Centralized Architectures Figure 2 3 General interaction between

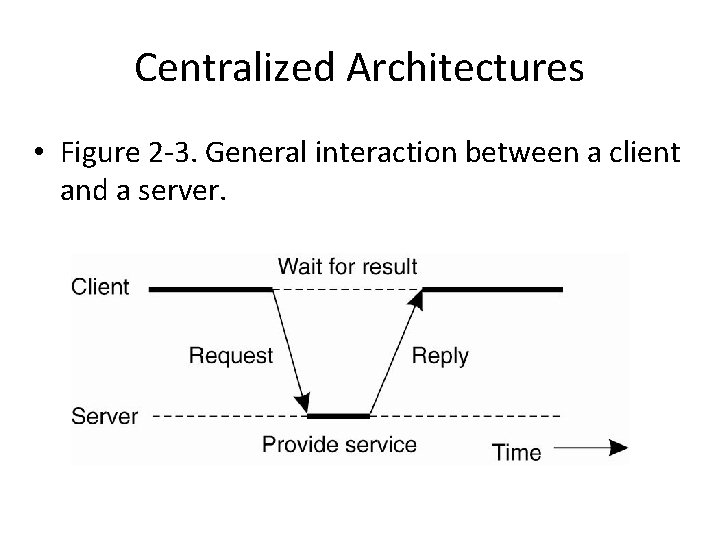

Centralized Architectures • Figure 2 -3. General interaction between a client and a server.

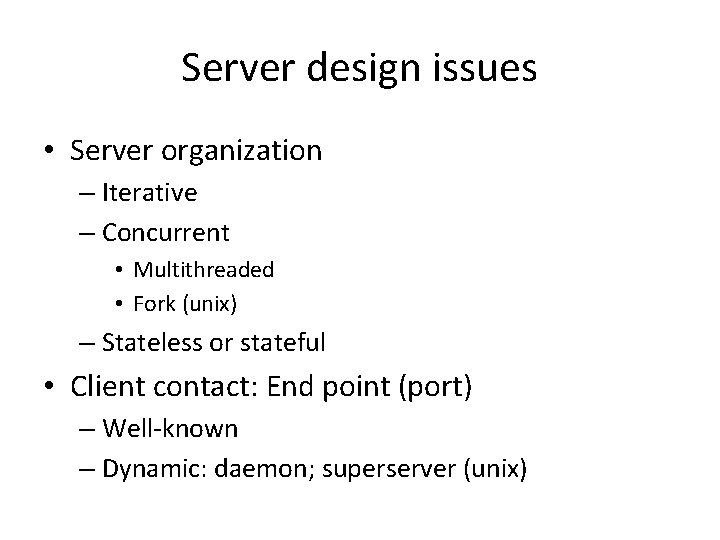

Server design issues • Server organization – Iterative – Concurrent • Multithreaded • Fork (unix) – Stateless or stateful • Client contact: End point (port) – Well-known – Dynamic: daemon; superserver (unix)

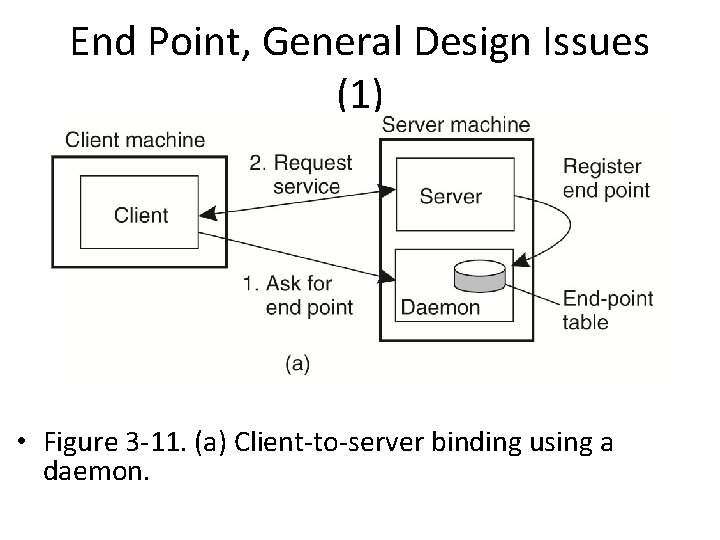

End Point, General Design Issues (1) • Figure 3 -11. (a) Client-to-server binding using a daemon.

