Chapter 17 Risk Management and the Foreign Currency

- Slides: 26

Chapter 17 Risk Management and the Foreign Currency Hedging Decision Slides prepared by April Knill, Ph. D. , Florida State University

17. 1 To Hedge or Not To Hedge • Hedging = risk mitigation • Forward contracts • Futures • Options • Risk management – should firms hedge? • Modigliani and Miller (1958; 1961) - indifferent • Usually involves derivative securities, used to take positions that offset the underlying sources of risk 17 -2 © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved.

17. 1 To Hedge or Not To Hedge • Hedging • Makes sense for entrepreneurs (assuming exposure to forex) because • Future forex rates are difficult, if not impossible, to predict • Firm is unable to diversify risks as most investors can so for the entrepreneur it is a good enough reason if he/she is risk-averse • Reducing the variance of profits increases the entrepreneur’s expected utility • More difficult for publicly held corporations • Hedging must increase the equity value of the firm (e. g. , one of the terms in ANPV) or it must decrease the market value of debt to be worthwhile 17 -3 © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved.

17. 1 To Hedge or Not To Hedge • The Hedging-is-Irrelevant Logic of Modigliani and Miller • Modigliani-Miller proposition • If hedging only changes non-systematic risk while leaving systematic risk and expected value of the cash flows unchanged, hedging will not affect firm’s value • Investors can hedge on their own and they can always undo the hedging the firm does (assuming they have the same opportunity set) • Problems with theory • Assumptions are not real world, e. g. , individuals don’t always have the same opportunities and even if they did, they aren’t going to pay the same amount for them 17 -4 © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved.

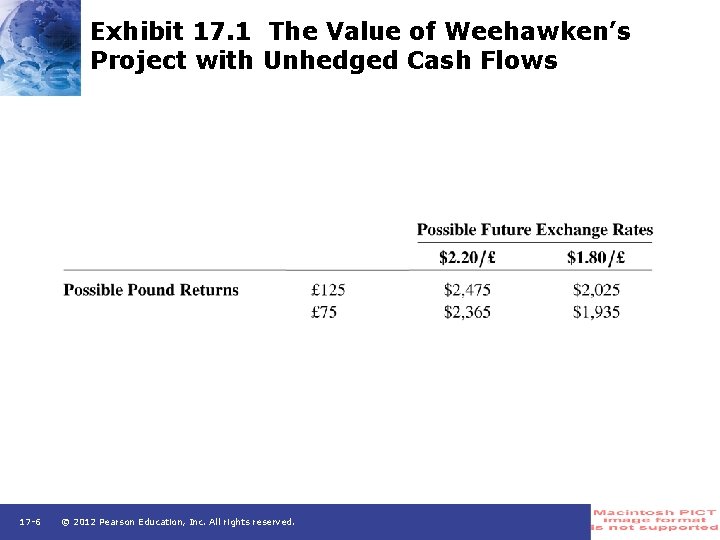

17. 2 Arguments Against Hedging • Hedging is costly • Bid-ask spread – larger in forward market • Salaries and monitoring costs of employees to evaluate hedging alternatives • Hedging equity risk is difficult, if not impossible • Weehawken Widget Project – either £ 125 or £ 75 for every year from next year into infinity • E[0. 5*£ 75 + 0. 5*£ 125] = £ 100 • Discounted @ 10%, that is £ 1, 000 @ $2/£ $2, 000 • With a cost of $1, 900, profit=$100 17 -5 © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved.

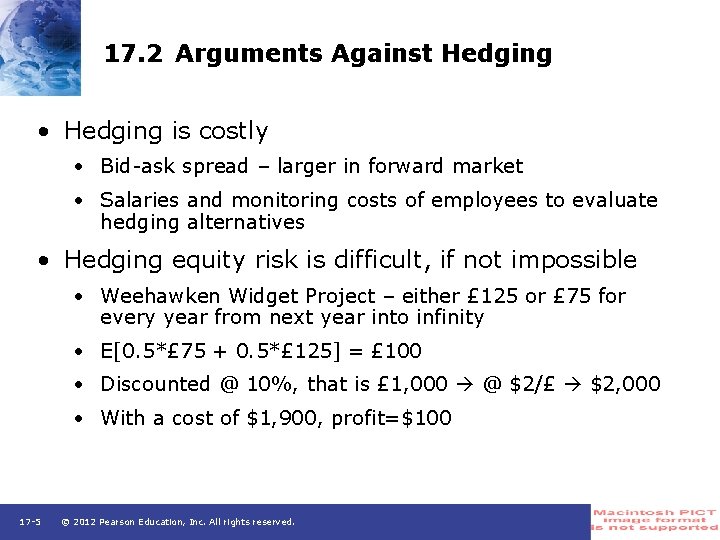

Exhibit 17. 1 The Value of Weehawken’s Project with Unhedged Cash Flows 17 -6 © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved.

