Calculator steps n The calculator steps for this

![[A] Enter Observed values as Matrix 1: 2 nd x-1 [B] Enter Expected values [A] Enter Observed values as Matrix 1: 2 nd x-1 [B] Enter Expected values](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/19a1ace7e1f78dae4ecfc74c8600e6f1/image-13.jpg)

- Slides: 48

Calculator steps: n The calculator steps for this section can be found on You. Tube or by clicking: Click here Bluman, Chapter 11 1

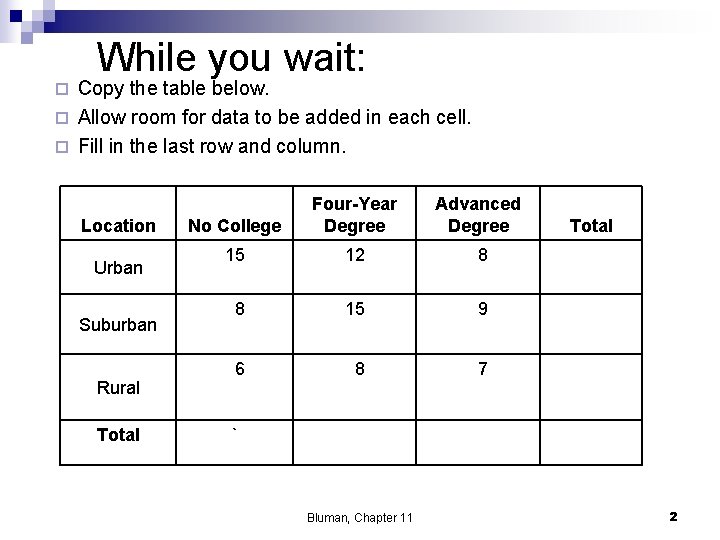

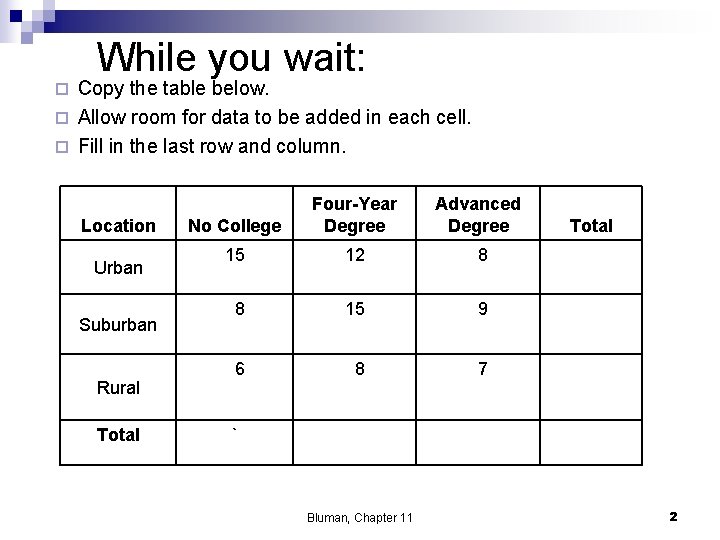

While you wait: Copy the table below. ¨ Allow room for data to be added in each cell. ¨ Fill in the last row and column. ¨ Location Urban Suburban Rural Total No College Four-Year Degree Advanced Degree 15 12 8 8 15 9 6 8 7 Total ` Bluman, Chapter 11 2

Tests Using Contingency Tables Sec: 11. 2 Bluman, Chapter 11 3

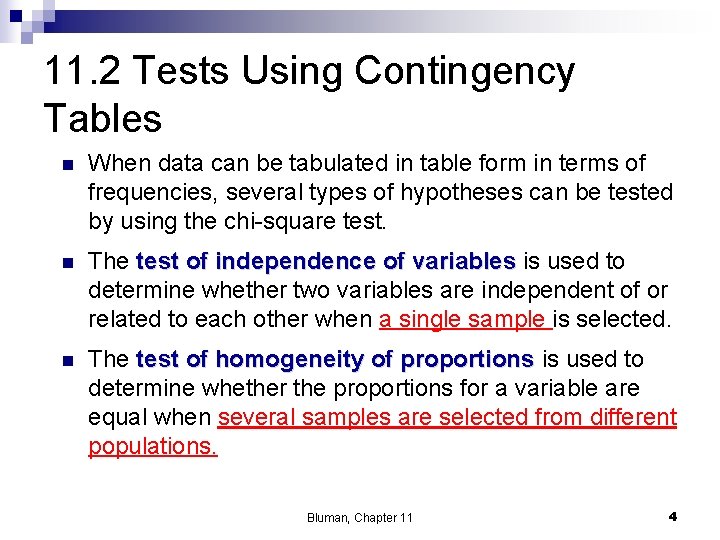

11. 2 Tests Using Contingency Tables n When data can be tabulated in table form in terms of frequencies, several types of hypotheses can be tested by using the chi-square test. n The test of independence of variables is used to determine whether two variables are independent of or related to each other when a single sample is selected. n The test of homogeneity of proportions is used to determine whether the proportions for a variable are equal when several samples are selected from different populations. Bluman, Chapter 11 4

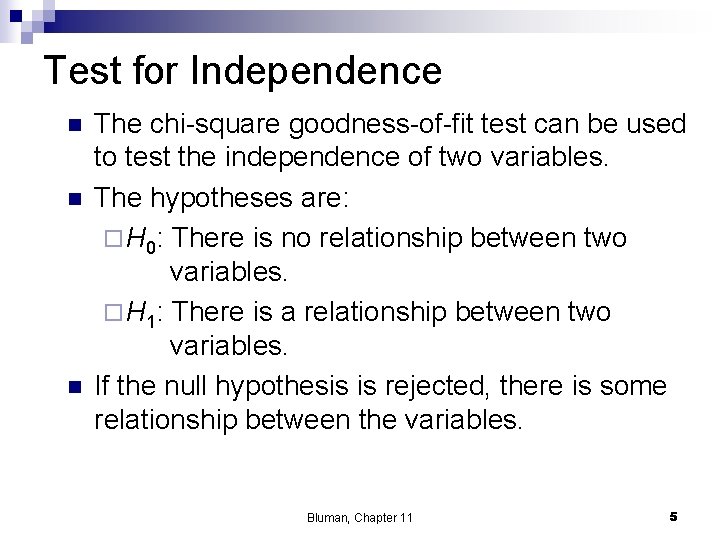

Test for Independence n n n The chi-square goodness-of-fit test can be used to test the independence of two variables. The hypotheses are: ¨ H 0: There is no relationship between two variables. ¨ H 1: There is a relationship between two variables. If the null hypothesis is rejected, there is some relationship between the variables. Bluman, Chapter 11 5

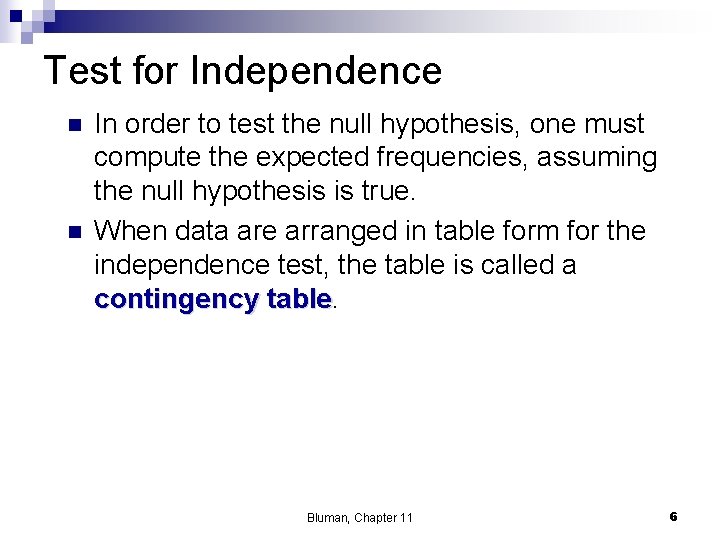

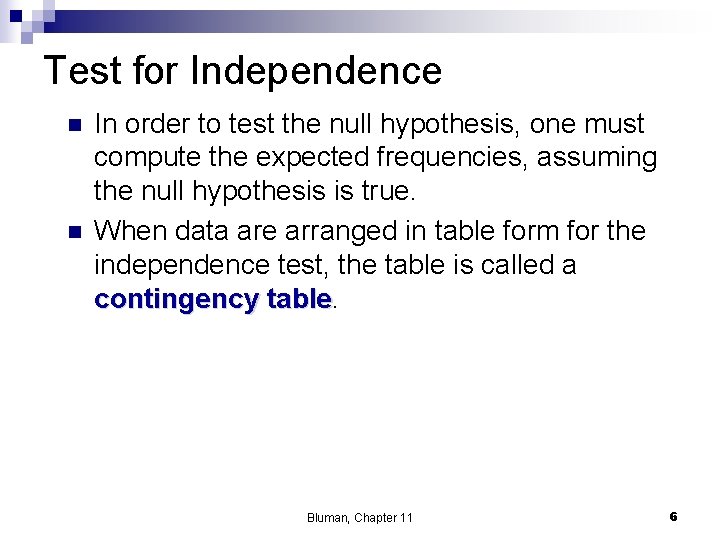

Test for Independence n n In order to test the null hypothesis, one must compute the expected frequencies, assuming the null hypothesis is true. When data are arranged in table form for the independence test, the table is called a contingency table Bluman, Chapter 11 6

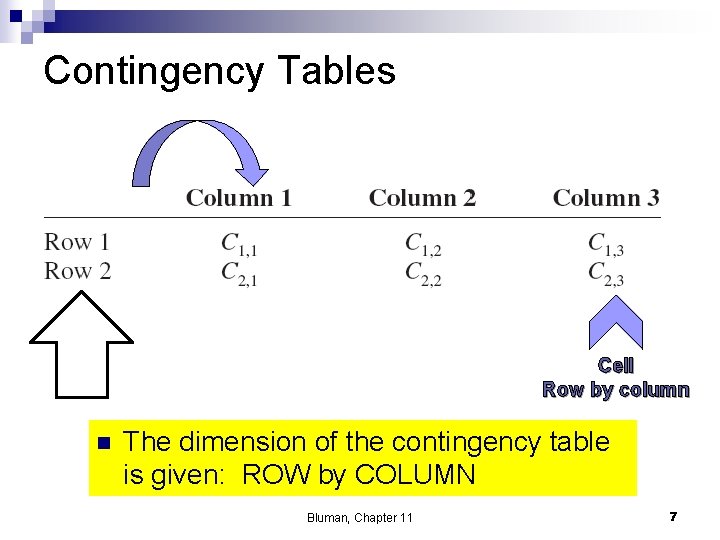

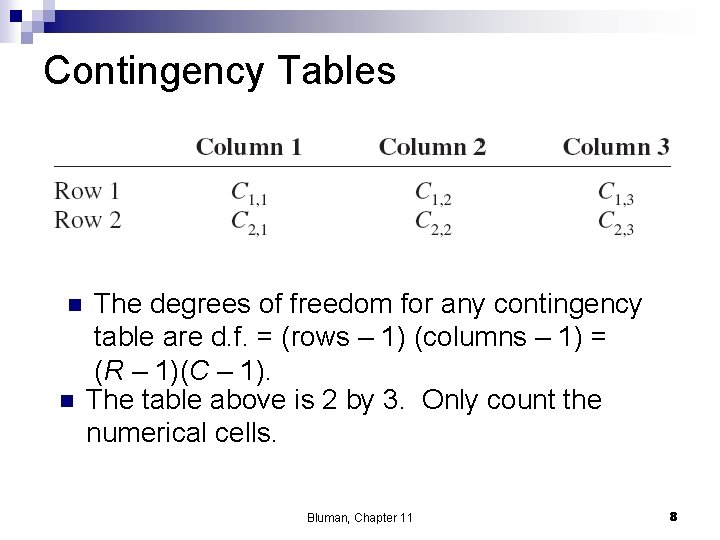

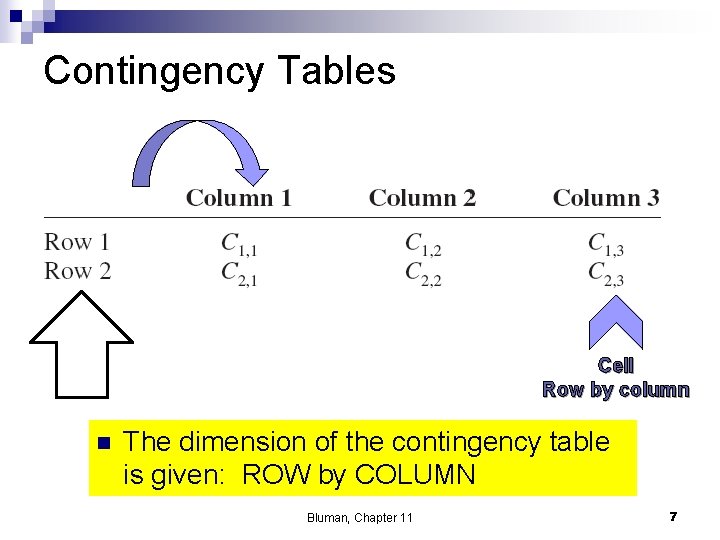

Contingency Tables Cell Row by column n The dimension of the contingency table is given: ROW by COLUMN Bluman, Chapter 11 7

