Chapter 02 Special Relativity Version 110906 110907 110908

- Slides: 96

Chapter 02 Special Relativity Version 110906, 110907, 110908, 110913 General Bibliography 1) Various wikipedia, as specified 2) Thornton-Rex, Modern Physics for Scientists & Eng, as indicated

Outline • • • Galilean Transformations Names & Reference Frames The Ether River Michelson-Morley Experiments Einstein Postulates Lorentz Transformations – Position – Velocity • • Space-Time Diagrams Relativistic Forces & Momentum Relativistic Mass Relativistic Energy

CLASSICAL / GALILEAN / NEWTONIAN TRANSFORMATIONS

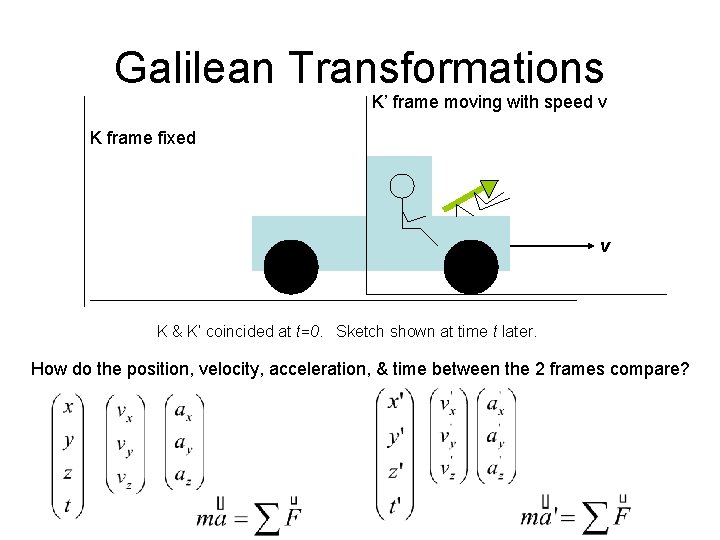

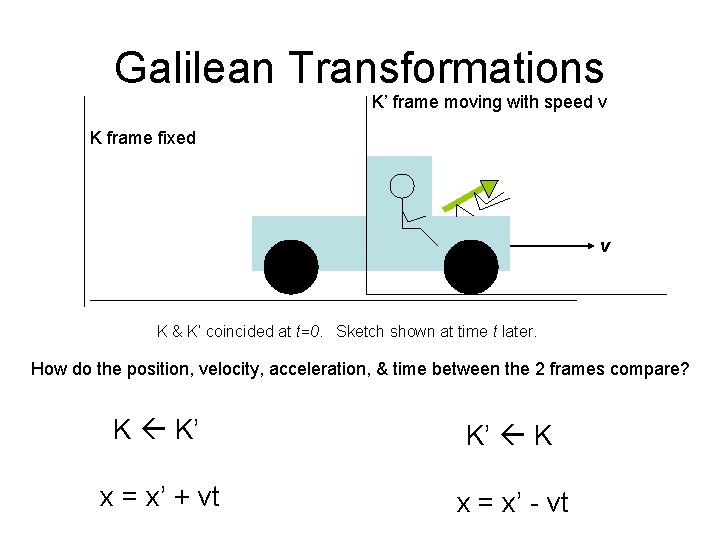

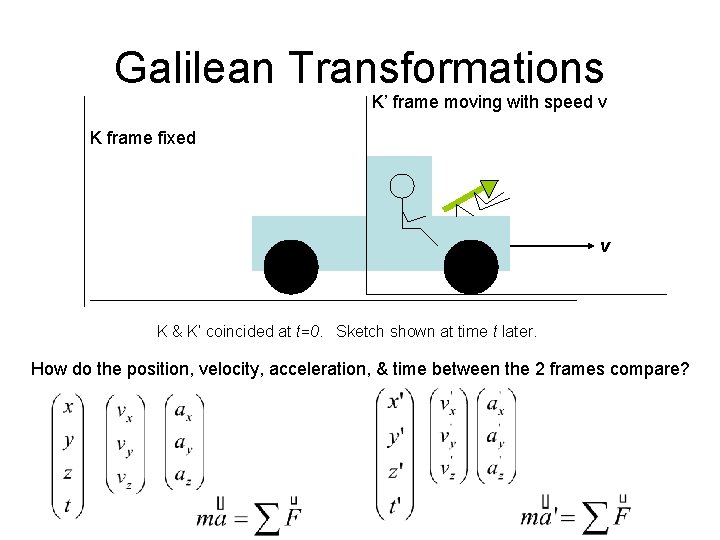

Galilean Transformations K’ frame moving with speed v K frame fixed v K & K’ coincided at t=0. Sketch shown at time t later. How do the position, velocity, acceleration, & time between the 2 frames compare?

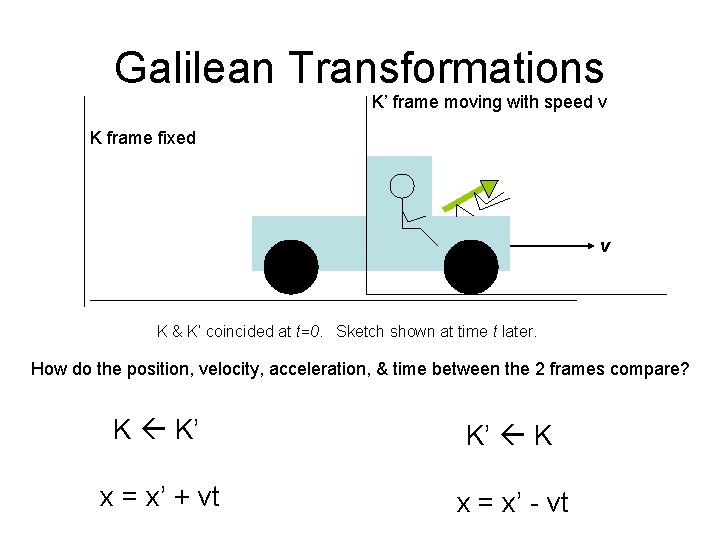

Galilean Transformations K’ frame moving with speed v K frame fixed v K & K’ coincided at t=0. Sketch shown at time t later. How do the position, velocity, acceleration, & time between the 2 frames compare? K K’ K’ K x = x’ + vt x = x’ - vt

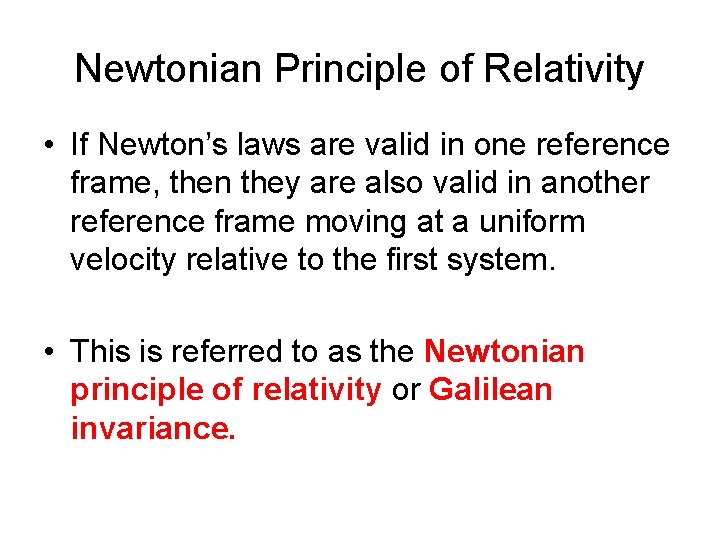

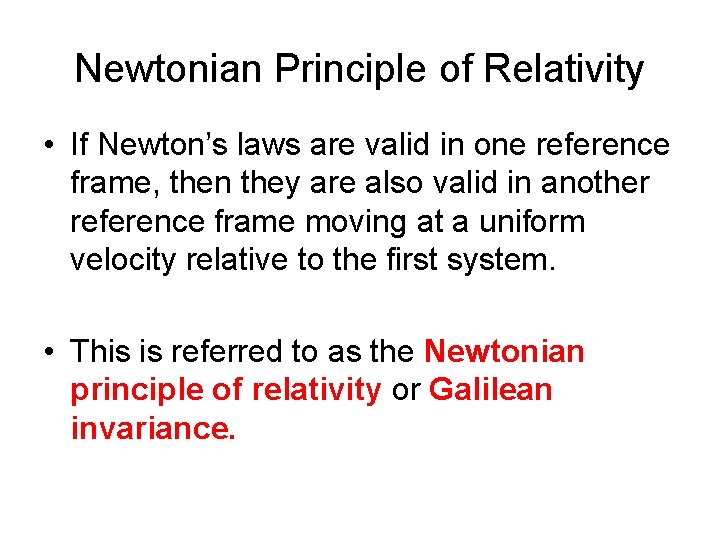

Newtonian Principle of Relativity • If Newton’s laws are valid in one reference frame, then they are also valid in another reference frame moving at a uniform velocity relative to the first system. • This is referred to as the Newtonian principle of relativity or Galilean invariance.

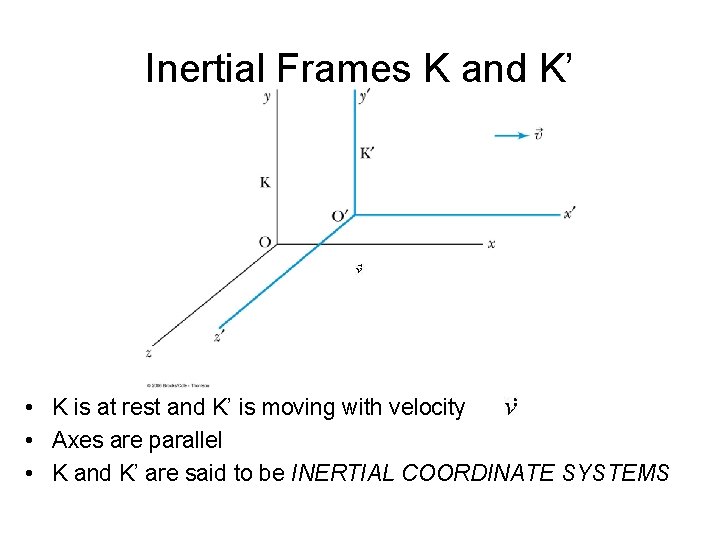

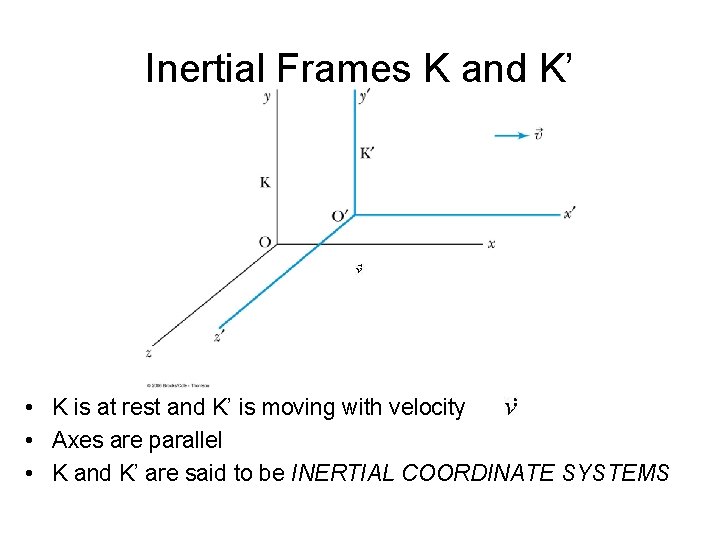

Inertial Frames K and K’ • K is at rest and K’ is moving with velocity • Axes are parallel • K and K’ are said to be INERTIAL COORDINATE SYSTEMS

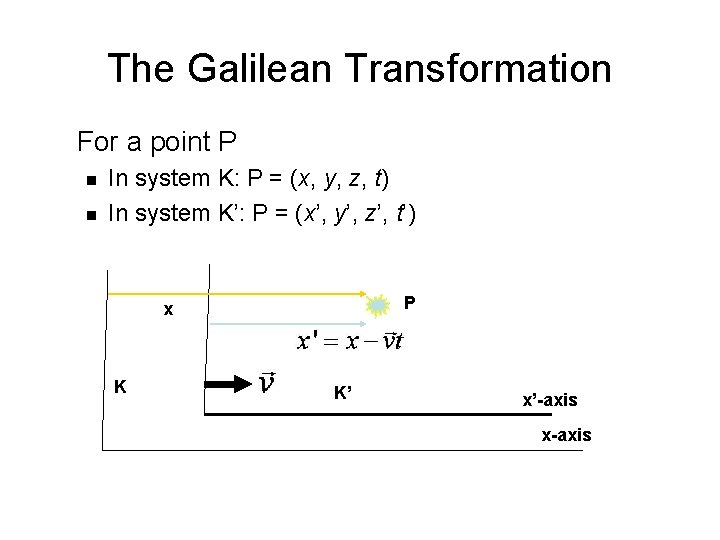

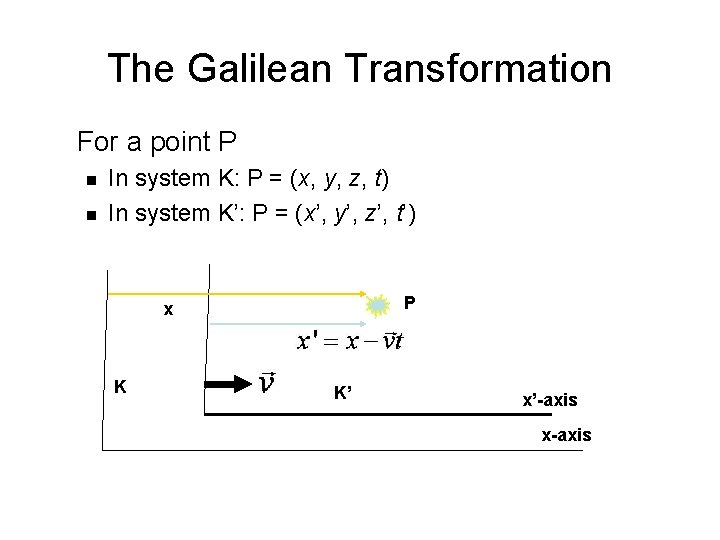

The Galilean Transformation For a point P n n In system K: P = (x, y, z, t) In system K’: P = (x’, y’, z’, t’) P x K K’ x’-axis x-axis

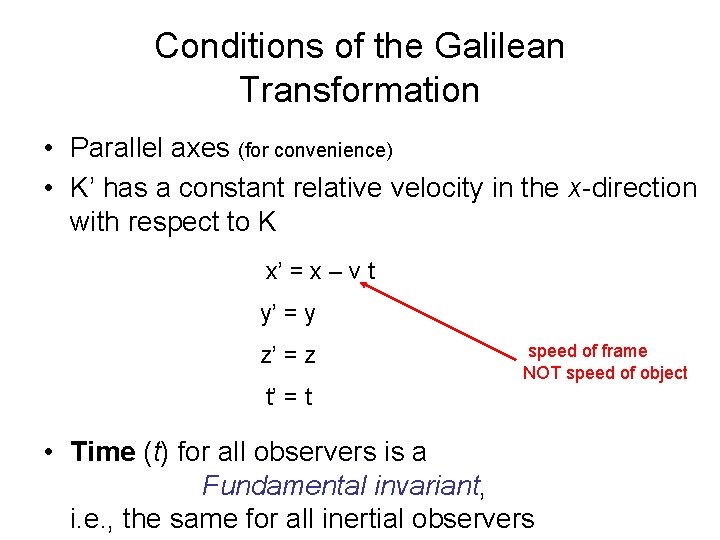

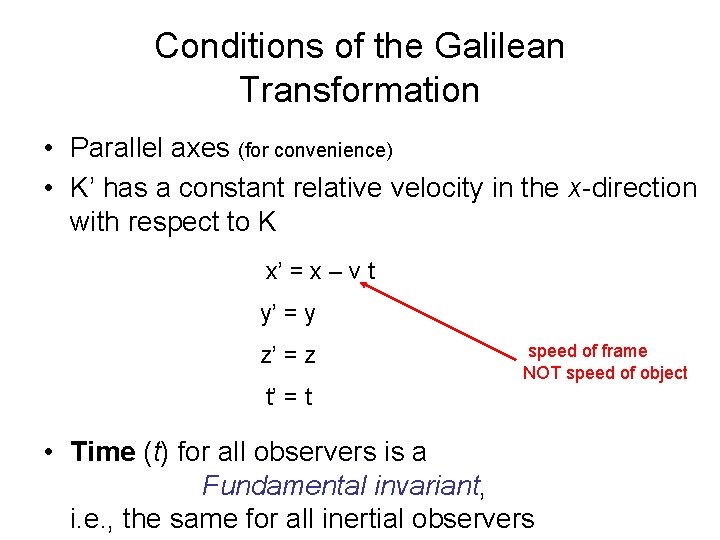

Conditions of the Galilean Transformation • Parallel axes (for convenience) • K’ has a constant relative velocity in the x-direction with respect to K x’ = x – v t y’ = y z’ = z speed of frame NOT speed of object t’ = t • Time (t) for all observers is a Fundamental invariant, i. e. , the same for all inertial observers

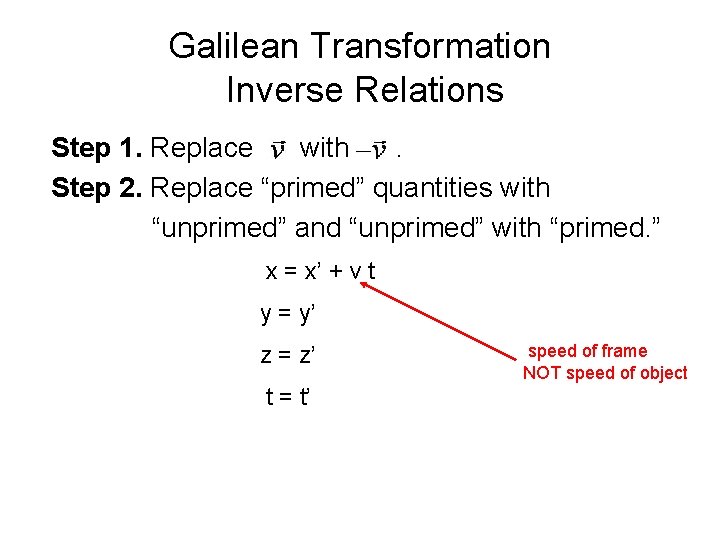

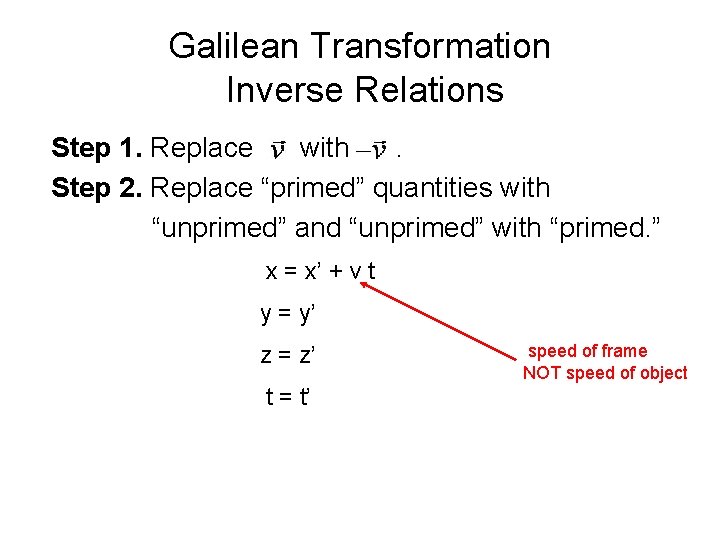

Galilean Transformation Inverse Relations Step 1. Replace with. Step 2. Replace “primed” quantities with “unprimed” and “unprimed” with “primed. ” x = x’ + v t y = y’ z = z’ t = t’ speed of frame NOT speed of object

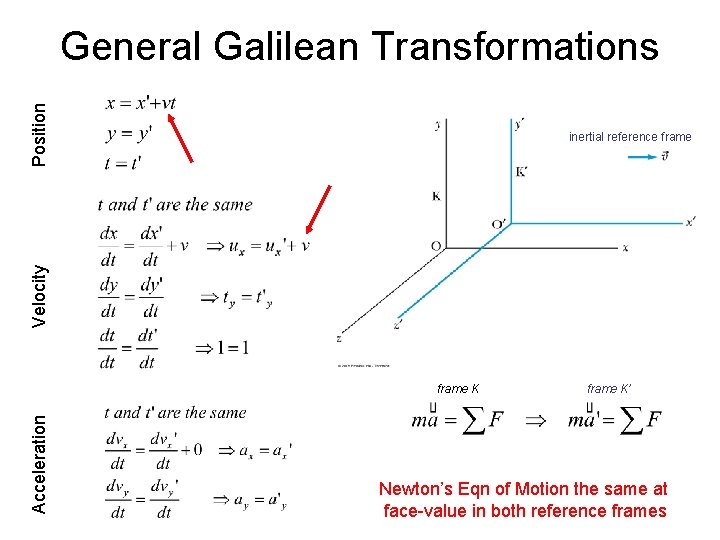

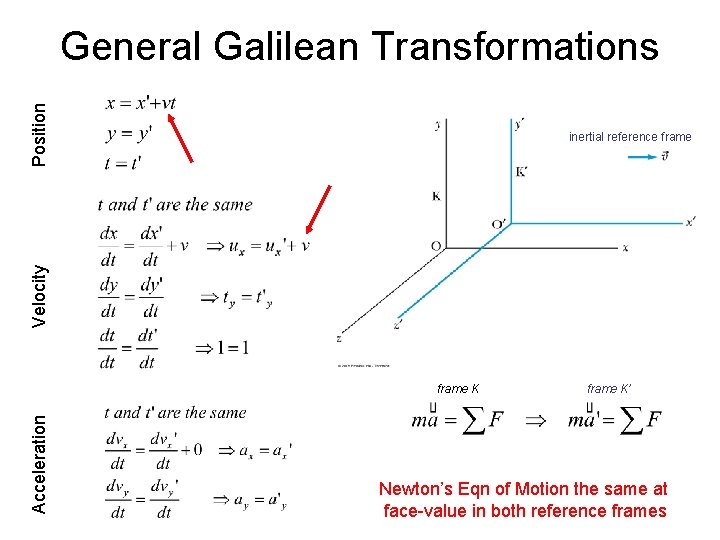

Position General Galilean Transformations Velocity inertial reference frame Acceleration frame K’ Newton’s Eqn of Motion the same at face-value in both reference frames

