Chapter 14 Regulation of Genome Activity 1 Transient

- Slides: 54

Chapter 14 Regulation of Genome Activity 1. Transient Changes in Genome Activity 2. Permanent and Semipermanent Changes in Genome Activity 3. Regulation of Genome Activity During Development

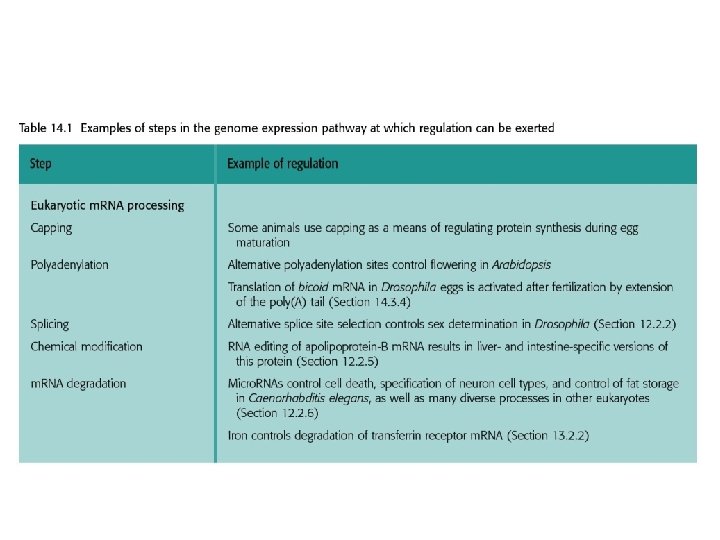

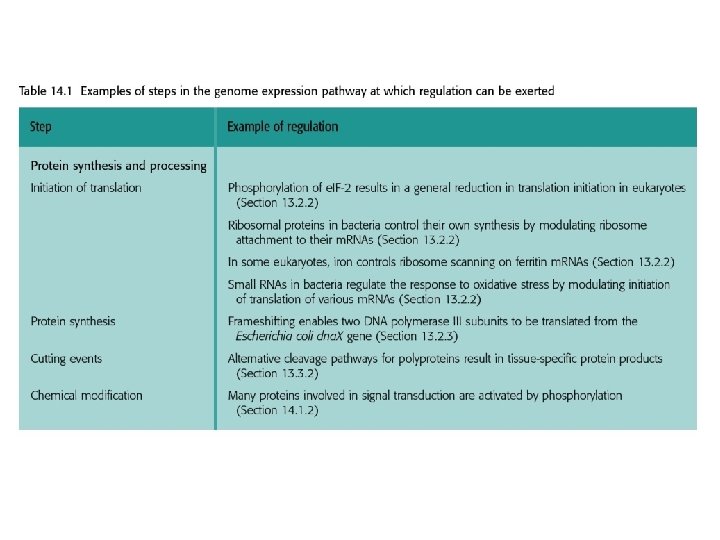

How the activity of the genome as a whole is regulated. • Differentiation not only in multicellular organisms. • Human has over 250 types of specialized cells.

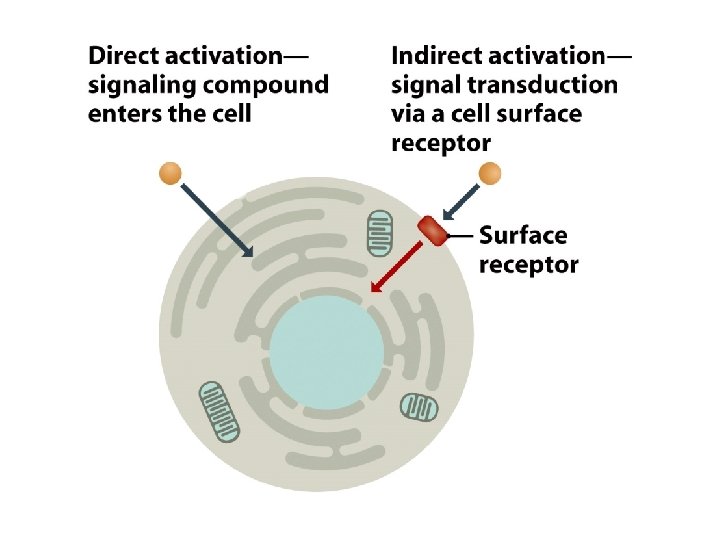

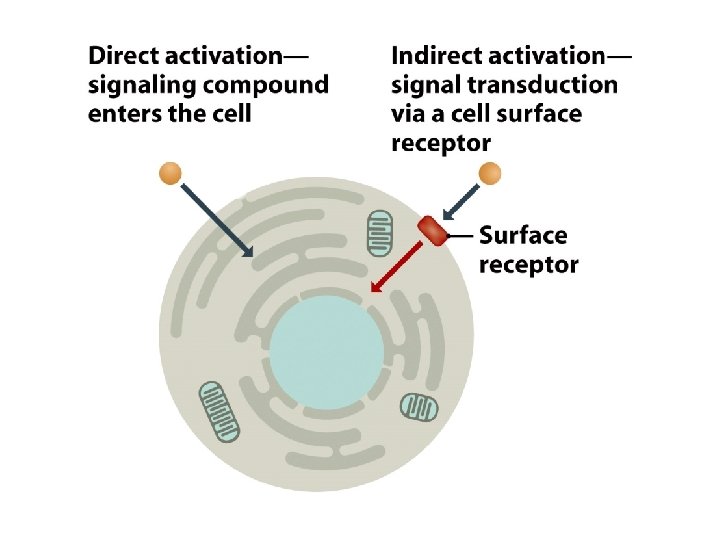

14. 1 Transient Changes in Genome Activity • Most cells in multicellular organisms live in less variable environments, but the maintenance of this environment requires coordination between the activities of different cells. • To exert an effect on genome activity, the nutrient, hormone, growth factor, or other extracellular compound that represents the external stimulus must influence events within the cell.

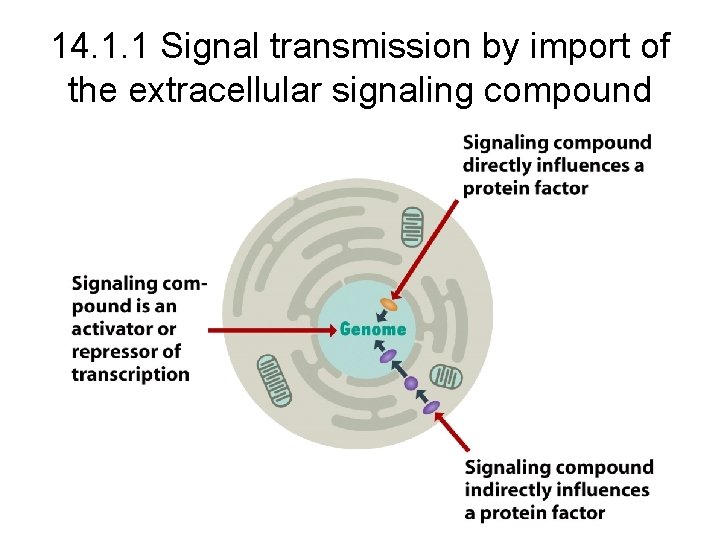

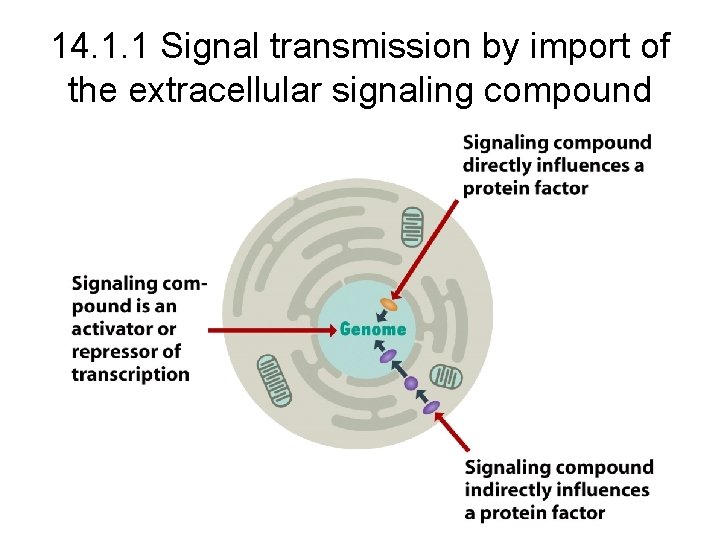

14. 1. 1 Signal transmission by import of the extracellular signaling compound

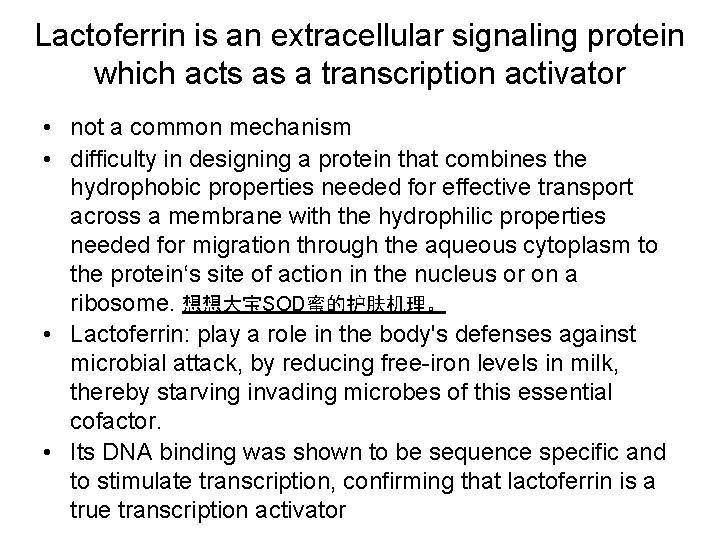

Lactoferrin is an extracellular signaling protein which acts as a transcription activator • not a common mechanism • difficulty in designing a protein that combines the hydrophobic properties needed for effective transport across a membrane with the hydrophilic properties needed for migration through the aqueous cytoplasm to the protein‘s site of action in the nucleus or on a ribosome. 想想大宝SOD蜜的护肤机理。 • Lactoferrin: play a role in the body's defenses against microbial attack, by reducing free-iron levels in milk, thereby starving invading microbes of this essential cofactor. • Its DNA binding was shown to be sequence specific and to stimulate transcription, confirming that lactoferrin is a true transcription activator

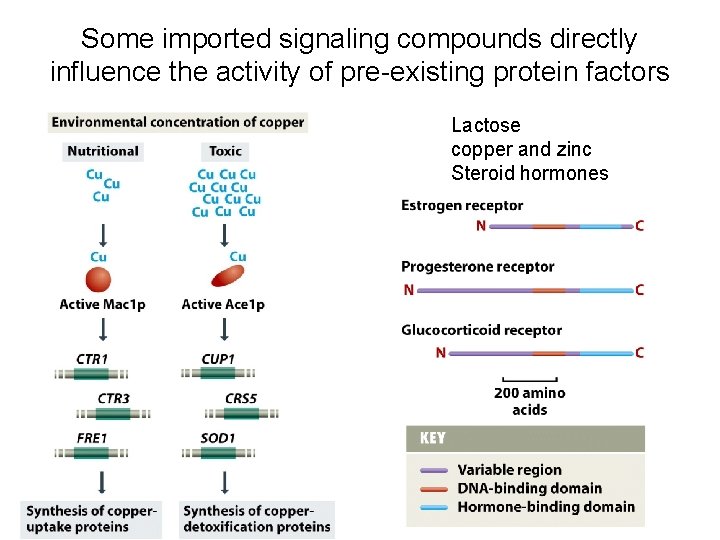

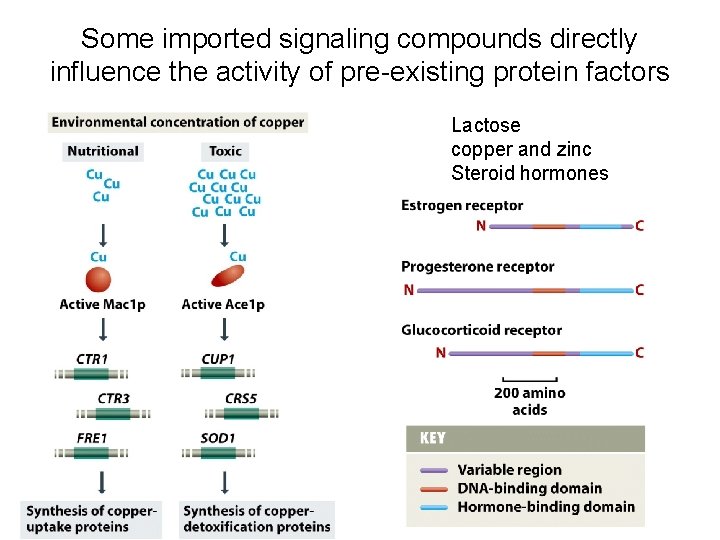

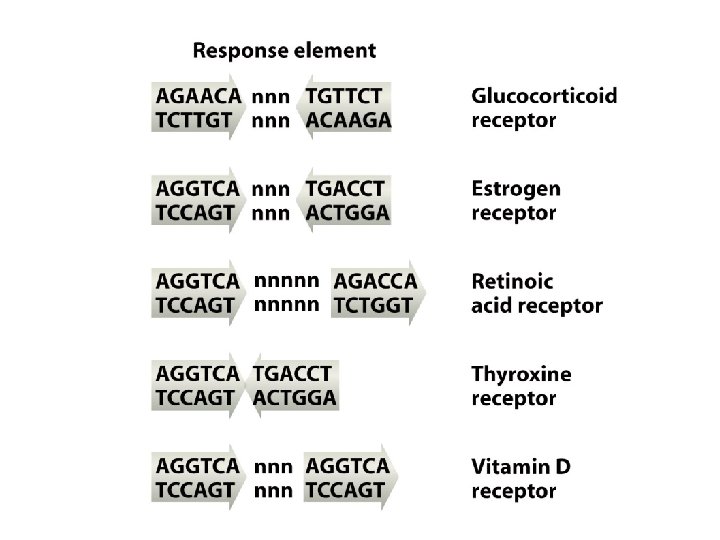

Some imported signaling compounds directly influence the activity of pre-existing protein factors Lactose copper and zinc Steroid hormones

