CFD 6 Computer Fluid Dynamics 2181106 E 181107

- Slides: 67

CFD 6 Computer Fluid Dynamics 2181106 E 181107 Turbulent flows, … Remark: foils with „black background“ could be skipped, they are aimed to the more advanced courses Rudolf Žitný, Ústav procesní a zpracovatelské techniky ČVUT FS 2010 Some figures and equations are copied from Wikipedia

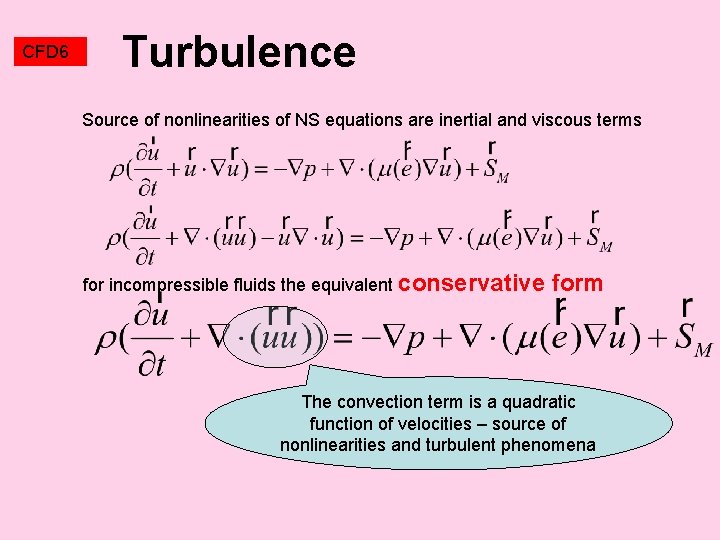

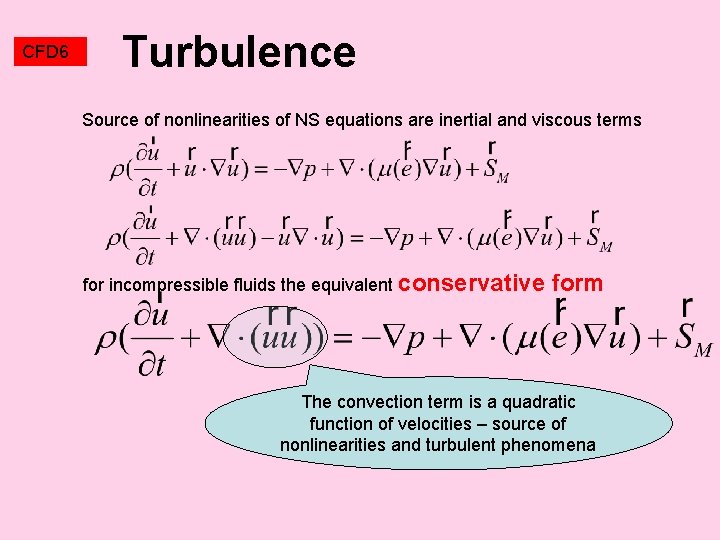

CFD 6 Turbulence Source of nonlinearities of NS equations are inertial and viscous terms for incompressible fluids the equivalent conservative form The convection term is a quadratic function of velocities – source of nonlinearities and turbulent phenomena

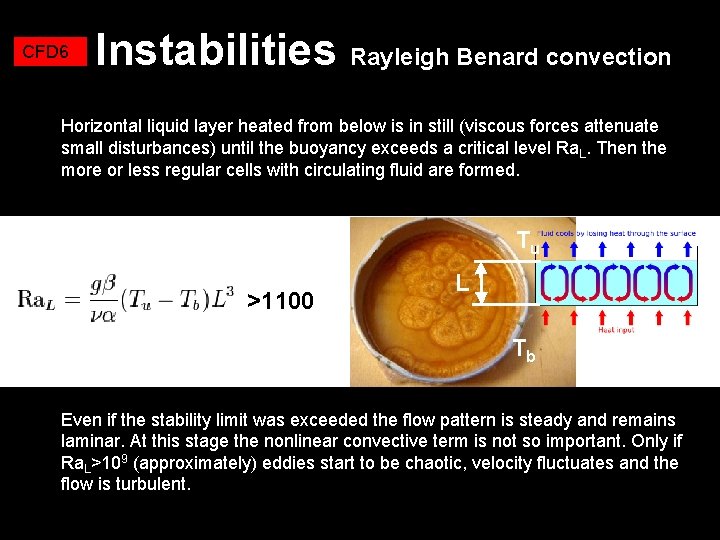

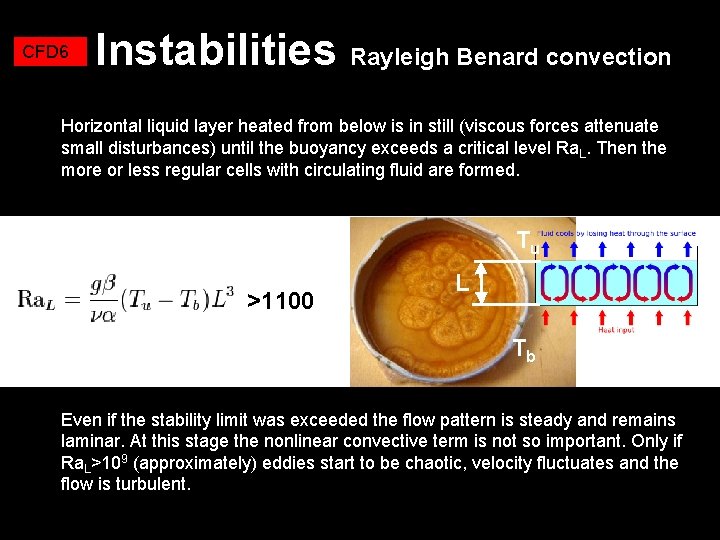

CFD 6 Instabilities Rayleigh Benard convection Horizontal liquid layer heated from below is in still (viscous forces attenuate small disturbances) until the buoyancy exceeds a critical level Ra. L. Then the more or less regular cells with circulating fluid are formed. Tu >1100 L Tb Even if the stability limit was exceeded the flow pattern is steady and remains laminar. At this stage the nonlinear convective term is not so important. Only if Ra. L>109 (approximately) eddies start to be chaotic, velocity fluctuates and the flow is turbulent.

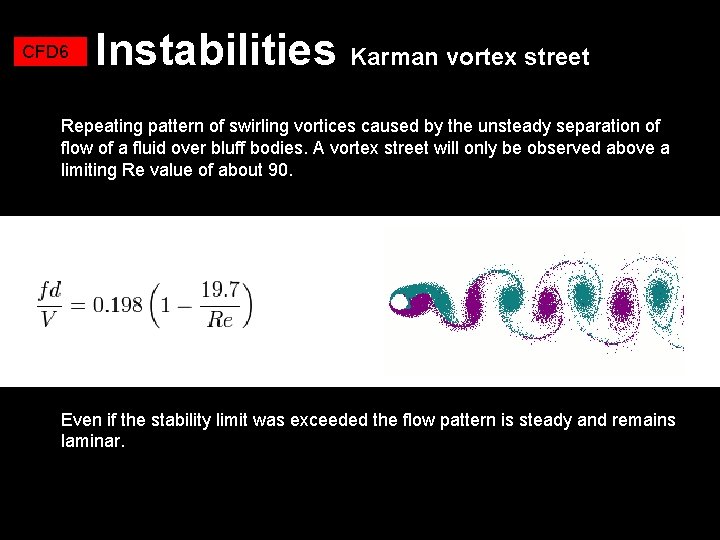

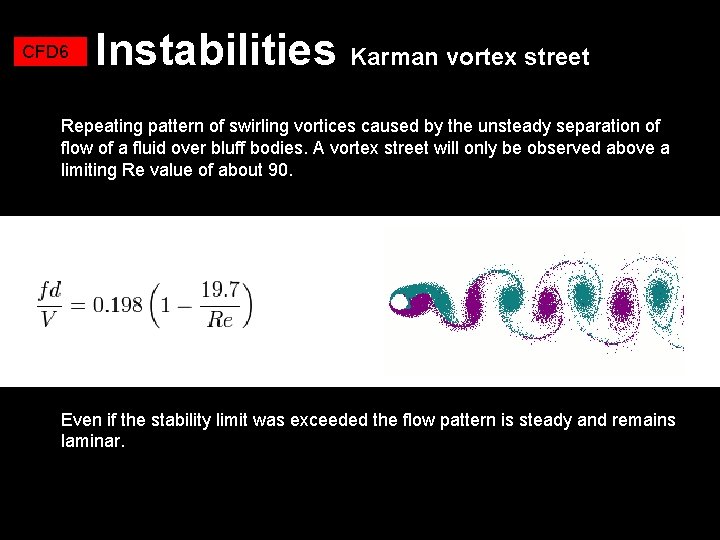

CFD 6 Instabilities Karman vortex street Repeating pattern of swirling vortices caused by the unsteady separation of flow of a fluid over bluff bodies. A vortex street will only be observed above a limiting Re value of about 90. L Even if the stability limit was exceeded the flow pattern is steady and remains laminar.

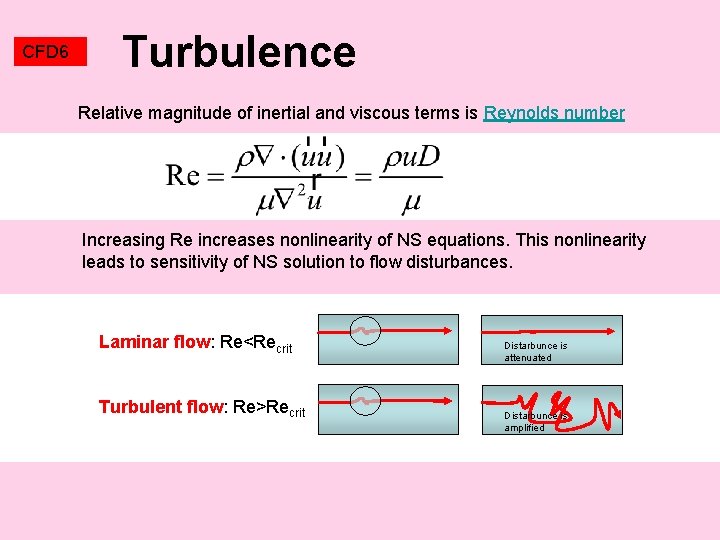

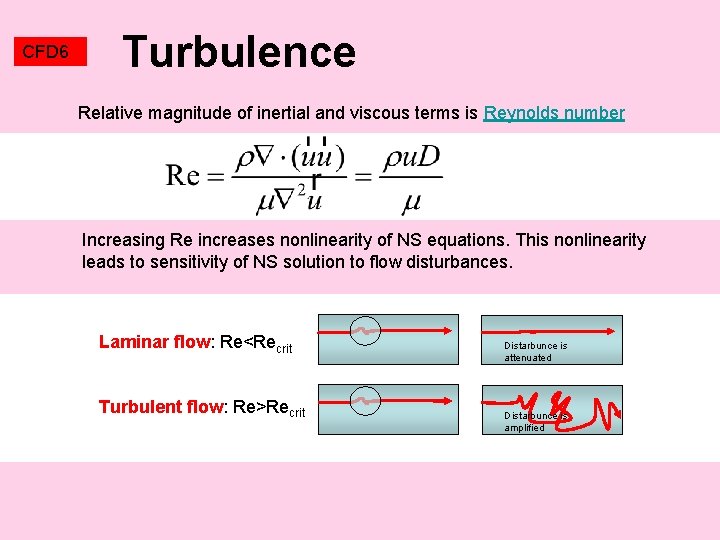

CFD 6 Turbulence Relative magnitude of inertial and viscous terms is Reynolds number Increasing Re increases nonlinearity of NS equations. This nonlinearity leads to sensitivity of NS solution to flow disturbances. Laminar flow: Re<Recrit Turbulent flow: Re>Recrit Distarbunce is attenuated Distarbunce is amplified

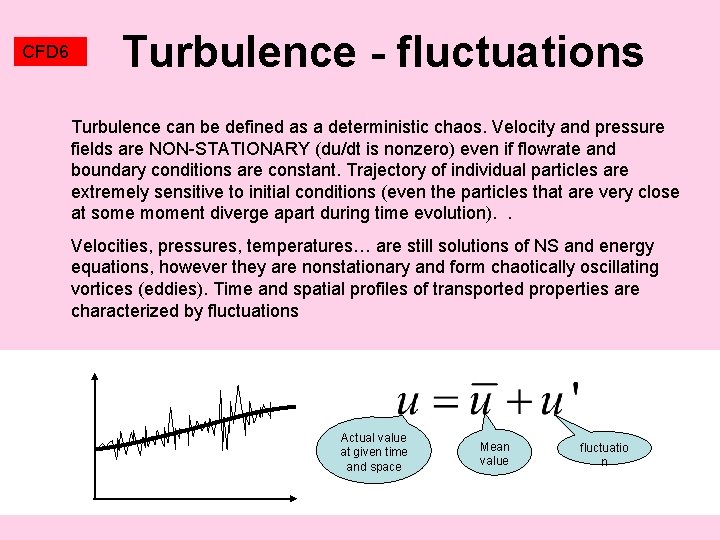

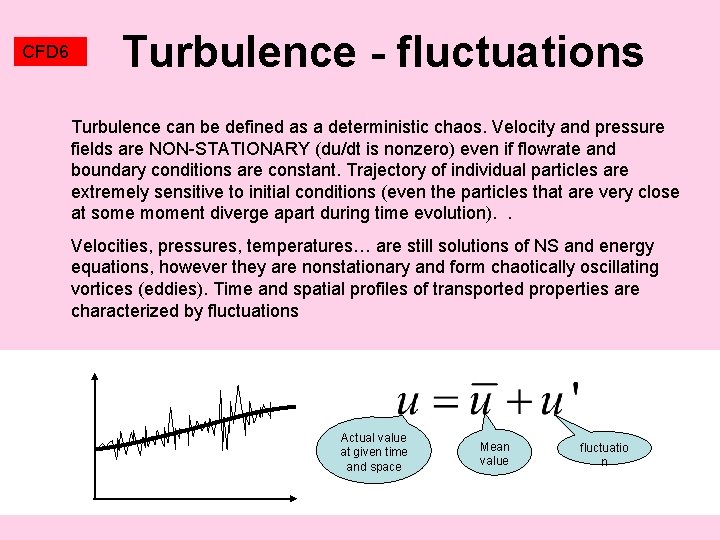

CFD 6 Turbulence - fluctuations Turbulence can be defined as a deterministic chaos. Velocity and pressure fields are NON-STATIONARY (du/dt is nonzero) even if flowrate and boundary conditions are constant. Trajectory of individual particles are extremely sensitive to initial conditions (even the particles that are very close at some moment diverge apart during time evolution). . Velocities, pressures, temperatures… are still solutions of NS and energy equations, however they are nonstationary and form chaotically oscillating vortices (eddies). Time and spatial profiles of transported properties are characterized by fluctuations Actual value at given time and space Mean value fluctuatio n

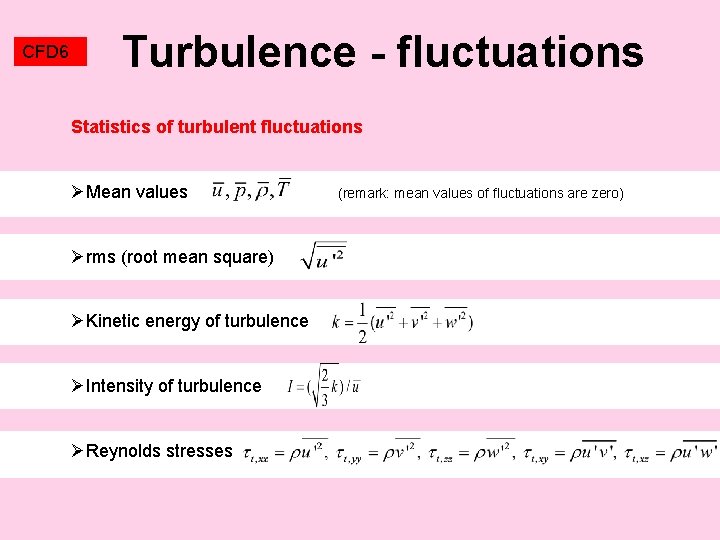

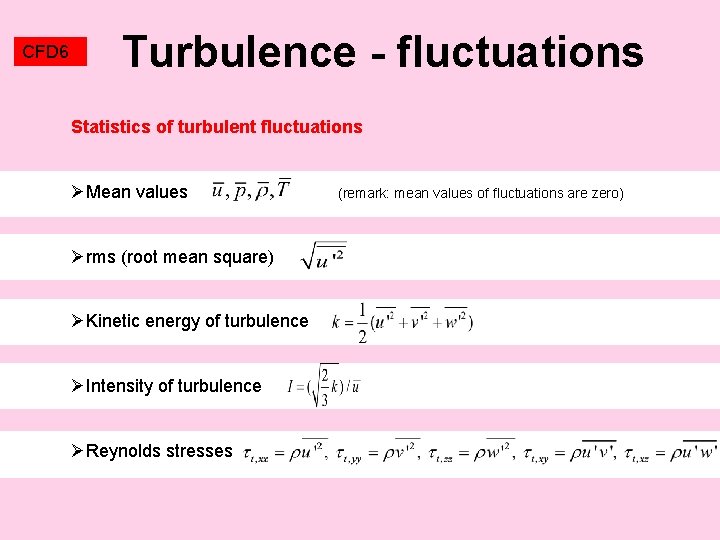

CFD 6 Turbulence - fluctuations Statistics of turbulent fluctuations ØMean values (remark: mean values of fluctuations are zero) Ørms (root mean square) ØKinetic energy of turbulence ØIntensity of turbulence ØReynolds stresses

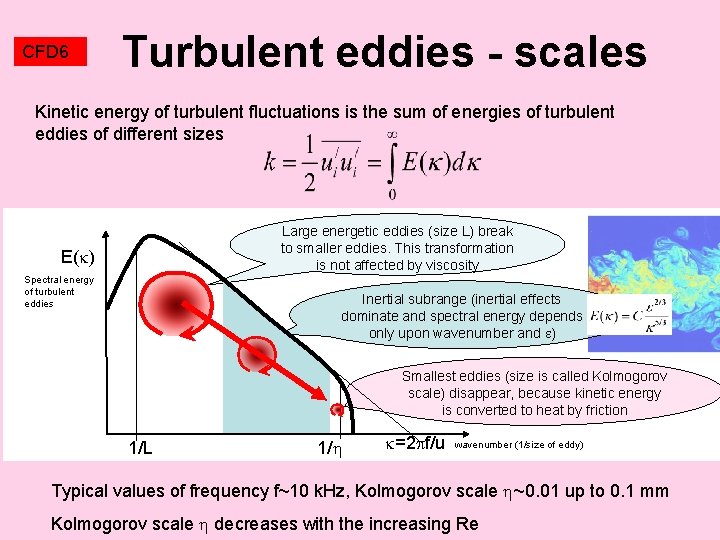

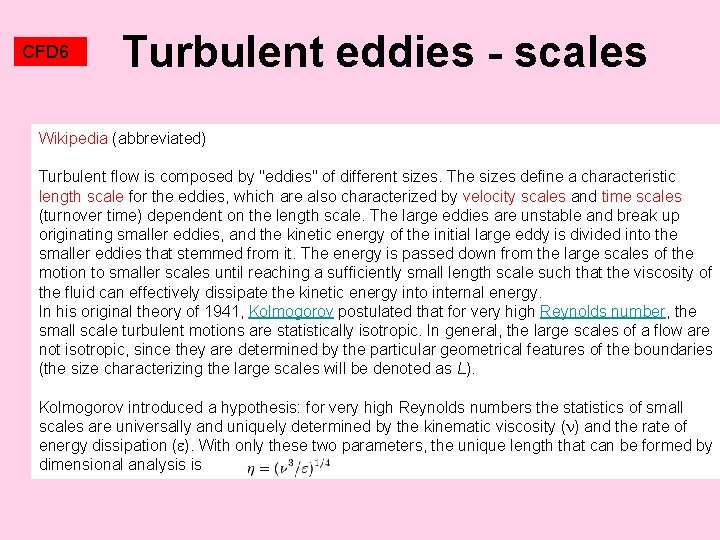

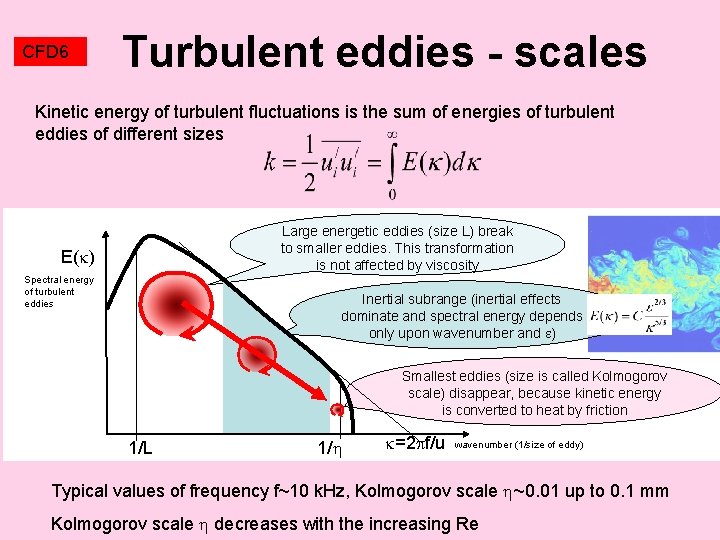

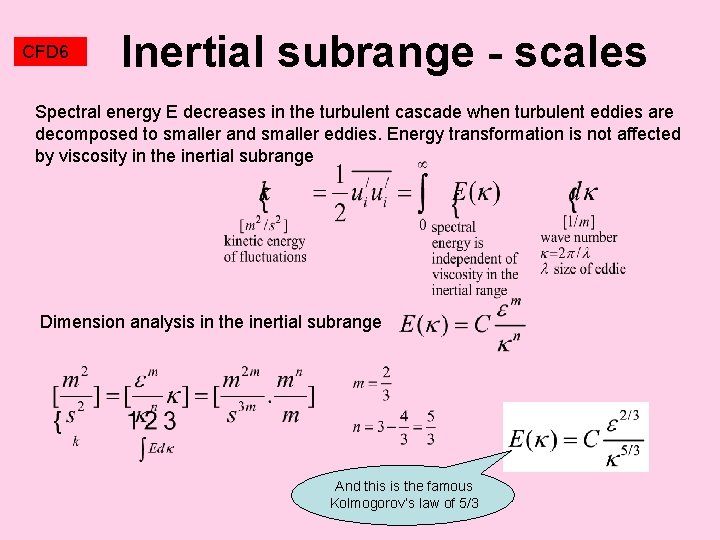

CFD 6 Turbulent eddies - scales Kinetic energy of turbulent fluctuations is the sum of energies of turbulent eddies of different sizes E( ) Spectral energy of turbulent eddies Large energetic eddies (size L) break to smaller eddies. This transformation is not affected by viscosity Inertial subrange (inertial effects dominate and spectral energy depends only upon wavenumber and ) Smallest eddies (size is called Kolmogorov scale) disappear, because kinetic energy is converted to heat by friction 1/L 1/ =2 f/u wavenumber (1/size of eddy) Typical values of frequency f~10 k. Hz, Kolmogorov scale ~0. 01 up to 0. 1 mm Kolmogorov scale decreases with the increasing Re

