Chapter 11 Time and global states Outline Introduction

Chapter 11 Time and global states

Outline �Introduction �Clocks, events and process states �Synchronizing physical clocks �Logical time and logical clocks

introduction �The importance of time: �Time is a quantity we often want to measure accurately. (e. g. e-commerce) �Algorithms that depend upon clock synchronization have been developed for several problems in distribution: 1. Maintaining the consistency of distributed data 2. Checking the authenticity of request sent to server 3. Eliminating the processing of duplicate updates

introduction �Important facts : �Two events that are judged to be simultaneous in one frame of reference are not necessarily simultaneous according to observers in other frames of references that are moving relative to it. �The relative order of two events can even be reversed for two different observers. But this cannot happen if one event could have caused the other to occur. �The notion of physical time is also problematic in a DS because of the limitation in our ability to timestamp events at different nodes sufficiently accurately to know the order in which any pair of events occurred, or whether they occurred simultaneously

Clocks, events and process states �£ �A collection of N processes pi, i = 1, 2, . . N �si �The state of pi �E. g. variables �Actions of pi �Operations that transform pi’s state �Send or receive message between pj

Clocks, events and process states �e �Event: occurrence of a single action � i �occur before in pi , e. g. e i e` �Total order of events in pi �history(pi ) = hi �hi = <ei 0, ei 1, ei 2, …>

Clock in computer �A device that count oscillations occurring in a crystal at a definite frequency �Hardware time: Hi(t) �The counts of oscillation since an original point � Software time: will Ci(t) = Hi(t)+ v Successive events correspond to different �Timestamp anclock event timestamps only ifofthe resolution is smaller than the time interval between successive events. v. The rate at which events occur depends on such factor as the length of the processor instruction cycle

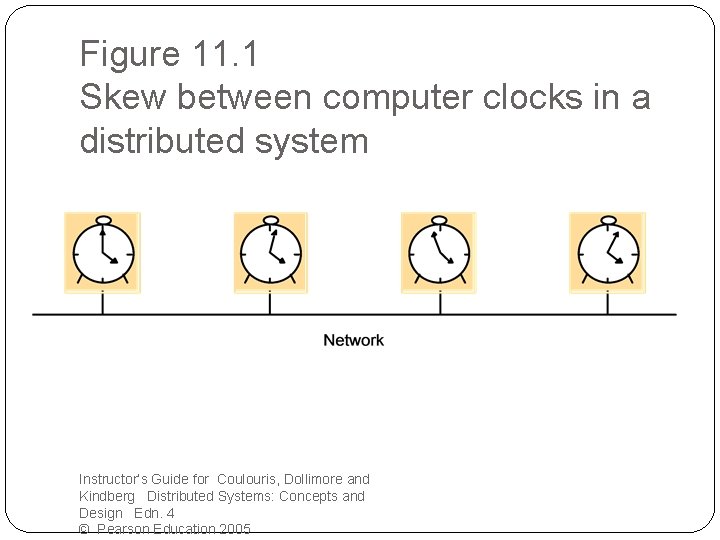

Clock skew and clock drift �Crystal oscillate at different rate �Clock drift can not be avoided �Clock skew �The instantaneous difference between the readings of any two clocks

Figure 11. 1 Skew between computer clocks in a distributed system Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Pearson Education 2005

Astronomical Time &International Atomic Time �Rotation of earth on its axis and about the Sun �Days, Years, etc �Second is 1/86400 astronomical time �Standard second �Atomic oscillator �Drift rate: one part in 1013

Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) �shift between astronomical time and atomic time �The period of the Earth’s rotation about its axis is gradually getting longer �Tidal friction, atmospheric effects, etc �Leap second �Atomic time which is inserted a leap second occasionally to keep in step with astronomical time �Broadcast UTC to the World �E. g. , by GPS or WWV