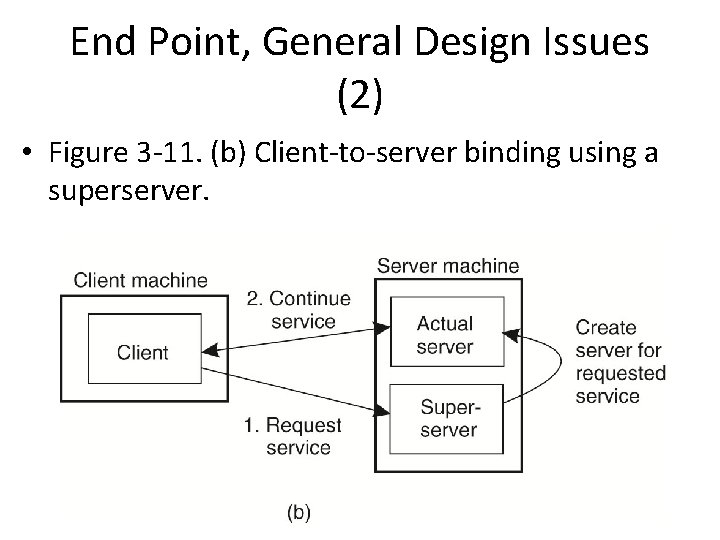

End Point, General Design Issues (2) • Figure 3 -11. (b) Client-to-server binding using a superserver.

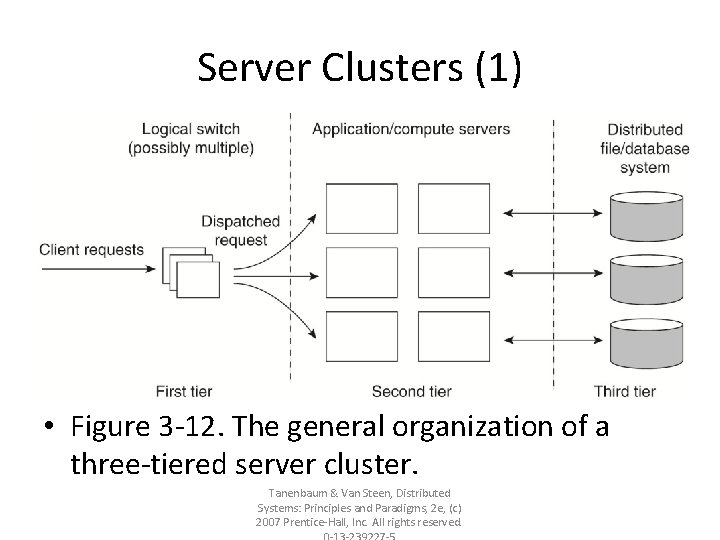

Server Clusters (1) • Figure 3 -12. The general organization of a three-tiered server cluster. Tanenbaum & Van Steen, Distributed Systems: Principles and Paradigms, 2 e, (c) 2007 Prentice-Hall, Inc. All rights reserved.

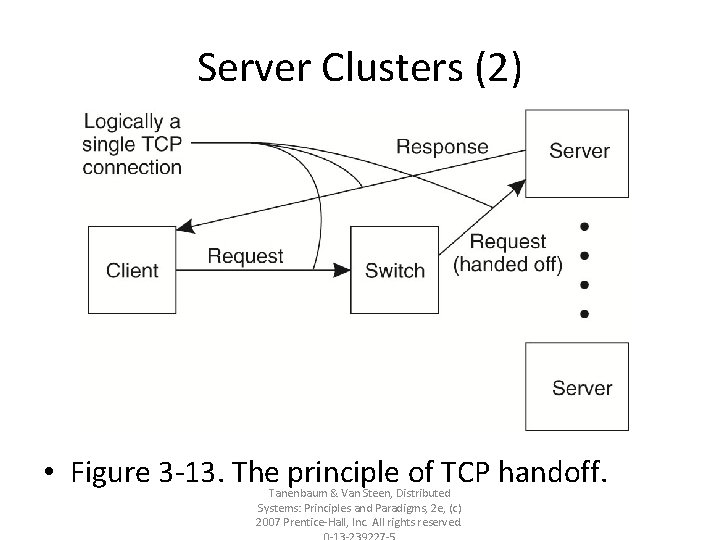

Server Clusters (2) • Figure 3 -13. The principle of TCP handoff. Tanenbaum & Van Steen, Distributed Systems: Principles and Paradigms, 2 e, (c) 2007 Prentice-Hall, Inc. All rights reserved.

