Channel bias in artificial language learning of wordfinal

Channel bias in artificial language learning of word-final obstruent voicing Juian Kirkeby Lysvik j. k. lysvik@uio. iln. no University of Oslo Supervisors: Pritty Patel-Grosz and Andrew Nevins

Roadmap Investigating the markedness of word-final obstruent voicing using an artificial language learning experiment • • • Brief overview Typological and phonetic markedness of final voicing Background theory ALL research Current experiment – Results – Analysis – Conclusion • Future work 3

Overview • The process of word-final obstruent devoicing is a common process. No language has the reverse process of word-final voicing – /bɛdən/ [bɛt] ‘beds bed’ (Dutch) – */bɛtən/ [bɛd] • Tested using artificial language learning • Both types learned in forced-choice task • Difference in production – Devoicing: [bɛdən] ↔ [bɛt] – Voicing: [bɛdən] ↔ [bɛd] (should be [bɛtən] ↔ [bɛd] ) • Caused by a channel (production bias) against voiceless intervocalic segments Overview 4

![Typology Language Underlying Meaning Devoicing Meaning German /bɛːder/ Bäder ‘bath (pl. )’ [baːt] Bad Typology Language Underlying Meaning Devoicing Meaning German /bɛːder/ Bäder ‘bath (pl. )’ [baːt] Bad](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/9320c0e5f6152c8ac5398830470e328c/image-4.jpg)

Typology Language Underlying Meaning Devoicing Meaning German /bɛːder/ Bäder ‘bath (pl. )’ [baːt] Bad ‘bath’ Catalan /freda/ freda ‘cold (f. )’ [fret] fred ‘cold (m. )’ Russian /kniga/ Книгa ‘book (nom. sg. )’ [knik] Книг ‘book (gen. pl. )’ Turkish /kaba/ kaba ‘container (dat. )’ [kap] kab ‘container (nom. )’ Maltese /laːbi/ lagħabi ‘playful’ [lɐːp] lagħab ‘he played’ The pattern is cross-linguistically common and found in several different language families and different syntactic and morphological conditions Markedness 5

Some languages are claimed to have word-final obstruent voicing (Blevins 2004) Somali – Welsh – Tundra Nenets – Lezgian Cushitic – Celtic – Samoyedic – Caucasian But all of these are disputed in the literature (Kiparsky 2006) Markedness 6

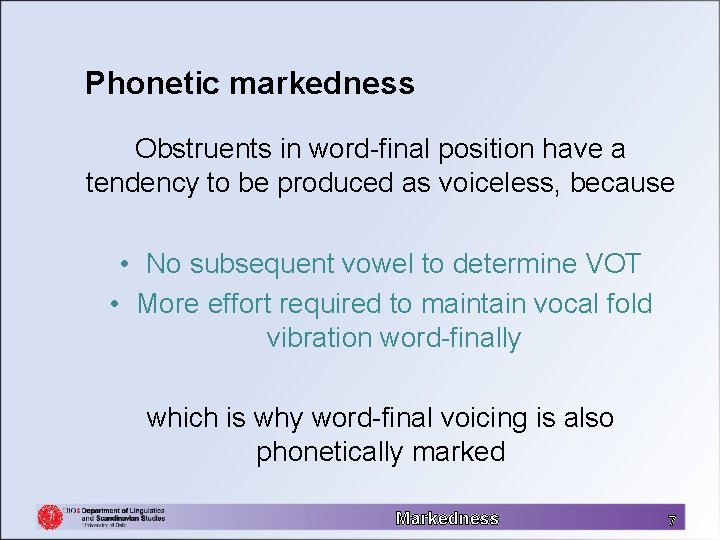

Phonetic markedness Obstruents in word-final position have a tendency to be produced as voiceless, because • No subsequent vowel to determine VOT • More effort required to maintain vocal fold vibration word-finally which is why word-final voicing is also phonetically marked Markedness 7

How is this relevant to phonology? Different approaches to phonology make different predictions as to what causes this typological markedness Looking at • Grounded phonology • Substance-free phonology Background Theory 8

![Phonetically Grounded Phonology ‘phonological constraints can be rooted in phonetic knowledge […], the speakers’ Phonetically Grounded Phonology ‘phonological constraints can be rooted in phonetic knowledge […], the speakers’](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/9320c0e5f6152c8ac5398830470e328c/image-8.jpg)

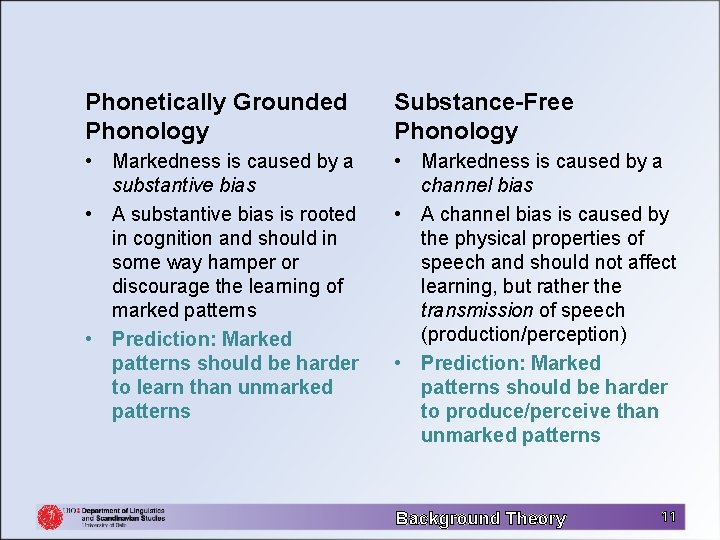

Phonetically Grounded Phonology ‘phonological constraints can be rooted in phonetic knowledge […], the speakers’ partial understanding of the physical conditions under which speech is produced and perceived. ’ (Hayes et al. , 2004: 1) Physical properties of speech are encoded into phonological cognition, and limits which patterns are acquired. The bias against marked properties is called a substantive bias. • Precursor in SPE (Chomsky & Halle, 1968) • Grounded Phonology (Archangeli & Pulleyblank, 1994) • Optimality Theory (Prince & Smolensky, 1993) Physical constraints become cognitive constraints Background Theory 9