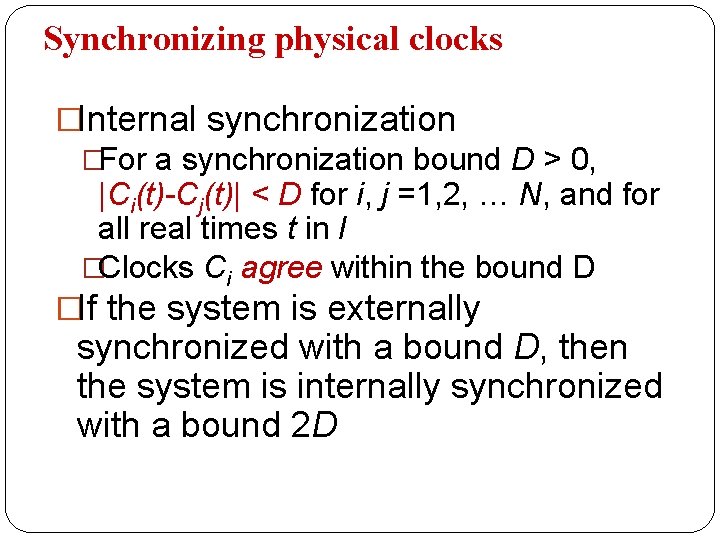

Synchronizing physical clocks �Ci : pi’s clock �I: an interval of real time �External synchronization �For a synchronization bound D > 0, and for a source S of UTC time, |S(t)-Ci(t)| < D, for i = 1, 2, … N and for all real times t in I �Clocks Ci are accurate to within the bound D

Synchronizing physical clocks �Internal synchronization �For a synchronization bound D > 0, |Ci(t)-Cj(t)| < D for i, j =1, 2, … N, and for all real times t in I �Clocks Ci agree within the bound D �If the system is externally synchronized with a bound D, then the system is internally synchronized with a bound 2 D

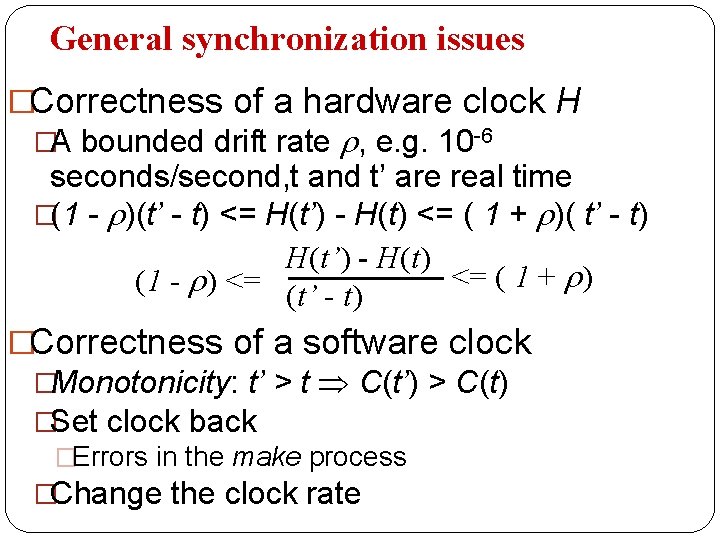

General synchronization issues �Correctness of a hardware clock H �A bounded drift rate , e. g. 10 -6 seconds/second, t and t’ are real time �(1 - )(t’ - t) <= H(t’) - H(t) <= ( 1 + )( t’ - t) H(t’) - H(t) <= ( 1 + ) (1 - ) <= (t’ - t) �Correctness of a software clock �Monotonicity: t’ > t C(t’) > C(t) �Set clock back �Errors in the make process �Change the clock rate

General synchronization issues (2) �Clock failures �Crash failure: stop ticking �Arbitrary failure, e. g. Y 2 K bug

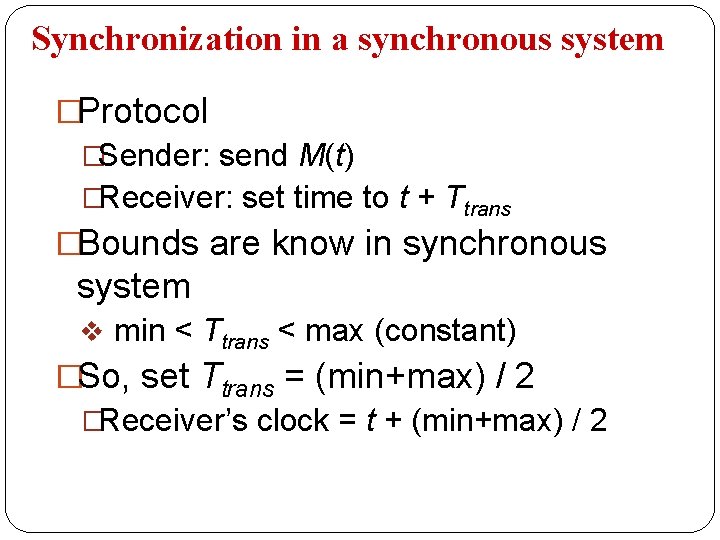

Synchronization in a synchronous system �Protocol �Sender: send M(t) �Receiver: set time to t + Ttrans �Bounds are know in synchronous system v min < Ttrans < max (constant) �So, set Ttrans = (min+max) / 2 �Receiver’s clock = t + (min+max) / 2

