Chapter 2 Memory Hierarchy Design Introduction Cache performance

- Slides: 66

Chapter 2 Memory Hierarchy Design • Introduction • Cache performance • Advanced cache optimizations • Memory technology and DRAM optimizations • Virtual machines • Conclusion 1

• Programmers want unlimited amounts of memory with low latency to feed processors • Fast memory technology is more expensive per bit than slower memory • Solution: organize memory system into a hierarchy – Entire addressable memory space available in largest, slowest memory – Incrementally smaller and faster memories, each containing a subset of the memory below it, proceed in steps up toward the processor • Temporal and spatial locality insures that nearly all references can be found in smaller memories – Gives the allusion of a large, fast memory being presented to the processor Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Introduction

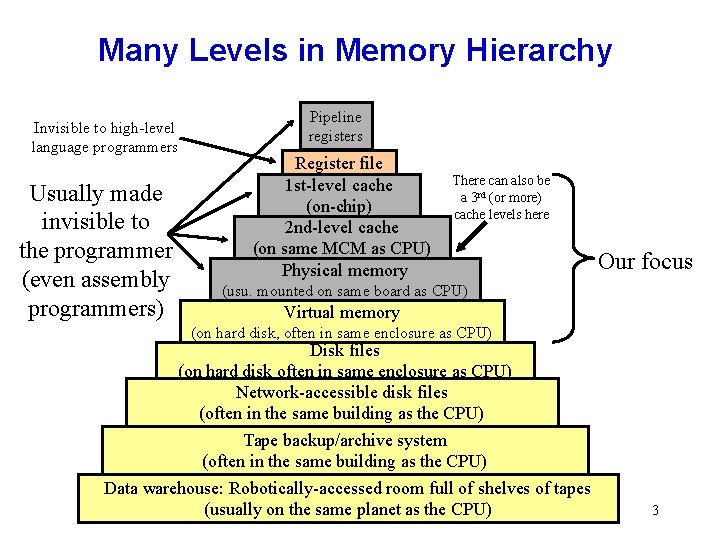

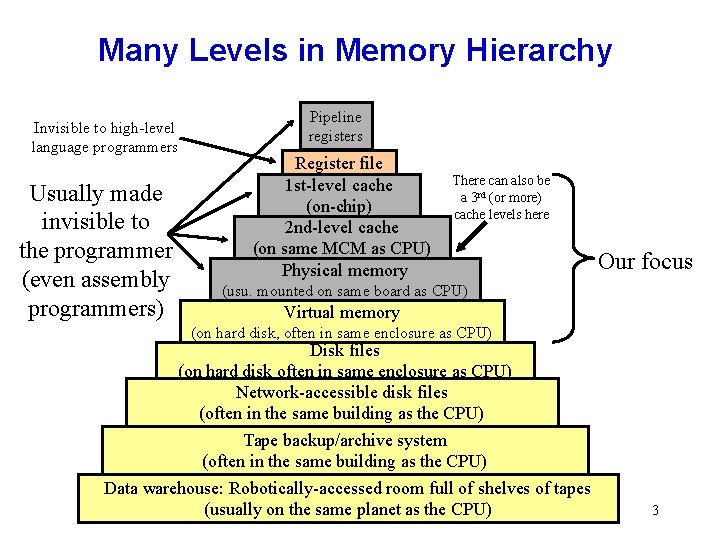

Many Levels in Memory Hierarchy Invisible to high-level language programmers Usually made invisible to the programmer (even assembly programmers) Pipeline registers Register file 1 st-level cache (on-chip) 2 nd-level cache (on same MCM as CPU) Physical memory There can also be a 3 rd (or more) cache levels here Our focus (usu. mounted on same board as CPU) Virtual memory (on hard disk, often in same enclosure as CPU) Disk files (on hard disk often in same enclosure as CPU) Network-accessible disk files (often in the same building as the CPU) Tape backup/archive system (often in the same building as the CPU) Data warehouse: Robotically-accessed room full of shelves of tapes (usually on the same planet as the CPU) 3

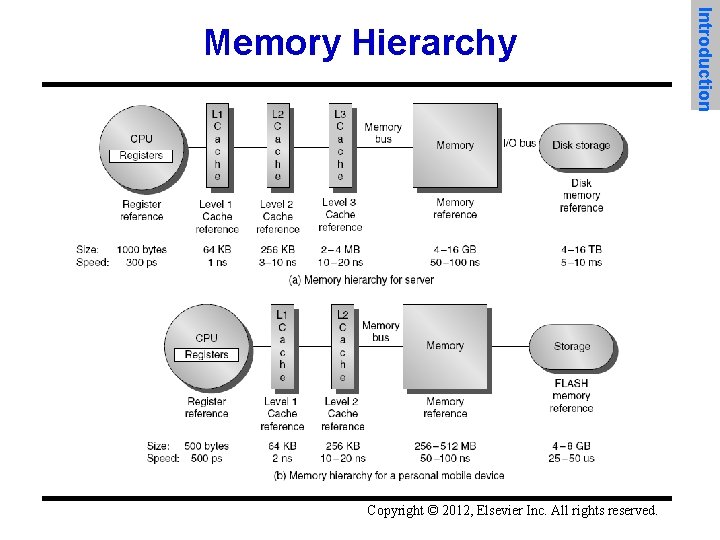

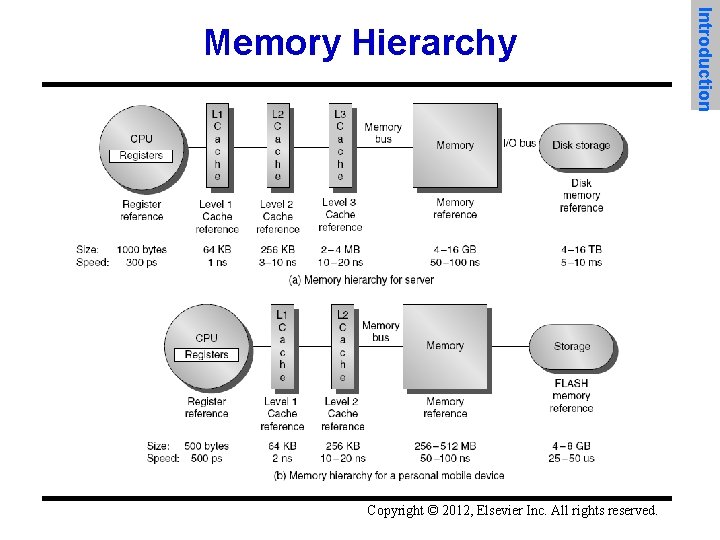

Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Introduction Memory Hierarchy

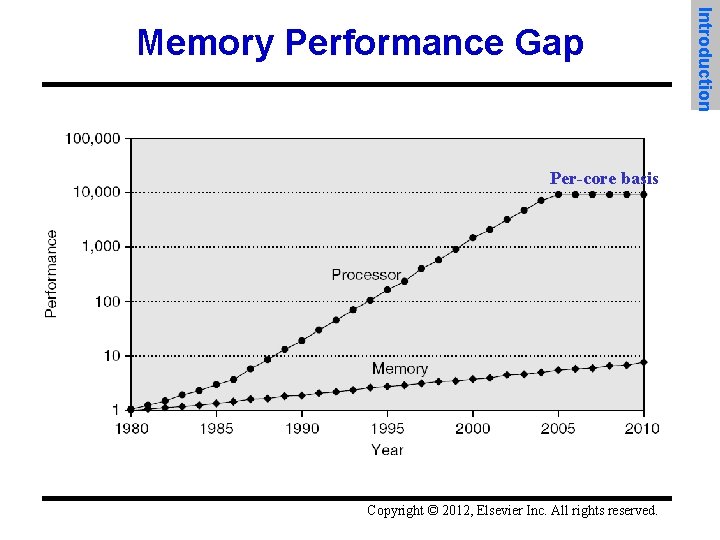

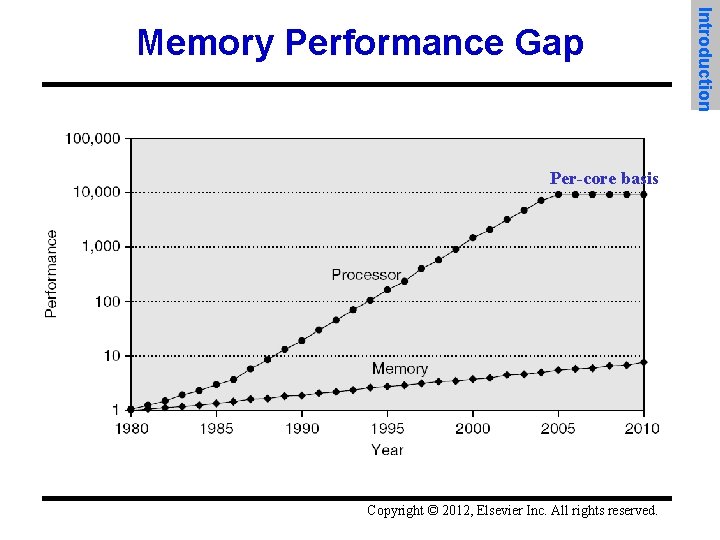

Per-core basis Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Introduction Memory Performance Gap

• Memory hierarchy design becomes more crucial with recent multi-core processors: – Aggregate peak bandwidth grows with # cores: • Intel Core i 7 can generate two references per core per clock • Four cores and 3. 2 GHz clock – 25. 6 billion 64 -bit data references/second + – 12. 8 billion 128 -bit instruction references – = 409. 6 GB/s! (1/3. 2 GHz = 3. 2 billion*4(32 bits) = 12. 8 b) • DRAM bandwidth is only 6% of this (25 GB/s, 3 channels) • Requires: – Multi-port, pipelined caches – Two levels of cache per core – Shared third-level cache on chip Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Introduction Memory Hierarchy Design

• High-end microprocessors have >10 MB on-chip last-level cache (i 7 has 15 MB) to hide memory latency – Consumes large amount of area and power budget • Can be even bigger with off-chip DRAM cache Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Introduction Performance and Power

• When a word is not found in the cache, a miss occurs: – Fetch word from lower level in hierarchy, requiring a higher latency reference – Lower level may be another cache or the main memory – Also fetch the other words contained within the block • Takes advantage of spatial locality – Place block into cache in any location within its set, determined by address • block address MOD number of sets Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Introduction Memory Hierarchy Basics

• n sets => n-way set associative – Direct-mapped cache => one block per set – Fully associative => one set • Writing to cache: two strategies – Write-through • Immediately update lower levels of hierarchy – Write-back • Only update lower levels of hierarchy when an updated block is replaced • – Both strategies use write buffer to make writes asynchronous Write miss: Write-allocate, write-around Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Introduction Memory Hierarchy Basics

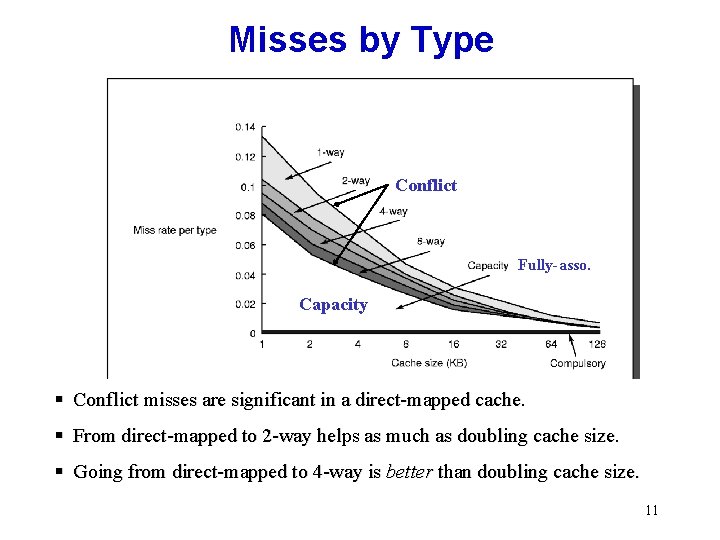

• Miss rate – Fraction of cache access that result in a miss • Causes of misses – Compulsory • First reference to a block – Capacity • Blocks discarded and later retrieved – Conflict • Program makes repeated references to multiple addresses from different blocks that map to the same location in the cache – Coherence miss (in multi-core, later!) Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Introduction Memory Hierarchy Basics

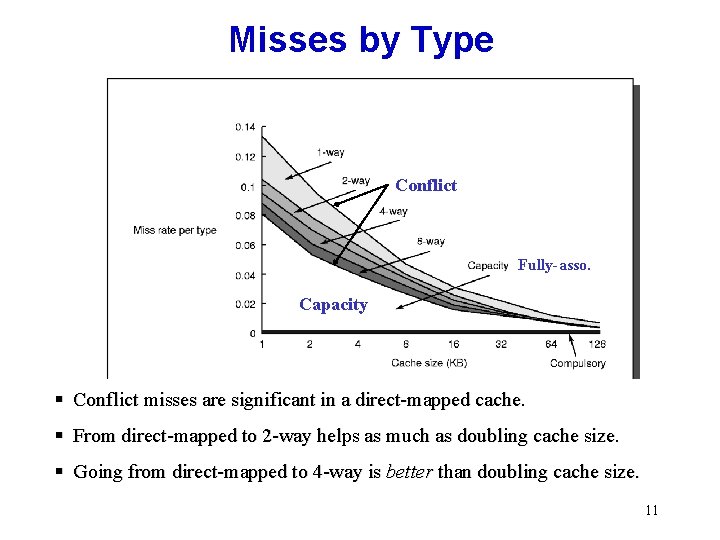

Misses by Type Conflict Fully-asso. Capacity § Conflict misses are significant in a direct-mapped cache. § From direct-mapped to 2 -way helps as much as doubling cache size. § Going from direct-mapped to 4 -way is better than doubling cache size. 11

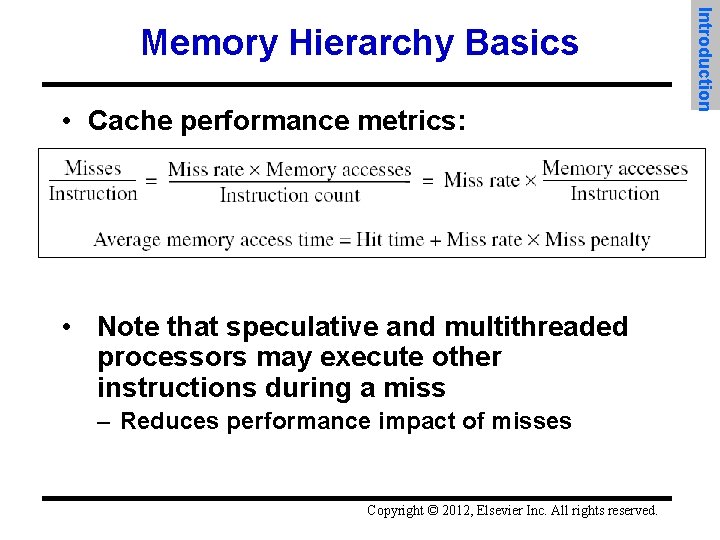

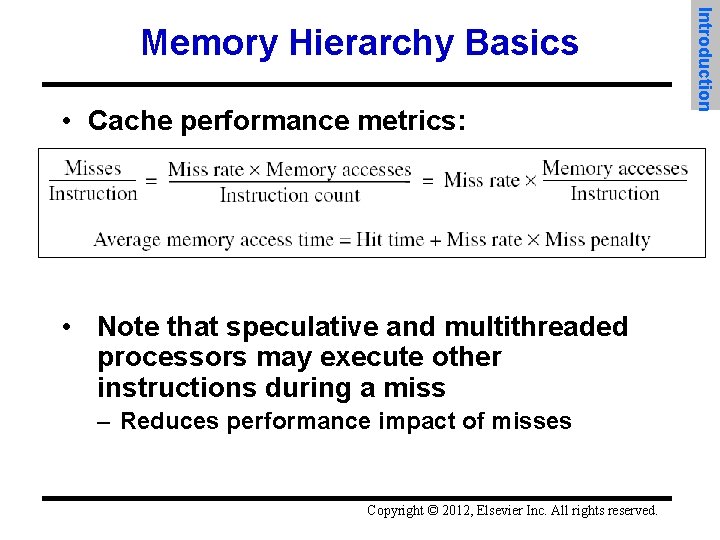

• Cache performance metrics: • Note that speculative and multithreaded processors may execute other instructions during a miss – Reduces performance impact of misses Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Introduction Memory Hierarchy Basics

