Chapter 14 Complex Numbers in Algebra Impossible Numbers

Chapter 14 Complex Numbers in Algebra • • • Impossible Numbers Quadratic Equations Cubic Equations Attempt at Geometric Representation Angle Division The Fundamental Theorem of Algebra

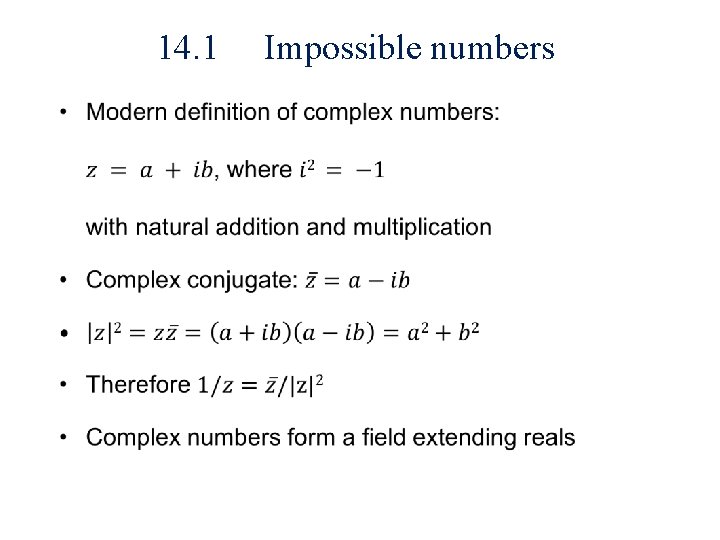

14. 1 Impossible numbers •

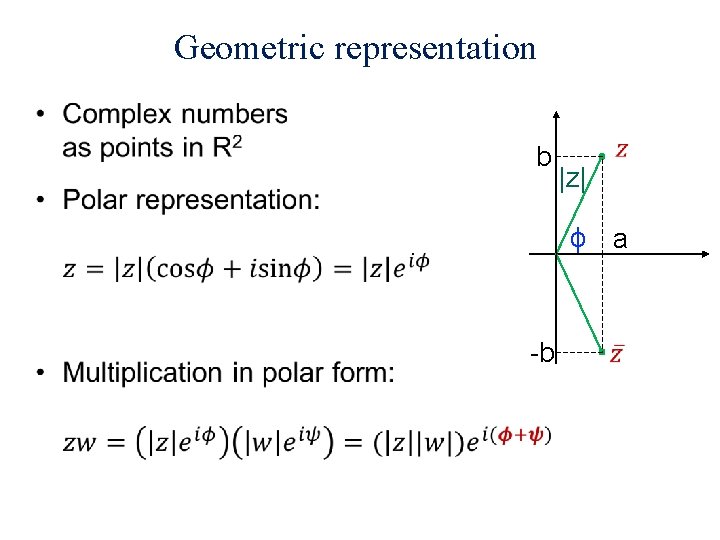

Geometric representation • b |z| ϕ a -b

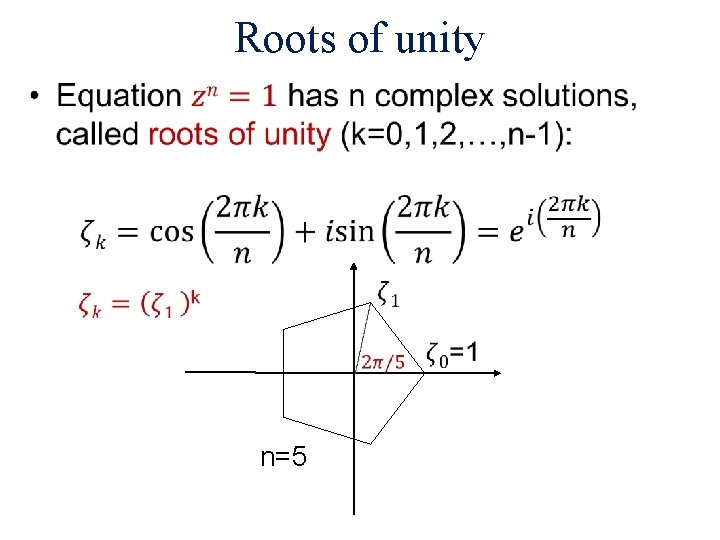

Roots of unity • n=5

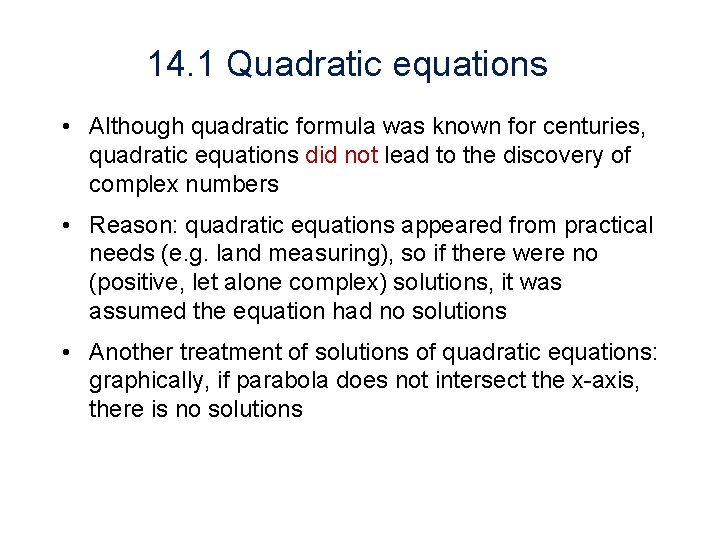

14. 1 Quadratic equations • Although quadratic formula was known for centuries, quadratic equations did not lead to the discovery of complex numbers • Reason: quadratic equations appeared from practical needs (e. g. land measuring), so if there were no (positive, let alone complex) solutions, it was assumed the equation had no solutions • Another treatment of solutions of quadratic equations: graphically, if parabola does not intersect the x-axis, there is no solutions

