Business Forecasting Chapter 4 Data Collection and Analysis

Business Forecasting Chapter 4 Data Collection and Analysis in Forecasting

Chapter Topics n Preliminary Adjustments to Data n Data Transformation n Patterns in Time Series Data n The Classical Decomposition Method

Preliminary Data Adjustments n Trading Day Adjustments n Price Change Adjustments n Population Change Adjustments

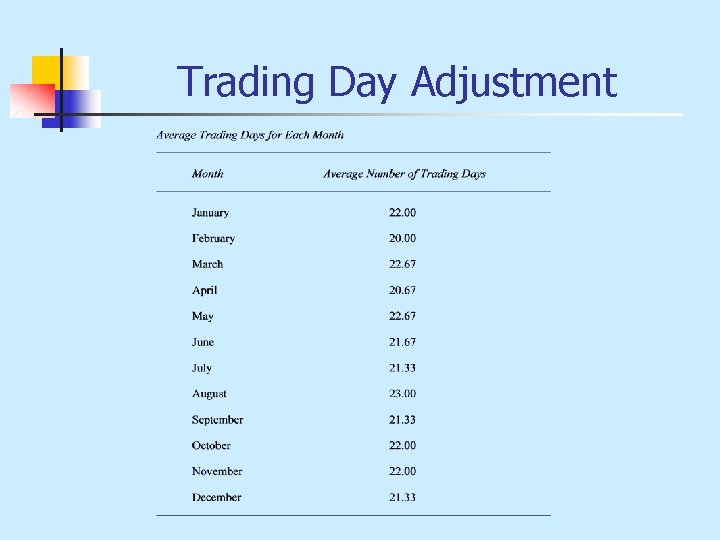

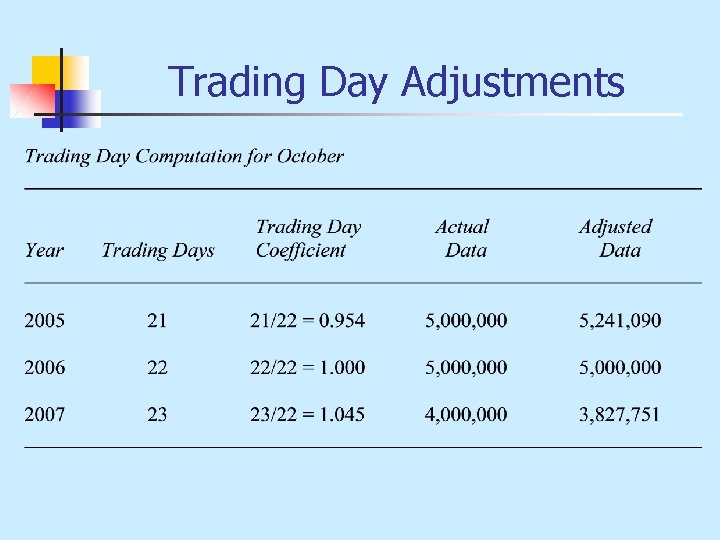

Trading Day Adjustments Yr J F M A M J J A S O N D 05 21 20 23 21 22 22 21 23 22 21 22 22 06 22 20 23 22 21 23 22 22 22 21 07 23 20 22 21 23 21 22 23 20 23 22 21

Trading Day Adjustment

Trading Day Adjustments

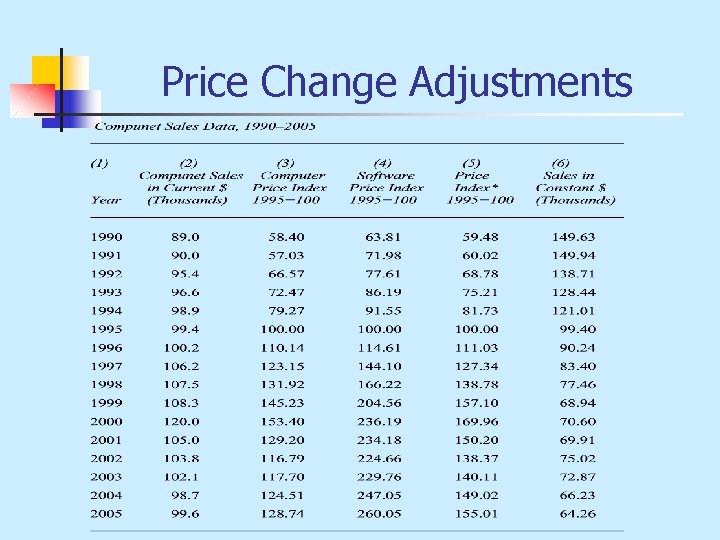

Price Change Adjustments

Price Change Adjustments n Having computed the price index, we are now able to deflate the sales revenue with the weighted price index in the following way:

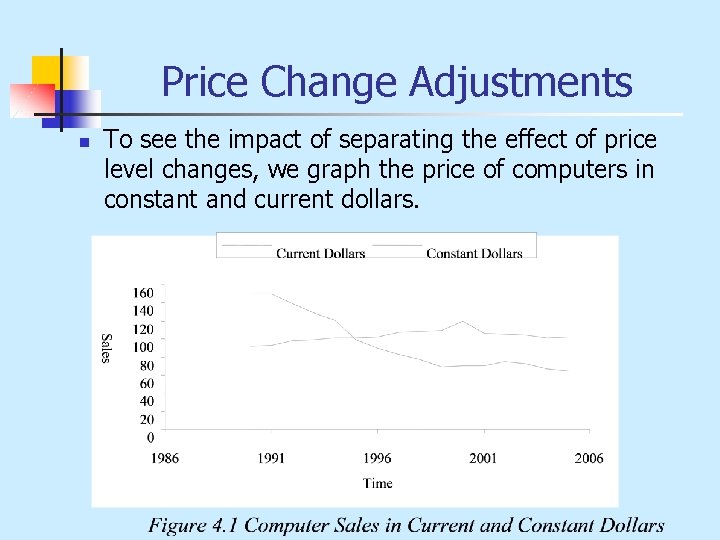

Price Change Adjustments n To see the impact of separating the effect of price level changes, we graph the price of computers in constant and current dollars.

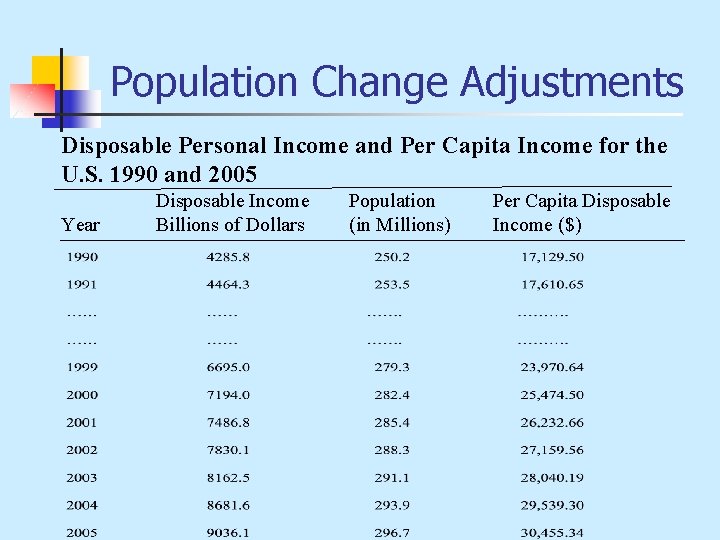

Population Change Adjustments Disposable Personal Income and Per Capita Income for the U. S. 1990 and 2005 Year Disposable Income Billions of Dollars Population (in Millions) Per Capita Disposable Income ($)

Data Transformation n Most appropriate remedial measure for variance heterogeneity. Original data are converted into a new scale, resulting in a new data set that is expected to satisfy the condition of homogeneity of variance. Several transformation techniques are available.

Data Transformation n Linear Transformation: n n An important assumption in using the regression model forecasting is that the pattern of observation is linear. Obviously, there are many situations in which this is not a valid assumption. n For example, if we were forecasting monthly sales and it was believed that those sales varied according to the season of the year, then the assumption of linearity would not hold.

Linear Transformation n n A forecasting equation may be of the form: The above could easily be transformed into a linear form for estimation purposes:

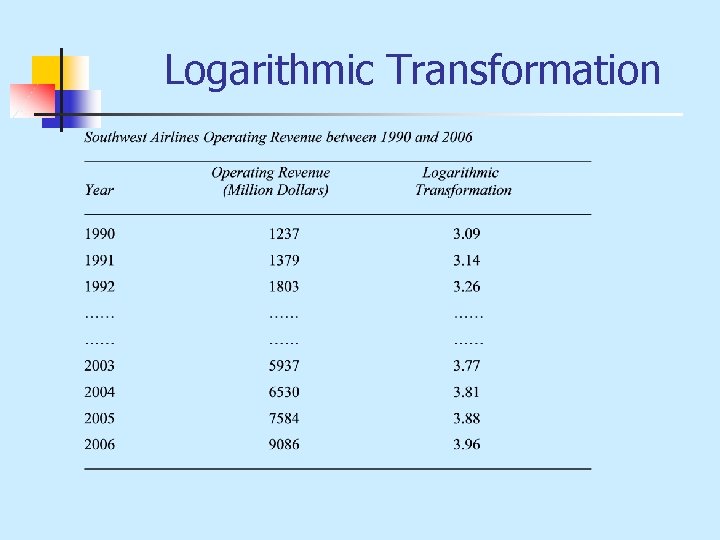

Logarithmic Transformation

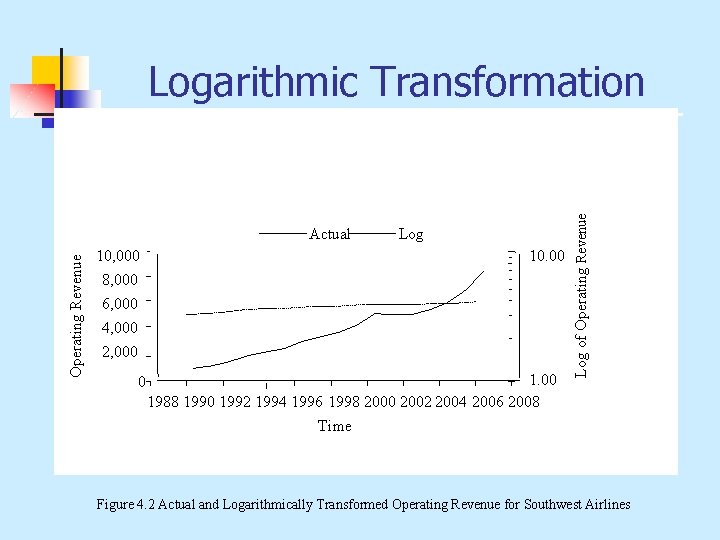

Operating Revenue Actual 10, 000 Log 10. 00 8, 000 6, 000 4, 000 2, 000 0 1. 00 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 Log of Operating Revenue Logarithmic Transformation Time Figure 4. 2 Actual and Logarithmically Transformed Operating Revenue for Southwest Airlines