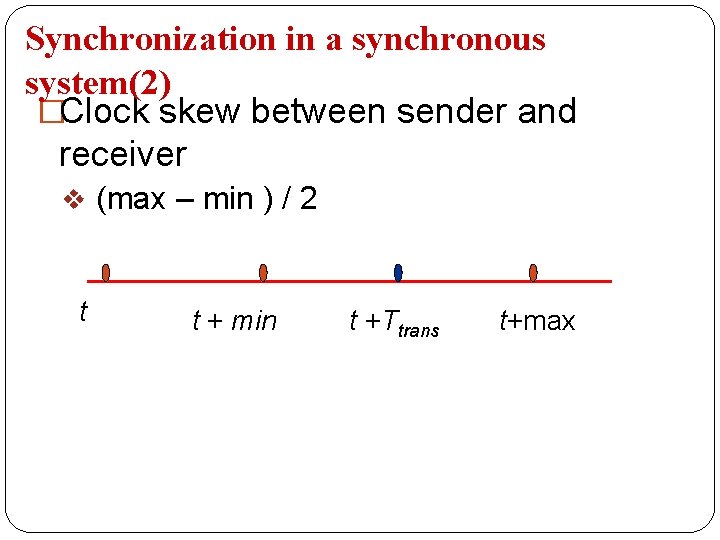

Synchronization in a synchronous system(2) �Clock skew between sender and receiver v (max – min ) / 2 t t + min t +Ttrans t+max

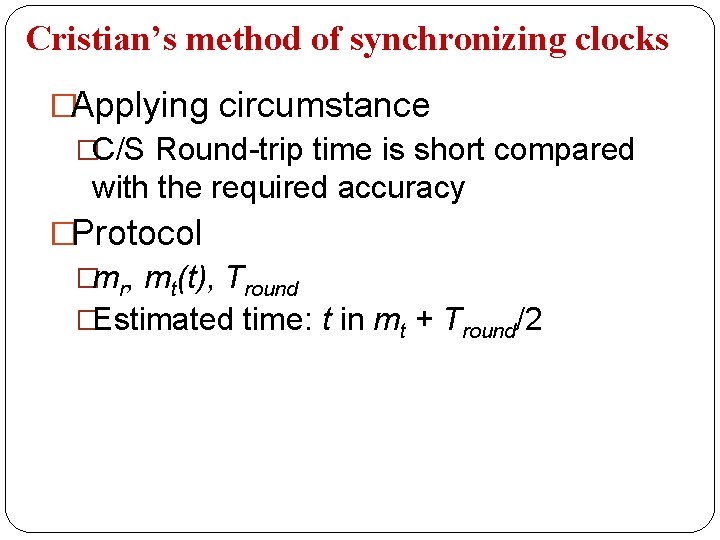

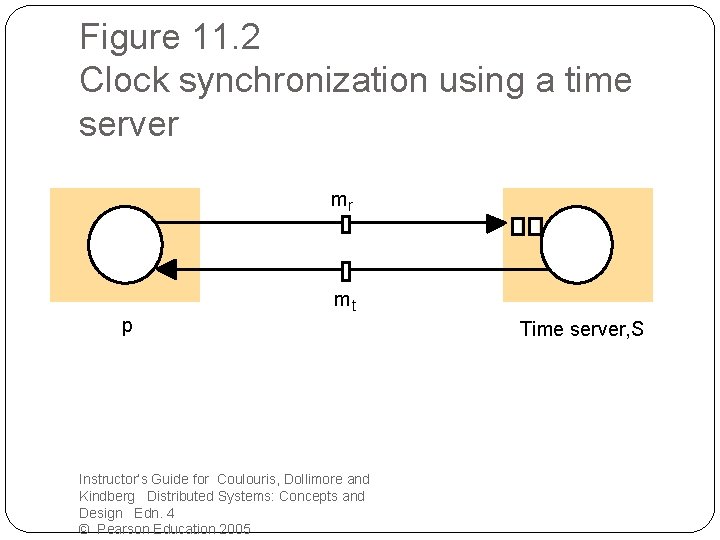

Cristian’s method of synchronizing clocks �Applying circumstance �C/S Round-trip time is short compared with the required accuracy �Protocol �mr, mt(t), Tround �Estimated time: t in mt + Tround/2

