Cell Biology Protein Structure and Function Alberts Bruce

Cell Biology Protein Structure and Function Alberts, Bruce. Essential Cell Biology. 4 th ed. New York, NY: Garland Science Pub. , 2013. Print. Copyright © Garland Science 2013

Different types of proteins with distinct functions Structure Protein: Provides cell with shape and structure (actin) Enzymes: Catalyze covalent bond breakage or formation (pepsin) Transport Protein: Carries other molecules or ions (hemoglobin – oxygen) Motor Protein: Generates movement in cells and tissues (Myosin) Storage Protein: Stores small molecules or ions (ferritin - iron in liver) Signal Protein: Carries signals from cell to cell (insulin – glucose levels) Receptor Protein: Detects signals and transmits them to the cell’s response machinery (insulin receptor) Gene Regulatory Protein: Binds to DNA to switch genes on or off (transcriptional factors)

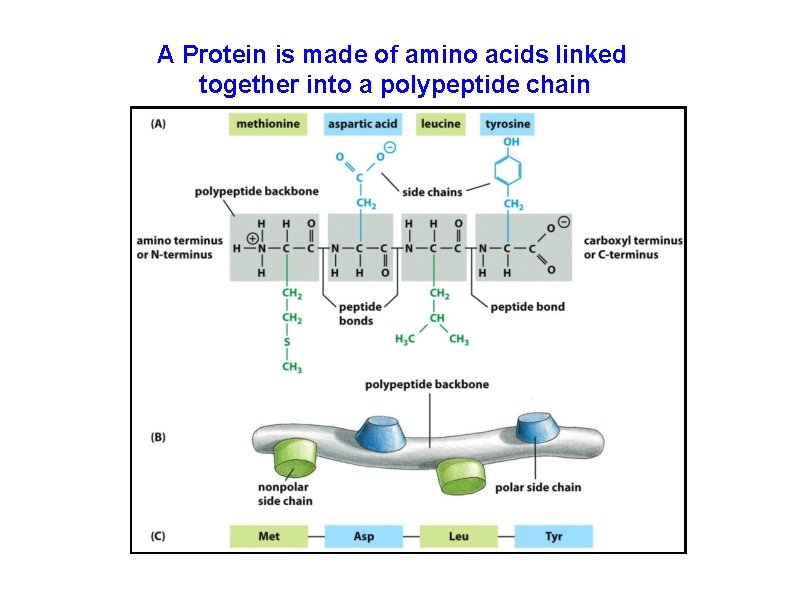

A Protein is made of amino acids linked together into a polypeptide chain

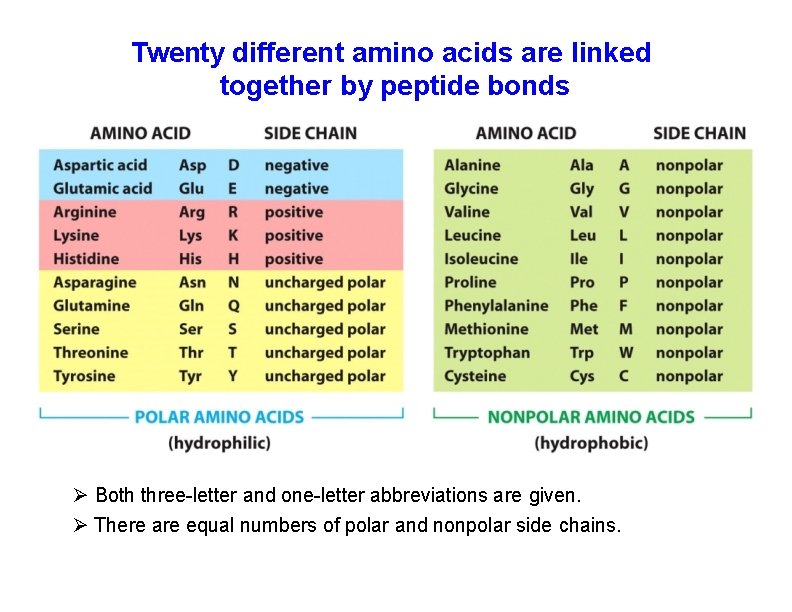

Twenty different amino acids are linked together by peptide bonds Both three-letter and one-letter abbreviations are given. There are equal numbers of polar and nonpolar side chains.

Types of noncovalent bonds or interactions help proteins fold Hydrogen bonds: When a hydrogen atom is “sandwiched” between electron-attracting atoms (oxygen or nitrogen). Electrostatic attractions: between charged groups. van der Waals attractions: attractions between two atoms at very short distances. Hydrophobic interaction

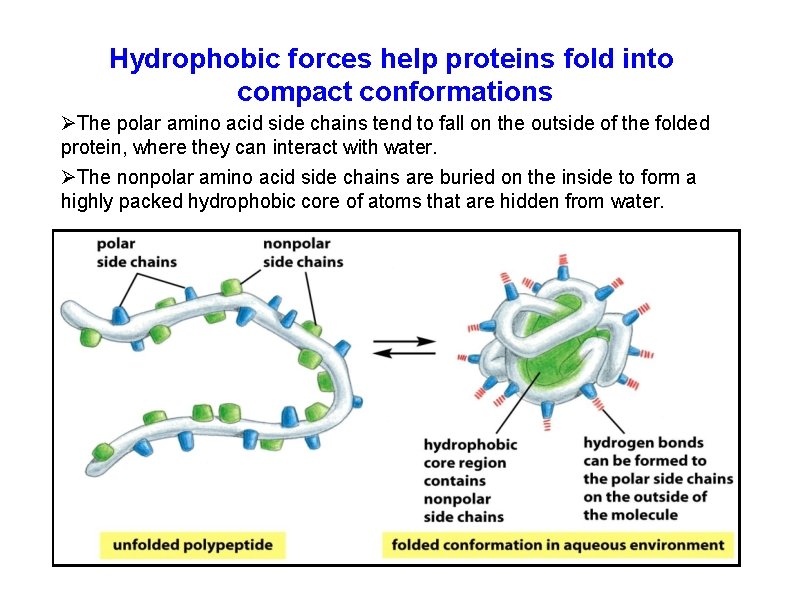

Hydrophobic forces help proteins fold into compact conformations The polar amino acid side chains tend to fall on the outside of the folded protein, where they can interact with water. The nonpolar amino acid side chains are buried on the inside to form a highly packed hydrophobic core of atoms that are hidden from water.