![Substance-Free Phonology ‘[…]many of the so-called phonological universals (often discussed under the rubric of Substance-Free Phonology ‘[…]many of the so-called phonological universals (often discussed under the rubric of](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/9320c0e5f6152c8ac5398830470e328c/image-9.jpg)

Substance-Free Phonology ‘[…]many of the so-called phonological universals (often discussed under the rubric of markedness) are in fact epiphenomena deriving from the interaction of extragrammatical factors like acoustic salience and the nature of language change. ’ (Hale & Reiss, 2000 b) Physical properties of speech are extra-linguistic, and not encoded in phonological cognition. The bias against marked properties is caused by the physical properties themselves and is called a channel bias. • Evolutionary Phonology (Blevins, 2004) • Element Theory (Harris, 1990) Physical constraints do not become cognitive constraints Background Theory 10

Phonetically Grounded Phonology Substance-Free Phonology • Markedness is caused by a substantive bias • A substantive bias is rooted in cognition and should in some way hamper or discourage the learning of marked patterns • Prediction: Marked patterns should be harder to learn than unmarked patterns • Markedness is caused by a channel bias • A channel bias is caused by the physical properties of speech and should not affect learning, but rather the transmission of speech (production/perception) • Prediction: Marked patterns should be harder to produce/perceive than unmarked patterns Background Theory 11

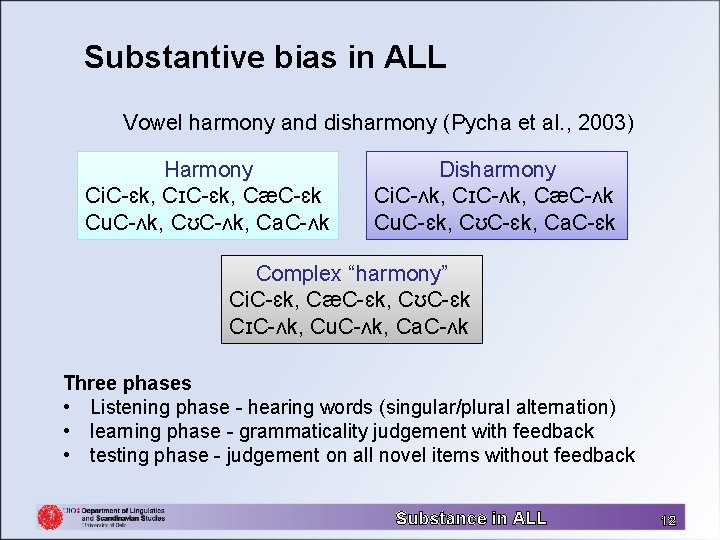

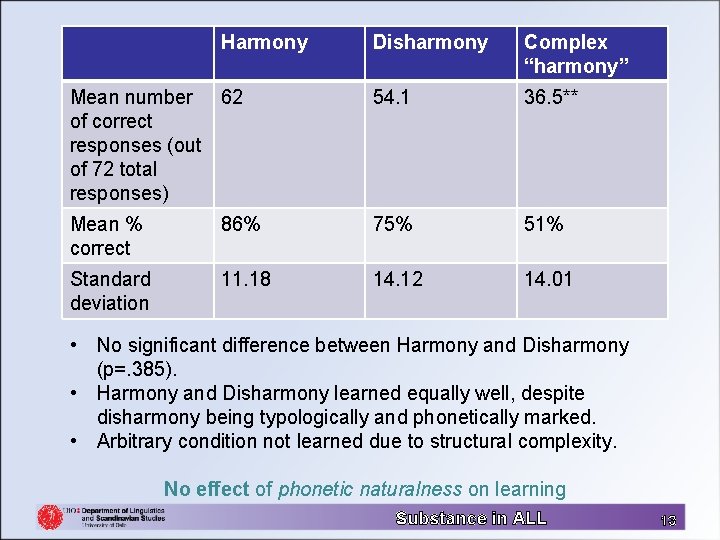

Substantive bias in ALL Vowel harmony and disharmony (Pycha et al. , 2003) Harmony Ci. C-ɛk, CɪC-ɛk, CæC-ɛk Cu. C-ʌk, CʊC-ʌk, Ca. C-ʌk Disharmony Ci. C-ʌk, CɪC-ʌk, CæC-ʌk Cu. C-ɛk, CʊC-ɛk, Ca. C-ɛk Complex “harmony” Ci. C-ɛk, CæC-ɛk, CʊC-ɛk CɪC-ʌk, Cu. C-ʌk, Ca. C-ʌk Three phases • Listening phase - hearing words (singular/plural alternation) • learning phase - grammaticality judgement with feedback • testing phase - judgement on all novel items without feedback Substance in ALL 12

Harmony Disharmony Complex “harmony” Mean number 62 of correct responses (out of 72 total responses) 54. 1 36. 5** Mean % correct 86% 75% 51% Standard deviation 11. 18 14. 12 14. 01 • No significant difference between Harmony and Disharmony (p=. 385). • Harmony and Disharmony learned equally well, despite disharmony being typologically and phonetically marked. • Arbitrary condition not learned due to structural complexity. No effect of phonetic naturalness on learning Substance in ALL 13

