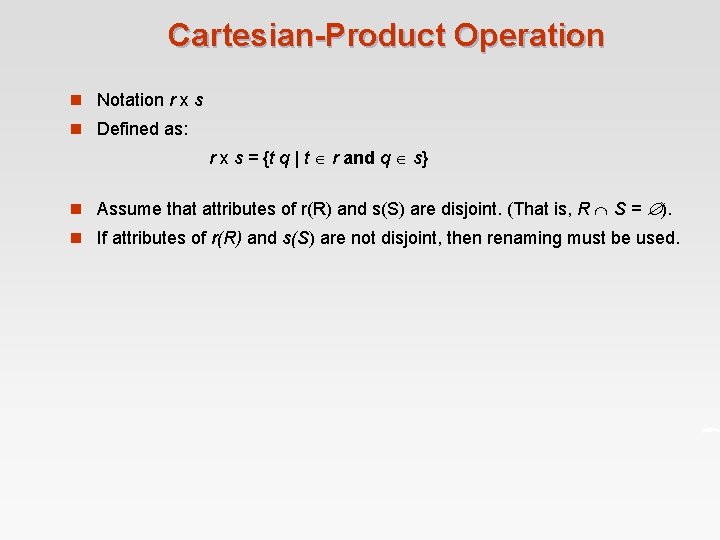

Cartesian-Product Operation n Notation r x s n Defined as: r x s = {t q | t r and q s} n Assume that attributes of r(R) and s(S) are disjoint. (That is, R S = ). n If attributes of r(R) and s(S) are not disjoint, then renaming must be used.

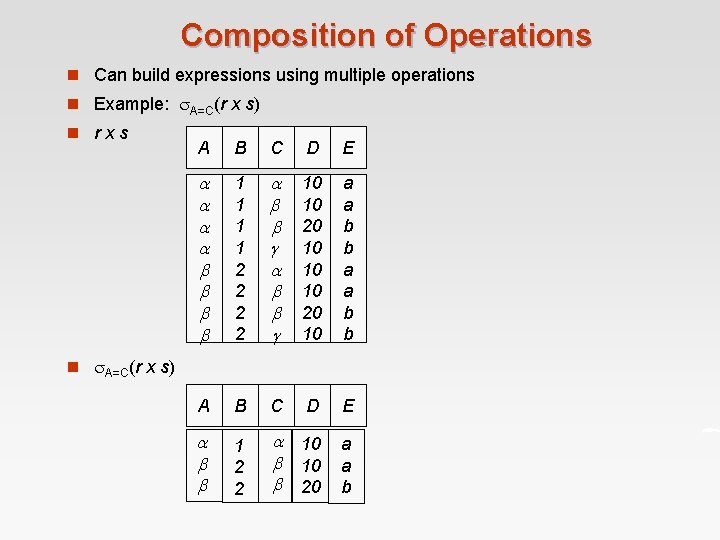

Composition of Operations n Can build expressions using multiple operations n Example: A=C(r x s) n rxs A B C D E 1 1 2 2 10 10 20 10 a a b b A B C D E 1 2 2 10 20 a a b n A=C(r x s)

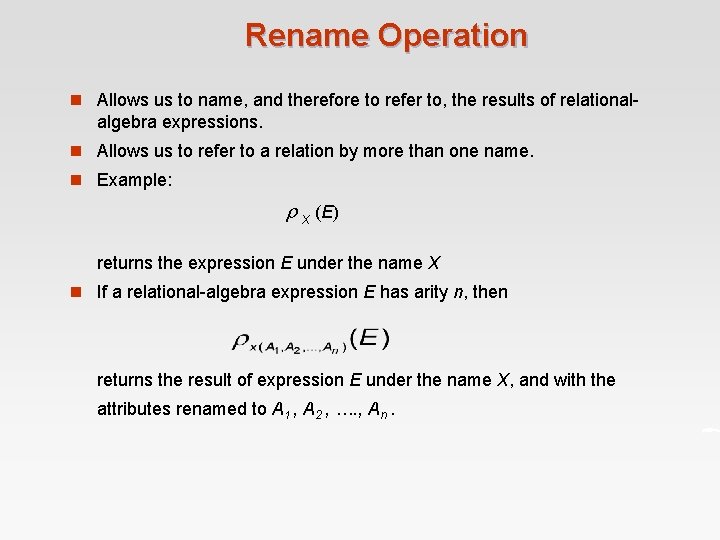

Rename Operation n Allows us to name, and therefore to refer to, the results of relational- algebra expressions. n Allows us to refer to a relation by more than one name. n Example: x (E) returns the expression E under the name X n If a relational-algebra expression E has arity n, then returns the result of expression E under the name X, and with the attributes renamed to A 1 , A 2 , …. , An.

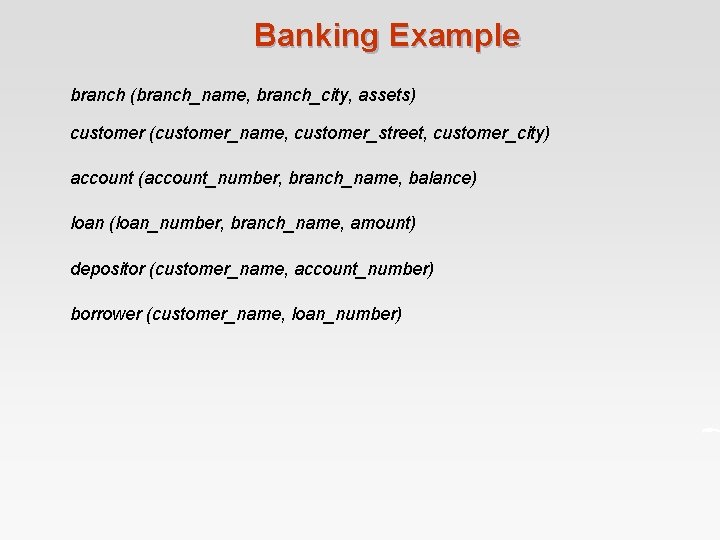

Banking Example branch (branch_name, branch_city, assets) customer (customer_name, customer_street, customer_city) account (account_number, branch_name, balance) loan (loan_number, branch_name, amount) depositor (customer_name, account_number) borrower (customer_name, loan_number)

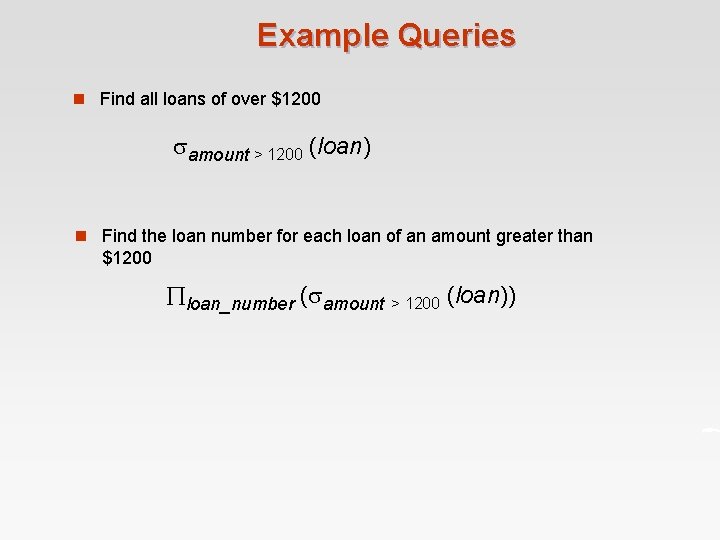

Example Queries n Find all loans of over $1200 amount > 1200 (loan) n Find the loan number for each loan of an amount greater than $1200 loan_number ( amount > 1200 (loan))

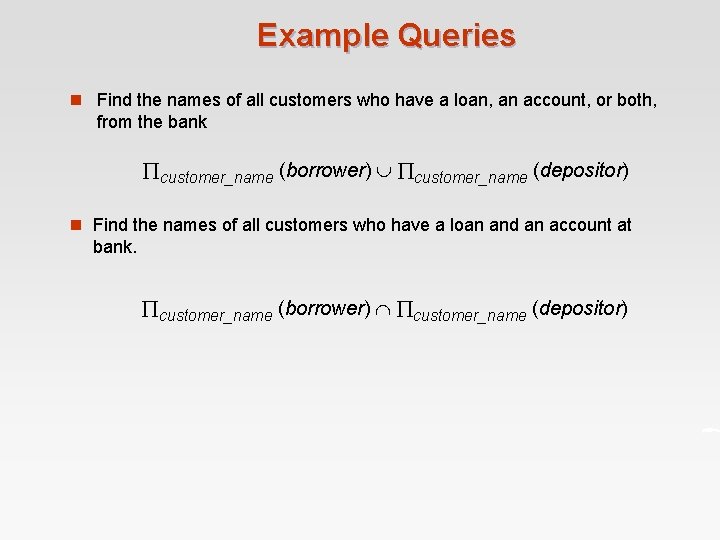

Example Queries n Find the names of all customers who have a loan, an account, or both, from the bank customer_name (borrower) customer_name (depositor) n Find the names of all customers who have a loan and an account at bank. customer_name (borrower) customer_name (depositor)

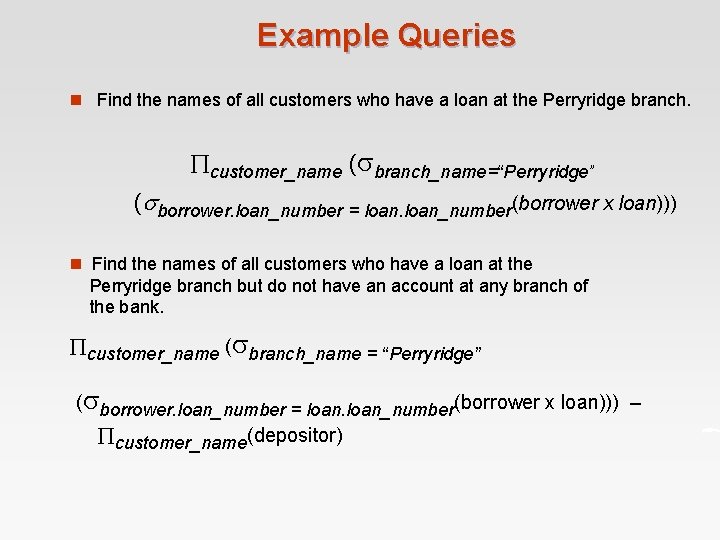

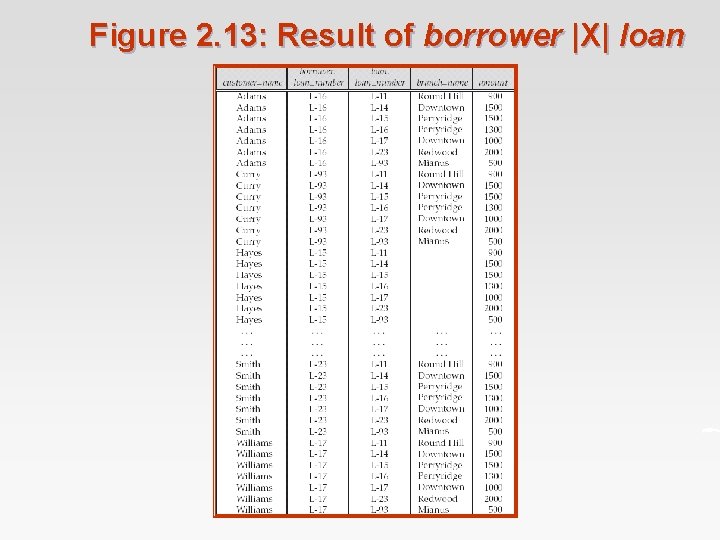

Example Queries n Find the names of all customers who have a loan at the Perryridge branch. customer_name ( branch_name=“Perryridge” ( borrower. loan_number = loan_number(borrower x loan))) n Find the names of all customers who have a loan at the Perryridge branch but do not have an account at any branch of the bank. customer_name ( branch_name = “Perryridge” ( borrower. loan_number = loan_number(borrower x loan))) – customer_name(depositor)