17. 2 Arguments Against Hedging • Forex rate can go up or down by $0. 20/£ with equal probability – Expectation is $2. 00/£ and discount rate = 10% – For top-left figure: – [($2. 20/£)*£ 125] + [($2. 20/£)*£ 1, 000] = $2, 475 $ Value of time t+1 £ CFs 17 -7 $ Value of infinite stream of £ CFs (still has same PV) © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved.

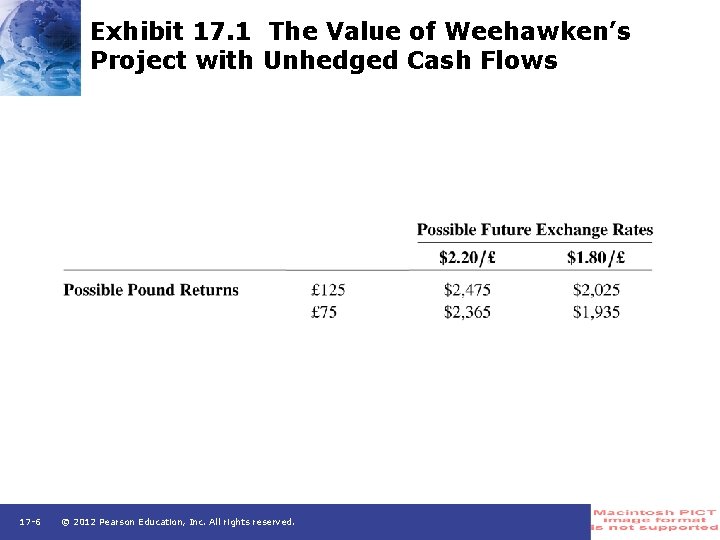

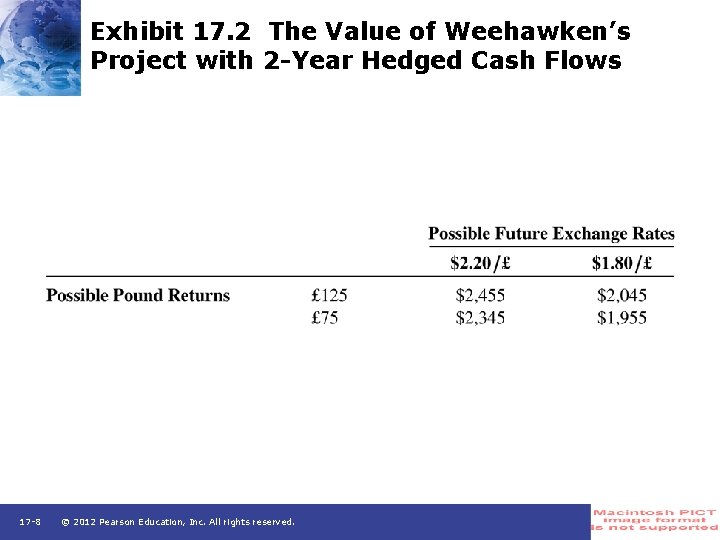

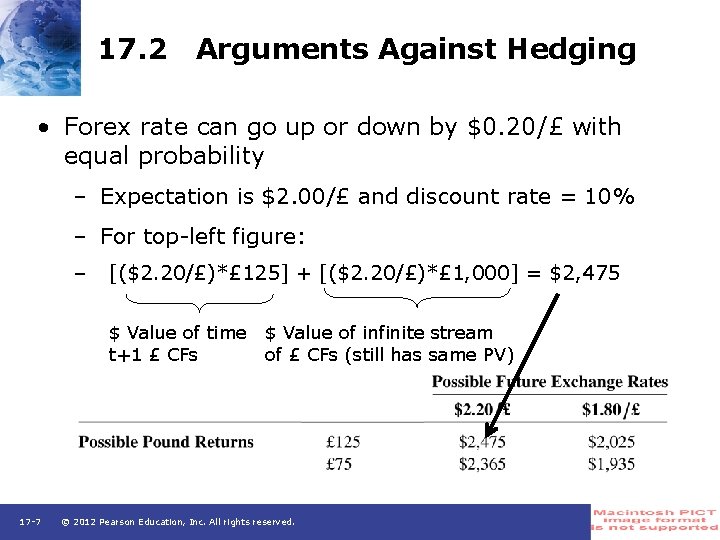

Exhibit 17. 2 The Value of Weehawken’s Project with 2 -Year Hedged Cash Flows 17 -8 © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved.

