Chapter 10 LongTerm Assets Belverd E Needles Jr

Chapter 10 Long-Term Assets Belverd E. Needles, Jr. Marian Powers -----Multimedia Slides by: Dr. Howard A. Kanter, CPA De. Paul University Milton M. Pressley University of New Orleans Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 1

Management Issues Related to Accounting for Long-Term Assets OBJECTIVE 1 Identify the types of long-term assets and explain the management issues related to accounting for them. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 2

Characteristics of Long-Term Assets u Long-term assets are 4 4 4 4 assets that: Have a useful life of more than one year. Are acquired for use in the business. Are not intended for resale to customers. Must be capable of repeated use for a period of at least one year. Support the operating cycle instead of being part of it. Are reported at carrying (book) value. Carrying value is the unexplored part of the cost of an asset. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 3

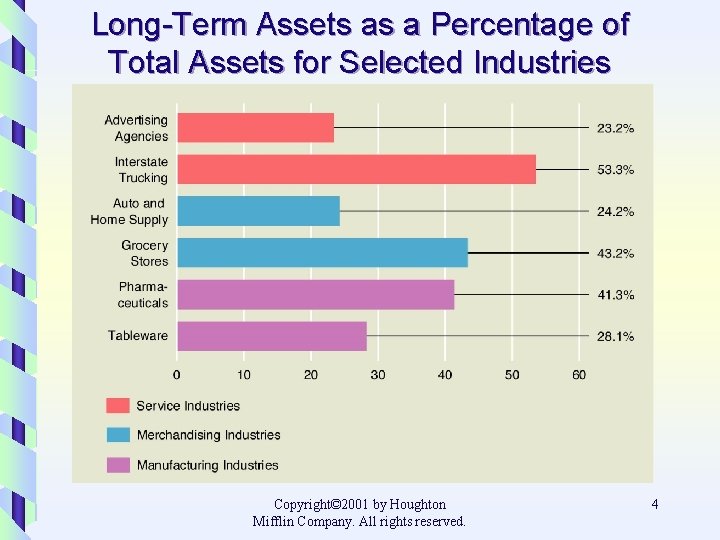

Long-Term Assets as a Percentage of Total Assets for Selected Industries Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 4

Deciding to Acquire Long-Term Assets u. A capital budgeting decision. u Decision is based on analyzing: 4 Future positive and negative cash flows. 4 The costs of training and maintenance. 4 The possibility that the expected savings may not occur. u Information on acquisitions of long-term assets is found under investing activities in the statement of cash flows. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 5

Financing Long-Term Assets u Financing alternatives: 4 4 4 4 Use cash flows from operations. Take a long-term loan. Take a short-term loan. Issue common stock. Issue long-term notes. Issue bonds. Lease instead of purchase. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 6

Applying the Matching Rule to Long-Term Assets u Two important issues must be resolved. 1. How much of the total cost to allocate to expense in the current accounting period. 2. How much to retain on the balance sheet as an asset to benefit future periods. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 7

Questions about the Acquisition, Use, and Disposal of Each Long-Term Asset 1. How is the cost of the long-term asset determined? 2. How should the expired portion of the cost of the long-term asset be allocated against revenues over time? 3. How should subsequent expenditures, such as repairs and additions, be treated? 4. How should disposal of the long-term asset be recorded? Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 8

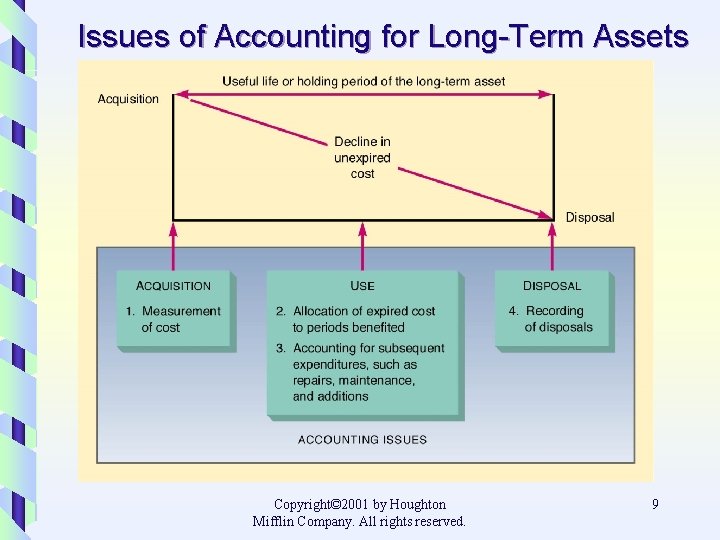

Issues of Accounting for Long-Term Assets Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 9

Acquisition Cost of Property, Plant, and Equipment OBJECTIVE 2 Distinguish between capital and revenue expenditures, and account for the cost of property, plant, and equipment. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 10

Expenditures u u u An expenditure is a payment or an obligation to make future payment for an asset or a service. A capital expenditure is made for the purchase or expansion of a long-term asset. A revenue expenditure is related to the repair, maintenance, and operation of a long-term asset. Careful distinction between revenue and capital expenditures is important to the proper application of the matching rule. 4 Understatements and overstatements of income can occur. Determining when a payment is an expense and when it is an asset is a matter of management judgment. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 11

Costs of Land u Purchase price. u Commissions to real estate agents. u Lawyers’ fees. u Accrued taxes paid by the purchaser. u Draining. u Tearing down old building(s). u Clearing and grading. u Assessments for improvements. u Landscaping. u Land is not subject to depreciation. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 12