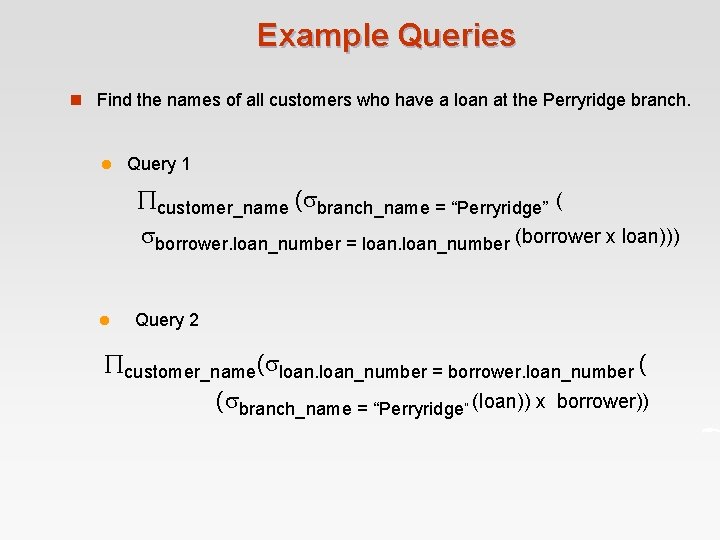

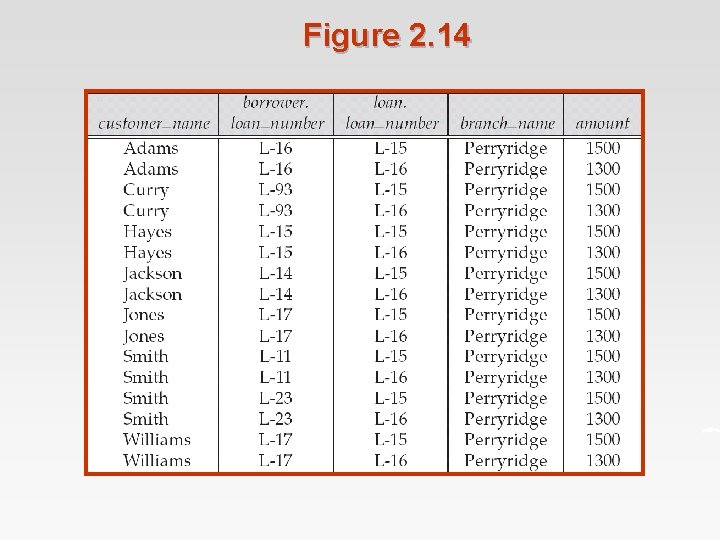

Example Queries n Find the names of all customers who have a loan at the Perryridge branch. l Query 1 customer_name ( branch_name = “Perryridge” ( borrower. loan_number = loan_number (borrower x loan))) l Query 2 customer_name( loan_number = borrower. loan_number ( ( branch_name = “Perryridge” (loan)) x borrower))

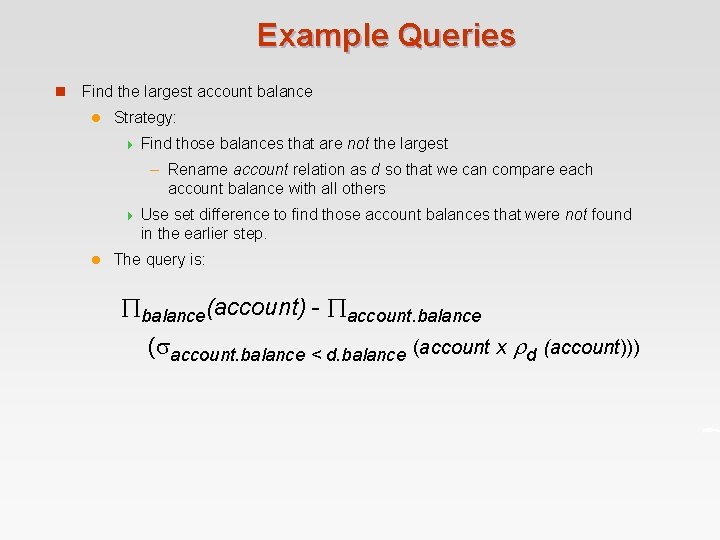

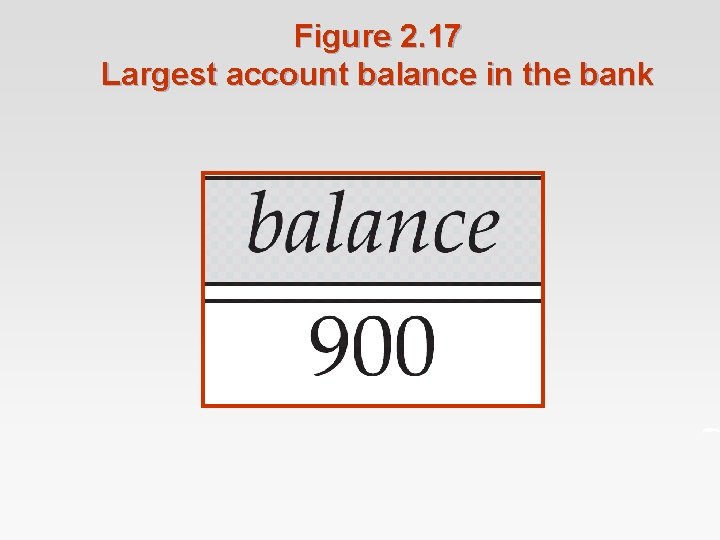

Example Queries n Find the largest account balance l Strategy: 4 Find those balances that are not the largest – Rename account relation as d so that we can compare each account balance with all others 4 l Use set difference to find those account balances that were not found in the earlier step. The query is: balance(account) - account. balance ( account. balance < d. balance (account x d (account)))

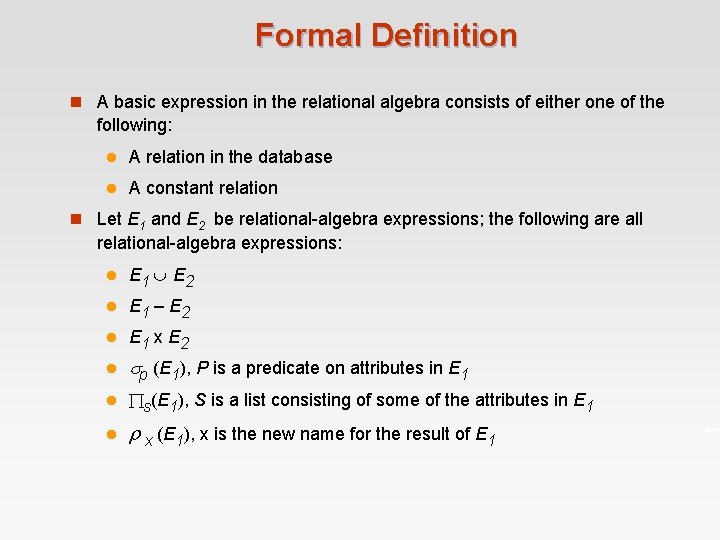

Formal Definition n A basic expression in the relational algebra consists of either one of the following: l A relation in the database l A constant relation n Let E 1 and E 2 be relational-algebra expressions; the following are all relational-algebra expressions: l E 1 E 2 l E 1 – E 2 l E 1 x E 2 l p (E 1), P is a predicate on attributes in E 1 l s(E 1), S is a list consisting of some of the attributes in E 1 l x (E 1), x is the new name for the result of E 1

Additional Operations We define additional operations that do not add any power to the relational algebra, but that simplify common queries. n Set intersection n Natural join n Division n Assignment

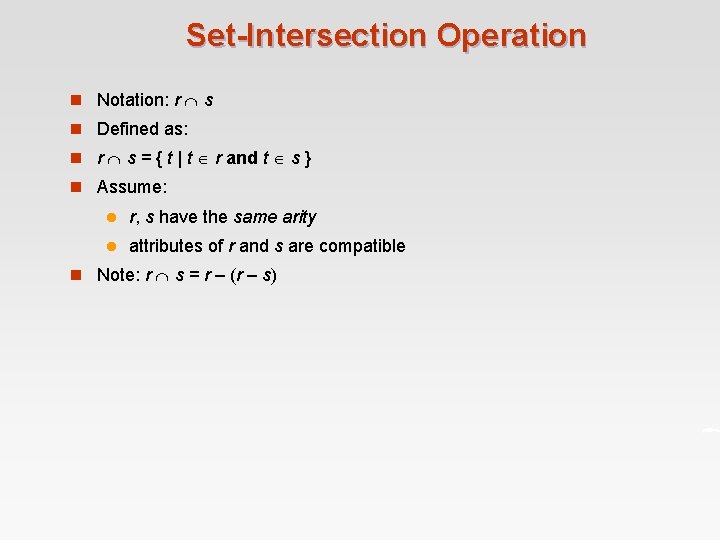

Set-Intersection Operation n Notation: r s n Defined as: n r s = { t | t r and t s } n Assume: l r, s have the same arity l attributes of r and s are compatible n Note: r s = r – (r – s)

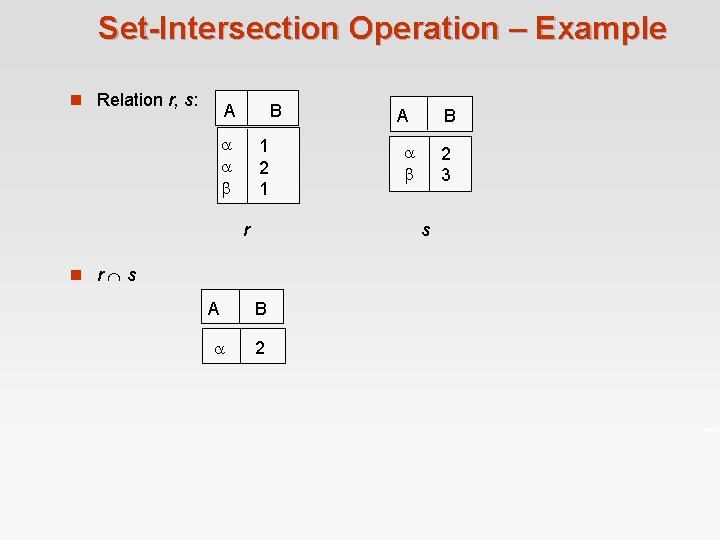

Set-Intersection Operation – Example n Relation r, s: A B 1 2 1 r A B 2 3 s n r s A B 2

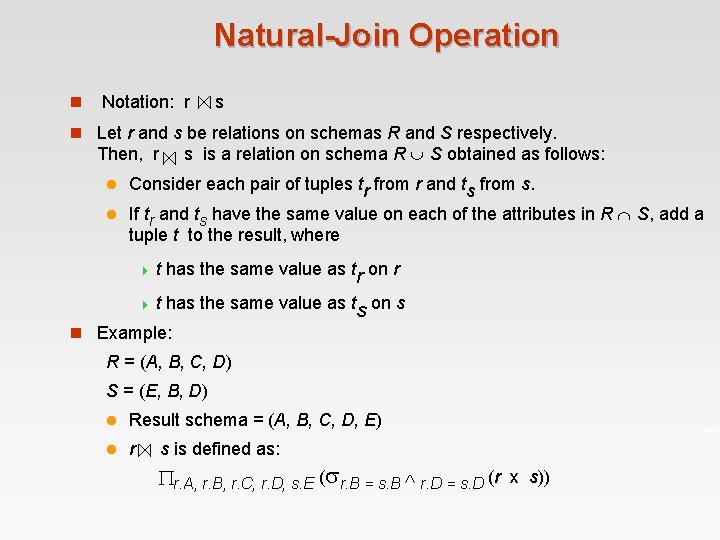

Natural-Join Operation n Notation: r s n Let r and s be relations on schemas R and S respectively. s is a relation on schema R S obtained as follows: Then, r l Consider each pair of tuples tr from r and ts from s. l If tr and ts have the same value on each of the attributes in R S, add a tuple t to the result, where 4 t has the same value as tr on r 4 t has the same value as ts on s n Example: R = (A, B, C, D) S = (E, B, D) l Result schema = (A, B, C, D, E) l r s is defined as: r. A, r. B, r. C, r. D, s. E ( r. B = s. B r. D = s. D (r x s))