Classical Reference Frames • Inertial Reference Frame – Non-accelerating – Newton’s Laws apply at face-value • Non-Inertial Reference Frame – Examples: • Rocket during acceleration phase • Rotating merry-go-round • Rotating Earth

Youtube clips (part 1) • Galilean/Classical Relativity Part 1 – The Cassiopeia Project http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=6 rl 3 Z 9 y. CTn 8 The Cassiopeia Project is an effort to make high quality science videos available to everyone. If you can visualize it, then understanding is not far behind. http: //www. cassiopeiaproject. com/ To read more about the Theory of Special Relativity, you can start here: http: //www. phys. unsw. edu. au/einsteinlight/ http: //www. einstein-online. info/en/elementary/index. html http: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/Special_relativity

THE ETHER RIVER HISTORY OF ETHER MICHELSON-MORLEY EXPTS

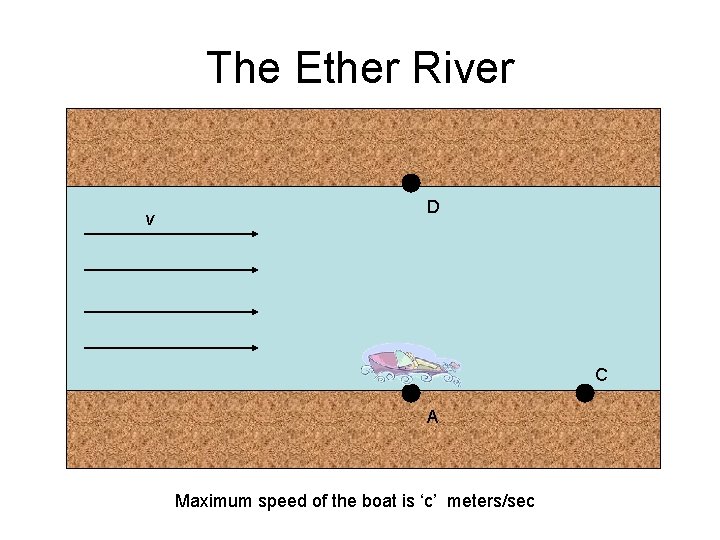

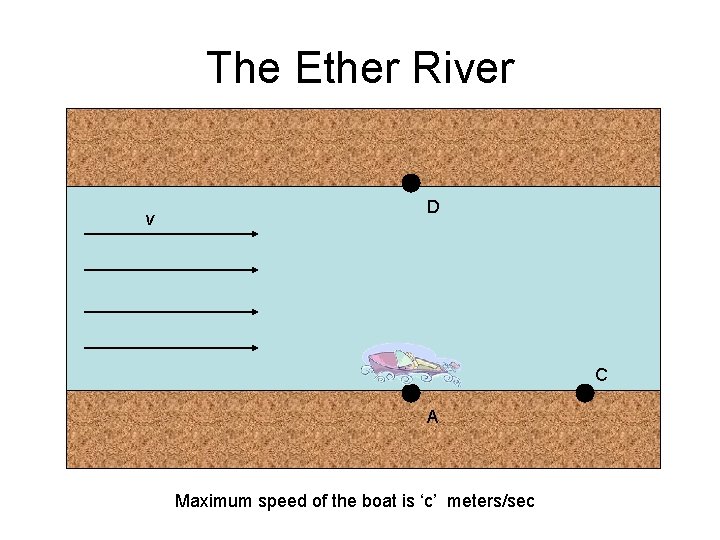

The Ether River v D C A Maximum speed of the boat is ‘c’ meters/sec

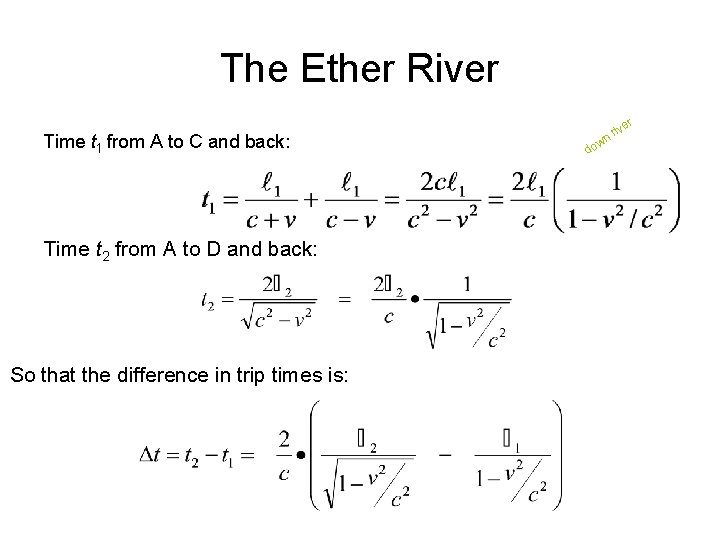

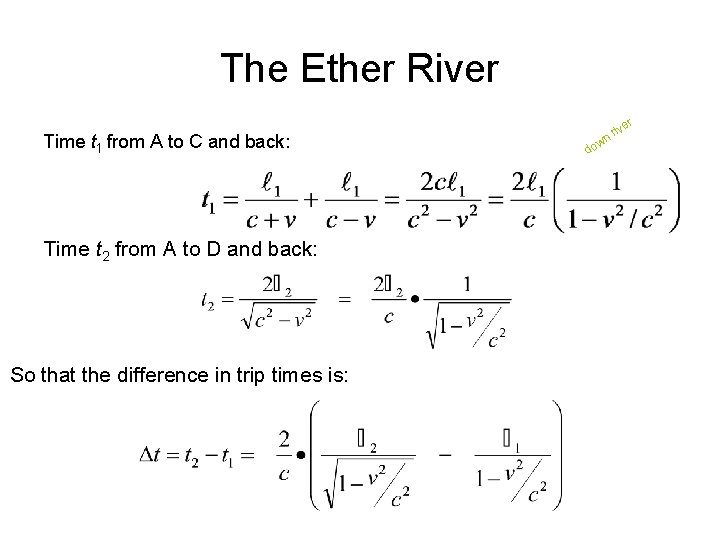

The Ether River r Time t 1 from A to C and back: Time t 2 from A to D and back: So that the difference in trip times is: do w ive nr

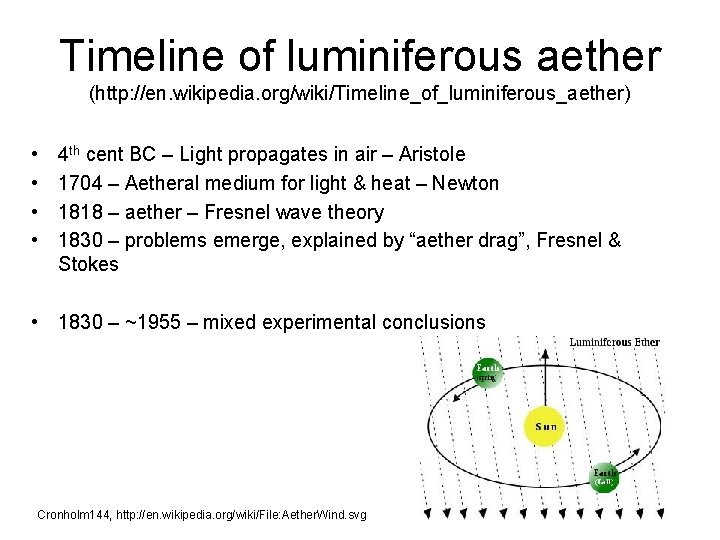

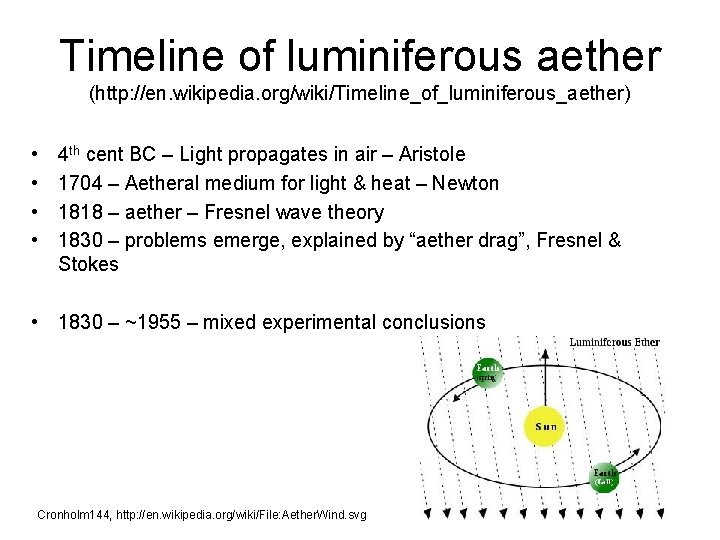

Timeline of luminiferous aether (http: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/Timeline_of_luminiferous_aether) • • 4 th cent BC – Light propagates in air – Aristole 1704 – Aetheral medium for light & heat – Newton 1818 – aether – Fresnel wave theory 1830 – problems emerge, explained by “aether drag”, Fresnel & Stokes • 1830 – ~1955 – mixed experimental conclusions Cronholm 144, http: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/File: Aether. Wind. svg

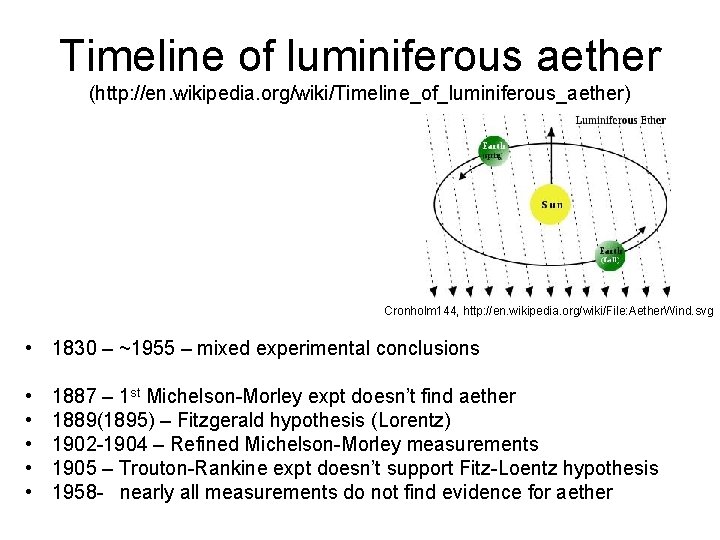

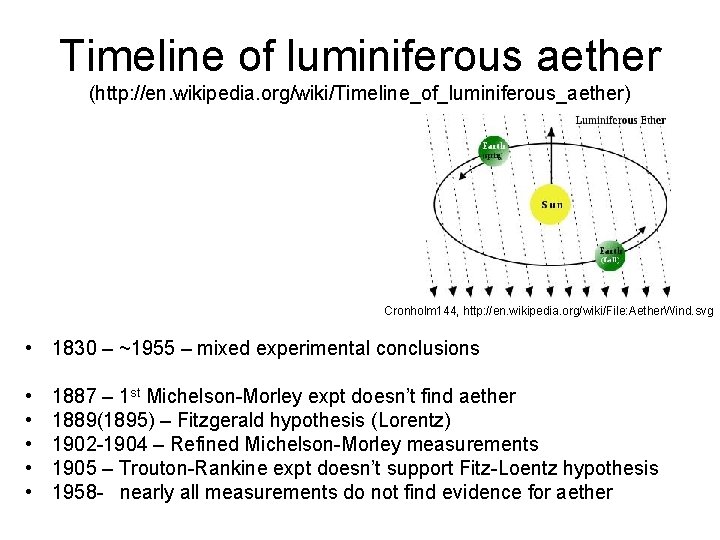

Timeline of luminiferous aether (http: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/Timeline_of_luminiferous_aether) Cronholm 144, http: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/File: Aether. Wind. svg • 1830 – ~1955 – mixed experimental conclusions • • • 1887 – 1 st Michelson-Morley expt doesn’t find aether 1889(1895) – Fitzgerald hypothesis (Lorentz) 1902 -1904 – Refined Michelson-Morley measurements 1905 – Trouton-Rankine expt doesn’t support Fitz-Loentz hypothesis 1958 - nearly all measurements do not find evidence for aether

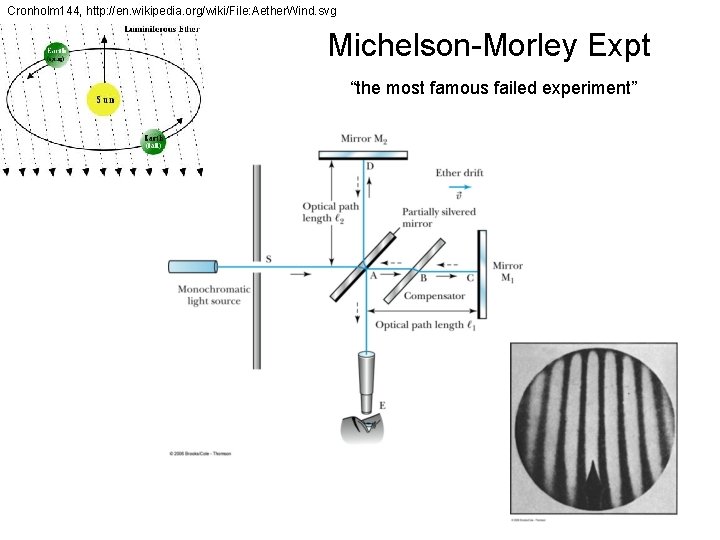

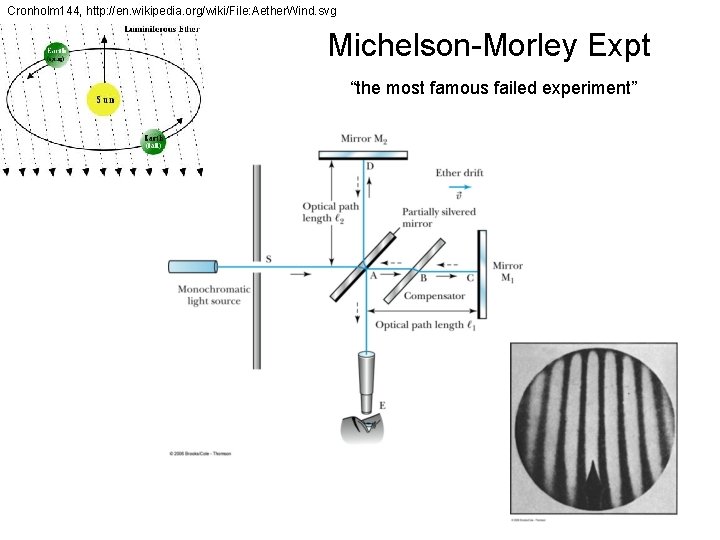

Cronholm 144, http: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/File: Aether. Wind. svg Michelson-Morley Expt “the most famous failed experiment”

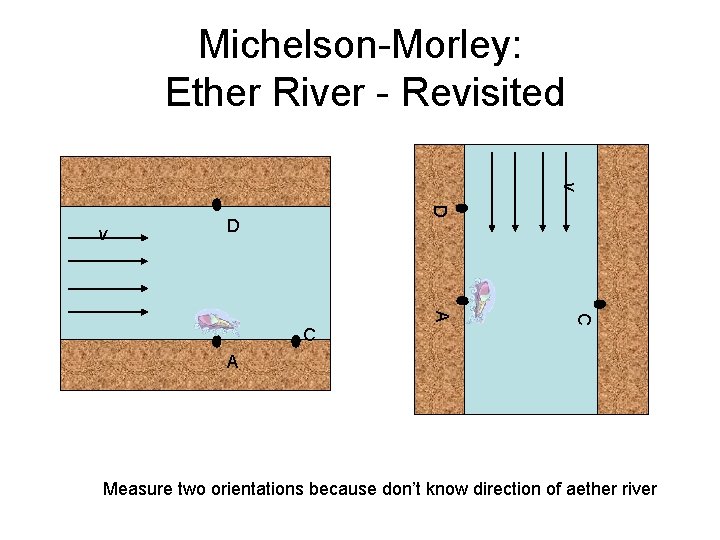

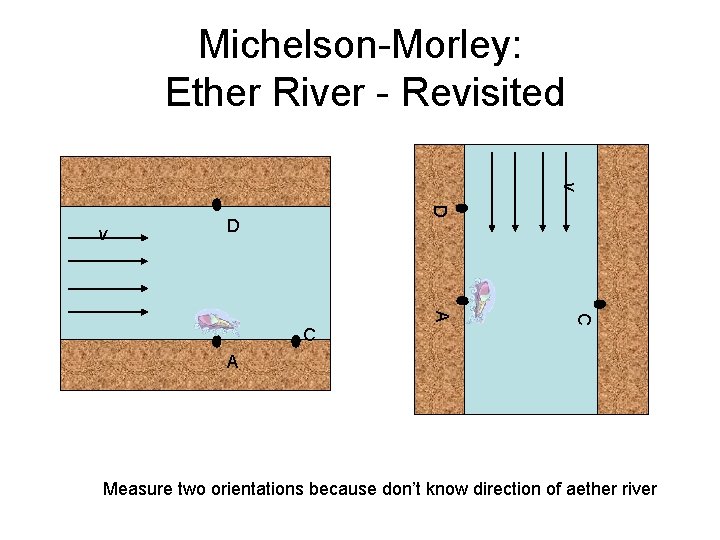

Michelson-Morley: Ether River - Revisited v D C A Measure two orientations because don’t know direction of aether river

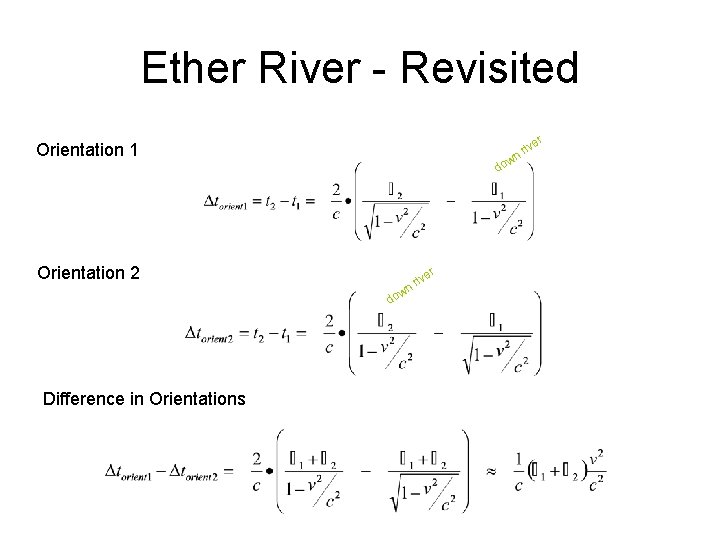

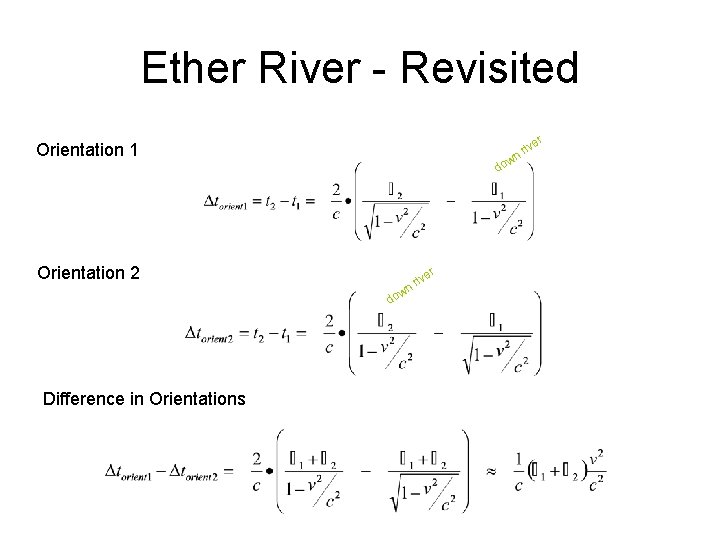

Ether River - Revisited Orientation 1 do Orientation 2 er d riv n ow Difference in Orientations w r ive r n