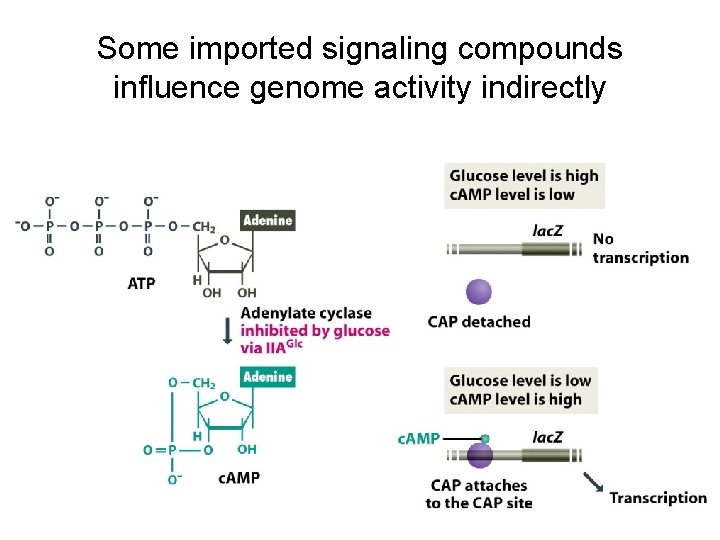

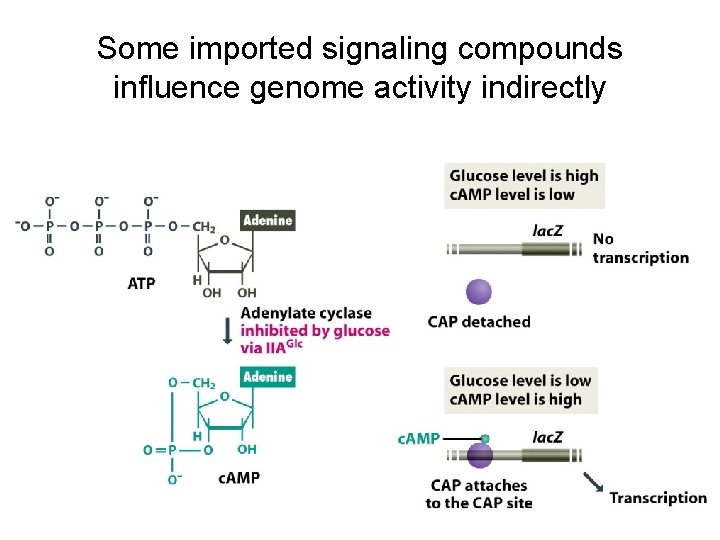

Some imported signaling compounds influence genome activity indirectly

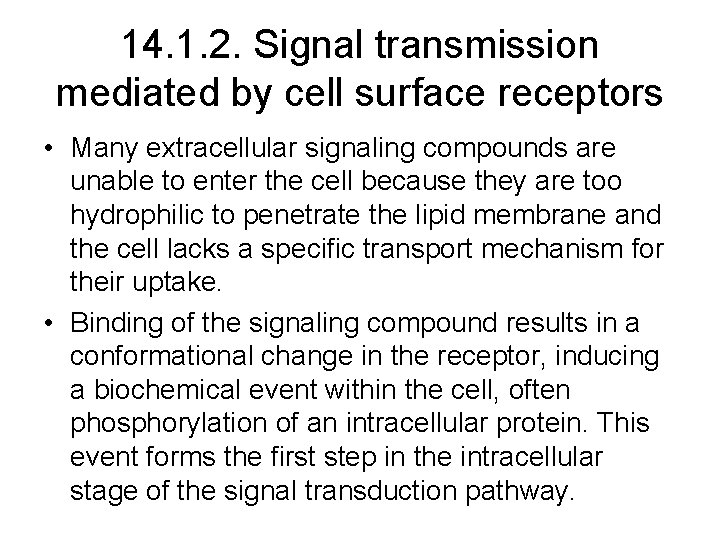

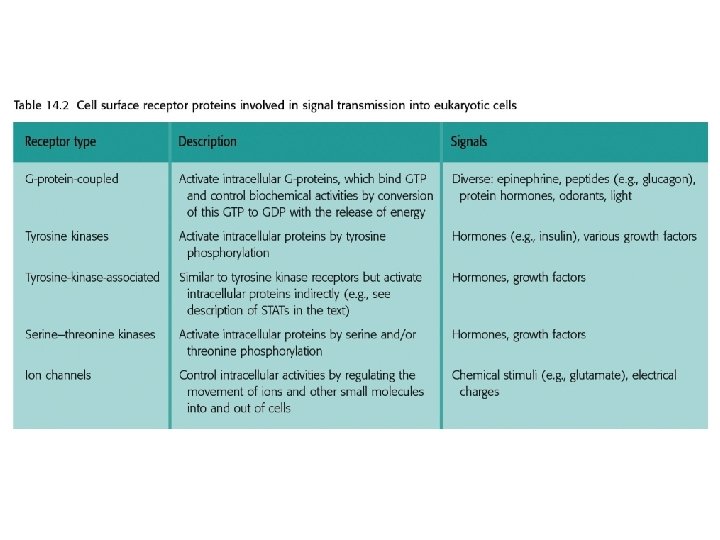

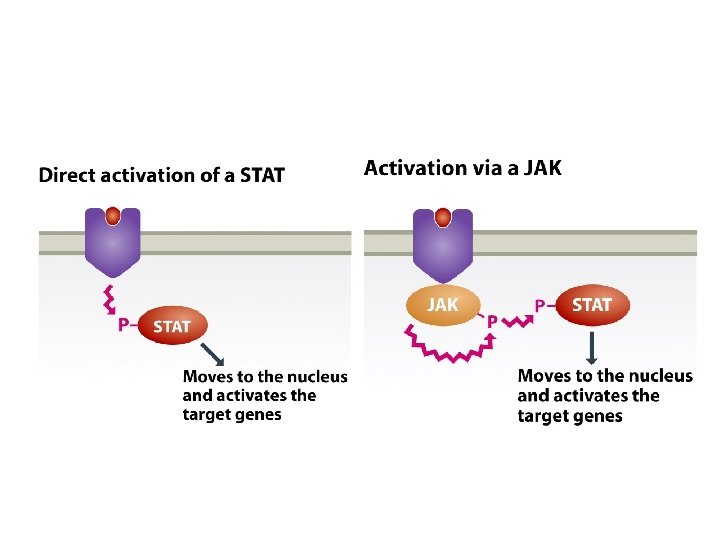

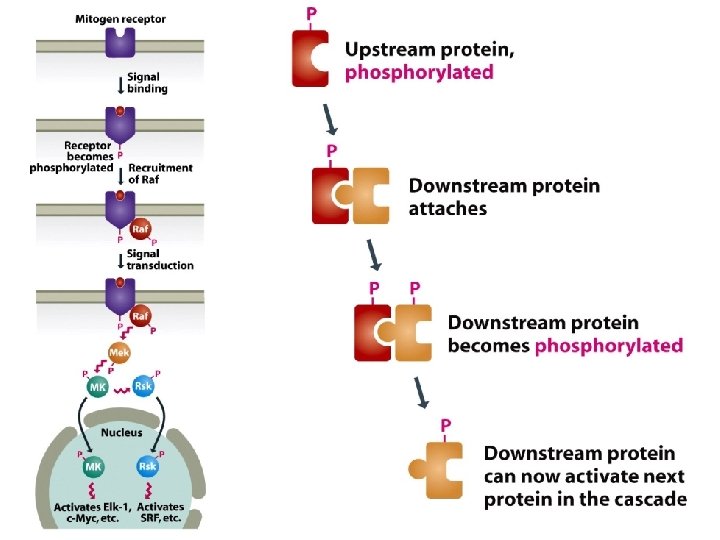

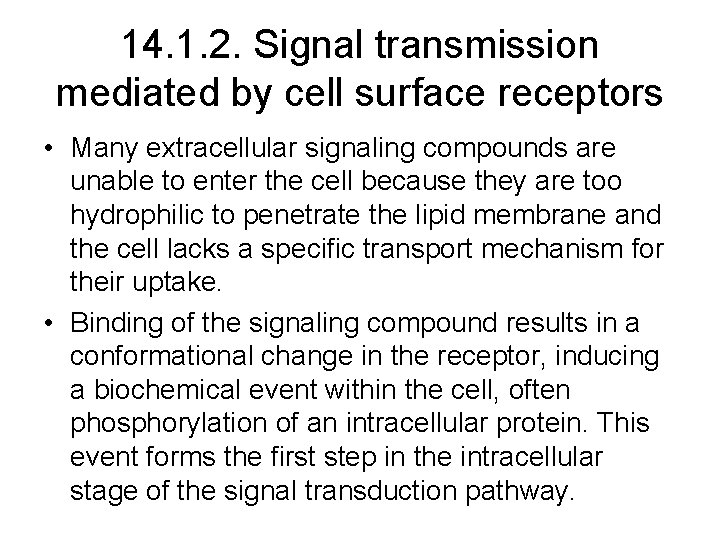

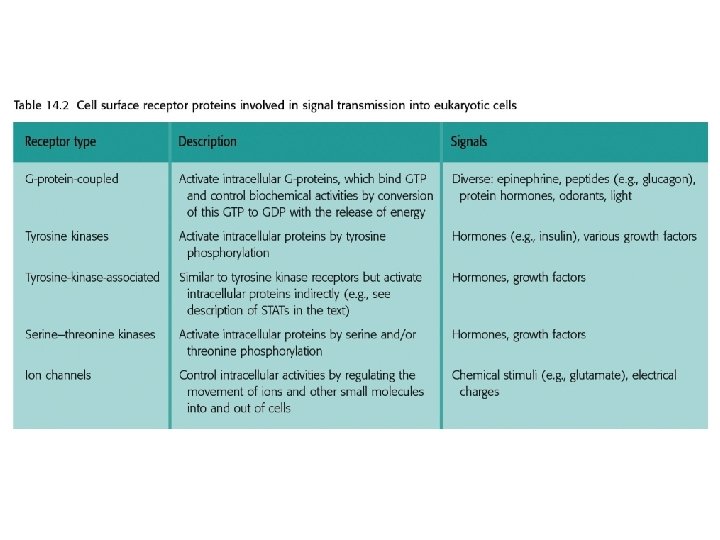

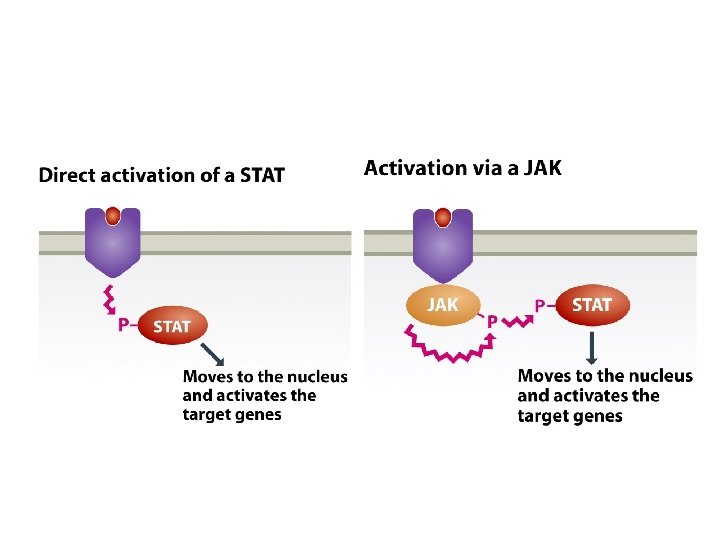

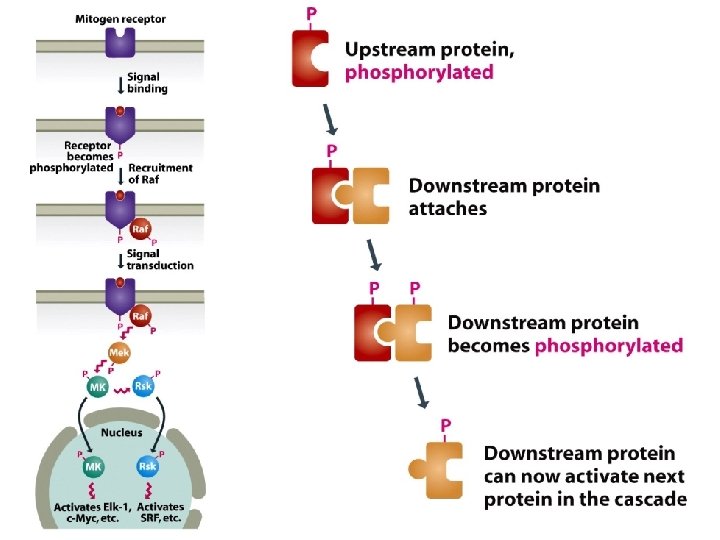

14. 1. 2. Signal transmission mediated by cell surface receptors • Many extracellular signaling compounds are unable to enter the cell because they are too hydrophilic to penetrate the lipid membrane and the cell lacks a specific transport mechanism for their uptake. • Binding of the signaling compound results in a conformational change in the receptor, inducing a biochemical event within the cell, often phosphorylation of an intracellular protein. This event forms the first step in the intracellular stage of the signal transduction pathway.

