Chapter 1 Thinking Critically With Psychological Science 1

- Slides: 87

Chapter 1: Thinking Critically With Psychological Science 1

SQ 3 R n Survey, Question, Read, Recite, and Review, SQ 3 R is a study method that encourages active processing of new information. n Distributing study time, listening actively in class, overlearning, focusing on big ideas, and being a smart test-taker will also boost learning and performance. 2

Intro n Our intuition is often wrong when it comes to physical reality n If you drop a bullet off a table 3 feet high, and fire another one straight across an empty football field, which hits the ground first? 3

Intro n We are all amateur psychologists, suggested Fritz Heider, who attempted to explain others’ behavior (see Chapter 18). That need for a coherent world, however, sometimes leads to error. n There are limits to intuition and common sense n It is surprising that just a few minutes after seeing the effect scene, people would reliably claim to have seen the cause scene. 4

Intro n We tend to believe that we can accurately remember what we saw just a few minutes ago. n Memory for pictures tends to be more accurate than memory for words. n We put a lot of confidence in things that we have seen with our own eyes. 5

Intro n Application to eyewitness testimony in the courtroom is clear. Typically, cases go to trial many months after the events occur, very likely making eyewitnesses more vulnerable to inference-based errors. Misremembering the causes of others’ behavior over long periods may also foster conflict in social relationships. 6

Intro n Importantly, the research indicated that causal-inference errors were common in a backward but not a forward direction. n That is, exposure to “effect” pictures caused illusory memories of seeing “cause” pictures, but exposure to “cause” pictures did not produce false memories of seeing “effect” pictures. The researchers speculate that there is a stronger need to answer “Why? ” than to answer “What would happen if. . . ? ” 7

Hindsight Bias n I-knew-it-all-along phenomenon n Is the tendency to believe, after learning an outcome, that one would have foreseen it. n Finding out that something has happened makes it seem inevitable. n Thus, after learning the results of a study in psychology, it may seem to be obvious common sense. 8

However………. . n Experiments have found that events seem far less obvious and predictable beforehand than in hindsight. n Sometimes psychological findings even jolt our common sense. 9

Overconfidence n The Confirmation Bias: Overconfidence stems partly from our tendency to search for information that confirms our preconceptions. n Our everyday thinking is limited by our tendency to think we know more than we do. n Asked how sure we are of our answers to factual questions, we tend to be more confident than correct. n Despite lackluster predictions, the overconfidence of experts is hard to dislodge. 10

Overconfidence n It is really intellectual conceit!!! n The Psychic: ESP………. 11

Scientific attitude encourages critical thinking n Scientific attitude reflects a hard- headed curiosity to explore and understand the world without being fooled by it. n Critical thinking: examine assumptions, discern hidden values, evaluate evidence, and assess conclusions. 12

Scientific attitude encourages critical thinking n Active listening and participation is a requirement for learning and mastering a subject. n The study of psychology can help us to think critically. Remember that psychologists are scientists. n The scientific approach can help us evaluate competing claims and ideas regarding phenomena ranging from subliminal persuasion, ESP, and mother-infant bonding to astrology, basketball streak-shooting, and hypnotic age regression. 13

Scientific attitude encourages critical thinking n An important goal of this course is to teach questioning thinking that examines assumptions, discerns hidden values, evaluates evidence, and assesses conclusions. n Psychology’s critical inquiry has produced surprising findings that have sometimes debunked popular beliefs. 14

Scientific attitude encourages critical thinking n While making decisions, discerning people will welcome the powers of their gut wisdom yet know when to restrain it with rational, reality-based critical thinking. (e. g. , assessing suicide risk, jurors, truth from deception, sports, religion). 15

Scientific attitude encourages critical thinking n Our intuitions provide us with useful insights but they can also seriously mislead us. n The scientific method provides us with a very important tool in helping us sift sense from nonsense. 16

Scientific attitude encourages critical thinking n Randolph A. Smith’s Challenging Your Preconceptions: Thinking Critically About Psychology: n Guidelines for critical thinking… 17

Scientific attitude encourages critical thinking n Smith’s Guidelines for critical thinking… Critical thinkers are open-minded. They can live with uncertainty and ambiguity. 2. Critical thinkers are able to identify inherent biases and assumptions. They know that people’s beliefs and experiences shape the way they view and interpret their worlds. 1. 18