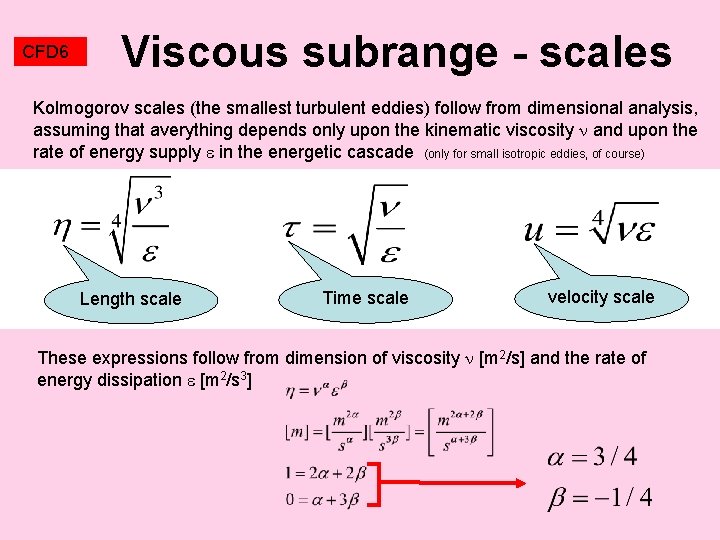

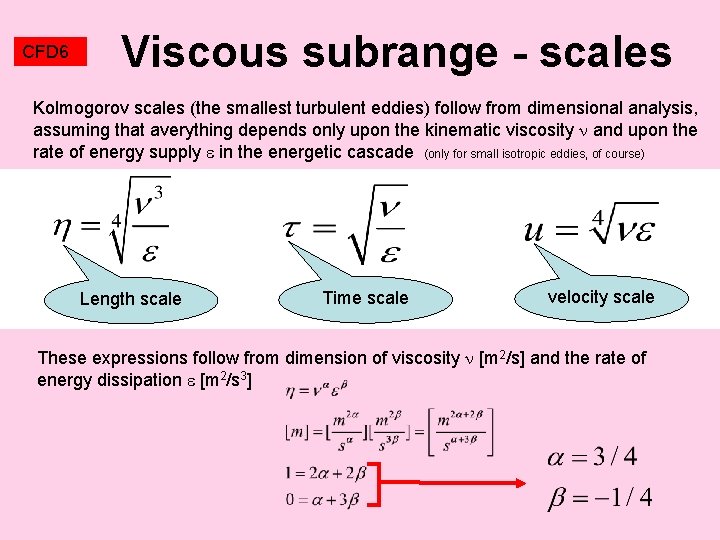

CFD 6 Viscous subrange - scales Kolmogorov scales (the smallest turbulent eddies) follow from dimensional analysis, assuming that averything depends only upon the kinematic viscosity and upon the rate of energy supply in the energetic cascade (only for small isotropic eddies, of course) Length scale Time scale velocity scale These expressions follow from dimension of viscosity [m 2/s] and the rate of energy dissipation [m 2/s 3]

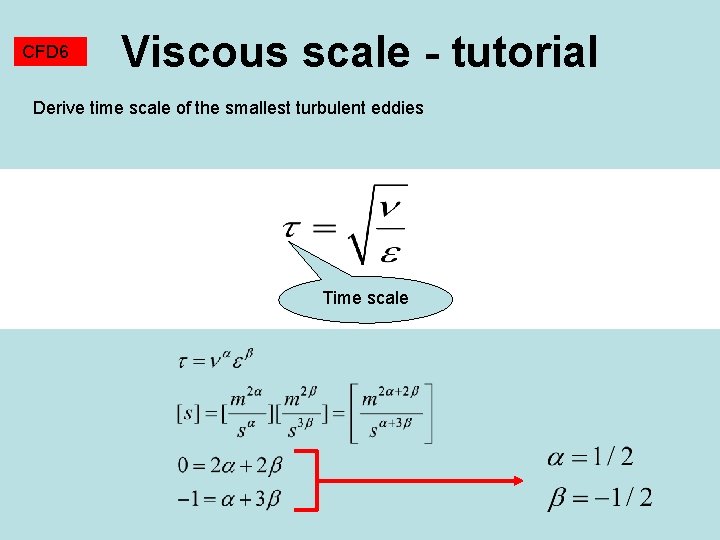

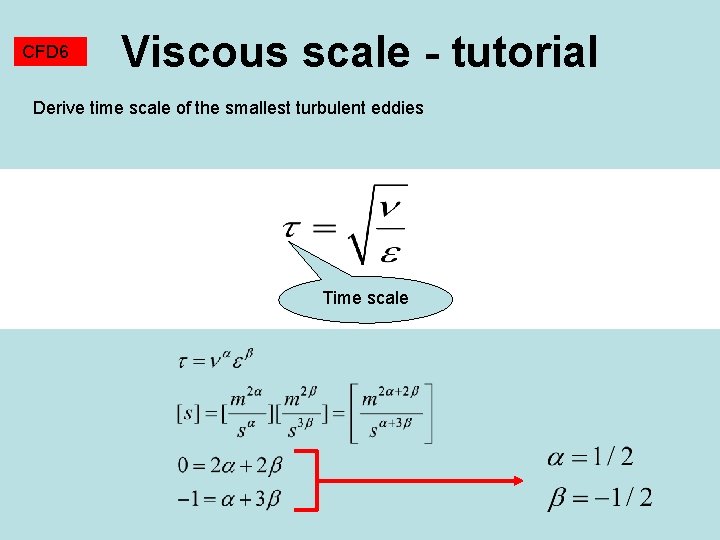

CFD 6 Viscous scale - tutorial Derive time scale of the smallest turbulent eddies Time scale

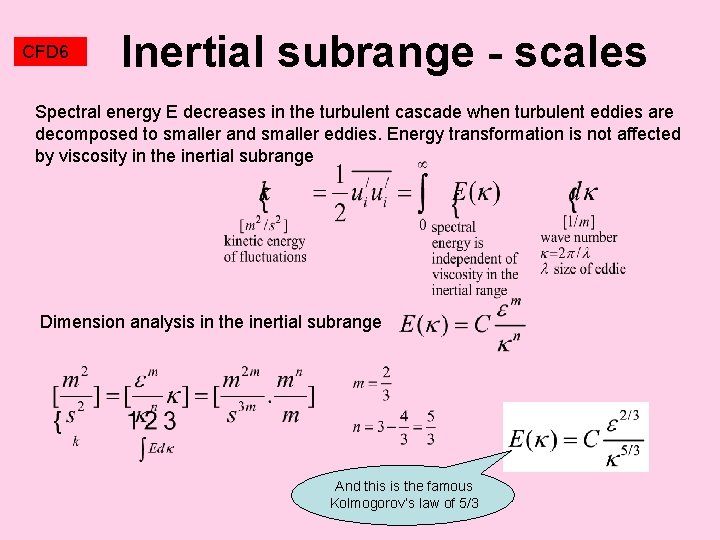

CFD 6 Inertial subrange - scales Spectral energy E decreases in the turbulent cascade when turbulent eddies are decomposed to smaller and smaller eddies. Energy transformation is not affected by viscosity in the inertial subrange Dimension analysis in the inertial subrange And this is the famous Kolmogorov’s law of 5/3

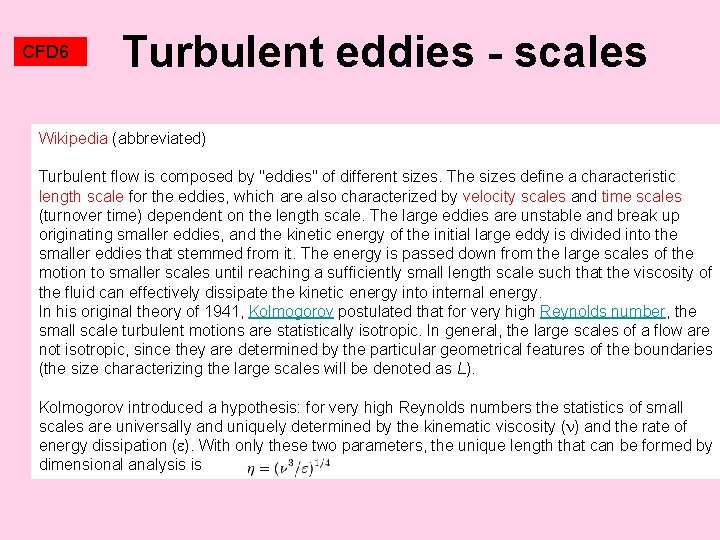

CFD 6 Turbulent eddies - scales Wikipedia (abbreviated) Turbulent flow is composed by "eddies" of different sizes. The sizes define a characteristic length scale for the eddies, which are also characterized by velocity scales and time scales (turnover time) dependent on the length scale. The large eddies are unstable and break up originating smaller eddies, and the kinetic energy of the initial large eddy is divided into the smaller eddies that stemmed from it. The energy is passed down from the large scales of the motion to smaller scales until reaching a sufficiently small length scale such that the viscosity of the fluid can effectively dissipate the kinetic energy into internal energy. In his original theory of 1941, Kolmogorov postulated that for very high Reynolds number, the small scale turbulent motions are statistically isotropic. In general, the large scales of a flow are not isotropic, since they are determined by the particular geometrical features of the boundaries (the size characterizing the large scales will be denoted as L). Kolmogorov introduced a hypothesis: for very high Reynolds numbers the statistics of small scales are universally and uniquely determined by the kinematic viscosity ( ) and the rate of energy dissipation ( ). With only these two parameters, the unique length that can be formed by dimensional analysis is

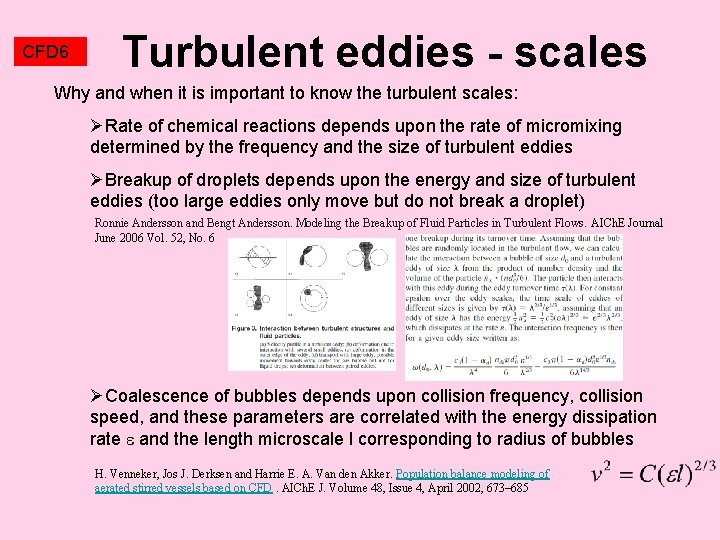

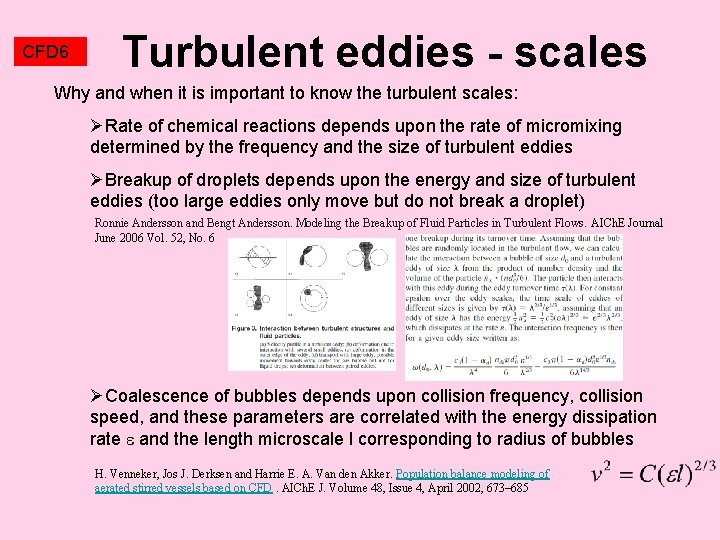

CFD 6 Turbulent eddies - scales Why and when it is important to know the turbulent scales: ØRate of chemical reactions depends upon the rate of micromixing determined by the frequency and the size of turbulent eddies ØBreakup of droplets depends upon the energy and size of turbulent eddies (too large eddies only move but do not break a droplet) Ronnie Andersson and Bengt Andersson. Modeling the Breakup of Fluid Particles in Turbulent Flows. AICh. E Journal June 2006 Vol. 52, No. 6 ØCoalescence of bubbles depends upon collision frequency, collision speed, and these parameters are correlated with the energy dissipation rate and the length microscale l corresponding to radius of bubbles H. Venneker, Jos J. Derksen and Harrie E. A. Van den Akker. Population balance modeling of aerated stirred vessels based on CFD. AICh. E J. Volume 48, Issue 4, April 2002, 673– 685

CFD 6 DNS Direct Numerical Simulation In order to resolve all details of turbulent structures it is necessary to use mesh with grid size less than the size of the smallest (Kolmogorov) eddies. N-grid points in one direction should be (based upon dimensional ground) L Velocity scale u in previous expression is related to magnitude of turbulent fluctuations (rms of u’, or k). The Re related to the velocity fluctuation is called turbulent Reynolds number. No. of grid No. of time points in steps DNS 12300 380 6. 7 M 32 k 30800 40 M 47 k 61600 1450 150 M 63 k 230000 4650 2100 M 114 k Table concerns DNS modelling of channel flow experiments (rewritten from Wilcox: Turbulence modelling, chapter 8). Remark: Re~106 or 107 at flow around a car or flow around wings

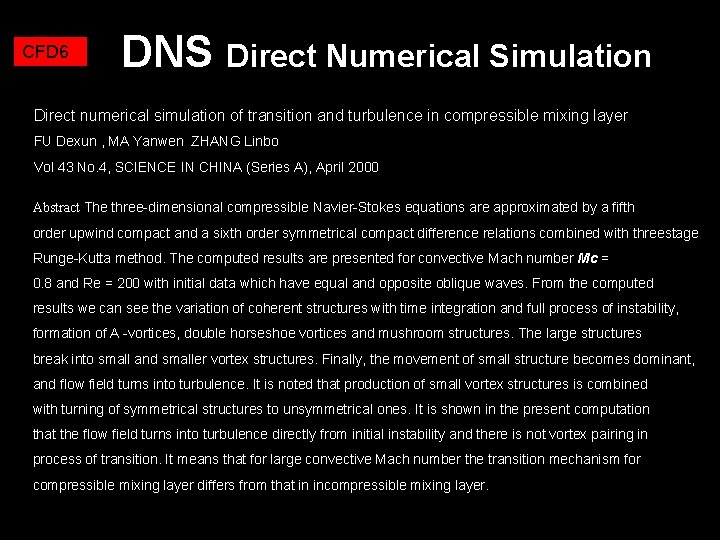

CFD 6 DNS Direct Numerical Simulation Direct numerical simulation of transition and turbulence in compressible mixing layer FU Dexun , MA Yanwen ZHANG Linbo Vol 43 No. 4, SCIENCE IN CHINA (Series A), April 2000 Abstract The three-dimensional compressible Navier-Stokes equations are approximated by a fifth order upwind compact and a sixth order symmetrical compact difference relations combined with threestage Runge-Kutta method. The computed results are presented for convective Mach number Mc = 0. 8 and Re = 200 with initial data which have equal and opposite oblique waves. From the computed results we can see the variation of coherent structures with time integration and full process of instability, formation of A -vortices, double horseshoe vortices and mushroom structures. The large structures break into small and smaller vortex structures. Finally, the movement of small structure becomes dominant, and flow field turns into turbulence. It is noted that production of small vortex structures is combined with turning of symmetrical structures to unsymmetrical ones. It is shown in the present computation that the flow field turns into turbulence directly from initial instability and there is not vortex pairing in process of transition. It means that for large convective Mach number the transition mechanism for compressible mixing layer differs from that in incompressible mixing layer.

CFD 6 DNS Direct Numerical Simulation DNS AND LES OF TURBULENT BACKWARD-FACING STEP FLOW USING 2 ND- AND 4 TH-ORDER DISCRETIZATION ADNAN MERI AND HANS WENGLE Abstract. Results are presented from a Direct Numerical Simulation (DNS) and Large-Eddy Simulations (LES) of turbulent flow over a backward-facing step with a fully developed channel flow utilized as a time-dependent inflow condition. Numerical solutions using a fourth-order compact (Hermitian) scheme, which was formulated directly for a non-equidistant and staggered grid in [1] are compared with numerical solutions using the classical second-order central scheme. The results from LES (using the dynamic subgrid scale model) are evaluated against a corresponding DNS reference data set (fourth-order solution).

CFD 6 Transition Laminar-Turbulent Bacon

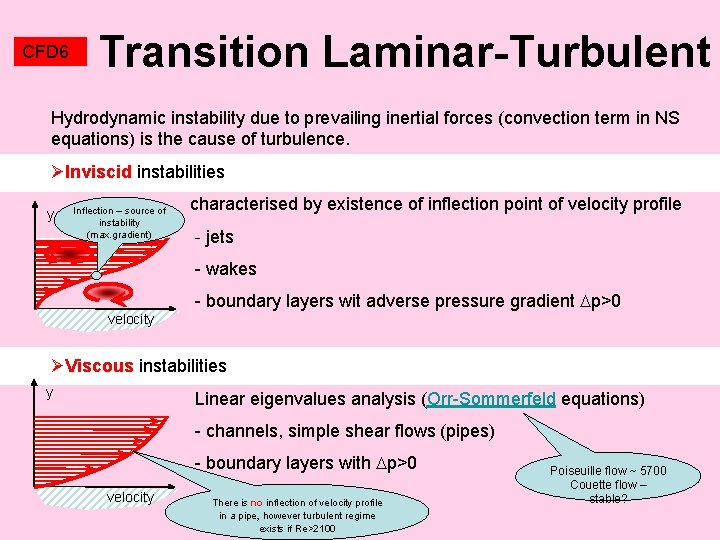

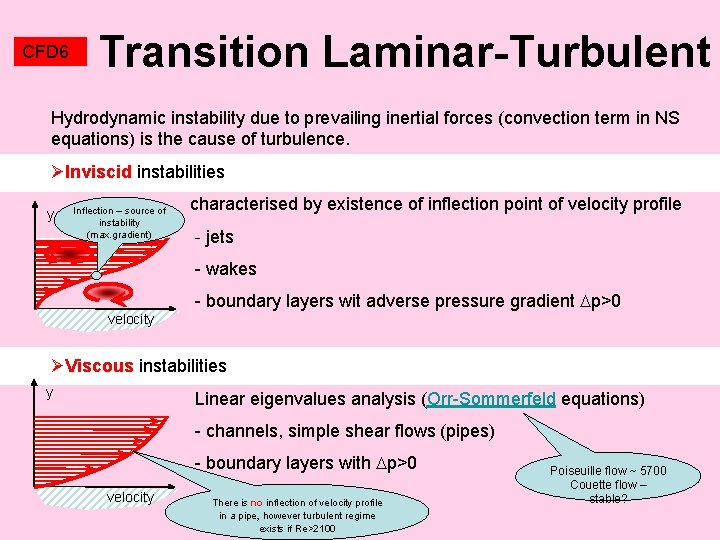

CFD 6 Transition Laminar-Turbulent Hydrodynamic instability due to prevailing inertial forces (convection term in NS equations) is the cause of turbulence. ØInviscid instabilities characterised by existence of inflection point of velocity profile Inflection – source of y instability (max. gradient) - jets - wakes - boundary layers wit adverse pressure gradient p>0 velocity ØViscous instabilities y Linear eigenvalues analysis (Orr-Sommerfeld equations) - channels, simple shear flows (pipes) - boundary layers with p>0 velocity There is no inflection of velocity profile in a pipe, however turbulent regime exists if Re>2100 Poiseuille flow ~ 5700 Couette flow – stable?