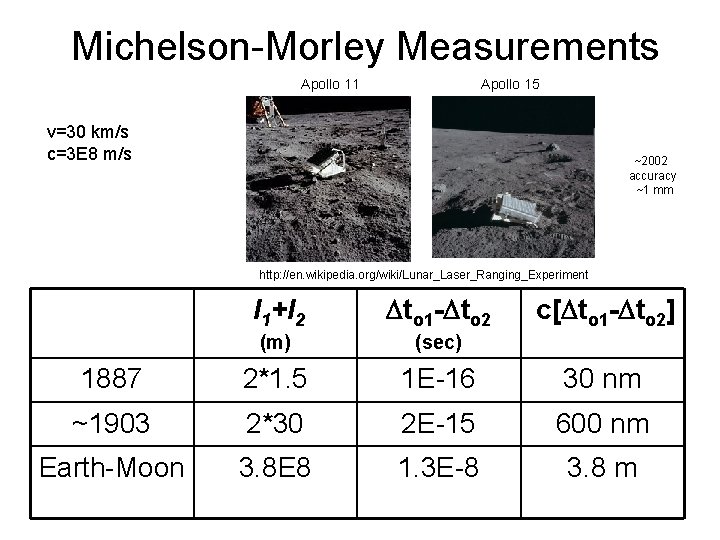

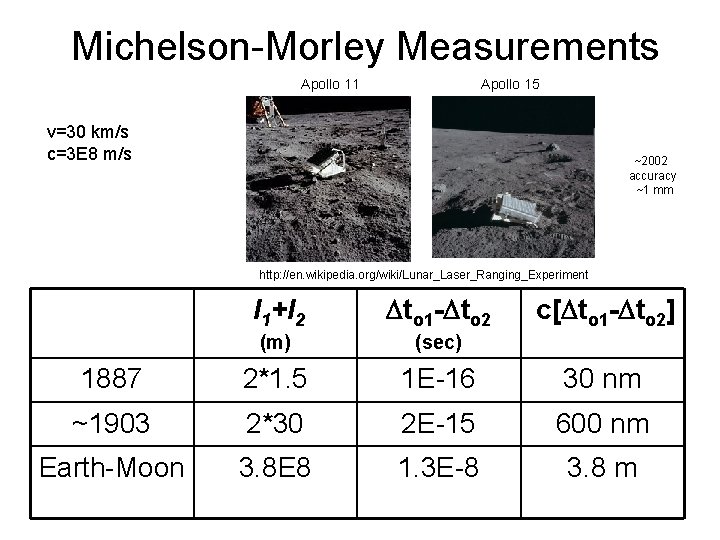

Michelson-Morley Measurements Apollo 11 Apollo 15 v=30 km/s c=3 E 8 m/s ~2002 accuracy ~1 mm http: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/Lunar_Laser_Ranging_Experiment l 1+l 2 Dto 1 -Dto 2 (m) (sec) 1887 2*1. 5 1 E-16 30 nm ~1903 2*30 2 E-15 600 nm Earth-Moon 3. 8 E 8 1. 3 E-8 3. 8 m c[Dto 1 -Dto 2]

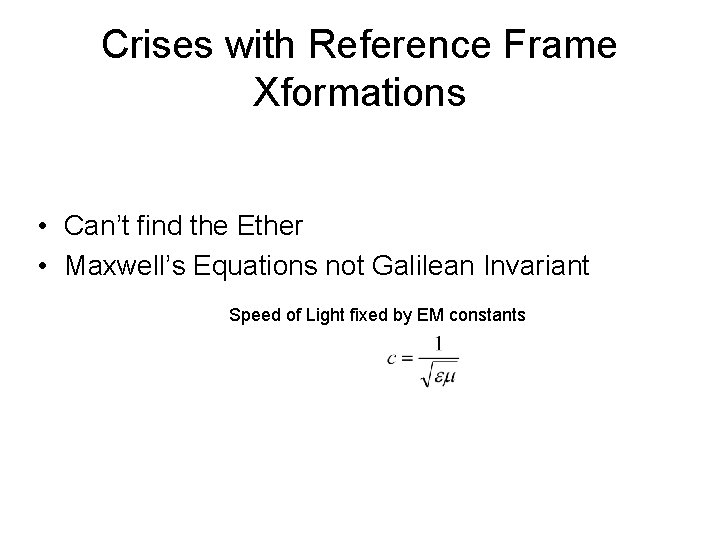

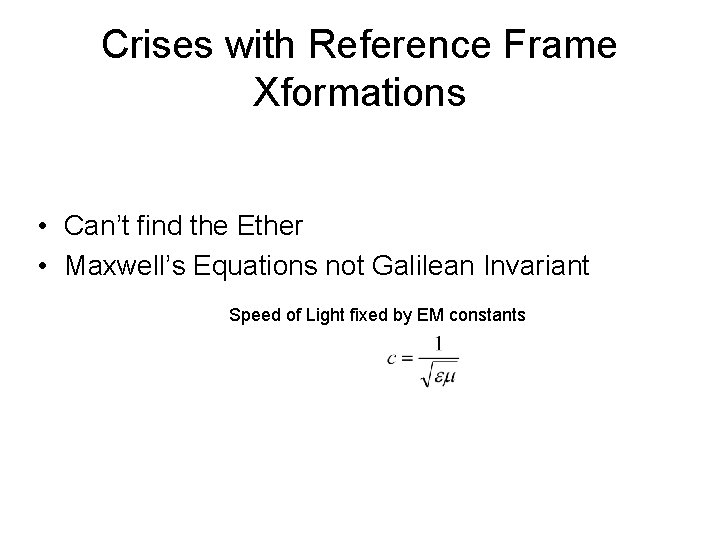

Crises with Reference Frame Xformations • Can’t find the Ether • Maxwell’s Equations not Galilean Invariant Speed of Light fixed by EM constants

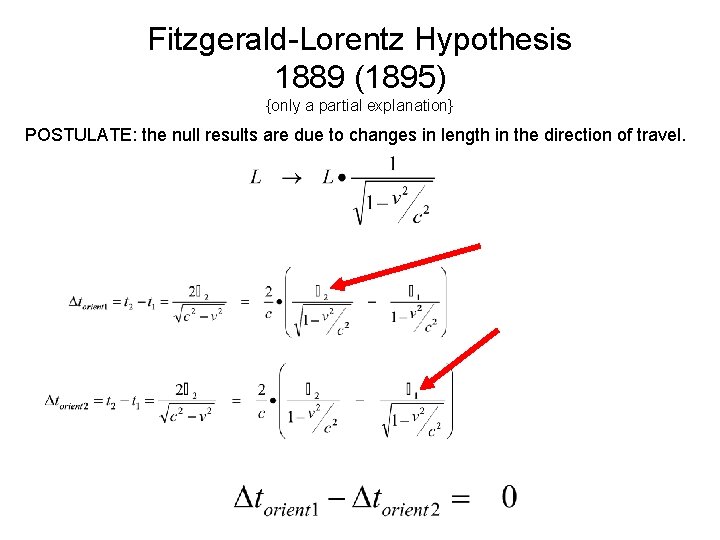

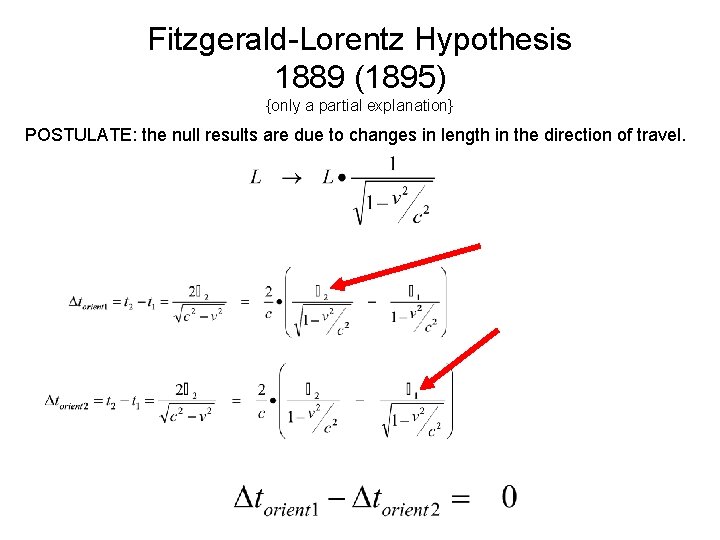

Fitzgerald-Lorentz Hypothesis 1889 (1895) {only a partial explanation} POSTULATE: the null results are due to changes in length in the direction of travel.

EINSTEIN’s 1905 POSTULATES • All laws for physics have the same functional form in any inertial reference frame • Speed of Light (in vacuum) is same in any inertial reference frame.

LORENTZ POSITION-TIME TRANSFORMATIONS

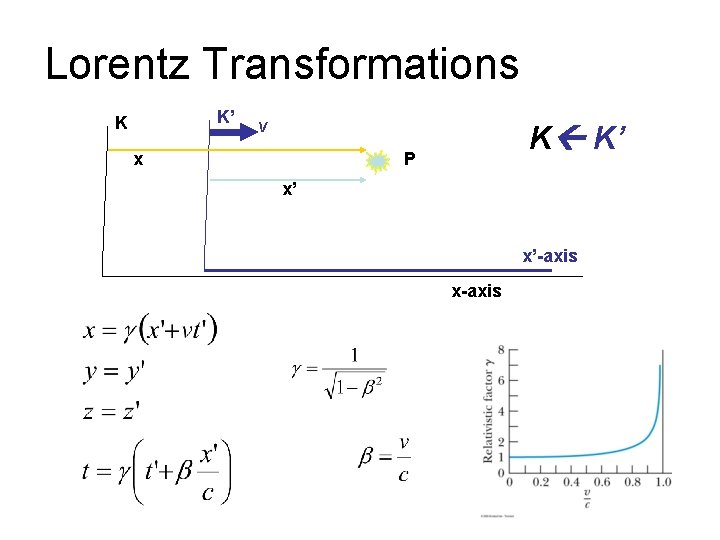

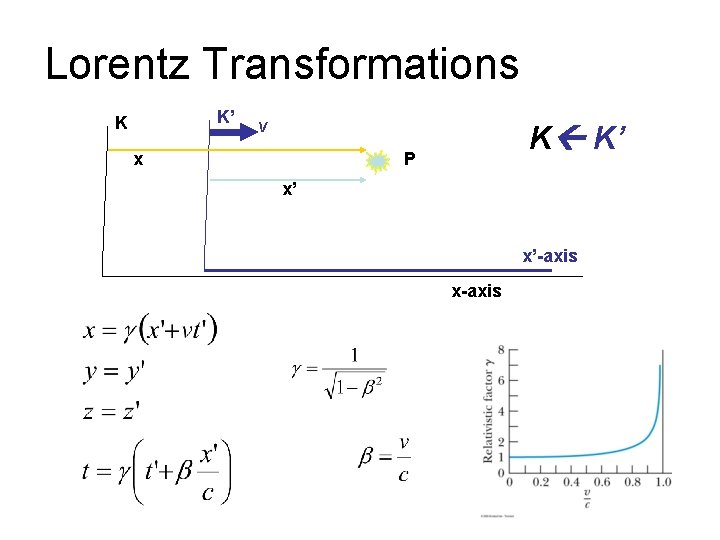

Lorentz Transformations K’ K v x K’ K P x’ x’-axis x-axis

Lorentz Transformations K’ K v x K K’ P x’ x’-axis x-axis

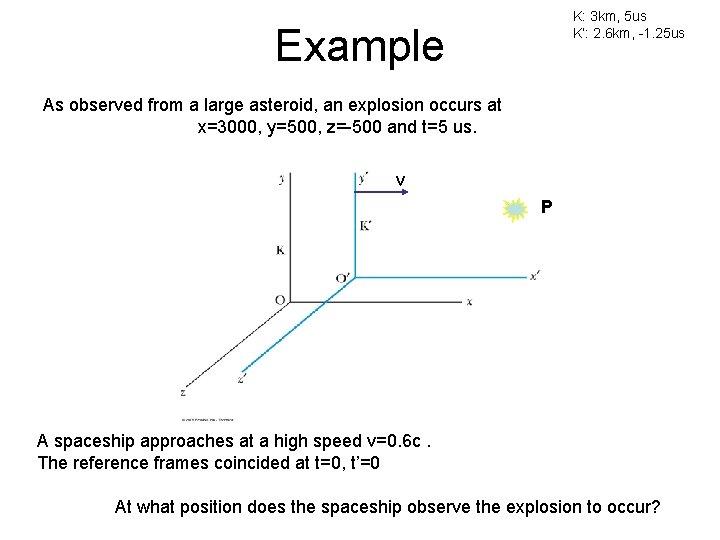

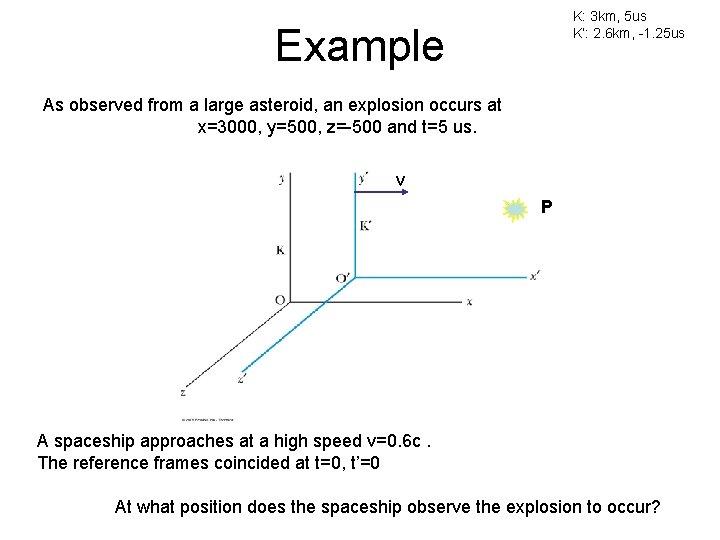

K: 3 km, 5 us K’: 2. 6 km, -1. 25 us Example As observed from a large asteroid, an explosion occurs at x=3000, y=500, z=-500 and t=5 us. v P A spaceship approaches at a high speed v=0. 6 c. The reference frames coincided at t=0, t’=0 At what position does the spaceship observe the explosion to occur?

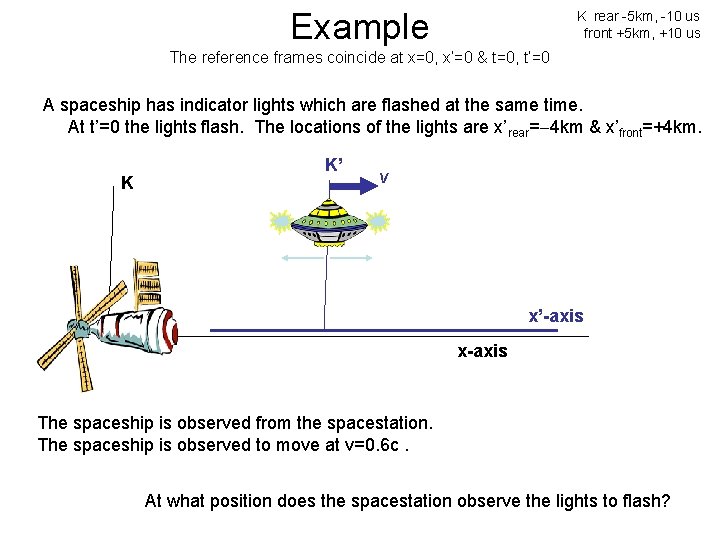

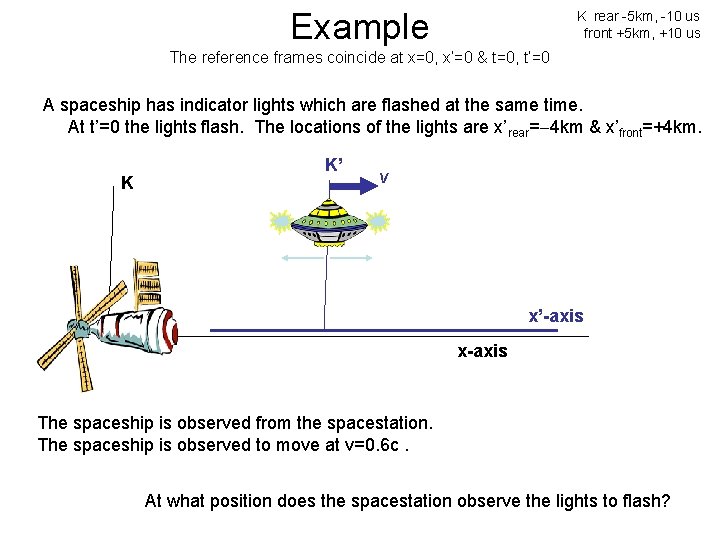

Example K rear -5 km, -10 us front +5 km, +10 us The reference frames coincide at x=0, x’=0 & t=0, t’=0 A spaceship has indicator lights which are flashed at the same time. At t’=0 the lights flash. The locations of the lights are x’rear=-4 km & x’front=+4 km. K K’ v x’-axis x-axis The spaceship is observed from the spacestation. The spaceship is observed to move at v=0. 6 c. At what position does the spacestation observe the lights to flash?

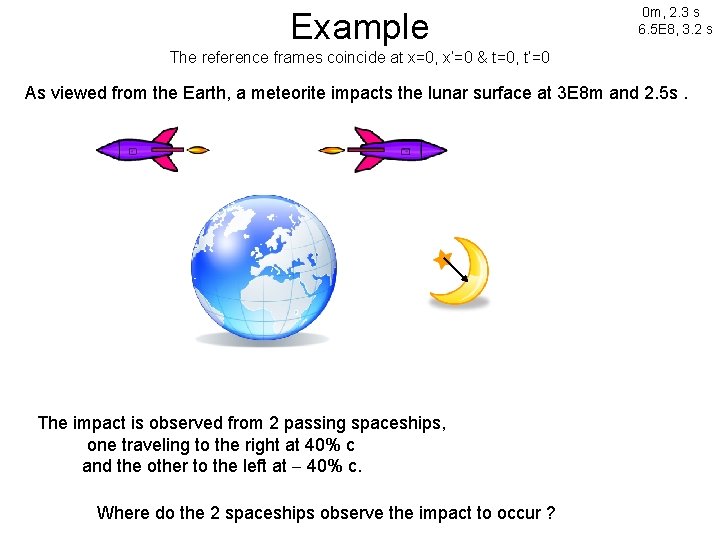

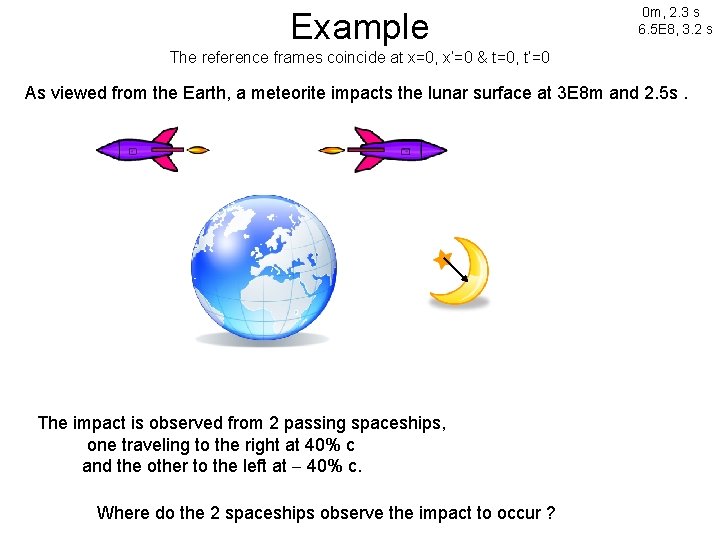

Example 0 m, 2. 3 s 6. 5 E 8, 3. 2 s The reference frames coincide at x=0, x’=0 & t=0, t’=0 As viewed from the Earth, a meteorite impacts the lunar surface at 3 E 8 m and 2. 5 s. The impact is observed from 2 passing spaceships, one traveling to the right at 40% c and the other to the left at - 40% c. Where do the 2 spaceships observe the impact to occur ?

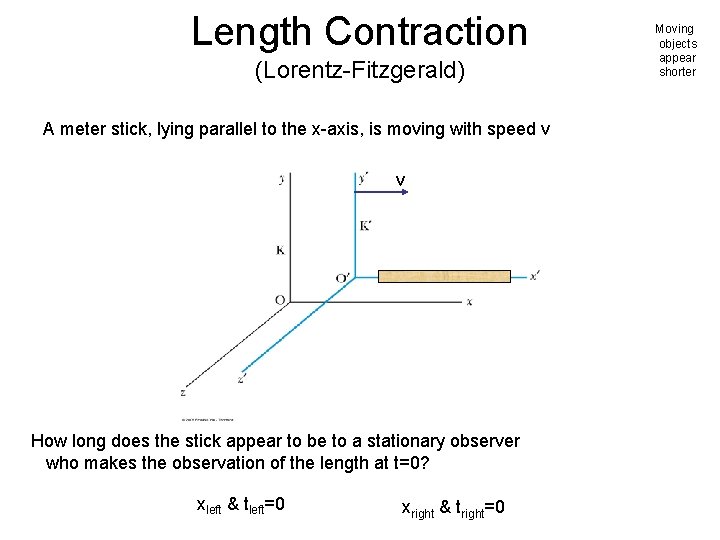

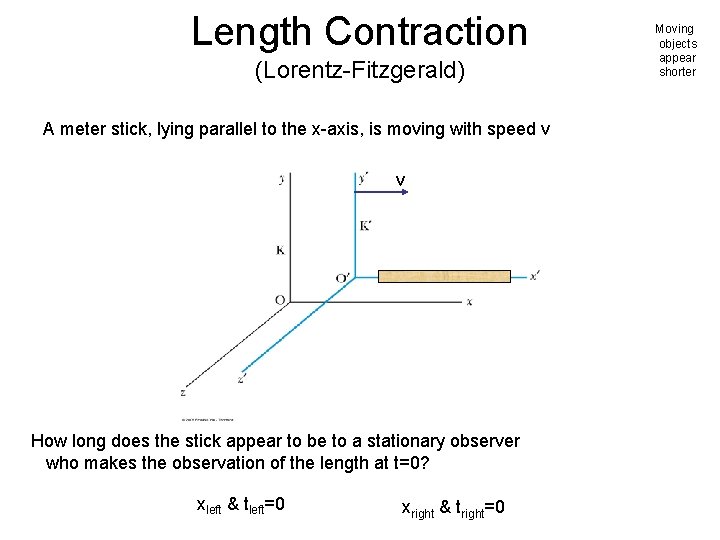

Length Contraction (Lorentz-Fitzgerald) A meter stick, lying parallel to the x-axis, is moving with speed v v How long does the stick appear to be to a stationary observer who makes the observation of the length at t=0? xleft & tleft=0 xright & tright=0 Moving objects appear shorter

