Chapter 15 Bargaining n Negotiation may involve q

Chapter 15 Bargaining n Negotiation may involve: q Exchange of information q Relaxation of initial goals q Mutual concession 1

What is your negotiation style? 2

Example n n Aspirations in Computing Who pays for lunch? 3

Why the difference? CS Associate Professors (2016): n Average Salary: $96. 5 K Finance Associate Professors (2016) n Average Salary: $145 K 5

6

Negotiation Protocol n n n n n Who begins Take turns single or multiple issues Build off previous offers Give feed back (or not). Tell what utility is (or not) Obligations – requirements for later Privacy (not share details of offers with others) Allowed proposals you can make as a result of negotiation history process terminates (hopefully) 7

THE $2 BARGAINING SIMULATION n n This simulation is about win/lose bargaining. You and another person must divide $2 between you today; what you get, the other person loses. There may not be any side deals, or "paybacks tomorrow, " or circumventions of any other kind; this is straight, distributive (win/lose) bargaining. Please follow the instructions, just for today, even if they are distasteful to you. Many people like this kind of bargaining. Other people hate it. If you hate it, play it out anyway and please tell me in the discussion how you feel about it. Remember, please, no circumventions; please try very hard to follow your Secret Instructions in each iteration of this simulation. You will have specific, personal instructions with each new partner; they will be different each time. You may not tell anyone else about these instructions until the bargaining is over. Again, please follow the instructions as precisely as possible. You will have a few minutes to consider strategy and tactics; please make notes as to your plans and ideas about how you will bargain. It is possible you will not be able to reach an agreement. 8

THE $2 BARGAINING SIMULATION Here are your questions: n n n What do you want here? What is your most optimistic hope? Your realistic expectation? What will you settle for? What does the other person probably want? How will you find out? How will you persuade the other person? What will your moves be? It is not possible to ask questions for more instructions; just do as well as you can. 9

Reflection n n What did you learn about yourselves? How did you actually negotiate compared with how you saw yourself before we started? 10

Learning Outcome n “splitting the difference” is not the only way to divide what is on the table, and why it may or may not be the best way, in real life. n The importance of intangibles (such as relationship, trust, friendly feelings) as well as tangibles (in this case money) as sources of value in a negotiation. n importance of repeated interactions with the same person—in building or losing a good relationship. (We do not usually bargain just once with the same person. We often interact with the same person more than once. This means that even a simple game of dividing two dollars, in what is supposed to be a win-lose game, is not in fact purely competitive. Because of the effect of successive interactions, positive and negative feelings become part of the intangibles that are won or lost in the interaction. ) 11

Learning Outcome (cont) n n The fact that one’s strategy is not the same as one’s style and demeanor. (One can be very competitive and very charming, or collaborative and aggressive, or competitive and aggressive, etc. ) The importance of ethics in negotiations --- how comfortable am I with making up a story, and how do I feel about a negotiations partner who lies or threatens? 12

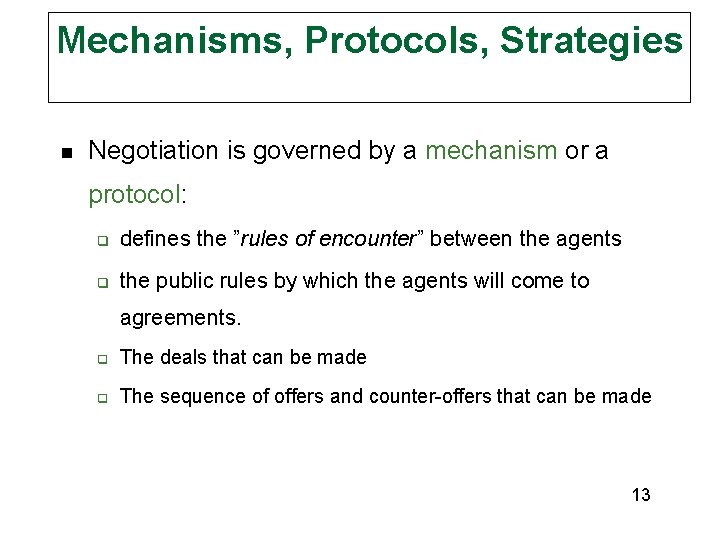

Mechanisms, Protocols, Strategies n Negotiation is governed by a mechanism or a protocol: q defines the ”rules of encounter” between the agents q the public rules by which the agents will come to agreements. q The deals that can be made q The sequence of offers and counter-offers that can be made 13

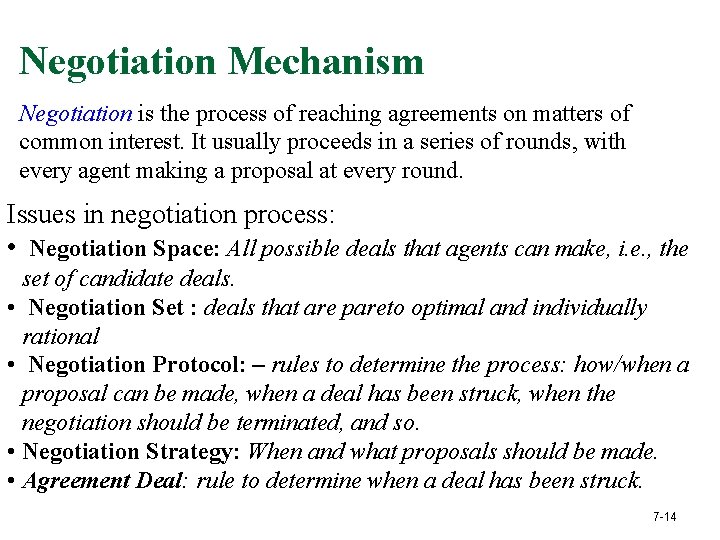

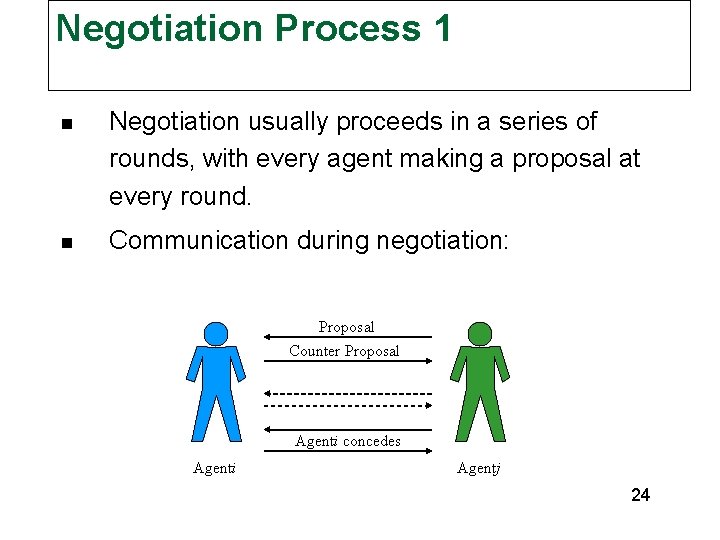

Negotiation Mechanism Negotiation is the process of reaching agreements on matters of common interest. It usually proceeds in a series of rounds, with every agent making a proposal at every round. Issues in negotiation process: • Negotiation Space: All possible deals that agents can make, i. e. , the set of candidate deals. • Negotiation Set : deals that are pareto optimal and individually rational • Negotiation Protocol: – rules to determine the process: how/when a proposal can be made, when a deal has been struck, when the negotiation should be terminated, and so. • Negotiation Strategy: When and what proposals should be made. • Agreement Deal: rule to determine when a deal has been struck. 7 -14

Typical Goals of Negotiation n n Efficiency – not waste utility. Pareto Optimal Stability – no agent have incentive to deviate from dominant strategy Simplicity – low computational demands on agents Distribution – no central decision maker Symmetry (possibly) – what is best for you would be best for me if our roles were reversed. May not want agents to play different roles. 15

Simple Model n n The rewards to be gained from negotiation are fixed and divided between the two parties Suppose (x, 1 -x) represents the portion of the utility each person gets. If the number of rounds are fixed, a person can propose ( , 1 - ) on the last round. Theoretically, a person would rather have than nothing. Even in multiple rounds: If you knew that the other agent wouldn’t offer you more than , it would be in your best interest to accept it. (So we have a pair of Nash Equilibrium strategies)16

Impatient players – shrinking pie n n n Discount factor of (a fraction in [0, 1]) is applied to the utility if don’t accept deal now. At time t, the value of slice x is tx The larger value of , the more patient the player is. Typically the players will have different values for , say 1 and 2 if player 1 offers player 2, he can do no better than accept it. 17

If not agreeing now costs you, how does that change things? n Consider a simple bargaining problem between two children, Alice and Bob. They are arguing over how to split an ice cream pie, which melts over time. For simplicity, assume the pie melts in equal amounts at every offer or counter-offer in the game. Let’s see how the division changes with different time intervals. 18

n n To begin the analysis, suppose there is just one offer. The older sister Alice can make an offer to Bob. If Bob agrees to the split of the ice cream pie, then both receive those amounts. But if he does not, then the pie melts and is ruined, so they both end up with nothing. This is a bit extreme case, but let’s see what happens for the sake of illustration. How will this negotiation turn out? 19

n n n Alice has a very strong negotiating position. If Bob refuses what she offers, then they both will end up with nothing. Thus, Alice knows she can offer Bob little, and he will have to accept it. So what happens is Alice offers Bob almost nothing, and he accepts. This one-stage bargaining problem is so interesting that it has its own name: it is called the ultimatum game. While theory says Bob should take a small offer–for if he refuses he gets nothing–experiments have shown this is not always how people play the game. When the ultimatum game is played by children, for instance, offers that stray too far from 50/50 are routinely rejected. People may act out of anger or because they do want to establish a reputation for what they will do if the game is repeated. n 20

Two time periods: Alice offers, then Bob counter-offers – melts half each time n Alice makes the first offer, but she has to think ahead. If she offers interval n n n Bob too little, then he can reject and wait for his turn to offer. Half of the pie will melt in the process, but Bob will be the one making the offer, and so he will have negotiating power. If the game goes until the second round, Bob can basically offer Alice nothing and take half the pie to himself. Alice can see she has limited power. If she does not give Bob a reasonable offer, he will reject and she will end up with nothing in the second round. So Alice will go ahead and make an offer of half to Bob in the first round, which is just enough for Bob to accept. Both end up with a 50/50 share of the pie. It is nice how that works out, as nothing is wasted and both parties end up with something. 21

3 periods: Alice, then Bob, then Alice n n n n We can continue to extend the game into more time periods. In this case, the pie melts in three periods, so it loses one-third of its size in each period. How will this game play out? We can look ahead and reason backwards. If the game goes until the last period, then one-third of the pie remains, and Alice is able to take it all. Bob would like to avoid getting nothing. So he needs to think carefully in his turn, during the middle period. At this point two-thirds of the pie remains. He has to offer one-third share (half of what is left) so that Alice can accept. This means Bob can at best get a one-third share of the original pie. Knowing this, Alice can offer Bob one-third in the first period, and Bob will have to accept. Notice that Alice ends up with two-thirds of the pie, which is more than half. But this makes sense because she has two possible turns to offer versus Bob only having one. In fact, Alice has this first-mover advantage any time the game has an odd number of periods. Now we can generalize. 22

n periods: Alice and Bob The division changes depending on whether the game has an even or alternate odd number of periods. I will spare the gory details and just say that it n n can be shown that: –If n is even: then the division is 50/50. This makes sense as Alice’s first-mover advantage gets balanced by the fact that Bob gets to offer last, a nice checks and balances system. –If n is odd, then the division is favored for Alice. Specifically, Alice ends up with a share of (n + 1)/(2 n) whereas Bob gets only (n – 1)/(2 n). For example, if the game has 11 periods, then the division would be 12/22 = 54. 5% for Alice and 10/22 = 45. 5% for Bob. So even though Alice makes the first and last offer, her advantage is only about 5 percentage points over the fair division. 23

Negotiation Process 1 n Negotiation usually proceeds in a series of rounds, with every agent making a proposal at every round. n Communication during negotiation: Proposal Counter Proposal Agenti concedes Agenti Agentj 24