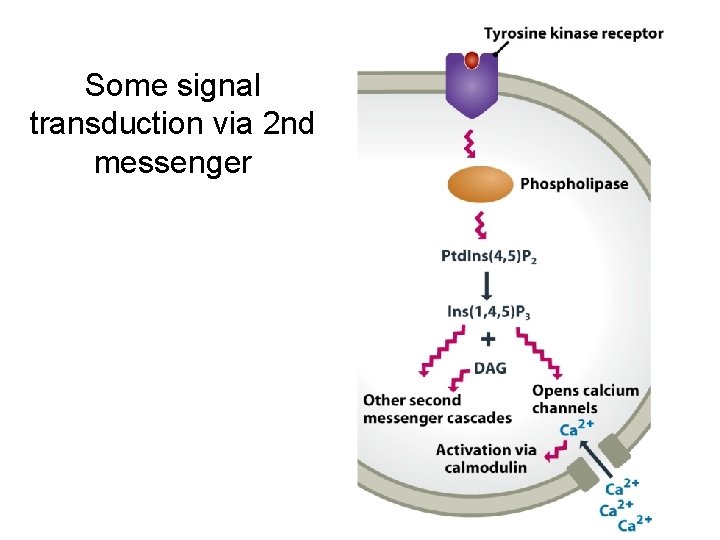

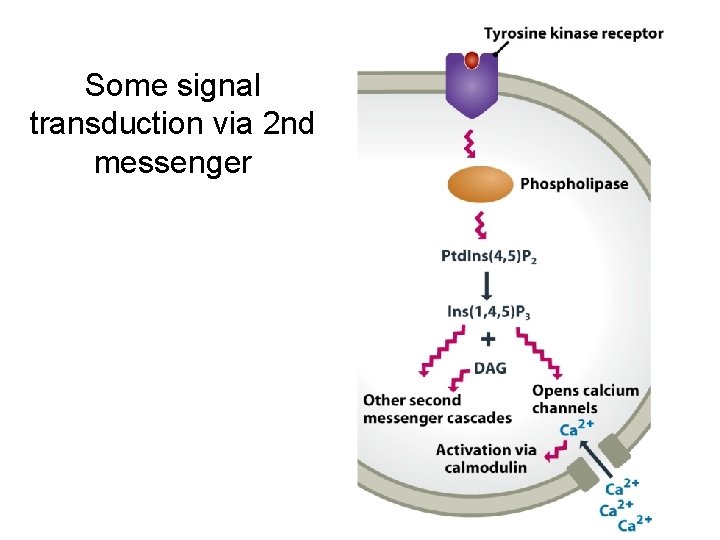

Some signal transduction via 2 nd messenger

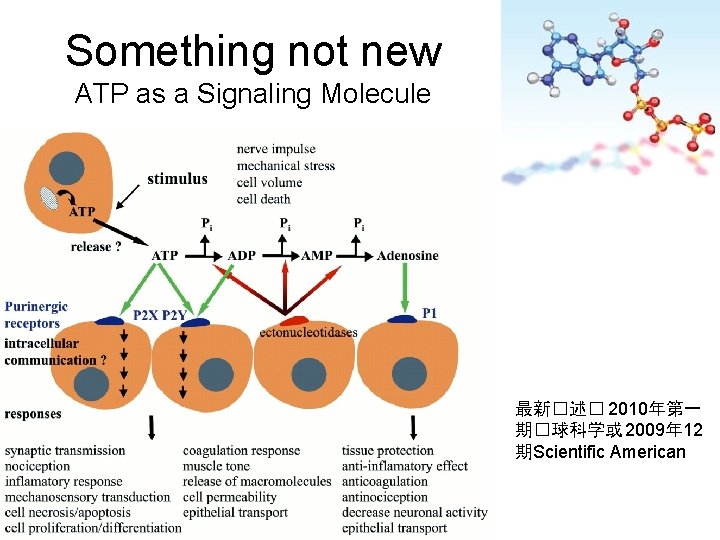

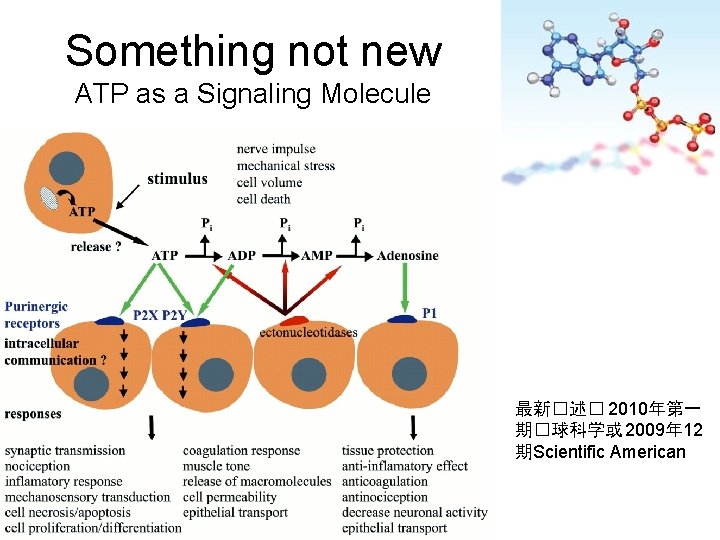

Something not new ATP as a Signaling Molecule 最新�述� 2010年第一 期�球科学或 2009年 12 期Scientific American

1. Transient Changes in Genome Activity 2. Permanent and Semipermanent Changes in Genome Activity 3. Regulation of Genome Activity During Development

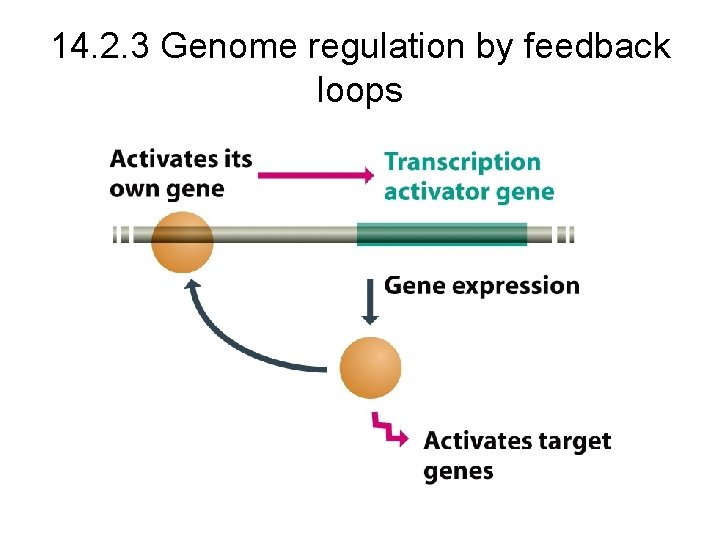

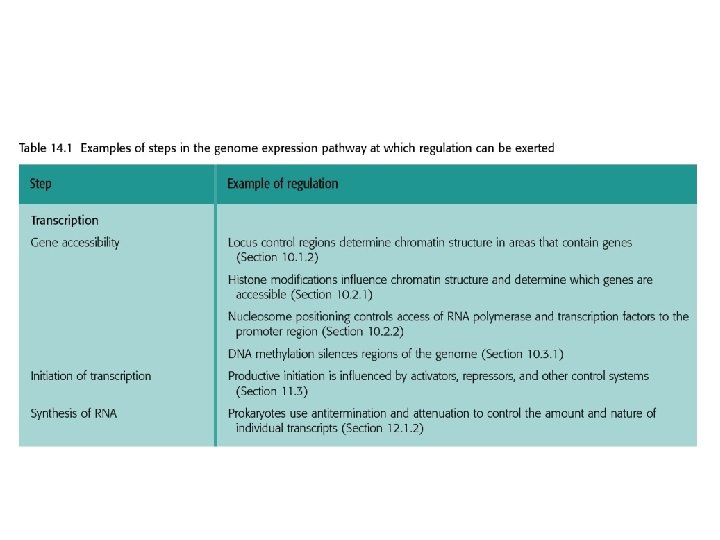

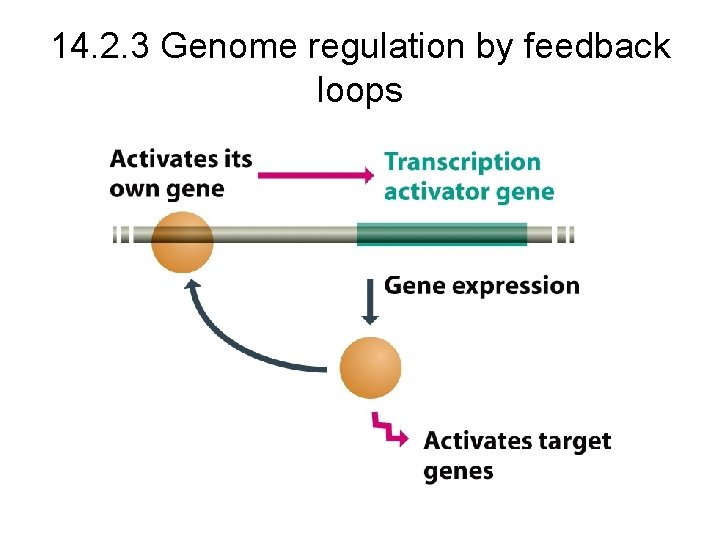

14. 2 Permanent and Semipermanent Changes in Genome Activity • Transient changes in genome activity are, by definition, readily reversible, the gene expression pattern reverting to its original state when the external stimulus is removed or replaced by a contradictory stimulus. • In contrast, the permanent and semipermanent changes in genome activity that underlie cellular differentiation must persist for long periods, and ideally should be maintained even when the stimulus that originally induced them has disappeared. Three mechanisms: 1. Changes resulting from physical rearrangement of the genome; 2. Changes due to chromatin structure; 3. Changes maintained by feedback loops.