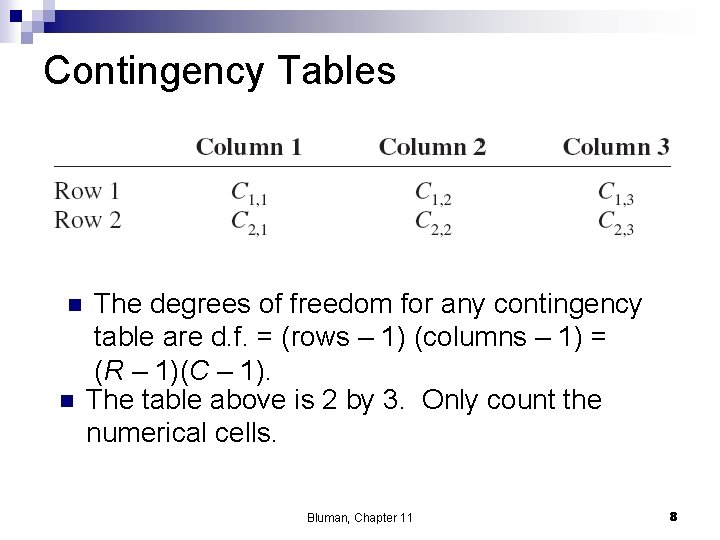

Contingency Tables n n The degrees of freedom for any contingency table are d. f. = (rows – 1) (columns – 1) = (R – 1)(C – 1). The table above is 2 by 3. Only count the numerical cells. Bluman, Chapter 11 8

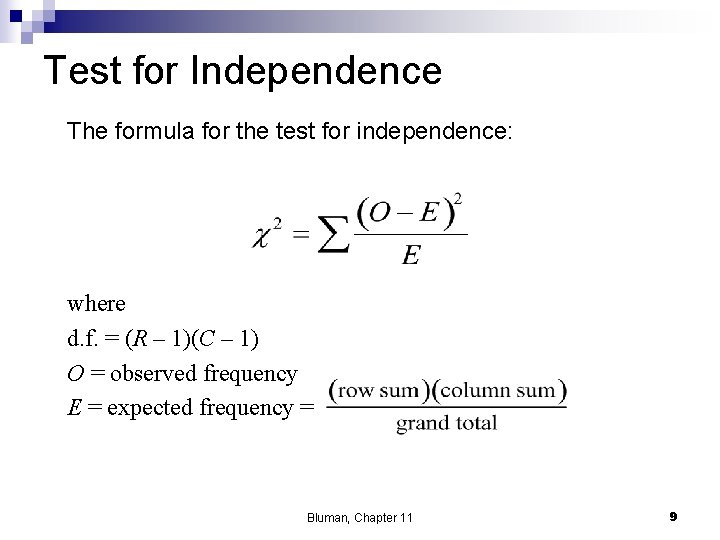

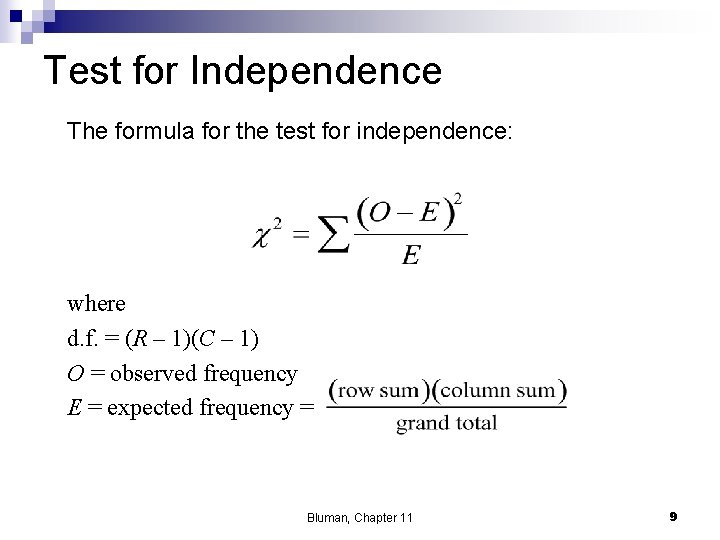

Test for Independence The formula for the test for independence: where d. f. = (R – 1)(C – 1) O = observed frequency E = expected frequency = Bluman, Chapter 11 9

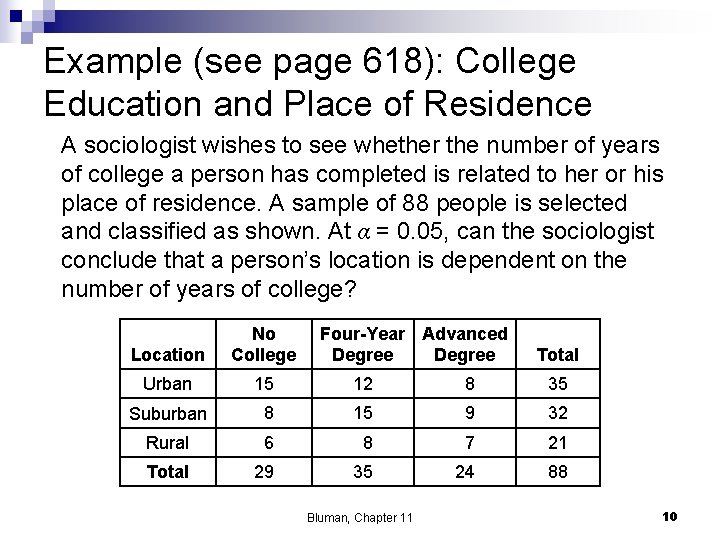

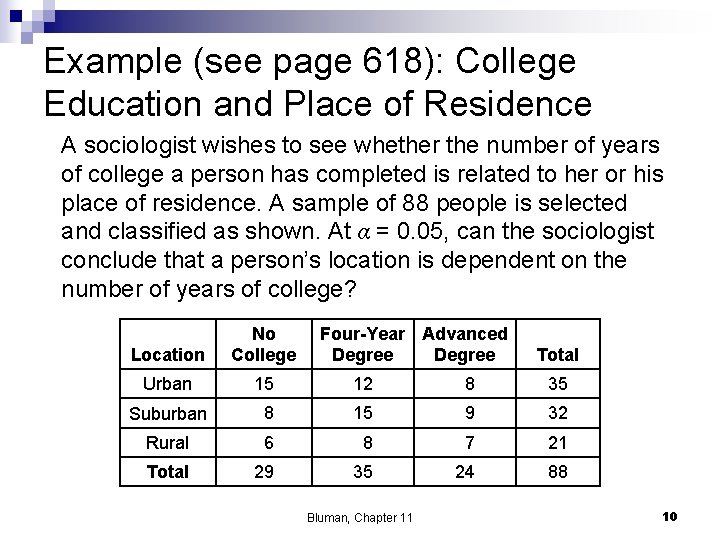

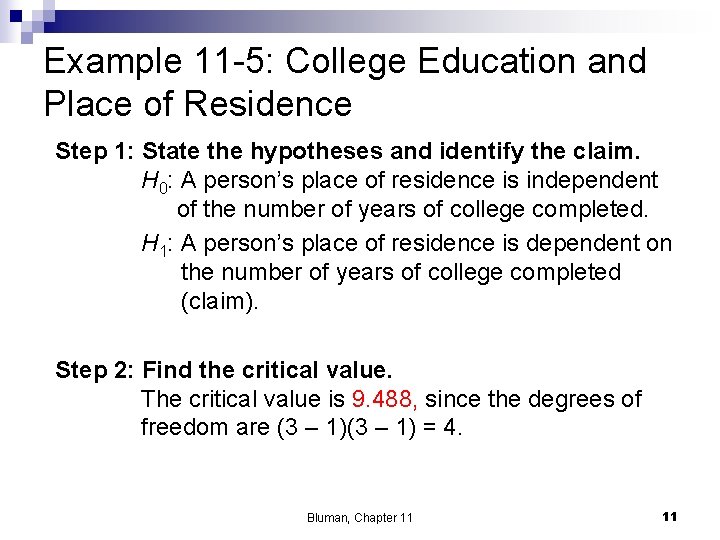

Example (see page 618): College Education and Place of Residence A sociologist wishes to see whether the number of years of college a person has completed is related to her or his place of residence. A sample of 88 people is selected and classified as shown. At α = 0. 05, can the sociologist conclude that a person’s location is dependent on the number of years of college? Location No College Four-Year Advanced Degree Urban 15 12 8 35 Suburban 8 15 9 32 Rural 6 8 7 21 Total 29 35 24 88 Bluman, Chapter 11 Total 10

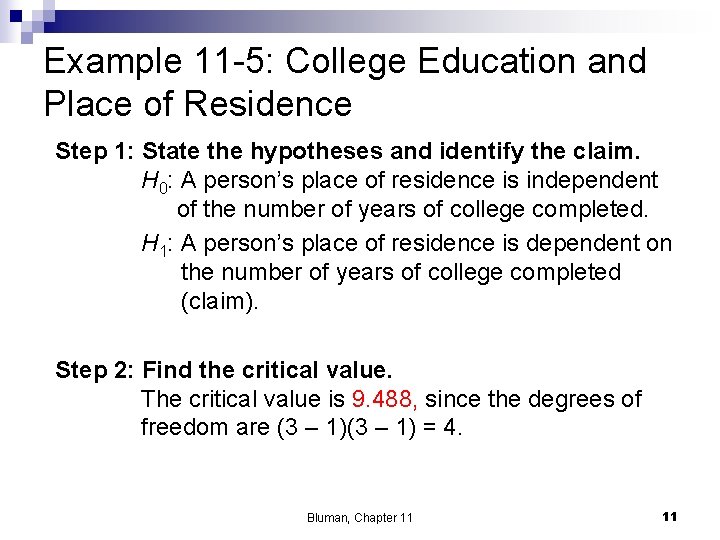

Example 11 -5: College Education and Place of Residence Step 1: State the hypotheses and identify the claim. H 0: A person’s place of residence is independent of the number of years of college completed. H 1: A person’s place of residence is dependent on the number of years of college completed (claim). Step 2: Find the critical value. The critical value is 9. 488, since the degrees of freedom are (3 – 1) = 4. Bluman, Chapter 11 11