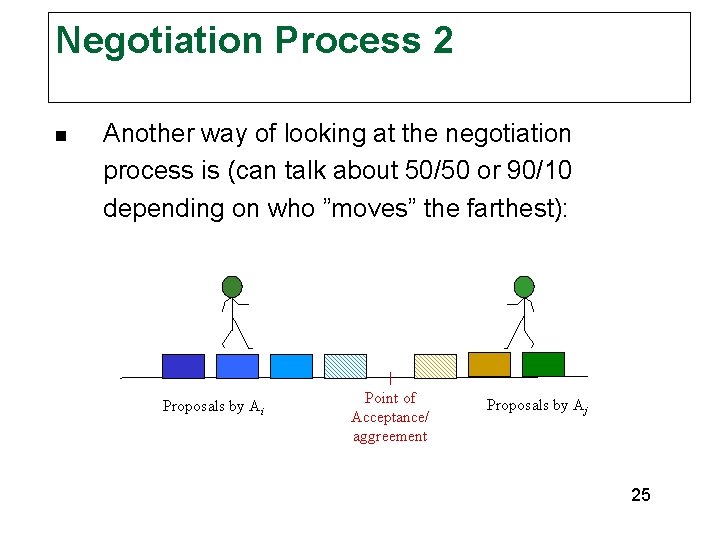

Negotiation Process 2 n Another way of looking at the negotiation process is (can talk about 50/50 or 90/10 depending on who ”moves” the farthest): Proposals by Ai Point of Acceptance/ aggreement Proposals by Aj 25

Single issue negotiation n n Like money Symmetric (If roles were reversed, I would benefit the same way you would) q q n If one task requires less time, both would benefit equally by taking less time utility for a task is experienced the same way by whomever is assigned to that task. Non-symmetric – we would benefit differently if roles were reversed q negotiate about who picks up an item, but you live closer to the store 26

Multiple Issue negotiation n n Could be hundreds of issues (cost, delivery date, size, quality) Some may be inter-related (as size goes down, cost goes down, quality goes up? ) Not clear what a true concession is (larger may be cheaper, but harder to store or spoils before can be used) May not even be clear what is up for negotiation (I didn’t realize having a bigger office was an option) (on the job…Ask for stock options, travel compensation, work from home, 4 - day work week. ) 27

How many agents are involved? n n n One to one One to many (auction is an example of one seller and many buyers) Many to many (could be divided into buyers and sellers, or all could be identical in role – like officemate) q n(n-1)/2 number of pairs 28

Jointly Improving Direction method Iterate n Mediator helps players criticize a tentative agreement (could be status quo) n Generates a compromise direction (where each of the k issues is a direction in k-space) n Mediator helps players to find a jointly preferred outcome along the compromise direction, and then proposes a new tentative agreement. 29

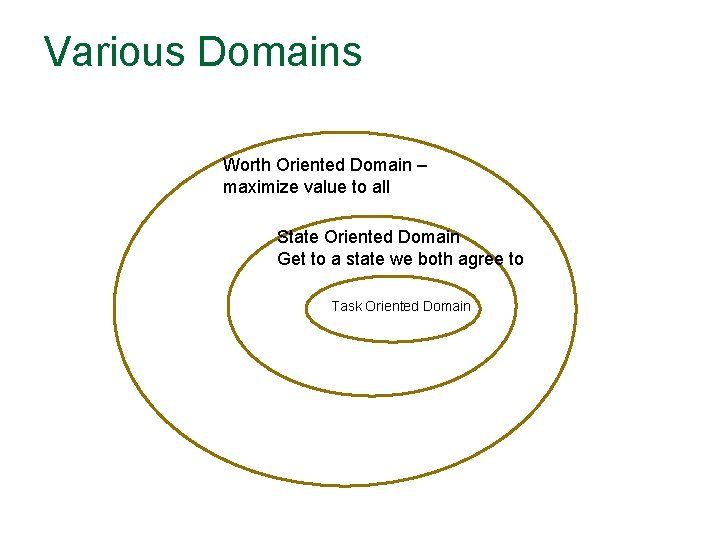

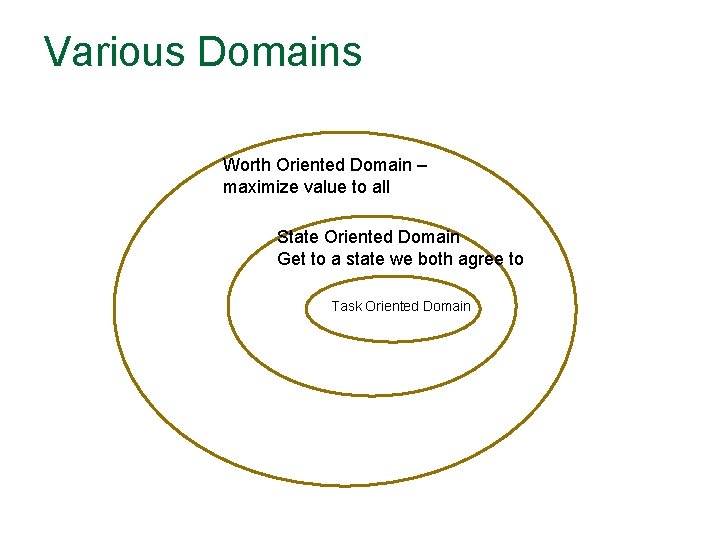

Various Domains Worth Oriented Domain – maximize value to all State Oriented Domain Get to a state we both agree to Task Oriented Domain

Typical Negotiation Problems Task-Oriented Domains(TOD): each agent has set of tasks that it has to achieve. The target of a negotiation is to minimize the cost of completing the tasks by divvying them up differently. State Oriented Domains(SOD): each agent is concerned with moving the world from an initial state into one of a set of goal states. The target of a negotiation is to achieve a common goal. Main attribute: actions have side effects (positive/negative). TOD is a subset of SOD. Agents can unintentionally achieve one another’s goals. Negative interactions can also occur. Utility = worth of goal – cost to achieve it Worth Oriented Domains(WOD): agents assign a worth to each potential state (via a function), which captures its desirability for the agent. The target of a negotiation is to maximize mutual worth (rather than worth to individual). Superset of SOD. Rates the acceptability of final states. Allows agents to compromise on their goals. 31

Negotiation Domains: Taskoriented ”Domains in which an agent’s activity can be defined in terms of a set of tasks that it has to achieve”, (Rosenschein & Zlotkin, 1994) q An agent can carry out the tasks without interference (or help) from other agents – such as ”who will deliver the mail” q Any agent can do any task. q Tasks redistributed for the benefit of all agents 32

Types of deals n n n Conflict deal: keep the same tasks as had originally Pure – divide up tasks Mixed – we divide up the tasks, but we decide probabilistically who should do what All or Nothing (A/N) - Mixed deal, with added requirement that we only have all or nothing deals (one of the tasks sets is empty) We don’t consider side-payments (other ways of balancing the benefit). 33

Examples of TOD n Parcel Delivery: Several couriers have to deliver sets of parcels to different cities. The target of negotiation is to reallocate deliveries so that the cost of travel is reduced. n Database Queries: Several agents have access to a common database, and each has to carry out a set of queries. The target of negotiation is to arrange queries so as to maximize efficiency of database operations (Join, Projection, Union, Intersection, …). e. g. , You are doing a join as part of another operation, so please save the results for me. 34

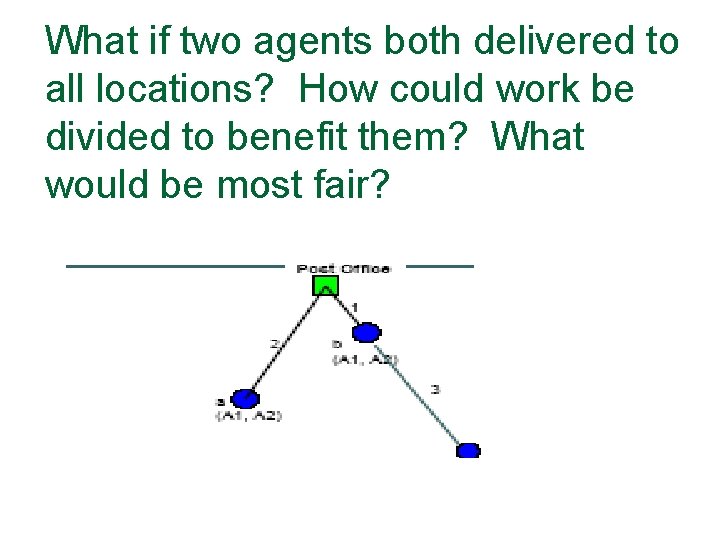

What if two agents both delivered to all locations? How could work be divided to benefit them? What would be most fair?

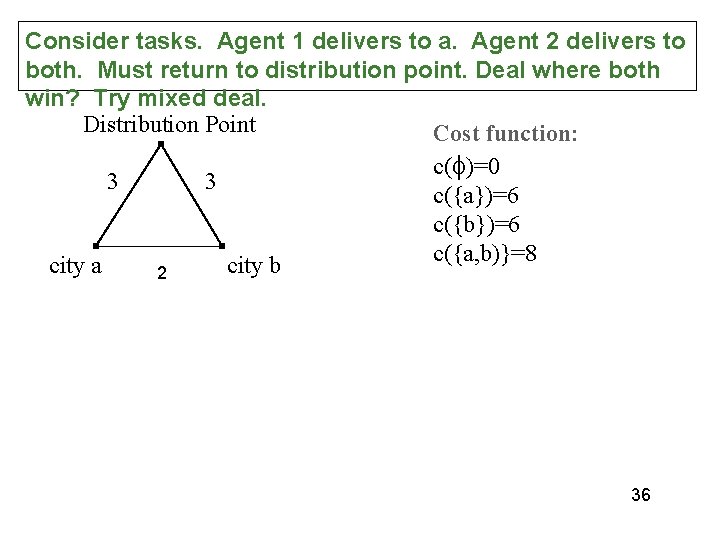

Consider tasks. Agent 1 delivers to a. Agent 2 delivers to both. Must return to distribution point. Deal where both win? Try mixed deal. Distribution Point Cost function: c( )=0 3 3 c({a})=6 c({b})=6 c({a, b)}=8 city a city b 2 36

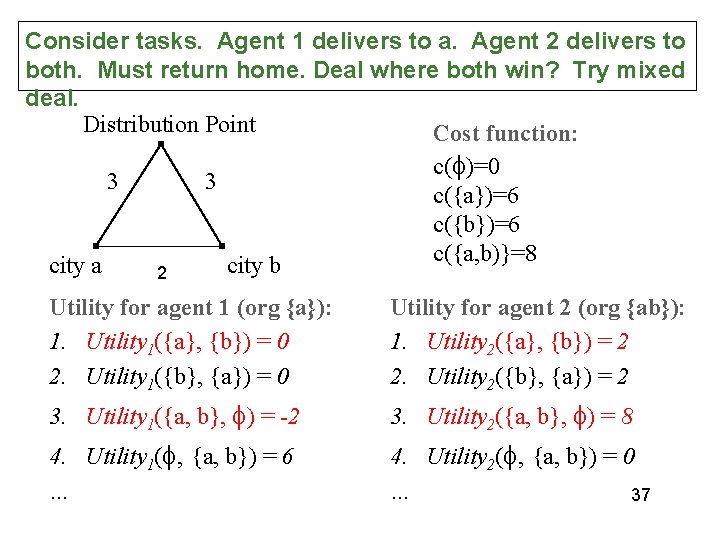

Consider tasks. Agent 1 delivers to a. Agent 2 delivers to both. Must return home. Deal where both win? Try mixed deal. Distribution Point Cost function: c( )=0 3 3 c({a})=6 c({b})=6 c({a, b)}=8 city a city b 2 Utility for agent 1 (org {a}): 1. Utility 1({a}, {b}) = 0 2. Utility 1({b}, {a}) = 0 Utility for agent 2 (org {ab}): 1. Utility 2({a}, {b}) = 2 2. Utility 2({b}, {a}) = 2 3. Utility 1({a, b}, ) = -2 3. Utility 2({a, b}, ) = 8 4. Utility 1( , {a, b}) = 6 … 4. Utility 2( , {a, b}) = 0 … 37

