Chapt 21 The Species Concept Species and Their

- Slides: 15

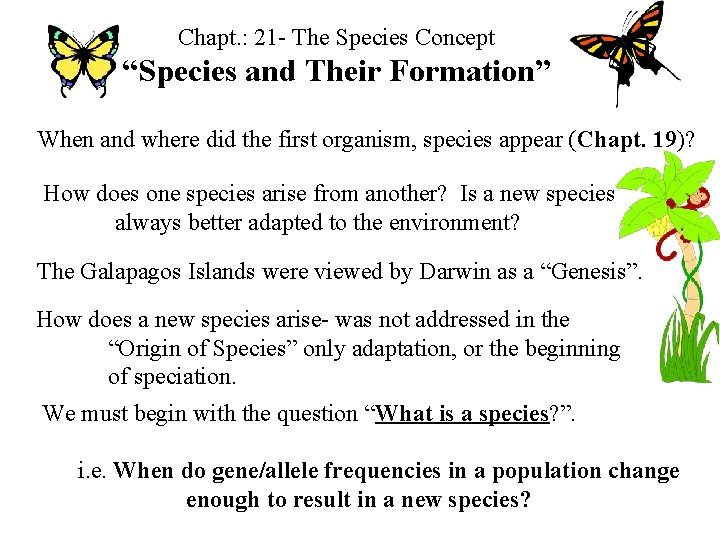

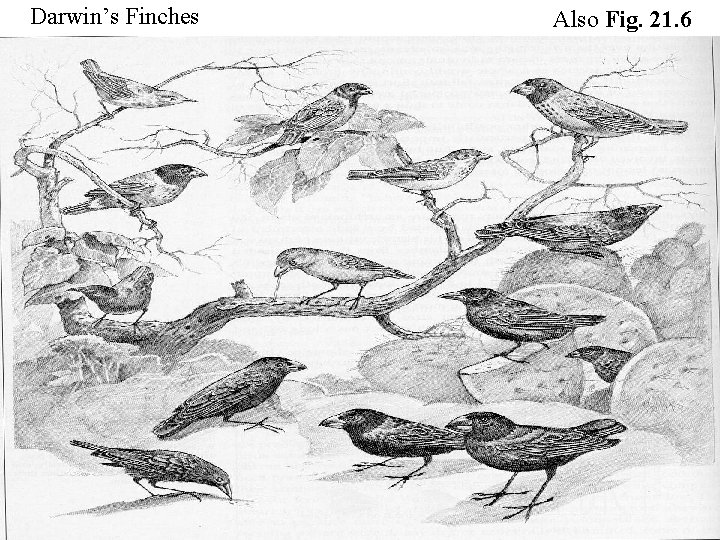

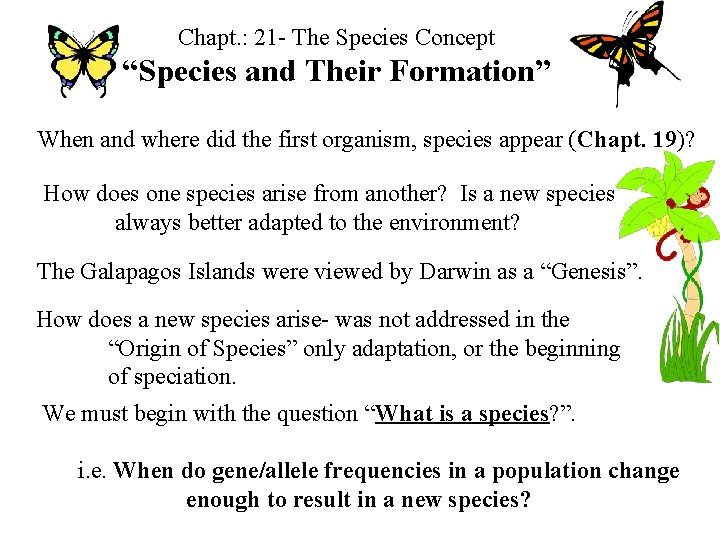

Chapt. : 21 - The Species Concept “Species and Their Formation” When and where did the first organism, species appear (Chapt. 19)? How does one species arise from another? Is a new species always better adapted to the environment? The Galapagos Islands were viewed by Darwin as a “Genesis”. How does a new species arise- was not addressed in the “Origin of Species” only adaptation, or the beginning of speciation. We must begin with the question “What is a species? ”. i. e. When do gene/allele frequencies in a population change enough to result in a new species?