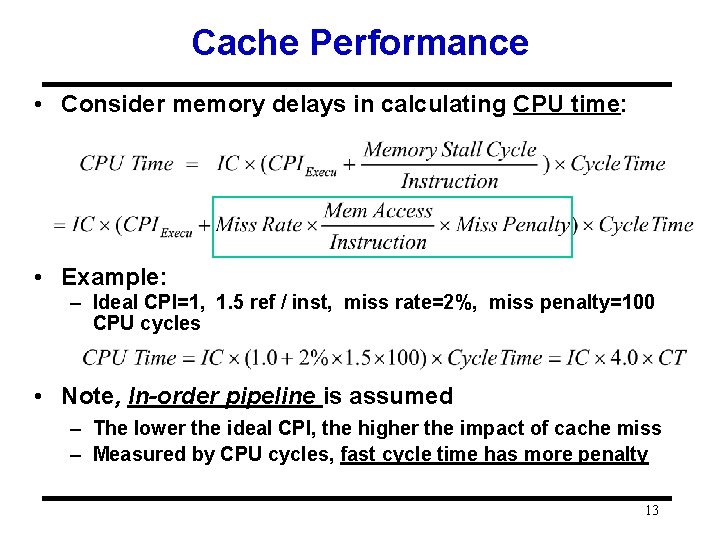

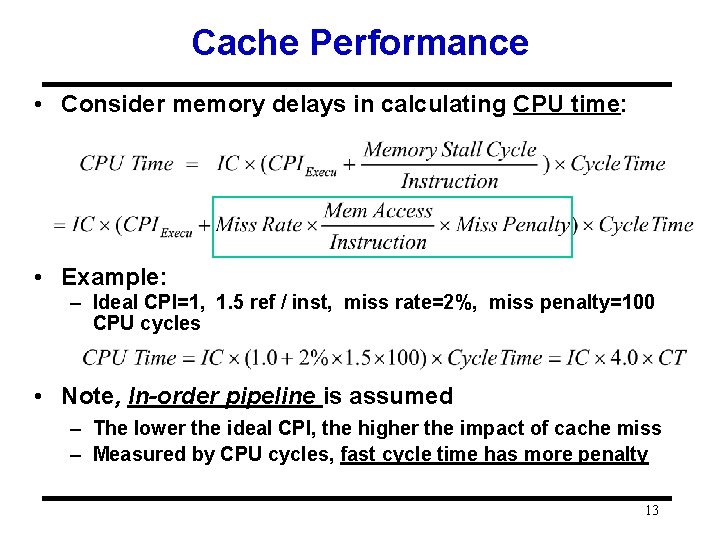

Cache Performance • Consider memory delays in calculating CPU time: • Example: – Ideal CPI=1, 1. 5 ref / inst, miss rate=2%, miss penalty=100 CPU cycles • Note, In-order pipeline is assumed – The lower the ideal CPI, the higher the impact of cache miss – Measured by CPU cycles, fast cycle time has more penalty 13

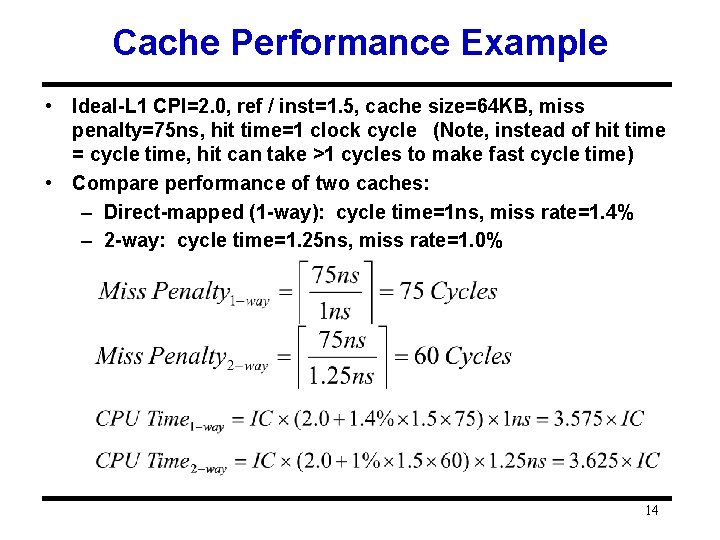

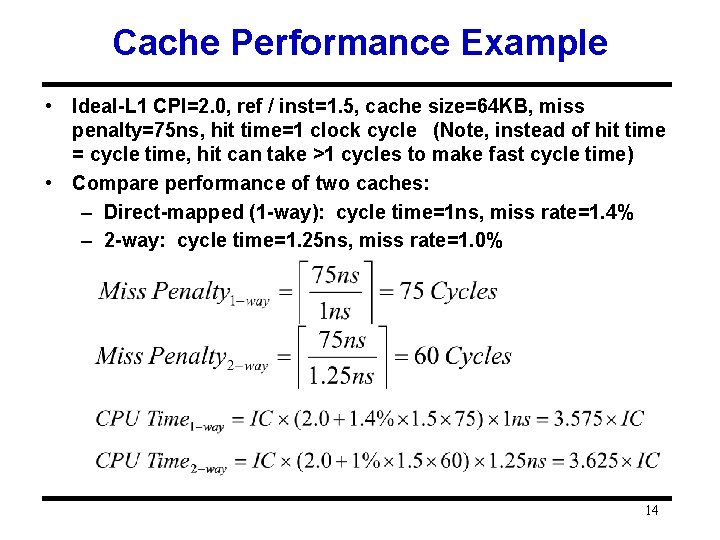

Cache Performance Example • Ideal-L 1 CPI=2. 0, ref / inst=1. 5, cache size=64 KB, miss penalty=75 ns, hit time=1 clock cycle (Note, instead of hit time = cycle time, hit can take >1 cycles to make fast cycle time) • Compare performance of two caches: – Direct-mapped (1 -way): cycle time=1 ns, miss rate=1. 4% – 2 -way: cycle time=1. 25 ns, miss rate=1. 0% 14

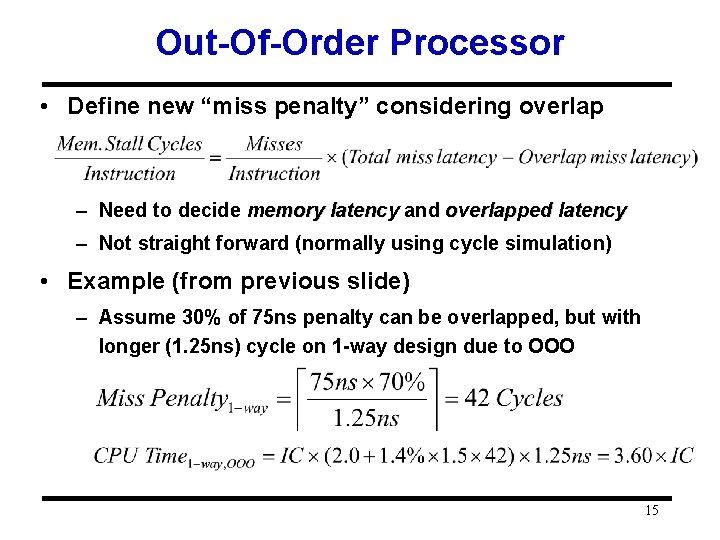

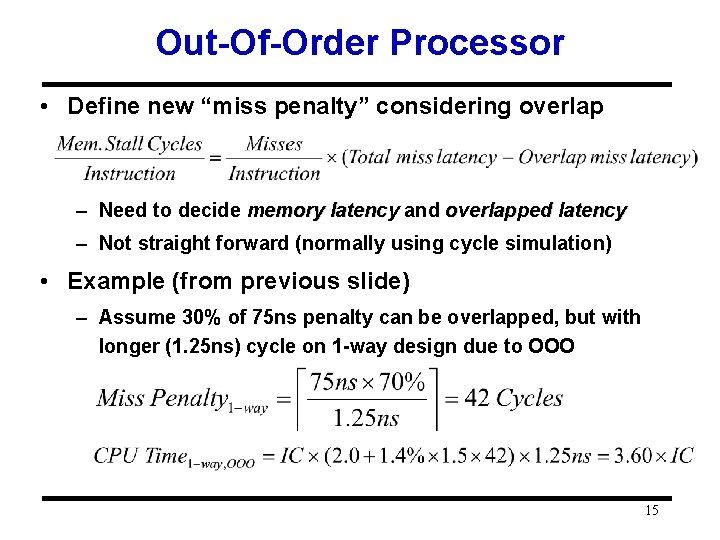

Out-Of-Order Processor • Define new “miss penalty” considering overlap – Need to decide memory latency and overlapped latency – Not straight forward (normally using cycle simulation) • Example (from previous slide) – Assume 30% of 75 ns penalty can be overlapped, but with longer (1. 25 ns) cycle on 1 -way design due to OOO 15

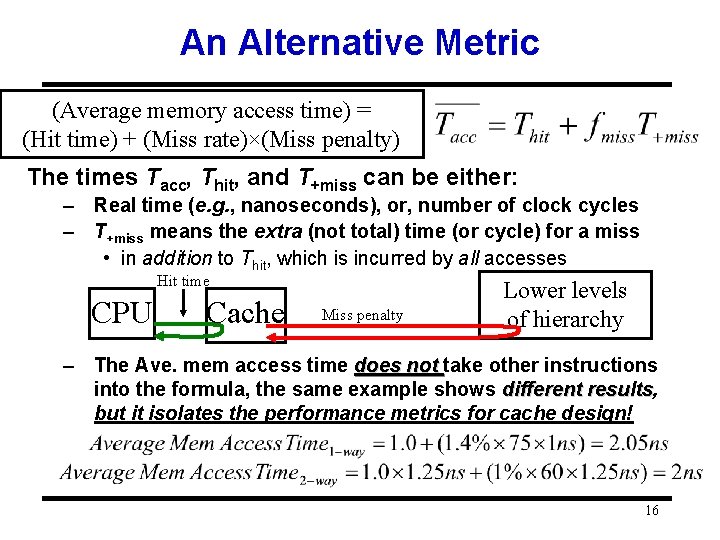

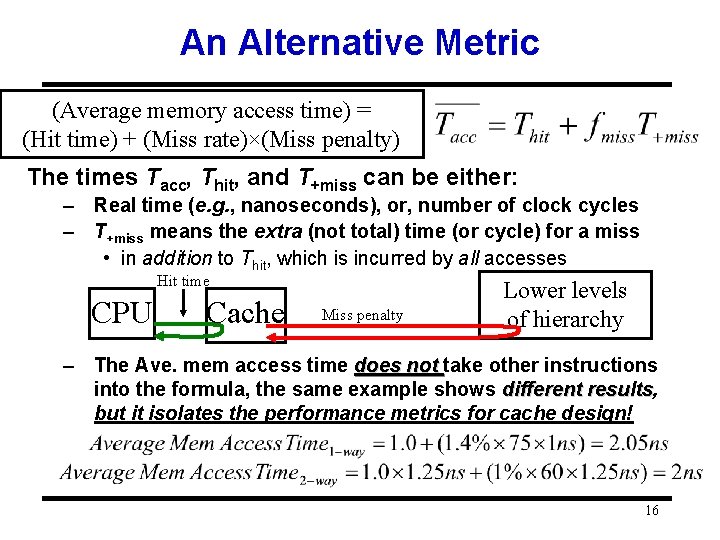

An Alternative Metric (Average memory access time) = (Hit time) + (Miss rate)×(Miss penalty) The times Tacc, Thit, and T+miss can be either: – Real time (e. g. , nanoseconds), or, number of clock cycles – T+miss means the extra (not total) time (or cycle) for a miss • in addition to Thit, which is incurred by all accesses Hit time CPU Cache Miss penalty Lower levels of hierarchy – The Ave. mem access time does not take other instructions into the formula, the same example shows different results, results but it isolates the performance metrics for cache design! 16

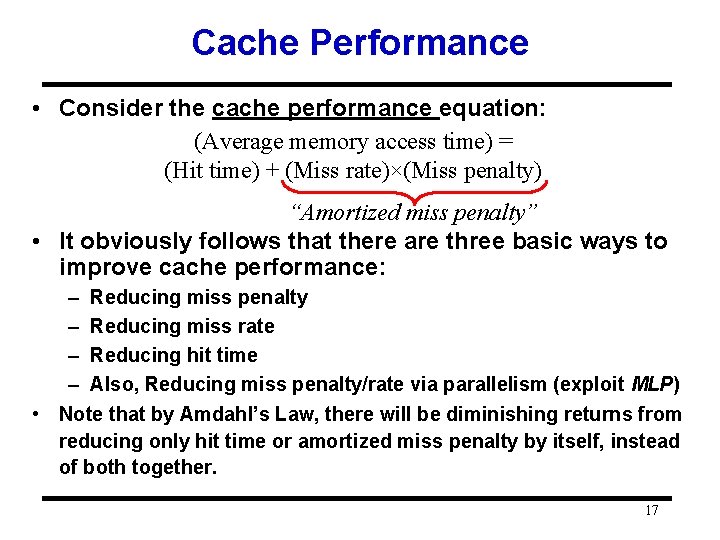

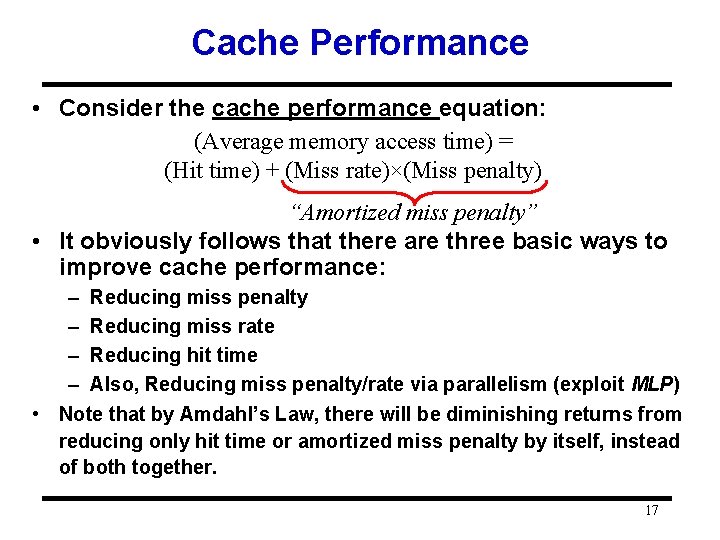

Cache Performance • Consider the cache performance equation: (Average memory access time) = (Hit time) + (Miss rate)×(Miss penalty) “Amortized miss penalty” • It obviously follows that there are three basic ways to improve cache performance: – Reducing miss penalty – Reducing miss rate – Reducing hit time – Also, Reducing miss penalty/rate via parallelism (exploit MLP) • Note that by Amdahl’s Law, there will be diminishing returns from reducing only hit time or amortized miss penalty by itself, instead of both together. 17