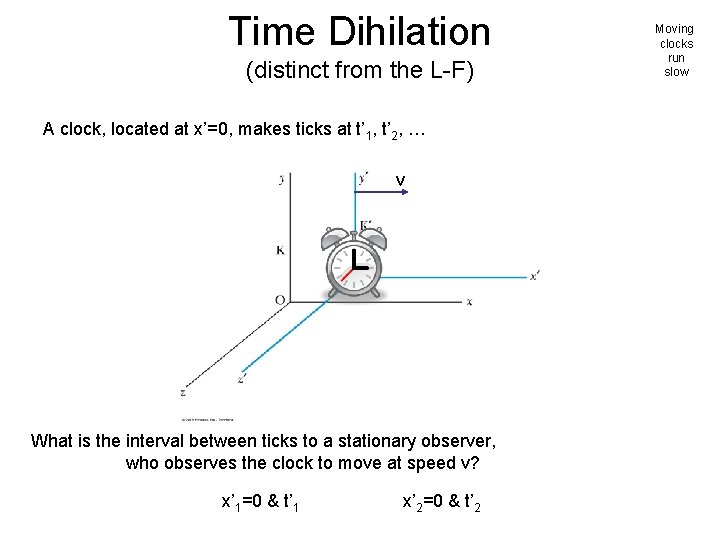

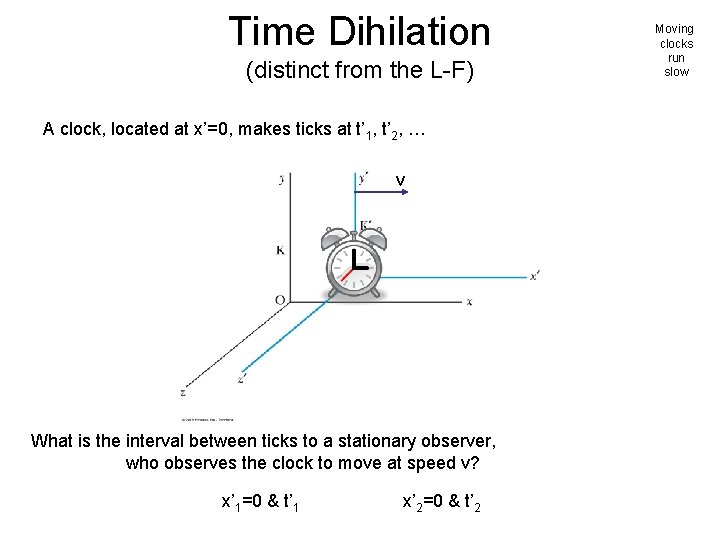

Time Dihilation (distinct from the L-F) A clock, located at x’=0, makes ticks at t’ 1, t’ 2, … v What is the interval between ticks to a stationary observer, who observes the clock to move at speed v? x’ 1=0 & t’ 1 x’ 2=0 & t’ 2 Moving clocks run slow

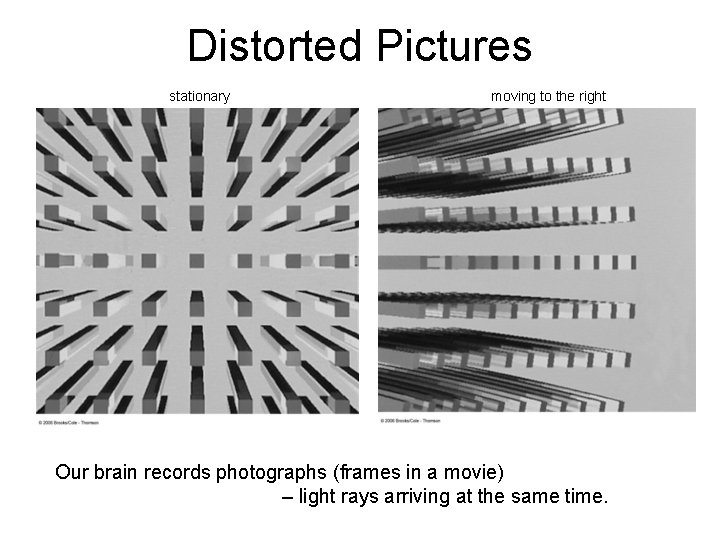

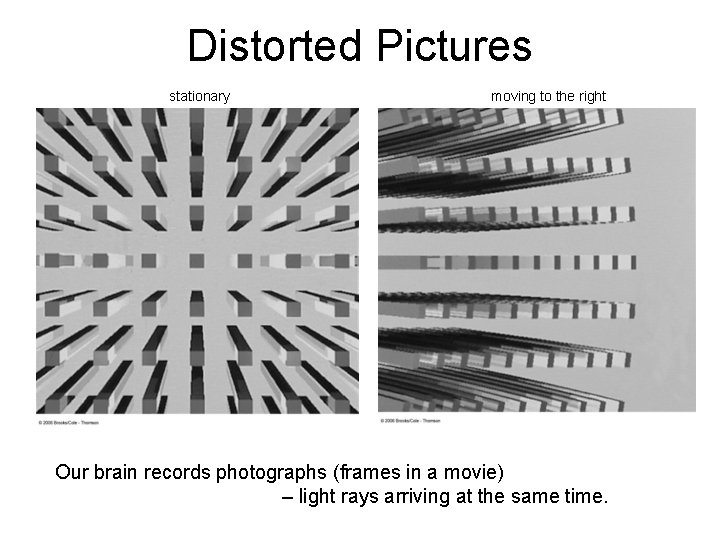

Distorted Pictures stationary moving to the right Our brain records photographs (frames in a movie) – light rays arriving at the same time.

“Jump to Light Speed”

Distorted Pictures

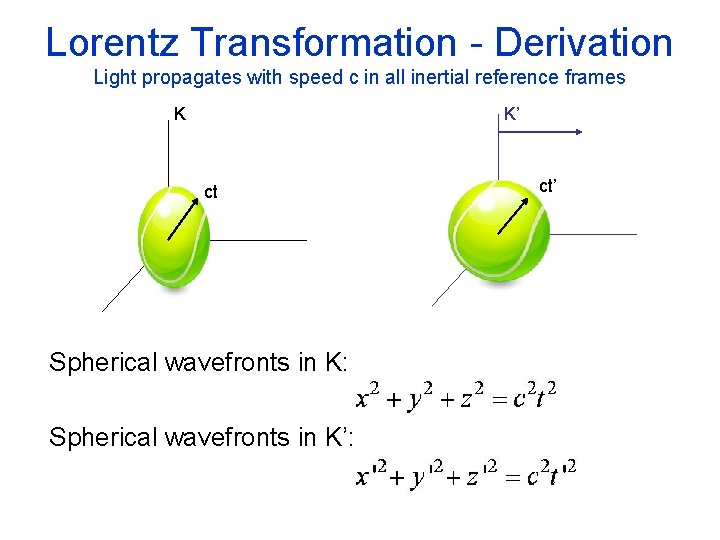

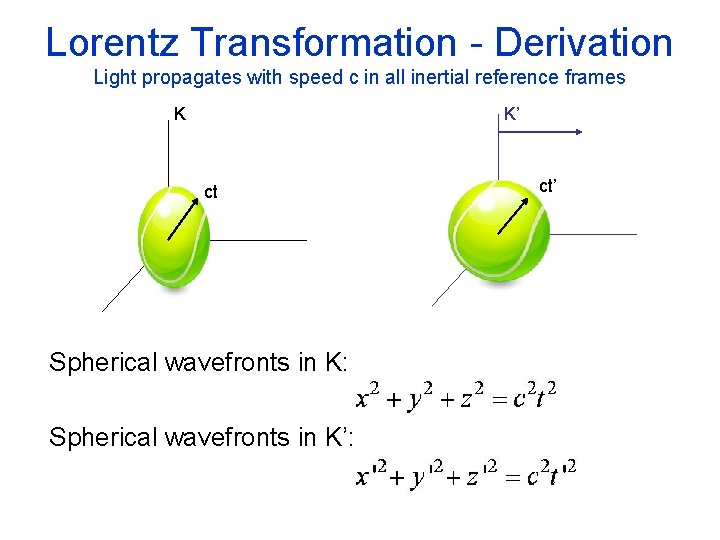

Lorentz Transformation - Derivation Light propagates with speed c in all inertial reference frames K K’ ct Spherical wavefronts in K: Spherical wavefronts in K’: ct’

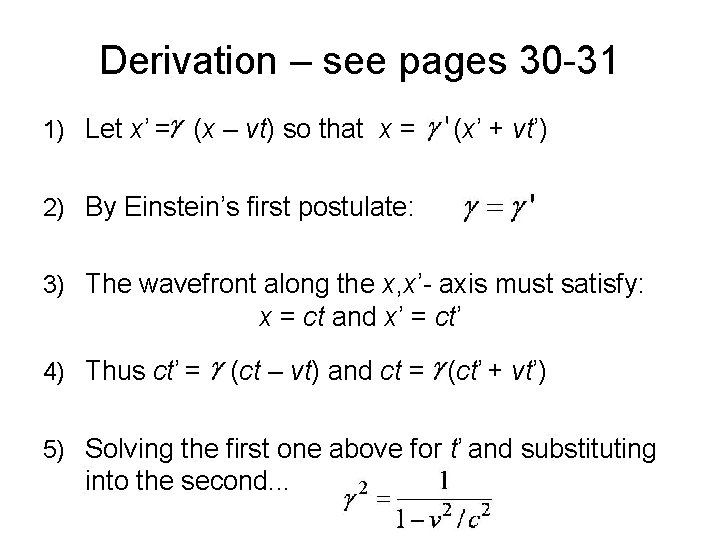

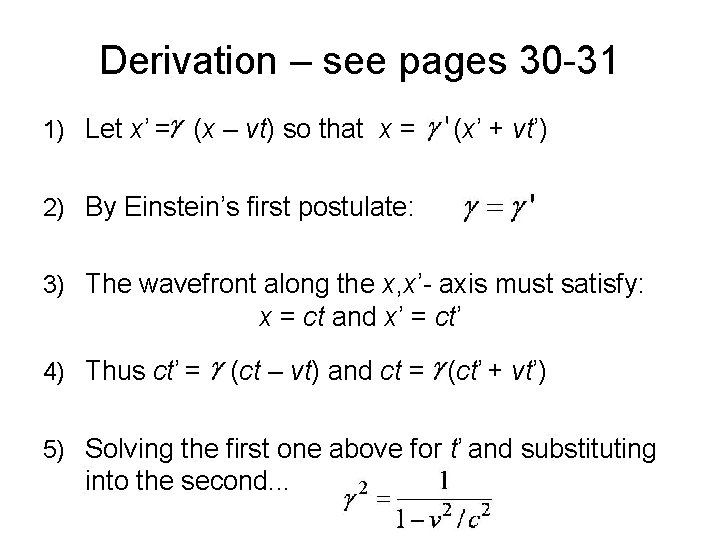

Derivation – see pages 30 -31 1) Let x’ = (x – vt) so that x = (x’ + vt’) 2) By Einstein’s first postulate: 3) The wavefront along the x, x’- axis must satisfy: x = ct and x’ = ct’ 4) Thus ct’ = (ct – vt) and ct = (ct’ + vt’) 5) Solving the first one above for t’ and substituting into the second. . .

Youtube clips (part 2) • Galilean/Classical Relativity Part 2 – The Cassiopeia Project http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=Wgs. Kl. Sn. UO 0 k The Cassiopeia Project is an effort to make high quality science videos available to everyone. If you can visualize it, then understanding is not far behind. http: //www. cassiopeiaproject. com/ To read more about the Theory of Special Relativity, you can start here: http: //www. phys. unsw. edu. au/einsteinlight/ http: //www. einstein-online. info/en/elementary/index. html http: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/Special_relativity

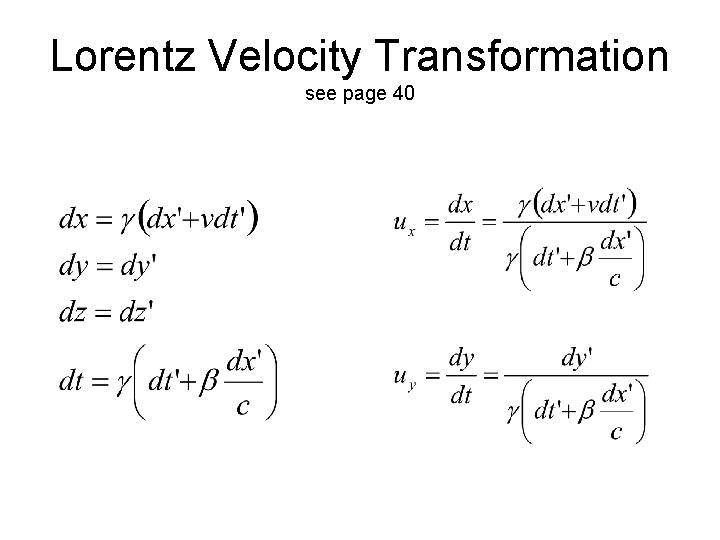

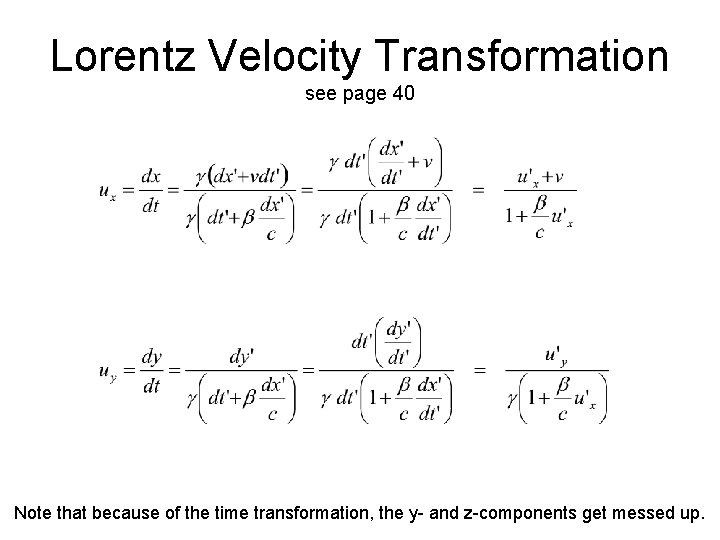

LORENTZ VELOCITY TRANSFORMATIONS

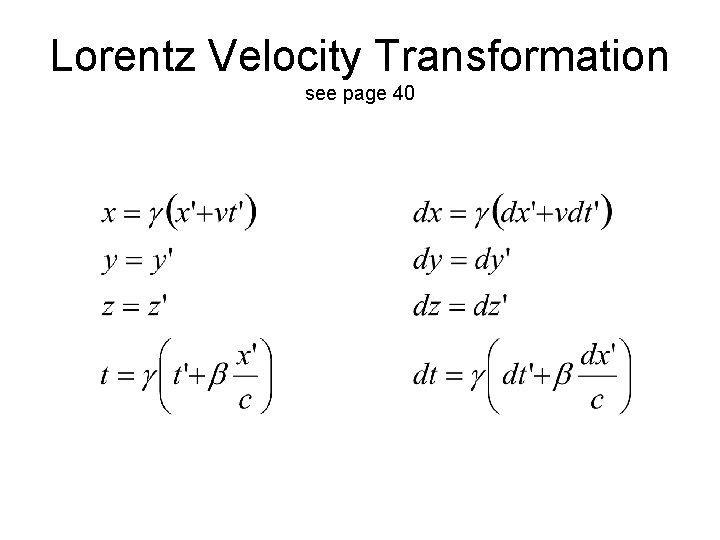

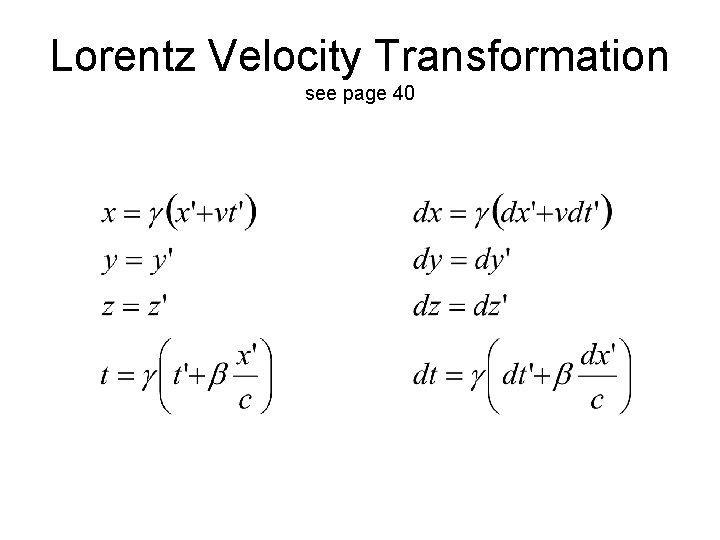

Lorentz Velocity Transformation see page 40

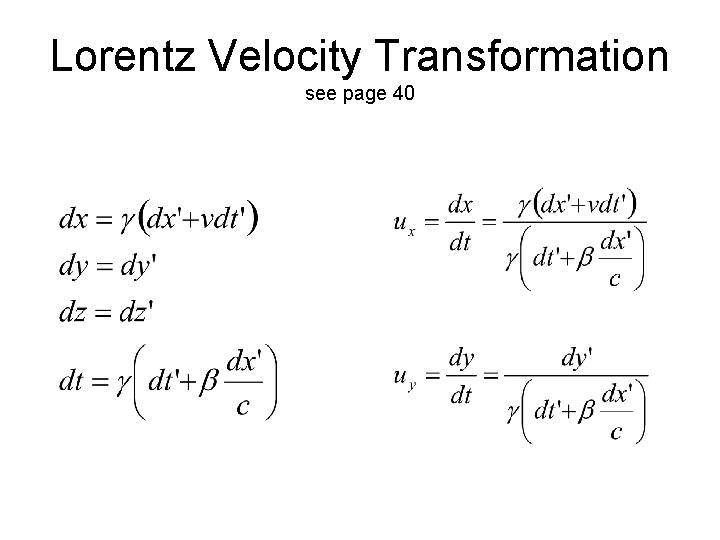

Lorentz Velocity Transformation see page 40

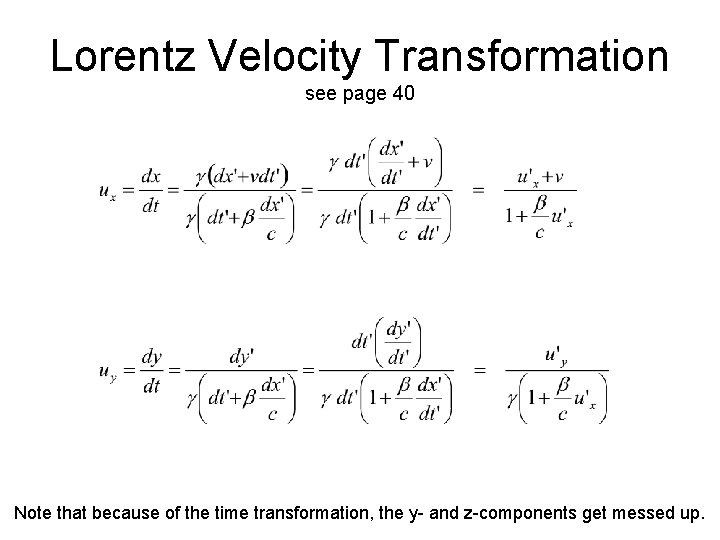

Lorentz Velocity Transformation see page 40 Note that because of the time transformation, the y- and z-components get messed up.

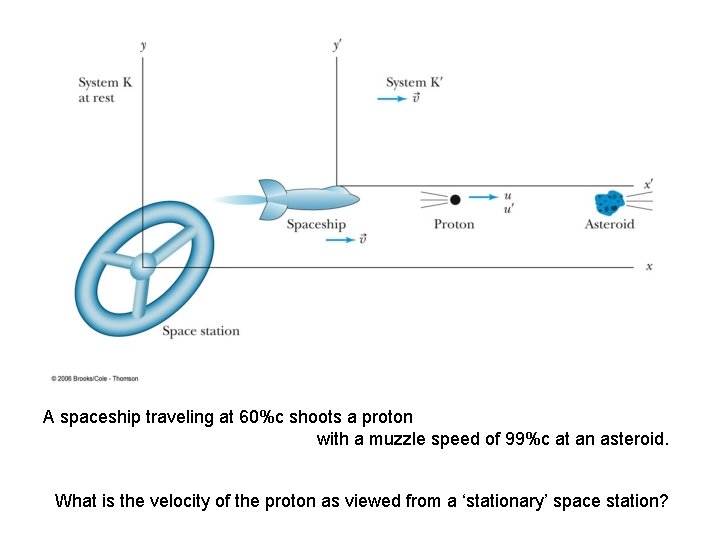

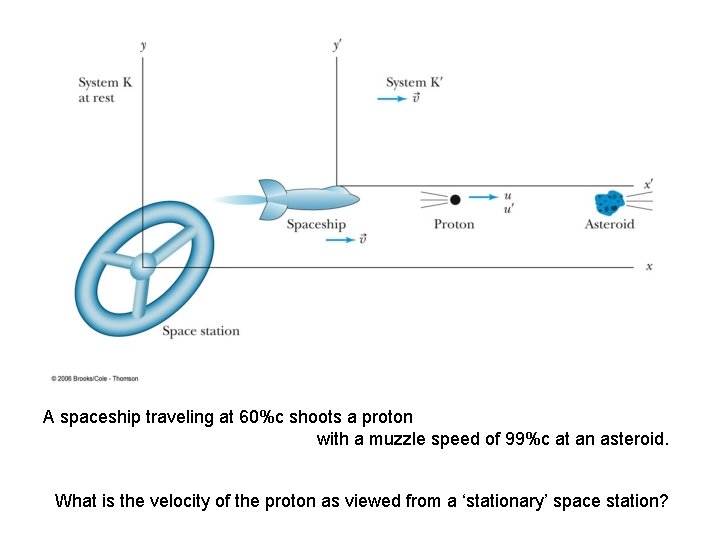

A spaceship traveling at 60%c shoots a proton with a muzzle speed of 99%c at an asteroid. What is the velocity of the proton as viewed from a ‘stationary’ space station?

