Chapter 13 Automatic adjustment with flexible and fixed

Chapter 13 Automatic adjustment with flexible and fixed exchange rates

13. 1 Introduction In this chapter, we examine how a deficit in a nation’s balance of payments is automatically corrected by price and income changes in the nation and abroad (The opposite would be the case for a trade surplus). For simplicity we assume that international private capital flows take place as passive responses to cover (i. e. , to pay for or finance) temporary trade imbalance, so that a balance-of-payments deficit refers to or is synonymous with a trade deficit.

Continued: 13. 1 Introduction Adjustments to a balance-of-payments or trade deficit can take place automatically through price or income changes, or both, under a flexible or a fixed exchange rate system.

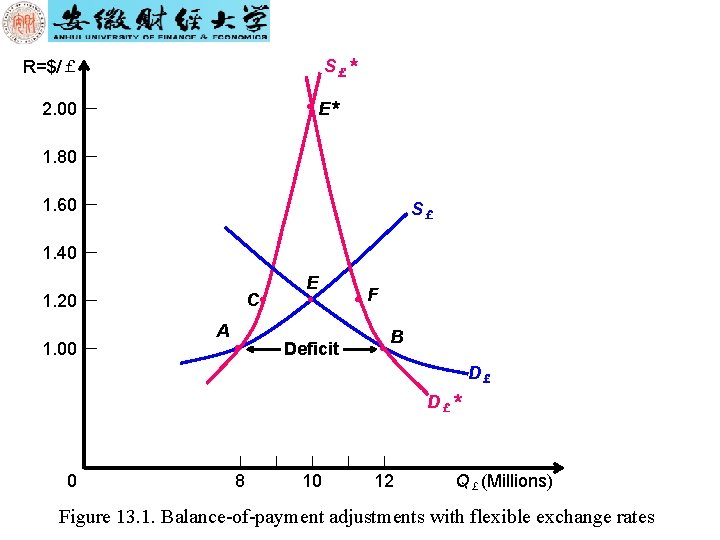

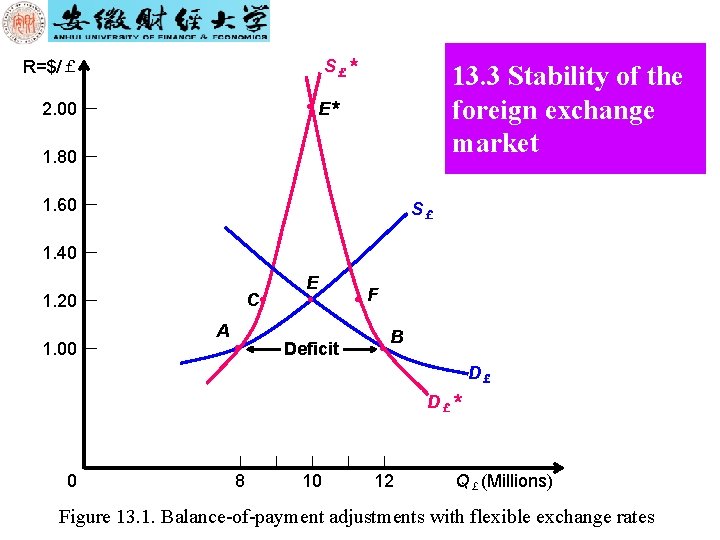

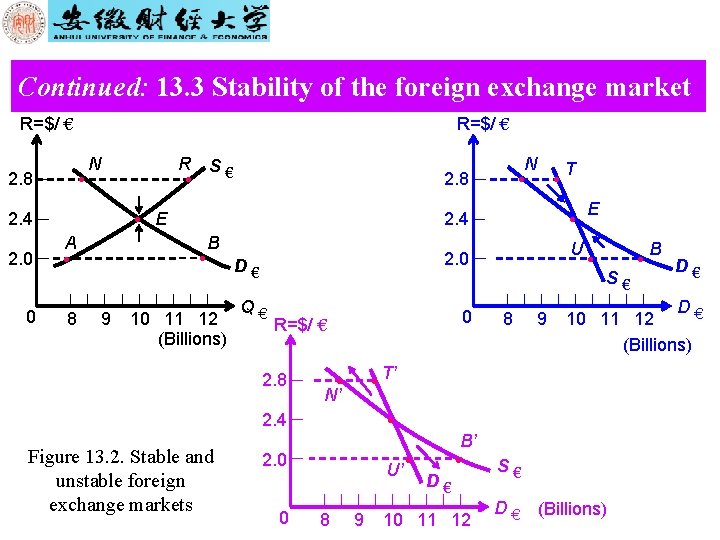

13. 2 Adjustment with flexible exchange rates Main content of the section: The process by which a balance of payments or trade deficit is corrected automatically by a depreciation of the nation’s currency. This is shown in Figure 13. 1

