Censorship of Childrens Materials Understanding Censorship Today and

- Slides: 22

Censorship of Children’s Materials Understanding Censorship Today, and Advocating for Freedom to Read in an Information Setting By Sarah Sowa LIS 600 Fall 2013

Throughout this presentation, we will cover: v A brief history of the censorship of children’s materials v Who are “censors, ” and what topics are considered controversial? v Direct and indirect censorship v Examples of censorship in popular fiction v How should we deal with censors? v Conclusion: The future of censorship of children’s materials

Censorship of Children’s Materials: A Brief History v 16 th century (or earlier): fairy and folktales became the earliest children’s materials to be censored v 17 th century: John Locke “deplored children’s exposure to fairy tales and old ballads, ” and Puritans oppose fairy tales v 18 th century: Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Emile v 1802: Sarah Trimmer, The Guardian of Education, “the first magazine to carry regular reviews of children’s literature” v 19 th century: moralism began to lose momentum (Saltman, 1998) v 1900: children’s reading rooms began to become popular (Mac. Leod, 1983, p. 30)

Brief History, continued v 1922: Newberry Medal established v 1930 s: “Librarians shifted away from a ‘professional ethic of censorship to a professional ethic of freedom” v 1939: first Library Bill of Rights adopted v 1950 s: “freedom to read” for adults established as a core professional and cultural value; however, free reading for youth remained a tough subject (Kidd, p. 200, 2009) v 1960 s: Civil Rights, women’s rights, Vietnam era, led to “changing mores and altered family structures, ” and to “questions about the world traditionally pictured in children’s books” v Goal of censorship moves from protecting “the innocence of childhood” to “for the good of society (ex: Council on Interracial Books for Children) (Mac. Leod, 1983, pp. 34 -36)