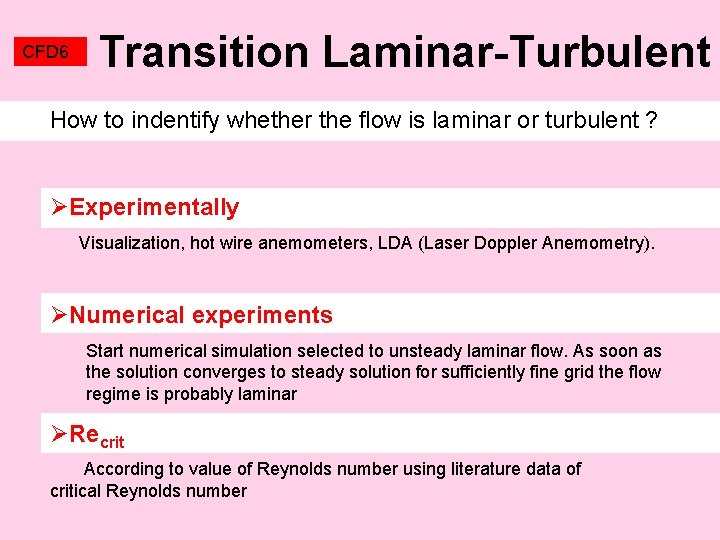

CFD 6 Transition Laminar-Turbulent How to indentify whether the flow is laminar or turbulent ? ØExperimentally Visualization, hot wire anemometers, LDA (Laser Doppler Anemometry). ØNumerical experiments Start numerical simulation selected to unsteady laminar flow. As soon as the solution converges to steady solution for sufficiently fine grid the flow regime is probably laminar ØRecrit According to value of Reynolds number using literature data of critical Reynolds number

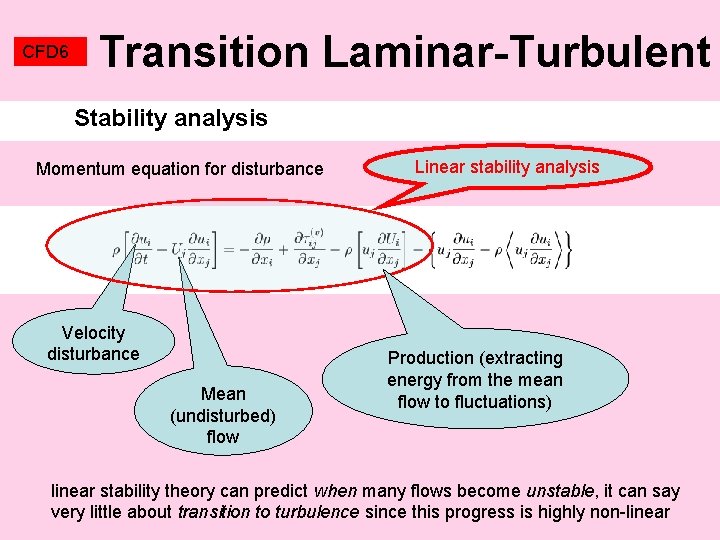

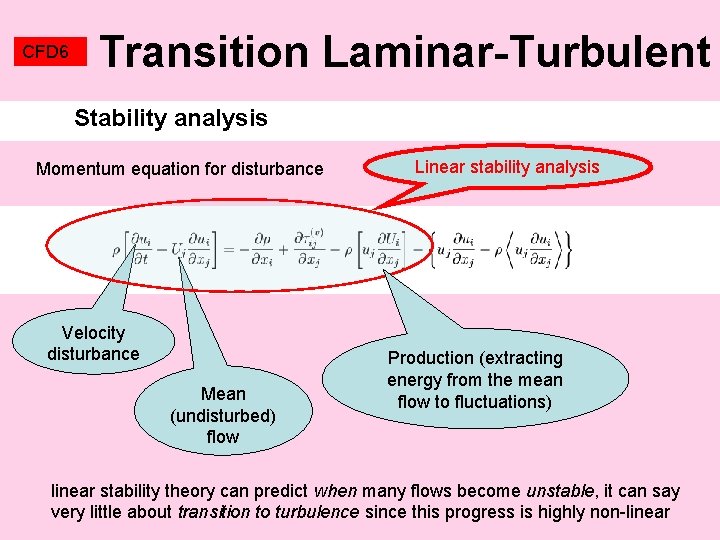

CFD 6 Transition Laminar-Turbulent Stability analysis Momentum equation for disturbance Velocity disturbance Mean (undisturbed) flow Linear stability analysis Production (extracting energy from the mean flow to fluctuations) linear stability theory can predict when many flows become unstable, it can say very little about transition to turbulence since this progress is highly non-linear

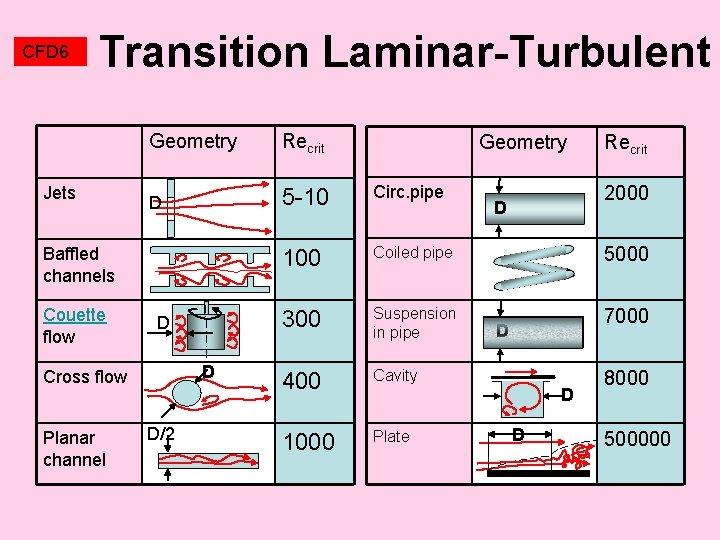

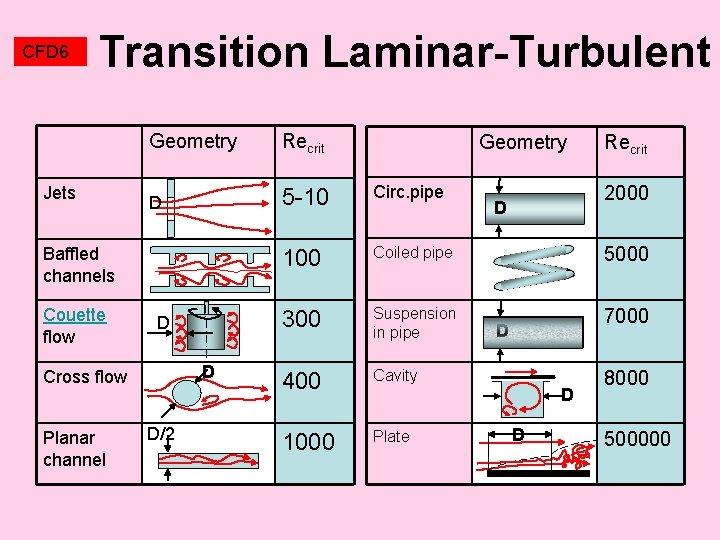

CFD 6 Transition Laminar-Turbulent Jets Geometry Recrit D 5 -10 Circ. pipe 100 Coiled pipe 5000 300 Suspension in pipe 7000 400 Cavity 1000 Plate Baffled channels Couette flow D D Cross flow Planar channel D/2 Geometry Recrit 2000 D D 8000 500000

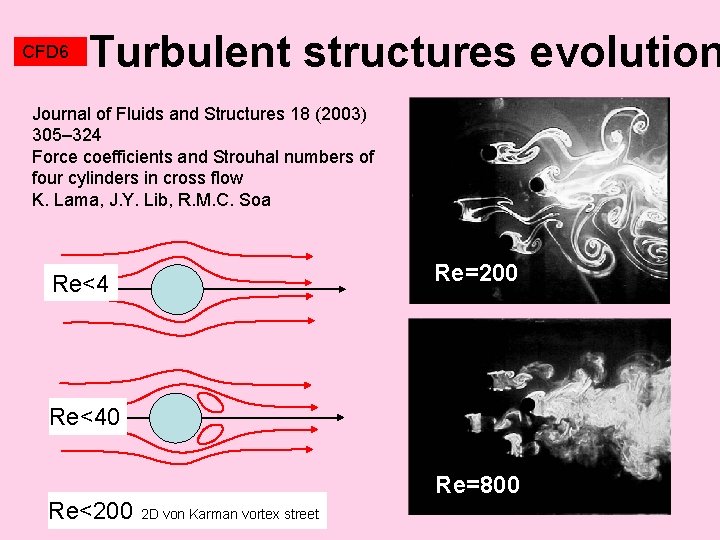

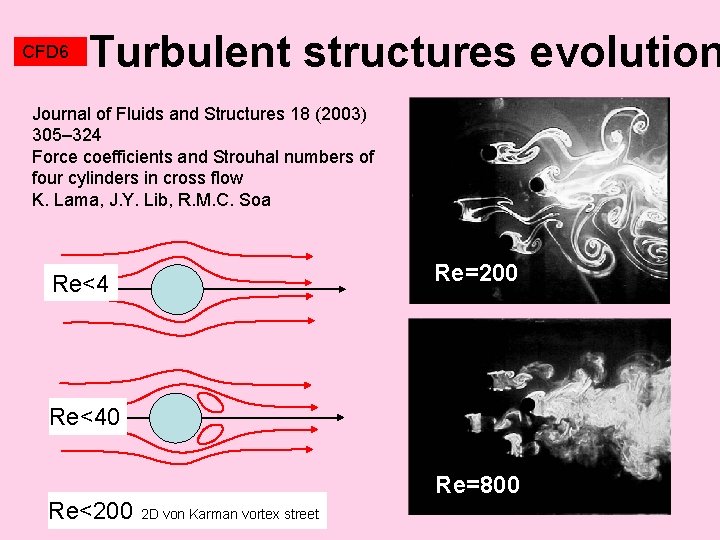

CFD 6 Turbulent structures evolution Journal of Fluids and Structures 18 (2003) 305– 324 Force coefficients and Strouhal numbers of four cylinders in cross flow K. Lama, J. Y. Lib, R. M. C. Soa Re<4 Re=200 Re<40 Re<200 2 D von Karman vortex street Re=800

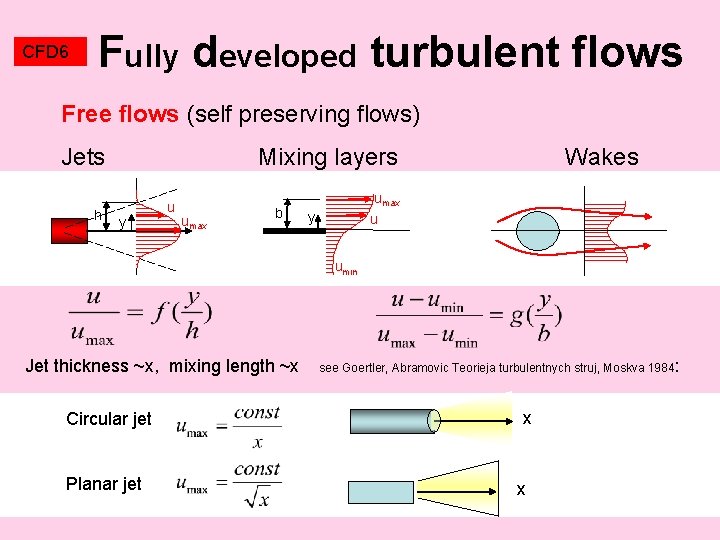

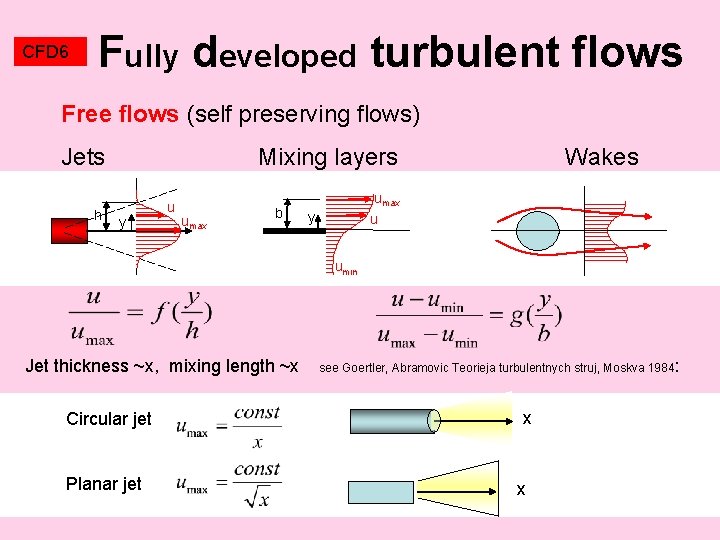

CFD 6 Fully developed turbulent flows Free flows (self preserving flows) Jets h Mixing layers y u umax b Wakes umax u y umin Jet thickness ~x, mixing length ~x see Goertler, Abramovic Teorieja turbulentnych struj, Moskva 1984: Circular jet Planar jet x x

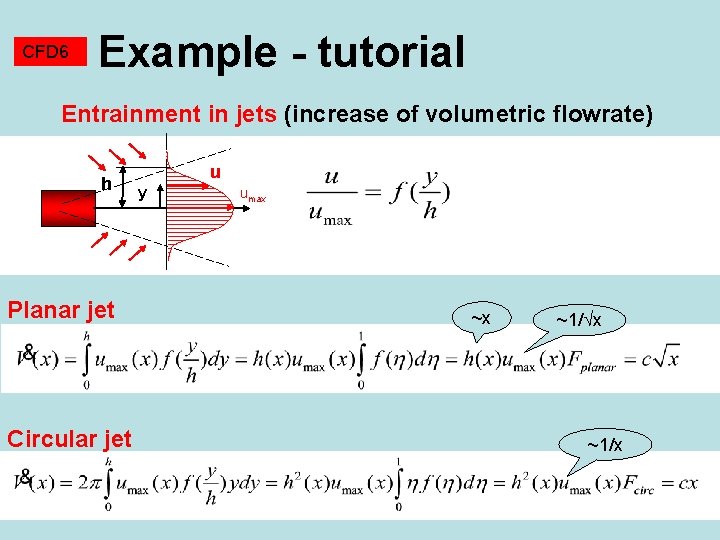

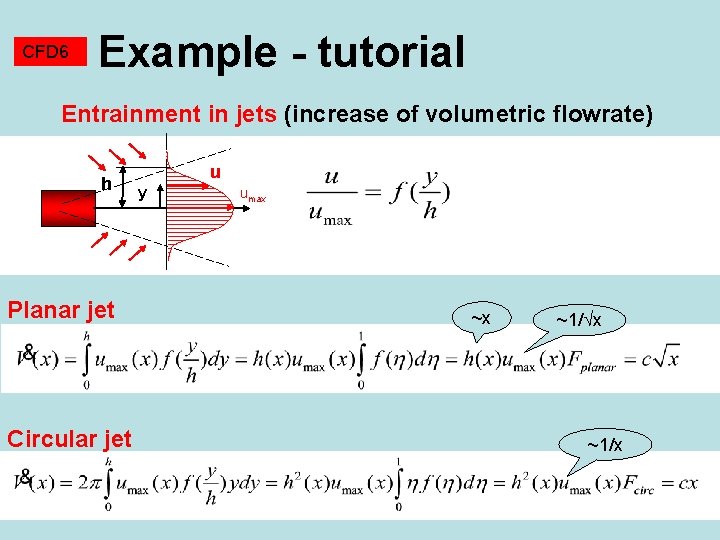

CFD 6 Example - tutorial Entrainment in jets (increase of volumetric flowrate) h Planar jet Circular jet u y umax ~x ~1/x

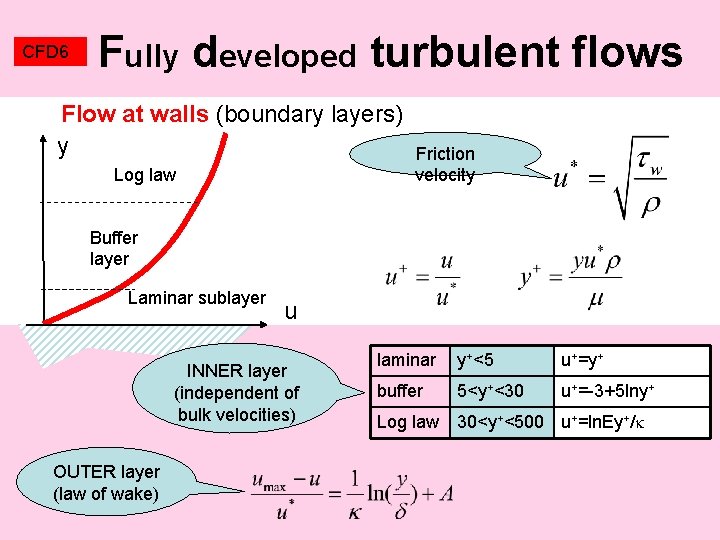

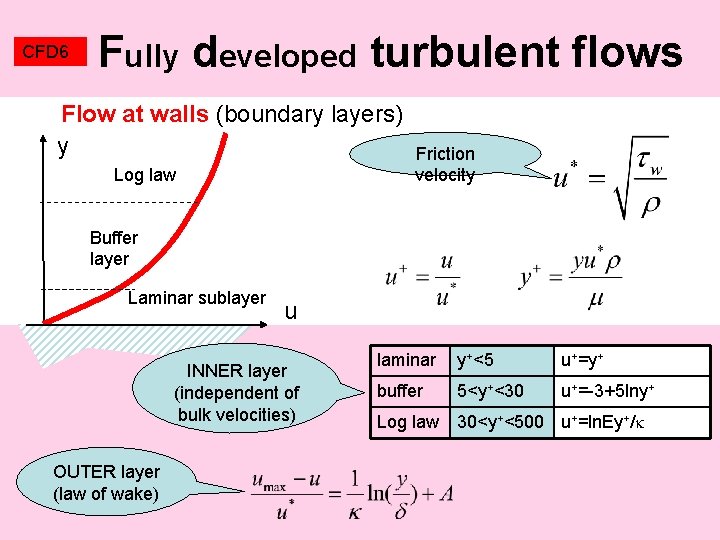

CFD 6 Fully developed turbulent flows Flow at walls (boundary layers) y Log law Friction velocity Buffer layer Laminar sublayer u INNER layer (independent of bulk velocities) OUTER layer (law of wake) laminar y+<5 u+=y+ buffer 5<y+<30 u+=-3+5 lny+ Log law 30<y+<500 u+=ln. Ey+/

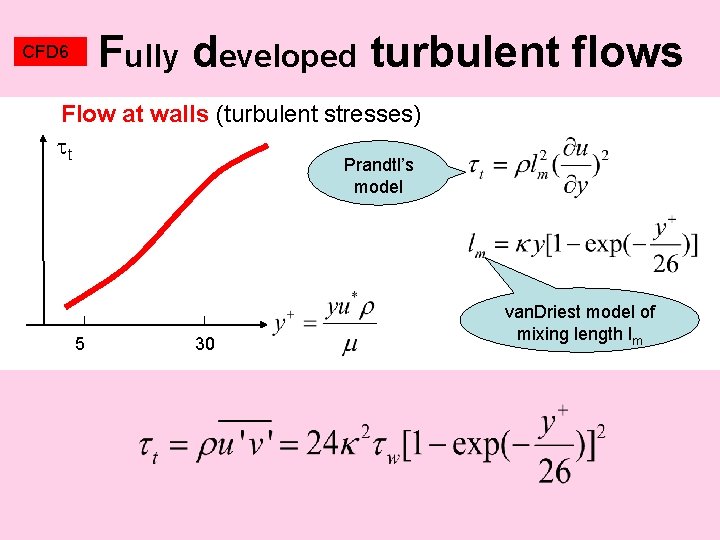

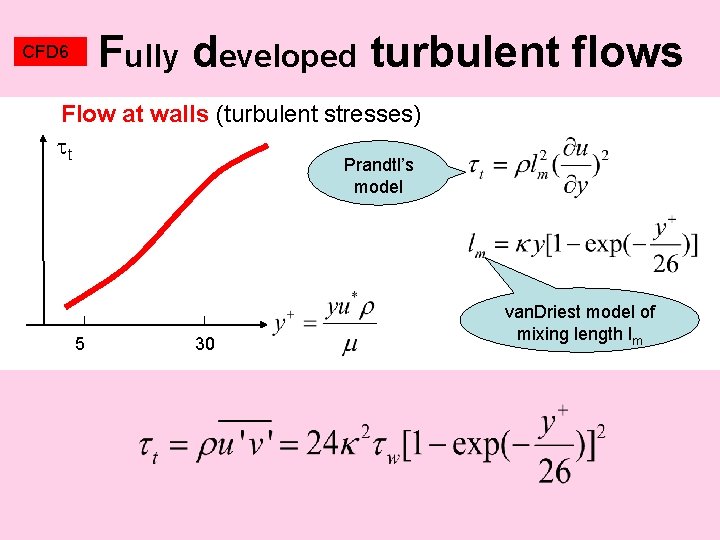

CFD 6 Fully developed turbulent flows Flow at walls (turbulent stresses) t Prandtl’s model 5 30 van. Driest model of mixing length lm