MISC. LORENTZ TRANSFORMATION EXAMPLES

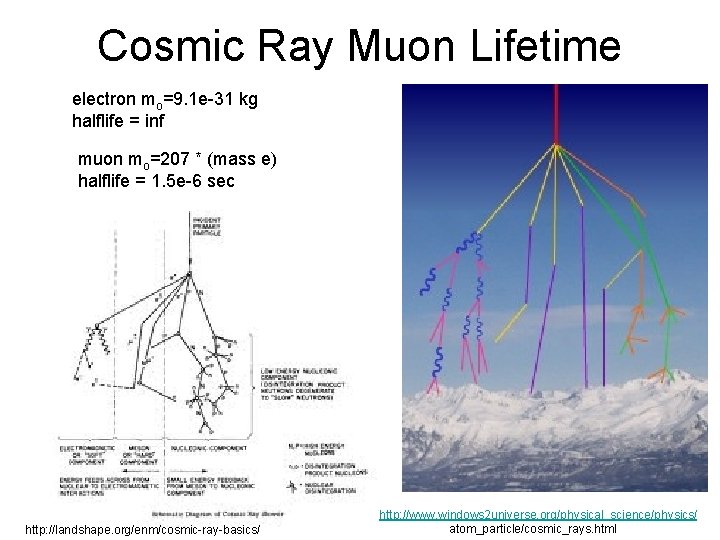

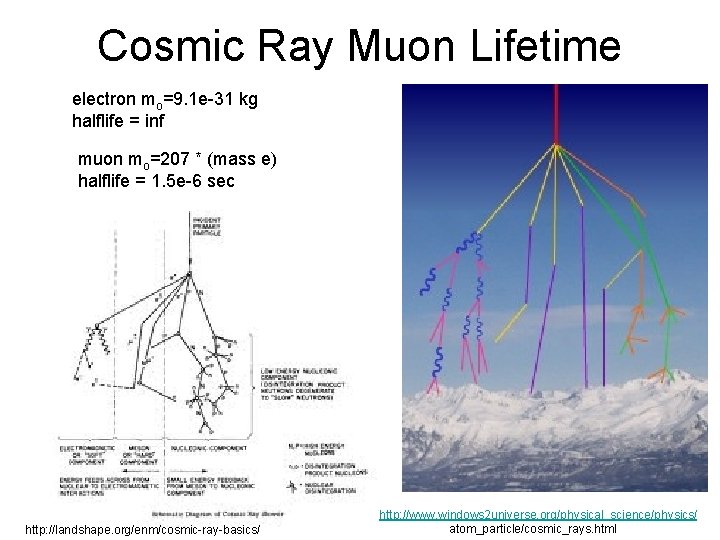

Cosmic Ray Muon Lifetime electron mo=9. 1 e-31 kg halflife = inf muon mo=207 * (mass e) halflife = 1. 5 e-6 sec http: //landshape. org/enm/cosmic-ray-basics/ http: //www. windows 2 universe. org/physical_science/physics/ atom_particle/cosmic_rays. html

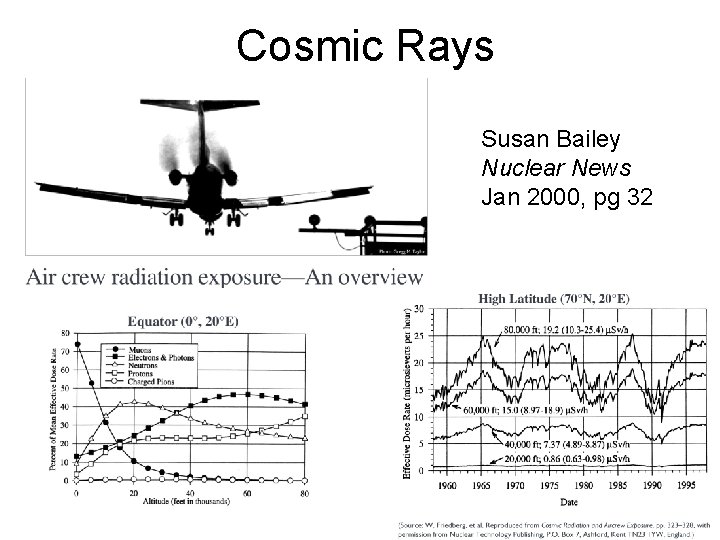

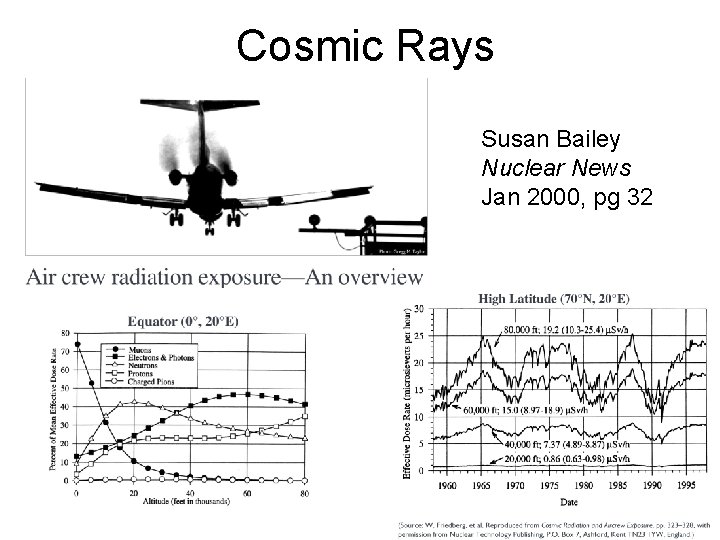

Cosmic Rays Susan Bailey Nuclear News Jan 2000, pg 32

Cosmic Ray references Cosmic Ray Muon Measurements http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=yj. E 5 LHfq. EQI http: //www. ans. org/pubs/magazines/nn/docs/2000 -1 -3. pdf http: //pdg. lbl. gov/2011/reviews/rpp 2011 -rev-cosmic-rays. pdf http: //hyperphysics. phy-astr. gsu. edu ashsd. afacwa. org/ radation cosmic rays

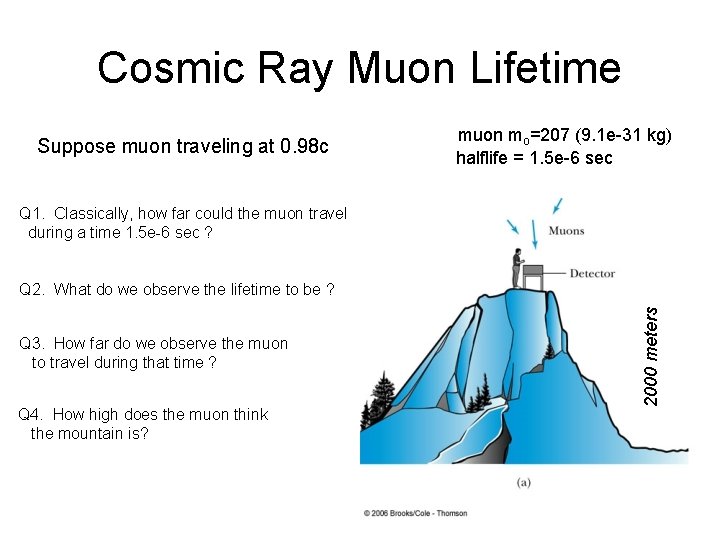

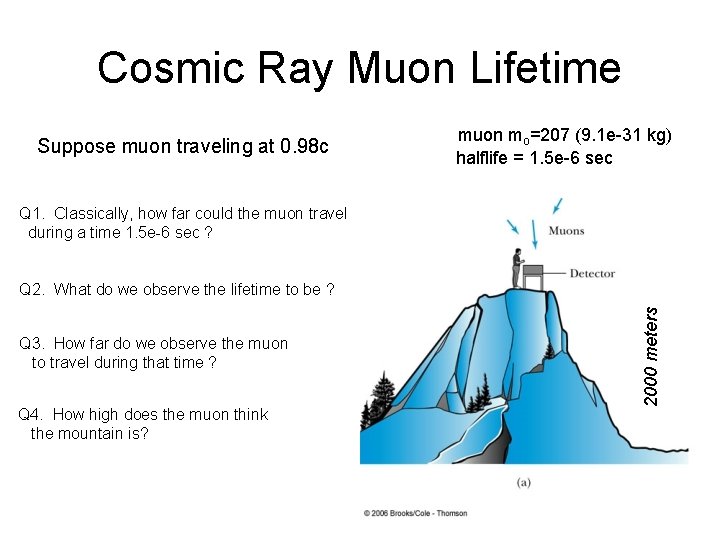

Cosmic Ray Muon Lifetime Suppose muon traveling at 0. 98 c muon mo=207 (9. 1 e-31 kg) halflife = 1. 5 e-6 sec Q 1. Classically, how far could the muon travel during a time 1. 5 e-6 sec ? Q 3. How far do we observe the muon to travel during that time ? Q 4. How high does the muon think the mountain is? 2000 meters Q 2. What do we observe the lifetime to be ?

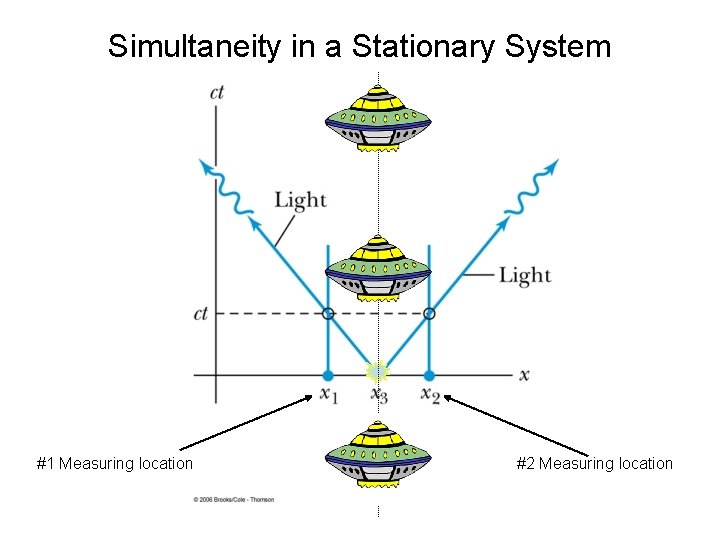

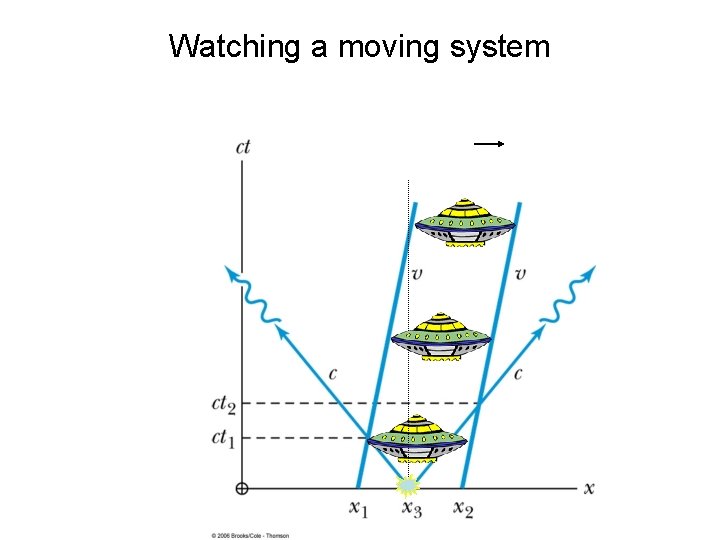

Simultaneity • http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=wteiuxyqto. M • http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=KYWM 2 o. Zgi 4 E

Atomic Clock Measurements • http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=c. Dvm. N_Pw 96 A • d

Twin Paradox Video Clip http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=A 0 ji. Y-CZ 6 YA What’s the correct explanation of the paradox? Reliable Discussion at http: //www. phys. unsw. edu. au/einsteinlight/jw/module 4_twin_paradox. htm

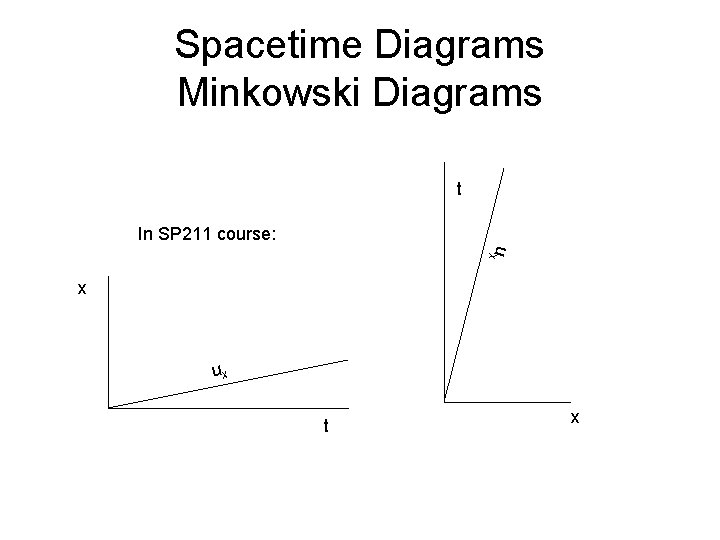

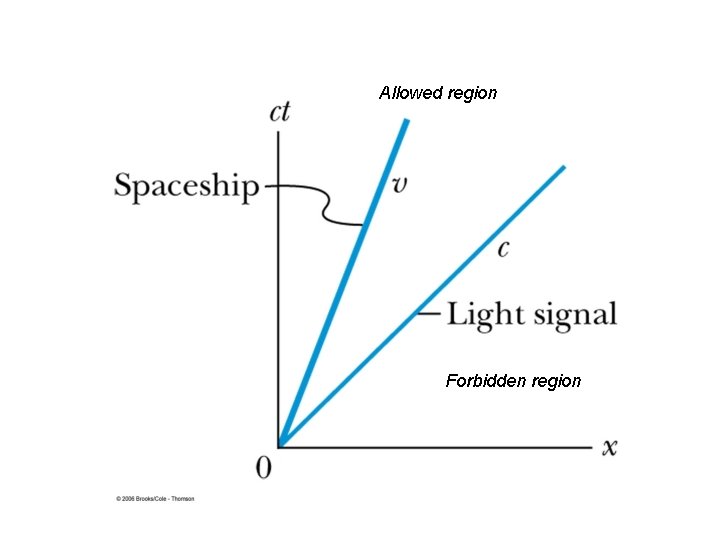

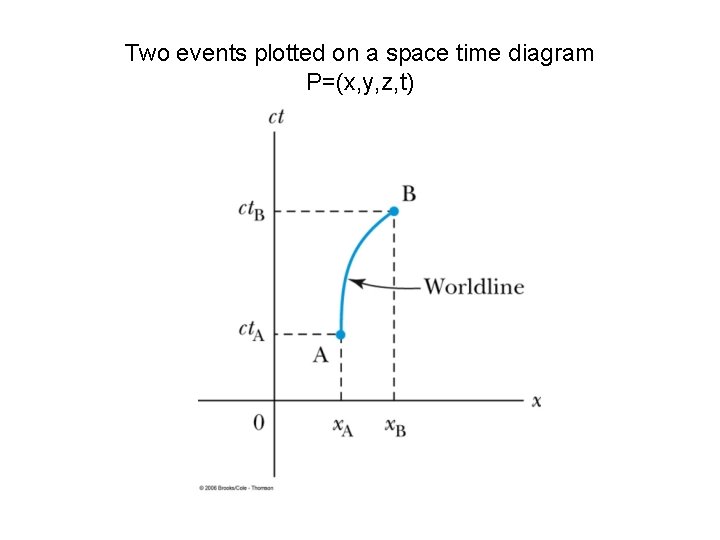

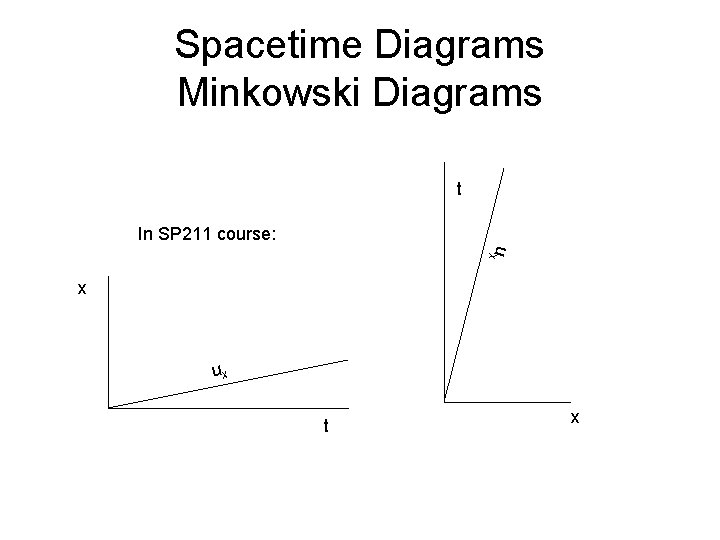

Spacetime Diagrams Minkowski Diagrams t In SP 211 course: ux x ux t x

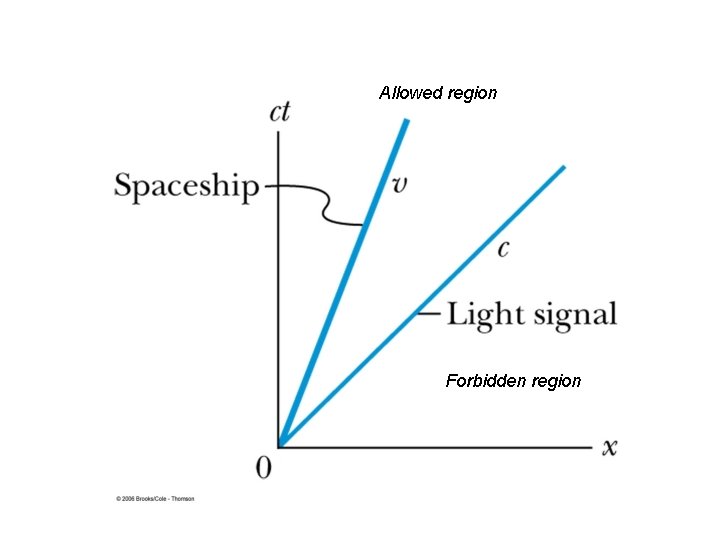

Allowed region Forbidden region

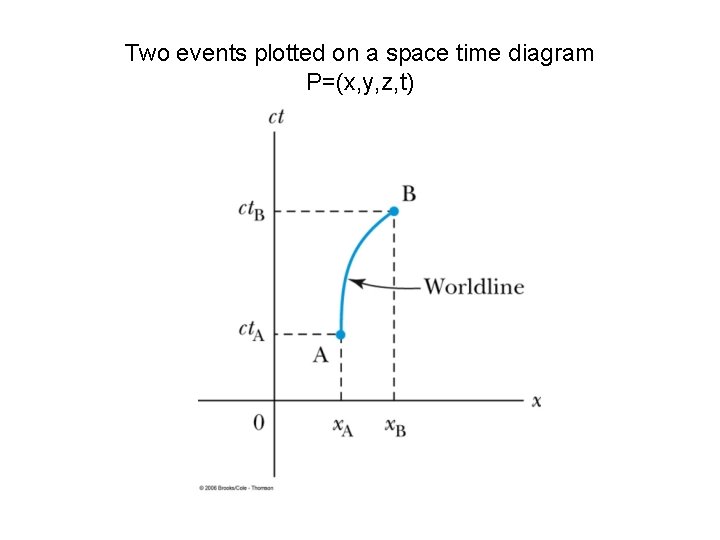

Two events plotted on a space time diagram P=(x, y, z, t)

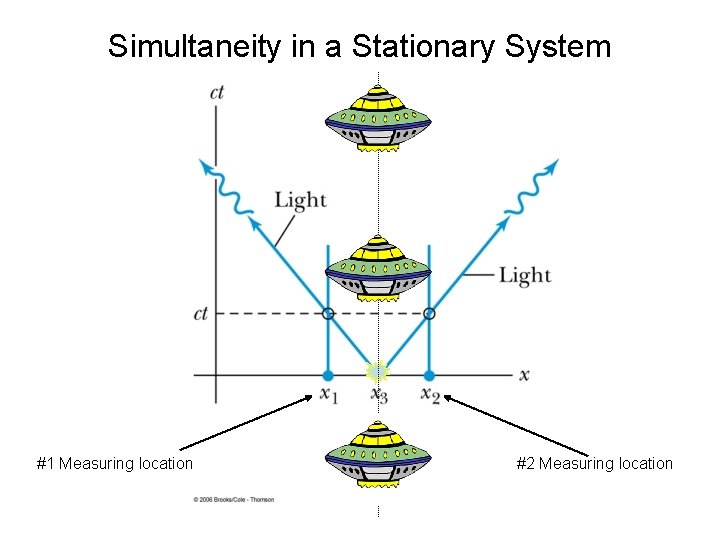

Simultaneity in a Stationary System #1 Measuring location #2 Measuring location

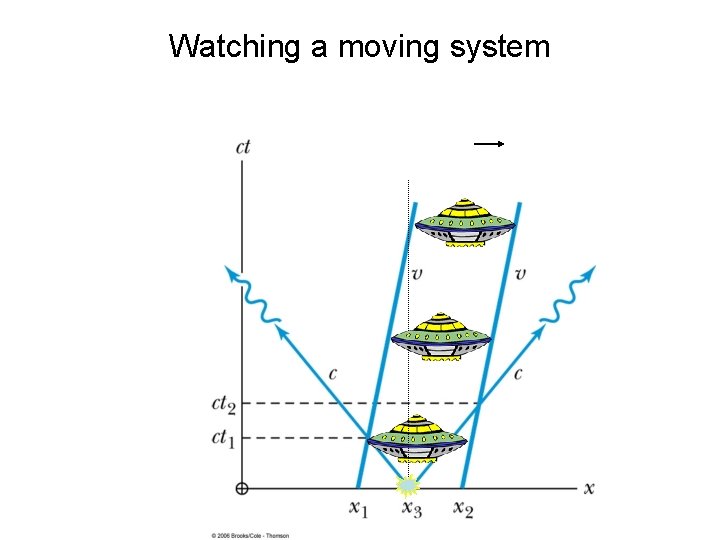

Watching a moving system

Animated Minkowski Diagrams • http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=C 2 VMO 7 pc. Whg – (uses Minkowski space diagrams, but with time axis pointing down, opposite from figures in textbook. )

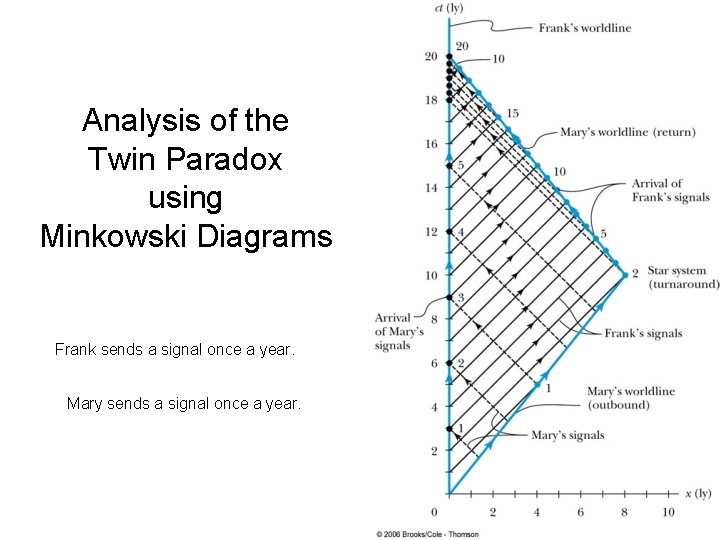

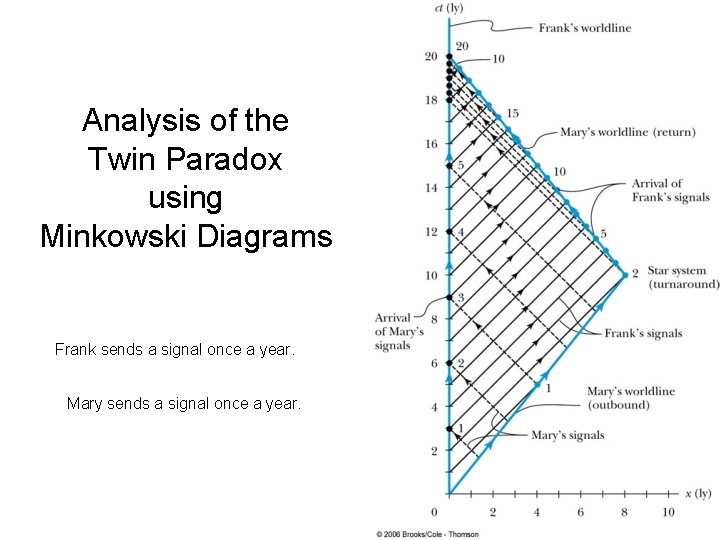

Analysis of the Twin Paradox using Minkowski Diagrams Frank sends a signal once a year. Mary sends a signal once a year.