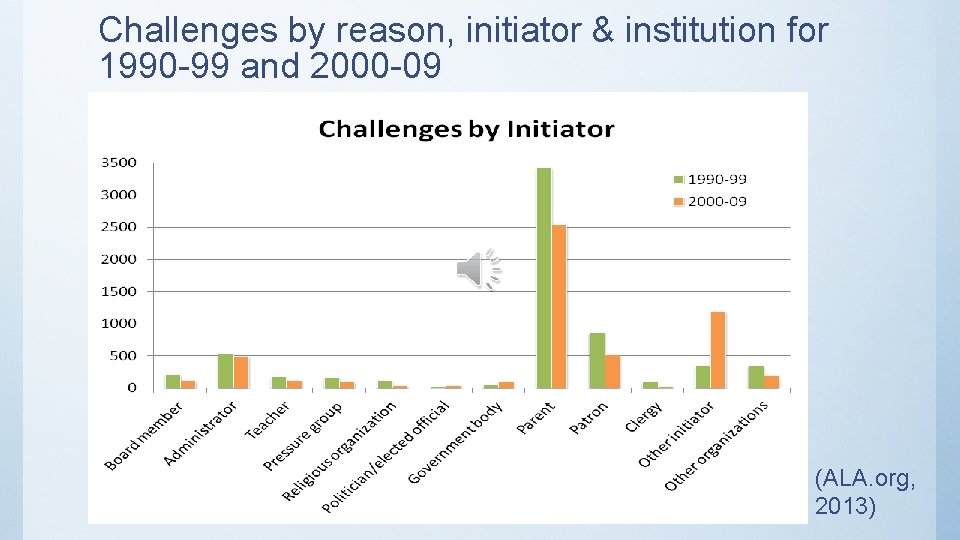

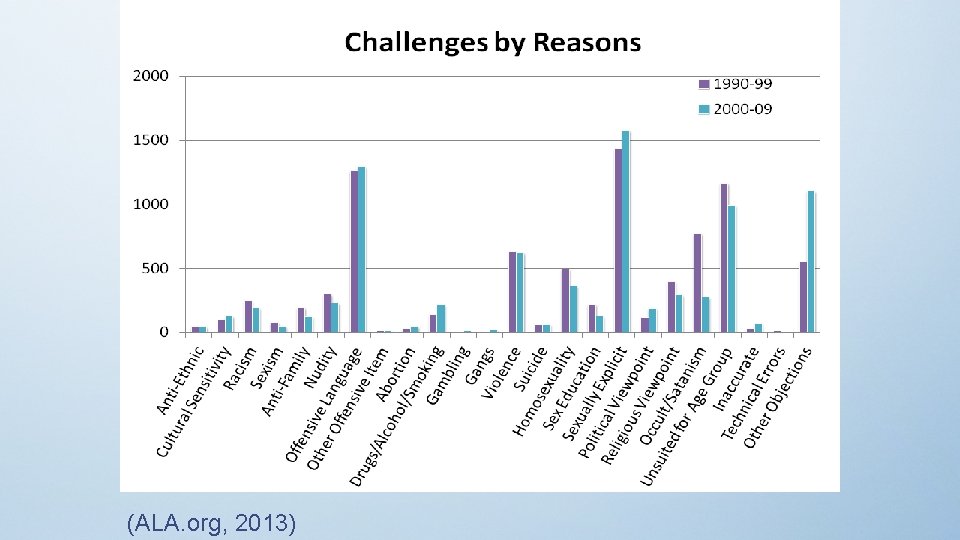

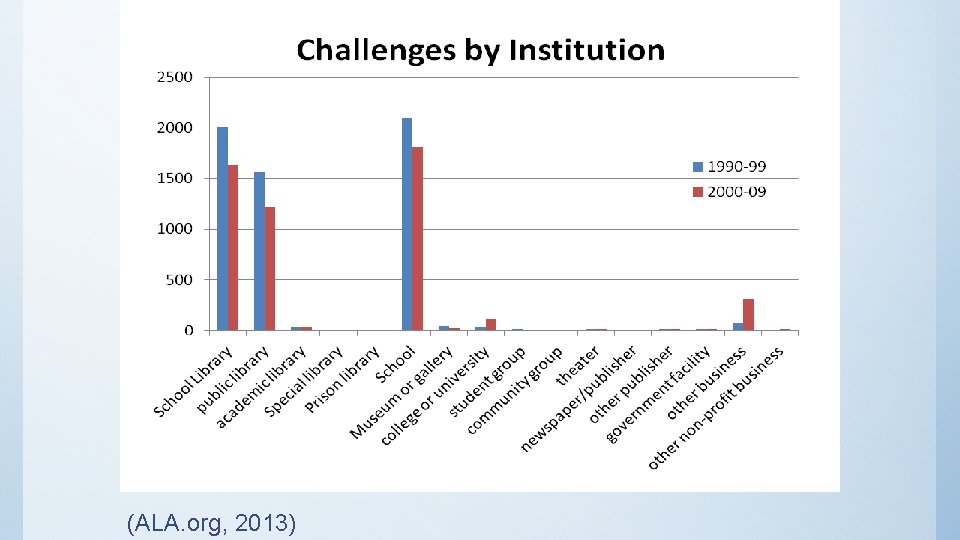

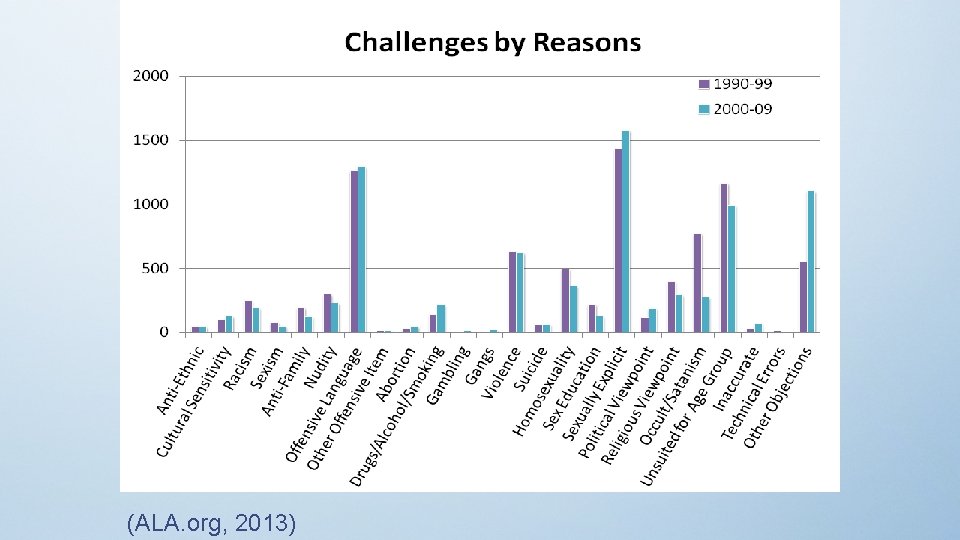

Children’s Censorship Today v 1982: Pico v. Island Trees (Swiderek, 1996, p. 593) v As of 1995, book removal rates were on the rise (Blair, 1996, p. 58) v The number of complaints made by individuals who were not parents or institutional employees tripled from 2000 -2009 compared to the previous decade; parents are the number one source of complaints, overall (ALA. org, 2013) v Top complaints from 2000 -2009: “sexually explicit, ” “offensive language” v According to the Banned Books Resource Guide(2007), approximately 85% of challenges to library materials are not made public (Kidd, 2009, p. 199)