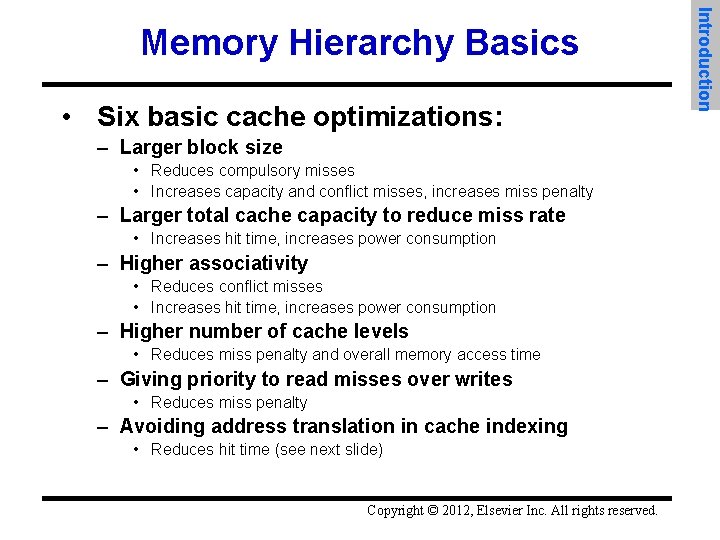

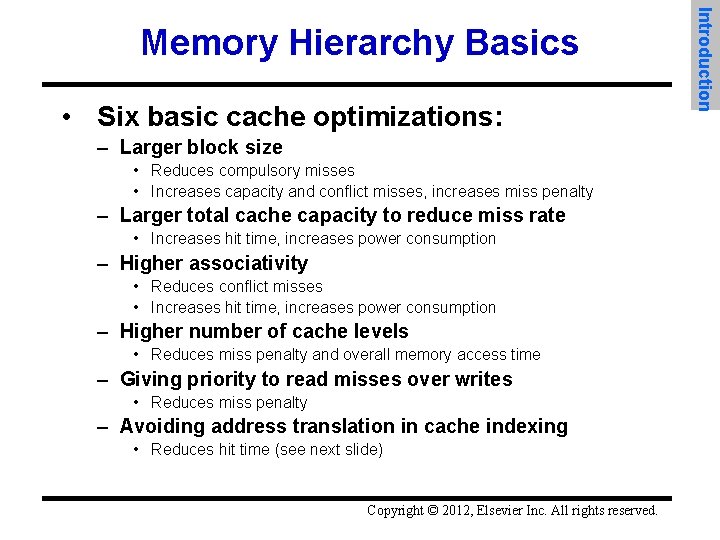

• Six basic cache optimizations: – Larger block size • Reduces compulsory misses • Increases capacity and conflict misses, increases miss penalty – Larger total cache capacity to reduce miss rate • Increases hit time, increases power consumption – Higher associativity • Reduces conflict misses • Increases hit time, increases power consumption – Higher number of cache levels • Reduces miss penalty and overall memory access time – Giving priority to read misses over writes • Reduces miss penalty – Avoiding address translation in cache indexing • Reduces hit time (see next slide) Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Introduction Memory Hierarchy Basics

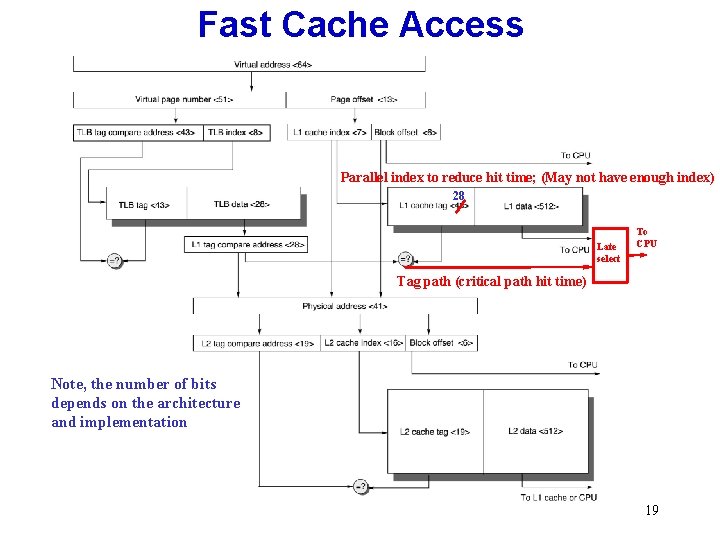

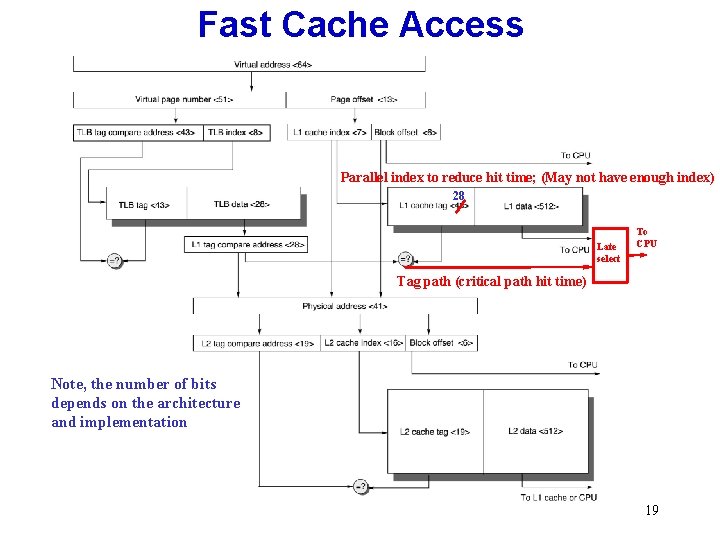

Fast Cache Access Parallel index to reduce hit time; (May not have enough index) 28 Late select To CPU Tag path (critical path hit time) Note, the number of bits depends on the architecture and implementation 19

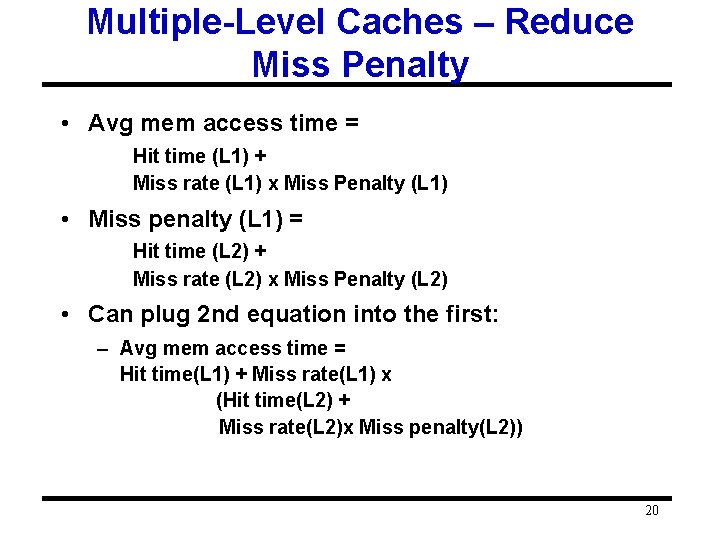

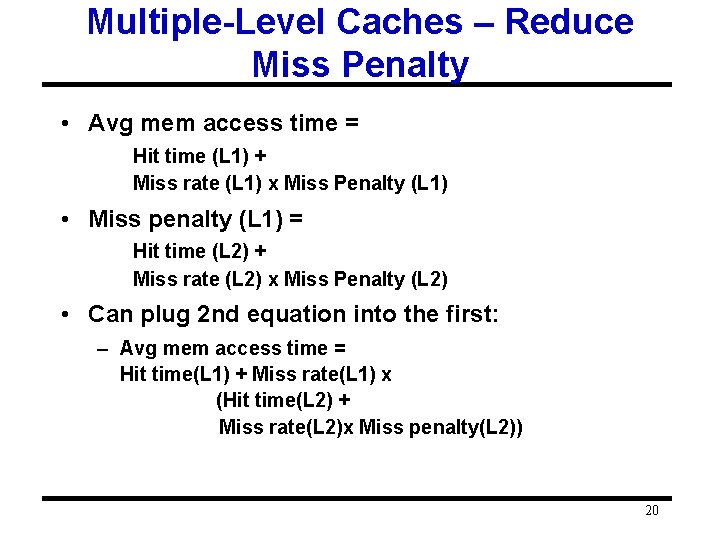

Multiple-Level Caches – Reduce Miss Penalty • Avg mem access time = Hit time (L 1) + Miss rate (L 1) x Miss Penalty (L 1) • Miss penalty (L 1) = Hit time (L 2) + Miss rate (L 2) x Miss Penalty (L 2) • Can plug 2 nd equation into the first: – Avg mem access time = Hit time(L 1) + Miss rate(L 1) x (Hit time(L 2) + Miss rate(L 2)x Miss penalty(L 2)) 20

Multi-level Cache Terminology • “Local miss rate” – The miss rate of one hierarchy level by itself. – # of misses at that level / # accesses to that level – e. g. Miss rate(L 1), Miss rate(L 2) • “Global miss rate” – The miss rate of a whole group of hierarchy levels – # of accesses coming out of that group (to lower levels) / # of accesses to that group – Generally this is the product of the miss rates at each level in the group. – Global L 2 Miss rate = Miss rate(L 1) × Local Miss rate(L 2), more related to overall cache performance 21

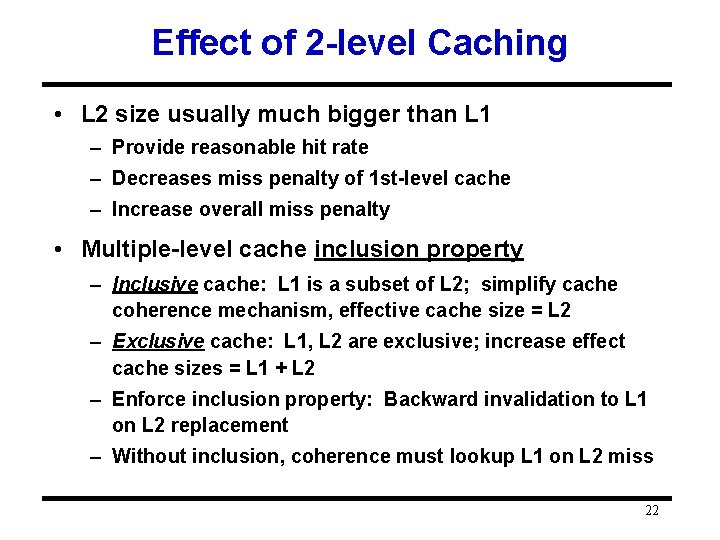

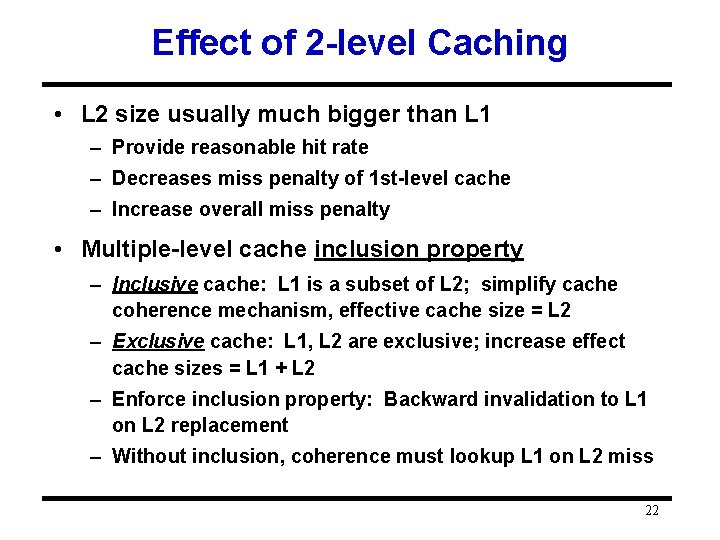

Effect of 2 -level Caching • L 2 size usually much bigger than L 1 – Provide reasonable hit rate – Decreases miss penalty of 1 st-level cache – Increase overall miss penalty • Multiple-level cache inclusion property – Inclusive cache: L 1 is a subset of L 2; simplify cache coherence mechanism, effective cache size = L 2 – Exclusive cache: L 1, L 2 are exclusive; increase effect cache sizes = L 1 + L 2 – Enforce inclusion property: Backward invalidation to L 1 on L 2 replacement – Without inclusion, coherence must lookup L 1 on L 2 miss 22

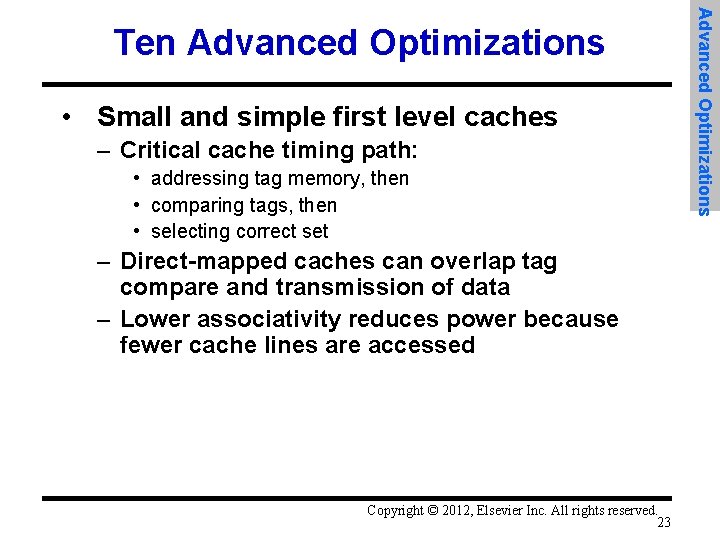

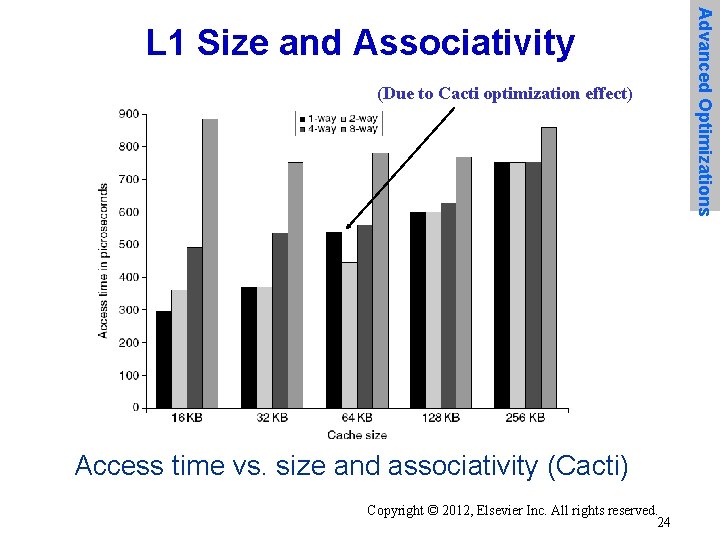

• Small and simple first level caches – Critical cache timing path: • addressing tag memory, then • comparing tags, then • selecting correct set – Direct-mapped caches can overlap tag compare and transmission of data – Lower associativity reduces power because fewer cache lines are accessed Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 23 Advanced Optimizations Ten Advanced Optimizations