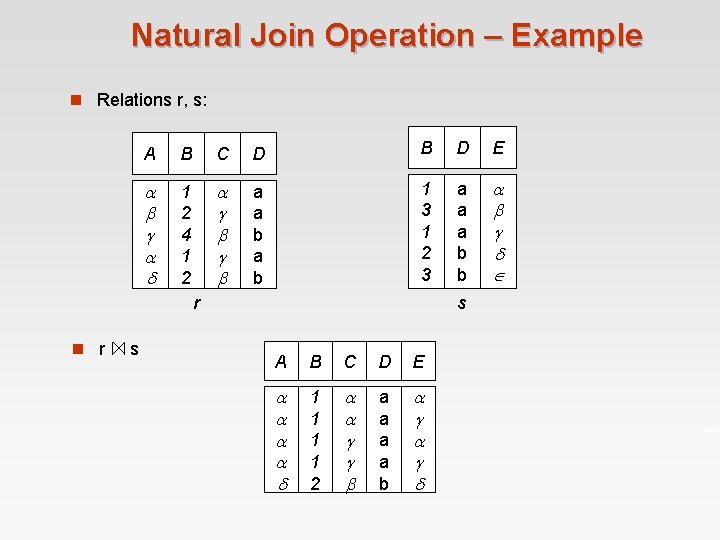

Natural Join Operation – Example n Relations r, s: A B C D B D E 1 2 4 1 2 a a b 1 3 1 2 3 a a a b b r n r s s A B C D E 1 1 2 a a b

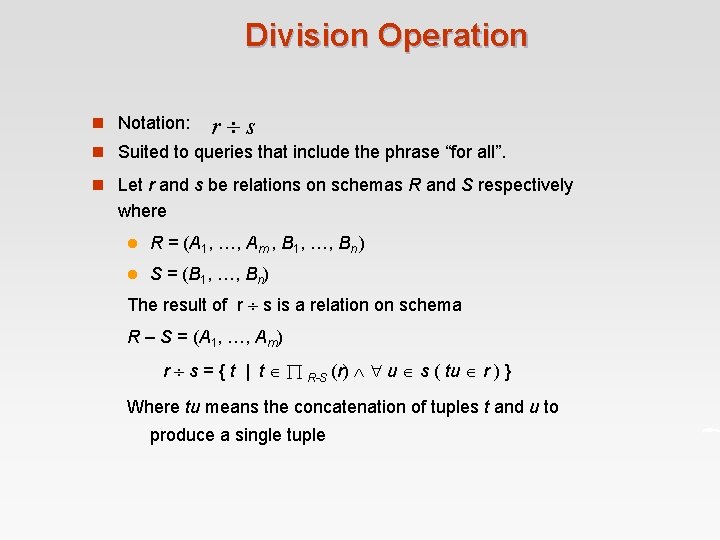

Division Operation n Notation: r s n Suited to queries that include the phrase “for all”. n Let r and s be relations on schemas R and S respectively where l R = (A 1, …, Am , B 1, …, Bn ) l S = (B 1, …, Bn) The result of r s is a relation on schema R – S = (A 1, …, Am) r s = { t | t R-S (r) u s ( tu r ) } Where tu means the concatenation of tuples t and u to produce a single tuple

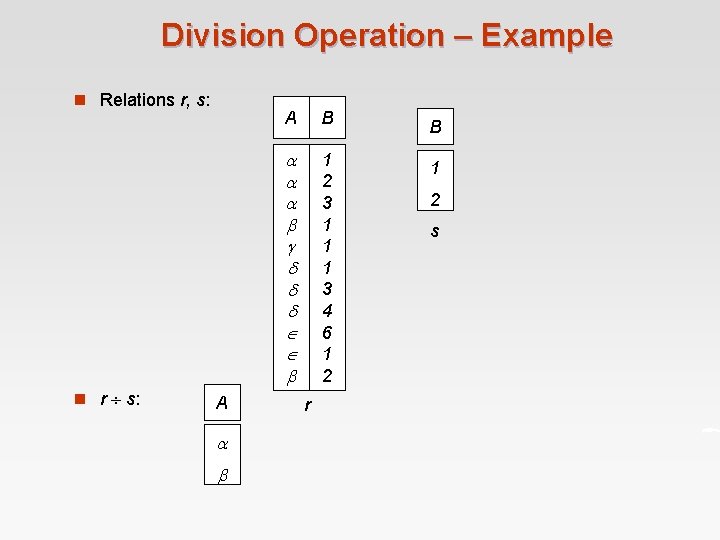

Division Operation – Example n Relations r, s: n r s: A A B B 1 2 3 1 1 1 3 4 6 1 2 1 r 2 s

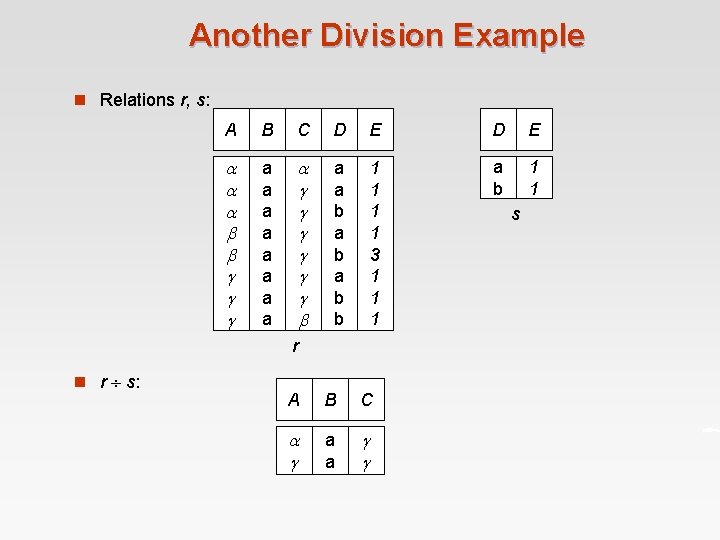

Another Division Example n Relations r, s: A B C D E a a a a a a b a b b 1 1 3 1 1 1 a b 1 1 r n r s: A B C a a s

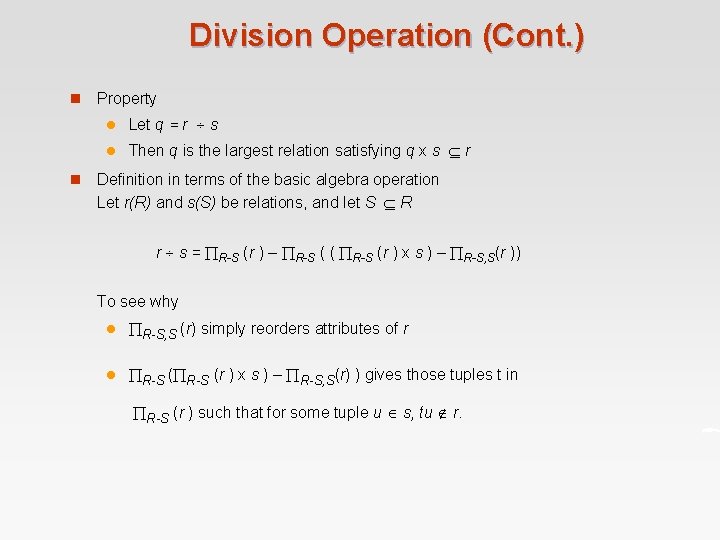

Division Operation (Cont. ) n n Property l Let q = r s l Then q is the largest relation satisfying q x s r Definition in terms of the basic algebra operation Let r(R) and s(S) be relations, and let S R r s = R-S (r ) – R-S ( ( R-S (r ) x s ) – R-S, S(r )) To see why l R-S, S (r) simply reorders attributes of r l R-S (r ) x s ) – R-S, S(r) ) gives those tuples t in R-S (r ) such that for some tuple u s, tu r.

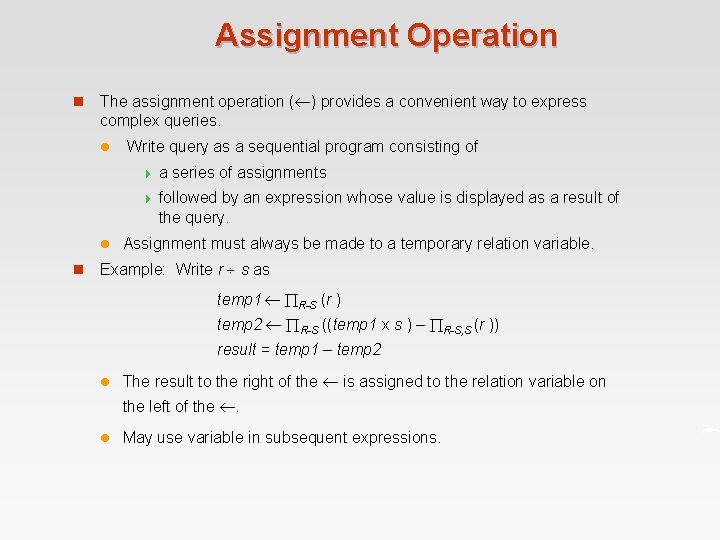

Assignment Operation n The assignment operation ( ) provides a convenient way to express complex queries. l l n Write query as a sequential program consisting of 4 a series of assignments 4 followed by an expression whose value is displayed as a result of the query. Assignment must always be made to a temporary relation variable. Example: Write r s as temp 1 R-S (r ) temp 2 R-S ((temp 1 x s ) – R-S, S (r )) result = temp 1 – temp 2 l The result to the right of the is assigned to the relation variable on the left of the . l May use variable in subsequent expressions.

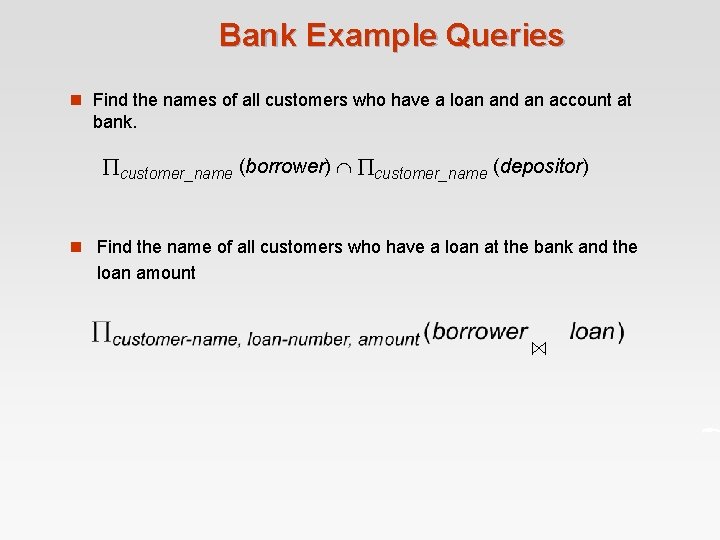

Bank Example Queries n Find the names of all customers who have a loan and an account at bank. customer_name (borrower) customer_name (depositor) n Find the name of all customers who have a loan at the bank and the loan amount

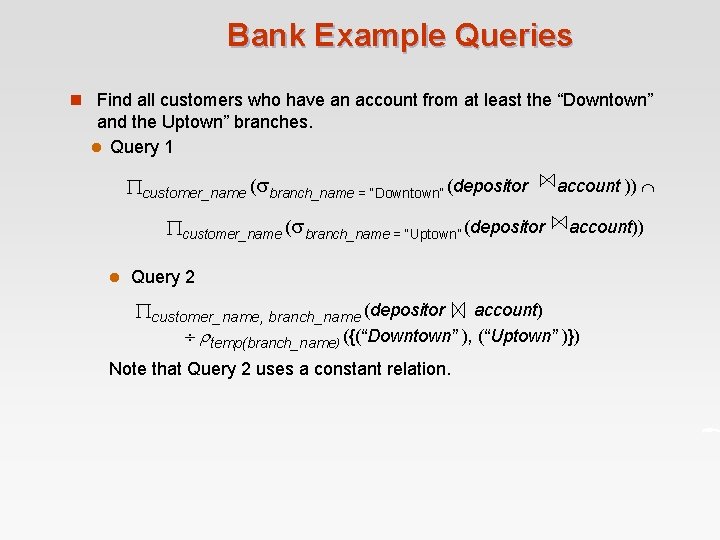

Bank Example Queries n Find all customers who have an account from at least the “Downtown” and the Uptown” branches. l Query 1 customer_name ( branch_name = “Downtown” (depositor customer_name ( branch_name = “Uptown” (depositor l account )) account)) Query 2 customer_name, branch_name (depositor account) temp(branch_name) ({(“Downtown” ), (“Uptown” )}) Note that Query 2 uses a constant relation.

