Case Studies I Definition case study as an

- Slides: 17

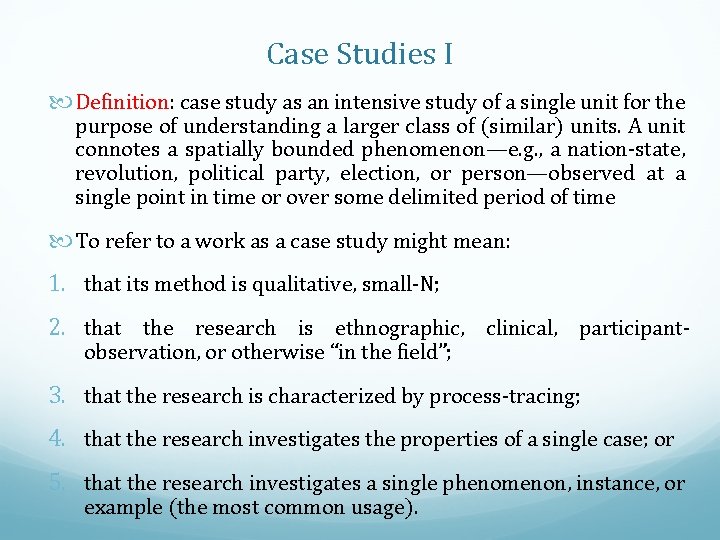

Case Studies I Definition: case study as an intensive study of a single unit for the purpose of understanding a larger class of (similar) units. A unit connotes a spatially bounded phenomenon—e. g. , a nation-state, revolution, political party, election, or person—observed at a single point in time or over some delimited period of time To refer to a work as a case study might mean: 1. that its method is qualitative, small-N; 2. that the research is ethnographic, clinical, participantobservation, or otherwise “in the field”; 3. that the research is characterized by process-tracing; 4. that the research investigates the properties of a single case; or 5. that the research investigates a single phenomenon, instance, or example (the most common usage).

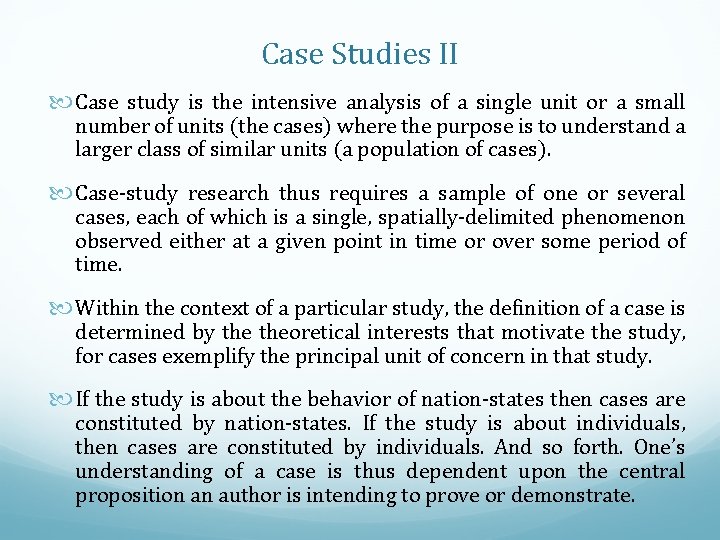

Case Studies II Case study is the intensive analysis of a single unit or a small number of units (the cases) where the purpose is to understand a larger class of similar units (a population of cases). Case-study research thus requires a sample of one or several cases, each of which is a single, spatially-delimited phenomenon observed either at a given point in time or over some period of time. Within the context of a particular study, the definition of a case is determined by theoretical interests that motivate the study, for cases exemplify the principal unit of concern in that study. If the study is about the behavior of nation-states then cases are constituted by nation-states. If the study is about individuals, then cases are constituted by individuals. And so forth. One’s understanding of a case is thus dependent upon the central proposition an author is intending to prove or demonstrate.