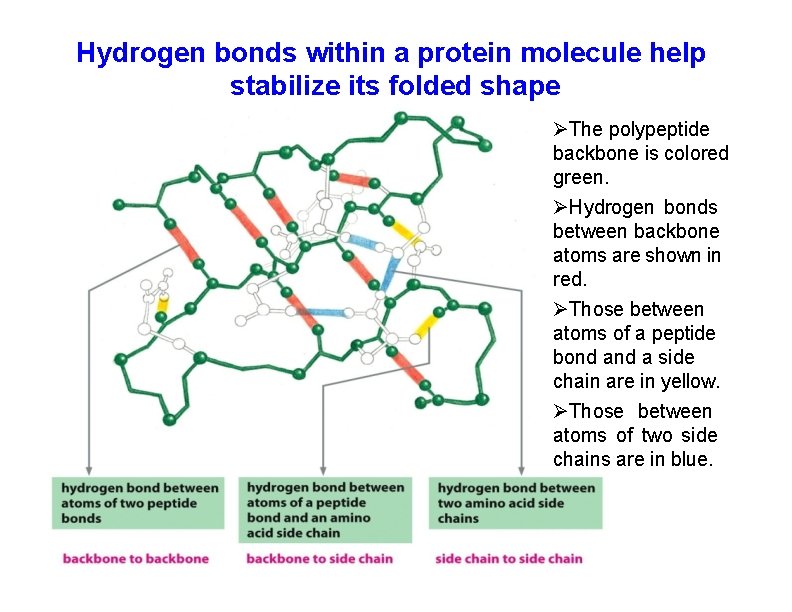

Hydrogen bonds within a protein molecule help stabilize its folded shape The polypeptide backbone is colored green. Hydrogen bonds between backbone atoms are shown in red. Those between atoms of a peptide bond a side chain are in yellow. Those between atoms of two side chains are in blue.

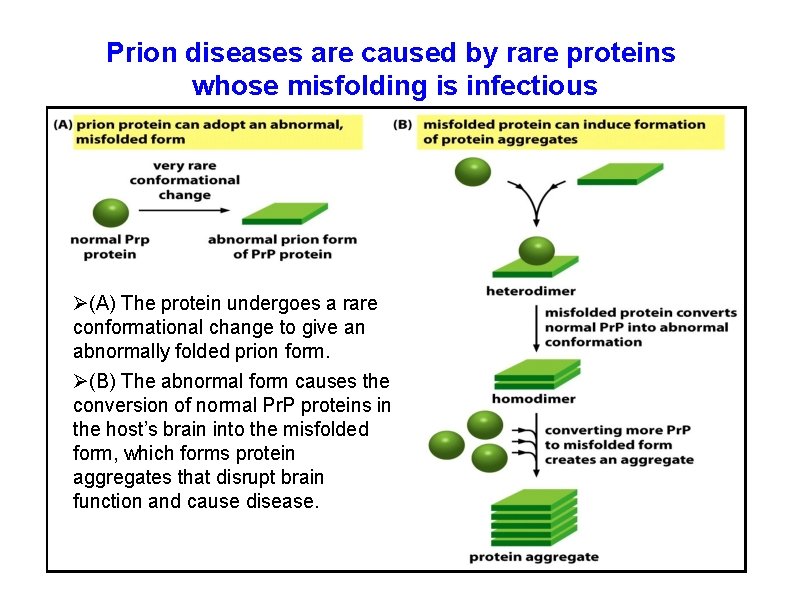

Prion diseases are caused by rare proteins whose misfolding is infectious (A) The protein undergoes a rare conformational change to give an abnormally folded prion form. (B) The abnormal form causes the conversion of normal Pr. P proteins in the host’s brain into the misfolded form, which forms protein aggregates that disrupt brain function and cause disease.

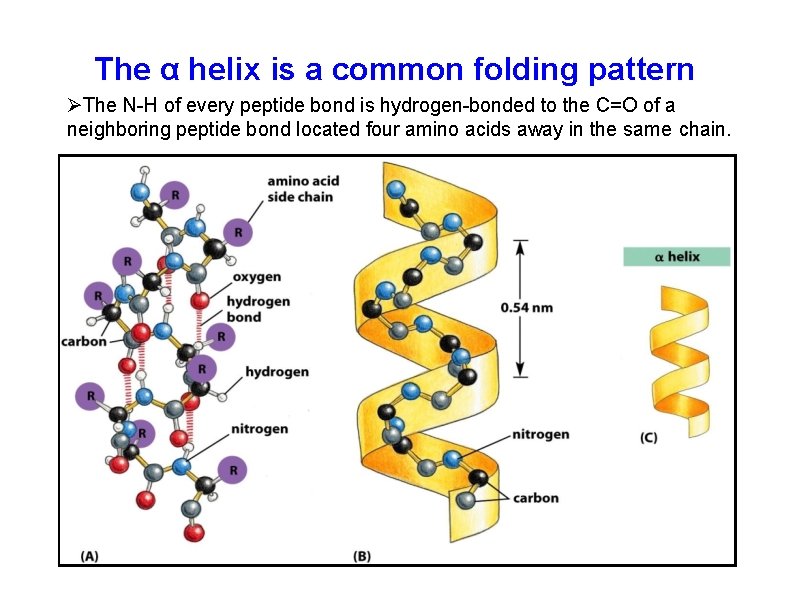

The. The α helix is a common folding pattern of proteins α helix is a common The N-H of every peptide bond is hydrogen-bonded to the C=O of a neighboring peptide bond located four amino acids away in the same chain.

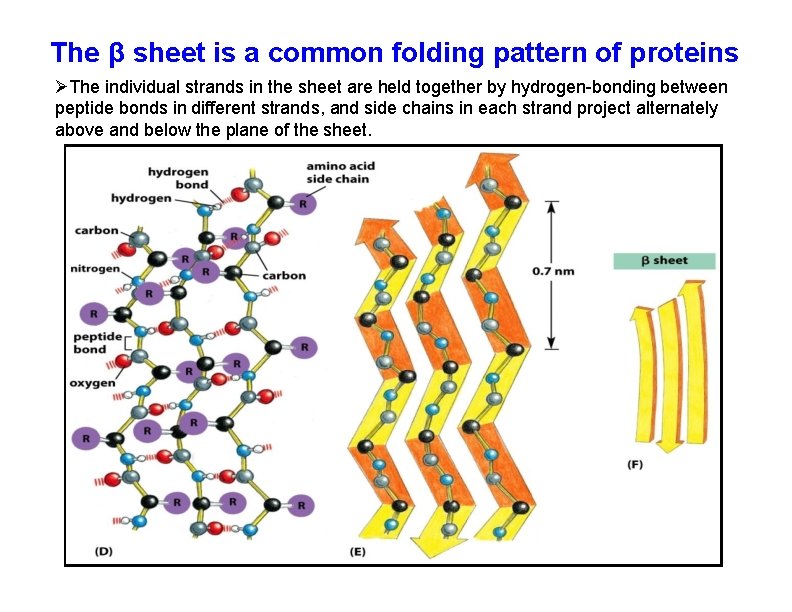

The β sheet is a common folding pattern of proteins The individual strands in the sheet are held together by hydrogen-bonding between peptide bonds in different strands, and side chains in each strand project alternately above and below the plane of the sheet.