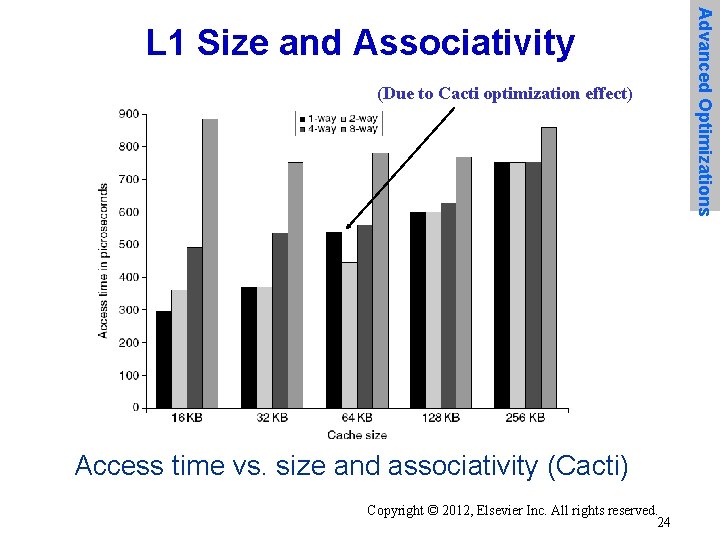

(Due to Cacti optimization effect) Access time vs. size and associativity (Cacti) Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 24 Advanced Optimizations L 1 Size and Associativity

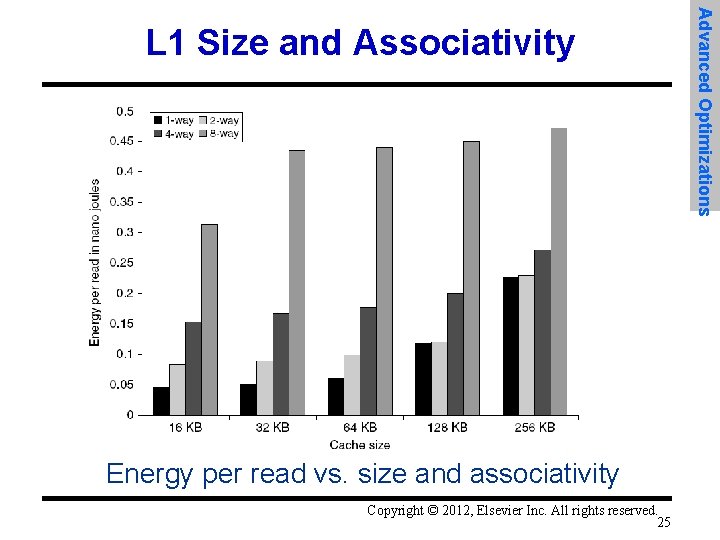

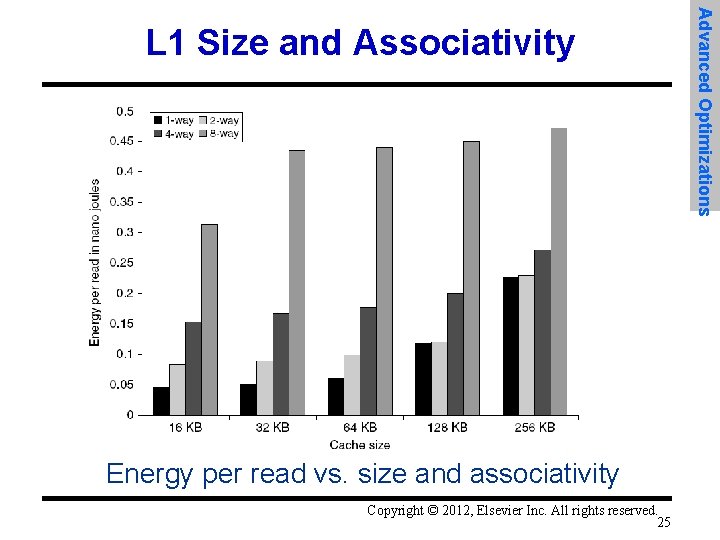

Energy per read vs. size and associativity Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 25 Advanced Optimizations L 1 Size and Associativity

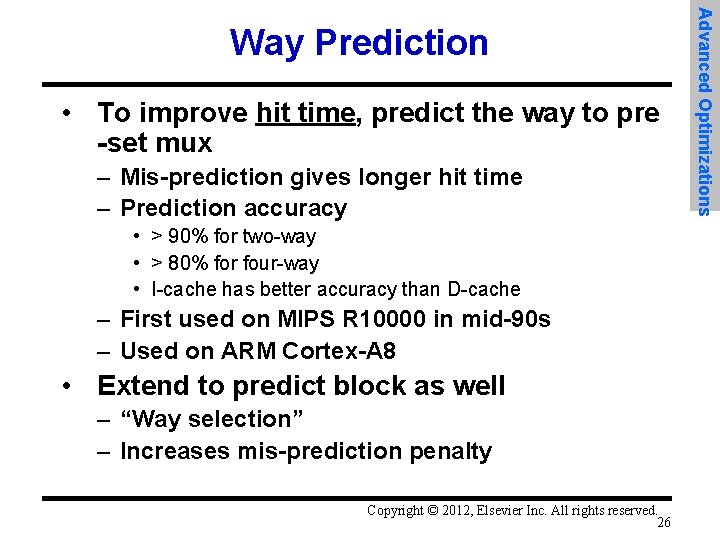

• To improve hit time, predict the way to pre -set mux – Mis-prediction gives longer hit time – Prediction accuracy • > 90% for two-way • > 80% for four-way • I-cache has better accuracy than D-cache – First used on MIPS R 10000 in mid-90 s – Used on ARM Cortex-A 8 • Extend to predict block as well – “Way selection” – Increases mis-prediction penalty Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 26 Advanced Optimizations Way Prediction

• Pipeline cache access to improve bandwidth – Examples: • Pentium: 1 cycle • Pentium Pro – Pentium III: 2 cycles • Pentium 4 – Core i 7: 4 cycles • Increases branch mis-prediction penalty due to longer pipeline stages • Makes it easier to increase associativity Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 27 Advanced Optimizations Pipelining Cache

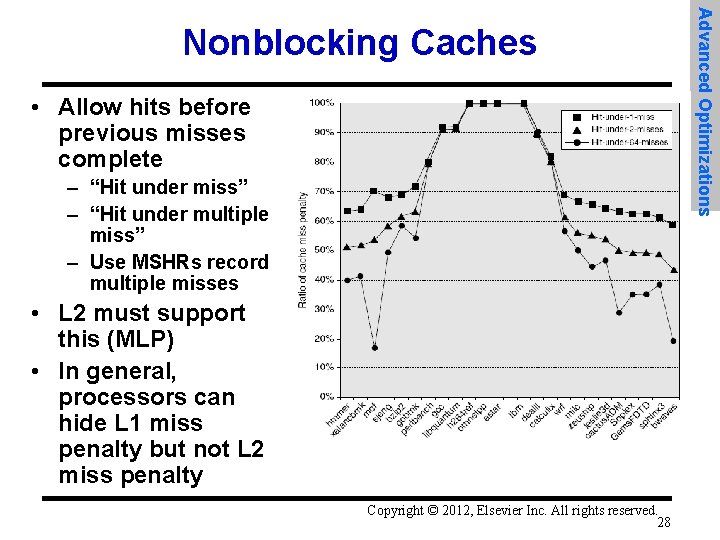

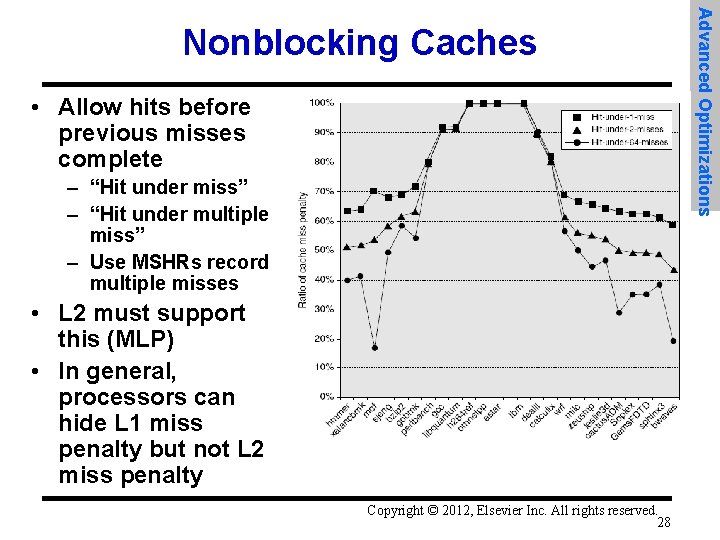

• Allow hits before previous misses complete – “Hit under miss” – “Hit under multiple miss” – Use MSHRs record multiple misses • L 2 must support this (MLP) • In general, processors can hide L 1 miss penalty but not L 2 miss penalty Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 28 Advanced Optimizations Nonblocking Caches

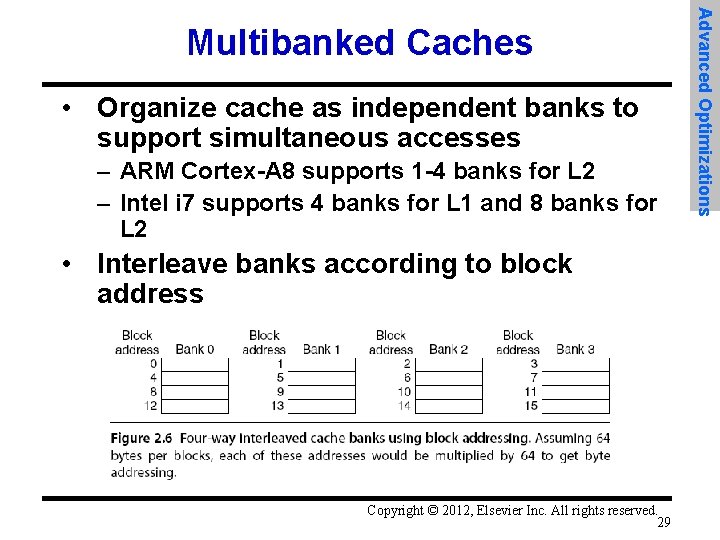

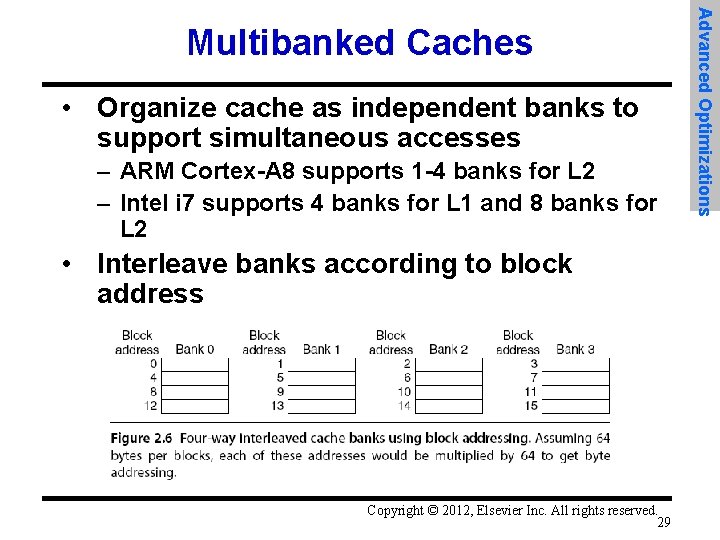

• Organize cache as independent banks to support simultaneous accesses – ARM Cortex-A 8 supports 1 -4 banks for L 2 – Intel i 7 supports 4 banks for L 1 and 8 banks for L 2 • Interleave banks according to block address Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 29 Advanced Optimizations Multibanked Caches

• Critical word first – Request missed word from memory first – Send it to the processor as soon as it arrives • Early restart – Request words in normal order – Send missed work to the processor as soon as it arrives • Effectiveness of these strategies depends on block size and likelihood of another access to the portion of the block that has not yet been fetched Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 30 Advanced Optimizations Critical Word First, Early Restart

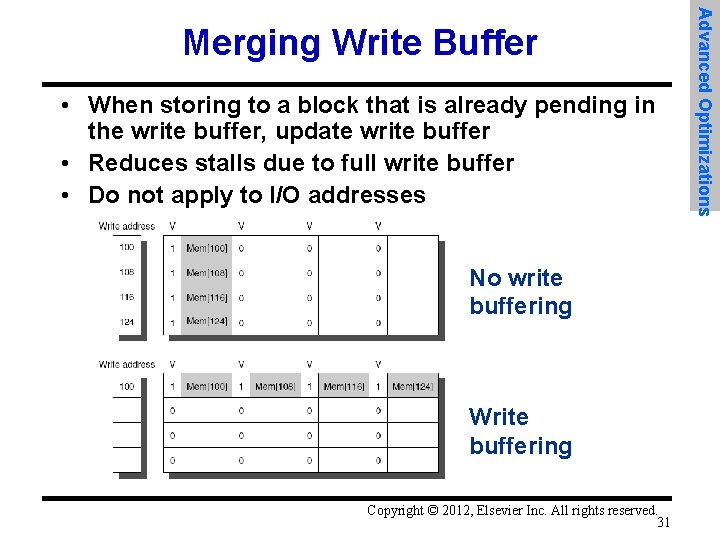

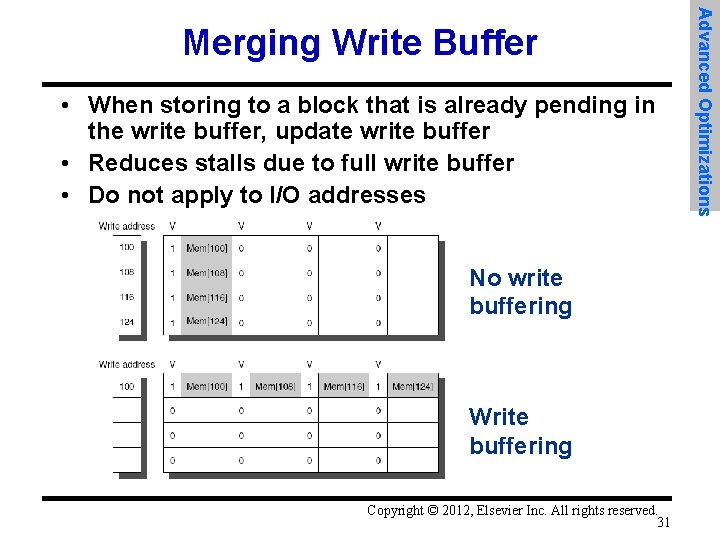

• When storing to a block that is already pending in the write buffer, update write buffer • Reduces stalls due to full write buffer • Do not apply to I/O addresses No write buffering Write buffering Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 31 Advanced Optimizations Merging Write Buffer

