chapter 14 Body Composition and Nutrition for Sport

chapter 14 Body Composition and Nutrition for Sport

Learning Objectives: Body Composition • Find out what tissues of the body constitute fat-free mass • Discover how densitometry—and other laboratory and field techniques—are used to assess body composition • Examine the relationship of relative leanness and fatness to performance in sport • Find out what guidelines best determine an athlete’s goal weight

Learning Objectives: Nutrition and Sport • Review the six categories of nutrients and learn what amount of intake is necessary for normally active men and women • Discover the roles of carbohydrate, dietary fat, and protein in athletic performance • Find out which vitamins and minerals are most important in an athlete’s diet • Learn about water and electrolyte balance in athletes (continued)

Learning Objectives: Nutrition and Sport (continued) • To investigate the potential benefits of supplementing carbohydrate, protein, fat, vitamins, and minerals for increasing athletic performance • Find out what makes up a recommended precompetition meal and how to properly load the muscles with glycogen before an endurance event • Learn the value in ingesting carbohydrate during and after endurance exercise and what constitutes the most effective sport drink

Body Composition in Sport Body composition refers to the chemical composition of the body 1. Chemical model 2. Anatomical model 3. Two-compartment model

Three Models of Body Composition Adapted, by permission, from J. H. Wilmore, 1992, Body weight and body composition. In Brownell, Rodin, and Wilmore (Eds. ) Eating, body weight, and performance in athletes: Disorders of modern society (Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins), 77 -93.

Body Mass Fat mass: the total body mass that is composed of fat Fat-free mass: all body tissues that are not fat, including bone, muscle, organs, and connective tissue

Body Composition vs. Height and Weight in Athletes • Generally, an athlete’s body composition is of greater concern than total body size and weight • Standard height and weight tables do not provide accurate estimates of what an athlete should weigh because they do not take into account the composition of the weight • An athlete can be overweight according to standardized height and weight tables but be underfat or at optimal fat levels

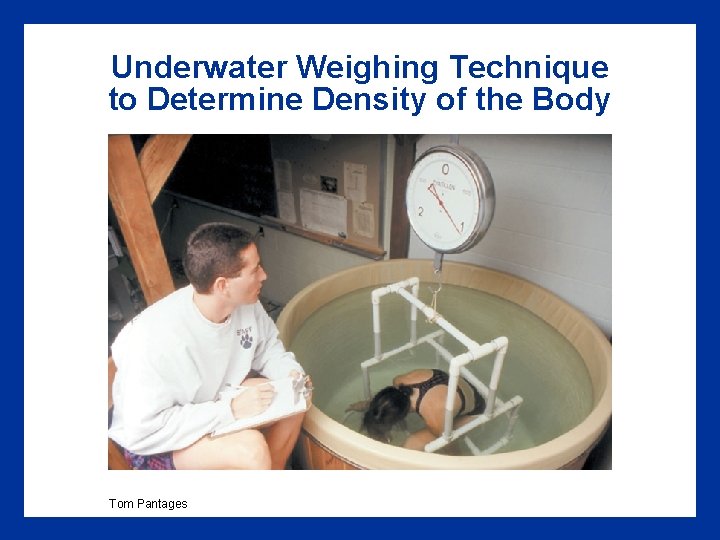

Densitometry • • • Body density = body mass ÷ body volume Density of fat-free mass is higher than the density of water Density of fat is lower than the density of water % body fat = (495 ÷ body density) – 450 Key assumptions: 1. The density of each tissue constituting the fat-free mass is known and remains constant 2. Each tissue type represents a constant proportion of the fat-free mass (e. g. , bone always represents 17% of the fat-free mass)

Underwater Weighing Technique to Determine Density of the Body Tom Pantages

Other Laboratory Techniques to Assess Body Composition • • Radiography Computed tomography (CT) Magnetic resonance imaging Hydrometry Total body electrical conductivity Neutron activation Dual-energy X-ray absorption (DEXA) Air displacement

Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry Machine Photo courtesy of Hologic, Inc.

Air Plethysmography: Bod Photo courtesy of Life Measurement, Inc.

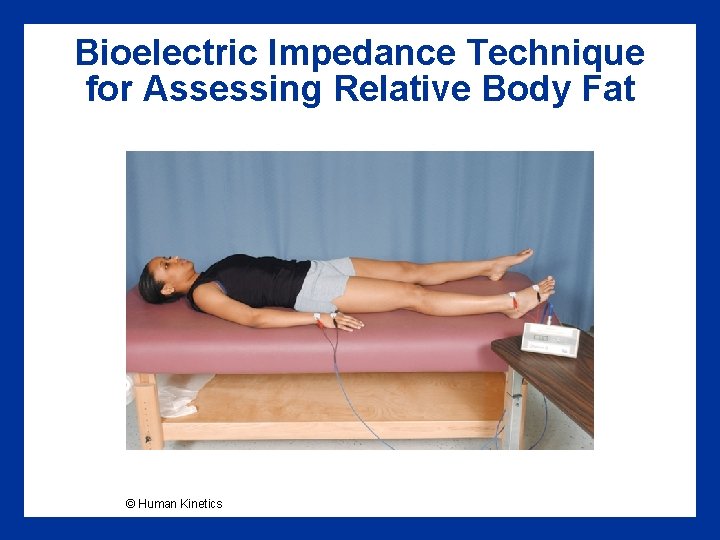

Field Techniques • Skinfold fat thickness – Sum of three or more sites used in a quadratic or curvilinear equation to estimate body density • Bioelectrical impedance – Tends to overestimate relative body fat in lean athletic populations

Measuring Skinfold Fat Thickness at the Triceps Skinfold Site © Human Kinetics

Bioelectric Impedance Technique for Assessing Relative Body Fat © Human Kinetics

Body Composition Key Points • Knowing a person’s body composition is more valuable for predicting performance potential than merely knowing height and weight • Densitometry is one of the best methods for assessing body composition and has long been considered the most accurate • Densitometry involves calculating the density of the athlete’s body by dividing body mass by volume, which is typically determined via hydrostatic weighing or air displacement (continued)

Body Composition (continued) Key Points • Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, originally developed for estimating bone density and bone mineral content, is now capable of providing accurate estimates of total body composition • Field techniques for assessing body composition include measuring skinfold fat thickness and bioelectrical impedance