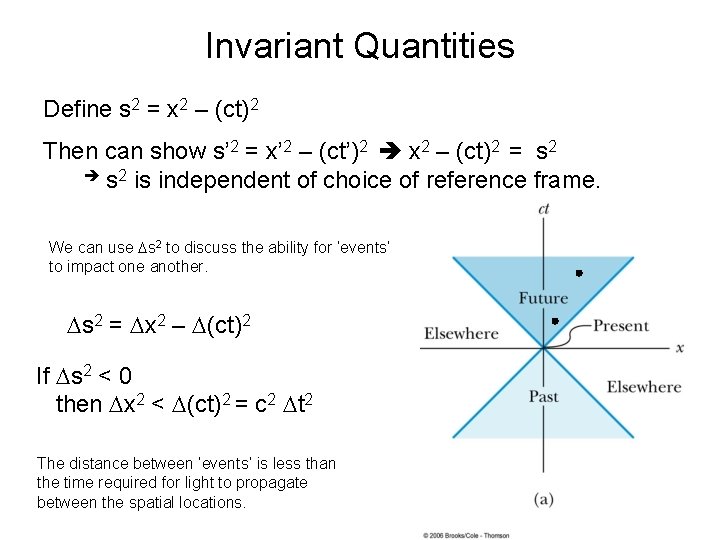

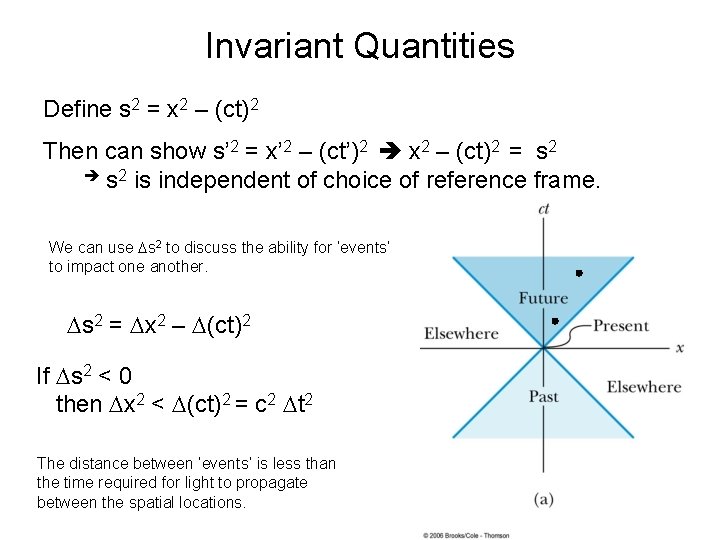

Invariant Quantities Define s 2 = x 2 – (ct)2 Then can show s’ 2 = x’ 2 – (ct’)2 x 2 – (ct)2 = s 2 is independent of choice of reference frame. We can use Ds 2 to discuss the ability for ‘events’ to impact one another. Ds 2 = Dx 2 – D(ct)2 If Ds 2 < 0 then Dx 2 < D(ct)2 = c 2 Dt 2 The distance between ‘events’ is less than the time required for light to propagate between the spatial locations.

RELATIVISTIC MOMENTUM Style 1. Sandin’s Development Style 2. Rex & Thorton’s Development

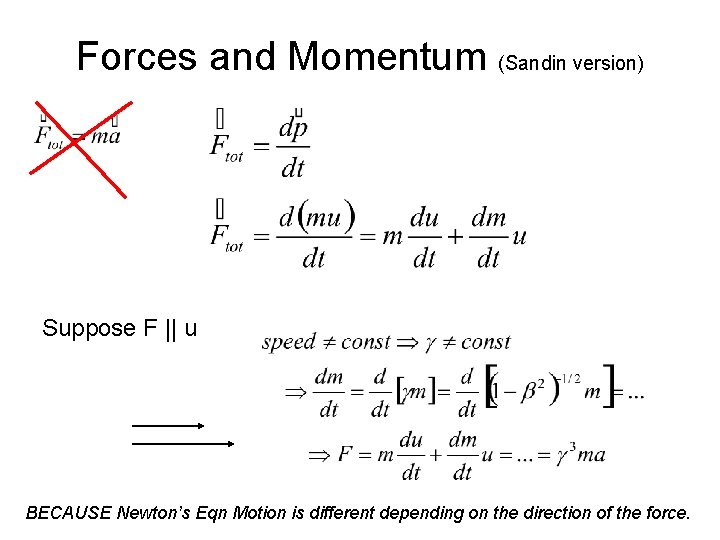

The following 4 slides present Sandin’s treatment of momentum in Special Relativity

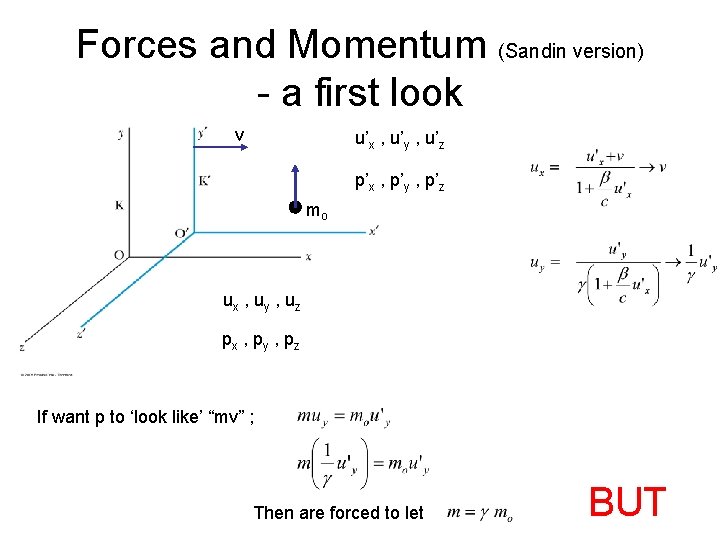

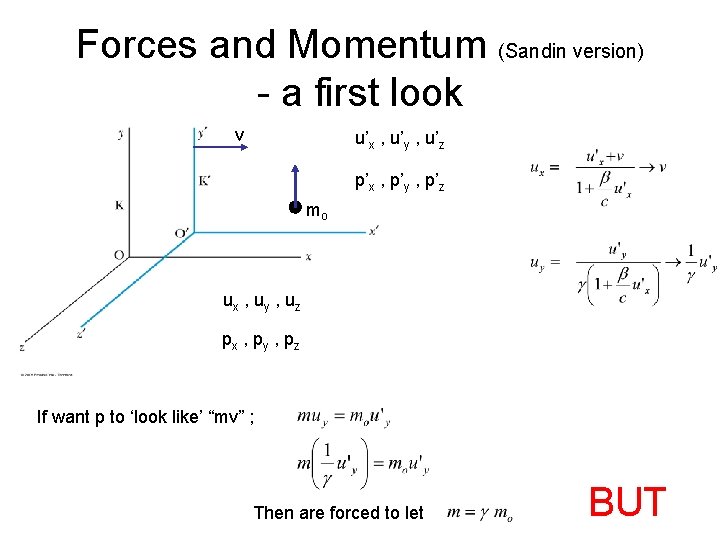

Forces and Momentum (Sandin version) - a first look v u’x , u’y , u’z p’x , p’y , p’z mo ux , u y , u z px , p y , p z If want p to ‘look like’ “mv” ; Then are forced to let BUT

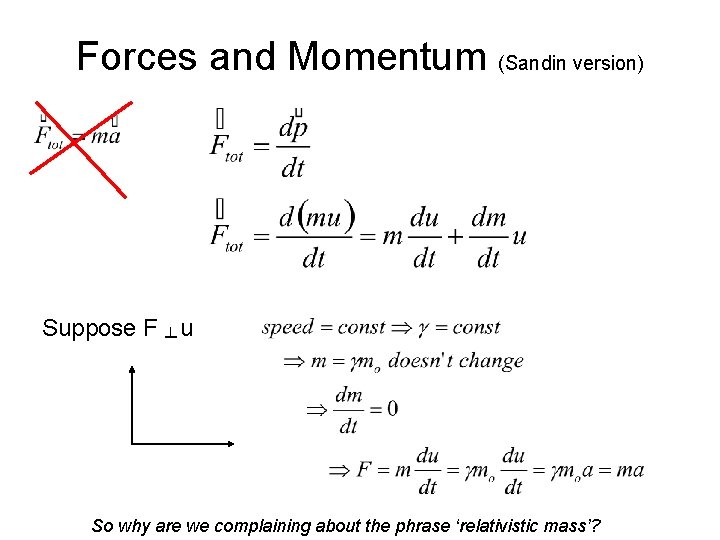

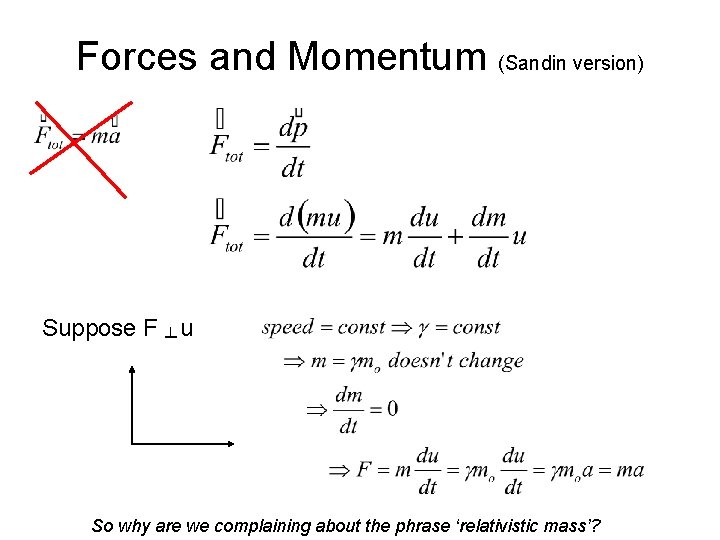

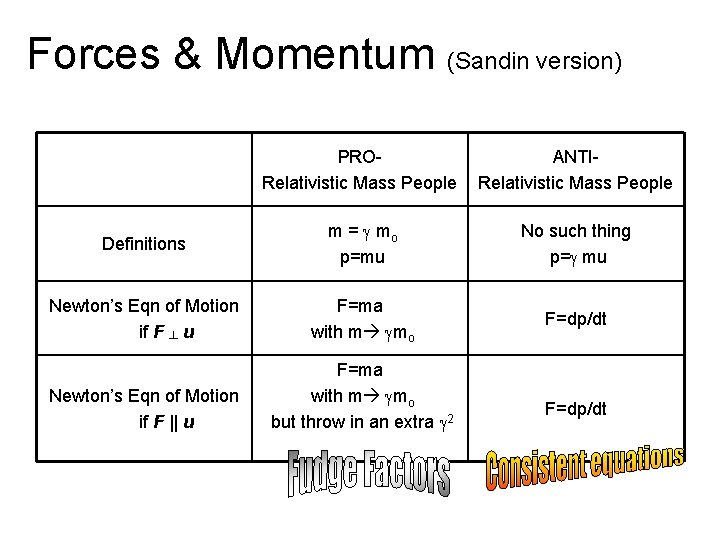

Forces and Momentum (Sandin version) Suppose F ┴ u So why are we complaining about the phrase ‘relativistic mass’?

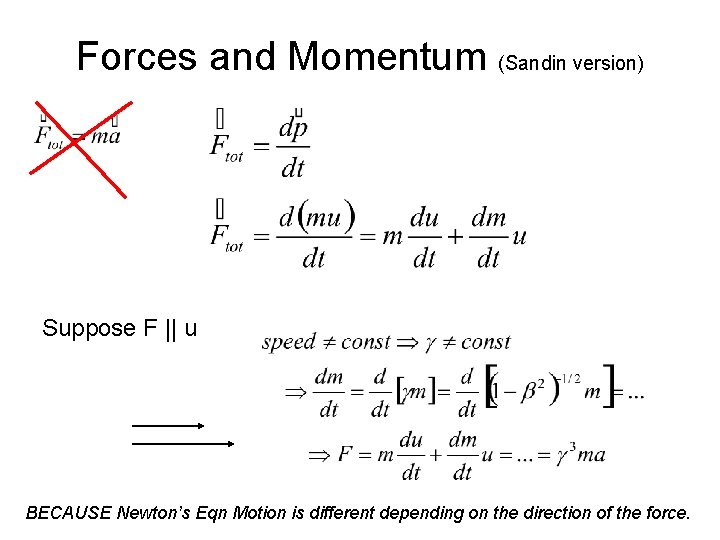

Forces and Momentum (Sandin version) Suppose F || u BECAUSE Newton’s Eqn Motion is different depending on the direction of the force.

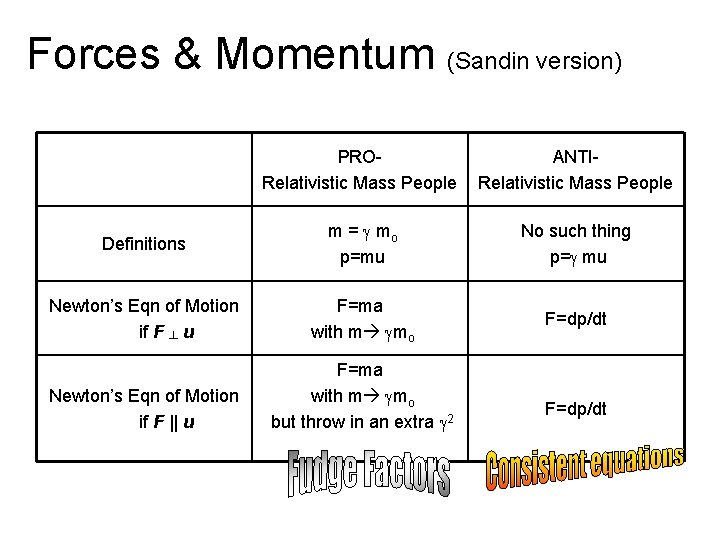

Forces & Momentum (Sandin version) PRORelativistic Mass People ANTIRelativistic Mass People Definitions m = g mo p=mu No such thing p=g mu Newton’s Eqn of Motion if F ┴ u F=ma with m gmo F=dp/dt Newton’s Eqn of Motion if F || u F=ma with m gmo but throw in an extra g 2 F=dp/dt

The following 9 slides present Rex & Thorton’s treatment of momentum in Special Relativity

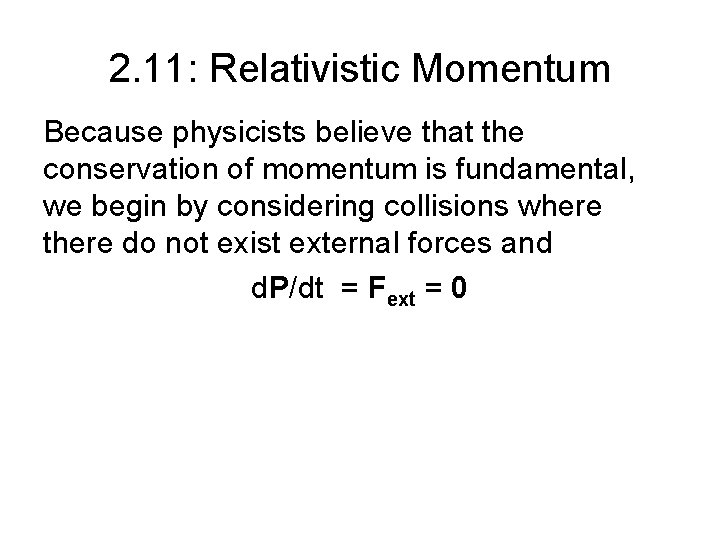

2. 11: Relativistic Momentum Because physicists believe that the conservation of momentum is fundamental, we begin by considering collisions where there do not exist external forces and d. P/dt = Fext = 0

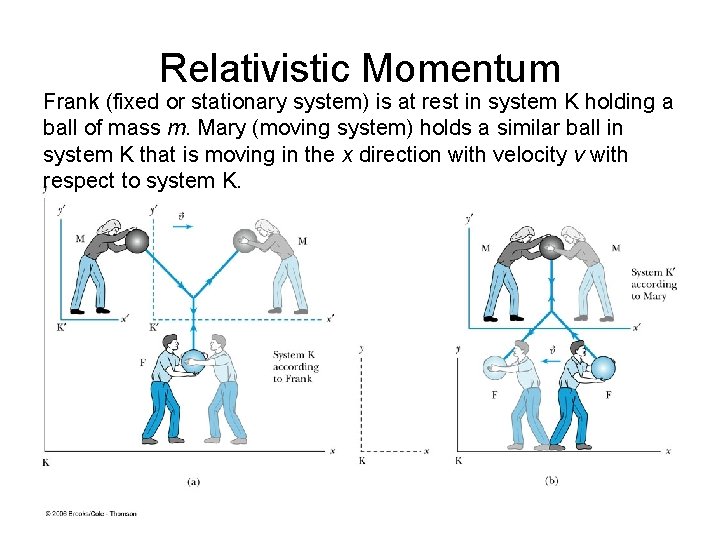

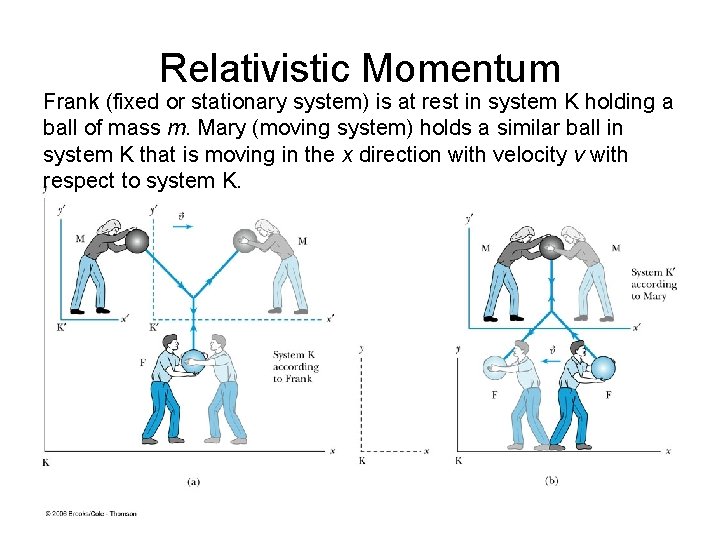

Relativistic Momentum Frank (fixed or stationary system) is at rest in system K holding a ball of mass m. Mary (moving system) holds a similar ball in system K that is moving in the x direction with velocity v with respect to system K.