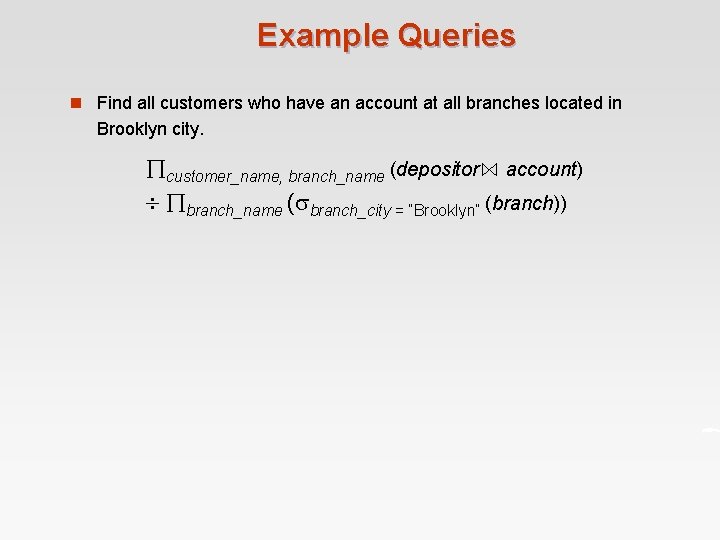

Example Queries n Find all customers who have an account at all branches located in Brooklyn city. customer_name, branch_name (depositor account) branch_name ( branch_city = “Brooklyn” (branch))

Extended Relational-Algebra-Operations n Generalized Projection n Aggregate Functions n Outer Join

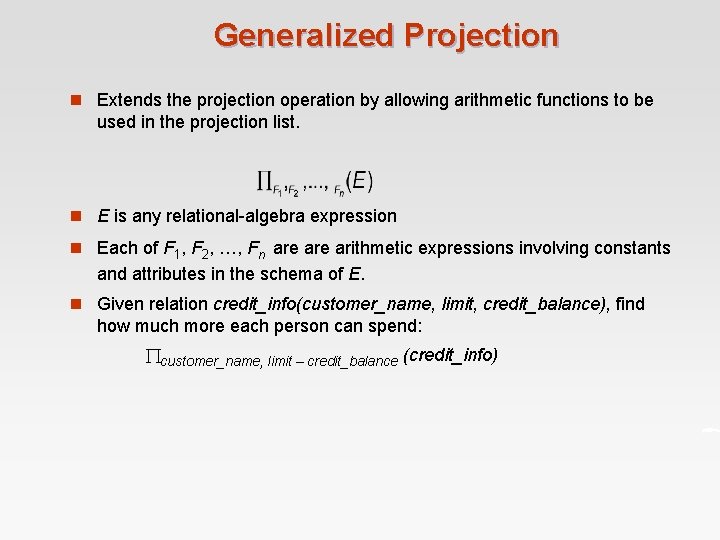

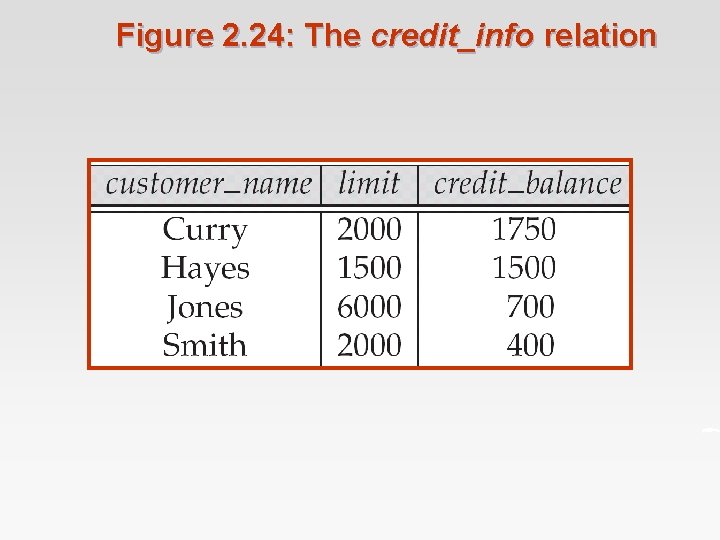

Generalized Projection n Extends the projection operation by allowing arithmetic functions to be used in the projection list. n E is any relational-algebra expression n Each of F 1, F 2, …, Fn are arithmetic expressions involving constants and attributes in the schema of E. n Given relation credit_info(customer_name, limit, credit_balance), find how much more each person can spend: customer_name, limit – credit_balance (credit_info)

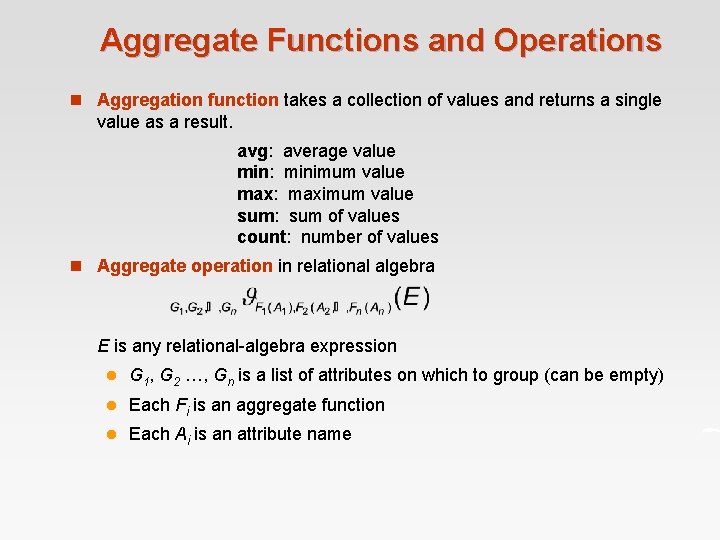

Aggregate Functions and Operations n Aggregation function takes a collection of values and returns a single value as a result. avg: average value min: minimum value max: maximum value sum: sum of values count: number of values n Aggregate operation in relational algebra E is any relational-algebra expression l G 1, G 2 …, Gn is a list of attributes on which to group (can be empty) l Each Fi is an aggregate function l Each Ai is an attribute name

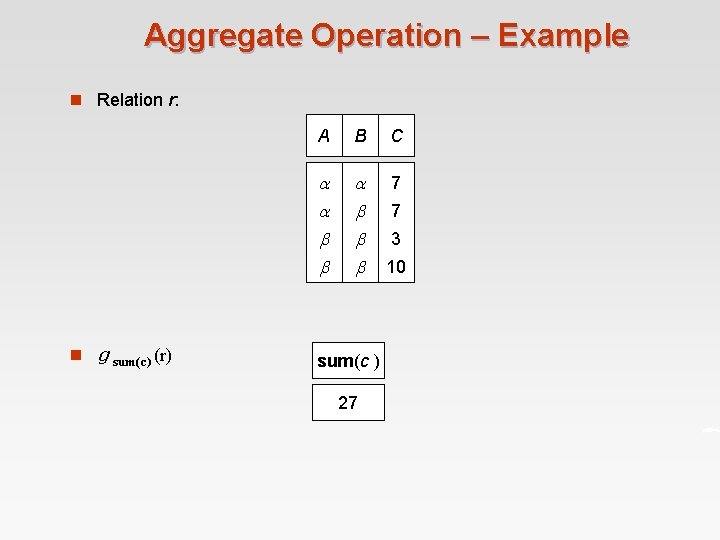

Aggregate Operation – Example n Relation r: n g sum(c) (r) A B C 7 sum(c ) 27 7 3 10

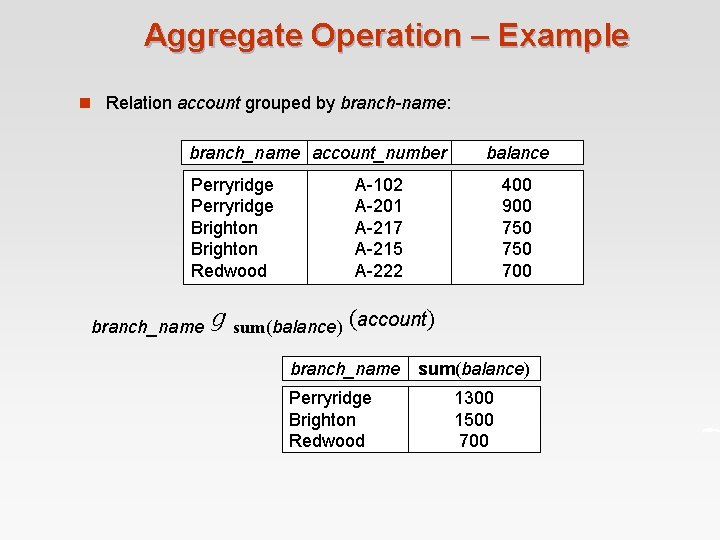

Aggregate Operation – Example n Relation account grouped by branch-name: branch_name account_number Perryridge Brighton Redwood branch_name balance A-102 A-201 A-217 A-215 A-222 400 900 750 700 g sum(balance) (account) branch_name sum(balance) Perryridge Brighton Redwood 1300 1500 700

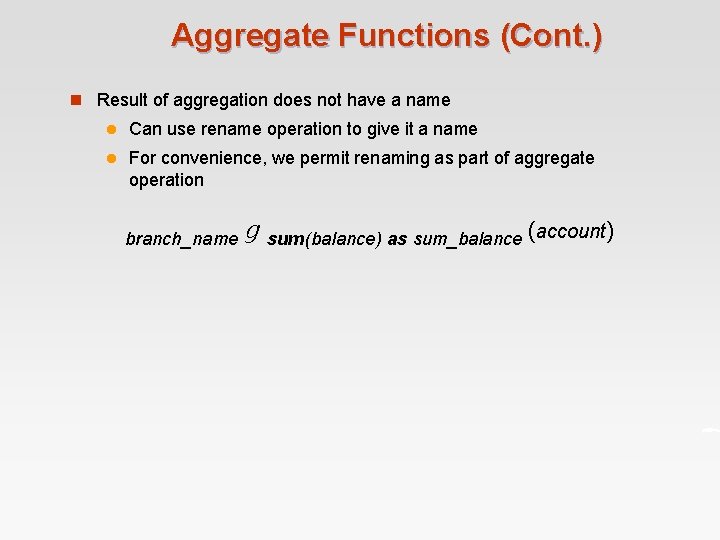

Aggregate Functions (Cont. ) n Result of aggregation does not have a name l Can use rename operation to give it a name l For convenience, we permit renaming as part of aggregate operation branch_name g sum(balance) as sum_balance (account)

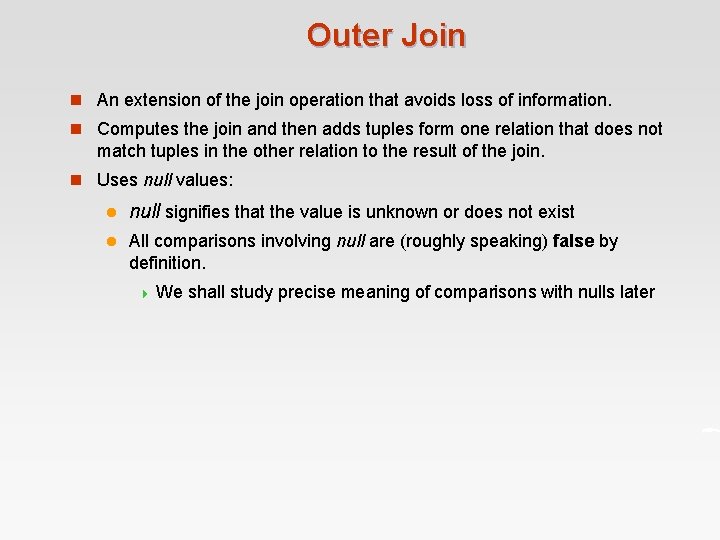

Outer Join n An extension of the join operation that avoids loss of information. n Computes the join and then adds tuples form one relation that does not match tuples in the other relation to the result of the join. n Uses null values: l null signifies that the value is unknown or does not exist l All comparisons involving null are (roughly speaking) false by definition. 4 We shall study precise meaning of comparisons with nulls later