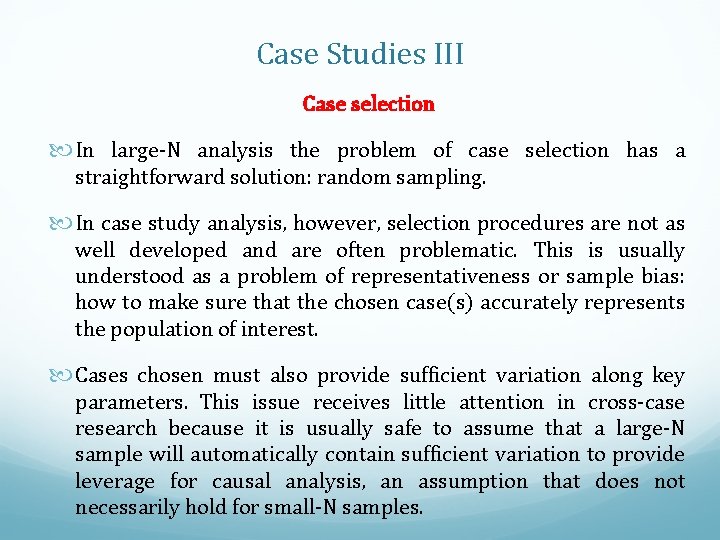

Case Studies III Case selection In large-N analysis the problem of case selection has a straightforward solution: random sampling. In case study analysis, however, selection procedures are not as well developed and are often problematic. This is usually understood as a problem of representativeness or sample bias: how to make sure that the chosen case(s) accurately represents the population of interest. Cases chosen must also provide sufficient variation along key parameters. This issue receives little attention in cross-case research because it is usually safe to assume that a large-N sample will automatically contain sufficient variation to provide leverage for causal analysis, an assumption that does not necessarily hold for small-N samples.

Case Studies IV Questions about case selection inevitably hinge upon the population of an inference. It is only by reference to this larger set of cases that one can begin to think about which cases might be most appropriate for indepth analysis. Thus, researchers must specify the set of cases which the research question or a specific proposition might apply to -- the breadth, domain, scope, or population (all are near-synonyms) of the case study. Case selection in case study research has the same twin objectives as random sampling. That is, one desires: 1. a representative sample 2. useful variation on the dimensions of theoretical interest.

Case Studies V Three important considerations for case studies: 1. pragmatic, logistical issues 2. theoretical prominence of a case in the literature on a topic 3. within-case characteristics of a case One’s choice of cases is therefore driven by the way a case is situated on such dimensions within the population of interest. It is from such cross-case characteristics that we derive the following seven case study types: typical, diverse, deviant, most-similar, and most-different.