S£* R=$/£ 2. 00 ● E* 1. 80 1. 60 S£ 1. 40 C● 1. 20 1. 00 A ● E ● Deficit ● F ● B D£ D£* 0 8 10 12 Q£(Millions) Figure 13. 1. Balance-of-payment adjustments with flexible exchange rates

Continued: 13. 2 Adjustment with flexible exchange rates Such a huge depreciation of the dollar would make the dollar-price of the U. S. imports very high and lead to inflation in the United States, which might be an even greater problem than the trade deficit. Specifically, while a depreciation of the dollar makes U. S. products cheaper to EMU residents (because they need fewer euros to get each dollar), U. S. residents will find imports more expensive (because they need more dollars to get each euro) and this may lead to an inflation problem for the United States If the U. S. demand supply curves for euros are steep or inelastic. Thus, it is very important to determine how elastic D£ and S£ are.

Continued: 13. 2 Adjustment with flexible exchange rates The U. S. demand curve for euros (D£) in figure 13. 1 is derived from the demand supply curves of U. S. imports in terms of euros, while the U. S. supply curve for euros (S£) is derived from the foreign demand supply curves for U. S. exports in terms of euros. The more elastic are the U. S. demand for imports (DM) and the foreign demand for U. S. exports (DX) in terms of euros, the more elastic are D£ and S£(and the less inflationary a depreciation would be to correct a U. S. trade deficit) (图 13. 1中,美国对于欧元的需求 曲线可以由以欧元表示的美国对于进口品的需求和供给曲线推 导出来;而美国对于欧元的供给曲线可以由以欧元表示的美国 对于出口品的需求和供给曲线推导出来。美国对于以欧元表示 的进口需求和出口需求弹性越大,则欧元的需求和供给弹性越 大)

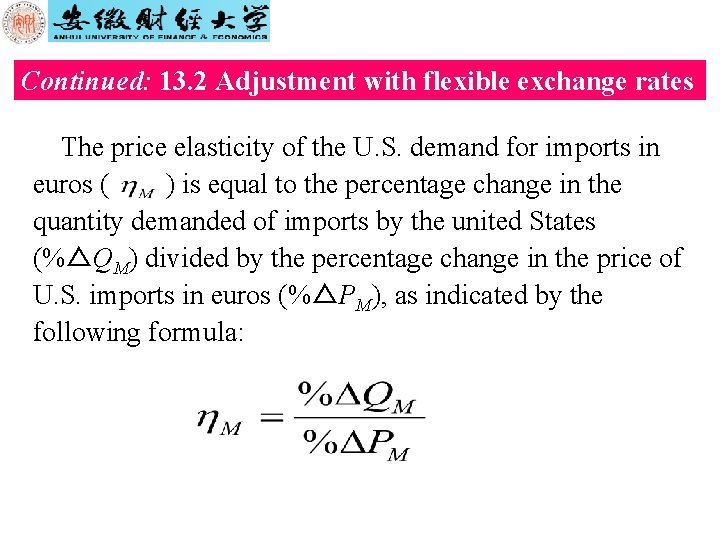

Continued: 13. 2 Adjustment with flexible exchange rates The price elasticity of the U. S. demand for imports in euros ( ) is equal to the percentage change in the quantity demanded of imports by the united States (%△QM) divided by the percentage change in the price of U. S. imports in euros (%△PM), as indicated by the following formula:

Continued: 13. 2 Adjustment with flexible exchange rates Similarly, the price elasticity of the foreign demand for U. S. exports in euros ( ) is given by the percentage change in the quantity demanded of U. S. exports by foreigners (%△QX) divided by the percentage change in the price of U. S. exports in euros (%△PX), in euros; that is:

Continued: 13. 2 Adjustment with flexible exchange rates Since quantity and prices always move in opposite directions (i. e. , an increase in price leads to a reduction in the quantity, and vice versa, as dictated by the law of demand), and are always negative.

Continued: 13. 2 Adjustment with flexible exchange rates However, in comparing price elasticities we use their absolute values and say that demand is elastic, inelastic, or unitary elastic, respectively, if the absolute value of. When demand is elastic, a reduction in price leads to a larger proportionate increase in the quantity demanded so that expenditures on the commodity increase. If demand is inelastic, we have the opposite situation. When demand is unitary elastic, a change in price will leave expenditures on the commodity unchanged.

