Chapter 16 Acids and Bases The Arrhenius Model

Chapter 16 Acids and Bases

The Arrhenius Model An acid is any substance that produces hydrogen ions, H+, in an aqueous solution. Example: when hydrogen chloride gas is dissolved in water, the following ions are produced. HCl(g) H+(aq) + Cl-(aq) A base is an substance that produces hydroxide ions, OH-, in an solution. Example: When solid sodium hydroxide is dissolved in water the following ions are produced. Na. OH(s) Na+(aq) + OH-(aq) 16 -2 Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company

Another Theory: Brønsted-Lowry Model The Arrhenius model is limiting in its classification of acids and bases, suggesting there is only one kind of acid or base. A more general definition was suggested by a Danish chemist named Johannes Brønsted an English chemist named Thomas Lowry. The Brønsted-Lowry Model states: An acid is a proton (H+) donor A base is a proton (H+) acceptor. 16 -3 Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company

Brønsted-Lowry Model Let’s look at a general reaction for an acid (HA) in water. HA(aq) + H 2 O(l) H 3 O+(aq) + A-(aq) In the reaction which reactant was the proton donor (acid)? Which reactant was the proton acceptor (base)? If we look at the products, we see that now we have role reversal. Which product is a proton donor? Which product is a proton acceptor? In this case, the proton donor in the products side is known as the conjugate acid, and the proton acceptor is known as the conjugate base. 16 -4 Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company

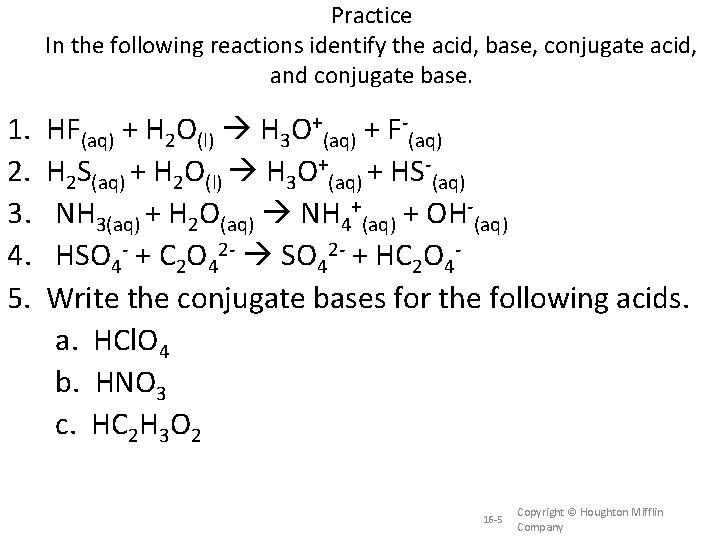

Practice In the following reactions identify the acid, base, conjugate acid, and conjugate base. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. HF(aq) + H 2 O(l) H 3 O+(aq) + F-(aq) H 2 S(aq) + H 2 O(l) H 3 O+(aq) + HS-(aq) NH 3(aq) + H 2 O(aq) NH 4+(aq) + OH-(aq) HSO 4 - + C 2 O 42 - SO 42 - + HC 2 O 4 Write the conjugate bases for the following acids. a. HCl. O 4 b. HNO 3 c. HC 2 H 3 O 2 16 -5 Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company

