Capacitance A water tower holds water A capacitor

![Example 2 (cont. ) Ccoax = L / [2 k ln(rcyl/rwire)]. Step 6: In Example 2 (cont. ) Ccoax = L / [2 k ln(rcyl/rwire)]. Step 6: In](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/f3ce866d46875b26121d77f85796a753/image-14.jpg)

![Formula for Series Using Cparallel plate = KA / [4 pkd] , we see Formula for Series Using Cparallel plate = KA / [4 pkd] , we see](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/f3ce866d46875b26121d77f85796a753/image-36.jpg)

- Slides: 56

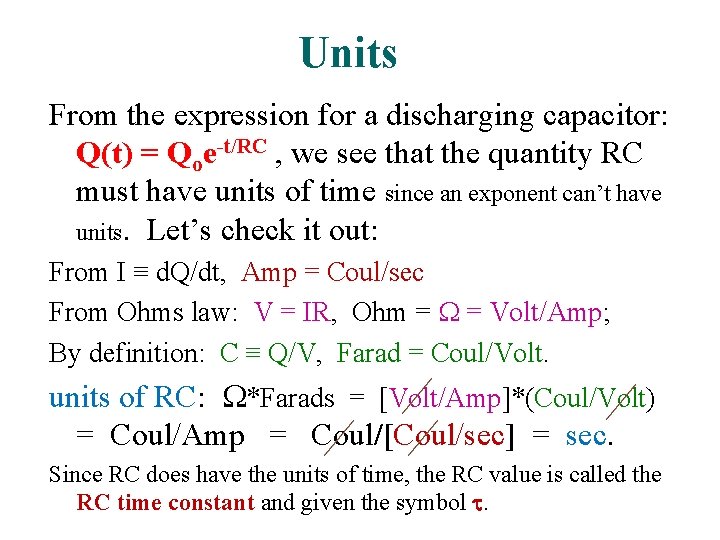

Capacitance A water tower holds water. A capacitor holds charge. The pressure at the base of the water tower depends on the height (and hence the amount) of the water. The voltage across a capacitor depends on the amount of charge held by the capacitor. Note: Capacitors are one of the basic circuit elements and are used in many circuits including AC-DC converters (like in your cell phone chargers) and in resonant circuits like we’ll see in Part 4 of the course. Warning: In the following be sure to distinguish between capacitance, capacitors, and capacity – they are all different.

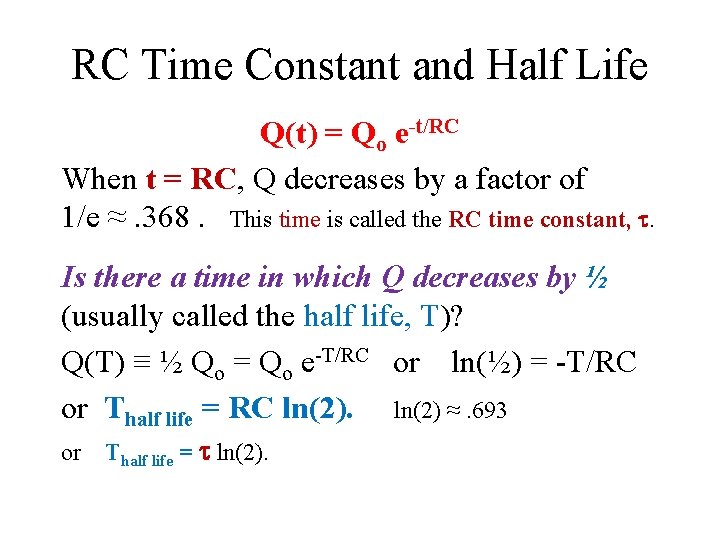

Capacitance We define capacitance as the amount of charge stored per volt: C ≡ Qstored / DV. UNITS: Farad = Coulomb / Volt [Note that capacitance is a little different than capacity. There is a maximum capacity for a capacitor that is related to the maximum voltage that can be applied across the capacitor. ] Just as the capacity of a water tower depends on the size and shape, so the capacitance of a capacitor depends on its size and shape. Just as a big water tower can contain more water per foot (or per unit pressure), so a big capacitor can store more charge per volt.

Parallel Plate Capacitor For a parallel plate capacitor, we can pull charge from one plate (leaving a -Q on that plate) and deposit it on the other plate (leaving a +Q on that plate). Because of the charge separation, we have a voltage difference between the plates, DV. The harder we pull (the more voltage across the two plates), the more charge we pull: C ≡ Q /DV. Note: C is NOT CHANGED by either Q or DV; instead, C RELATES Q and DV (i. e. , bigger voltage will cause a bigger Q, not change the C). This is like resistance where R does not depend on ΔV or I, it relates I to ΔV.

Parallel Plate Capacitor C ≡ Q/DV. For a parallel plate capacitor, the charge is related to the electric field, and the electric field is related to the voltage. We can then relate the charge to the voltage: E = 4πks where s = Q/A; and E = DV/d. This leads to: DV = Ed = 4πk. Qd/A. Thus C ≡ Q/DV becomes C = Q/DV = Q / (4πk. Qd/A) = C = A/(4πkd). Recall also that k = 1/[4 peo] so we could also write: C = eo. A/d.

Parallel Plate Capacitor For this parallel plate capacitor, the capacitance is related to charge and voltage (C ≡ Q/DV), but the actual capacitance depends on the size and shape: Cparallel plate = A / (4 p k d) where A is the area of each plate, d is the distance between the plates, and k is Coulomb’s constant (9 x 109 Nt-m 2 / Coul 2). This is similar to resistance: resistance relates voltage and current, but resistance depends on shape and material.

Parallel Plate Capacitor Cparallel plate = A / (4 p k d) The area, A, is in the numerator since a bigger area will store more charge for the same charge/area, σ, and so for the same E and the same V across the plates. The distance between the plates, d, is in the denominator because the closer the two plates are, the more the negative plate will tend to help by attracting the charge onto the positive plate. The Coulomb constant, k, is in the denominator since the stronger the repulsion between like charges, the harder it is to store charge, and so the lower the capacitance becomes. Of course, we can’t change k.

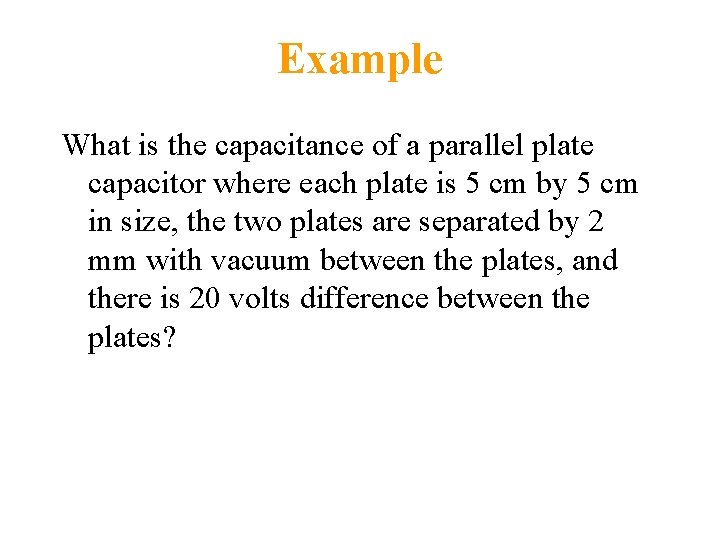

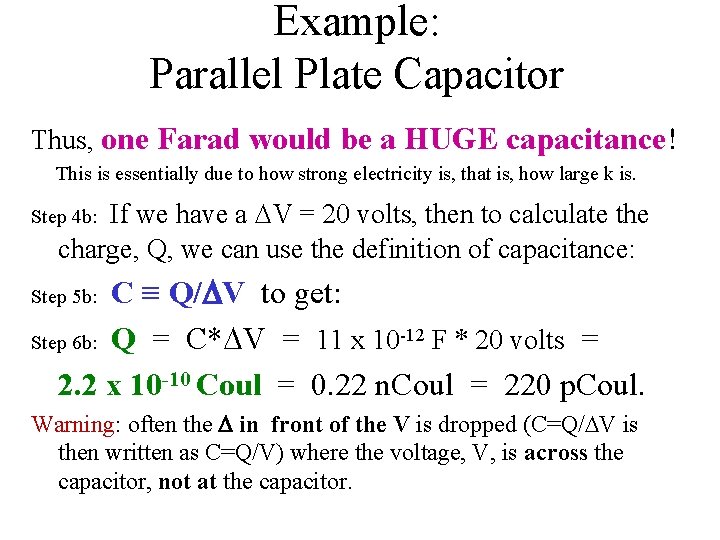

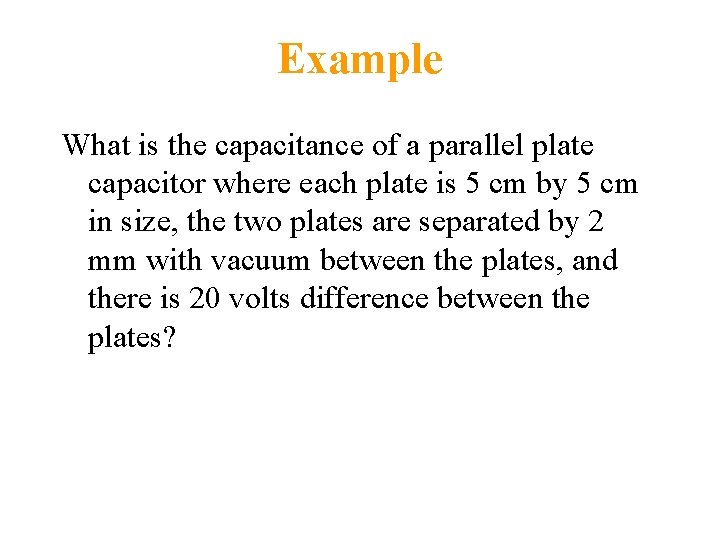

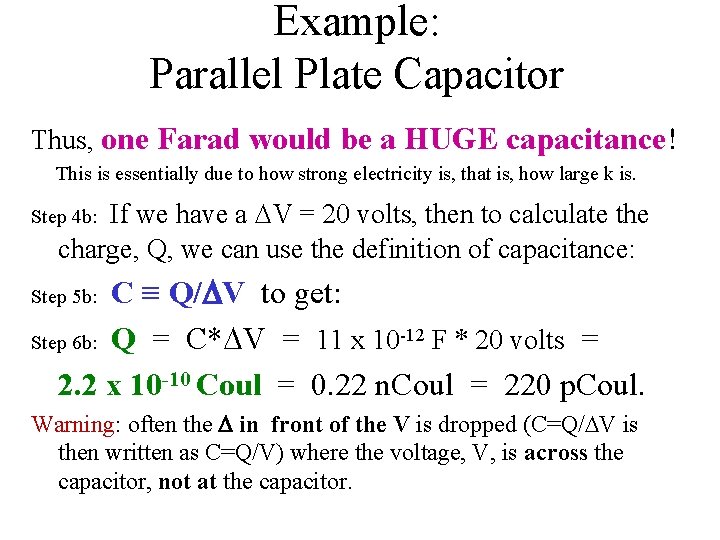

Example What is the capacitance of a parallel plate capacitor where each plate is 5 cm by 5 cm in size, the two plates are separated by 2 mm with vacuum between the plates, and there is 20 volts difference between the plates?

Example: Parallel Plate Capacitor Step 3 a: C = ? Step 3 b: Q = ? A = 5 cm x 5 cm = 25 cm 2 = 25 x 10 -4 m 2 ΔV = 20 V d = 2 mm = 2 x 10 -3 m, k = 9 x 109 Nt-m 2/Coul 2 Step 2: diagram A d ΔV Use formula for parallel plate capacitor. Step 5 a: The capacitance depends on A, k and d - but not ΔV: Cparallel plate = A / (4 p k d), so Step 6 a: C = (25 x 10 -4 m 2) / [4 * 3. 14 * 9 x 109 Nt-m 2/Coul 2 * 2 x 10 -3 m] = 1. 10 x 10 -11 F = 11 p. F. Step 4 a:

Example: Parallel Plate Capacitor Thus, one Farad would be a HUGE capacitance! This is essentially due to how strong electricity is, that is, how large k is. If we have a DV = 20 volts, then to calculate the charge, Q, we can use the definition of capacitance: Step 4 b: C ≡ Q/DV to get: Step 6 b: Q = C*DV = 11 x 10 -12 F * 20 volts = 2. 2 x 10 -10 Coul = 0. 22 n. Coul = 220 p. Coul. Step 5 b: Warning: often the D in front of the V is dropped (C=Q/DV is then written as C=Q/V) where the voltage, V, is across the capacitor, not at the capacitor.

