Cell Biology DNA to Protein Alberts Bruce Essential

Cell Biology DNA to Protein Alberts, Bruce. Essential Cell Biology. 4 th ed. New York, NY: Garland Science Pub. , 2013. Print. Copyright © Garland Science 2013

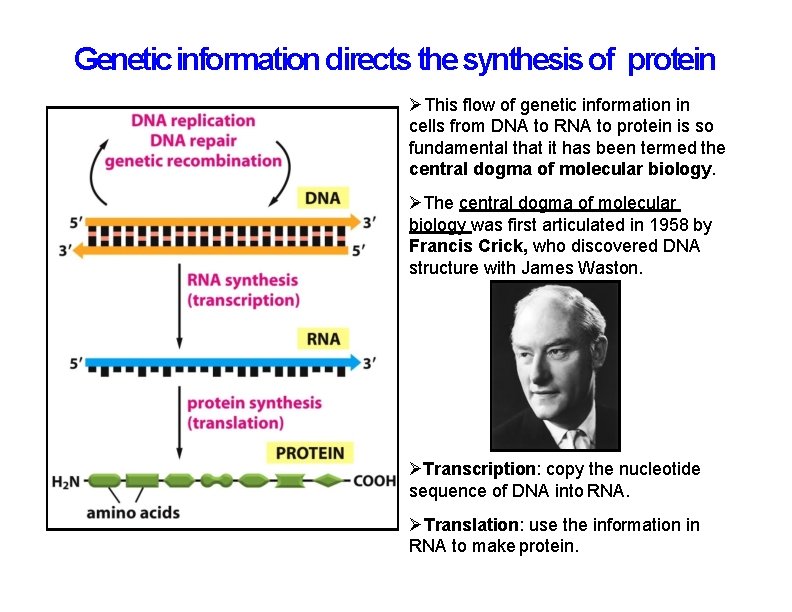

Genetic information directs the synthesis of protein This flow of genetic information in cells from DNA to RNA to protein is so fundamental that it has been termed the central dogma of molecular biology. The central dogma of molecular biology was first articulated in 1958 by Francis Crick, who discovered DNA structure with James Waston. Transcription: copy the nucleotide sequence of DNA into RNA. Translation: use the information in RNA to make protein.

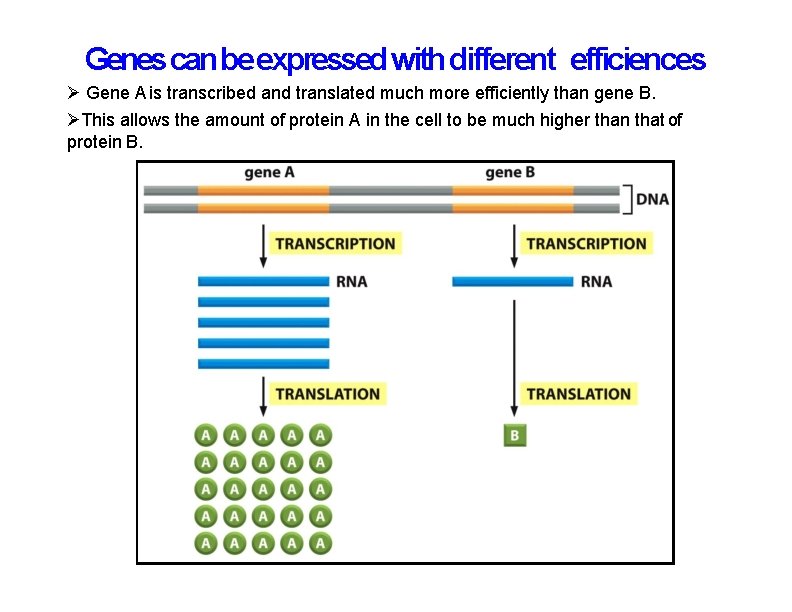

Genes can be expressed with different efficiences Gene A is transcribed and translated much more efficiently than gene B. This allows the amount of protein A in the cell to be much higher than that of protein B.

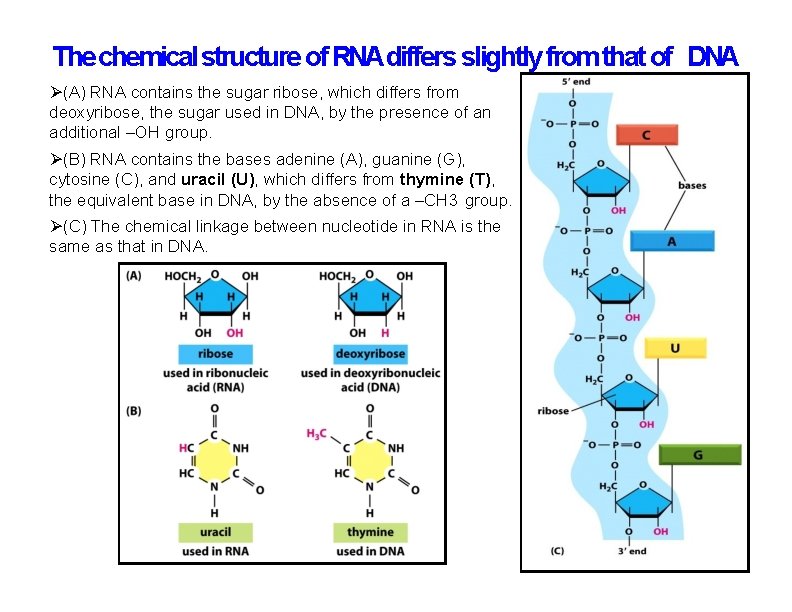

The chemical structure of RNAdiffers slightly from that of DNA (A) RNA contains the sugar ribose, which differs from deoxyribose, the sugar used in DNA, by the presence of an additional –OH group. (B) RNA contains the bases adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C), and uracil (U), which differs from thymine (T), the equivalent base in DNA, by the absence of a –CH 3 group. (C) The chemical linkage between nucleotide in RNA is the same as that in DNA.

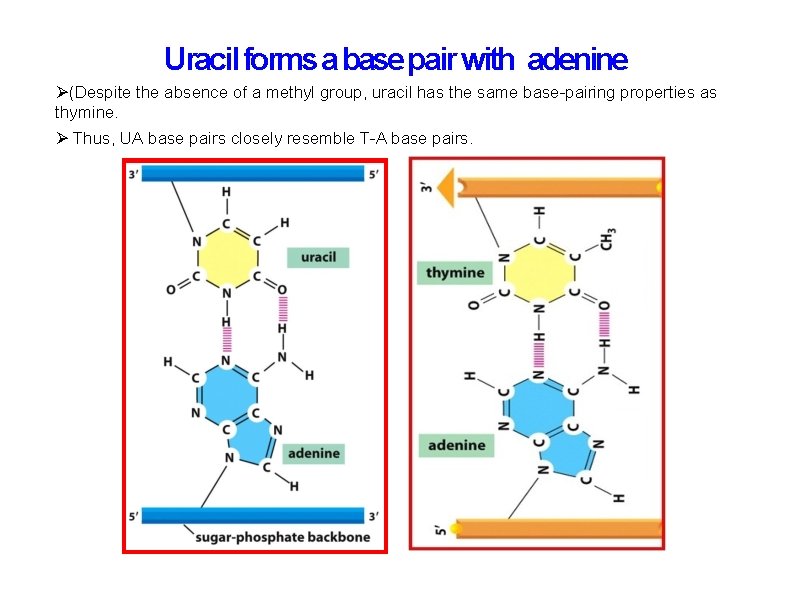

Uracil forms a base pair with adenine (Despite the absence of a methyl group, uracil has the same base-pairing properties as thymine. Thus, UA base pairs closely resemble T-A base pairs.

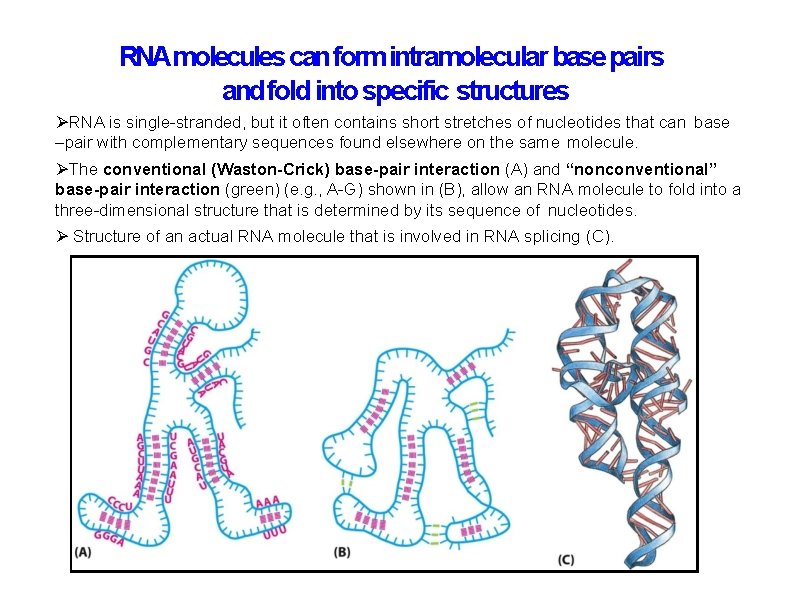

RNAmolecules can form intramolecular base pairs and fold into specific structures RNA is single-stranded, but it often contains short stretches of nucleotides that can base –pair with complementary sequences found elsewhere on the same molecule. The conventional (Waston-Crick) base-pair interaction (A) and “nonconventional” base-pair interaction (green) (e. g. , A-G) shown in (B), allow an RNA molecule to fold into a three-dimensional structure that is determined by its sequence of nucleotides. Structure of an actual RNA molecule that is involved in RNA splicing (C).

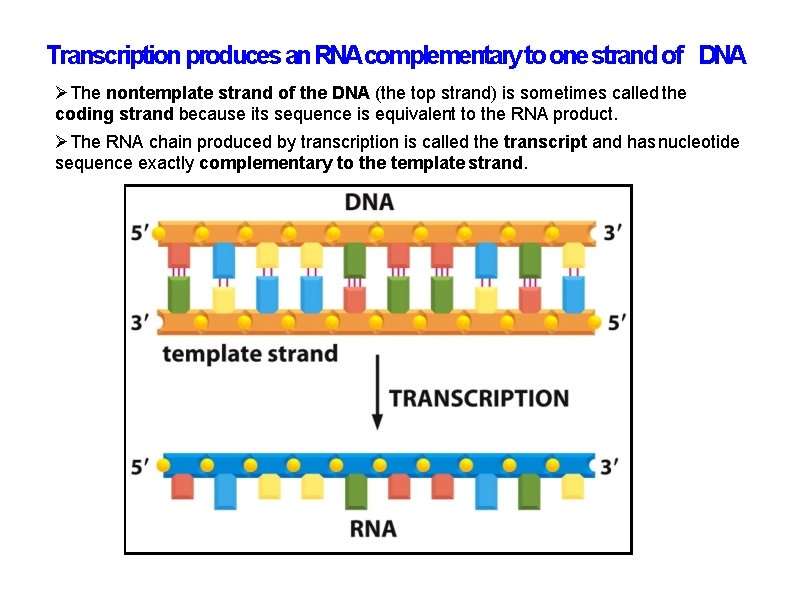

Transcription produces an RNAcomplementary to one strand of DNA The nontemplate strand of the DNA (the top strand) is sometimes called the coding strand because its sequence is equivalent to the RNA product. The RNA chain produced by transcription is called the transcript and has nucleotide sequence exactly complementary to the template strand.

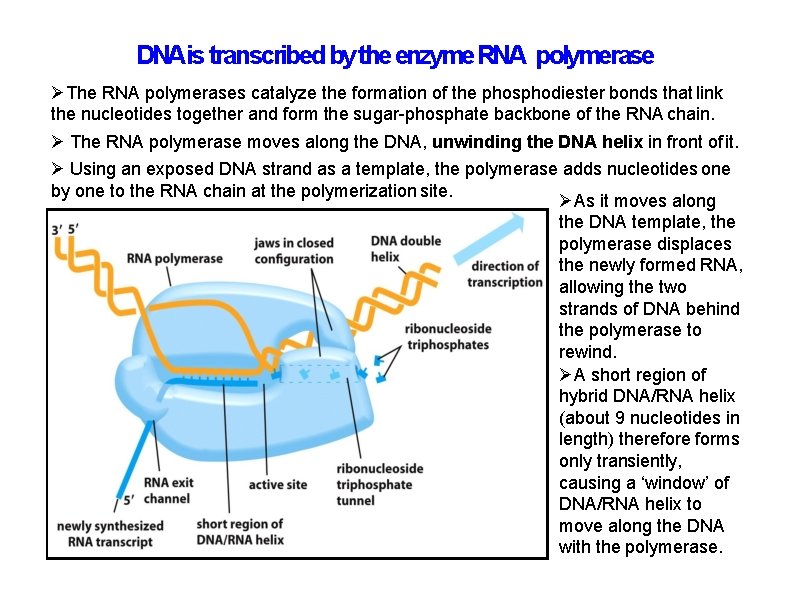

DNAis transcribed by the enzyme RNA polymerase The RNA polymerases catalyze the formation of the phosphodiester bonds that link the nucleotides together and form the sugar-phosphate backbone of the RNA chain. The RNA polymerase moves along the DNA, unwinding the DNA helix in front of it. Using an exposed DNA strand as a template, the polymerase adds nucleotides one by one to the RNA chain at the polymerization site. As it moves along the DNA template, the polymerase displaces the newly formed RNA, allowing the two strands of DNA behind the polymerase to rewind. A short region of hybrid DNA/RNA helix (about 9 nucleotides in length) therefore forms only transiently, causing a ‘window’ of DNA/RNA helix to move along the DNA with the polymerase.

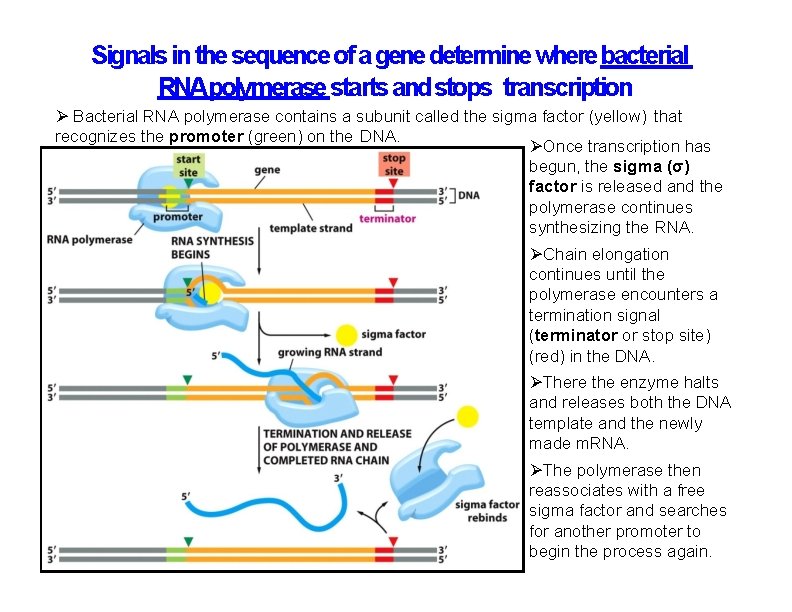

Signals in the sequence of a gene determine where bacterial RNApolymerase starts and stops transcription Bacterial RNA polymerase contains a subunit called the sigma factor (yellow) that recognizes the promoter (green) on the DNA. Once transcription has begun, the sigma (σ) factor is released and the polymerase continues synthesizing the RNA. Chain elongation continues until the polymerase encounters a termination signal (terminator or stop site) (red) in the DNA. There the enzyme halts and releases both the DNA template and the newly made m. RNA. The polymerase then reassociates with a free sigma factor and searches for another promoter to begin the process again.

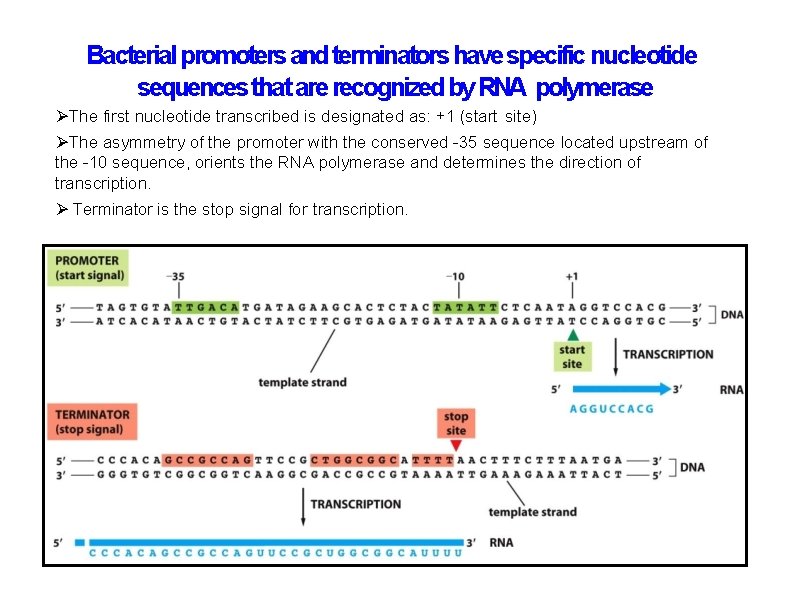

Bacterial promoters and terminators have specific nucleotide sequences that are recognized by RNA polymerase The first nucleotide transcribed is designated as: +1 (start site) The asymmetry of the promoter with the conserved -35 sequence located upstream of the -10 sequence, orients the RNA polymerase and determines the direction of transcription. Terminator is the stop signal for transcription.

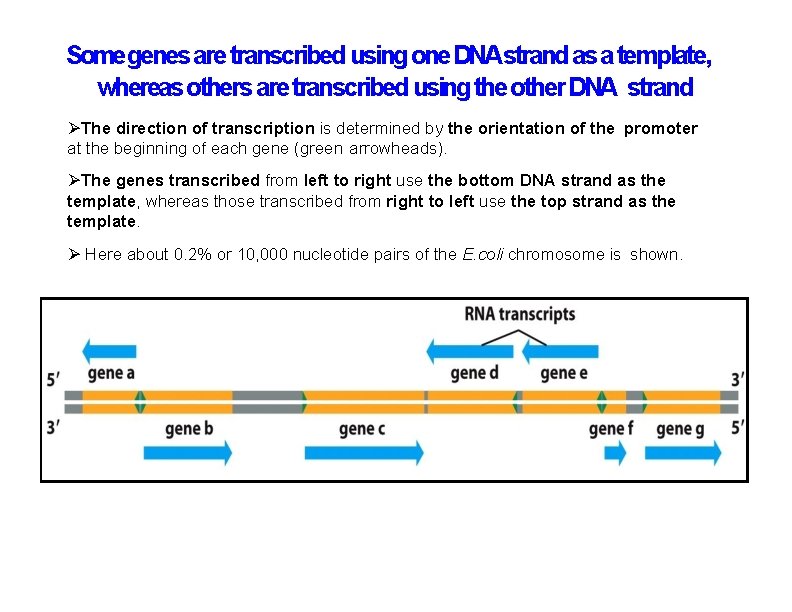

Somegenes are transcribed using one DNAstrand as a template, whereas others are transcribed using the other DNA strand The direction of transcription is determined by the orientation of the promoter at the beginning of each gene (green arrowheads). The genes transcribed from left to right use the bottom DNA strand as the template, whereas those transcribed from right to left use the top strand as the template. Here about 0. 2% or 10, 000 nucleotide pairs of the E. coli chromosome is shown.

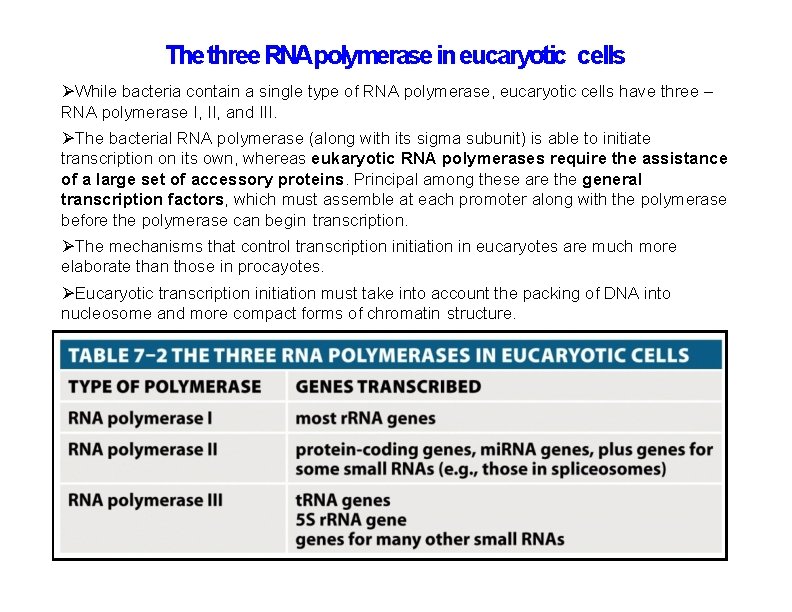

The three RNApolymerase in eucaryotic cells While bacteria contain a single type of RNA polymerase, eucaryotic cells have three – RNA polymerase I, II, and III. The bacterial RNA polymerase (along with its sigma subunit) is able to initiate transcription on its own, whereas eukaryotic RNA polymerases require the assistance of a large set of accessory proteins. Principal among these are the general transcription factors, which must assemble at each promoter along with the polymerase before the polymerase can begin transcription. The mechanisms that control transcription initiation in eucaryotes are much more elaborate than those in procayotes. Eucaryotic transcription initiation must take into account the packing of DNA into nucleosome and more compact forms of chromatin structure.

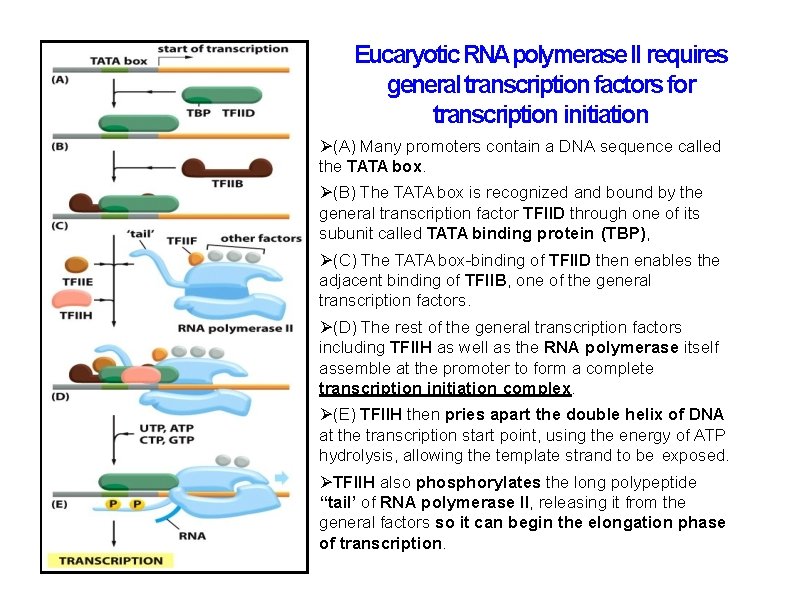

Eucaryotic RNApolymerase II requires general transcription factors for transcription initiation (A) Many promoters contain a DNA sequence called the TATA box. (B) The TATA box is recognized and bound by the general transcription factor TFIID through one of its subunit called TATA binding protein (TBP), (C) The TATA box-binding of TFIID then enables the adjacent binding of TFIIB, one of the general transcription factors. (D) The rest of the general transcription factors including TFIIH as well as the RNA polymerase itself assemble at the promoter to form a complete transcription initiation complex. (E) TFIIH then pries apart the double helix of DNA at the transcription start point, using the energy of ATP hydrolysis, allowing the template strand to be exposed. TFIIH also phosphorylates the long polypeptide “tail’ of RNA polymerase II, releasing it from the general factors so it can begin the elongation phase of transcription.

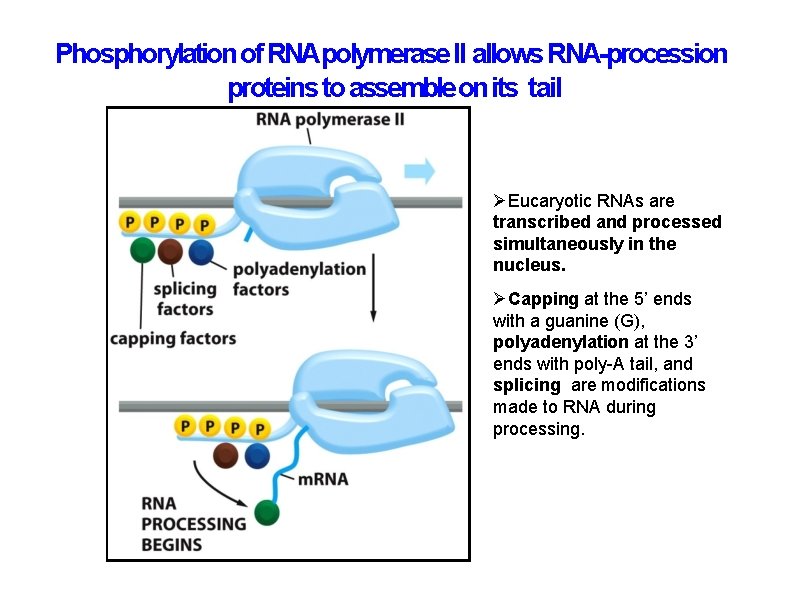

Phosphorylation of RNApolymerase II allows RNA-procession proteins to assemble on its tail Eucaryotic RNAs are transcribed and processed simultaneously in the nucleus. Capping at the 5’ ends with a guanine (G), polyadenylation at the 3’ ends with poly-A tail, and splicing are modifications made to RNA during processing.

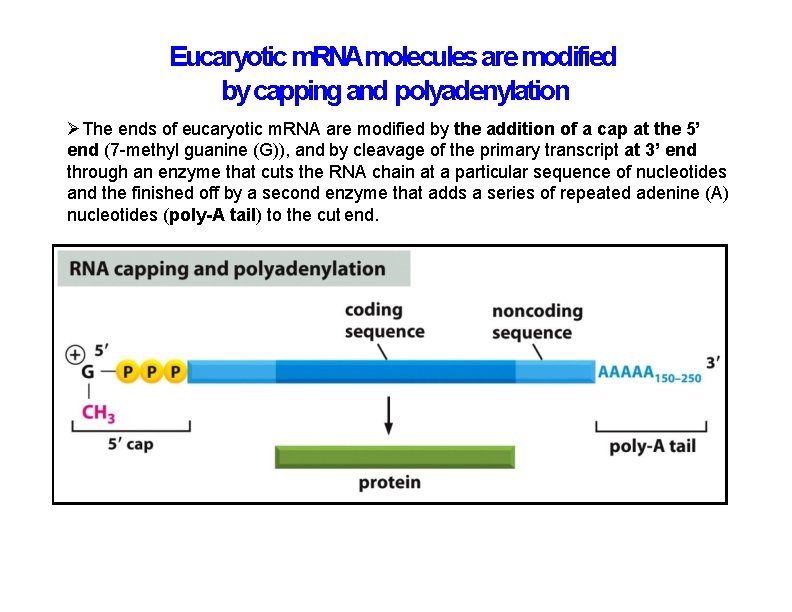

Eucaryotic m. RNAmolecules are modified by capping and polyadenylation The ends of eucaryotic m. RNA are modified by the addition of a cap at the 5’ end (7 -methyl guanine (G)), and by cleavage of the primary transcript at 3’ end through an enzyme that cuts the RNA chain at a particular sequence of nucleotides and the finished off by a second enzyme that adds a series of repeated adenine (A) nucleotides (poly-A tail) to the cut end.

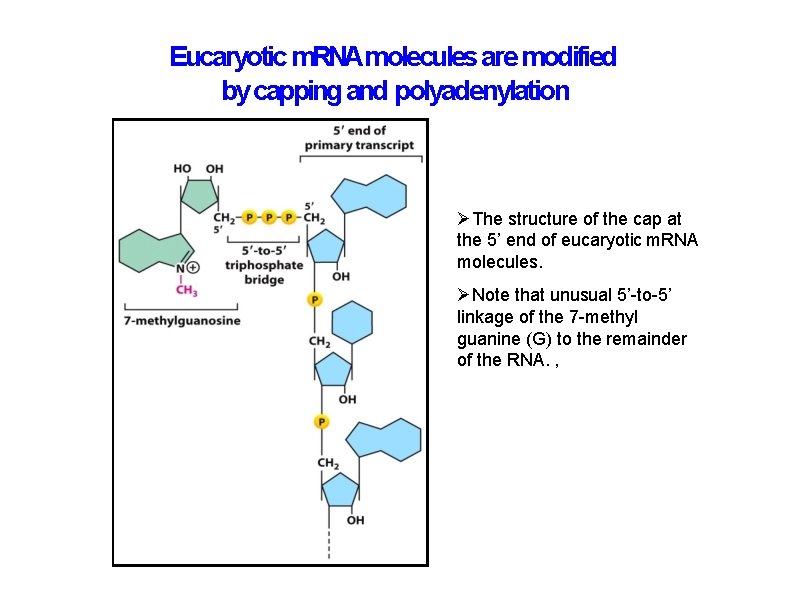

Eucaryotic m. RNAmolecules are modified by capping and polyadenylation The structure of the cap at the 5’ end of eucaryotic m. RNA molecules. Note that unusual 5’-to-5’ linkage of the 7 -methyl guanine (G) to the remainder of the RNA. ,

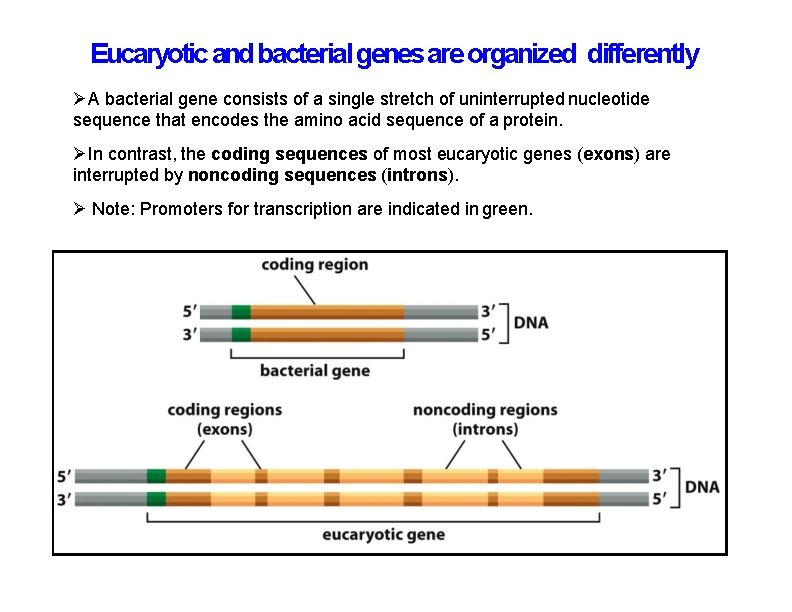

Eucaryotic and bacterial genes are organized differently A bacterial gene consists of a single stretch of uninterrupted nucleotide sequence that encodes the amino acid sequence of a protein. In contrast, the coding sequences of most eucaryotic genes (exons) are interrupted by noncoding sequences (introns). Note: Promoters for transcription are indicated in green.

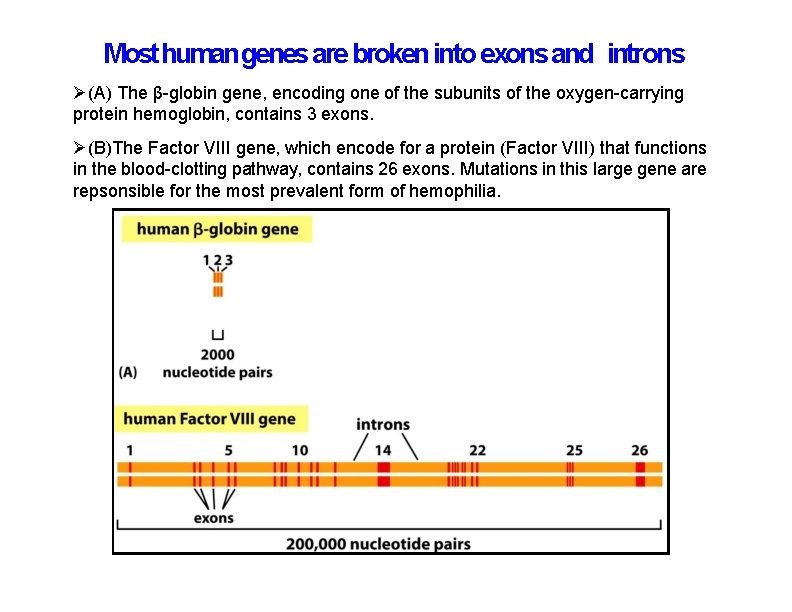

Most human genes are broken into exons and introns (A) The β-globin gene, encoding one of the subunits of the oxygen-carrying protein hemoglobin, contains 3 exons. (B)The Factor VIII gene, which encode for a protein (Factor VIII) that functions in the blood-clotting pathway, contains 26 exons. Mutations in this large gene are repsonsible for the most prevalent form of hemophilia.

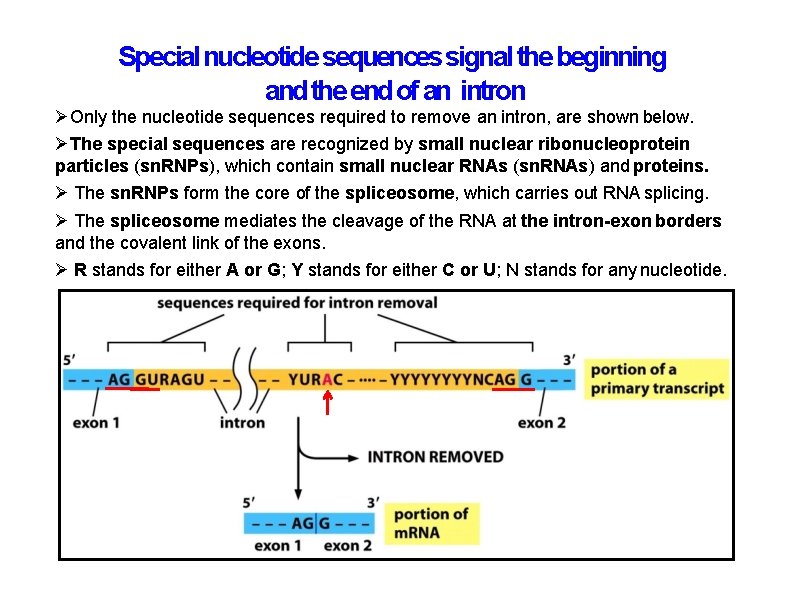

Special nucleotide sequences signal the beginning and the end of an intron Only the nucleotide sequences required to remove an intron, are shown below. The special sequences are recognized by small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles (sn. RNPs), which contain small nuclear RNAs (sn. RNAs) and proteins. The sn. RNPs form the core of the spliceosome, which carries out RNA splicing. The spliceosome mediates the cleavage of the RNA at the intron-exon borders and the covalent link of the exons. R stands for either A or G; Y stands for either C or U; N stands for any nucleotide.

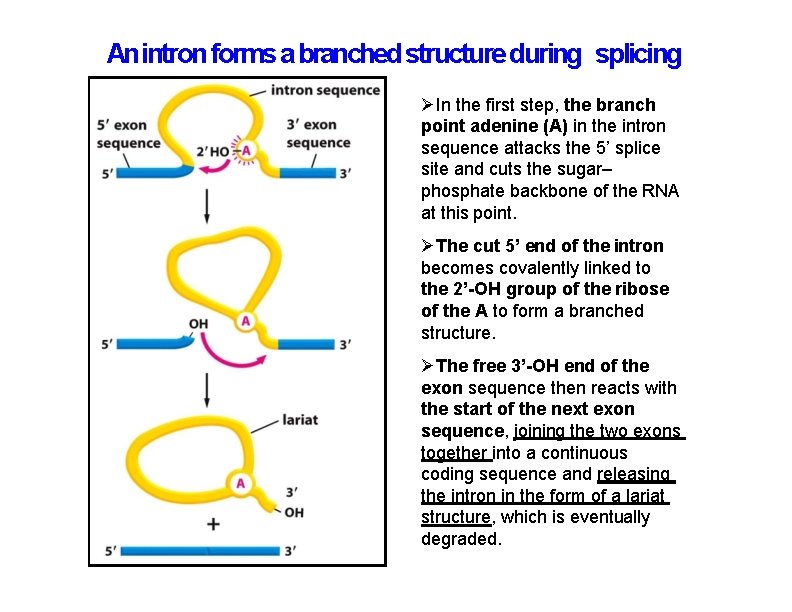

An intron forms a branched structure during splicing In the first step, the branch point adenine (A) in the intron sequence attacks the 5’ splice site and cuts the sugar– phosphate backbone of the RNA at this point. The cut 5’ end of the intron becomes covalently linked to the 2’-OH group of the ribose of the A to form a branched structure. The free 3’-OH end of the exon sequence then reacts with the start of the next exon sequence, joining the two exons together into a continuous coding sequence and releasing the intron in the form of a lariat structure, which is eventually degraded.

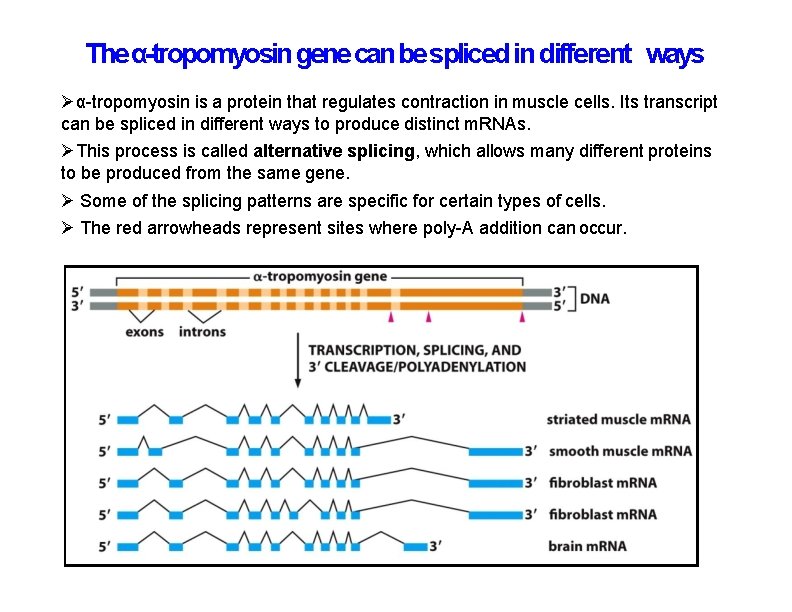

The α-tropomyosin gene can be spliced in different ways α-tropomyosin is a protein that regulates contraction in muscle cells. Its transcript can be spliced in different ways to produce distinct m. RNAs. This process is called alternative splicing, which allows many different proteins to be produced from the same gene. Some of the splicing patterns are specific for certain types of cells. The red arrowheads represent sites where poly-A addition can occur.

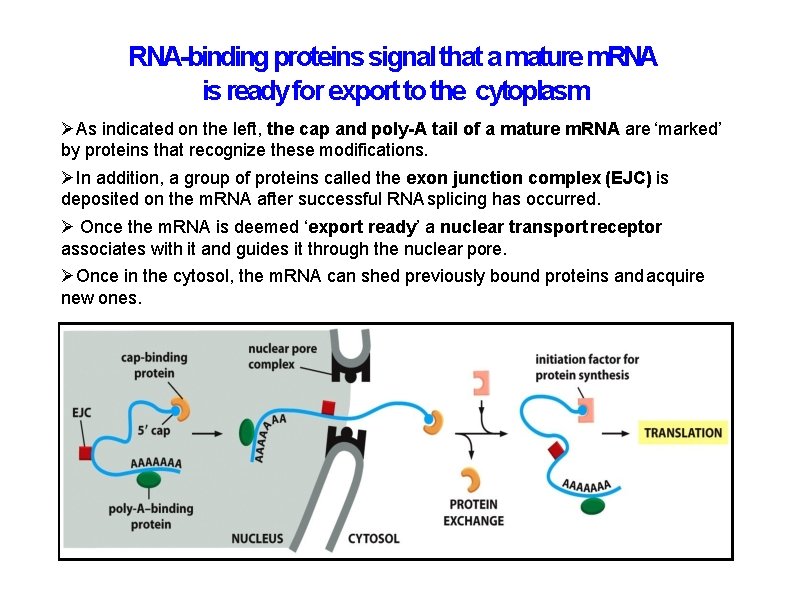

RNA-binding proteins signal that a mature m. RNA is ready for export to the cytoplasm As indicated on the left, the cap and poly-A tail of a mature m. RNA are ‘marked’ by proteins that recognize these modifications. In addition, a group of proteins called the exon junction complex (EJC) is deposited on the m. RNA after successful RNA splicing has occurred. Once the m. RNA is deemed ‘export ready’ a nuclear transport receptor associates with it and guides it through the nuclear pore. Once in the cytosol, the m. RNA can shed previously bound proteins and acquire new ones.

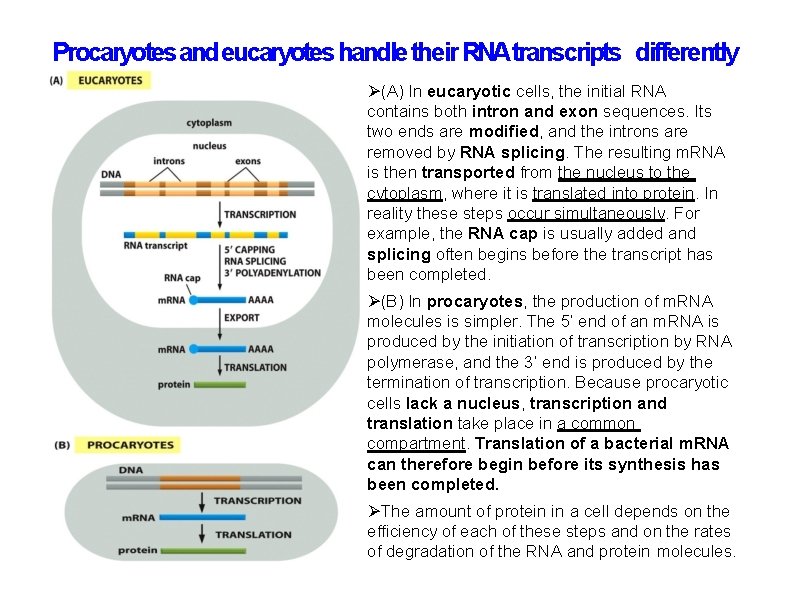

Procaryotes and eucaryotes handle their RNAtranscripts differently (A) In eucaryotic cells, the initial RNA contains both intron and exon sequences. Its two ends are modified, and the introns are removed by RNA splicing. The resulting m. RNA is then transported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, where it is translated into protein. In reality these steps occur simultaneously. For example, the RNA cap is usually added and splicing often begins before the transcript has been completed. (B) In procaryotes, the production of m. RNA molecules is simpler. The 5’ end of an m. RNA is produced by the initiation of transcription by RNA polymerase, and the 3’ end is produced by the termination of transcription. Because procaryotic cells lack a nucleus, transcription and translation take place in a common compartment. Translation of a bacterial m. RNA can therefore begin before its synthesis has been completed. The amount of protein in a cell depends on the efficiency of each of these steps and on the rates of degradation of the RNA and protein molecules.

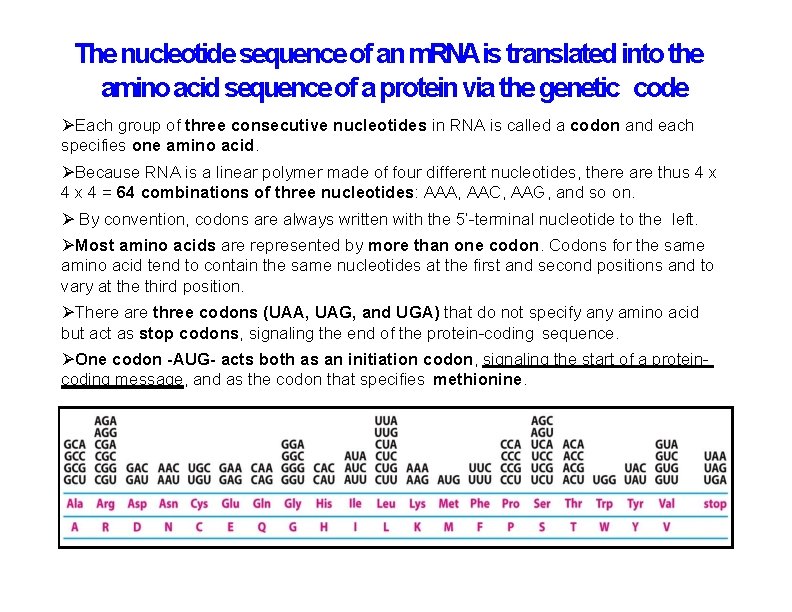

The nucleotide sequence of an m. RNAis translated into the amino acid sequence of a protein via the genetic code Each group of three consecutive nucleotides in RNA is called a codon and each specifies one amino acid. Because RNA is a linear polymer made of four different nucleotides, there are thus 4 x 4 = 64 combinations of three nucleotides: AAA, AAC, AAG, and so on. By convention, codons are always written with the 5’-terminal nucleotide to the left. Most amino acids are represented by more than one codon. Codons for the same amino acid tend to contain the same nucleotides at the first and second positions and to vary at the third position. There are three codons (UAA, UAG, and UGA) that do not specify any amino acid but act as stop codons, signaling the end of the protein-coding sequence. One codon -AUG- acts both as an initiation codon, signaling the start of a proteincoding message, and as the codon that specifies methionine.

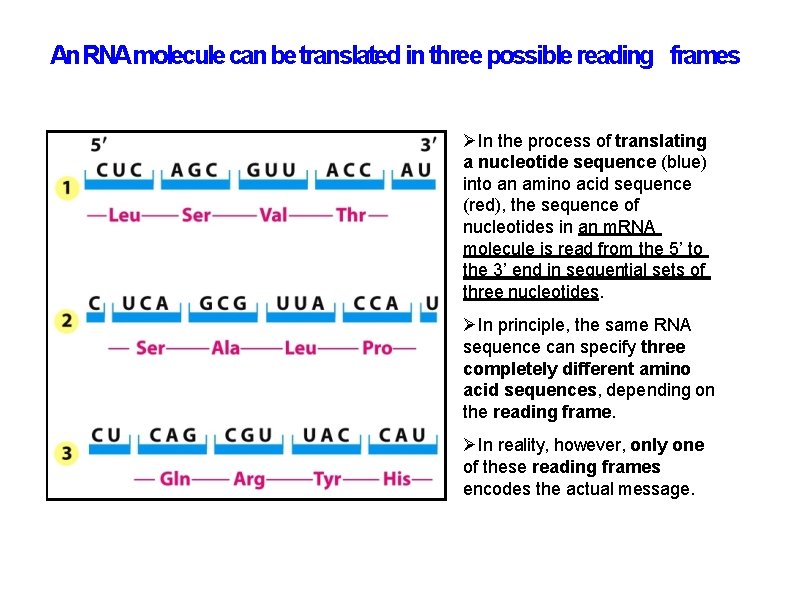

An RNAmolecule can be translated in three possible reading frames In the process of translating a nucleotide sequence (blue) into an amino acid sequence (red), the sequence of nucleotides in an m. RNA molecule is read from the 5’ to the 3’ end in sequential sets of three nucleotides. In principle, the same RNA sequence can specify three completely different amino acid sequences, depending on the reading frame. In reality, however, only one of these reading frames encodes the actual message.

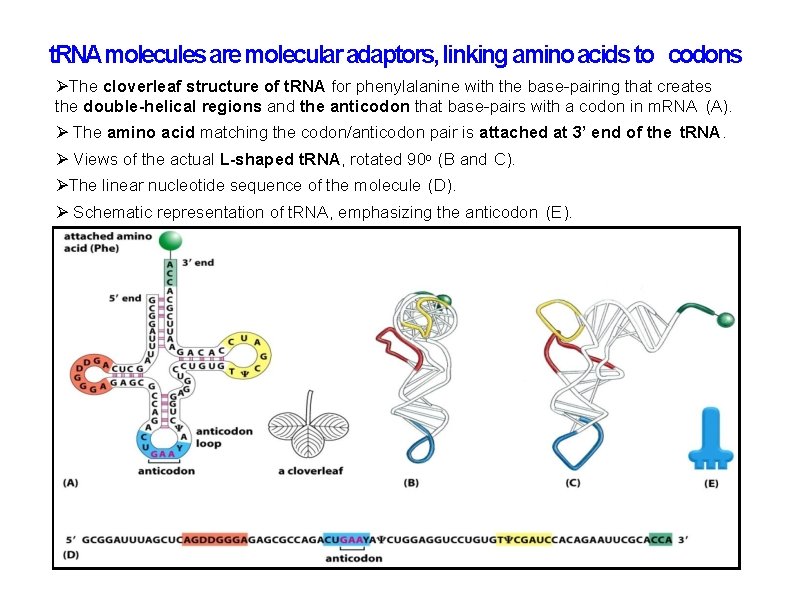

t. RNA molecules are molecular adaptors, linking amino acids to codons The cloverleaf structure of t. RNA for phenylalanine with the base-pairing that creates the double-helical regions and the anticodon that base-pairs with a codon in m. RNA (A). The amino acid matching the codon/anticodon pair is attached at 3’ end of the t. RNA. Views of the actual L-shaped t. RNA, rotated 90 o (B and C). The linear nucleotide sequence of the molecule (D). Schematic representation of t. RNA, emphasizing the anticodon (E).

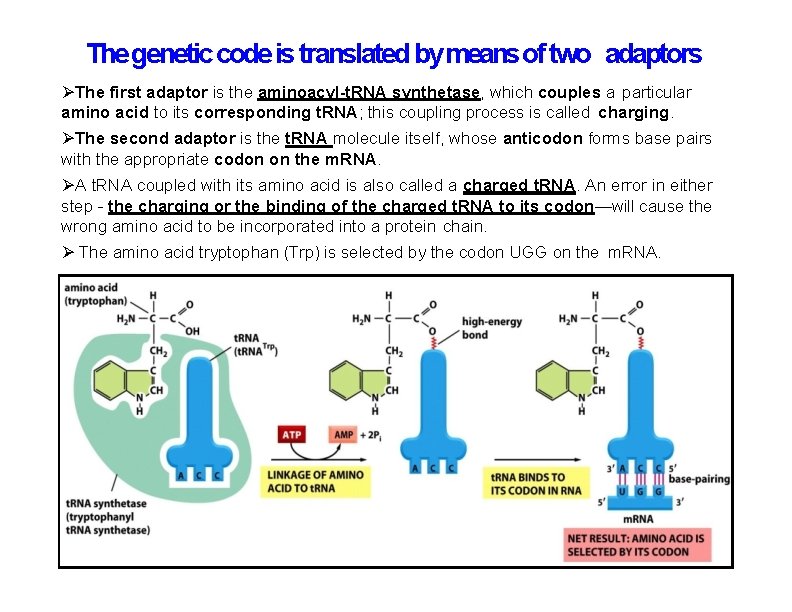

The genetic code is translated by means of two adaptors The first adaptor is the aminoacyl-t. RNA synthetase, which couples a particular amino acid to its corresponding t. RNA; this coupling process is called charging. The second adaptor is the t. RNA molecule itself, whose anticodon forms base pairs with the appropriate codon on the m. RNA. A t. RNA coupled with its amino acid is also called a charged t. RNA. An error in either step - the charging or the binding of the charged t. RNA to its codon—will cause the wrong amino acid to be incorporated into a protein chain. The amino acid tryptophan (Trp) is selected by the codon UGG on the m. RNA.

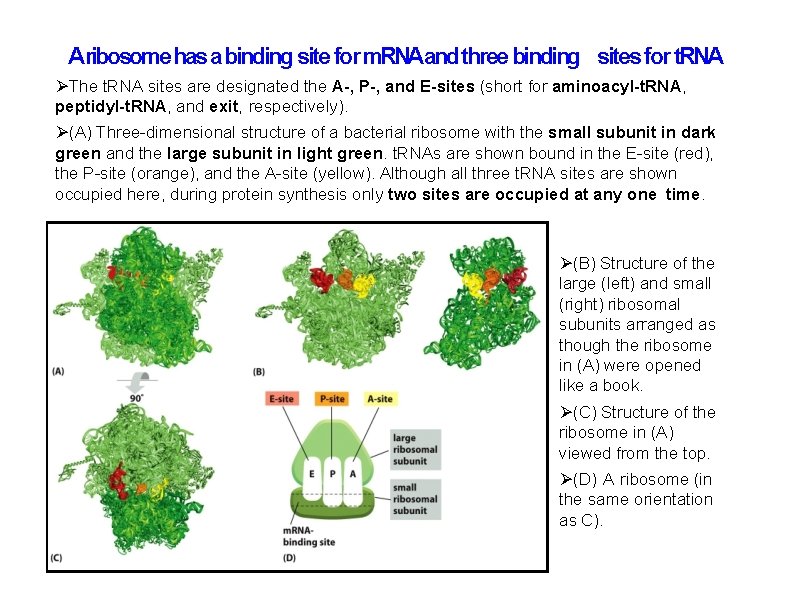

Aribosome has a binding site for m. RNAand three binding sites for t. RNA The t. RNA sites are designated the A-, P-, and E-sites (short for aminoacyl-t. RNA, peptidyl-t. RNA, and exit, respectively). (A) Three-dimensional structure of a bacterial ribosome with the small subunit in dark green and the large subunit in light green. t. RNAs are shown bound in the E-site (red), the P-site (orange), and the A-site (yellow). Although all three t. RNA sites are shown occupied here, during protein synthesis only two sites are occupied at any one time. (B) Structure of the large (left) and small (right) ribosomal subunits arranged as though the ribosome in (A) were opened like a book. (C) Structure of the ribosome in (A) viewed from the top. (D) A ribosome (in the same orientation as C).

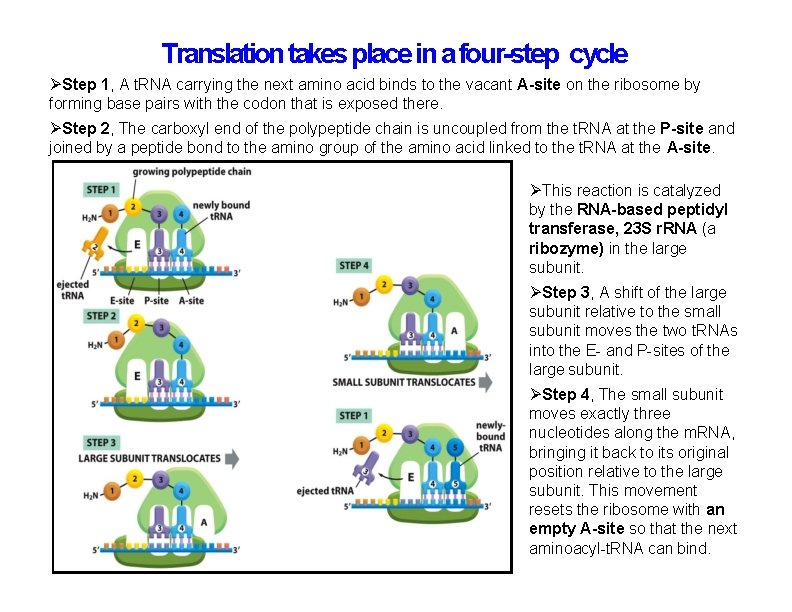

Translation takes place in a four-step cycle Step 1, A t. RNA carrying the next amino acid binds to the vacant A-site on the ribosome by forming base pairs with the codon that is exposed there. Step 2, The carboxyl end of the polypeptide chain is uncoupled from the t. RNA at the P-site and joined by a peptide bond to the amino group of the amino acid linked to the t. RNA at the A-site. This reaction is catalyzed by the RNA-based peptidyl transferase, 23 S r. RNA (a ribozyme) in the large subunit. Step 3, A shift of the large subunit relative to the small subunit moves the two t. RNAs into the E- and P-sites of the large subunit. Step 4, The small subunit moves exactly three nucleotides along the m. RNA, bringing it back to its original position relative to the large subunit. This movement resets the ribosome with an empty A-site so that the next aminoacyl-t. RNA can bind.

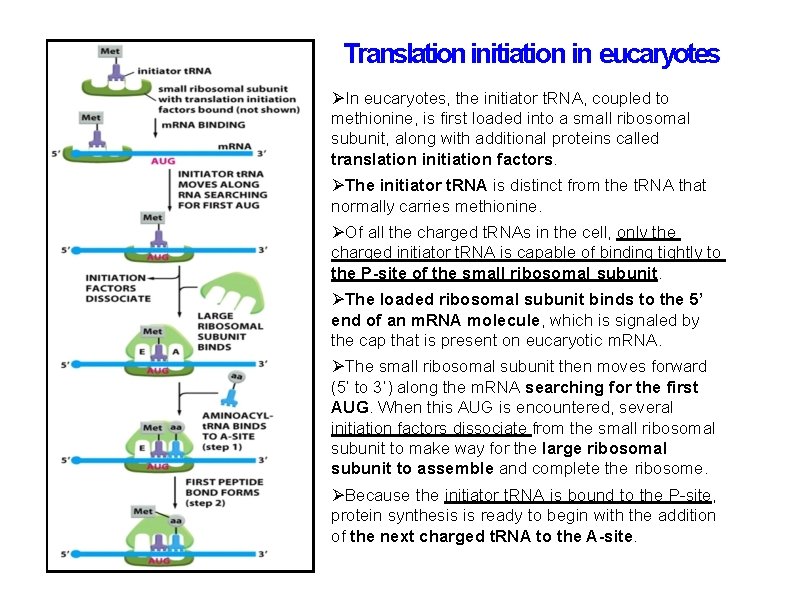

Translation initiation in eucaryotes In eucaryotes, the initiator t. RNA, coupled to methionine, is first loaded into a small ribosomal subunit, along with additional proteins called translation initiation factors. The initiator t. RNA is distinct from the t. RNA that normally carries methionine. Of all the charged t. RNAs in the cell, only the charged initiator t. RNA is capable of binding tightly to the P-site of the small ribosomal subunit. The loaded ribosomal subunit binds to the 5’ end of an m. RNA molecule, which is signaled by the cap that is present on eucaryotic m. RNA. The small ribosomal subunit then moves forward (5’ to 3’) along the m. RNA searching for the first AUG. When this AUG is encountered, several initiation factors dissociate from the small ribosomal subunit to make way for the large ribosomal subunit to assemble and complete the ribosome. Because the initiator t. RNA is bound to the P-site, protein synthesis is ready to begin with the addition of the next charged t. RNA to the A-site.

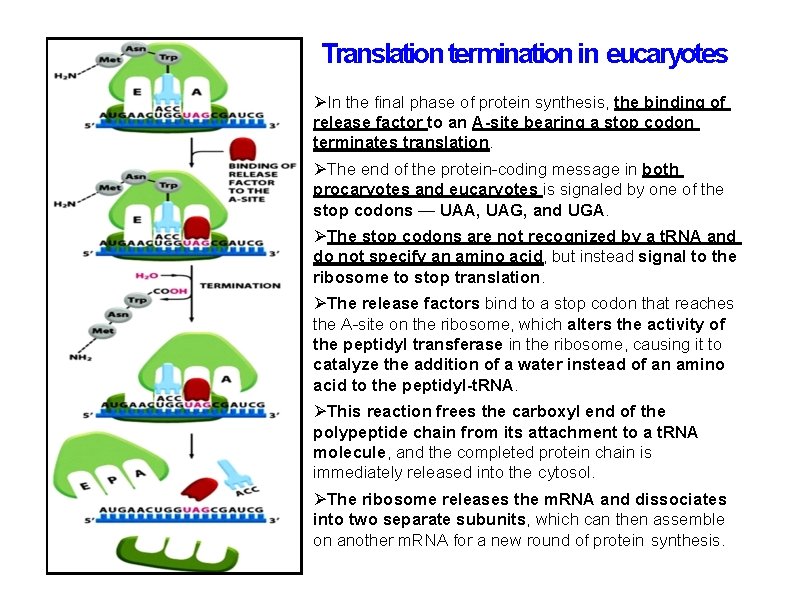

Translation termination in eucaryotes In the final phase of protein synthesis, the binding of release factor to an A-site bearing a stop codon terminates translation. The end of the protein-coding message in both procaryotes and eucaryotes is signaled by one of the stop codons — UAA, UAG, and UGA. The stop codons are not recognized by a t. RNA and do not specify an amino acid, but instead signal to the ribosome to stop translation. The release factors bind to a stop codon that reaches the A-site on the ribosome, which alters the activity of the peptidyl transferase in the ribosome, causing it to catalyze the addition of a water instead of an amino acid to the peptidyl-t. RNA. This reaction frees the carboxyl end of the polypeptide chain from its attachment to a t. RNA molecule, and the completed protein chain is immediately released into the cytosol. The ribosome releases the m. RNA and dissociates into two separate subunits, which can then assemble on another m. RNA for a new round of protein synthesis.

- Slides: 31