Scientific attitude encourages critical thinking n Smith’s Guidelines for critical thinking… 3. Critical thinkers practice an attitude of skepticism. They have trained themselves to question the statements and claims of even those people they respect. They are ready to reexamine their own ideas. 4. Critical thinkers distinguish facts from opinions. They recognize the need to rely on scientific evidence rather than personal experience. 19

Scientific attitude encourages critical thinking n Smith’s Guidelines for critical thinking… 5. Critical thinkers don’t oversimplify. They realize the world is complex and there may be multiple causes for behavior. 6. Critical thinkers use the processes of logical inference. They carefully examine the information given and recognize inconsistencies in statements and conclusions. 20

Scientific attitude encourages critical thinking n Smith’s Guidelines for critical thinking… 7. Critical thinkers review all the available evidence before reaching a conclusion. They will consult diverse sources of information and consider a variety of positions before making a judgment. 21

Psychological theories guide scientific research n A useful theory effectively organizes a wide range of observations and implies testable predictions, called hypotheses. n Research: test and reject or revise a particular theory. 22

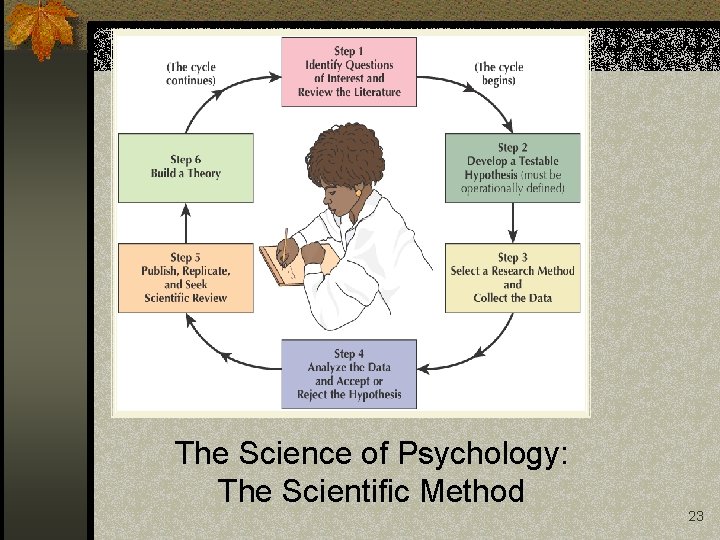

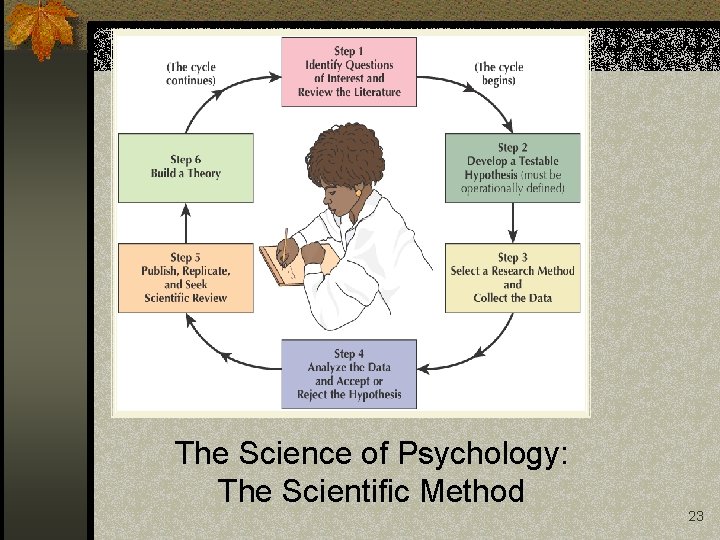

The Science of Psychology: The Scientific Method 23

Predictions n They specify in advance what results would support theory and what results would disconfirm it. n As an additional check on their own biases, psychologists report their results precisely with clear operational definitions of concepts. 24

Operational Definitions n Define research variables that allow others to replicate, or repeat, their observations. n Often, research leads to a revised theory that better organizes and predicts observable behaviors or events. n Must be clear, concise, specific! 25

Case Studies n Case Studies are a method by which psychologists analyze one or more individuals or groups in great depth in the hope of revealing things true of us all. While individual cases can suggest fruitful ideas, any given individual may be atypical, making the case misleading. 26