Costs of Land Improvements u Include driveways, parking lots, and fences. u Have limited lives and are depreciated. u Should be recorded in an account called Land Improvements rather than in the Land account. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 13

Costs of Buildings u Purchase price. u Repairs and other expenses required to put it in usable condition. u Buildings are subject to depreciation because they have a limited useful life. u When a business constructs its own building, all costs of construction are included. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 14

Costs of Equipment u Purchase price. u Other expenditures required to prepare it for use. u Equipment is subject to depreciation. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 15

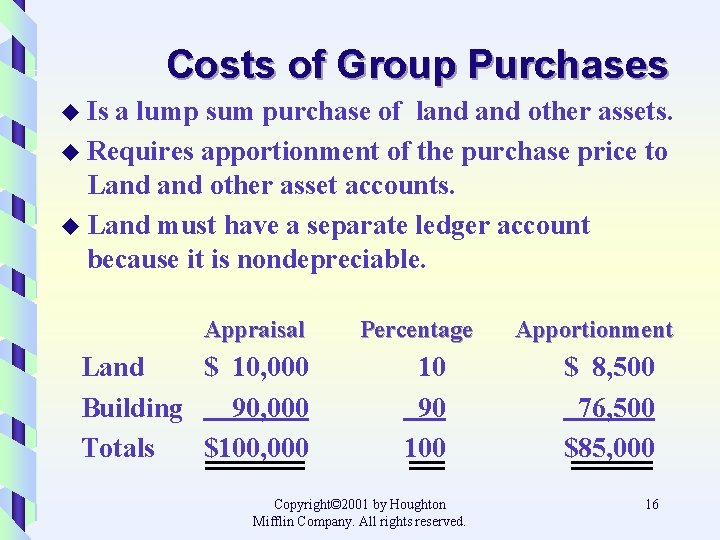

Costs of Group Purchases u Is a lump sum purchase of land other assets. u Requires apportionment of the purchase price to Land other asset accounts. u Land must have a separate ledger account because it is nondepreciable. Appraisal Land $ 10, 000 Building 90, 000 Totals $100, 000 Percentage 10 90 100 Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. Apportionment $ 8, 500 76, 500 $85, 000 16

Accounting for Depreciation OBJECTIVE 3 Define depreciation, state the factors that affect its computation, and show to record it. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 17

Definition of Depreciation u Depreciation accounting is described by the AICPA as: . . . a system of accounting which aims to distribute the cost or other basic value of tangible capital assets, less salvage (if any), over the estimated useful life of the unit. . . in a systematic and rational manner. It is a process of allocation, not of valuation. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 18

Features of Depreciation u All tangible assets except land have a limited useful life. u Depreciation means the allocation of the cost of a plant asset to the periods that benefit from the service of that asset. u Depreciation is not a process of valuation. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 19

Four Factors That Affect the Computation of Depreciation 1. Cost. Net purchase price. 4 All reasonable and necessary expenditures to get the asset in place and ready for use. 4 2. Residual value (salvage or disposal value). 4 An asset’s estimated net scrap, salvage, or trade-in value as of the estimated date of disposal. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 20

Four Factors That Affect the Computation of Depreciation (continued) 3. Depreciable cost. Cost less residual value. 4 Depreciable cost is allocated over the useful life of an asset. 4 4. Estimated useful life. Total number of service units expected from a long-term asset. 4 May be measured in years, miles, units, or similar measures. 4 Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 21

Accounting for Depreciation u Depreciation is recorded at the end of the accounting period by an adjusting entry in the following form: Depreciation Expense, Asset Name xxx Accumulated Depreciation, Asset Name xxx To record depreciation for the period Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 22

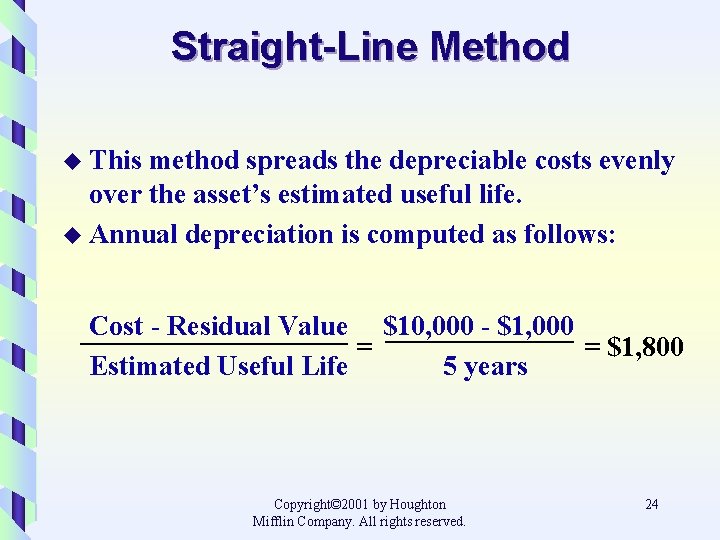

Methods of Computing Depreciation OBJECTIVE 4 a Compute periodic depreciation under the straight-line method. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 23

Straight-Line Method u This method spreads the depreciable costs evenly over the asset’s estimated useful life. u Annual depreciation is computed as follows: Cost - Residual Value $10, 000 - $1, 000 = = $1, 800 Estimated Useful Life 5 years Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 24