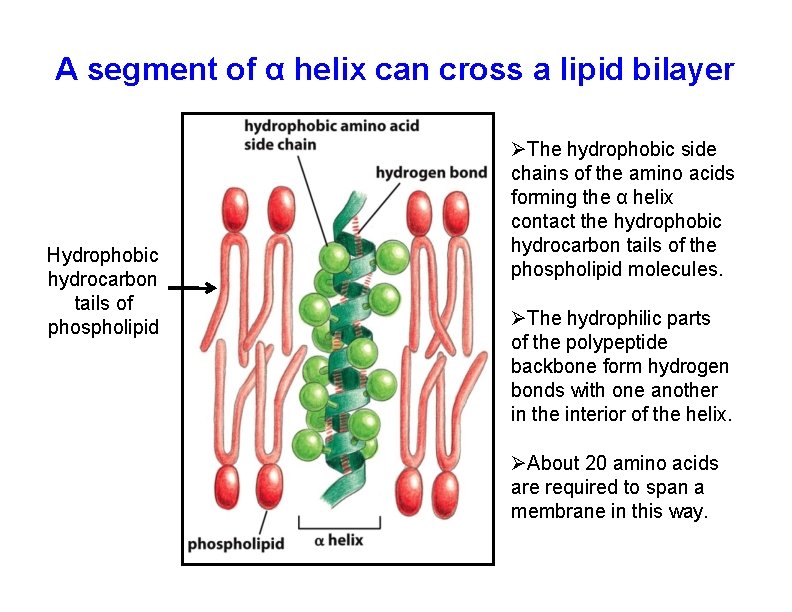

A segment of α helix can cross a lipid bilayer Hydrophobic hydrocarbon tails of phospholipid The hydrophobic side chains of the amino acids forming the α helix contact the hydrophobic hydrocarbon tails of the phospholipid molecules. The hydrophilic parts of the polypeptide backbone form hydrogen bonds with one another in the interior of the helix. About 20 amino acids are required to span a membrane in this way.

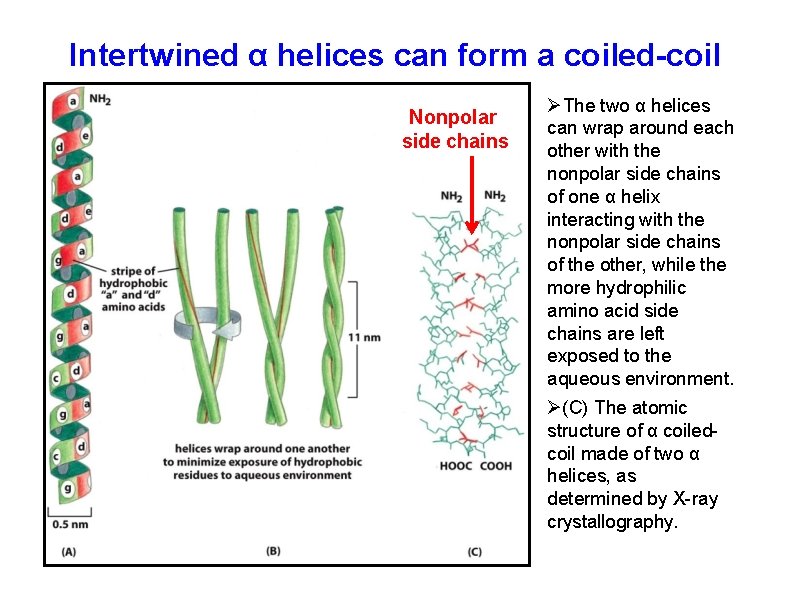

Intertwined α helices can form a coiled-coil Nonpolar side chains The two α helices can wrap around each other with the nonpolar side chains of one α helix interacting with the nonpolar side chains of the other, while the more hydrophilic amino acid side chains are left exposed to the aqueous environment. (C) The atomic structure of α coiledcoil made of two α helices, as determined by X-ray crystallography.

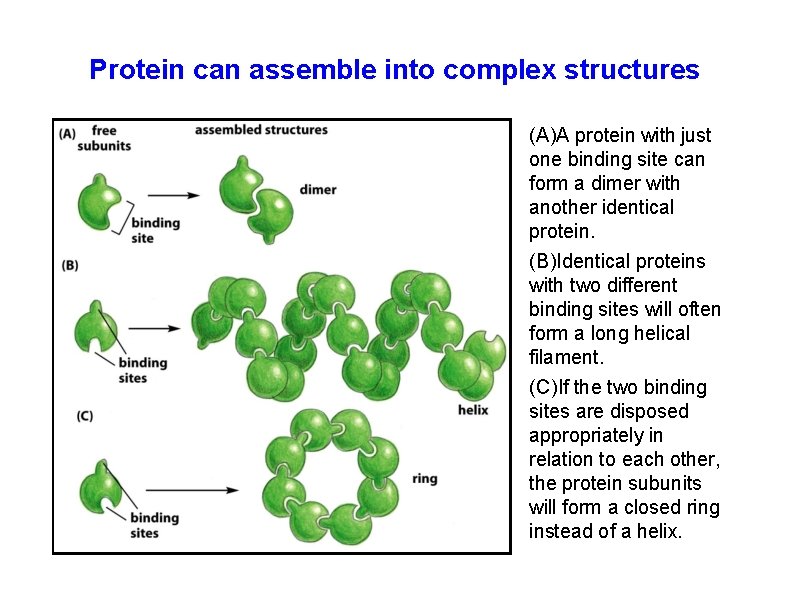

Protein can assemble into complex structures (A)A protein with just one binding site can form a dimer with another identical protein. (B)Identical proteins with two different binding sites will often form a long helical filament. (C)If the two binding sites are disposed appropriately in relation to each other, the protein subunits will form a closed ring instead of a helix.