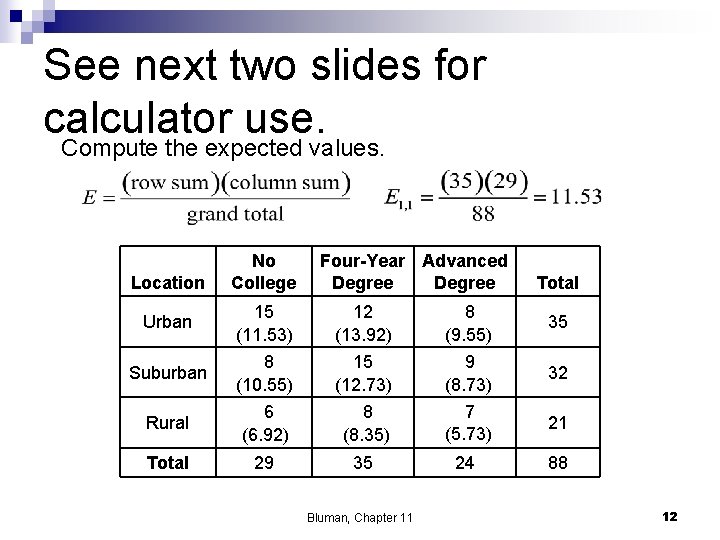

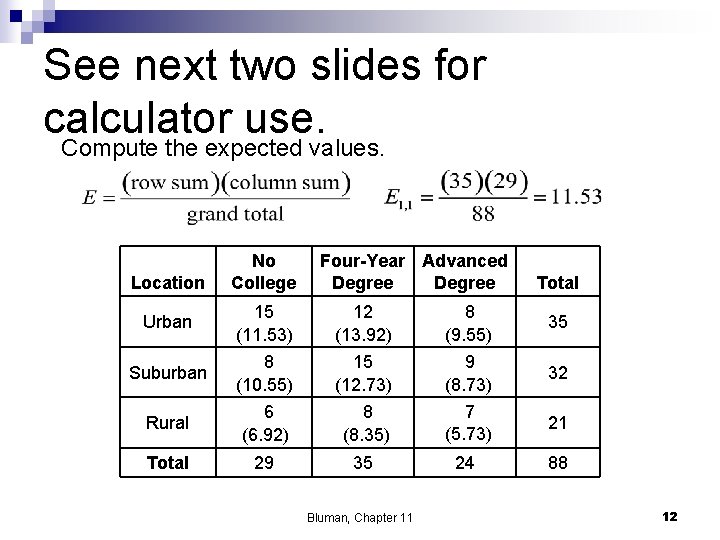

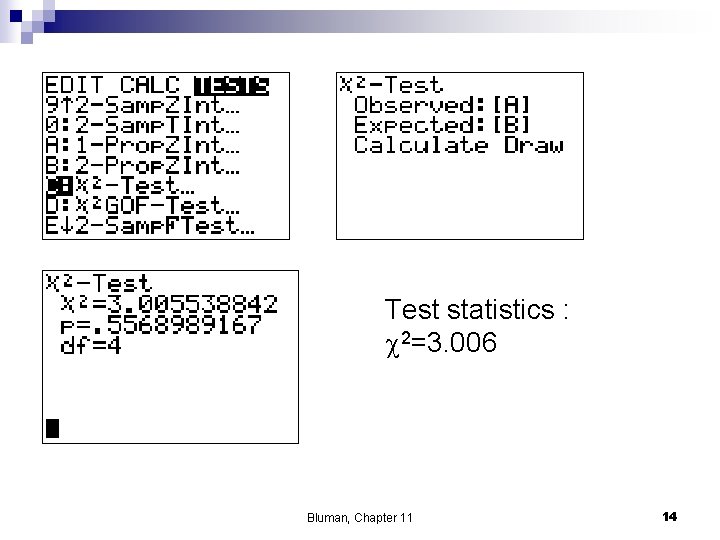

See next two slides for calculator use. Compute the expected values. Location No College Four-Year Advanced Degree Total Urban 15 (11. 53) 12 (13. 92) 8 (9. 55) 35 Suburban 8 (10. 55) 15 (12. 73) 9 (8. 73) 32 Rural 6 (6. 92) 8 (8. 35) 7 (5. 73) 21 Total 29 35 24 88 Bluman, Chapter 11 12

![A Enter Observed values as Matrix 1 2 nd x1 B Enter Expected values [A] Enter Observed values as Matrix 1: 2 nd x-1 [B] Enter Expected values](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/19a1ace7e1f78dae4ecfc74c8600e6f1/image-13.jpg)

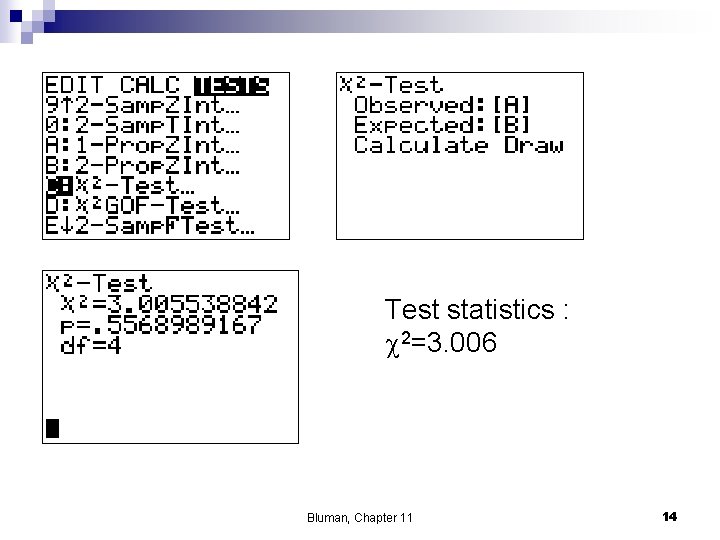

[A] Enter Observed values as Matrix 1: 2 nd x-1 [B] Enter Expected values as Matrix Bluman, Chapter 11 13

Test statistics : c 2=3. 006 Bluman, Chapter 11 14

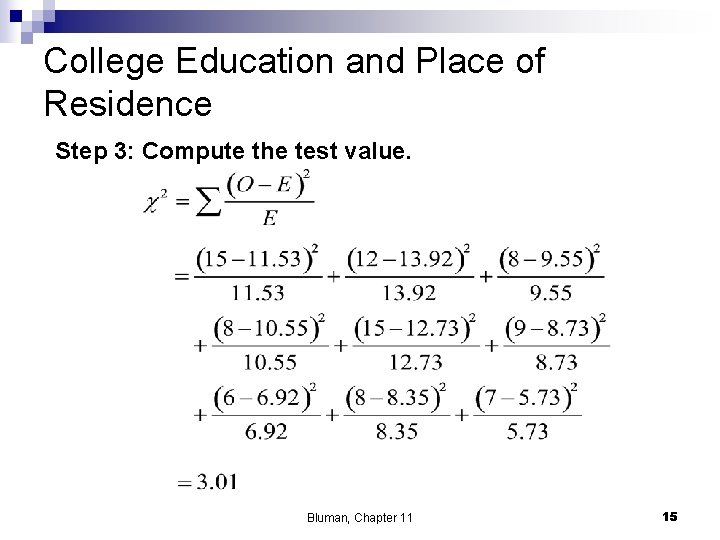

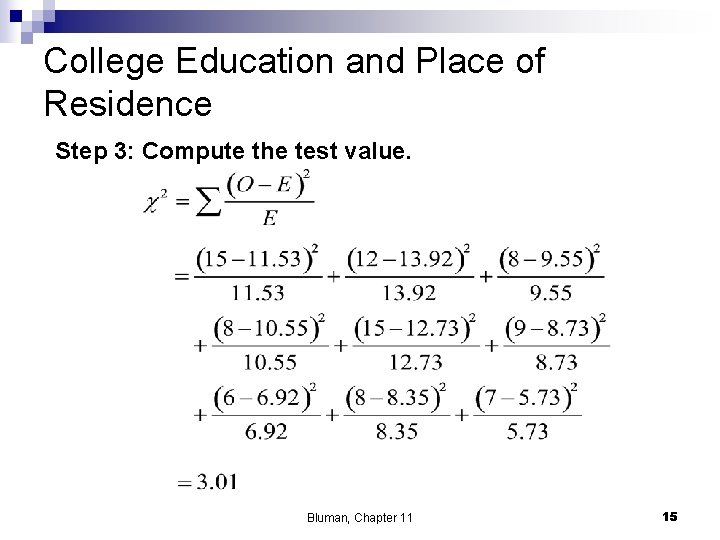

College Education and Place of Residence Step 3: Compute the test value. Bluman, Chapter 11 15

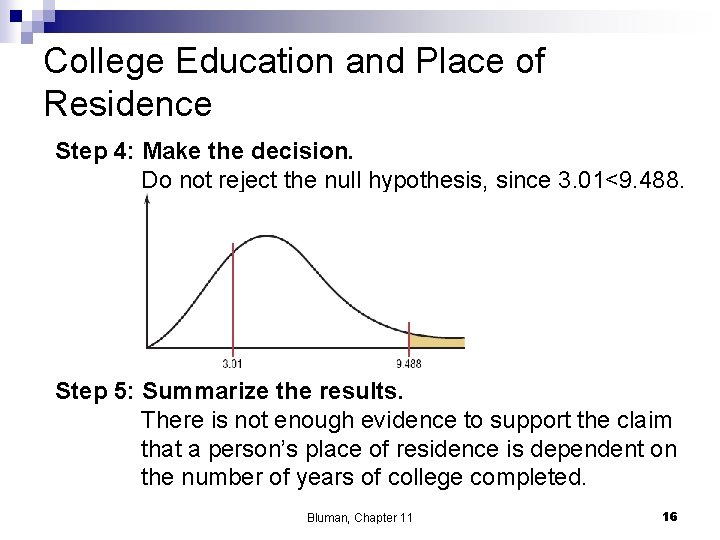

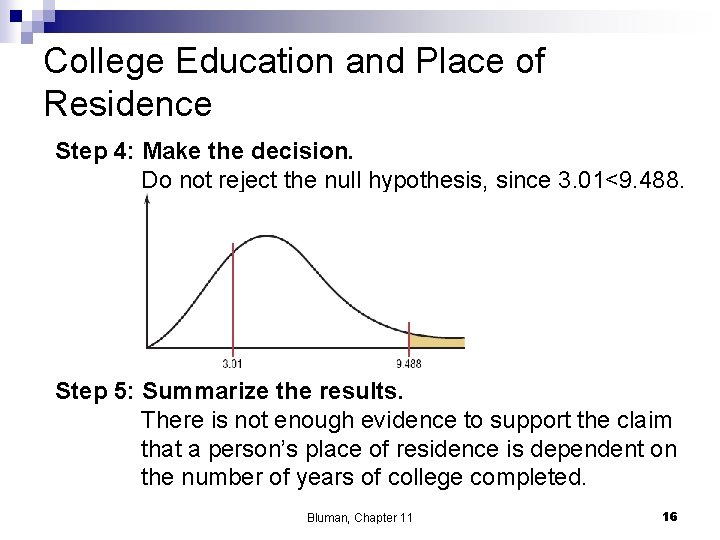

College Education and Place of Residence Step 4: Make the decision. Do not reject the null hypothesis, since 3. 01<9. 488. Step 5: Summarize the results. There is not enough evidence to support the claim that a person’s place of residence is dependent on the number of years of college completed. Bluman, Chapter 11 16

Chapter 11 Other Chi-Square Tests Section 11 -2 Example 11 -6 Page # 610 Bluman, Chapter 11 17

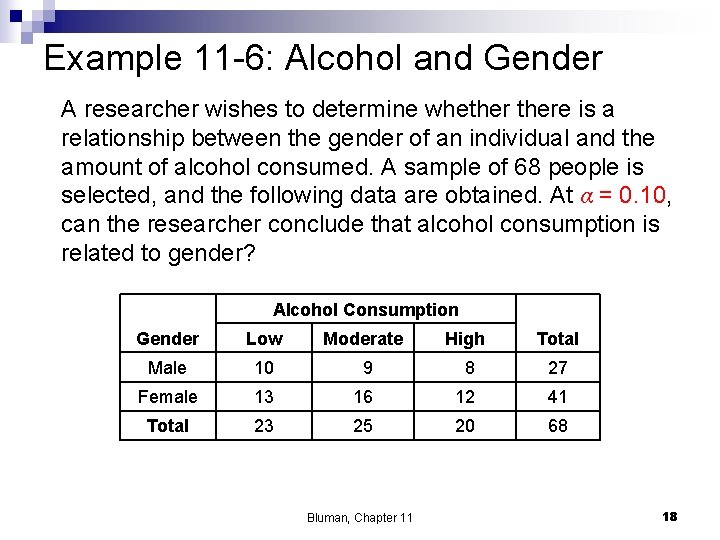

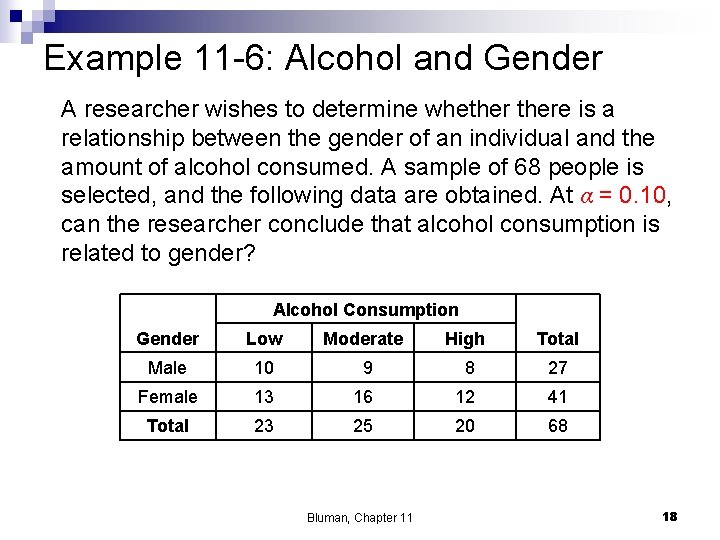

Example 11 -6: Alcohol and Gender A researcher wishes to determine whethere is a relationship between the gender of an individual and the amount of alcohol consumed. A sample of 68 people is selected, and the following data are obtained. At α = 0. 10, can the researcher conclude that alcohol consumption is related to gender? Alcohol Consumption Gender Low Moderate High Total Male 10 9 8 27 Female 13 16 12 41 Total 23 25 20 68 Bluman, Chapter 11 18

