C H A P T E R 3

- Slides: 20

C H A P T E R 3 Motor Development and Recreation Deborah A. Garrahy, Ph. D Chapter 3

Outcomes • Understand the concept of developmentally appropriate practices in recreation. • Apply the model of motor development to recreation activities. • Create an activity plan using ageappropriate activities and leadership techniques.

Physical Activity Throughout Life • Current health-related concerns in the United States • NRPA initiatives – Play – Health and livability

Developmentally Appropriate Practices • Ability of the recreation leader to plan experiences for participants • Two important variables – Individual’s current ability level – Appropriateness of tasks based on the age of the group participating

Three Learning Domains • Psychomotor domain • Cognitive domain • Affective domain

Motor Development “A continuous change in motor behavior throughout the lifecycle, brought about by interaction among the requirements of the movement task, the biology of the individual, and the conditions of the environment” (Gallahue and Ozmun 2006, 5).

Gallahue’s Hourglass Model of Motor Development • Details movement skill acquisition “as a descriptive means for better understanding and conceptualizing the product of development” (Ozmun and Gallahue 2005, 344). • By understanding this model, the recreation professional has the ability to plan ageappropriate and successful movement experiences for all clients. (continued)

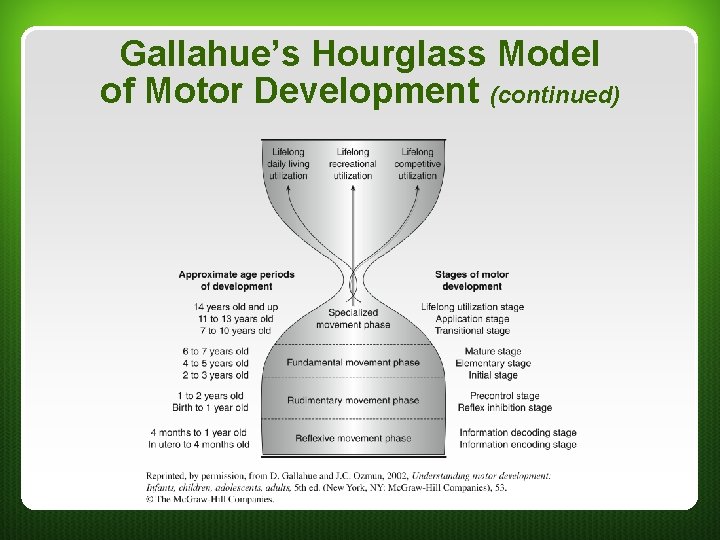

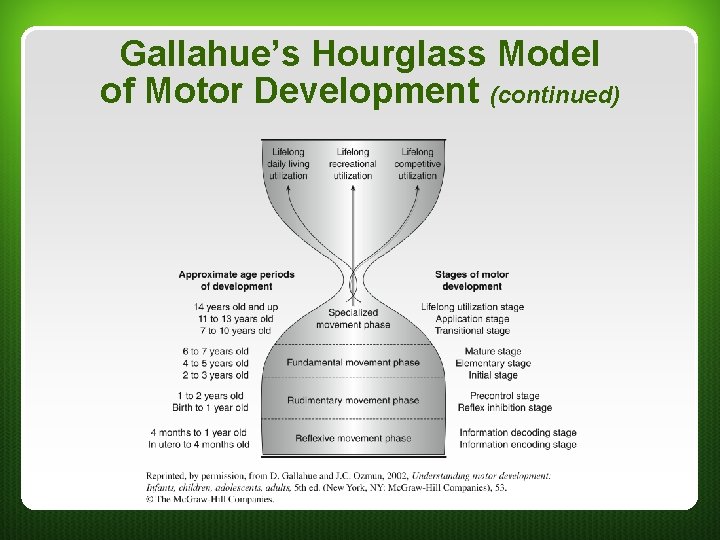

Gallahue’s Hourglass Model of Motor Development (continued)

Reflexive Movement Phase • Begins in utero and lasts through first year of life • Involuntary movements • Provides doctors and parents with vital information regarding the health (e. g. , neurological health) of the fetus or infant (continued)

Reflexive Movement Phase (continued) • Reflexive movements lead to voluntary movements • Two stages – Information encoding or gathering (in utero through 4 months of age) – Information decoding or processing (4 months through first year of age)

Rudimentary Movement Phase • From birth through 2 years of age • First forms of voluntary movement • Two stages – Reflex inhibition stage (from birth through first year of age) – Precontrol stage (from first year through second year of age) (continued)

Rudimentary Movement Phase (continued) • Stability movements include gaining and maintaining control of the head, neck, and torso. • Locomotor movements include creeping and crawling. • Manipulative movements include reaching, grasping, and releasing objects.

Fundamental Movement Phase • From 2 years through 7 years of age • Similar to learning ABCs and basic mathematical functions • Foundational movement skills needed for lifelong physical activity • Experience many forms of movement through play, cooperative activities, and low -level games (continued)

Fundamental Movement Phase (continued) • Initial stage (2 -3 years old) – First attempts at the movement – Major pieces of the movement are missing • Elementary stage (4 -5 years old) – Improved coordination and control – Pieces of the movement still missing – Many adults function at the elementary stage (continued)

Fundamental Movement Phase (continued) • Mature stage (6 -7 years old) – Movement is coordinated and efficient – Biomechanically correct • Three categories of movement: stability, locomotor, and manipulative (continued)

Fundamental Movement Phase (continued) • Stability movement: gaining and maintaining static balance (stationary) and dynamic balance (in motion) • Locomotor movement: movement about an area (walking, hopping, sliding) • Manipulative movement: applying force to an object (throwing a ball) or receiving force from an object (catching a beanbag)

Specialized Movement Phase • From age seven throughout life • Applying learned movement skills in more complex settings (community recreation programs, youth sport leagues) • Transitional stage (7 -10 years old) – First attempts at refining mature movement patterns and exploring combinations of movements (continued)

Specialized Movement Phase (continued) • Application stage (11 -13 years old) – Developing higher levels of proficiency through practice • Lifelong utilization stage (14+ years old) – Final stage in the phase; lasts throughout adulthood

Applying Developmentally Appropriate Practices in Recreation • Recreation leaders must know the movement abilities the participant needs as prerequisites for successful participation. • When leading activities or coaching a sport, it is imperative to have an activity plan. (continued)

Applying Developmentally Appropriate Practices in Recreation (continued) • Activity planning requires much thought about what will occur in the gym or on the playground or field. • Very few leaders are skilled enough to effectively lead a group in developmentally appropriate activities and leadership techniques without an activity plan.