What mixed deals are possible if splitting utility is our goal? 38

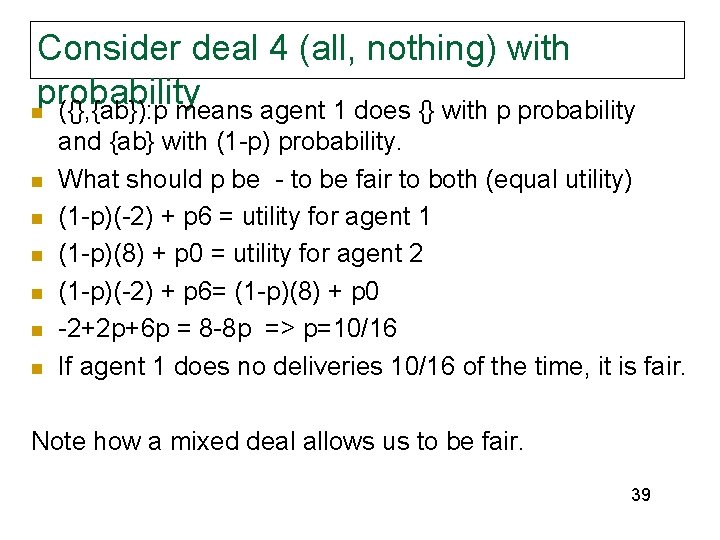

Consider deal 4 (all, nothing) with probability n ({}, {ab}): p means agent 1 does {} with p probability n n n and {ab} with (1 -p) probability. What should p be - to be fair to both (equal utility) (1 -p)(-2) + p 6 = utility for agent 1 (1 -p)(8) + p 0 = utility for agent 2 (1 -p)(-2) + p 6= (1 -p)(8) + p 0 -2+2 p+6 p = 8 -8 p => p=10/16 If agent 1 does no deliveries 10/16 of the time, it is fair. Note how a mixed deal allows us to be fair. 39

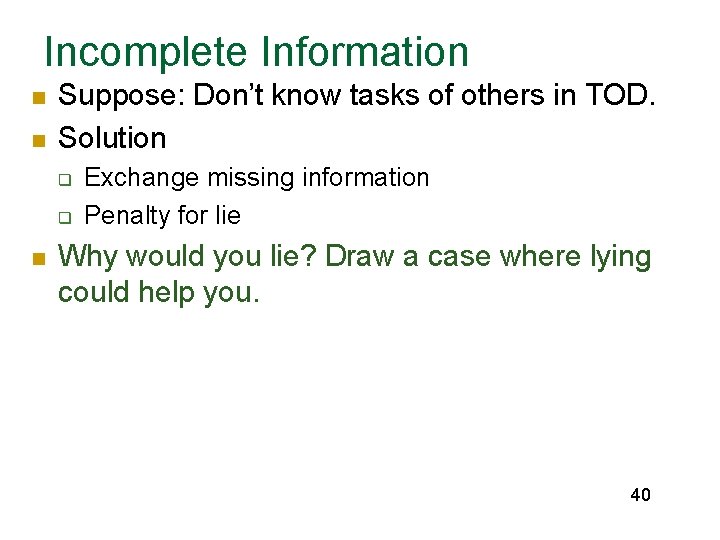

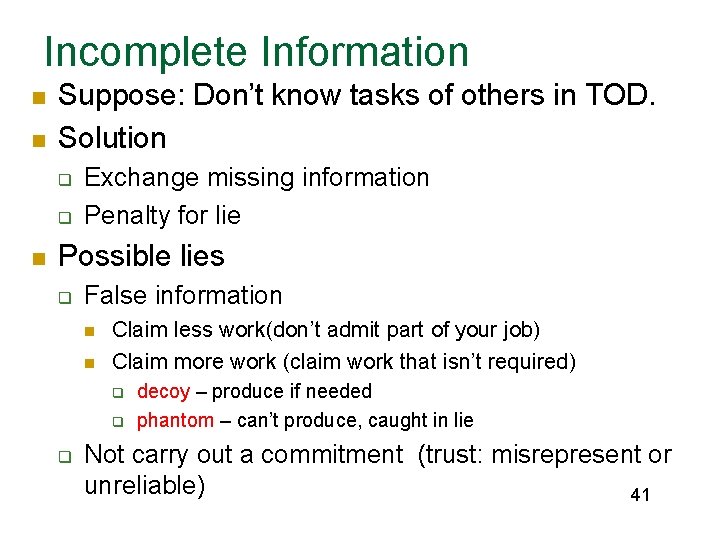

Incomplete Information n n Suppose: Don’t know tasks of others in TOD. Solution q q n Exchange missing information Penalty for lie Why would you lie? Draw a case where lying could help you. 40

Incomplete Information n n Suppose: Don’t know tasks of others in TOD. Solution q q n Exchange missing information Penalty for lie Possible lies q False information n n Claim less work(don’t admit part of your job) Claim more work (claim work that isn’t required) q q q decoy – produce if needed phantom – can’t produce, caught in lie Not carry out a commitment (trust: misrepresent or unreliable) 41

Difficult to think about n n n many situations many kinds of lies many kinds of deals Approach – divide into special cases so we can draw conclusions ** important research approach 42

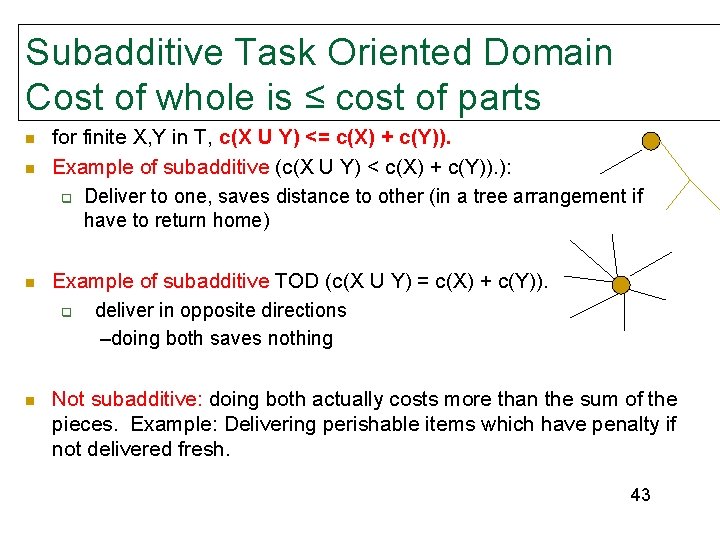

Subadditive Task Oriented Domain Cost of whole is ≤ cost of parts n n for finite X, Y in T, c(X U Y) <= c(X) + c(Y)). Example of subadditive (c(X U Y) < c(X) + c(Y)). ): q Deliver to one, saves distance to other (in a tree arrangement if have to return home) n Example of subadditive TOD (c(X U Y) = c(X) + c(Y)). q deliver in opposite directions –doing both saves nothing n Not subadditive: doing both actually costs more than the sum of the pieces. Example: Delivering perishable items which have penalty if not delivered fresh. 43

How can lying about work help? n Note: The only utilities you are trying to equalize are the change in utilities – not the unfairness of the original assignment. 44

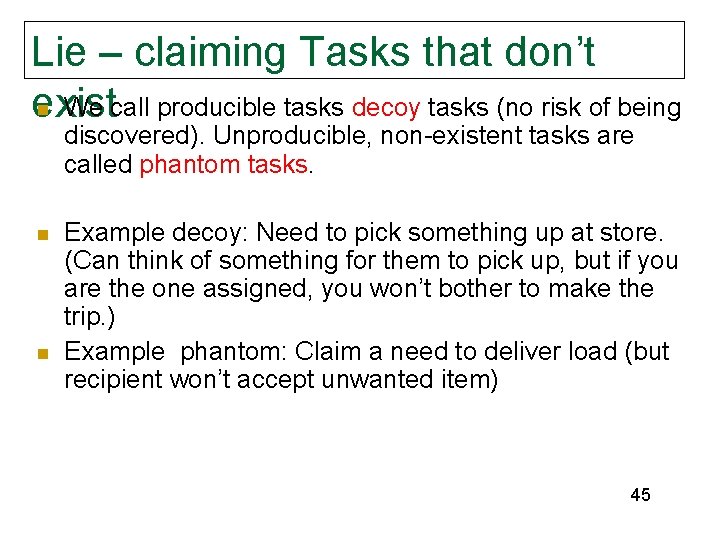

Lie – claiming Tasks that don’t n We call producible tasks decoy tasks (no risk of being exist discovered). Unproducible, non-existent tasks are called phantom tasks. n n Example decoy: Need to pick something up at store. (Can think of something for them to pick up, but if you are the one assigned, you won’t bother to make the trip. ) Example phantom: Claim a need to deliver load (but recipient won’t accept unwanted item) 45

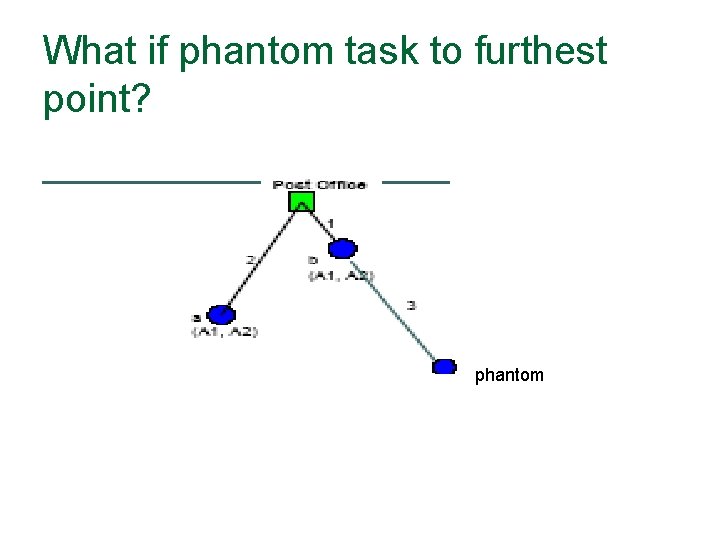

What if phantom task to furthest point? phantom

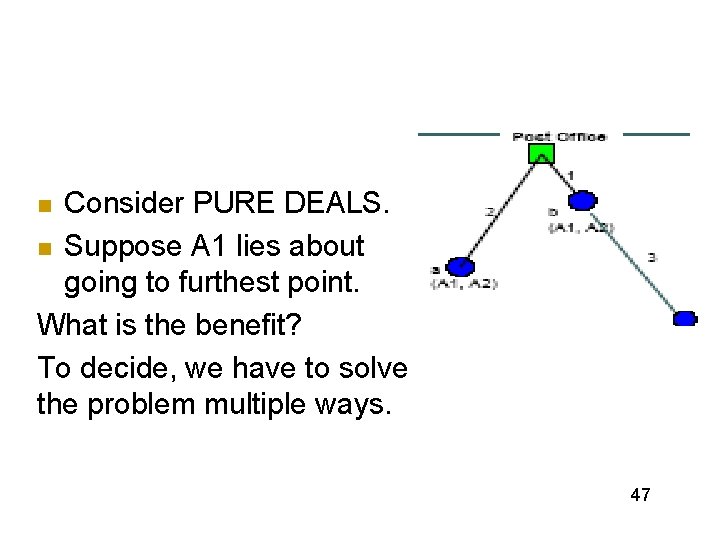

Consider PURE DEALS. n Suppose A 1 lies about going to furthest point. What is the benefit? To decide, we have to solve the problem multiple ways. n 47

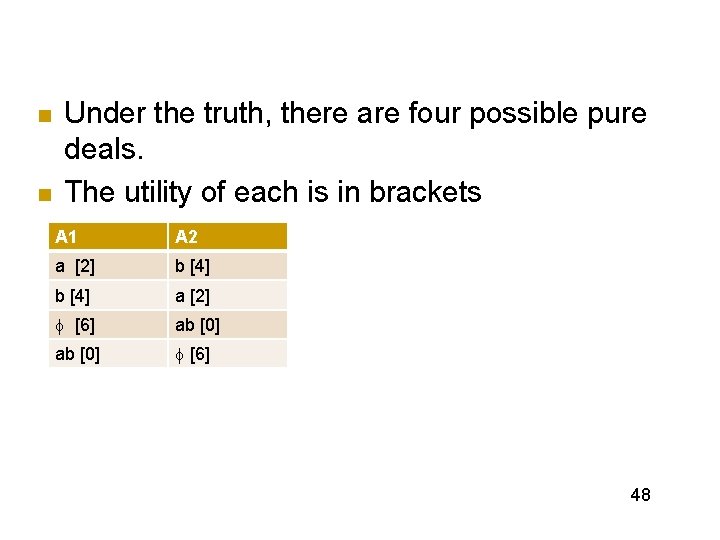

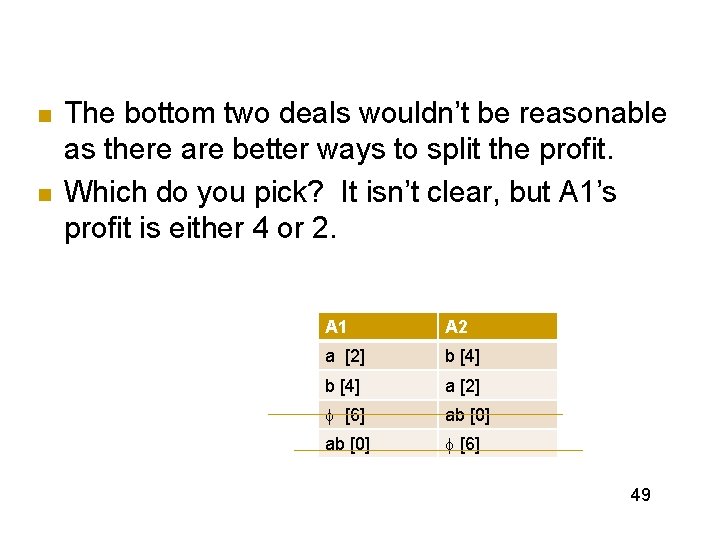

n n Under the truth, there are four possible pure deals. The utility of each is in brackets A 1 A 2 a [2] b [4] a [2] [6] ab [0] [6] 48

n n The bottom two deals wouldn’t be reasonable as there are better ways to split the profit. Which do you pick? It isn’t clear, but A 1’s profit is either 4 or 2. A 1 A 2 a [2] b [4] a [2] [6] ab [0] [6] 49

