Cell Cycle by Tri Suwandi S Pd M

Cell Cycle by: Tri Suwandi, S. Pd. , M. Sc. suwandi. 3 su@gmail. com

Objectives: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Describe the role of cell division. Describe the structure of eukaryotic chromosomes. Describe the eukaryotic cell cycle. Describe the events that take place during interphase. Describe the phases of mitosis. Distinguish between mitosis and meiosis. Explain the importance of mitotic spindle. Compare cytokinesis in plants, animals, and other organism.

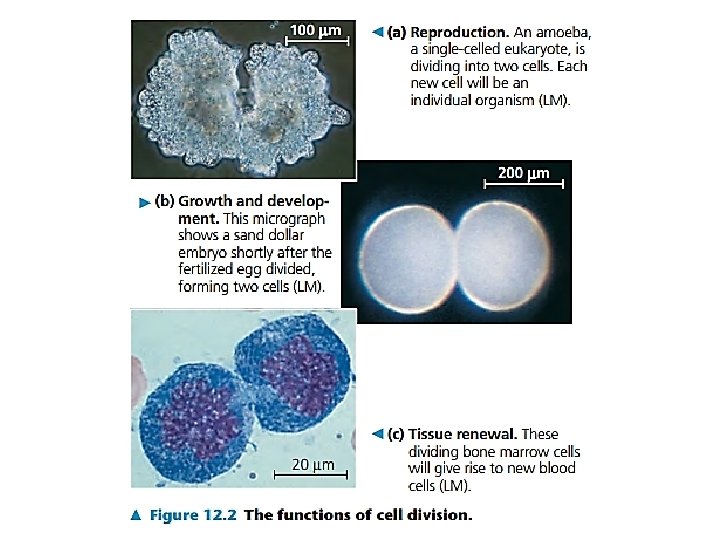

Overview: The Key Roles of Cell Division • The ability of organisms to produce more of their own kind best distinguishes living things from nonliving matter • The continuity of life is based on the reproduction of cells, or cell division • In unicellular organisms, division of one cell reproduces the entire organism • Multicellular organisms depend on cell division for – Development from a fertilized cell – Growth – Repair • Cell division is an integral part of the cell cycle, the life of a cell from formation to its own division © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

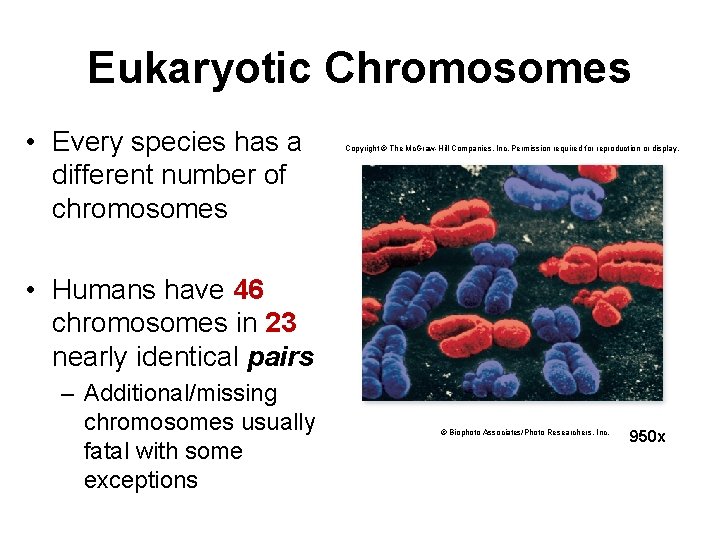

Eukaryotic Chromosomes • Every species has a different number of chromosomes Copyright © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, Inc. Permission required for reproduction or display. • Humans have 46 chromosomes in 23 nearly identical pairs – Additional/missing chromosomes usually fatal with some exceptions © Biophoto Associates/Photo Researchers, Inc. 950 x

Chromatin: Chromosomes Composition • Chromosomes are composed of chromatin – complex of DNA and protein • Typical human chromosome 140 million nucleotides long • Over 2 meters of DNA inside a diploid human nucleus. • 2 general classifications of chromatin: – Heterochromatin – not expressed – Euchromatin – expressed

Chromatin: Chromosomes Composition Heterochromatin vs. Euchromatin http: //www. histology. leeds. ac. uk/cell/nucleus. php 7

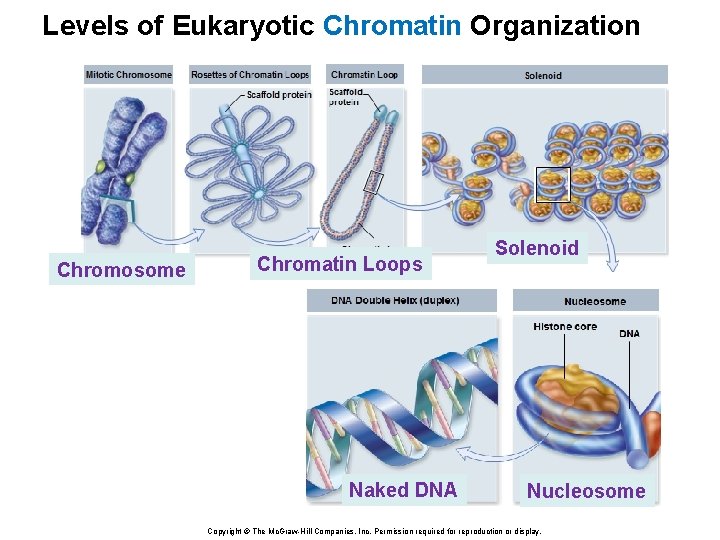

Levels of Eukaryotic Chromatin Organization Chromosome Chromatin Loops Naked DNA Solenoid Nucleosome Copyright © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, Inc. Permission required for reproduction or display.

Concept 12. 1: Most cell division results in genetically identical daughter cells • Most cell division results in daughter cells with identical genetic information, DNA • The exception is meiosis, a special type of division that can produce sperm and egg cells © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

Cellular Organization of the Genetic Material • All the DNA in a cell constitutes the cell’s genome • A genome can consist of a single DNA molecule (common in prokaryotic cells) or a number of DNA molecules (common in eukaryotic cells) • DNA molecules in a cell are packaged into chromosomes © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

• Eukaryotic chromosomes consist of chromatin, a complex of DNA and protein that condenses during cell division • Every eukaryotic species has a characteristic number of chromosomes in each cell nucleus • Somatic cells (nonreproductive cells) have two sets of chromosomes • Gametes (reproductive cells: sperm and eggs) have half as many chromosomes as somatic cells © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

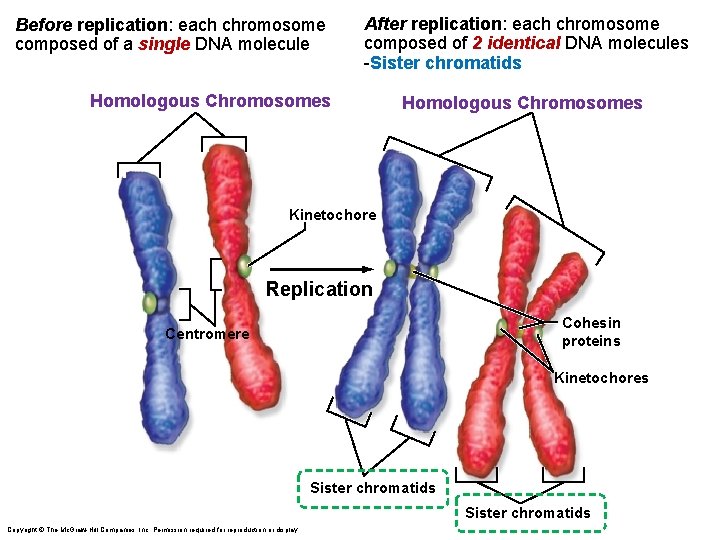

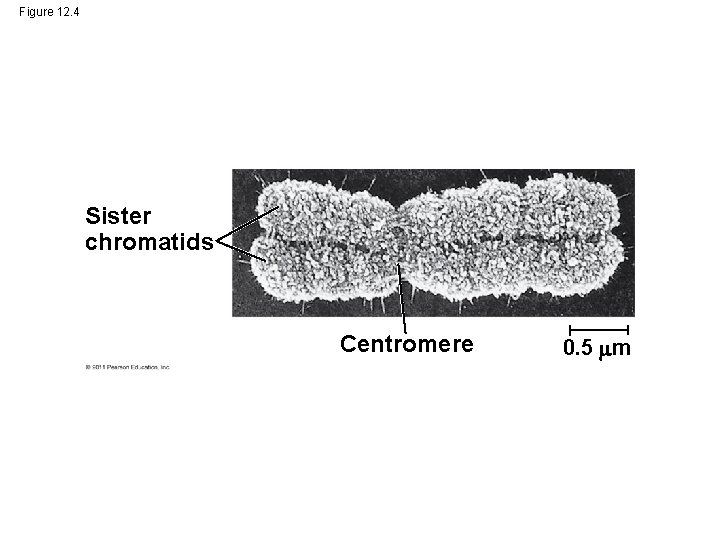

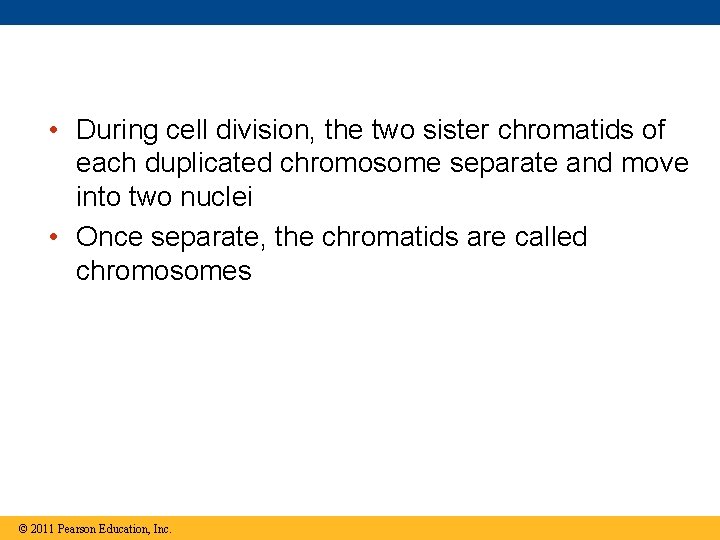

Distribution of Chromosomes During Eukaryotic Cell Division • In preparation for cell division, DNA is replicated and the chromosomes condense • Each duplicated chromosome has two sister chromatids (joined copies of the original chromosome), which separate during cell division • The centromere is the narrow “waist” of the duplicated chromosome, where the two chromatids are most closely attached © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

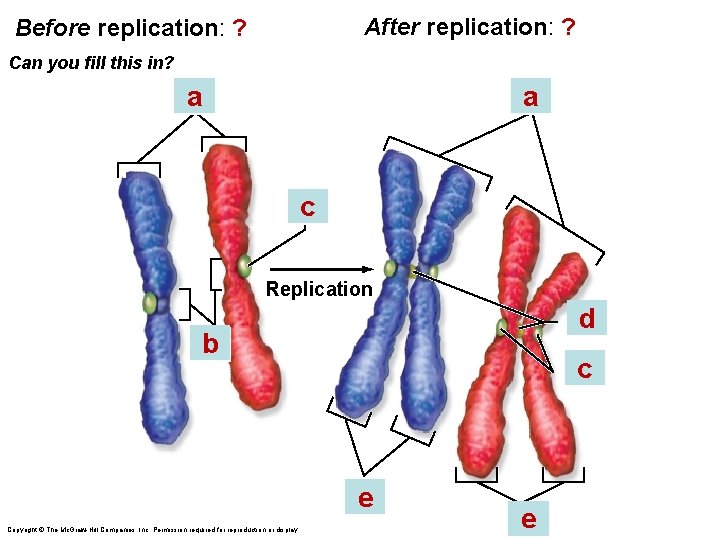

After replication: ? Before replication: ? Can you fill this in? a a c Replication d b c e Copyright © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, Inc. Permission required for reproduction or display. e