Case Studies n Leary identifies four uses of the case study in behavioral research. n First, as the text suggests, a case study may be used as a source of insights and ideas, particularly in the early stages of investigating a specific topic. (e. g. , Freud’s theory of psychoanalysis emerged from his case studies of therapy clients. Piaget’s theory of cognitive development arose from case studies of his own children) 27

Case Studies n Second, case studies may be used to describe particularly rare phenomena (e. g. , people who have killed or tried to kill U. S. presidents; Investigations of mass murders also are limited to a case study approach; Luria used a case study to describe another rare phenomenon—a man who had nearly perfect memory). 28

Case Studies n Third, case studies in the form of psychobiographies involve the application of psychological concepts and theories in an effort to understand the lives of famous people, such as da Vinci, Martin Luther, Mahatma Gandhi, Richard Nixon. 29

Case Studies n Finally, case studies provide illustrative anecdotes. Researchers and teachers often use case studies to illustrate general principles to other researchers and to students. 30

Case Studies n There at least two important limitations of case studies. n First, they are virtually useless in providing evidence to test behavioral theories or treatments. The lives and events studied occur in uncontrolled fashion and without comparison information. No matter how reasonable the investigator’s explanations, alternative explanations cannot be ruled out. 31

Case Studies n Second, most case studies rely on the observations of a single investigator. Thus, we often have no way of assessing the reliability or validity of the researcher’s observations or interpretations. n Because the researcher may have a vested interest in the outcome of the study (e. g. , whether a therapy works), one must always be concerned about self-fulfilling prophecies and demand characteristics. 32

Surveys n The survey looks at many cases in less depth and asks people to report their behavior or opinions. Asking questions is tricky because even subtle changes in the order or wording of questions can dramatically affect responses. n A limitation: what people say and what they do are often two very different things. 33

Bias n We are vulnerable to the false consensus effect, whereby we overestimate others’ agreement with us. n The survey ascertains the self-reported attitudes or behaviors of a population by questioning a representative, random sample. 34

Representative Sample n Obtaining a representative sample of even a well-defined population may not be easy. Ø Who has a phone Ø Who will actually vote Ø Who is on what list Ø Time of day call is made Ø How many surveys sent vs. how many returned Ø Compared to what!!!!! (e. g. , recommended by more than 75% of dentists) 35

Naturalistic Observation n Consists of observing and recording the behavior of organisms in their natural environment. n Like the case study and survey methods, this research strategy describes behavior but does not explain it. 36