Capacitance Recall that if we doubled the voltage across the plates, we would not do anything to the capacitance. Instead, we would double the charge stored on the capacitor. However, if we try to overfill the capacitor by placing too much voltage across it, the positive and negative plates will attract each other so strongly, that a spark will jump across the gap and destroy the capacitor. Thus capacitors have a maximum voltage across the plates [and hence a maximum charge or capacity].

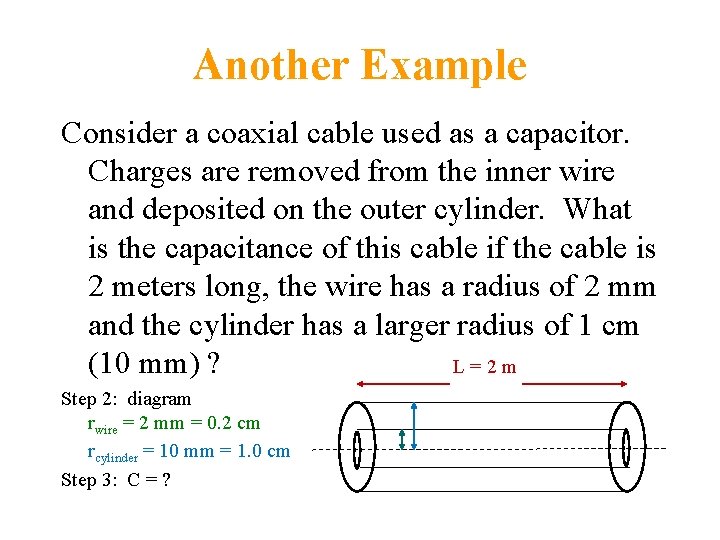

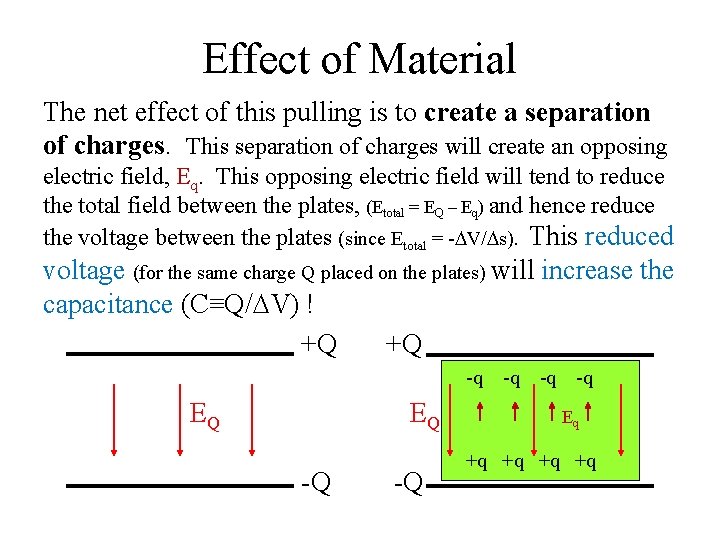

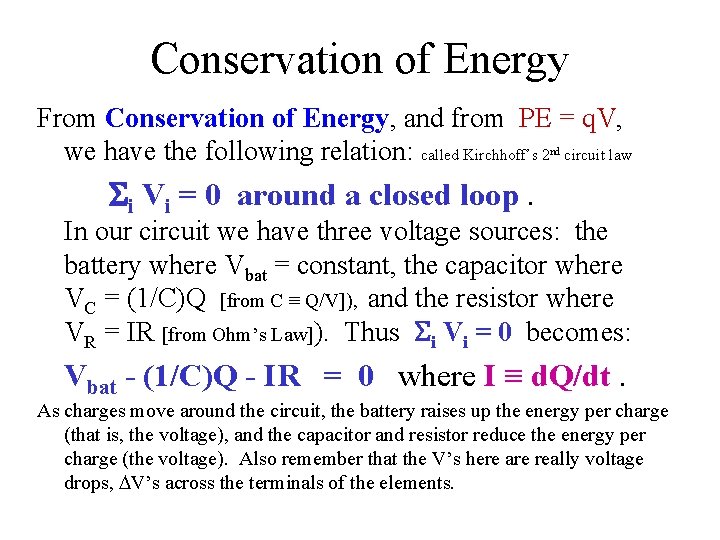

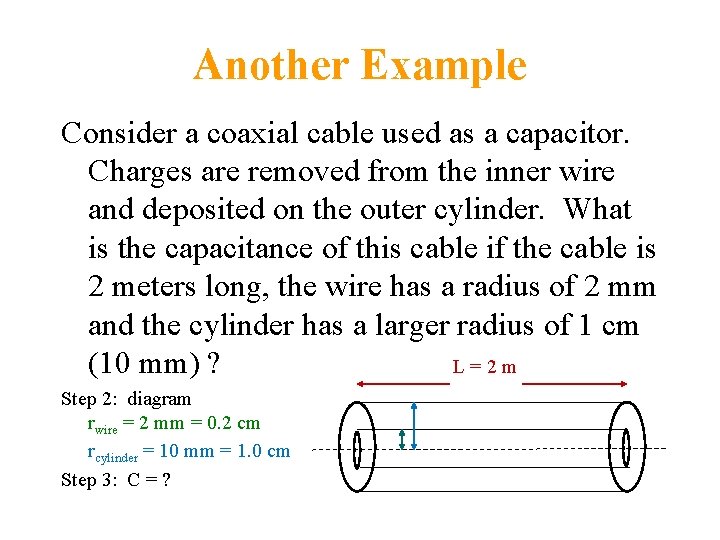

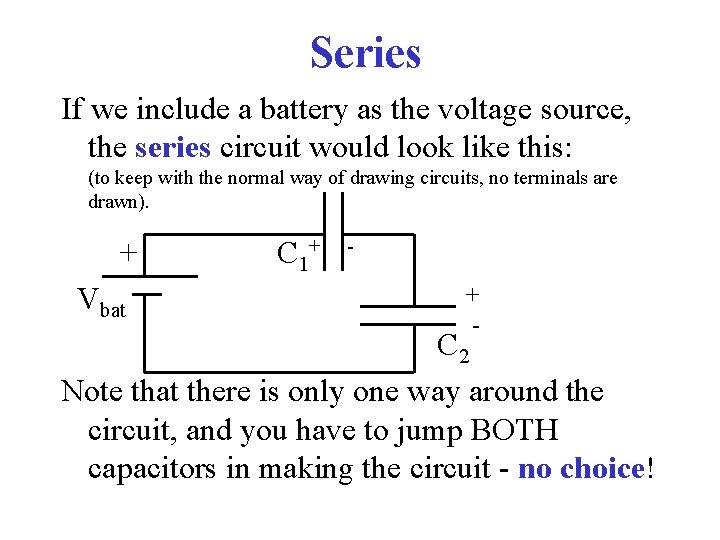

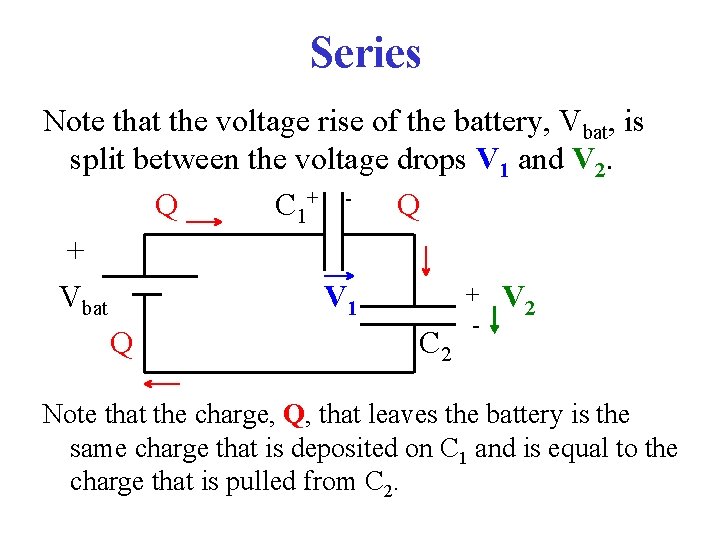

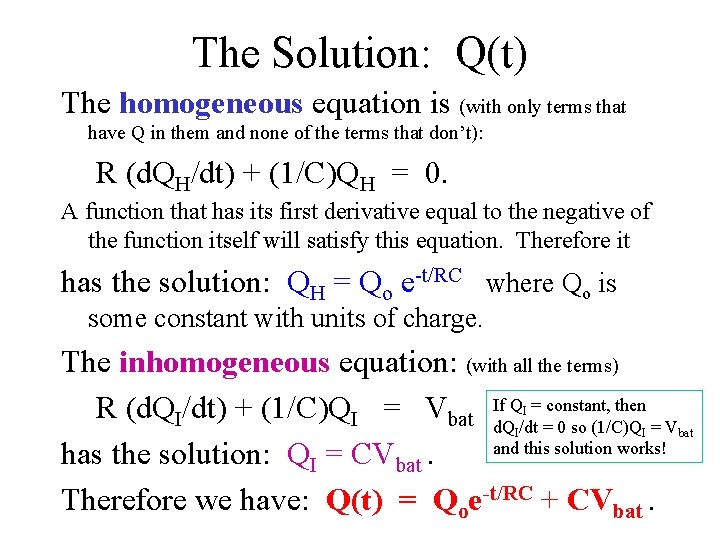

Another Example Consider a coaxial cable used as a capacitor. Charges are removed from the inner wire and deposited on the outer cylinder. What is the capacitance of this cable if the cable is 2 meters long, the wire has a radius of 2 mm and the cylinder has a larger radius of 1 cm (10 mm) ? L=2 m Step 2: diagram rwire = 2 mm = 0. 2 cm rcylinder = 10 mm = 1. 0 cm Step 3: C = ?

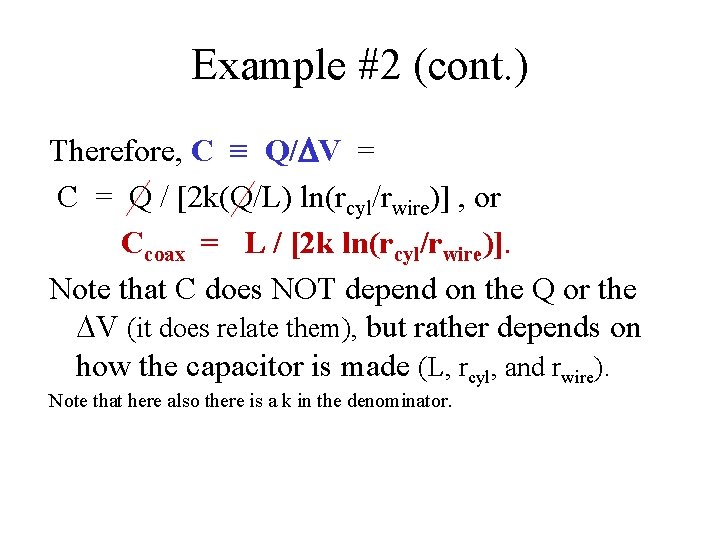

Example #2 (cont. ) Start with the definition of capacitance, and then relate the voltage to the charge that has been moved. Step 5: C ≡ Q/DV In the coaxial case, we know that the electric field between the wire and the cylinder is that due to the wire itself: E = 2 kl/r, where l=Q/L. From this we can get the voltage, DV = - E dr = - (2 kl/r)dr = 2 k(Q/L) ln(rcyl/rwire). Step 4: The sign on ΔV depends on whether the wire has the positive or negative charge.