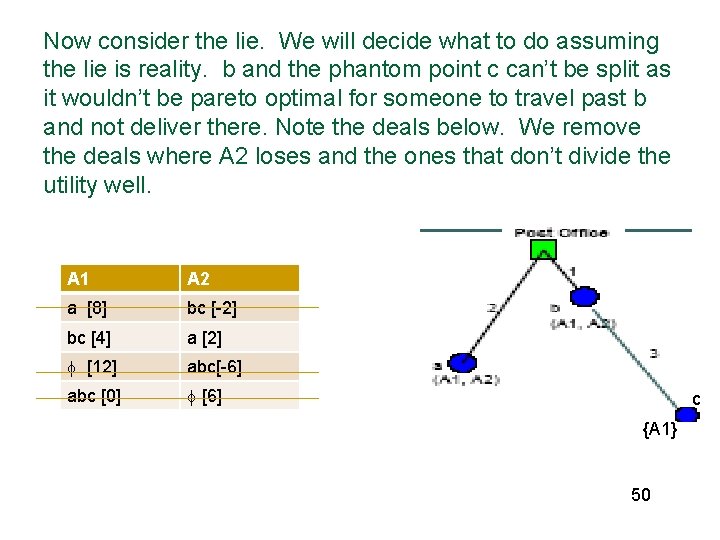

Now consider the lie. We will decide what to do assuming the lie is reality. b and the phantom point c can’t be split as it wouldn’t be pareto optimal for someone to travel past b and not deliver there. Note the deals below. We remove the deals where A 2 loses and the ones that don’t divide the utility well. A 1 A 2 a [8] bc [-2] bc [4] a [2] [12] abc[-6] abc [0] [6] c {A 1} 50

Great. So A 1 is assigned bc – so A 2 will never know that there was no real task at c. Of course, A 1 won’t really go to c, but he still saves 4 by not having to go to a. Under the truth he would either have had utility 2 or 4, now he has 4 for sure. A 1 A 2 a [8] bc [-2] bc [4] a [2] [12] abc[-6] abc [0] [6] c {A 1} If we maximize the product of the utilities, what would we pick? 51

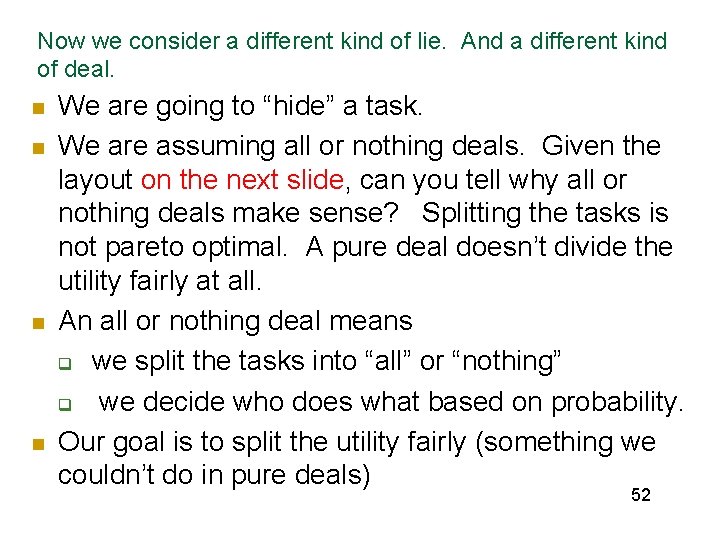

Now we consider a different kind of lie. And a different kind of deal. n n We are going to “hide” a task. We are assuming all or nothing deals. Given the layout on the next slide, can you tell why all or nothing deals make sense? Splitting the tasks is not pareto optimal. A pure deal doesn’t divide the utility fairly at all. An all or nothing deal means q we split the tasks into “all” or “nothing” q we decide who does what based on probability. Our goal is to split the utility fairly (something we couldn’t do in pure deals) 52

What if hidden task to b? {A 1} Agent 1: f (public) and b (hides) Agent 2: e Must return to post office {A 1} {A 2} 53

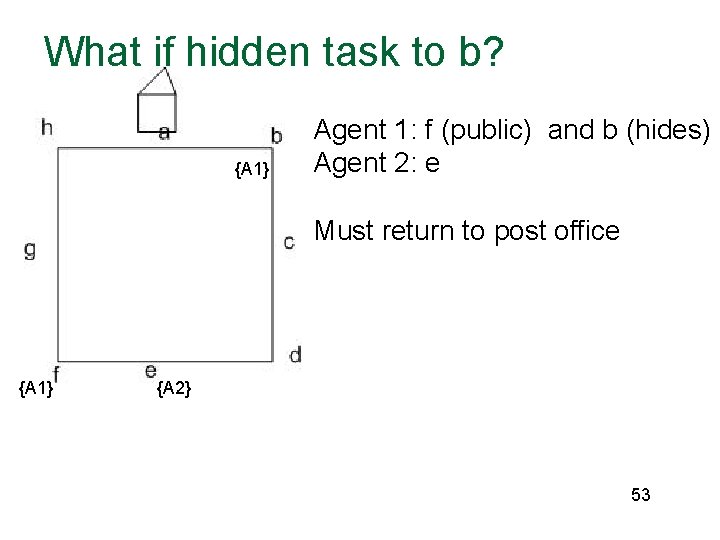

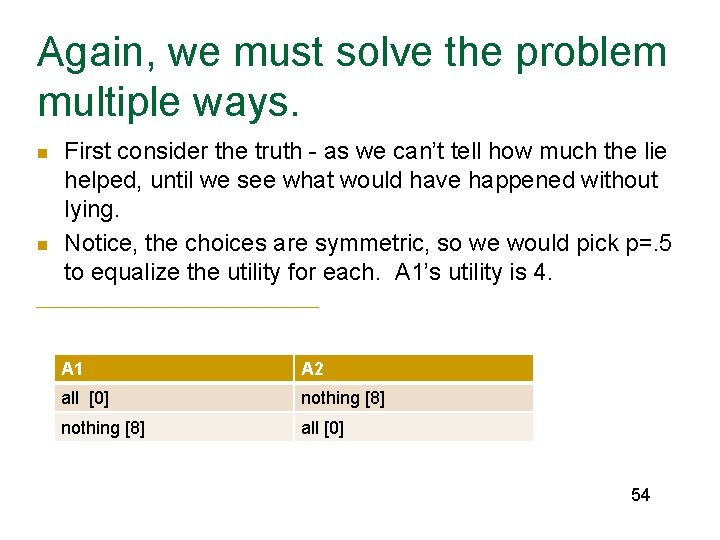

Again, we must solve the problem multiple ways. n n First consider the truth - as we can’t tell how much the lie helped, until we see what would have happened without lying. Notice, the choices are symmetric, so we would pick p=. 5 to equalize the utility for each. A 1’s utility is 4. A 1 A 2 all [0] nothing [8] all [0] 54

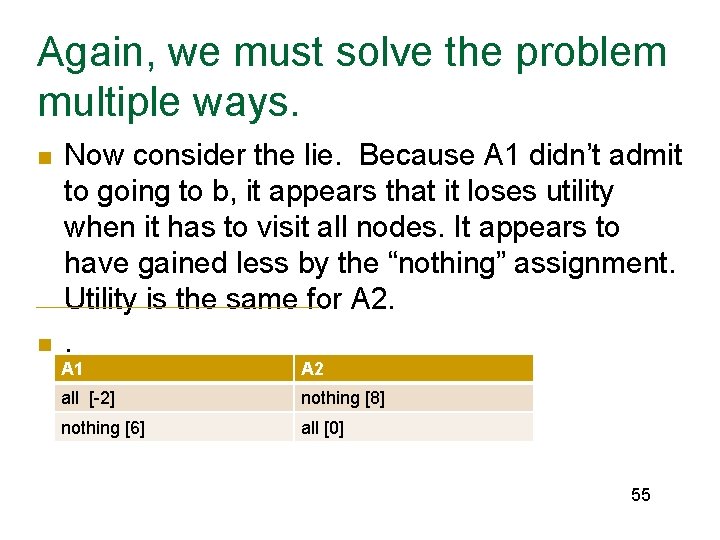

Again, we must solve the problem multiple ways. n n Now consider the lie. Because A 1 didn’t admit to going to b, it appears that it loses utility when it has to visit all nodes. It appears to have gained less by the “nothing” assignment. Utility is the same for A 2. . A 1 A 2 all [-2] nothing [8] nothing [6] all [0] 55

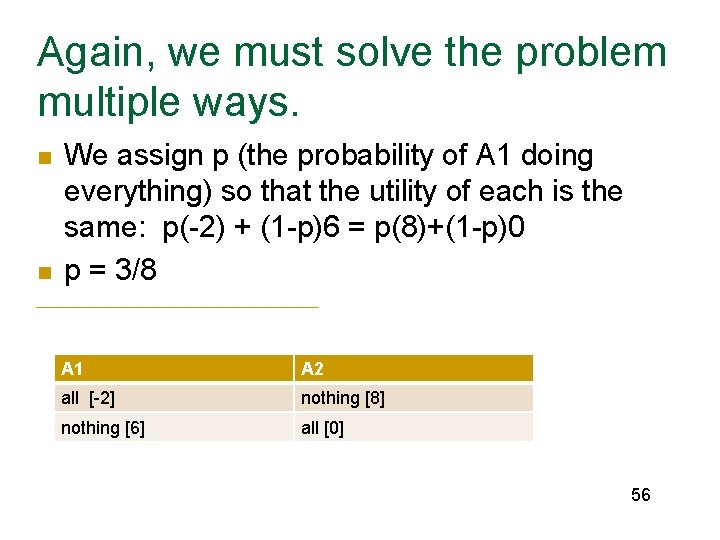

Again, we must solve the problem multiple ways. n n We assign p (the probability of A 1 doing everything) so that the utility of each is the same: p(-2) + (1 -p)6 = p(8)+(1 -p)0 p = 3/8 A 1 A 2 all [-2] nothing [8] nothing [6] all [0] 56

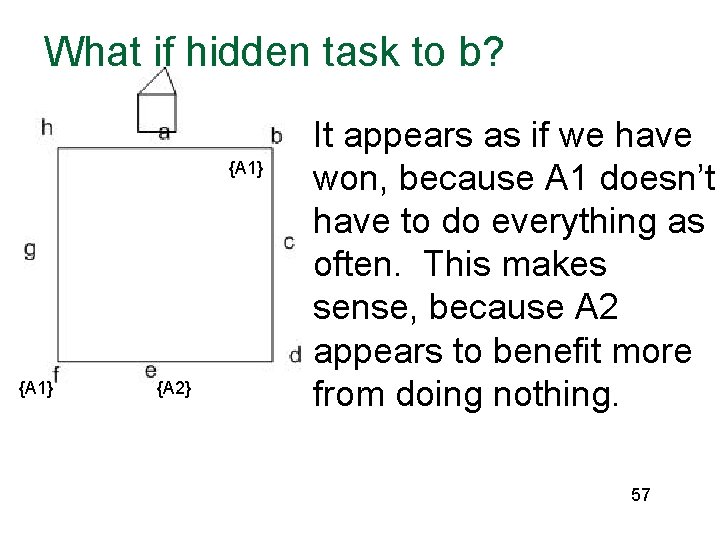

What if hidden task to b? {A 1} {A 2} It appears as if we have won, because A 1 doesn’t have to do everything as often. This makes sense, because A 2 appears to benefit more from doing nothing. 57