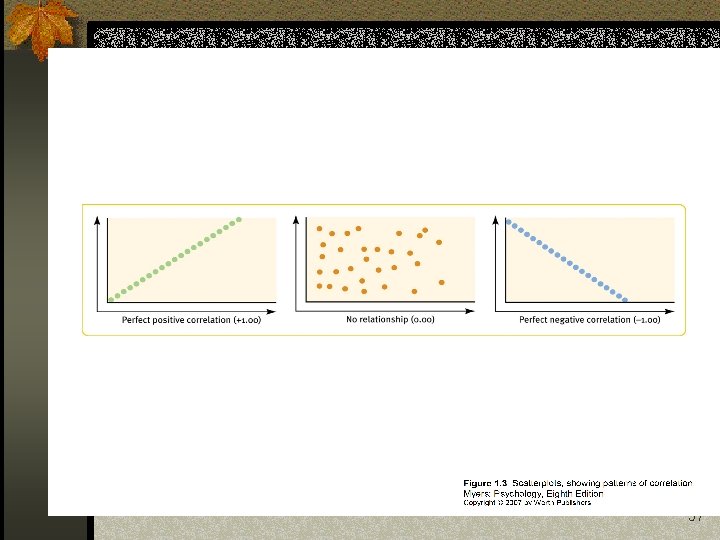

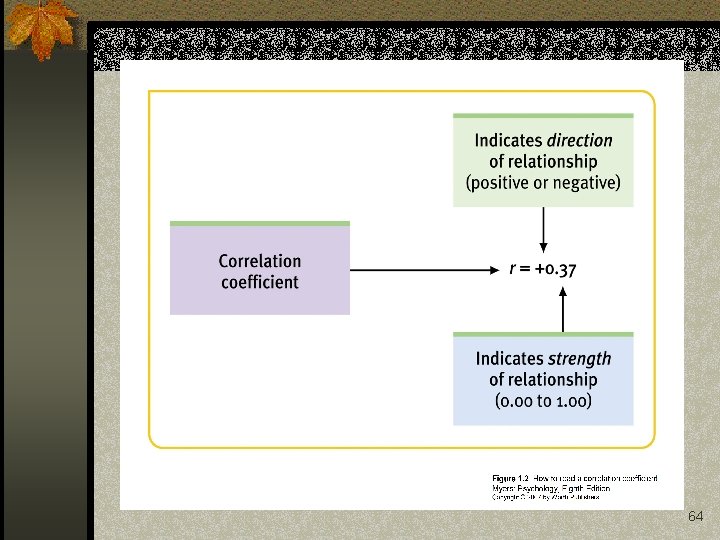

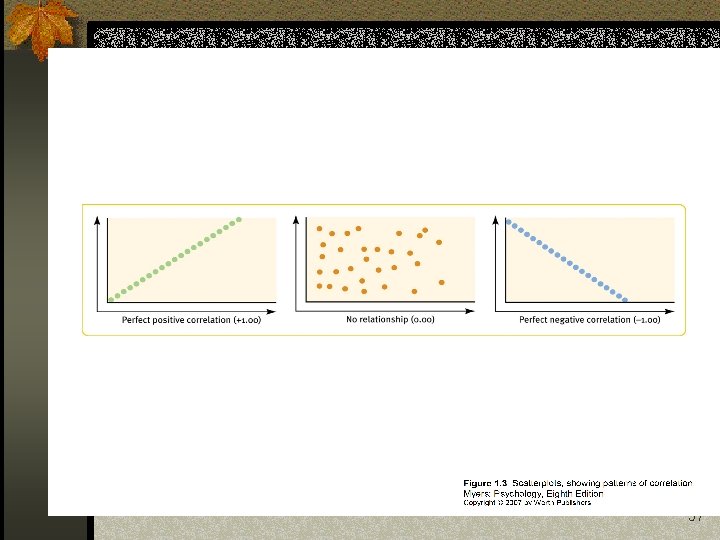

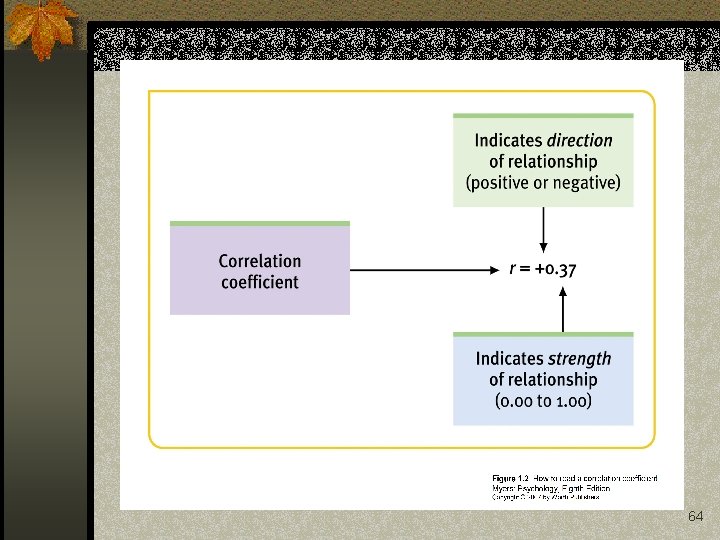

Correlations n When surveys and naturalistic observations reveal that one trait or behavior accompanies another, we say the two correlate. n A correlation coefficient is a statistical measure of relationship. n n a positive correlation indicates a direct relationship, meaning that two things increase together or decrease together. a negative correlation indicates an inverse relationship: As one thing increases, the other decreases. 37

Correlations n The tendency to interpret correlations in terms of cause and effect is a common error. 38

Correlations n Hippocrates’ delightful Good News Survey (GNS) was designed to illustrate errors that can be hidden in seemingly sound scientific studies. n The survey found that people who often ate Frosted Flakes as children had half the cancer rate of those who never ate the cereal. n Conversely, those who often ate oatmeal as children were four times more likely to develop cancer than those who did not. n Does this mean that Frosted Flakes prevents cancer while oatmeal causes it? 39

Correlations n What are the explanations for these correlations. The answer? n Cancer tends to be a disease of later life. Those who ate Frosted Flakes are younger. In fact, the cereal was not around when older respondents were children, and so they are much more likely to have eaten oatmeal. 40