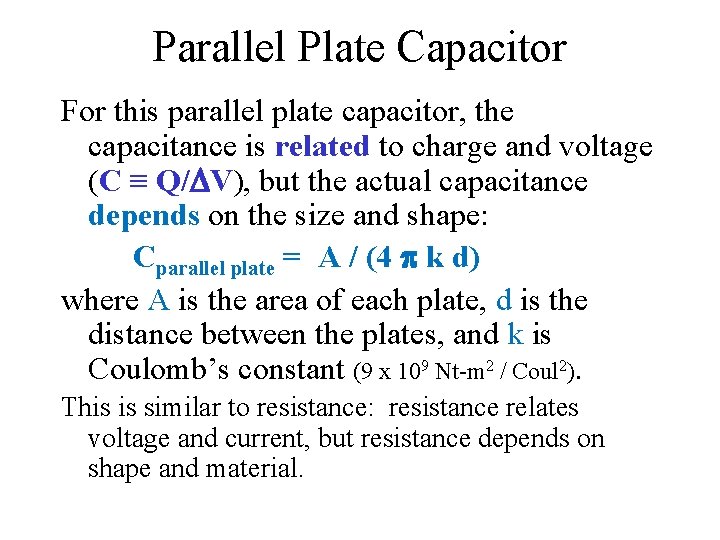

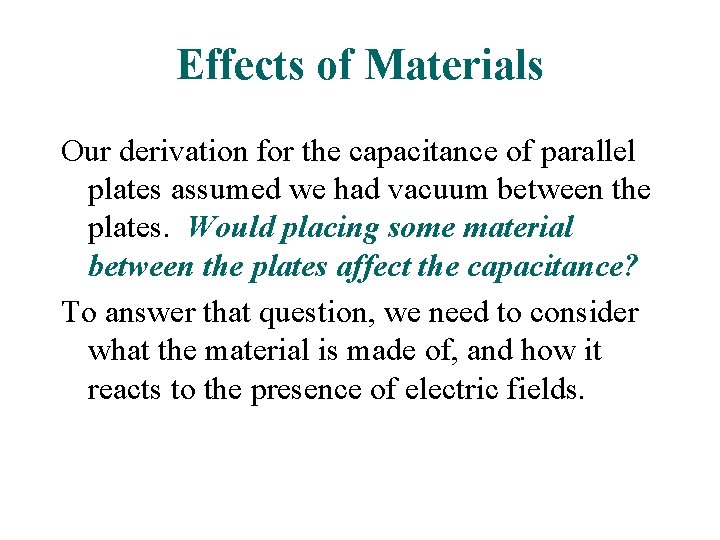

Example #2 (cont. ) Therefore, C ≡ Q/DV = C = Q / [2 k(Q/L) ln(rcyl/rwire)] , or Ccoax = L / [2 k ln(rcyl/rwire)]. Note that C does NOT depend on the Q or the DV (it does relate them), but rather depends on how the capacitor is made (L, rcyl, and rwire). Note that here also there is a k in the denominator.

![Example 2 cont Ccoax L 2 k lnrcylrwire Step 6 In Example 2 (cont. ) Ccoax = L / [2 k ln(rcyl/rwire)]. Step 6: In](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/f3ce866d46875b26121d77f85796a753/image-14.jpg)

Example 2 (cont. ) Ccoax = L / [2 k ln(rcyl/rwire)]. Step 6: In this case, we are given: L = 2 meters; rcyl = 1 cm = 10 mm; rwire = 2 mm. Thus, C = 2 m / [2 x 9 x 109 Nt-m 2/Coul 2 x ln(10 mm / 2 mm)] = 6. 9 x 10 -11 Coul 2/Nt-m UNITS: Nt-m = Joule, and a Joule/Coul = Volt, so units are Coul/Volt = Farad. C = 69 p. F.

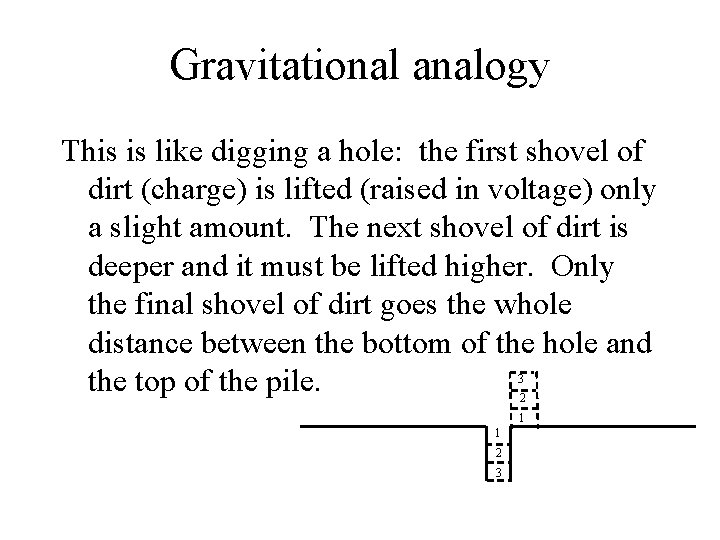

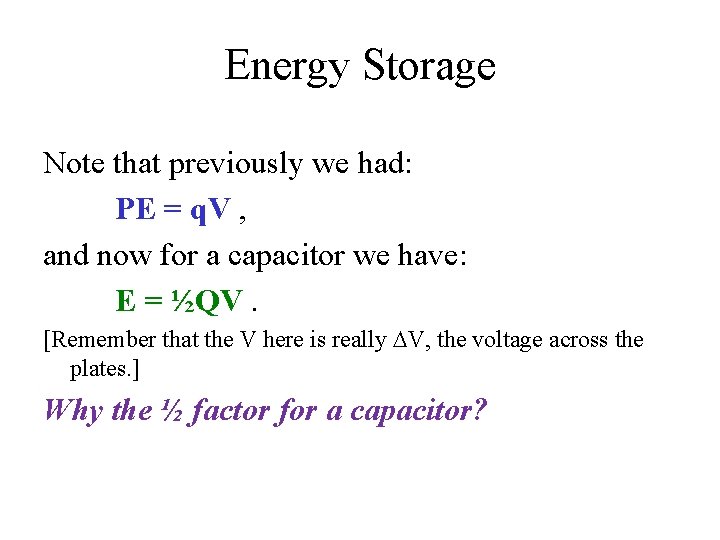

Energy Storage If a capacitor stores charge and carries voltage, it also stores the energy it took to separate the charge. Note that we move the charge piece by piece from one plate to the next, and as each charge is moved, the voltage across the plates increases. Note that the whole charge is not moved across the whole voltage!

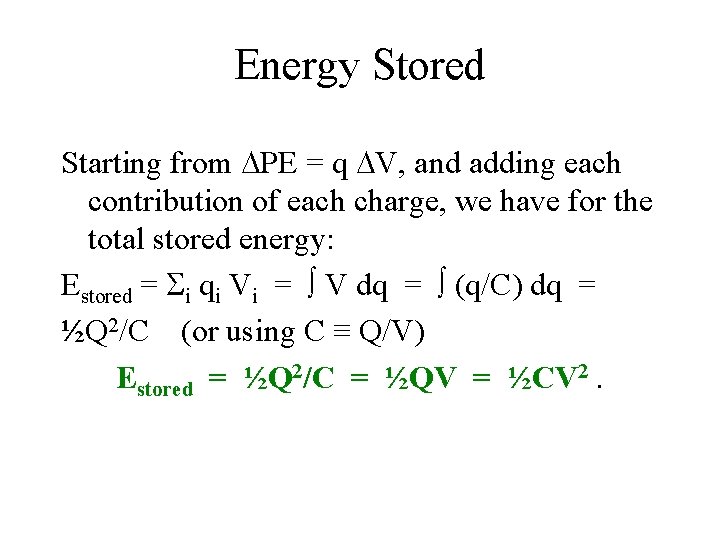

Gravitational analogy This is like digging a hole: the first shovel of dirt (charge) is lifted (raised in voltage) only a slight amount. The next shovel of dirt is deeper and it must be lifted higher. Only the final shovel of dirt goes the whole distance between the bottom of the hole and the top of the pile. 3 2 1 1 2 3

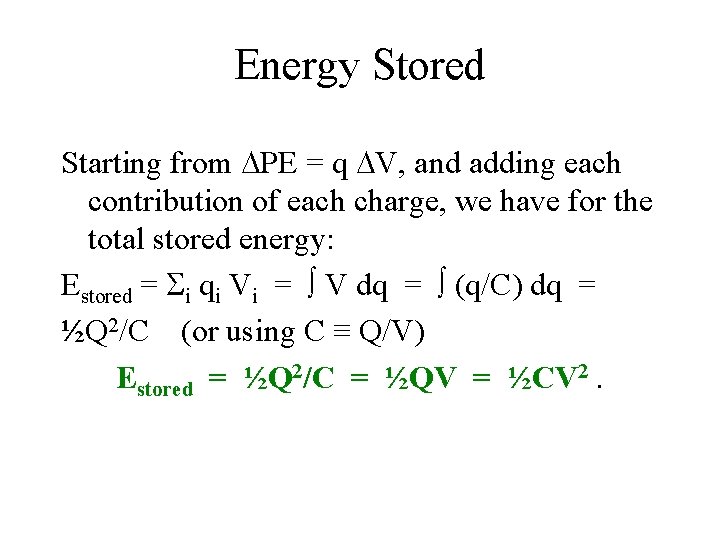

Energy Stored Starting from DPE = q DV, and adding each contribution of each charge, we have for the total stored energy: Estored = Si qi Vi = V dq = (q/C) dq = ½Q 2/C (or using C ≡ Q/V) Estored = ½Q 2/C = ½QV = ½CV 2.

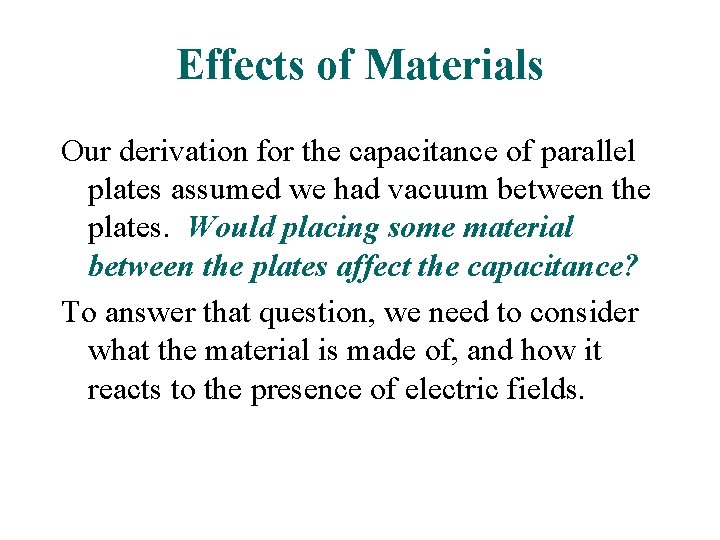

Energy Storage Note that previously we had: PE = q. V , and now for a capacitor we have: E = ½QV. [Remember that the V here is really DV, the voltage across the plates. ] Why the ½ factor for a capacitor?

Energy Storage The reason is that in charging a capacitor, the first bit of charge is transferred while there is very little voltage on (really across) the capacitor (recall that the charge separation creates the voltage!). Only the last bit of charge is moved across the full voltage. Thus, on average, the full charge moves across only half the voltage! See the slide previously about the gravitational analogy. But the battery moves the full charge with the full voltage, so where does that other half of the PE go? It goes into heat in the resistance in the circuit while charging the plates!

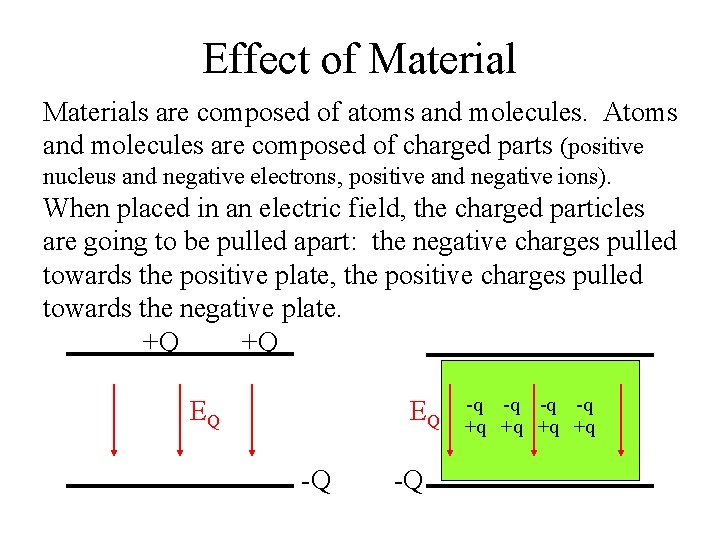

Effects of Materials Our derivation for the capacitance of parallel plates assumed we had vacuum between the plates. Would placing some material between the plates affect the capacitance? To answer that question, we need to consider what the material is made of, and how it reacts to the presence of electric fields.