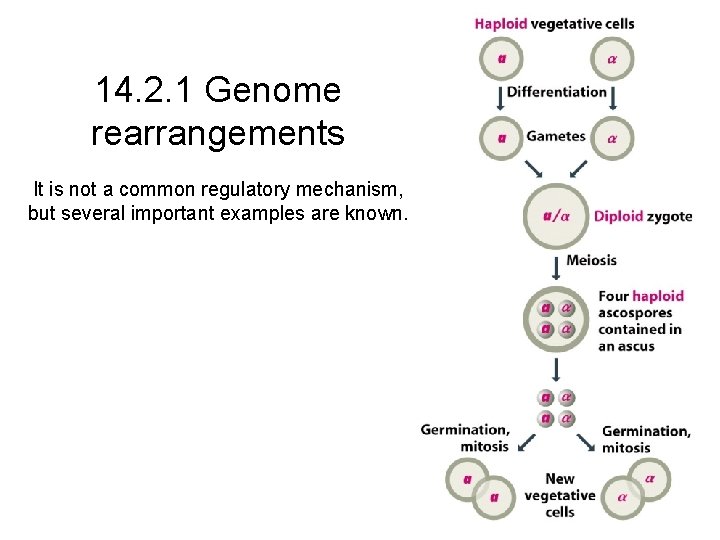

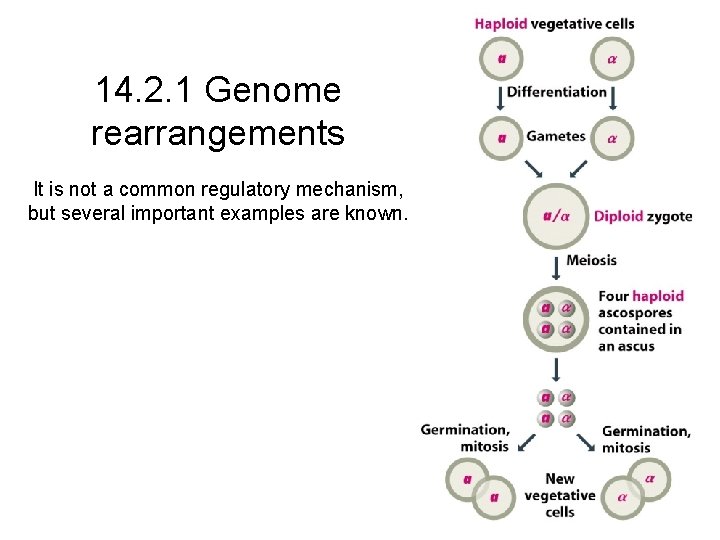

14. 2. 1 Genome rearrangements It is not a common regulatory mechanism, but several important examples are known.

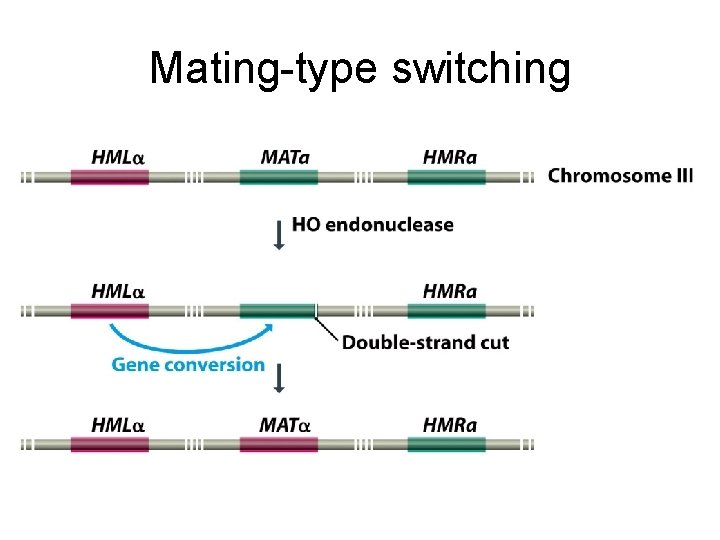

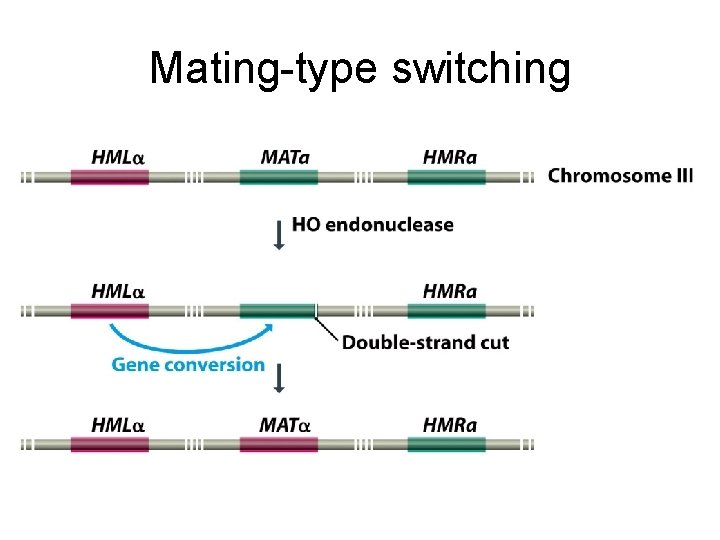

Mating-type switching

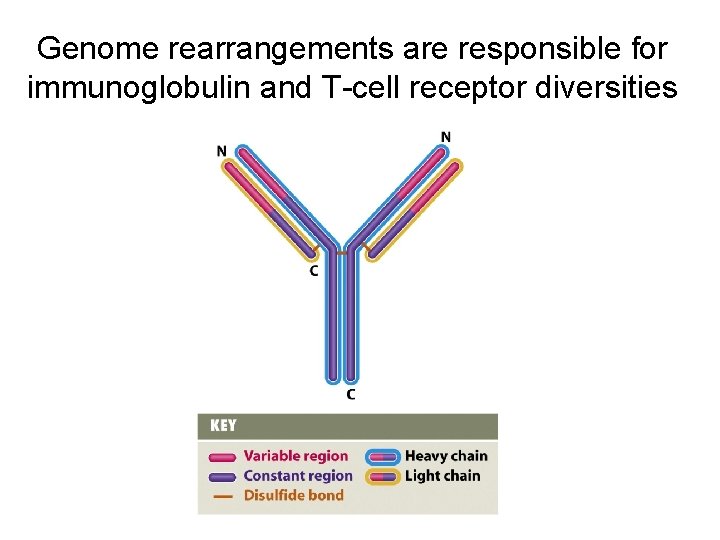

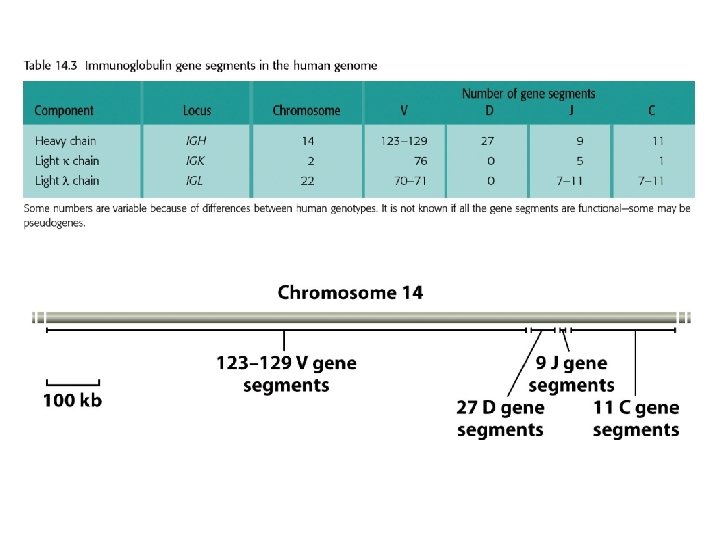

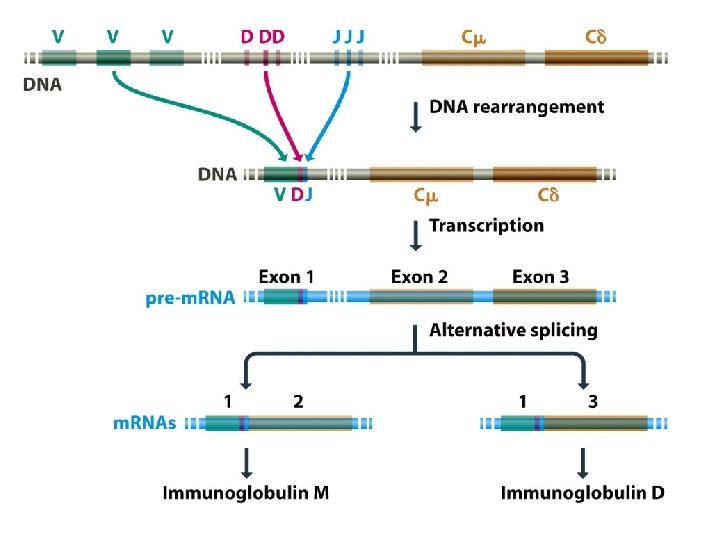

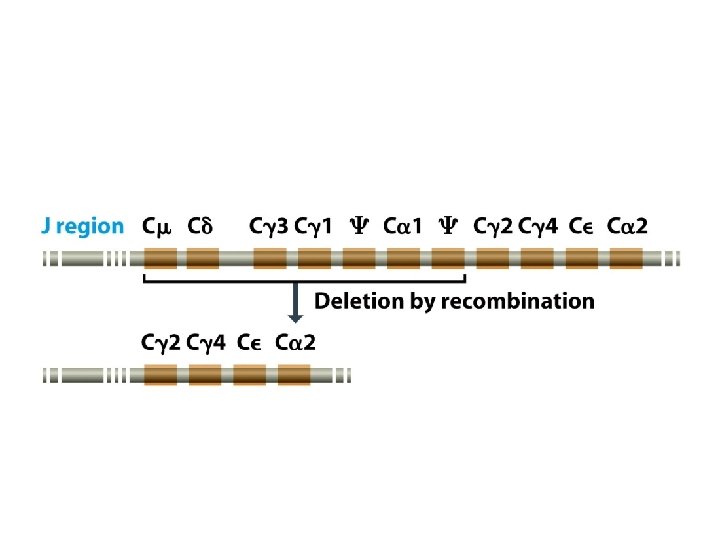

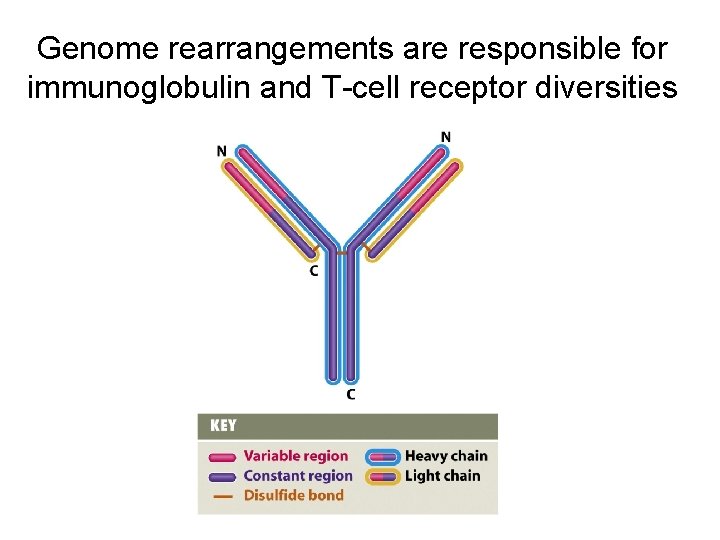

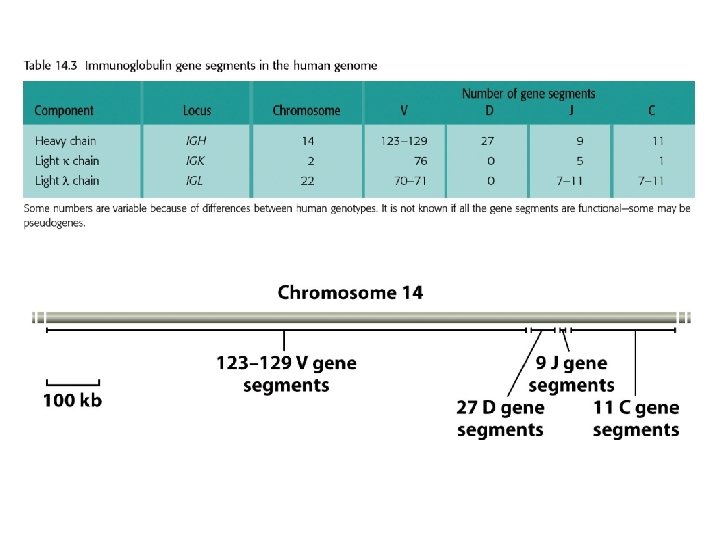

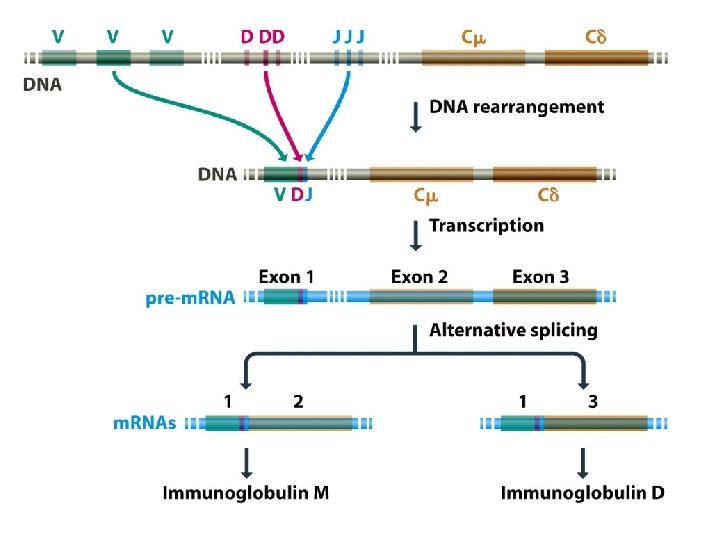

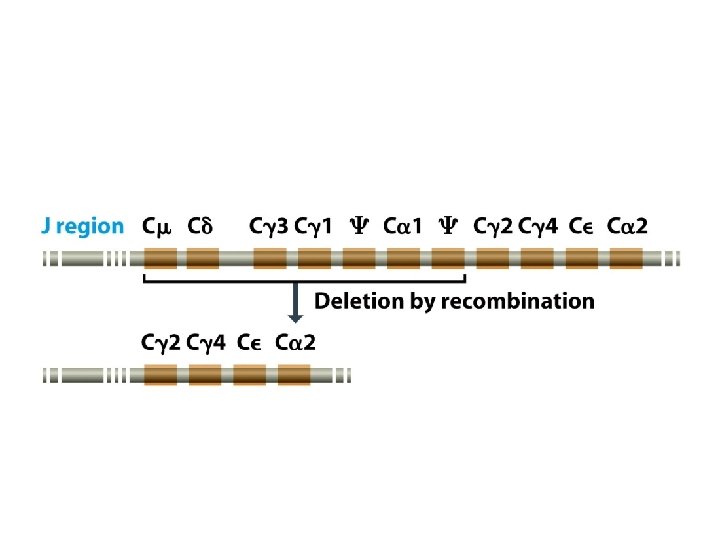

Genome rearrangements are responsible for immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor diversities