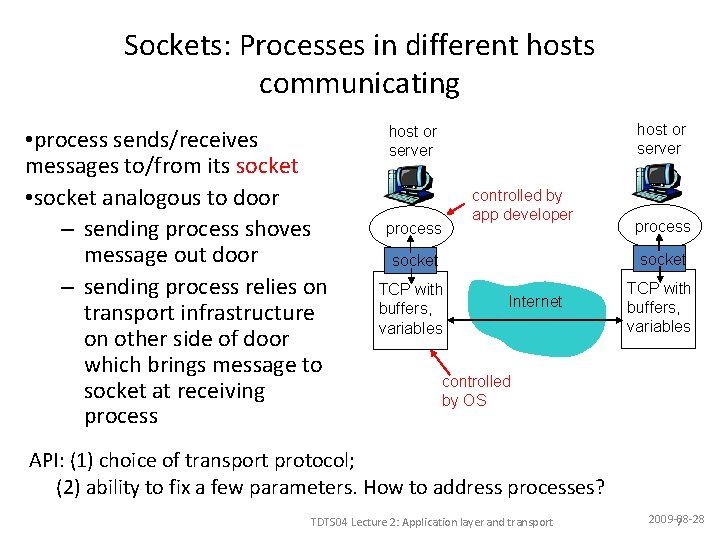

Sockets: Processes in different hosts communicating • process sends/receives messages to/from its socket • socket analogous to door – sending process shoves message out door – sending process relies on transport infrastructure on other side of door which brings message to socket at receiving process host or server process controlled by app developer process socket TCP with buffers, variables Internet TCP with buffers, variables controlled by OS API: (1) choice of transport protocol; (2) ability to fix a few parameters. How to address processes? TDTS 04 Lecture 2: Application layer and transport 2009 -08 -28 7

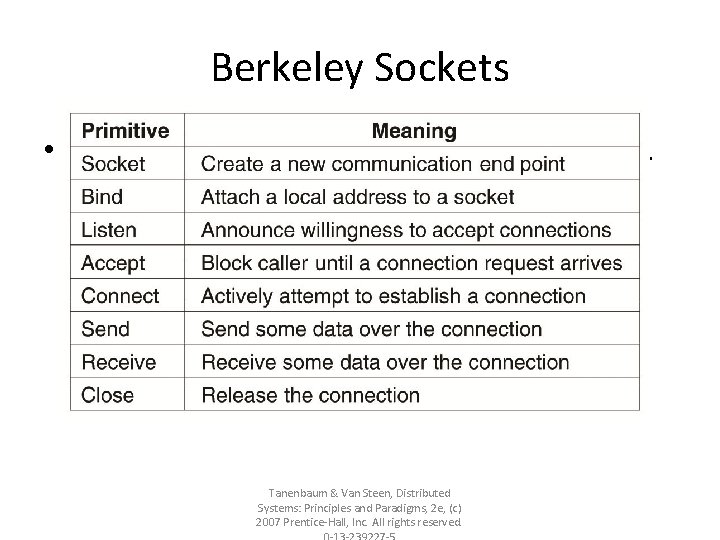

Berkeley Sockets • Figure 4 -14. The socket primitives for TCP/IP. Tanenbaum & Van Steen, Distributed Systems: Principles and Paradigms, 2 e, (c) 2007 Prentice-Hall, Inc. All rights reserved.

Connection-oriented socket (tcp) • Figure 4 -15. Connection-oriented communication pattern using sockets. Tanenbaum & Van Steen, Distributed Systems: Principles and Paradigms, 2 e, (c) 2007 Prentice-Hall, Inc. All rights reserved.

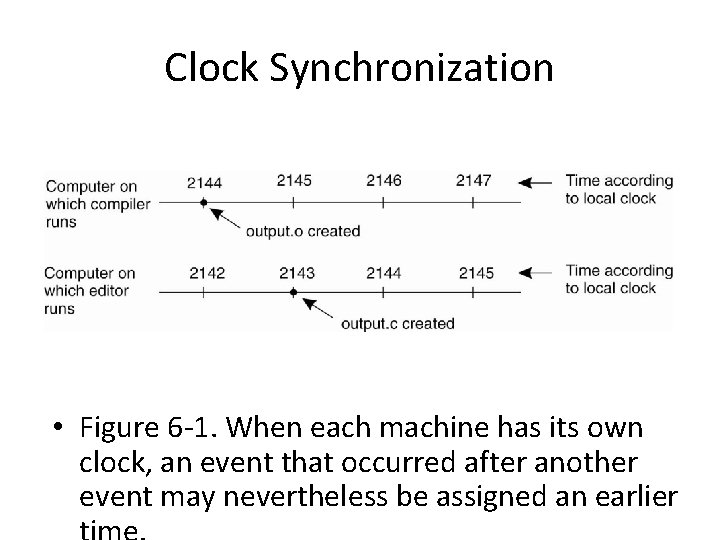

Clock Synchronization • Figure 6 -1. When each machine has its own clock, an event that occurred after another event may nevertheless be assigned an earlier