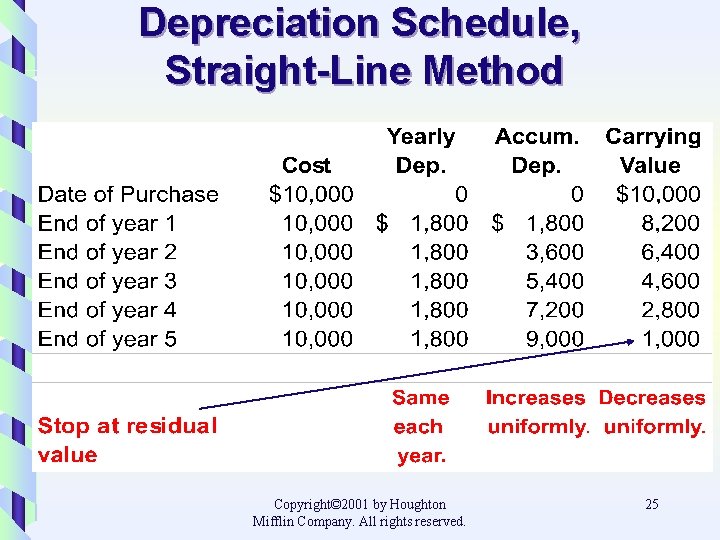

Depreciation Schedule, Straight-Line Method Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 25

Methods of Computing Depreciation OBJECTIVE 4 b Compute periodic depreciation under the production method. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 26

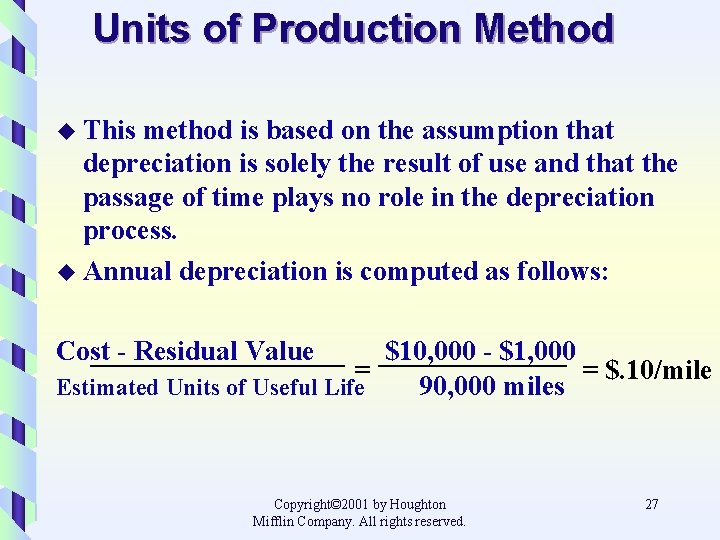

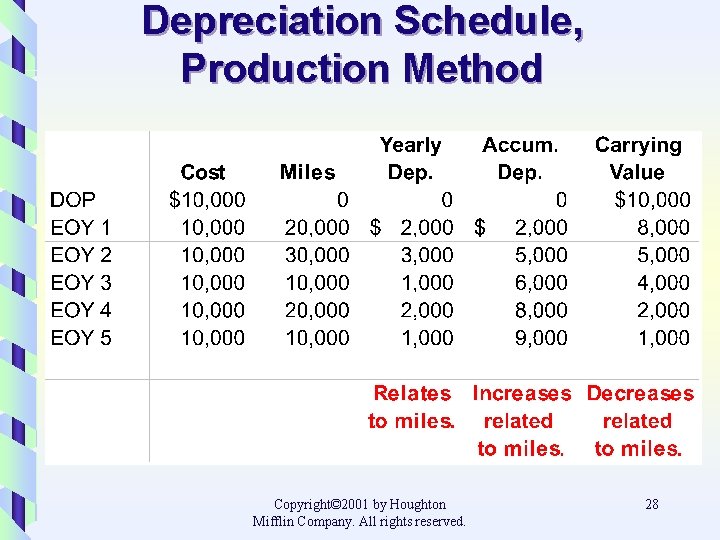

Units of Production Method u This method is based on the assumption that depreciation is solely the result of use and that the passage of time plays no role in the depreciation process. u Annual depreciation is computed as follows: Cost - Residual Value $10, 000 - $1, 000 = = $. 10/mile Estimated Units of Useful Life 90, 000 miles Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 27

Depreciation Schedule, Production Method Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 28

Methods of Computing Depreciation OBJECTIVE 4 c Compute periodic depreciation under the declining-balance method. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 29

Declining-Balance Method u Results in relatively large amounts of depreciation in the early years of an asset’s life and smaller amounts in later years. u Is an accelerated method. u Assumes that plant assets are most efficient when new. u Is consistent with the matching rule. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 30