Body Composition and Performance: Fat-Free Mass Maximizing Fat-Free Mass • Desirable for athletes involved in strength, power, and muscular endurance types of activities • May be undesirable for endurance athletes or jumping sports (horizontal movement)

Body Composition and Performance: Body Fat Relative Body Fat • A high relative body fat is generally detrimental to performance • Maintaining a low body fat is desirable in sports in which the body weight is moved through space (e. g. , running and jumping) • Increases in body fat might possibly be of benefit for: – Heavyweightlifters because it lowers their center of gravity – Sumo wrestlers – Swimmers because fat improves buoyancy

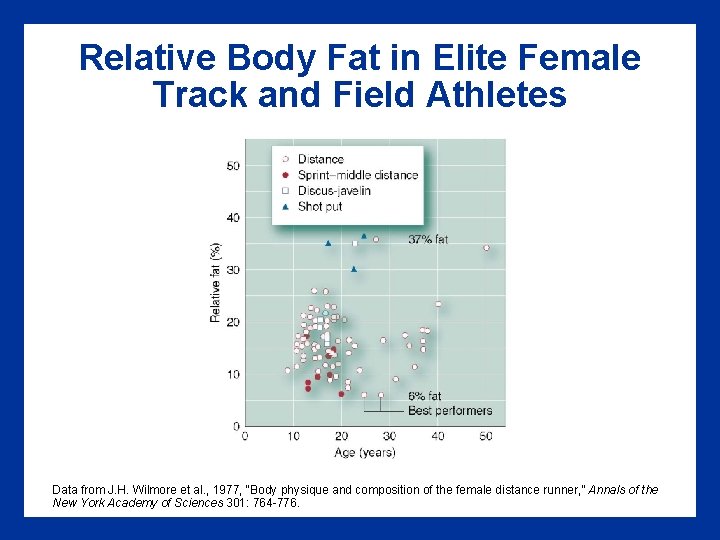

Relative Body Fat in Elite Female Track and Field Athletes Data from J. H. Wilmore et al. , 1977, “Body physique and composition of the female distance runner, ” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 301: 764 -776.

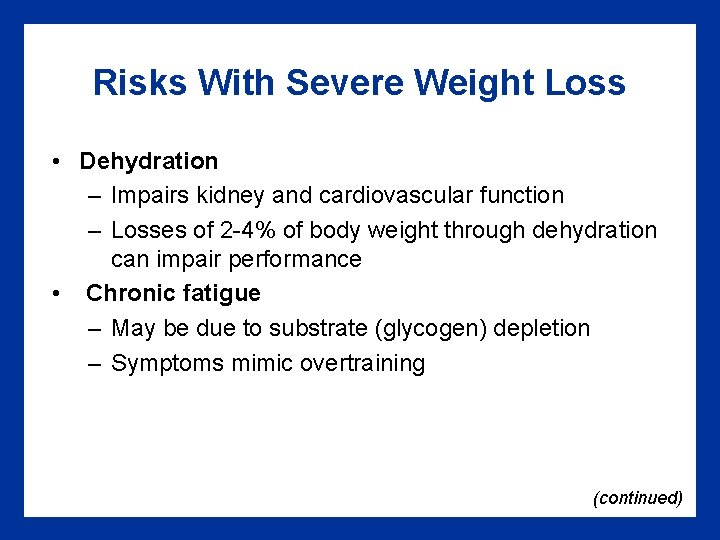

Risks With Severe Weight Loss • Dehydration – Impairs kidney and cardiovascular function – Losses of 2 -4% of body weight through dehydration can impair performance • Chronic fatigue – May be due to substrate (glycogen) depletion – Symptoms mimic overtraining (continued)

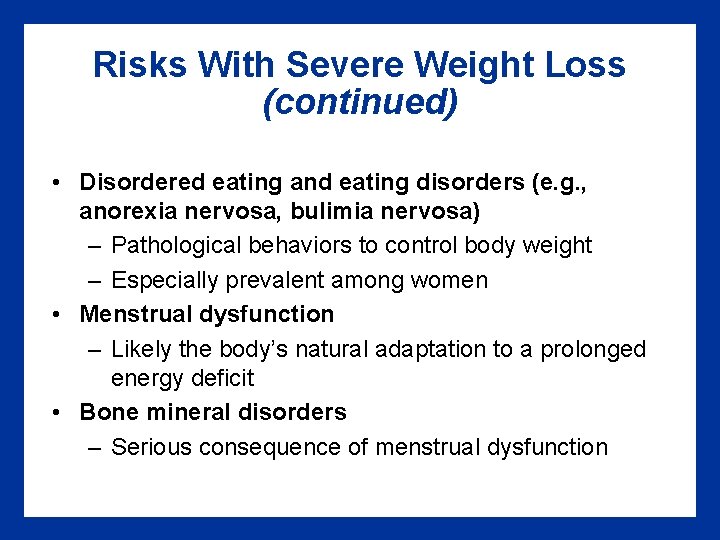

Risks With Severe Weight Loss (continued) • Disordered eating and eating disorders (e. g. , anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa) – Pathological behaviors to control body weight – Especially prevalent among women • Menstrual dysfunction – Likely the body’s natural adaptation to a prolonged energy deficit • Bone mineral disorders – Serious consequence of menstrual dysfunction

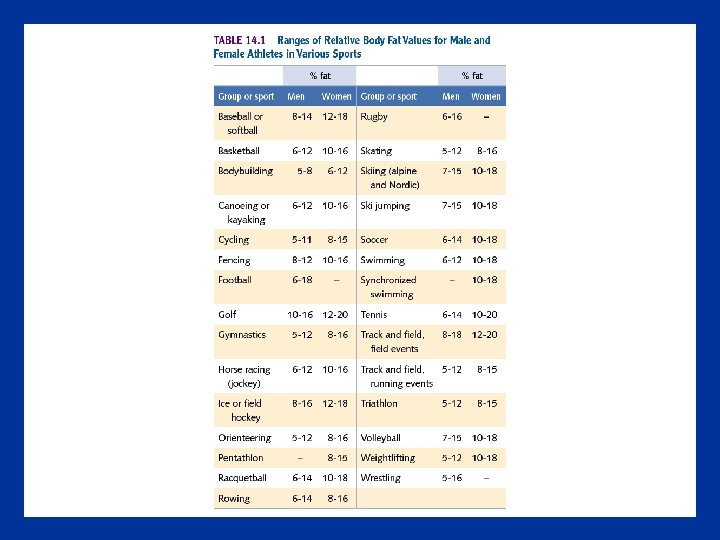

Establishing Appropriate Weight Standards • Based on body composition instead of weight • Sport and event specific • Optimal ranges for relative body fat should be established • Sex and individual differences should be considered • Methodological errors in body composition measurement should be considered