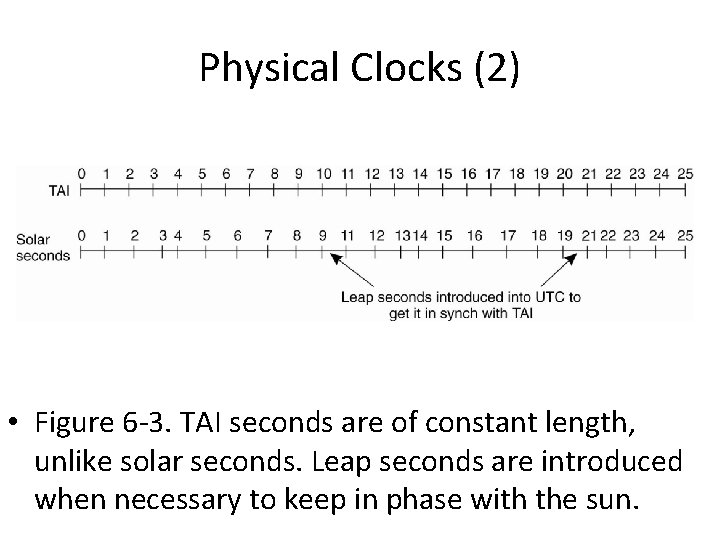

Physical Clocks (2) • Figure 6 -3. TAI seconds are of constant length, unlike solar seconds. Leap seconds are introduced when necessary to keep in phase with the sun.

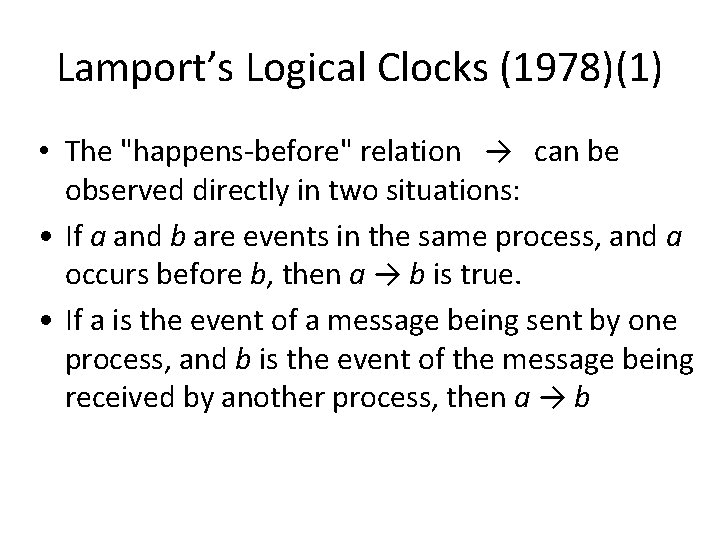

Lamport’s Logical Clocks (1978)(1) • The "happens-before" relation → can be observed directly in two situations: • If a and b are events in the same process, and a occurs before b, then a → b is true. • If a is the event of a message being sent by one process, and b is the event of the message being received by another process, then a → b

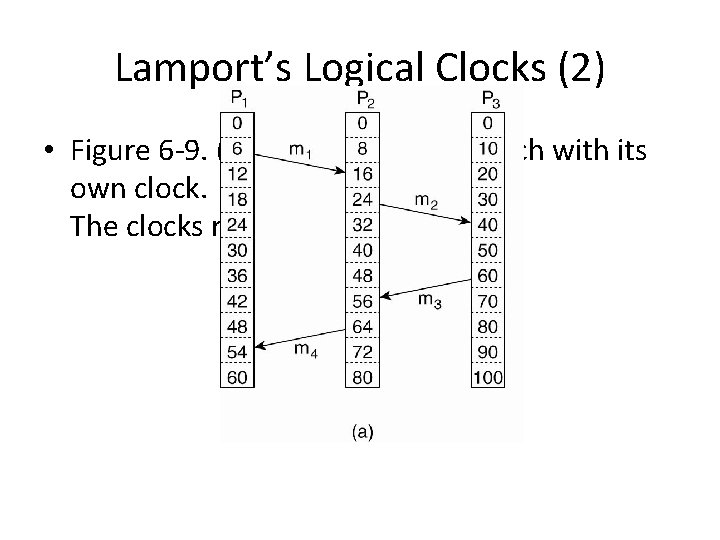

Lamport’s Logical Clocks (2) • Figure 6 -9. (a) Three processes, each with its own clock. The clocks run at different rates.