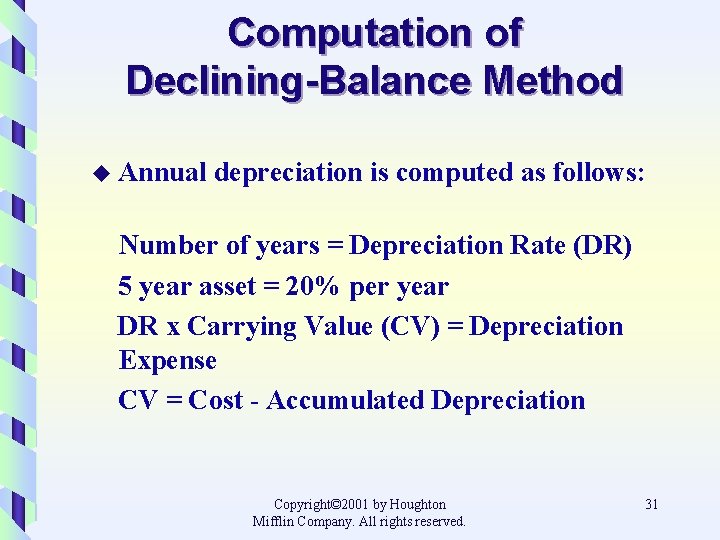

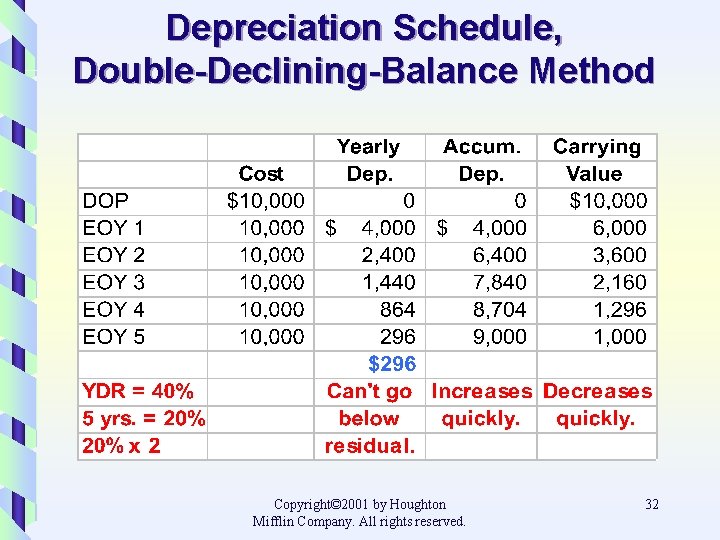

Computation of Declining-Balance Method u Annual depreciation is computed as follows: Number of years = Depreciation Rate (DR) 5 year asset = 20% per year DR x Carrying Value (CV) = Depreciation Expense CV = Cost - Accumulated Depreciation Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 31

Depreciation Schedule, Double-Declining-Balance Method Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 32

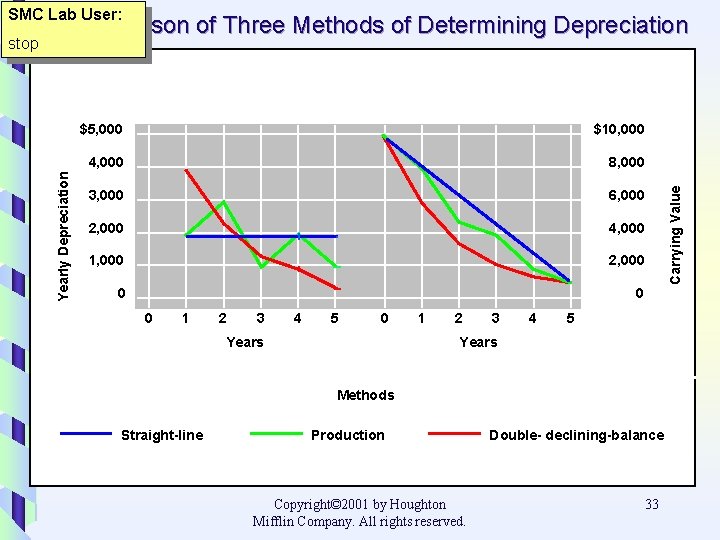

SMC Lab User: $5, 000 $10, 000 4, 000 8, 000 3, 000 6, 000 2, 000 4, 000 1, 000 2, 000 0 1 2 3 4 5 0 Years 1 2 3 4 Carrying Value Yearly Depreciation stop Comparison of Three Methods of Determining Depreciation 5 Years Methods Straight-line Production Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. Double- declining-balance 33

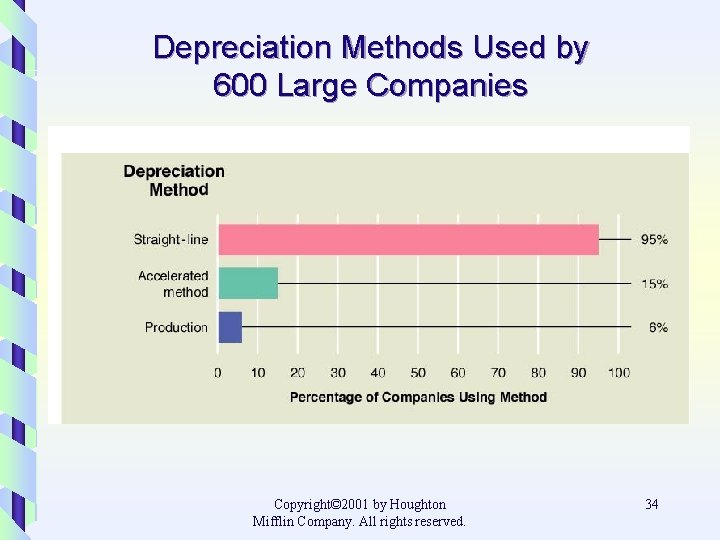

Depreciation Methods Used by 600 Large Companies Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 34

Disposal of Depreciable Assets OBJECTIVE 5 Account for the disposal of depreciable assets not involving exchanges. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 35