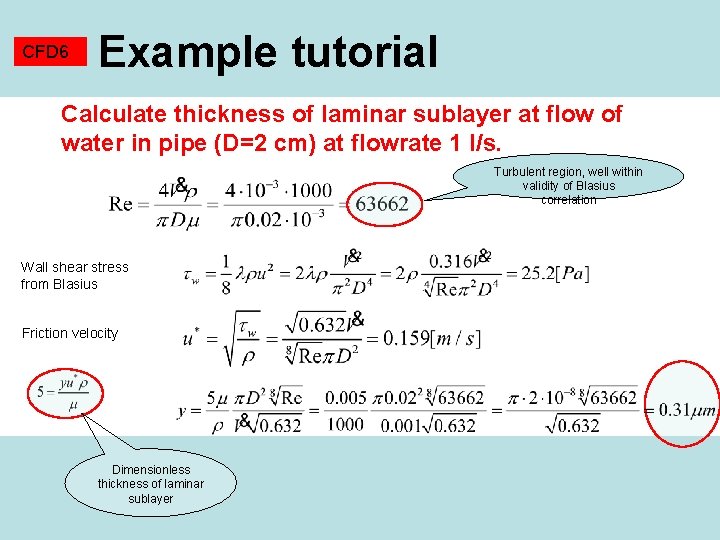

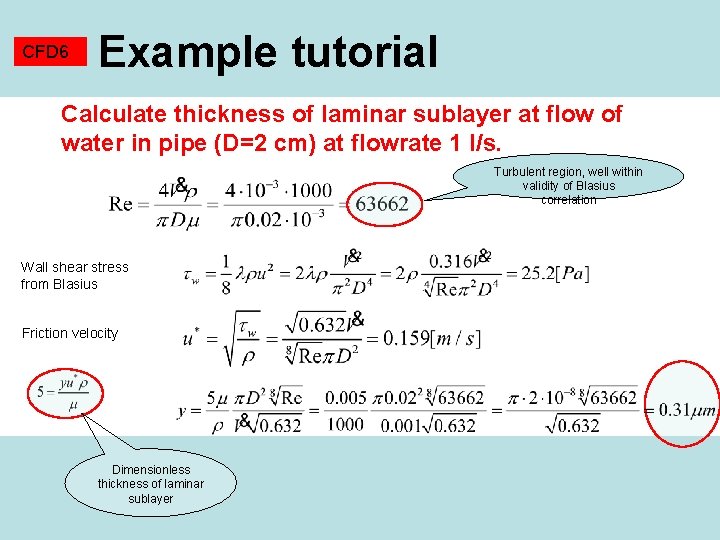

CFD 6 Example tutorial Calculate thickness of laminar sublayer at flow of water in pipe (D=2 cm) at flowrate 1 l/s. Turbulent region, well within validity of Blasius correlation Wall shear stress from Blasius Friction velocity Dimensionless thickness of laminar sublayer

CFD 6 TIME AVERAGING of turbulent fluctuations Benton

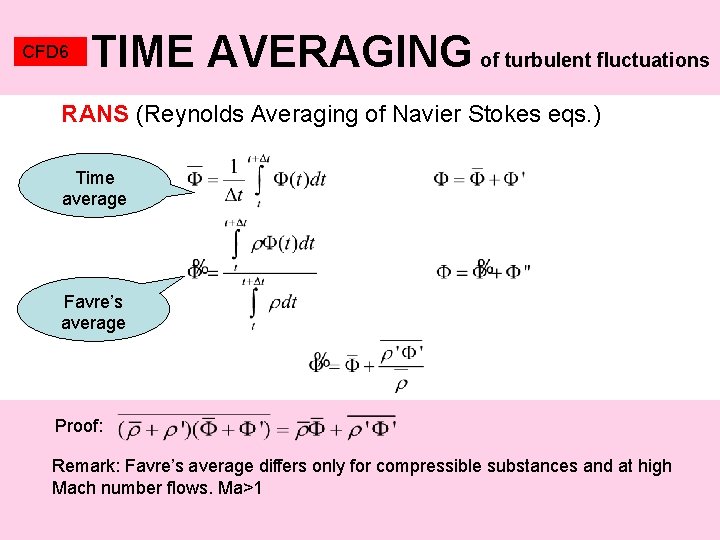

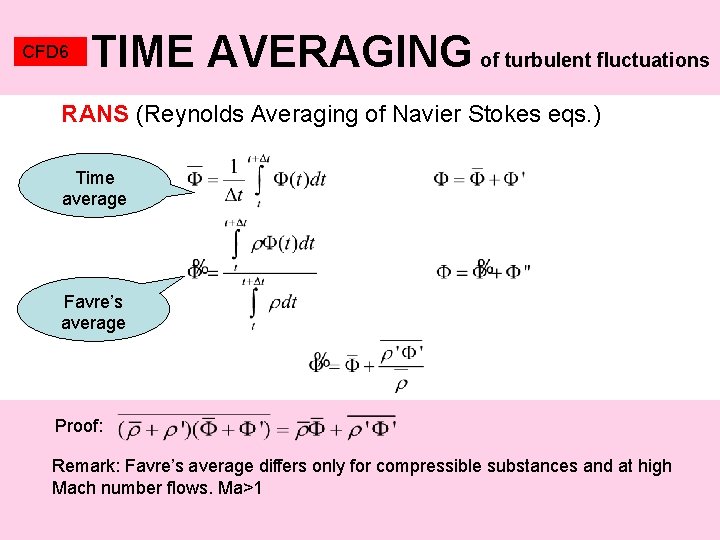

CFD 6 TIME AVERAGING of turbulent fluctuations RANS (Reynolds Averaging of Navier Stokes eqs. ) Time average Favre’s average Proof: Remark: Favre’s average differs only for compressible substances and at high Mach number flows. Ma>1

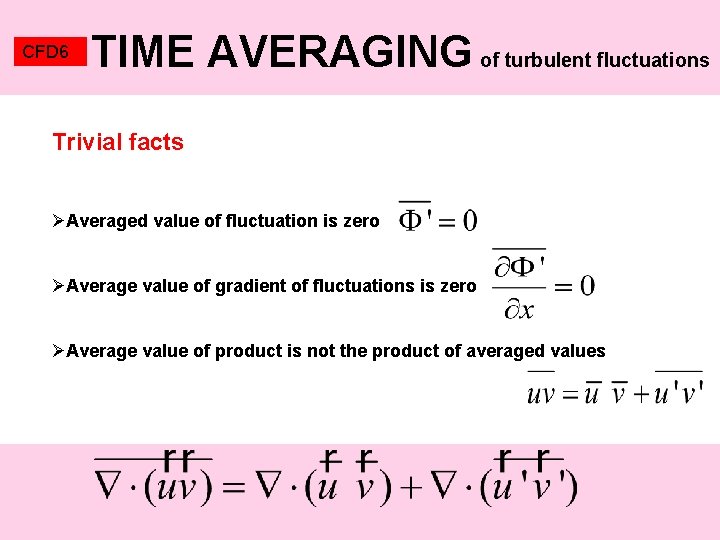

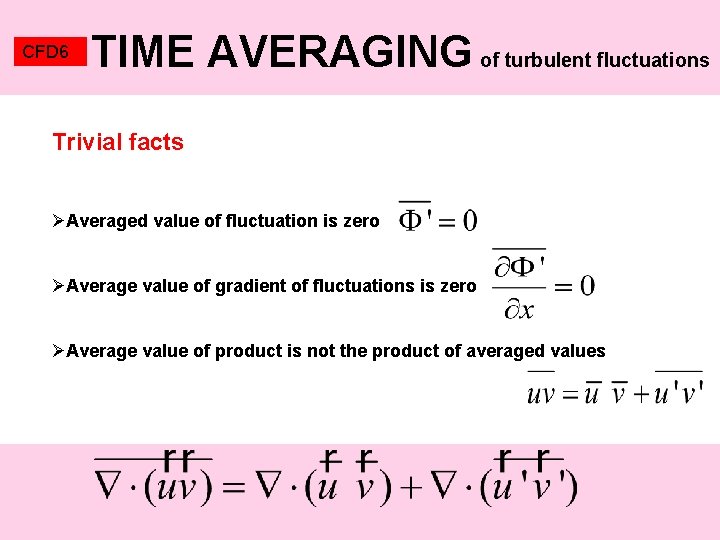

CFD 6 TIME AVERAGING of turbulent fluctuations Trivial facts ØAveraged value of fluctuation is zero ØAverage value of gradient of fluctuations is zero ØAverage value of product is not the product of averaged values

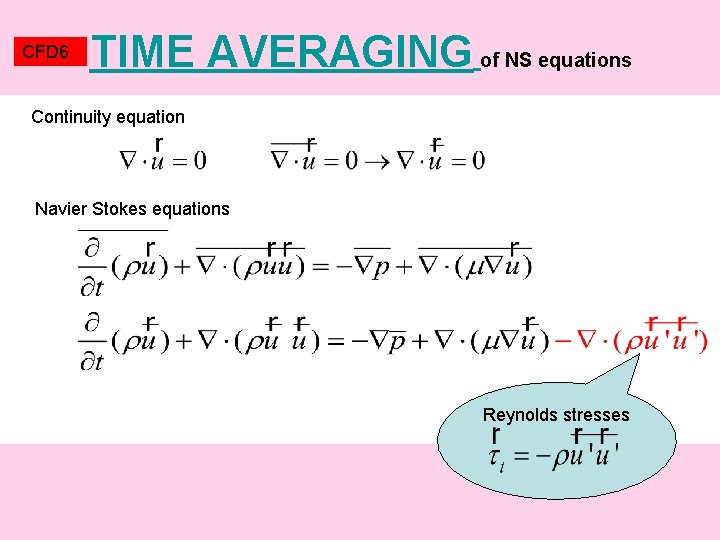

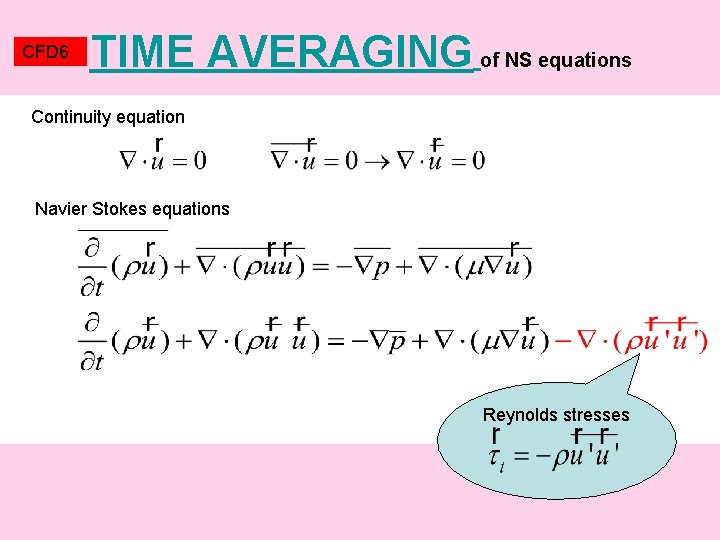

CFD 6 TIME AVERAGING of NS equations Continuity equation Navier Stokes equations Reynolds stresses

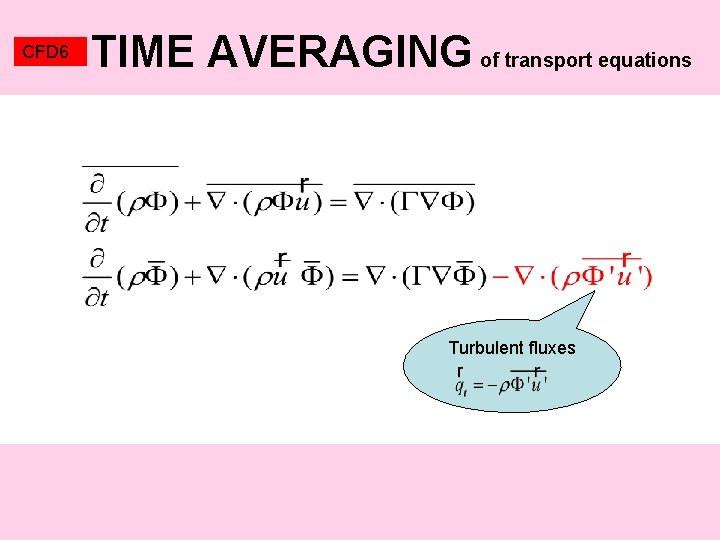

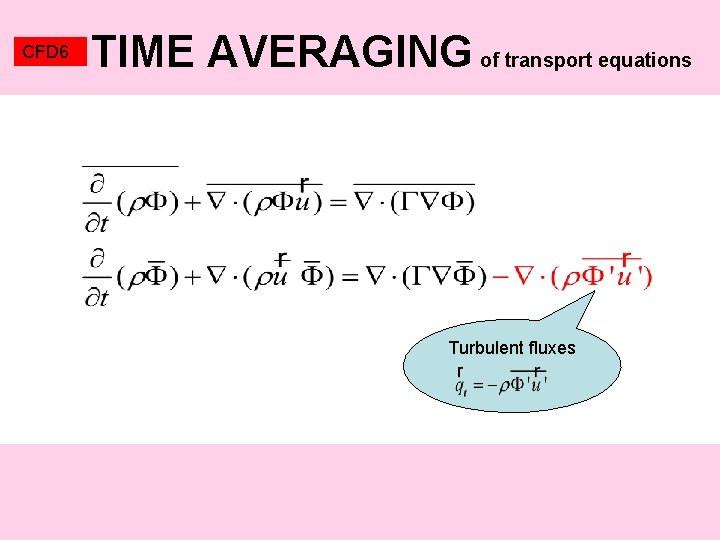

CFD 6 TIME AVERAGING of transport equations Turbulent fluxes

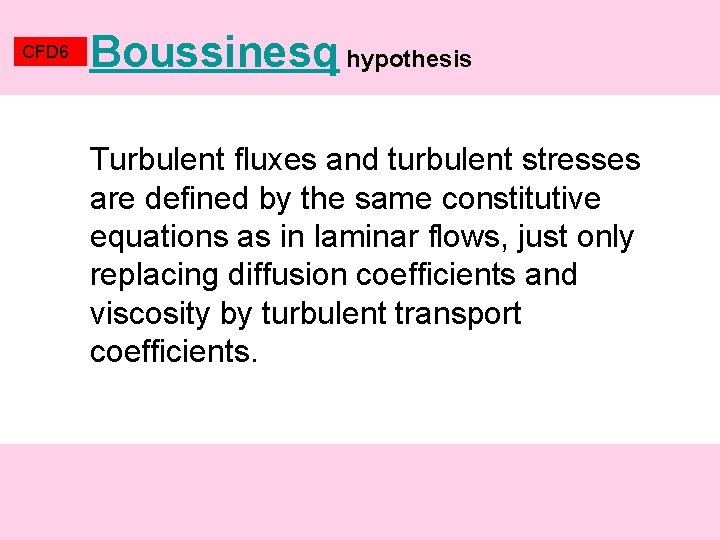

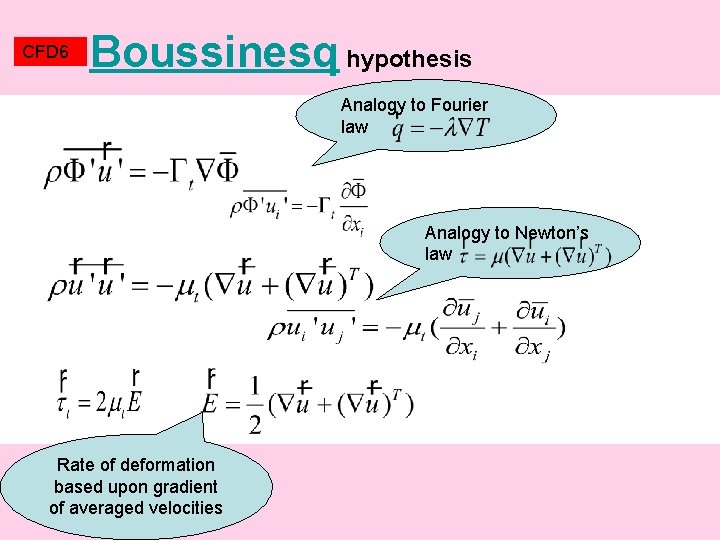

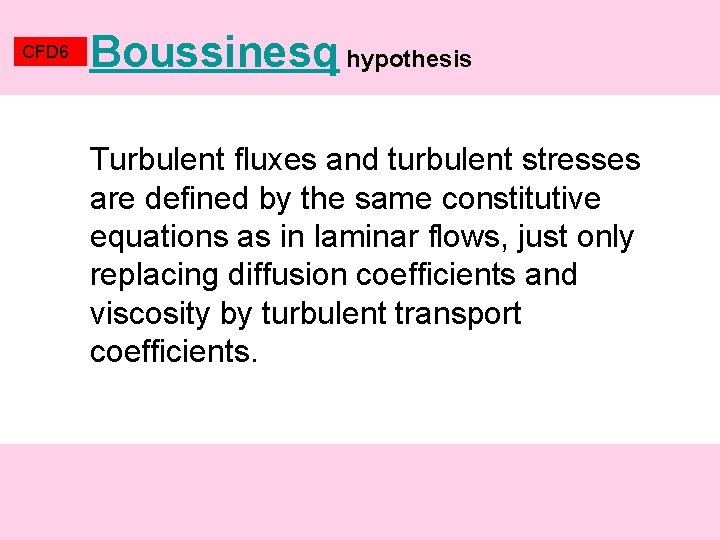

CFD 6 Boussinesq hypothesis Turbulent fluxes and turbulent stresses are defined by the same constitutive equations as in laminar flows, just only replacing diffusion coefficients and viscosity by turbulent transport coefficients.

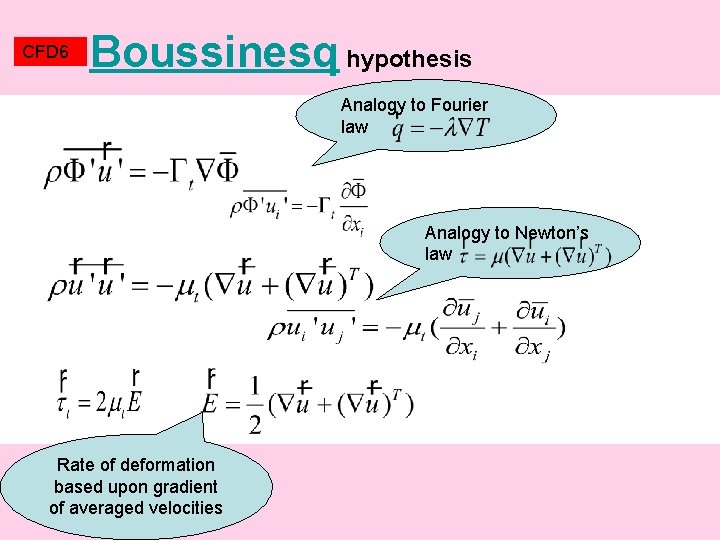

CFD 6 Boussinesq hypothesis Analogy to Fourier law Analogy to Newton’s law Rate of deformation based upon gradient of averaged velocities

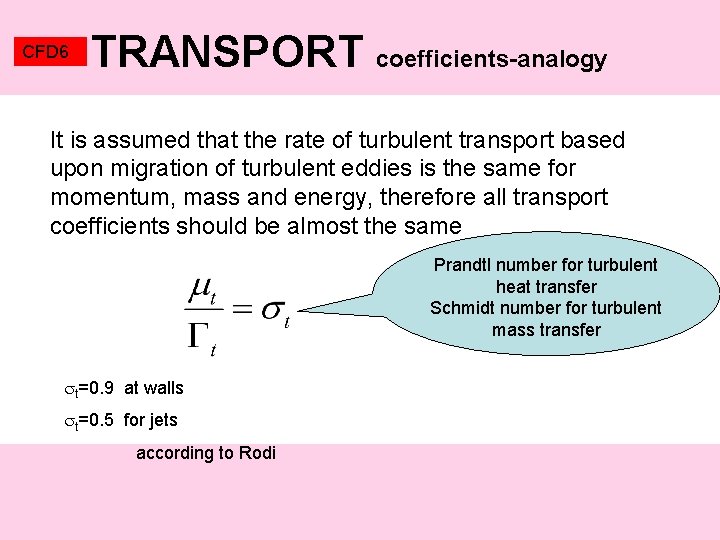

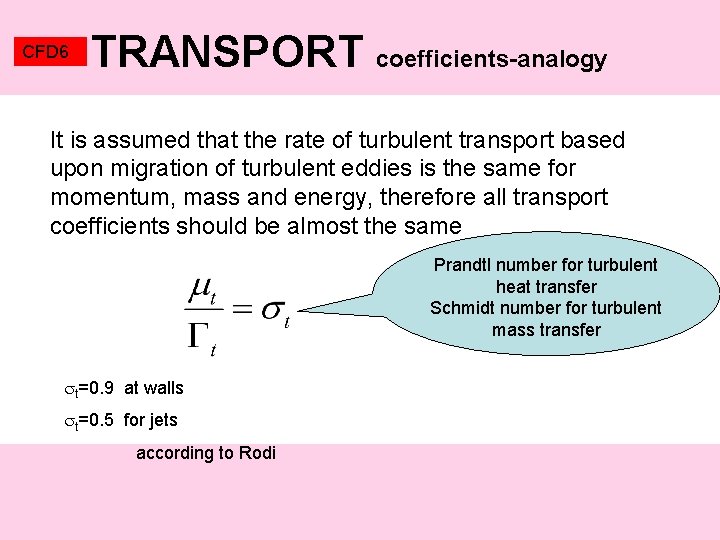

CFD 6 TRANSPORT coefficients-analogy It is assumed that the rate of turbulent transport based upon migration of turbulent eddies is the same for momentum, mass and energy, therefore all transport coefficients should be almost the same Prandtl number for turbulent heat transfer Schmidt number for turbulent mass transfer t=0. 9 at walls t=0. 5 for jets according to Rodi