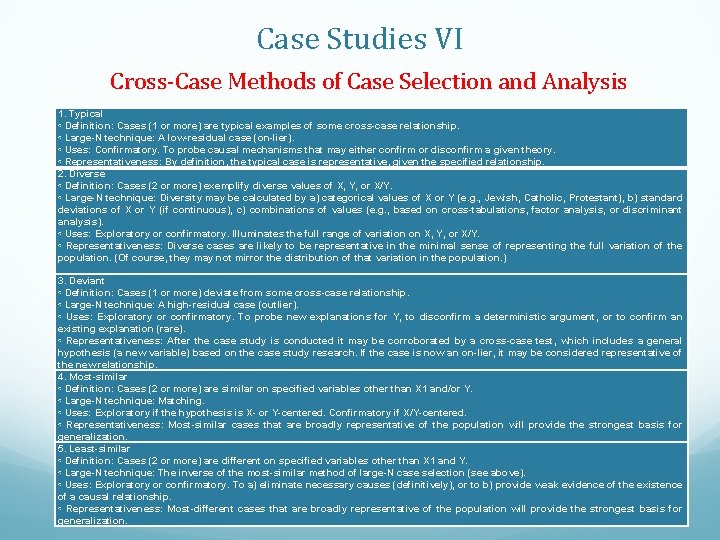

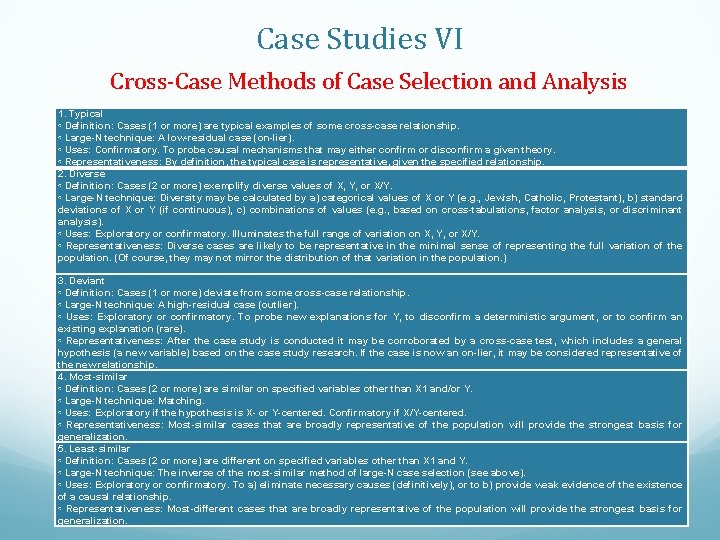

Case Studies VI Cross-Case Methods of Case Selection and Analysis 1. Typical ◦ Definition: Cases (1 or more) are typical examples of some cross-case relationship. ◦ Large-N technique: A low-residual case (on-lier). ◦ Uses: Confirmatory. To probe causal mechanisms that may either confirm or disconfirm a given theory. ◦ Representativeness: By definition, the typical case is representative, given the specified relationship. 2. Diverse ◦ Definition: Cases (2 or more) exemplify diverse values of X, Y, or X/Y. ◦ Large-N technique: Diversity may be calculated by a) categorical values of X or Y (e. g. , Jewish, Catholic, Protestant), b) standard deviations of X or Y (if continuous), c) combinations of values (e. g. , based on cross-tabulations, factor analysis, or discriminant analysis). ◦ Uses: Exploratory or confirmatory. Illuminates the full range of variation on X, Y, or X/Y. ◦ Representativeness: Diverse cases are likely to be representative in the minimal sense of representing the full variation of the population. (Of course, they may not mirror the distribution of that variation in the population. ) 3. Deviant ◦ Definition: Cases (1 or more) deviate from some cross-case relationship. ◦ Large-N technique: A high-residual case (outlier). ◦ Uses: Exploratory or confirmatory. To probe new explanations for Y, to disconfirm a deterministic argument, or to confirm an existing explanation (rare). ◦ Representativeness: After the case study is conducted it may be corroborated by a cross-case test, which includes a general hypothesis (a new variable) based on the case study research. If the case is now an on-lier, it may be considered representative of the new relationship. 4. Most-similar ◦ Definition: Cases (2 or more) are similar on specified variables other than X 1 and/or Y. ◦ Large-N technique: Matching. ◦ Uses: Exploratory if the hypothesis is X- or Y-centered. Confirmatory if X/Y-centered. ◦ Representativeness: Most-similar cases that are broadly representative of the population will provide the strongest basis for generalization. 5. Least-similar ◦ Definition: Cases (2 or more) are different on specified variables other than X 1 and Y. ◦ Large-N technique: The inverse of the most-similar method of large-N case selection (see above). ◦ Uses: Exploratory or confirmatory. To a) eliminate necessary causes (definitively), or to b) provide weak evidence of the existence of a causal relationship. ◦ Representativeness: Most-different cases that are broadly representative of the population will provide the strongest basis for generalization.

Case Studies VII Least-likely/Most-likely designs Most/least likely designs are based on the assumption that some cases are more important than others for the purposes of testing a theory. They are implicitly based on a Bayesian perspective in which the weight of the evidence is evaluated relative to prior theoretical expectations. A most-likely case is one that, on all dimensions except the dimension of theoretical interest, is predicted to achieve a certain outcome and yet does not. It is therefore disconfirmatory. A least-likely case is one that, on all dimensions except the dimension of theoretical interest, is predicted not to achieve a certain outcome and yet does so. It is confirmatory.

Case Studies VIII Least-likely - If one’s theoretical priors suggest that a particular case is unlikely to be consistent with a theory’s predictions—either because theory’s assumptions and scope conditions are not fully satisfied or because the values of many of theory’s key variables point in the other direction—and if the data supports theory, then the evidence from the case provides a great deal of leverage for increasing our confidence in the validity of theory. The inferential logic of least-likely case design is based on the “Sinatra inference”—if I can make it there I can make it anywhere. Mathew Evangelista 1999 book provides an excellent example of a tough test case in his book on transnational actors (TNAs) and U. S. Soviet defense and arms control policies in the cold war. Evangelista demonstrates that transnational contacts, particularly those between U. S. and Soviet scientists, did indeed affect the course of U. S. and Soviet defense and arms control policies. Evangelista’s has a least-likely approach to TNAs theory, by testing them against a hard realist case. Evangelista, M. (1999). Unarmed forces: The transnational movement to end the cold war. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Case Studies IX Most-likely - if one’s priors suggest that a case is likely to fit a theory, and if the data goes against our expectations, that result can be quite damaging to theory. The logic of most-likely case design is based on the inverse Sinatra inference - if I cannot make it there, I cannot make it anywhere. Andre Moravcsik 1999 paper asks if international bureaucrats have of international organizations decisively influence the outcomes of multilateral negotiations. Regime theorists, international legal scholars, negotiation analysts, and even constructivists assert that entrepreneurial leadership by high international officials is often necessary for successful international cooperation. Moravcsik tests these theories in the most-likely case where international bureaucrats should have influence – the European Community. Moravcsik challenges this interdisciplinary consensus on methodological, theoretical, and empirical grounds. He proposes an alternative theoretical view privileging the role of national governments and domestic politics—a view he tests by summarizing the results of a study of all major treaty-amending decisions in the forty years of EC history. Moravcsik, A. (1999). “A New Statecraft? Supranational Entrepreneurs and International Cooperation”, International Organization 53, 2, Spring 1999, pp. 267– 306.

Case Studies X Most-similar/Least-similar designs In a most-similar case comparison the key challenge is to find cases that are as similar as possible in all but one independent variable and that differ in their outcomes. Because it is never possible to find perfectly matched cases, which would require that the cases would be matched vis-à-vis both known and unknown rival hypotheses, the second challenge is to demonstrate that the difference in the value of the independent variable of interest between the two cases, rather than the residual differences between the two cases identified by rival hypotheses, accounts for the difference in outcomes. A key method for undertaking this latter task is to use process tracing to show that the independent variable of interest that differs between the cases does in fact affect their outcomes and to show that residual differences between the cases are not connected to the difference in outcomes by any plausible causal process. Feliciano Guimarães 2012 book. Guimarães, Feliciano. (2012). Os Burocratas das OI: um estudo comparado entre Banco Mundial e FMI. Rio de Janeiro: Editora da FGV.

Case Studies XI Most-similar/Least-similar designs In a least-similar cases design, the researcher selects cases that are dissimilar in all but one independent variable but that share the same dependent variable. This can provide evidence that the single common independent variable helps account for the common dependent variable. The task is to use process tracing to show that the common independent variable is related to the outcome through a plausible causal path and that other residual similarities between the cases are not. Carol Ember, Melvin Ember, and Bruce Russett (1992) tests whether the democratic peace finding, developed from research on modern states, applies as well to preindustrial societies. These authors conclude that despite the many differences between modern and preindustrial societies, preindustrial societies with participatory decision processes (IV) were also unlikely to fight one another (DV). Ember, C. L. , Ember, M. , & Russett, B. (1992). “Peace between participatory politics”. World Politics, 44, 573 -599.

Case Studies XI The typical case study focuses on a case that exemplifies a stable, cross-case relationship. By construction, the typical case may also be considered a representative case, according to the terms of whatever crosscase model is employed. Because the typical case is well-explained by an existing model, the puzzle of interest to the researcher lies within that case. Specifically, the researcher wants to find a typical case of some phenomenon so that better explore the causal mechanisms at work in a general, cross-case relationship. This exploration of causal mechanisms may lead toward several different conclusions.

Case Studies XIII Deviant cases are cases that do not conform to the predictions made by theory or theories under investigation. Put in Bayesian terms, deviant cases are those cases whose outcomes do not fit our prior theoretical expectations. Such cases can be identified as the cases in a statistical distribution that have high error terms vis-à-vis the model being tested or as cases in a small-N study that do not fit the expectations of extant theories or that have outcomes different from those of similar cases. In principle, cases identified as deviant in either setting could defy expectations for a number of reasons: They may be the result of measurement error, of the combined effects of many left -out variables that individually have small effects on outcomes, of one or a few left-out variables that strongly influence outcomes, or of irreducibly stochastic or probabilistic processes.

Case Studies XIV Deviant cases In practice, statistical researchers are often inclined toward a default assumption that outliers represent the effects of many weak variables or of stochastic processes, whereas case study researchers tend to assume that deviant cases result from measurement errors or small numbers of left-out variables that closer study might reveal. Although the study of deviant cases is potentially helpful, it may also lead to unfruitful theoretical amendments. If scholars respond to anomilies by simply relabeling them rather than providing an explanation for them, the new version of theory will not be a real improvement (Lakatos, 1970). The question is whether the new theory provided additional value, signaled by the prediction of novel facts.

Case Studies XV Diverse cases have as its primary objective the achievement of maximum variance along relevant dimensions. This method requires the selection of a set of cases – a minimum, two – which are intended to represent the full range of values characterizing X 1, Y, or some particular X 1/Y relationship. As previously, the investigation is understood to be exploratory when the researcher focuses on X or Y, and confirmatory when she focuses on a particular X 1/Y relationship (a specific hypothesis). Where the individual variable of interest is categorical (on/off, red/black/blue, Jewish/Protestant/Catholic), the identification of diversity is readily apparent. The investigator simply chooses one case from each category. For a continuous variable, the choices are not so obvious. However, the researcher usually chooses both extreme values (high and low), and perhaps the mean or median as well.