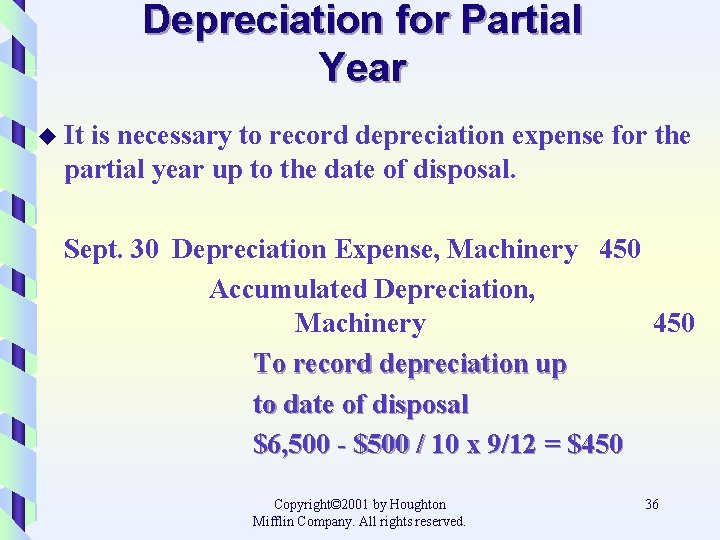

Depreciation for Partial Year u It is necessary to record depreciation expense for the partial year up to the date of disposal. Sept. 30 Depreciation Expense, Machinery 450 Accumulated Depreciation, Machinery 450 To record depreciation up to date of disposal $6, 500 - $500 / 10 x 9/12 = $450 Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 36

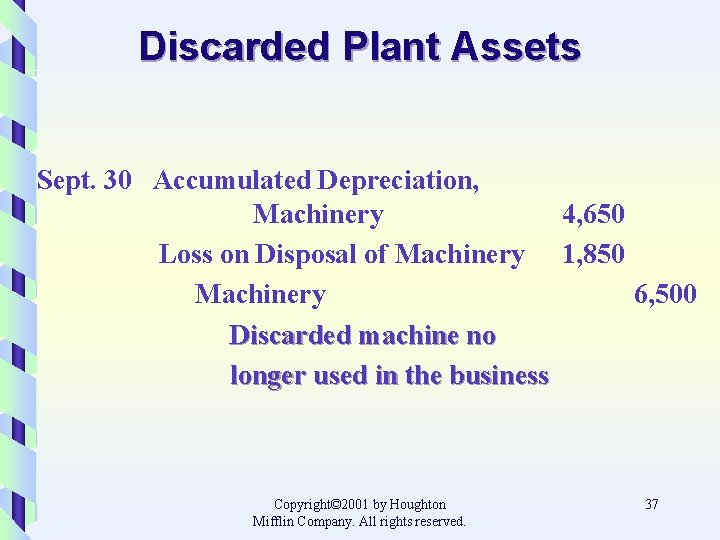

Discarded Plant Assets Sept. 30 Accumulated Depreciation, Machinery 4, 650 Loss on Disposal of Machinery 1, 850 Machinery 6, 500 Discarded machine no longer used in the business Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 37

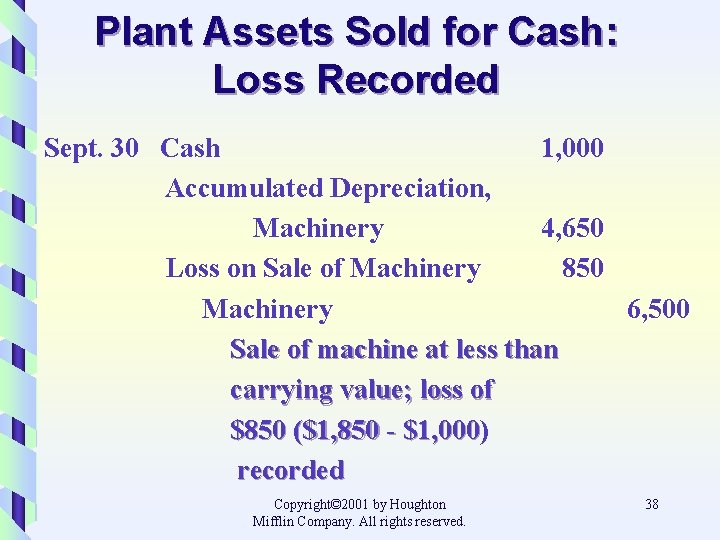

Plant Assets Sold for Cash: Loss Recorded Sept. 30 Cash 1, 000 Accumulated Depreciation, Machinery 4, 650 Loss on Sale of Machinery 850 Machinery 6, 500 Sale of machine at less than carrying value; loss of $850 ($1, 850 - $1, 000) $1, 000 recorded Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 38