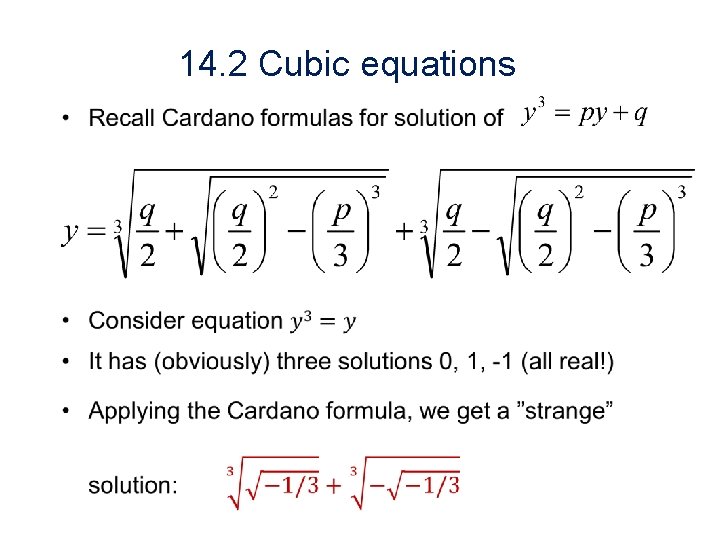

14. 2 Cubic equations •

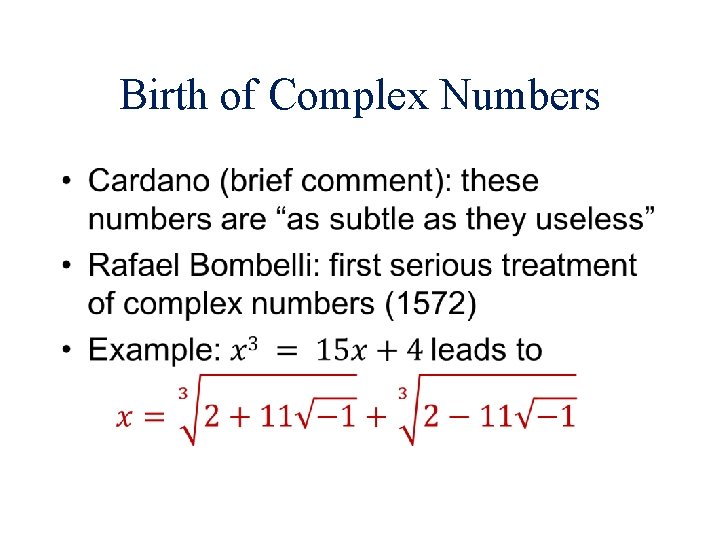

Birth of Complex Numbers •

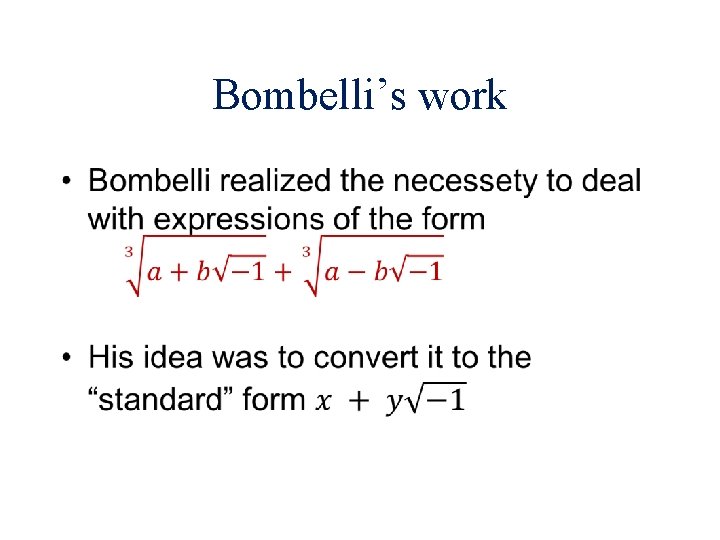

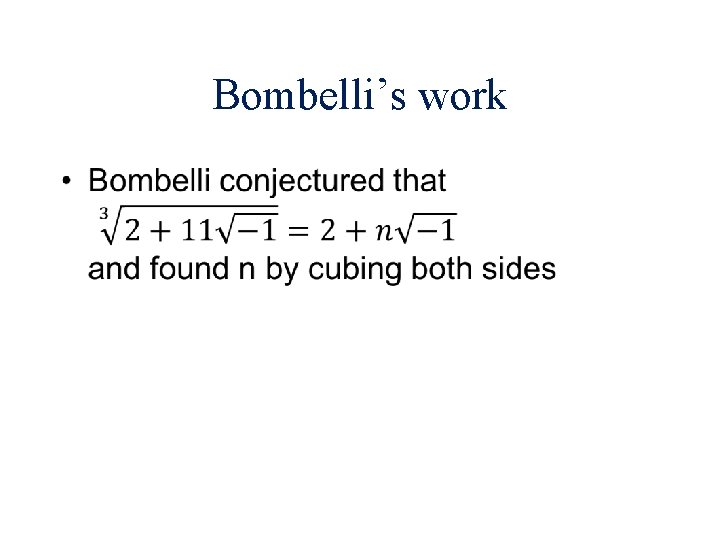

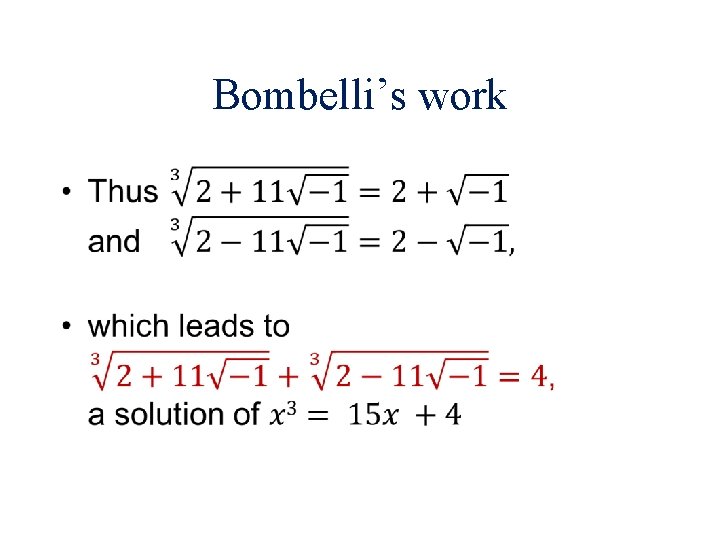