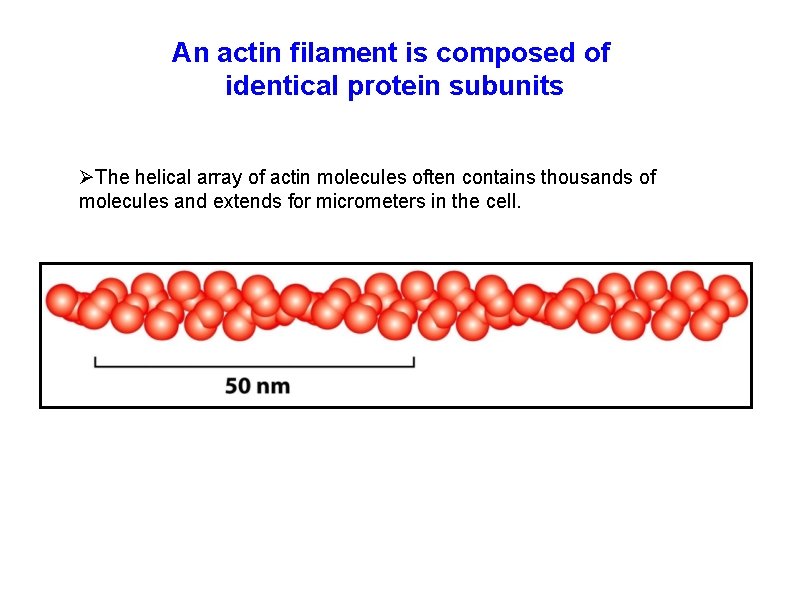

An actin filament is composed of identical protein subunits The helical array of actin molecules often contains thousands of molecules and extends for micrometers in the cell.

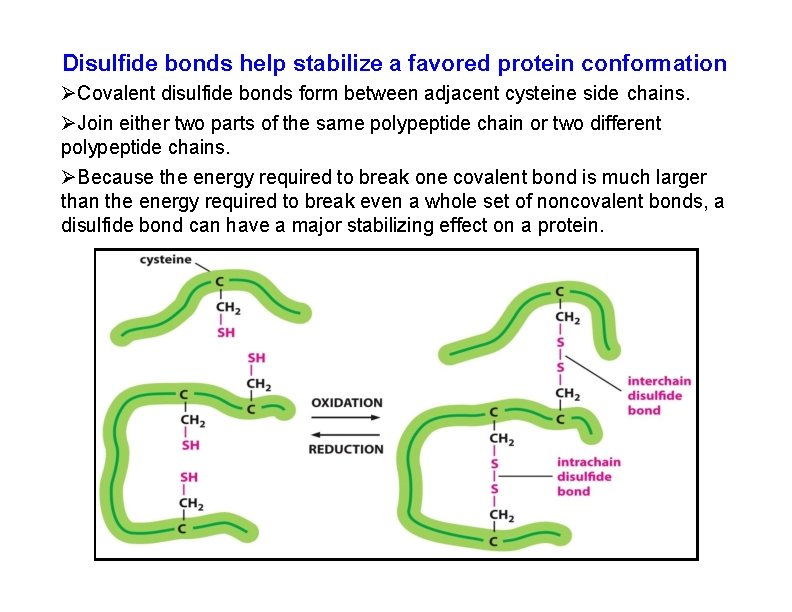

Disulfide bonds help stabilize a favored protein conformation Covalent disulfide bonds form between adjacent cysteine side chains. Join either two parts of the same polypeptide chain or two different polypeptide chains. Because the energy required to break one covalent bond is much larger than the energy required to break even a whole set of noncovalent bonds, a disulfide bond can have a major stabilizing effect on a protein.

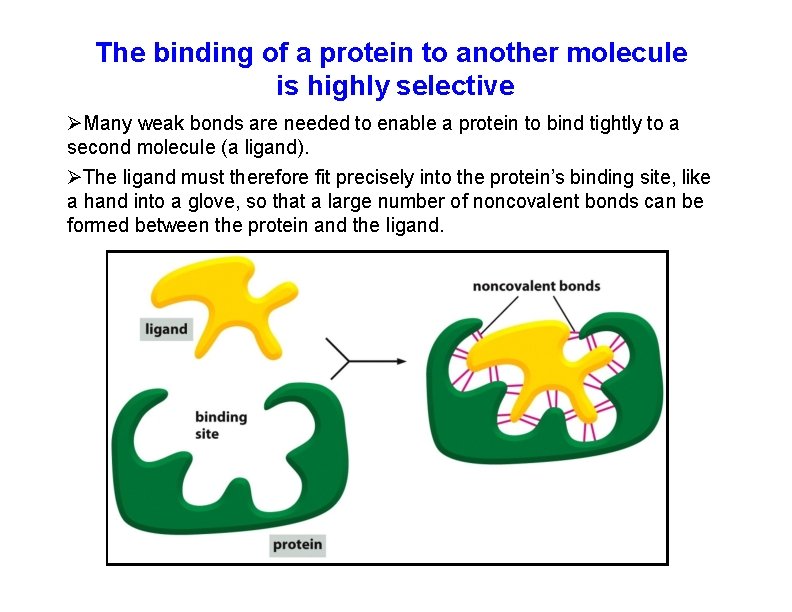

The binding of a protein to another molecule is highly selective Many weak bonds are needed to enable a protein to bind tightly to a second molecule (a ligand). The ligand must therefore fit precisely into the protein’s binding site, like a hand into a glove, so that a large number of noncovalent bonds can be formed between the protein and the ligand.

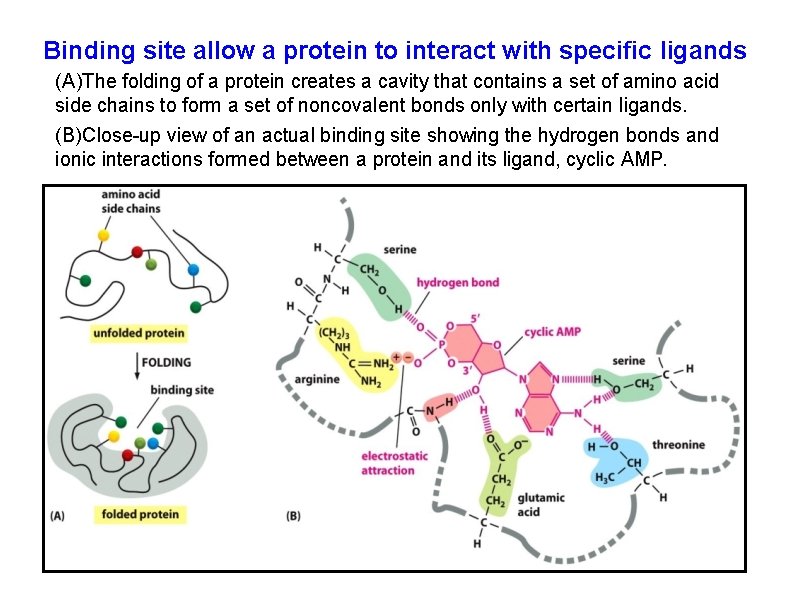

Binding site allow a protein to interact with specific ligands (A)The folding of a protein creates a cavity that contains a set of amino acid side chains to form a set of noncovalent bonds only with certain ligands. (B)Close-up view of an actual binding site showing the hydrogen bonds and ionic interactions formed between a protein and its ligand, cyclic AMP.