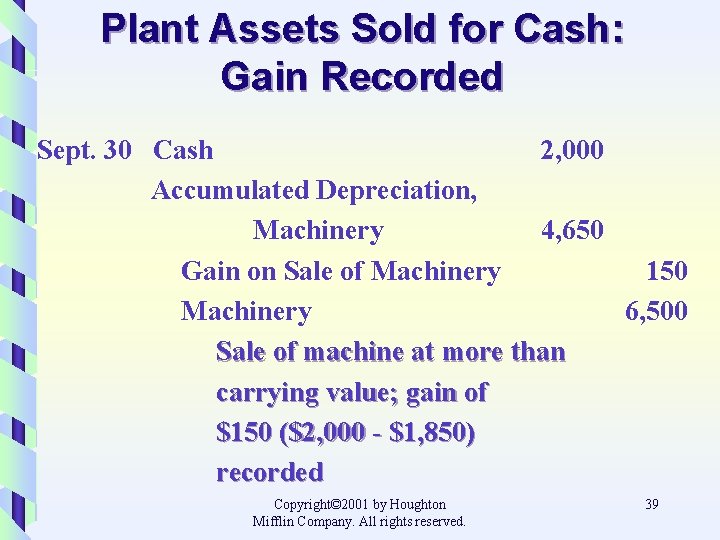

Plant Assets Sold for Cash: Gain Recorded Sept. 30 Cash 2, 000 Accumulated Depreciation, Machinery 4, 650 Gain on Sale of Machinery 150 Machinery 6, 500 Sale of machine at more than carrying value; gain of $150 ($2, 000 - $1, 850) recorded Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 39

Exchanges of Plant Assets OBJECTIVE 6 Account for the disposal of depreciable assets involving exchanges. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 40

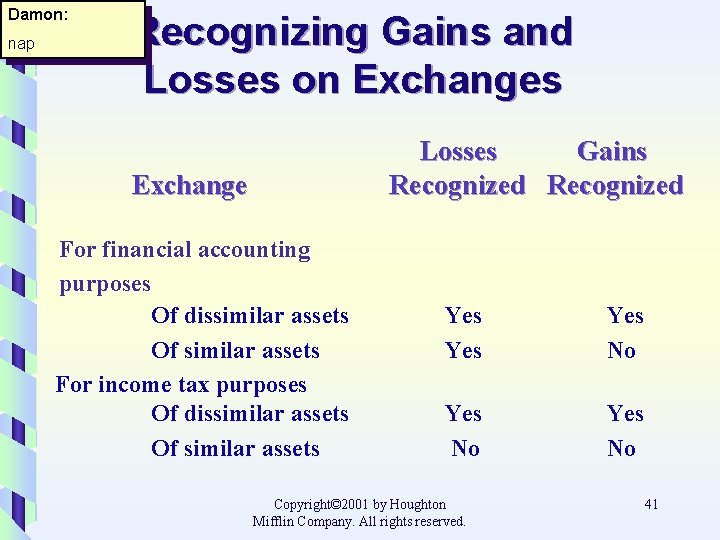

Damon: nap Recognizing Gains and Losses on Exchanges Losses Gains Recognized Exchange For financial accounting purposes Of dissimilar assets Of similar assets For income tax purposes Of dissimilar assets Of similar assets Yes Yes No Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 41

Accounting for Natural Resources OBJECTIVE 7 Identify the issues related to accounting for natural resources and compute depletion. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 42

Accounting for Natural Assets u Natural resources are shown on the balance sheet as long-term assets. u These assets are converted into inventory by cutting, pumping, or mining. u They are recorded at acquisition cost. u As the asset is converted to inventory, the asset account must be proportionally reduced. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 43

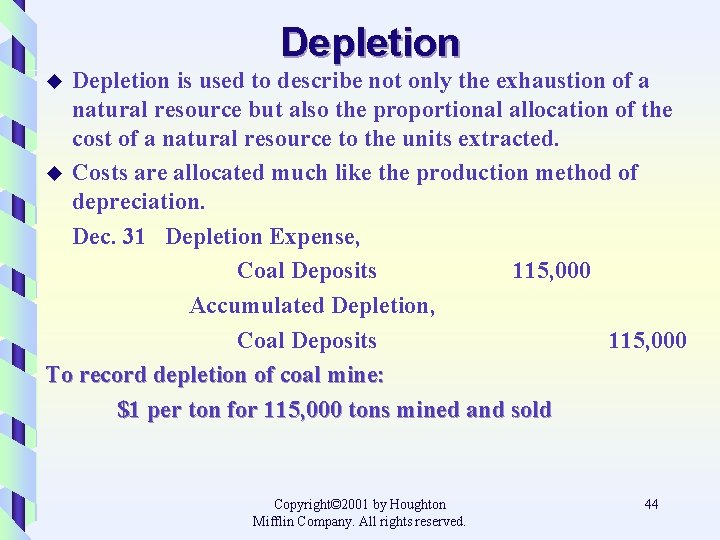

Depletion is used to describe not only the exhaustion of a natural resource but also the proportional allocation of the cost of a natural resource to the units extracted. u Costs are allocated much like the production method of depreciation. Dec. 31 Depletion Expense, Coal Deposits 115, 000 Accumulated Depletion, Coal Deposits 115, 000 To record depletion of coal mine: $1 per ton for 115, 000 tons mined and sold u Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 44

Depreciation of Closely Related Plant Assets u Closely related plant assets are those assets necessary to extract the resource. u If the life of the asset is longer than the life of the resource, it is depreciated on the same basis as the depletion is computed. u If the life of the asset is shorter than the life of the resource, it is depreciated over a shorter life. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 45

Development and Exploration Costs in the Oil and Gas Industry u u u Successful efforts accounting. 4 Cost recorded as an asset and depleted over the estimated life of the resource. 4 For an unsuccessful exploration, write off immediately as a loss. 4 More conservative method. Full-costing method. 4 All costs are recorded as assets and depleted over the estimated life of the producing resources. 4 Improves earnings performance in the early years. Either method is GAAP. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 46

Accounting for Intangible Assets OBJECTIVE 8 Apply the matching rule to intangible assets, including research and development costs and goodwill. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 47