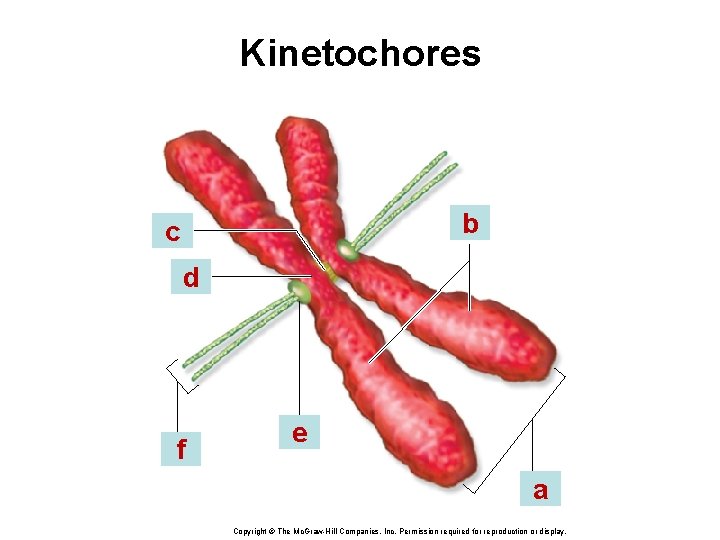

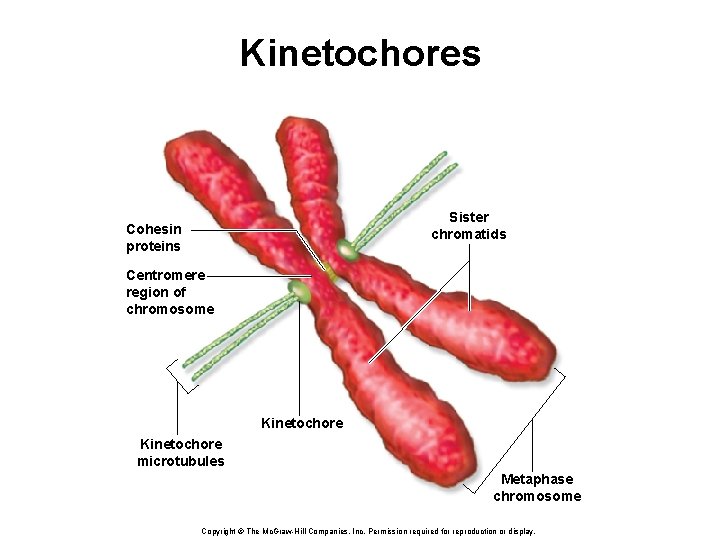

Before replication: each chromosome composed of a single DNA molecule After replication: each chromosome composed of 2 identical DNA molecules -Sister chromatids Homologous Chromosomes Kinetochore Replication Cohesin proteins Centromere Kinetochores Sister chromatids Copyright © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, Inc. Permission required for reproduction or display.

Figure 12. 4 Sister chromatids Centromere 0. 5 m

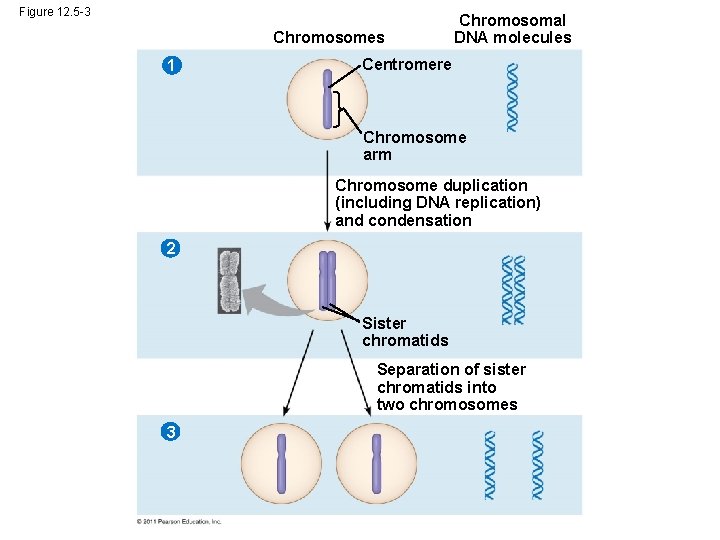

• During cell division, the two sister chromatids of each duplicated chromosome separate and move into two nuclei • Once separate, the chromatids are called chromosomes © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

Figure 12. 5 -3 Chromosomes 1 Chromosomal DNA molecules Centromere Chromosome arm Chromosome duplication (including DNA replication) and condensation 2 Sister chromatids Separation of sister chromatids into two chromosomes 3

• Eukaryotic cell division consists of – Mitosis, the division of the genetic material in the nucleus – Cytokinesis, the division of the cytoplasm • Gametes are produced by a variation of cell division called meiosis • Meiosis yields nonidentical daughter cells that have only one set of chromosomes, half as many as the parent cell © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

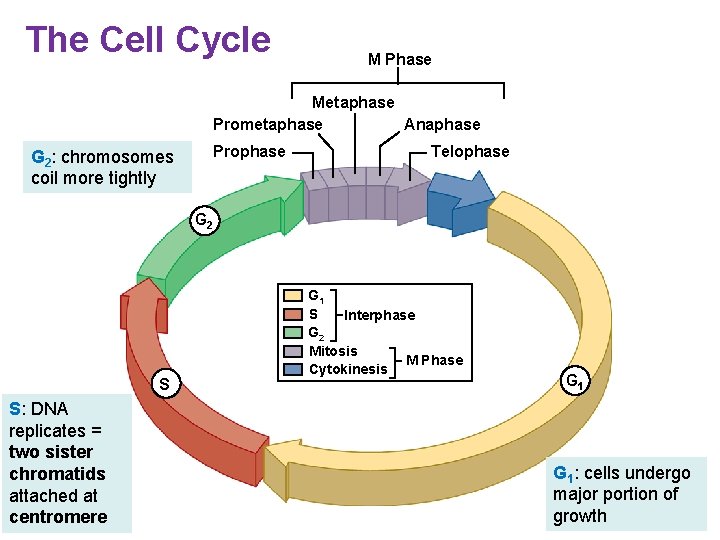

Phases of the Cell Cycle • The cell cycle consists of – Mitotic (M) phase (mitosis and cytokinesis) – Interphase (cell growth and copying of chromosomes in preparation for cell division) • Interphase (about 90% of the cell cycle) can be divided into subphases – G 1 phase (“first gap”) – S phase (“synthesis”) – G 2 phase (“second gap”) • The cell grows during all three phases, but chromosomes are duplicated only during the S phase © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

The Cell Cycle M Phase Metaphase Prometaphase Anaphase G 2: chromosomes coil more tightly Prophase Telophase G 2 S S: DNA replicates = two sister chromatids attached at centromere G 1 S Interphase G 2 Mitosis M Phase Cytokinesis G 1: cells undergo major portion of growth

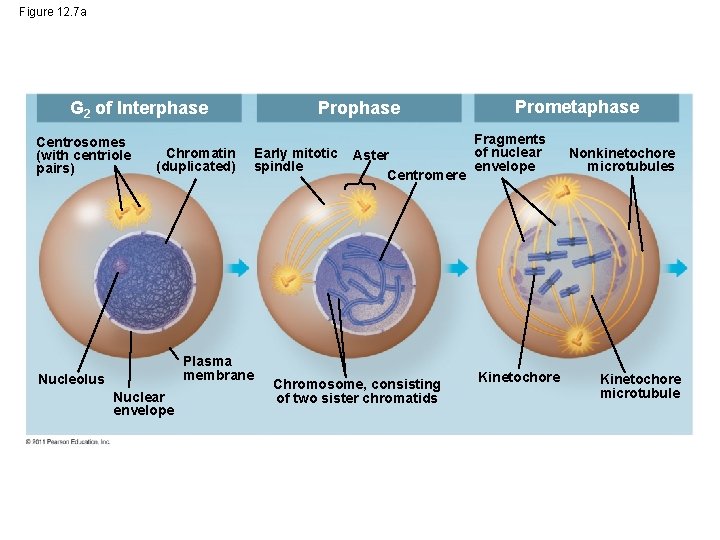

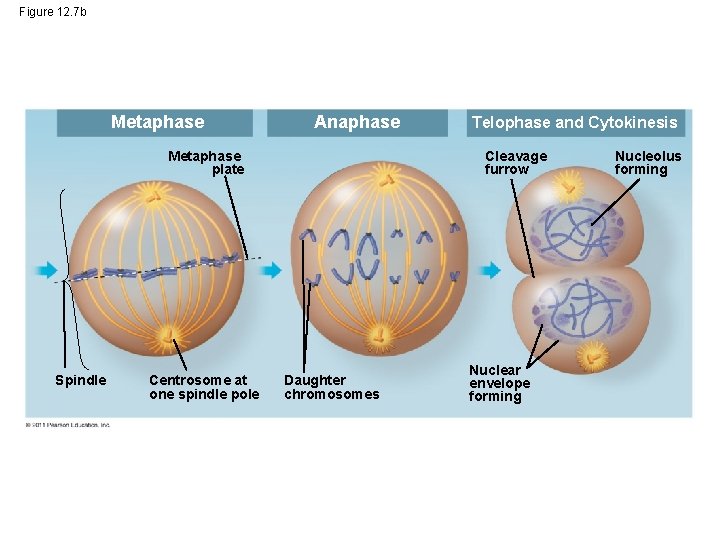

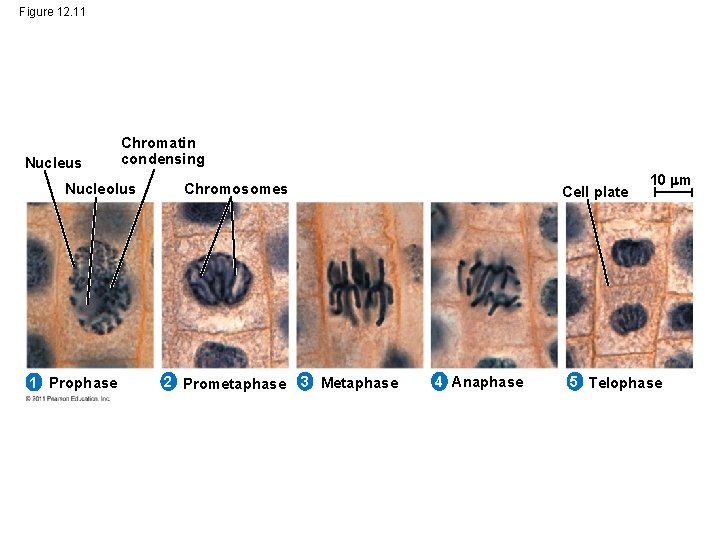

• Mitosis is conventionally divided into five phases – – – Prophase Prometaphase Metaphase Anaphase Telophase • Cytokinesis overlaps the latter stages of mitosis © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

Figure 12. 7 a G 2 of Interphase Centrosomes (with centriole pairs) Chromatin (duplicated) Prophase Early mitotic spindle Plasma membrane Nucleolus Nuclear envelope Prometaphase Fragments of nuclear Aster envelope Centromere Chromosome, consisting of two sister chromatids Kinetochore Nonkinetochore microtubules Kinetochore microtubule

Figure 12. 7 b Metaphase Anaphase Metaphase plate Spindle Centrosome at one spindle pole Telophase and Cytokinesis Cleavage furrow Daughter chromosomes Nuclear envelope forming Nucleolus forming