Bombelli’s work •

Bombelli’s work •

Bombelli’s work •

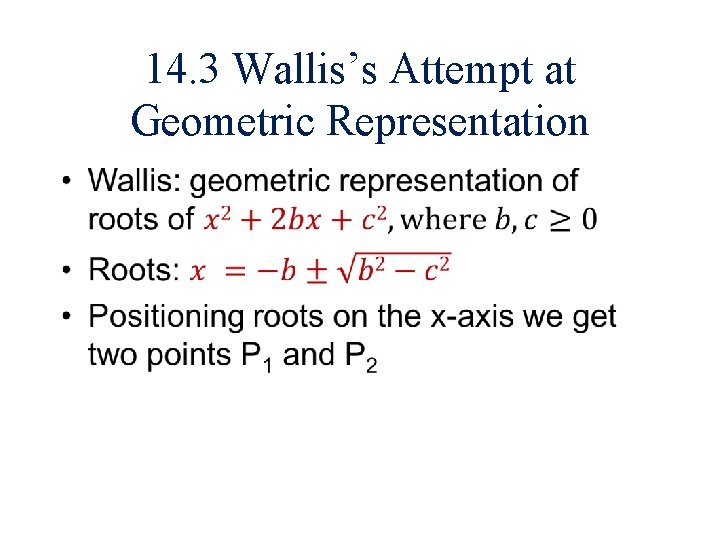

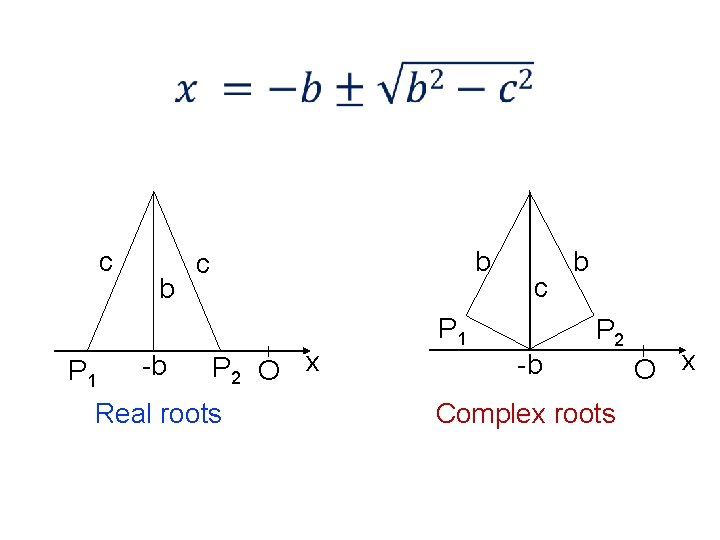

14. 3 Wallis’s Attempt at Geometric Representation •