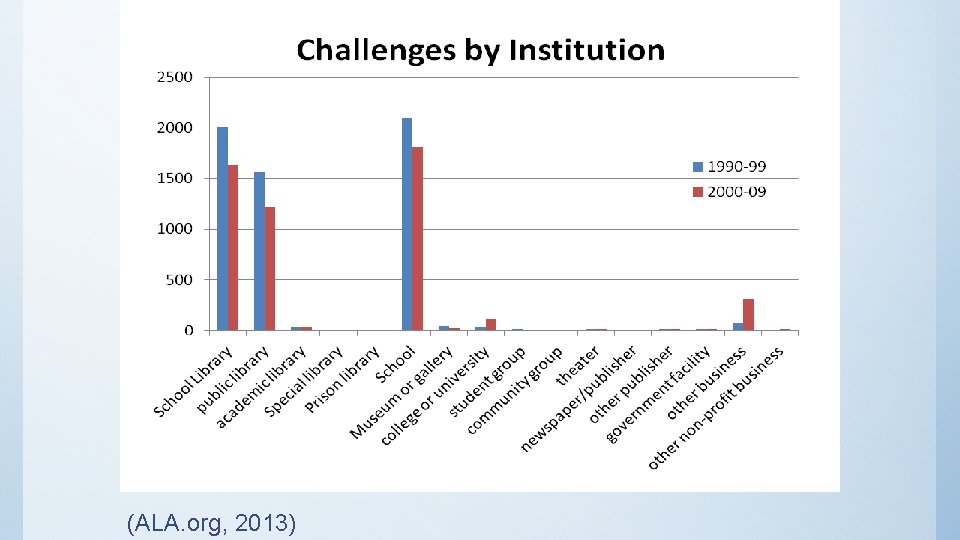

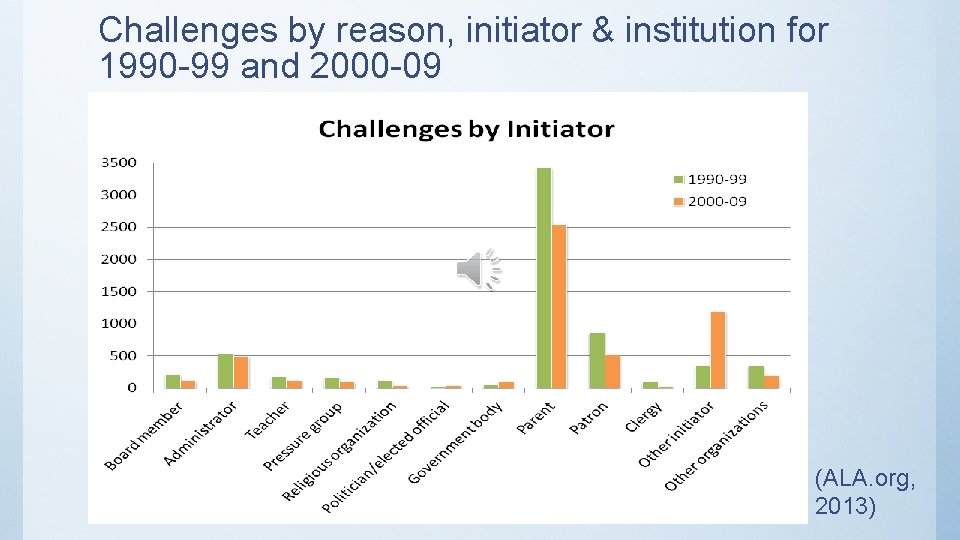

Challenges by reason, initiator & institution for 1990 -99 and 2000 -09 (ALA. org, 2013)

(ALA. org, 2013)

(ALA. org, 2013)

Who are censors? “Mary Kuhn (1992) found parents and guardians to be the single most frequent source of complaints (4/10). However, the combined challenges of teachers, principals, school staff, and library workers were more than those of parents. ” Advocacy against censorship from information professionals is critical “Jenkinson (1985) also found when a parent or community member complained, less than half of the challenged materials were removed, but when a teacher, administrator, or school board member complained, four out of five times the materials were removed” (Blair, 1996, p. 58)