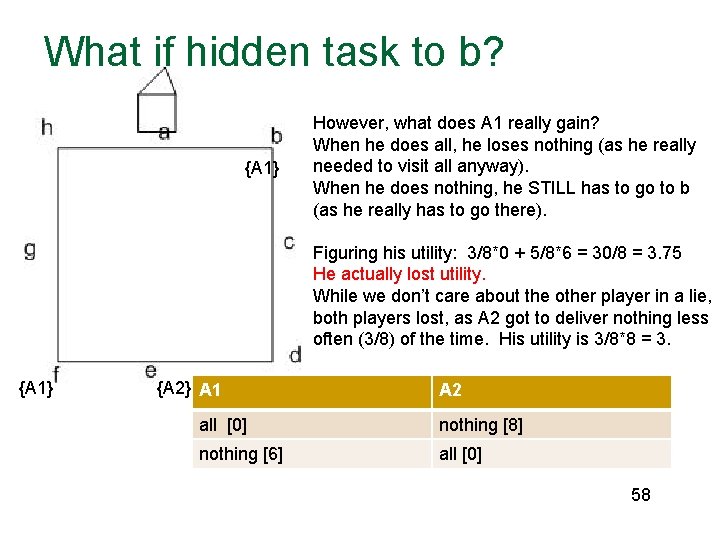

What if hidden task to b? {A 1} However, what does A 1 really gain? When he does all, he loses nothing (as he really needed to visit all anyway). When he does nothing, he STILL has to go to b (as he really has to go there). Figuring his utility: 3/8*0 + 5/8*6 = 30/8 = 3. 75 He actually lost utility. While we don’t care about the other player in a lie, both players lost, as A 2 got to deliver nothing less often (3/8) of the time. His utility is 3/8*8 = 3. {A 1} {A 2} A 1 A 2 all [0] nothing [8] nothing [6] all [0] 58

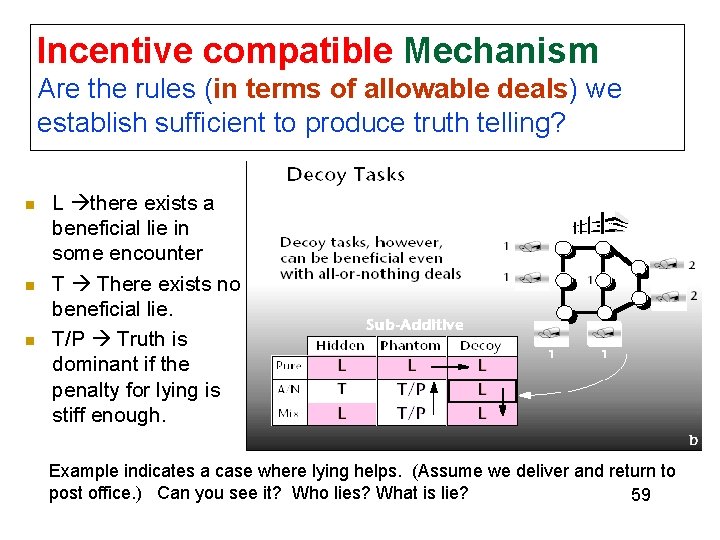

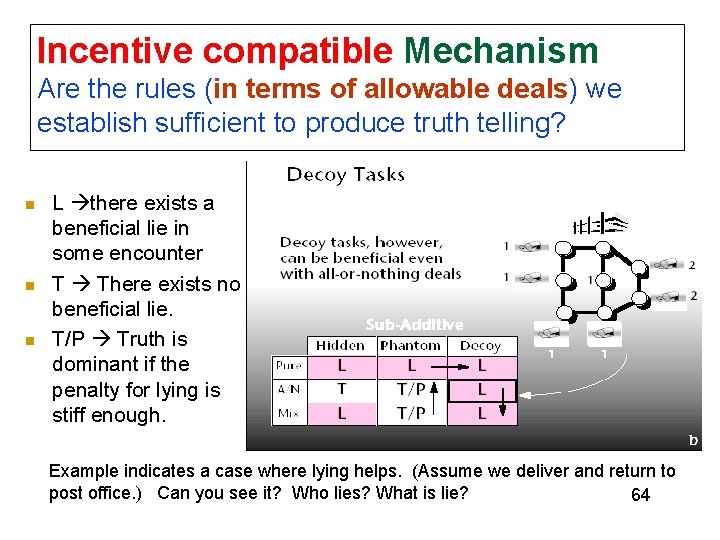

Incentive compatible Mechanism Are the rules (in terms of allowable deals) we establish sufficient to produce truth telling? n n n L there exists a beneficial lie in some encounter T There exists no beneficial lie. T/P Truth is dominant if the penalty for lying is stiff enough. Example indicates a case where lying helps. (Assume we deliver and return to post office. ) Can you see it? Who lies? What is lie? 59

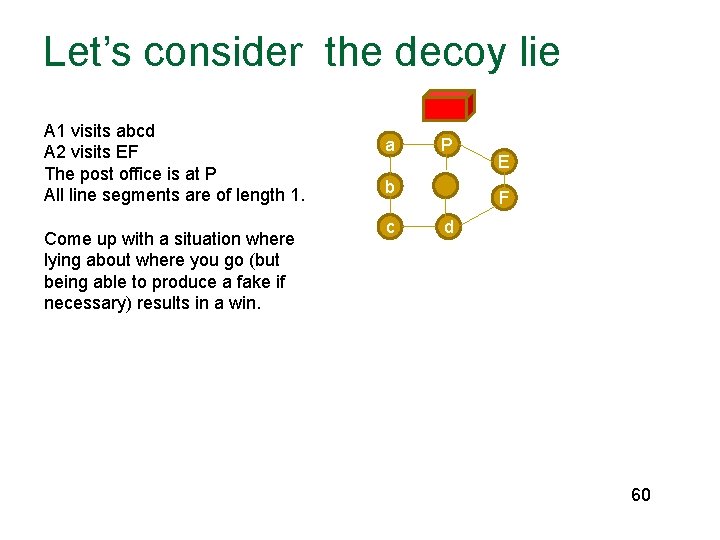

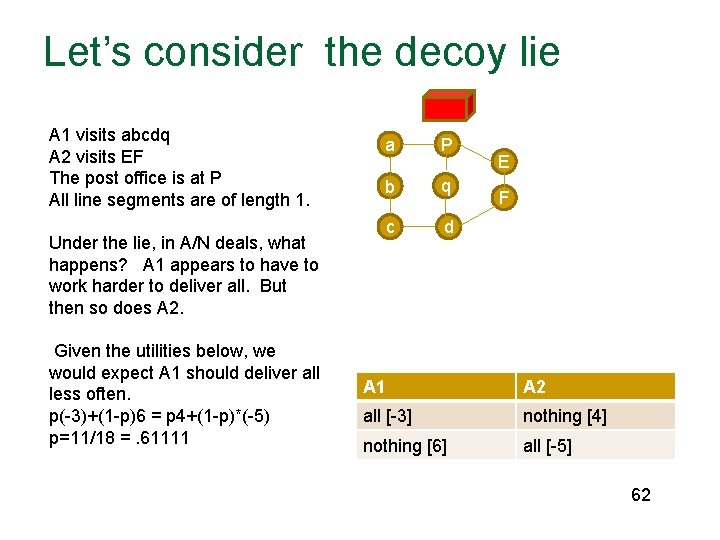

Let’s consider the decoy lie A 1 visits abcd A 2 visits EF The post office is at P All line segments are of length 1. Come up with a situation where lying about where you go (but being able to produce a fake if necessary) results in a win. a P b c E F d 60

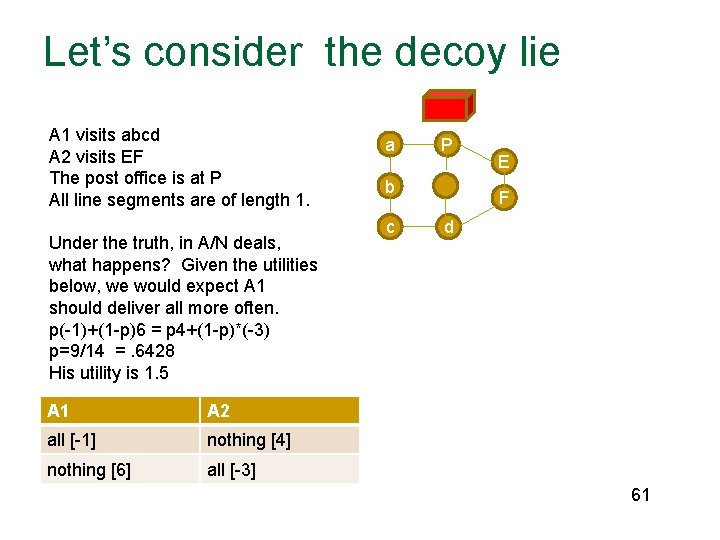

Let’s consider the decoy lie A 1 visits abcd A 2 visits EF The post office is at P All line segments are of length 1. Under the truth, in A/N deals, what happens? Given the utilities below, we would expect A 1 should deliver all more often. p(-1)+(1 -p)6 = p 4+(1 -p)*(-3) p=9/14 =. 6428 His utility is 1. 5 A 1 A 2 all [-1] nothing [4] nothing [6] all [-3] a P b c E F d 61

Let’s consider the decoy lie A 1 visits abcdq A 2 visits EF The post office is at P All line segments are of length 1. Under the lie, in A/N deals, what happens? A 1 appears to have to work harder to deliver all. But then so does A 2. Given the utilities below, we would expect A 1 should deliver all less often. p(-3)+(1 -p)6 = p 4+(1 -p)*(-5) p=11/18 =. 61111 a P b q c d E F A 1 A 2 all [-3] nothing [4] nothing [6] all [-5] 62

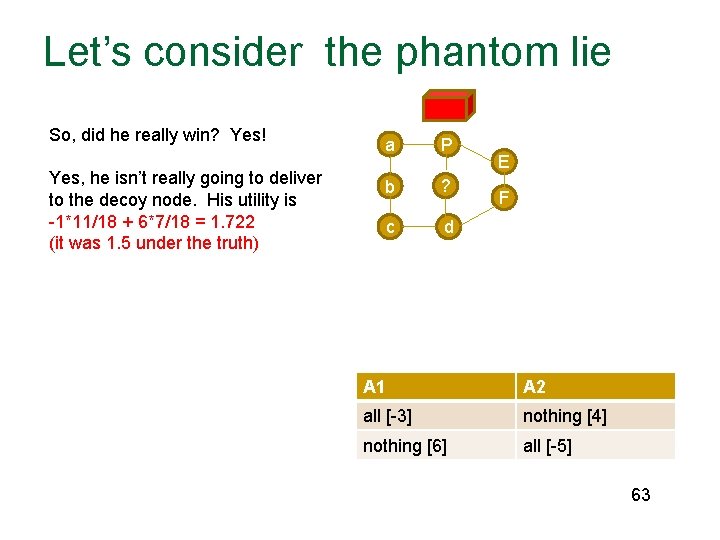

Let’s consider the phantom lie So, did he really win? Yes! Yes, he isn’t really going to deliver to the decoy node. His utility is -1*11/18 + 6*7/18 = 1. 722 (it was 1. 5 under the truth) a P b ? c d E F A 1 A 2 all [-3] nothing [4] nothing [6] all [-5] 63

Incentive compatible Mechanism Are the rules (in terms of allowable deals) we establish sufficient to produce truth telling? n n n L there exists a beneficial lie in some encounter T There exists no beneficial lie. T/P Truth is dominant if the penalty for lying is stiff enough. Example indicates a case where lying helps. (Assume we deliver and return to post office. ) Can you see it? Who lies? What is lie? 64