Figure 11. 2 Clock synchronization using a time server mr p mt Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Pearson Education 2005 Time server, S

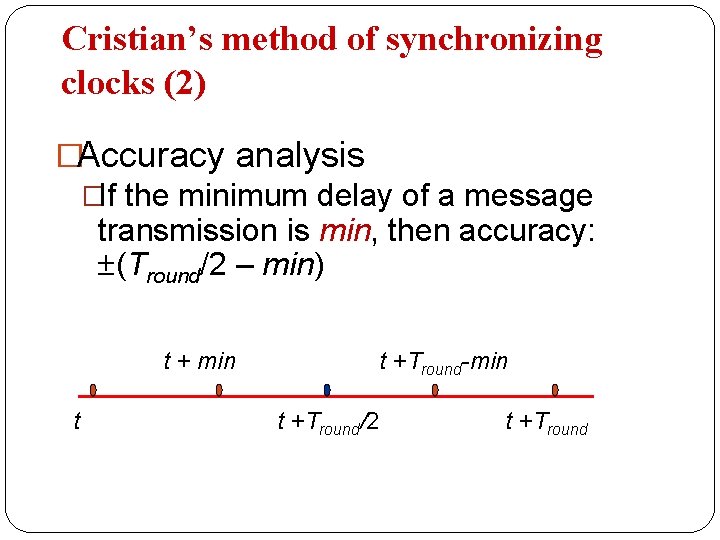

Cristian’s method of synchronizing clocks (2) �Accuracy analysis �If the minimum delay of a message transmission is min, then accuracy: (Tround/2 – min) t + min t t +Tround-min t +Tround/2 t +Tround

The Berkeley algorithms � Internal synchronization 1. The master polls the slaves’ clocks 2. The master estimates the slaves’ clocks by round-trip time � Similar to Christian’s algorithm 3. The master averages the slaves’ clock values � Cancel out the individual clock’s tendencies to run fast or slow

The Berkeley algorithms (2) 4. The master sends back to the slaves the amount that the slaves’ clocks should adjust by � Positive or negative value � Avoid further uncertainty due to the message transmission time � Slave adjust its clock

Design aims of Network Time Protocol �External synchronization �Enable clients across the Internet to be synchronized accurately to UTC �Reliability �Can survive lengthy losses of connectivity �Redundant server & redundant path between servers

Design aims of Network Time Protocol (2) �Scalability �Enable clients to resynchronize sufficiently frequently to offset the rates of drift found in most computers �Security �Protect against interference with the time service

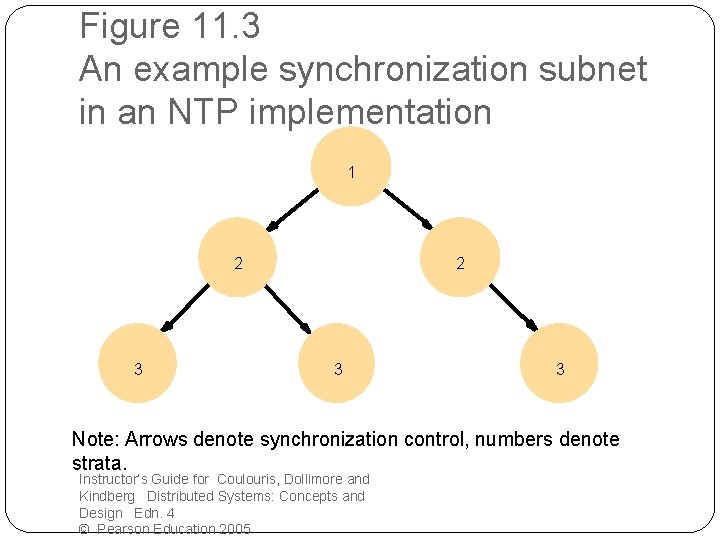

Figure 11. 3 An example synchronization subnet in an NTP implementation 1 2 3 3 Note: Arrows denote synchronization control, numbers denote strata. Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Pearson Education 2005

Synchronization measures �Multicast mode �Intend for use on a high speed LAN �Assuming a small delay �Low accuracy but efficient �Procedure-call mode �Similar to Christian’s �Higher accuracy than multicast �Symmetric mode �The highest accuracy