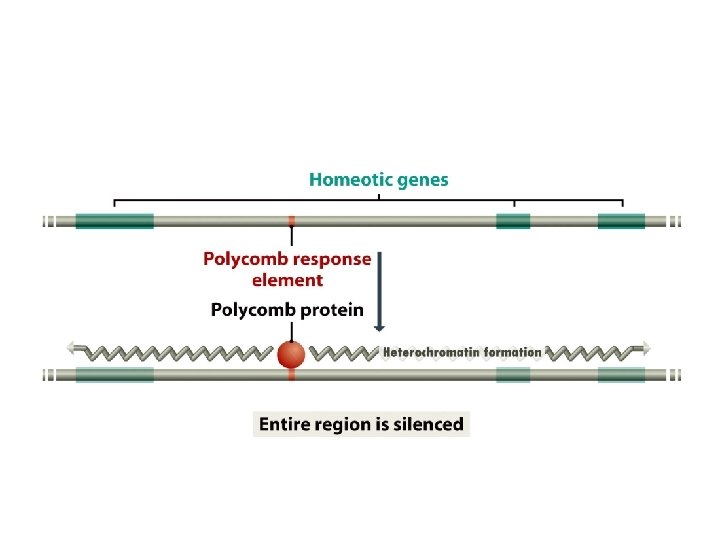

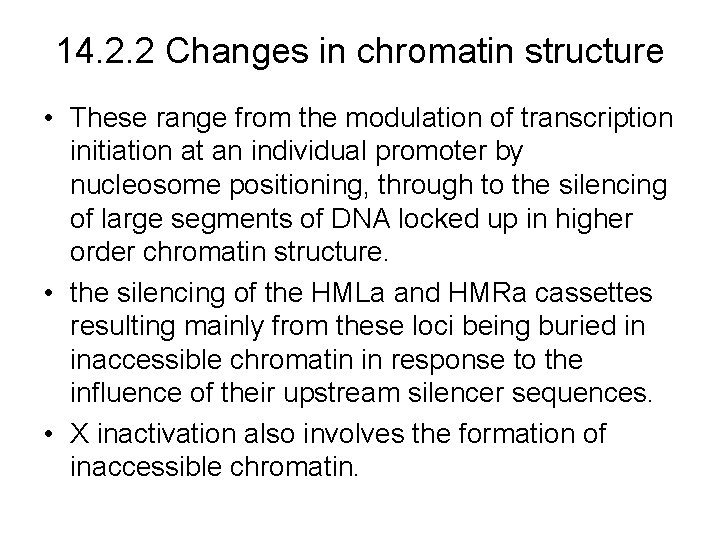

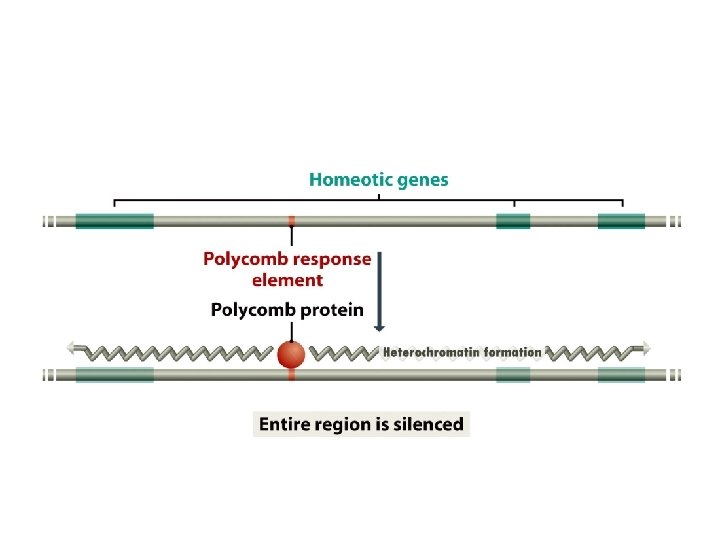

14. 2. 2 Changes in chromatin structure • These range from the modulation of transcription initiation at an individual promoter by nucleosome positioning, through to the silencing of large segments of DNA locked up in higher order chromatin structure. • the silencing of the HMLa and HMRa cassettes resulting mainly from these loci being buried in inaccessible chromatin in response to the influence of their upstream silencer sequences. • X inactivation also involves the formation of inaccessible chromatin.

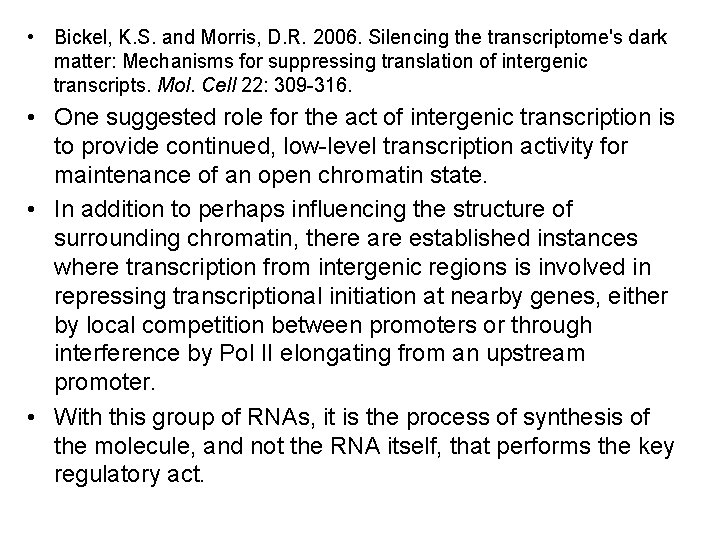

• Bickel, K. S. and Morris, D. R. 2006. Silencing the transcriptome's dark matter: Mechanisms for suppressing translation of intergenic transcripts. Mol. Cell 22: 309 -316. • One suggested role for the act of intergenic transcription is to provide continued, low-level transcription activity for maintenance of an open chromatin state. • In addition to perhaps influencing the structure of surrounding chromatin, there are established instances where transcription from intergenic regions is involved in repressing transcriptional initiation at nearby genes, either by local competition between promoters or through interference by Pol II elongating from an upstream promoter. • With this group of RNAs, it is the process of synthesis of the molecule, and not the RNA itself, that performs the key regulatory act.

14. 2. 3 Genome regulation by feedback loops

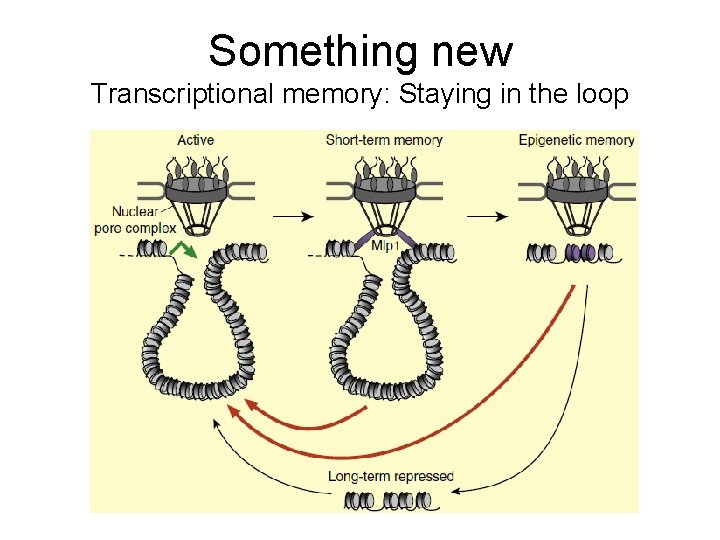

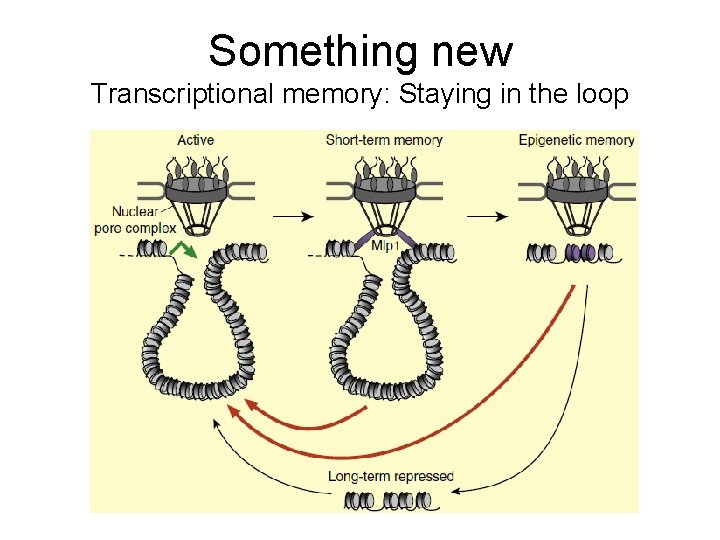

Something new Transcriptional memory: Staying in the loop

Transcriptional memory: Staying in the loop. Do you see some implications from these findings? • Philippe, J. -P. , Singh, B. N. , Krishnamurthy, S. , and Hampsey, M. (2009). A physiologcal role for gene loops in yeast. Genes Dev. 23, 2604– 2609. • Tan-Wong, S. M. , Wijayatilake, H. D. , and Proudfoot, N. (2009). Gene loops function to maintain transcriptional memory through interaction with the nuclear pore complex. Genes Dev. 23, 2610– 2624. • Bricker, J. H. (2010). Transcriptional memory: Staying in the loop. Curr Biol. 20, R 20 -R 21.

1. Transient Changes in Genome Activity 2. Permanent and Semipermanent Changes in Genome Activity 3. Regulation of Genome Activity During Development

14. 3 Regulation of Genome Activity During Development • The developmental pathway of a multicellular eukaryote begins with a fertilized egg cell and ends with an adult form of the organism. • With humans, this developmental pathway results in an adult containing 1013 cells differentiated into approximately 250 specialized types.

14. 3. 1 Sporulation in Bacillus • Strictly speaking, this is not a developmental pathway, merely a type of cellular differentiation, but the process illustrates two of the fundamental issues that have to be addressed when genuine development in multicellular organisms is studied. These issues are how a series of changes in genome activity over time is controlled, and how signaling establishes coordination between events occurring in different cells. • As a model system, Bacillus subtilis is easy to grow in the laboratory and is amenable to study by genetic and molecular techniques. • The later is very important, but unfortunately, not common used in China.