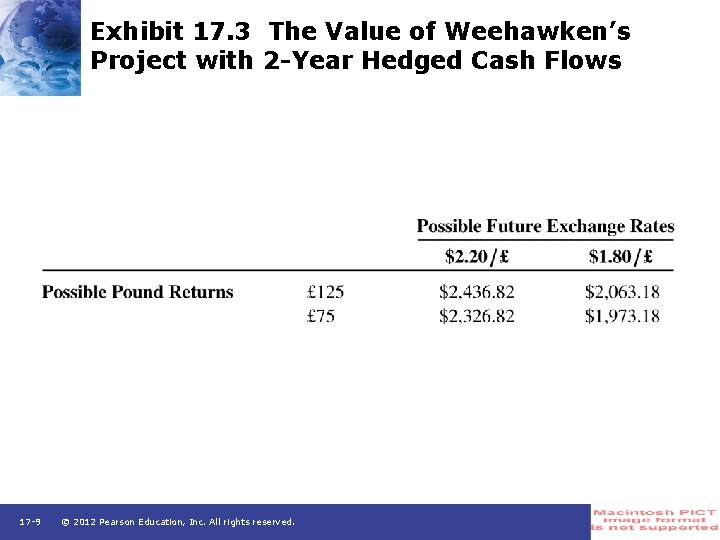

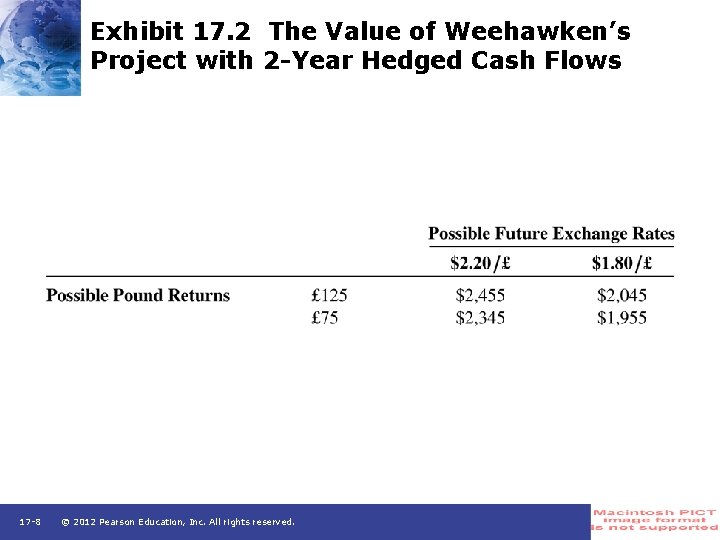

Exhibit 17. 3 The Value of Weehawken’s Project with 2 -Year Hedged Cash Flows 17 -9 © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved.