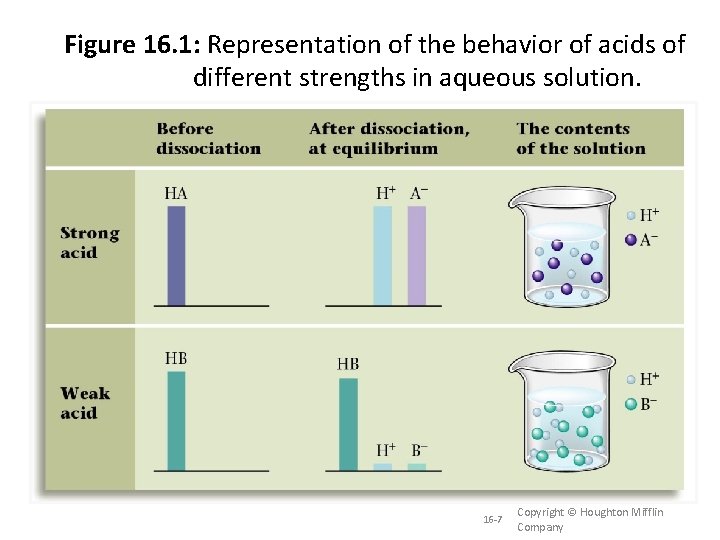

16. 2 Acid Strength When we put an acid or base in water, the compound breaks apart into it’s respective ions is called dissociation. The degree which a compound dissociates in water determines the strength of the acid or base. Strong acids and bases are substances that are completely ionized, ionized or completely dissociated in solution. Weak acids and bases are substances that only ionize or dissociate partially in solution. 16 -6 Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company

Figure 16. 1: Representation of the behavior of acids of different strengths in aqueous solution. 16 -7 Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company

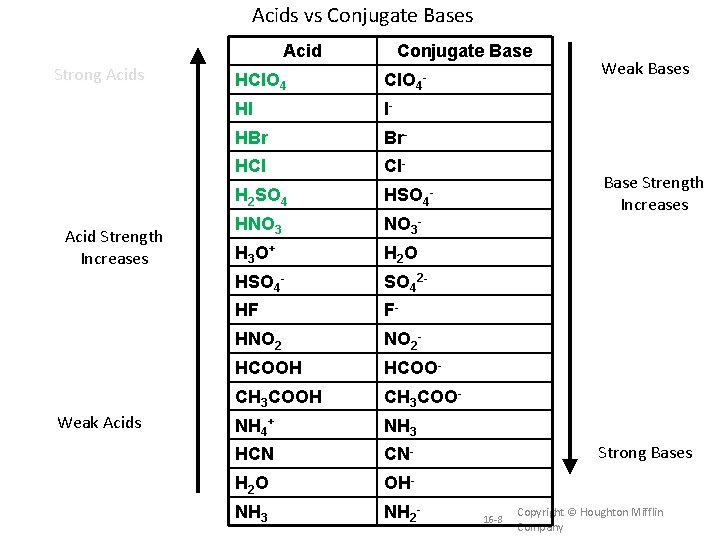

Acids vs Conjugate Bases Acid Strong Acids Acid Strength Increases Weak Acids Conjugate Base HCl. O 4 - HI I- HBr Br- HCl Cl- H 2 SO 4 HSO 4 - HNO 3 - H 3 O + H 2 O HSO 4 - SO 42 - HF F- HNO 2 - HCOOH HCOO- CH 3 COOH CH 3 COO- NH 4+ NH 3 HCN CN- H 2 O OH- NH 3 NH 2 - Weak Bases Base Strength Increases Strong Bases 16 -8 Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company