Body Composition and Sport Performance Key Points • Many sports enforce weight standards. Unfortunately athletes often turn to questionable, ineffective, or even dangerous methods of weight loss to reach weight goals • Severe weight loss can cause potential health problems, such as dehydration, chronic fatigue, disordered eating, menstrual dysfunction, and bone mineral disorders • Chronic fatigue symptoms that often accompany severe weight loss mimic those of overtraining (continued)

Body Composition and Sport Performance (continued) Key Points • Fatigue can also be caused by substrate depletion • Body weight standards should be based on body composition, emphasizing relative body fat rather than total body mass • For each sport, a range of values should be established, recognizing the importance of individual variation, methodological error, and sex differences

Achieving Optimal Weight • Avoid fasting and crash dieting • Work toward achieving the upper-end goal weight slowly • Lose no more than 0. 5 -1. 0 kg (1. 1 -2. 2 lb) per week • When the upper-end goal weight is achieved, further weight reduction should be achieved at an even slower rate (<0. 5 kg or 1. 1 lb per week) • Reduce caloric intake by 200 to 500 kcal per day • Eat at least 3 balanced meals per day • Use moderate resistance and endurance training

Achieving Optimal Weight Key Points • When severe diets are followed, much of the weight loss that occurs is from water, not fat • Most severe diets limit carbohydrate intake, depleting carbohydrate stores, which exacerbates the problem of dehydration • The combination of diet and exercise is the preferred approach for optimal weight loss • Athletes should initially lose no more than 0. 5 -1. 0 kg per week until reaching the upper end of the desired weight range, then no more than 0. 5 kg per week until the goal weight is reached (continued)

Achieving Optimal Weight (continued) Key Points • Weight loss can be accomplished by reducing dietary intake by 200 -500 kcal per day in combination with a sound exercise program • For fat loss, moderate resistance and endurance training is most effective • Resistance training promotes gains in fat-free mass

Nutrition and Sport • Nutrients – Carbohydrate, fat, and protein – Vitamins – Minerals – Water and electrolyte balance • Dehydration and exercise performance • The athlete’s diet

Six Nutrient Classes • • • Carbohydrate Fat Protein Vitamins Minerals Water

Carbohydrate (CHO) • Classified as a monosaccharide, disaccharide, or polysaccharide • Major source of energy, particularly during highintensity exercise • Regulates fat and protein metabolism • Exclusive energy source for the nervous system • Synthesized into muscle and liver glycogen • Sources include grains, fruit, vegetables, milk, and concentrated sweets

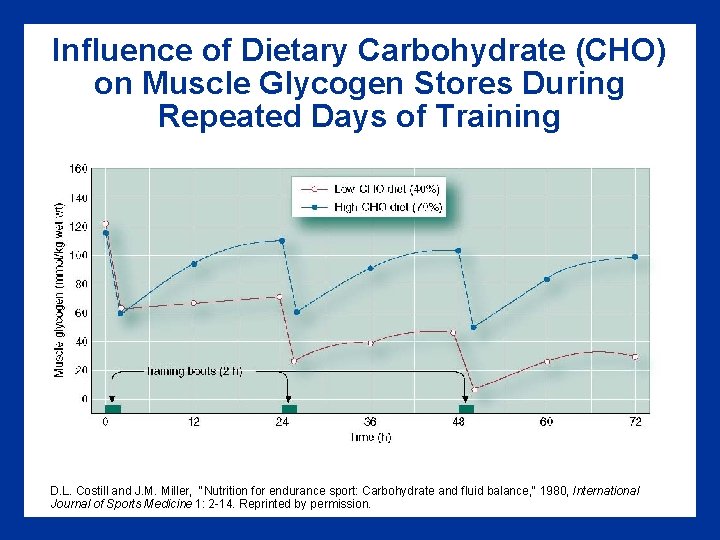

Influence of Dietary Carbohydrate (CHO) on Muscle Glycogen Stores During Repeated Days of Training D. L. Costill and J. M. Miller, "Nutrition for endurance sport: Carbohydrate and fluid balance, " 1980, International Journal of Sports Medicine 1: 2 -14. Reprinted by permission.

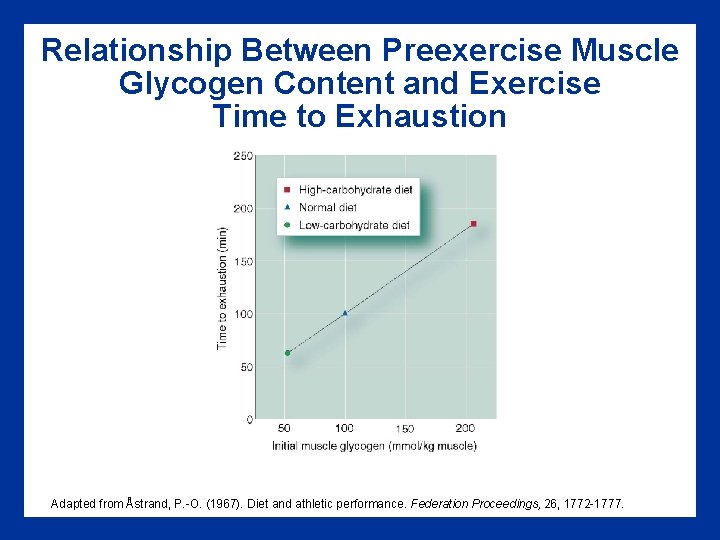

Relationship Between Preexercise Muscle Glycogen Content and Exercise Time to Exhaustion Adapted from Åstrand, P. -O. (1967). Diet and athletic performance. Federation Proceedings, 26, 1772 -1777.