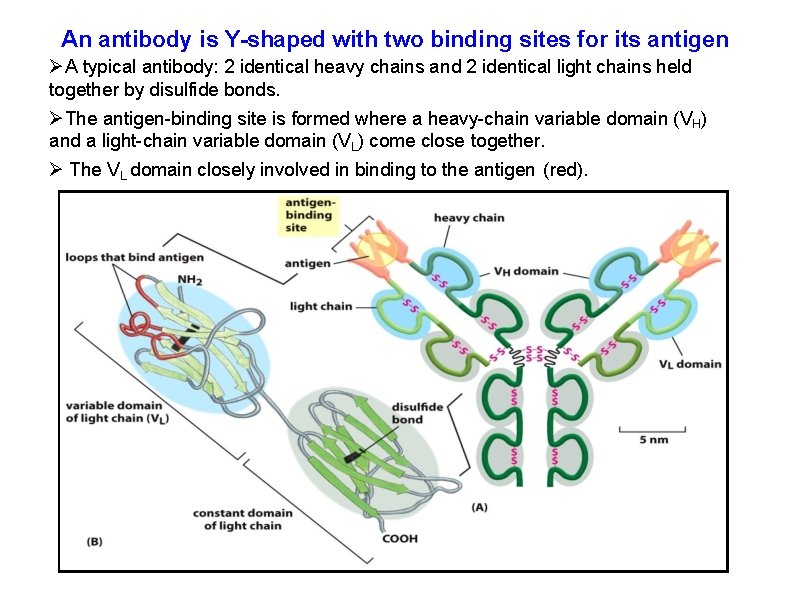

An antibody is Y-shaped with two binding sites for its antigen A typical antibody: 2 identical heavy chains and 2 identical light chains held together by disulfide bonds. The antigen-binding site is formed where a heavy-chain variable domain (VH) and a light-chain variable domain (VL) come close together. The VL domain closely involved in binding to the antigen (red).

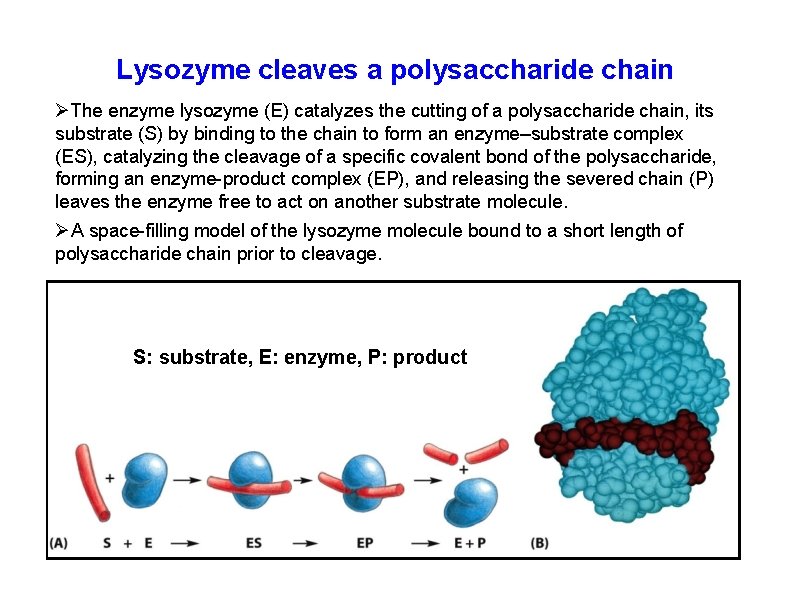

Lysozyme cleaves a polysaccharide chain The enzyme lysozyme (E) catalyzes the cutting of a polysaccharide chain, its substrate (S) by binding to the chain to form an enzyme–substrate complex (ES), catalyzing the cleavage of a specific covalent bond of the polysaccharide, forming an enzyme-product complex (EP), and releasing the severed chain (P) leaves the enzyme free to act on another substrate molecule. A space-filling model of the lysozyme molecule bound to a short length of polysaccharide chain prior to cleavage. S: substrate, E: enzyme, P: product

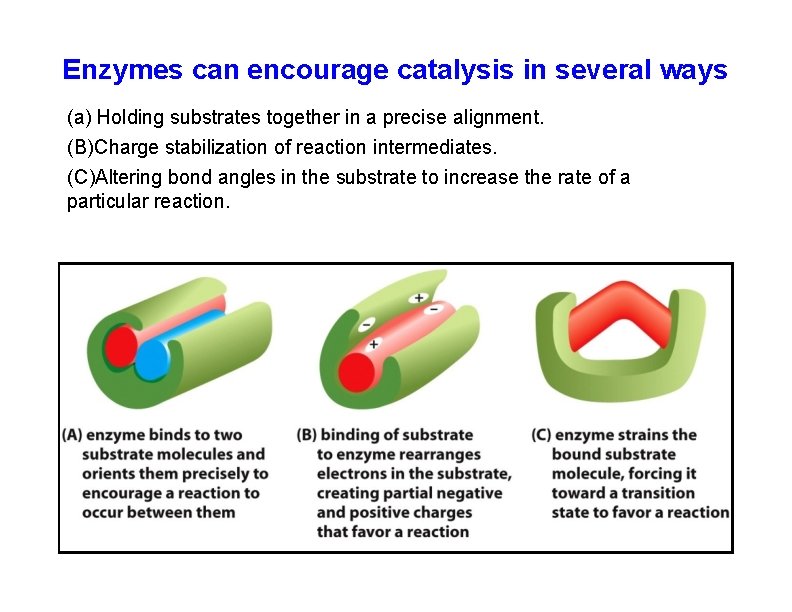

Enzymes can encourage catalysis in several ways (a) Holding substrates together in a precise alignment. (B)Charge stabilization of reaction intermediates. (C)Altering bond angles in the substrate to increase the rate of a particular reaction.