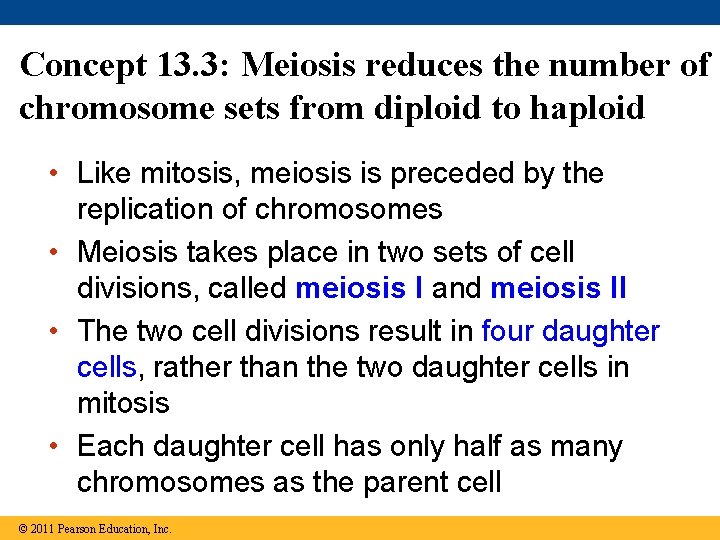

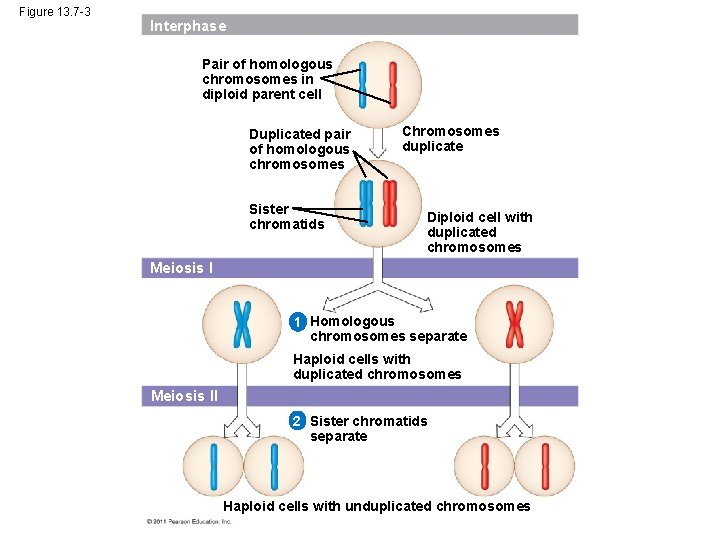

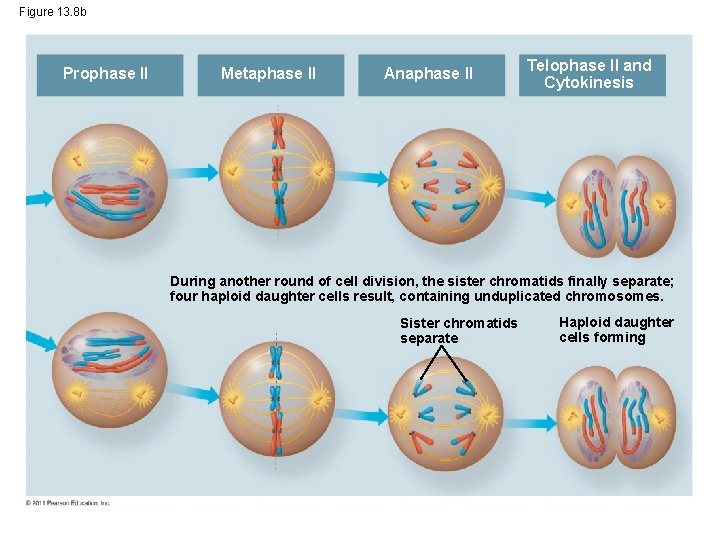

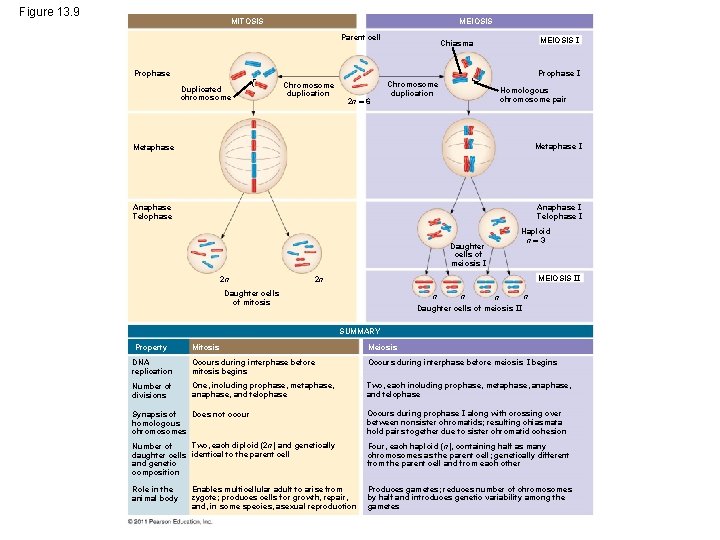

Concept 13. 3: Meiosis reduces the number of chromosome sets from diploid to haploid • Like mitosis, meiosis is preceded by the replication of chromosomes • Meiosis takes place in two sets of cell divisions, called meiosis I and meiosis II • The two cell divisions result in four daughter cells, rather than the two daughter cells in mitosis • Each daughter cell has only half as many chromosomes as the parent cell © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

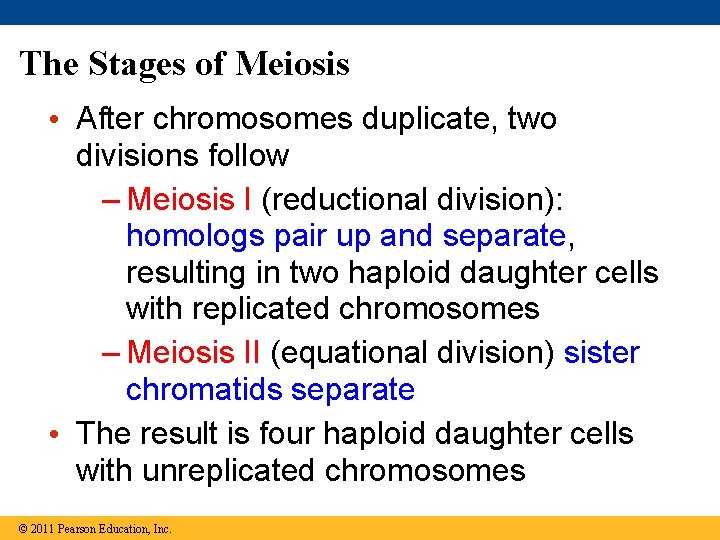

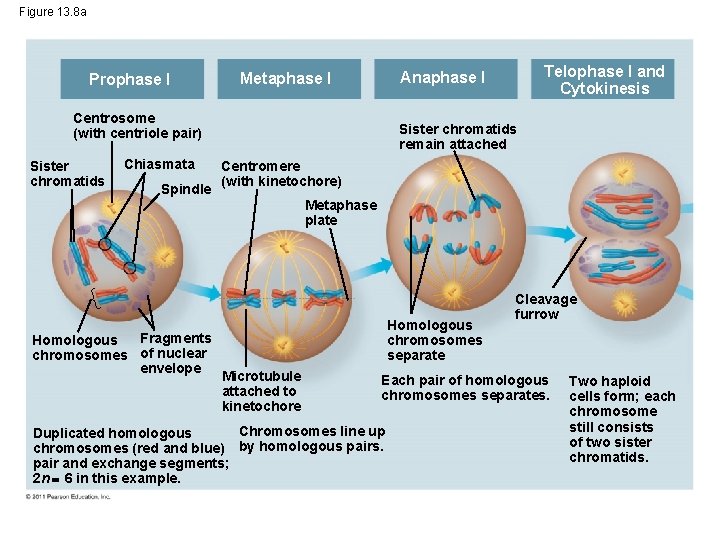

The Stages of Meiosis • After chromosomes duplicate, two divisions follow – Meiosis I (reductional division): homologs pair up and separate, resulting in two haploid daughter cells with replicated chromosomes – Meiosis II (equational division) sister chromatids separate • The result is four haploid daughter cells with unreplicated chromosomes © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

Figure 13. 7 -3 Interphase Pair of homologous chromosomes in diploid parent cell Duplicated pair of homologous chromosomes Sister chromatids Chromosomes duplicate Diploid cell with duplicated chromosomes Meiosis I 1 Homologous chromosomes separate Haploid cells with duplicated chromosomes Meiosis II 2 Sister chromatids separate Haploid cells with unduplicated chromosomes

• Meiosis I is preceded by interphase, when the chromosomes are duplicated to form sister chromatids • The sister chromatids are genetically identical and joined at the centromere • The single centrosome replicates, forming two centrosomes © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

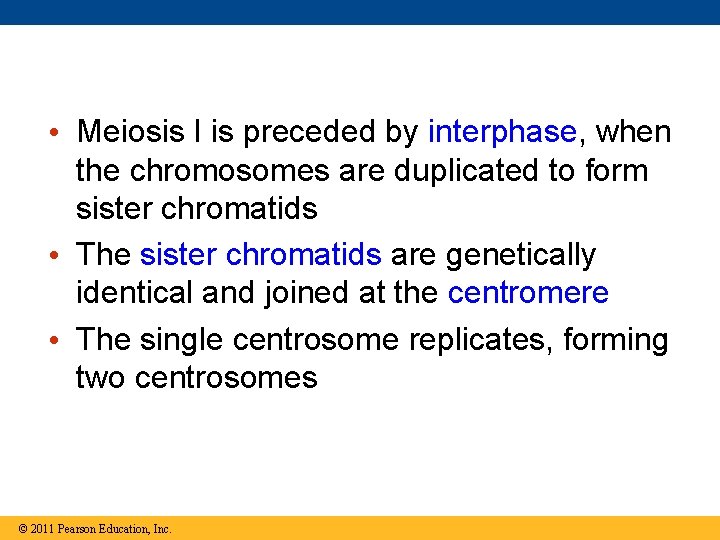

Figure 13. 8 a Prophase I Centrosome (with centriole pair) Sister chromatids Chiasmata Spindle Telophase I and Cytokinesis Anaphase I Metaphase I Sister chromatids remain attached Centromere (with kinetochore) Metaphase plate Fragments Homologous chromosomes of nuclear envelope Homologous chromosomes separate Microtubule attached to kinetochore Cleavage furrow Each pair of homologous chromosomes separates. Chromosomes line up Duplicated homologous chromosomes (red and blue) by homologous pairs. pair and exchange segments; 2 n 6 in this example. Two haploid cells form; each chromosome still consists of two sister chromatids.

Figure 13. 8 b Prophase II Metaphase II Anaphase II Telophase II and Cytokinesis During another round of cell division, the sister chromatids finally separate; four haploid daughter cells result, containing unduplicated chromosomes. Sister chromatids separate Haploid daughter cells forming

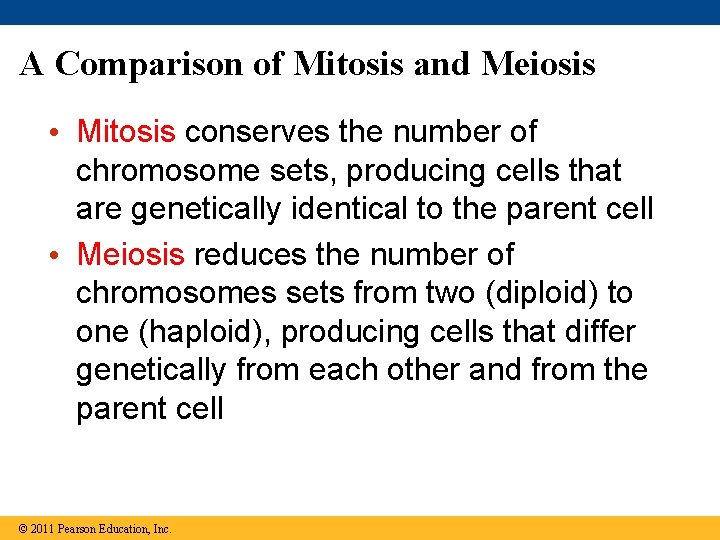

A Comparison of Mitosis and Meiosis • Mitosis conserves the number of chromosome sets, producing cells that are genetically identical to the parent cell • Meiosis reduces the number of chromosomes sets from two (diploid) to one (haploid), producing cells that differ genetically from each other and from the parent cell © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

Figure 13. 9 MITOSIS MEIOSIS Parent cell MEIOSIS I Chiasma Prophase I Duplicated chromosome Chromosome duplication 2 n 6 Chromosome duplication Homologous chromosome pair Metaphase I Anaphase Telophase Anaphase I Telophase I Daughter cells of meiosis I 2 n Haploid n 3 MEIOSIS II 2 n Daughter cells of mitosis n n Daughter cells of meiosis II SUMMARY Property Mitosis Meiosis DNA replication Occurs during interphase before mitosis begins Occurs during interphase before meiosis I begins Number of divisions One, including prophase, metaphase, and telophase Two, each including prophase, metaphase, and telophase Synapsis of Does not occur homologous chromosomes Occurs during prophase I along with crossing over between nonsister chromatids; resulting chiasmata hold pairs together due to sister chromatid cohesion Two, each diploid (2 n) and genetically Number of daughter cells identical to the parent cell and genetic composition Four, each haploid (n), containing half as many chromosomes as the parent cell; genetically different from the parent cell and from each other Role in the animal body Enables multicellular adult to arise from zygote; produces cells for growth, repair, and, in some species, asexual reproduction Produces gametes; reduces number of chromosomes by half and introduces genetic variability among the gametes