Correlations n Scientists have linked television-watching with childhood obesity. In fact, the degree of obesity rises 2 percent for each hour of television viewed per week by those aged 12 to 17, according to a study in the Journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. n One explanation is that TV watching results in less exercise and more snacking (often on the high-calorie, low-nutrition foods pitched in commercials). Is that conclusion justified? 41

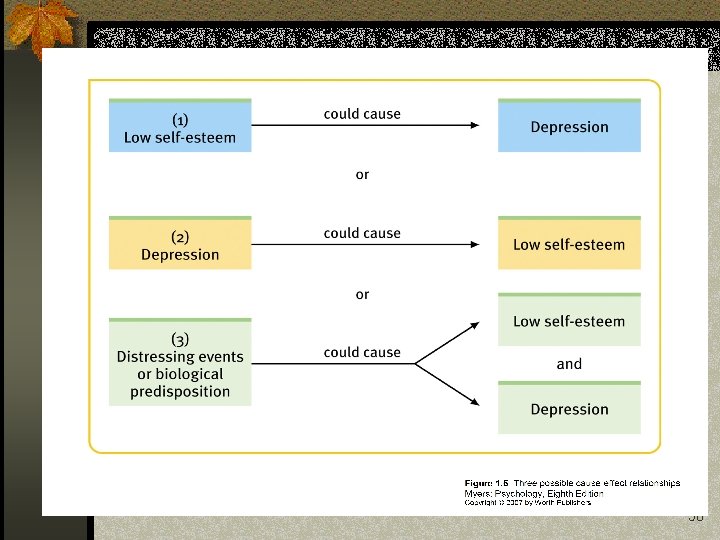

Correlations n What are some alternative explanations for the correlation? n The causal relationship may be reversed. Obesity may lead children to prefer more sedentary activities, such as TV viewing. n Or, some third factor may explain the relationship. For example, parents having little formal education may not emphasize good nutrition or good use of leisure time. 42

Correlations Misinterpreting Correlations: n Keith Stanovich has identified two major classes of ambiguity in correlational research: the “directionality problem” and the “third variable possibility. ” n Directionality Problem: Researchers have long known about the correlation between eyemovement patterns and reading ability: Poorer readers have more erratic patterns (moving the eyes from right to left and making more stops) per line of text. 43

Correlations directionality problem: n In the past, however, some educators concluded that “deficient oculomotor skills” caused reading problems and so developed “eye-movement training” programs as a corrective. Many school districts may still have “eye-movement trainers, ” representing thousands of dollars of equipment, gathering dust in their storage basements. 44

Correlations directionality problem: n Careful research has indicated that the eye movement/reading ability correlation reflects a causal relationship that runs in the opposite direction. n Slow word recognition and comprehension difficulty lead to erratic eye movements. n When children are taught to recognize words efficiently and to comprehend better, their eye movements become smoother. n Training children’s eye movements does nothing to enhance their reading comprehension. 45

Correlations Third variable possibility: n Basically, a third variable account for the problem. E. g. , an unexpected virus. n Poor people living in an area with poor sanitation contract a serious disease. After more research, however, the cause was found to be related to an inadequate diet- nothing at all to do with the sanitary conditions. 46

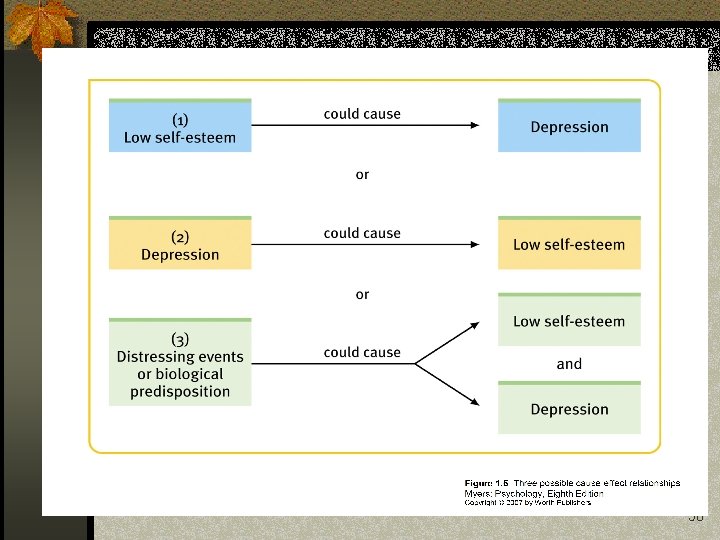

Correlation Vs. Casuation n Perhaps the most irresistible thinking error is to assume that correlation proves causation. n Correlation reveals how closely two things vary together and thus how well one predicts the other. n However, the fact that events are correlated does not mean that one causes the other. n Thus, while correlation enables prediction, it does not provide explanation. 47