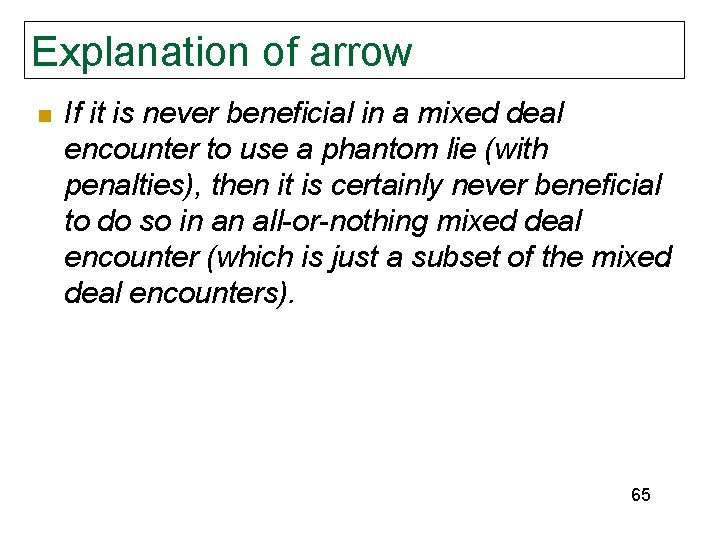

Explanation of arrow n If it is never beneficial in a mixed deal encounter to use a phantom lie (with penalties), then it is certainly never beneficial to do so in an all-or-nothing mixed deal encounter (which is just a subset of the mixed deal encounters). 65

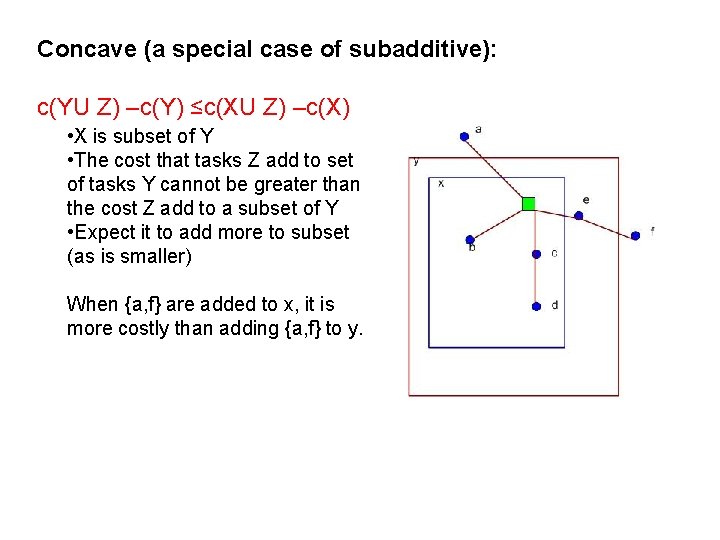

Concave (a special case of subadditive): c(YU Z) –c(Y) ≤c(XU Z) –c(X) • X is subset of Y • The cost that tasks Z add to set of tasks Y cannot be greater than the cost Z add to a subset of Y • Expect it to add more to subset (as is smaller) When {a, f} are added to x, it is more costly than adding {a, f} to y.

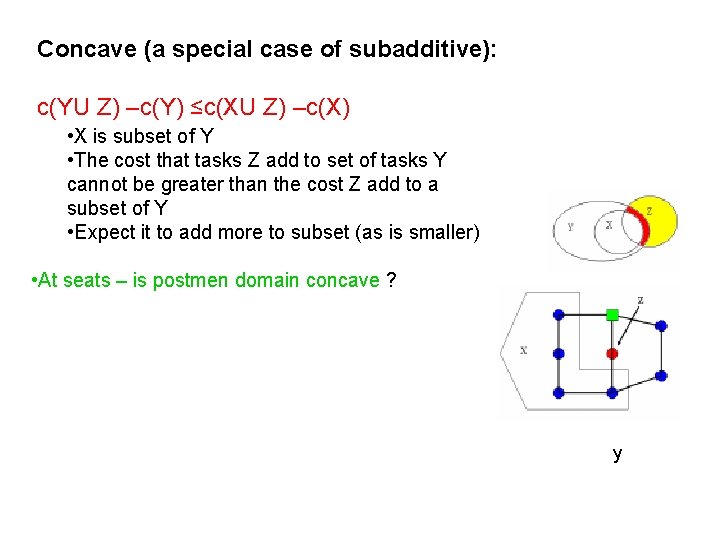

Concave (a special case of subadditive): c(YU Z) –c(Y) ≤c(XU Z) –c(X) • X is subset of Y • The cost that tasks Z add to set of tasks Y cannot be greater than the cost Z add to a subset of Y • Expect it to add more to subset (as is smaller) • At seats – is postmen domain concave ? y

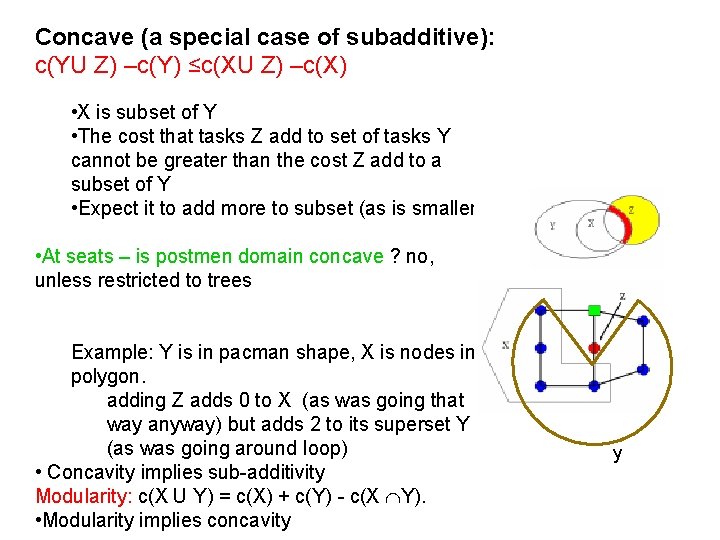

Concave (a special case of subadditive): c(YU Z) –c(Y) ≤c(XU Z) –c(X) • X is subset of Y • The cost that tasks Z add to set of tasks Y cannot be greater than the cost Z add to a subset of Y • Expect it to add more to subset (as is smaller) • At seats – is postmen domain concave ? no, unless restricted to trees Example: Y is in pacman shape, X is nodes in polygon. adding Z adds 0 to X (as was going that way anyway) but adds 2 to its superset Y (as was going around loop) • Concavity implies sub-additivity Modularity: c(X U Y) = c(X) + c(Y) - c(X Y). • Modularity implies concavity y

Modularity: c(X U Y) = c(X) + c(Y) - c(X Y). • Modularity implies concavity Draw a type of graph in which modularity always occurs. y

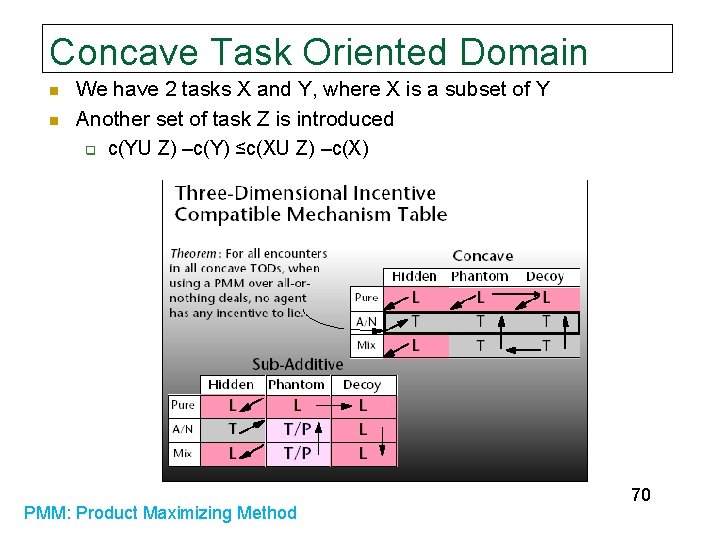

Concave Task Oriented Domain n n We have 2 tasks X and Y, where X is a subset of Y Another set of task Z is introduced q c(YU Z) –c(Y) ≤c(XU Z) –c(X) PMM: Product Maximizing Method 70

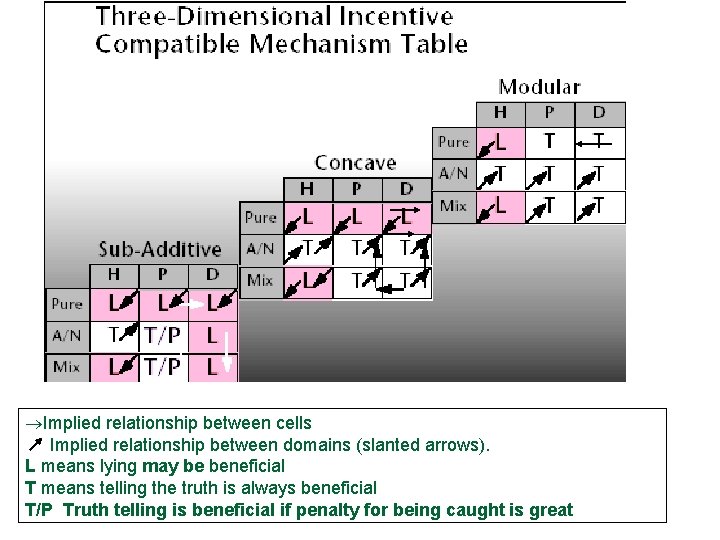

Explanation of Previous Chart n n n Arrows indicate reasons we know this fact (diagonal arrows are between domains). For example, What is true of a phantom task, may be true for a decoy task in same domain as a phantom is just a decoy task we don’t have to create. Similarly, what is true for a mixed deal may be true for an all or nothing deal (in the same domain) as a mixed deal is an all or nothing deal where one choice is empty. The direction of the relationship may depend on truth (never helps) or lie (sometimes helps). The relationships can also go between domains as subadditive is a superclass of concave and a super class of modular. 71

Modular TOD n n n c(X U Y) = c(X) + c(Y) - c(X Y). X and Y are sets of tasks Notice modular encourages truth telling, more than others 72

®Implied relationship between cells Implied relationship between domains (slanted arrows). L means lying may be beneficial T means telling the truth is always beneficial T/P Truth telling is beneficial if penalty for being caught is great 73

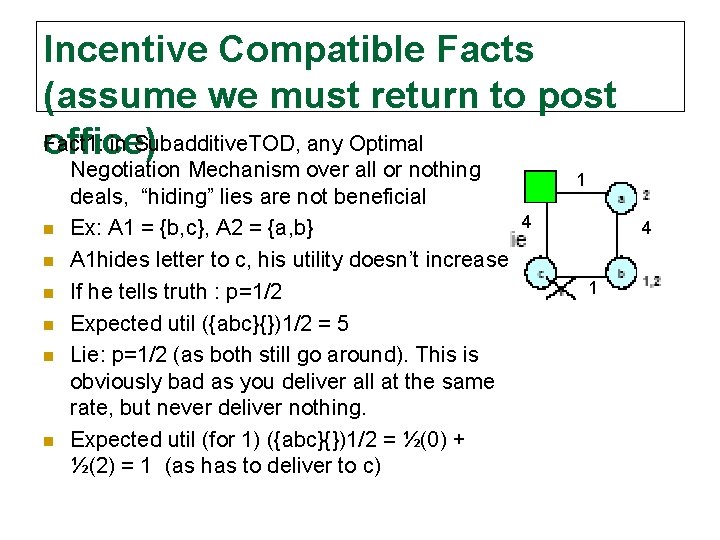

Incentive Compatible Facts (assume we must return to post Fact 1: in Subadditive. TOD, any Optimal office) n n n Negotiation Mechanism over all or nothing deals, “hiding” lies are not beneficial 4 Ex: A 1 = {b, c}, A 2 = {a, b} A 1 hides letter to c, his utility doesn’t increase. If he tells truth : p=1/2 Expected util ({abc}{})1/2 = 5 Lie: p=1/2 (as both still go around). This is obviously bad as you deliver all at the same rate, but never deliver nothing. Expected util (for 1) ({abc}{})1/2 = ½(0) + ½(2) = 1 (as has to deliver to c) 1 4 1

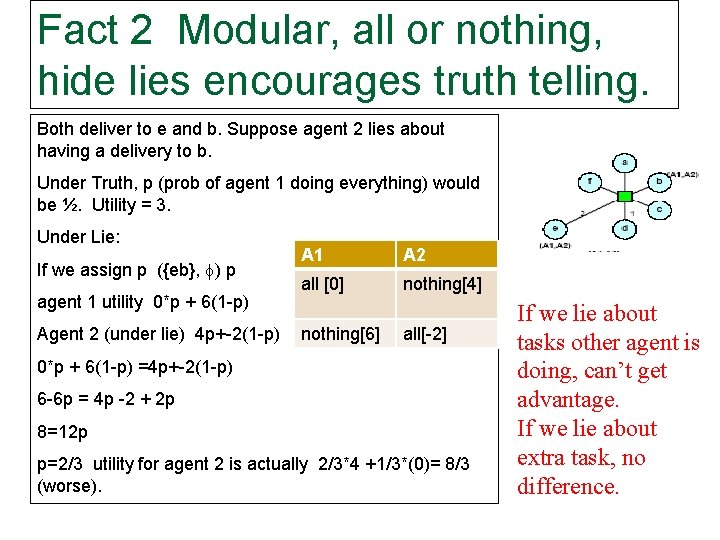

Fact 2 Modular, all or nothing, hide lies encourages truth telling. Both deliver to e and b. Suppose agent 2 lies about having a delivery to b. Under Truth, p (prob of agent 1 doing everything) would be ½. Utility = 3. Under Lie: If we assign p ({eb}, ) p agent 1 utility 0*p + 6(1 -p) Agent 2 (under lie) 4 p+-2(1 -p) A 1 A 2 all [0] nothing[4] nothing[6] all[-2] 0*p + 6(1 -p) =4 p+-2(1 -p) 6 -6 p = 4 p -2 + 2 p 8=12 p p=2/3 utility for agent 2 is actually 2/3*4 +1/3*(0)= 8/3 (worse). If we lie about tasks other agent is doing, can’t get advantage. If we lie about extra task, no difference.