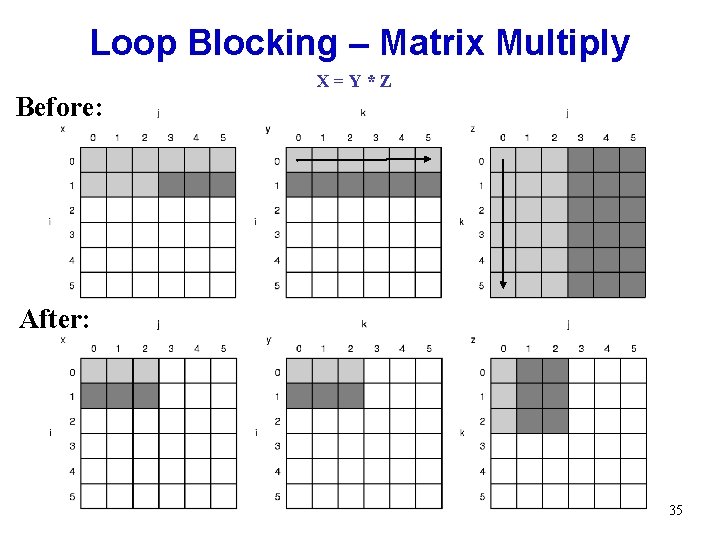

• Loop Interchange – Swap nested loops to access memory in sequential order • Blocking – Instead of accessing entire rows or columns, subdivide matrices into blocks – Requires more memory accesses but improves locality of accesses Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 32 Advanced Optimizations Compiler Optimizations

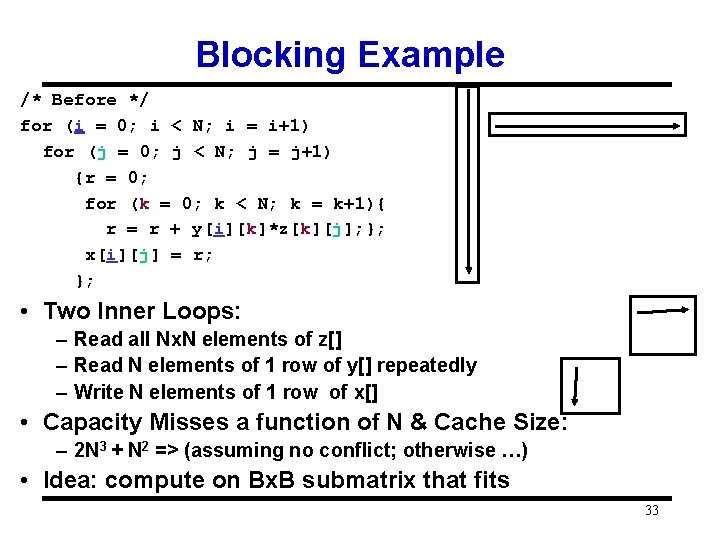

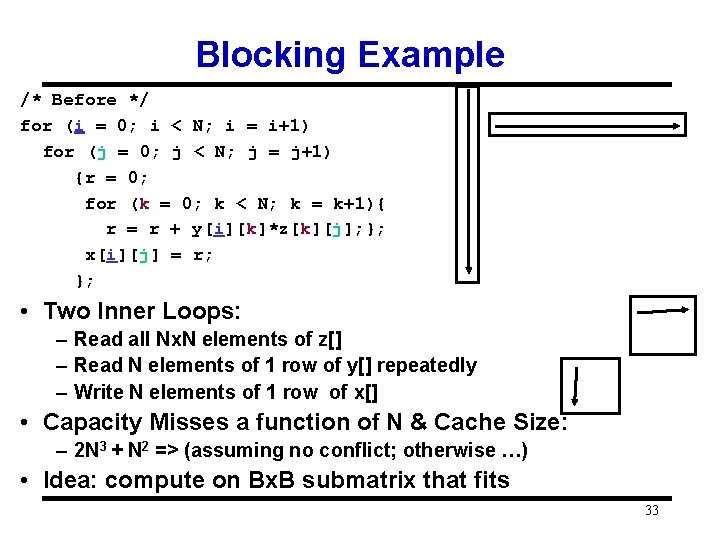

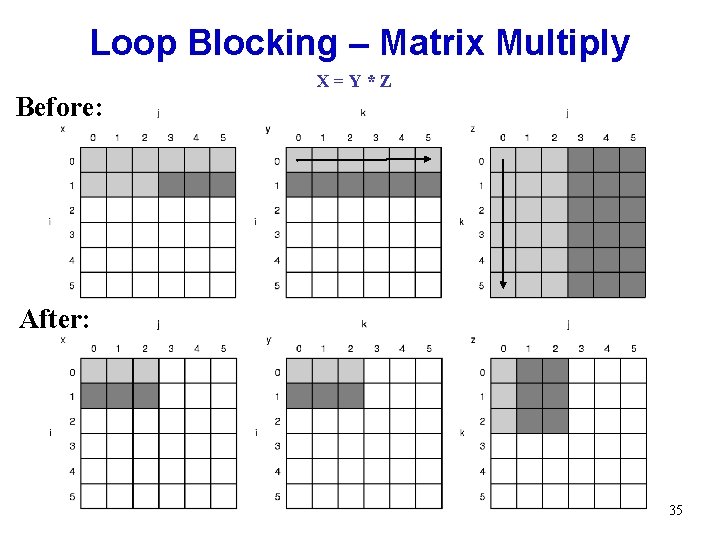

Blocking Example /* Before */ for (i = 0; i < N; i = i+1) for (j = 0; j < N; j = j+1) {r = 0; for (k = 0; k < N; k = k+1){ r = r + y[i][k]*z[k][j]; }; x[i][j] = r; }; • Two Inner Loops: – Read all Nx. N elements of z[] – Read N elements of 1 row of y[] repeatedly – Write N elements of 1 row of x[] • Capacity Misses a function of N & Cache Size: – 2 N 3 + N 2 => (assuming no conflict; otherwise …) • Idea: compute on Bx. B submatrix that fits 33

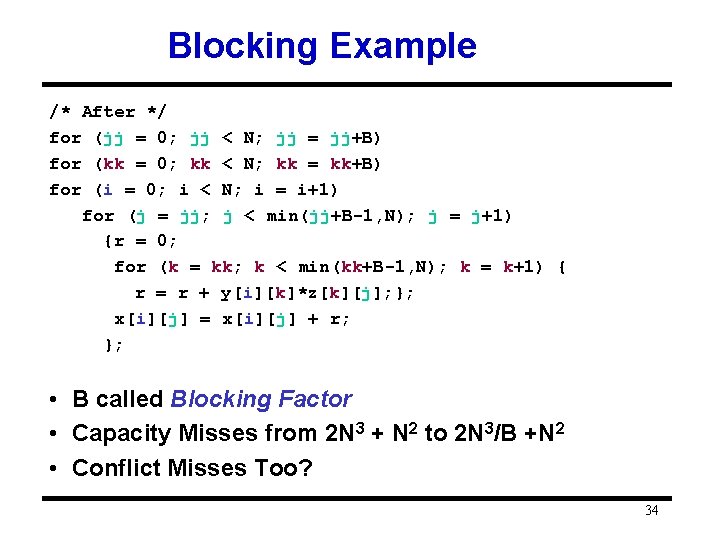

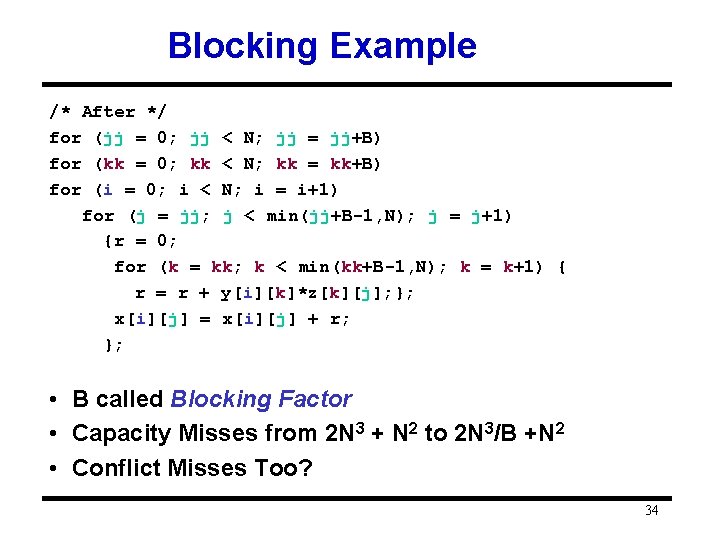

Blocking Example /* After */ for (jj = 0; jj < N; jj = jj+B) for (kk = 0; kk < N; kk = kk+B) for (i = 0; i < N; i = i+1) for (j = jj; j < min(jj+B-1, N); j = j+1) {r = 0; for (k = kk; k < min(kk+B-1, N); k = k+1) { r = r + y[i][k]*z[k][j]; }; x[i][j] = x[i][j] + r; }; • B called Blocking Factor • Capacity Misses from 2 N 3 + N 2 to 2 N 3/B +N 2 • Conflict Misses Too? 34

Loop Blocking – Matrix Multiply X=Y*Z Before: After: 35

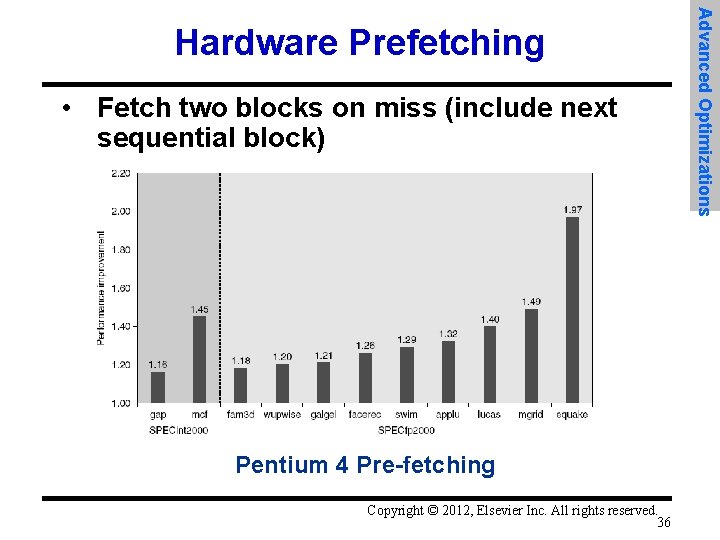

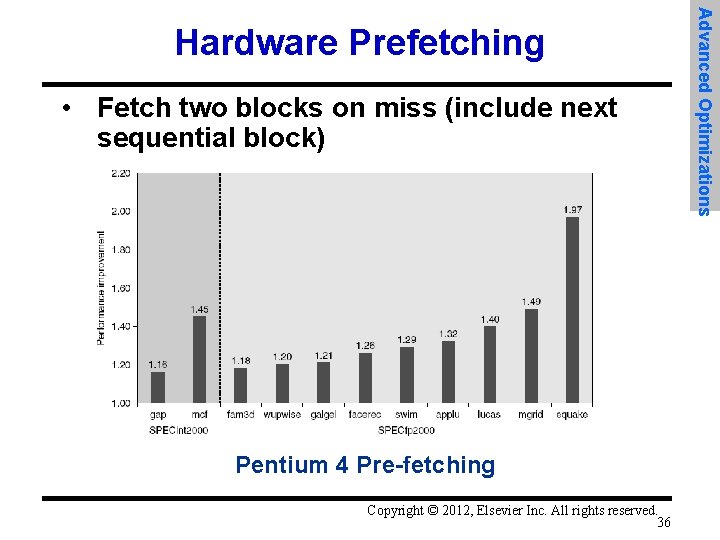

• Fetch two blocks on miss (include next sequential block) Pentium 4 Pre-fetching Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 36 Advanced Optimizations Hardware Prefetching

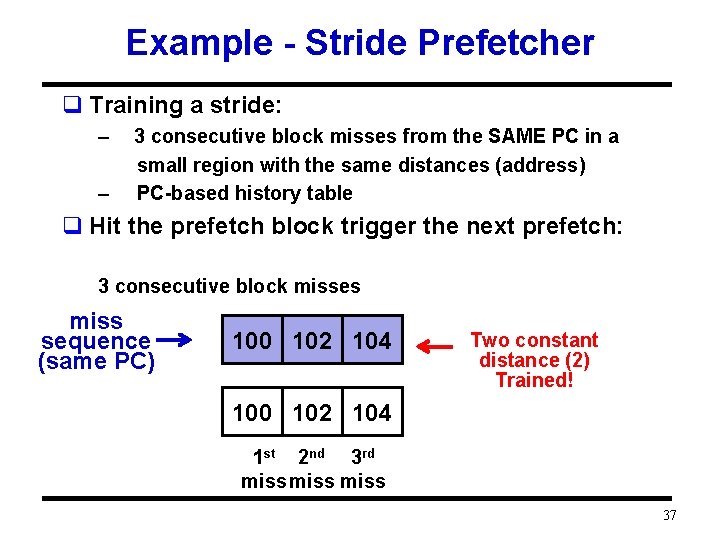

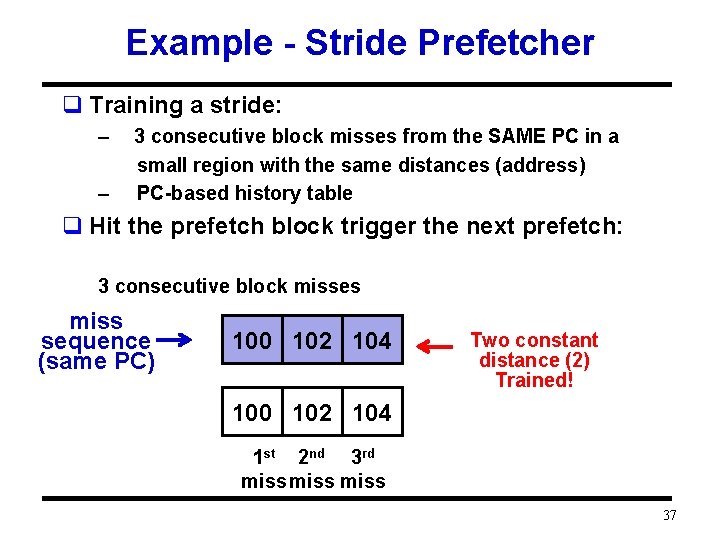

Example - Stride Prefetcher q Training a stride: – – 3 consecutive block misses from the SAME PC in a small region with the same distances (address) PC-based history table q Hit the prefetch block trigger the next prefetch: 3 consecutive block misses miss sequence (same PC) 100 102 104 Two constant distance (2) Trained! 100 102 104 1 st 2 nd 3 rd miss 37

• Insert prefetch instructions before data is needed • Non-faulting: prefetch doesn’t cause exceptions • Register prefetch – Loads data into register • Cache prefetch – Loads data into cache • Combine with loop unrolling and software pipelining Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 38 Advanced Optimizations Compiler Prefetching