CFD 6 Turbulent viscosity models Botero

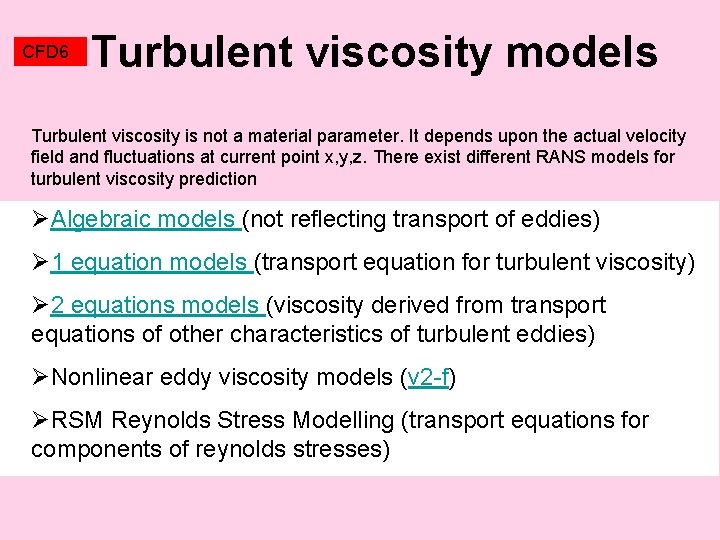

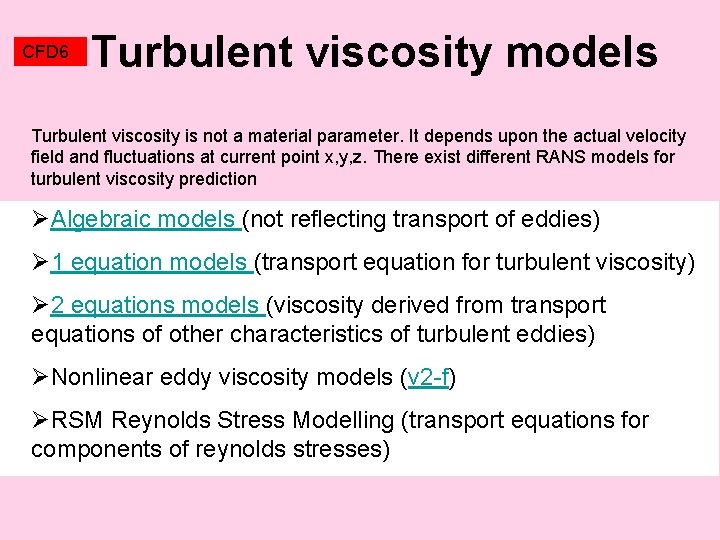

CFD 6 Turbulent viscosity models Turbulent viscosity is not a material parameter. It depends upon the actual velocity field and fluctuations at current point x, y, z. There exist different RANS models for turbulent viscosity prediction ØAlgebraic models (not reflecting transport of eddies) Ø 1 equation models (transport equation for turbulent viscosity) Ø 2 equations models (viscosity derived from transport equations of other characteristics of turbulent eddies) ØNonlinear eddy viscosity models (v 2 -f) ØRSM Reynolds Stress Modelling (transport equations for components of reynolds stresses)

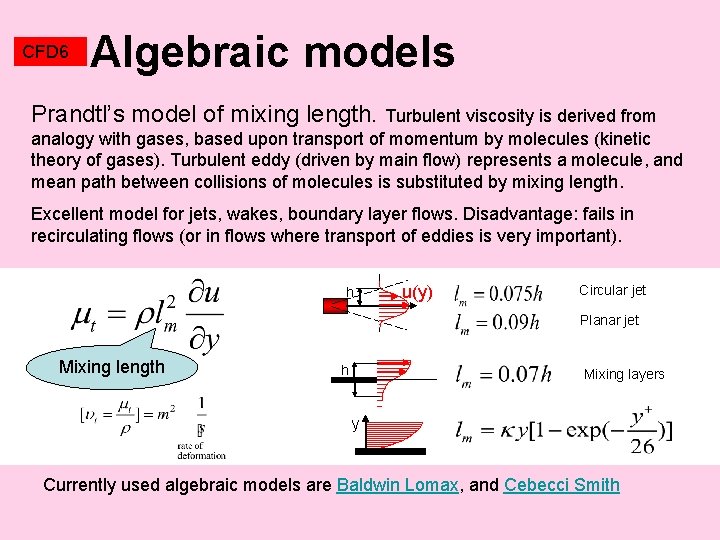

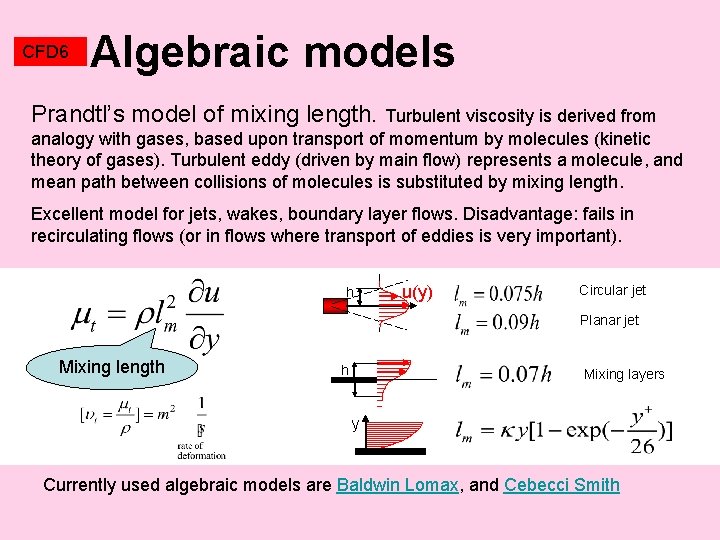

CFD 6 Algebraic models Prandtl’s model of mixing length. Turbulent viscosity is derived from analogy with gases, based upon transport of momentum by molecules (kinetic theory of gases). Turbulent eddy (driven by main flow) represents a molecule, and mean path between collisions of molecules is substituted by mixing length. Excellent model for jets, wakes, boundary layer flows. Disadvantage: fails in recirculating flows (or in flows where transport of eddies is very important). h u(y) Circular jet Planar jet Mixing length h Mixing layers y Currently used algebraic models are Baldwin Lomax, and Cebecci Smith

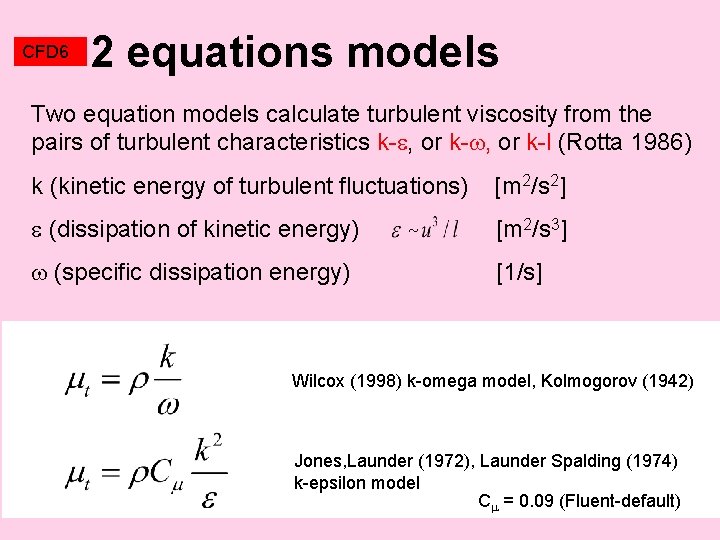

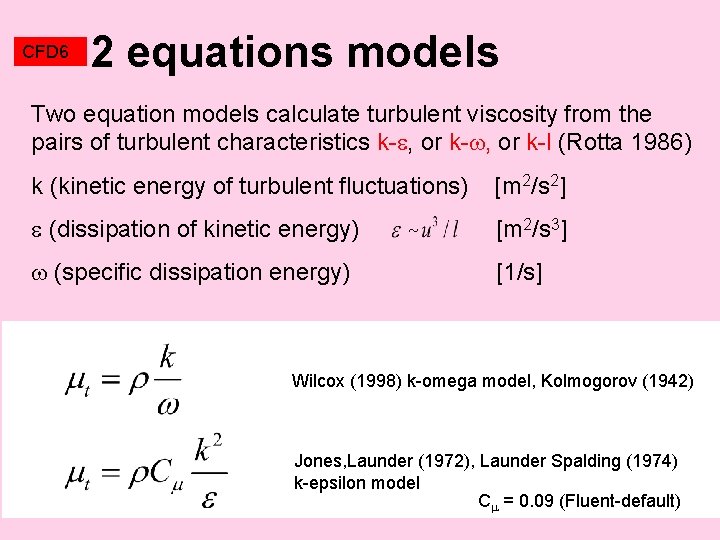

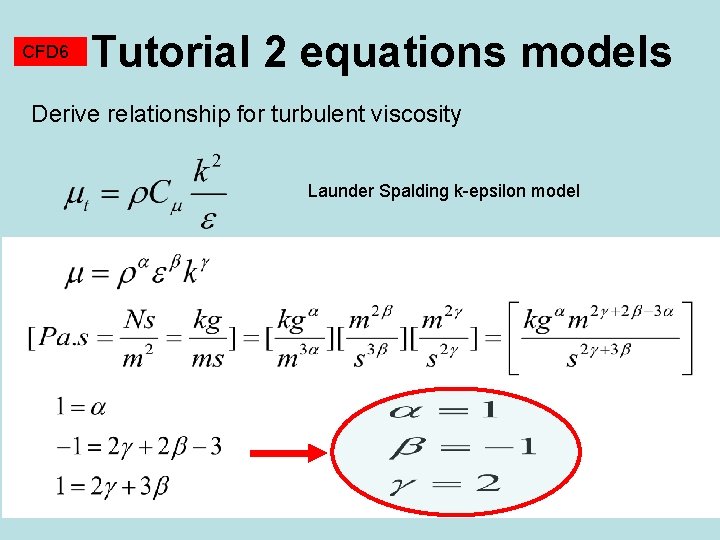

CFD 6 2 equations models Two equation models calculate turbulent viscosity from the pairs of turbulent characteristics k- , or k-l (Rotta 1986) k (kinetic energy of turbulent fluctuations) [m 2/s 2] (dissipation of kinetic energy) [m 2/s 3] (specific dissipation energy) [1/s] Wilcox (1998) k-omega model, Kolmogorov (1942) Jones, Launder (1972), Launder Spalding (1974) k-epsilon model C = 0. 09 (Fluent-default)

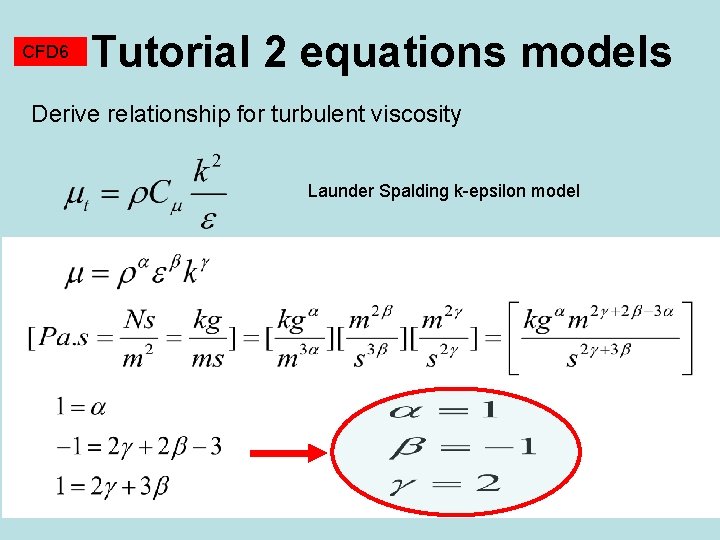

CFD 6 Tutorial 2 equations models Derive relationship for turbulent viscosity Launder Spalding k-epsilon model

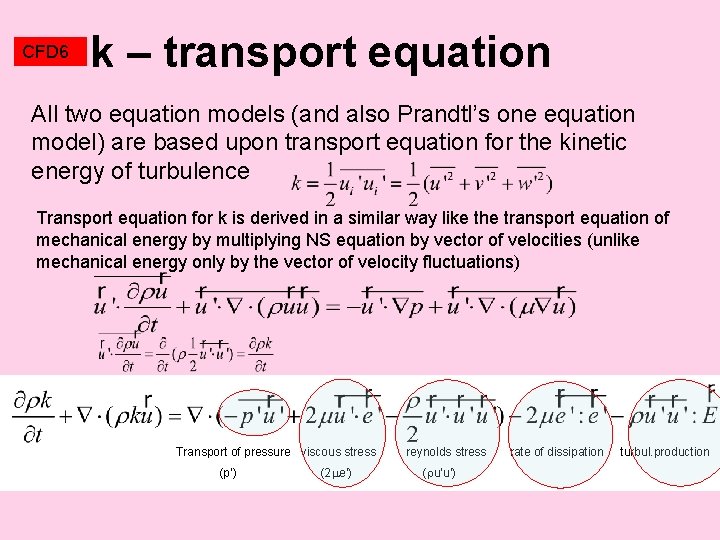

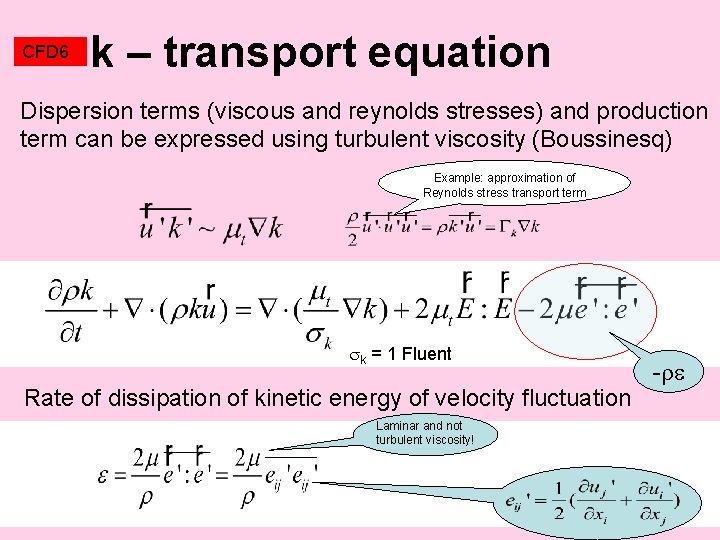

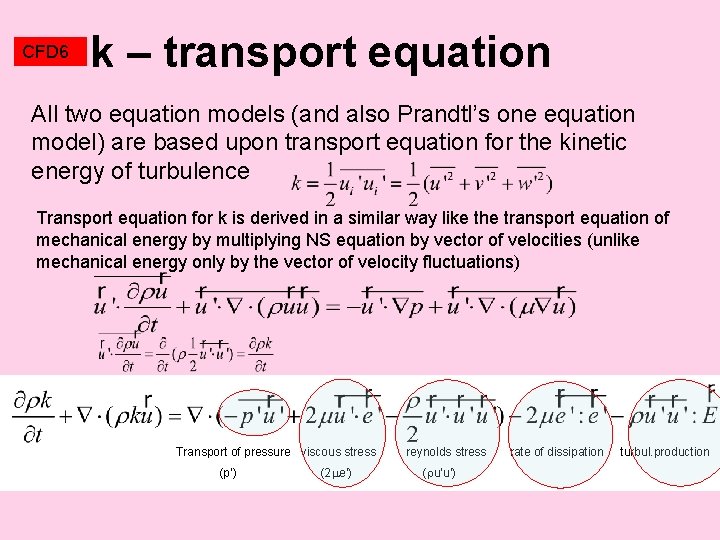

CFD 6 k – transport equation All two equation models (and also Prandtl’s one equation model) are based upon transport equation for the kinetic energy of turbulence Transport equation for k is derived in a similar way like the transport equation of mechanical energy by multiplying NS equation by vector of velocities (unlike mechanical energy only by the vector of velocity fluctuations) Transport of pressure viscous stress reynolds stress rate of dissipation turbul. production (p’) (2 e’) ( u’u’)

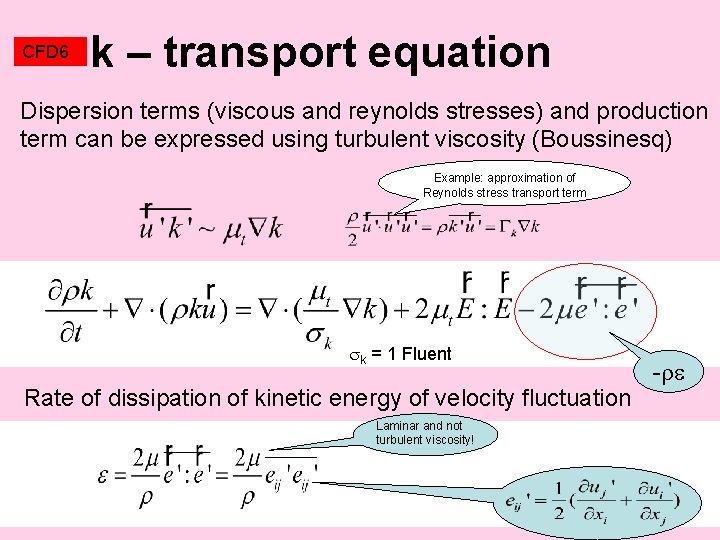

CFD 6 k – transport equation Dispersion terms (viscous and reynolds stresses) and production term can be expressed using turbulent viscosity (Boussinesq) Example: approximation of Reynolds stress transport term k = 1 Fluent Rate of dissipation of kinetic energy of velocity fluctuation Laminar and not turbulent viscosity! -

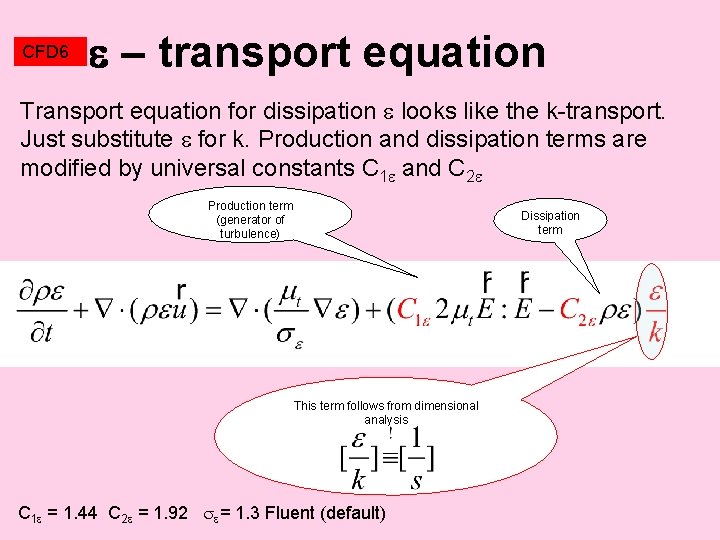

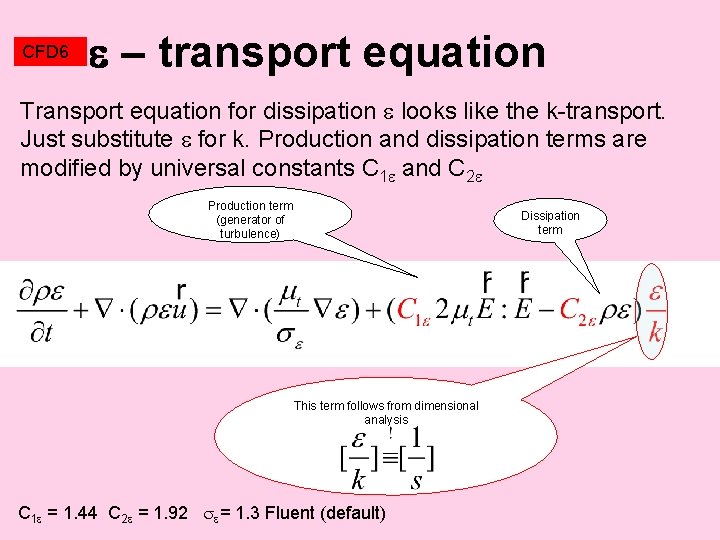

CFD 6 – transport equation Transport equation for dissipation looks like the k-transport. Just substitute for k. Production and dissipation terms are modified by universal constants C 1 and C 2 Production term (generator of turbulence) This term follows from dimensional analysis C 1 = 1. 44 C 2 = 1. 92 = 1. 3 Fluent (default) Dissipation term

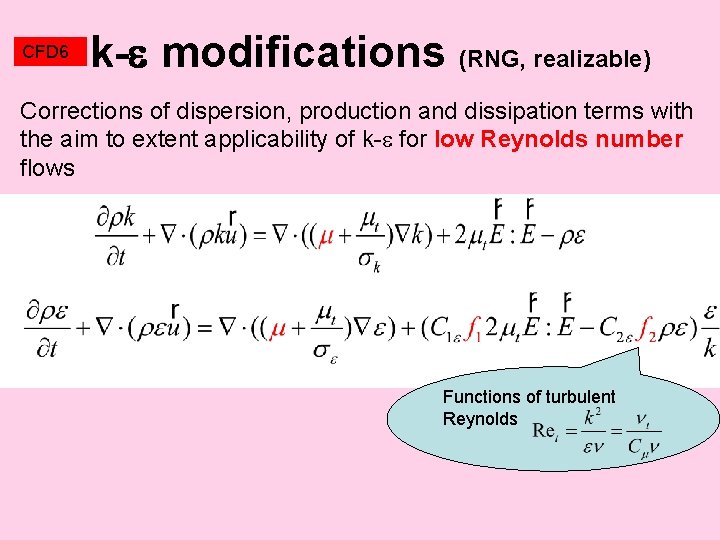

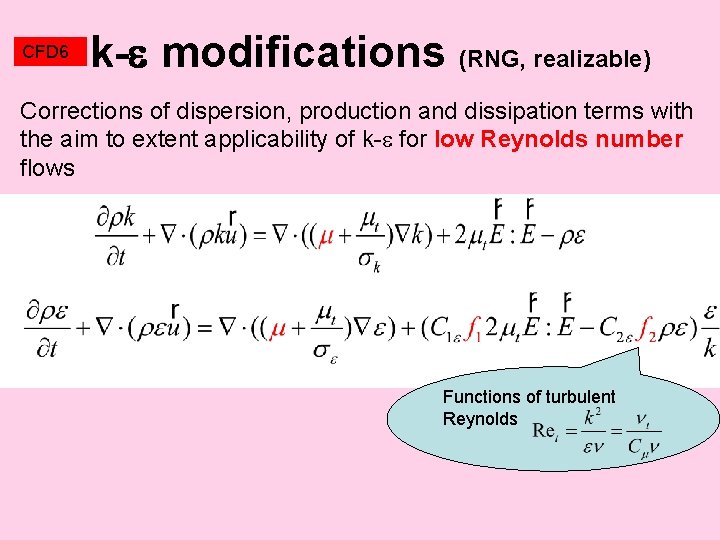

CFD 6 k- modifications (RNG, realizable) Corrections of dispersion, production and dissipation terms with the aim to extent applicability of k- for low Reynolds number flows Functions of turbulent Reynolds