The Glycemic Index (GI) • The glycemic index (GI) refers to the increase in blood glucose and insulin in response to a standard amount of food • GI reference value is the blood sugar concentration after the ingestion of 50 g of glucose or white bread • GI = 100 x (blood glucose response over 2 h to 50 g of test food / blood glucose response over 2 h to 50 g of glucose or white bread)

Glycemic Index GI value Example foods High GI >70 Sport drinks, jelly beans, baked potato Moderate GI 56 -70 Pastry, pita bread, bananas, regular ice cream Low GI ≤ 55 White spaghetti, kidney beans, milk, apples, pears, peanuts

Glycemic Load (GL) • GL has been proposed to be important during exercise • Considers both the GI and the amount of CHO in a single serving • GL = (GI x CHO, g) / 100

CHO Intake and Performance • Preexercise (glycogen or CHO loading) • During exercise • Postexercise

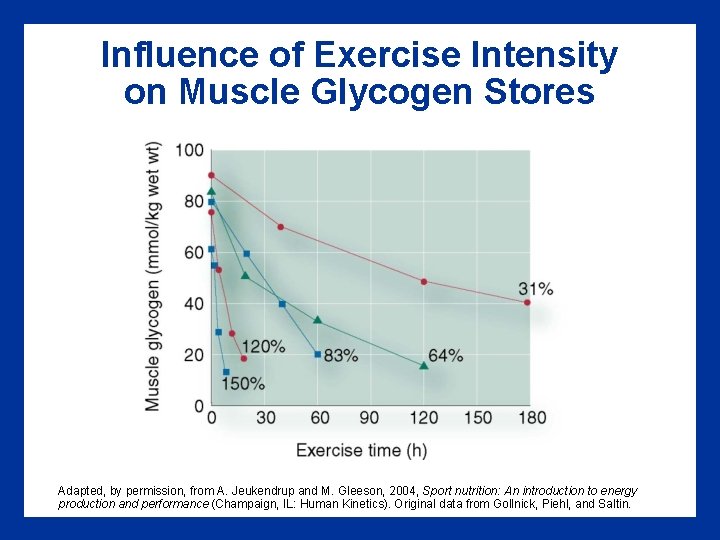

Influence of Exercise Intensity on Muscle Glycogen Stores Adapted, by permission, from A. Jeukendrup and M. Gleeson, 2004, Sport nutrition: An introduction to energy production and performance (Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics). Original data from Gollnick, Piehl, and Saltin.

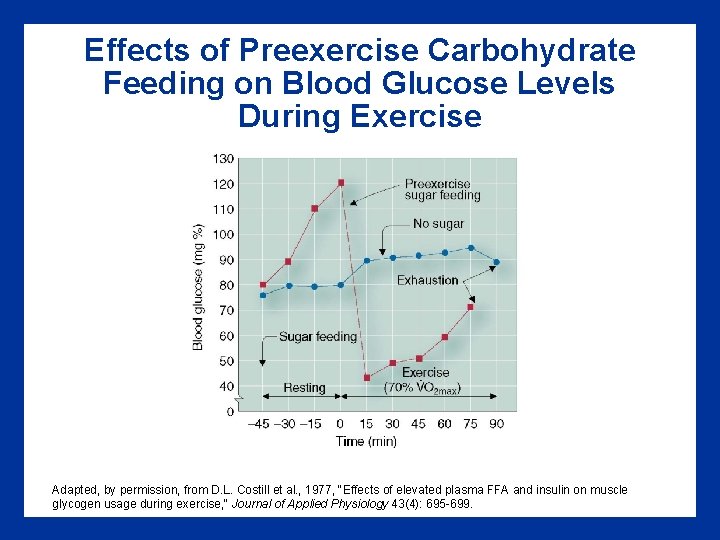

Effects of Preexercise Carbohydrate Feeding on Blood Glucose Levels During Exercise Adapted, by permission, from D. L. Costill et al. , 1977, "Effects of elevated plasma FFA and insulin on muscle glycogen usage during exercise, " Journal of Applied Physiology 43(4): 695 -699.

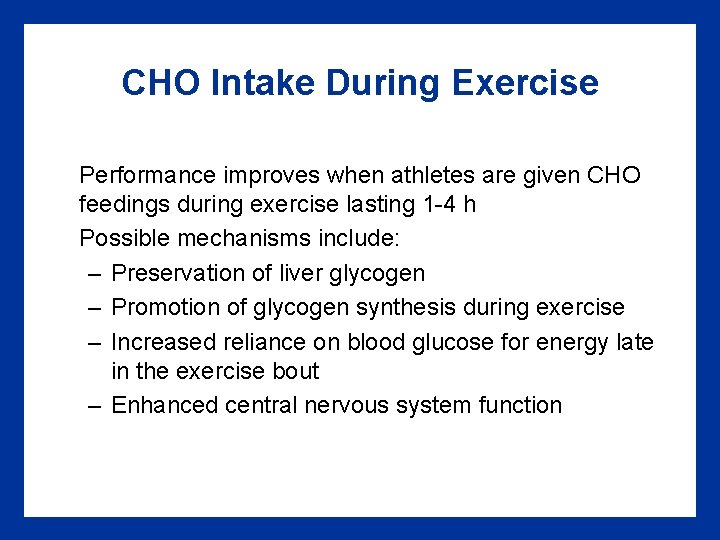

CHO Intake During Exercise Performance improves when athletes are given CHO feedings during exercise lasting 1 -4 h Possible mechanisms include: – Preservation of liver glycogen – Promotion of glycogen synthesis during exercise – Increased reliance on blood glucose for energy late in the exercise bout – Enhanced central nervous system function

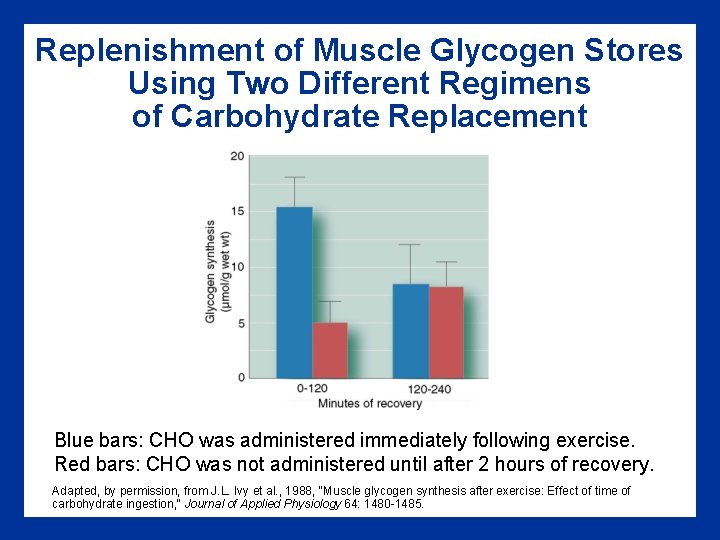

CHO Consumption After Exercise • Improves glycogen resynthesis rates • Most effective when given during the first two hours of recovery • May be enhanced by the addition of protein

Replenishment of Muscle Glycogen Stores Using Two Different Regimens of Carbohydrate Replacement Blue bars: CHO was administered immediately following exercise. Red bars: CHO was not administered until after 2 hours of recovery. Adapted, by permission, from J. L. Ivy et al. , 1988, "Muscle glycogen synthesis after exercise: Effect of time of carbohydrate ingestion, " Journal of Applied Physiology 64: 1480 -1485.