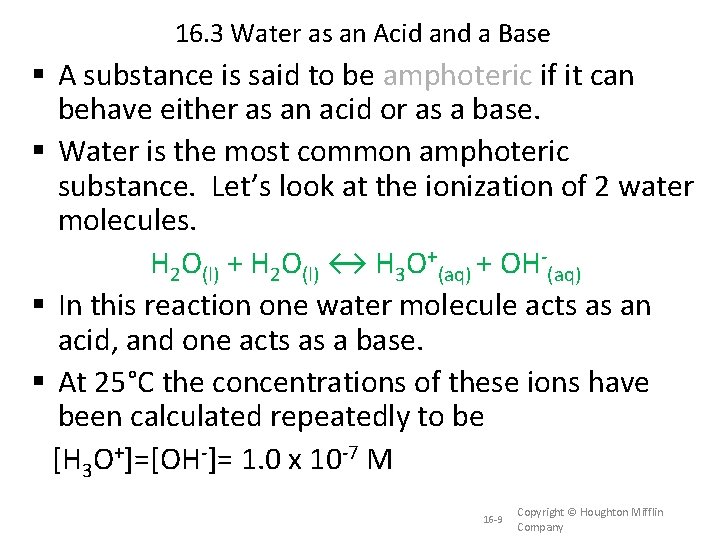

16. 3 Water as an Acid and a Base A substance is said to be amphoteric if it can behave either as an acid or as a base. Water is the most common amphoteric substance. Let’s look at the ionization of 2 water molecules. H 2 O(l) + H 2 O(l) ↔ H 3 O+(aq) + OH-(aq) In this reaction one water molecule acts as an acid, and one acts as a base. At 25°C the concentrations of these ions have been calculated repeatedly to be [H 3 O+]=[OH-]= 1. 0 x 10 -7 M 16 -9 Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company

![Ion-Product Constant, Kw • [H 3 O+][OH-] = 1. 0 x 10 -14 = Ion-Product Constant, Kw • [H 3 O+][OH-] = 1. 0 x 10 -14 =](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/d17feceb8ce6d74d566d34ec3aa05fbc/image-10.jpg)

Ion-Product Constant, Kw • [H 3 O+][OH-] = 1. 0 x 10 -14 = Kw • We call this constant, 1. 0 x 10 -14, Kw or the ion-product constant for water. • Kw = [H+][OH-] = 1. 0 x 10 -14 • In any aqueous solution at 25°C, no matter what it contains, the product of [H+] and [OH-] must always equal 1. 0 x 10 -14. • This means if the [H+] goes up, the [OH-] must go down so the product does not change. • [H+] = the concentration of H ions 16 -10 Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company

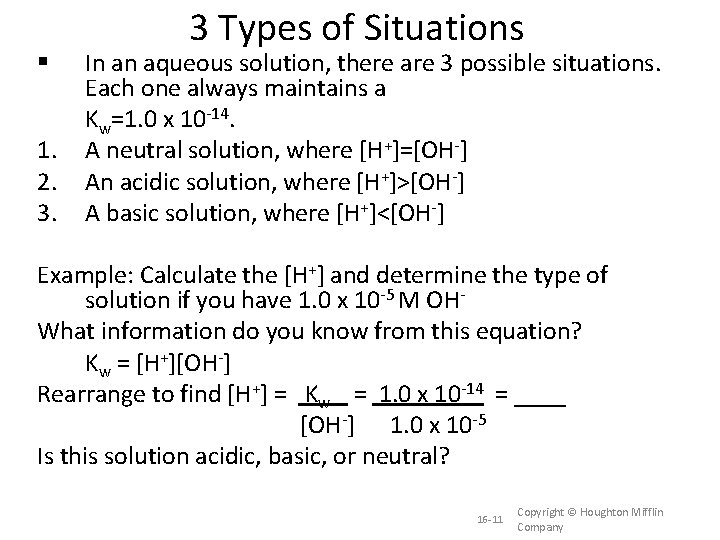

1. 2. 3. 3 Types of Situations In an aqueous solution, there are 3 possible situations. Each one always maintains a Kw=1. 0 x 10 -14. A neutral solution, where [H+]=[OH-] An acidic solution, where [H+]>[OH-] A basic solution, where [H+]<[OH-] Example: Calculate the [H+] and determine the type of solution if you have 1. 0 x 10 -5 M OHWhat information do you know from this equation? Kw = [H+][OH-] Rearrange to find [H+] = Kw = 1. 0 x 10 -14 = ____ [OH-] 1. 0 x 10 -5 Is this solution acidic, basic, or neutral? 16 -11 Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company

![Practice Problems Determine the [H+] and [OH-] and whether the solution is acidic, basic Practice Problems Determine the [H+] and [OH-] and whether the solution is acidic, basic](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/d17feceb8ce6d74d566d34ec3aa05fbc/image-12.jpg)