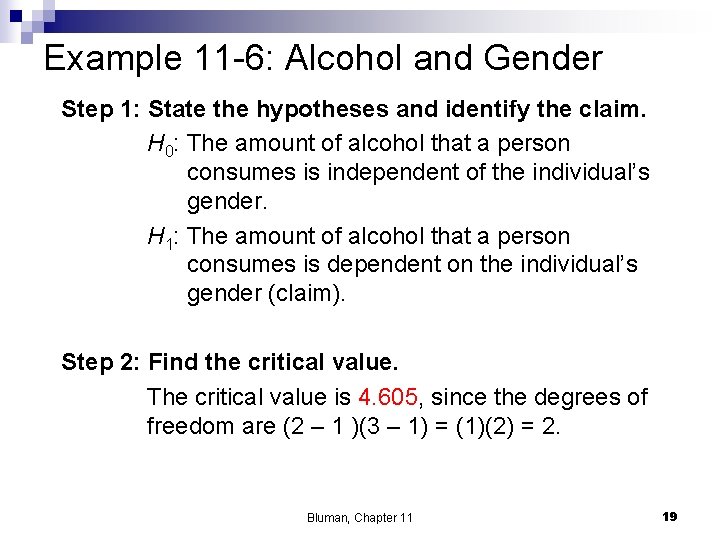

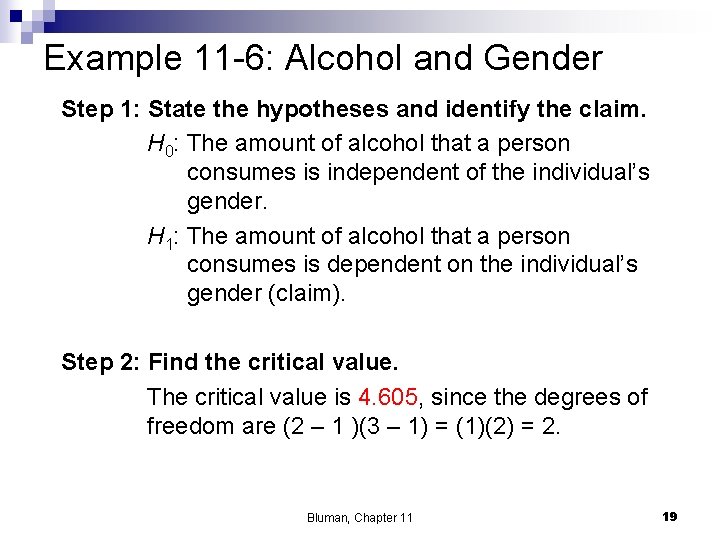

Example 11 -6: Alcohol and Gender Step 1: State the hypotheses and identify the claim. H 0: The amount of alcohol that a person consumes is independent of the individual’s gender. H 1: The amount of alcohol that a person consumes is dependent on the individual’s gender (claim). Step 2: Find the critical value. The critical value is 4. 605, since the degrees of freedom are (2 – 1 )(3 – 1) = (1)(2) = 2. Bluman, Chapter 11 19

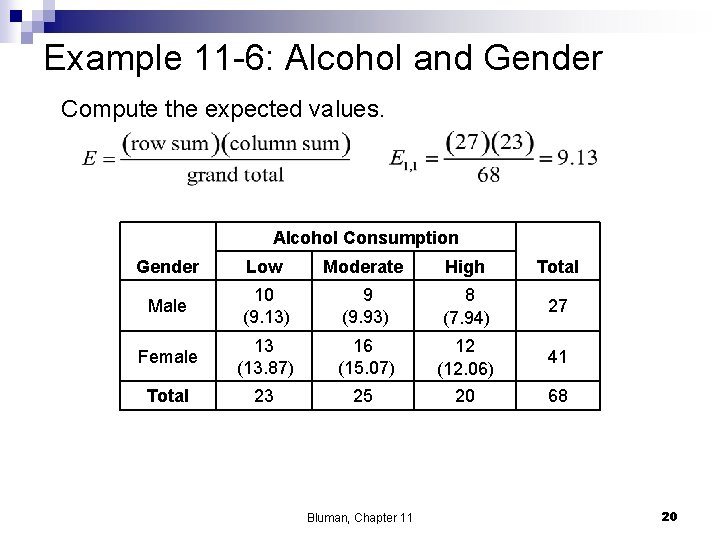

Example 11 -6: Alcohol and Gender Compute the expected values. Alcohol Consumption Gender Low Moderate High Total Male 10 (9. 13) 9 (9. 93) 8 (7. 94) 27 Female 13 (13. 87) 16 (15. 07) 12 (12. 06) 41 Total 23 25 20 68 Bluman, Chapter 11 20

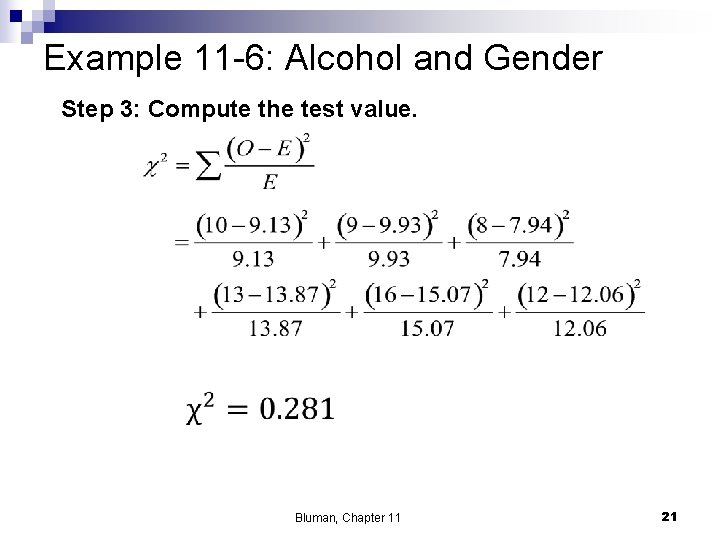

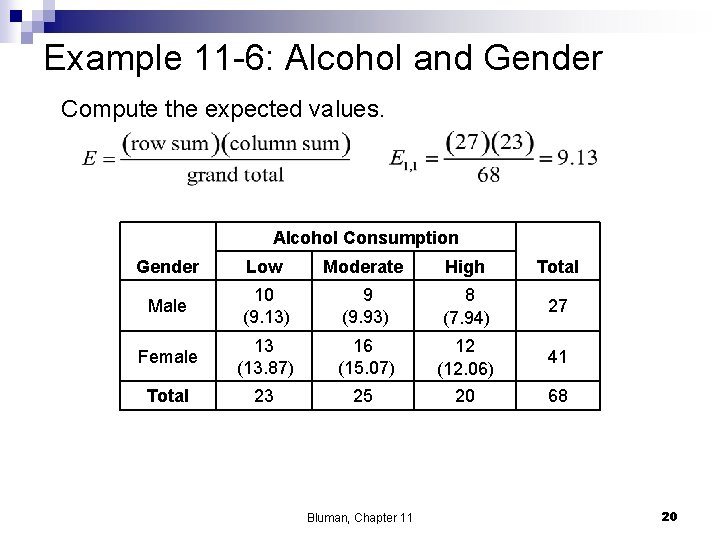

Example 11 -6: Alcohol and Gender Step 3: Compute the test value. Bluman, Chapter 11 21

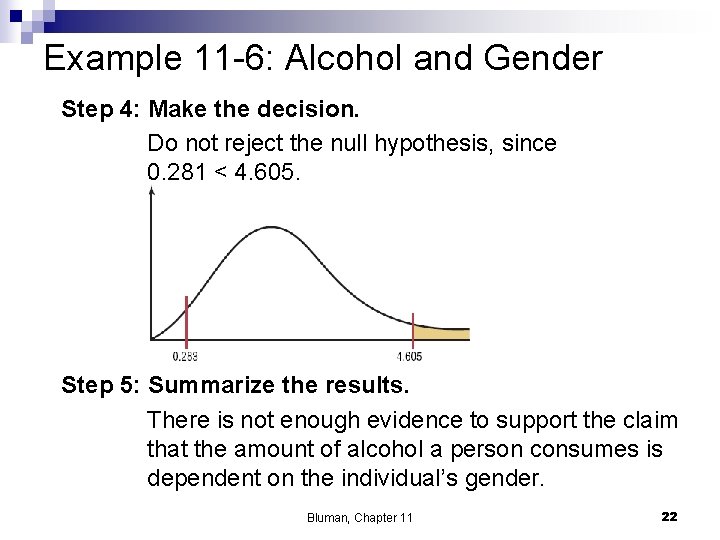

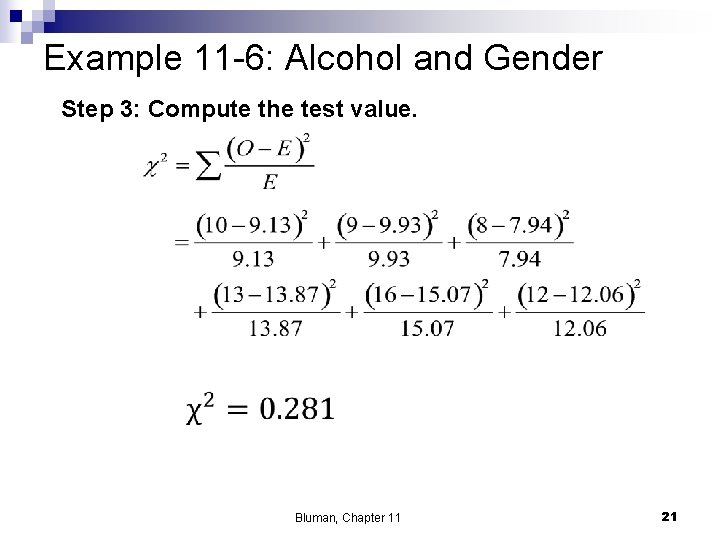

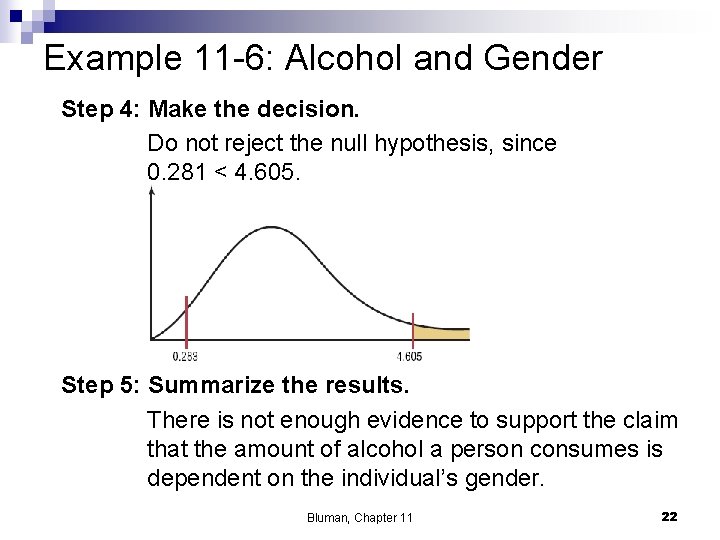

Example 11 -6: Alcohol and Gender Step 4: Make the decision. Do not reject the null hypothesis, since 0. 281 < 4. 605. . Step 5: Summarize the results. There is not enough evidence to support the claim that the amount of alcohol a person consumes is dependent on the individual’s gender. Bluman, Chapter 11 22