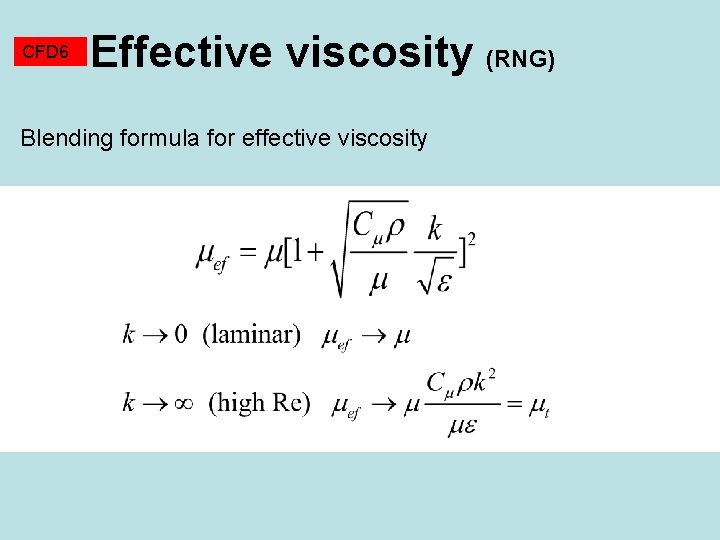

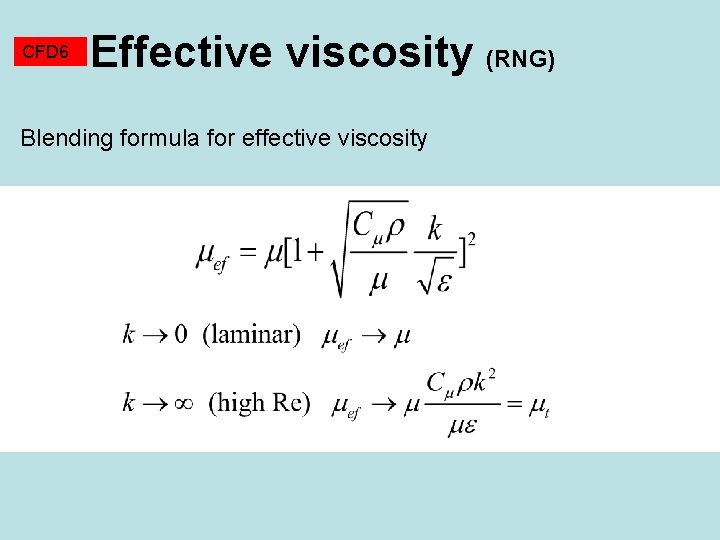

CFD 6 Effective viscosity (RNG) Blending formula for effective viscosity

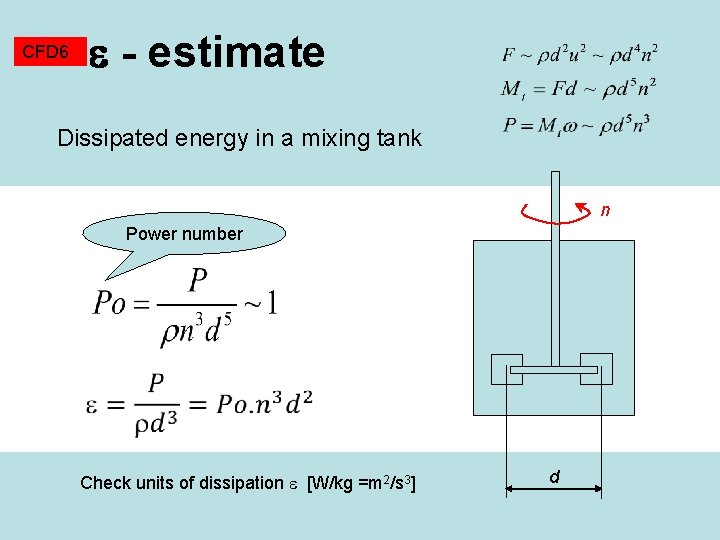

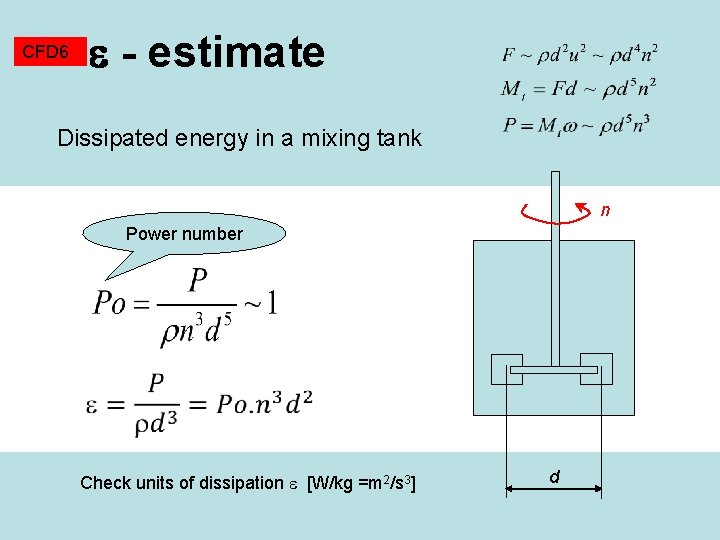

CFD 6 - estimate Dissipated energy in a mixing tank n Power number Check units of dissipation [W/kg =m 2/s 3] d

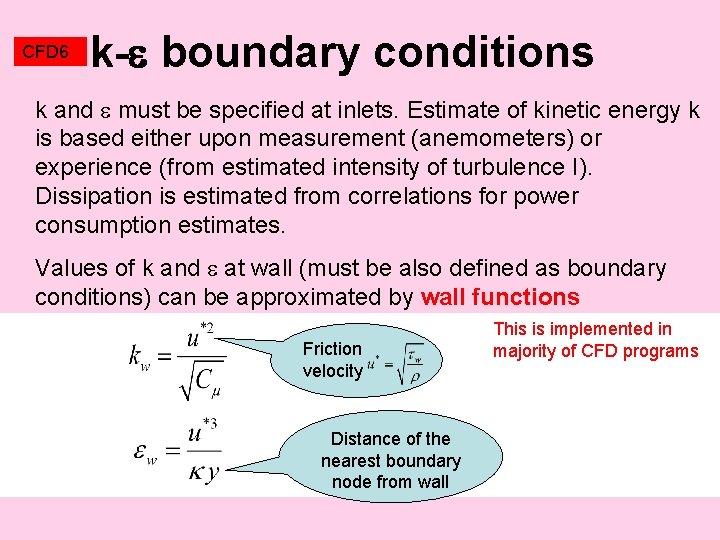

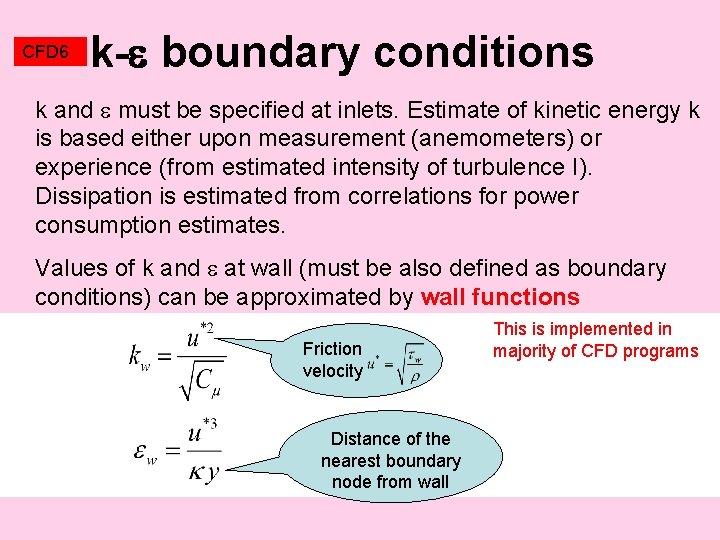

CFD 6 k- boundary conditions k and must be specified at inlets. Estimate of kinetic energy k is based either upon measurement (anemometers) or experience (from estimated intensity of turbulence I). Dissipation is estimated from correlations for power consumption estimates. Values of k and at wall (must be also defined as boundary conditions) can be approximated by wall functions Friction velocity Distance of the nearest boundary node from wall This is implemented in majority of CFD programs

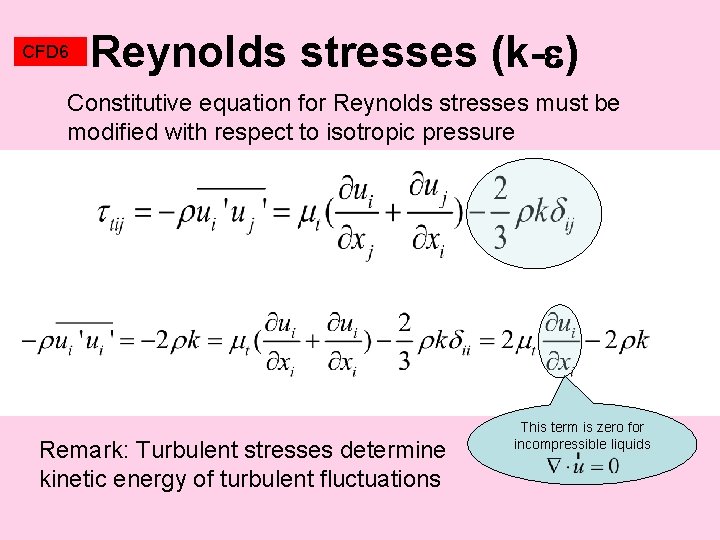

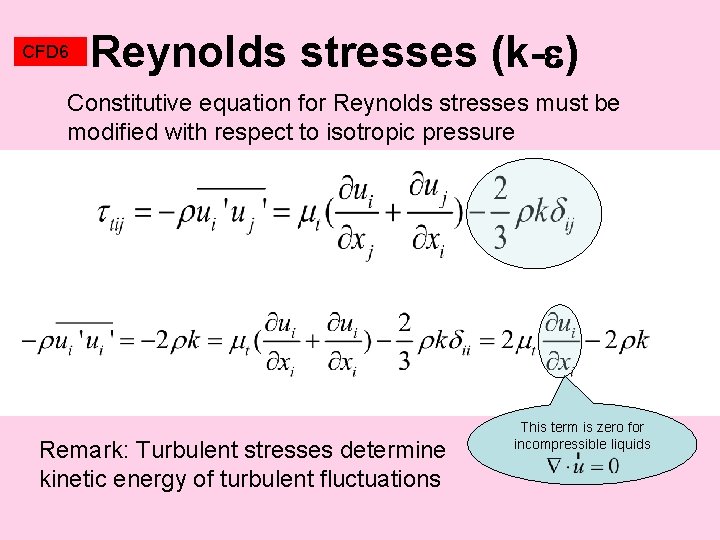

CFD 6 Reynolds stresses (k- ) Constitutive equation for Reynolds stresses must be modified with respect to isotropic pressure Remark: Turbulent stresses determine kinetic energy of turbulent fluctuations This term is zero for incompressible liquids

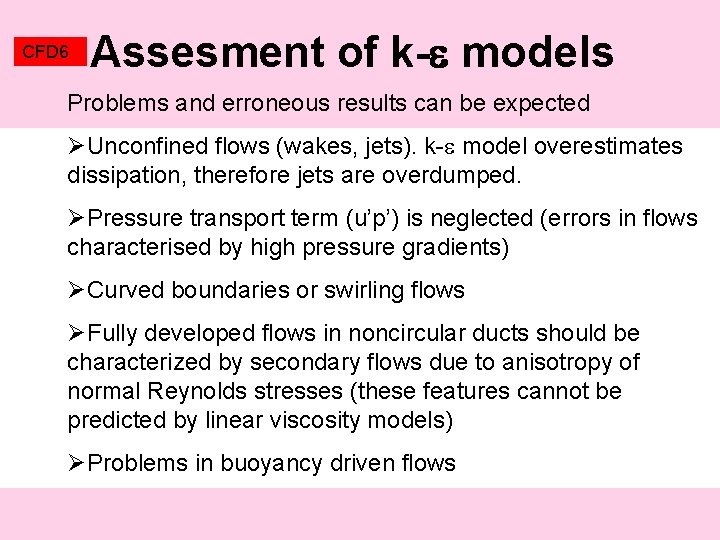

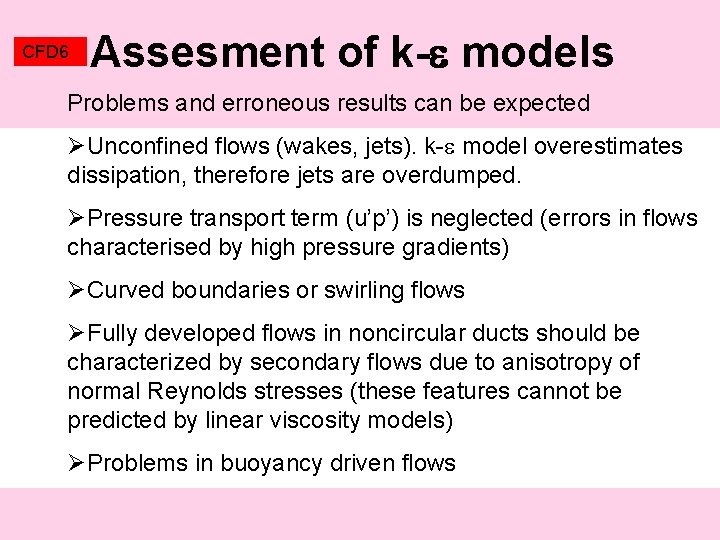

CFD 6 Assesment of k- models Problems and erroneous results can be expected ØUnconfined flows (wakes, jets). k- model overestimates dissipation, therefore jets are overdumped. ØPressure transport term (u’p’) is neglected (errors in flows characterised by high pressure gradients) ØCurved boundaries or swirling flows ØFully developed flows in noncircular ducts should be characterized by secondary flows due to anisotropy of normal Reynolds stresses (these features cannot be predicted by linear viscosity models) ØProblems in buoyancy driven flows

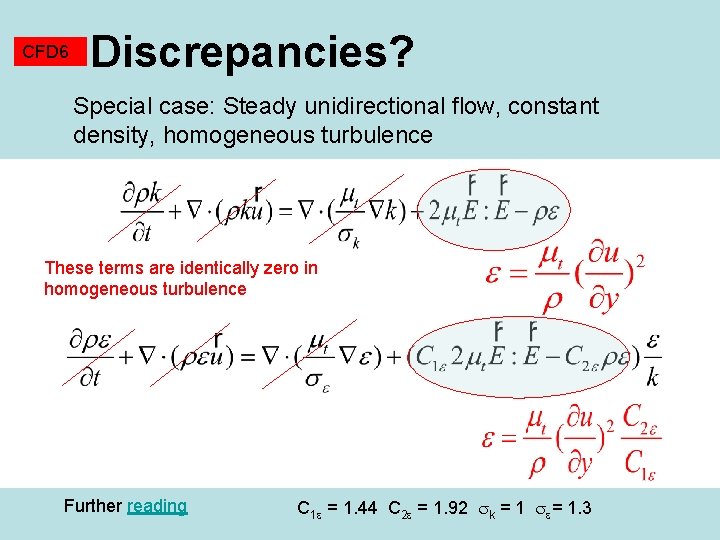

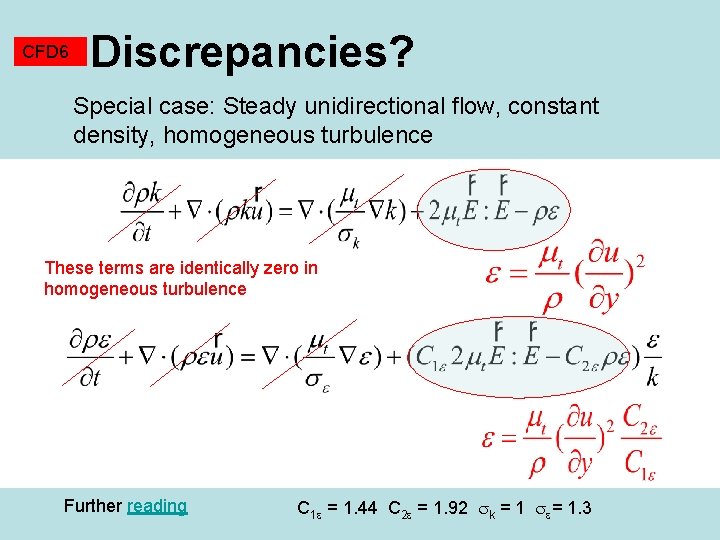

CFD 6 Discrepancies? Special case: Steady unidirectional flow, constant density, homogeneous turbulence These terms are identically zero in homogeneous turbulence Further reading C 1 = 1. 44 C 2 = 1. 92 k = 1. 3

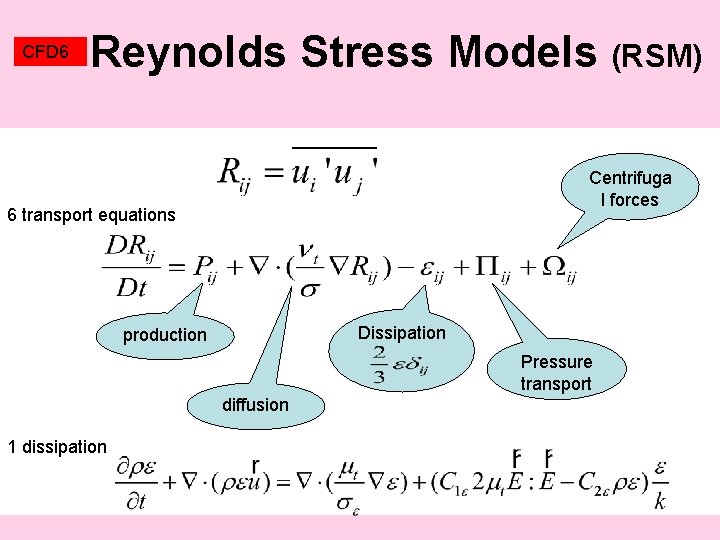

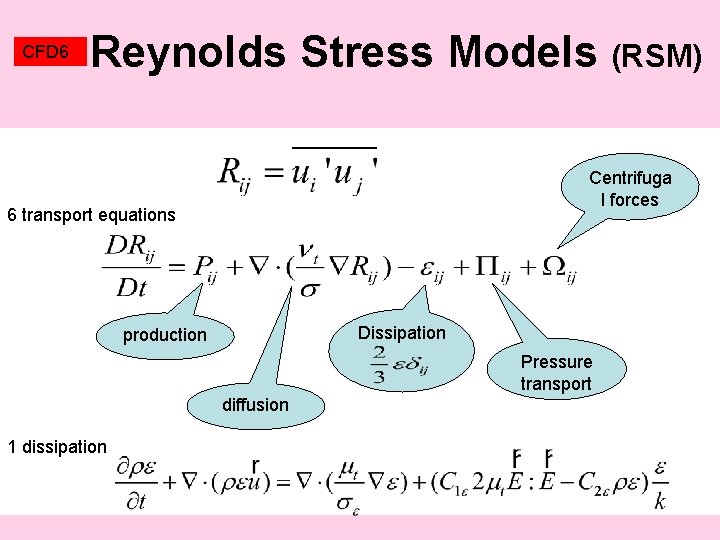

CFD 6 Reynolds Stress Models (RSM) Centrifuga l forces 6 transport equations Dissipation production Pressure transport diffusion 1 dissipation