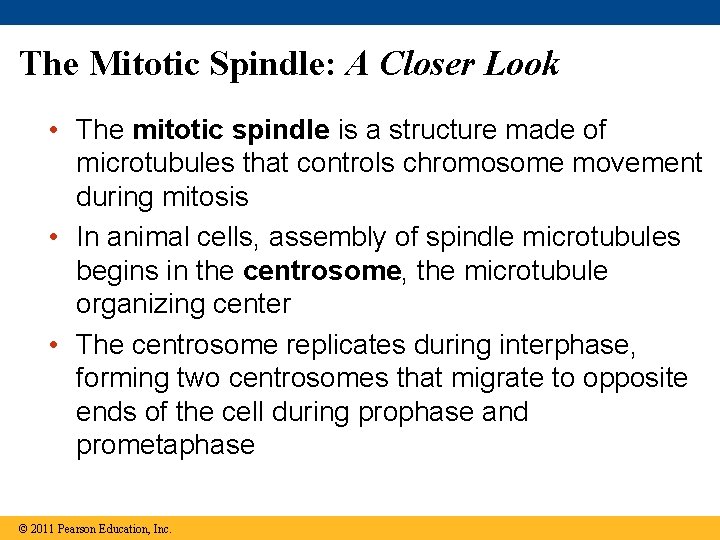

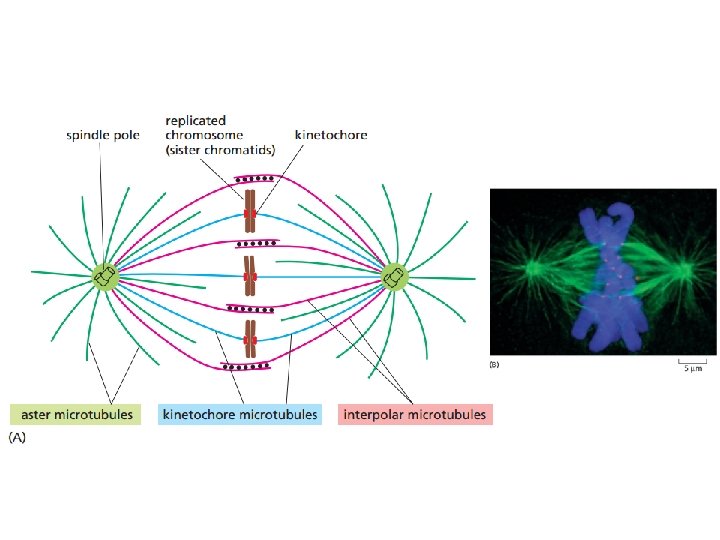

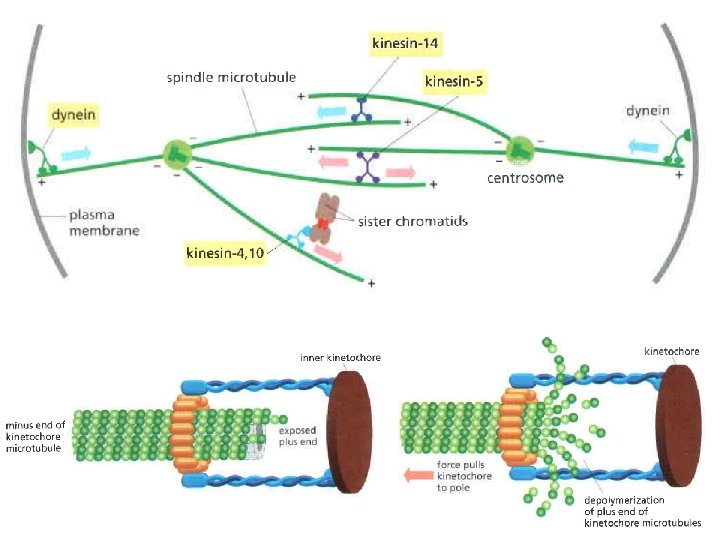

The Mitotic Spindle: A Closer Look • The mitotic spindle is a structure made of microtubules that controls chromosome movement during mitosis • In animal cells, assembly of spindle microtubules begins in the centrosome, the microtubule organizing center • The centrosome replicates during interphase, forming two centrosomes that migrate to opposite ends of the cell during prophase and prometaphase © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

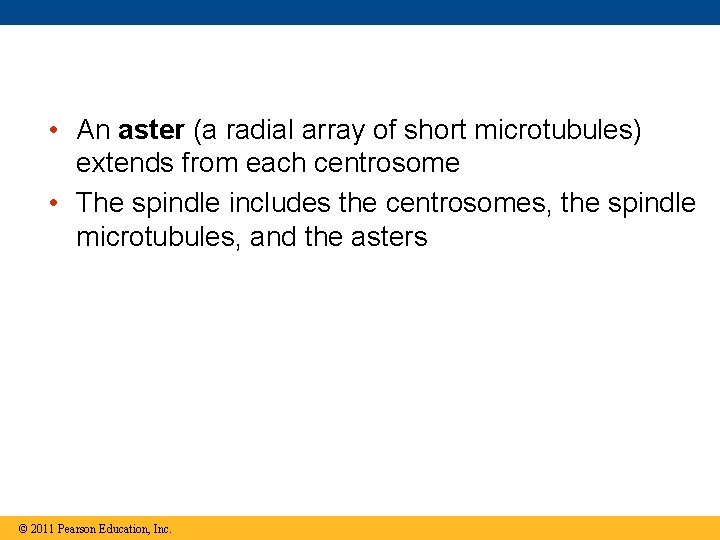

• An aster (a radial array of short microtubules) extends from each centrosome • The spindle includes the centrosomes, the spindle microtubules, and the asters © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

• During prometaphase, some spindle microtubules attach to the kinetochores of chromosomes and begin to move the chromosomes • Kinetochores are protein complexes associated with centromeres • At metaphase, the chromosomes are all lined up at the metaphase plate, an imaginary structure at the midway point between the spindle’s two poles © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

Kinetochores b c d f e a Copyright © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, Inc. Permission required for reproduction or display.

Kinetochores Sister chromatids Cohesin proteins Centromere region of chromosome Kinetochore microtubules Metaphase chromosome Copyright © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, Inc. Permission required for reproduction or display.

• In anaphase, sister chromatids separate and move along the kinetochore microtubules toward opposite ends of the cell • The microtubules shorten by depolymerizing at their kinetochore ends © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

• Nonkinetochore microtubules from opposite poles overlap and push against each other, elongating the cell • In telophase, genetically identical daughter nuclei form at opposite ends of the cell • Cytokinesis begins during anaphase or telophase and the spindle eventually disassembles © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

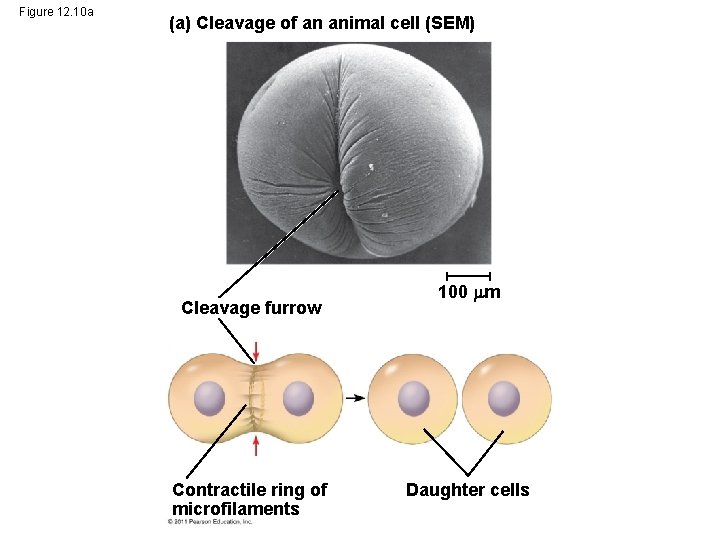

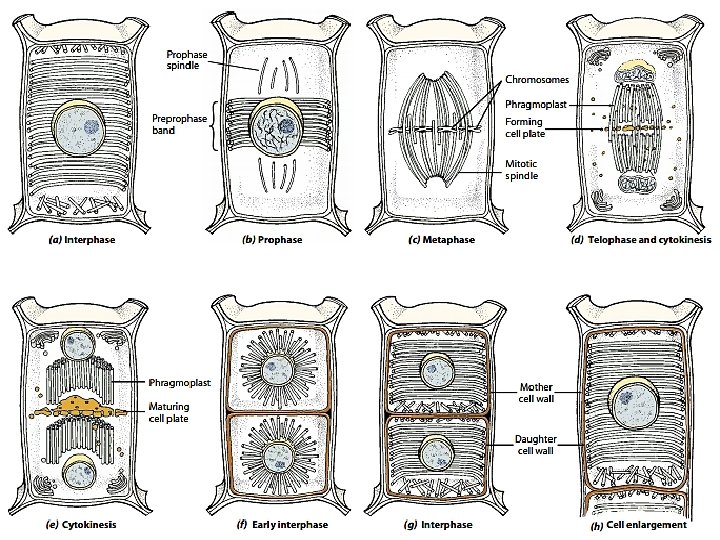

Cytokinesis: A Closer Look • In animal cells, cytokinesis occurs by a process known as cleavage, forming a cleavage furrow • In plant cells, a cell plate forms during cytokinesis © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

Figure 12. 10 a (a) Cleavage of an animal cell (SEM) Cleavage furrow Contractile ring of microfilaments 100 m Daughter cells

Figure 12. 11 Nucleus Chromatin condensing Nucleolus 1 Prophase Chromosomes 2 Prometaphase 3 Metaphase Cell plate 4 Anaphase 10 m 5 Telophase

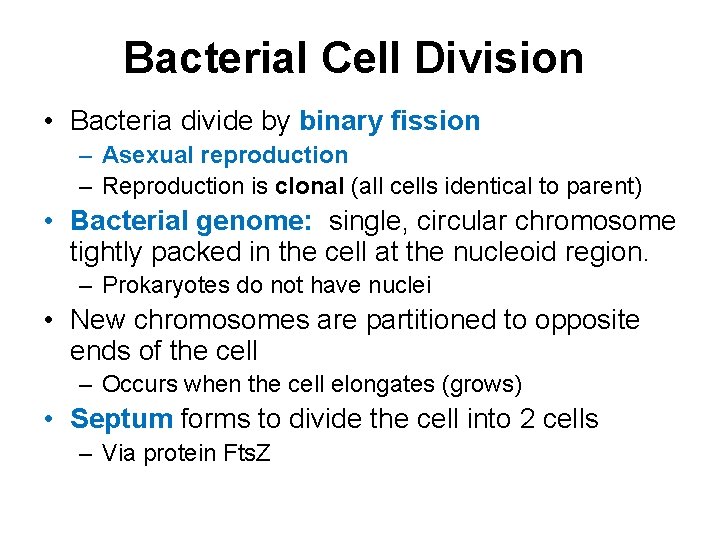

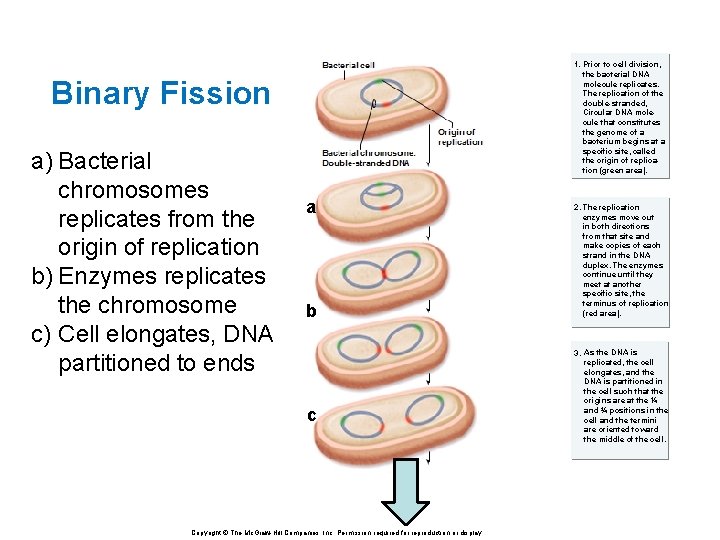

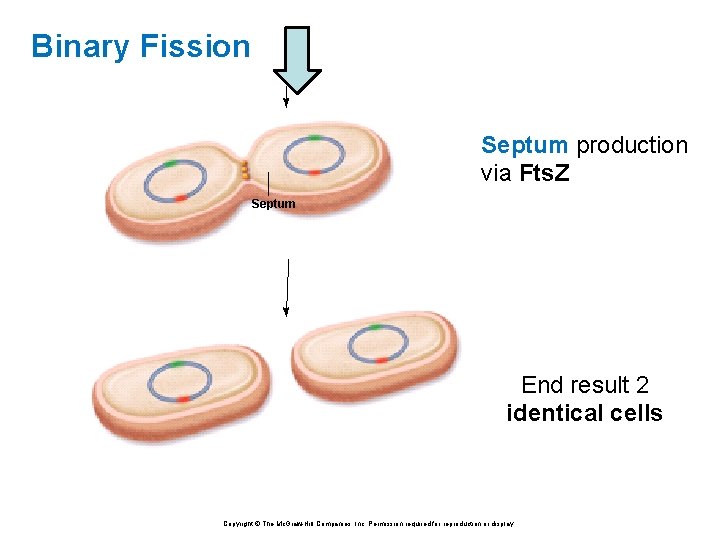

Bacterial Cell Division • Bacteria divide by binary fission – Asexual reproduction – Reproduction is clonal (all cells identical to parent) • Bacterial genome: single, circular chromosome tightly packed in the cell at the nucleoid region. – Prokaryotes do not have nuclei • New chromosomes are partitioned to opposite ends of the cell – Occurs when the cell elongates (grows) • Septum forms to divide the cell into 2 cells – Via protein Fts. Z

1. Prior to cell division, the bacterial DNA molecule replicates. The replication of the double-stranded, Circular DNA molecule that constitutes the genome of a bacterium begins at a specific site, called the origin of replication (green area). Binary Fission a) Bacterial chromosomes replicates from the origin of replication b) Enzymes replicates the chromosome c) Cell elongates, DNA partitioned to ends a b c Copyright © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, Inc. Permission required for reproduction or display. 2. The replication enzymes move out in both directions from that site and make copies of each strand in the DNA duplex. The enzymes continue until they meet at another specific site, the terminus of replication (red area). 3. As the DNA is replicated, the cell elongates, and the DNA is partitioned in the cell such that the origins are at the ¼ and ¾ positions in the cell and the termini are oriented toward the middle of the cell.