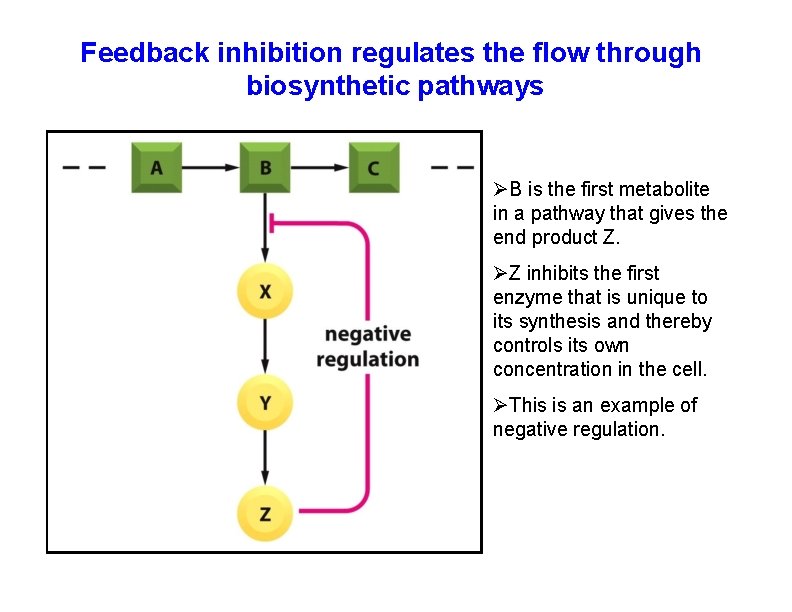

Feedback inhibition regulates the flow through biosynthetic pathways B is the first metabolite in a pathway that gives the end product Z. Z inhibits the first enzyme that is unique to its synthesis and thereby controls its own concentration in the cell. This is an example of negative regulation.

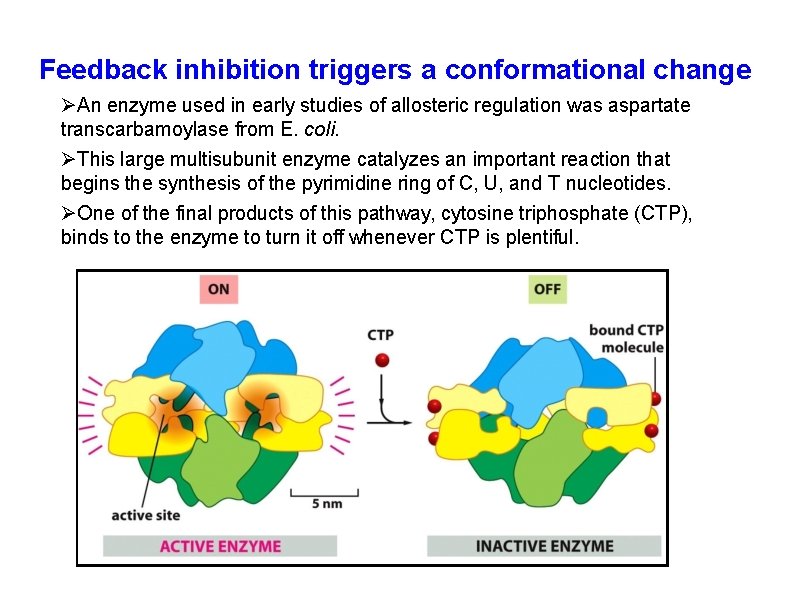

Feedback inhibition triggers a conformational change An enzyme used in early studies of allosteric regulation was aspartate transcarbamoylase from E. coli. This large multisubunit enzyme catalyzes an important reaction that begins the synthesis of the pyrimidine ring of C, U, and T nucleotides. One of the final products of this pathway, cytosine triphosphate (CTP), binds to the enzyme to turn it off whenever CTP is plentiful.

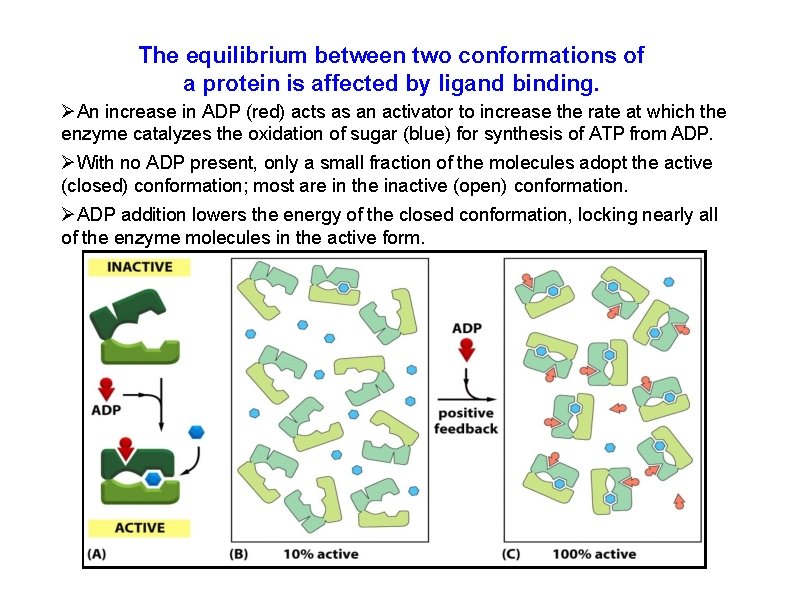

The equilibrium between two conformations of a protein is affected by ligand binding. An increase in ADP (red) acts as an activator to increase the rate at which the enzyme catalyzes the oxidation of sugar (blue) for synthesis of ATP from ADP. With no ADP present, only a small fraction of the molecules adopt the active (closed) conformation; most are in the inactive (open) conformation. ADP addition lowers the energy of the closed conformation, locking nearly all of the enzyme molecules in the active form.