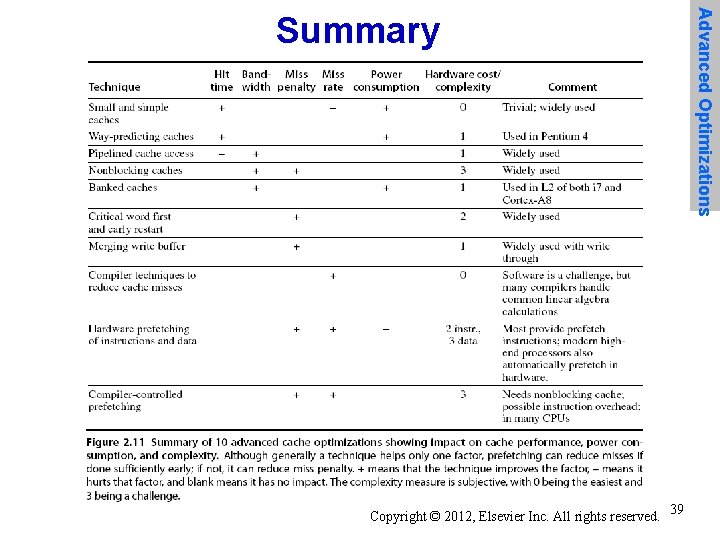

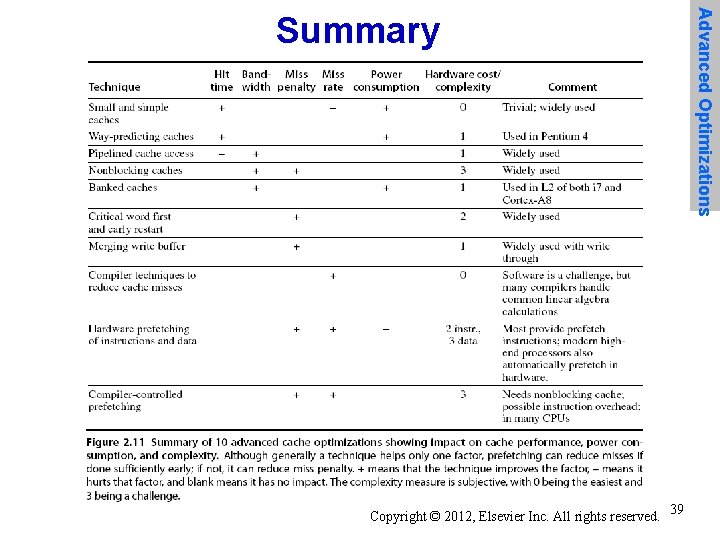

Advanced Optimizations Summary Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 39

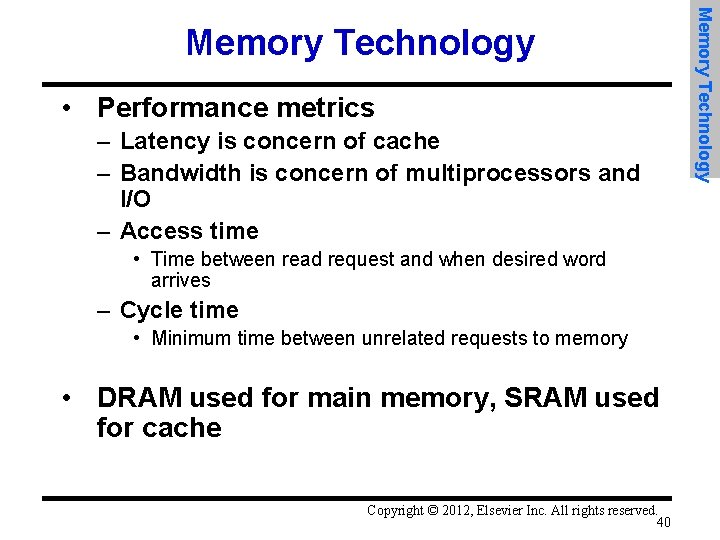

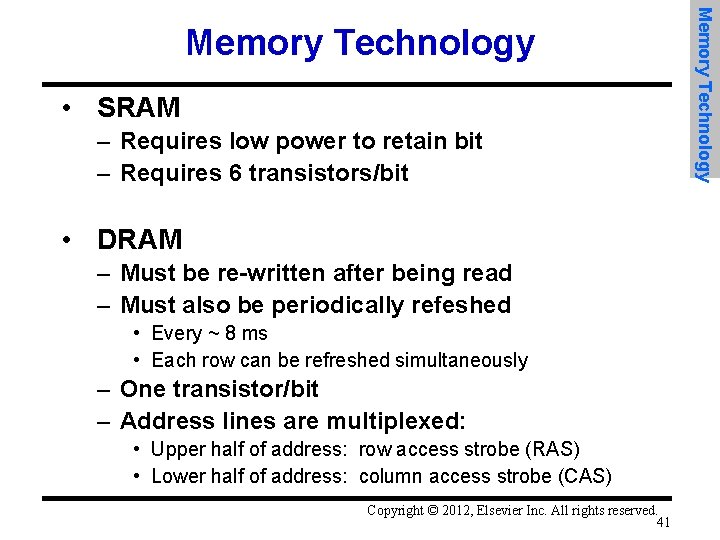

• Performance metrics – Latency is concern of cache – Bandwidth is concern of multiprocessors and I/O – Access time • Time between read request and when desired word arrives – Cycle time • Minimum time between unrelated requests to memory • DRAM used for main memory, SRAM used for cache Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 40 Memory Technology

• SRAM – Requires low power to retain bit – Requires 6 transistors/bit • DRAM – Must be re-written after being read – Must also be periodically refeshed • Every ~ 8 ms • Each row can be refreshed simultaneously – One transistor/bit – Address lines are multiplexed: • Upper half of address: row access strobe (RAS) • Lower half of address: column access strobe (CAS) Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 41 Memory Technology

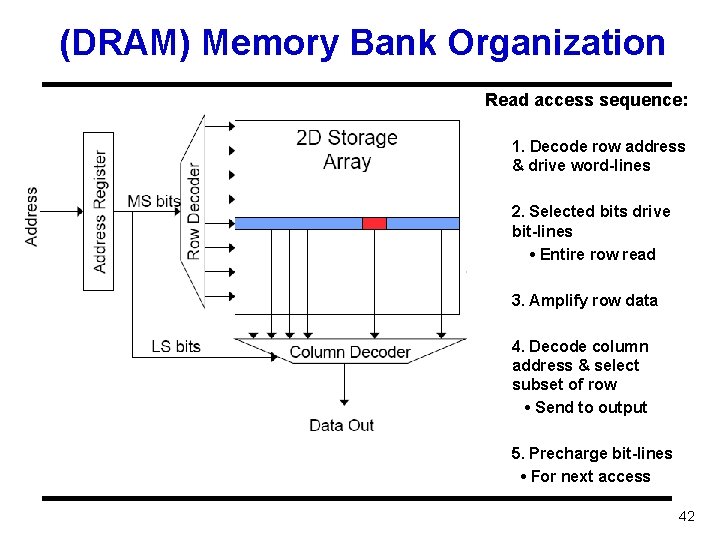

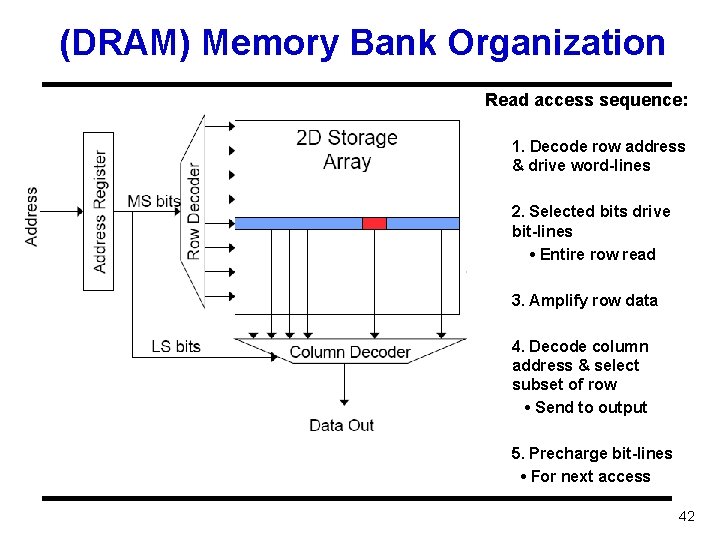

(DRAM) Memory Bank Organization Read access sequence: 1. Decode row address & drive word-lines 2. Selected bits drive bit-lines • Entire row read 3. Amplify row data 4. Decode column address & select subset of row • Send to output 5. Precharge bit-lines • For next access 42

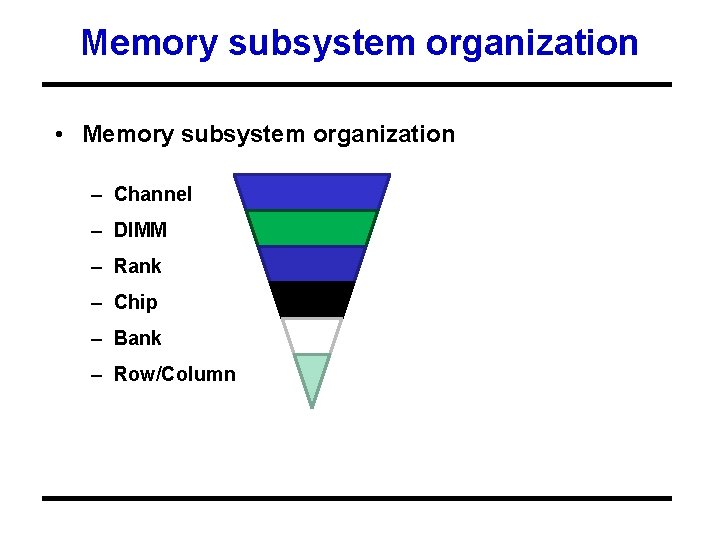

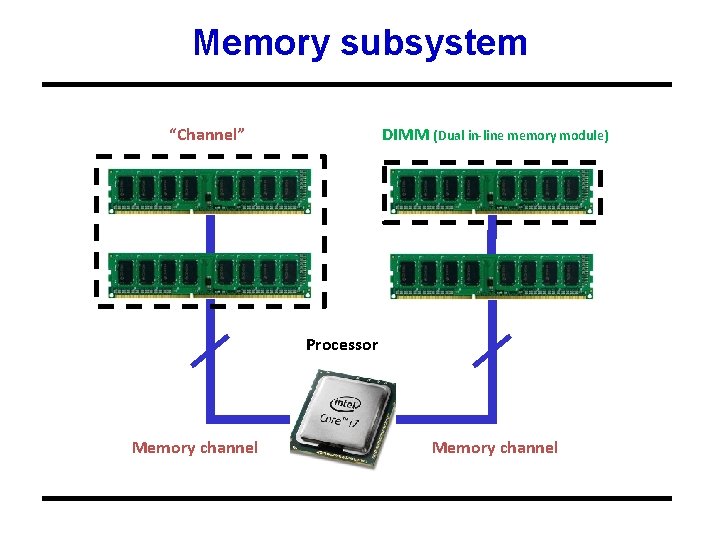

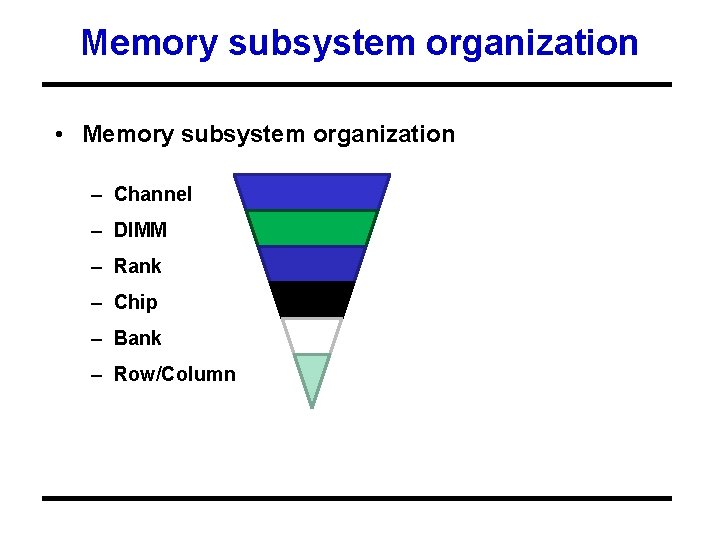

Memory subsystem organization • Memory subsystem organization – Channel – DIMM – Rank – Chip – Bank – Row/Column

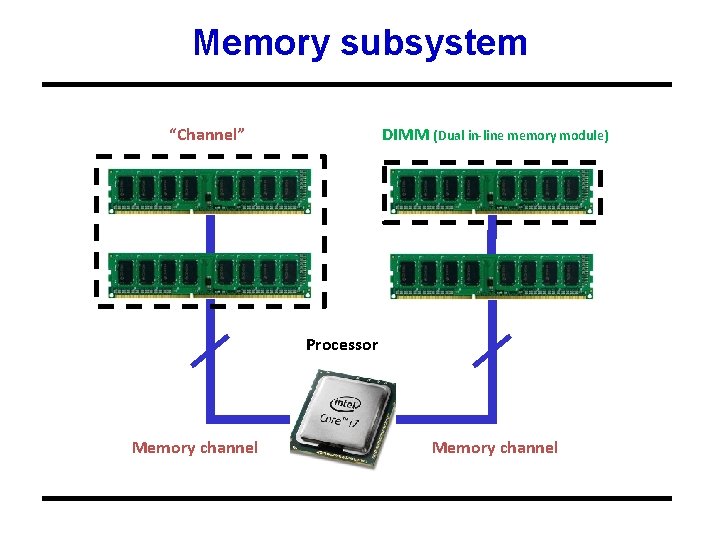

Memory subsystem “Channel” DIMM (Dual in-line memory module) Processor Memory channel

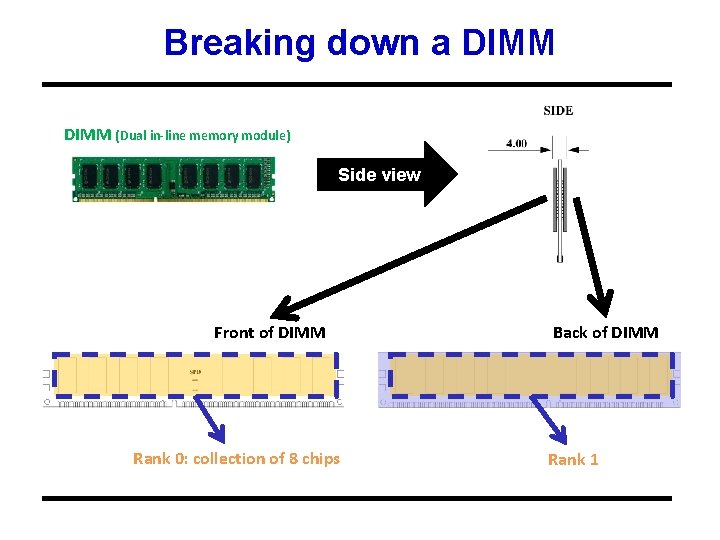

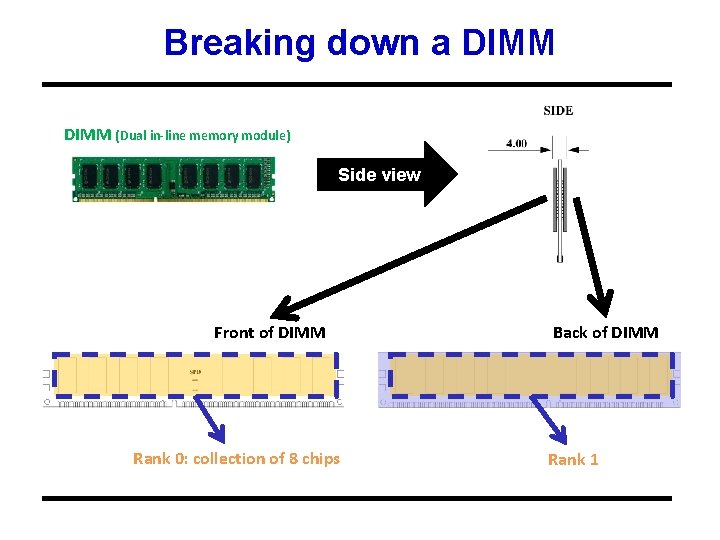

Breaking down a DIMM (Dual in-line memory module) Side view Front of DIMM Rank 0: collection of 8 chips Back of DIMM Rank 1