Binary Fission Septum production via Fts. Z Septum End result 2 identical cells Copyright © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, Inc. Permission required for reproduction or display.

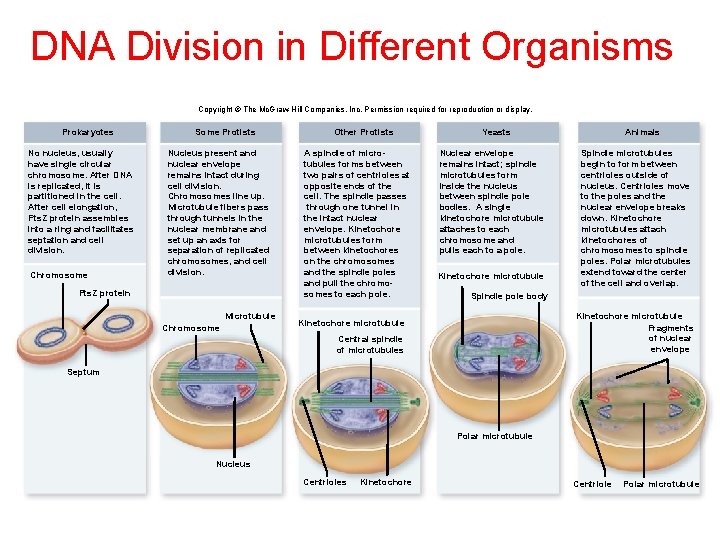

DNA Division in Different Organisms Copyright © The Mc. Graw-Hill Companies, Inc. Permission required for reproduction or display. Prokaryotes No nucleus, usually have single circular chromosome. After DNA is replicated, it is partitioned in the cell. After cell elongation, Fts. Z protein assembles into a ring and facilitates septation and cell division. Chromosome Some Protists Nucleus present and nuclear envelope remains intact during cell division. Chromosomes line up. Microtubule fibers pass through tunnels in the nuclear membrane and set up an axis for separation of replicated chromosomes, and cell division. Fts. Z protein Microtubule Chromosome Other Protists A spindle of microtubules forms between two pairs of centrioles at opposite ends of the cell. The spindle passes through one tunnel in the intact nuclear envelope. Kinetochore microtubules form between kinetochores on the chromosomes and the spindle poles and pull the chromosomes to each pole. Yeasts Nuclear envelope remains intact; spindle microtubules form inside the nucleus between spindle pole bodies. A single kinetochore microtubule attaches to each chromosome and pulls each to a pole. Kinetochore microtubule Animals Spindle microtubules begin to form between centrioles outside of nucleus. Centrioles move to the poles and the nuclear envelope breaks down. Kinetochore microtubules attach kinetochores of chromosomes to spindle poles. Polar microtubules extend toward the center of the cell and overlap. Spindle pole body Kinetochore microtubule Fragments of nuclear envelope Kinetochore microtubule Central spindle of microtubules Septum Polar microtubule Nucleus Centrioles Kinetochore Centriole Polar microtubule

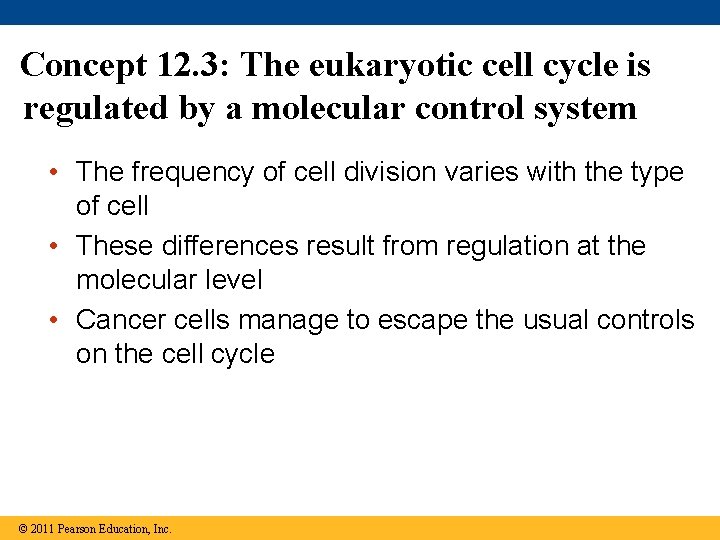

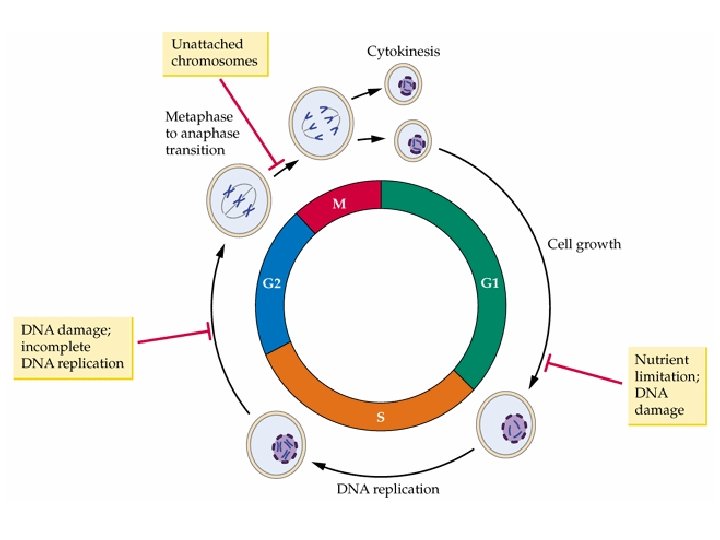

Concept 12. 3: The eukaryotic cell cycle is regulated by a molecular control system • The frequency of cell division varies with the type of cell • These differences result from regulation at the molecular level • Cancer cells manage to escape the usual controls on the cell cycle © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

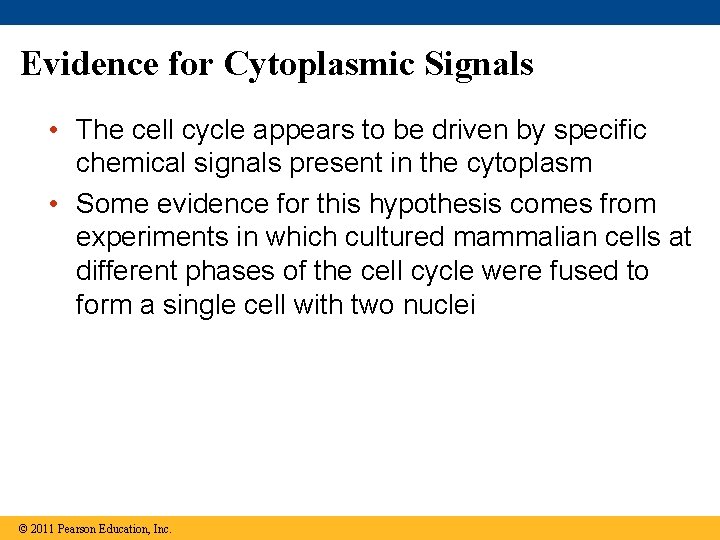

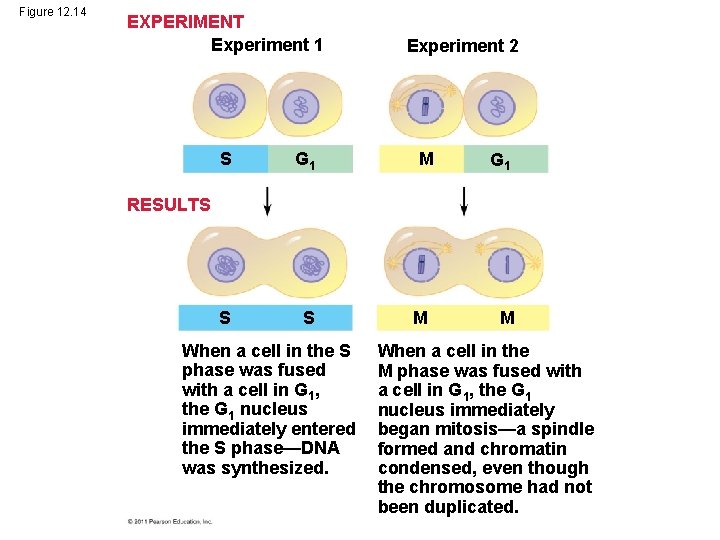

Evidence for Cytoplasmic Signals • The cell cycle appears to be driven by specific chemical signals present in the cytoplasm • Some evidence for this hypothesis comes from experiments in which cultured mammalian cells at different phases of the cell cycle were fused to form a single cell with two nuclei © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

Figure 12. 14 EXPERIMENT Experiment 1 S G 1 S S Experiment 2 M G 1 RESULTS When a cell in the S phase was fused with a cell in G 1, the G 1 nucleus immediately entered the S phase—DNA was synthesized. M M When a cell in the M phase was fused with a cell in G 1, the G 1 nucleus immediately began mitosis—a spindle formed and chromatin condensed, even though the chromosome had not been duplicated.

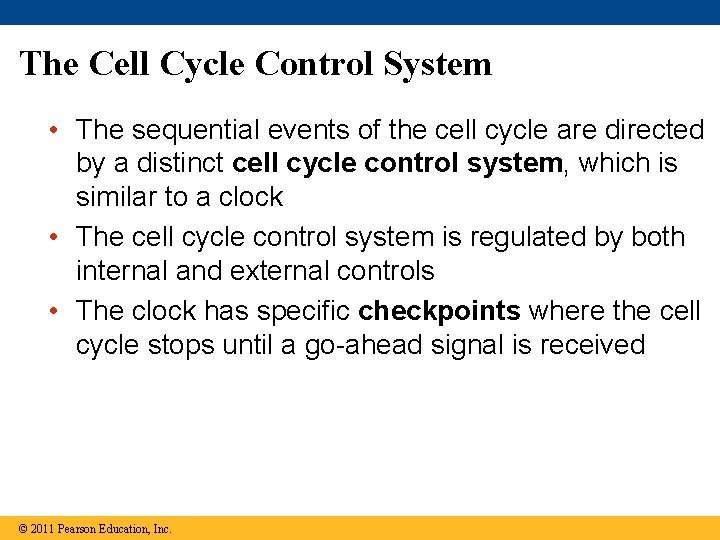

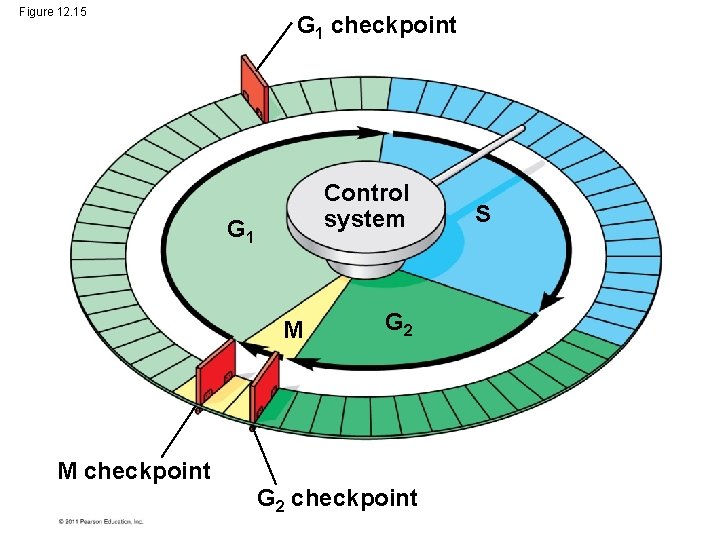

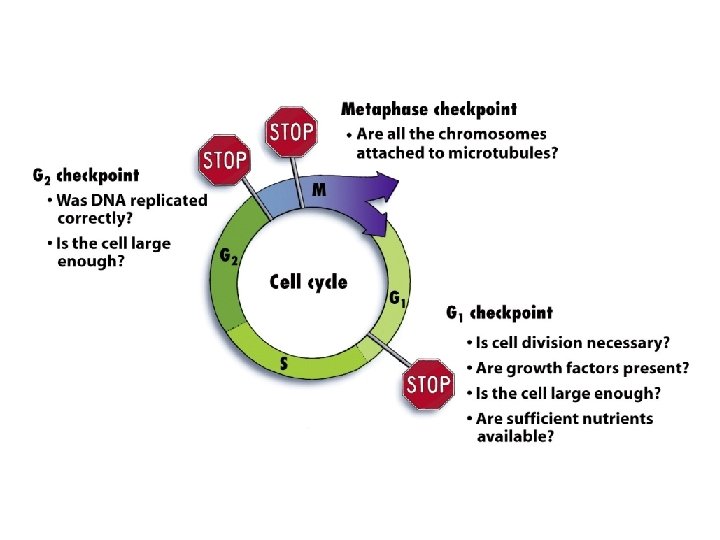

The Cell Cycle Control System • The sequential events of the cell cycle are directed by a distinct cell cycle control system, which is similar to a clock • The cell cycle control system is regulated by both internal and external controls • The clock has specific checkpoints where the cell cycle stops until a go-ahead signal is received © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