Practice Problems Determine the [H+] and [OH-] and whether the solution is acidic, basic or neutral. 1. 2. 3. 4. 10. 0 M H+ 1. 0 x 10 -7 M OH 3. 4 x 10 -4 M H+ 2. 6 x 10 -8 M H+ 16 -12 Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company

![16. 4 The p. H Scale Calculating the [H+] and [OH-] brings a lot 16. 4 The p. H Scale Calculating the [H+] and [OH-] brings a lot](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/d17feceb8ce6d74d566d34ec3aa05fbc/image-13.jpg)

16. 4 The p. H Scale Calculating the [H+] and [OH-] brings a lot of very small numbers which is rather inconvenient. In 1909 a French chemist, named Sorensen, came up with the p. H scale. p. H, literally means “power of hydrogen” When calculating the p. H we use the following: p. H = - log [H+] Calculate the p. H of a solution with [H+] = 1. 0 x 10 -7 M Acidic solution p. H < 7. 00 Basic solution p. H > 7. 00 Neutral solution p. H= 7. 00 16 -13 Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company

The p. H Scale • On the p. H scale, each increase of 1 unit equals a power of ten change in the [H+]. • A solution with a p. H of 3, has a [H+] = 1 x 10 -3 M, which is 10 greater than a solution with p. H of 4, or [H+] of 1 x 10 -4 M and 100 times greater than a p. H of 5 or 1 x 10 -5=[H+]. • As the [H+] increases, the p. H decreases. • The p. H scale runs values from 0 to 14, zero being very acidic, 14 being very basic, and 7 being neutral. 16 -14 Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company

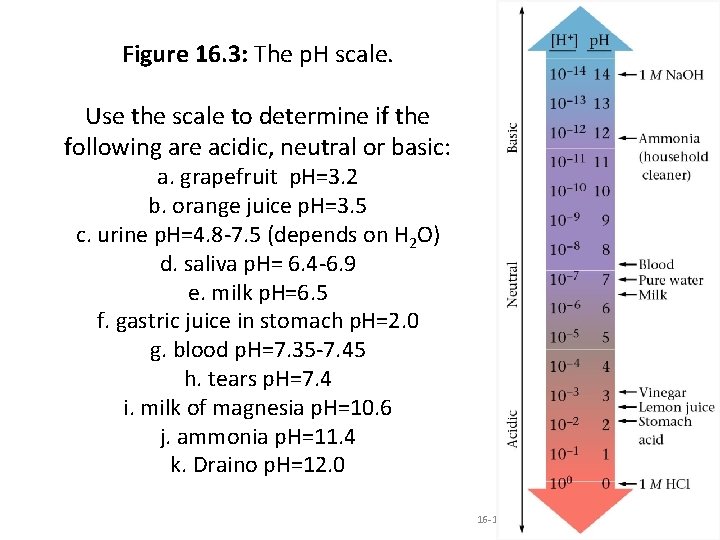

Figure 16. 3: The p. H scale. Use the scale to determine if the following are acidic, neutral or basic: a. grapefruit p. H=3. 2 b. orange juice p. H=3. 5 c. urine p. H=4. 8 -7. 5 (depends on H 2 O) d. saliva p. H= 6. 4 -6. 9 e. milk p. H=6. 5 f. gastric juice in stomach p. H=2. 0 g. blood p. H=7. 35 -7. 45 h. tears p. H=7. 4 i. milk of magnesia p. H=10. 6 j. ammonia p. H=11. 4 k. Draino p. H=12. 0 16 -15 Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company