Correlations Exercise 48

Scatter Plots n Researchers depict scores on graphs called scatterplots; each point plots the value of two variables. n The correlation coefficient helps us to see the world more clearly by revealing the extent to which two things relate. 49

50

Illusory Correlation n The perception of a relationship where none exists, often occurs because our belief that a relationship exists leads us to notice and recall confirming instances of that belief. n Because we are sensitive to unusual events, we are especially likely to notice and remember the occurrence of two such events in sequence, for example, a premonition of an unlikely phone call followed by the call. 51

n Given even random data, we look for meaningful patterns. We usually find order because random sequences often don’t look random. n Apparent patterns and streaks (such as repeating digits) occur more often than people expect. n Failing to see random occurrences for what they are can lead us to seek extraordinary explanations for ordinary events. 52

n Failure to take into account all the relevant information also helps explain certain common misconceptions: n (1) because more accidents occur at home than elsewhere, we may believe it’s more dangerous to be at home, and n (2) because more violence is committed against members of one’s own family than against anyone else, we may conclude it is more dangerous to be around family members than around strangers. 53

n The problem is that we spend more time at home than any other place and we are also around our relatives more than anyone else. n Similarly, finding that more automobile accidents occur during rush hour than at any other time does not necessarily imply that it’s more dangerous to drive during rush hour. n It could be, but the greater number of accidents may also occur simply because that’s when so many people are driving their cars. n From sheer numbers alone, far more windshield wipers are turned on during rush hour than during any other time but that does not mean that it rains more during rush hour. 54

Perceiving Order in Random Events n What may seem to be an extraordinary event may have a chance-related explanation. n As Myers states, “An event that happens to but one in 1 billion people every day occurs about six times a day, 2000 times a year. ” 55

Perceiving Order in Random Events n Random sequences often do not look random. n E. g. , coin tosses, number occurrences n When you don’t seem to think this coin toss or string of numbers in the lotto is a chance event. And that is what’s known as the gambler’s fallacy. ” 56

57

58

Experiment n Is a research method in which the investigator manipulates one or more variables to observe their effect on some behavior or mental process while controlling other relevant factors. n If a behavior changes when we vary an experimental factor, then we know the factor is having a causal effect. 59

Random Assignment & Double-Blind n In many experiments, control is achieved by randomly assigning people either to an experimental condition, where they are exposed to the treatment, or a control condition, where they are not exposed. 60

Double-Blind n Often, the research participants are blind (uninformed) about what treatment, if any, they are receiving. n One group might receive the treatment, while the other group receives a placebo (a pseudotreatment). n Often both the participant and the research assistant who collects the data will not know which condition the participant is in (the double-blind procedure). 61

Placebo Effect n The placebo effect is well-documented. Just thinking one is receiving treatment can lead to symptom relief. n However, the individual did not receive the treatment. 62

Variables n The independent variable is the experimental factor that is being manipulated. It is the variable whose effect is being studied. n The dependent variable is the variable that may change in response to the manipulations of the independent variable. It is the outcome factor. 63

64

Bar Graphs n Bar graphs provide one way to organize and present distributions of data. n The visual display permits comparisons between different groups on the same quantitative dimension. n Reducing or expanding the range of that measure can make differences between groups appear smaller or larger. It is always important to read the scale labels and note the range. 65

Three Measures of Central Tendency n Mode: is the most frequently occurring score in a distribution. n Mean: is the arithmetic average of a distribution, obtained by adding the scores and then dividing by the number of scores. It is biased by a few extreme scores. n Median: is the middle score in a distribution; half the scores are above it and half are below it. 66

Two Measures of Variation n The range of scores—the gap between the lowest and highest score—provides only a rough estimate of variation. n The more standard measure of how scores deviate from one another is the standard deviation. It better gauges whether scores are packed together or dispersed because it uses information from each score. 67