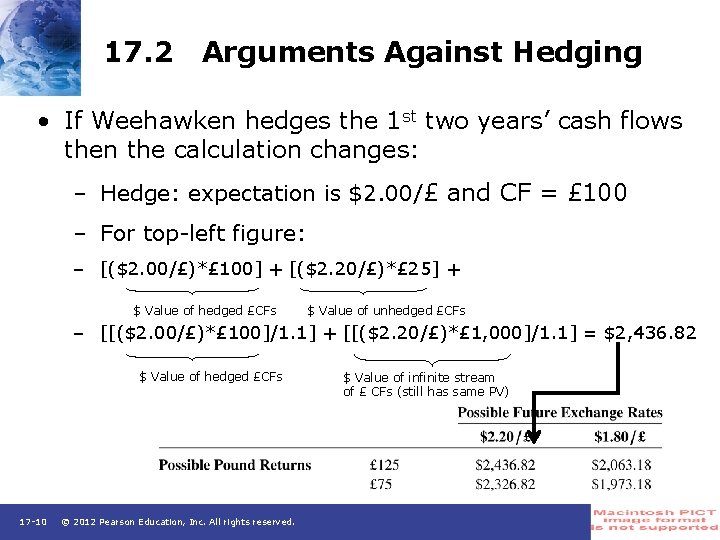

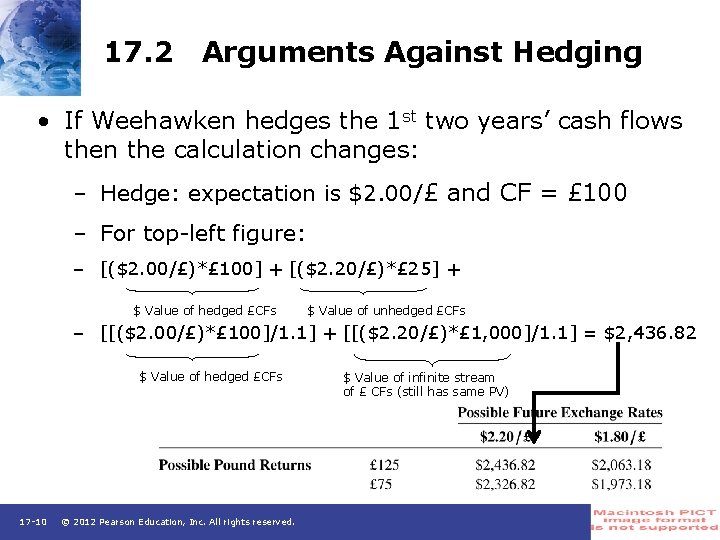

17. 2 Arguments Against Hedging • If Weehawken hedges the 1 st two years’ cash flows then the calculation changes: – Hedge: expectation is $2. 00/£ and CF = £ 100 – For top-left figure: – [($2. 00/£)*£ 100] + [($2. 20/£)*£ 25] + $ Value of hedged £CFs $ Value of unhedged £CFs – [[($2. 00/£)*£ 100]/1. 1] + [[($2. 20/£)*£ 1, 000]/1. 1] = $2, 436. 82 $ Value of hedged £CFs 17 -10 © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. $ Value of infinite stream of £ CFs (still has same PV)

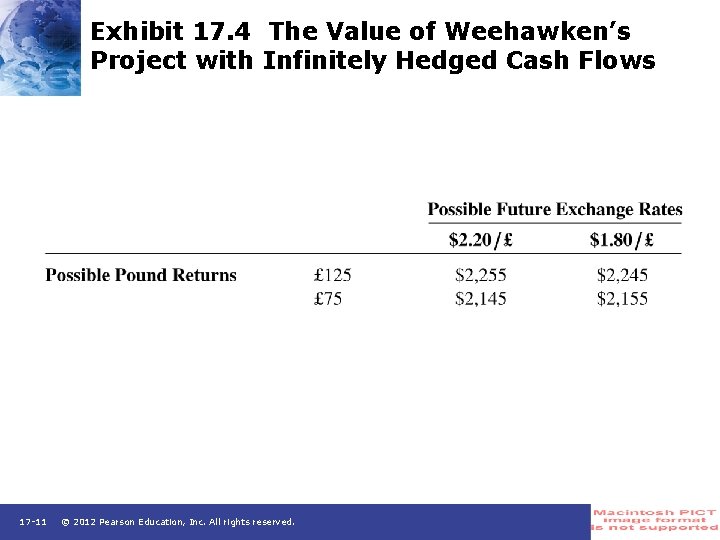

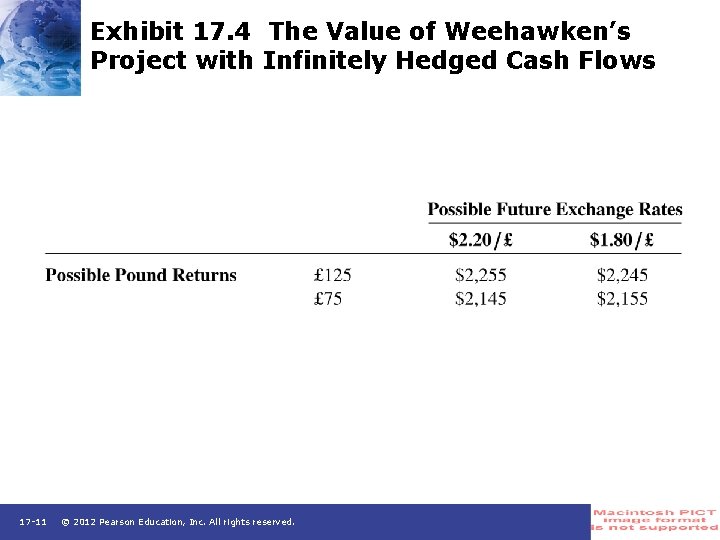

Exhibit 17. 4 The Value of Weehawken’s Project with Infinitely Hedged Cash Flows 17 -11 © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved.