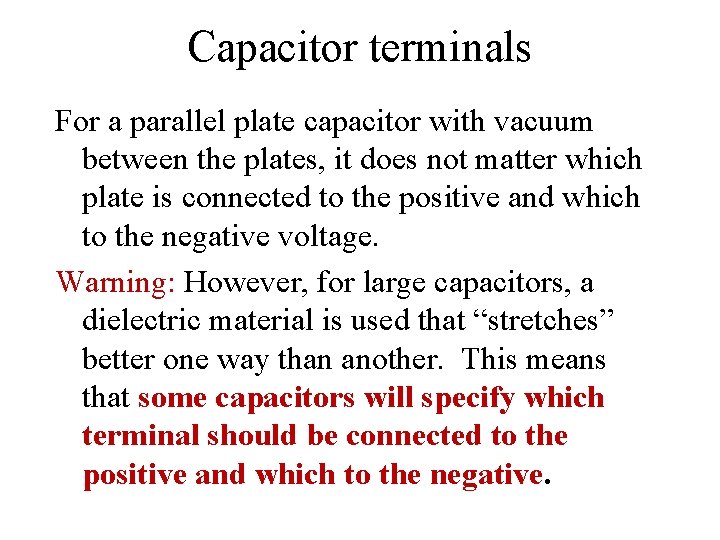

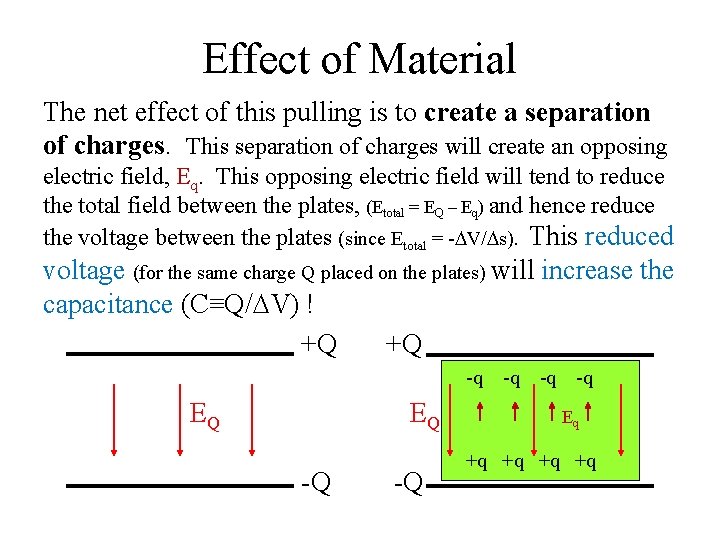

Effect of Materials are composed of atoms and molecules. Atoms and molecules are composed of charged parts (positive nucleus and negative electrons, positive and negative ions). When placed in an electric field, the charged particles are going to be pulled apart: the negative charges pulled towards the positive plate, the positive charges pulled towards the negative plate. +Q +Q EQ EQ -Q -Q -q -q +q +q

Effect of Material The net effect of this pulling is to create a separation of charges. This separation of charges will create an opposing electric field, Eq. This opposing electric field will tend to reduce the total field between the plates, (Etotal = EQ – Eq) and hence reduce the voltage between the plates (since Etotal = -DV/Ds). This reduced voltage (for the same charge Q placed on the plates) will increase the capacitance (C≡Q/DV) ! +Q +Q -q -q EQ EQ -Q -Q -q -q Eq +q +q

Dielectric Constant Some materials are more “electrically stretchable” than others, and so some will cause the capacitance to increase more than others. Vacuum can not stretch (no charges to stretch!), so it will provide the smallest possible capacitance. To describe this “electrical stretchiness”, we define a dielectric constant, K, such that Kof material ≡ Cwith material / Cwith vacuum , or Cwith material = Kof material * Cwith vacuum. (Be sure to distinguish between k and K!) Note that the units for the dielectric constant, K, are none!

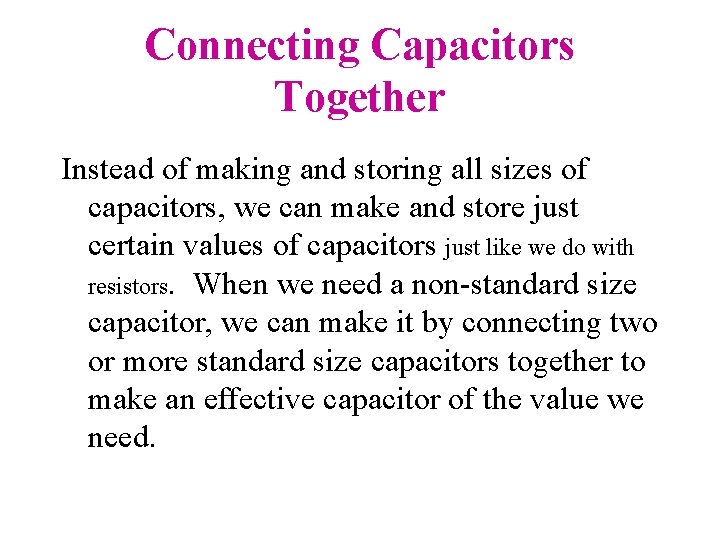

Capacitor terminals For a parallel plate capacitor with vacuum between the plates, it does not matter which plate is connected to the positive and which to the negative voltage. Warning: However, for large capacitors, a dielectric material is used that “stretches” better one way than another. This means that some capacitors will specify which terminal should be connected to the positive and which to the negative.

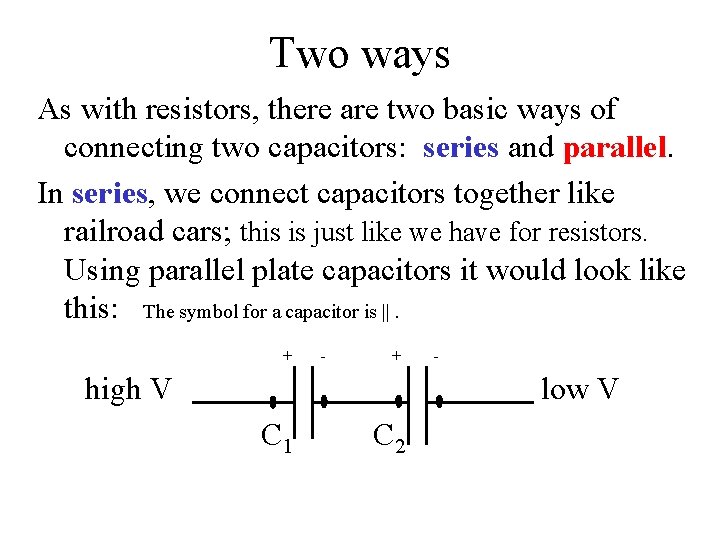

Capacitance and Max DV If we apply too much voltage across the plates, the charges will stretch to the point of breaking – which produces lightning in the capacitor which will destroy the capacitor. Hence capacitors will have a maximum voltage listed in their properties along with their capacitance. This max voltage along with the capacitance will give you the capacity of the capacitor to store charge: Qmax = C*Vmax.

Connecting Capacitors Together Instead of making and storing all sizes of capacitors, we can make and store just certain values of capacitors just like we do with resistors. When we need a non-standard size capacitor, we can make it by connecting two or more standard size capacitors together to make an effective capacitor of the value we need.

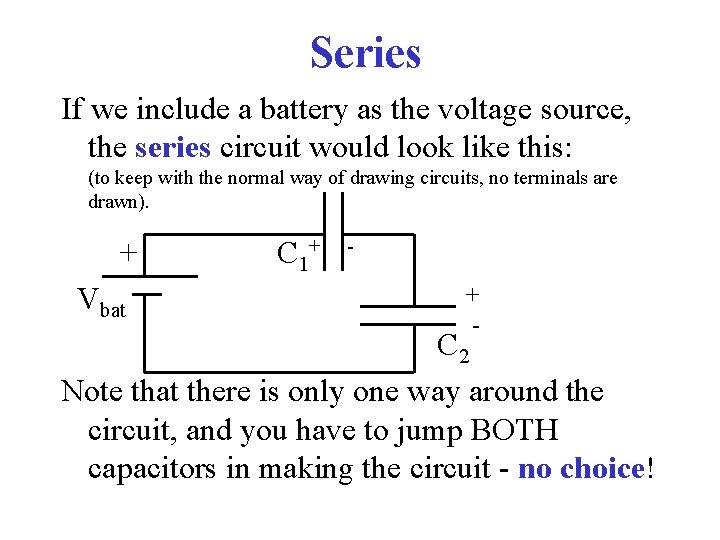

Two ways As with resistors, there are two basic ways of connecting two capacitors: series and parallel. In series, we connect capacitors together like railroad cars; this is just like we have for resistors. Using parallel plate capacitors it would look like this: The symbol for a capacitor is ||. + - + high V - low V C 1 C 2

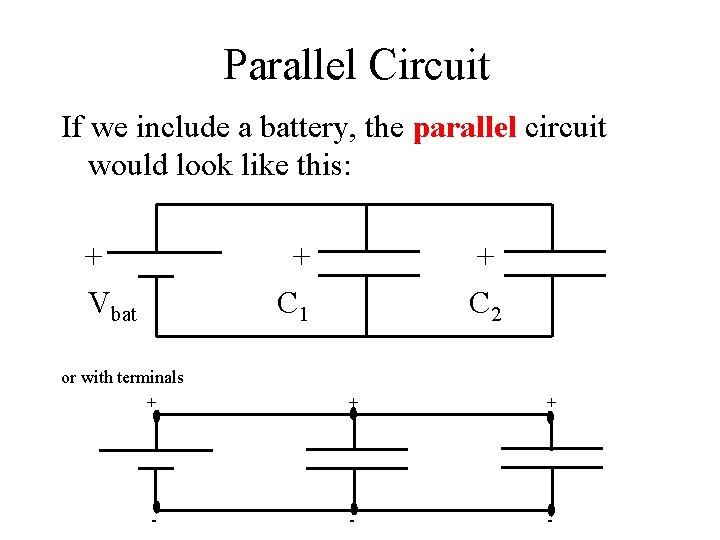

Series If we include a battery as the voltage source, the series circuit would look like this: (to keep with the normal way of drawing circuits, no terminals are drawn). + Vbat C 1+ - C 2 Note that there is only one way around the circuit, and you have to jump BOTH capacitors in making the circuit - no choice!

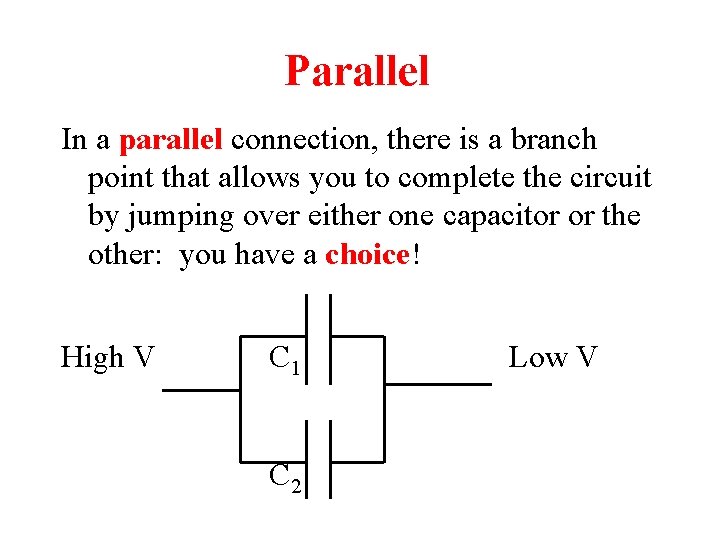

Parallel In a parallel connection, there is a branch point that allows you to complete the circuit by jumping over either one capacitor or the other: you have a choice! High V C 1 C 2 Low V

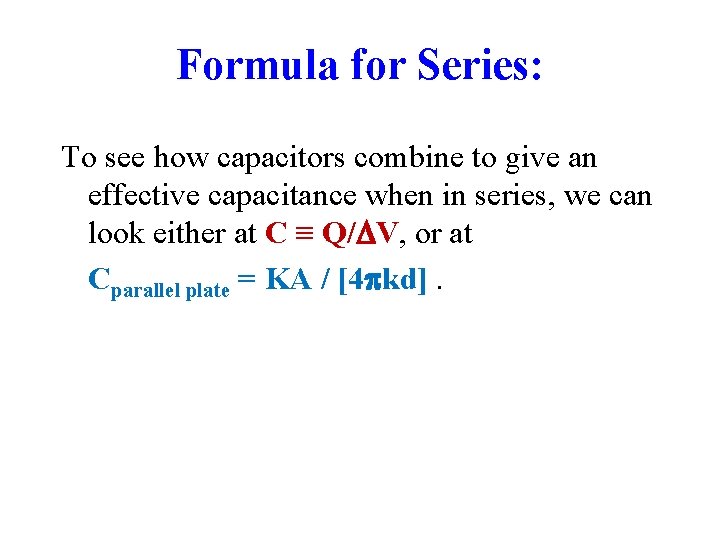

Parallel Circuit If we include a battery, the parallel circuit would look like this: + Vbat + C 1 or with terminals + - + C 2 + + - -

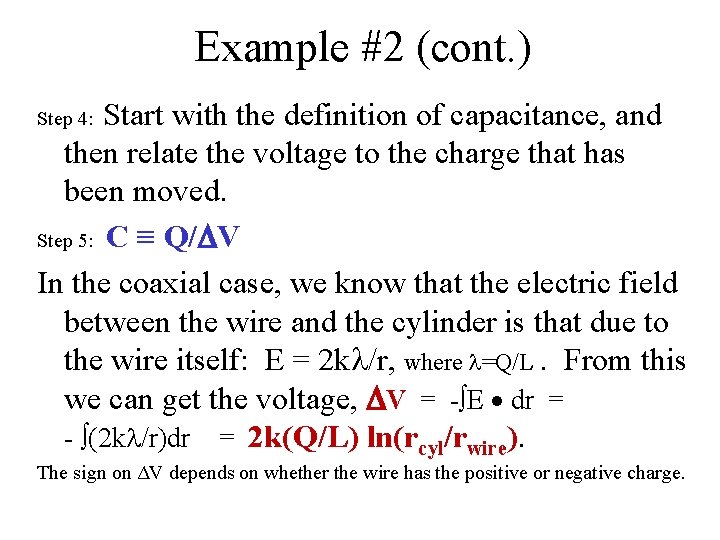

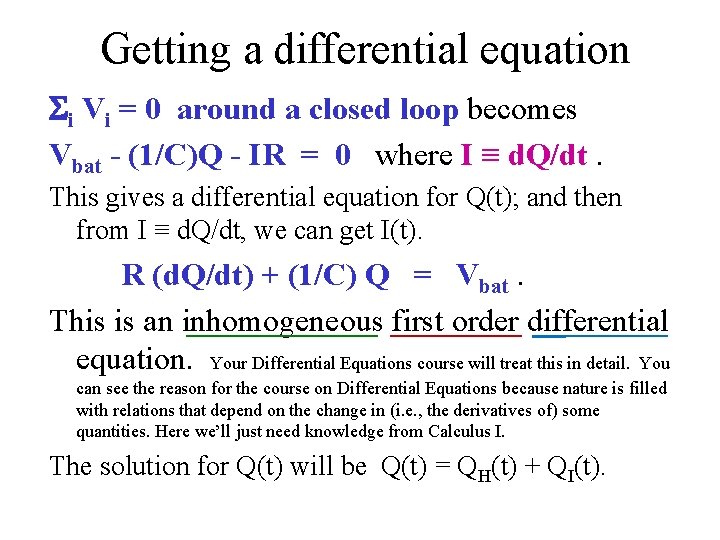

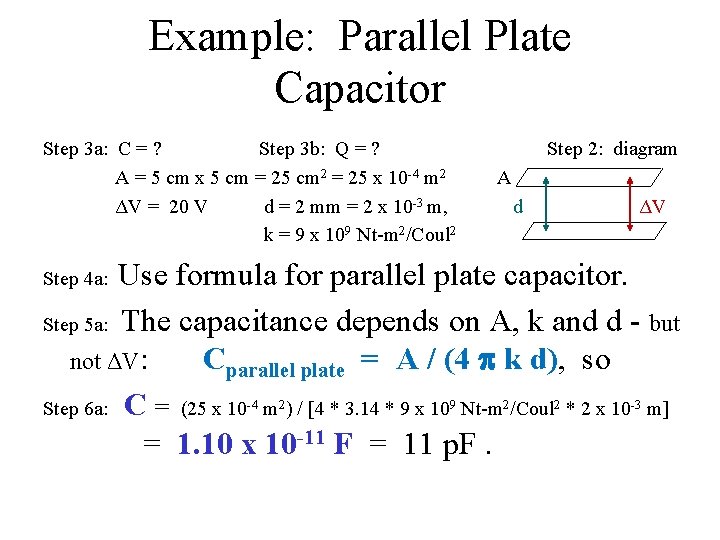

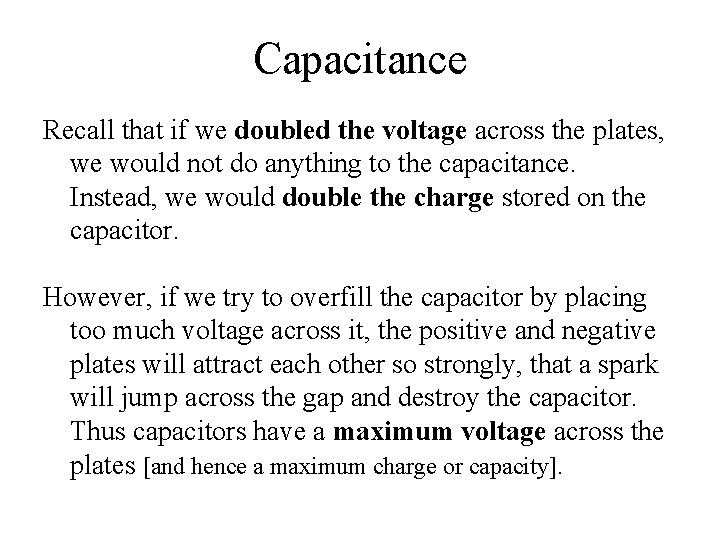

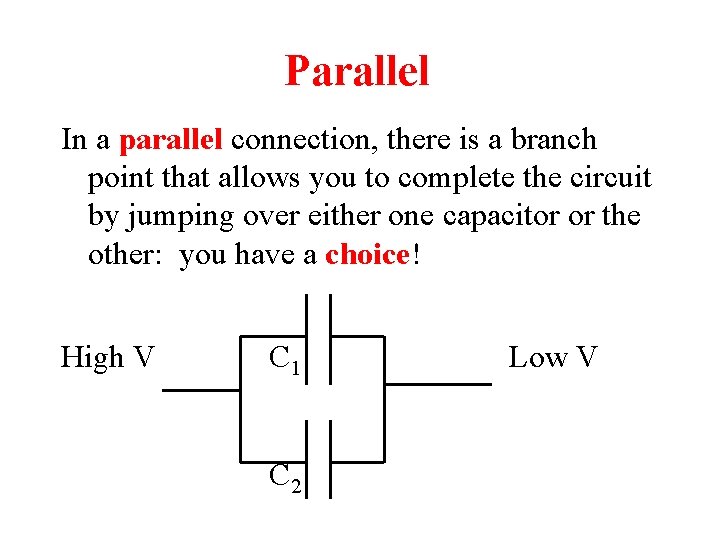

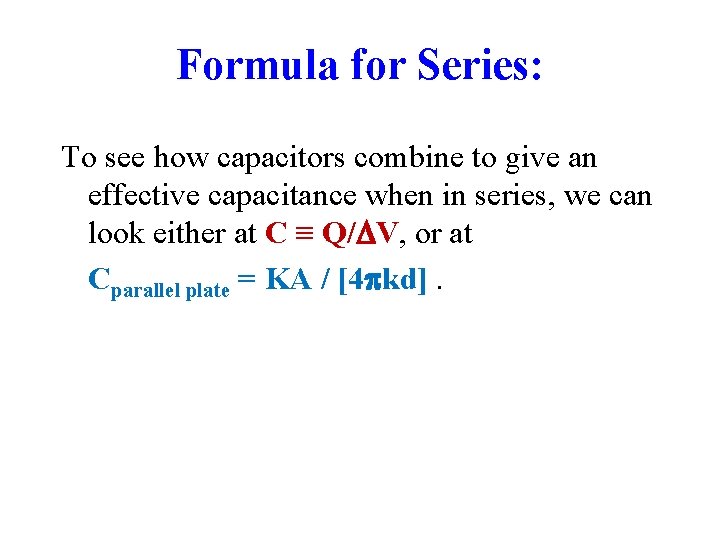

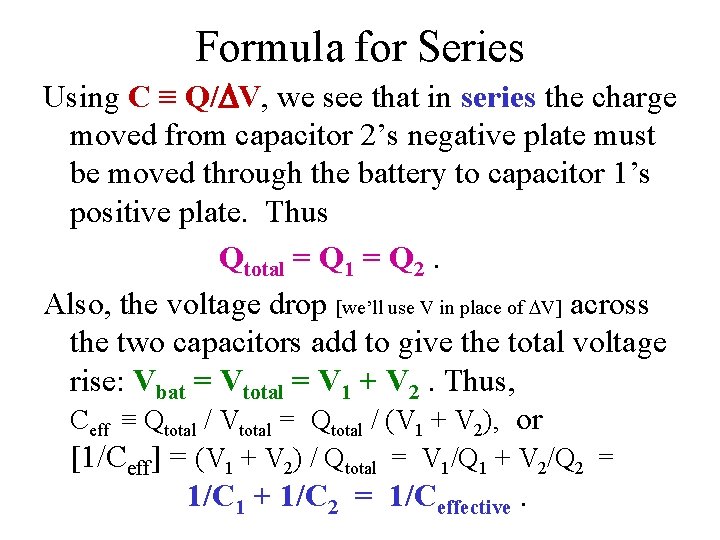

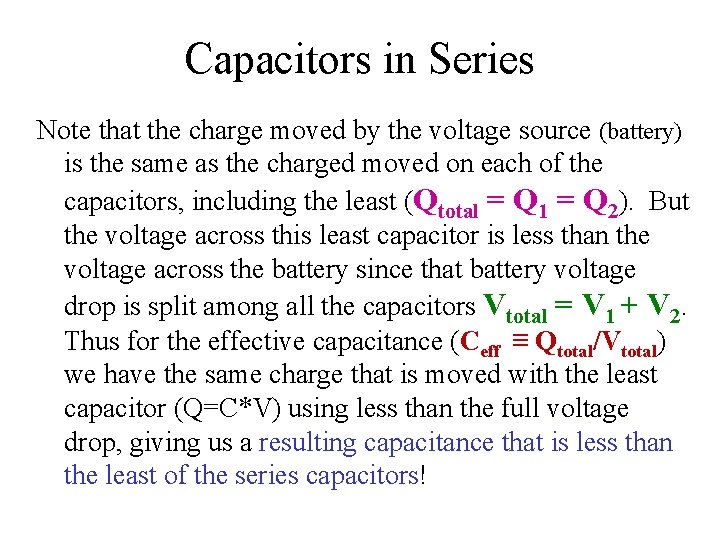

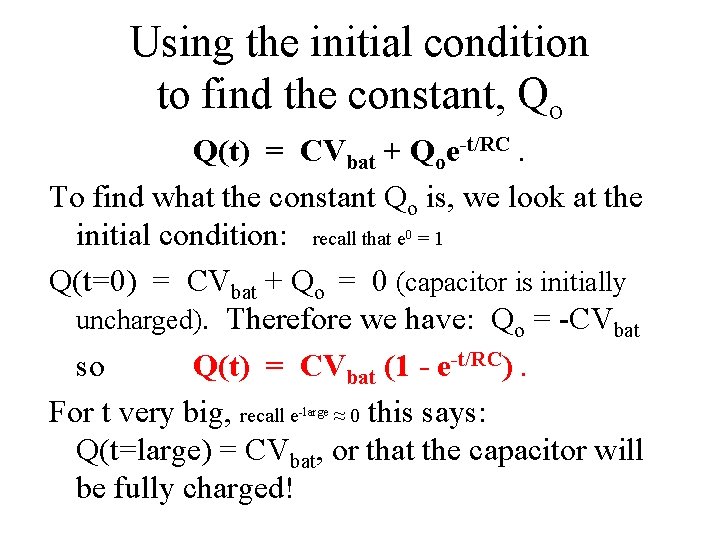

Formula for Series: To see how capacitors combine to give an effective capacitance when in series, we can look either at C ≡ Q/DV, or at Cparallel plate = KA / [4 pkd].

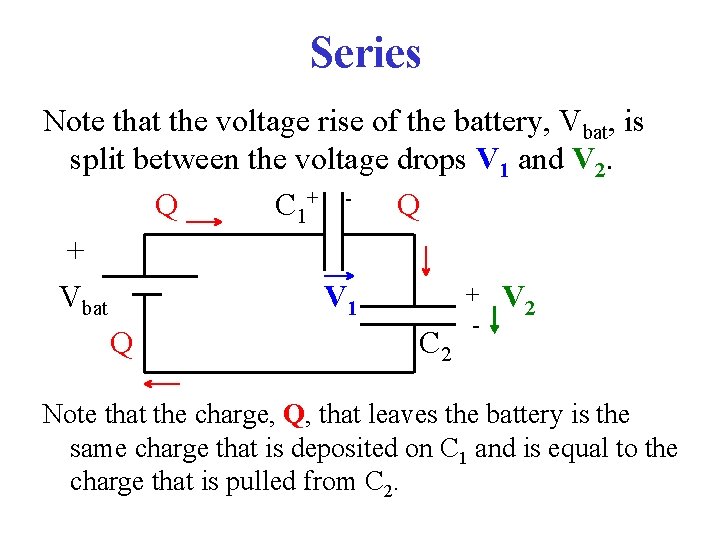

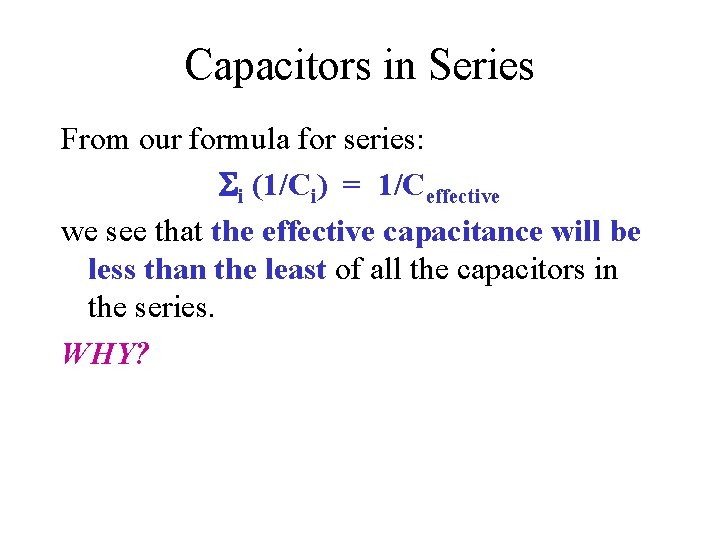

Series Note that the voltage rise of the battery, Vbat, is split between the voltage drops V 1 and V 2. Q C 1+ - Q + + V Vbat V 1 2 Q C 2 Note that the charge, Q, that leaves the battery is the same charge that is deposited on C 1 and is equal to the charge that is pulled from C 2.