Who Should Be Censors? Christopher Winch (1993) makes the claim that only parents have the right to censor materials for children, either through: Primary rights: what parents allow into their homes (ex: what books they buy) Secondary rights: what parents expose their children to outside the home (ex: what schools they choose) Winch supports primary and secondary parental rights to censor their own children’s experiences. For example, if a parent dislikes a school library selection, they have the right to put his/her child in a different school. He claims that non-parental claims for censorship are either reactionary, conservative, or revolutionary– none of which are valid. (Winch, 1993, 43 -45)

Liberal versus Conservative Censors Liberal, or progressive censors want to eliminate racism, sexism, and other discriminatory topics, and hold the belief that “if society is to change, the books cannot be neutral. If [books] are not liberating, they are by definition damaging. ” Conservative censors are against books they see as “biased toward the increasing centralized power of a secular humanistic state, ” or “that will ultimately destroy the family, decent social standards, and basic principles of decentralized government. ” (Mac. Leod, 1983, pp. 27, 36).

Stereotype of the “Censor-Moron” Kenneth Kidd (2009) point out that the public views librarians as defenders of freedom to read and think, whereas censors are seen as agents of “thought control” (p. 202). He asserts that current approaches to censorship are “making more difficult an objective discussion of censorship struggles” and feed the “ongoing construction of the censor as a ‘moron’” (p. 199). By acknowledging the many agendas and backgrounds of censors (ex: liberal versus conservative), Kidd says that we can begin to make real, lasting change in the occurrence of censorship and its resolution. “Demonizing the censor does little to solve the problem; in fact, it keeps the whole operation going” (Kidd, 2009, p. 205).

Direct Versus Indirect Censorship v Direct censorship: refusal to include materials, removal of materials, mutilation or defacing of materials to remove “offensive” content v Material is sometimes removed by administrative officials (such as school principals) without cause, simply because it seems to have potential to cause a “costly court battle” (Blair, 1996, p. 58) v Indirect censorship: v Censorship through selection v “Silent censorship” v Labeling v Educational programs, such as No Child Left Behind (NCLB)/”backdoor censorship”

Censorship through Selection Kenneth Kidd notes that Lester Asheim depicts the censor as “negative” and uninformed, and the librarian as “positive and educated in his 1953 article, “Not Censorship But Selection” Kidd, however, claims that the main difference between the censor and the librarian is “trust” in the librarian as an educated professional and as a guardian of intellectual freedom. He believes that librarians are inevitably censors in their own right, both through selection/rejection and through “prizing” many of the books that face censorship challenges (Kidd, 2009, pp. 201 -202)

“Silent Censorship” v Textbook publishers: certain lines or information deleted without notification (ex: sexual lines of Romeo and Juliet omitted in certain editions) v “Silent exclusion of non-print media”: a teacher may avoid showing or be prohibited from showing the movie version of a book v “The stability of the top ten”: the fact that certain texts (ex: The Scarlett Letter, Catcher in the Rye) remain on the most-censored lists for years. Where, asks Nancy Mc. Cracken (1994), are the books that deal with the most contemporary issues (AIDs, homosexuality, etc. ) Teachers may be avoiding such books to prevent possible controversy, which disables diversity and discussion in the classroom (Mc. Cracken, 1994).

Labeling While some argue that labeling helps children identify books that match their interest and reading level, others assert that it: v Encourages children to choose books that help them meet requirements or earn rewards (those labeled as part of a reading program) v Deters students from choosing books that aren’t part of a reading program, or that are not labeled as award-winning v May embarrass children who choose books lower than their supposed reading level v May not allow children the freedom to choose items above their reading level (Hunt and Wachsmann, 2012, pp. 90 -91)

No Child Left Behind (NCLB) This eleven-year-old piece of education legislation has had far-reaching effects, including some regarding censorship. The emphasis that NCLB places on achieving high standardized test scores has made “learning to read… synonymous with the right to receive phonics instruction with artificially contrived stories based on sound-letter correspondences. ” Offering culturally diverse literature is not a priority. A lack of funding combined with curriculums controlled by testing hurts diversity in education. Teachers and librarians do not have time or money for books that do not contribute to student performance on test scores. Simmons and Dresang (2001), even prior to NCLB, dubbed this kind of censorship through exclusion backdoor censorship (Lehr, 2012, pp. 27 -28)