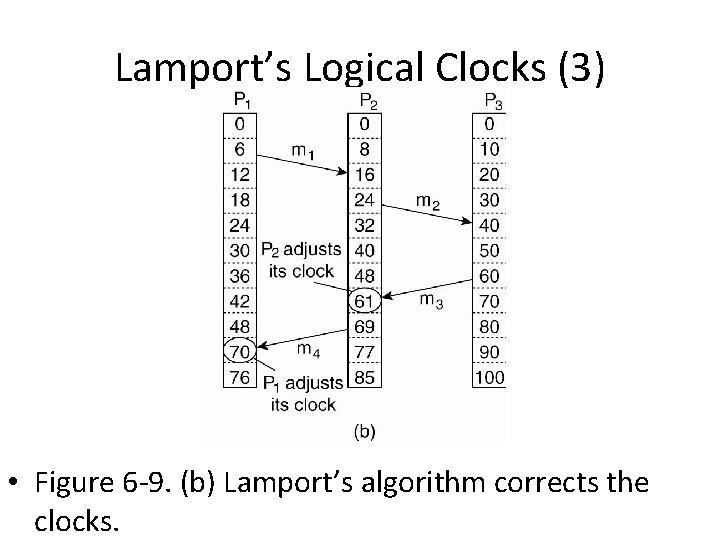

Lamport’s Logical Clocks (3) • Figure 6 -9. (b) Lamport’s algorithm corrects the clocks.

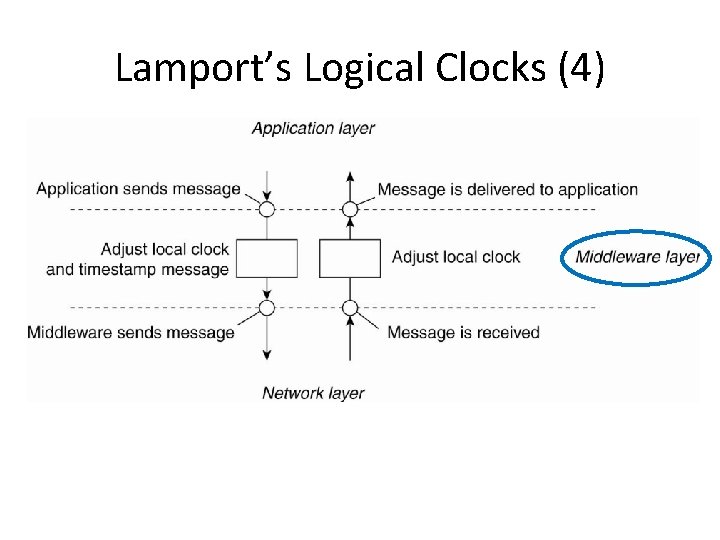

Lamport’s Logical Clocks (4) • Figure 6 -10. The positioning of Lamport’s logical clocks in distributed systems.

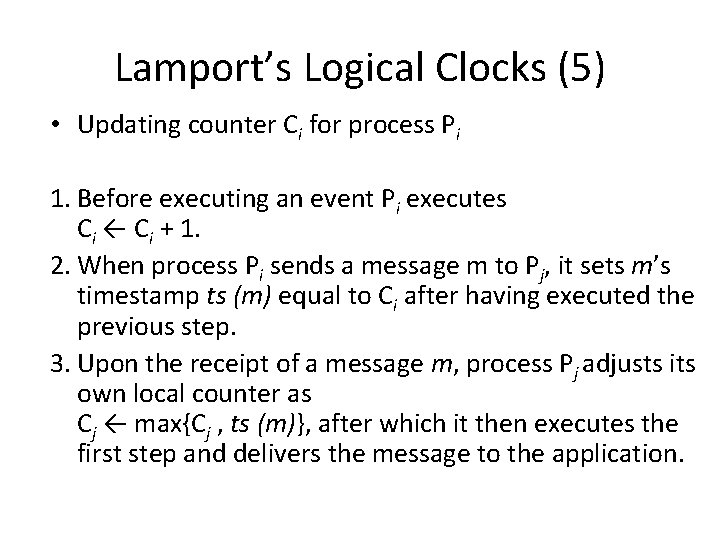

Lamport’s Logical Clocks (5) • Updating counter Ci for process Pi 1. Before executing an event Pi executes Ci ← Ci + 1. 2. When process Pi sends a message m to Pj, it sets m’s timestamp ts (m) equal to Ci after having executed the previous step. 3. Upon the receipt of a message m, process Pj adjusts its own local counter as Cj ← max{Cj , ts (m)}, after which it then executes the first step and delivers the message to the application.