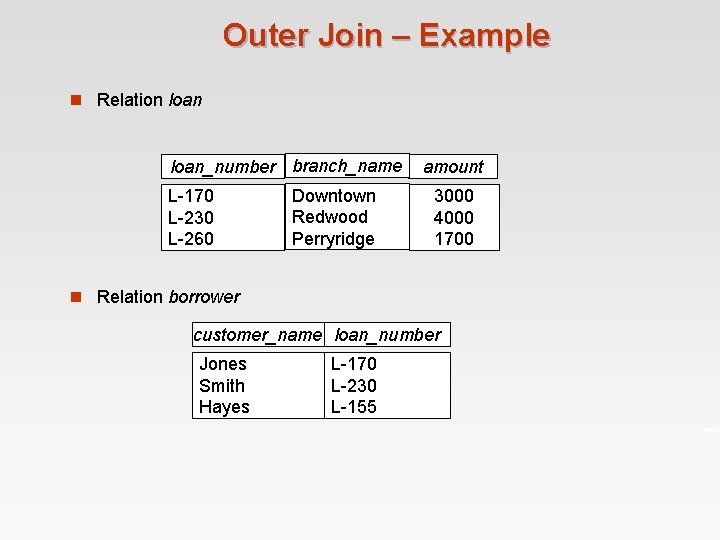

Outer Join – Example n Relation loan_number branch_name L-170 L-230 L-260 Downtown Redwood Perryridge amount 3000 4000 1700 n Relation borrower customer_name loan_number Jones Smith Hayes L-170 L-230 L-155

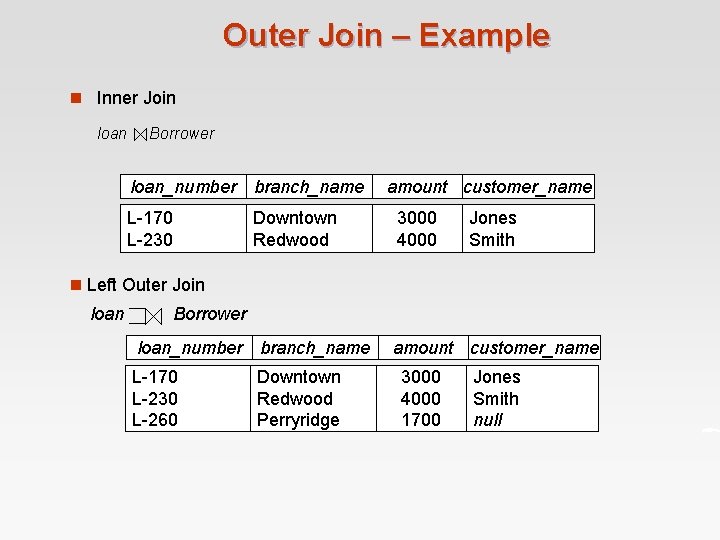

Outer Join – Example n Inner Join loan Borrower loan_number branch_name L-170 L-230 Downtown Redwood amount customer_name 3000 4000 Jones Smith n Left Outer Join loan Borrower loan_number branch_name L-170 L-230 L-260 Downtown Redwood Perryridge amount customer_name 3000 4000 1700 Jones Smith null

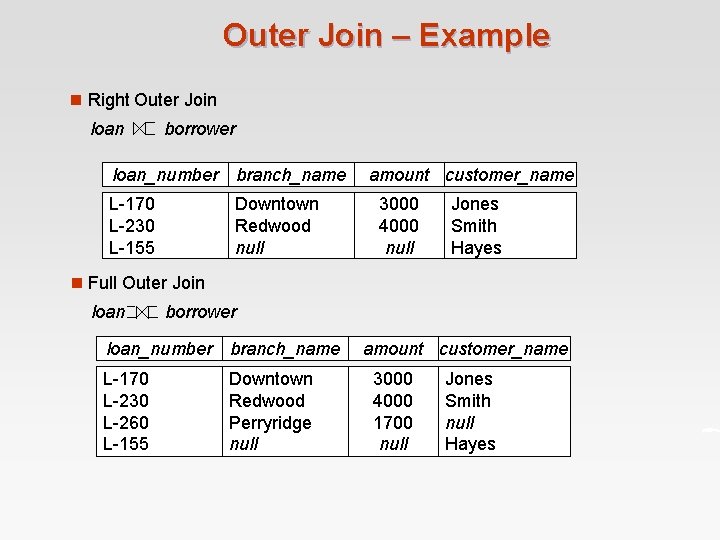

Outer Join – Example n Right Outer Join loan borrower loan_number branch_name L-170 L-230 L-155 Downtown Redwood null amount customer_name 3000 4000 null Jones Smith Hayes n Full Outer Join loan borrower loan_number branch_name L-170 L-230 L-260 L-155 Downtown Redwood Perryridge null amount customer_name 3000 4000 1700 null Jones Smith null Hayes

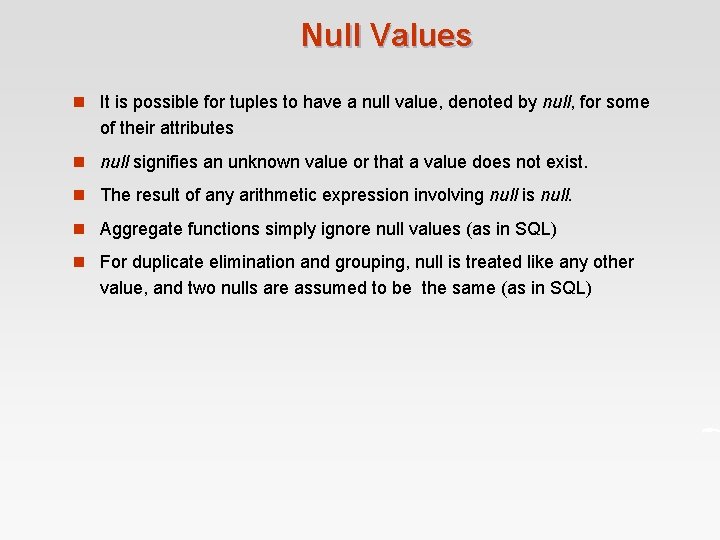

Null Values n It is possible for tuples to have a null value, denoted by null, for some of their attributes n null signifies an unknown value or that a value does not exist. n The result of any arithmetic expression involving null is null. n Aggregate functions simply ignore null values (as in SQL) n For duplicate elimination and grouping, null is treated like any other value, and two nulls are assumed to be the same (as in SQL)

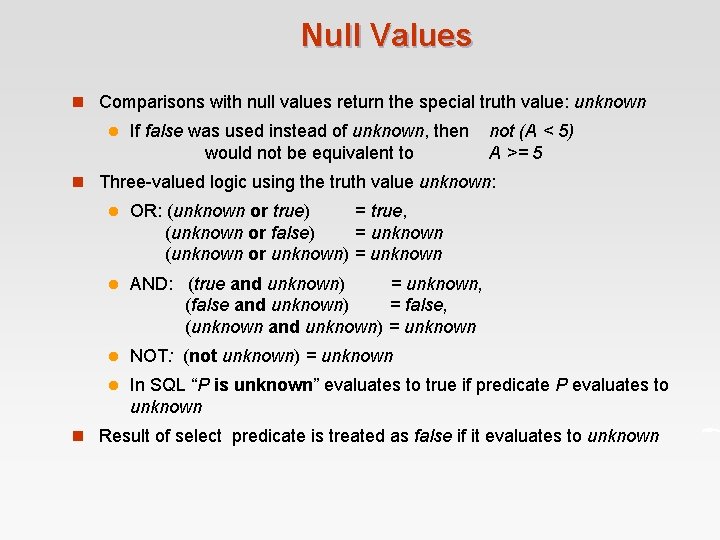

Null Values n Comparisons with null values return the special truth value: unknown l If false was used instead of unknown, then would not be equivalent to not (A < 5) A >= 5 n Three-valued logic using the truth value unknown: l OR: (unknown or true) = true, (unknown or false) = unknown (unknown or unknown) = unknown l AND: (true and unknown) = unknown, (false and unknown) = false, (unknown and unknown) = unknown l NOT: (not unknown) = unknown l In SQL “P is unknown” evaluates to true if predicate P evaluates to unknown n Result of select predicate is treated as false if it evaluates to unknown

Modification of the Database n The content of the database may be modified using the following operations: l Deletion l Insertion l Updating n All these operations are expressed using the assignment operator.

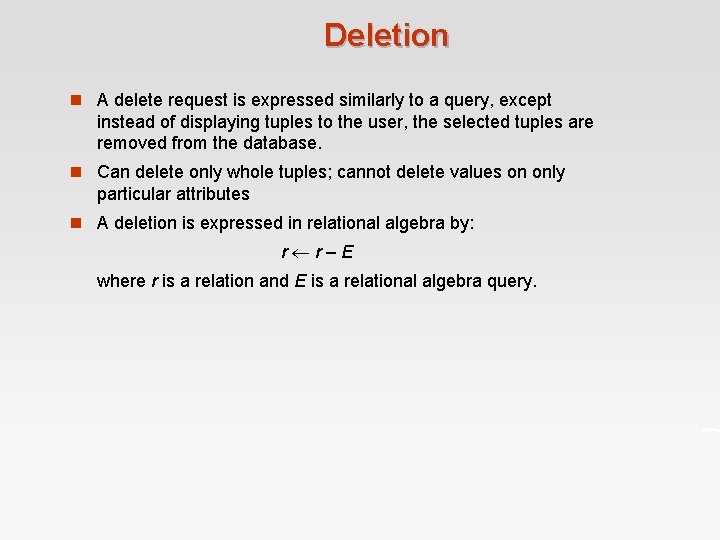

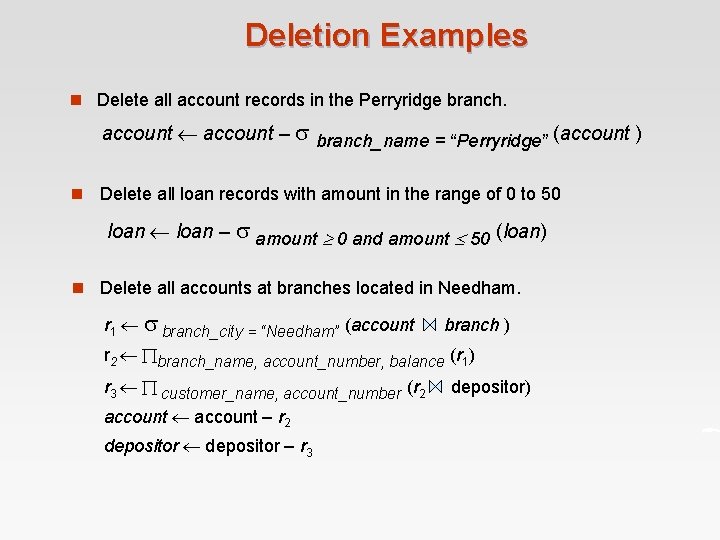

Deletion n A delete request is expressed similarly to a query, except instead of displaying tuples to the user, the selected tuples are removed from the database. n Can delete only whole tuples; cannot delete values on only particular attributes n A deletion is expressed in relational algebra by: r r–E where r is a relation and E is a relational algebra query.

Deletion Examples n Delete all account records in the Perryridge branch. account – branch_name = “Perryridge” (account ) n Delete all loan records with amount in the range of 0 to 50 loan – amount 0 and amount 50 (loan) n Delete all accounts at branches located in Needham. r 1 branch_city = “Needham” (account branch ) r 2 branch_name, account_number, balance (r 1) r 3 customer_name, account_number (r 2 account – r 2 depositor – r 3 depositor)

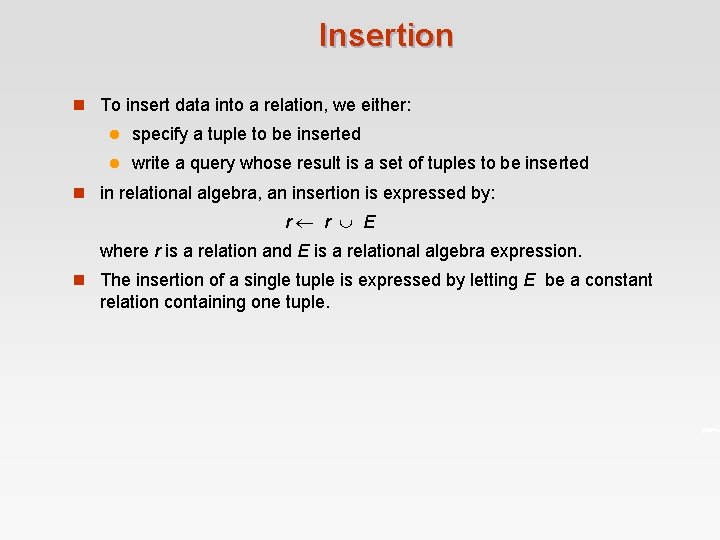

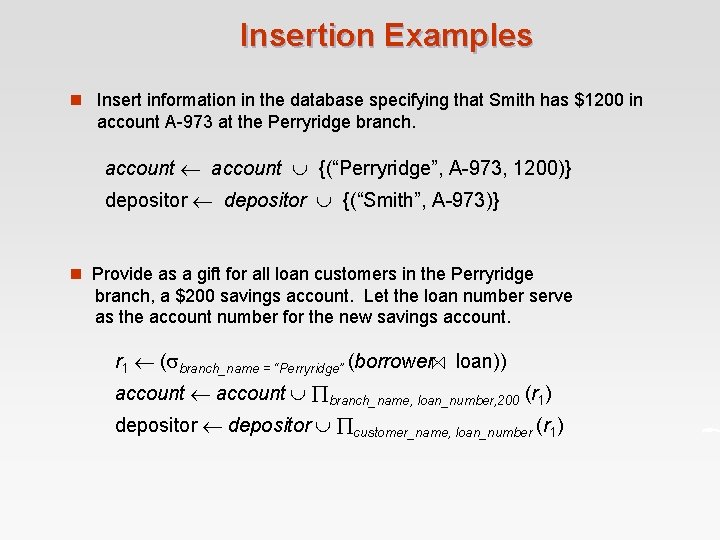

Insertion n To insert data into a relation, we either: l specify a tuple to be inserted l write a query whose result is a set of tuples to be inserted n in relational algebra, an insertion is expressed by: r r E where r is a relation and E is a relational algebra expression. n The insertion of a single tuple is expressed by letting E be a constant relation containing one tuple.