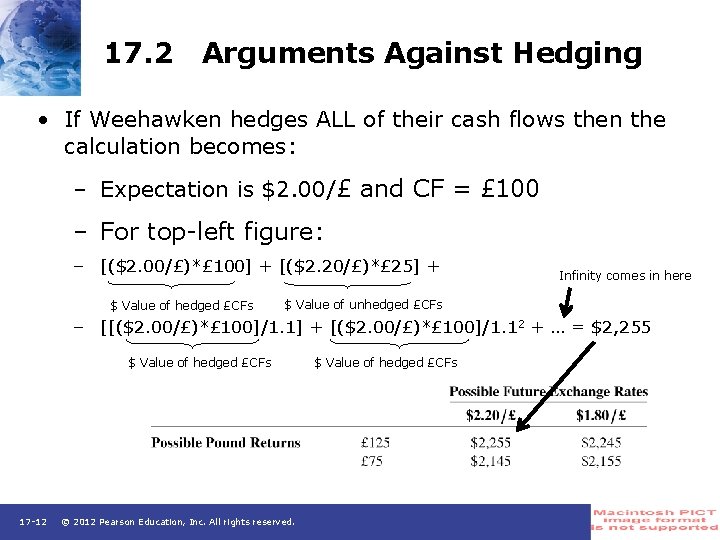

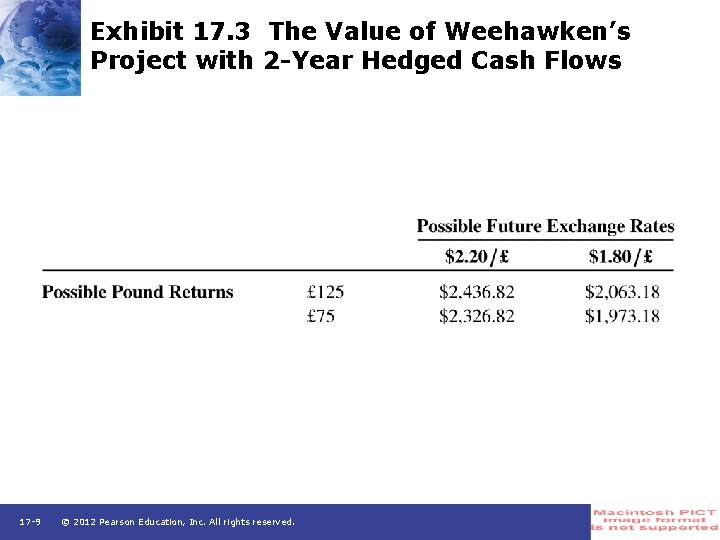

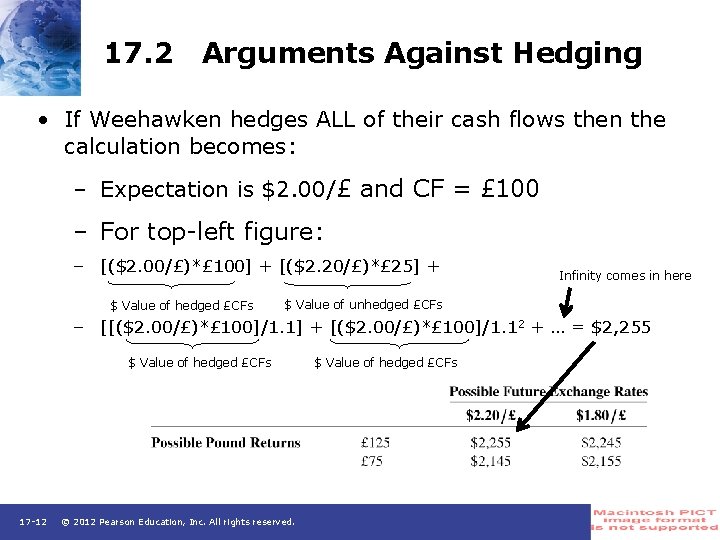

17. 2 Arguments Against Hedging • If Weehawken hedges ALL of their cash flows then the calculation becomes: – Expectation is $2. 00/£ and CF = £ 100 – For top-left figure: – [($2. 00/£)*£ 100] + [($2. 20/£)*£ 25] + $ Value of hedged £CFs Infinity comes in here $ Value of unhedged £CFs – [[($2. 00/£)*£ 100]/1. 1] + [($2. 00/£)*£ 100]/1. 12 + … = $2, 255 $ Value of hedged £CFs 17 -12 © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. $ Value of hedged £CFs

17. 2 Arguments Against Hedging • Hedging can create bad incentives • Firms near financial distress may be motivated for the higher return that accompanies an unhedged currency position • They may attempt to profit in currency speculation 17 -13 © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved.