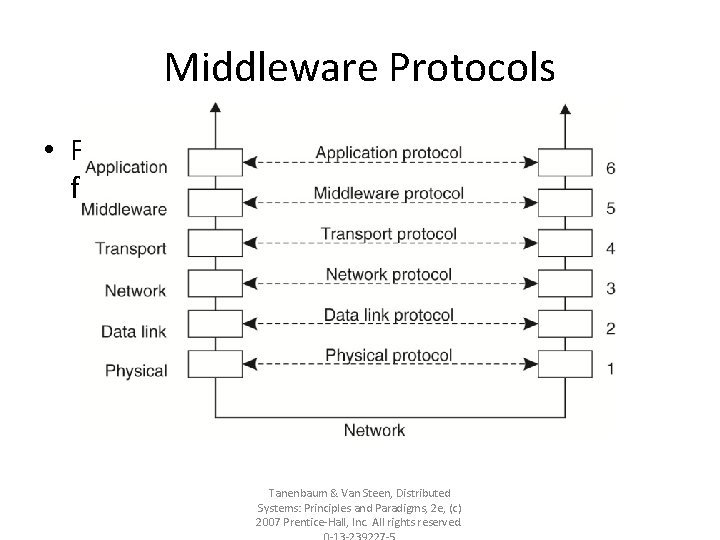

Middleware Protocols • Figure 4 -3. An adapted reference model for networked communication. Tanenbaum & Van Steen, Distributed Systems: Principles and Paradigms, 2 e, (c) 2007 Prentice-Hall, Inc. All rights reserved.

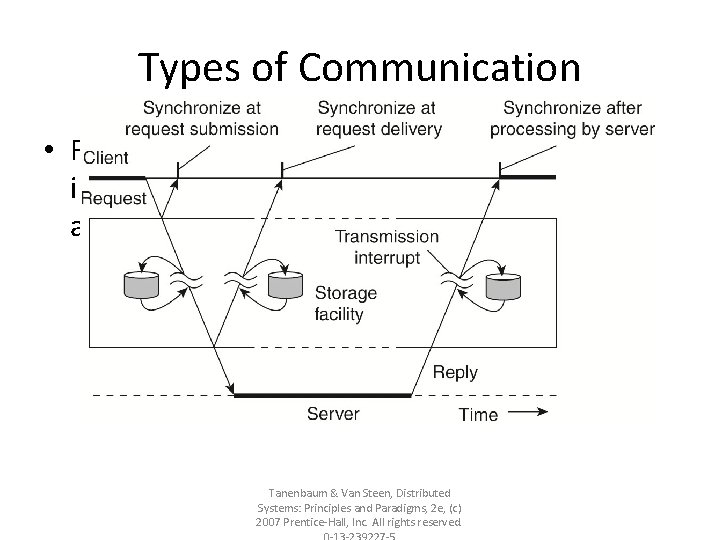

Types of Communication • Figure 4 -4. Viewing middleware as an intermediate (distributed) service in application-level communication. Tanenbaum & Van Steen, Distributed Systems: Principles and Paradigms, 2 e, (c) 2007 Prentice-Hall, Inc. All rights reserved.