Figure 12. 15 G 1 checkpoint Control system G 1 M G 2 M checkpoint G 2 checkpoint S

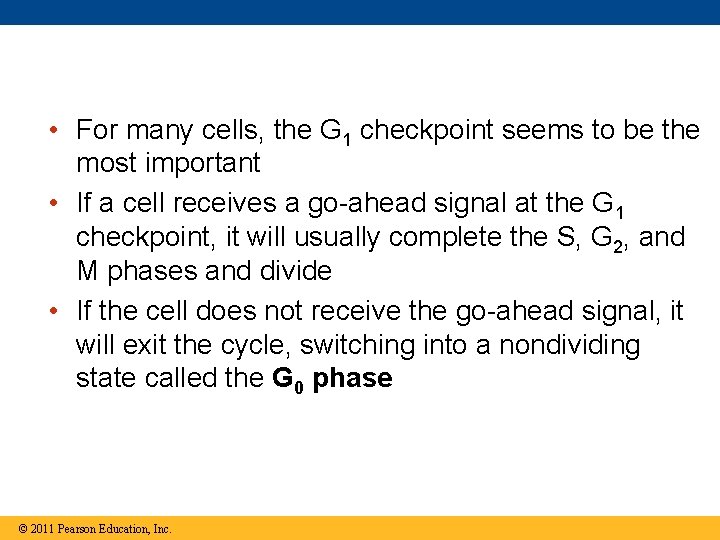

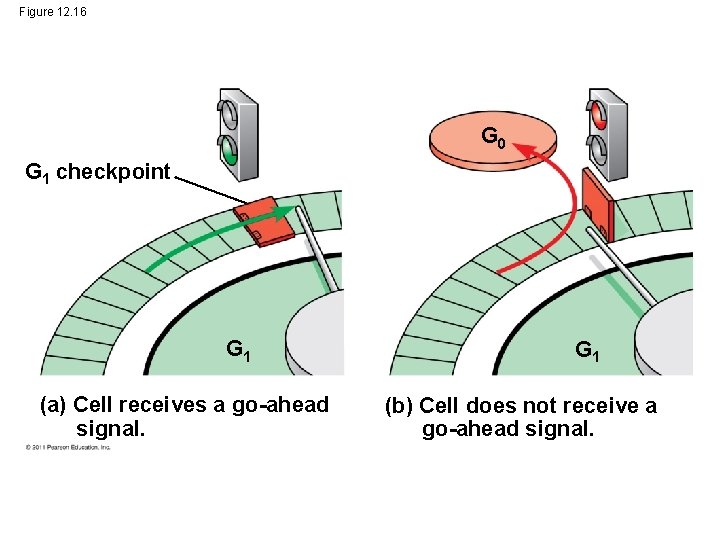

• For many cells, the G 1 checkpoint seems to be the most important • If a cell receives a go-ahead signal at the G 1 checkpoint, it will usually complete the S, G 2, and M phases and divide • If the cell does not receive the go-ahead signal, it will exit the cycle, switching into a nondividing state called the G 0 phase © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

Figure 12. 16 G 0 G 1 checkpoint G 1 (a) Cell receives a go-ahead signal. G 1 (b) Cell does not receive a go-ahead signal.

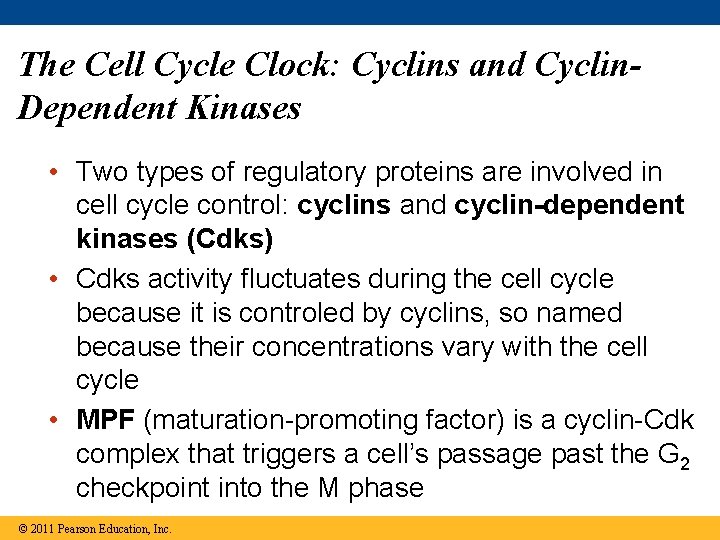

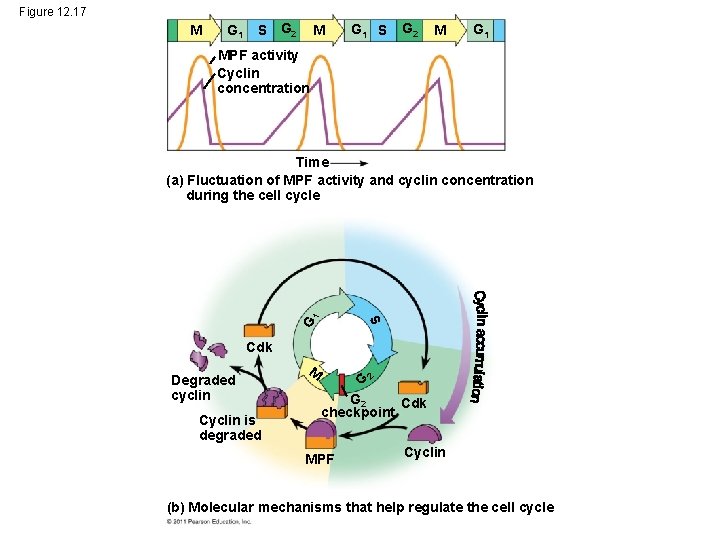

The Cell Cycle Clock: Cyclins and Cyclin. Dependent Kinases • Two types of regulatory proteins are involved in cell cycle control: cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks) • Cdks activity fluctuates during the cell cycle because it is controled by cyclins, so named because their concentrations vary with the cell cycle • MPF (maturation-promoting factor) is a cyclin-Cdk complex that triggers a cell’s passage past the G 2 checkpoint into the M phase © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

Figure 12. 17 M G 1 S G 2 M G 1 MPF activity Cyclin concentration G S 1 Time (a) Fluctuation of MPF activity and cyclin concentration during the cell cycle Cdk Cyclin is degraded 2 M G Degraded cyclin G 2 Cdk checkpoint MPF Cyclin (b) Molecular mechanisms that help regulate the cell cycle

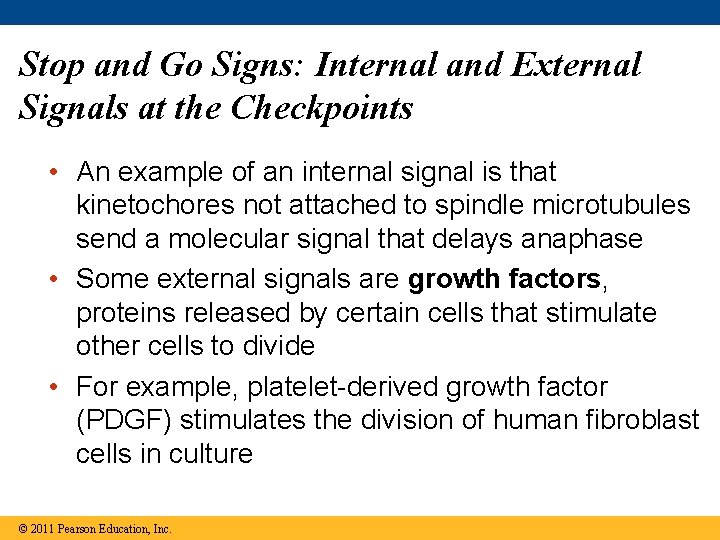

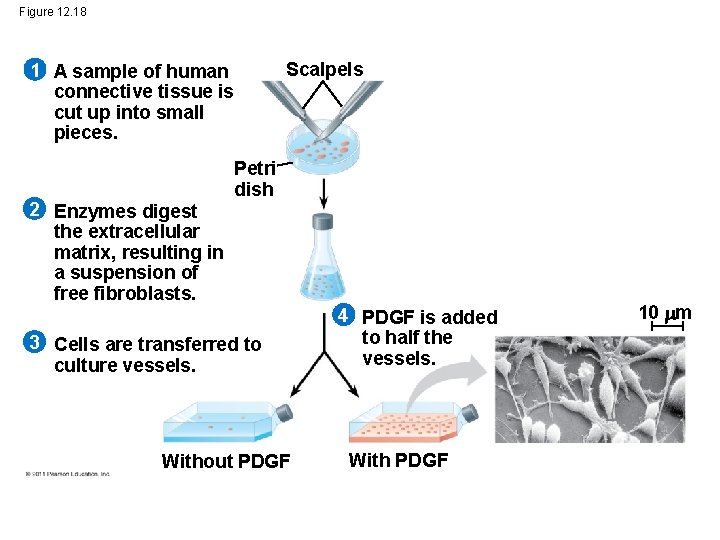

Stop and Go Signs: Internal and External Signals at the Checkpoints • An example of an internal signal is that kinetochores not attached to spindle microtubules send a molecular signal that delays anaphase • Some external signals are growth factors, proteins released by certain cells that stimulate other cells to divide • For example, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) stimulates the division of human fibroblast cells in culture © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

Figure 12. 18 Scalpels 1 A sample of human connective tissue is cut up into small pieces. 2 Enzymes digest the extracellular matrix, resulting in a suspension of free fibroblasts. Petri dish 3 Cells are transferred to culture vessels. Without PDGF 4 PDGF is added to half the vessels. With PDGF 10 m

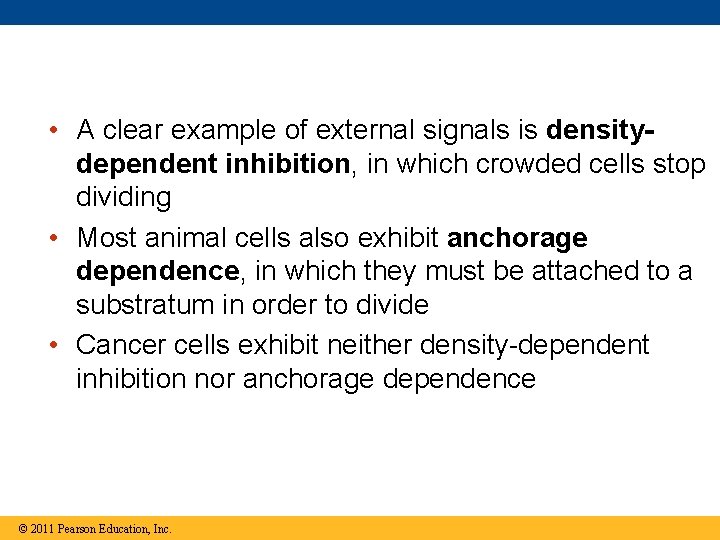

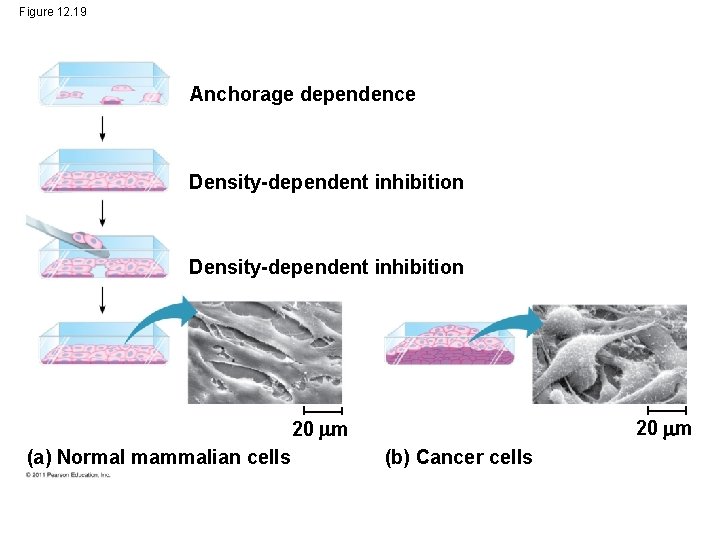

• A clear example of external signals is densitydependent inhibition, in which crowded cells stop dividing • Most animal cells also exhibit anchorage dependence, in which they must be attached to a substratum in order to divide • Cancer cells exhibit neither density-dependent inhibition nor anchorage dependence © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