Case Studies XVI Combining Cross-Case and Over-Time Comparisons One research design that can generate considerable inferential leverage from the study of a few cases is the combination of cross-case and over-time (or before-after) case comparisons. This allows each case to be potentially compared in two different ways: The before of case “A” at “T 1” can be compared to the after of case “A” at “T 2”, whereas case “A” in one or both periods can also be compared to another case “B”, which might also be divided into two periods. Stephen Walt’s (1996) Revolution and War , for example, uses this research design to study why states that undergo a revolution often end up soon thereafter in a war with their neighbors. By studying the foreign policies of states both before and after they undergo revolutions, Walt is able to use what is essentially a most-similar cases design to examine how a revolution changes the foreign policy of a state. Within the same study, Walt is also able to compare across revolutionary states to assess why some ended up in interstate wars and others did not (France Russia, Iran, USA, Mexico, Turkey and Mexico). Walt, S. M. (1996). Revolution and war. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

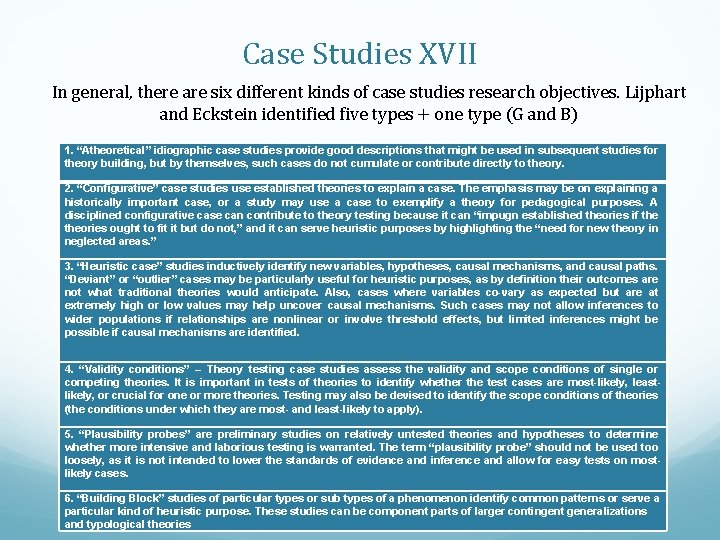

Case Studies XVII In general, there are six different kinds of case studies research objectives. Lijphart and Eckstein identified five types + one type (G and B) 1. “Atheoretical” idiographic case studies provide good descriptions that might be used in subsequent studies for theory building, but by themselves, such cases do not cumulate or contribute directly to theory. 2. “Configurative” case studies use established theories to explain a case. The emphasis may be on explaining a historically important case, or a study may use a case to exemplify a theory for pedagogical purposes. A disciplined configurative case can contribute to theory testing because it can “impugn established theories if theories ought to fit it but do not, ” and it can serve heuristic purposes by highlighting the “need for new theory in neglected areas. ” 3. “Heuristic case” studies inductively identify new variables, hypotheses, causal mechanisms, and causal paths. “Deviant” or “outlier” cases may be particularly useful for heuristic purposes, as by definition their outcomes are not what traditional theories would anticipate. Also, cases where variables co-vary as expected but are at extremely high or low values may help uncover causal mechanisms. Such cases may not allow inferences to wider populations if relationships are nonlinear or involve threshold effects, but limited inferences might be possible if causal mechanisms are identified. 4. “Validity conditions” – Theory testing case studies assess the validity and scope conditions of single or competing theories. It is important in tests of theories to identify whether the test cases are most-likely, leastlikely, or crucial for one or more theories. Testing may also be devised to identify the scope conditions of theories (the conditions under which they are most- and least-likely to apply). 5. “Plausibility probes” are preliminary studies on relatively untested theories and hypotheses to determine whether more intensive and laborious testing is warranted. The term “plausibility probe” should not be used too loosely, as it is not intended to lower the standards of evidence and inference and allow for easy tests on mostlikely cases. 6. “Building Block” studies of particular types or sub types of a phenomenon identify common patterns or serve a particular kind of heuristic purpose. These studies can be component parts of larger contingent generalizations and typological theories