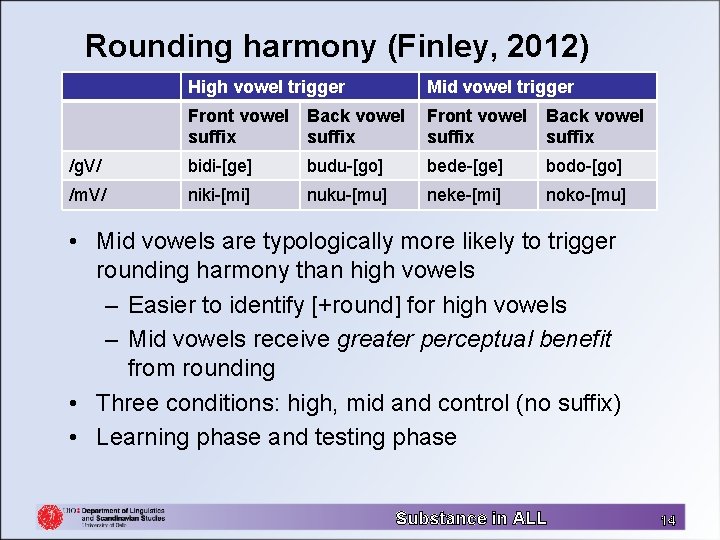

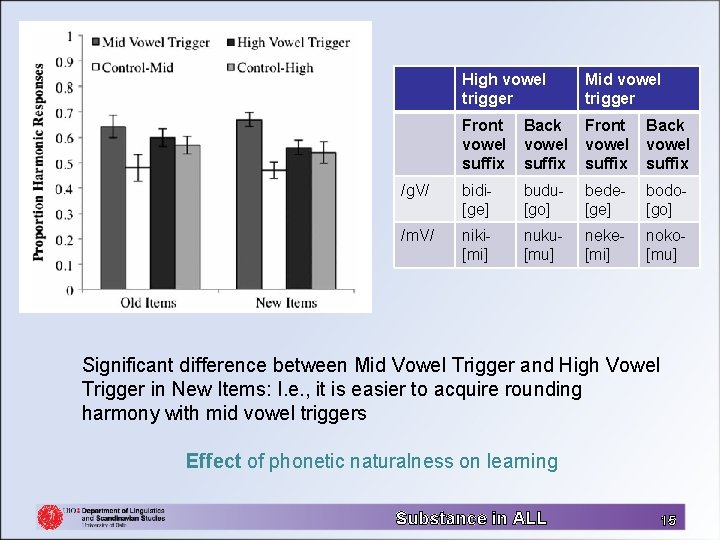

Rounding harmony (Finley, 2012) High vowel trigger Mid vowel trigger Front vowel suffix Back vowel suffix /g. V/ bidi-[ge] budu-[go] bede-[ge] bodo-[go] /m. V/ niki-[mi] nuku-[mu] neke-[mi] noko-[mu] • Mid vowels are typologically more likely to trigger rounding harmony than high vowels – Easier to identify [+round] for high vowels – Mid vowels receive greater perceptual benefit from rounding • Three conditions: high, mid and control (no suffix) • Learning phase and testing phase Substance in ALL 14

High vowel trigger Mid vowel trigger Front vowel suffix Back vowel suffix /g. V/ bidi[ge] budu[go] bede[ge] bodo[go] /m. V/ niki[mi] nuku[mu] neke[mi] noko[mu] Significant difference between Mid Vowel Trigger and High Vowel Trigger in New Items: I. e. , it is easier to acquire rounding harmony with mid vowel triggers Effect of phonetic naturalness on learning Substance in ALL 15

![Final Obstruent Voicing vs. Final Obstruent Devoicing [-son] [+voice]/__## vs. [-son] [-voice]/__## • Structurally Final Obstruent Voicing vs. Final Obstruent Devoicing [-son] [+voice]/__## vs. [-son] [-voice]/__## • Structurally](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/9320c0e5f6152c8ac5398830470e328c/image-15.jpg)

Final Obstruent Voicing vs. Final Obstruent Devoicing [-son] [+voice]/__## vs. [-son] [-voice]/__## • Structurally equally complex – Structurally complex rules are harder to learn (remember Pycha et al. , 2003) – Refer to the same features • Only different in terms of naturalness – Typological – Phonetic Final voicing vs. Final devoicing 16

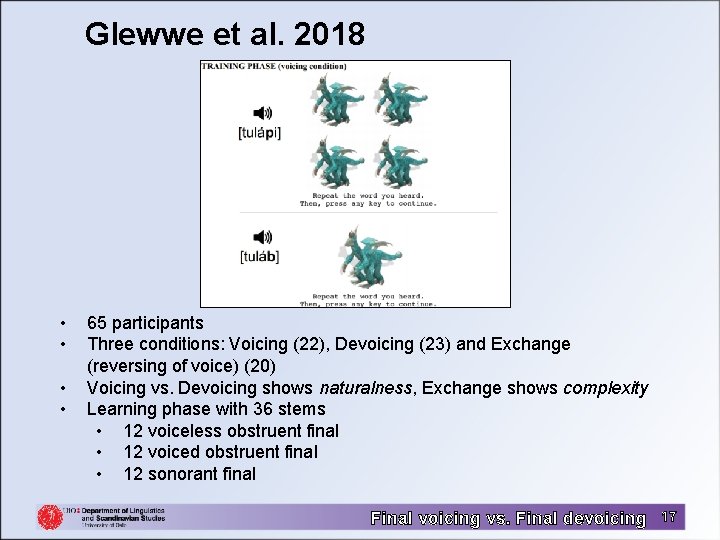

Glewwe et al. 2018 • • 65 participants Three conditions: Voicing (22), Devoicing (23) and Exchange (reversing of voice) (20) Voicing vs. Devoicing shows naturalness, Exchange shows complexity Learning phase with 36 stems • 12 voiceless obstruent final • 12 voiced obstruent final • 12 sonorant final Final voicing vs. Final devoicing 17

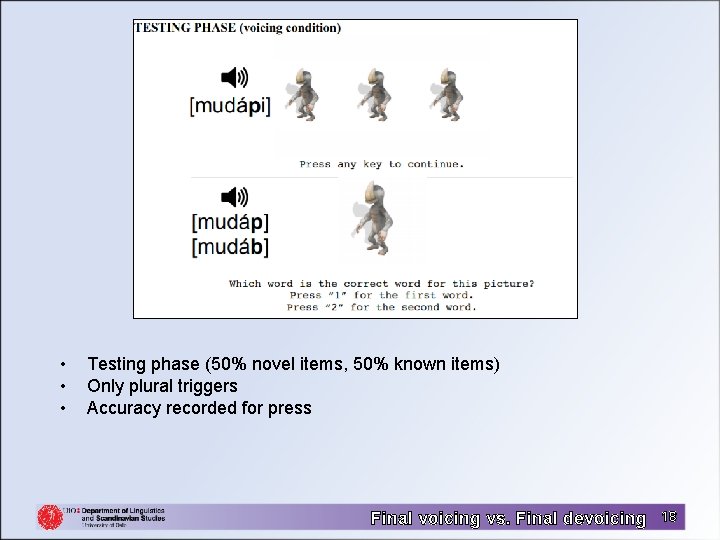

• • • Testing phase (50% novel items, 50% known items) Only plural triggers Accuracy recorded for press Final voicing vs. Final devoicing 18