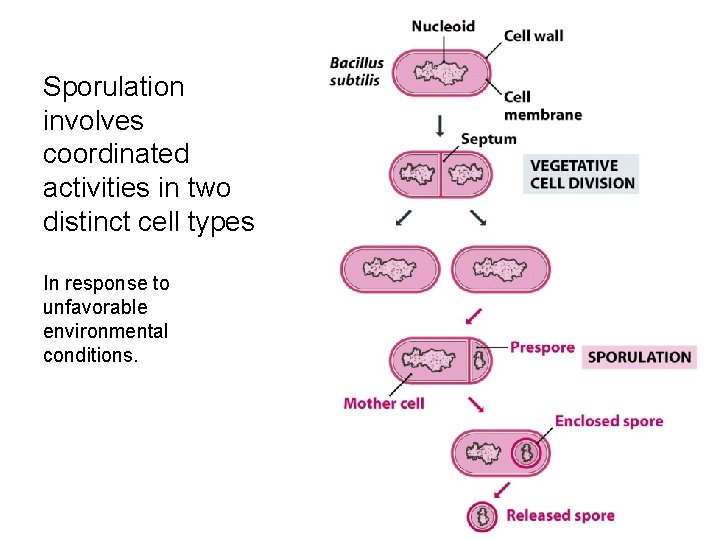

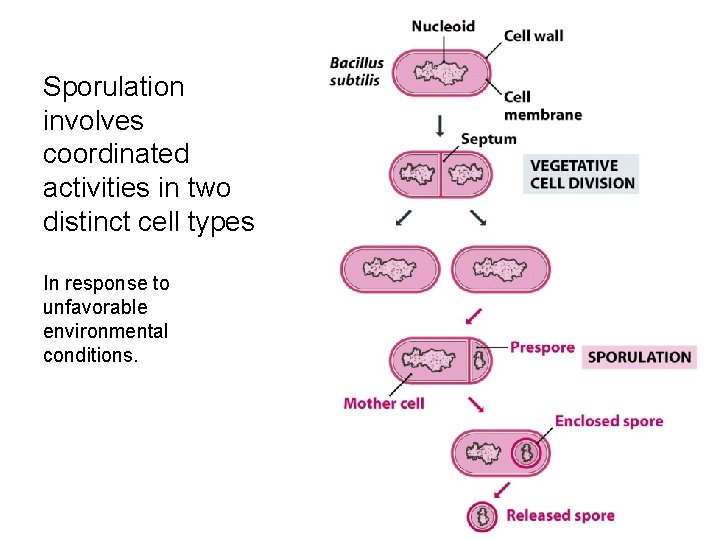

Sporulation involves coordinated activities in two distinct cell types In response to unfavorable environmental conditions.

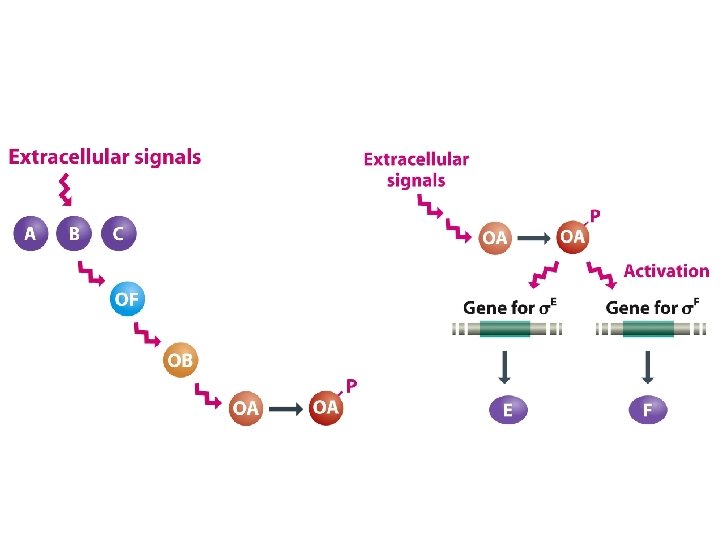

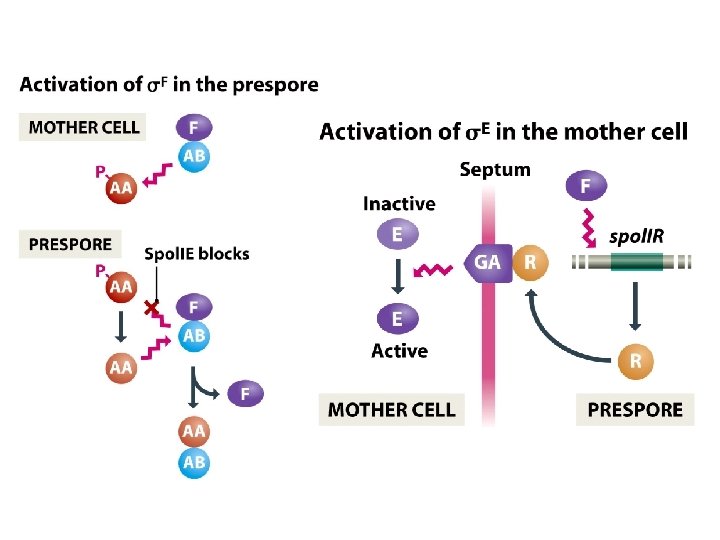

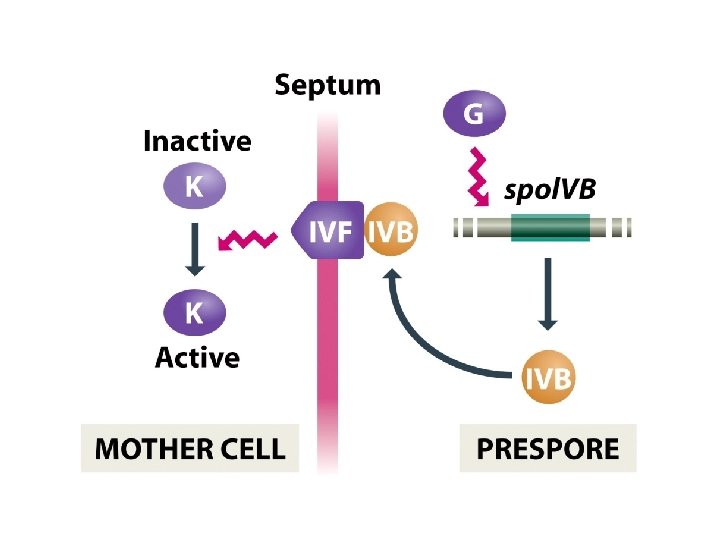

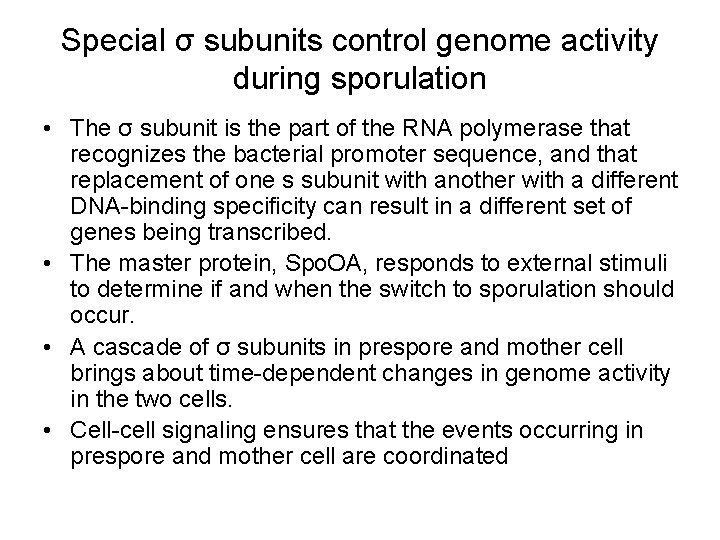

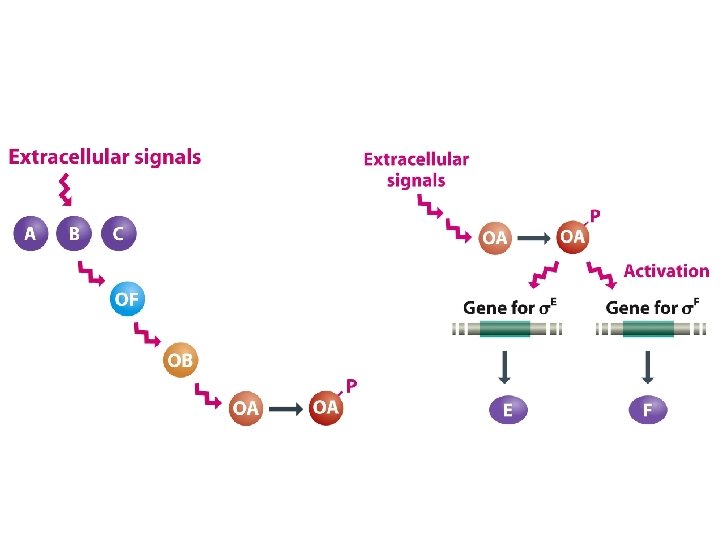

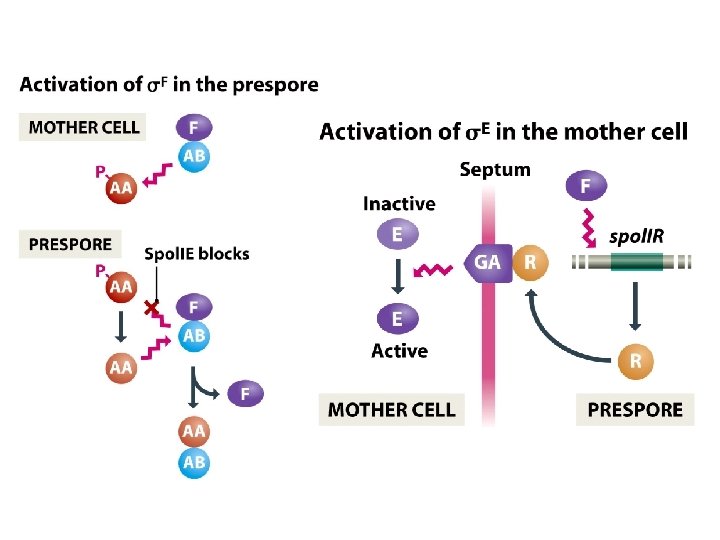

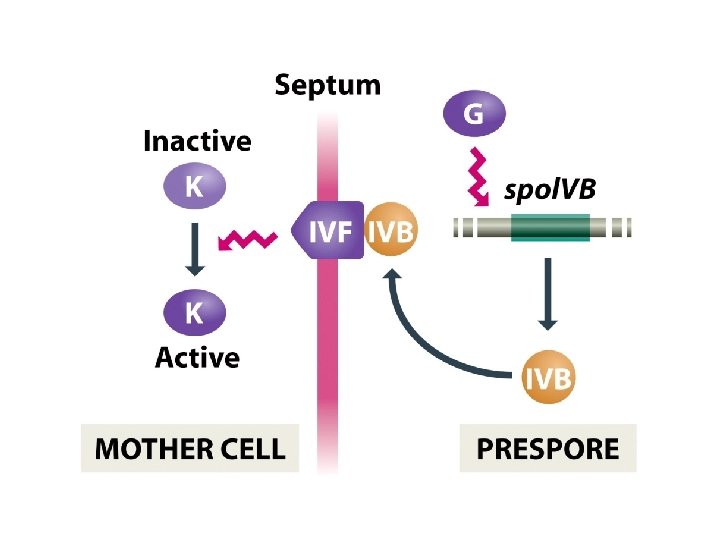

Special σ subunits control genome activity during sporulation • The σ subunit is the part of the RNA polymerase that recognizes the bacterial promoter sequence, and that replacement of one s subunit with another with a different DNA-binding specificity can result in a different set of genes being transcribed. • The master protein, Spo. OA, responds to external stimuli to determine if and when the switch to sporulation should occur. • A cascade of σ subunits in prespore and mother cell brings about time-dependent changes in genome activity in the two cells. • Cell-cell signaling ensures that the events occurring in prespore and mother cell are coordinated

14. 3. 2 Vulva development in Caenorhabditis elegans • C. elegans is easy to grow in the laboratory and has a short generation time, measured in days but still convenient for genetic analysis. The worm is transparent at all stages of its life cycle, so internal examination is possible without killing the animal. This is an important point because it has enabled researchers to follow the entire developmental process of the worm at the cellular level. Every cell division in the pathway from fertilized egg to adult worm has been charted, and every point at which a cell adopts a specialized role has been identified. In addition, the complete connectivity of the 302 cells that comprise the nervous system of the worm has been mapped.

• In a multicellular organism, positional information is important: the correct structure must develop at the appropriate place. • The commitment to differentiation of a small number of progenitor cells can lead to construction of a multicellular structure. • Cell-cell signaling can utilize a concentration gradient to induce different responses in cells at different positions relative to the signaling cell. • A cell might be subject to competitive signaling, where one signal tells it to do one thing and a second signal tells it to do the opposite.