Figure 12. 19 Anchorage dependence Density-dependent inhibition 20 m (a) Normal mammalian cells (b) Cancer cells

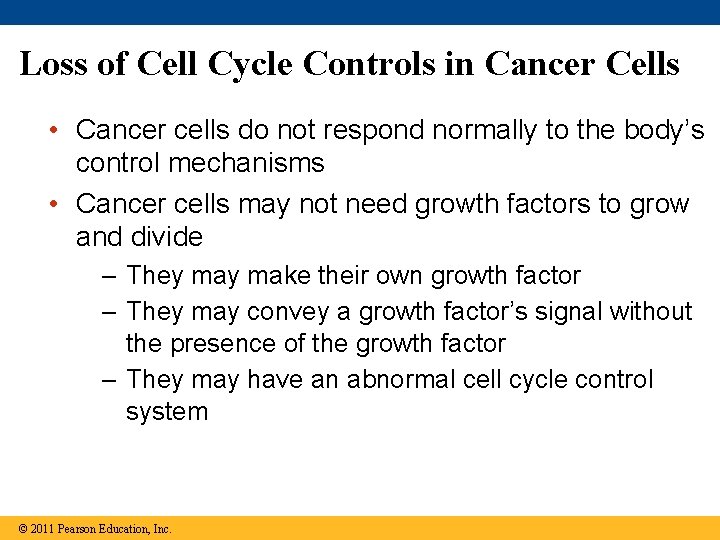

Loss of Cell Cycle Controls in Cancer Cells • Cancer cells do not respond normally to the body’s control mechanisms • Cancer cells may not need growth factors to grow and divide – They make their own growth factor – They may convey a growth factor’s signal without the presence of the growth factor – They may have an abnormal cell cycle control system © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

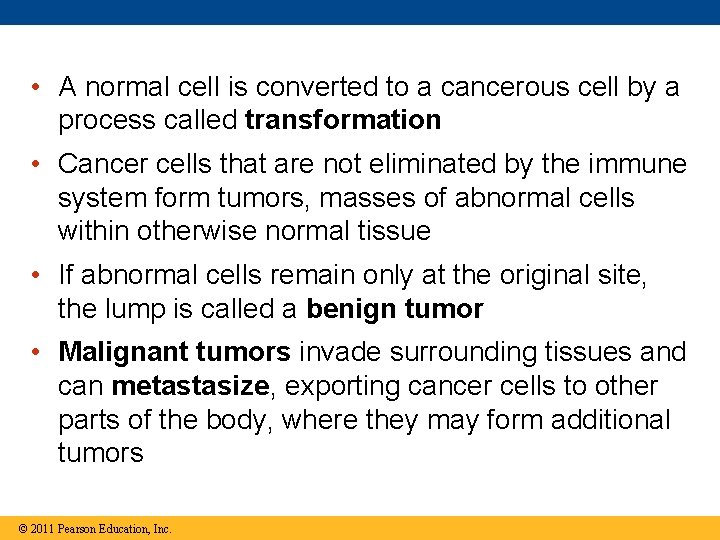

• A normal cell is converted to a cancerous cell by a process called transformation • Cancer cells that are not eliminated by the immune system form tumors, masses of abnormal cells within otherwise normal tissue • If abnormal cells remain only at the original site, the lump is called a benign tumor • Malignant tumors invade surrounding tissues and can metastasize, exporting cancer cells to other parts of the body, where they may form additional tumors © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

Concept 18. 5: Cancer results from genetic changes that affect cell cycle control • The gene regulation systems that go wrong during cancer are the very same systems involved in embryonic development © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

Types of Genes Associated with Cancer • Cancer can be caused by mutations to genes that regulate cell growth and division • Tumor viruses can cause cancer in animals including humans © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

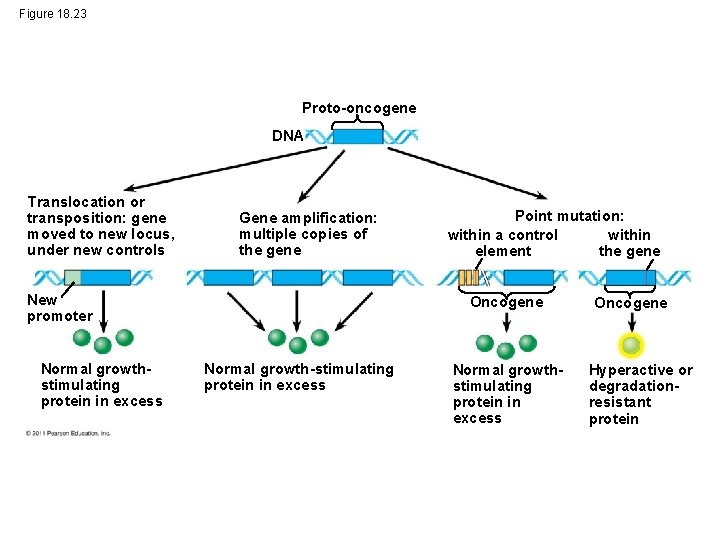

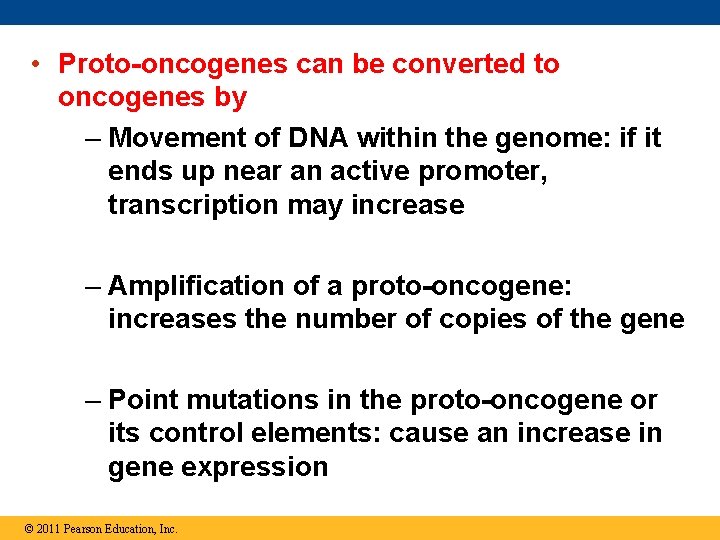

• Oncogenes are cancer-causing genes • Proto-oncogenes are the corresponding normal cellular genes that are responsible for normal cell growth and division • Conversion of a proto-oncogene to an oncogene can lead to abnormal stimulation of the cell cycle © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

Figure 18. 23 Proto-oncogene DNA Translocation or transposition: gene moved to new locus, under new controls Gene amplification: multiple copies of the gene New promoter Normal growthstimulating protein in excess Point mutation: within a control within element the gene Oncogene Normal growth-stimulating protein in excess Normal growthstimulating protein in excess Oncogene Hyperactive or degradationresistant protein

• Proto-oncogenes can be converted to oncogenes by – Movement of DNA within the genome: if it ends up near an active promoter, transcription may increase – Amplification of a proto-oncogene: increases the number of copies of the gene – Point mutations in the proto-oncogene or its control elements: cause an increase in gene expression © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

Tumor-Suppressor Genes • Tumor-suppressor genes help prevent uncontrolled cell growth • Mutations that decrease protein products of tumor-suppressor genes may contribute to cancer onset • Tumor-suppressor proteins – Repair damaged DNA – Control cell adhesion – Inhibit the cell cycle in the cell-signaling pathway © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

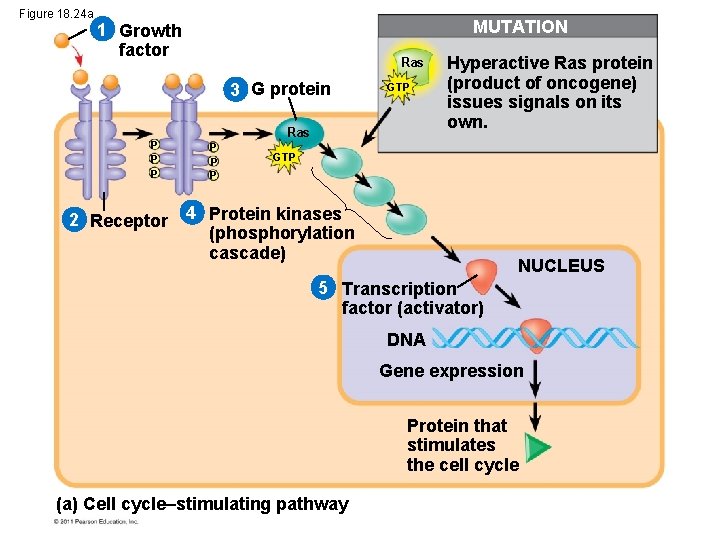

Interference with Normal Cell-Signaling Pathways • Mutations in the ras proto-oncogene and p 53 tumor-suppressor gene are common in human cancers • Mutations in the ras gene can lead to production of a hyperactive Ras protein and increased cell division © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

Figure 18. 24 a MUTATION 1 Growth factor Ras 3 G protein P P P 2 Receptor GTP Ras P P P Hyperactive Ras protein (product of oncogene) issues signals on its own. GTP 4 Protein kinases (phosphorylation cascade) NUCLEUS 5 Transcription factor (activator) DNA Gene expression Protein that stimulates the cell cycle (a) Cell cycle–stimulating pathway

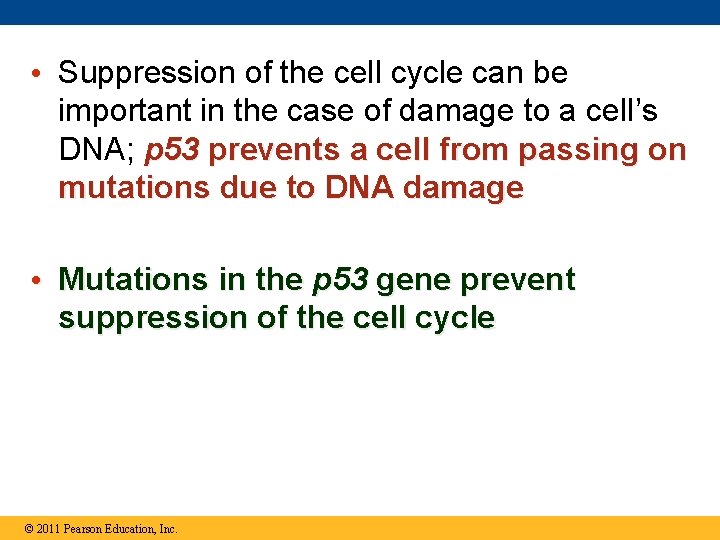

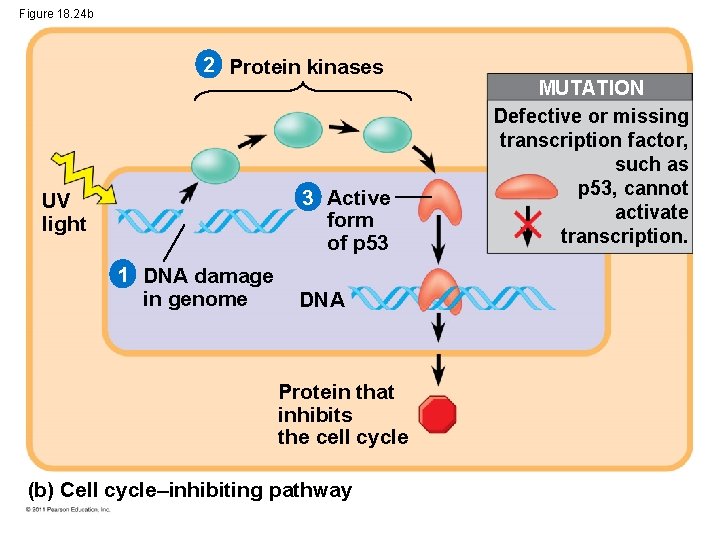

• Suppression of the cell cycle can be important in the case of damage to a cell’s DNA; p 53 prevents a cell from passing on mutations due to DNA damage • Mutations in the p 53 gene prevent suppression of the cell cycle © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

Figure 18. 24 b 2 Protein kinases 3 Active form of p 53 UV light 1 DNA damage in genome DNA Protein that inhibits the cell cycle (b) Cell cycle–inhibiting pathway MUTATION Defective or missing transcription factor, such as p 53, cannot activate transcription.