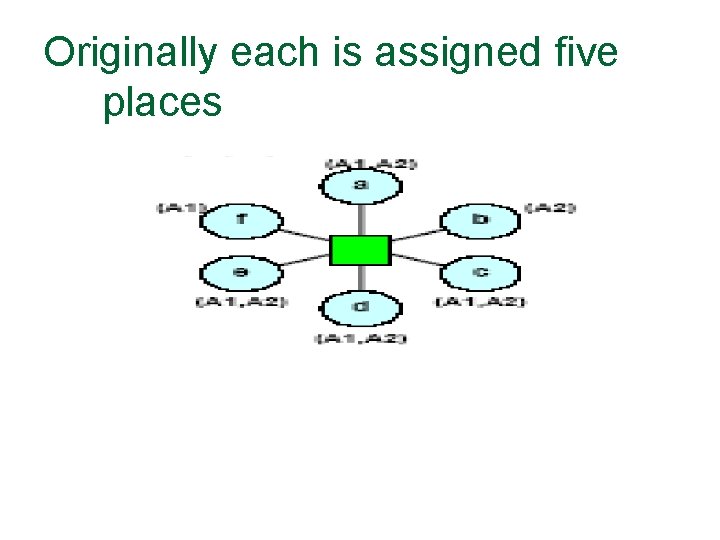

Originally each is assigned five places

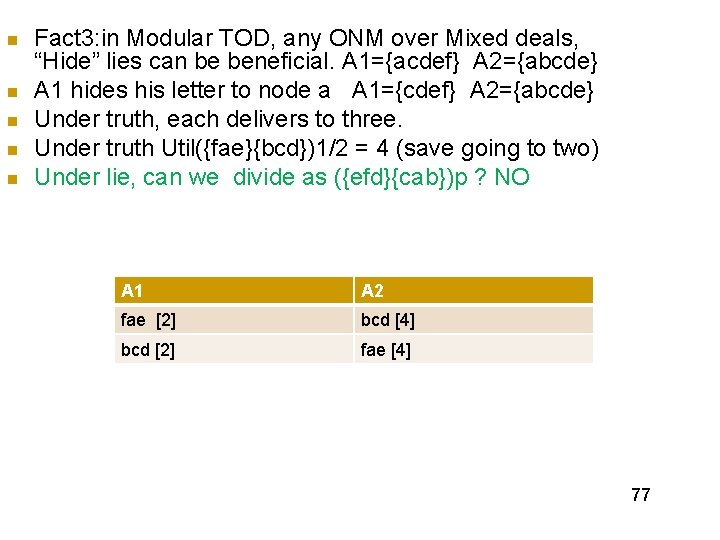

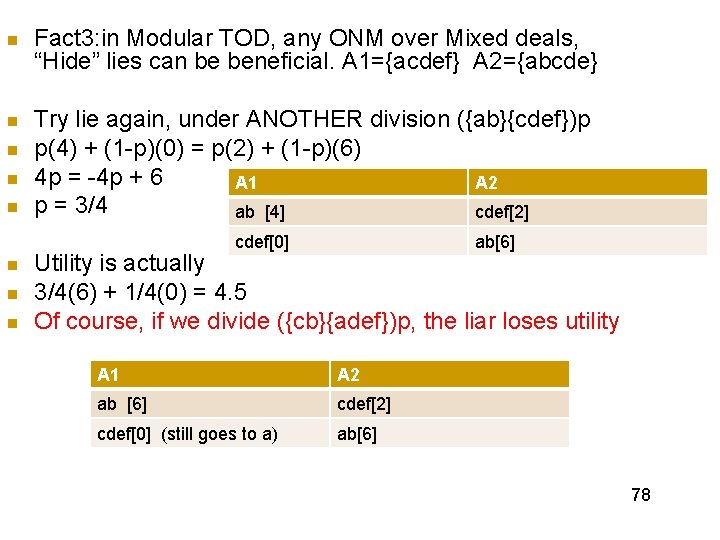

n n n Fact 3: in Modular TOD, any ONM over Mixed deals, “Hide” lies can be beneficial. A 1={acdef} A 2={abcde} A 1 hides his letter to node a A 1={cdef} A 2={abcde} Under truth, each delivers to three. Under truth Util({fae}{bcd})1/2 = 4 (save going to two) Under lie, can we divide as ({efd}{cab})p ? NO A 1 A 2 fae [2] bcd [4] bcd [2] fae [4] 77

n Fact 3: in Modular TOD, any ONM over Mixed deals, “Hide” lies can be beneficial. A 1={acdef} A 2={abcde} n Try lie again, under ANOTHER division ({ab}{cdef})p p(4) + (1 -p)(0) = p(2) + (1 -p)(6) 4 p = -4 p + 6 A 1 A 2 p = 3/4 ab [4] cdef[2] n n n cdef[0] n n n ab[6] Utility is actually 3/4(6) + 1/4(0) = 4. 5 Of course, if we divide ({cb}{adef})p, the liar loses utility A 1 A 2 ab [6] cdef[2] cdef[0] (still goes to a) ab[6] 78

Any idea? n How are hide lies profitable mixed deals for the Modular task domain? a b 79

Conclusion q q In order to use Negotiation Protocols, it is necessary to know when protocols are appropriate TOD’s cover an important set of Multi-agent interaction 80

Various Domains Worth Oriented Domain – maximize value to all State Oriented Domain Get to a state we both agree to Task Oriented Domain

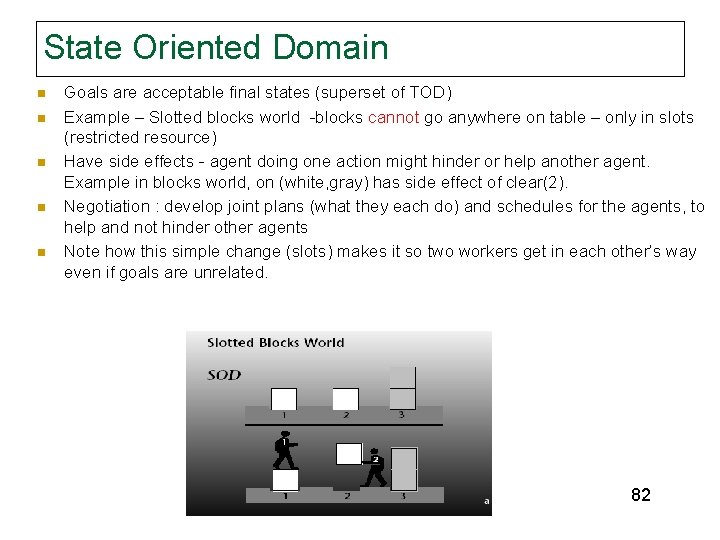

State Oriented Domain n n Goals are acceptable final states (superset of TOD) Example – Slotted blocks world -blocks cannot go anywhere on table – only in slots (restricted resource) Have side effects - agent doing one action might hinder or help another agent. Example in blocks world, on (white, gray) has side effect of clear(2). Negotiation : develop joint plans (what they each do) and schedules for the agents, to help and not hinder other agents Note how this simple change (slots) makes it so two workers get in each other’s way even if goals are unrelated. 82

Assumptions of SOD n n n Agents will maximize expected utility (will prefer 51% chance of getting $100 than a sure $50) Agent cannot commit himself (as part of current negotiation) to behavior in future negotiation. No explicit utility transfer (no side-payment that can be used to compensate one agent for a disadvantageous agreement) Inter-agent comparison of utility: common utility units Symmetric abilities (all can perform tasks, and cost is same regardless of agent performing) Binding commitments 83

Achievement of Final State n n n Goal of each agent is represented as a set of states that they would be happy with. Looking for a state in intersection of goals Possibilities: q (GREAT) Both can be achieved, at gain to both (e. g. travel to same location and split cost) q (IMPOSSIBLE) Goals may contradict, so no mutually acceptable state (e. g. , both need the car) q (NEED ALT) Can find common state, but perhaps it cannot be reached with the primitive operations in the domain (could both travel together, but may need to know how to pickup another) q (NOT WORTH IT) Might be a reachable state which satisfies both, but may be too expensive – unwilling to expend effort (i. e. , we could save a bit if we car-pooled, but is too complicated for so little gain). 84

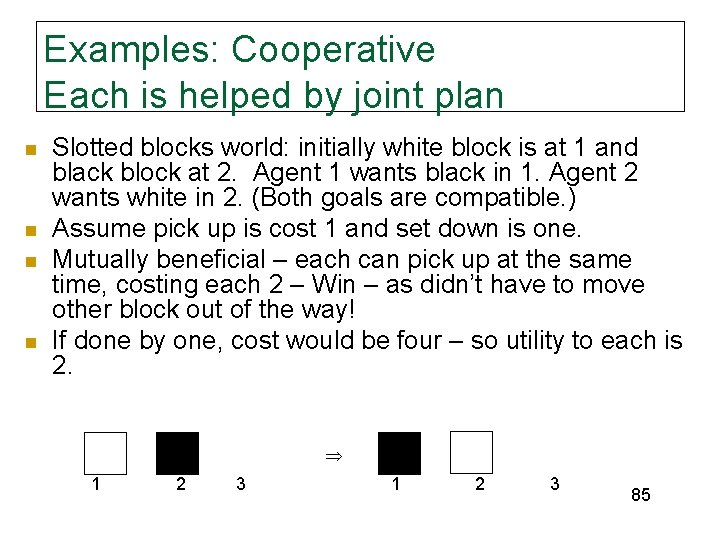

Examples: Cooperative Each is helped by joint plan n n Slotted blocks world: initially white block is at 1 and black block at 2. Agent 1 wants black in 1. Agent 2 wants white in 2. (Both goals are compatible. ) Assume pick up is cost 1 and set down is one. Mutually beneficial – each can pick up at the same time, costing each 2 – Win – as didn’t have to move other block out of the way! If done by one, cost would be four – so utility to each is 2. 1 2 3 1 2 3 85

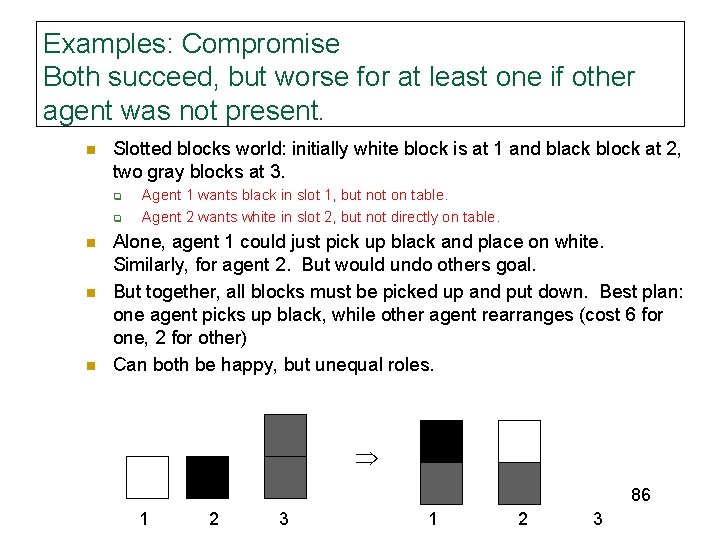

Examples: Compromise Both succeed, but worse for at least one if other agent was not present. n Slotted blocks world: initially white block is at 1 and black block at 2, two gray blocks at 3. q q n n n Agent 1 wants black in slot 1, but not on table. Agent 2 wants white in slot 2, but not directly on table. Alone, agent 1 could just pick up black and place on white. Similarly, for agent 2. But would undo others goal. But together, all blocks must be picked up and put down. Best plan: one agent picks up black, while other agent rearranges (cost 6 for one, 2 for other) Can both be happy, but unequal roles. 86 1 2 3 1 2 3