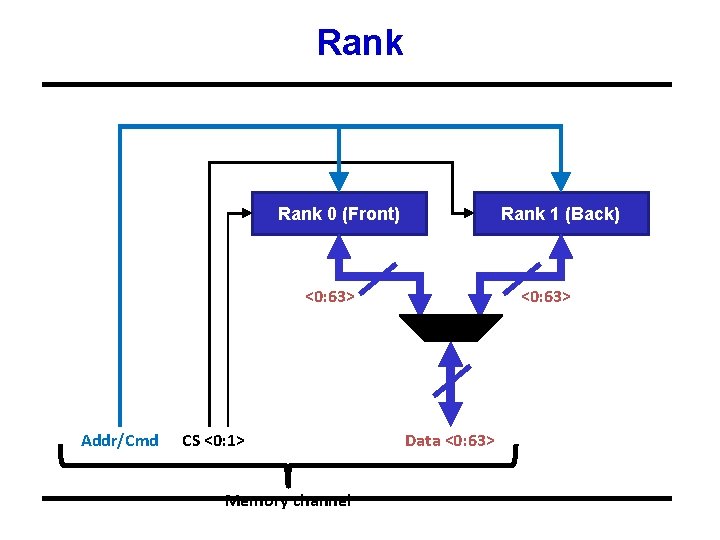

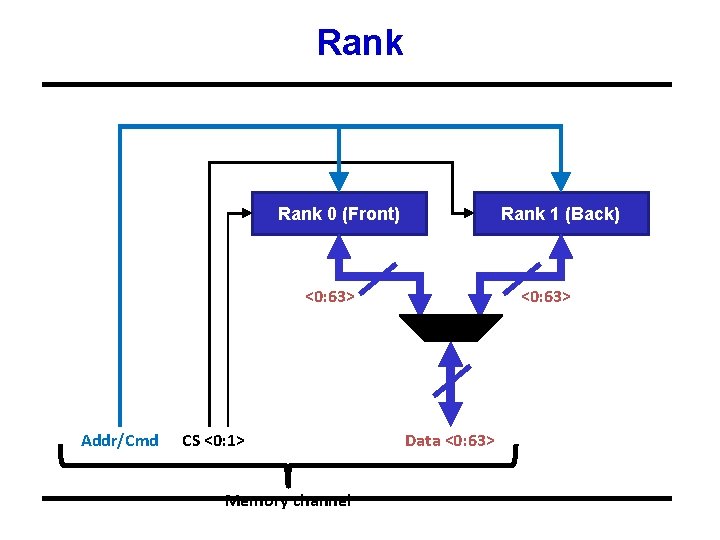

Rank 0 (Front) Rank 1 (Back) <0: 63> Addr/Cmd CS <0: 1> Memory channel <0: 63> Data <0: 63>

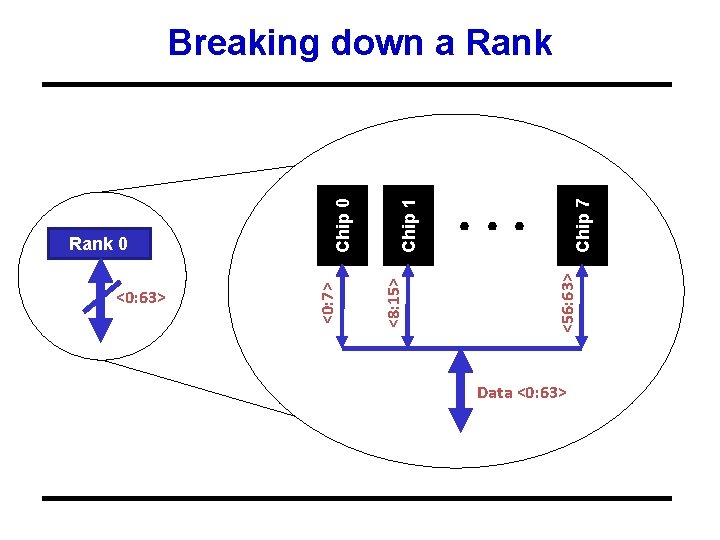

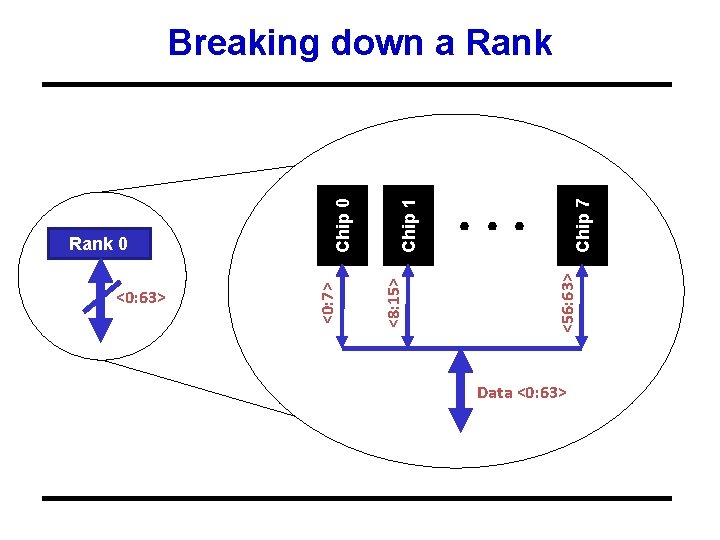

Chip 7 . . . <56: 63> Chip 1 <8: 15> <0: 63> <0: 7> Rank 0 Chip 0 Breaking down a Rank Data <0: 63>

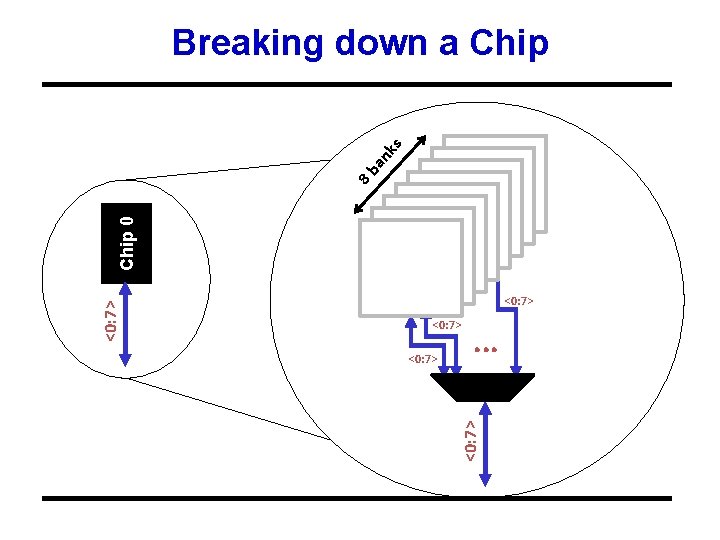

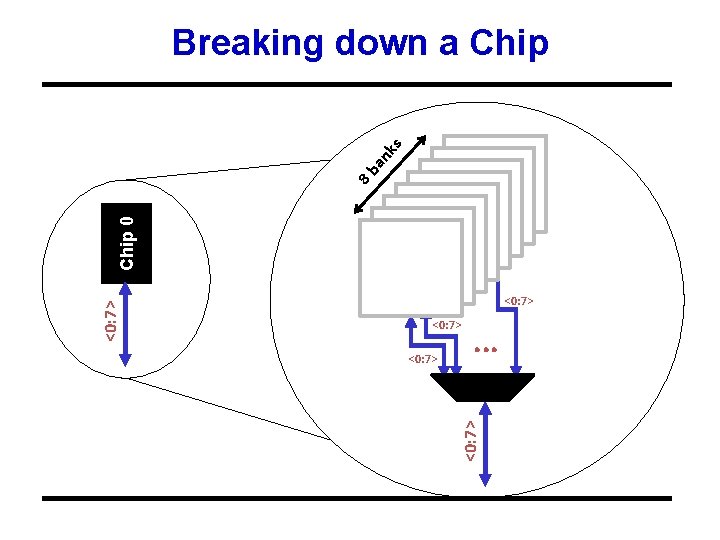

Bank 0 <0: 7> . . . <0: 7> Chip 0 8 b an ks Breaking down a Chip

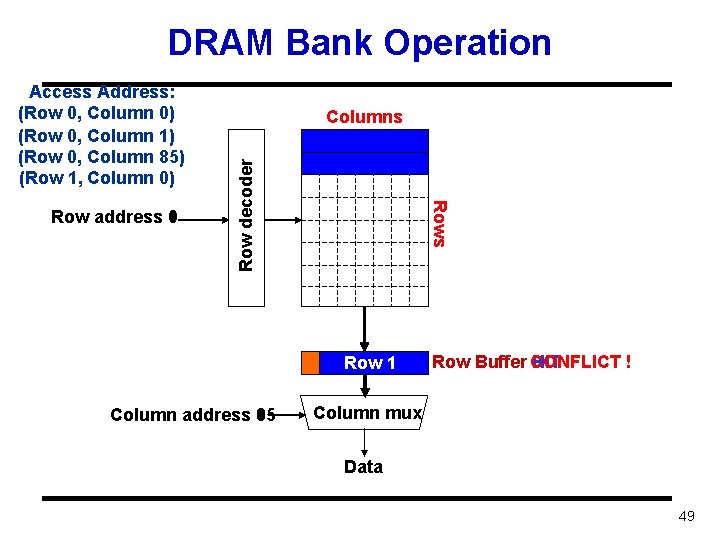

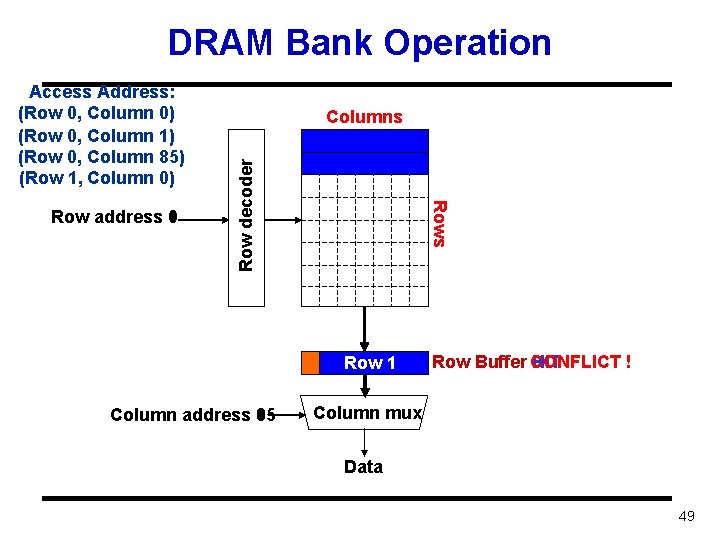

DRAM Bank Operation Rows Row address 0 1 Columns Row decoder Access Address: (Row 0, Column 0) (Row 0, Column 1) (Row 0, Column 85) (Row 1, Column 0) Row 01 Row Empty Column address 0 1 85 Row Buffer CONFLICT HIT ! Column mux Data 49

128 M x 8 -bit DRAM Chip 50

A 64 -bit Wide DIMM 51

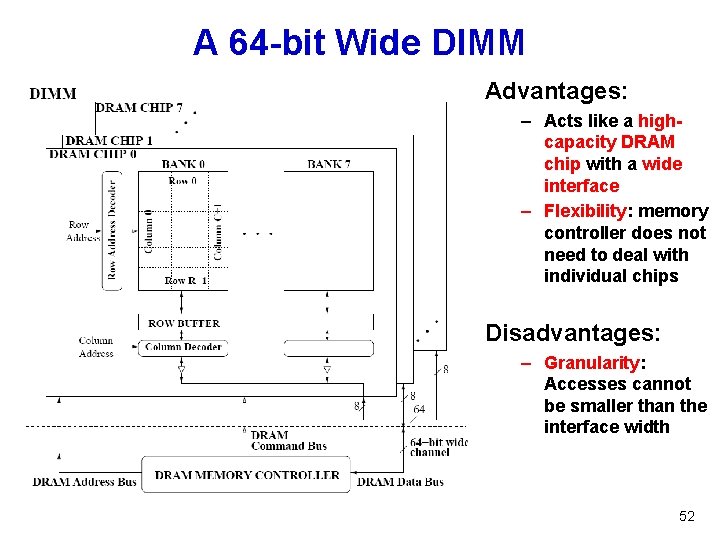

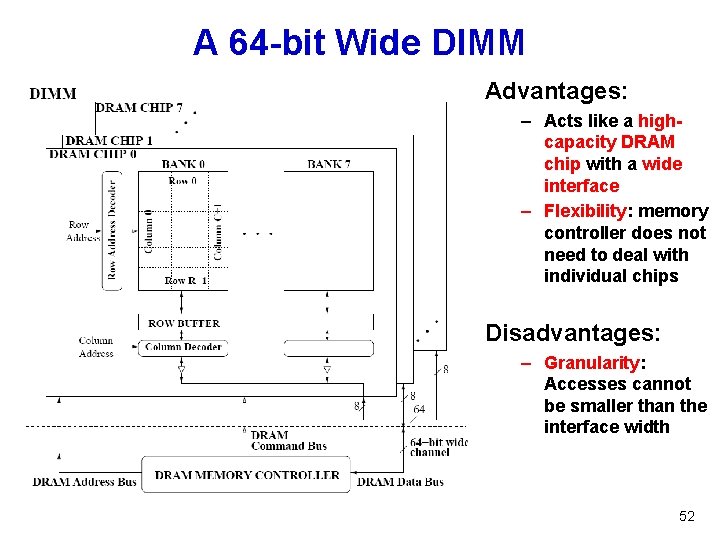

A 64 -bit Wide DIMM Advantages: – Acts like a highcapacity DRAM chip with a wide interface – Flexibility: memory controller does not need to deal with individual chips Disadvantages: – Granularity: Accesses cannot be smaller than the interface width 52

DRAM Channels 2 Independent Channels: 2 Memory Controllers (Above) 2 Dependent/Lockstep Channels: 1 Memory Controller with wide interface (Not Shown above) 53