S£* R=$/£ 2. 00 ● 13. 3 Stability of the foreign exchange market E* 1. 80 1. 60 S£ 1. 40 C● 1. 20 1. 00 A ● E ● Deficit ● F ● B D£ D£* 0 8 10 12 Q£(Millions) Figure 13. 1. Balance-of-payment adjustments with flexible exchange rates

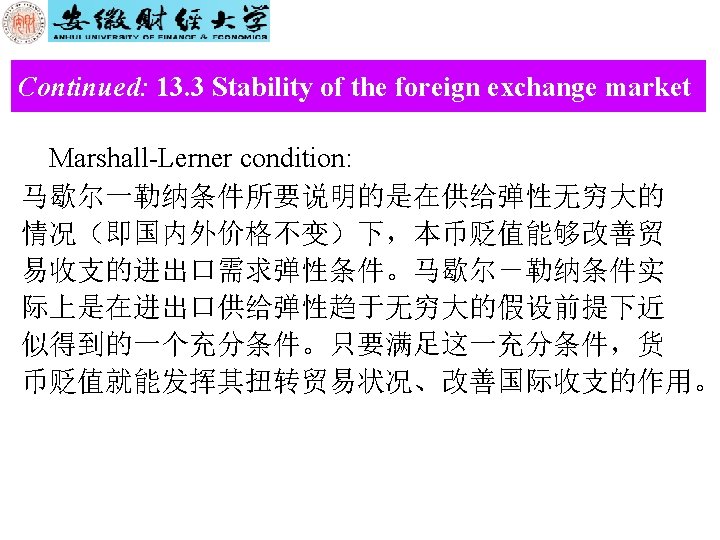

Continued: 13. 3 Stability of the foreign exchange market R=$/ € 2. 8 R=$/ € ● N 2. 4 2. 0 0 R S€ ● ● A 8 9 2. 8 E ● ● B 10 11 12 (Billions) D€ Q€ T E ● 2. 0 U● 0 ● S€ 8 9 N’ ● B’ 2. 0 U’ 8 9 ● ● D€ 10 11 12 S€ D€ B D€ D€ 10 11 12 (Billions) ● T’ ● 2. 4 0 ● 2. 4 R=$/ € 2. 8 Figure 13. 2. Stable and unstable foreign exchange markets N ● (Billions)

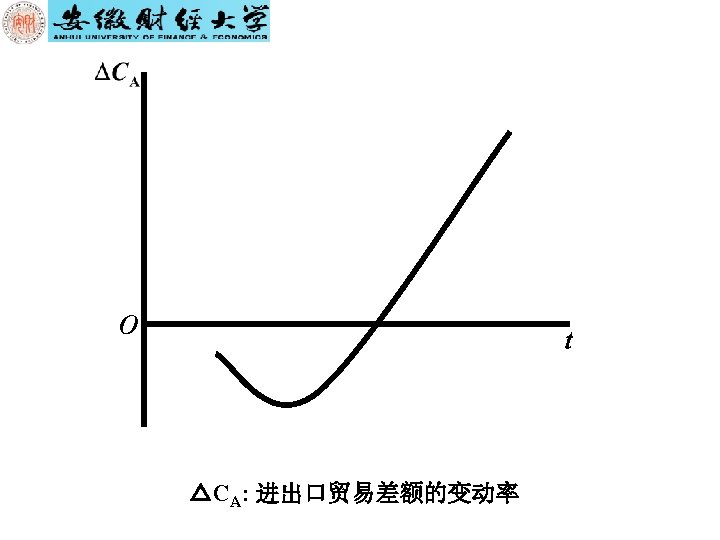

Continued: 13. 3 Stability of the foreign exchange market J-curve effect: The deterioration before a net improvement in a country’s trade balance resulting from a depreciation or devaluation.

13. 5 Income determination in a closed economy The flexible exchange rate rely on automatic price adjustments to bring about equilibrium in a nation’s balance of payments. But changes in a nation’s balance of payments affect national income at home and abroad and these, in turn, affect the nation’s balance of payments.

Continued: 13. 5 Income determination in a closed economy For example, an increase in a nation’s exports leads to an increase in production and income in the nation, which induces imports to rise, thus reversing some of the improvement in the nation’s balance of payments that resulted from the increase in its exports. We now want to consider how these automatic income adjustments contribute to balance of payments adjustments. This represents the extension of Keynesian economics to the open economy.