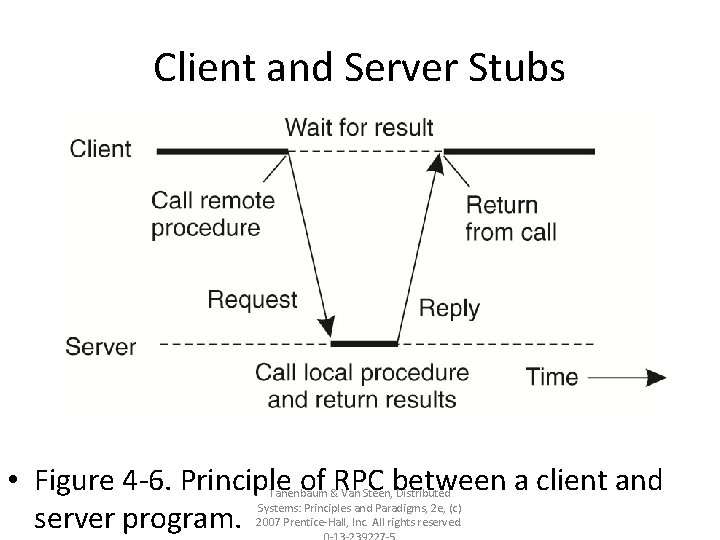

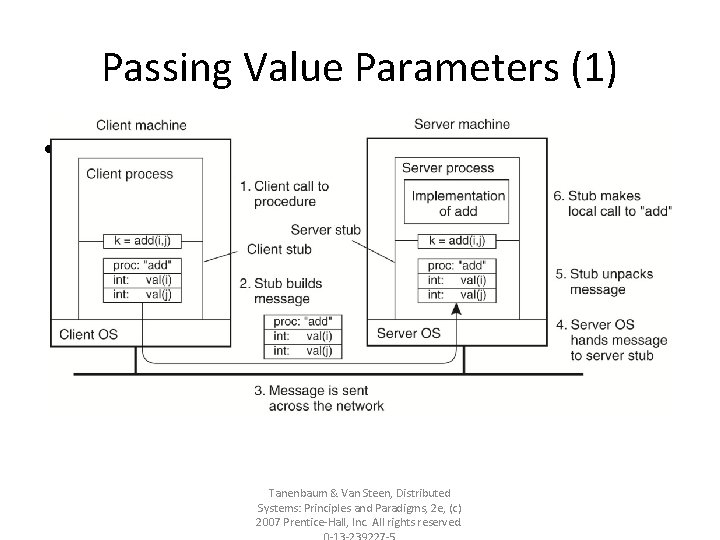

Client and Server Stubs • Figure 4 -6. Principle of RPC between a client and server program. Tanenbaum & Van Steen, Distributed Systems: Principles and Paradigms, 2 e, (c) 2007 Prentice-Hall, Inc. All rights reserved.

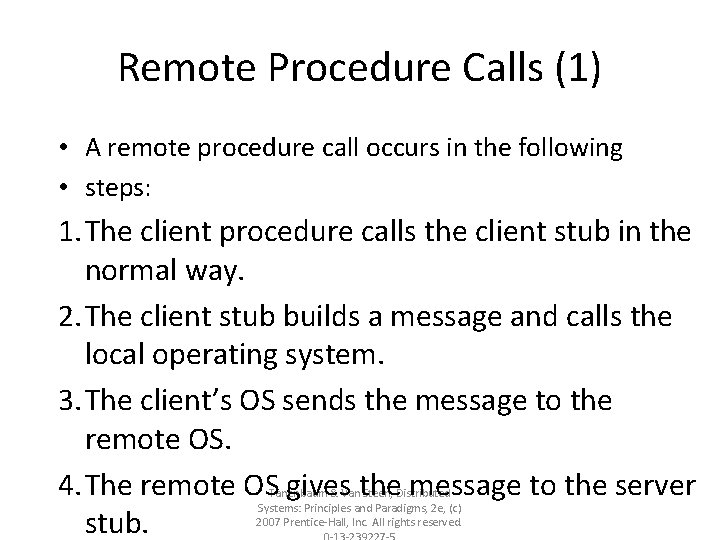

Remote Procedure Calls (1) • A remote procedure call occurs in the following • steps: 1. The client procedure calls the client stub in the normal way. 2. The client stub builds a message and calls the local operating system. 3. The client’s OS sends the message to the remote OS. 4. The remote OS gives the message to the server stub. Tanenbaum & Van Steen, Distributed Systems: Principles and Paradigms, 2 e, (c) 2007 Prentice-Hall, Inc. All rights reserved.