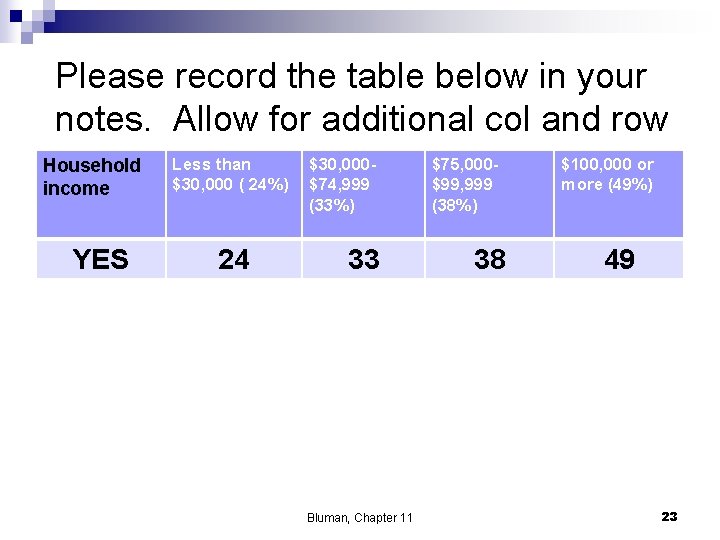

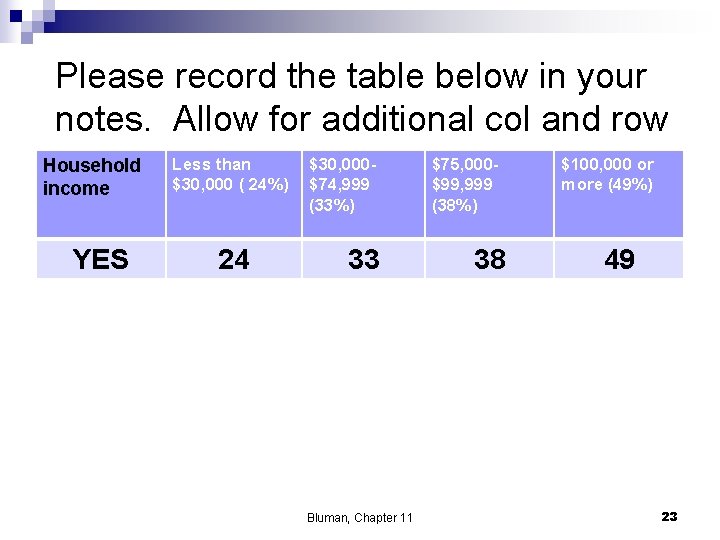

Please record the table below in your notes. Allow for additional col and row Household income YES Less than $30, 000 ( 24%) 24 $30, 000$74, 999 (33%) 33 Bluman, Chapter 11 $75, 000$99, 999 (38%) 38 $100, 000 or more (49%) 49 23

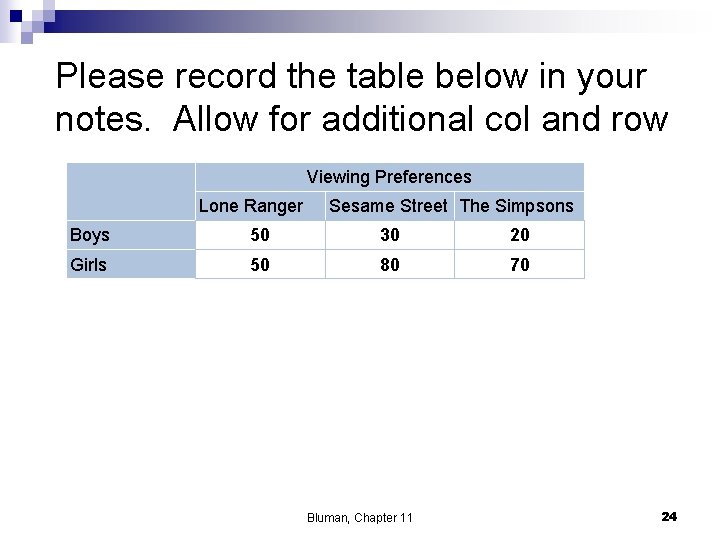

Please record the table below in your notes. Allow for additional col and row Viewing Preferences Lone Ranger Sesame Street The Simpsons Boys 50 30 20 Girls 50 80 70 Bluman, Chapter 11 24

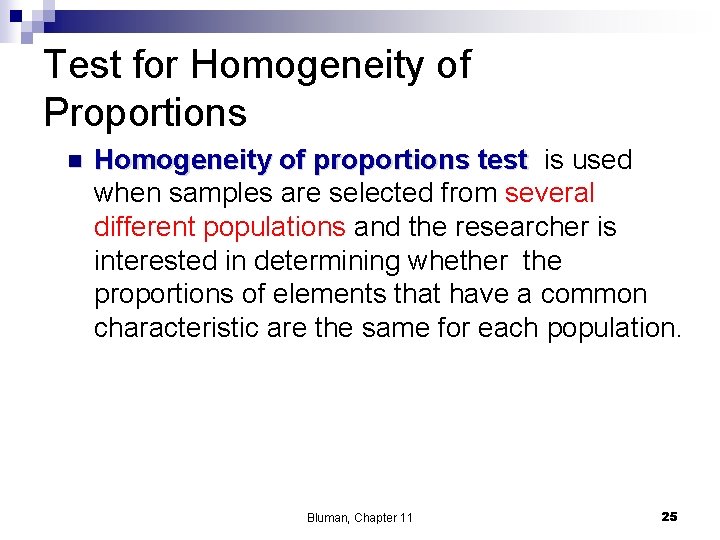

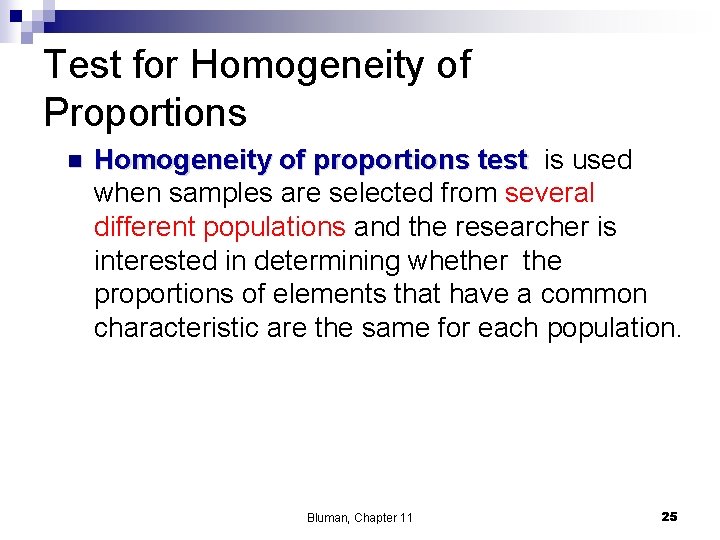

Test for Homogeneity of Proportions n Homogeneity of proportions test is used when samples are selected from several different populations and the researcher is interested in determining whether the proportions of elements that have a common characteristic are the same for each population. Bluman, Chapter 11 25

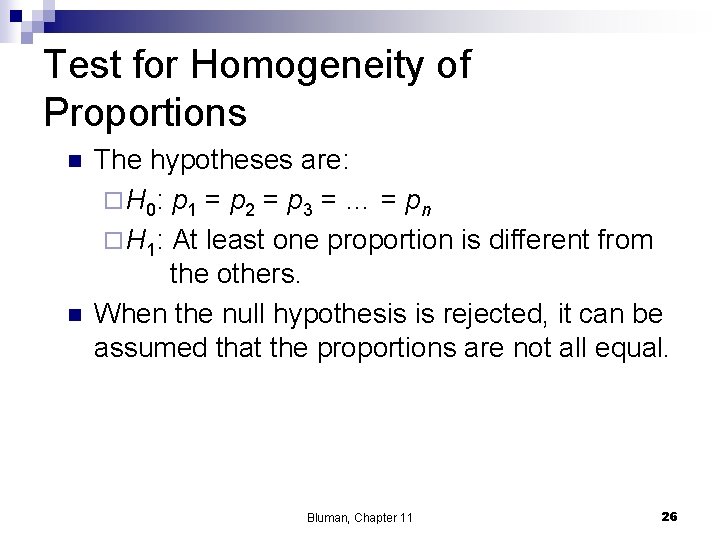

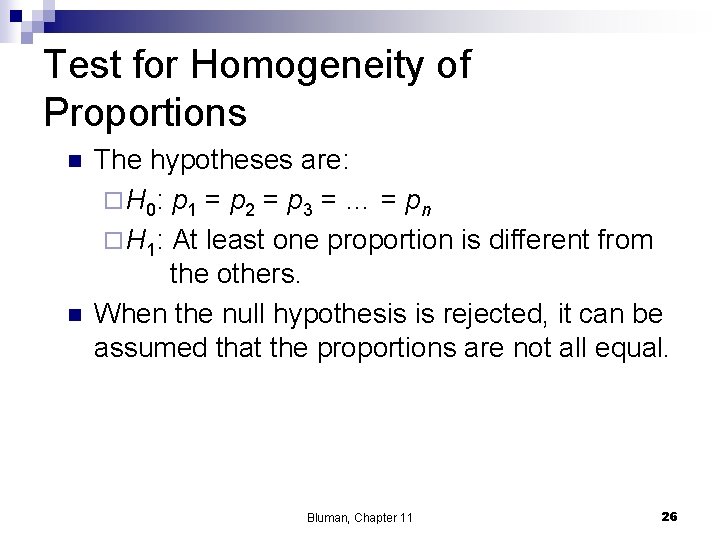

Test for Homogeneity of Proportions n n The hypotheses are: ¨ H 0: p 1 = p 2 = p 3 = … = pn ¨ H 1: At least one proportion is different from the others. When the null hypothesis is rejected, it can be assumed that the proportions are not all equal. Bluman, Chapter 11 26

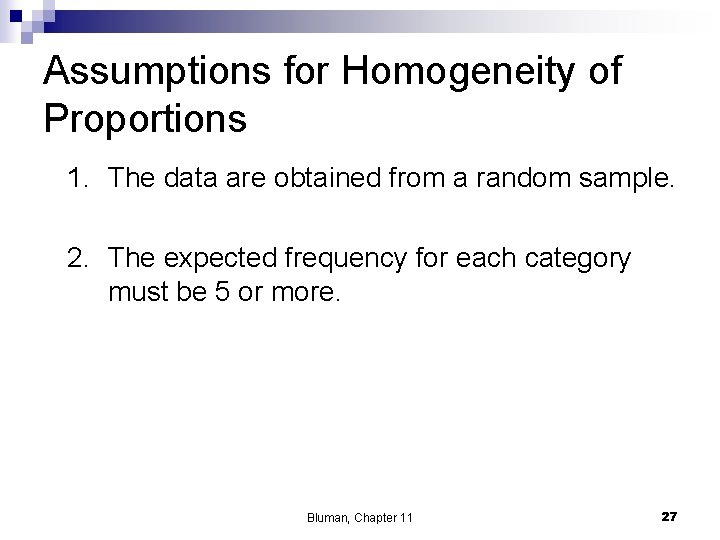

Assumptions for Homogeneity of Proportions 1. The data are obtained from a random sample. 2. The expected frequency for each category must be 5 or more. Bluman, Chapter 11 27

Chapter 11 Other Chi-Square Tests Section 11 -2 Example 11 -7 Page #611 Bluman, Chapter 11 28