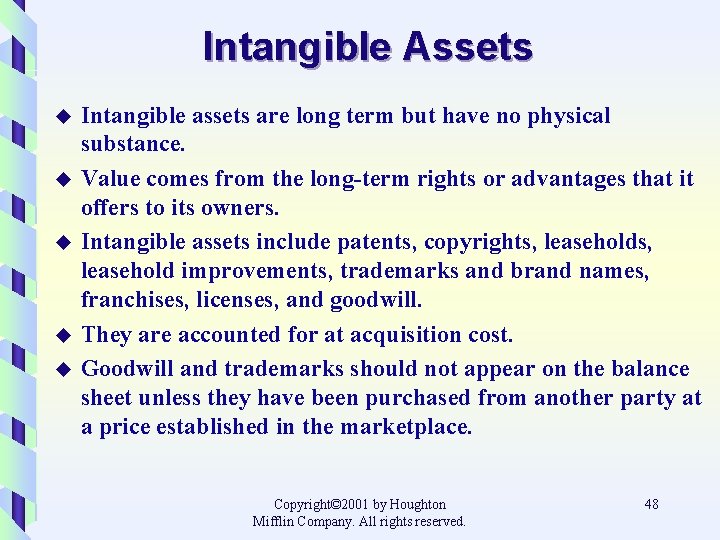

Intangible Assets u u u Intangible assets are long term but have no physical substance. Value comes from the long-term rights or advantages that it offers to its owners. Intangible assets include patents, copyrights, leasehold improvements, trademarks and brand names, franchises, licenses, and goodwill. They are accounted for at acquisition cost. Goodwill and trademarks should not appear on the balance sheet unless they have been purchased from another party at a price established in the marketplace. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 48

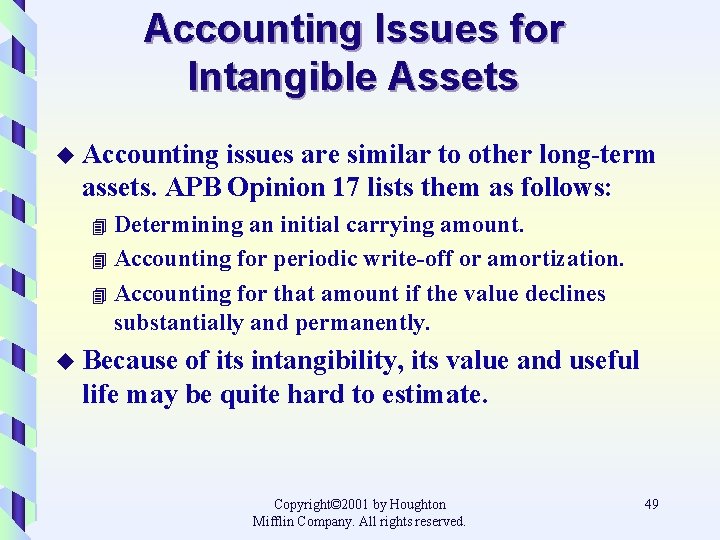

Accounting Issues for Intangible Assets u Accounting issues are similar to other long-term assets. APB Opinion 17 lists them as follows: Determining an initial carrying amount. 4 Accounting for periodic write-off or amortization. 4 Accounting for that amount if the value declines substantially and permanently. 4 u Because of its intangibility, its value and useful life may be quite hard to estimate. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 49

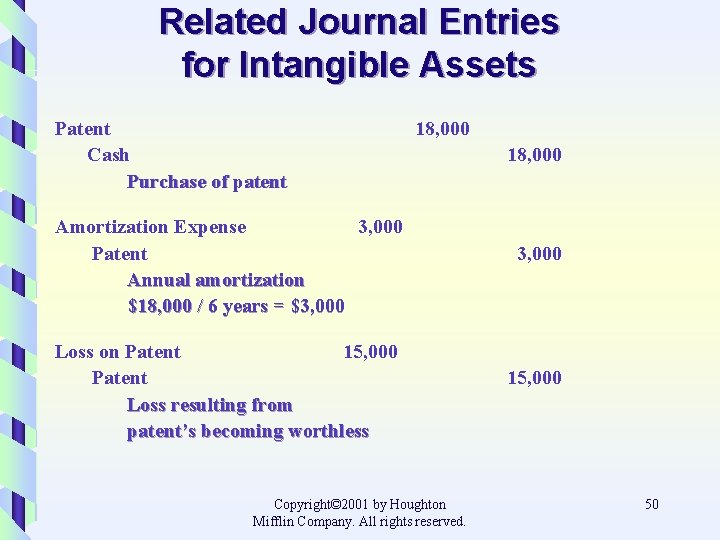

Related Journal Entries for Intangible Assets Patent Cash Purchase of patent 18, 000 Amortization Expense 3, 000 Patent Annual amortization $18, 000 / 6 years = $3, 000 Loss on Patent 15, 000 Patent Loss resulting from patent’s becoming worthless Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 18, 000 3, 000 15, 000 50

Research and Development Costs u The FASB has stated that: 1. R&D expenditures should be treated as revenue expenditures and charged to expense in the period when incurred. 2. Costs of R&D are continuous and necessary for the success of a business and should be treated as current expenses. 3. R&D costs do not necessarily result in future benefits (assets). Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 51