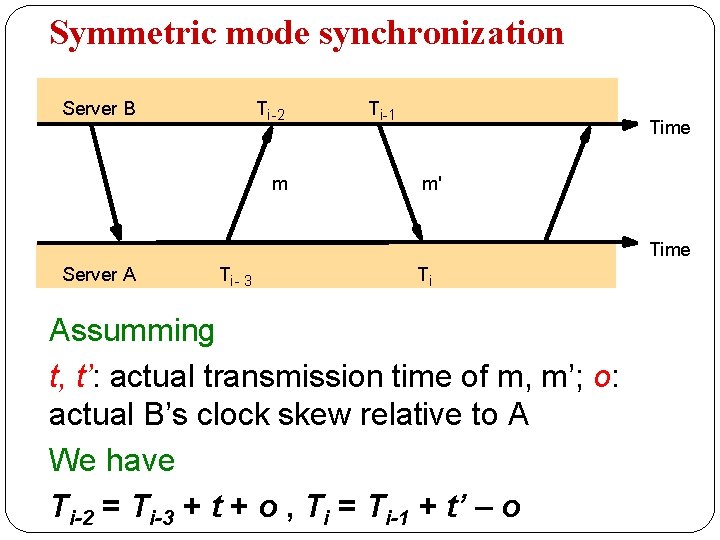

Symmetric mode synchronization Server B Ti-2 m Ti-1 Time m' Time Server A Ti- 3 Ti Assumming t, t’: actual transmission time of m, m’; o: actual B’s clock skew relative to A We have Ti-2 = Ti-3 + t + o , Ti = Ti-1 + t’ – o

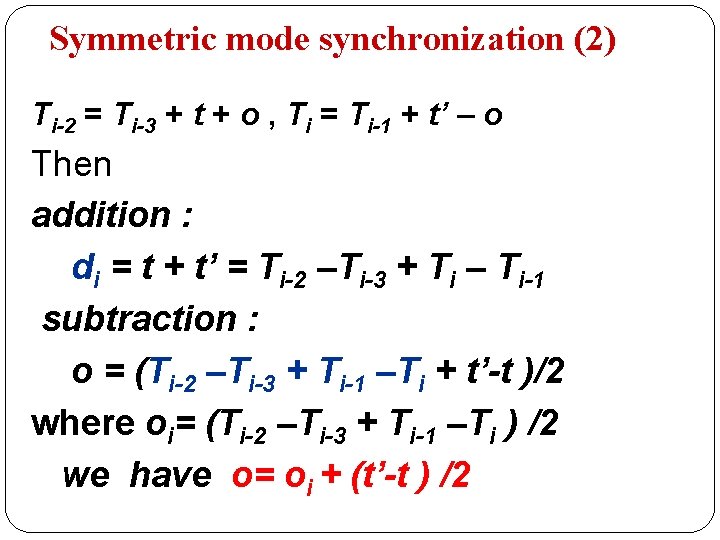

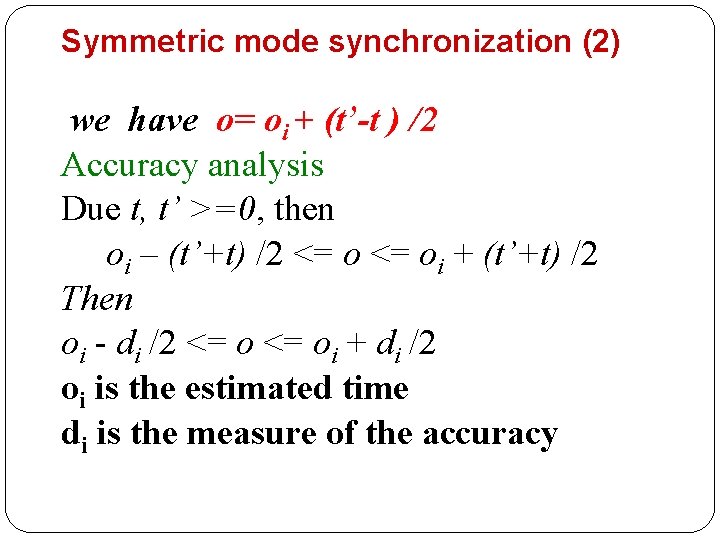

Symmetric mode synchronization (2) Ti-2 = Ti-3 + t + o , Ti = Ti-1 + t’ – o Then addition : di = t + t’ = Ti-2 –Ti-3 + Ti – Ti-1 subtraction : o = (Ti-2 –Ti-3 + Ti-1 –Ti + t’-t )/2 where oi= (Ti-2 –Ti-3 + Ti-1 –Ti ) /2 we have o= oi + (t’-t ) /2