Example: conflict n n n I want black on white (in slot 1) You want white on black (in slot 1) Can’t both win. Could flip a coin to decide who wins. Better than both losing. Weightings on coin needn’t be 50 -50. May make sense to have person with highest worth get his way – as utility is greater. (Would accomplish his goal alone) Efficient but not fair? What if we could transfer half of the gained utility to the other agent? This is not normally allowed, but could work out well. 87

Negotiation Domains: Worth-oriented – more flexible n ”Domains where agents assign a worth to each potential state (of the environment), which captures its desirability for the agent”, (Rosenschein & Zlotkin, 1994) n agent’s goal is to bring about the state of the environment with highest value n we assume that the collection of agents have available a set of joint plans – a joint plan is executed by several different agents n Note – not ”all or nothing” – but how close you got to goal. 88

Worth Oriented Domain n n Rates the acceptability of final states Allows partially completed goals Negotiation : a joint plan, schedules, and goal relaxation. May reach a state that might be a little worse that the ultimate objective Example – Multi-agent Tile world (like airport shuttle) – isn’t just a specific state, but the value of work accomplished 89

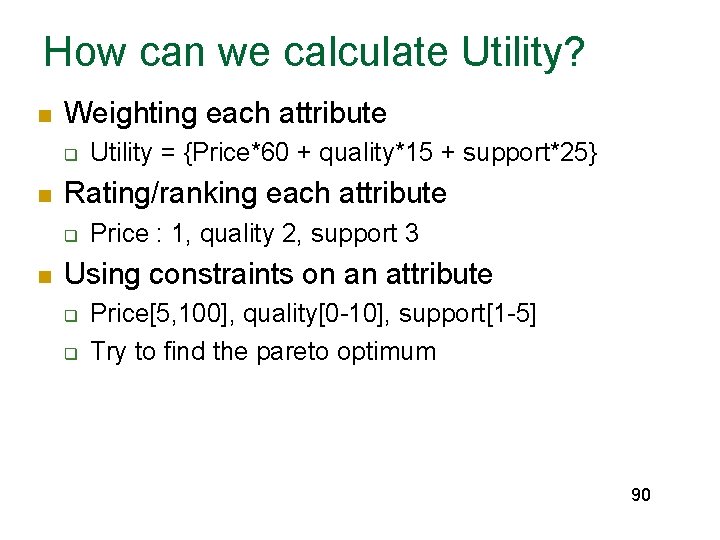

How can we calculate Utility? n Weighting each attribute q n Rating/ranking each attribute q n Utility = {Price*60 + quality*15 + support*25} Price : 1, quality 2, support 3 Using constraints on an attribute q q Price[5, 100], quality[0 -10], support[1 -5] Try to find the pareto optimum 90

What if choices don’t benefit others fairly? n Suppose there are two states that satisfy both n n n agents. State 1: one has a utility of 6 for one agent and 3 for the other. State 2: utility of both agents 4. State 1 is better (overall), but state 2 is more equal. How can we get cooperation (as why should one agent agree to do more)? 91

The Monotonic Concession Protocol –move towards middle Rules of this protocol are as follows. . . n Negotiation proceeds in rounds. n On round 1, agents simultaneously propose a deal from the negotiation set Can re-propose same deal. n Agreement is reached if one agent finds that the deal proposed by the other is at least as good or better than its proposal. n If no agreement is reached, then negotiation proceeds to another round of simultaneous proposals. n An agent is not allowed to offer the other agent less (in term of utility ) than it did in the previous round. It can either stand still or make a concession. Assumes we know what the other agent values. n If neither agent makes a concession in some round, then negotiation terminates, with the conflict deal. n Meta data may be present: explanation or critique of deal. 92

Condition to Consent to an Agreement If both of the agents finds that the deal proposed by the other is at least as good or better than the proposal it made – randomly pick one. Utility 1( 2) Utility 1( 1) and Utility 2( 1) Utility 2( 2) 93

The Monotonic Concession Protocol Advantages: n q Symmetrically distributed (no agent plays a special role or gets to go first) q Ensures convergence - It will not go on indefinitely Disadvantages: n q Can result in conflict deal – when a better solution is possible q Inefficient – no quarantee that an agreement will be reached quickly 94

The Zeuthen Strategy – a refinement of monotonic protocol Q: What should my first proposal be? A: the best deal for you among all possible deals in the negotiation set. (Is a way of telling others what you value. ) Agent 1's best deal agent 2's best deal 95

The Zeuthen Strategy Q: Who should compromise? A: The one who has the most to lose by a conflict deal Agent 1 has more to lose As he’s already gained agent 2 has less to lose from conflict 96

Example of Zeuthan n n In interviewing for Women’s center director, the candidate we were most interested in was approached. She started by asking for q q $10 K more money Job for husband Tenured full professor in academic department Gold parking pass for terrace 97

What was her strategy? n n n Clearly Zeuthan Advantages: she had something to concede and we knew what she valued Disadvantage: could be thought of as too much so that the committee removes her from the pool. Have had students make “initial request” that backfired as seemed totally off-base. If you realize someone is using this strategy, you might NOT be offended. 98

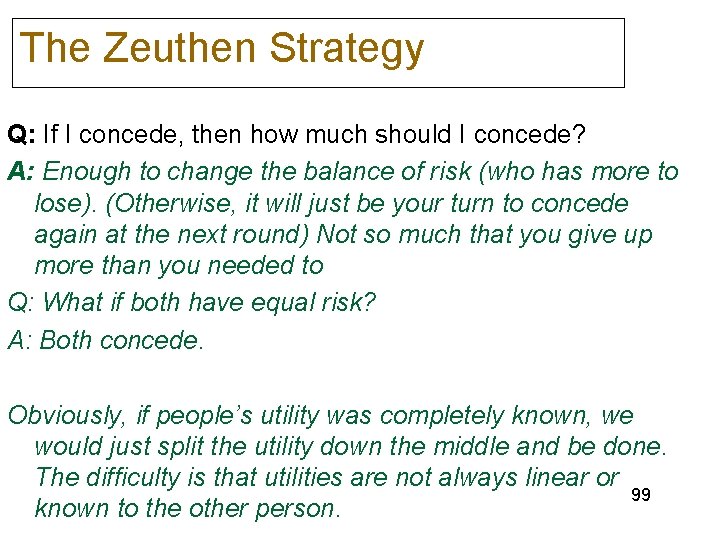

The Zeuthen Strategy Q: If I concede, then how much should I concede? A: Enough to change the balance of risk (who has more to lose). (Otherwise, it will just be your turn to concede again at the next round) Not so much that you give up more than you needed to Q: What if both have equal risk? A: Both concede. Obviously, if people’s utility was completely known, we would just split the utility down the middle and be done. The difficulty is that utilities are not always linear or 99 known to the other person.

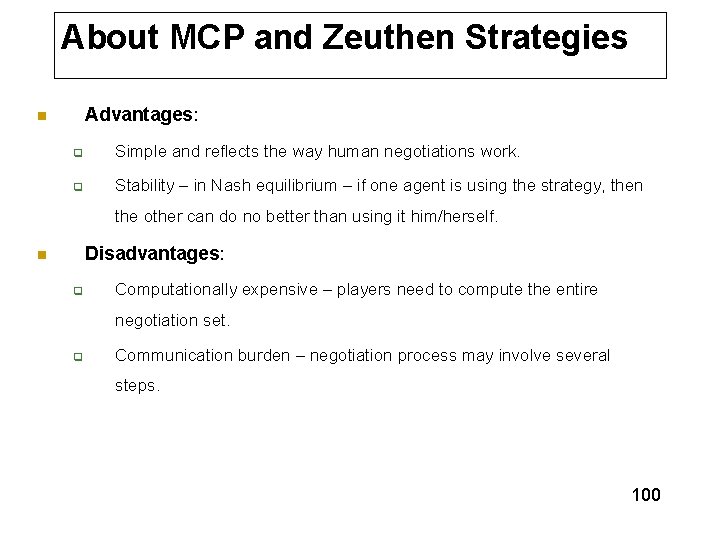

About MCP and Zeuthen Strategies Advantages: n q Simple and reflects the way human negotiations work. q Stability – in Nash equilibrium – if one agent is using the strategy, then the other can do no better than using it him/herself. Disadvantages: n q Computationally expensive – players need to compute the entire negotiation set. q Communication burden – negotiation process may involve several steps. 100

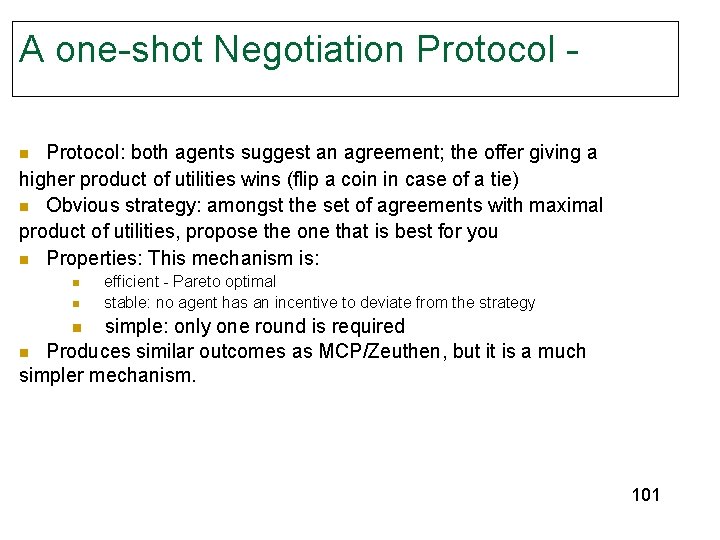

A one-shot Negotiation Protocol - Protocol: both agents suggest an agreement; the offer giving a higher product of utilities wins (flip a coin in case of a tie) n Obvious strategy: amongst the set of agreements with maximal product of utilities, propose the one that is best for you n Properties: This mechanism is: n n n efficient - Pareto optimal stable: no agent has an incentive to deviate from the strategy simple: only one round is required n Produces similar outcomes as MCP/Zeuthen, but it is a much simpler mechanism. n 101

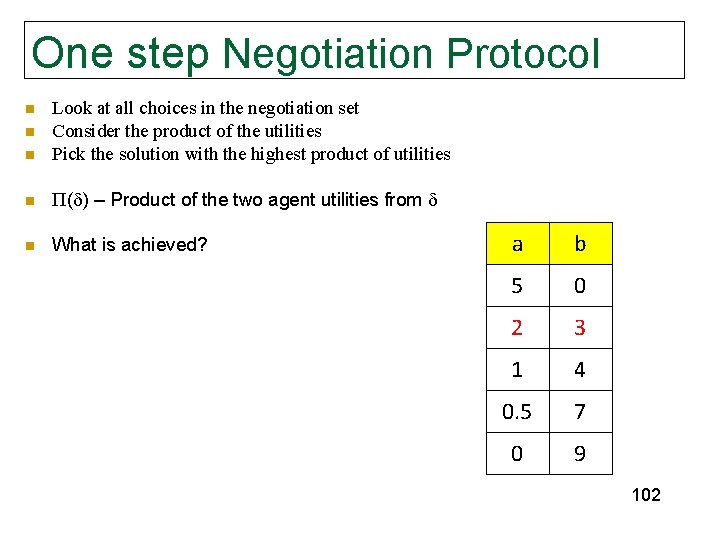

One step Negotiation Protocol n Look at all choices in the negotiation set Consider the product of the utilities Pick the solution with the highest product of utilities n P( ) – Product of the two agent utilities from n What is achieved? n n a b 5 0 2 3 1 4 0. 5 7 0 9 102

- Slides: 101