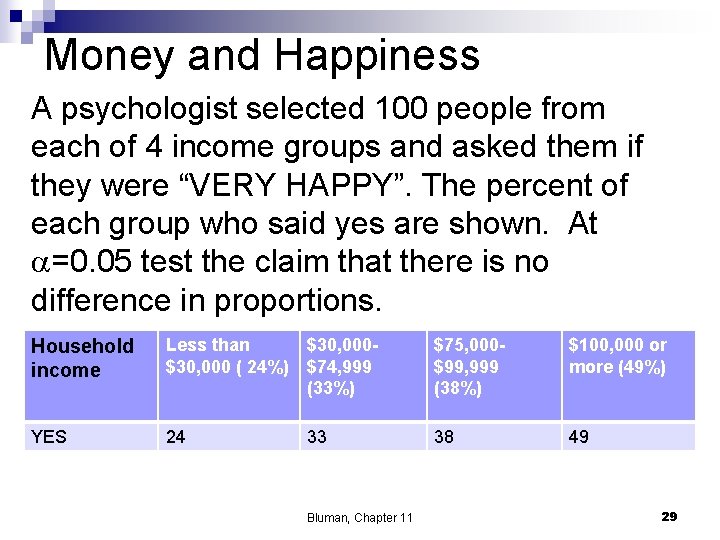

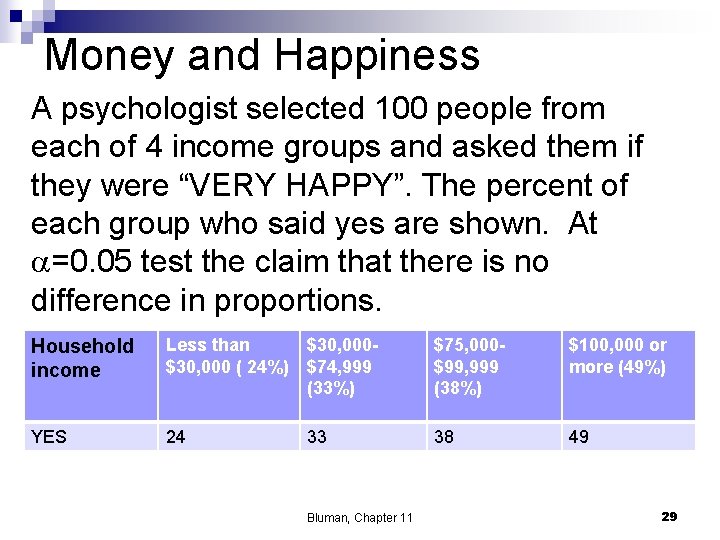

Money and Happiness A psychologist selected 100 people from each of 4 income groups and asked them if they were “VERY HAPPY”. The percent of each group who said yes are shown. At a=0. 05 test the claim that there is no difference in proportions. Household income Less than $30, 000 ( 24%) $30, 000$74, 999 (33%) $75, 000$99, 999 (38%) $100, 000 or more (49%) YES 24 33 38 49 Bluman, Chapter 11 29

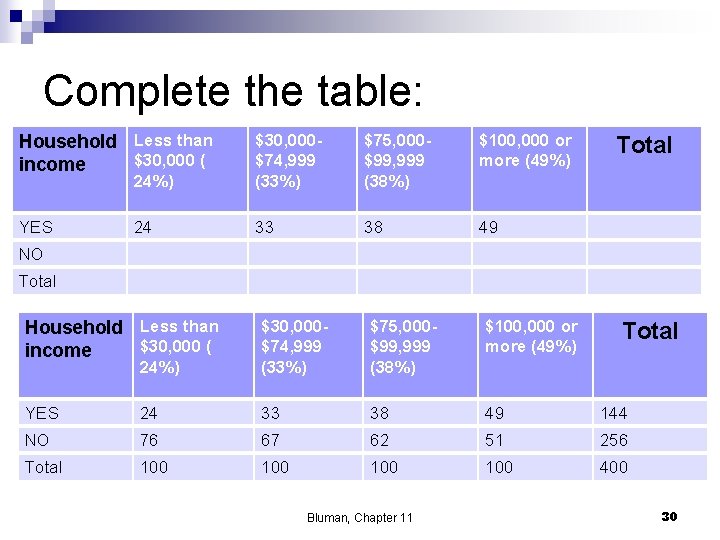

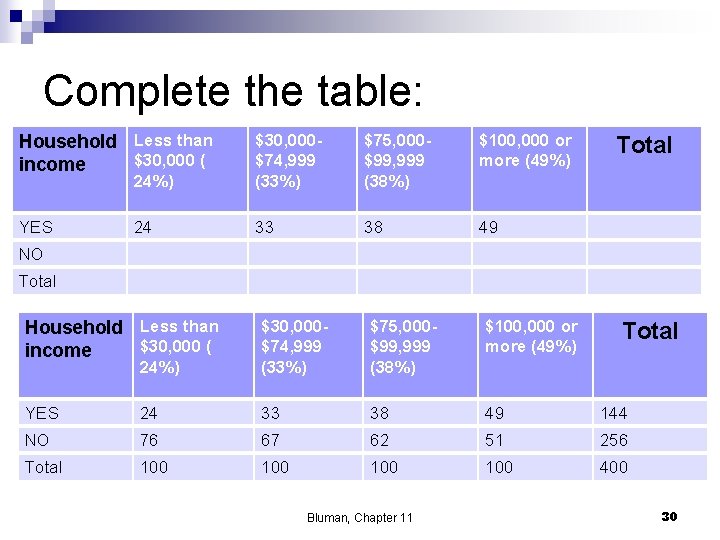

Complete the table: Household Less than $30, 000 ( income $75, 000$99, 999 (38%) $100, 000 or more (49%) 24%) $30, 000$74, 999 (33%) YES 24 33 38 49 Total NO Total Household Less than $30, 000 ( income $75, 000$99, 999 (38%) $100, 000 or more (49%) 24%) $30, 000$74, 999 (33%) YES 24 33 38 49 144 NO 76 67 62 51 256 Total 100 100 400 Bluman, Chapter 11 Total 30

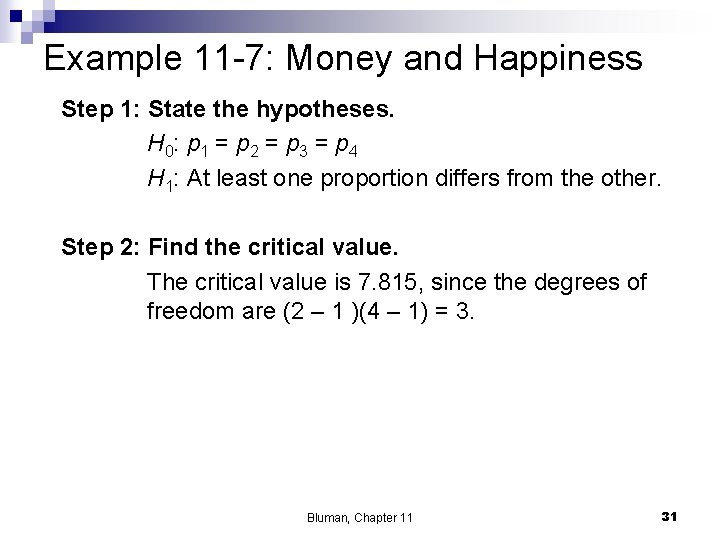

Example 11 -7: Money and Happiness Step 1: State the hypotheses. H 0: p 1 = p 2 = p 3 = p 4 H 1: At least one proportion differs from the other. Step 2: Find the critical value. The critical value is 7. 815, since the degrees of freedom are (2 – 1 )(4 – 1) = 3. Bluman, Chapter 11 31

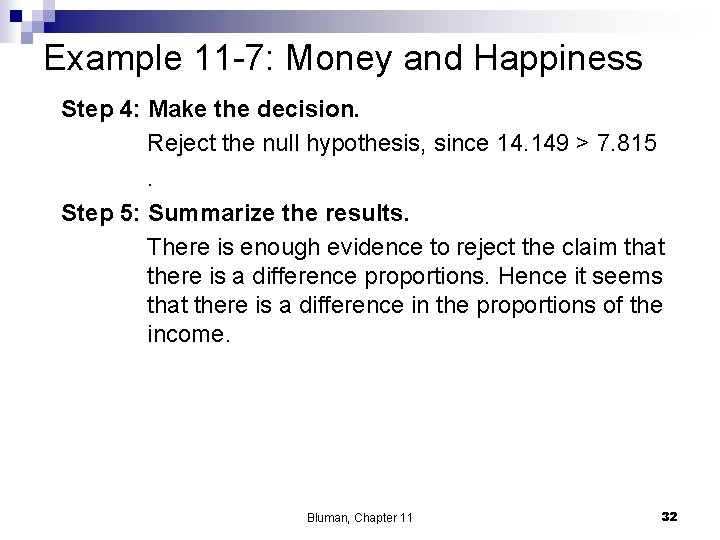

Example 11 -7: Money and Happiness Step 4: Make the decision. Reject the null hypothesis, since 14. 149 > 7. 815. Step 5: Summarize the results. There is enough evidence to reject the claim that there is a difference proportions. Hence it seems that there is a difference in the proportions of the income. Bluman, Chapter 11 32

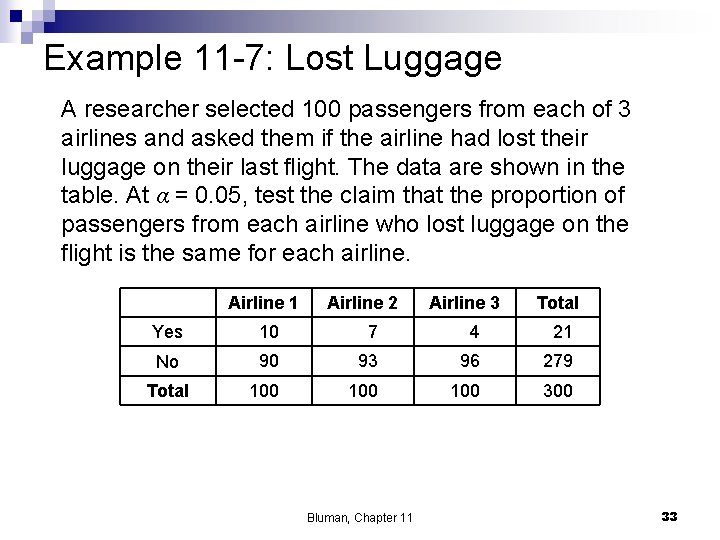

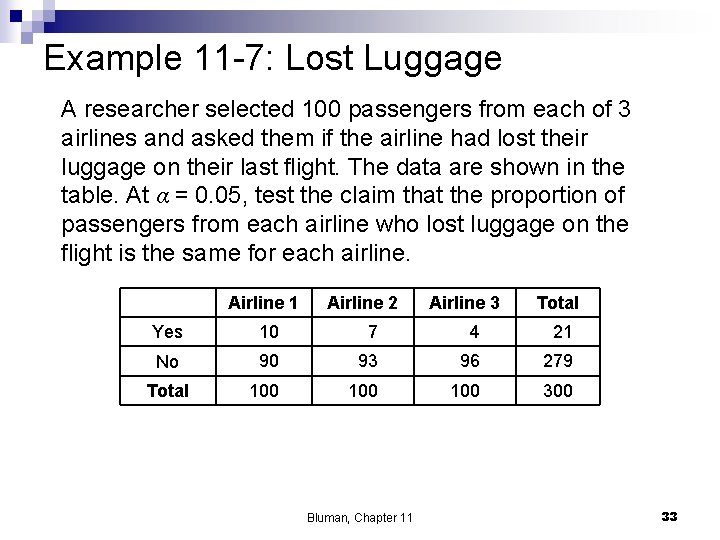

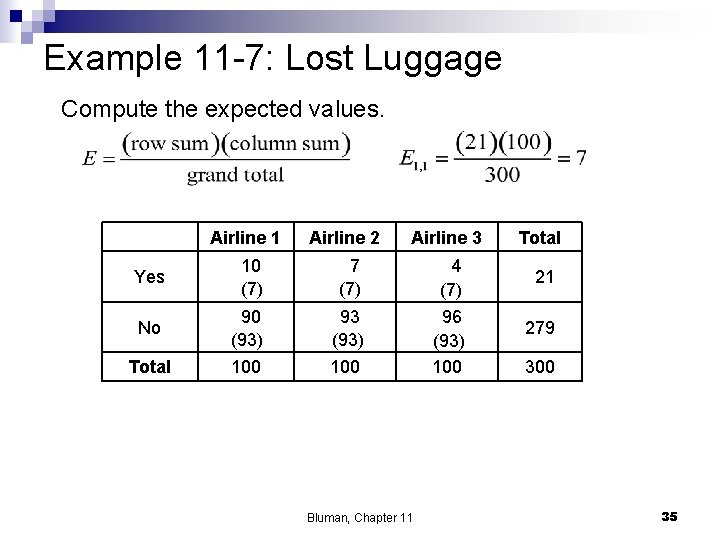

Example 11 -7: Lost Luggage A researcher selected 100 passengers from each of 3 airlines and asked them if the airline had lost their luggage on their last flight. The data are shown in the table. At α = 0. 05, test the claim that the proportion of passengers from each airline who lost luggage on the flight is the same for each airline. Airline 1 Airline 2 Airline 3 Total Yes 10 7 4 21 No 90 93 96 279 Total 100 100 300 Bluman, Chapter 11 33