Continued: 13. 5 Income determination in a closed economy 1. ★To examine how automatic income adjustments operate we assume that all prices (exchange rates, interest rates, wages, as well as consumer prices) remain constant. ★To study how the automatic income adjustment mechanism operates in an open economy (i. e. , an economy open to world trade and finance), we begin by reviewing how the equilibrium level of national income is determined in a closed economy without a government sector.

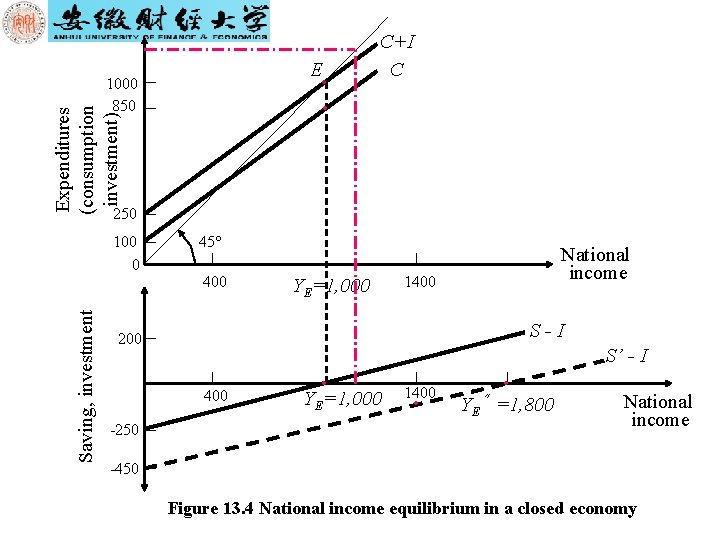

Continued: 13. 5 Income determination in a closed economy 2. Equilibrium level of income (YE) The level of income at which desired or planned expenditures equal the value of output, and desired saving equals desired investment. In a closed economy without a government sector, the equilibrium level of income is determined where income (Y) is equal to desired or planned consumption expenditures (C) plus desired or planned business investment (I). Since income (Y) is partly spent on consumption (C) and partly saved (S), we can indicate the equilibrium level of income by: Y=C+S=C+I So that S=I and S-I=0

E● 1000 850 C+I C Expenditures (consumption investment) ● 250 Saving, investment 100 0 45° 400 YE=1, 000 National income 1400 S-I 200 S’ - I 400 -250 ● YE=1, 000 1400 ● ● YE〞=1, 800 National income -450 Figure 13. 4 National income equilibrium in a closed economy

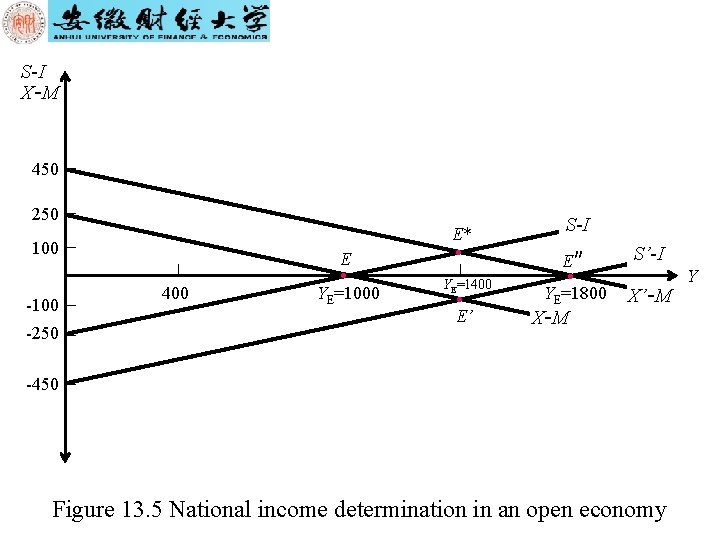

13. 6 Income determination in an open economy In an open economy (i. e. , an economy open to international trade and finance), the nation’s imports rise as income rises. For example, as the U. S. economy grows it requires more petroleum imports. The increase in imports induced per dollar increase in income is called the marginal propensity to import (m).