17. 3 Arguments for Hedging • Hedging can reduce the firm’s expected taxes • Tax-loss carry forward: “refund” from government when you are unprofitable • However, NOT paid immediately and is carried forward - since $1 today is worth more than a $1 tomorrow we’d rather just avoid the loss • Limit to the amount of time you can carry it forward • Convex tax code: imposes a larger tax rate on higher income (and smaller on lower income) • Examples include progressive tax system (like ours in the U. S. ) and if tax losses are carried forward 17 -14 © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved.

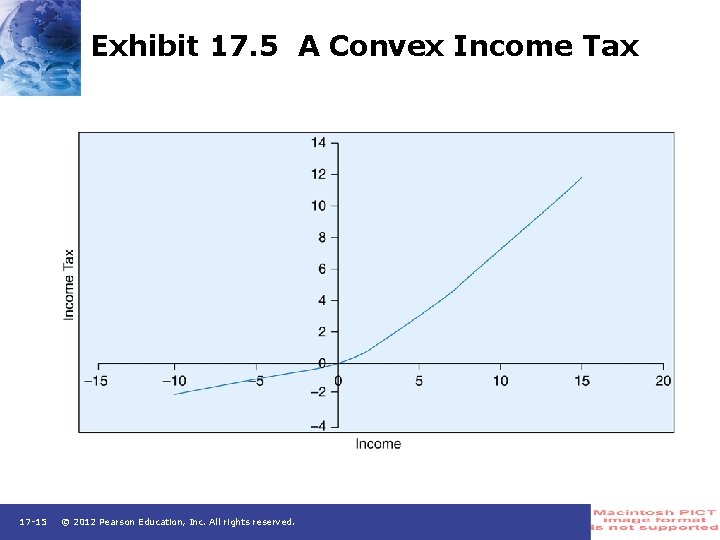

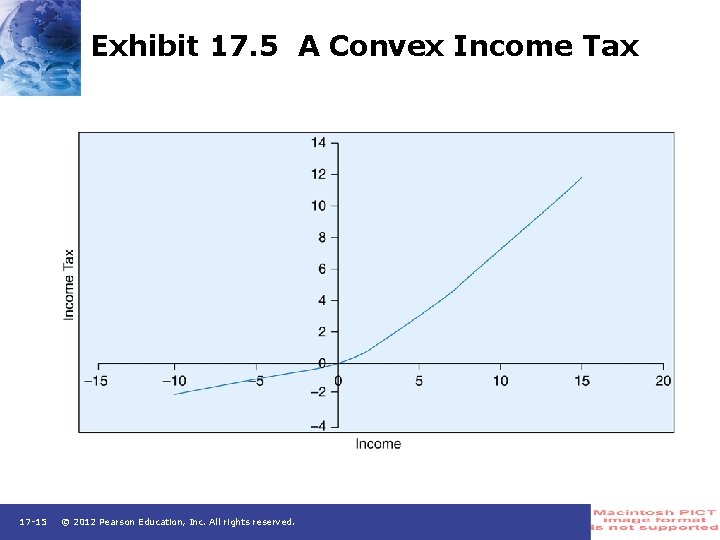

Exhibit 17. 5 A Convex Income Tax 17 -15 © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved.

17. 3 Arguments for Hedging – Convex tax code – General principles: Tax benefits are larger when • Tax code is more convex • Firm’s pretax income is more volatile • Firm’s income occurs in convex region of the tax code 17 -16 © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved.