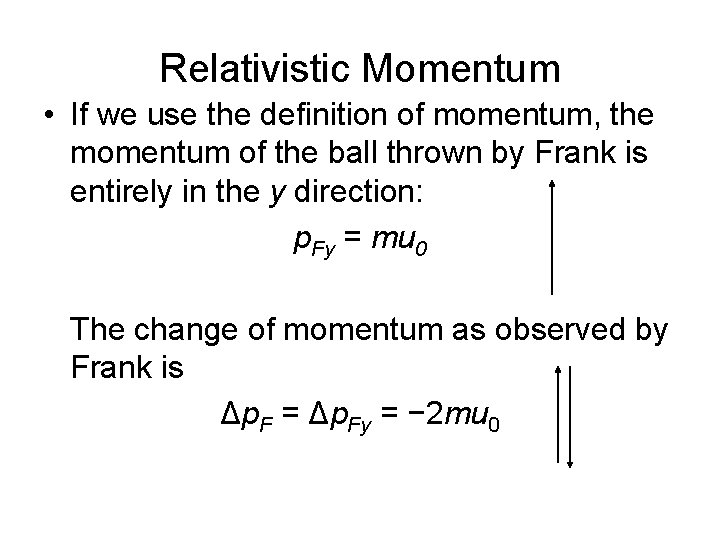

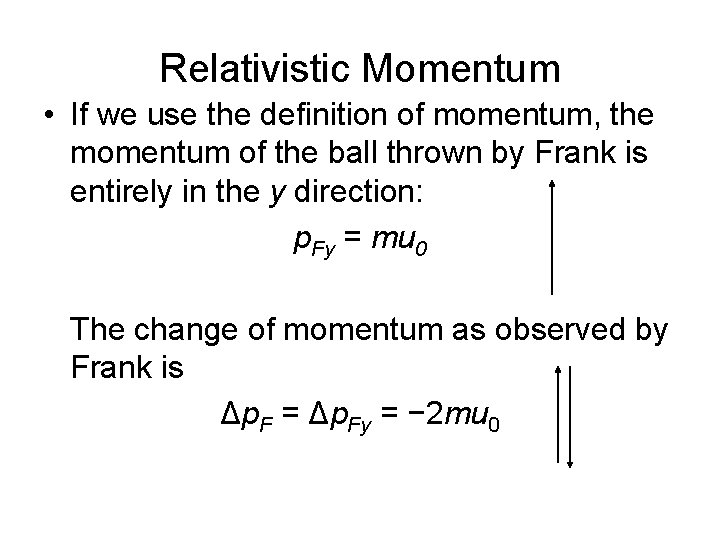

Relativistic Momentum • If we use the definition of momentum, the momentum of the ball thrown by Frank is entirely in the y direction: p. Fy = mu 0 The change of momentum as observed by Frank is Δp. F = Δp. Fy = − 2 mu 0

According to Mary • Mary measures the initial velocity of her own ball to be u’Mx = 0 and u’My = −u 0. K’ In order to determine the velocity of Mary’s ball as measured by Frank we use the velocity transformation equations: K

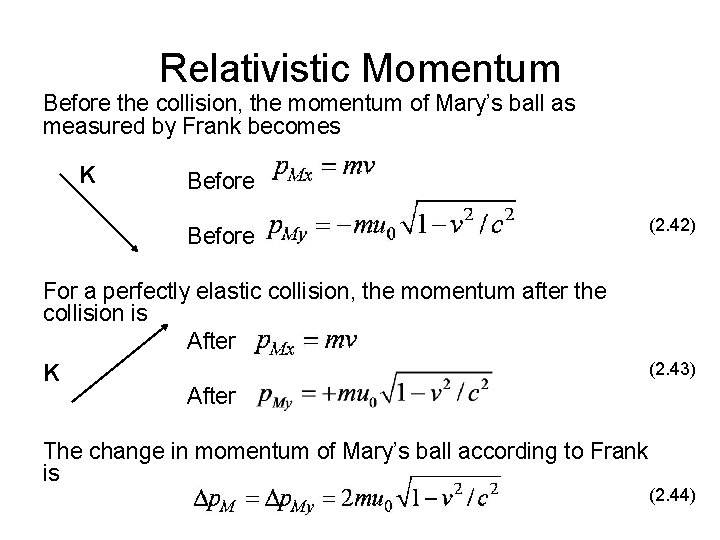

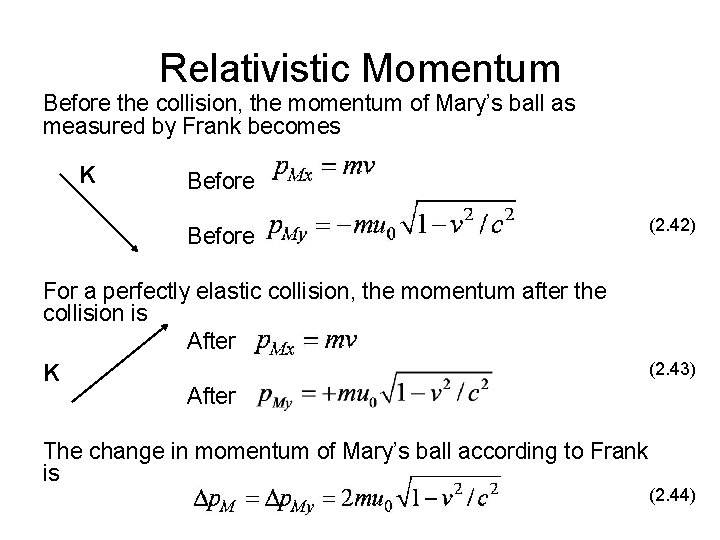

Relativistic Momentum Before the collision, the momentum of Mary’s ball as measured by Frank becomes K Before For a perfectly elastic collision, the momentum after the collision is After K After The change in momentum of Mary’s ball according to Frank is (2. 42) (2. 43) (2. 44)

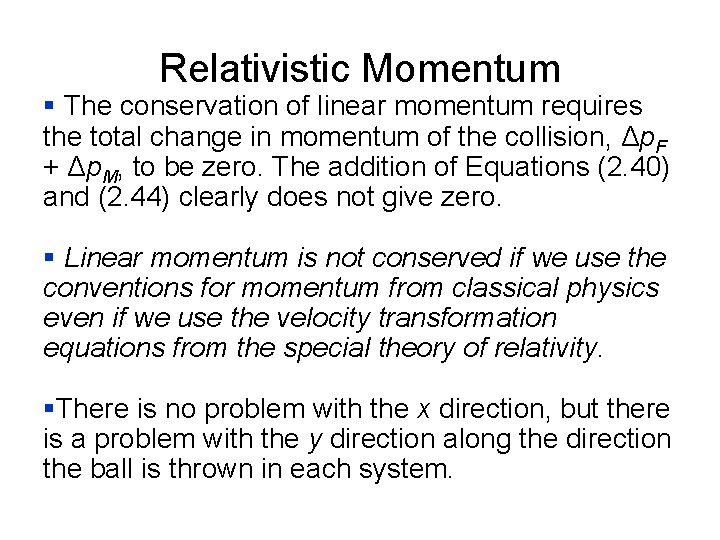

Relativistic Momentum § The conservation of linear momentum requires the total change in momentum of the collision, Δp. F + Δp. M, to be zero. The addition of Equations (2. 40) and (2. 44) clearly does not give zero. § Linear momentum is not conserved if we use the conventions for momentum from classical physics even if we use the velocity transformation equations from the special theory of relativity. §There is no problem with the x direction, but there is a problem with the y direction along the direction the ball is thrown in each system.

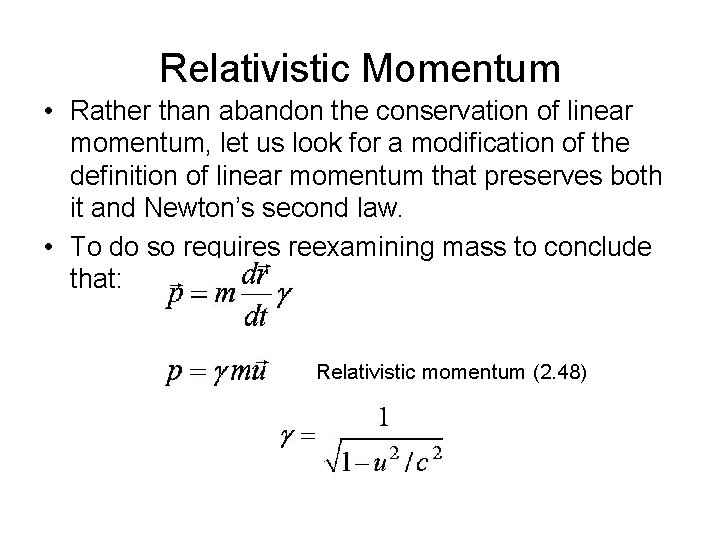

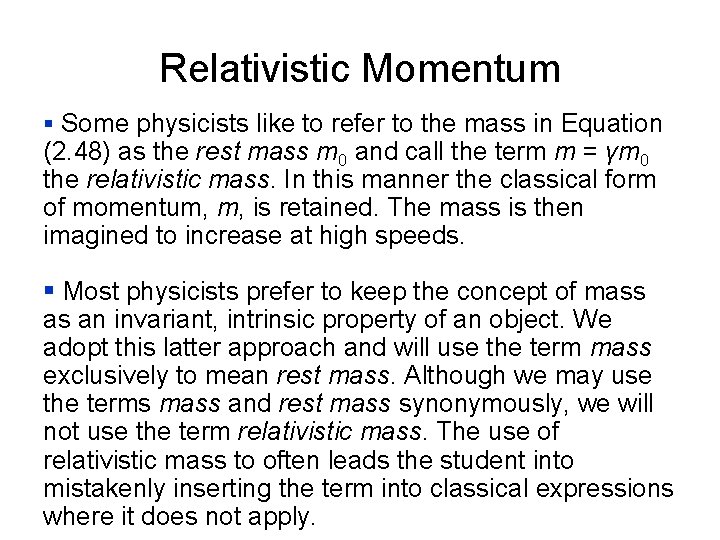

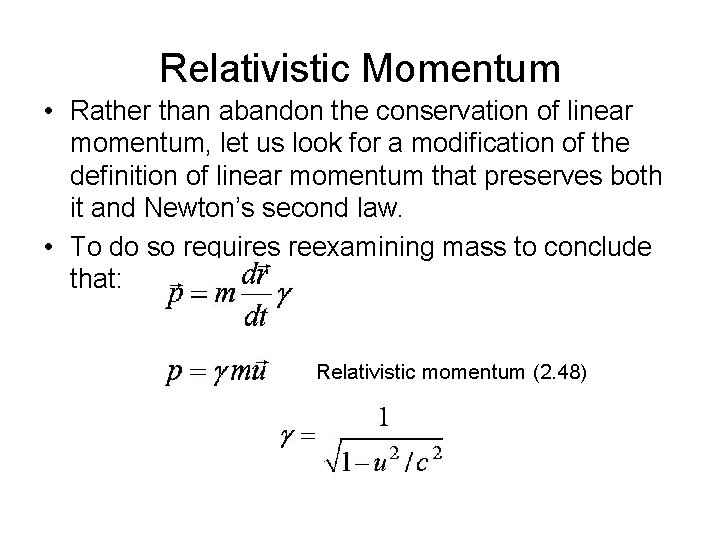

Relativistic Momentum • Rather than abandon the conservation of linear momentum, let us look for a modification of the definition of linear momentum that preserves both it and Newton’s second law. • To do so requires reexamining mass to conclude that: Relativistic momentum (2. 48)

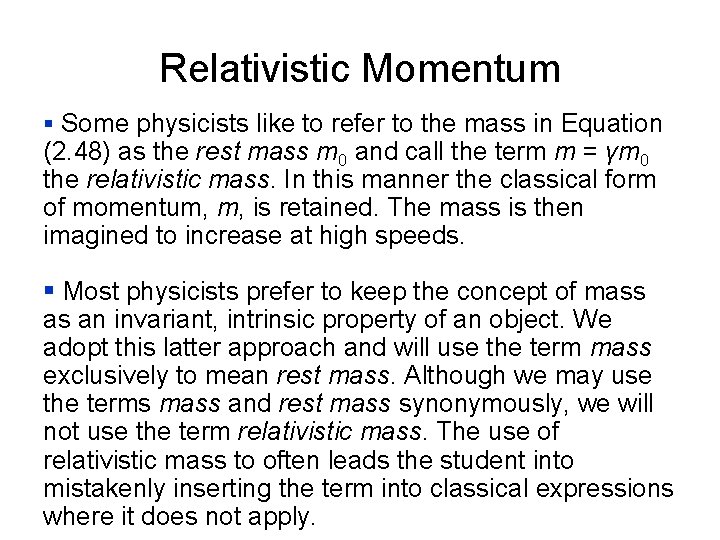

Relativistic Momentum § Some physicists like to refer to the mass in Equation (2. 48) as the rest mass m 0 and call the term m = γm 0 the relativistic mass. In this manner the classical form of momentum, m, is retained. The mass is then imagined to increase at high speeds. § Most physicists prefer to keep the concept of mass as an invariant, intrinsic property of an object. We adopt this latter approach and will use the term mass exclusively to mean rest mass. Although we may use the terms mass and rest mass synonymously, we will not use the term relativistic mass. The use of relativistic mass to often leads the student into mistakenly inserting the term into classical expressions where it does not apply.

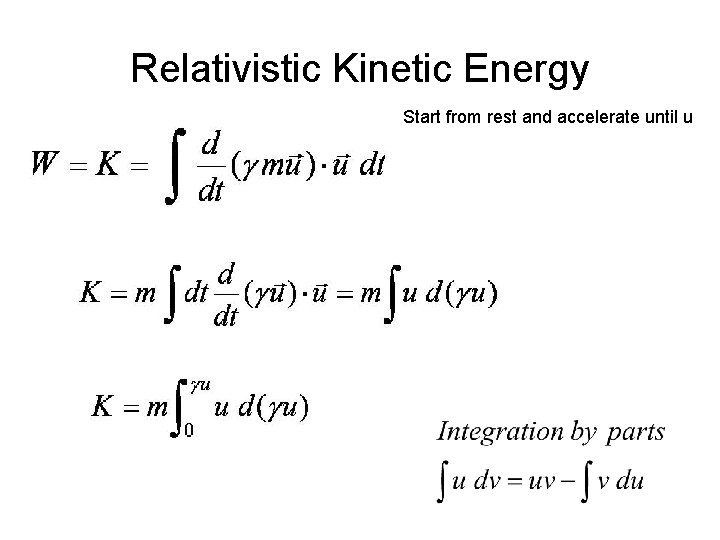

RELATIVISTIC KINETIC ENERGY The following 5 slides present Rex & Thorton’s treatment of kinetic energy in Special Relativity

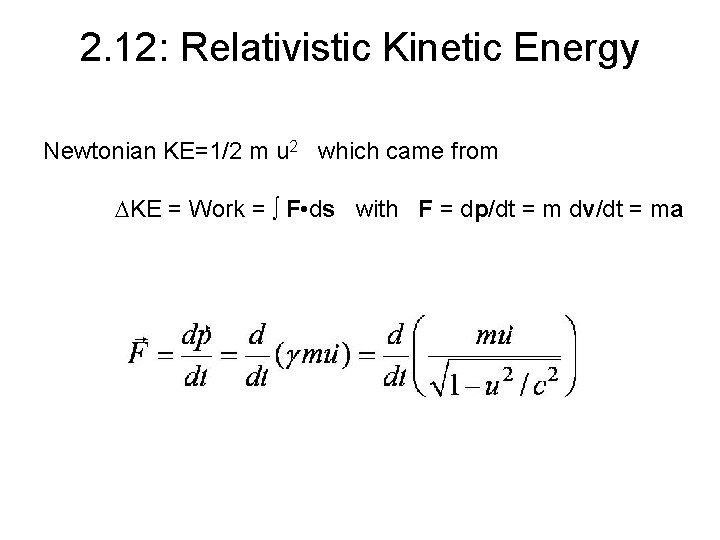

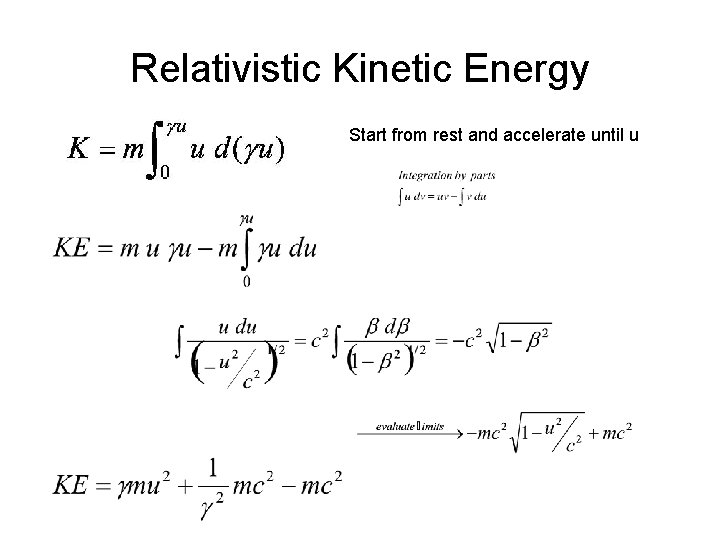

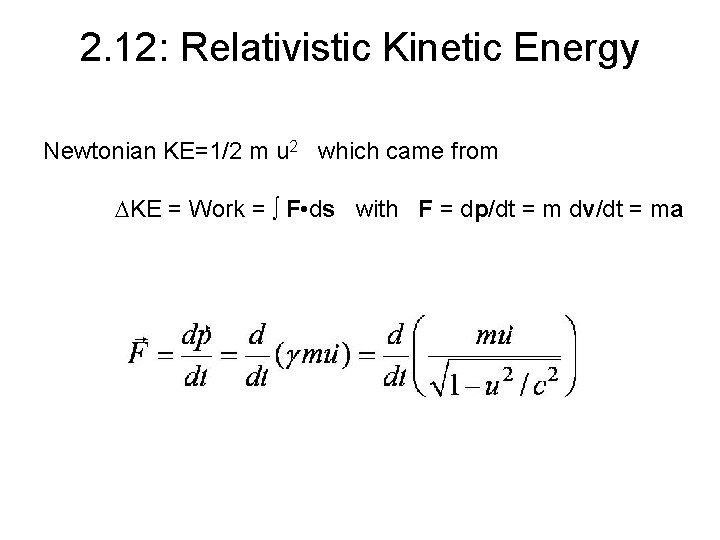

2. 12: Relativistic Kinetic Energy Newtonian KE=1/2 m u 2 which came from DKE = Work = ∫ F • ds with F = dp/dt = m dv/dt = ma

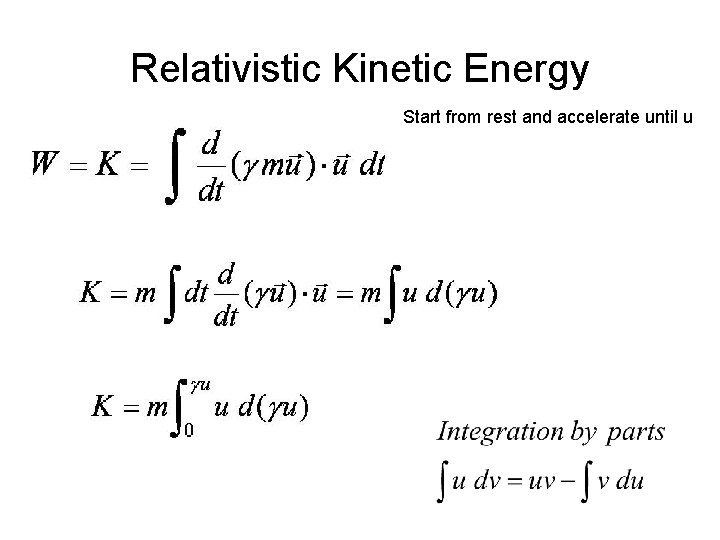

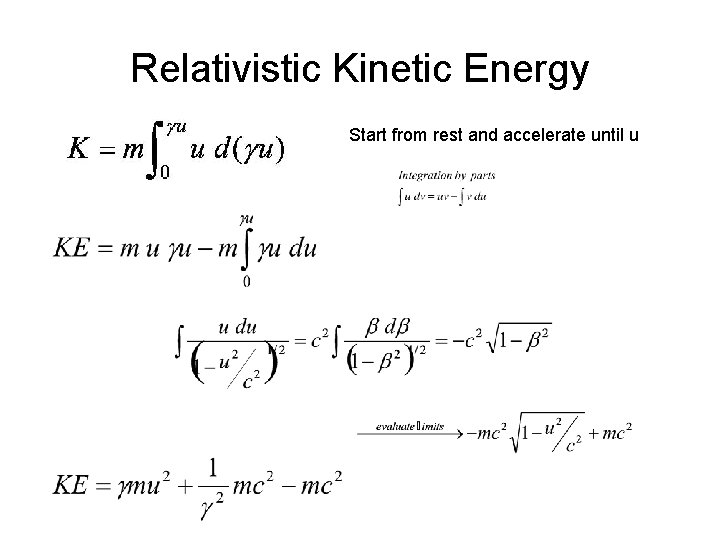

Relativistic Kinetic Energy Start from rest and accelerate until u

Relativistic Kinetic Energy Start from rest and accelerate until u

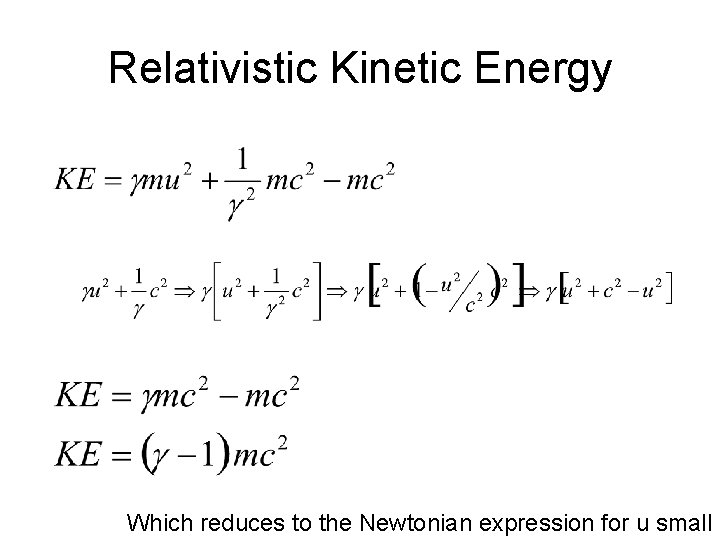

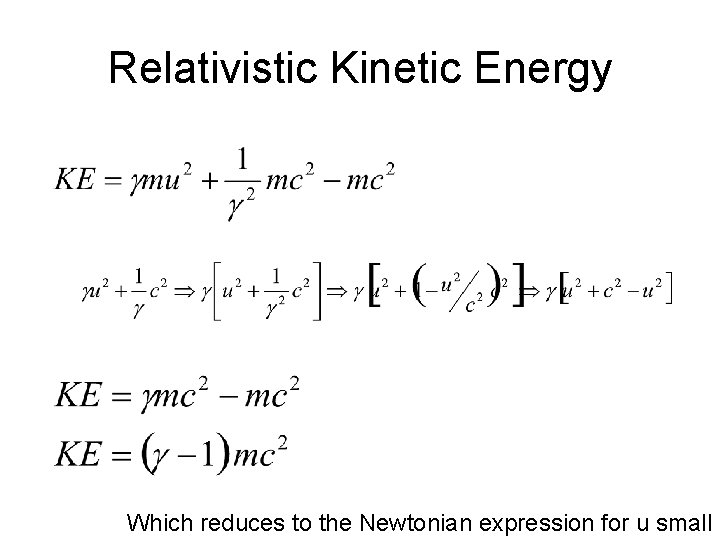

Relativistic Kinetic Energy Which reduces to the Newtonian expression for u small