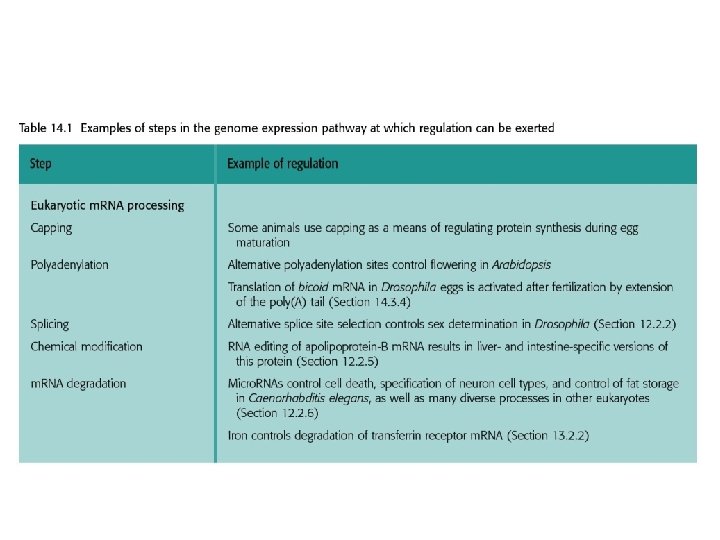

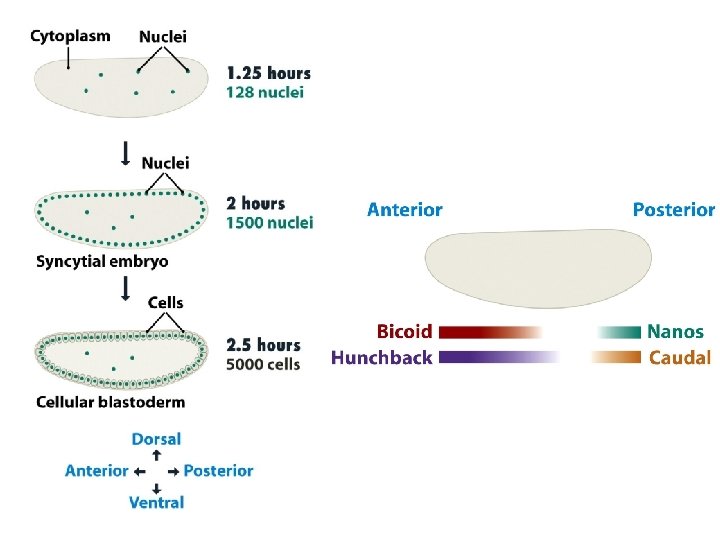

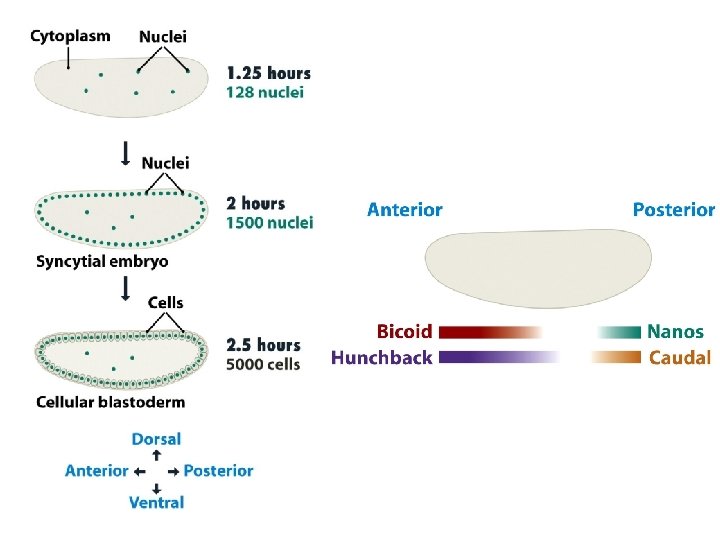

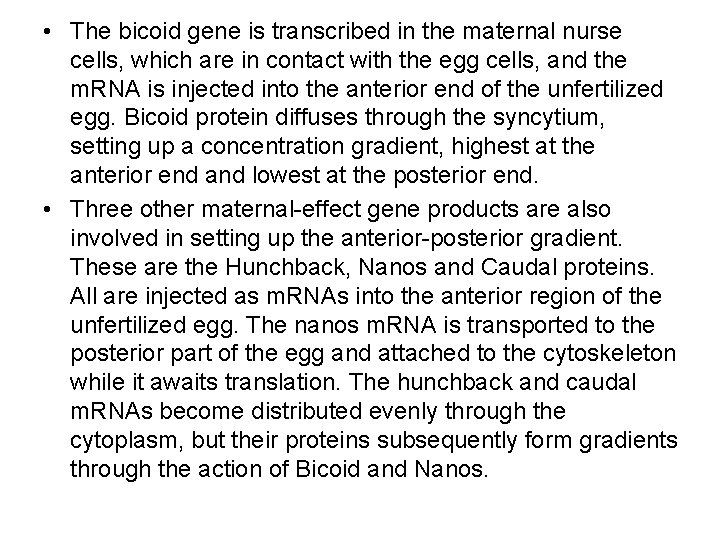

14. 3. 3 Development in Drosophila melanogaster • Initially the positional information that the embryo needs is a definition of which end is the front (anterior) and which the back (posterior), as well as similar information relating to up (dorsal) and down (ventral). This information is provided by concentration gradients of proteins that become established in the syncytium. The bulk of these proteins are not synthesized from genes in the embryo, but are translated from m. RNAs injected into the embryo by the mother.

• The bicoid gene is transcribed in the maternal nurse cells, which are in contact with the egg cells, and the m. RNA is injected into the anterior end of the unfertilized egg. Bicoid protein diffuses through the syncytium, setting up a concentration gradient, highest at the anterior end and lowest at the posterior end. • Three other maternal-effect gene products are also involved in setting up the anterior-posterior gradient. These are the Hunchback, Nanos and Caudal proteins. All are injected as m. RNAs into the anterior region of the unfertilized egg. The nanos m. RNA is transported to the posterior part of the egg and attached to the cytoskeleton while it awaits translation. The hunchback and caudal m. RNAs become distributed evenly through the cytoplasm, but their proteins subsequently form gradients through the action of Bicoid and Nanos.

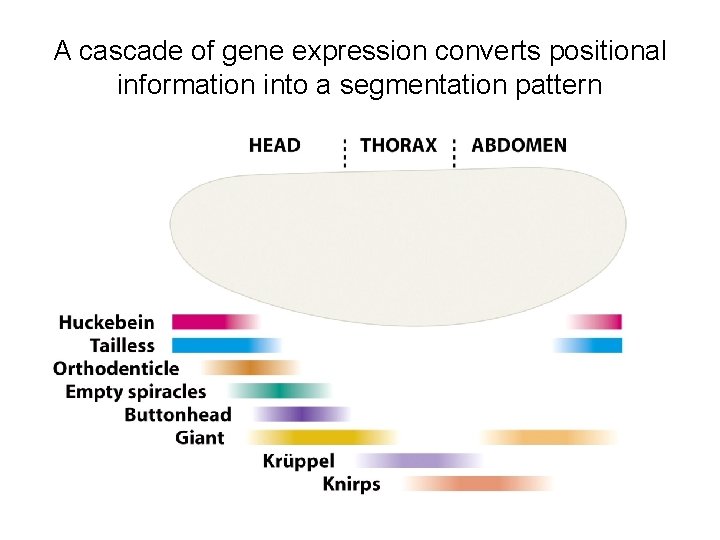

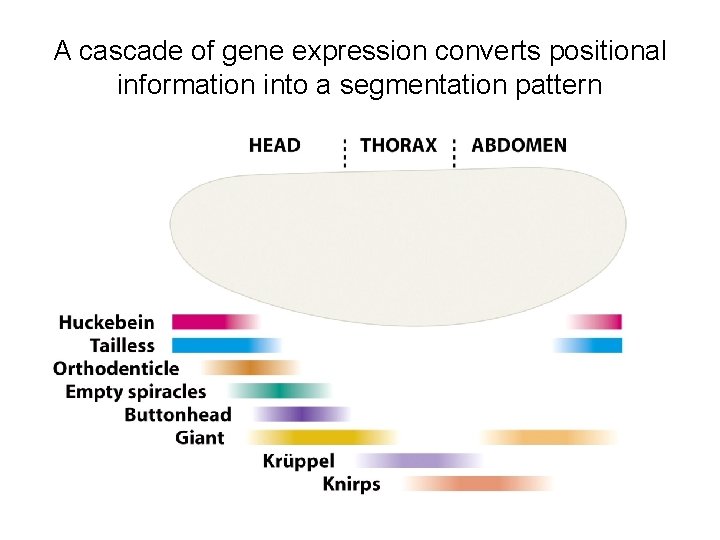

A cascade of gene expression converts positional information into a segmentation pattern

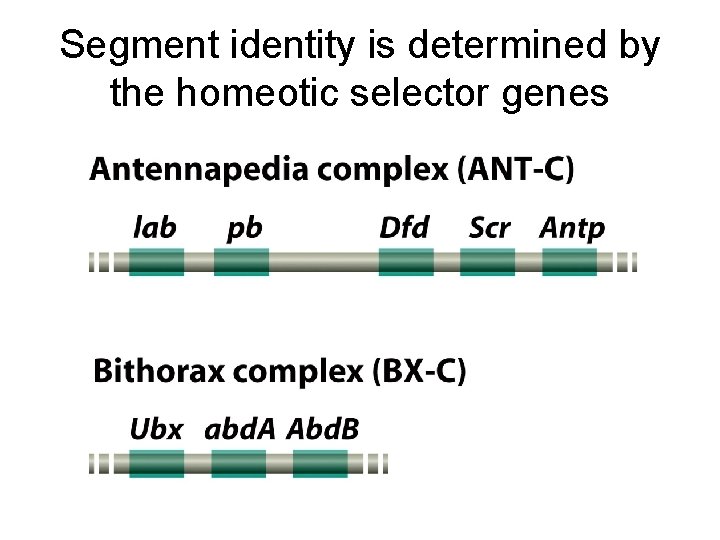

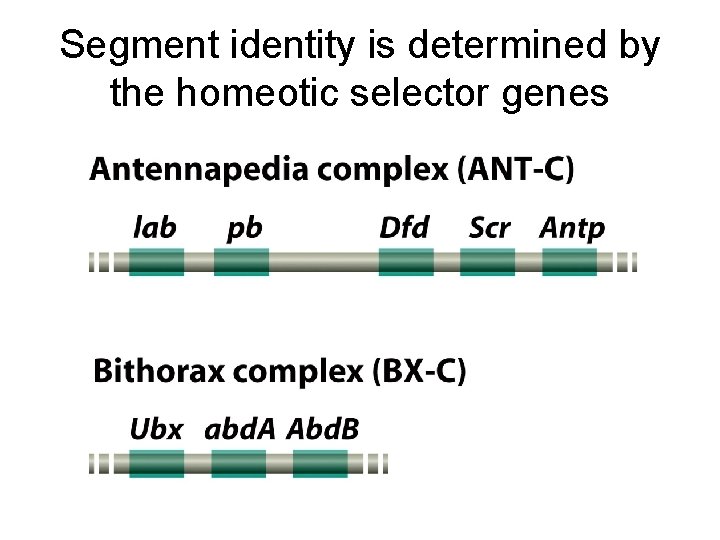

Segment identity is determined by the homeotic selector genes

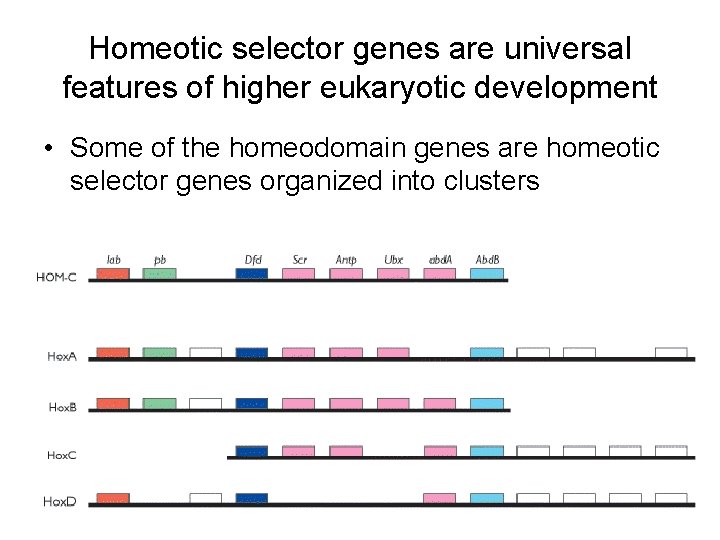

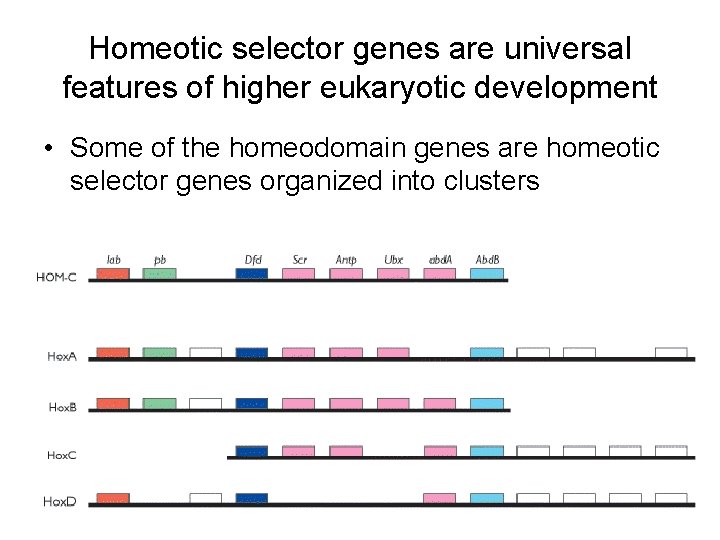

Homeotic selector genes are universal features of higher eukaryotic development • Some of the homeodomain genes are homeotic selector genes organized into clusters