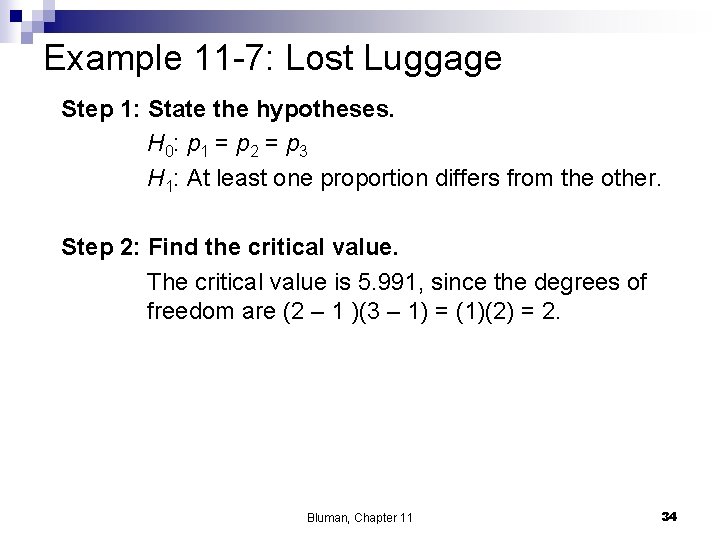

Example 11 -7: Lost Luggage Step 1: State the hypotheses. H 0: p 1 = p 2 = p 3 H 1: At least one proportion differs from the other. Step 2: Find the critical value. The critical value is 5. 991, since the degrees of freedom are (2 – 1 )(3 – 1) = (1)(2) = 2. Bluman, Chapter 11 34

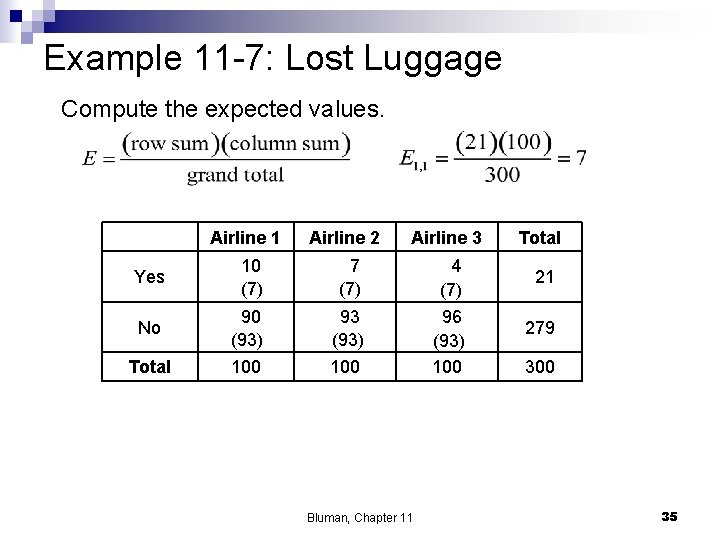

Example 11 -7: Lost Luggage Compute the expected values. Yes No Total Airline 1 Airline 2 Airline 3 Total 10 (7) 7 (7) 4 (7) 21 90 (93) 100 93 (93) 100 96 (93) 100 Bluman, Chapter 11 279 300 35

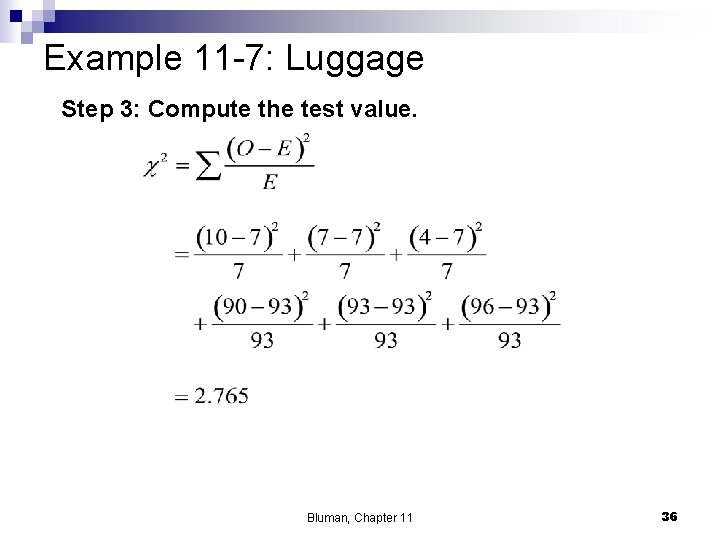

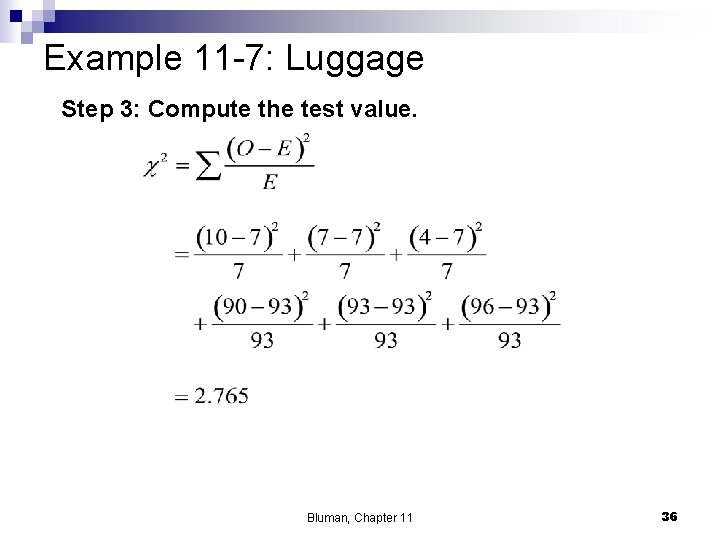

Example 11 -7: Luggage Step 3: Compute the test value. Bluman, Chapter 11 36

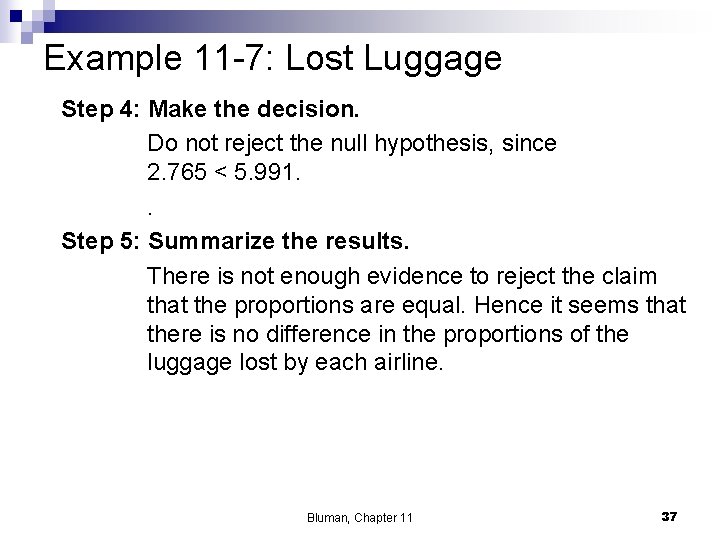

Example 11 -7: Lost Luggage Step 4: Make the decision. Do not reject the null hypothesis, since 2. 765 < 5. 991. . Step 5: Summarize the results. There is not enough evidence to reject the claim that the proportions are equal. Hence it seems that there is no difference in the proportions of the luggage lost by each airline. Bluman, Chapter 11 37