Ergogenic Properties of CHO Key Points • CHO are sugars and starches that the body must break down into monosaccharides to use for fuel • Insufficient intake of CHO during periods of intense training can lead to depletion of glycogen stores • Muscle glycogen loading offers major benefits to performance • Endurance performance can be enhanced when CHO is consumed up to an hour before exercise, within 5 min of starting exercise, and during exercise • People can replenish CHO stores rapidly by ingesting CHO during the first 2 h of recovery

Fat • Forms include: triglycerides, free fatty acids, phospholipids, and sterols • Essential component of cell membranes and nerve fibers • Primary source of energy, providing up to 70% energy at rest • Cushions vital organs • Produces all steroid hormones • Transports and stores fat-soluble vitamins • Preserves body heat by providing insulation

Fat Intake and Performance High-fat diets (“fat loading”) – The theory is that high-fat diets may spare muscle glycogen, thus enhancing endurance performance – Most studies have shown either no benefit or decreased performance – The body adapts by increasing the supply of fat and the capacity for fat oxidation – Usually muscle glycogen stores decrease

Ergogenic Properties of Fat Key Points • Fats exist in the body as triglycerides, FFAs, phospholipids, and sterols • Stored primarily as triglycerides • Only FFAs are used by the body for energy production • Although fat is a major energy source, the use of high-fat diets to enhance endurance performance by sparing glycogen has generally been unsuccessful

Protein • Makes up cell structure • Used for growth, repair, and maintenance of body tissues • Hemoglobin, enzymes, and peptide hormones • A primary buffer in the control of acid–base balance • Maintains normal blood osmotic pressure • Forms antibodies for disease protection • Energy production

Protein Intake and Performance • Protein and amino acid requirements are higher for athletes in training – Strength training athletes need 1. 6 -1. 7 g/kg per day – Endurance athletes need 1. 2 -1. 4 g/kg per day • Protein intake exceeding 1. 7 g/kg per day provides no additional advantage • Adding protein to CHO enhances glycogen synthesis following intense aerobic exercise • Increases muscle protein synthesis after a bout of resistance training

Ergogenic Properties of Protein Key Points • The smallest unit of protein is an amino acid • Only nonessential amino acids can be synthesized by the body • Essential amino acids must be obtained through our diets • Protein is not a primary energy source, but it can be used for energy production during endurance exercise (continued)

Ergogenic Properties of Protein (continued) Key Points • • RDA for protein is 0. 8 g/kg per day Strength athletes need 1. 6 to 1. 7 g/kg per day Endurance athletes need 1. 2 to 1. 4 g/kg per day Diets exceeding 1. 7 g/kg per day have not been proven to provide additional benefits and may damage kidney function • Protein supplementation during recovery from resistance training can stimulate muscle protein synthesis

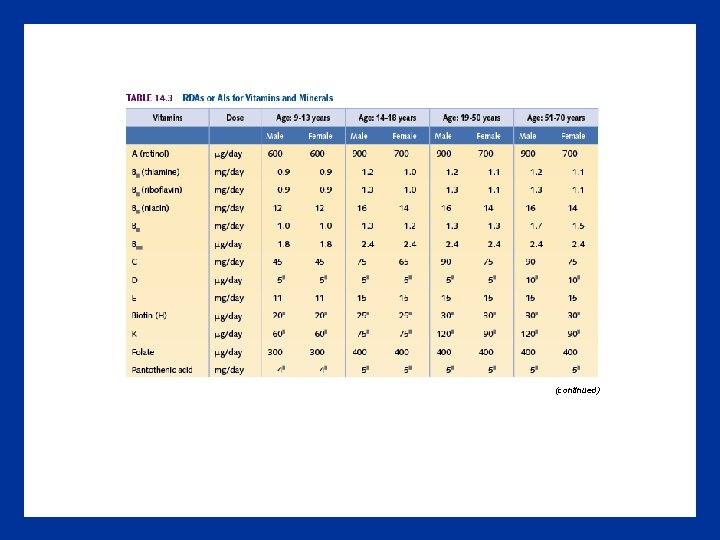

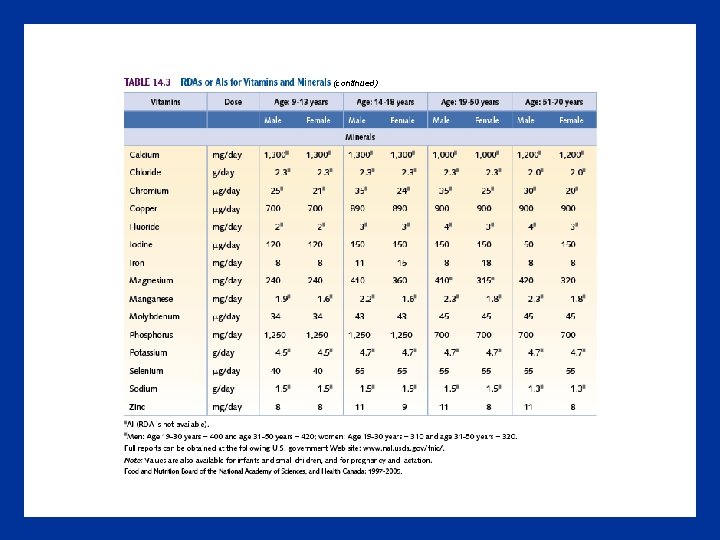

Vitamins • Promote growth and maintain health • Act as catalysts in chemical reactions • Fat soluble – A, D, E, and K – Absorbed from digestive tract bound to lipids – Excessive intake can cause toxic accumulations • Water soluble – B-complex and vitamin C – Absorbed from digestive tract with water – Excess is excreted, mostly in the urine

(continued)

(continued)