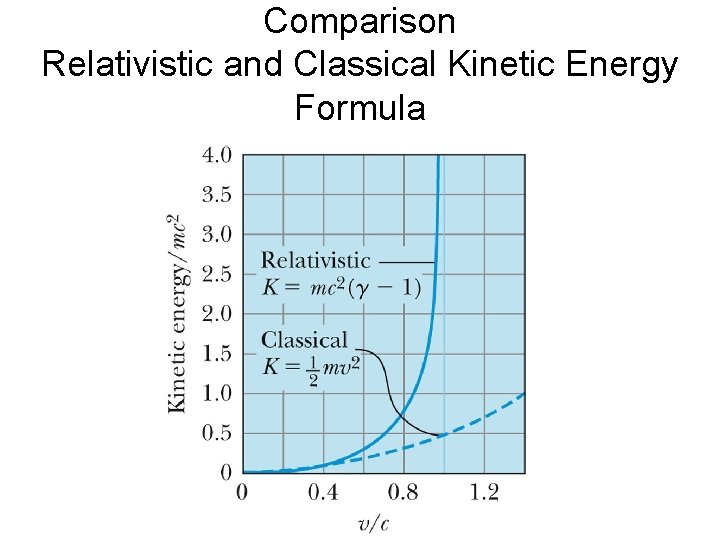

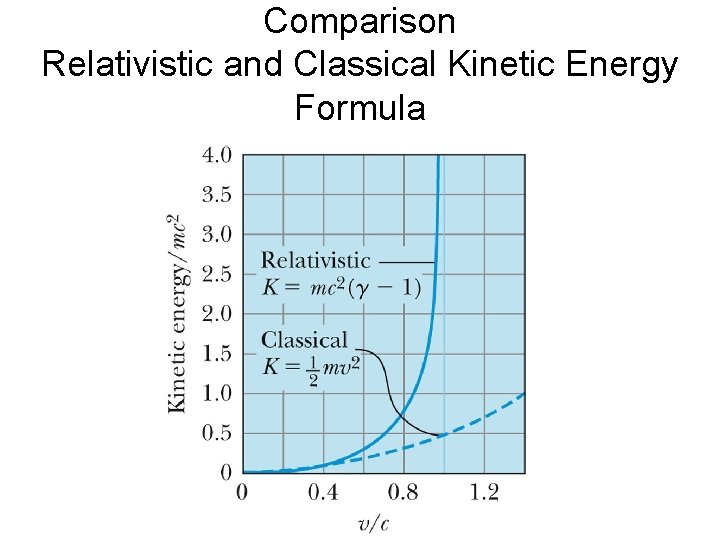

Comparison Relativistic and Classical Kinetic Energy Formula

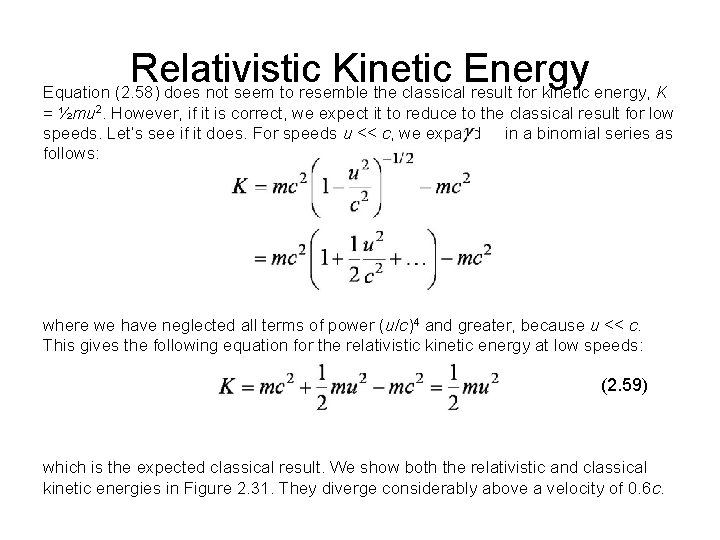

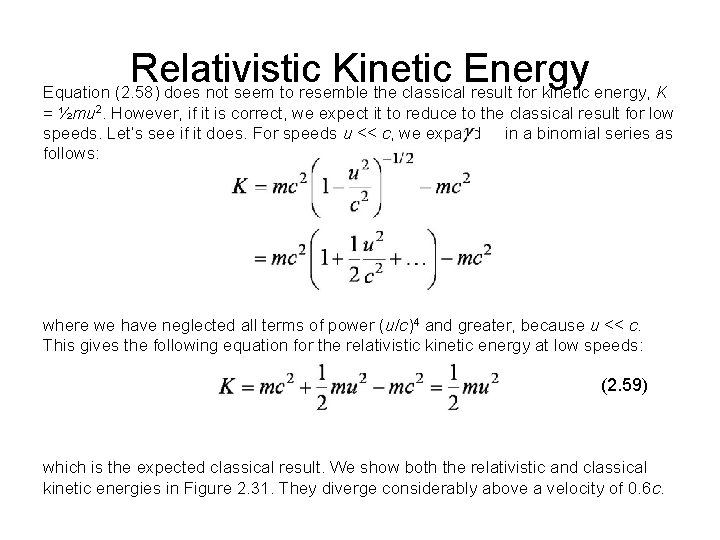

Relativistic Kinetic Energy Equation (2. 58) does not seem to resemble the classical result for kinetic energy, K = ½mu 2. However, if it is correct, we expect it to reduce to the classical result for low speeds. Let’s see if it does. For speeds u << c, we expand in a binomial series as follows: where we have neglected all terms of power (u/c)4 and greater, because u << c. This gives the following equation for the relativistic kinetic energy at low speeds: (2. 59) which is the expected classical result. We show both the relativistic and classical kinetic energies in Figure 2. 31. They diverge considerably above a velocity of 0. 6 c.

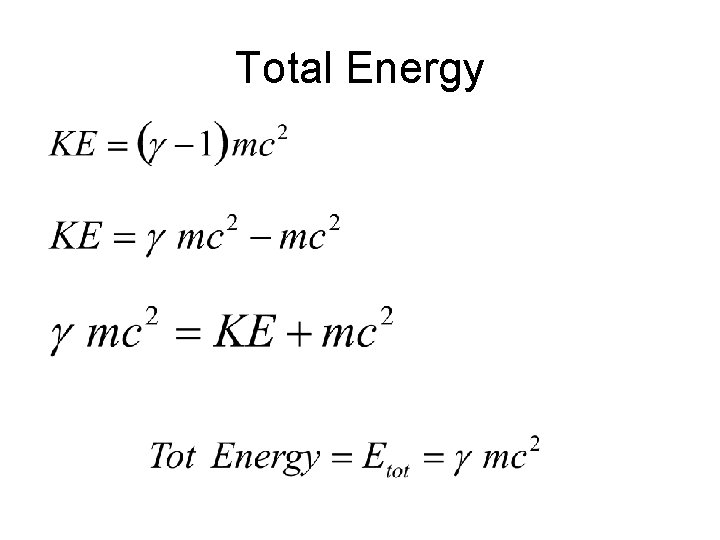

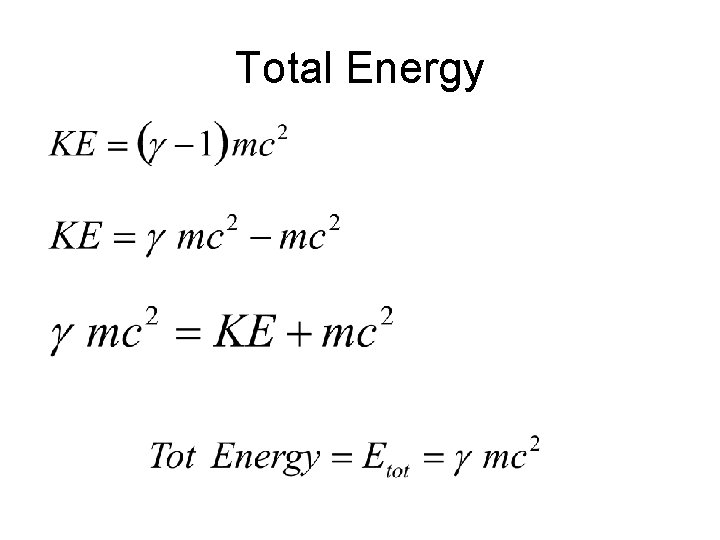

Total Energy

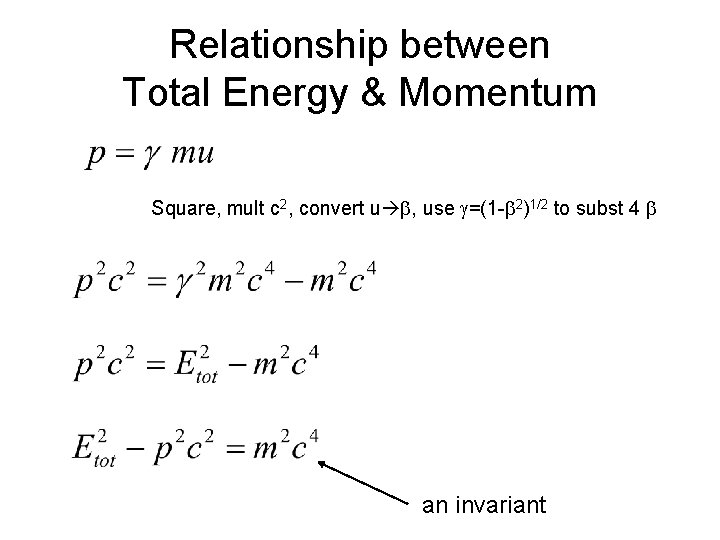

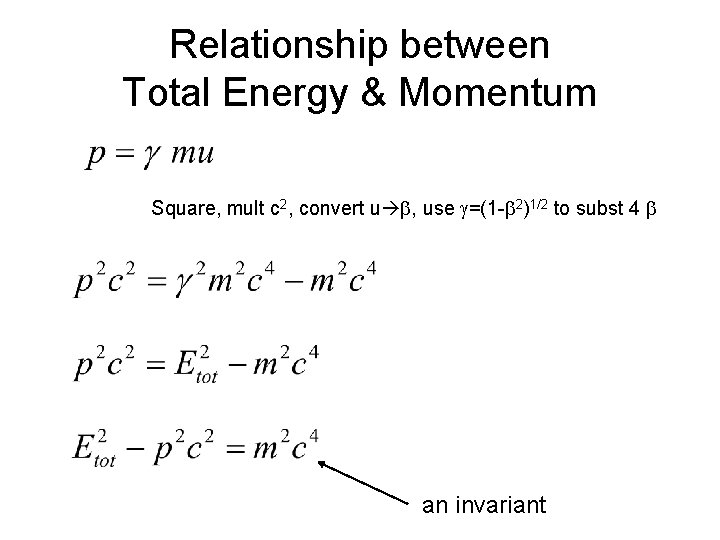

Relationship between Total Energy & Momentum Square, mult c 2, convert u b, use g=(1 -b 2)1/2 to subst 4 b an invariant

Youtube clips (part 3) • Galilean/Classical Relativity Part 3 – The Cassiopeia Project http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=W 6 o_-y. Ta 168 The Cassiopeia Project is an effort to make high quality science videos available to everyone. If you can visualize it, then understanding is not far behind. http: //www. cassiopeiaproject. com/ To read more about the Theory of Special Relativity, you can start here: http: //www. phys. unsw. edu. au/einsteinlight/ http: //www. einstein-online. info/en/elementary/index. html http: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/Special_relativity

Examples

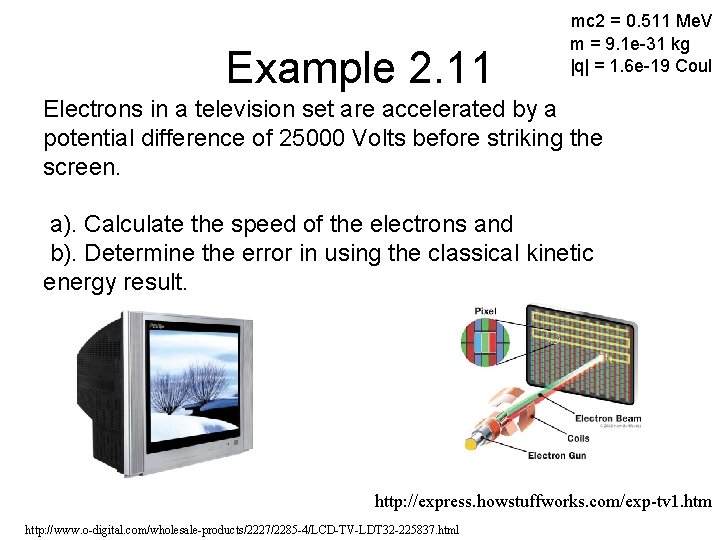

Example 2. 11 mc 2 = 0. 511 Me. V m = 9. 1 e-31 kg |q| = 1. 6 e-19 Coul Electrons in a television set are accelerated by a potential difference of 25000 Volts before striking the screen. a). Calculate the speed of the electrons and b). Determine the error in using the classical kinetic energy result. http: //express. howstuffworks. com/exp-tv 1. htm http: //www. o-digital. com/wholesale-products/2227/2285 -4/LCD-TV-LDT 32 -225837. html

Example 2. 13 A 2 -Ge. V proton hits another 2 -Ge. V proton in a head-on collision in order to create top quarks. http: //www. fnal. gov • For each of the initial protons, calculate – Speed v – b – Momentum p – Rest-mass Energy – Kinetic Energy KE – Total Energy Etot mc 2=938 Me. V

Example 2. 16 The helium nucleus is built from 2 protons and 2 neutrons. The binding energy is the difference in rest mass-energy of the nucleus from the total rest mass-energy of it’s component parts. Calculate the nuclear binding energy of helium. m. He = 4. 002603 amu mp = 1. 007825 amu mn = 1. 008665 amu Hints: 1 amu = 1. 67 e-27 kg or c 2 = 931. 5 Me. V/amu http: //www. dbxsoftware. com/helium/

Example 2. 17 The molecular binding energy is called dissociation energy. It is the energy required to separate the atoms in a molecule. The dissociation energy of the Na. Cl molecule is 4. 24 e. V. Determine the fractional mass increase of the Na and Cl atoms when they are not bound together in Na. Cl. m. Na = 22. 98976928 amu Average m. Cl = 35. 453 amu http: //www. ionizers. org/water. html Hints: 1 amu = 1. 67 e-27 kg or c 2 = 931. 5 Me. V/amu

Sandin 5. 30 A spaceship has a length of 100 m and a mass of 4 e+9 kg as measured by the crew. When it passes us, we measure the spaceship to be 75 m long. What do we measure its momentum to be?

RHIC The diameter of an gold nucleus is 14 fm. If a Au nucleus has a kinetic energy of 4000 Ge. V, what is the apparent ‘thickness’ of the nucleus in the laboratory? Length contraction mc 2=197*931. 5 Me. V http: //www. bnl. gov/rhic/

Sandin 5. 22 At the Stanford Linear Accelerator, 50 Ge. V electrons are produced • For one of these electrons, calculate – Speed v – b – Momentum p – Rest-mass Energy – Kinetic Energy KE – Total Energy Etot http: //www. flickr. com/photos/kqedquest/3268446670/ http: //www. daviddarling. info/encyclopedia/L/linear_accelerator. html mc 2 = 0. 511 Me. V

Sandin 5. 25 A cosmic ray pion (rest mass 140 Me. V/c 2) has a momentum of 100 Me. V/c. http: //www. mpi-hd. mpg. de/hfm/Cosmic. Ray/Showers. html • Calculate – Speed v – b – Momentum p – Rest-mass Energy – Kinetic Energy KE – Total Energy Etot http: //www 2. slac. stanford. edu/vvc/cosmicrays/cratmos. html

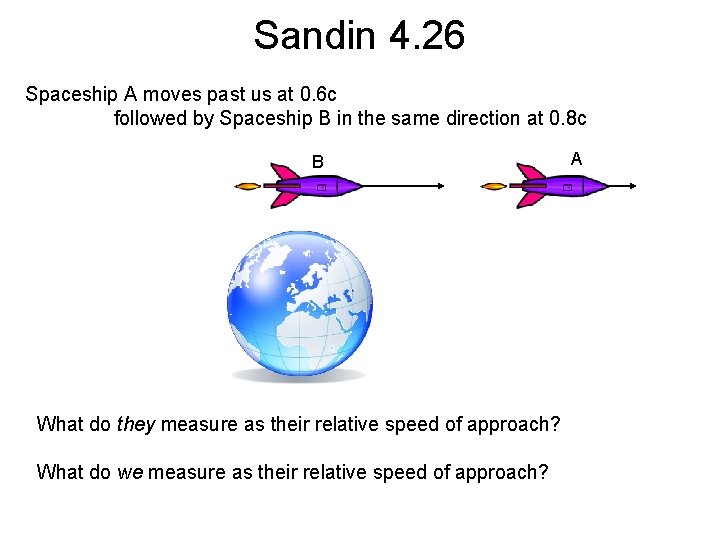

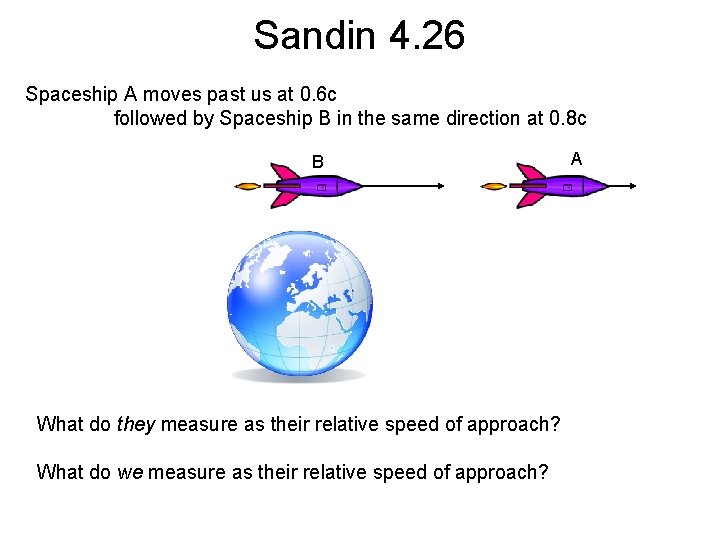

Sandin 4. 26 Spaceship A moves past us at 0. 6 c followed by Spaceship B in the same direction at 0. 8 c B What do they measure as their relative speed of approach? What do we measure as their relative speed of approach? A

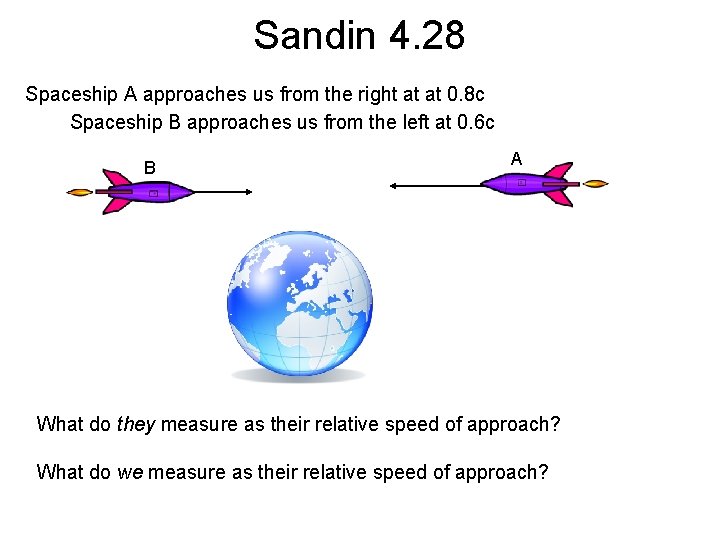

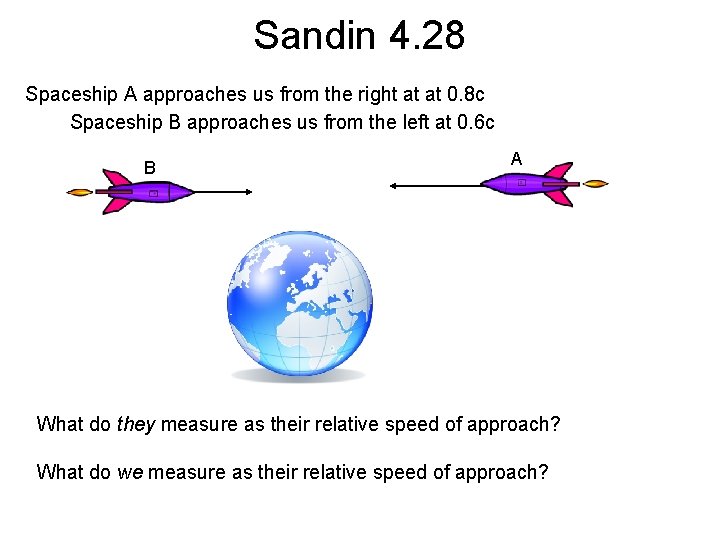

Sandin 4. 28 Spaceship A approaches us from the right at at 0. 8 c Spaceship B approaches us from the left at 0. 6 c B A What do they measure as their relative speed of approach? What do we measure as their relative speed of approach?