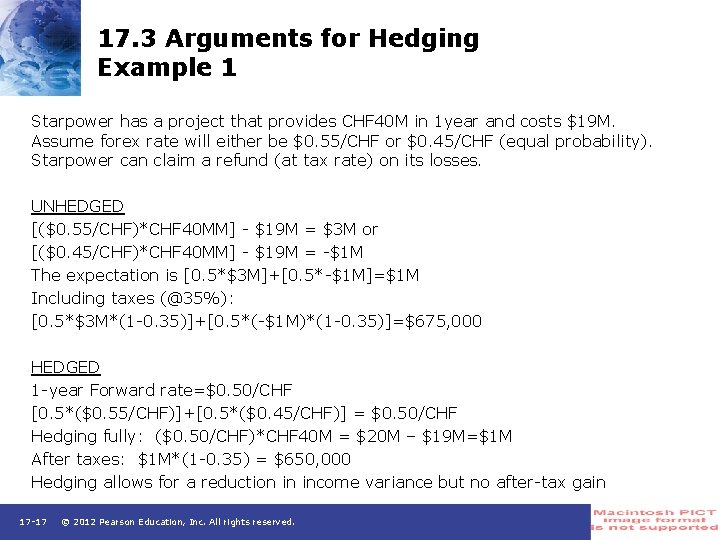

17. 3 Arguments for Hedging Example 1 Starpower has a project that provides CHF 40 M in 1 year and costs $19 M. Assume forex rate will either be $0. 55/CHF or $0. 45/CHF (equal probability). Starpower can claim a refund (at tax rate) on its losses. UNHEDGED [($0. 55/CHF)*CHF 40 MM] - $19 M = $3 M or [($0. 45/CHF)*CHF 40 MM] - $19 M = -$1 M The expectation is [0. 5*$3 M]+[0. 5*-$1 M]=$1 M Including taxes (@35%): [0. 5*$3 M*(1 -0. 35)]+[0. 5*(-$1 M)*(1 -0. 35)]=$675, 000 HEDGED 1 -year Forward rate=$0. 50/CHF [0. 5*($0. 55/CHF)]+[0. 5*($0. 45/CHF)] = $0. 50/CHF Hedging fully: ($0. 50/CHF)*CHF 40 M = $20 M – $19 M=$1 M After taxes: $1 M*(1 -0. 35) = $650, 000 Hedging allows for a reduction in income variance but no after-tax gain 17 -17 © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved.

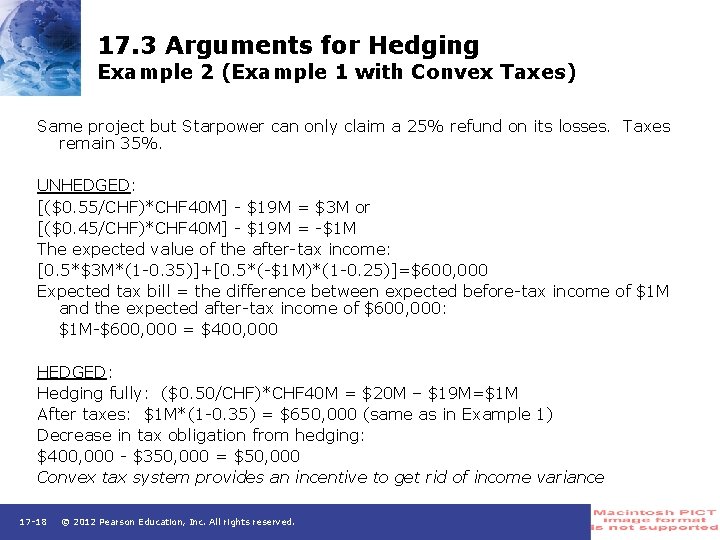

17. 3 Arguments for Hedging Example 2 (Example 1 with Convex Taxes) Same project but Starpower can only claim a 25% refund on its losses. Taxes remain 35%. UNHEDGED: [($0. 55/CHF)*CHF 40 M] - $19 M = $3 M or [($0. 45/CHF)*CHF 40 M] - $19 M = -$1 M The expected value of the after-tax income: [0. 5*$3 M*(1 -0. 35)]+[0. 5*(-$1 M)*(1 -0. 25)]=$600, 000 Expected tax bill = the difference between expected before-tax income of $1 M and the expected after-tax income of $600, 000: $1 M-$600, 000 = $400, 000 HEDGED: Hedging fully: ($0. 50/CHF)*CHF 40 M = $20 M – $19 M=$1 M After taxes: $1 M*(1 -0. 35) = $650, 000 (same as in Example 1) Decrease in tax obligation from hedging: $400, 000 - $350, 000 = $50, 000 Convex tax system provides an incentive to get rid of income variance 17 -18 © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved.