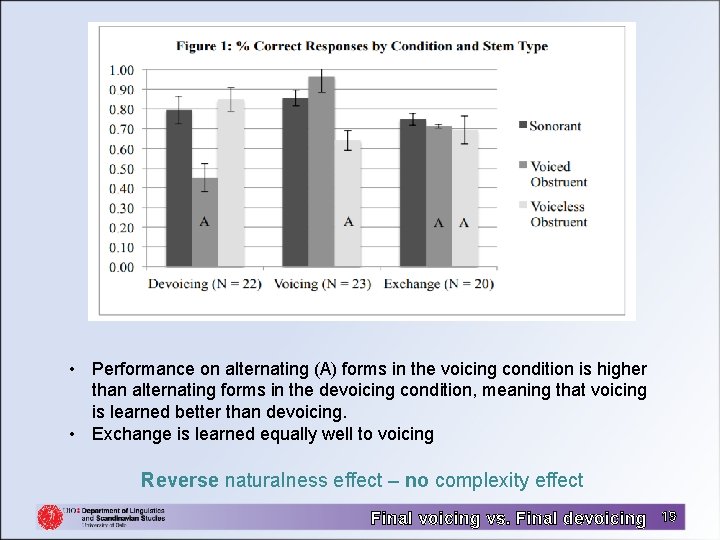

• Performance on alternating (A) forms in the voicing condition is higher than alternating forms in the devoicing condition, meaning that voicing is learned better than devoicing. • Exchange is learned equally well to voicing Reverse naturalness effect – no complexity effect Final voicing vs. Final devoicing 19

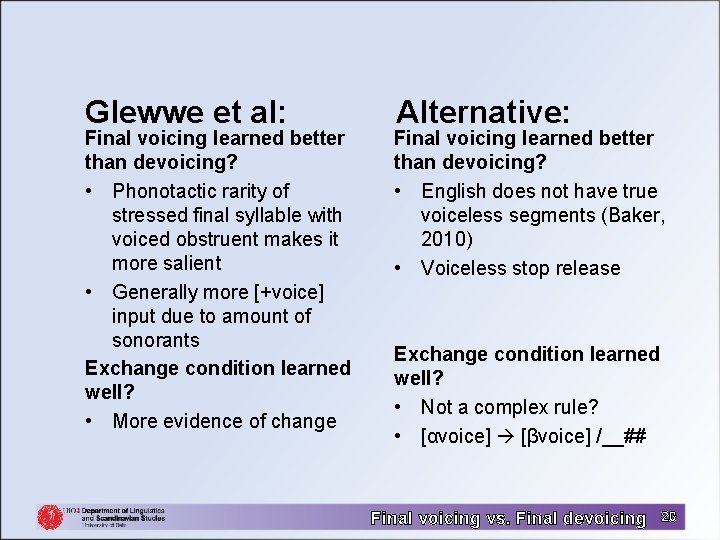

Glewwe et al: Final voicing learned better than devoicing? • Phonotactic rarity of stressed final syllable with voiced obstruent makes it more salient • Generally more [+voice] input due to amount of sonorants Exchange condition learned well? • More evidence of change Alternative: Final voicing learned better than devoicing? • English does not have true voiceless segments (Baker, 2010) • Voiceless stop release Exchange condition learned well? • Not a complex rule? • [αvoice] [βvoice] /__## Final voicing vs. Final devoicing 20

Final voicing vs. Final devoicing 21

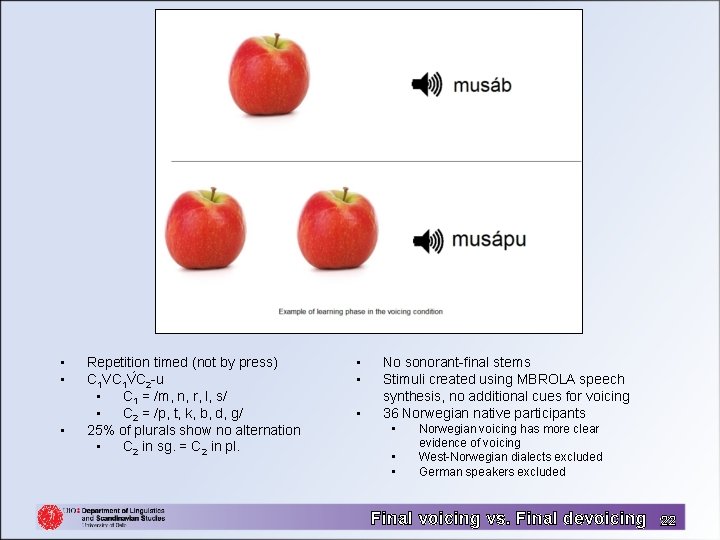

• • • Repetition timed (not by press) C 1 V C 2 -u • C 1 = /m, n, r, l, s/ • C 2 = /p, t, k, b, d, g/ 25% of plurals show no alternation • C 2 in sg. = C 2 in pl. • • • No sonorant-final stems Stimuli created using MBROLA speech synthesis, no additional cues for voicing 36 Norwegian native participants • • • Norwegian voicing has more clear evidence of voicing West-Norwegian dialects excluded German speakers excluded Final voicing vs. Final devoicing 22

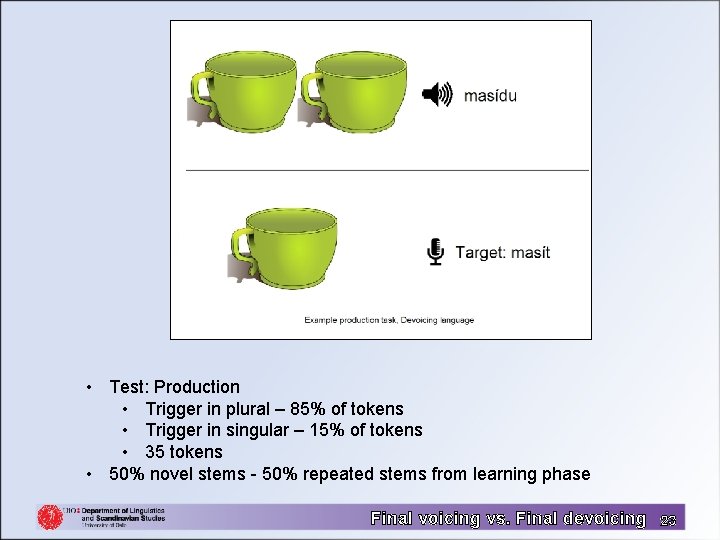

• Test: Production • Trigger in plural – 85% of tokens • Trigger in singular – 15% of tokens • 35 tokens • 50% novel stems - 50% repeated stems from learning phase Final voicing vs. Final devoicing 23