c P 1 b -b b c P 2 O x Real roots c P 1 -b b P 2 Complex roots O x

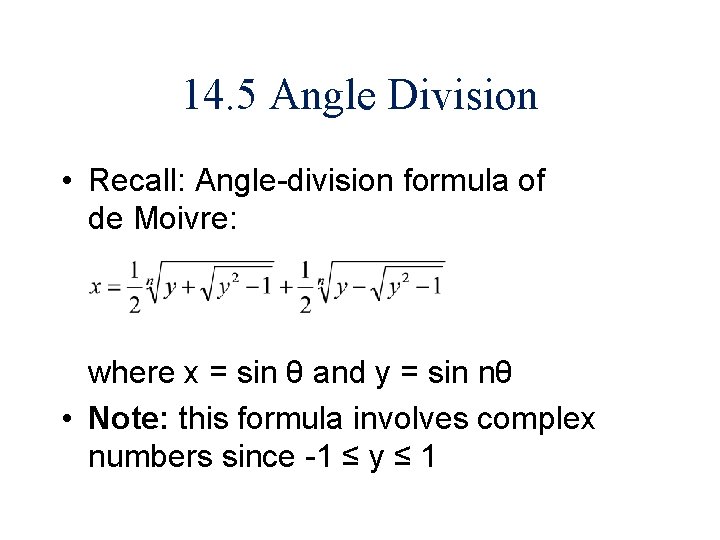

14. 5 Angle Division • Recall: Angle-division formula of de Moivre: where x = sin θ and y = sin nθ • Note: this formula involves complex numbers since -1 ≤ y ≤ 1