Formula for Series Using C ≡ Q/DV, we see that in series the charge moved from capacitor 2’s negative plate must be moved through the battery to capacitor 1’s positive plate. Thus Qtotal = Q 1 = Q 2. Also, the voltage drop [we’ll use V in place of DV] across the two capacitors add to give the total voltage rise: Vbat = Vtotal = V 1 + V 2. Thus, Ceff ≡ Qtotal / Vtotal = Qtotal / (V 1 + V 2), or [1/Ceff] = (V 1 + V 2) / Qtotal = V 1/Q 1 + V 2/Q 2 = 1/C 1 + 1/C 2 = 1/Ceffective.

Capacitors in Series From our formula for series: i (1/Ci) = 1/Ceffective we see that the effective capacitance will be less than the least of all the capacitors in the series. WHY?

Capacitors in Series Note that the charge moved by the voltage source (battery) is the same as the charged moved on each of the capacitors, including the least (Qtotal = Q 1 = Q 2). But the voltage across this least capacitor is less than the voltage across the battery since that battery voltage drop is split among all the capacitors Vtotal = V 1 + V 2. Thus for the effective capacitance (Ceff ≡ Qtotal/Vtotal) we have the same charge that is moved with the least capacitor (Q=C*V) using less than the full voltage drop, giving us a resulting capacitance that is less than the least of the series capacitors!

![Formula for Series Using Cparallel plate KA 4 pkd we see Formula for Series Using Cparallel plate = KA / [4 pkd] , we see](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/f3ce866d46875b26121d77f85796a753/image-36.jpg)

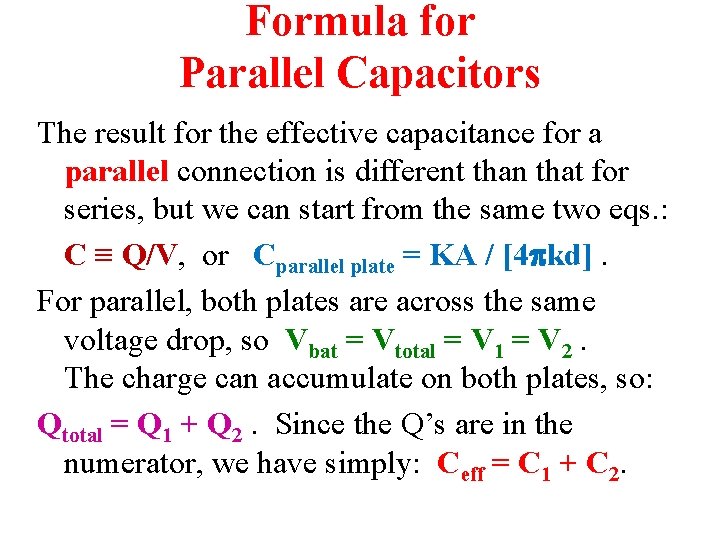

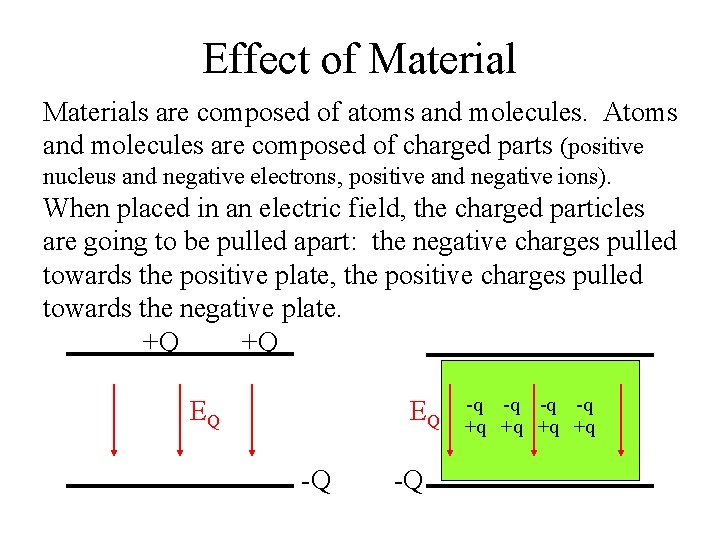

Formula for Series Using Cparallel plate = KA / [4 pkd] , we see that we have to go over both distances, so the distances should add. But the distances are in the denominator, and so the inverses should add. This is just like in C ≡ Q/V where the V’s add and are in the denominator! Note: this is the opposite to that of resistors when connected in series!

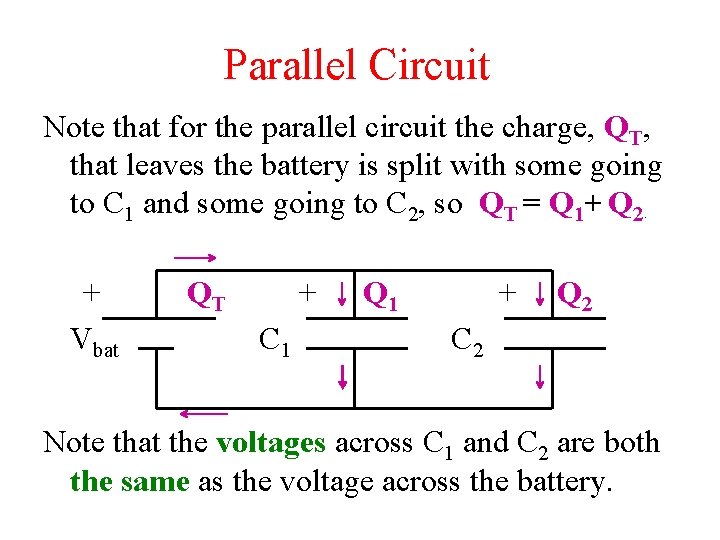

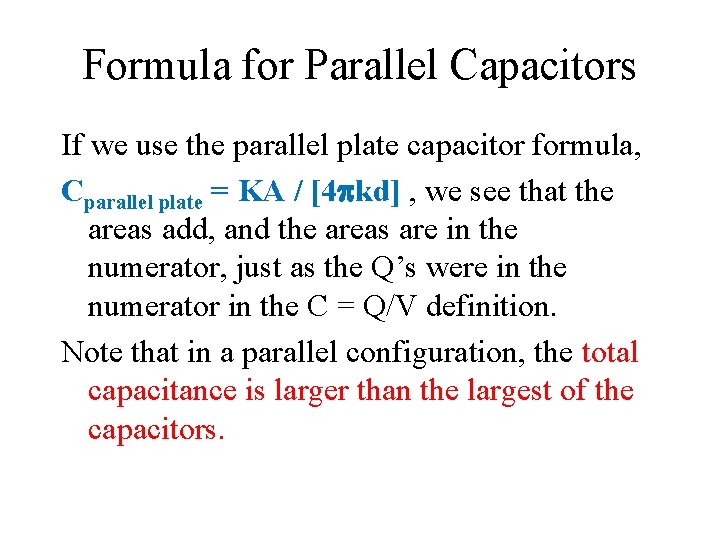

Parallel Circuit Note that for the parallel circuit the charge, QT, that leaves the battery is split with some going to C 1 and some going to C 2, so QT = Q 1+ Q 2. + Vbat QT + C 1 Q 1 + Q 2 C 2 Note that the voltages across C 1 and C 2 are both the same as the voltage across the battery.

Formula for Parallel Capacitors The result for the effective capacitance for a parallel connection is different than that for series, but we can start from the same two eqs. : C ≡ Q/V, or Cparallel plate = KA / [4 pkd]. For parallel, both plates are across the same voltage drop, so Vbat = Vtotal = V 1 = V 2. The charge can accumulate on both plates, so: Qtotal = Q 1 + Q 2. Since the Q’s are in the numerator, we have simply: Ceff = C 1 + C 2.

Formula for Parallel Capacitors If we use the parallel plate capacitor formula, Cparallel plate = KA / [4 pkd] , we see that the areas add, and the areas are in the numerator, just as the Q’s were in the numerator in the C = Q/V definition. Note that in a parallel configuration, the total capacitance is larger than the largest of the capacitors.

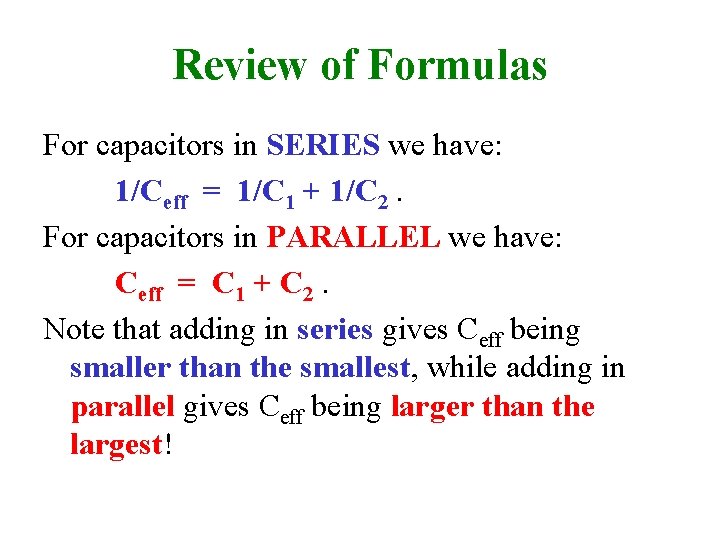

Review of Formulas For capacitors in SERIES we have: 1/Ceff = 1/C 1 + 1/C 2. For capacitors in PARALLEL we have: Ceff = C 1 + C 2. Note that adding in series gives Ceff being smaller than the smallest, while adding in parallel gives Ceff being larger than the largest!

Computer Homework The Computer Homework Vol. 3, #7 & #8 both give an introduction and problems dealing with capacitors. Your homework is #8, Capacitors Advanced. The program #7 on Capacitors Advanced is NOT assigned as graded homework.

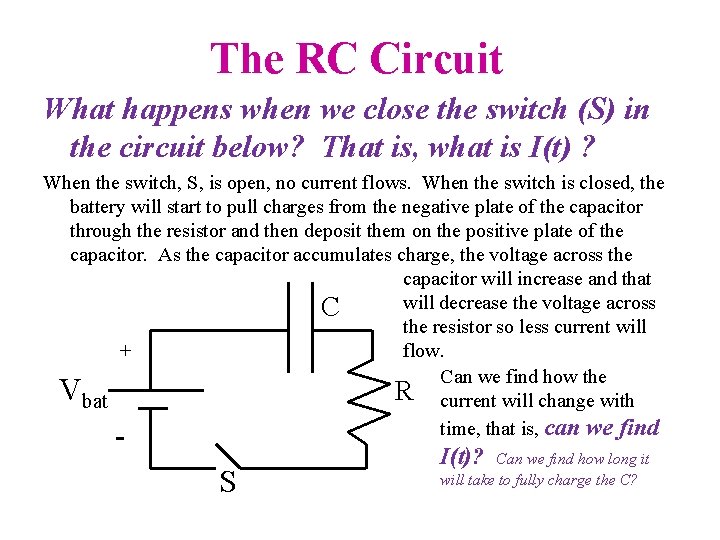

Review: Capacitors: Series: 1/Ceff = 1/C 1 + 1/C 2 Parallel: Ceff = C 1 + C 2 series gives smallest Ceff, parallel gives largest Ceff. Resistors: Series: Reff = R 1 + R 2 Parallel: 1/Reff = 1/R 1 + 1/R 2 series gives largest Reff, parallel gives smallest Reff.

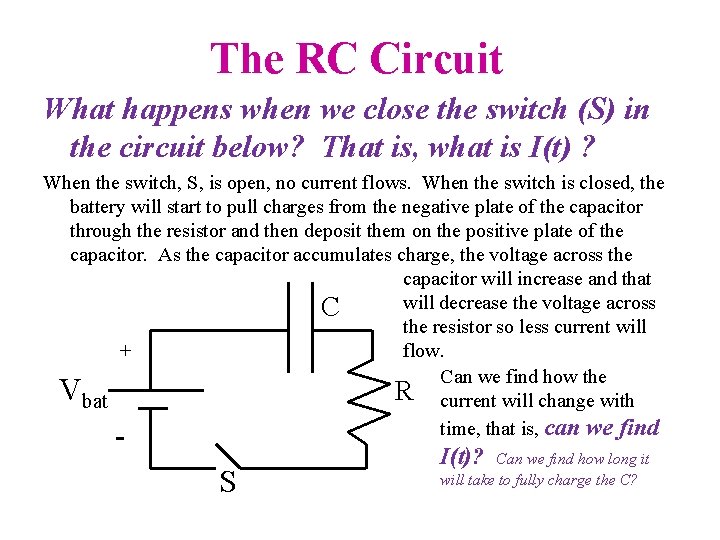

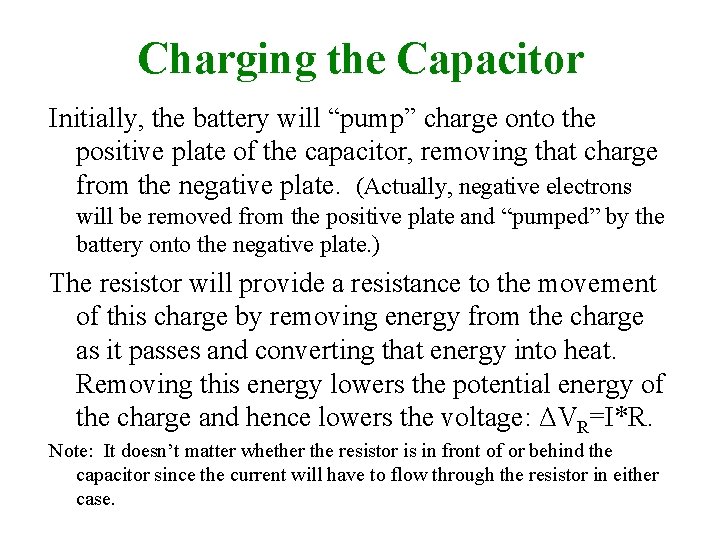

The RC Circuit What happens when we close the switch (S) in the circuit below? That is, what is I(t) ? When the switch, S, is open, no current flows. When the switch is closed, the battery will start to pull charges from the negative plate of the capacitor through the resistor and then deposit them on the positive plate of the capacitor. As the capacitor accumulates charge, the voltage across the capacitor will increase and that will decrease the voltage across C the resistor so less current will + flow. Can we find how the R current will change with bat time, that is, can we find V - S I(t)? Can we find how long it will take to fully charge the C?

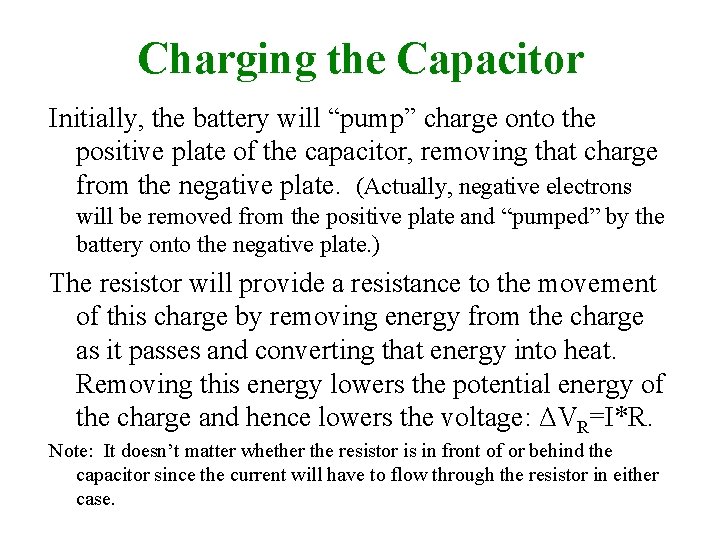

Charging the Capacitor Initially, the battery will “pump” charge onto the positive plate of the capacitor, removing that charge from the negative plate. (Actually, negative electrons will be removed from the positive plate and “pumped” by the battery onto the negative plate. ) The resistor will provide a resistance to the movement of this charge by removing energy from the charge as it passes and converting that energy into heat. Removing this energy lowers the potential energy of the charge and hence lowers the voltage: ΔVR=I*R. Note: It doesn’t matter whether the resistor is in front of or behind the capacitor since the current will have to flow through the resistor in either case.

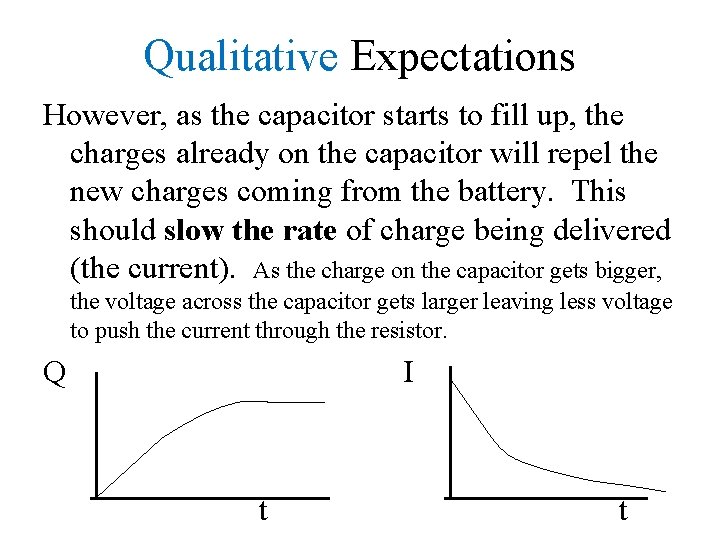

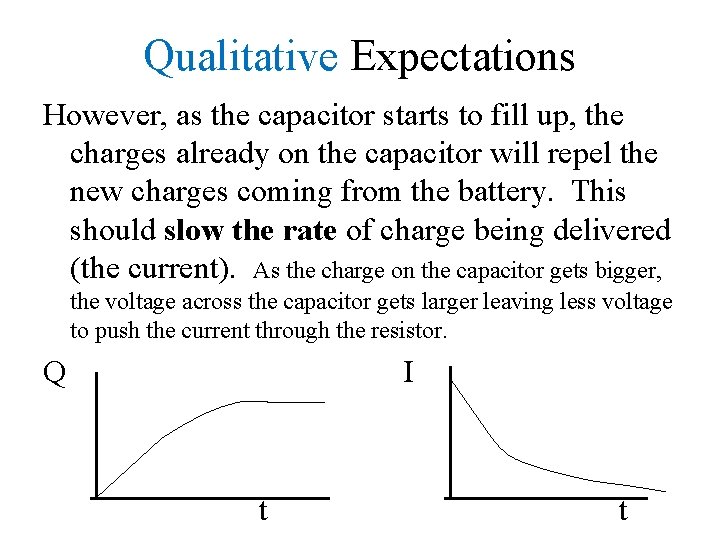

Qualitative Expectations However, as the capacitor starts to fill up, the charges already on the capacitor will repel the new charges coming from the battery. This should slow the rate of charge being delivered (the current). As the charge on the capacitor gets bigger, the voltage across the capacitor gets larger leaving less voltage to push the current through the resistor. Q I t t

Getting an equation How do we mathematically model this process? What fundamental equation (law) do we start from?

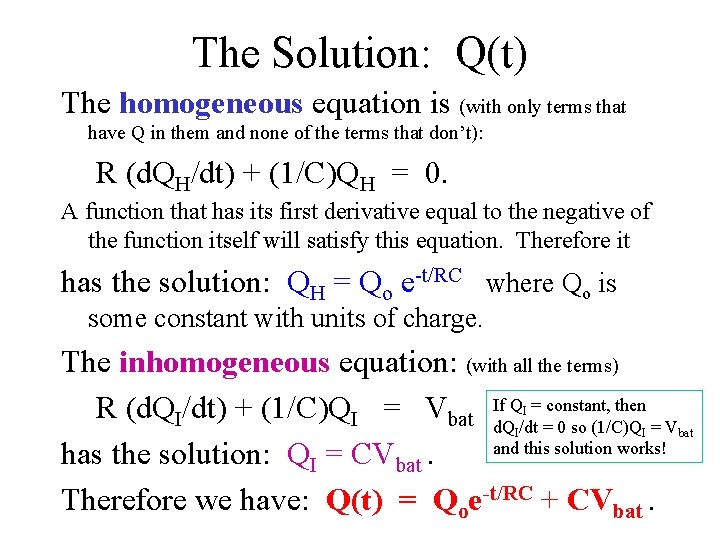

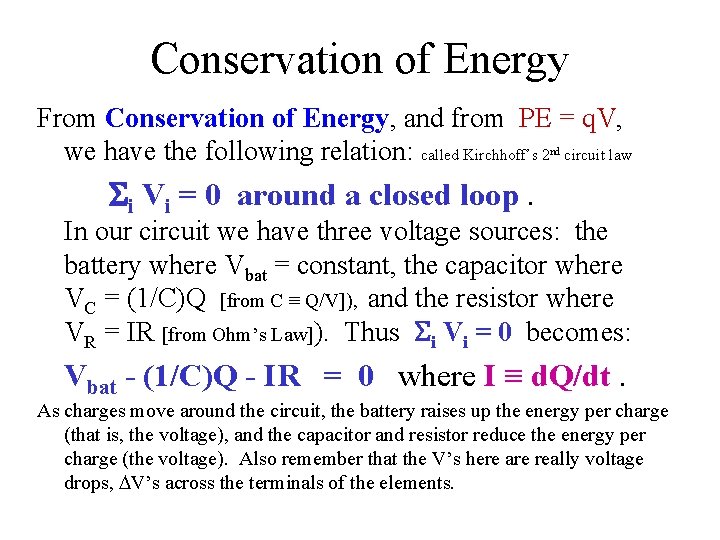

Conservation of Energy From Conservation of Energy, and from PE = q. V, we have the following relation: called Kirchhoff’s 2 circuit law nd i Vi = 0 around a closed loop. In our circuit we have three voltage sources: the battery where Vbat = constant, the capacitor where VC = (1/C)Q [from C ≡ Q/V]), and the resistor where VR = IR [from Ohm’s Law]). Thus i Vi = 0 becomes: Vbat - (1/C)Q - IR = 0 where I ≡ d. Q/dt. As charges move around the circuit, the battery raises up the energy per charge (that is, the voltage), and the capacitor and resistor reduce the energy per charge (the voltage). Also remember that the V’s here are really voltage drops, DV’s across the terminals of the elements.

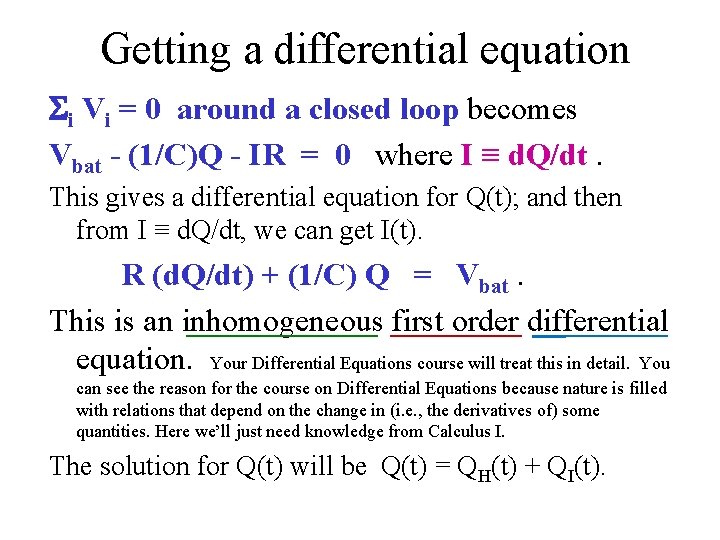

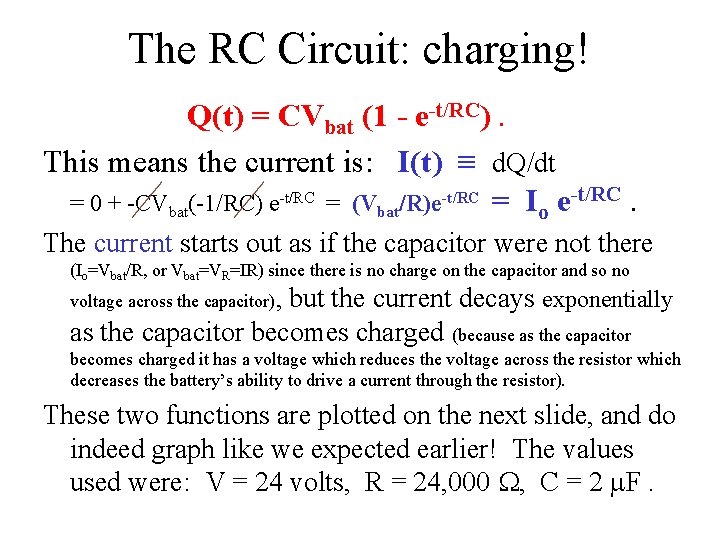

Getting a differential equation i Vi = 0 around a closed loop becomes Vbat - (1/C)Q - IR = 0 where I ≡ d. Q/dt. This gives a differential equation for Q(t); and then from I ≡ d. Q/dt, we can get I(t). R (d. Q/dt) + (1/C) Q = Vbat. This is an inhomogeneous first order differential equation. Your Differential Equations course will treat this in detail. You can see the reason for the course on Differential Equations because nature is filled with relations that depend on the change in (i. e. , the derivatives of) some quantities. Here we’ll just need knowledge from Calculus I. The solution for Q(t) will be Q(t) = QH(t) + QI(t).