Insertion Examples n Insert information in the database specifying that Smith has $1200 in account A-973 at the Perryridge branch. account {(“Perryridge”, A-973, 1200)} depositor {(“Smith”, A-973)} n Provide as a gift for all loan customers in the Perryridge branch, a $200 savings account. Let the loan number serve as the account number for the new savings account. r 1 ( branch_name = “Perryridge” (borrower loan)) account branch_name, loan_number, 200 (r 1) depositor customer_name, loan_number (r 1)

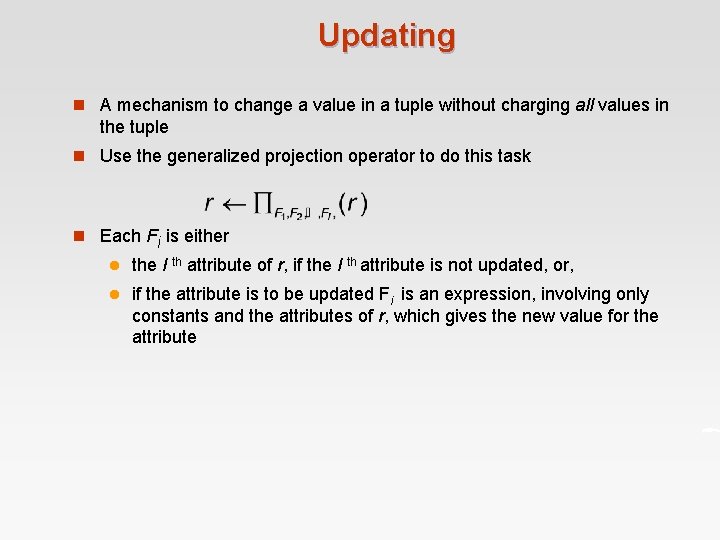

Updating n A mechanism to change a value in a tuple without charging all values in the tuple n Use the generalized projection operator to do this task n Each Fi is either l the I th attribute of r, if the I th attribute is not updated, or, l if the attribute is to be updated Fi is an expression, involving only constants and the attributes of r, which gives the new value for the attribute

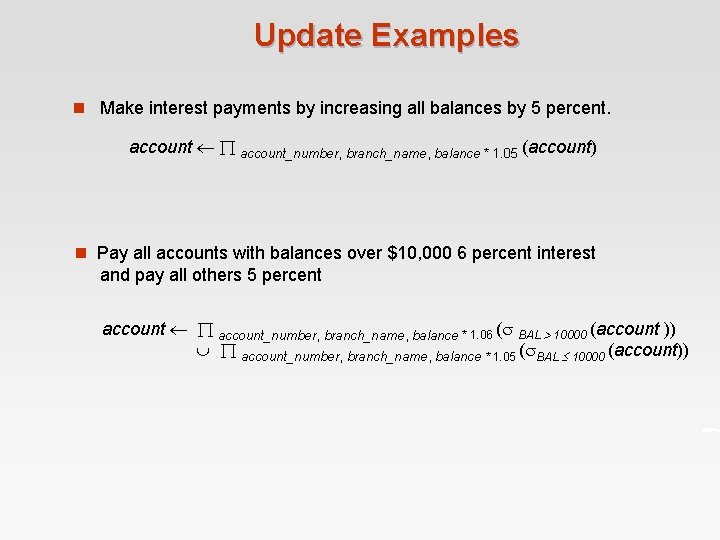

Update Examples n Make interest payments by increasing all balances by 5 percent. account_number, branch_name, balance * 1. 05 (account) n Pay all accounts with balances over $10, 000 6 percent interest and pay all others 5 percent account_number, branch_name, balance * 1. 06 ( BAL 10000 (account )) account_number, branch_name, balance * 1. 05 ( BAL 10000 (account))

End of Chapter 2 Database System Concepts, 5 th Ed. ©Silberschatz, Korth and Sudarshan See www. db-book. com for conditions on re-use

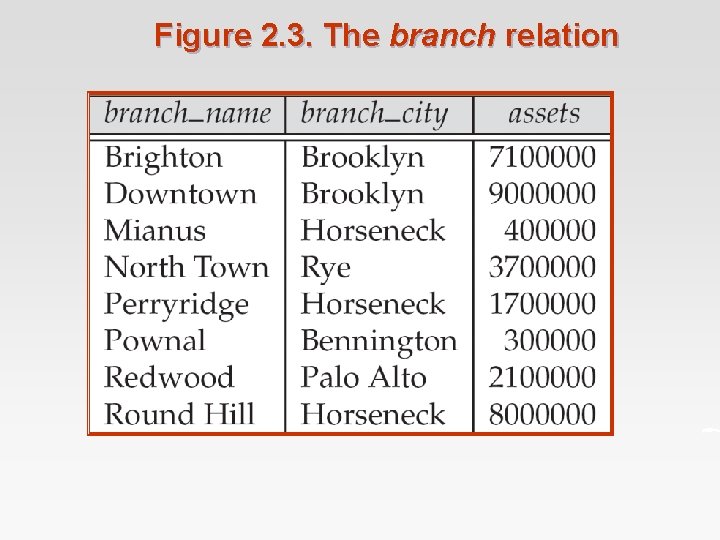

Figure 2. 3. The branch relation

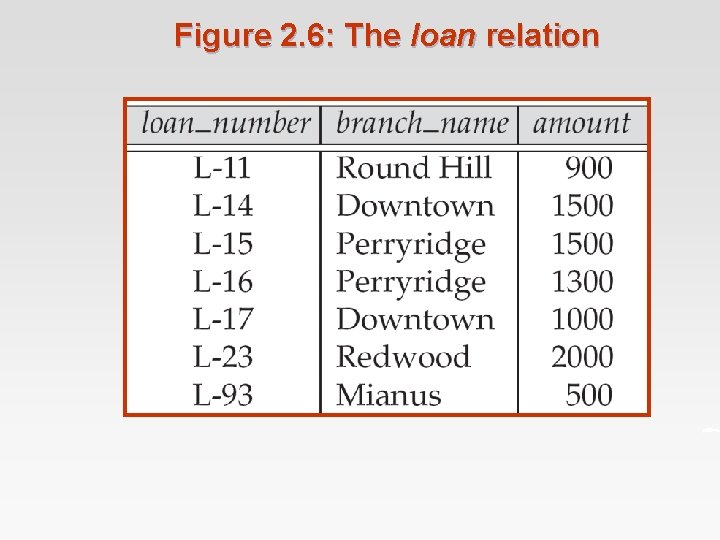

Figure 2. 6: The loan relation

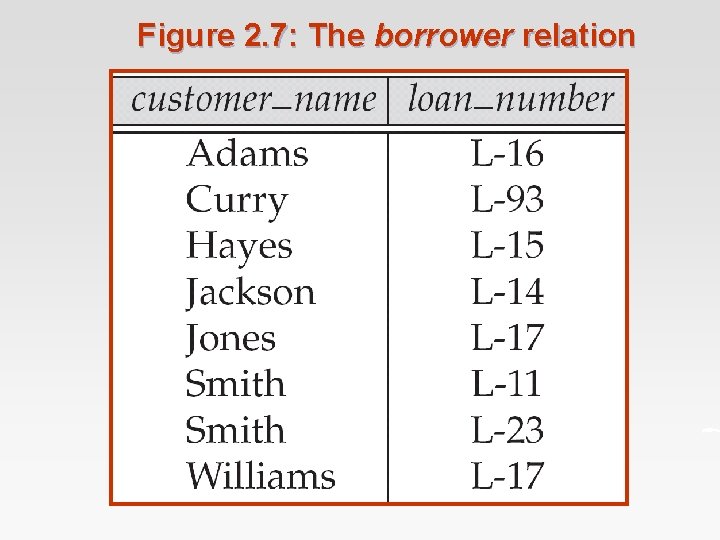

Figure 2. 7: The borrower relation

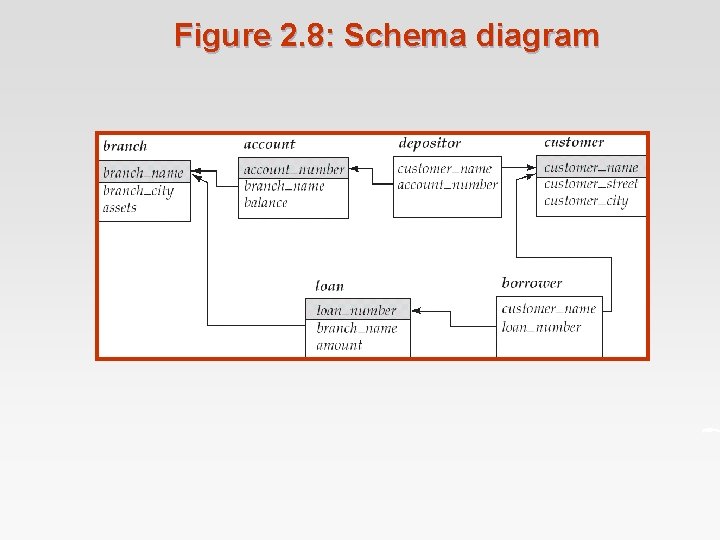

Figure 2. 8: Schema diagram

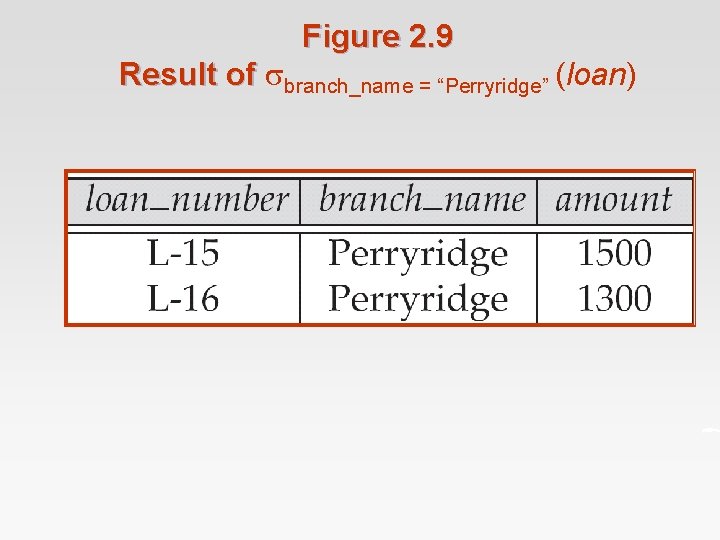

Figure 2. 9 Result of branch_name = “Perryridge” (loan)