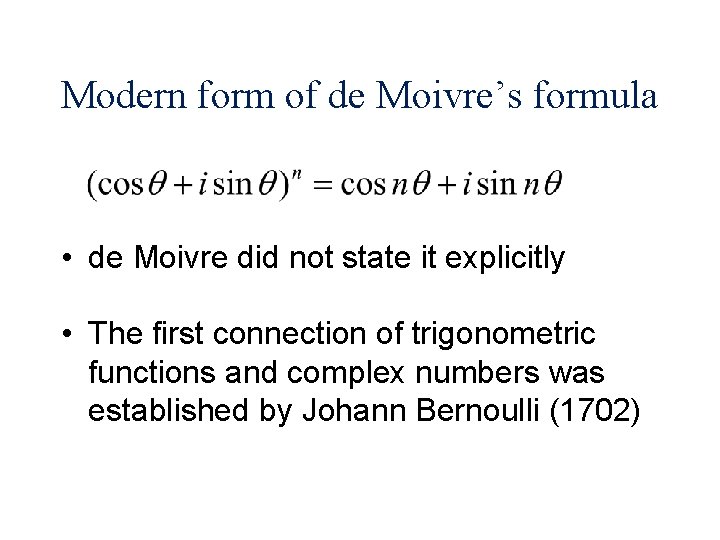

Modern form of de Moivre’s formula • de Moivre did not state it explicitly • The first connection of trigonometric functions and complex numbers was established by Johann Bernoulli (1702)

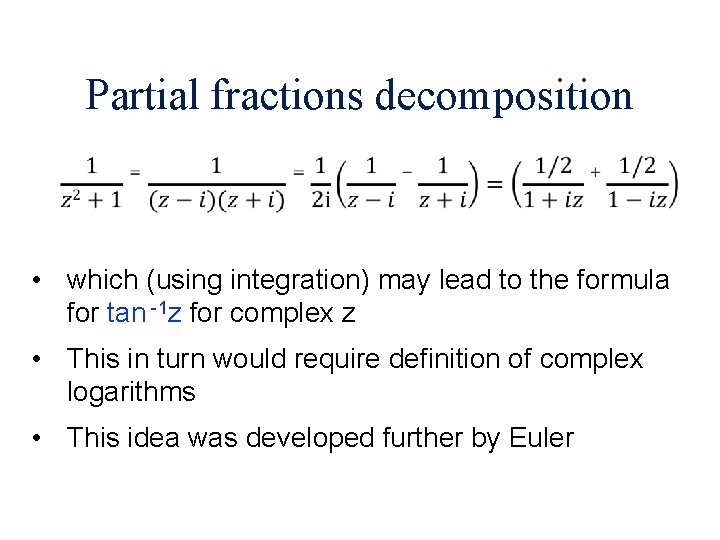

Partial fractions decomposition • which (using integration) may lead to the formula for tan -1 z for complex z • This in turn would require definition of complex logarithms • This idea was developed further by Euler