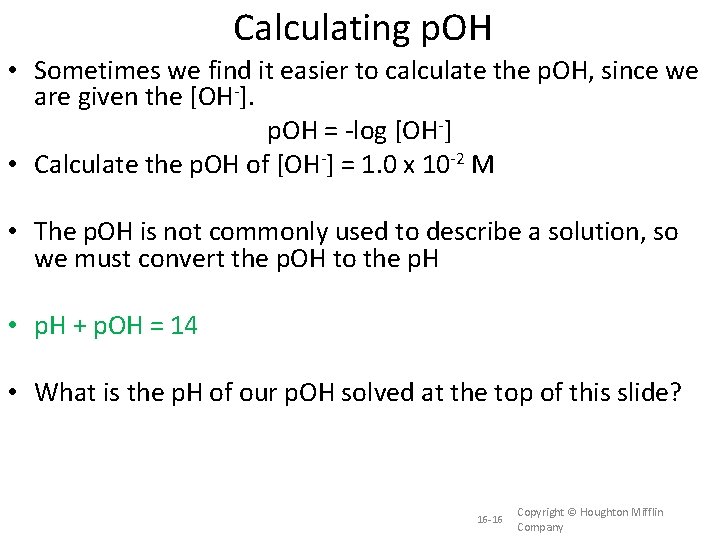

Calculating p. OH • Sometimes we find it easier to calculate the p. OH, since we are given the [OH-]. p. OH = -log [OH-] • Calculate the p. OH of [OH-] = 1. 0 x 10 -2 M • The p. OH is not commonly used to describe a solution, so we must convert the p. OH to the p. H • p. H + p. OH = 14 • What is the p. H of our p. OH solved at the top of this slide? 16 -16 Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company

Calculating p. H and p. OH Practice 1. 2. 3. 4. Calculate the p. H and p. OH for the following: [H+] = 1. 0 x 10 -4 M [OH-] = 1. 0 x 10 -3 M [H+] = 5. 60 x 10 -12 M Determine whether each of the solutions above is acidic, basic or neutral. NOTE: When determining sig figs for logs, the number of decimal places for a log must equal the number of significant figures in the original number. 16 -17 Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company

![Calculating the [H+] from the p. H • Sometimes the p. H is available, Calculating the [H+] from the p. H • Sometimes the p. H is available,](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/d17feceb8ce6d74d566d34ec3aa05fbc/image-18.jpg)

Calculating the [H+] from the p. H • Sometimes the p. H is available, but we need to know the [H+] of the solution. In this case we need to find the inverse log of the –p. H. [H+] = inverse log (-p. H) • On your calculator you may enter the –p. H, then push the inverse key and then the log. • Your calculator may also have a 10 x key, typically above the log key. With this key you would enter your –p. H, then push the 10 x key. • Calculate the [H+] if the p. H is 5. 00. • The same sequence is used for [OH-] and p. OH. 16 -18 Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company

Practice Problems • The p. H of a human blood sample was measured to be 7. 41. What is the [H+] in this blood? • The p. OH of a liquid drain cleaner was found to be 10. 50. What is the [OH-] for this cleaner? 16 -19 Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company

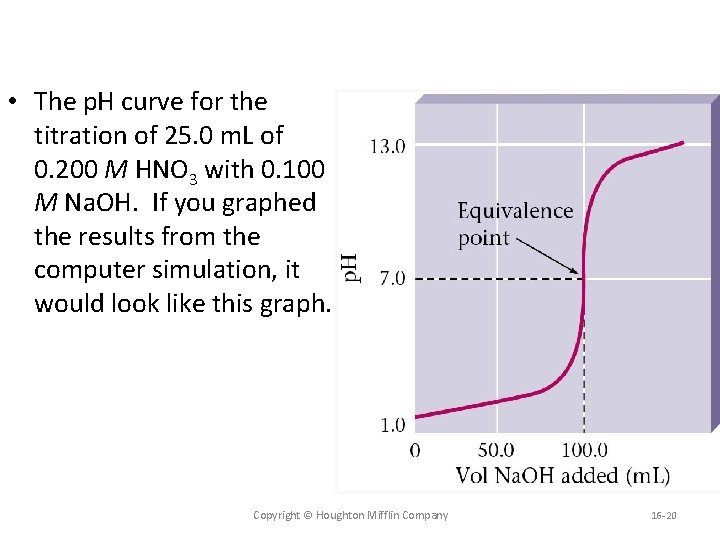

• The p. H curve for the titration of 25. 0 m. L of 0. 200 M HNO 3 with 0. 100 M Na. OH. If you graphed the results from the computer simulation, it would look like this graph. Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company 16 -20