17. 3 Arguments for Hedging Example 3 (Ex. 2 with greater variance) What if the possible exchange rates change to $0. 60/CHF and $0. 40/CHF? UNHEDGED [($0. 60/CHF)*CHF 40 M] - $19 M = $5 M or [($0. 40/CHF)*CHF 40 M] - $19 M = -$3 M The expectation is [0. 5*$5 M]+[0. 5*-$3 M]=$1 M The expected value of the after-tax income: [0. 5*$5 M*(1 -0. 35)]+[0. 5*(-$3 M)*(1 -0. 25)]=$500, 000 Expected tax bill = $1 M-$500, 000 = $500, 000 HEDGED Hedging fully: ($0. 50/CHF)*CHF 40 M = $20 M – $19 M=$1 M After taxes: $1 M*(1 -0. 35) = $650, 000 (same as in Example 1) Increase in after-tax earnings from hedging: $150, 000 The more volatile the income, the greater the expected tax savings 17 -19 © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved.

17. 3 Arguments for Hedging • Hedging can lower the costs of financial distress • By reducing probability a firm will encounter distress, i. e. , the expected costs of financial distress (Smith and Stulz, 1985) • Hedging can improve the firm’s future investment decisions • If firm did not hedge and its value fell, (+) NPV projects may be missed • Froot, Scharfstein and Stein (1993) argue that hedging raises firm value in that it provides a definite stream of income to finance growth opportunities such as R&D activities 17 -20 © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved.

17. 3 Arguments for Hedging • Hedging can change the assessment of a firm’s managers • De. Marzo and Duffie (1995) find that manager quality is gauged by earnings information. Hedging increases the informational content of a firm’s profits about managers’ ability 17 -21 © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved.

17. 4 The Hedging Rationale of Real Firms • Leading pharmaceutical with $103. 7 Billion in sales (1988) in an industry that was not concentrated • Exposure • 70 subsidiaries around the world • 50% of revenue from foreign sources • Period of dollar strengthening • Price takers • One idea: to develop natural operating hedges • Using operations to provide a better balance between costs and revenues (in specific currencies) • Not possible because they wanted to keep most of the R&D in the U. S. 17 -22 © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved.

17. 4 The Hedging Rationale of Real Firms Merck’s 5 -Step Procedure 1. Develop forecasts to determine probability of adverse exchange rate movements 1. Consider economic fundamentals, government interference, past forex rates, professional forecasts 2. Assess the impact of exchange rate changes on firm’s 5 -year strategic plan 1. Sensitivity analysis 3. Decide whether to hedge currency exposure 1. Hedge on a case by case basis 4. Select appropriate hedging instrument 1. Options since they could then benefit from potential gains of a weakening dollar 5. Simulate alternative hedging programs to select most cost effective 1. Long-term options, avoid far-out-of-the-money options and partially self-insure 17 -23 © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved.

17. 5 Hedging Trends • Information from surveys • Nance, Smith and Smithson (1993) • Large R&D firms hedge • Highly levered firms hedge • Firms with higher dividend yields hedge • The Wharton/CIBC Survey • 83% of large firms hedge • 12% of smaller firms hedge • Hedging contains fixed costs smaller firms may not want to bear • Evidence that operational hedging is undertaken 17 -24 © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved.

17. 5 Hedging Trends • Geczy, Minton and Schrand (1997) • 41% use swaps, forwards, futures, options or combination of these • Firms with greater growth opportunities are more likely to use derivatives • Issuing debt in foreign currency serves same function as hedging instruments • Bartram, Brown and Fehle (2009) • Tax factors and high leverage are important • Large firms with high M/B ratios • Firms with larger foreign exchange exposure • Financial effects of hedging • Allayannis and Weston (2001) find that hedging increases the value of firms by 5% 17 -25 © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved.

17. 5 Hedging Trends • Deciding whether to hedge or not • What is industry norm and is there a good reason to divert from it? • Is your competition foreign or domestic? • Will changes in the real exchange rate inhibit your competitiveness? 17 -26 © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved.