CDA 3101 Spring 2020 Introduction to Computer Organization

- Slides: 32

CDA 3101 Spring 2020 Introduction to Computer Organization Procedure Support & Number Representations 28 January 2020

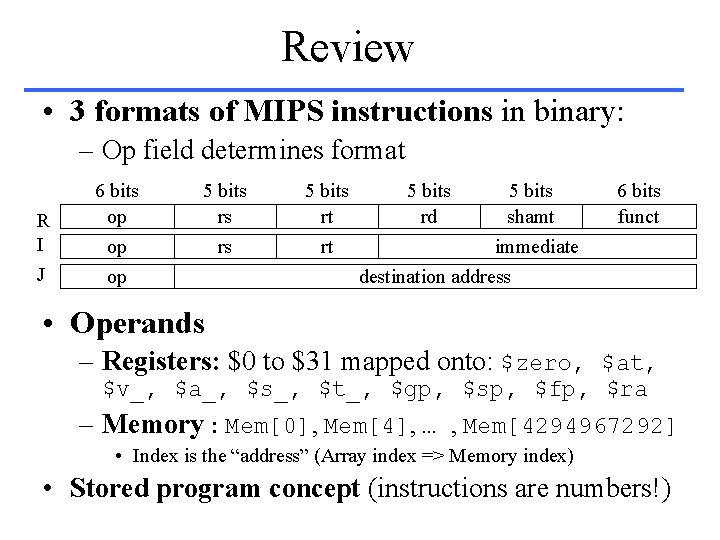

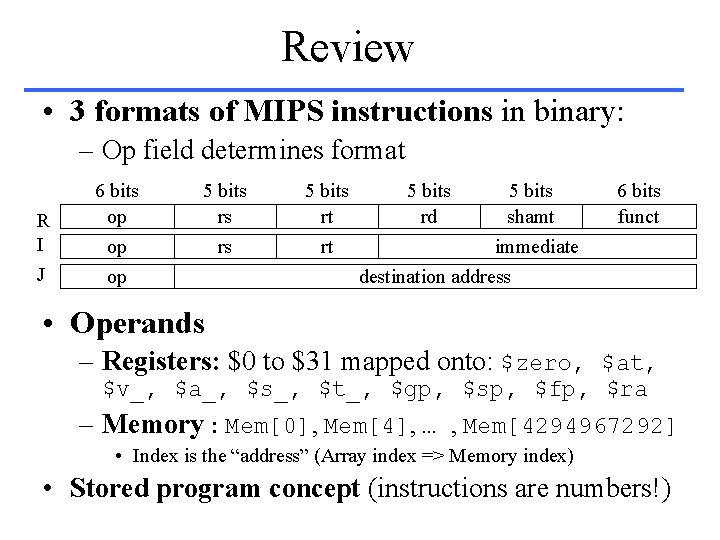

Review • 3 formats of MIPS instructions in binary: – Op field determines format R I J 6 bits op op op 5 bits rs rs 5 bits rt rt 5 bits rd 5 bits shamt immediate destination address 6 bits funct • Operands – Registers: $0 to $31 mapped onto: $zero, $at, $v_, $a_, $s_, $t_, $gp, $sp, $fp, $ra – Memory : Mem[0], Mem[4], … , Mem[4294967292] • Index is the “address” (Array index => Memory index) • Stored program concept (instructions are numbers!)

Overview • • Memory layout C functions MIPS support (instructions) for procedures The stack Procedure Conventions Manual Compilation Conclusion

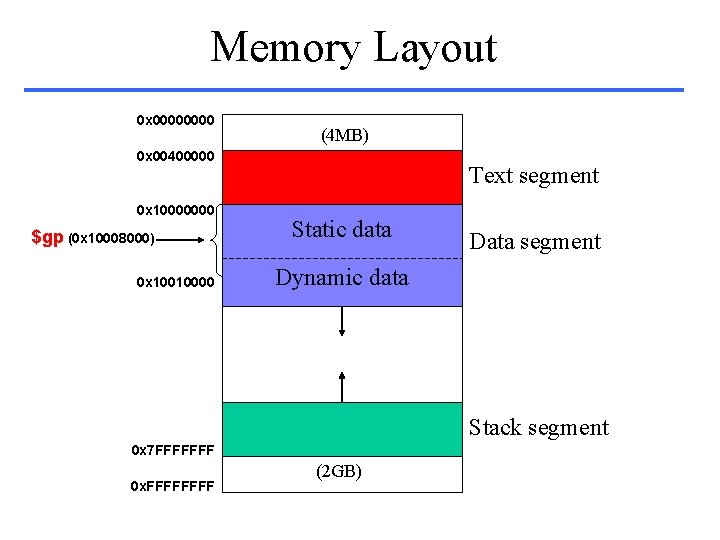

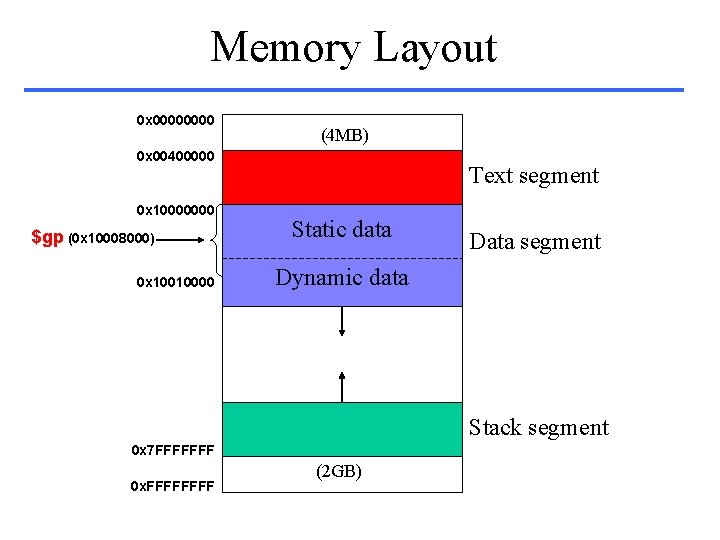

Memory Layout 0 x 0000 (4 MB) 0 x 00400000 0 x 10000000 $gp (0 x 10008000) 0 x 10010000 Text segment Static data Data segment Dynamic data Stack segment 0 x 7 FFFFFFF 0 x. FFFF (2 GB)

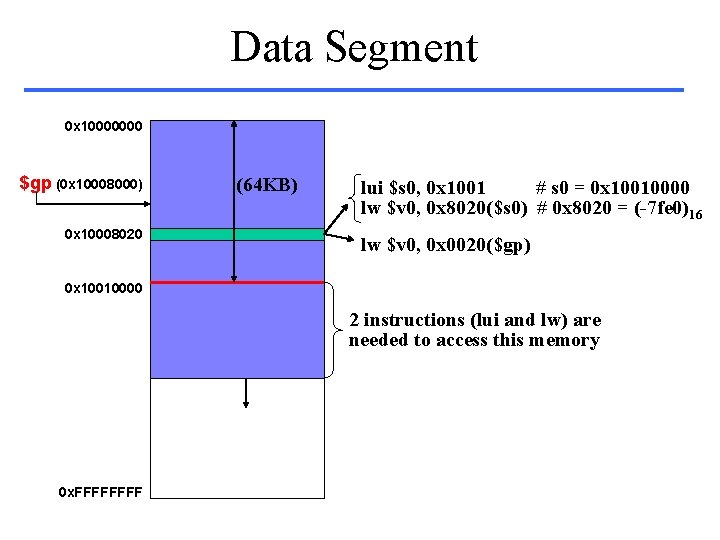

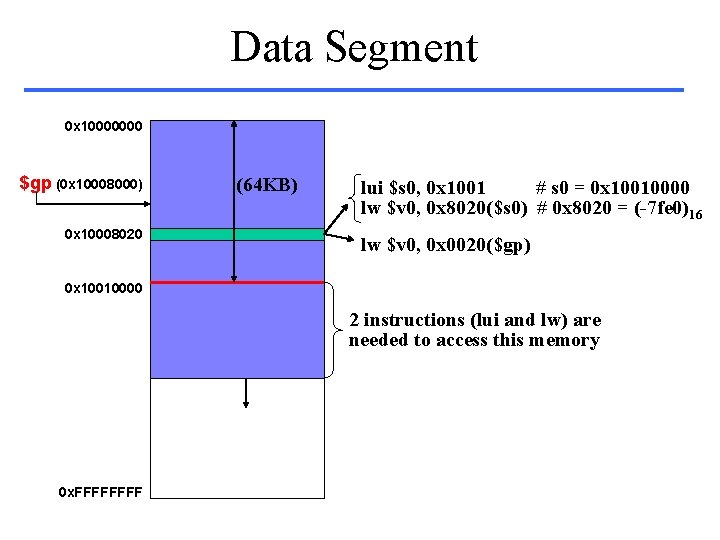

Data Segment 0 x 10000000 $gp (0 x 10008000) 0 x 10008020 (64 KB) lui $s 0, 0 x 1001 # s 0 = 0 x 10010000 lw $v 0, 0 x 8020($s 0) # 0 x 8020 = (-7 fe 0)16 lw $v 0, 0 x 0020($gp) 0 x 10010000 2 instructions (lui and lw) are needed to access this memory 0 x. FFFF

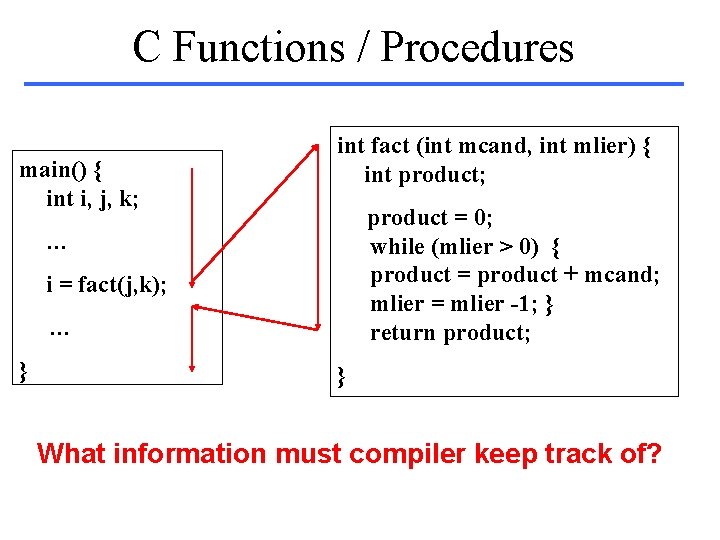

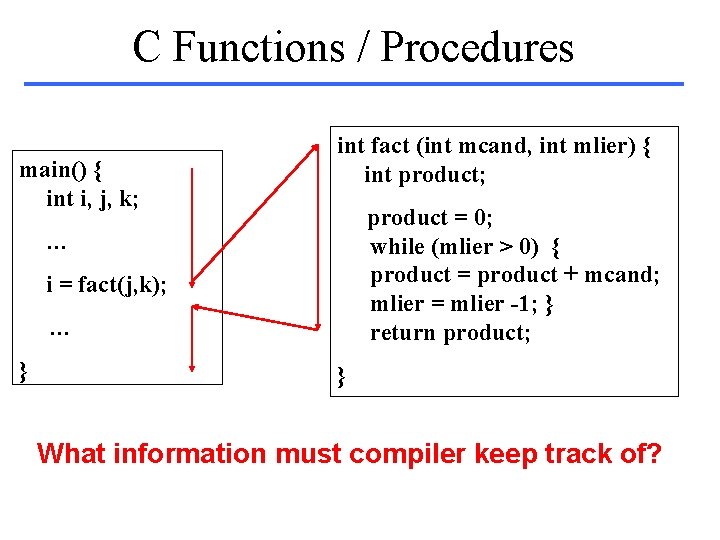

C Functions / Procedures main() { int i, j, k; int fact (int mcand, int mlier) { int product; product = 0; while (mlier > 0) { product = product + mcand; mlier = mlier -1; } return product; … i = fact(j, k); … } } What information must compiler keep track of?

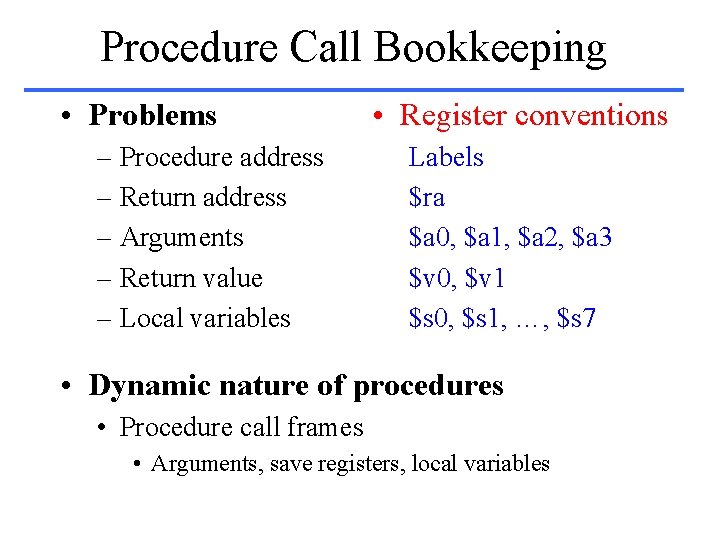

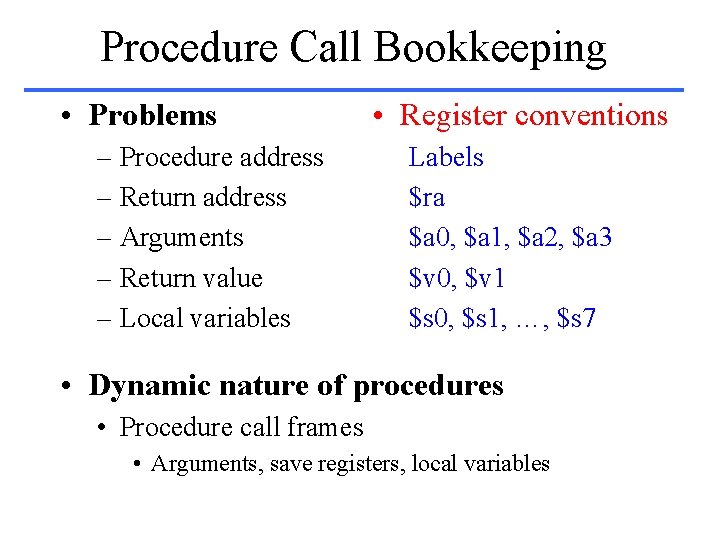

Procedure Call Bookkeeping • Problems – Procedure address – Return address – Arguments – Return value – Local variables • Register conventions Labels $ra $a 0, $a 1, $a 2, $a 3 $v 0, $v 1 $s 0, $s 1, …, $s 7 • Dynamic nature of procedures • Procedure call frames • Arguments, save registers, local variables

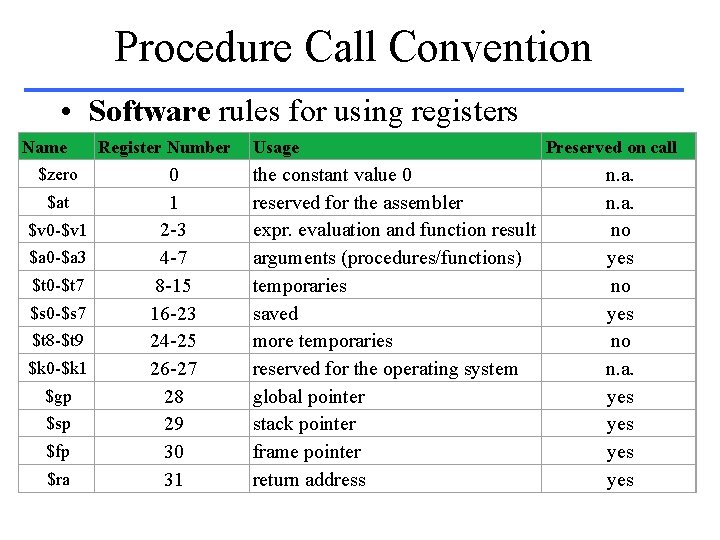

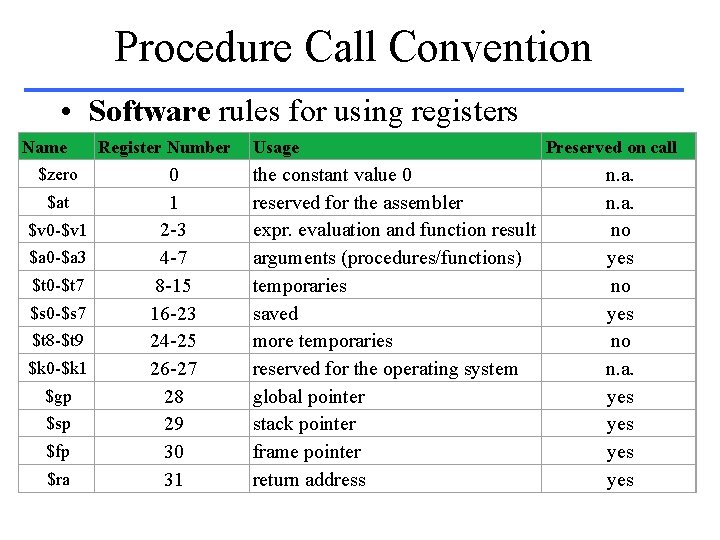

Procedure Call Convention • Software rules for using registers Name $zero $at $v 0 -$v 1 $a 0 -$a 3 $t 0 -$t 7 $s 0 -$s 7 $t 8 -$t 9 $k 0 -$k 1 $gp $sp $fp $ra Register Number 0 1 2 -3 4 -7 8 -15 16 -23 24 -25 26 -27 28 29 30 31 Usage the constant value 0 reserved for the assembler expr. evaluation and function result arguments (procedures/functions) temporaries saved more temporaries reserved for the operating system global pointer stack pointer frame pointer return address Preserved on call n. a. no yes no n. a. yes yes

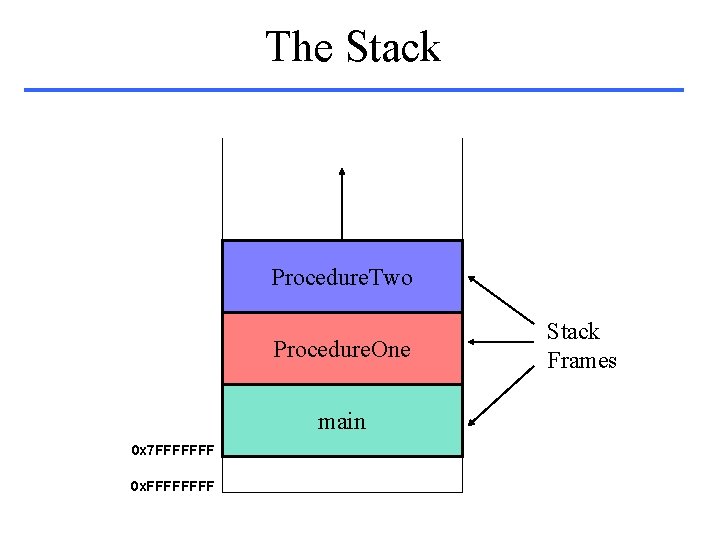

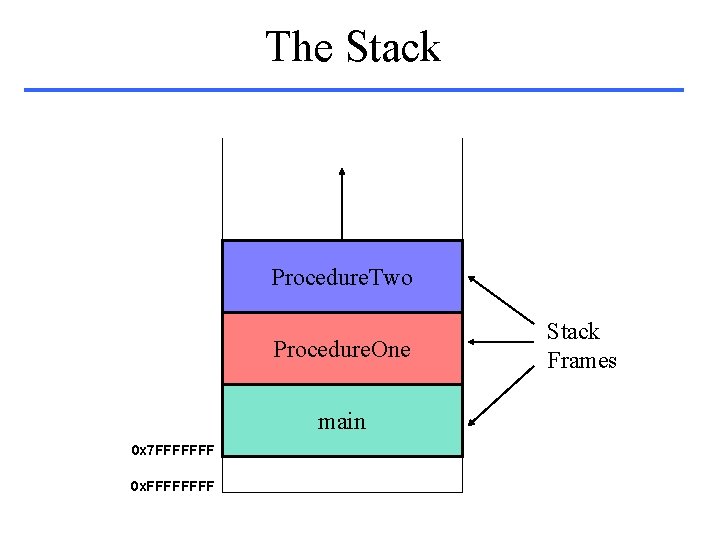

The Stack Procedure. Two Procedure. One main 0 x 7 FFFFFFF 0 x. FFFF Stack Frames

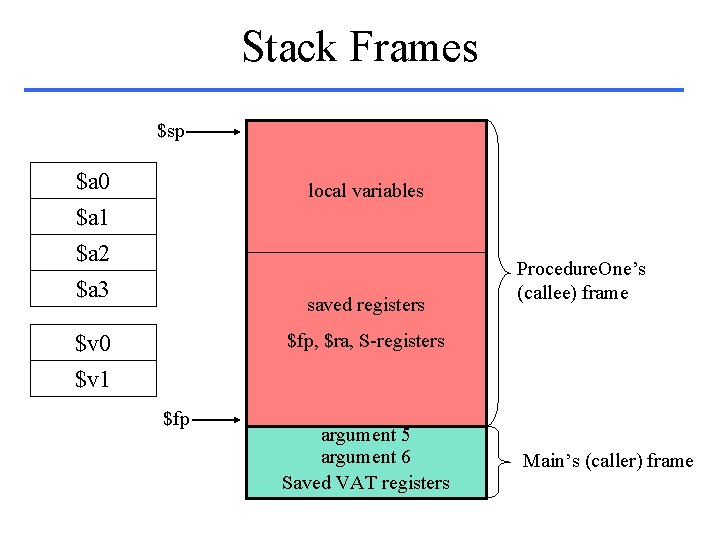

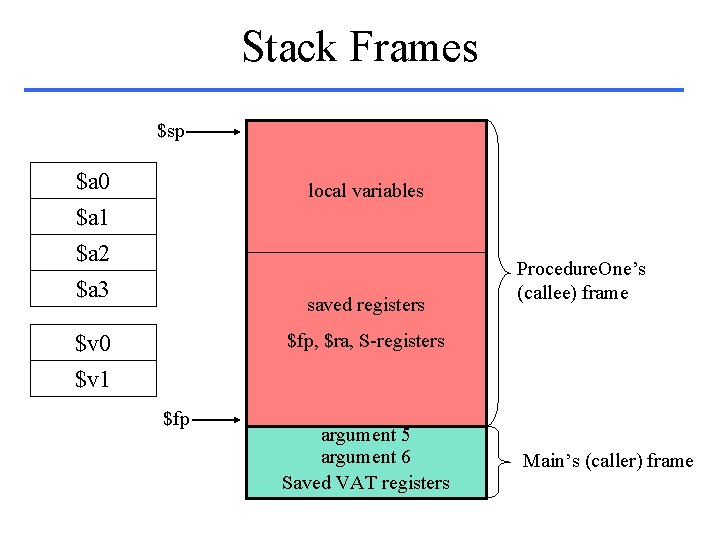

Stack Frames $sp $a 0 $a 1 $a 2 $a 3 local variables saved registers Procedure. One’s (callee) frame $fp, $ra, S-registers $v 0 $v 1 $fp argument 5 argument 6 Saved VAT registers Main’s (caller) frame

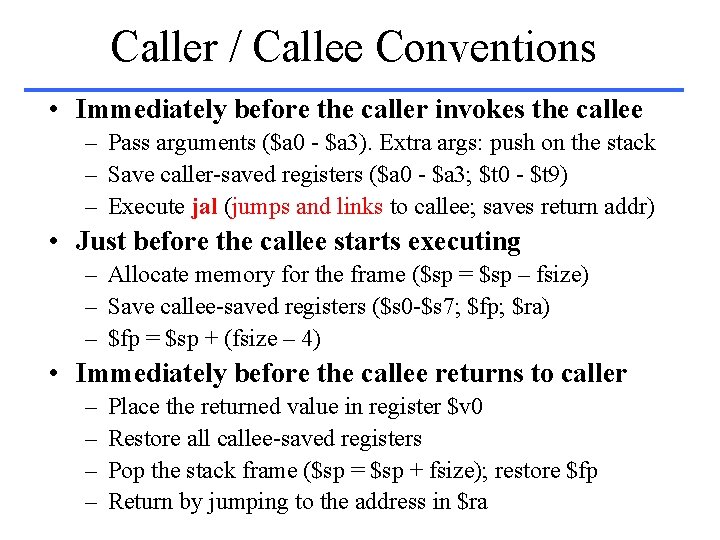

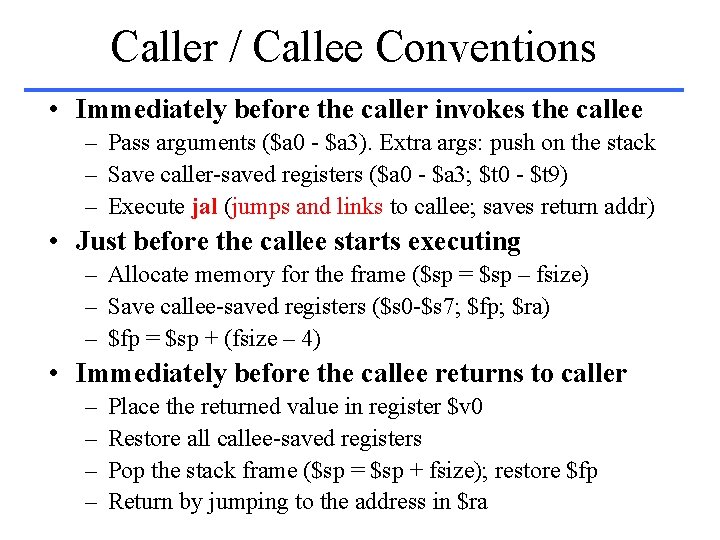

Caller / Callee Conventions • Immediately before the caller invokes the callee – Pass arguments ($a 0 - $a 3). Extra args: push on the stack – Save caller-saved registers ($a 0 - $a 3; $t 0 - $t 9) – Execute jal (jumps and links to callee; saves return addr) • Just before the callee starts executing – Allocate memory for the frame ($sp = $sp – fsize) – Save callee-saved registers ($s 0 -$s 7; $fp; $ra) – $fp = $sp + (fsize – 4) • Immediately before the callee returns to caller – – Place the returned value in register $v 0 Restore all callee-saved registers Pop the stack frame ($sp = $sp + fsize); restore $fp Return by jumping to the address in $ra

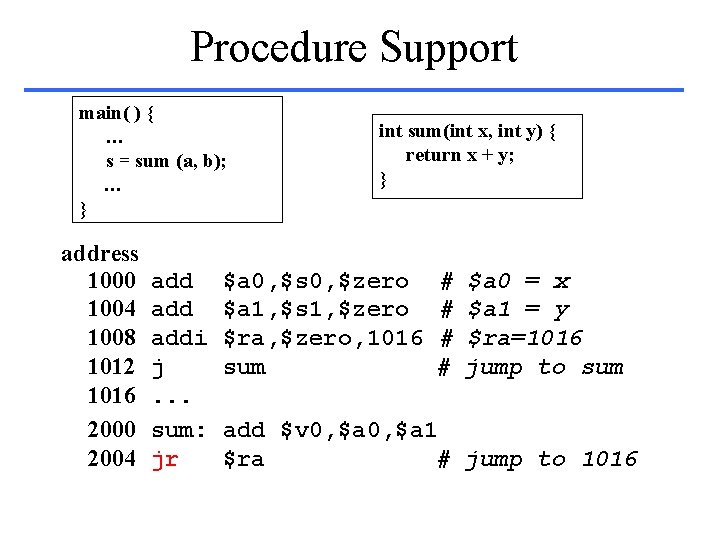

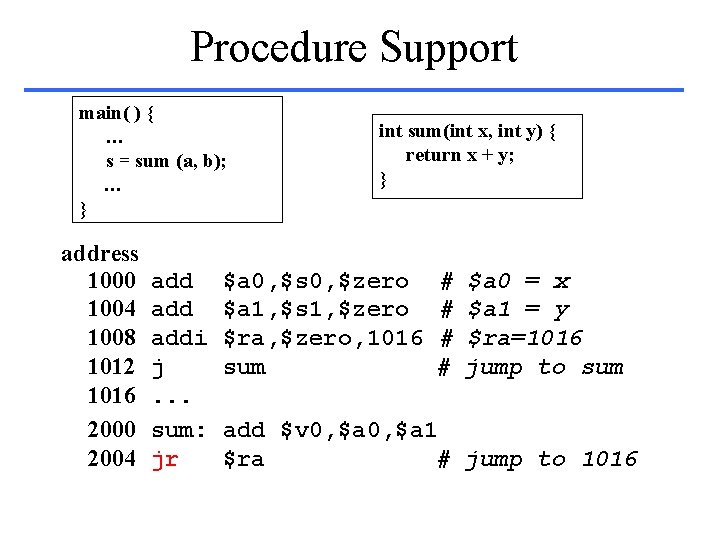

Procedure Support main( ) { … s = sum (a, b); … } address 1000 1004 1008 1012 1016 2000 2004 add addi j. . . sum: jr int sum(int x, int y) { return x + y; } $a 0, $s 0, $zero $a 1, $s 1, $zero $ra, $zero, 1016 sum # # $a 0 = x $a 1 = y $ra=1016 jump to sum add $v 0, $a 1 $ra # jump to 1016

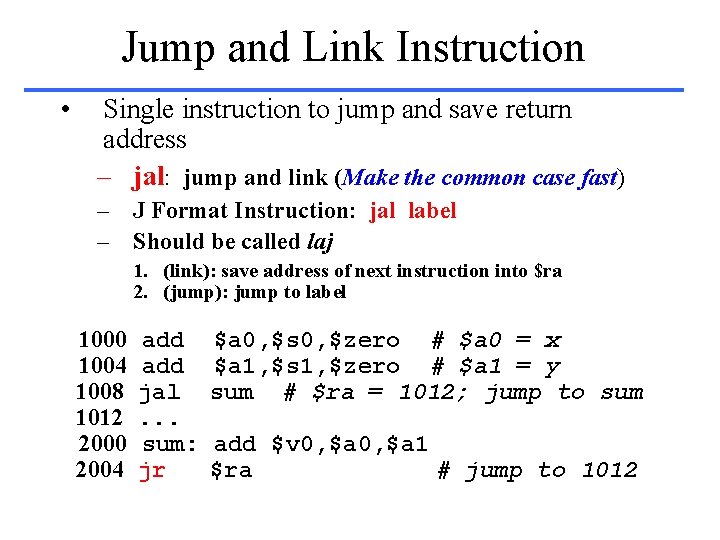

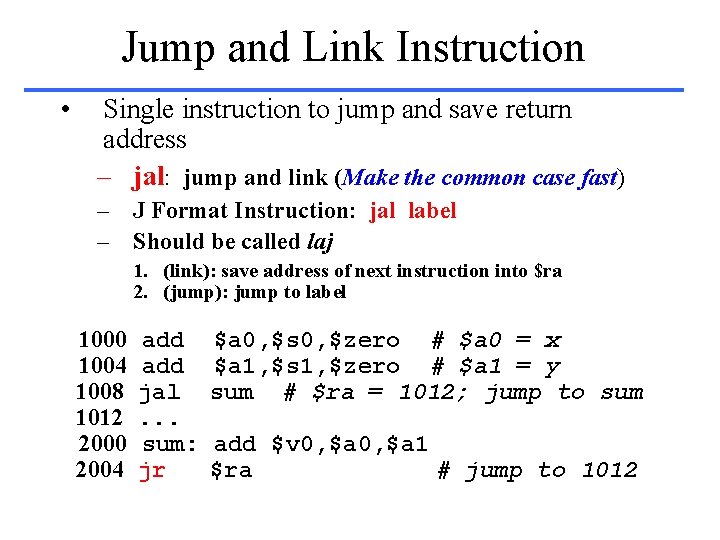

Jump and Link Instruction • Single instruction to jump and save return address – jal: jump and link (Make the common case fast) – J Format Instruction: jal label – Should be called laj 1. (link): save address of next instruction into $ra 2. (jump): jump to label 1000 1004 1008 1012 2000 2004 add jal. . . sum: jr $a 0, $s 0, $zero # $a 0 = x $a 1, $s 1, $zero # $a 1 = y sum # $ra = 1012; jump to sum add $v 0, $a 1 $ra # jump to 1012

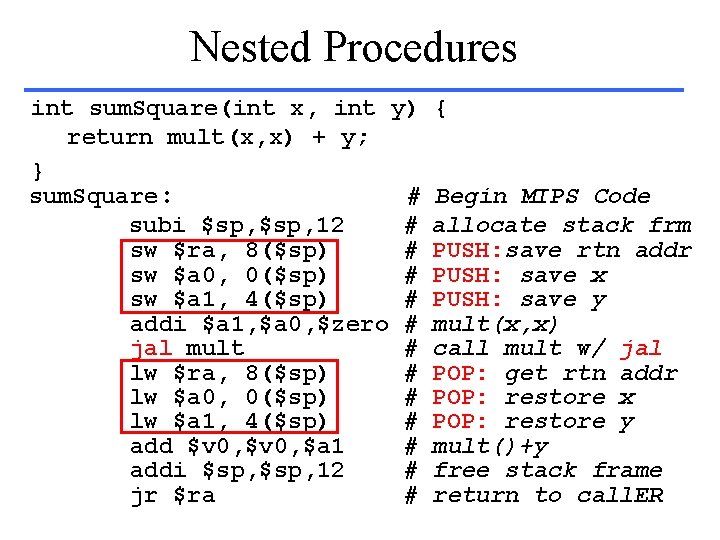

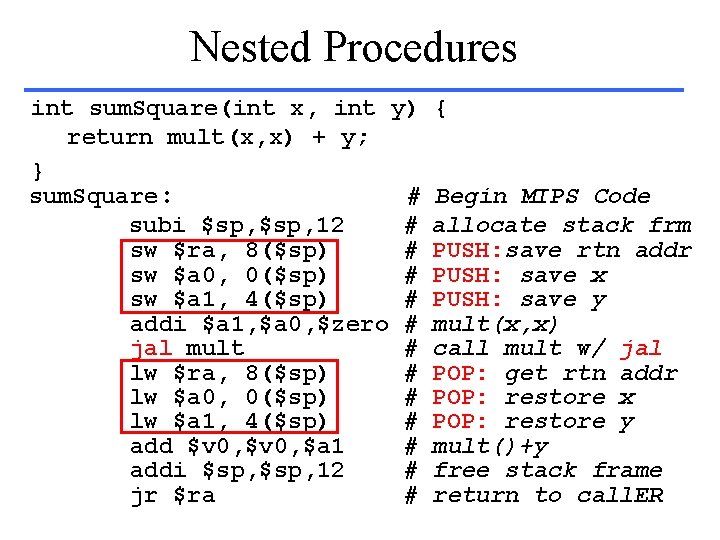

Nested Procedures int sum. Square(int x, int y) return mult(x, x) + y; } sum. Square: # subi $sp, 12 # sw $ra, 8($sp) # sw $a 0, 0($sp) # sw $a 1, 4($sp) # addi $a 1, $a 0, $zero # jal mult # lw $ra, 8($sp) # lw $a 0, 0($sp) # lw $a 1, 4($sp) # add $v 0, $a 1 # addi $sp, 12 # jr $ra # { Begin MIPS Code allocate stack frm PUSH: save rtn addr PUSH: save x PUSH: save y mult(x, x) call mult w/ jal POP: get rtn addr POP: restore x POP: restore y mult()+y free stack frame return to call. ER

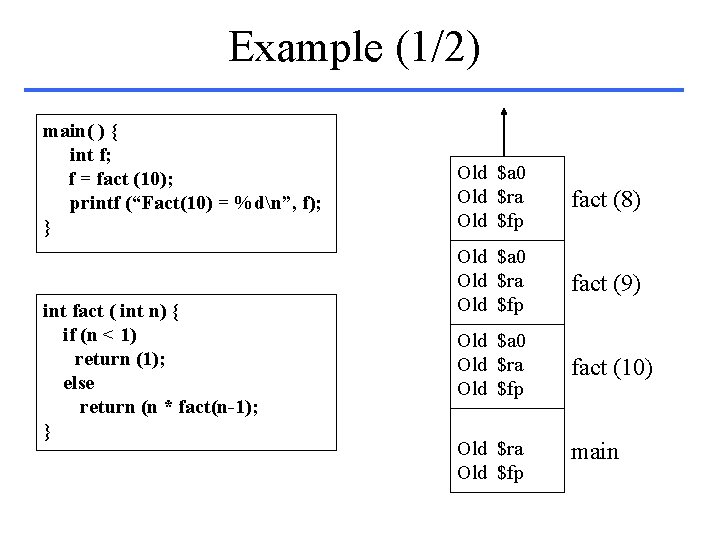

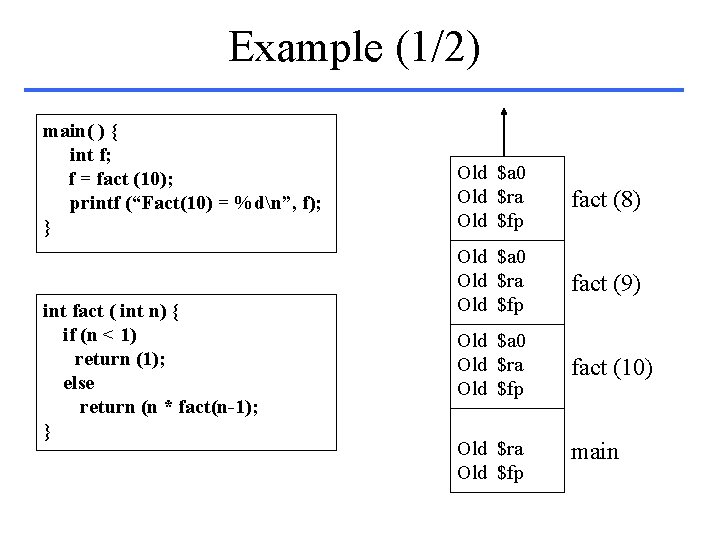

Example (1/2) main( ) { int f; f = fact (10); printf (“Fact(10) = %dn”, f); } int fact ( int n) { if (n < 1) return (1); else return (n * fact(n-1); } Old $a 0 Old $ra Old $fp fact (8) Old $a 0 Old $ra Old $fp fact (9) Old $a 0 Old $ra Old $fp fact (10) Old $ra Old $fp main

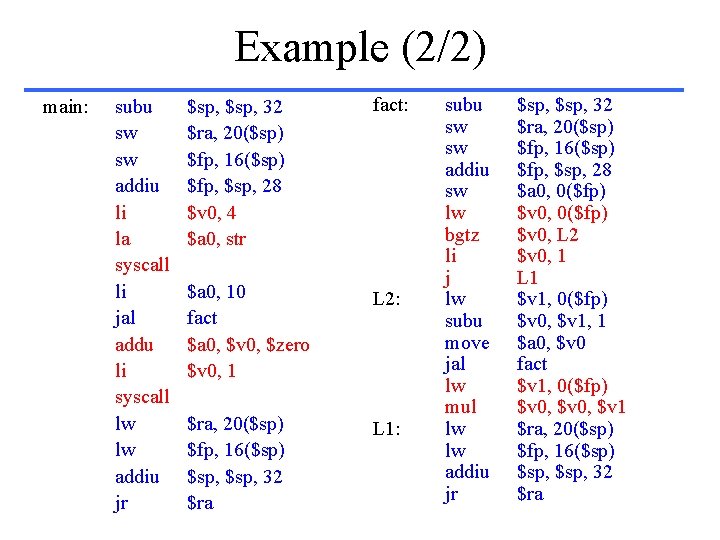

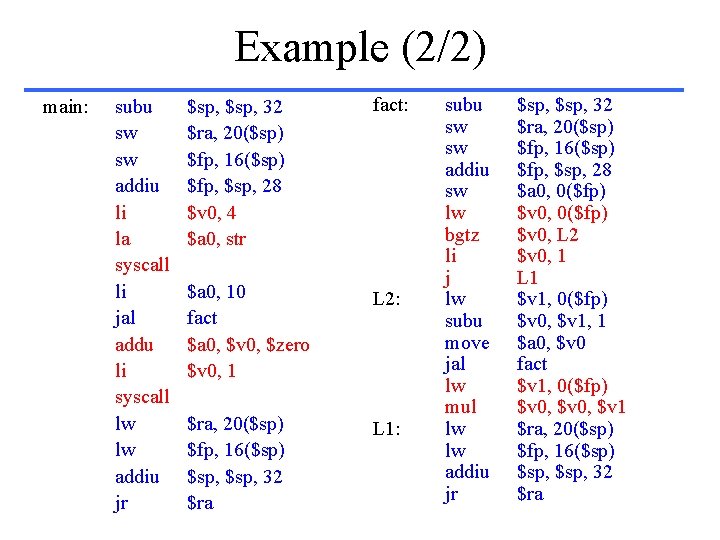

Example (2/2) main: subu sw sw addiu li la syscall li jal addu li syscall lw lw addiu jr $sp, 32 $ra, 20($sp) $fp, 16($sp) $fp, $sp, 28 $v 0, 4 $a 0, str fact: $a 0, 10 fact $a 0, $v 0, $zero $v 0, 1 L 2: $ra, 20($sp) $fp, 16($sp) $sp, 32 $ra L 1: subu sw sw addiu sw lw bgtz li j lw subu move jal lw mul lw lw addiu jr $sp, 32 $ra, 20($sp) $fp, 16($sp) $fp, $sp, 28 $a 0, 0($fp) $v 0, L 2 $v 0, 1 L 1 $v 1, 0($fp) $v 0, $v 1, 1 $a 0, $v 0 fact $v 1, 0($fp) $v 0, $v 1 $ra, 20($sp) $fp, 16($sp) $sp, 32 $ra

Summary • Caller / callee conventions – Rights and responsibilities – Callee uses VAT registers freely – Caller uses S registers without fear of being overwritten • Instruction support: jal label and jr $ra • Use stack to save anything you need. Remember to leave it the way you found it • Register conventions – Purpose and limits of the usage – Follow the rules even if you are writing all the code yourself

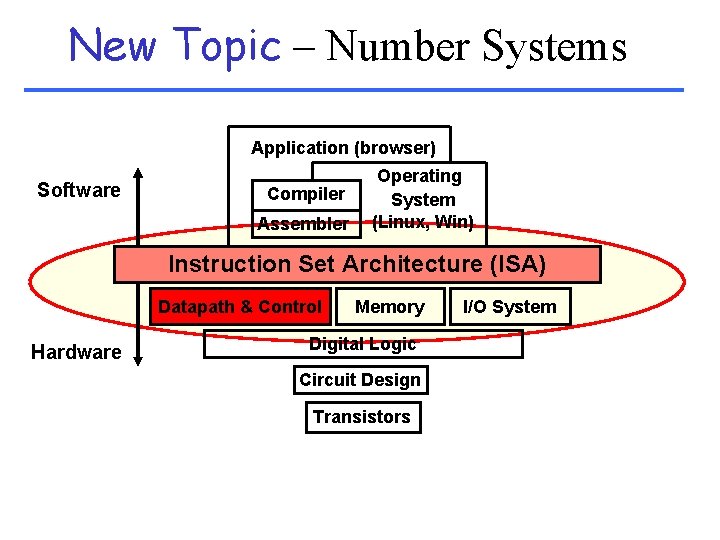

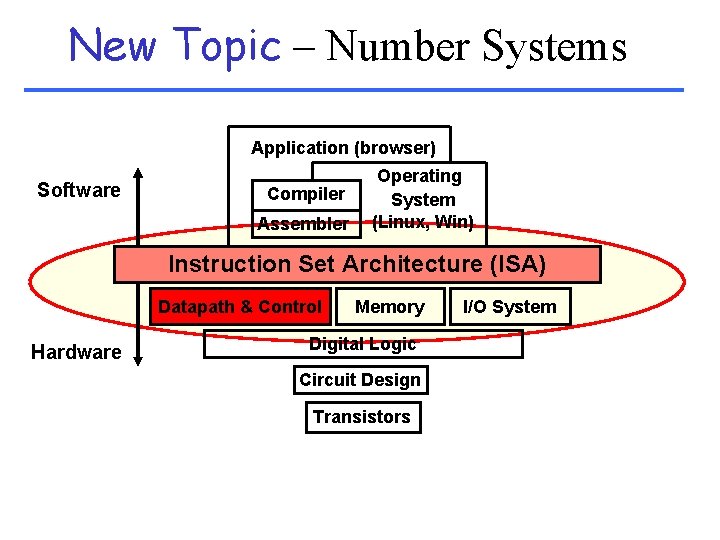

New Topic – Number Systems Application (browser) Software Compiler Assembler Operating System (Linux, Win) Instruction Set Architecture (ISA) Datapath & Control Hardware Memory Digital Logic Circuit Design Transistors I/O System

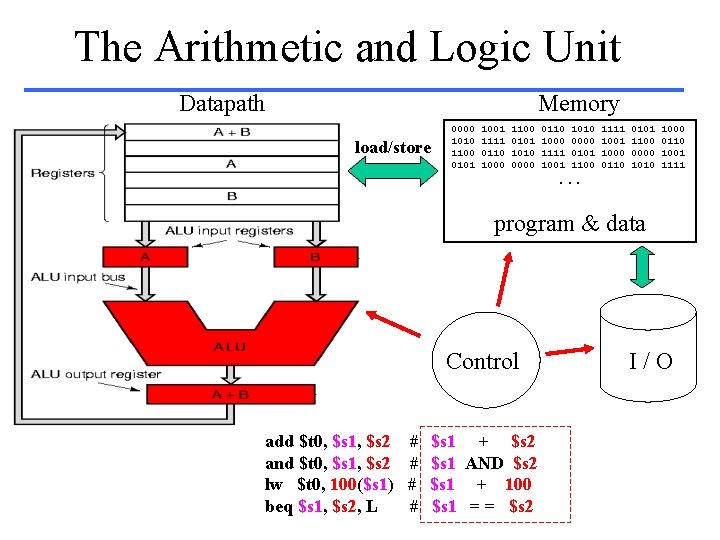

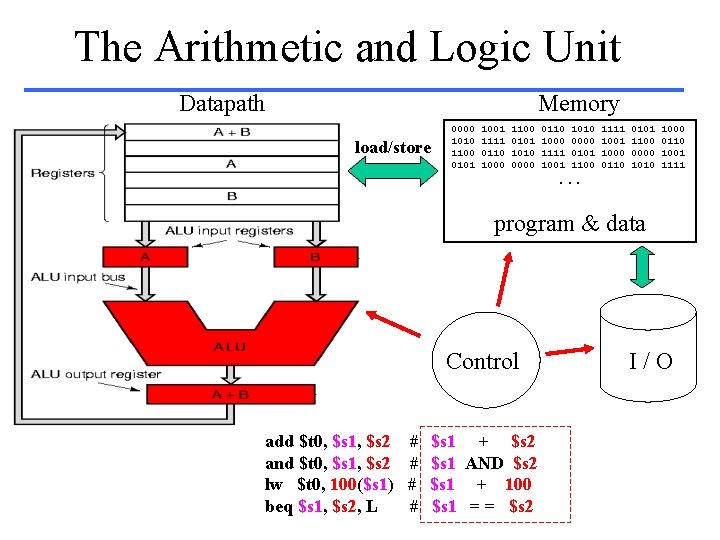

The Arithmetic and Logic Unit Datapath Memory load/store 0000 1010 1100 0101 1001 1111 0110 1000 1100 0101 1010 0000 0110 1000 1111 1001 1010 0000 0101 1100 1111 1000 0110 0101 1100 0000 1010 1000 0110 1001 1111 . . . program & data Control add $t 0, $s 1, $s 2 and $t 0, $s 1, $s 2 lw $t 0, 100($s 1) beq $s 1, $s 2, L # # $s 1 + $s 2 $s 1 AND $s 2 $s 1 + 100 $s 1 = = $s 2 I/O

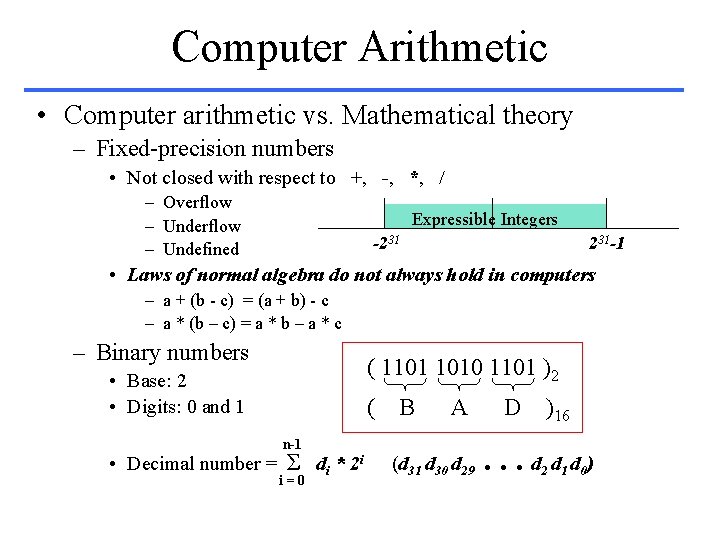

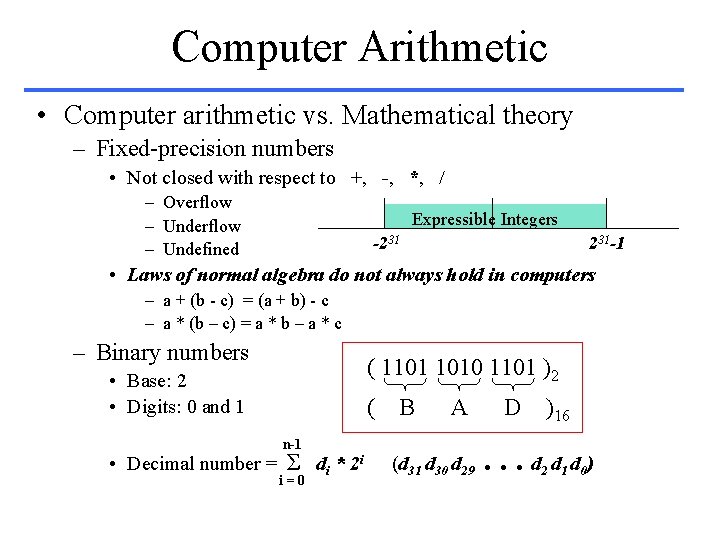

Computer Arithmetic • Computer arithmetic vs. Mathematical theory – Fixed-precision numbers • Not closed with respect to +, -, *, / – Overflow – Undefined Expressible Integers -231 231 -1 • Laws of normal algebra do not always hold in computers – a + (b - c) = (a + b) - c – a * (b – c) = a * b – a * c – Binary numbers ( 1101 1010 1101 )2 • Base: 2 • Digits: 0 and 1 ( B A n-1 • Decimal number = Σ di * 2 i i=0 (d 31 d 30 d 29 D )16 . . . d 2 d 1 d 0)

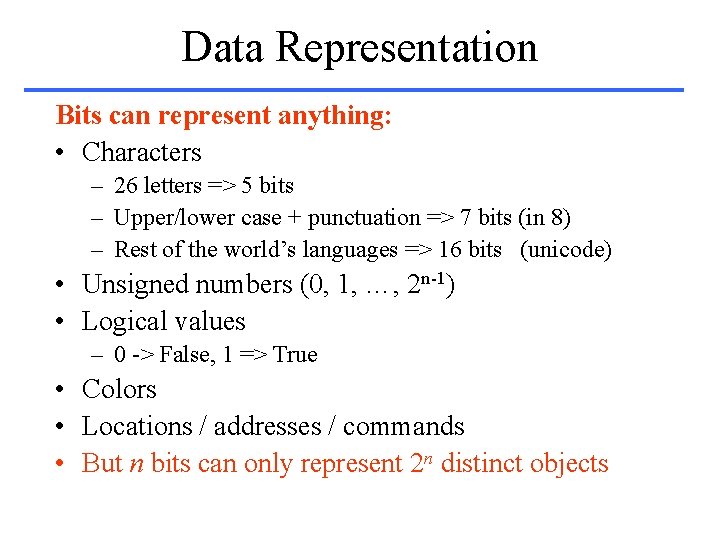

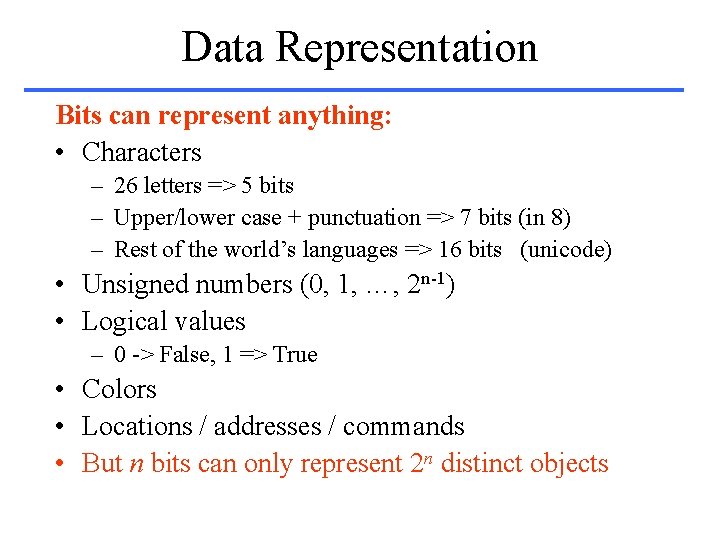

Data Representation Bits can represent anything: • Characters – 26 letters => 5 bits – Upper/lower case + punctuation => 7 bits (in 8) – Rest of the world’s languages => 16 bits (unicode) • Unsigned numbers (0, 1, …, 2 n-1) • Logical values – 0 -> False, 1 => True • Colors • Locations / addresses / commands • But n bits can only represent 2 n distinct objects

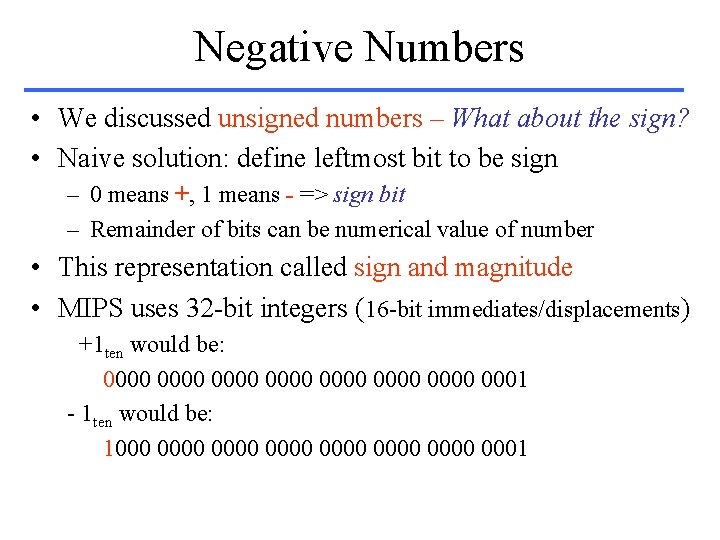

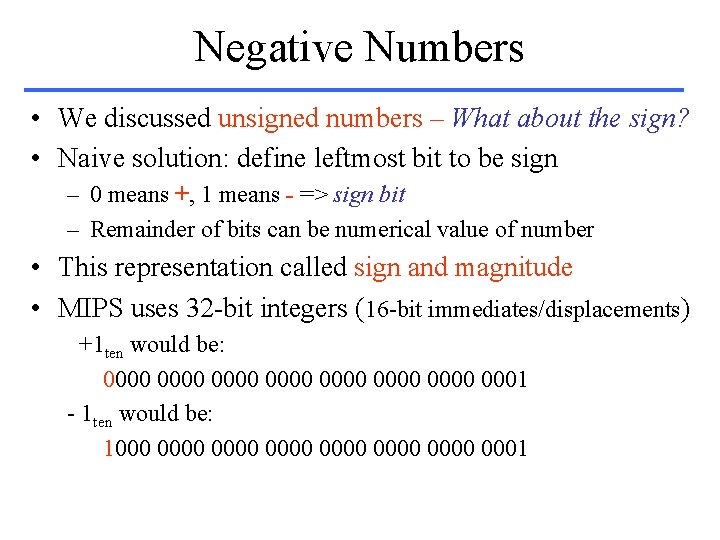

Negative Numbers • We discussed unsigned numbers – What about the sign? • Naive solution: define leftmost bit to be sign – 0 means +, 1 means - => sign bit – Remainder of bits can be numerical value of number • This representation called sign and magnitude • MIPS uses 32 -bit integers (16 -bit immediates/displacements) +1 ten would be: 0000 0000 0001 - 1 ten would be: 1000 0000 0000 0001

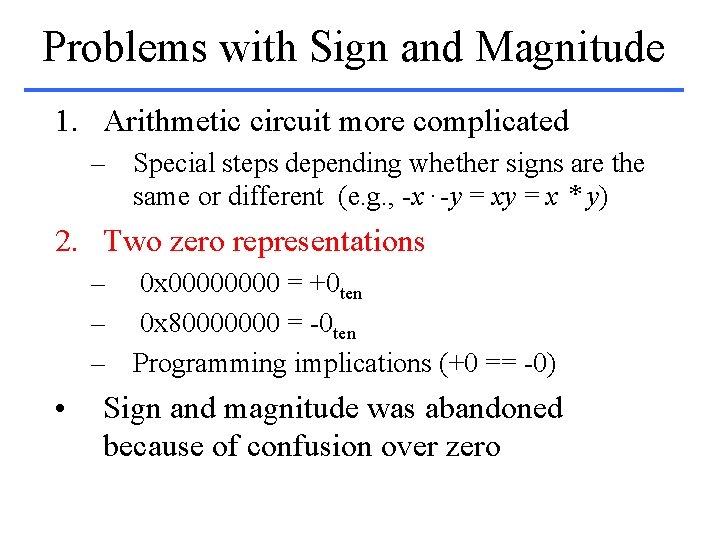

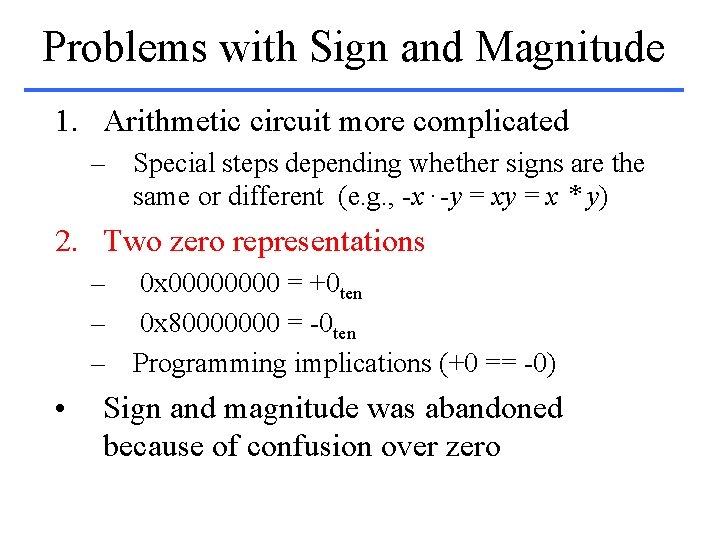

Problems with Sign and Magnitude 1. Arithmetic circuit more complicated – Special steps depending whether signs are the same or different (e. g. , -x. -y = x * y) 2. Two zero representations – 0 x 0000 = +0 ten – 0 x 80000000 = -0 ten – Programming implications (+0 == -0) • Sign and magnitude was abandoned because of confusion over zero

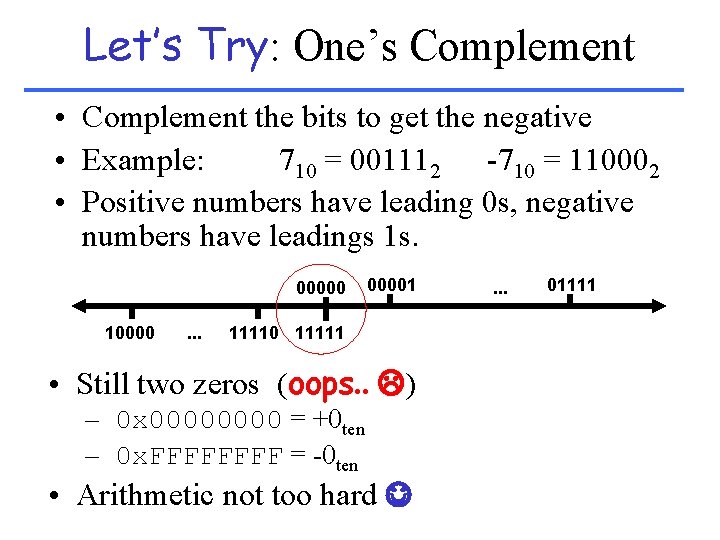

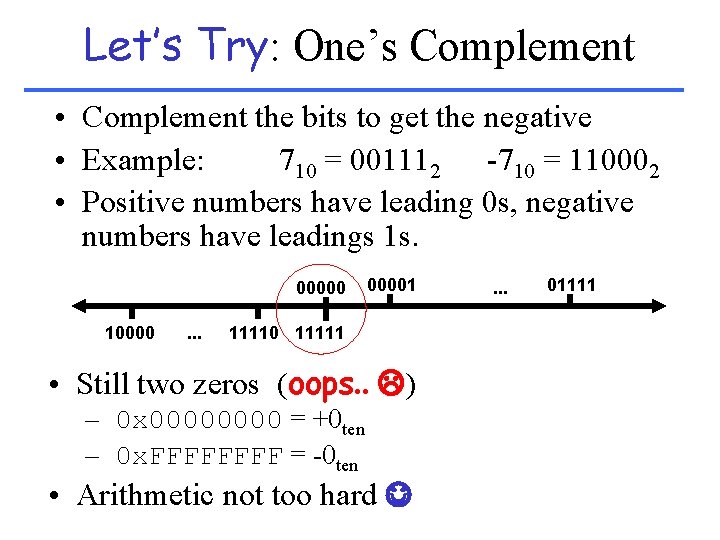

Let’s Try: One’s Complement • Complement the bits to get the negative • Example: 710 = 001112 -710 = 110002 • Positive numbers have leading 0 s, negative numbers have leadings 1 s. 00000 10000 . . . 00001 11110 11111 • Still two zeros (oops. . ) – 0 x 0000 = +0 ten – 0 x. FFFF = -0 ten • Arithmetic not too hard . . . 01111

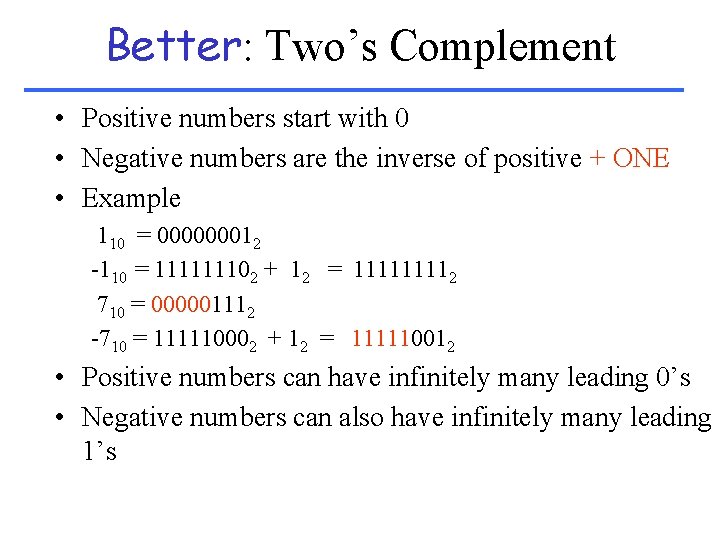

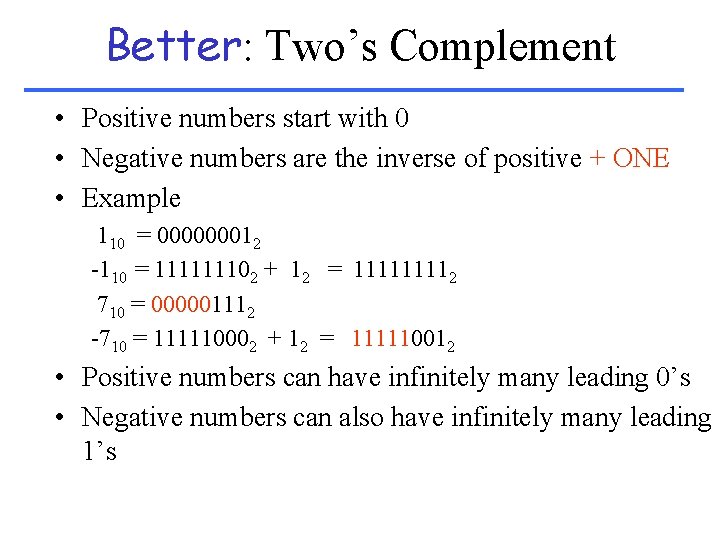

Better: Two’s Complement • Positive numbers start with 0 • Negative numbers are the inverse of positive + ONE • Example 110 = 000000012 -110 = 111111102 + 12 = 11112 710 = 000001112 -710 = 111110002 + 12 = 111110012 • Positive numbers can have infinitely many leading 0’s • Negative numbers can also have infinitely many leading 1’s

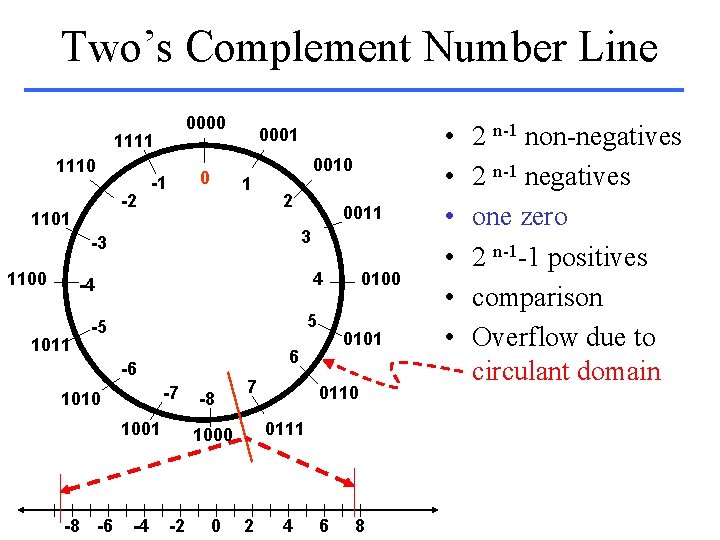

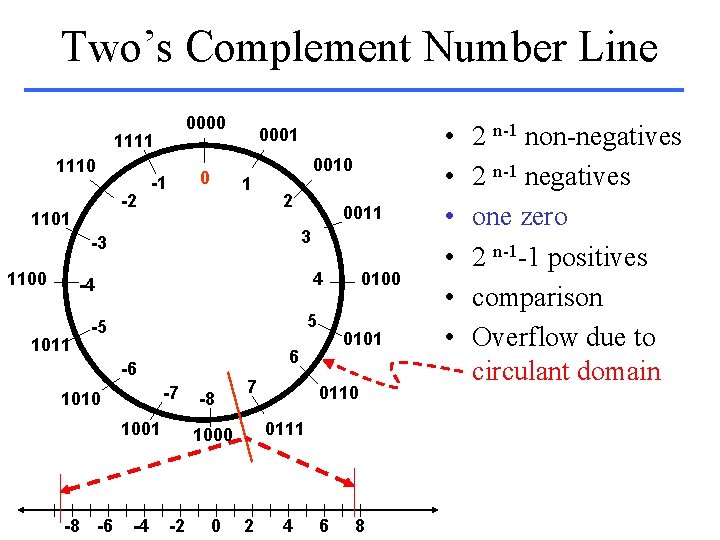

Two’s Complement Number Line 0000 1111 1110 -2 1101 0 -1 0001 1 0010 2 3 -3 1100 0011 4 -4 1011 5 -5 -7 1010 1001 -8 -6 -4 0101 6 -6 -8 7 0 0111 1000 -2 0100 2 4 6 8 • • • 2 n-1 non-negatives 2 n-1 negatives one zero 2 n-1 -1 positives comparison Overflow due to circulant domain

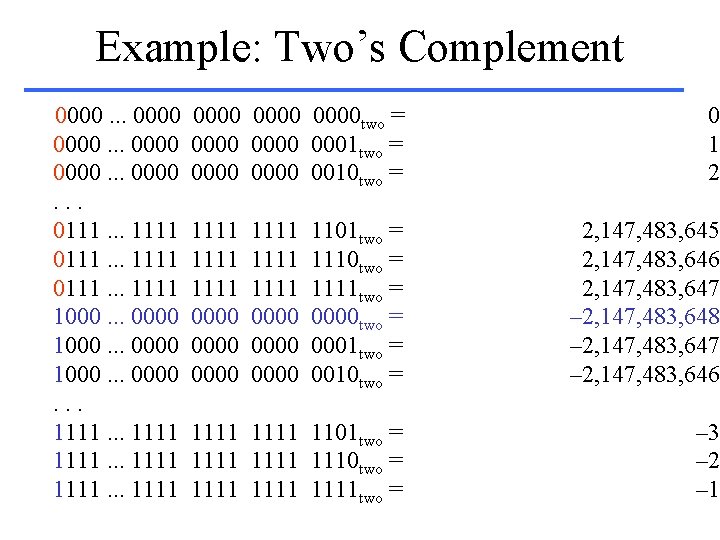

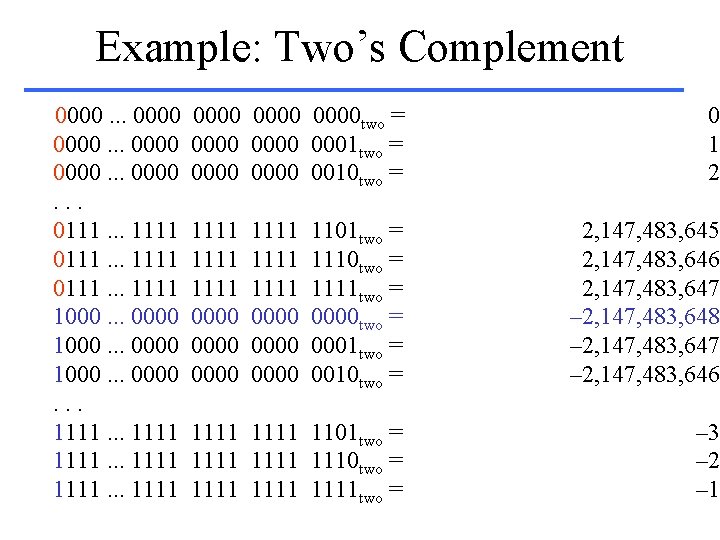

Example: Two’s Complement 0000. . . 0111. . . 1111 1000. . . 0000. . . 1111 0000 two = 0000 0001 two = 0000 0010 two = 1111 1111 0000 0000 0 t 1 t 2 t 1101 two = 1110 two = 1111 two = 0000 two = 0001 two = 0010 two = 2, 147, 483, 645 t 2, 147, 483, 646 t 2, 147, 483, 647 t – 2, 147, 483, 648 t – 2, 147, 483, 647 t – 2, 147, 483, 646 t 1111 1101 two = 1111 1110 two = 1111 two = – 3 t – 2 t – 1 t

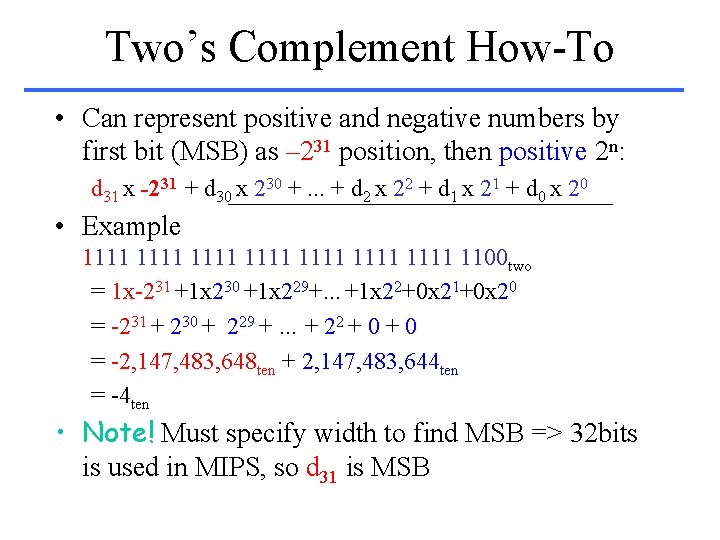

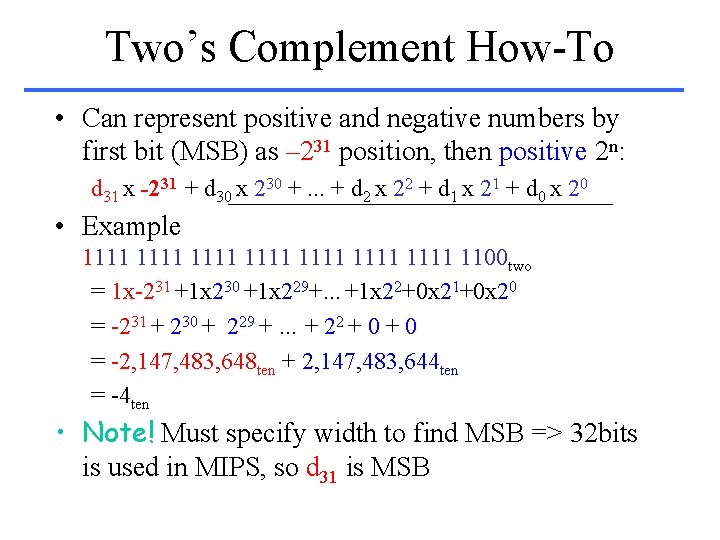

Two’s Complement How-To • Can represent positive and negative numbers by first bit (MSB) as – 231 position, then positive 2 n: d 31 x -231 + d 30 x 230 +. . . + d 2 x 22 + d 1 x 21 + d 0 x 20 • Example 1111 1111 1100 two = 1 x-231 +1 x 230 +1 x 229+. . . +1 x 22+0 x 21+0 x 20 = -231 + 230 + 229 +. . . + 22 + 0 = -2, 147, 483, 648 ten + 2, 147, 483, 644 ten = -4 ten • Note! Must specify width to find MSB => 32 bits is used in MIPS, so d 31 is MSB

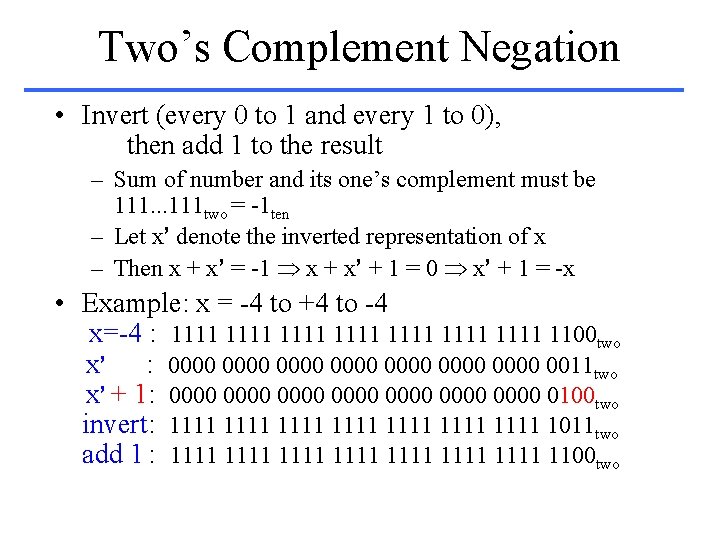

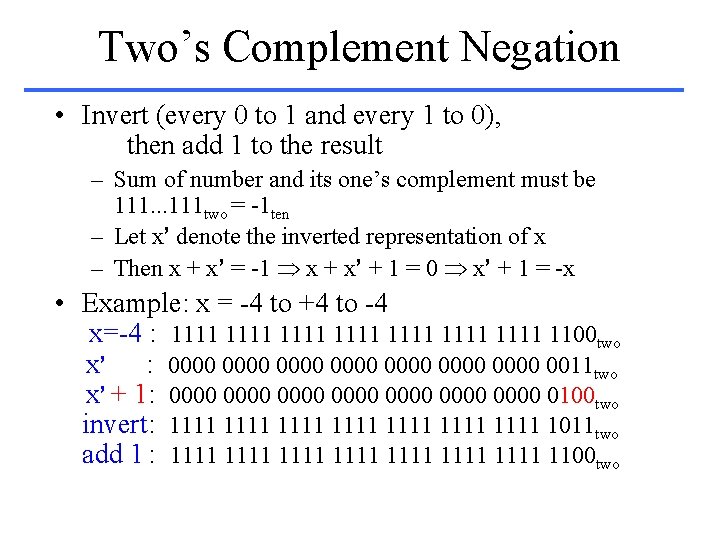

Two’s Complement Negation • Invert (every 0 to 1 and every 1 to 0), then add 1 to the result – Sum of number and its one’s complement must be 111. . . 111 two = -1 ten – Let x’ denote the inverted representation of x – Then x + x’ = -1 x + x’ + 1 = 0 x’ + 1 = -x • Example: x = -4 to +4 to -4 x=-4 : 1111 1111 1100 two x’ : 0000 0000 0011 two x’ + 1: 0000 0000 0100 two invert: 1111 1111 1011 two add 1 : 1111 1111 1100 two

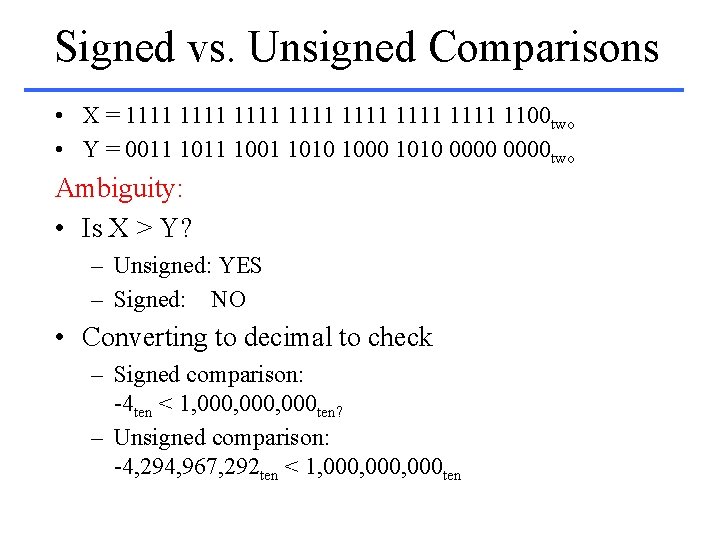

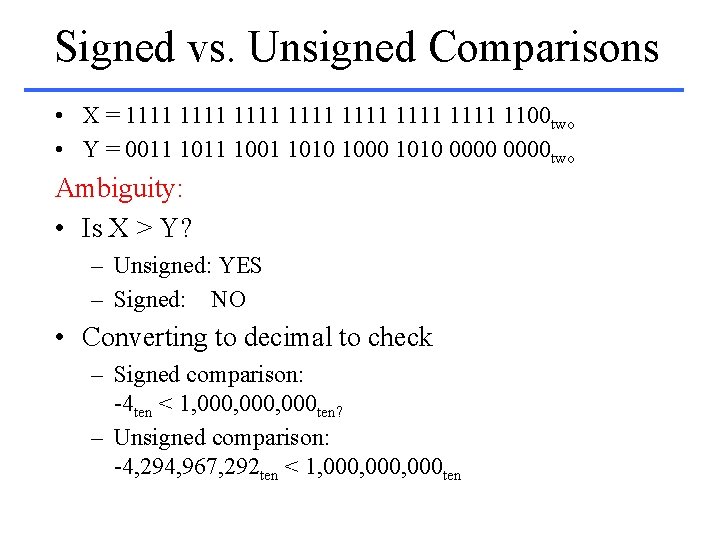

Signed vs. Unsigned Comparisons • X = 1111 1111 1100 two • Y = 0011 1001 1010 1000 1010 0000 two Ambiguity: • Is X > Y? – Unsigned: YES – Signed: NO • Converting to decimal to check – Signed comparison: -4 ten < 1, 000, 000 ten? – Unsigned comparison: -4, 294, 967, 292 ten < 1, 000, 000 ten

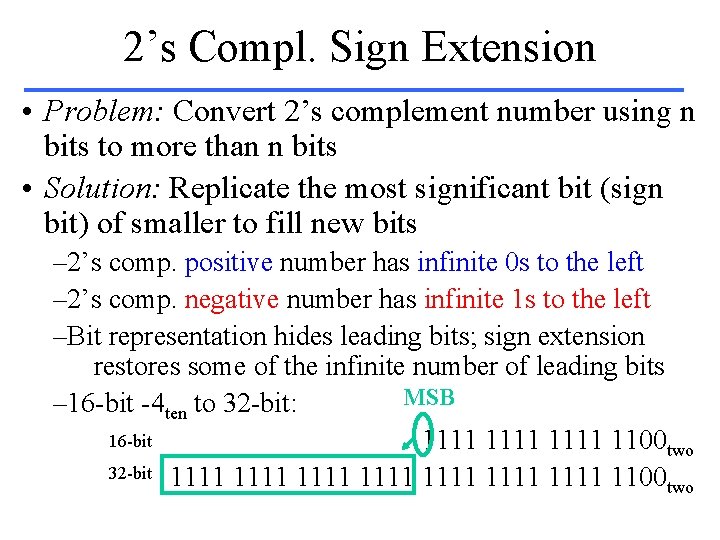

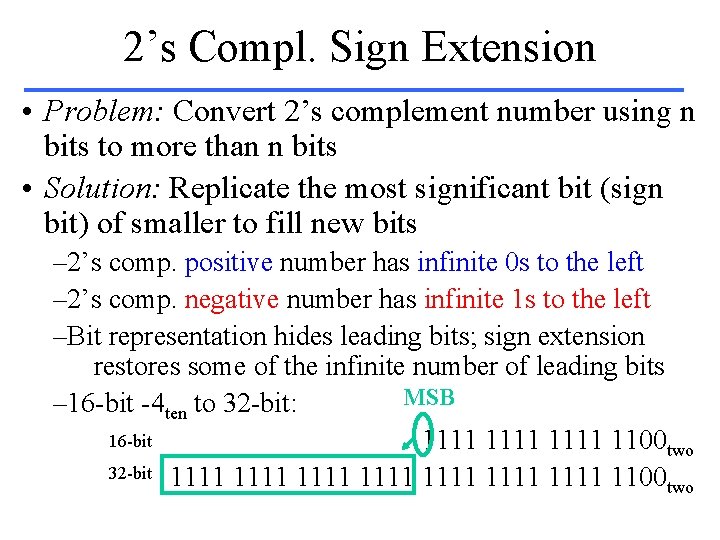

2’s Compl. Sign Extension • Problem: Convert 2’s complement number using n bits to more than n bits • Solution: Replicate the most significant bit (sign bit) of smaller to fill new bits – 2’s comp. positive number has infinite 0 s to the left – 2’s comp. negative number has infinite 1 s to the left –Bit representation hides leading bits; sign extension restores some of the infinite number of leading bits MSB – 16 -bit -4 ten to 32 -bit: 16 -bit 1111 1100 two 32 -bit 1111 1111 1100 two

Conclusion • We represent objects in computers as bit patterns: n bits =>2 n distinct patterns • Decimal for humans, binary for computers • 2’s complement universal in computing: cannot avoid, so we will learn • Computer operations on the representation are abstraction of real operations on the real thing • Overflow: - Numbers infinite - Computer finite • THINK: Weekend!