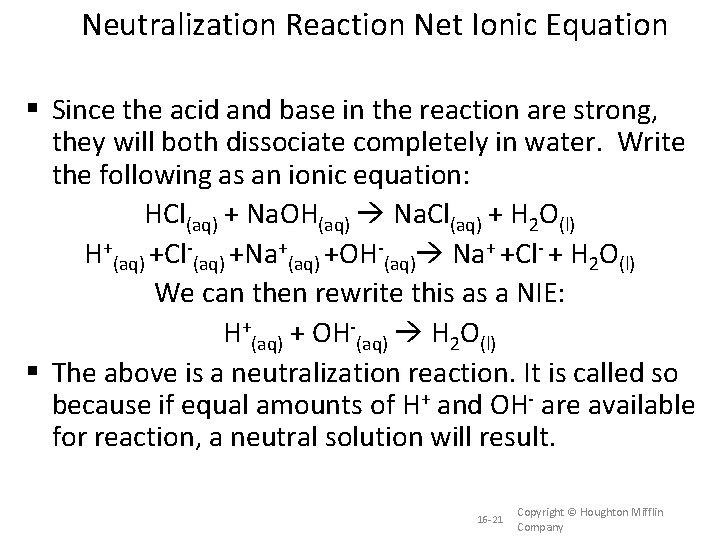

Neutralization Reaction Net Ionic Equation Since the acid and base in the reaction are strong, they will both dissociate completely in water. Write the following as an ionic equation: HCl(aq) + Na. OH(aq) Na. Cl(aq) + H 2 O(l) H+(aq) +Cl-(aq) +Na+(aq) +OH-(aq) Na+ +Cl- + H 2 O(l) We can then rewrite this as a NIE: H+(aq) + OH-(aq) H 2 O(l) The above is a neutralization reaction. It is called so because if equal amounts of H+ and OH- are available for reaction, a neutral solution will result. 16 -21 Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company

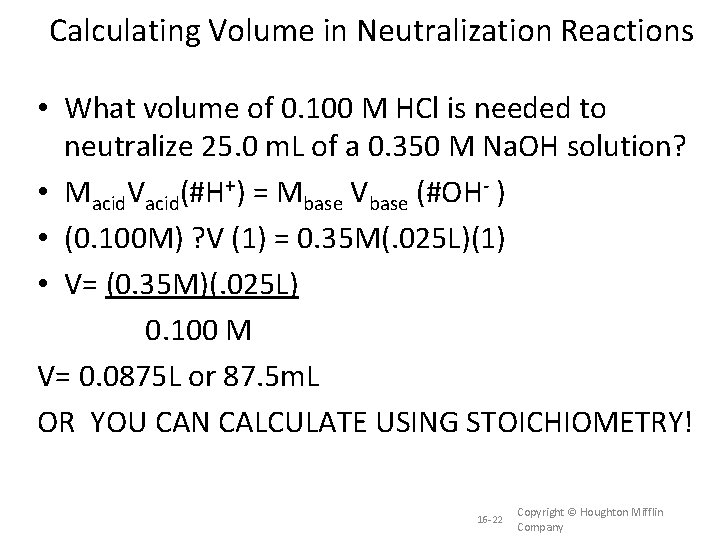

Calculating Volume in Neutralization Reactions • What volume of 0. 100 M HCl is needed to neutralize 25. 0 m. L of a 0. 350 M Na. OH solution? • Macid. Vacid(#H+) = Mbase Vbase (#OH- ) • (0. 100 M) ? V (1) = 0. 35 M(. 025 L)(1) • V= (0. 35 M)(. 025 L) 0. 100 M V= 0. 0875 L or 87. 5 m. L OR YOU CAN CALCULATE USING STOICHIOMETRY! 16 -22 Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company