Vitamins A, D, and K • Vitamin A is crucial for normal growth and development because it plays an integral role in bone development • Vitamin D is essential for intestinal absorption of calcium and phosphorous and thus bone development • Vitamin K is an intermediate in the electron transport chain

B-Complex Vitamins • Include more than 1 dozen vitamins • Serve as cofactors in various enzyme systems involved in oxidation of food and energy production • Needed (B 12) for red blood cell production • Deficiency impairs performance

Vitamin C (Ascorbic Acid) • Important in the formation and maintenance of collagen in connective tissue • Helps metabolize amino acids • Helps synthesize epinephrine, norepinephrine, and antiinflammatory corticoids • Promotes iron absorption • Supplementation does not appear to improve performance if no deficiency exists

Vitamin E • • Stored in muscle and fat Prevents oxidation of vitamins A and C Acts as antioxidant to disarm free radicals Supplementation has not been proven to improve performance

Minerals Electrolytes are mineral compounds that can dissociate into ions in the body Macrominerals are minerals that your body needs >100 mg of per day Microminerals are minerals that your body needs ≤ 100 mg of per day Trace elements are minerals needed in smaller amounts

Calcium • Most abundant mineral in the body (~40% of the body’s bone mineral content) • Stored in the bones • Builds and maintains healthy bone • Essential in nerve impulse transmission • Activates enzymes and regulates cell membrane permeability • Essential for normal muscle function • Deficiency can lead to osteopenia, which can lead to osteoporosis

Phosphorus • Commonly linked to calcium in form of calcium phosphate (~22% of the body’s bone mineral content) • Provides strength and rigidity to bones • Essential to metabolism, cell membrane structure • Helps maintain constant blood p. H • Essential component of ATP

Iron • • • Micromineral (35 -50 mg/kg of body weight) Crucial for oxygen transport Helps form hemoglobin and myoglobin Deficiency is relatively common, more so in women Supplementation can improve aerobic capacity in irondeficient athletes

Sodium, Potassium, and Chloride • Establish the separation of electrical charge across neuron and muscle cell membranes • Maintain the body’s water balance and distribution • Maintain normal osmotic equilibrium and p. H • Maintain normal cardiac rhythm

Vitamins and Minerals Key Points • Vitamins perform numerous functions in our bodies and are essential for normal growth and development • Vitamins A, D, E, and K are fat soluble • B-complex vitamins, biotin, pantothenic acid, folate, and vitamin C are water soluble • Macrominerals are minerals of which we require >100 mg/day • Microminerals are those we require smaller amounts of (continued)

Vitamins and Minerals (continued) Key Points • Minerals are required for numerous physiological processes, including muscle contraction, oxygen transport, fluid balance, and bioenergetics • Vitamins and minerals do not appear to have any special performance-enhancing value • Taking them in amounts greater than RDA will not improve performance and may be dangerous

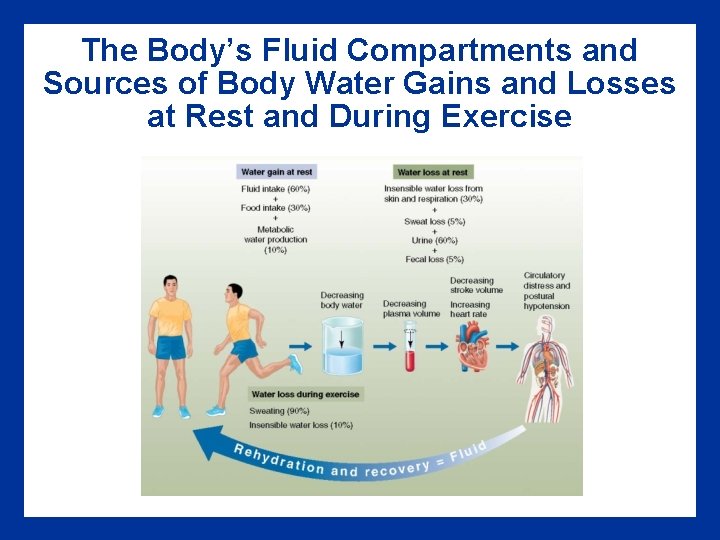

Water • Makes up ~60% of a young man’s and ~50% of a young woman’s total body weight • Intracellular fluid: water contained within our cells • Extracellular fluid: interstitial fluid surrounding the cells, blood plasma, lymph, and other body fluids • Regulates body temperature • Maintains blood pressure

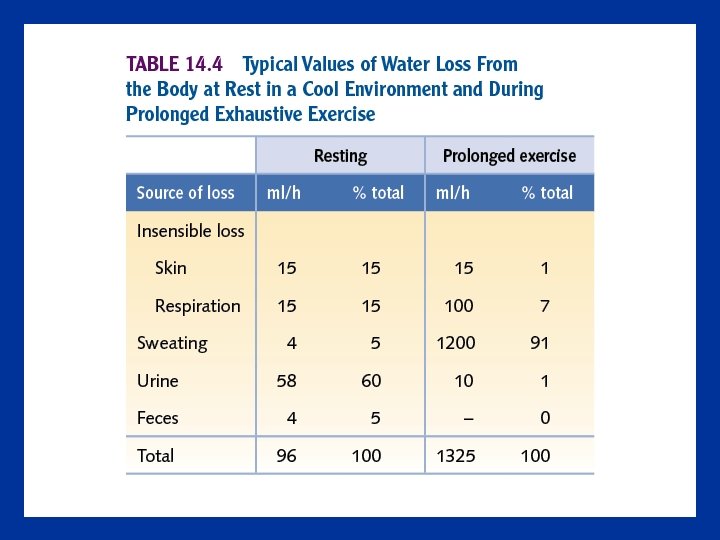

Water Balance at Rest • • • Water intake equals output Intake averages 33 ml/kg per day Avenues of water loss 1. Evaporation from the skin 2. Evaporation from the respiratory tract 3. Excretion from the kidneys 4. Excretion from the large intestines

Water Balance During Exercise • Water loss accelerates during exercise primarily due to increased sweating • Amount of sweat produced during exercise is determined by: – Environmental temperature, radiant heat load, humidity, and air velocity – Body size – Metabolic rate • During high-intensity exercise in the heat, water losses can be as much as 2 -3 L/hour

The Body’s Fluid Compartments and Sources of Body Water Gains and Losses at Rest and During Exercise