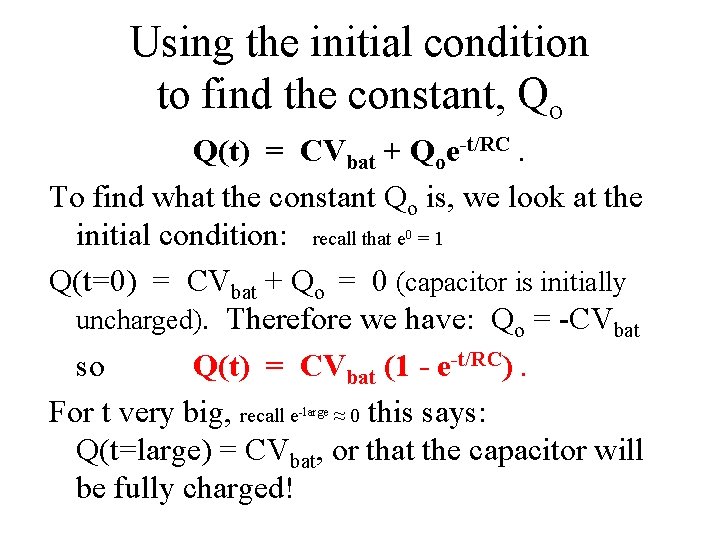

The Solution: Q(t) The homogeneous equation is (with only terms that have Q in them and none of the terms that don’t): R (d. QH/dt) + (1/C)QH = 0. A function that has its first derivative equal to the negative of the function itself will satisfy this equation. Therefore it has the solution: QH = Qo e-t/RC where Qo is some constant with units of charge. The inhomogeneous equation: (with all the terms) then R (d. QI/dt) + (1/C)QI = Vbat Ifd. QQ/dt= =constant, 0 so (1/C)Q = V and this solution works! has the solution: QI = CVbat. Therefore we have: Q(t) = Qoe-t/RC + CVbat. I I I bat

Using the initial condition to find the constant, Qo Q(t) = CVbat + Qoe-t/RC. To find what the constant Qo is, we look at the initial condition: recall that e 0 = 1 Q(t=0) = CVbat + Qo = 0 (capacitor is initially uncharged). Therefore we have: Qo = -CVbat so Q(t) = CVbat (1 - e-t/RC). For t very big, recall e-large ≈ 0 this says: Q(t=large) = CVbat, or that the capacitor will be fully charged!

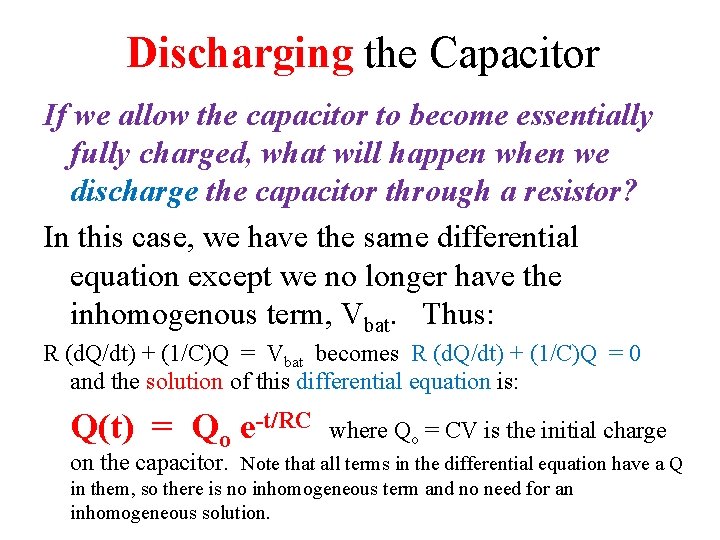

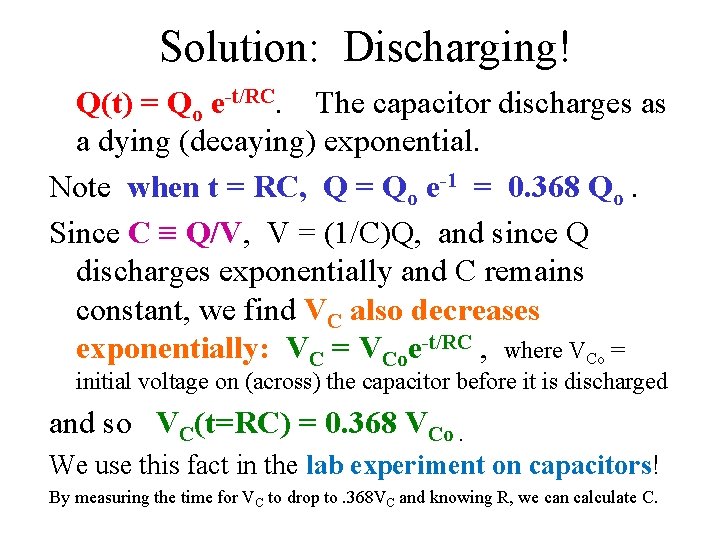

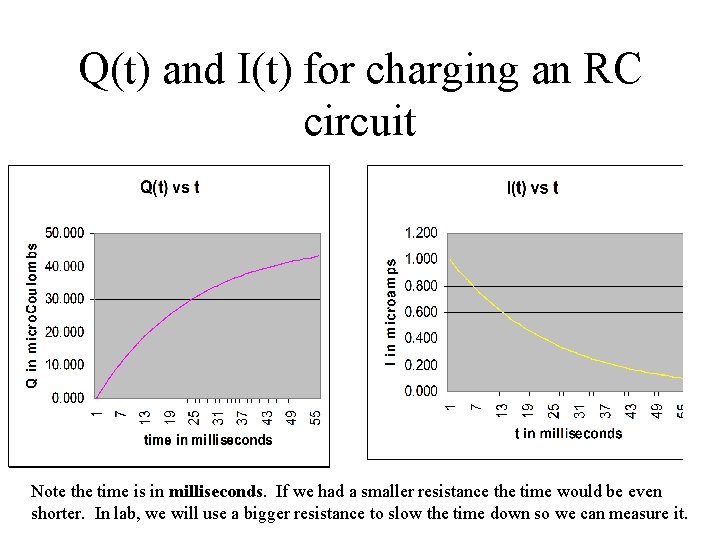

The RC Circuit: charging! Q(t) = CVbat (1 - e-t/RC). This means the current is: I(t) ≡ d. Q/dt = 0 + -CVbat(-1/RC) e-t/RC = (Vbat/R)e-t/RC = Io e-t/RC. The current starts out as if the capacitor were not there (Io=Vbat/R, or Vbat=VR=IR) since there is no charge on the capacitor and so no but the current decays exponentially as the capacitor becomes charged (because as the capacitor voltage across the capacitor), becomes charged it has a voltage which reduces the voltage across the resistor which decreases the battery’s ability to drive a current through the resistor). These two functions are plotted on the next slide, and do indeed graph like we expected earlier! The values used were: V = 24 volts, R = 24, 000 W, C = 2 m. F.

Q(t) and I(t) for charging an RC circuit Note the time is in milliseconds. If we had a smaller resistance the time would be even shorter. In lab, we will use a bigger resistance to slow the time down so we can measure it.

Discharging the Capacitor If we allow the capacitor to become essentially fully charged, what will happen when we discharge the capacitor through a resistor? In this case, we have the same differential equation except we no longer have the inhomogenous term, Vbat. Thus: R (d. Q/dt) + (1/C)Q = Vbat becomes R (d. Q/dt) + (1/C)Q = 0 and the solution of this differential equation is: Q(t) = Qo e-t/RC where Qo = CV is the initial charge on the capacitor. Note that all terms in the differential equation have a Q in them, so there is no inhomogeneous term and no need for an inhomogeneous solution.

Solution: Discharging! Q(t) = Qo e-t/RC. The capacitor discharges as a dying (decaying) exponential. Note when t = RC, Q = Qo e-1 = 0. 368 Qo. Since C ≡ Q/V, V = (1/C)Q, and since Q discharges exponentially and C remains constant, we find VC also decreases exponentially: VC = VCoe-t/RC , where VCo = initial voltage on (across) the capacitor before it is discharged and so VC(t=RC) = 0. 368 VCo. We use this fact in the lab experiment on capacitors! By measuring the time for VC to drop to. 368 VC and knowing R, we can calculate C.

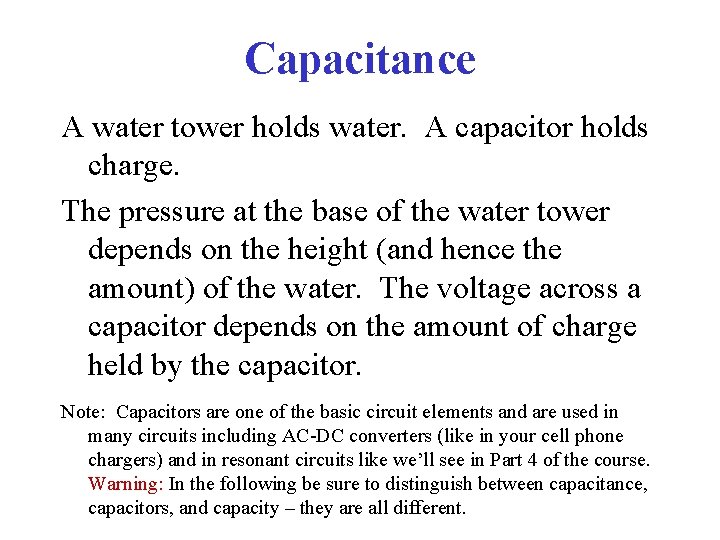

Units From the expression for a discharging capacitor: Q(t) = Qoe-t/RC , we see that the quantity RC must have units of time since an exponent can’t have units. Let’s check it out: From I ≡ d. Q/dt, Amp = Coul/sec From Ohms law: V = IR, Ohm = W = Volt/Amp; By definition: C ≡ Q/V, Farad = Coul/Volt. units of RC: W*Farads = [Volt/Amp]*(Coul/Volt) = Coul/Amp = Coul/[Coul/sec] = sec. Since RC does have the units of time, the RC value is called the RC time constant and given the symbol .

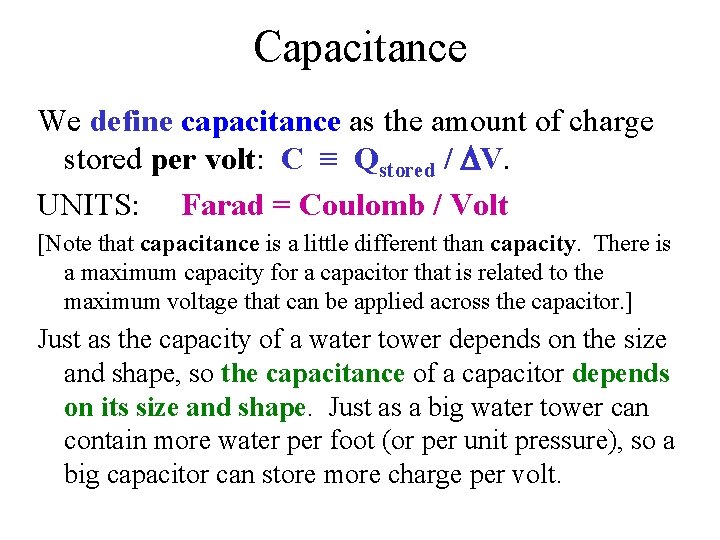

RC Time Constant and Half Life Q(t) = Qo e-t/RC When t = RC, Q decreases by a factor of 1/e ≈. 368. This time is called the RC time constant, . Is there a time in which Q decreases by ½ (usually called the half life, T)? Q(T) ≡ ½ Qo = Qo e-T/RC or ln(½) = -T/RC or Thalf life = RC ln(2) ≈. 693 or Thalf life = ln(2).