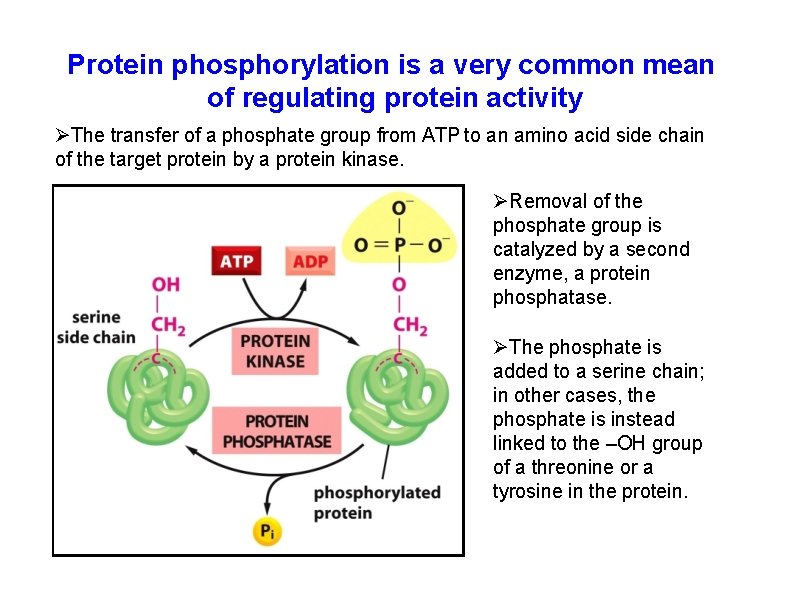

Protein phosphorylation is a very common mean of regulating protein activity The transfer of a phosphate group from ATP to an amino acid side chain of the target protein by a protein kinase. Removal of the phosphate group is catalyzed by a second enzyme, a protein phosphatase. The phosphate is added to a serine chain; in other cases, the phosphate is instead linked to the –OH group of a threonine or a tyrosine in the protein.

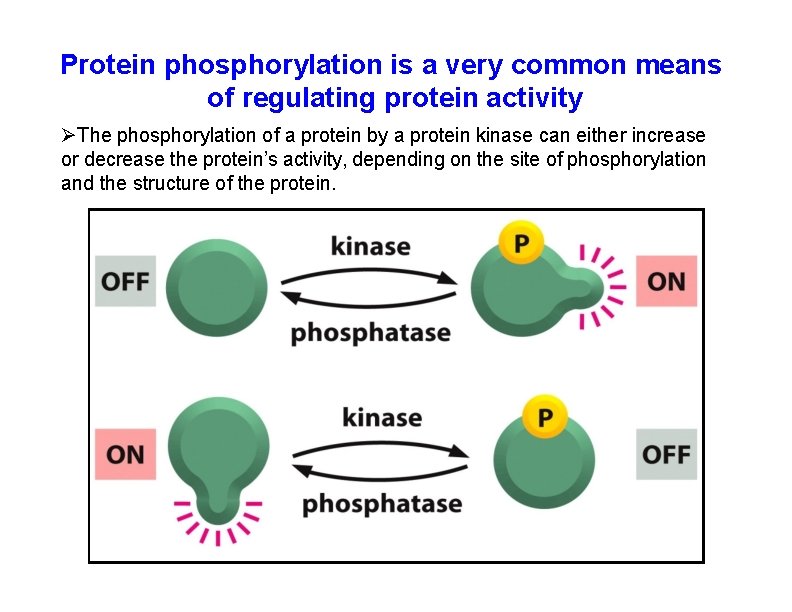

Protein phosphorylation is a very common means of regulating protein activity The phosphorylation of a protein by a protein kinase can either increase or decrease the protein’s activity, depending on the site of phosphorylation and the structure of the protein.

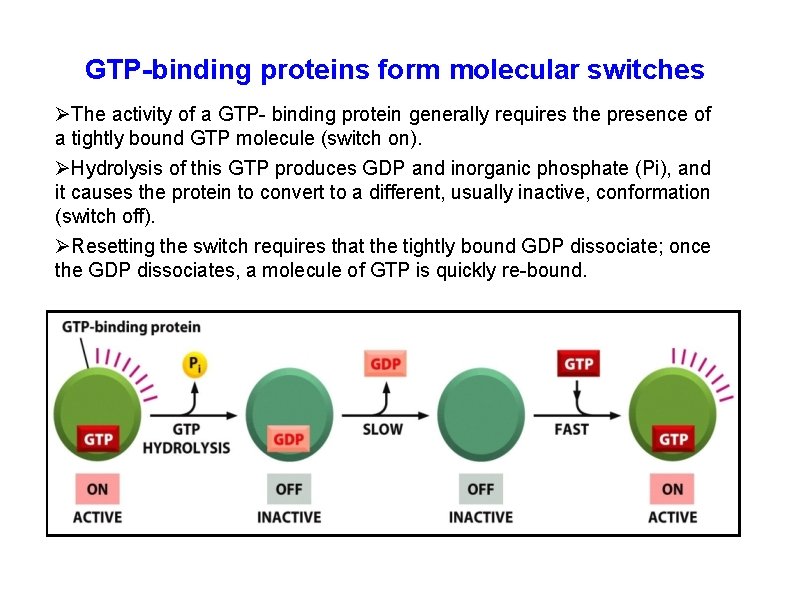

GTP-binding proteins form molecular switches The activity of a GTP- binding protein generally requires the presence of a tightly bound GTP molecule (switch on). Hydrolysis of this GTP produces GDP and inorganic phosphate (Pi), and it causes the protein to convert to a different, usually inactive, conformation (switch off). Resetting the switch requires that the tightly bound GDP dissociate; once the GDP dissociates, a molecule of GTP is quickly re-bound.

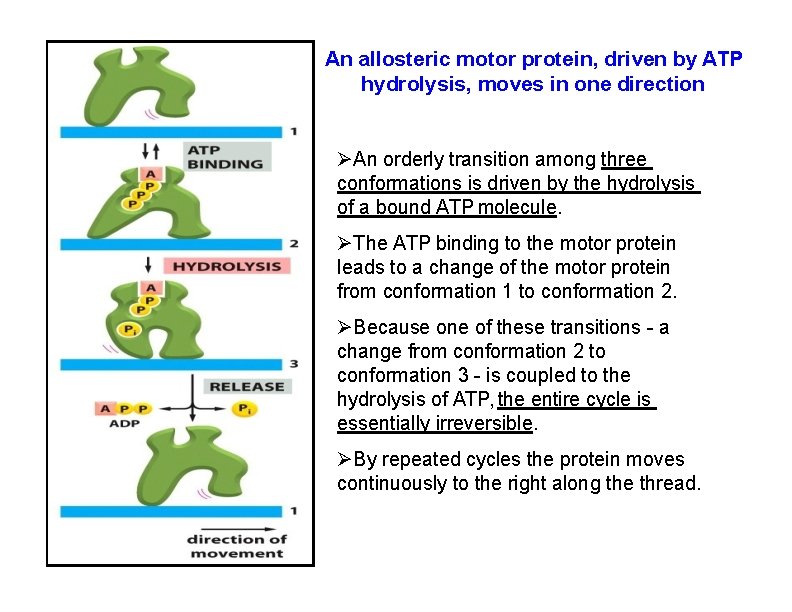

An allosteric motor protein, driven by ATP hydrolysis, moves in one direction An orderly transition among three conformations is driven by the hydrolysis of a bound ATP molecule. The ATP binding to the motor protein leads to a change of the motor protein from conformation 1 to conformation 2. Because one of these transitions - a change from conformation 2 to conformation 3 - is coupled to the hydrolysis of ATP, the entire cycle is essentially irreversible. By repeated cycles the protein moves continuously to the right along the thread.