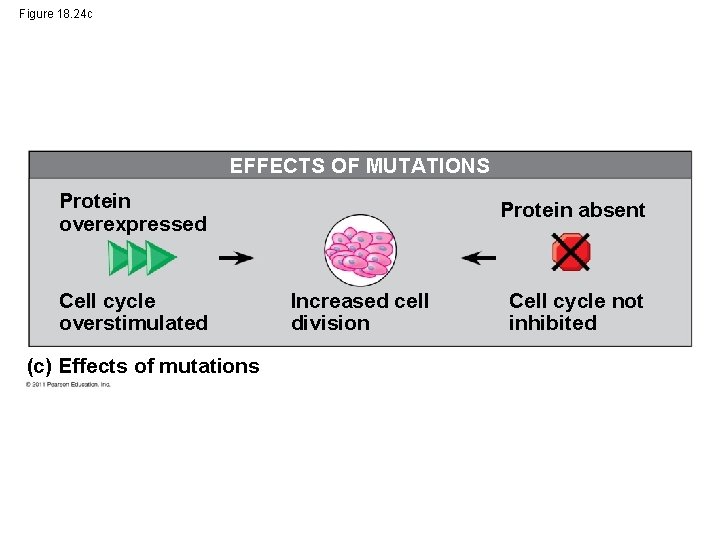

Figure 18. 24 c EFFECTS OF MUTATIONS Protein overexpressed Cell cycle overstimulated (c) Effects of mutations Protein absent Increased cell division Cell cycle not inhibited

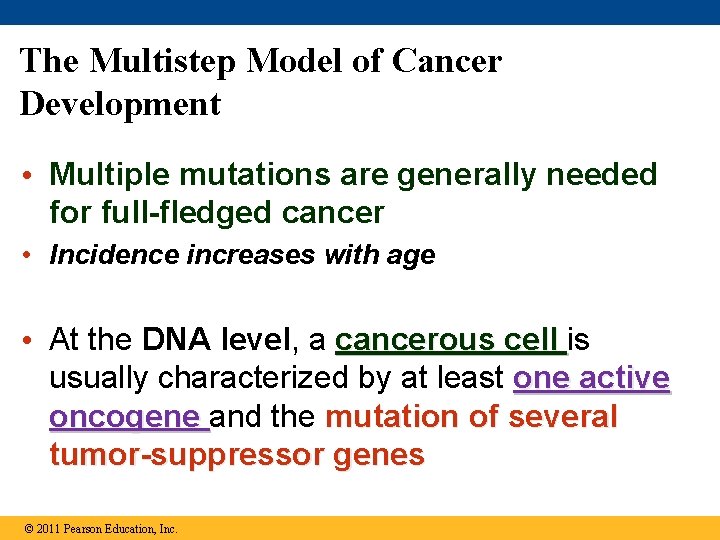

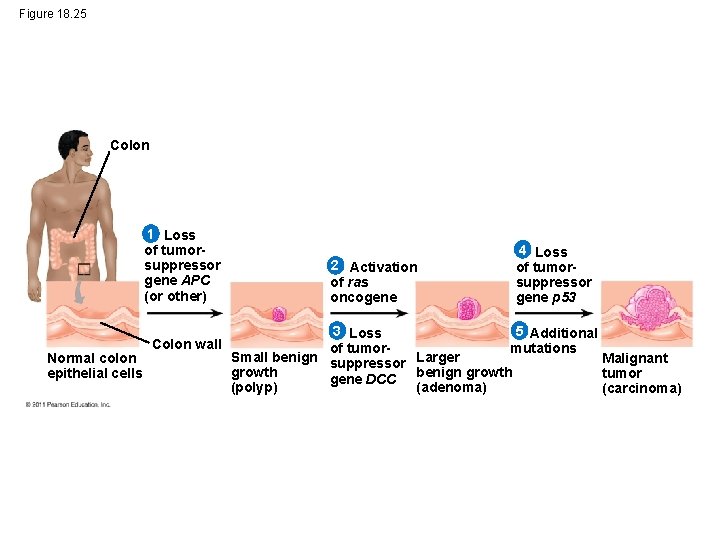

The Multistep Model of Cancer Development • Multiple mutations are generally needed for full-fledged cancer • Incidence increases with age • At the DNA level, a cancerous cell is usually characterized by at least one active oncogene and the mutation of several tumor-suppressor genes © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc.

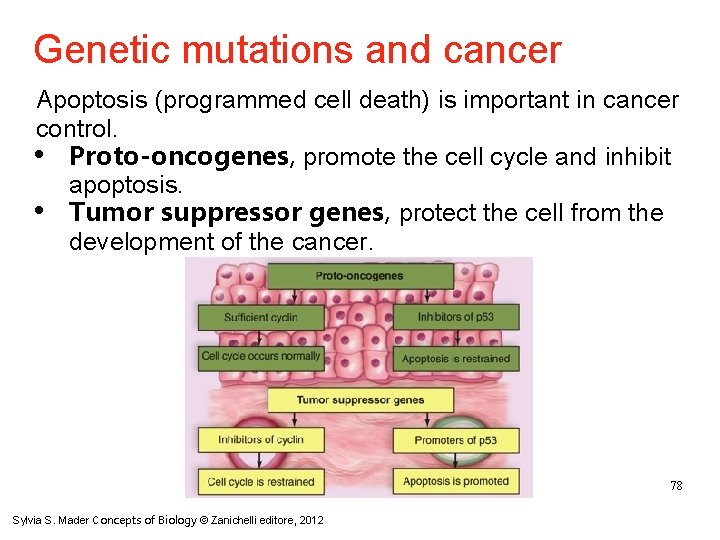

Genetic mutations and cancer Apoptosis (programmed cell death) is important in cancer control. • Proto-oncogenes, promote the cell cycle and inhibit apoptosis. • Tumor suppressor genes, protect the cell from the development of the cancer. 78 Sylvia S. Mader Concepts of Biology © Zanichelli editore, 2012

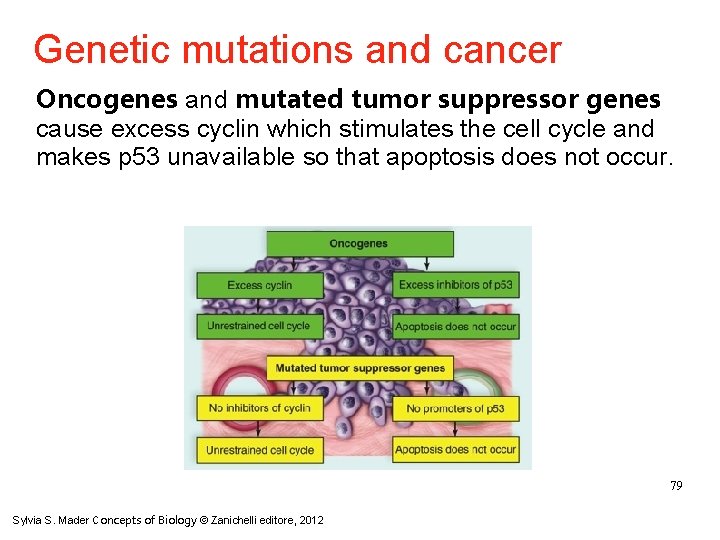

Genetic mutations and cancer Oncogenes and mutated tumor suppressor genes cause excess cyclin which stimulates the cell cycle and makes p 53 unavailable so that apoptosis does not occur. 79 Sylvia S. Mader Concepts of Biology © Zanichelli editore, 2012

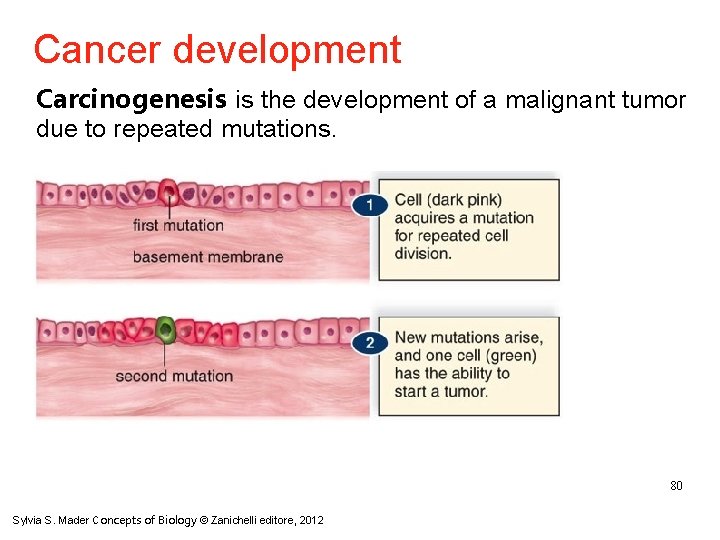

Cancer development Carcinogenesis is the development of a malignant tumor due to repeated mutations. 80 Sylvia S. Mader Concepts of Biology © Zanichelli editore, 2012

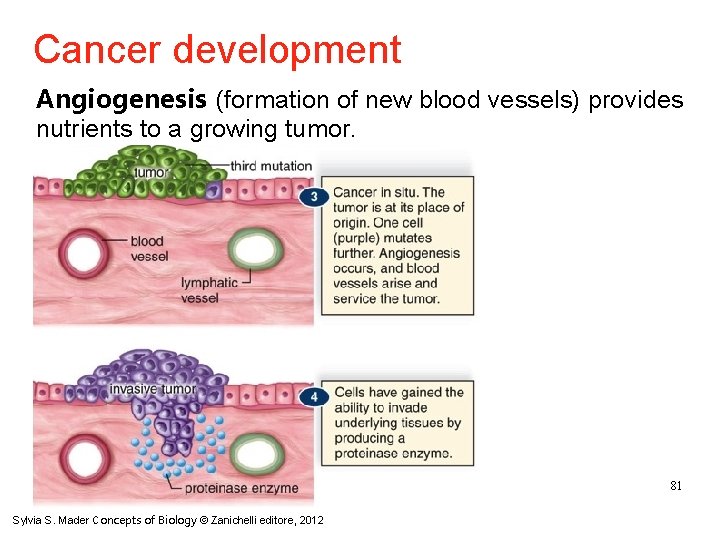

Cancer development Angiogenesis (formation of new blood vessels) provides nutrients to a growing tumor. 81 Sylvia S. Mader Concepts of Biology © Zanichelli editore, 2012

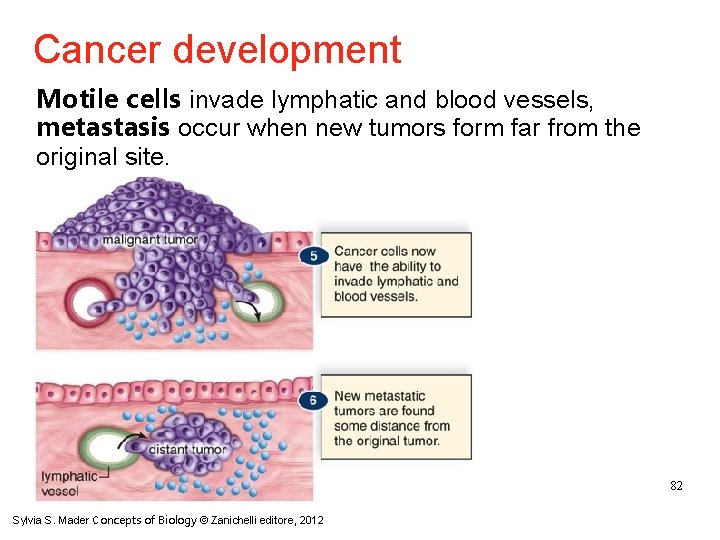

Cancer development Motile cells invade lymphatic and blood vessels, metastasis occur when new tumors form far from the original site. 82 Sylvia S. Mader Concepts of Biology © Zanichelli editore, 2012

Figure 18. 25 Colon 1 Loss of tumorsuppressor gene APC (or other) Normal colon epithelial cells Colon wall 2 Activation of ras oncogene 4 Loss of tumorsuppressor gene p 53 3 Loss 5 Additional mutations of tumor. Small benign suppressor Larger Malignant growth tumor gene DCC benign growth (polyp) (adenoma) (carcinoma)

Cancer therapy Cancer diagnosis includes a complete check of patient health, imagine diagnostics, blood and urine analysis, endoscopy. Surgery of a cancer cell mass is useful only for solid tumors. Chemotherapy is a cancer treatment that uses drugs to destroy cancer cells. Radiotherapy uses high energy rays to destroy cancer cells. 84 Sylvia S. Mader Concepts of Biology © Zanichelli editore, 2012

- Slides: 84