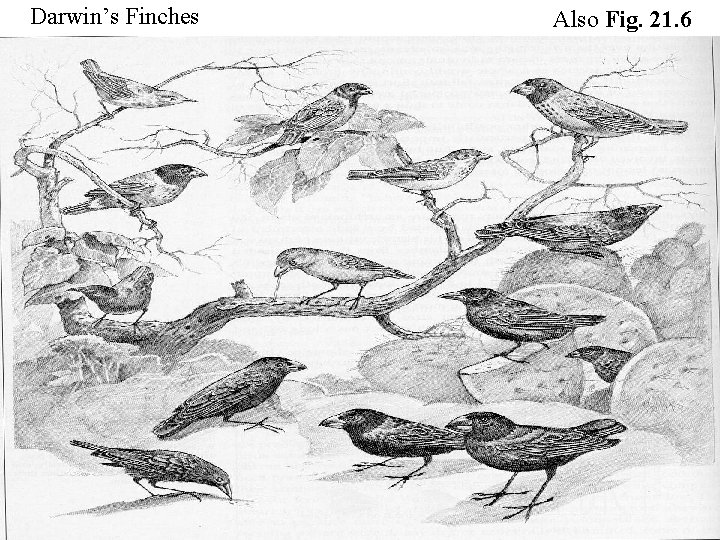

Darwin’s Finches Also Fig. 21. 6

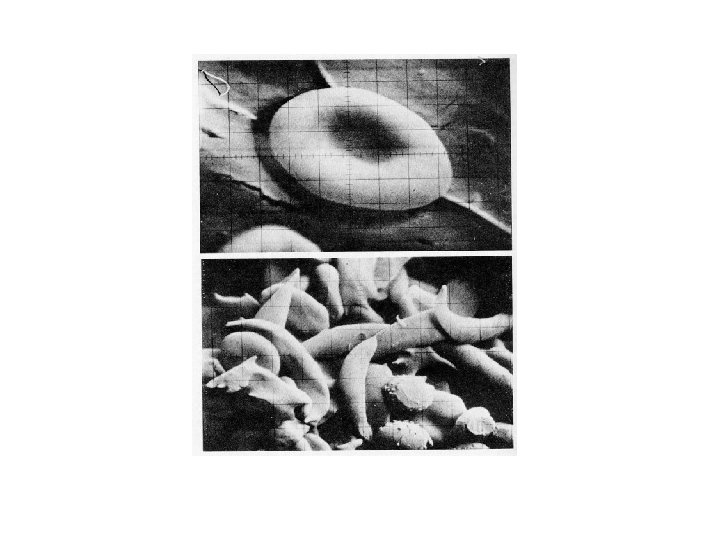

Can a mutation create a new species ‘overnight’? ?