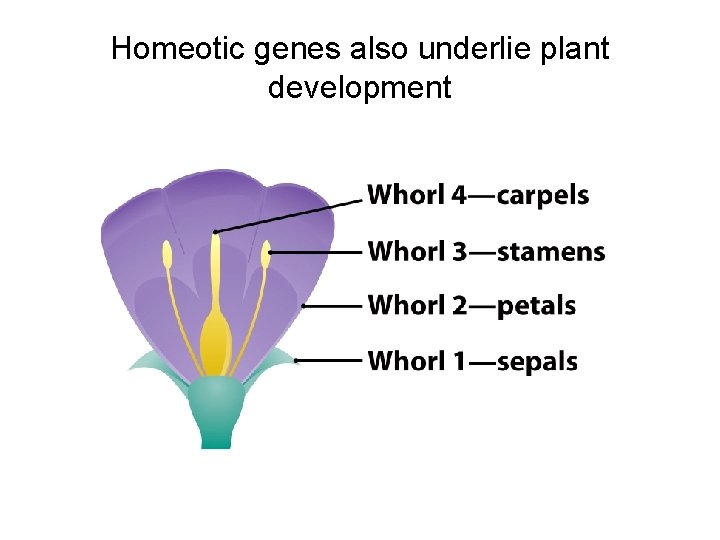

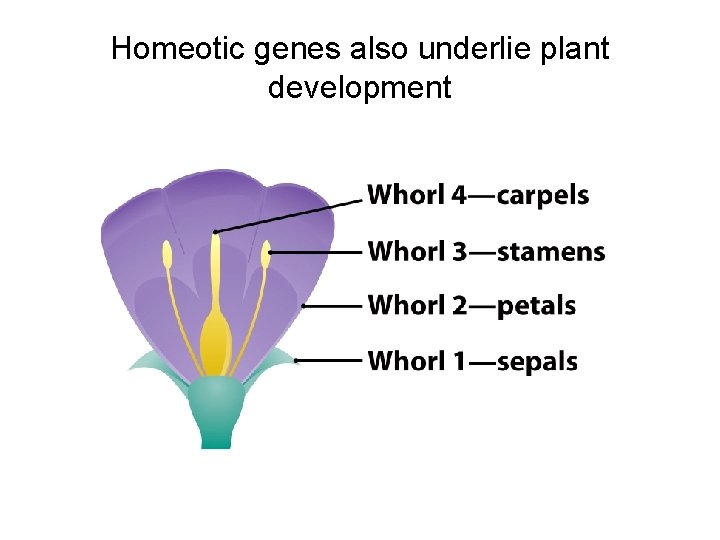

Homeotic genes also underlie plant development

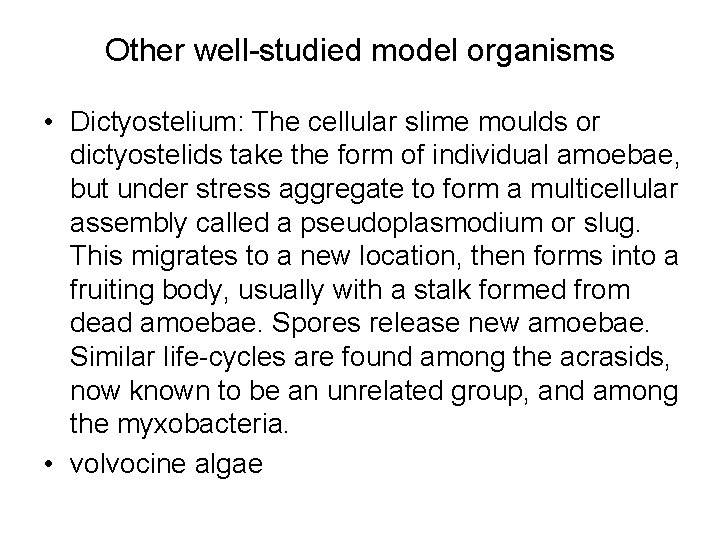

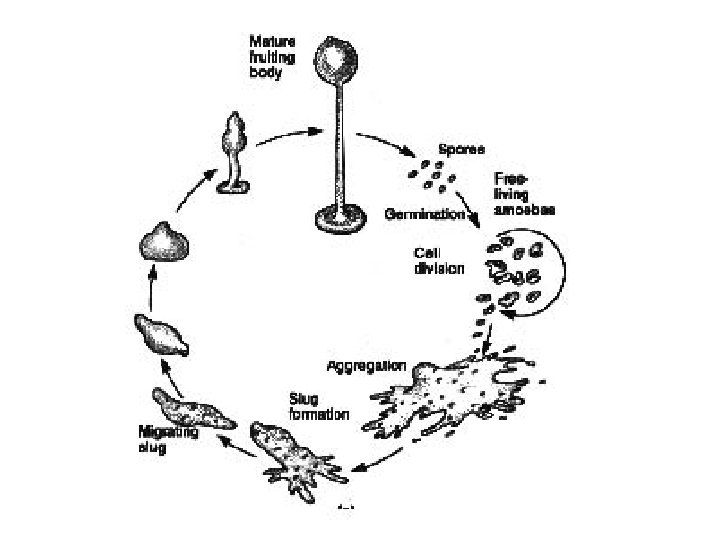

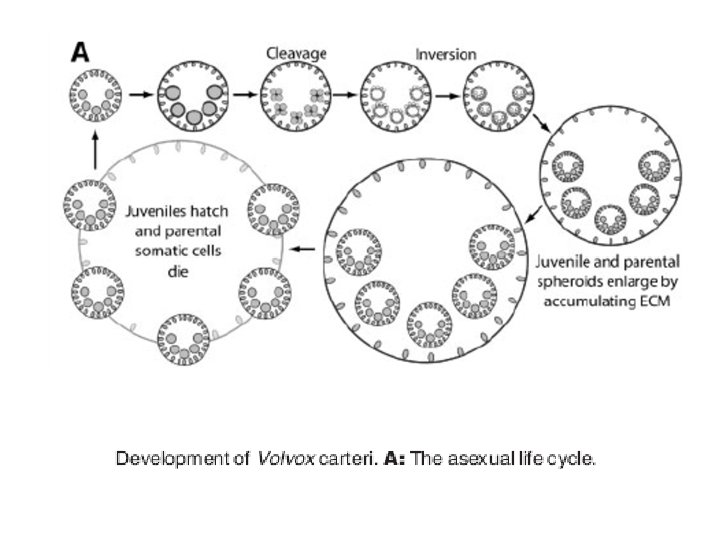

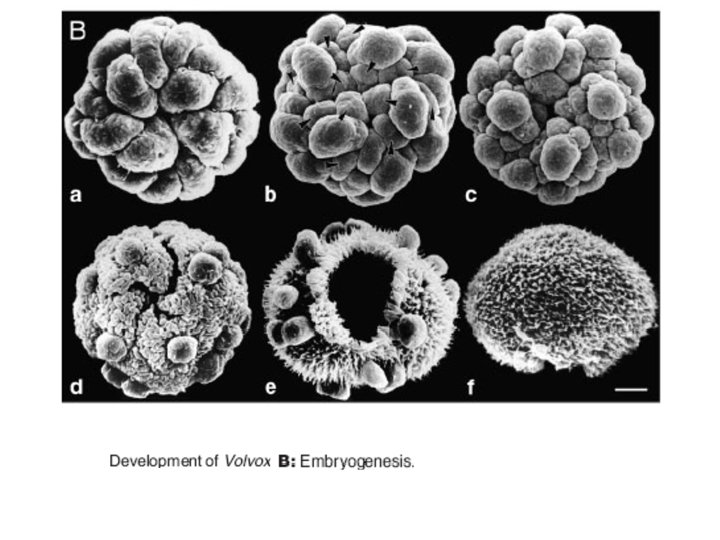

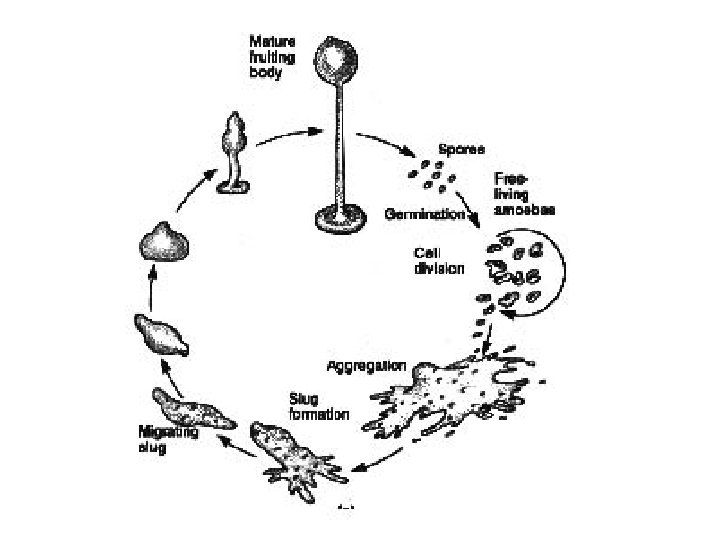

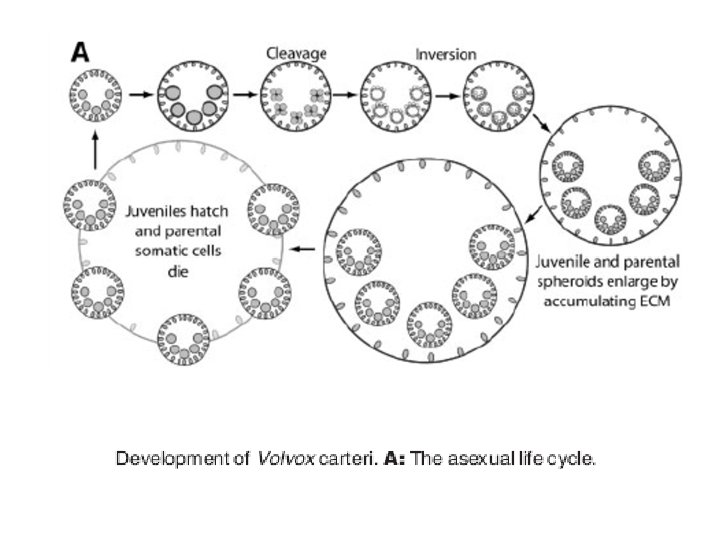

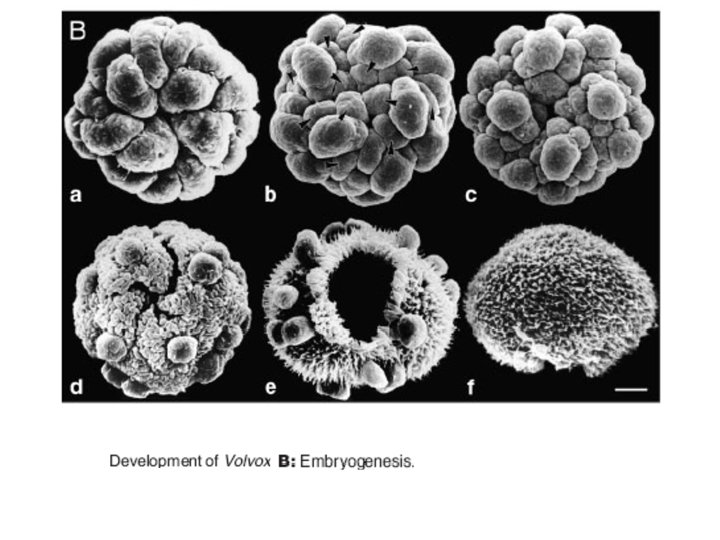

Other well-studied model organisms • Dictyostelium: The cellular slime moulds or dictyostelids take the form of individual amoebae, but under stress aggregate to form a multicellular assembly called a pseudoplasmodium or slug. This migrates to a new location, then forms into a fruiting body, usually with a stalk formed from dead amoebae. Spores release new amoebae. Similar life-cycles are found among the acrasids, now known to be an unrelated group, and among the myxobacteria. • volvocine algae

Further readings • Pleiss JA, Whitworth GB, Bergkessel M, Guthrie C: Rapid, transcript-specific changes in splicing in response to environmental stress. Mol Cell 2007, 27: 928 -937. • Yang L, Park J, Graveley BR: Splicing from the outside in. Mol Cell 2007, 27: 861 -862. • Lee W, Tillo D, Bray N, Morse RH, Davis RW, Hughes TR, Nislow C: A high- resolution atlas of nucleosome occupancy in yeast. Nat Genet 2007, 39: 1235 -1244.