Examples of Children’s Literature Censorship “Edgar Rice Burrough’s “Beatrix Potter's “A school librarian once told Blume that novel Tarzan of the Apes the principal of her school would not classic Tale of Peter allow her book Deenie to be put in the Rabbit was banned in was removed from the Los Angeles Public library because Deenie masturbated. England by the Library in 1929 because He said it would be different if the London County Tarzan allegedly lives in character were a boy” (Foerstel, 2002, sin with Jane” (Kidd, Council because it p. 137). 2009, p. 200) portrays only middleclass rabbits” “Chinese censors banned Lewis Carroll’s Alice books on the (Saltman, 1998) grounds that ‘Animals should not use human language’” (Kidd, 2009, p. 200). Shel Silverstein’s A Light in the Attic has been challenged due to “promotion of disrespectful behavior, as well as for images of death, horror, violence, morbidity, nudity and profanity” (Saltman, 1998) Michael Wilhoite's picture book, Daddy's Roommate, which depicts a child’s father in a positively portrayed, homosexual relationship, had 84 challenges reported to the ALA Office for Intellectual Freedom since its debut in 1990 -1998 (Saltman, 1998). This is especially high, considering we have noted that approximately 85% of complaints go unreported.

How to Deal with Censors 1. Celebrate successes and promote your program in the community. “By building a record of success, one challenge will not be blown out of proportion. ” 2. “View censorship as an opportunity, ” or “as a way to promote your entire program. ” 3. “Involve parents and community members in your program. ” 4. Make sure that there is a policy in place to keep teachers in charge of materials. Otherwise, whoever receives the initial complaint may try to take matters into their own hands without the teacher’s/librarian’s input. 5. “Empower your students. ” Information can be a valuable tool for young people “when carefully handled by the teacher. ” (Blair, 1996, pp. 60 -61)

Conclusion “Being able choose from a library of books without restriction allows readers to become selfsufficient book browsers who are not afraid to pick up any book that seems interesting or to put down a book because it is not a good fit. After all, the freedom to choose is what libraries are about” (Wachsmann, 2012, p. 92). v Censorship of children’s materials is a dynamic, ongoing process, that requires the advocacy of librarians. v The face of the censor, and his/her mission, is not easily defined. Librarians need to keep an open mind about censors, and to monitor their own actions for bias and censorship. v Censorship is not always overt. v While outside interest groups and individuals are free to share their opinions, parents should have the primary responsibility and rights to censorship within their own households. v Making and maintaining strong relationships with parents and community members is essential to the success of children’s freedom to read. “We tolerate differing opinions not because we endorse them but because we wish to remain free to express our own. Intolerance of differing views in children's books easily leads to vigilante tactics, censorship and the suppression of the imagination” (Saltman, 1998).

Works Cited Blair, L. (1996). Strategies for Dealing with Censorship. Art Education, 49(5), pp. 57 -61. Retrieved from http: //www. jstor. org/stable/3193612 Challenges by reason, initiator, and institution for 1990 -1999 and 2000 -2009. American Library Association. (1996 -2013). Retrieved from http: //www. ala. org/bbooks/frequentlychallengedbooks/statistics Foerstel, H. N. (1994). Banned in the U. S. A. : a reference guide to book censorship in schools and public libraries. Westport, Conn. Greenwood Press. Hunt, L. , Wachsmann, M. (2012). Does Labeling Children’s Books Constitute Censorship? Taking Issues. 52(2), pp. 90 -92. Kidd, K. (2009). “Not Censorship but Selection”: Censorship and/as Prizing. Children’s Literature in Education. 40, 197 -216. Lehr, S. S. (2012). Literacy, Literature, and Censorship: The High Cost of No Child Left Behind. Education Studies Department, Skidmore College. 87(1), pp. 25 -34.

Works Cited (cont’d) Mac. Leod, A. S. (1983). Censorship and Children’s Literature. The Library Quarterly. 53(1), pp. 26 -38. Retrieved from http: //www. jstor. org/stable/4307574 Mc. Cracken, N. (1994). Censorship Matters. The Censorship Connection. (21)2. Retrieved from http: //scholar. lib. vt. edu/ejournals/ALAN/winter 94/Cen. CONN. html Saltman, J. (1998). Censoring the Imagination: Challenges to Children’s Books. Emergency Librarian. 25(3). Swiderek, B. (1996). Censorship. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy. 39(7), pp. 592 - 594. Retrieved from http: //www. jstor. org/stable/40017469 Winch, C. (2006). Should Children’s Books be Censored? 16(1), pp. 41 -51. Retrieved from http: //dx. doi. org/10. 1080/0140672930160107