Continued: 13. 6 Income determination in an open economy Imports, like savings, are leakages out of the system because they do not stimulate domestic production. On the other hand, exports like investment, are an injection in to the system because they stimulate production and the generation of income in the nation. The equilibrium level of income in an open economy is where total leakages (S+M) equal total injections (I+X); that is, where S+M=I+X

Continued: 13. 6 Income determination in an open economy With a change in the economy (such as an autonomous increase in investment or exports), the equilibrium conditions becomes △S+△M=△I+△X

Continued: 13. 6 Income determination in an open economy In our analysis, we assume that exports, like investment, are autonomous and do not change with the level of income in a nation, while imports and savings are functionally related to income (i. e. , rise as national income rises). The change in the amount of savings and imports induced by a change in income in the nation are by △S=△Y And △M=m△Y

Continued: 13. 6 Income determination in an open economy We can now use this information to derive the foreigntrade multiplier for an autonomous increase in investment or exports in the nation. Substituting the above values for △S and △M into the equilibrium condition after a change has occurred in the nation, we get s△Y+m△Y=△I+△X or (s+m)△Y=△I+△X Assuming for the moment that △I >0 but △X =0,

Continued: 13. 6 Income determination in an open economy we get the foreign-trade multiplier (K’) for an autonomous change in investment in the nation of With a change in the nation’s exports rather than investment, the foreign trade multiplier, k’, would be the same because exports stimulate the domestic production, just like an increase in investment. That is,

Continued: 13. 6 Income determination in an open economy Summary: foreign trade multiplier (k’) is the ratio of the change in income to the change in exports and/or investment. It equals k’=1/(MPS+MPM) For example, if s=0. 25 and m=0. 25, then k’ is

Continued: 13. 6 Income determination in an open economy This means that each autonomous dollar increase in either investment or exports in the nation leads to a two-dollar increase in its income. Note that with the additional leakage of M, k’<k. Thus, if I increases by 200, the equilibrium level of income increases by △Y=k’(△I)=2(200)=400 This 400 increase in the equilibrium level of income induces and increase in savings and imports in the nation of △S=s△Y=0. 25(400)=100 And △M=m△Y=0. 25(400)=100

S-I X -M 450 250 E* 100 E ● -100 -250 400 YE=1000 ● YE=1400 ● E’ S-I E″ S’-I YE=1800 X’-M ● X -M -450 Figure 13. 5 National income determination in an open economy Y

13. 8 Absorption approach We now extend our analysis by combining or integrating the automatic price and income adjustment mechanisms and examining the so-called absorption approach. specifically, we examine the effect of induced (automatic) income changes in the process of correcting a deficit in the nation’s balance of payments through a depreciation of the nation’s currency.

Continued: 13. 8 Absorption approach We saw in Section 13. 2 and 13. 3 that a nation can correct a deficit in its balance of payments by allowing its currency to depreciate (if the foreign exchange market is stable). Because the improvement in the nation’s trade balance depends on the price elasticity of demand for its exports and imports, this method of correcting a deficit is referred to as the elasticity approach. The improvement in the deficit nation’s trade balance arises because depreciation stimulates the nation’s exports and discourages its imports (thus encouraging the domestic production of import substitutes).

Continued: 13. 8 Absorption approach However, if the deficit nation is already at full employment, production cannot rise. Then, only if real domestic absorption (i. e. , expenditures) is reduced will the depreciation eliminate or reduce the deficit in the nation’s balance of payments. If real domestic absorption is not reduced, the depreciation will only lead to an increase in domestic prices that will completely neutralize the competitive advantage conferred on the nation by the depreciation, with no reduction of its trade deficit.

Continued: 13. 8 Absorption approach This analysis was first introduced in 1951 by Sidney Alexanger, who named it the absorption approach. Alexander began with the identity that production or income (Y) is equal to consumption (C) plus domestic investment (I) plus the trade balance or net exports (X-M), all in real terms. That is, Y=C+I+(X-M) But then letting A equal domestic absorption (C+I) and B equal the trade balance (X-M), we have Y=A+B

Continued: 13. 8 Absorption approach By subtracting A from both sides, we get Y-A=B That is, domestic production or income minus domestic absorption equals the trade balance. For the trade balance (B) to improve as a result of depreciation, Y must rise and/or A must fall. If the nation is at full employment to begin with, production or real income (Y) cannot rise, and depreciation can be effective only if domestic absorption (A) falls.

Continued: 13. 8 Absorption approach A depreciation of the deficit nation’s currency automatically reduces domestic absorption if (1) it redistributes income from wages to profits (since profits earners usually have a higher marginal propensity to save than wages earners), (2) the increase in domestic prices resulting from the depreciation reduces wealth and hence expenditures in the nation, and (3) inflation pushes people into higher tax brackets and reduces consumption.

- Slides: 36