Important principles to remember in making generalizations n Representative samples are better than biased samples. We are particularly prone to overgeneralize from vivid cases at the extremes. n Less-variable observations are better than those that are more variable. Averages are more reliable when derived from scores with low variability. n More cases are better than fewer. Small samples provide less reliable estimates of the average than do large samples. 68

When are Differences Meaningful? n Tests of statistical significance to help them determine whether differences between two groups are reliable. n When the averages of the samples drawn from the groups are reliable, and the difference between them is large, we say the difference has statistical significance. 69

n This means that the difference very likely reflects a real difference and is not due to chance variation between the samples. n Given large enough or homogeneous enough samples, a difference between them may be statistically significant yet have little practical significance. 70

Laboratory Experiments n The experimenter intends the laboratory experiment to be a simplified reality, one in which important features can be simulated and controlled. n The experiment’s purpose is not to re-create the exact behaviors of everyday life but to test theoretical principles. n It is the resulting principles—not the specific findings—that help explain everyday behavior. 71

Generalizing Findings n Although culture shapes our specific attitudes and behaviors, the principles that underlie them vary much less. n Our shared biological heritage unites us as members of a universal human family. 72

n Studying gender differences is not only interesting but also potentially beneficial in preventing conflict and misunderstanding in everyday relationships. n It is important to remember, however, that psychologically as well as biologically, women and men are overwhelmingly similar. 73

Statistics n Statistics help us to organize, summarize, and make inferences from data. n They enable us to evaluate big, round, undocumented numbers that often misread reality and mislead the public. n Statistics help us to see what the naked eye misses. 74

Describing Data n Statistics help us to organize, summarize, and make inferences from data. n They enable us to evaluate big, round, undocumented numbers that often misread reality and mislead the public. n Statistics help us to see what the naked eye misses. 75

Making Inferences n The temptation to generalize from a few unrepresentative but vivid cases is nearly irresistible. 76

Differences Between Groups n The need for two sample groups can be readily overlooked. Without having comparison groups, we are unable to evaluate the claims. In other cases, we may not know whether the comparison group is appropriate. 77

Differences Between Groups n A detergent manufacturer claims that its dishwashing liquid has been found to be 35 percent more effective. Should you switch to its brand? n A major corporation proudly claims that its profits have increased 150 percent over those in the previous year. Should one rush out and buy its stock? n In each case, we cannot make an informed judgment without knowing the nature of the comparison group. 78

Can Laboratory Experiments Illuminate Everyday Life? n In an attempt to overcome the artificiality of the laboratory environment, some researchers conduct field experiments. For example, do the race and sex of a person who requests help influence our generosity? 79

Research n Some psychologists study animals out of an interest in animal behaviors. n Others do so because knowledge of the physiological and psychological processes of animals enables them to better understand the similar processes that operate in humans. 80

n Because psychologists follow ethical and legal guidelines, animals used in psychological experiments rarely experience pain. n The debate between animal protection organizations and researchers has raised two important issues: Is it right to place the well-being of humans above that of animals, and what safeguards are in place to protect the well-being of animals in research? 81

n Ethical principles for the treatment of human participants urge investigators to obtain informed consent, protect subjects from harm and discomfort, treat information about individuals confidentially, and fully explain the research afterward. 82

Research Ethics n Stanley Milgram’s studies of obedience (see Chapter 18), which heightened awareness of the problems of deception in research and of psychological harm to participants. n Practically all the ethical issues reflect a conflict between the rights of the individual and the possible benefits of the research to society. 83

Research Ethics n Psychologists have typically applied a cost-benefit analysis. n Does the potential benefit of the study to society outweigh the potential costs to participants? 84

Personal Values Can Influence n Psychologists’ values can influence their choice of research topic, their theories and observations, their labels for behavior, and their professional advice. n Knowledge is power that can be used for good or evil. 85

Personal Values Can Influence n Our preconceptions bias our observations and interpretations (e. g. , assessment data, recommendations) n Values also penetrate theories proposed by psychologists. n Perhaps the most seductive error is to translate one’s description of what is into a prescription of what ought to be (naturalistic fallacy. (e. g. , Kohlberg’s highest level few ever reach 86

n Applications of psychology’s principles have so far been mostly for the good, and psychology addresses some of humanity’s greatest problems and deepest longings. 87