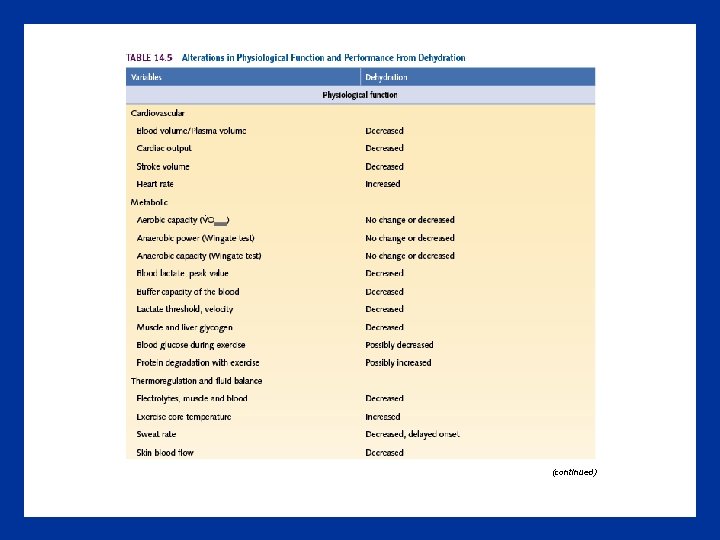

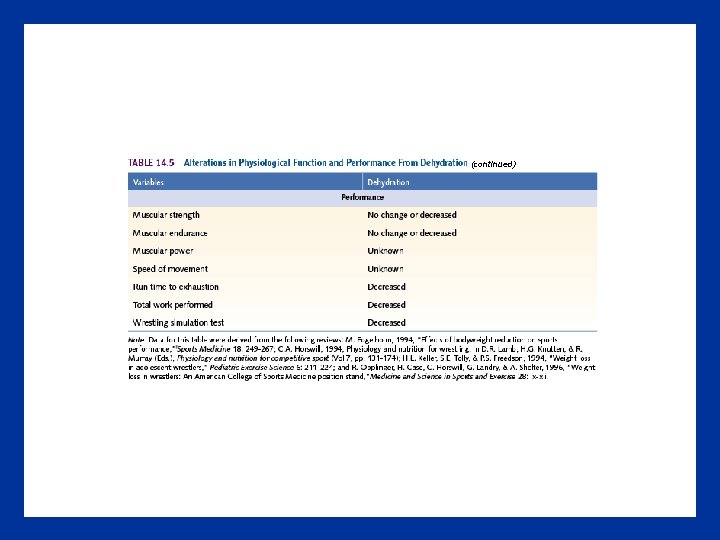

Dehydration and Performance: Decline in Running Velocity With Dehydration of About 2% of Body Weight Reprinted, by permission, from L. E. Armstrong, D. L. Costill, and W. J. Fink, 1985, "Influence of diuretic-induced dehydration on competitive running performance, " Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 17: 456 -461.

(continued)

(continued)

Water Balance During Exercise Key Points • Water balance depends on electrolyte balance • At rest, water intake equals water output • During exercise, metabolic water production increases as metabolic rate increases • Water losses during exercise increase because as heat in the body increases, more water is lost with increased sweating • Sweat becomes the primary avenue for water loss during exercise (continued)

Water Balance During Exercise (continued) Key Points • When dehydration reaches 2% of body weight, aerobic endurance performance is impaired • Heart rate and body temperature increase in response to dehydration

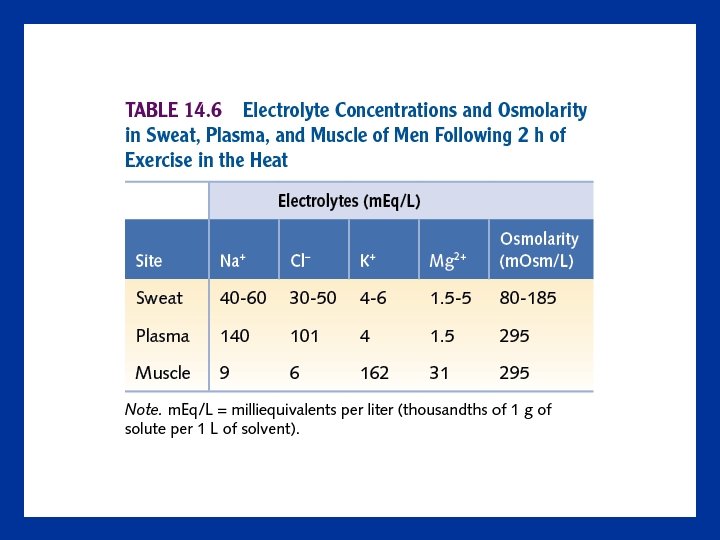

Electrolyte Balance During Exercise • Loss of large amounts of water can disrupt electrolyte balance • Electrolytes in sweat are rather dilute • Sodium and chloride are the most abundant electrolytes in sweat • Excess electrolytes are excreted in the urine during rest, but less so during exercise • Dehydration causes aldosterone to promote renal retention of sodium and chloride ions, increasing their concentrations in the blood • Increased blood osmolality triggers thirst in an effort to make us consume more fluid

Replacement of Body Fluid Losses • Thirst mechanism doesn’t precisely gauge the body’s state of dehydration • Benefits of fluids during exercise – Minimize dehydration – Minimize the increase in body temperature – Minimize cardiovascular stress – Helps prevent declines in performance

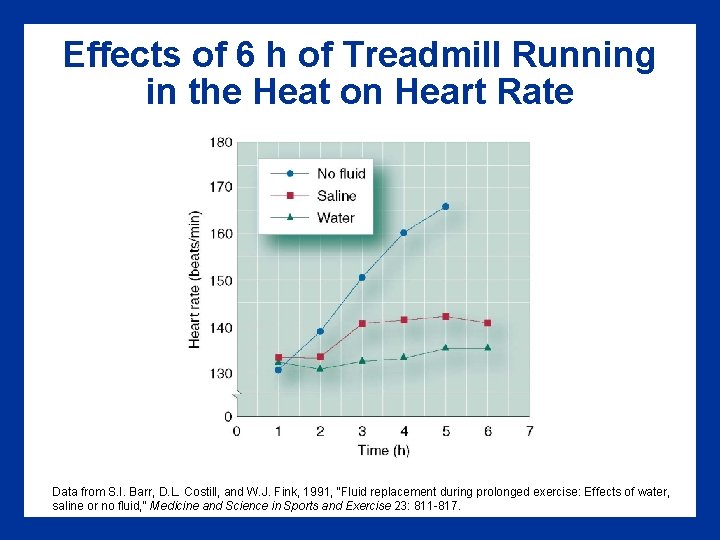

Effects of 6 h of Treadmill Running in the Heat on Heart Rate Data from S. I. Barr, D. L. Costill, and W. J. Fink, 1991, "Fluid replacement during prolonged exercise: Effects of water, saline or no fluid, " Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 23: 811 -817.