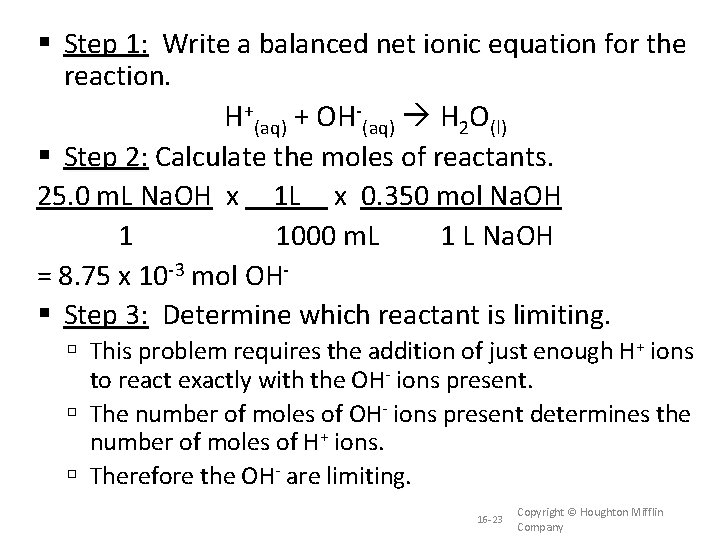

Step 1: Write a balanced net ionic equation for the reaction. H+(aq) + OH-(aq) H 2 O(l) Step 2: Calculate the moles of reactants. 25. 0 m. L Na. OH x 1 L x 0. 350 mol Na. OH 1 1000 m. L 1 L Na. OH = 8. 75 x 10 -3 mol OH Step 3: Determine which reactant is limiting. This problem requires the addition of just enough H+ ions to react exactly with the OH- ions present. The number of moles of OH- ions present determines the number of moles of H+ ions. Therefore the OH- are limiting. 16 -23 Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company

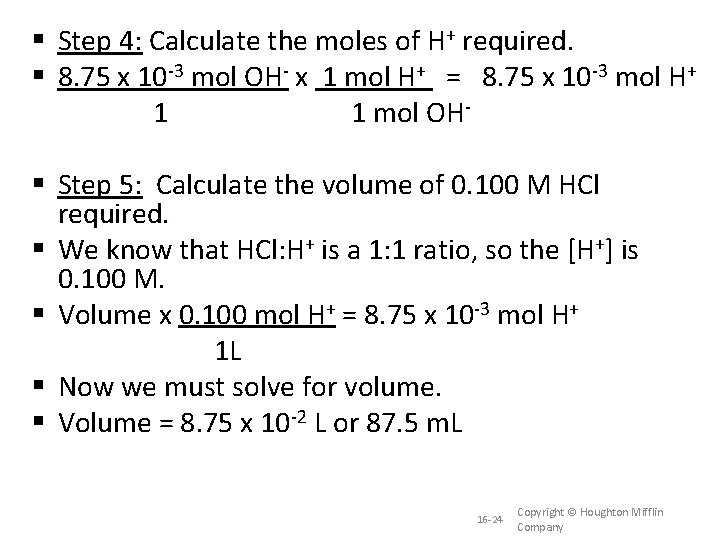

Step 4: Calculate the moles of H+ required. 8. 75 x 10 -3 mol OH- x 1 mol H+ = 8. 75 x 10 -3 mol H+ 1 1 mol OH Step 5: Calculate the volume of 0. 100 M HCl required. We know that HCl: H+ is a 1: 1 ratio, so the [H+] is 0. 100 M. Volume x 0. 100 mol H+ = 8. 75 x 10 -3 mol H+ 1 L Now we must solve for volume. Volume = 8. 75 x 10 -2 L or 87. 5 m. L 16 -24 Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company

Practice Problem 1. Calculate the volume of 0. 10 M HNO 3 needed to neutralize 125 m. L of 0. 050 M KOH. 16 -25 Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company

- Slides: 25