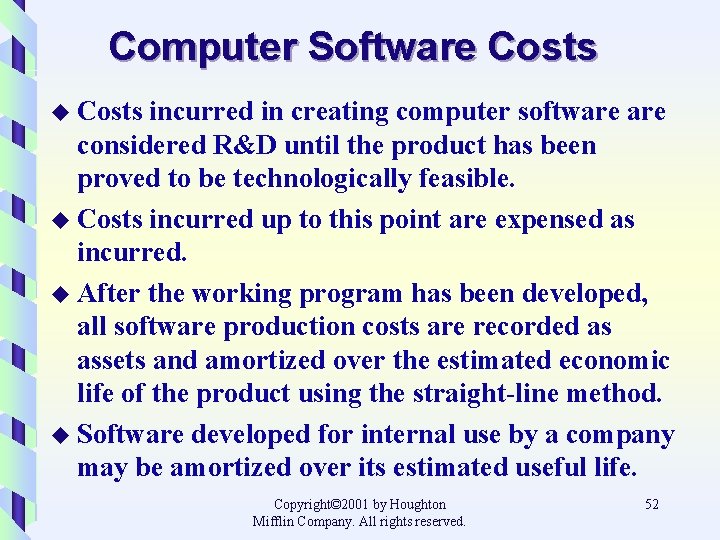

Computer Software Costs u Costs incurred in creating computer software considered R&D until the product has been proved to be technologically feasible. u Costs incurred up to this point are expensed as incurred. u After the working program has been developed, all software production costs are recorded as assets and amortized over the estimated economic life of the product using the straight-line method. u Software developed for internal use by a company may be amortized over its estimated useful life. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 52

Goodwill u Goodwill exists when a purchaser pays more for a business than the fair market value of the net assets if purchased separately. u The payment above and beyond the fair market value is recorded in the Goodwill account. u APB #17 states that goodwill should be amortized over a reasonable number of future periods, but not longer than 40 years. u Goodwill should not be recorded unless it is paid for in connection with the purchase of a whole business. u Amount = Purchase price - FMV of identifiable assets. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 53

Special Problems of Depreciating Plant Assets OBJECTIVE 9 Apply depreciation methods to problems of partial years, revised rates, groups of similar items, special types of capital expenditures, and cost recovery. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 54

Depreciation for Partial Years u Assume an asset is purchased on September 5 and the yearly accounting period ends on December 31. Cost - Scrap x Life in Years Number of Months 12 $3, 600 - $600 x 4 = $167 6 years 12 Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 55

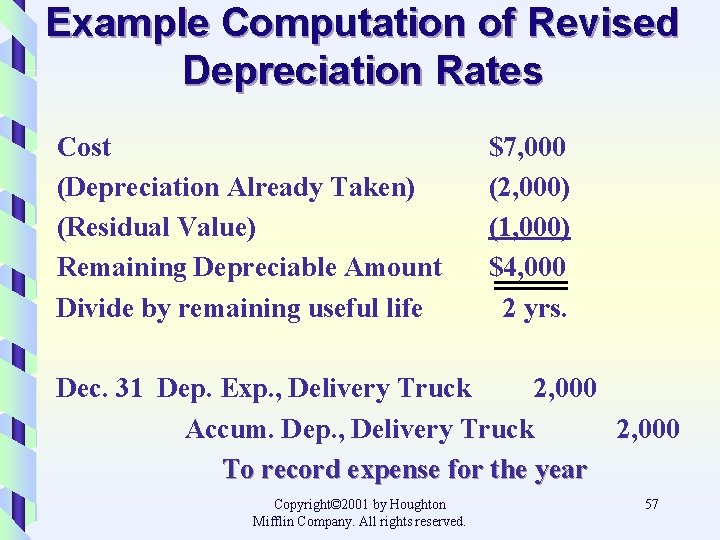

Revision of Depreciation Rates u Revision is made when it is determined that an asset will last for a longer or shorter period than originally thought. u The remaining depreciable cost of the asset is spread over the remaining years of useful life. u Depreciation expense is increased or decreased to reflect the asset’s changed life. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 56

Example Computation of Revised Depreciation Rates Cost (Depreciation Already Taken) (Residual Value) Remaining Depreciable Amount Divide by remaining useful life $7, 000 (2, 000) (1, 000) $4, 000 2 yrs. Dec. 31 Dep. Exp. , Delivery Truck 2, 000 Accum. Dep. , Delivery Truck 2, 000 To record expense for the year Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 57

Group Depreciation u Group depreciation is widely used when like assets are grouped and depreciated together. u This approach is convenient and includes assets such as trucks and office equipment. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 58

Special Types of Capital Expenditures u An addition is an enlargement of the physical layout of a plant asset. 4 The amount is debited to the asset account. u. A betterment is an improvement that does not add to the physical layout of a plant asset. 4 The cost is charged to the asset account. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 59

Special Types of Capital Expenditures (continued) u Ordinary repairs are expenditures necessary to keep an asset in good operating condition. 4 Such repairs are a current expense. u Extraordinary repairs are repairs of a more significant nature that affect the estimated residual value or estimated useful life of an asset. 4 Recorded by debiting the Accumulated Depreciation account. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 60

Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System u Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS) discards the concepts of estimated useful life and residual value. u MACRS requires that a cost recovery allowance be computed: On the unadjusted cost of property being recovered. 4 Over a period of years prescribed by the law for all property of similar types. 4 Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 61

Cost Recovery for Federal Income Tax Purposes u Congress hoped to encourage businesses to invest in new plant and equipment by allowing them to write off assets rapidly. u Tax methods of depreciation are not usually acceptable for financial reporting under GAAP. Copyright© 2001 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. 62

- Slides: 62