Symmetric mode synchronization (2) we have o= oi + (t’-t ) /2 Accuracy analysis Due t, t’ >=0, then oi – (t’+t) /2 <= oi + (t’+t) /2 Then oi - di /2 <= oi + di /2 oi is the estimated time di is the measure of the accuracy

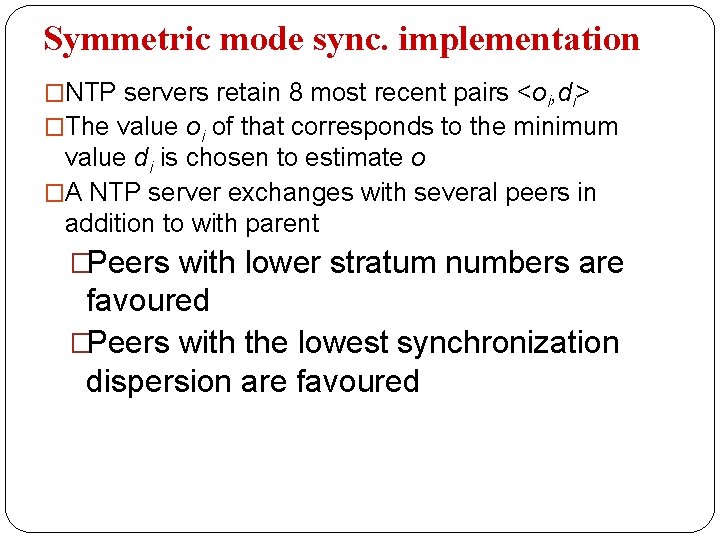

Symmetric mode sync. implementation �NTP servers retain 8 most recent pairs <oi, di> �The value oi of that corresponds to the minimum value di is chosen to estimate o �A NTP server exchanges with several peers in addition to with parent �Peers with lower stratum numbers are favoured �Peers with the lowest synchronization dispersion are favoured

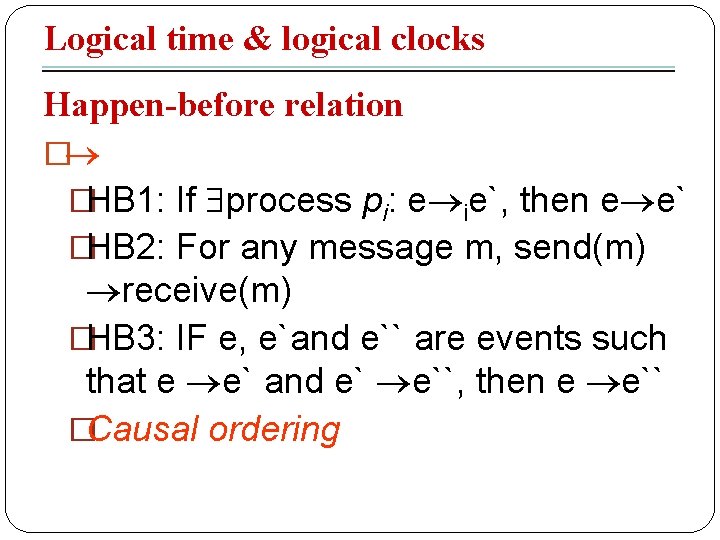

Logical time & logical clocks Happen-before relation � �HB 1: If process pi: e ie`, then e e` �HB 2: For any message m, send(m) receive(m) �HB 3: IF e, e`and e`` are events such that e e` and e` e``, then e e`` �Causal ordering

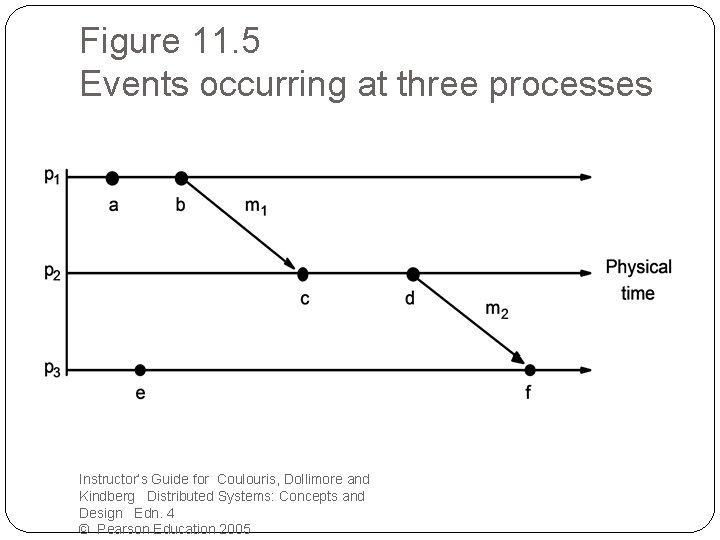

Happen-before relation �Example �a || e �Shortcomings �Not suitable to processes collaboration that does not involve messages transmission �Capture potential causal ordering