CFD 6 Large Eddy Simulation (LES) Demuth

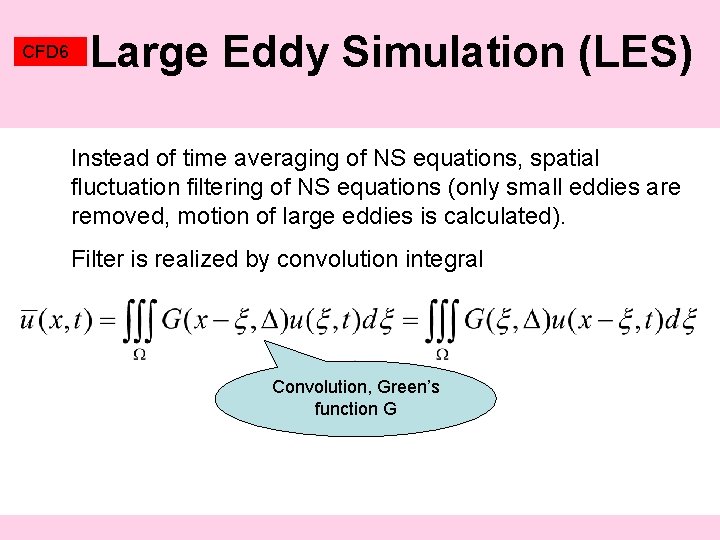

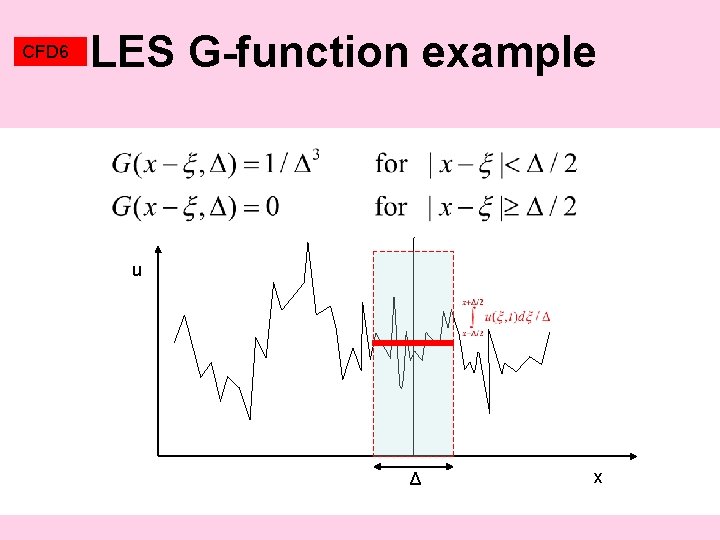

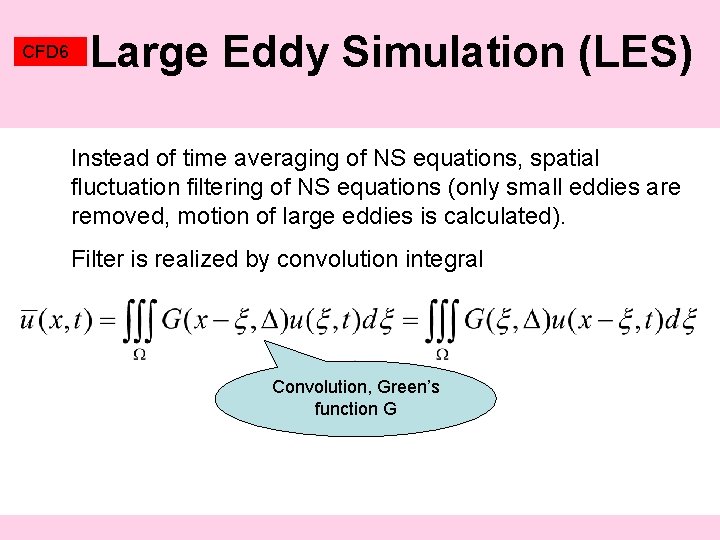

CFD 6 Large Eddy Simulation (LES) Instead of time averaging of NS equations, spatial fluctuation filtering of NS equations (only small eddies are removed, motion of large eddies is calculated). Filter is realized by convolution integral Convolution, Green’s function G

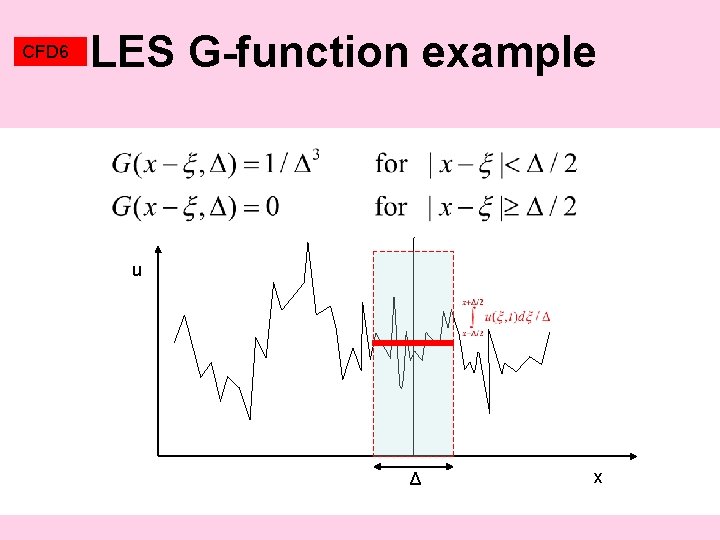

CFD 6 LES G-function example u Δ x

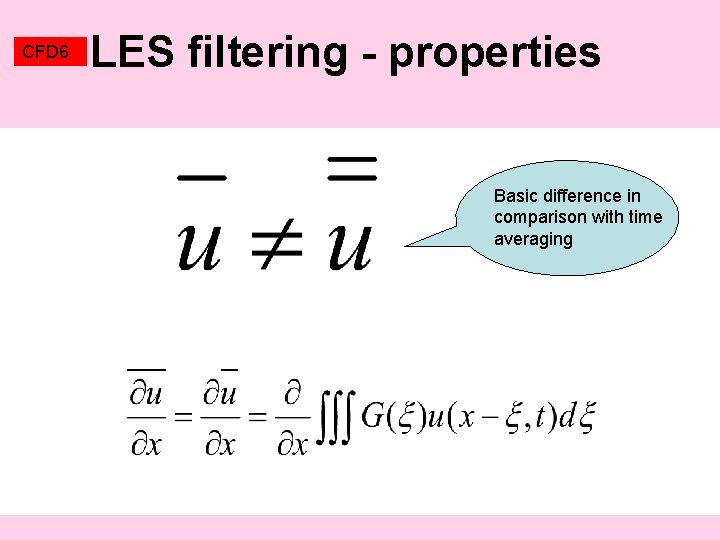

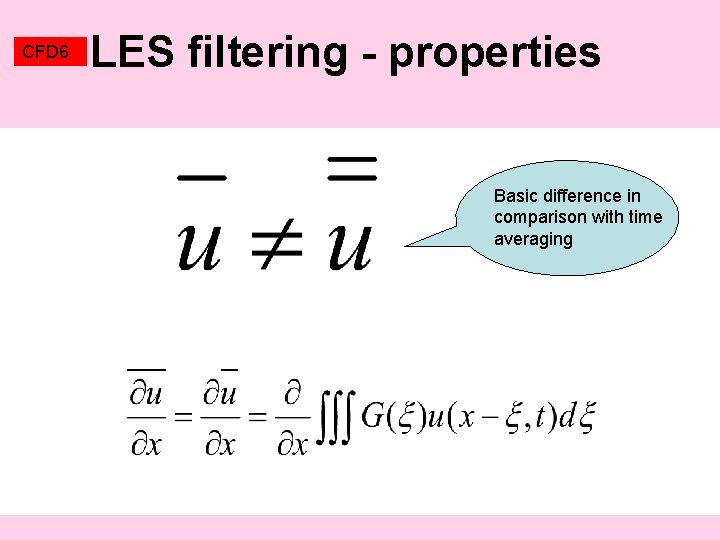

CFD 6 LES filtering - properties Basic difference in comparison with time averaging

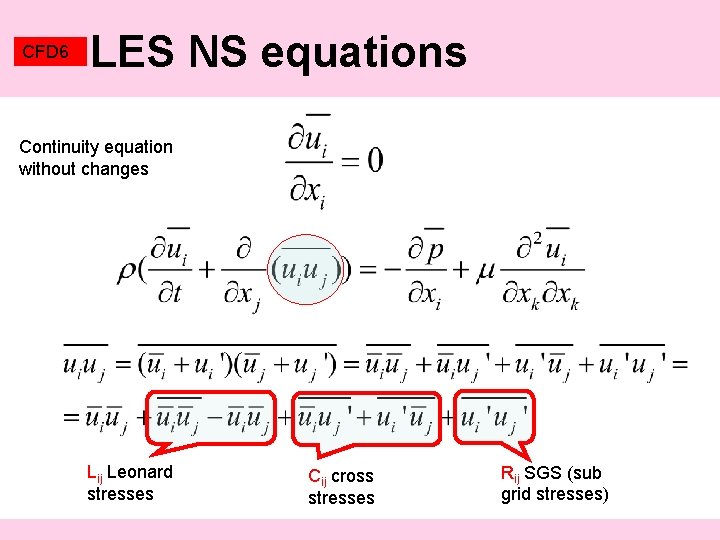

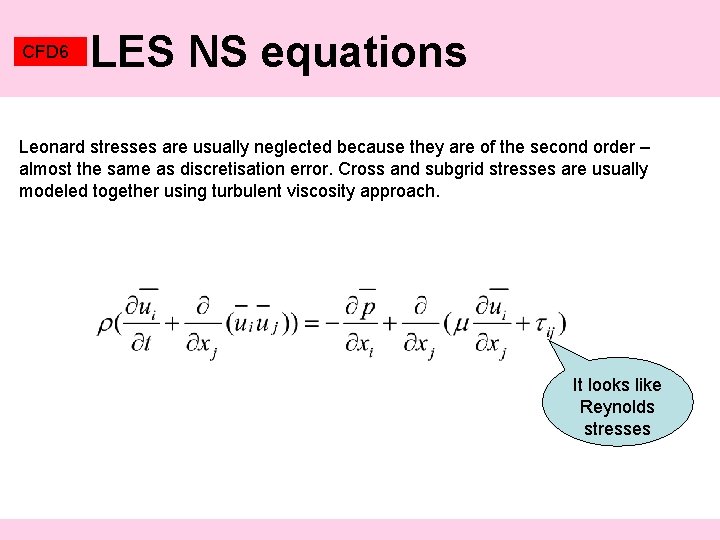

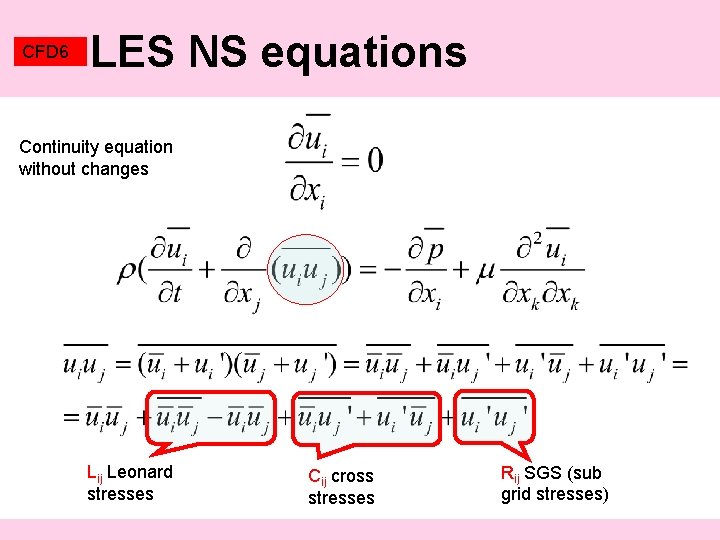

CFD 6 LES NS equations Continuity equation without changes Lij Leonard stresses Cij cross stresses Rij SGS (sub grid stresses)

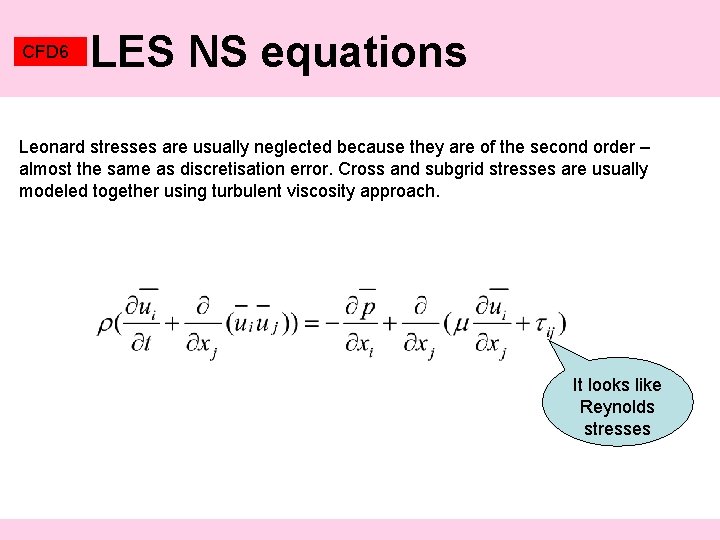

CFD 6 LES NS equations Leonard stresses are usually neglected because they are of the second order – almost the same as discretisation error. Cross and subgrid stresses are usually modeled together using turbulent viscosity approach. It looks like Reynolds stresses

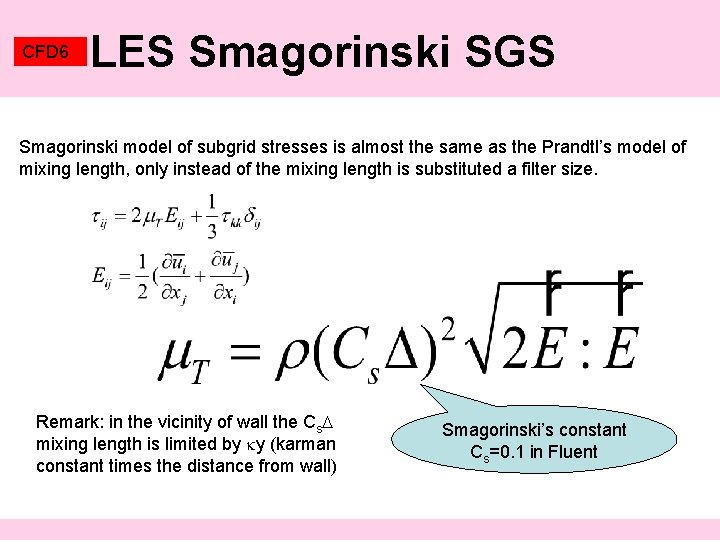

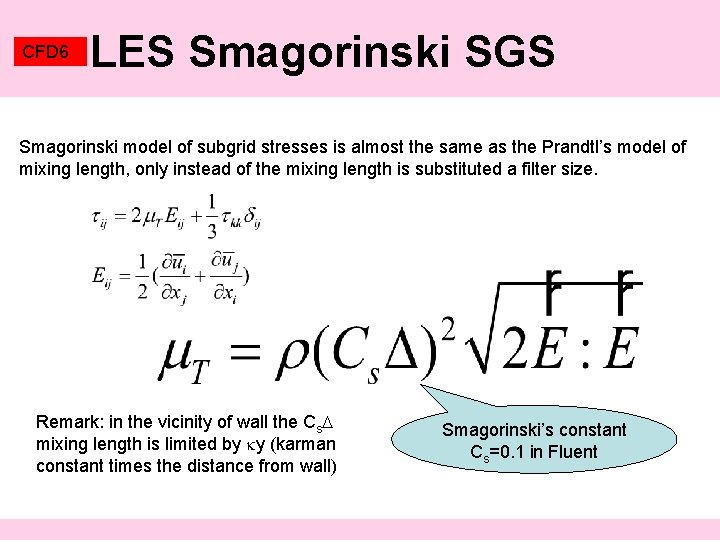

CFD 6 LES Smagorinski SGS Smagorinski model of subgrid stresses is almost the same as the Prandtl’s model of mixing length, only instead of the mixing length is substituted a filter size. Remark: in the vicinity of wall the Cs mixing length is limited by y (karman constant times the distance from wall) Smagorinski’s constant Cs=0. 1 in Fluent

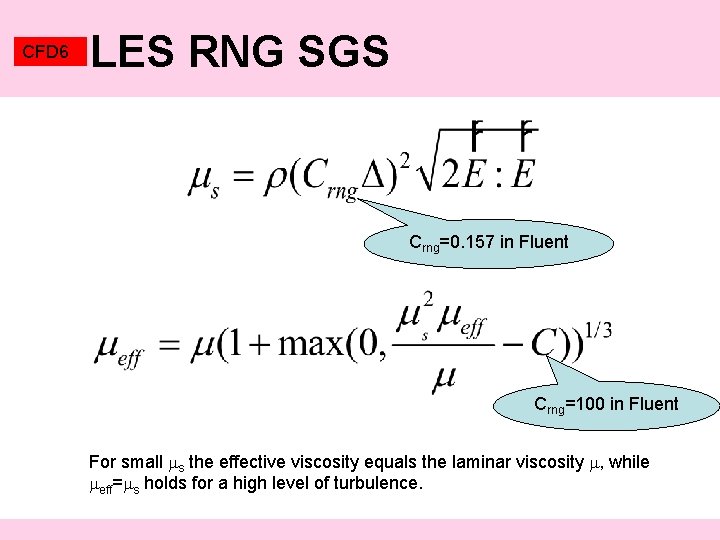

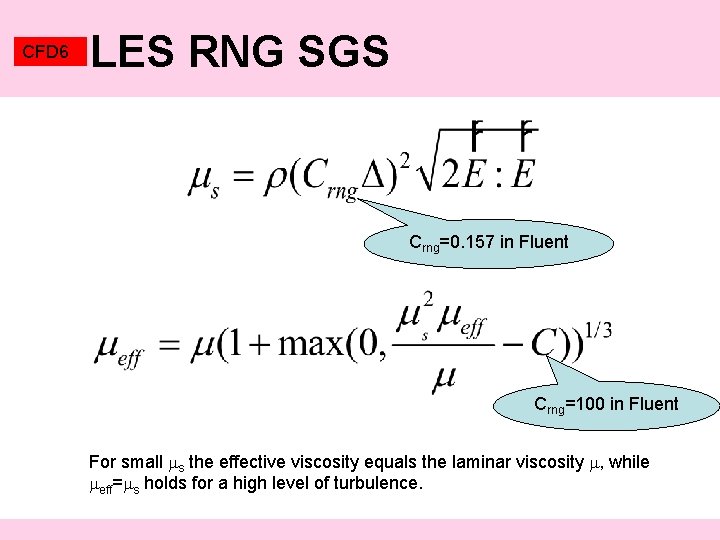

CFD 6 LES RNG SGS Crng=0. 157 in Fluent Crng=100 in Fluent For small s the effective viscosity equals the laminar viscosity , while eff= s holds for a high level of turbulence.

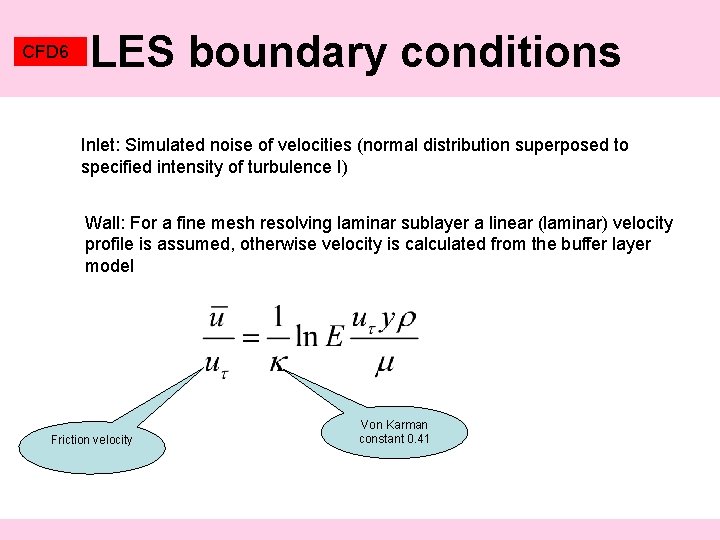

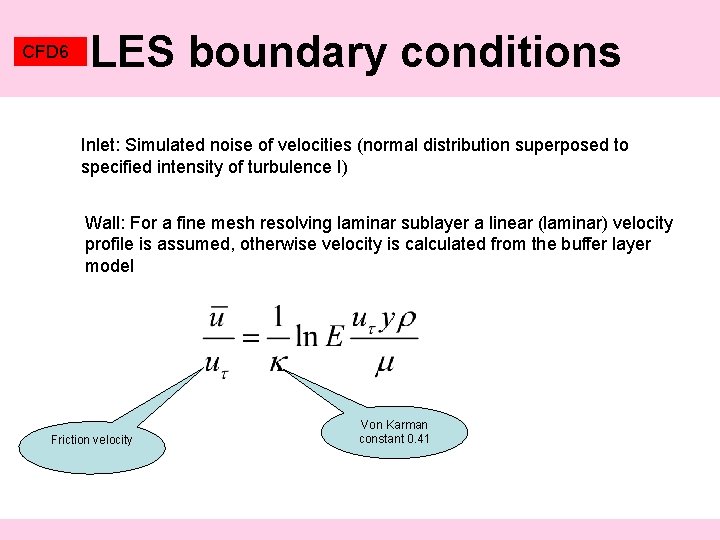

CFD 6 LES boundary conditions Inlet: Simulated noise of velocities (normal distribution superposed to specified intensity of turbulence I) Wall: For a fine mesh resolving laminar sublayer a linear (laminar) velocity profile is assumed, otherwise velocity is calculated from the buffer layer model Friction velocity Von Karman constant 0. 41

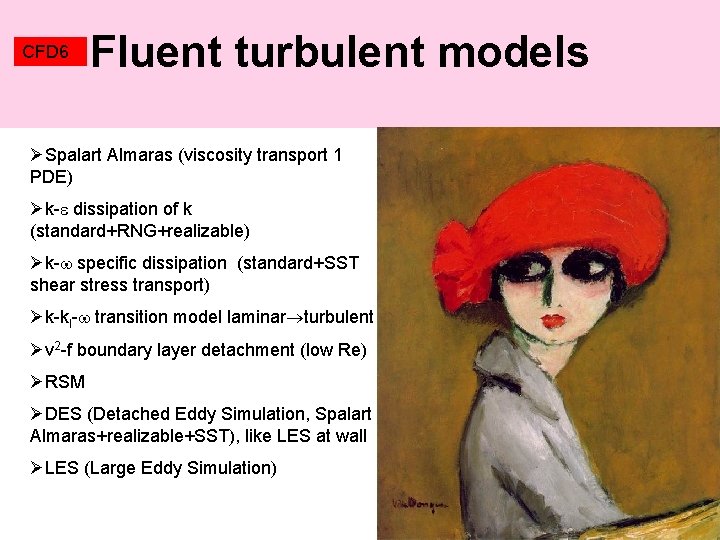

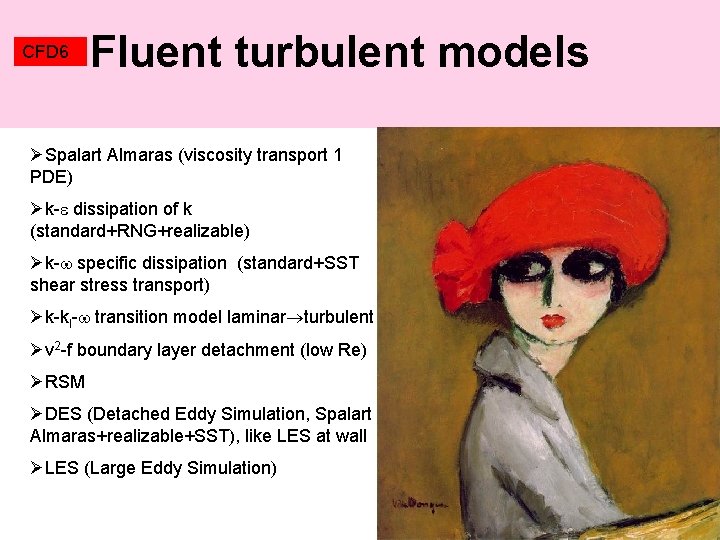

CFD 6 Fluent turbulent models ØSpalart Almaras (viscosity transport 1 PDE) Øk- dissipation of k (standard+RNG+realizable) Øk- specific dissipation (standard+SST shear stress transport) Øk-kl- transition model laminar turbulent Øv 2 -f boundary layer detachment (low Re) ØRSM ØDES (Detached Eddy Simulation, Spalart Almaras+realizable+SST), like LES at wall ØLES (Large Eddy Simulation)