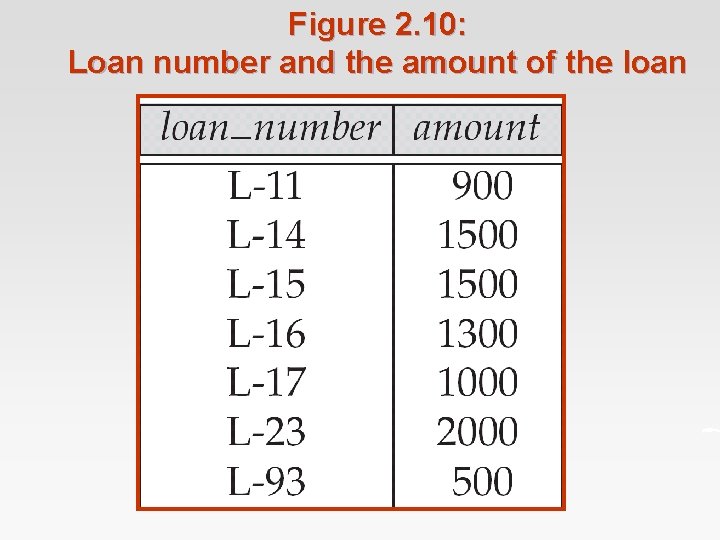

Figure 2. 10: Loan number and the amount of the loan

Figure 2. 11: Names of all customers who have either an account or an loan

Figure 2. 12: Customers with an account but no loan

Figure 2. 13: Result of borrower |X| loan

Figure 2. 14

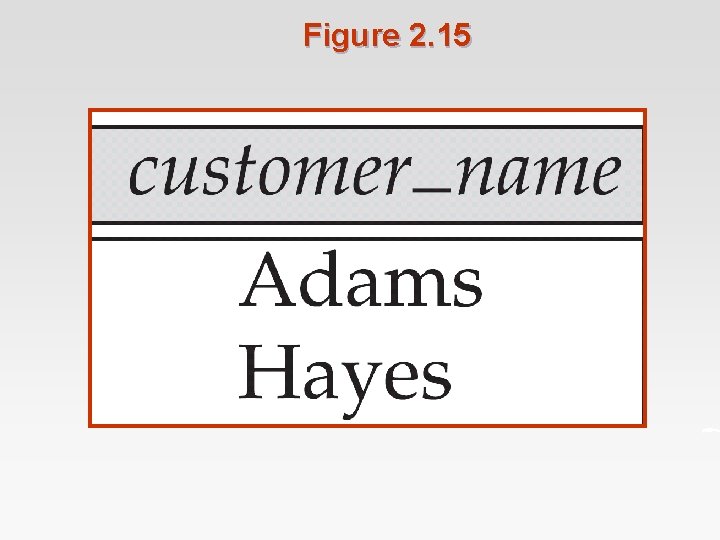

Figure 2. 15

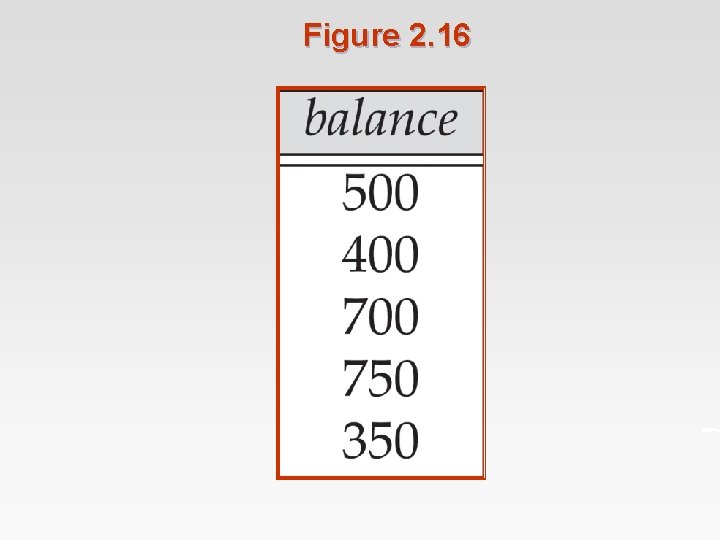

Figure 2. 16

Figure 2. 17 Largest account balance in the bank

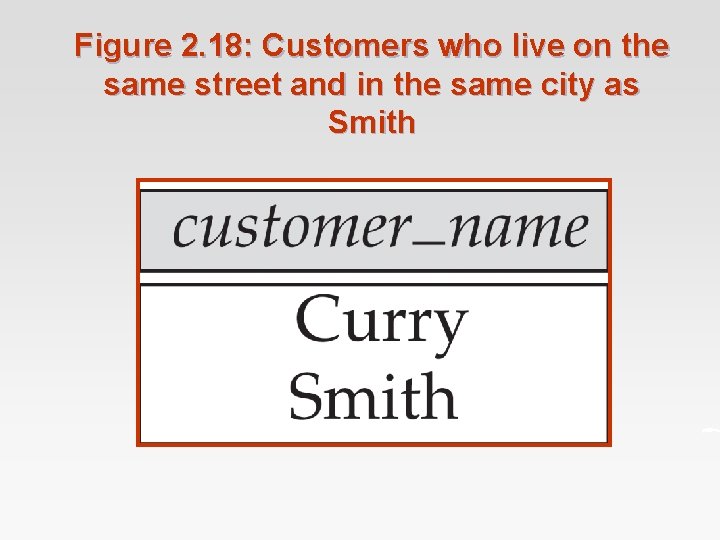

Figure 2. 18: Customers who live on the same street and in the same city as Smith