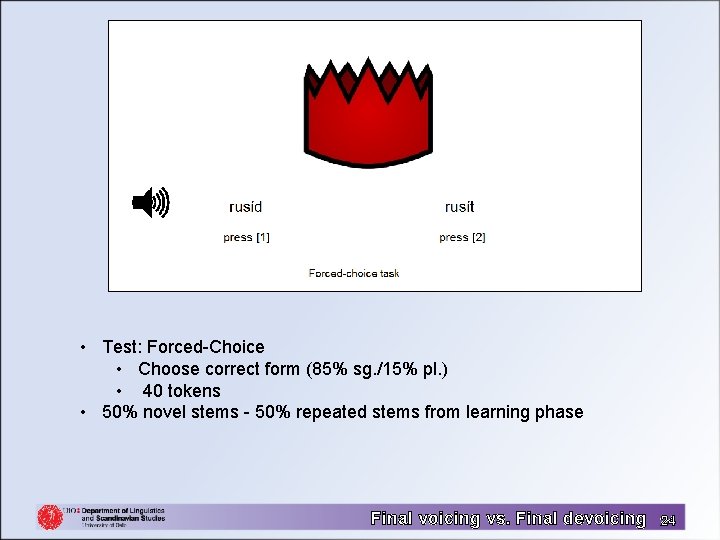

• Test: Forced-Choice • Choose correct form (85% sg. /15% pl. ) • 40 tokens • 50% novel stems - 50% repeated stems from learning phase Final voicing vs. Final devoicing 24

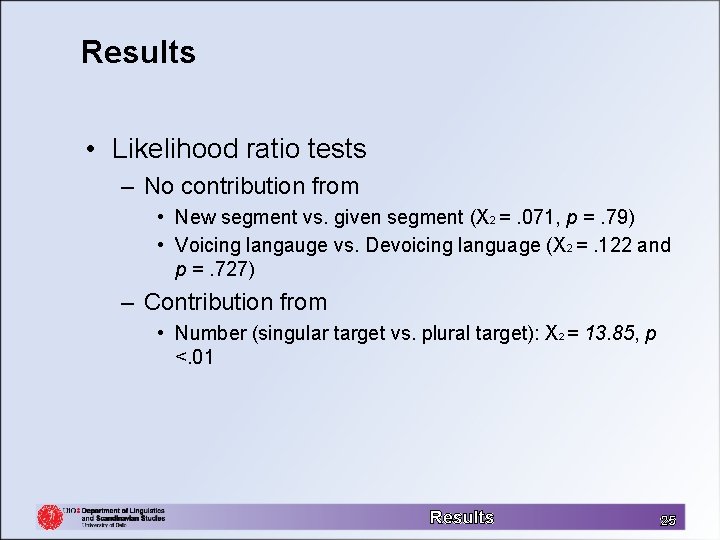

Results • Likelihood ratio tests – No contribution from • New segment vs. given segment (X 2 =. 071, p =. 79) • Voicing langauge vs. Devoicing language (X 2 =. 122 and p =. 727) – Contribution from • Number (singular target vs. plural target): X 2 = 13. 85, p <. 01 Results 25