Hyponatremia • Serum Na+ concentrations below the normal range (135 -145 mmol/L) • Symptoms appear when serum sodium drops below 130 mmol/L • Early symptoms: bloating, puffiness, nausea, vomiting, headache • Later symptoms: confusion, disorientation, agitation, seizures, pulmonary edema, coma and death

Replacing Fluid Losses Key Points • The need to replace lost body fluids is greater than the need to replace electrolytes • The thirst mechanism does not exactly match the body’s hydration state, so more fluid should be consumed than thirst dictates • Water intake during prolonged exercise reduces the risk of dehydration and optimizes cardiovascular and thermoregulatory performance • In rare cases, drinking too much fluid with too little sodium has led to hyponatremia, which can cause confusion, disorientation, and seizures

The Athlete’s Diet: Vegetarian Diet • Types of vegetarian diets – Vegans – Lactovegetarians – Ovovegetarians • Athletes can get the nutrition they need with a strictly vegetarian diet as long as the foods they select include a balance of essential nutrients and calories • Adequate iron intake is of concern especially in women athletes

The Athlete’s Diet: Precompetition Meal • Ensures a normal blood glucose concentration and prevents hunger • Should contain 200 to 500 kcal and consist mainly of carbohydrates that are easily digestible (e. g. , cereal, milk, juice, toast) • Consumed no less than 2 hours before competition

Åstrand’s Glycogen Loading 1. Complete an exhaustive training bout 7 days before event 2. Eat fat and protein for next 3 days and reduce training load to deprive the muscles of carbohydrate and increase the activity of glycogen synthase 3. Eat a carbohydrate-rich diet for the remaining 3 days before event and reduce training load; because of increased glycogen synthase activity, more glycogen is stored

Sherman’s Glycogen Loading 7 Days Before Competition • Reduce training intensity • Eat a normal, healthy mixed diet with 55% carbohydrate 3 Days Before Competition • Reduce training to daily warm-up of 10 to 15 minutes • Eat a carbohydrate-rich diet

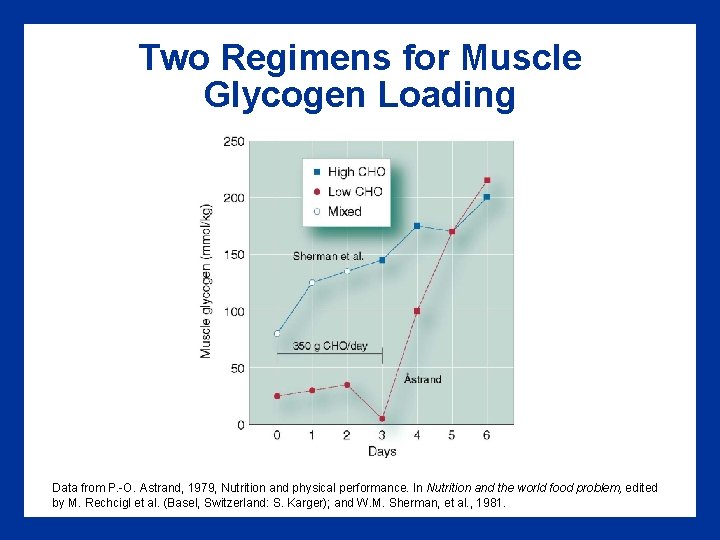

Two Regimens for Muscle Glycogen Loading Data from P. -O. Astrand, 1979, Nutrition and physical performance. In Nutrition and the world food problem, edited by M. Rechcigl et al. (Basel, Switzerland: S. Karger); and W. M. Sherman, et al. , 1981.

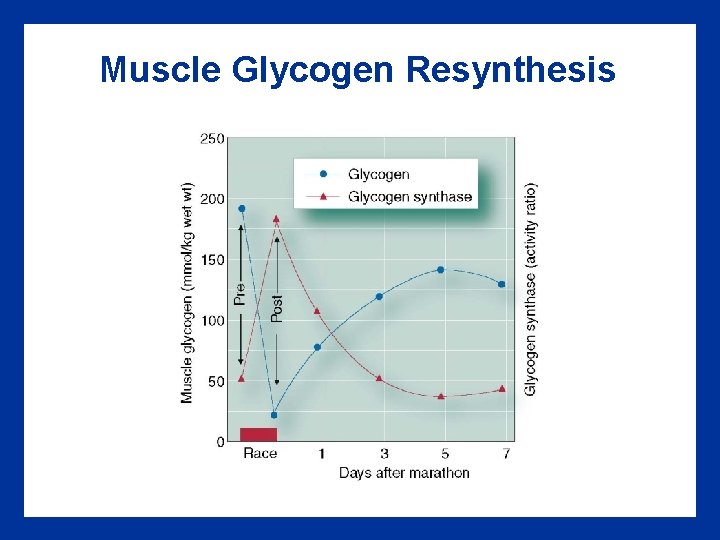

Muscle Glycogen Resynthesis

The Athlete’s Diet Key Points • For vegetarian athletes, careful consideration must be given to protein sources and consuming adequate levels of iron, zinc, calcium, and several vitamins • The precompetition meal should be taken no less than 2 h before competition and should be low in fat and high in carbohydrate • Carbohydrate loading increases muscle glycogen content • After endurance competition or training, it is important to consume carbohydrate to replace glycogen used during activity

Sport Drinks • Uniquely designed to meet both energy and fluid needs of athletes • Composition influences gastric emptying • Carbohydrate solutions empty more slowly • Most sports drinks contain: – 6 -8% CHO in the form of glucose and glucose polymers – 20 -60 mmol/L sodium • Adding glucose stimulates sodium and water absorption • Sodium increases thirst

Sport Drinks Key Points • Sport drinks have been shown to reduce the risk of dehydration and provide an important source of energy • Sport drinks can improve performance in both endurance athletes and in burst activities such as soccer and basketball • The inclusion of sodium in a sport drink facilitates the intake and storage of water • Taste is an important factor when one is considering a sport drink

- Slides: 92