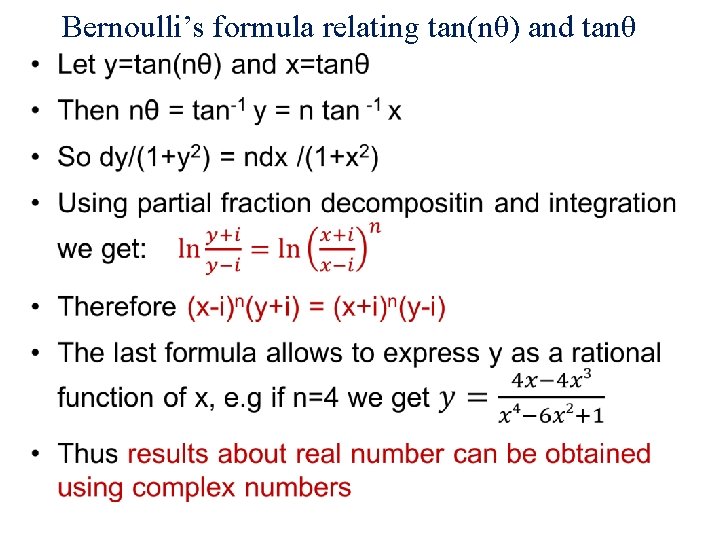

Bernoulli’s formula relating tan(nθ) and tanθ •

Cotes theorem about regular polygons • Roger Cotes (1682 – 1716) § Newton-Cotes formula for numerical integration § ix = ln (cos x + i sin x) (similar to Euler’s formula eix = cos x + i sin x) § Cotes assigned point (a, b) to a+b√-1 § He was also interested in integrating 1/(1 -xn) and 1/(1+xn) using partial fractions

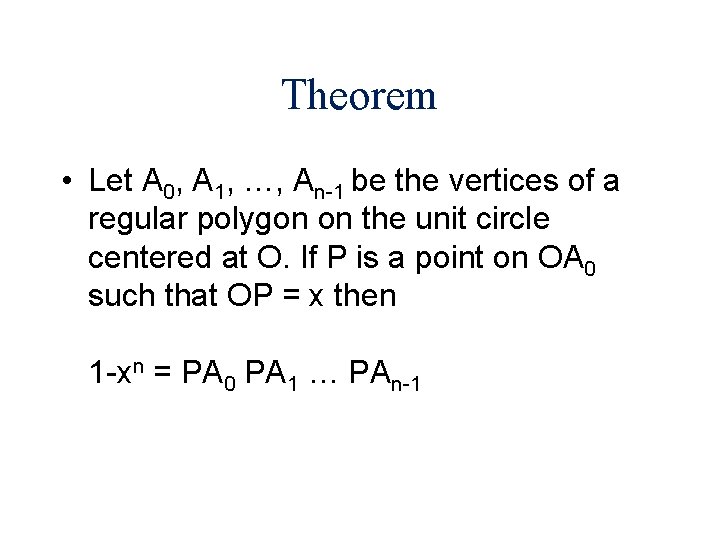

Theorem • Let A 0, A 1, …, An-1 be the vertices of a regular polygon on the unit circle centered at O. If P is a point on OA 0 such that OP = x then 1 -xn = PA 0 PA 1 … PAn-1

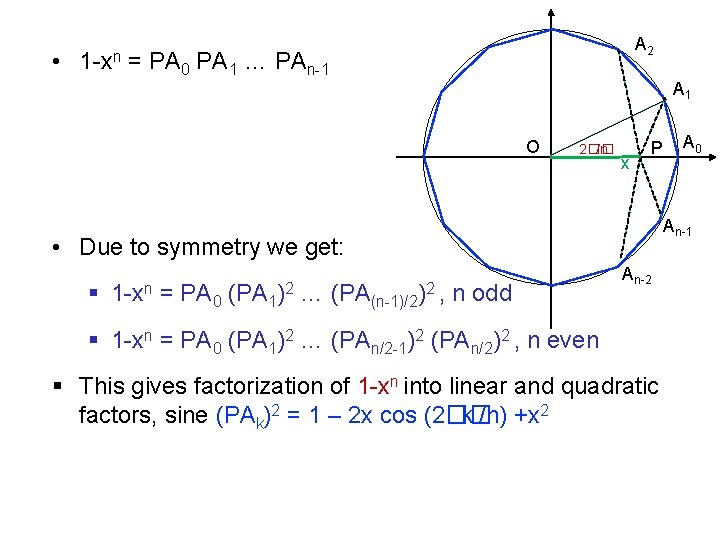

• 1 -xn = PA A 2 0 PA 1 … PAn-1 A 1 O 2�� /n x A 0 An-1 • Due to symmetry we get: § 1 -xn = PA 0 (PA 1)2 … (PA(n-1)/2)2 , n odd P An-2 § 1 -xn = PA 0 (PA 1)2 … (PAn/2 -1)2 (PAn/2)2 , n even § This gives factorization of 1 -xn into linear and quadratic factors, sine (PAk)2 = 1 – 2 x cos (2�� k /n) +x 2