Generalized Memory Structure 54

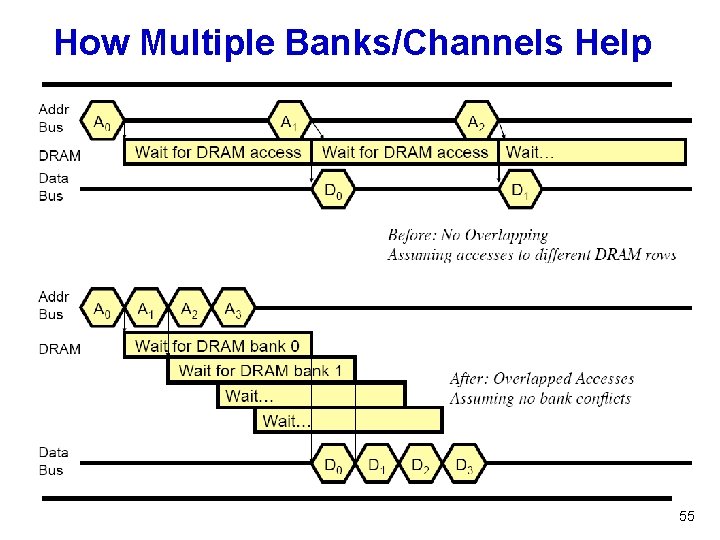

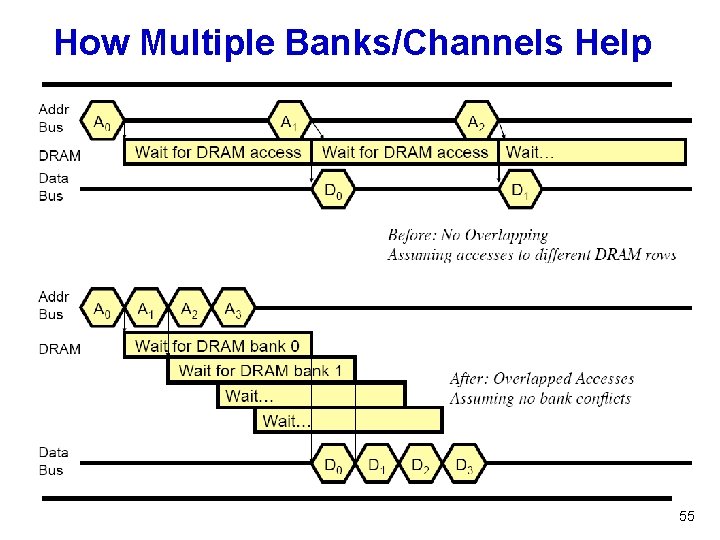

How Multiple Banks/Channels Help 55

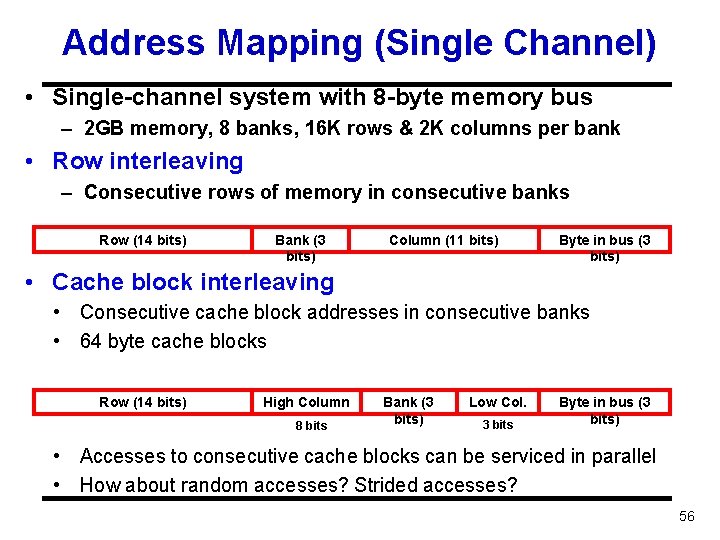

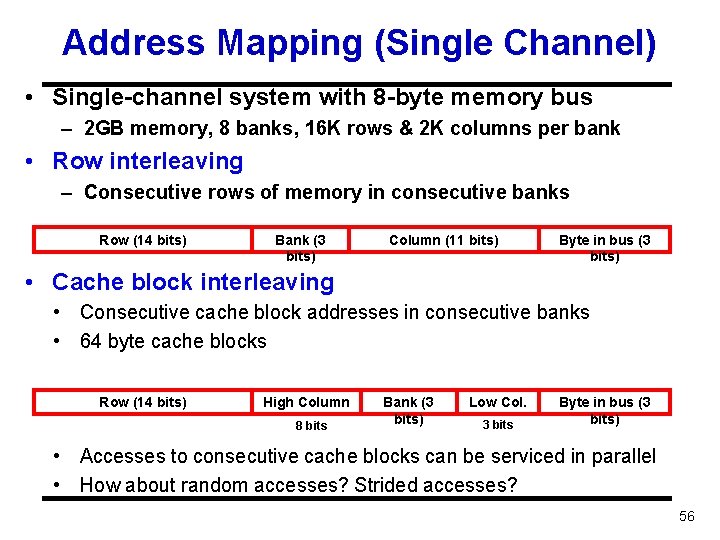

Address Mapping (Single Channel) • Single-channel system with 8 -byte memory bus – 2 GB memory, 8 banks, 16 K rows & 2 K columns per bank • Row interleaving – Consecutive rows of memory in consecutive banks Row (14 bits) Bank (3 bits) Column (11 bits) Byte in bus (3 bits) • Cache block interleaving • Consecutive cache block addresses in consecutive banks • 64 byte cache blocks Row (14 bits) High Column 8 bits Bank (3 bits) Low Col. 3 bits Byte in bus (3 bits) • Accesses to consecutive cache blocks can be serviced in parallel • How about random accesses? Strided accesses? 56

• Amdahl: – Memory capacity should grow linearly with processor speed – Unfortunately, memory capacity and speed has not kept pace with processors • Some optimizations: – Multiple accesses to same row – Synchronous DRAM • Added clock to DRAM interface • Burst mode with critical word first – Wider interfaces – Double data rate (DDR) – Multiple banks on each DRAM device Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 57 Memory Technology

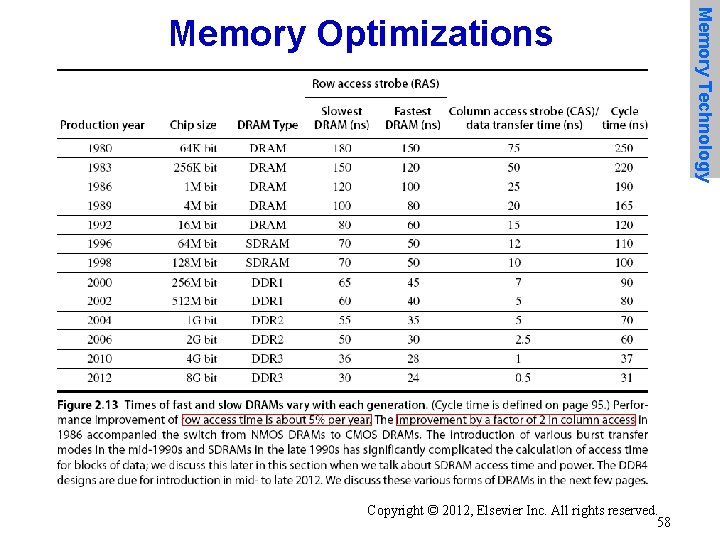

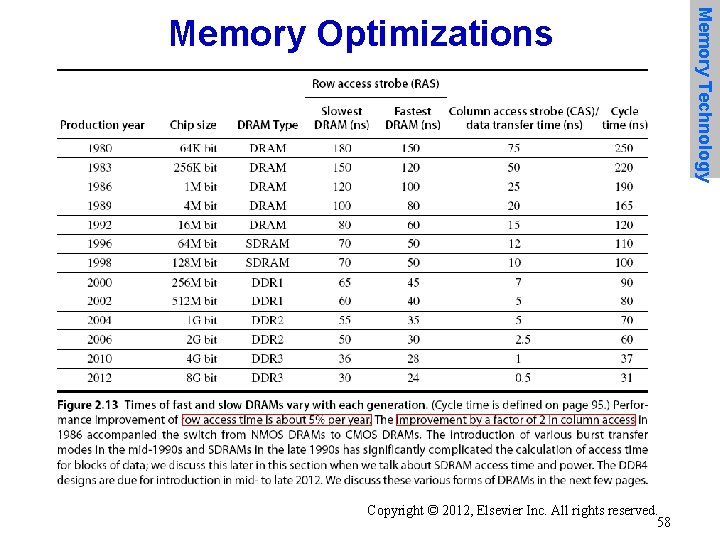

Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 58 Memory Technology Memory Optimizations

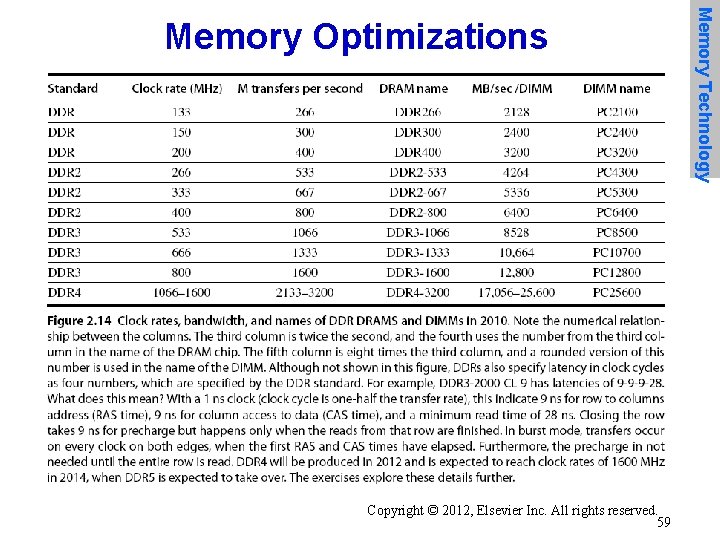

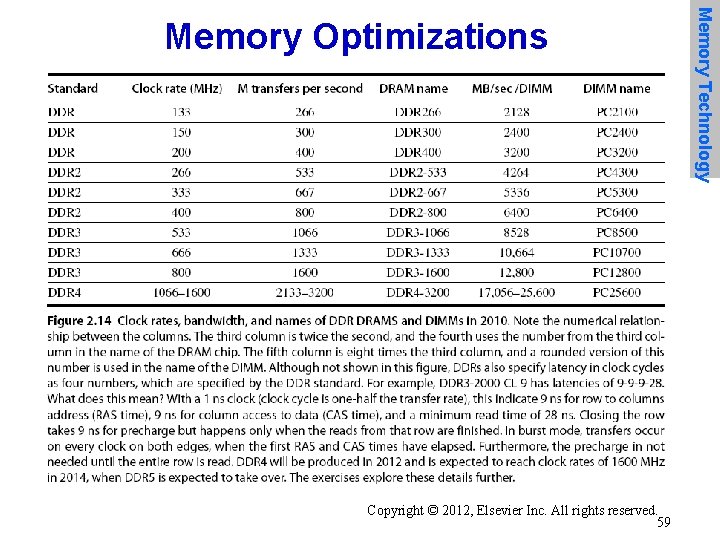

Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 59 Memory Technology Memory Optimizations

• DDR: – DDR 2 • Lower power (2. 5 V -> 1. 8 V) • Higher clock rates (266 MHz, 333 MHz, 400 MHz) – DDR 3 • 1. 5 V • 800 MHz – DDR 4 • 1 -1. 2 V • 1600 MHz • GDDR 5 is graphics memory based on DDR 3 Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 60 Memory Technology Memory Optimizations

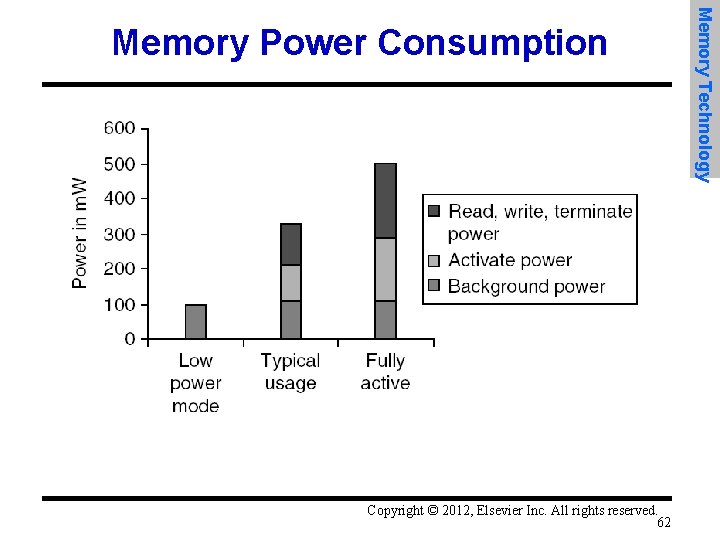

• Graphics memory: – Achieve 2 -5 X bandwidth per DRAM vs. DDR 3 • Wider interfaces (32 vs. 16 bit) • Higher clock rate – Possible because they are attached via soldering instead of socketted DIMM modules • Reducing power in SDRAMs: – Lower voltage – Low power mode (ignores clock, continues to refresh) Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 61 Memory Technology Memory Optimizations

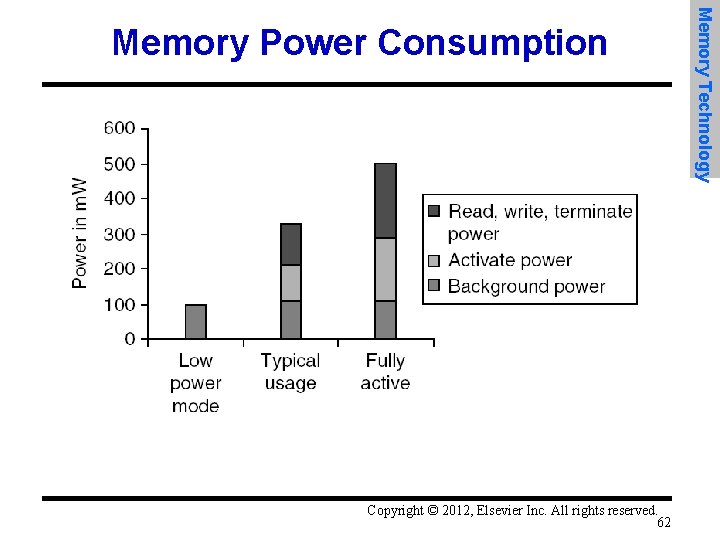

Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 62 Memory Technology Memory Power Consumption

• Type of EEPROM • Must be erased (in blocks) before being overwritten • Non volatile • Limited number of write cycles • Cheaper than SDRAM, more expensive than disk • Slower than SRAM, faster than disk Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 63 Memory Technology Flash Memory

• Memory is susceptible to cosmic rays • Soft errors: dynamic errors – Detected and fixed by error correcting codes (ECC) • Hard errors: permanent errors – Use sparse rows to replace defective rows • Chipkill: a RAID-like error recovery technique Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 64 Memory Technology Memory Dependability

• Protection via virtual memory – Keeps processes in their own memory space • Role of architecture: – Provide user mode and supervisor mode – Protect certain aspects of CPU state – Provide mechanisms for switching between user mode and supervisor mode – Provide mechanisms to limit memory accesses – Provide TLB to translate addresses Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 65 Virtual Memory and Virtual Machines Virtual Memory

• Supports isolation and security • Sharing a computer among many unrelated users • Enabled by raw speed of processors, making the overhead more acceptable • Allows different ISAs and operating systems to be presented to user programs – “System Virtual Machines” – SVM software is called “virtual machine monitor” or “hypervisor” – Individual virtual machines run under the monitor are called “guest VMs” Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 66 Virtual Memory and Virtual Machines