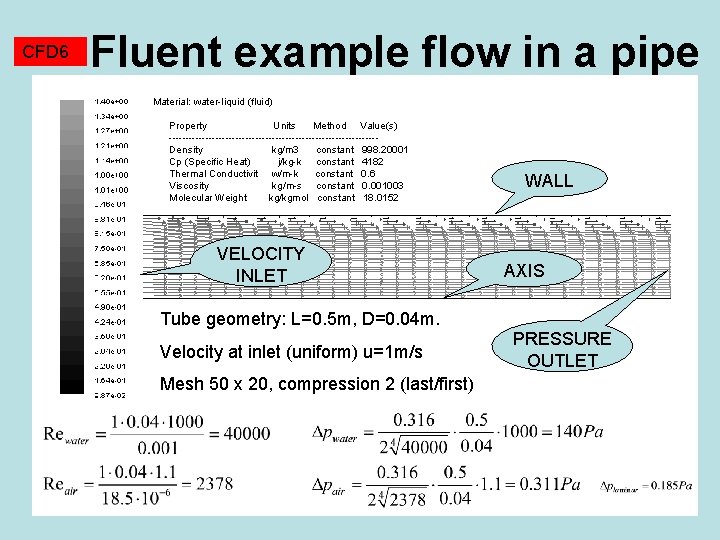

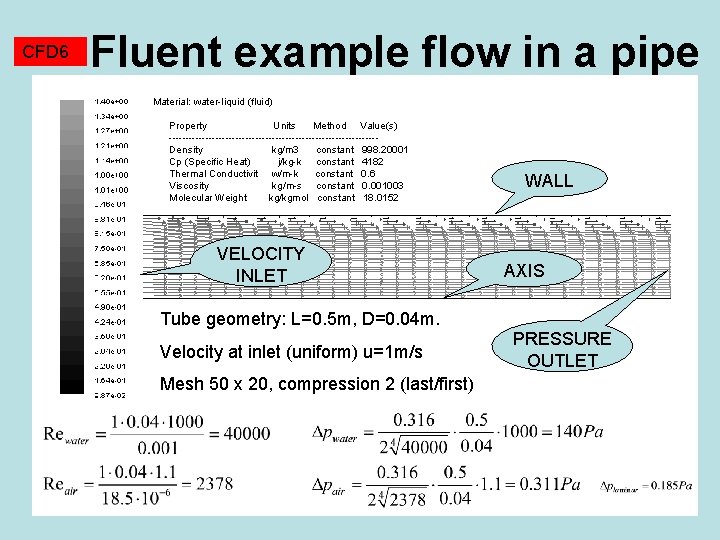

CFD 6 Fluent example flow in a pipe Material: water-liquid (fluid) Property Units Method Value(s) ------------------------------- Density kg/m 3 constant 998. 20001 Cp (Specific Heat) j/kg-k constant 4182 Thermal Conductivit w/m-k constant 0. 6 Viscosity kg/m-s constant 0. 001003 Molecular Weight kg/kgmol constant 18. 0152 VELOCITY INLET WALL AXIS Tube geometry: L=0. 5 m, D=0. 04 m. Velocity at inlet (uniform) u=1 m/s Mesh 50 x 20, compression 2 (last/first) PRESSURE OUTLET

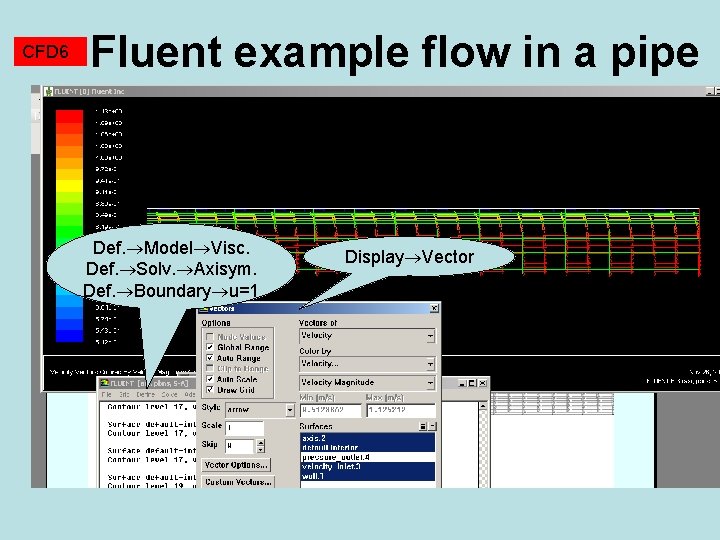

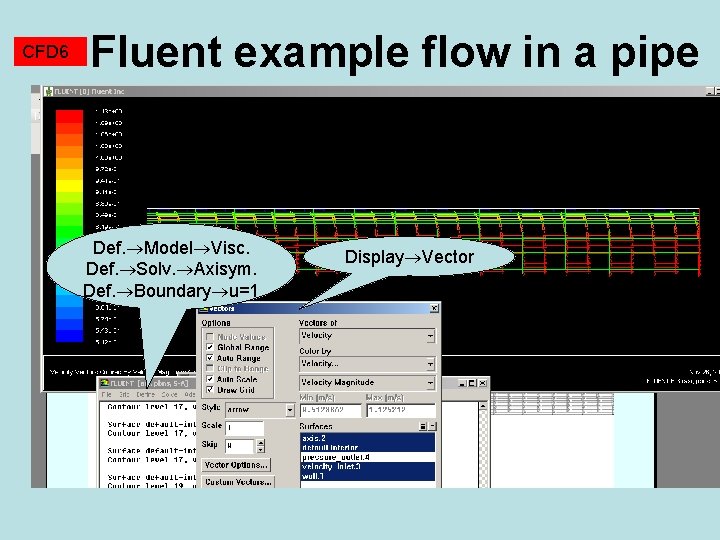

CFD 6 Fluent example flow in a pipe Voda Def. Model Visc. Def. Solv. Axisym. Def. Boundary u=1 Display Vector s

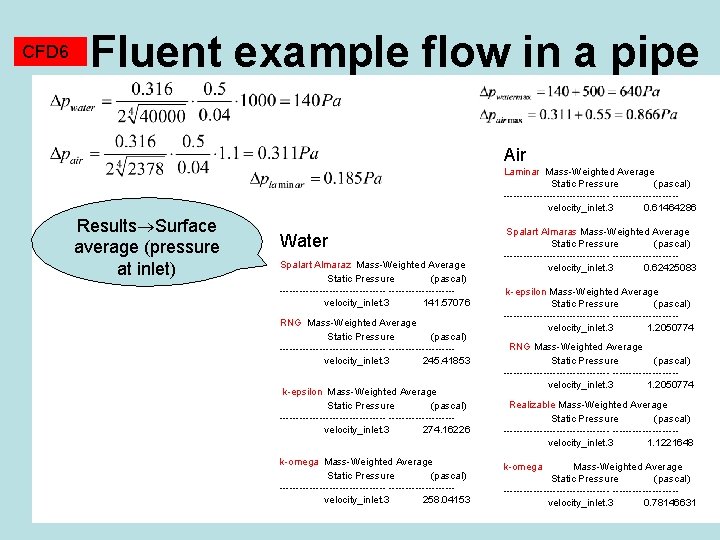

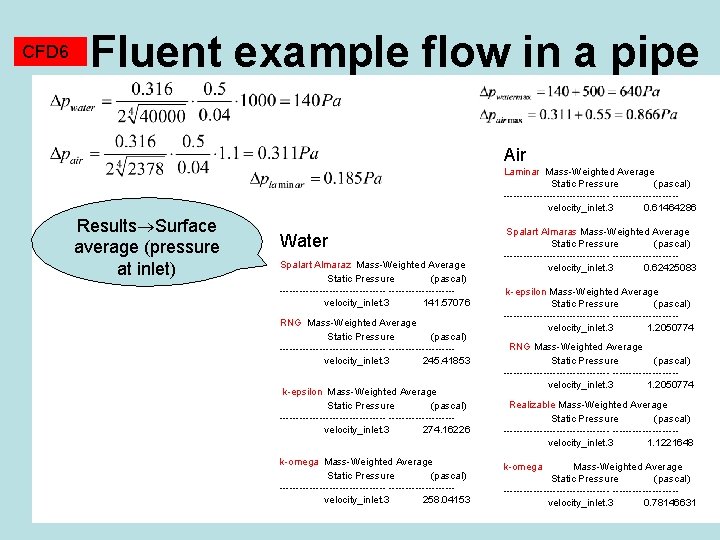

CFD 6 Fluent example flow in a pipe Air Laminar Mass-Weighted Average Static Pressure (pascal) ---------------- velocity_inlet. 3 0. 61464286 Results Surface average (pressure at inlet) Water Spalart Almaraz Mass-Weighted Average Static Pressure (pascal) ---------------- velocity_inlet. 3 141. 57076 RNG Mass-Weighted Average Static Pressure (pascal) ---------------- velocity_inlet. 3 245. 41853 k-epsilon Mass-Weighted Average Static Pressure (pascal) ---------------- velocity_inlet. 3 274. 16226 k-omega Mass-Weighted Average Static Pressure (pascal) ---------------- velocity_inlet. 3 258. 04153 Spalart Almaras Mass-Weighted Average Static Pressure (pascal) ---------------- velocity_inlet. 3 0. 62425083 k-epsilon Mass-Weighted Average Static Pressure (pascal) ---------------- velocity_inlet. 3 1. 2050774 RNG Mass-Weighted Average Static Pressure (pascal) ---------------- velocity_inlet. 3 1. 2050774 Realizable Mass-Weighted Average Static Pressure (pascal) ---------------- velocity_inlet. 3 1. 1221648 k-omega Mass-Weighted Average Static Pressure (pascal) ---------------- velocity_inlet. 3 0. 78146631

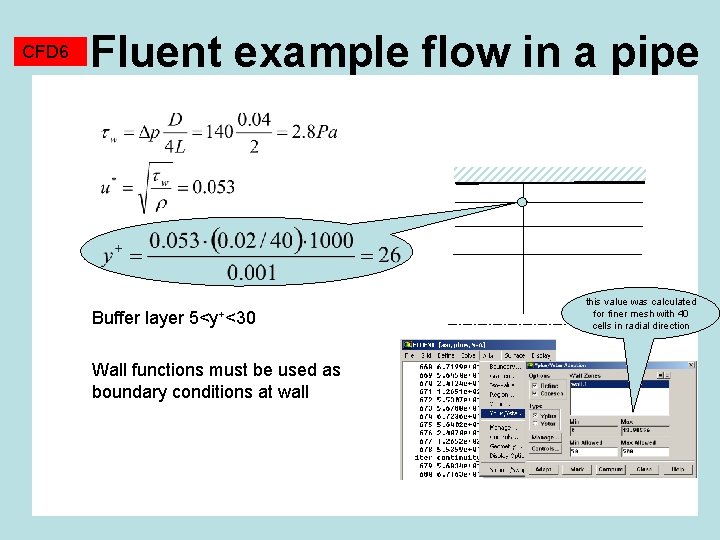

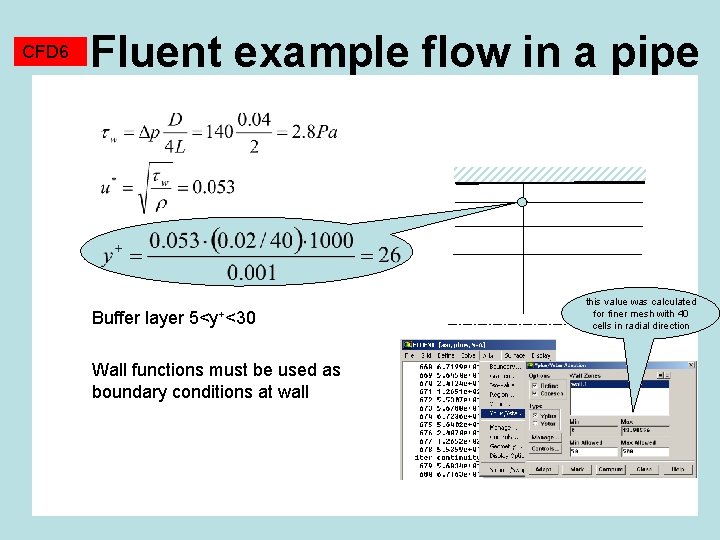

CFD 6 Fluent example flow in a pipe Buffer layer 5<y+<30 Wall functions must be used as boundary conditions at wall this value was calculated for finer mesh with 40 cells in radial direction

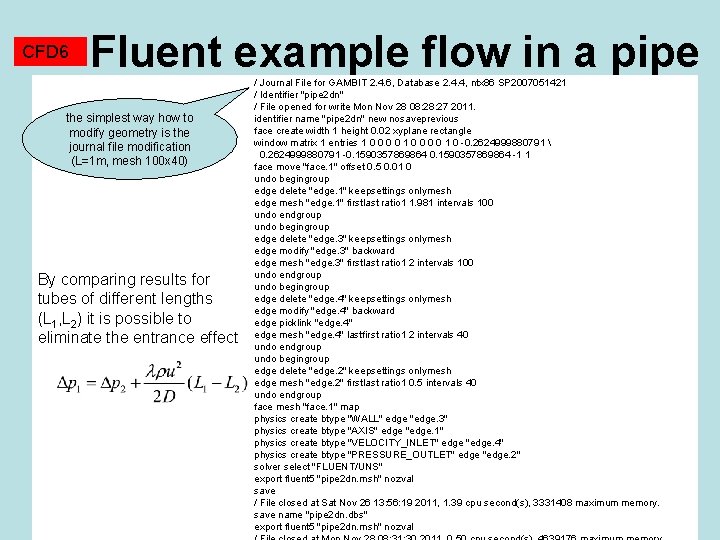

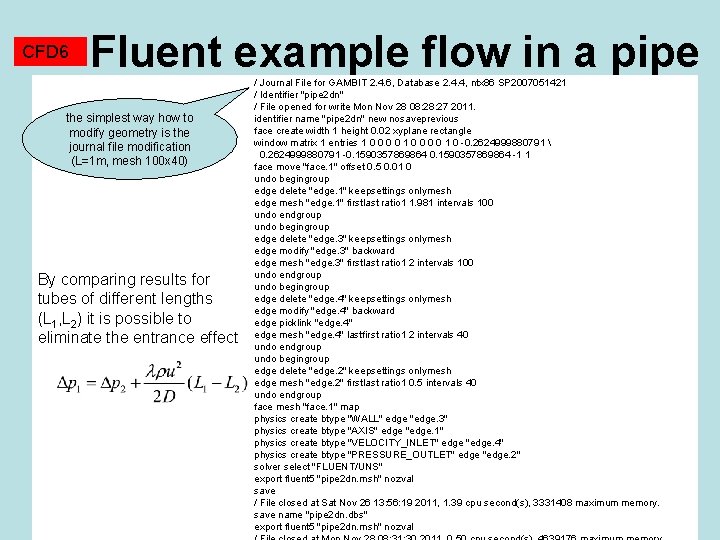

CFD 6 Fluent example flow in a pipe the simplest way how to modify geometry is the journal file modification (L=1 m, mesh 100 x 40) By comparing results for tubes of different lengths (L 1, L 2) it is possible to eliminate the entrance effect / Journal File for GAMBIT 2. 4. 6, Database 2. 4. 4, ntx 86 SP 2007051421 / Identifier "pipe 2 dn" / File opened for write Mon Nov 28 08: 27 2011. identifier name "pipe 2 dn" new nosaveprevious face create width 1 height 0. 02 xyplane rectangle window matrix 1 entries 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 -0. 2624999880791 0. 2624999880791 -0. 1590357869864 -1 1 face move "face. 1" offset 0. 5 0. 01 0 undo begingroup edge delete "edge. 1" keepsettings onlymesh edge mesh "edge. 1" firstlast ratio 1 1. 981 intervals 100 undo endgroup undo begingroup edge delete "edge. 3" keepsettings onlymesh edge modify "edge. 3" backward edge mesh "edge. 3" firstlast ratio 1 2 intervals 100 undo endgroup undo begingroup edge delete "edge. 4" keepsettings onlymesh edge modify "edge. 4" backward edge picklink "edge. 4" edge mesh "edge. 4" lastfirst ratio 1 2 intervals 40 undo endgroup undo begingroup edge delete "edge. 2" keepsettings onlymesh edge mesh "edge. 2" firstlast ratio 1 0. 5 intervals 40 undo endgroup face mesh "face. 1" map physics create btype "WALL" edge "edge. 3" physics create btype "AXIS" edge "edge. 1" physics create btype "VELOCITY_INLET" edge "edge. 4" physics create btype "PRESSURE_OUTLET" edge "edge. 2" solver select "FLUENT/UNS" export fluent 5 "pipe 2 dn. msh" nozval save / File closed at Sat Nov 26 13: 56: 19 2011, 1. 39 cpu second(s), 3331408 maximum memory. save name "pipe 2 dn. dbs" export fluent 5 "pipe 2 dn. msh" nozval

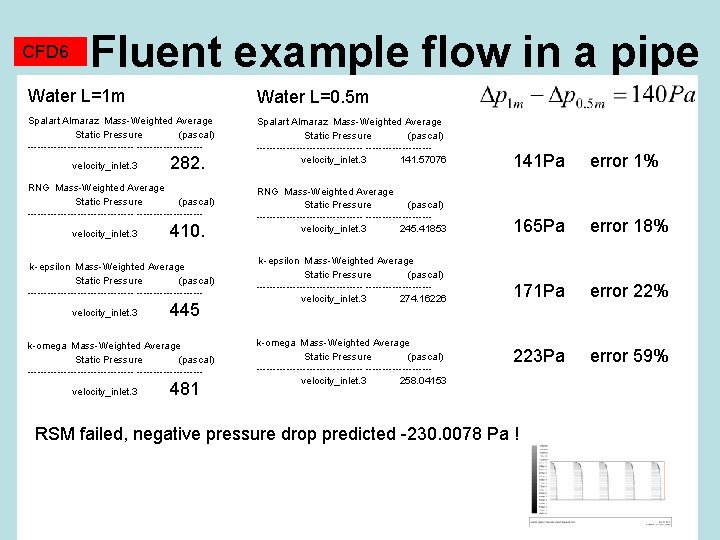

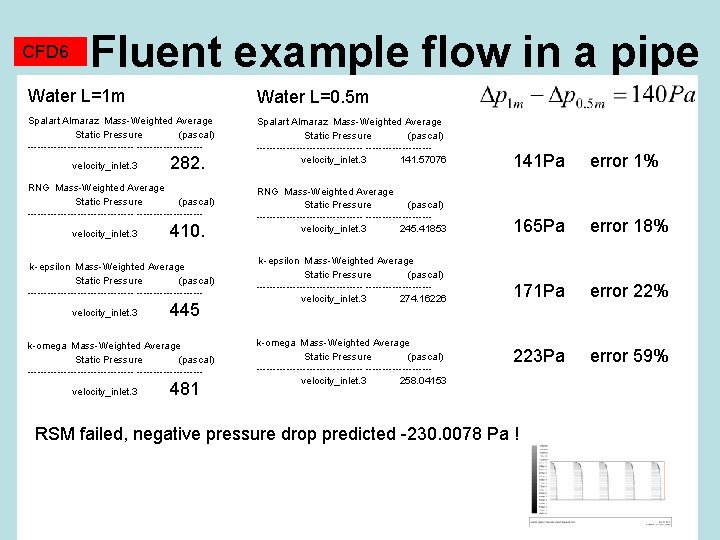

Fluent example flow in a pipe CFD 6 Water L=1 m Spalart Almaraz Mass-Weighted Average Static Pressure (pascal) ---------------- 282. velocity_inlet. 3 RNG Mass-Weighted Average Static Pressure (pascal) ---------------- 410. velocity_inlet. 3 k-epsilon Mass-Weighted Average Static Pressure (pascal) ---------------- 445 Water L=0. 5 m Spalart Almaraz Mass-Weighted Average Static Pressure (pascal) ---------------- velocity_inlet. 3 141. 57076 141 Pa error 1% RNG Mass-Weighted Average Static Pressure (pascal) ---------------- velocity_inlet. 3 245. 41853 165 Pa error 18% k-epsilon Mass-Weighted Average Static Pressure (pascal) ---------------- velocity_inlet. 3 274. 16226 171 Pa error 22% velocity_inlet. 3 k-omega Mass-Weighted Average Static Pressure (pascal) ---------------- 481 k-omega Mass-Weighted Average Static Pressure (pascal) ---------------- velocity_inlet. 3 258. 04153 223 Pa error 59% velocity_inlet. 3 RSM failed, negative pressure drop predicted -230. 0078 Pa !