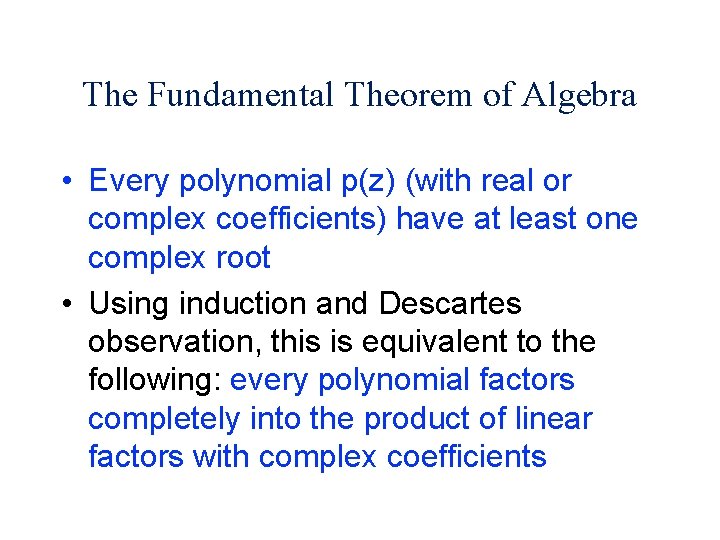

14. 6 The Fundamental Theorem of Algebra • The question of factorization of polynomials in connection with integration by partial fractions • Descartes: if z = a is a solution of p(z)=0 then p(z) = (z-a) q(z), where q is a polynomial of deg p - 1 • The can be proved using “long division” of polynomial

The Fundamental Theorem of Algebra • Every polynomial p(z) (with real or complex coefficients) have at least one complex root • Using induction and Descartes observation, this is equivalent to the following: every polynomial factors completely into the product of linear factors with complex coefficients