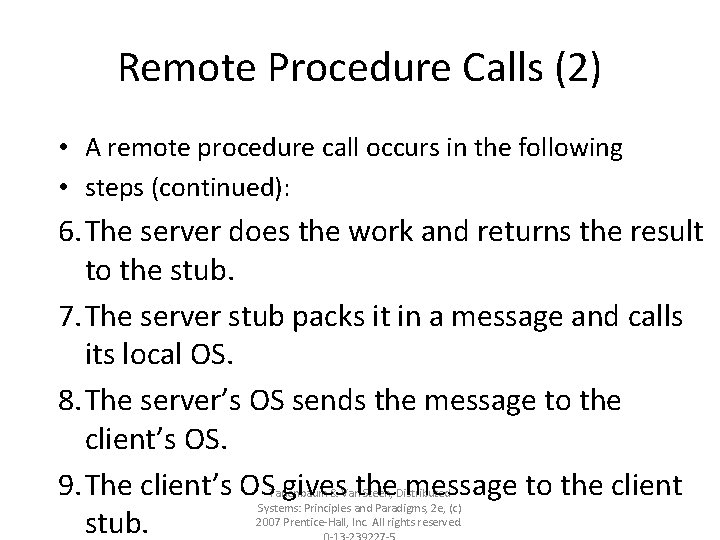

Remote Procedure Calls (2) • A remote procedure call occurs in the following • steps (continued): 6. The server does the work and returns the result to the stub. 7. The server stub packs it in a message and calls its local OS. 8. The server’s OS sends the message to the client’s OS. 9. The client’s OS gives the message to the client stub. Tanenbaum & Van Steen, Distributed Systems: Principles and Paradigms, 2 e, (c) 2007 Prentice-Hall, Inc. All rights reserved.

Passing Value Parameters (1) • Figure 4 -7. The steps involved in a doing a remote computation through RPC. Tanenbaum & Van Steen, Distributed Systems: Principles and Paradigms, 2 e, (c) 2007 Prentice-Hall, Inc. All rights reserved.

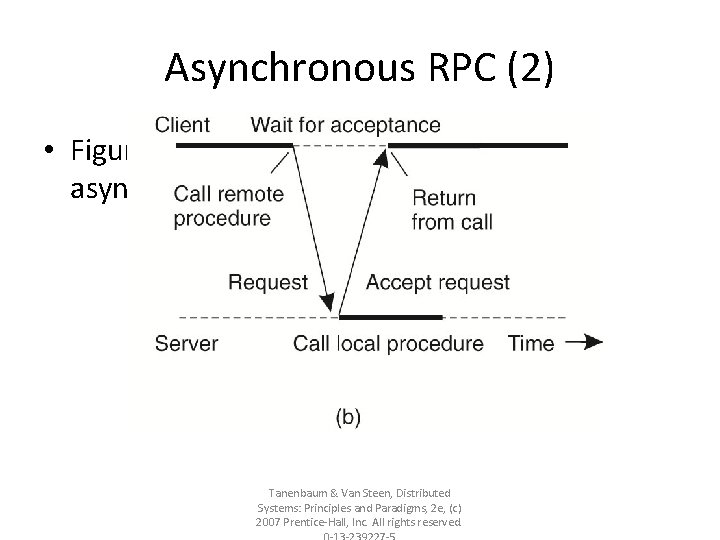

Asynchronous RPC (2) • Figure 4 -10. (b) The interaction using asynchronous RPC. Tanenbaum & Van Steen, Distributed Systems: Principles and Paradigms, 2 e, (c) 2007 Prentice-Hall, Inc. All rights reserved.

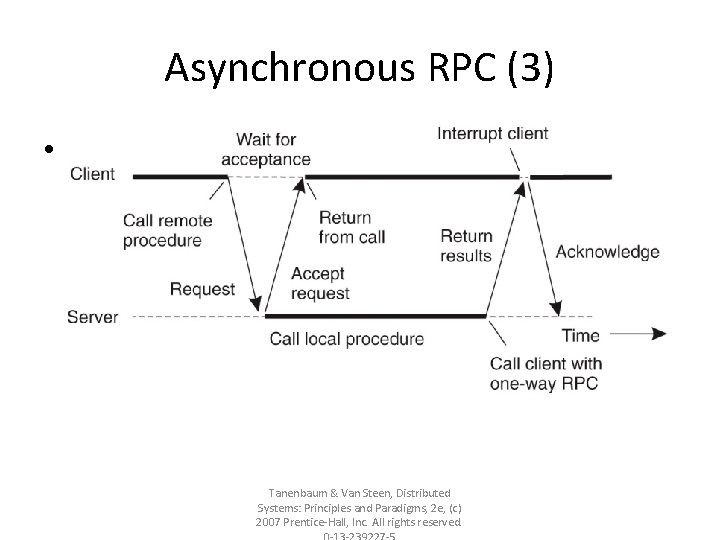

Asynchronous RPC (3) • Figure 4 -11. A client and server interacting through two asynchronous RPCs. Tanenbaum & Van Steen, Distributed Systems: Principles and Paradigms, 2 e, (c) 2007 Prentice-Hall, Inc. All rights reserved.

- Slides: 24