Figure 11. 5 Events occurring at three processes Instructor’s Guide for Coulouris, Dollimore and Kindberg Distributed Systems: Concepts and Design Edn. 4 © Pearson Education 2005

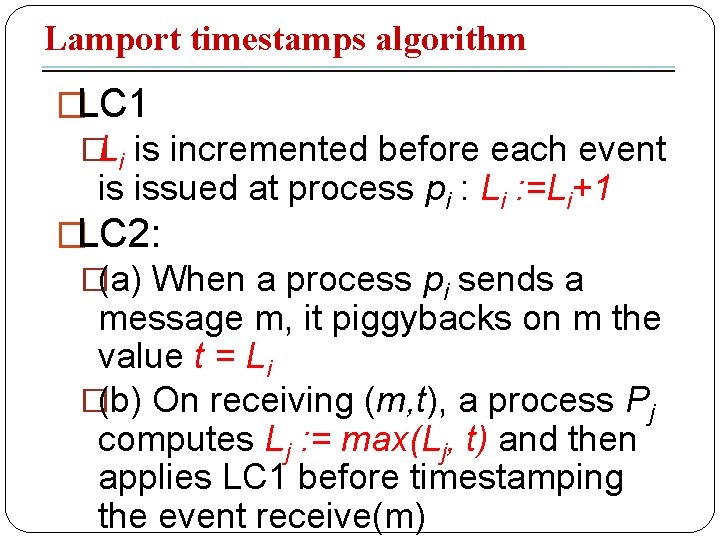

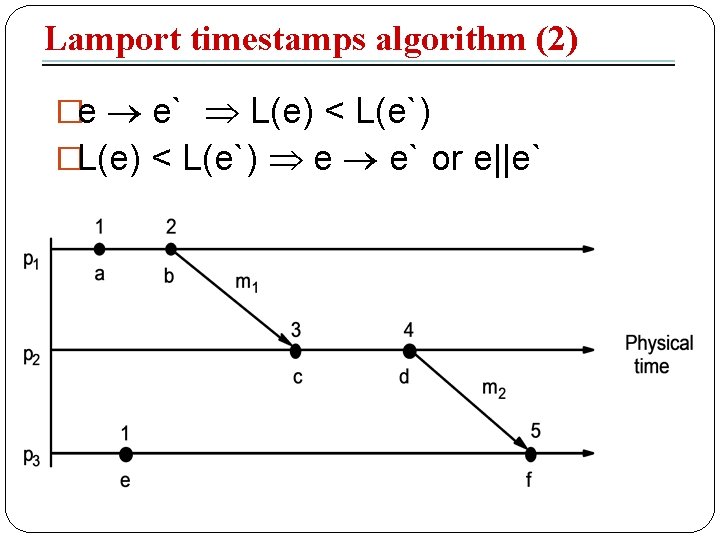

Lamport timestamps algorithm �LC 1 �Li is incremented before each event is issued at process pi : Li : =Li+1 �LC 2: �(a) When a process pi sends a message m, it piggybacks on m the value t = Li �(b) On receiving (m, t), a process Pj computes Lj : = max(Lj, t) and then applies LC 1 before timestamping the event receive(m)