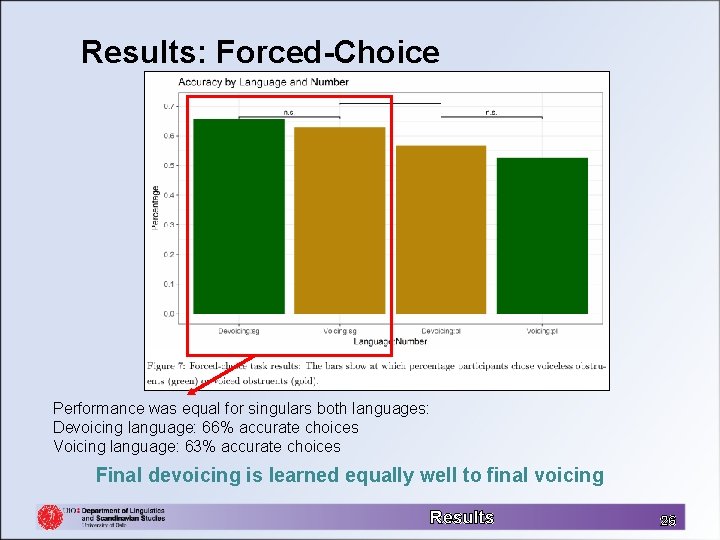

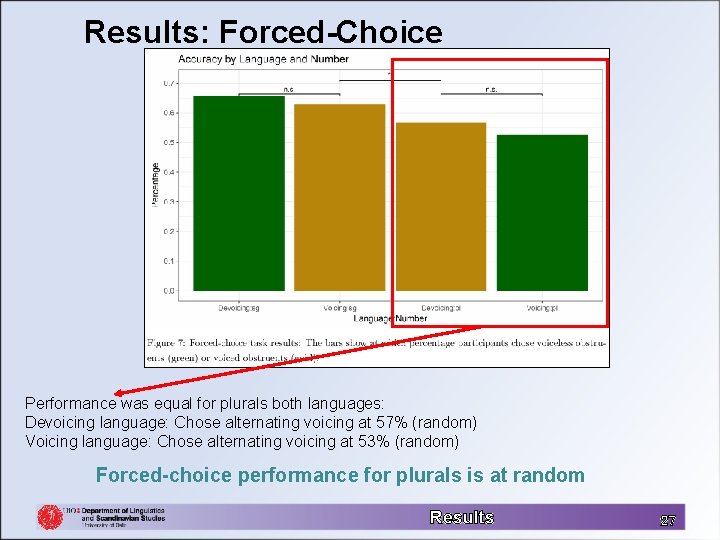

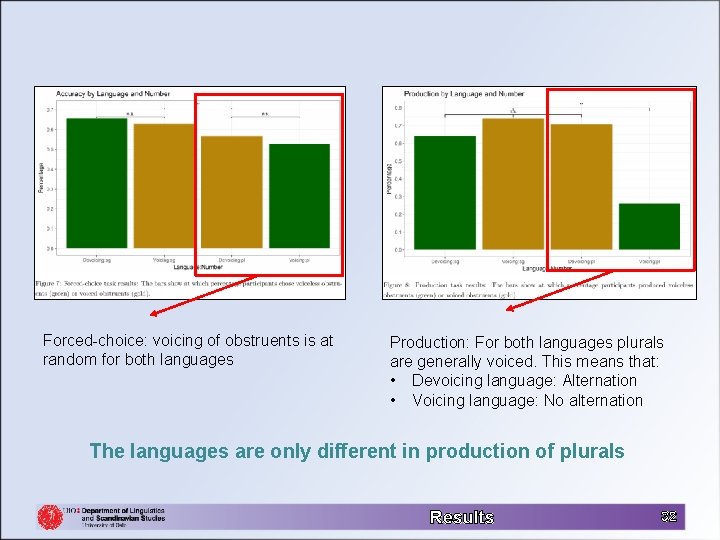

Results: Forced-Choice Performance was equal for singulars both languages: Devoicing language: 66% accurate choices Voicing language: 63% accurate choices Final devoicing is learned equally well to final voicing Results 26

Results: Forced-Choice Performance was equal for plurals both languages: Devoicing language: Chose alternating voicing at 57% (random) Voicing language: Chose alternating voicing at 53% (random) Forced-choice performance for plurals is at random Results 27

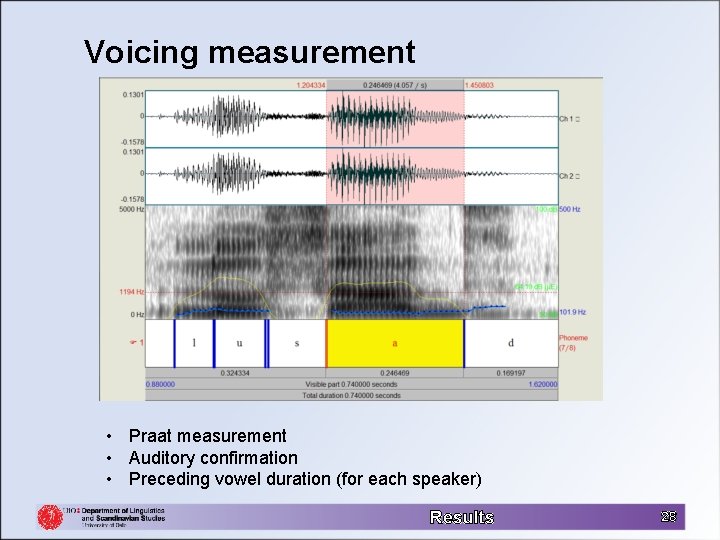

Voicing measurement • Praat measurement • Auditory confirmation • Preceding vowel duration (for each speaker) Results 28

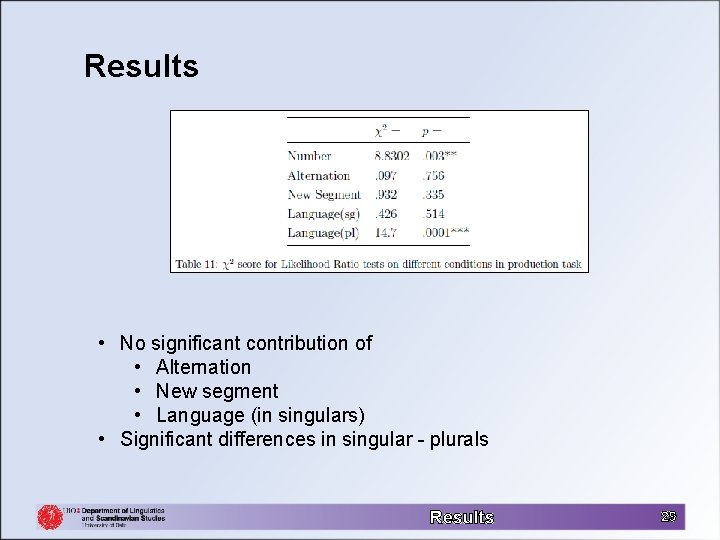

Results • No significant contribution of • Alternation • New segment • Language (in singulars) • Significant differences in singular - plurals Results 29

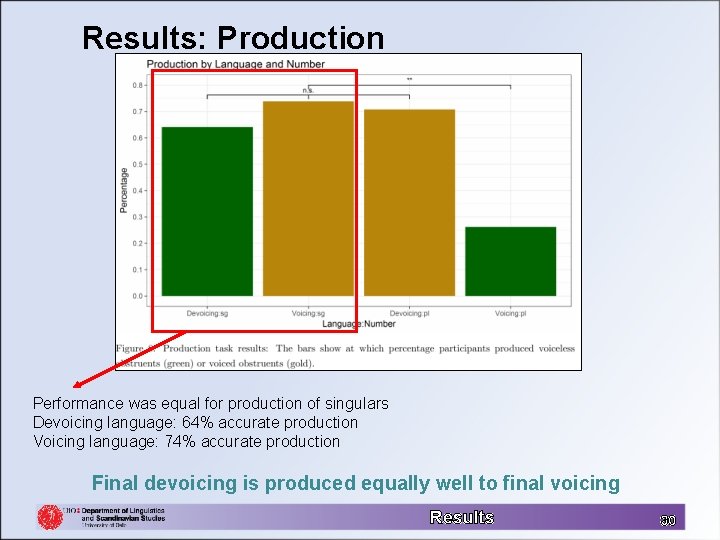

Results: Production Performance was equal for production of singulars Devoicing language: 64% accurate production Voicing language: 74% accurate production Final devoicing is produced equally well to final voicing Results 30