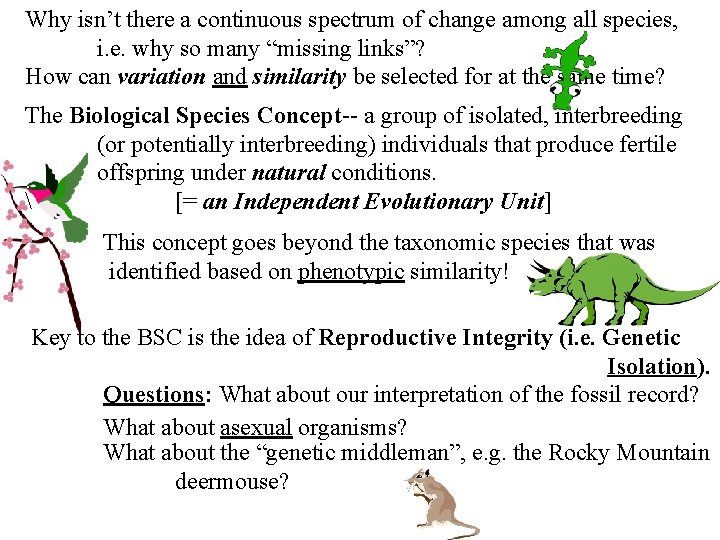

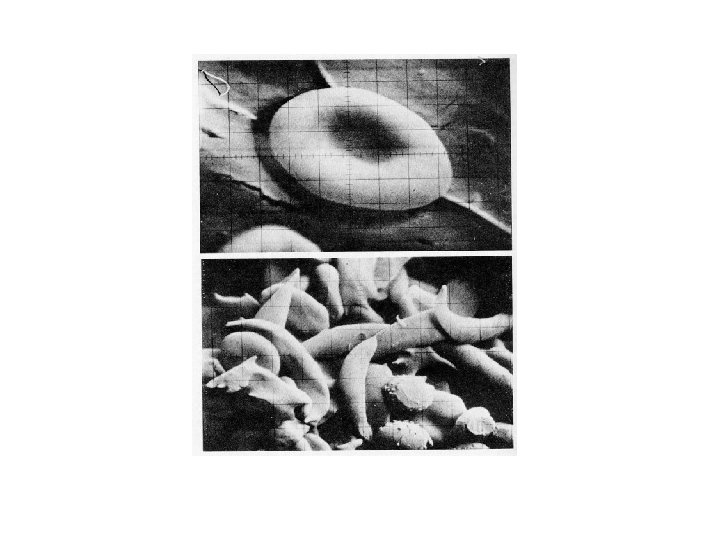

Why isn’t there a continuous spectrum of change among all species, i. e. why so many “missing links”? How can variation and similarity be selected for at the same time? The Biological Species Concept-- a group of isolated, interbreeding (or potentially interbreeding) individuals that produce fertile offspring under natural conditions. [= an Independent Evolutionary Unit] This concept goes beyond the taxonomic species that was identified based on phenotypic similarity! Key to the BSC is the idea of Reproductive Integrity (i. e. Genetic Isolation). Questions: What about our interpretation of the fossil record? What about asexual organisms? What about the “genetic middleman”, e. g. the Rocky Mountain deermouse?

Critical Step in Speciation-- splinter population becomes isolated!! What kind of isolation? Three types of genetic isolation can occur: (1) Allopatric Speciation-- geographic, mechanical barrier develops. (Fig. 21. 4) (2) Sympatric Speciation-- reproductive isolation without spatial or physical separation (one individual, or many individuals become isolated inside the parent population) Genetic mechanisms!! (3) Parapatric Speciation– weak isolation over small distances, (steep environmental change) often with gene flow What conditions favor allopatric speciation? [Hint: the same that favor microevolution: population size, gene pool, natural selection, and Chance!!] Why are islands so ripe for Allop. & Symp speciation?

A “model” for allopatric speciation within an island system: Isolation + Rare Dispersal (e. g. Founders) + Competition = Adaptive Radiation + Allopatric Speciation E. g. “Island Hopping” and availability of new ‘niches’ minimizes competition (Fig. 21. 5, Hawaiian Drosophila). e. g. Hawaiian Islands vs. Florida Keys! Why? ? (Size-Mobility-Dispersal = Isolation Potential) = Endemics! (Continental Drift? ) Sympatric Speciation--spatial separation not needed, only reproductive isolation via genetic mistakes or microhabitat selection. Polyploidy: extra sets of chromosomes. How? ? (Pg. 211, Chapt. 9). Non-disjunction!! Causes autopolyploidy (4 n, 8 n, etc. ) Allopolyploidy = hybrids of different species, sterile Can result in viable and fertile offspring! 25 to 50% of all plant species. Why plants? !!

Plants = self-fertilzation, or crosses with others of same ploidy level, e. g. siblings (autopolyploid) = crosses between different species result in improper pairing of homologous chromosomes during meiosis and sterility (allopolyploid). But, asexual reproduction occurs and, ultimately, the return of fertility (chromosome duplication). e. g. Tragopogon species (sunflower family) = two introduced diploids in 1950, now two tetraploid hybrids by 1985!! (Fig. 21. 2) Polyploid hybrids often more fit than parent species. Why? Also, there have been multiple origins of the tetraploid hybrids. (Molecular comparisons of chloroplast and ribosomal genomes) Sympatric speciation by polyploidy rare in animals (Why? ) More often occurs by microhabitat selection and reproductive isolation. Parapatric speciation- more difficult to document until molecular data became available, e. g. flowering times change on polluted soils

Remember-- Why is it important to have so many different species? Diversity among species is just as important as diversity among individuals of a population, i. e. interspecific vs. intraspecific diversity both critically important!! WHY? ? Morphological changes with little change genetically are common. (Fig. 21. 12) How are different species maintained as separate species (reproductive isolation)? -Reproductive Barriers (Isolating Mechanisms): (1) Prezygotice. g. Habitat, behavioral, temporal, mechanical, (see Fig. 21. 6) gametic (post-mating) (2) Postzygotice. g. Hybrid zygote abnormal, offspring infertility and low survival (see Fig. 21. 9 for summary)

Rates of Speciation: How fast can a new species form from an ancestor? Horseshoe crab unchanged for 200 million yrs Hawaiian Drosophila - hundreds of different species in 40 mil yrs - Species richness -Life history traits (size/mobility/mating) ( see Figs. 21. 13 and 21. 14) -Environment (heterogeneous) -Generation times (short) = Speciation Potential Evolutionary Radiation = low extinction and high speciation rates (Fig 21. 16, “gaping” muscles) Speciation = Evolution = Punctuated Eqiulibrium WHY IS BIODIVERSITY IMPORTANT? ? SUSTAINABLE ECOSYSTEMS? ? e. g. National Parks? ?