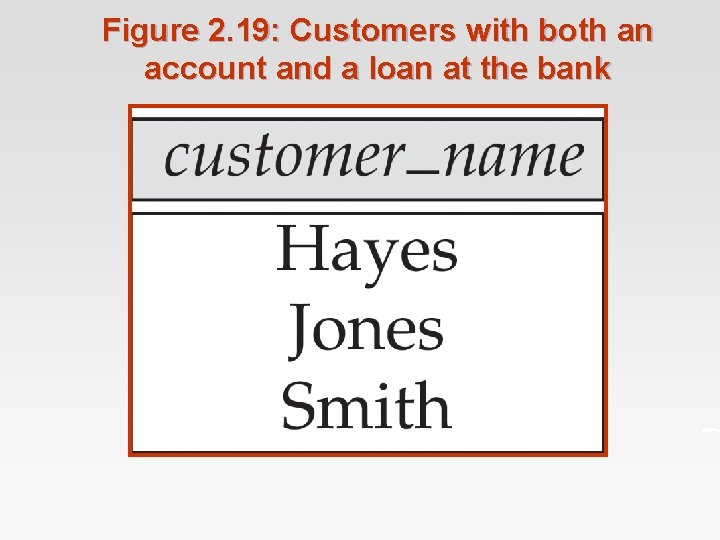

Figure 2. 19: Customers with both an account and a loan at the bank

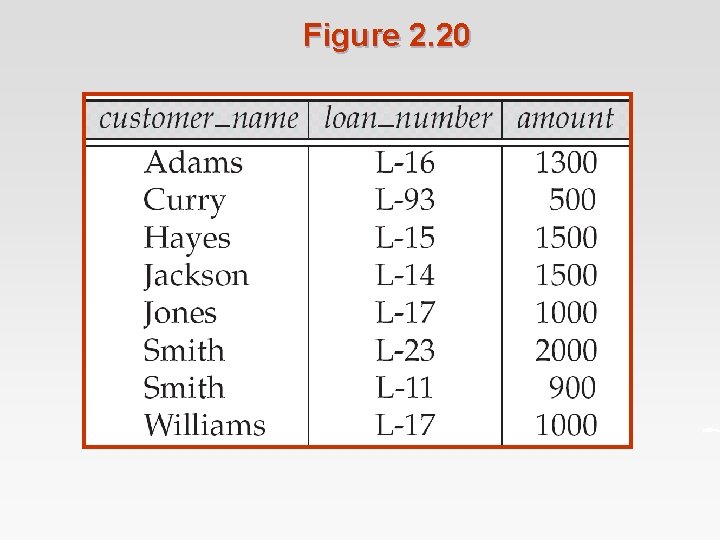

Figure 2. 20

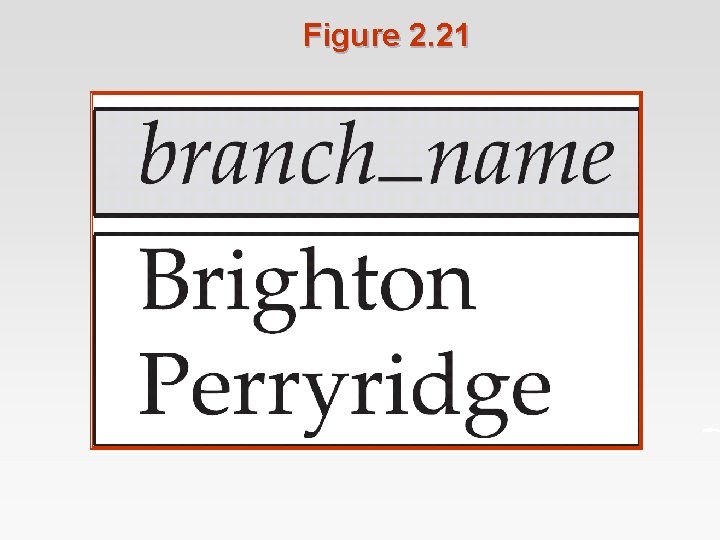

Figure 2. 21

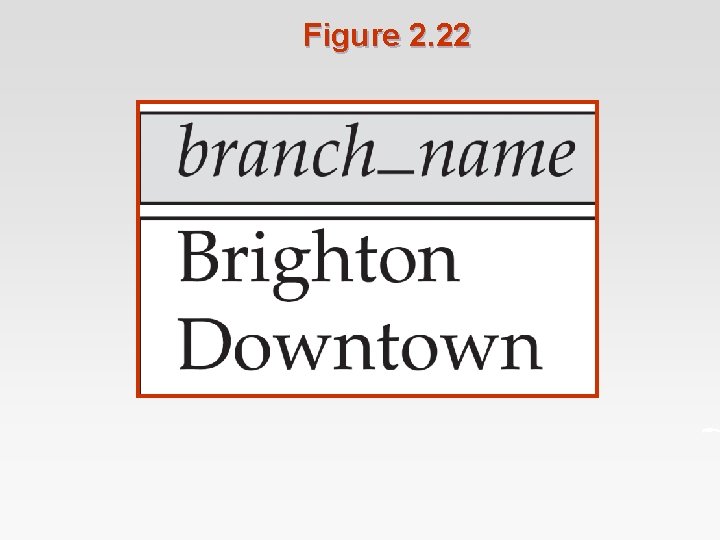

Figure 2. 22

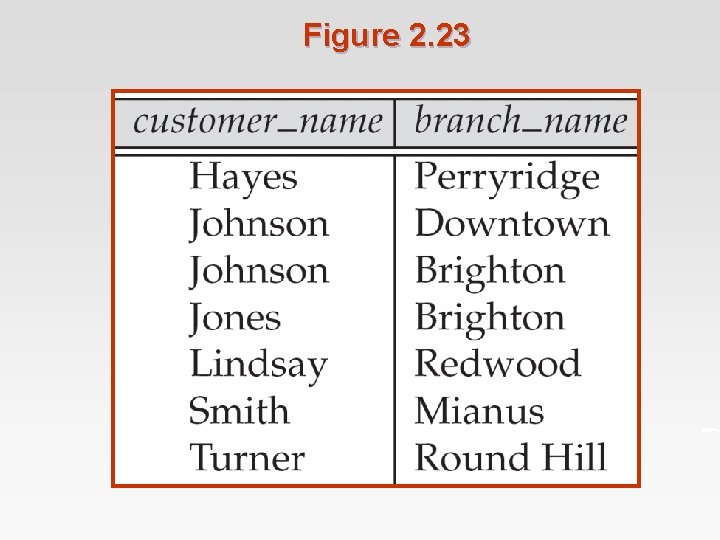

Figure 2. 23

Figure 2. 24: The credit_info relation

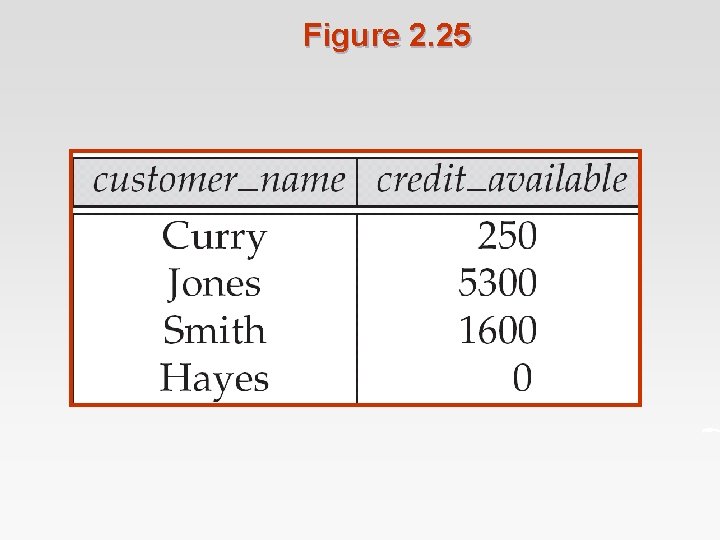

Figure 2. 25

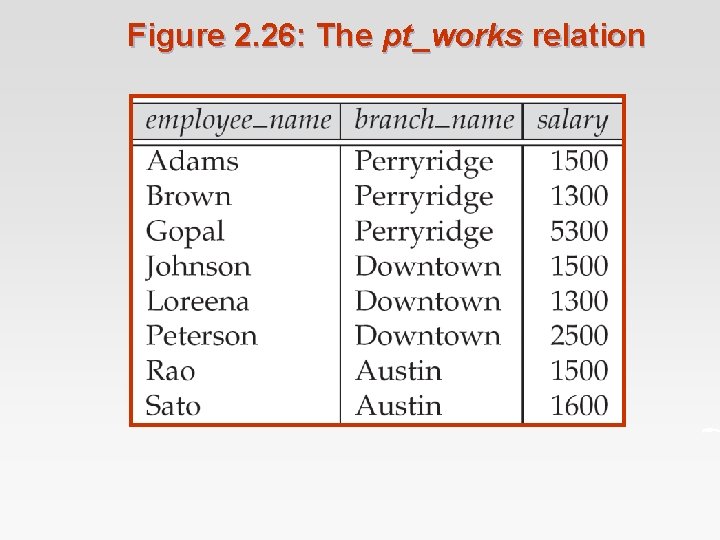

Figure 2. 26: The pt_works relation

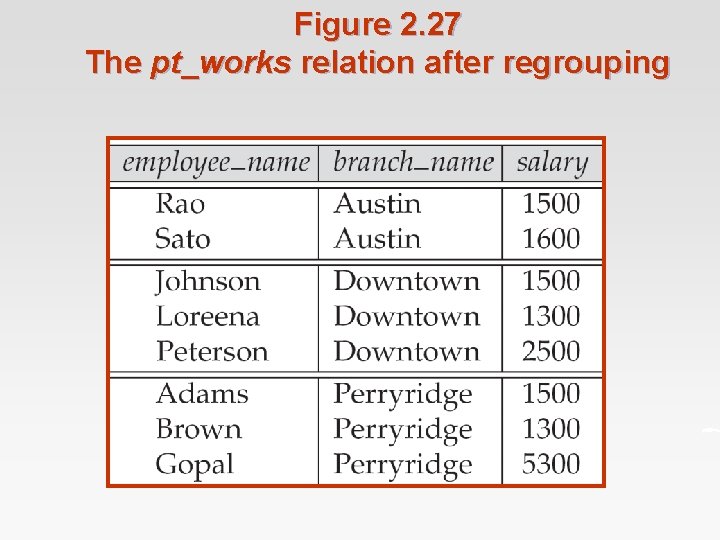

Figure 2. 27 The pt_works relation after regrouping

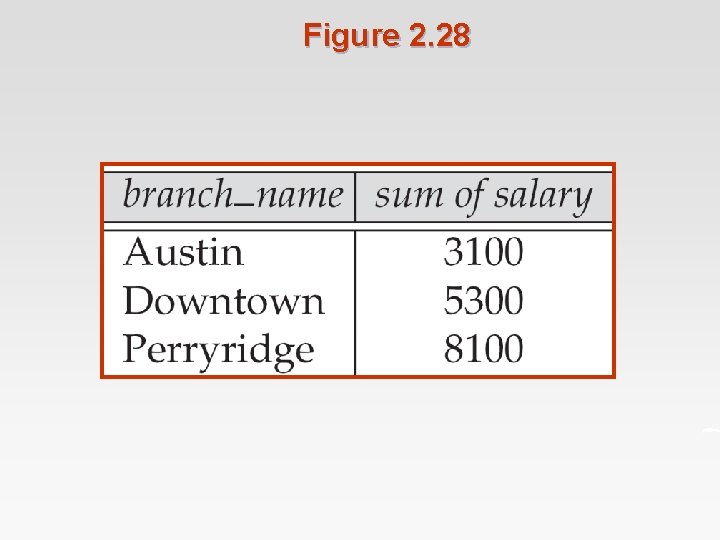

Figure 2. 28

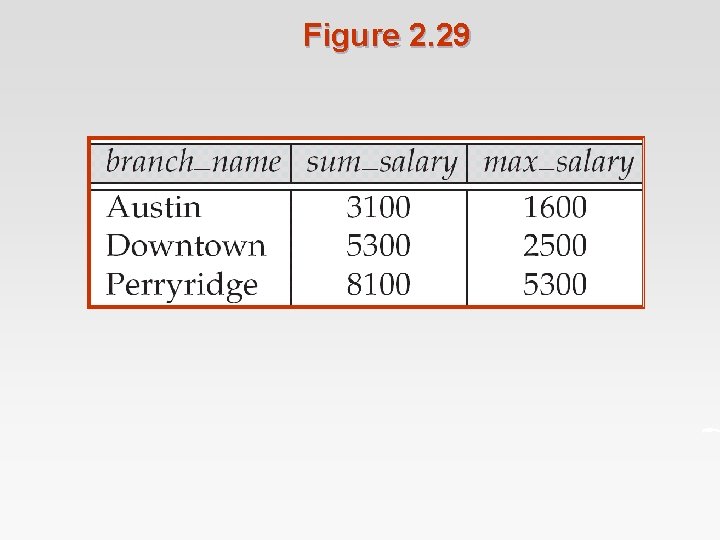

Figure 2. 29

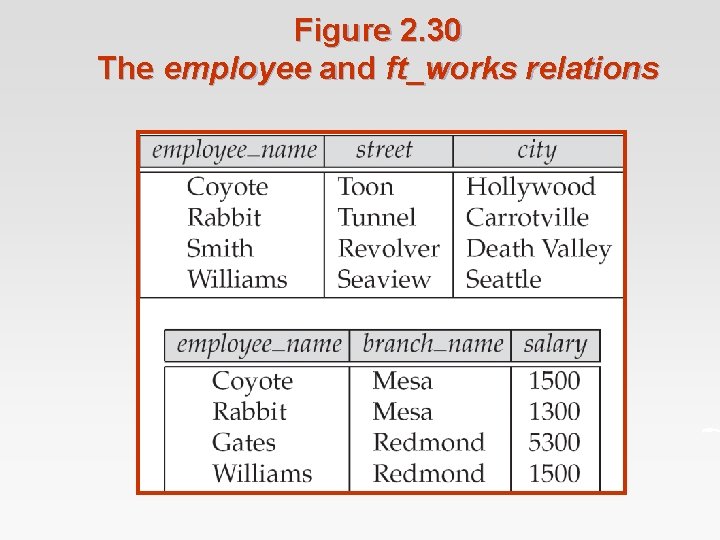

Figure 2. 30 The employee and ft_works relations

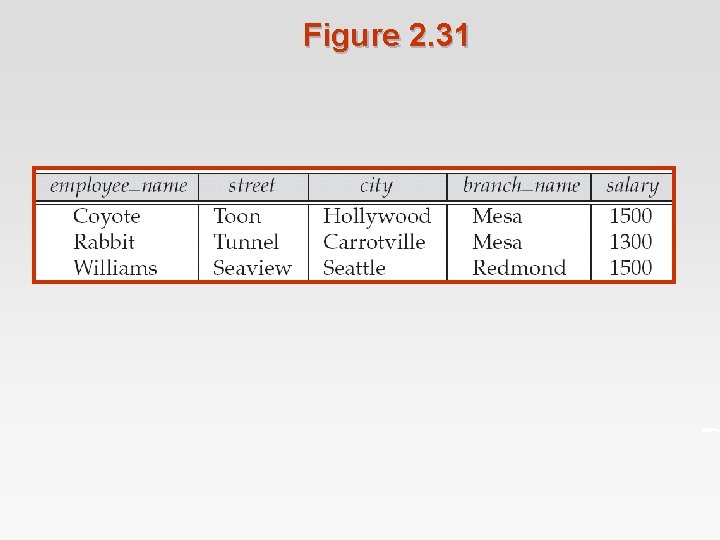

Figure 2. 31

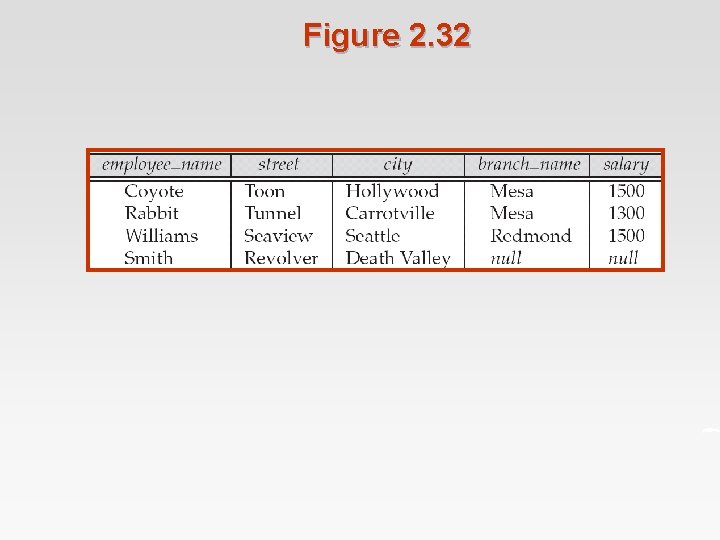

Figure 2. 32

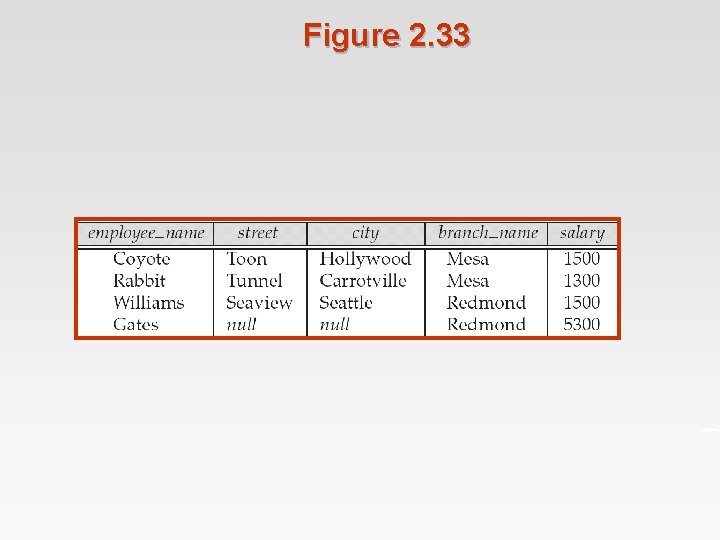

Figure 2. 33

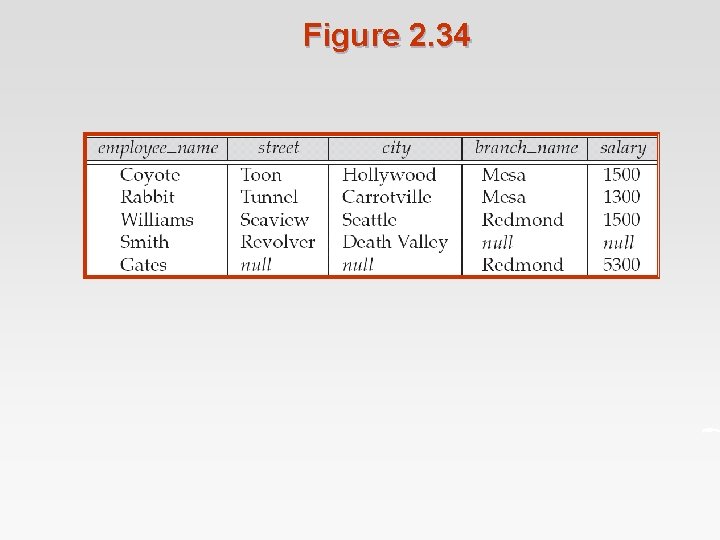

Figure 2. 34

- Slides: 97