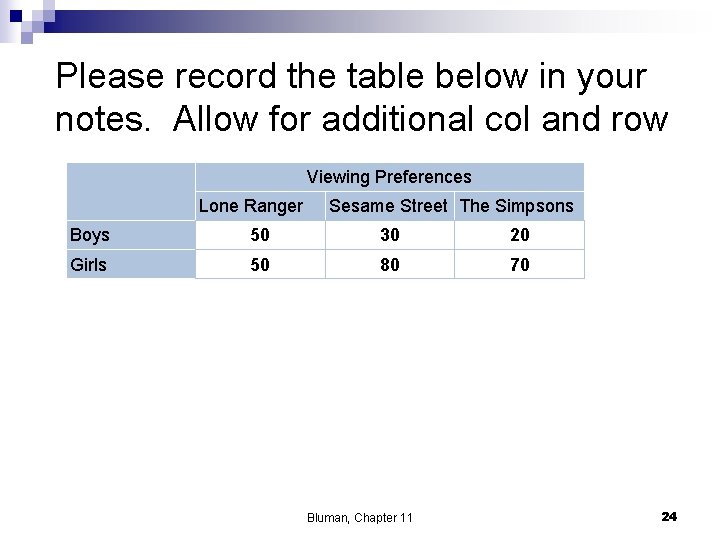

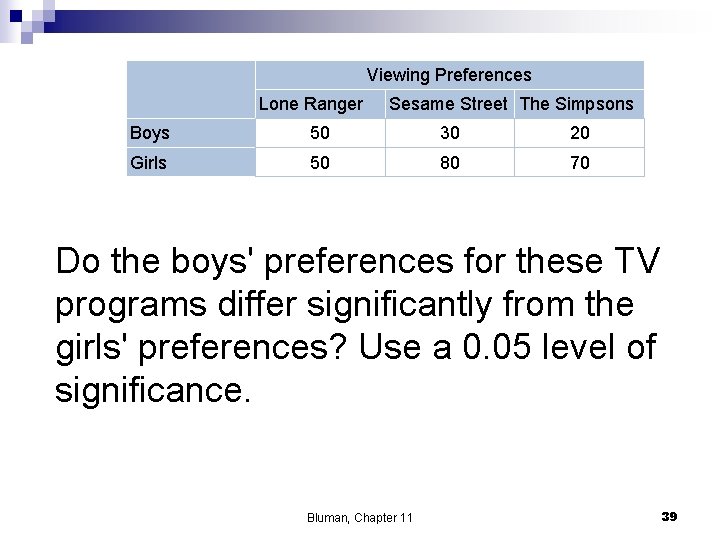

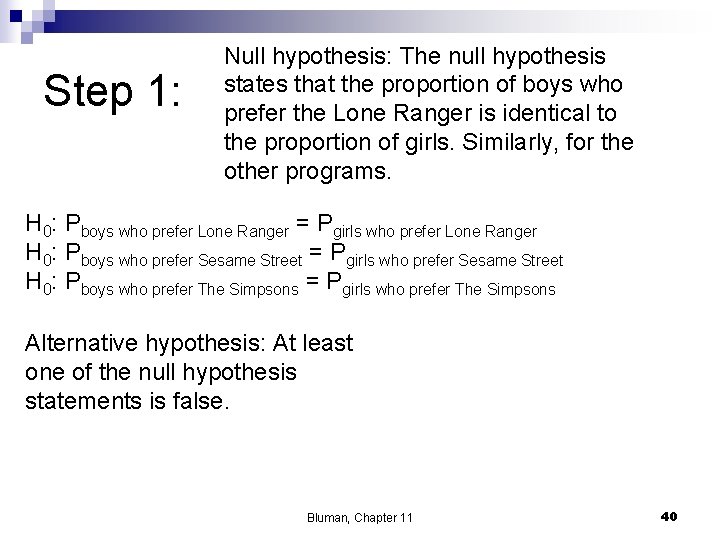

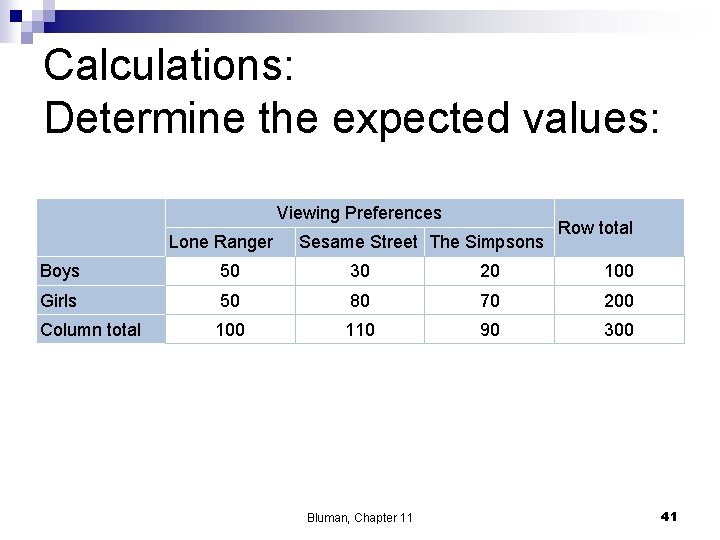

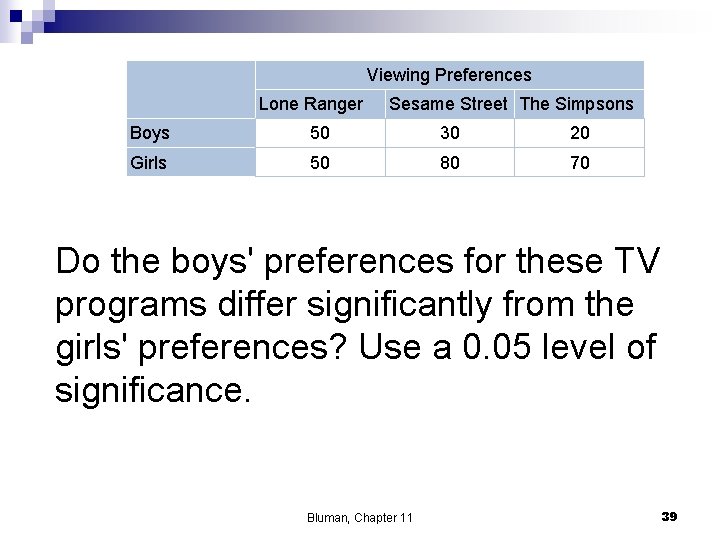

n In a study of the television viewing habits of children, a developmental psychologist selects a random sample of 300 first graders: 100 boys and 200 girls. Each child is asked which of the following TV programs they like best: The Lone Ranger, Sesame Street, or The Simpsons. Results are shown in the contingency table to follow. Bluman, Chapter 11 38

Viewing Preferences Lone Ranger Sesame Street The Simpsons Boys 50 30 20 Girls 50 80 70 Do the boys' preferences for these TV programs differ significantly from the girls' preferences? Use a 0. 05 level of significance. Bluman, Chapter 11 39

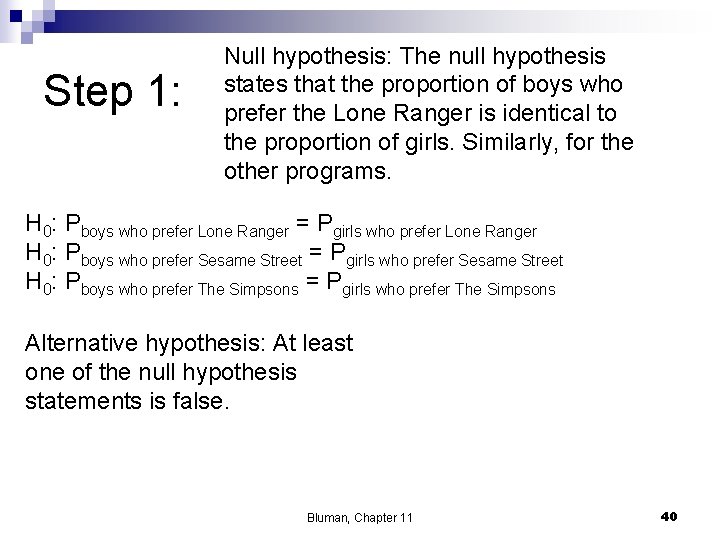

Step 1: Null hypothesis: The null hypothesis states that the proportion of boys who prefer the Lone Ranger is identical to the proportion of girls. Similarly, for the other programs. H 0: Pboys who prefer Lone Ranger = Pgirls who prefer Lone Ranger H 0: Pboys who prefer Sesame Street = Pgirls who prefer Sesame Street H 0: Pboys who prefer The Simpsons = Pgirls who prefer The Simpsons Alternative hypothesis: At least one of the null hypothesis statements is false. Bluman, Chapter 11 40

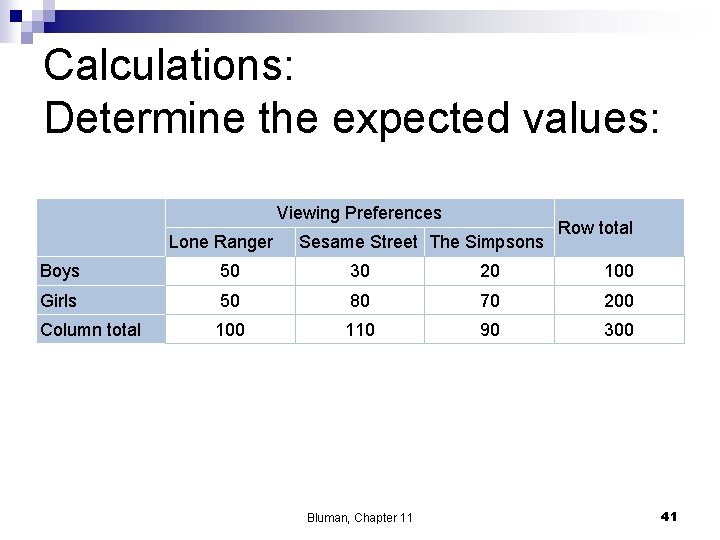

Calculations: Determine the expected values: Viewing Preferences Lone Ranger Sesame Street The Simpsons Row total Boys 50 30 20 100 Girls 50 80 70 200 Column total 100 110 90 300 Bluman, Chapter 11 41

On your own n Read section 11. 2 and all its examples. n n n Sec 11. 2 page 614 #1 -7 all; And #9, 17, 23, 27, 31 Bluman, Chapter 11 42

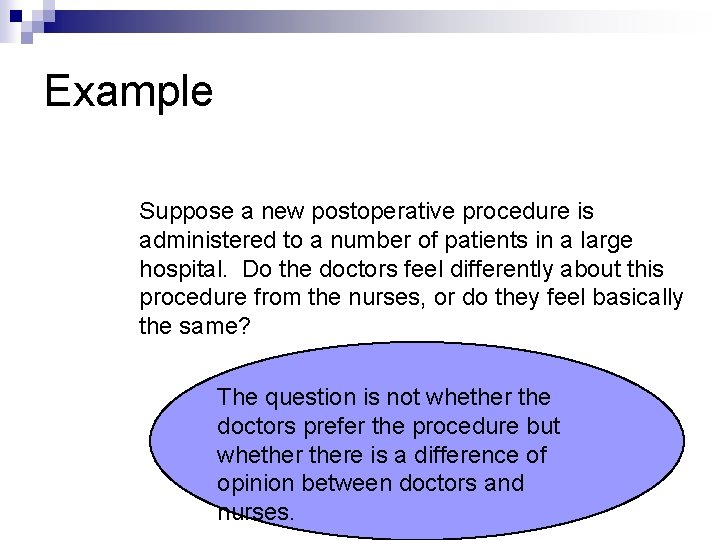

Example Suppose a new postoperative procedure is administered to a number of patients in a large hospital. Do the doctors feel differently about this procedure from the nurses, or do they feel basically the same? The question is not whether the doctors prefer the procedure but whethere is a difference of opinion between doctors and nurses.

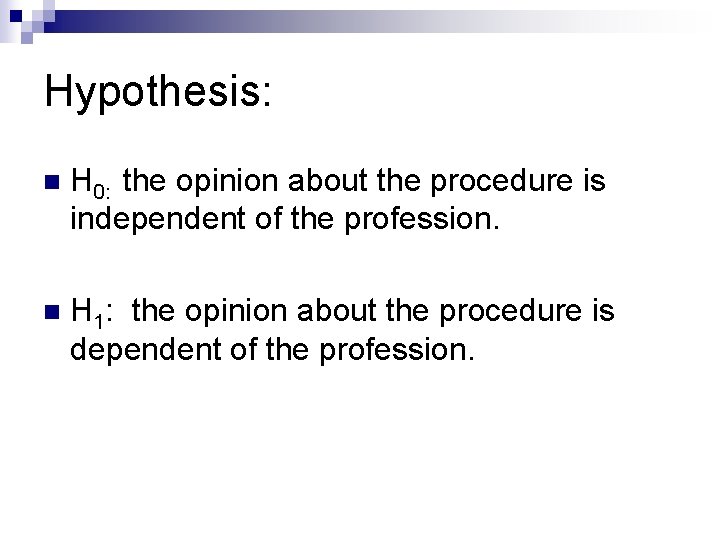

Hypothesis: n H 0: the opinion about the procedure is independent of the profession. n H 1: the opinion about the procedure is dependent of the profession.

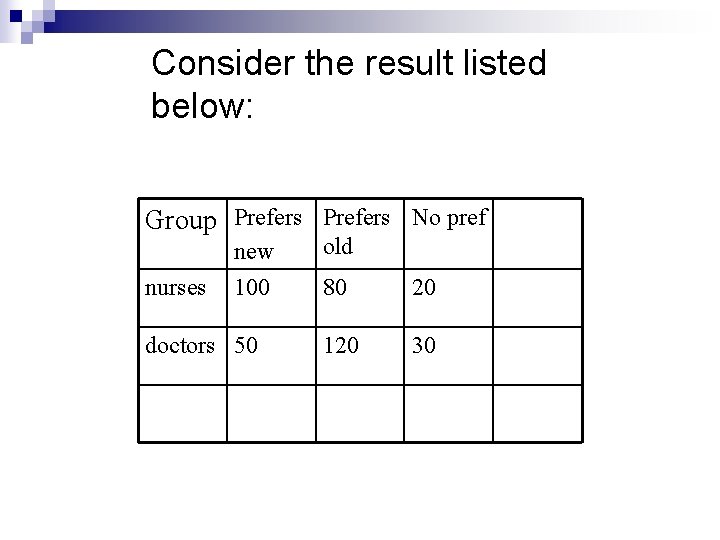

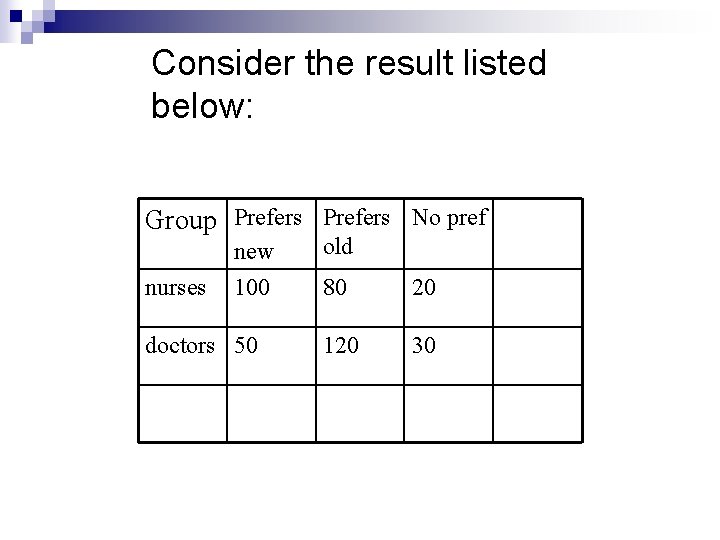

Consider the result listed below: Group Prefers No pref nurses new 100 doctors 50 old 80 20 120 30

Chapter 11 Other Chi-Square Tests Section 11 -2 Example 11 -5 Page #606 Bluman, Chapter 11 46

Hospitals and Infections Bluman, Chapter 11 47

Chapter 11 Other Chi-Square Tests Section 11 -2 618 Page #606 Bluman, Chapter 11 48