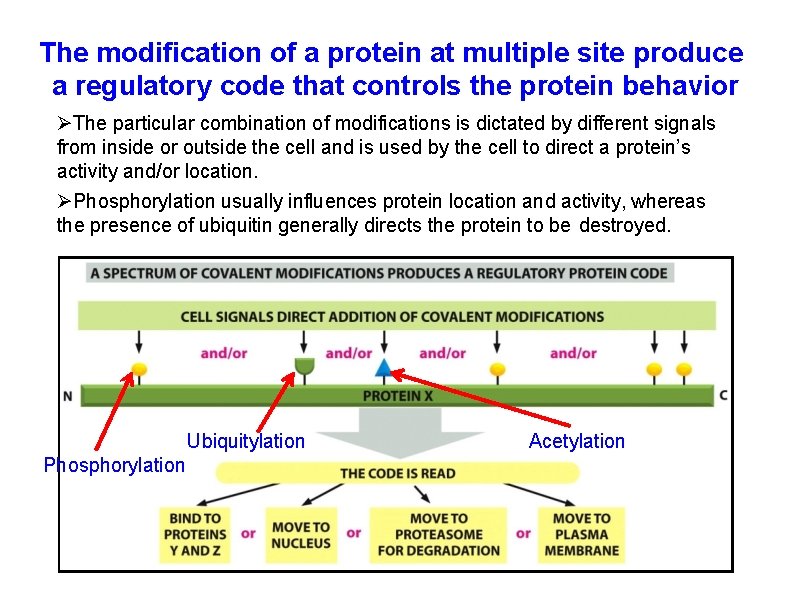

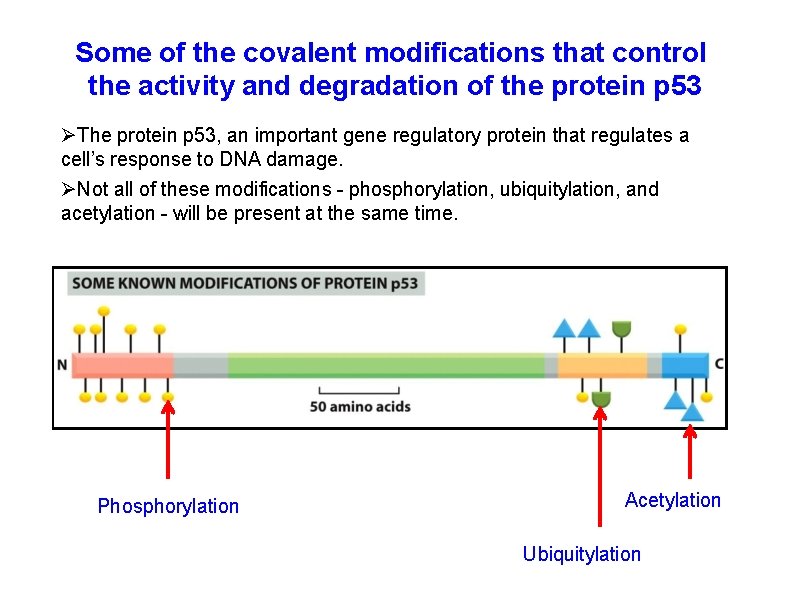

The modification of a protein at multiple site produce a regulatory code that controls the protein behavior The particular combination of modifications is dictated by different signals from inside or outside the cell and is used by the cell to direct a protein’s activity and/or location. Phosphorylation usually influences protein location and activity, whereas the presence of ubiquitin generally directs the protein to be destroyed. Ubiquitylation Phosphorylation Acetylation

Some of the covalent modifications that control the activity and degradation of the protein p 53 The protein p 53, an important gene regulatory protein that regulates a cell’s response to DNA damage. Not all of these modifications - phosphorylation, ubiquitylation, and acetylation - will be present at the same time. Phosphorylation Acetylation Ubiquitylation

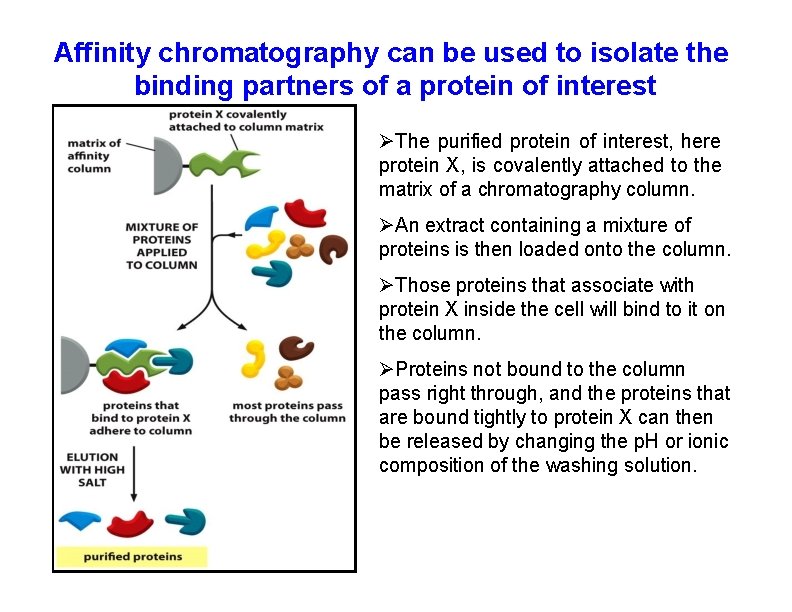

Affinity chromatography can be used to isolate the binding partners of a protein of interest The purified protein of interest, here protein X, is covalently attached to the matrix of a chromatography column. An extract containing a mixture of proteins is then loaded onto the column. Those proteins that associate with protein X inside the cell will bind to it on the column. Proteins not bound to the column pass right through, and the proteins that are bound tightly to protein X can then be released by changing the p. H or ionic composition of the washing solution.

- Slides: 30