Lamport timestamps algorithm (2) �e e` L(e) < L(e`) �L(e) < L(e`) e e` or e||e`

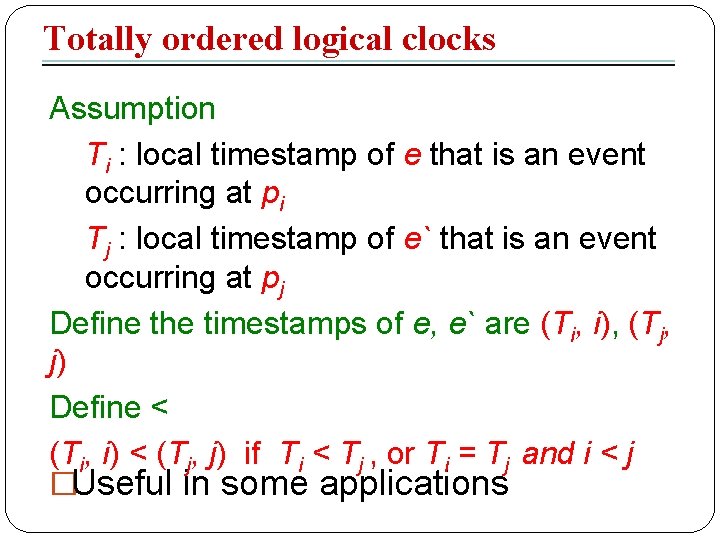

Totally ordered logical clocks Assumption Ti : local timestamp of e that is an event occurring at pi Tj : local timestamp of e` that is an event occurring at pj Define the timestamps of e, e` are (Ti, i), (Tj, j) Define < (Ti, i) < (Tj, j) if Ti < Tj , or Ti = Tj and i < j �Useful in some applications

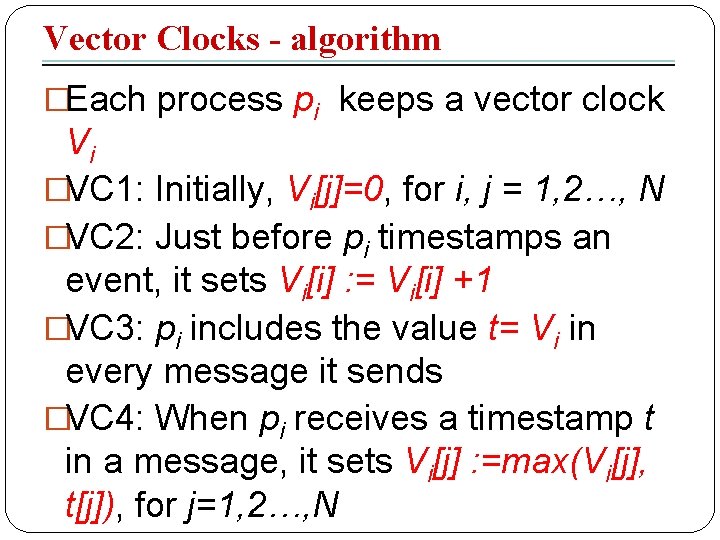

Vector Clocks - algorithm �Each process pi keeps a vector clock Vi �VC 1: Initially, Vi[j]=0, for i, j = 1, 2…, N �VC 2: Just before pi timestamps an event, it sets Vi[i] : = Vi[i] +1 �VC 3: pi includes the value t= Vi in every message it sends �VC 4: When pi receives a timestamp t in a message, it sets Vi[j] : =max(Vi[j], t[j]), for j=1, 2…, N

![Vector Clocks - significance �Compare vector timestamps �V = V` iff V [j] = Vector Clocks - significance �Compare vector timestamps �V = V` iff V [j] =](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/aaa7307b1c43a8ec3349e75e7e4f06b1/image-38.jpg)

Vector Clocks - significance �Compare vector timestamps �V = V` iff V [j] = V`[j] for j = 1, 2…, N �V <= V` iff V [j]<=V`[j] for j = 1, 2…, N �V < V` iff V [j]< V`[j] for j = 1, 2…, N �Otherwise V<> V` �V(e) < V(e`) e e`, V(e) <> V(e`) e||e`

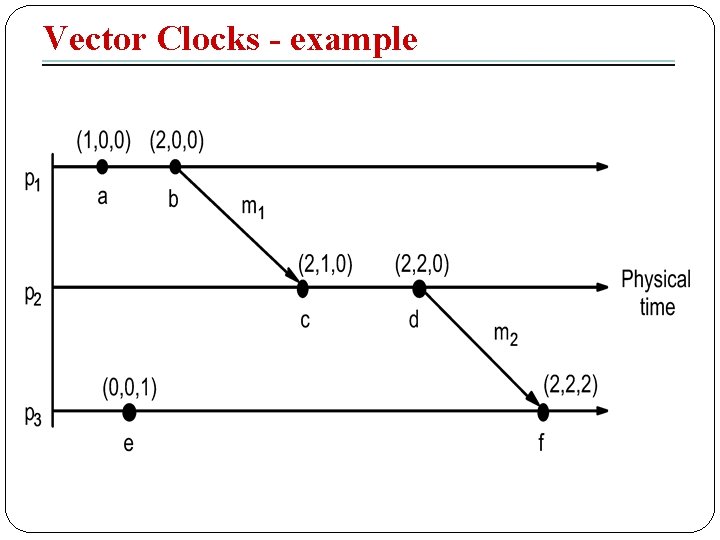

Vector Clocks - example

- Slides: 39