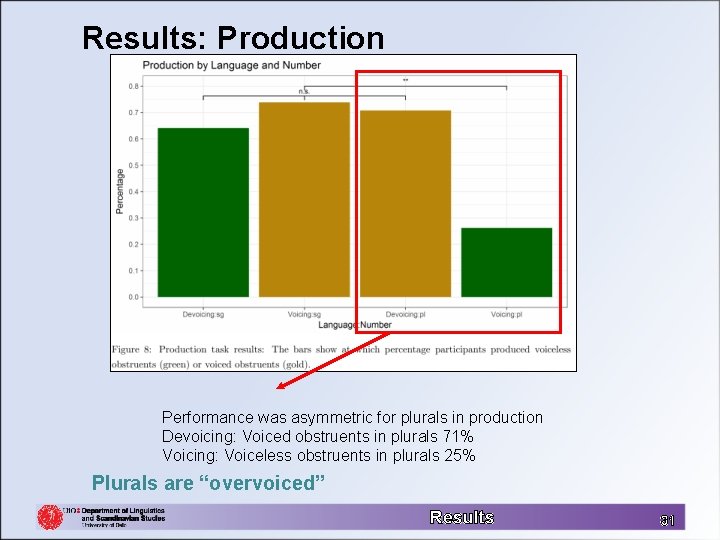

Results: Production Performance was asymmetric for plurals in production Devoicing: Voiced obstruents in plurals 71% Voicing: Voiceless obstruents in plurals 25% Plurals are “overvoiced” Results 31

Forced-choice: voicing of obstruents is at random for both languages Production: For both languages plurals are generally voiced. This means that: • Devoicing language: Alternation • Voicing language: No alternation The languages are only different in production of plurals Results 32

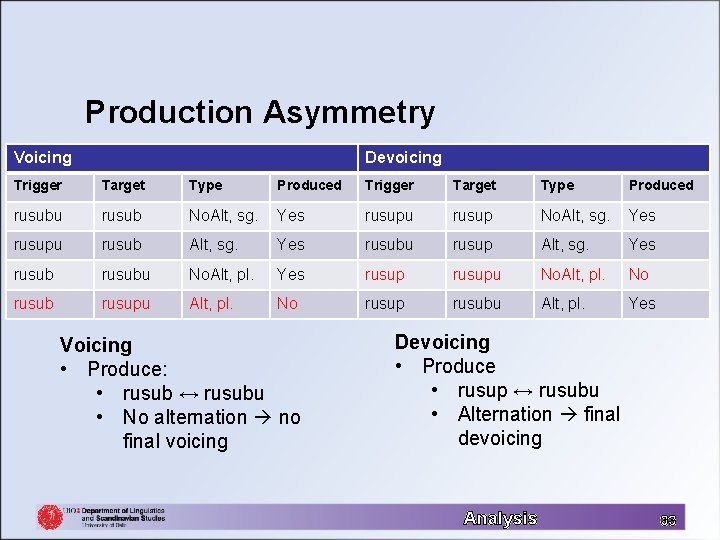

Production Asymmetry Voicing Devoicing Trigger Target Type Produced rusubu rusub No. Alt, sg. Yes rusupu rusup No. Alt, sg. Yes rusupu rusub Alt, sg. Yes rusubu rusup Alt, sg. Yes rusubu No. Alt, pl. Yes rusupu No. Alt, pl. No rusub rusupu Alt, pl. No rusup rusubu Alt, pl. Yes Voicing • Produce: • rusub ↔ rusubu • No alternation no final voicing Devoicing • Produce • rusup ↔ rusubu • Alternation final devoicing Analysis 33

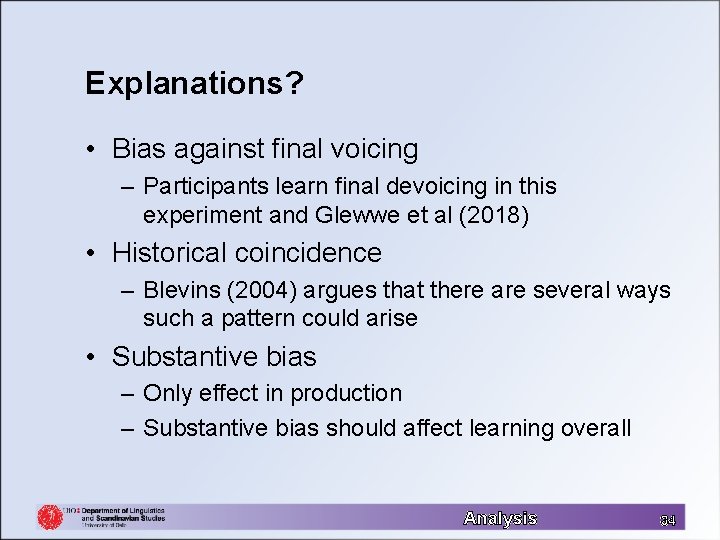

Explanations? • Bias against final voicing – Participants learn final devoicing in this experiment and Glewwe et al (2018) • Historical coincidence – Blevins (2004) argues that there are several ways such a pattern could arise • Substantive bias – Only effect in production – Substantive bias should affect learning overall Analysis 34

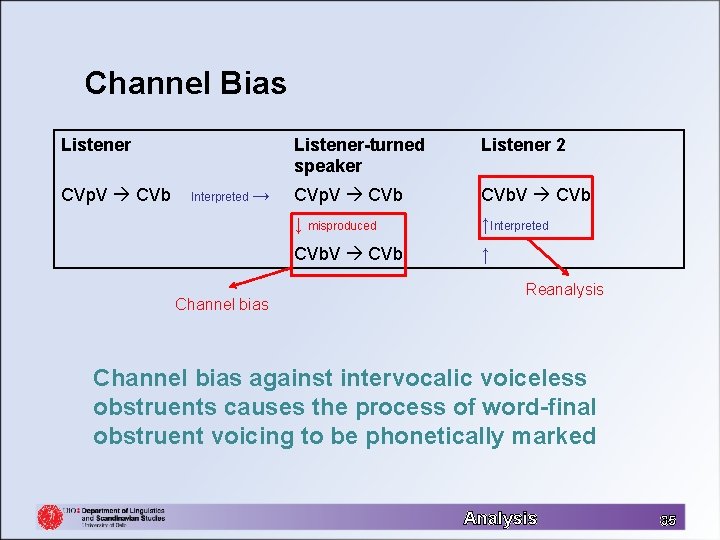

Channel Bias Listener CVp. V CVb Interpreted → Channel bias Listener-turned speaker Listener 2 CVp. V CVb ↓ misproduced ↑Interpreted CVb. V CVb ↑ Reanalysis Channel bias against intervocalic voiceless obstruents causes the process of word-final obstruent voicing to be phonetically marked Analysis 35