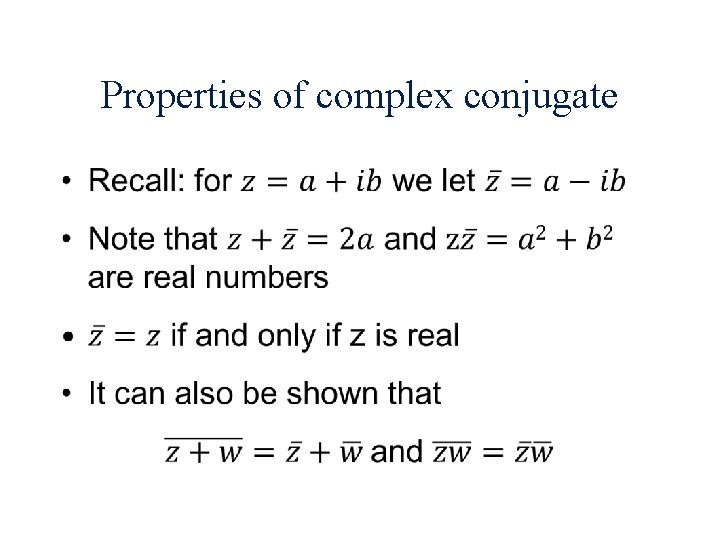

Properties of complex conjugate •

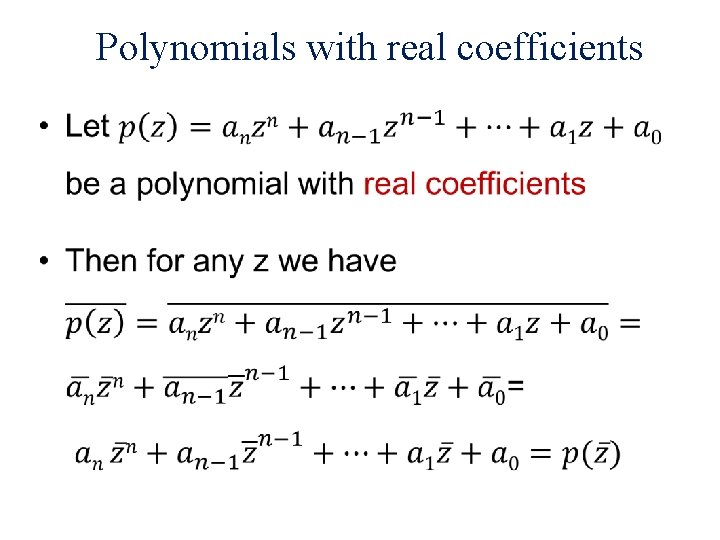

Polynomials with real coefficients •

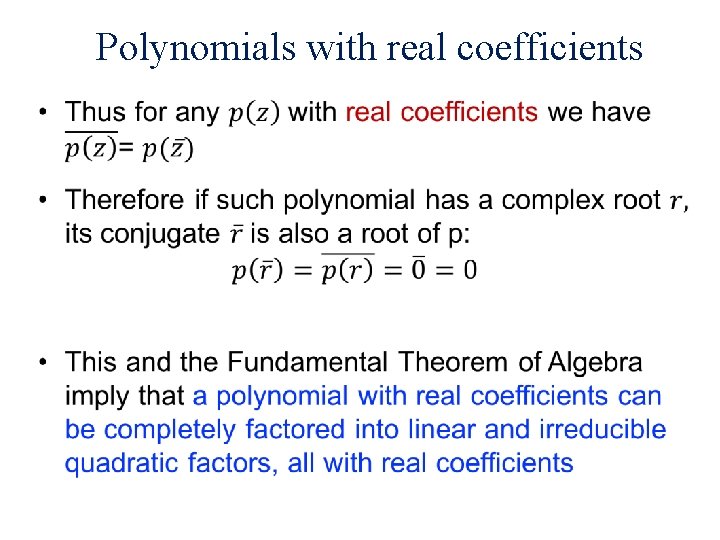

Polynomials with real coefficients •

14. 7 The Proofs of d’Alembert and Gauss • The Fundamental Theorem of Algebra can be proved in many different ways • The first proofs were given by d’Alembert (1746) and Gauss (1799) • Both proofs are incomplete according to the modern standards • However, the proofs are correct after all necessary details are supplied

d’Alembert’s proof • Two ingredients: d’Alembert Lemma and asymptotic behavior of a polynomial • Lemma. If p(z) is non-constant polynomial and p(z 0) ≠ 0 then any neighborhood of z 0 contains a point z 1 such that |p(z 1)|<|p(z 0)| • d’Alembert proved this lemma using fractional power series (rigorously developed by Puiseux in 1850) • Nevertheless, the lemma can be proved by more elementary methods • Another statement used in the proof is the extreme value theorem (rigorously proved by Weierstrass in 1874)

Gauss’ proof • Uses asymptotic behavior of a polynomial • Goal: to show that p(z)=0 in some circle of large radius R (similar to d’Alembert’s proof) • Recall: Re(a+ib)=a, Im(a+ib)=b • Gauss looked at the curves Re[p(z)]=0 and Im [p(z)]=0 • If there is z s. t. these two curves intersect, we are done, since in this case Re[p(z)]=Im[p(z)]=0 and so p(z)=0 • For large |z|, they are close to Re(zn)=0 and Im(zn)=0 (assuming an=1)

![Gauss’ proof • It can be shown that the curves Re[p(z)]=0 and Im[p(z)]=0 are Gauss’ proof • It can be shown that the curves Re[p(z)]=0 and Im[p(z)]=0 are](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/fdf07cadc73c0853b0487a0b347a624f/image-28.jpg)

Gauss’ proof • It can be shown that the curves Re[p(z)]=0 and Im[p(z)]=0 are algebraic • Also, the curves Re[zn]=0 and Im[zn]=0 are collections of straight lines that intersect any circle centered at the origin alternately • Therefore, by continuity, the curves Re[p(z)]=0 and Im[p(z)]=0 intersect a circle (of a sufficiently large radius) alternately • Gauss claimed that it obviously implies that the curves intersect somewhere inside the circle • However, the rigorous proof of this fact is hard and non-elementary (the first proof is due to Ostrowski (1920))

- Slides: 28