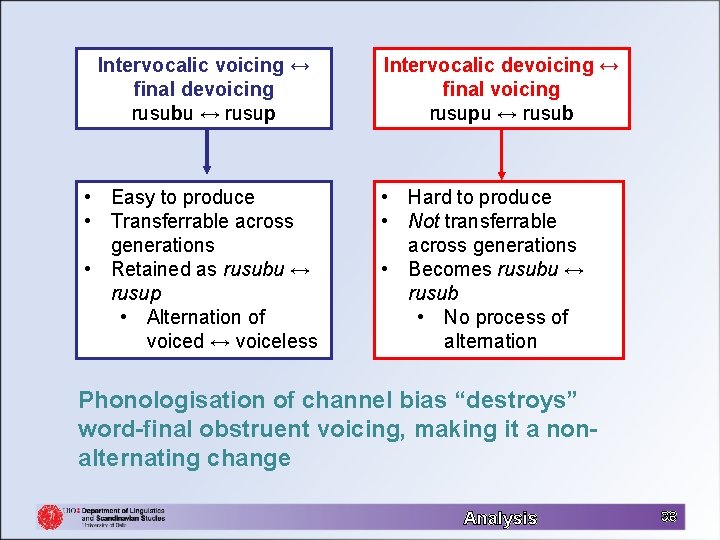

Intervocalic voicing ↔ final devoicing rusubu ↔ rusup • Easy to produce • Transferrable across generations • Retained as rusubu ↔ rusup • Alternation of voiced ↔ voiceless Intervocalic devoicing ↔ final voicing rusupu ↔ rusub • Hard to produce • Not transferrable across generations • Becomes rusubu ↔ rusub • No process of alternation Phonologisation of channel bias “destroys” word-final obstruent voicing, making it a nonalternating change Analysis 36

Conclusion • No evidence of biases against word-final voiced obstruents • Evidence for channel bias against intervocalic voiceless obstruents • Explains why a synchronic process of voiocing does not occur • No evidence for substantive biases, in line with much other research Conclusion 37

Research Plans • Iterated learning – An iterated learning paradigm with word-final voicing and devoicing – See if the prediction carries out in a simulated generation transfer • Substantive bias – Investigate the differences in research that finds substantive biases, and the ones that do not • Phonetic precursor strength – Is the phonetic cues stronger for intervocalic voicing than final devoicing? Future research 38

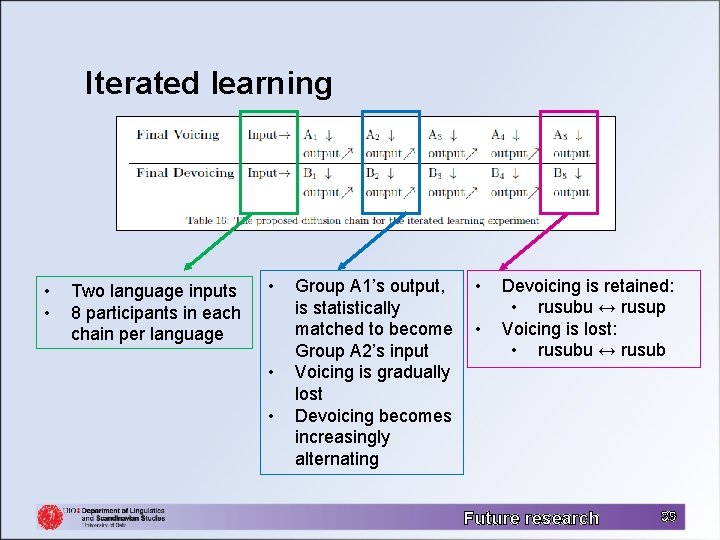

Iterated learning • • Two language inputs 8 participants in each chain per language • • • Group A 1’s output, is statistically matched to become Group A 2’s input Voicing is gradually lost Devoicing becomes increasingly alternating • • Devoicing is retained: • rusubu ↔ rusup Voicing is lost: • rusubu ↔ rusub Future research 39

Thank you all for listening! 40

References Archangeli, D. B. , & Pulleyblank, D. G. (1994). Grounded phonology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Blevins, J. (2004). Evolutionary phonology: The emergence of sound patterns. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Chomsky, N. , & Halle, M. (1968). The sound pattern of English. NY: Harper & Row. Finley, S. (2012). Typological asymmetries in round vowel harmony: Support from Artificial Grammar Learning. Language and Cognitive Processes, 27(10), 1550 -1562. Glewwe, E. , Zymet, J. , Adams, J. , Jacobson, R. , Yates, A. , Zeng, A. , & Daland, R. (2018). Substantive bias and the acquisition of final (de)voicing patterns. Salt, Lake, City: Talk Given at the 92 nd Annual Meeting of the Linguistic Society of America (LSA). Harris, J. (1990). Segmental complexity and phonological government. Phonology, 7, 255 -300. Hayes, B. , Kirchner, R. , & Steriade, D. (2004). Phonetically based phonology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Kiparsky, P. (2006). The Amphichronic Program vs. Evolutionary Phonology. Theoretical Linguistics, 32, 217236. Mc. Carthy, J. , & Prince, A. (1995). Faithfulness and reduplicative identity. In University of Massachusetts Occasional Papers in Linguistics 18: Papers in Optimality Theory (pp. 249 -384). GLSA, University of Massachussetts, Amherst. Pycha, A. , Nowak, P. , Shin, E. , & Shosted, R. (2003). Phonological rule-learning and its implications for a theory of vowel harmony. In G. Garding, & M. Tsujimura (Eds. ), Proceedings of the 22 nd West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (Vol. 22, pp. 533 -546). Somerville, MA: Cascadilla. Vijver, R. , & Baer-Henney, D. (2014). Developing biases. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1 -8. 41

- Slides: 40