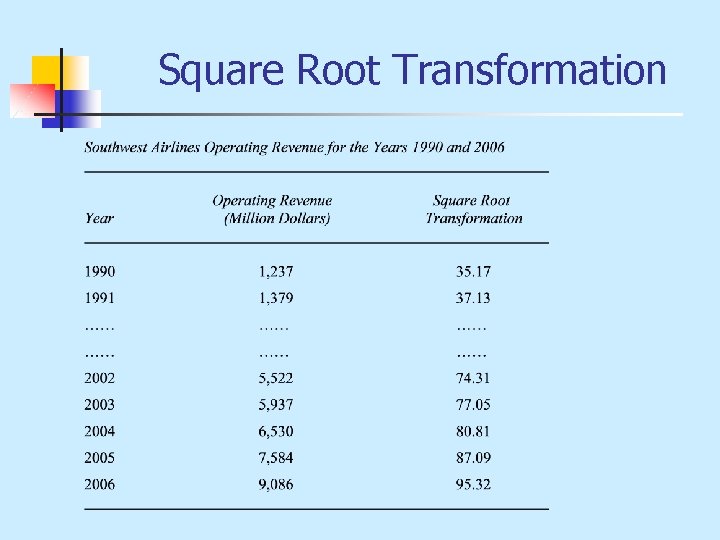

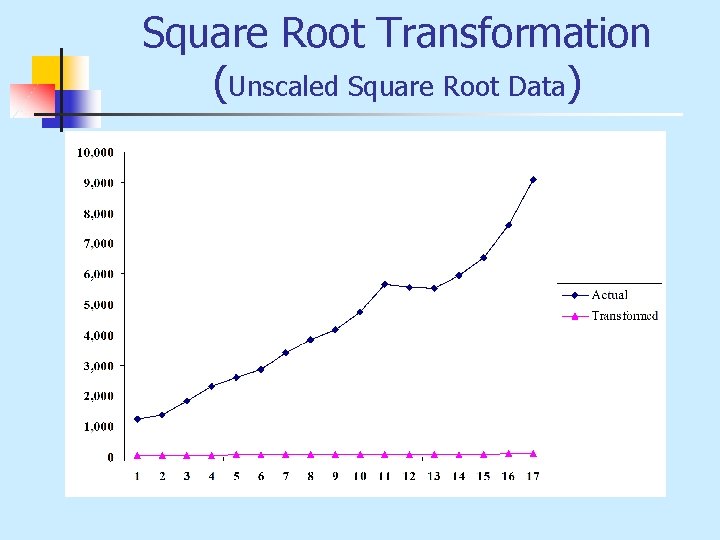

Square Root Transformation

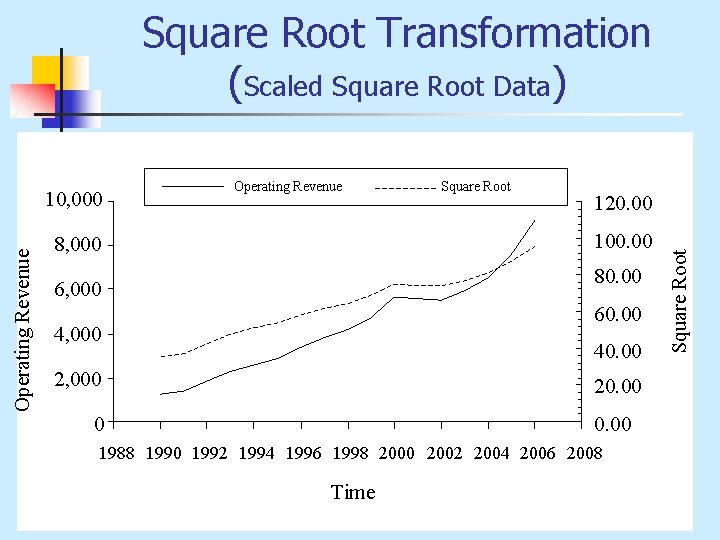

Square Root Transformation (Scaled Square Root Data) Square Root 120. 00 100. 00 8, 000 80. 00 6, 000 60. 00 4, 000 40. 00 2, 000 20. 00 0 0. 00 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 Time Square Root Operating Revenue 10, 000 Operating Revenue

Square Root Transformation (Unscaled Square Root Data)

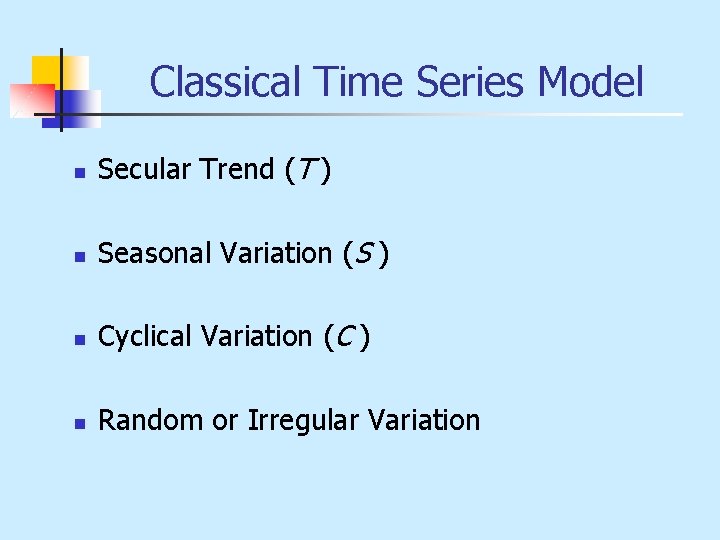

Classical Time Series Model n Secular Trend (T ) n Seasonal Variation (S ) n Cyclical Variation (C ) n Random or Irregular Variation

Trend n Linear Trend n Non-linear Trend

Trend n Computing the Linear Trend n The Freehand Method n The Semi-average Method n The Least Squares Method

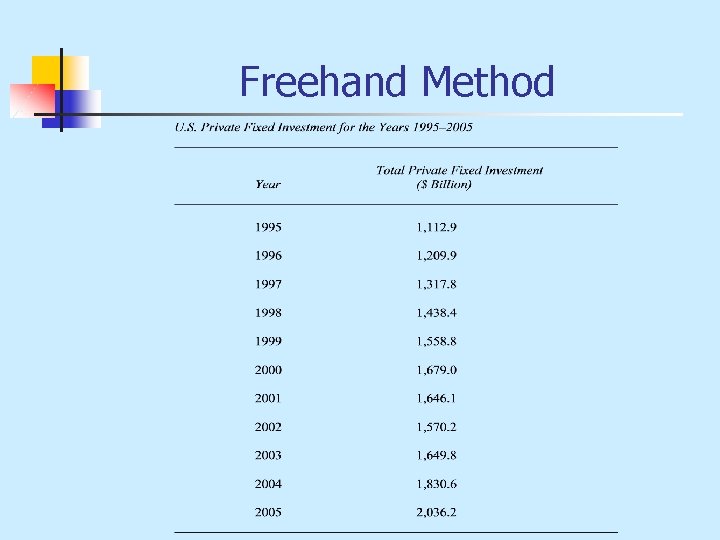

Freehand Method

Freehand Method Since a linear trend by this method is simply an approximation of a straight line equation, we have to determine the intercept and the slope of the line. Based on our data, we have:

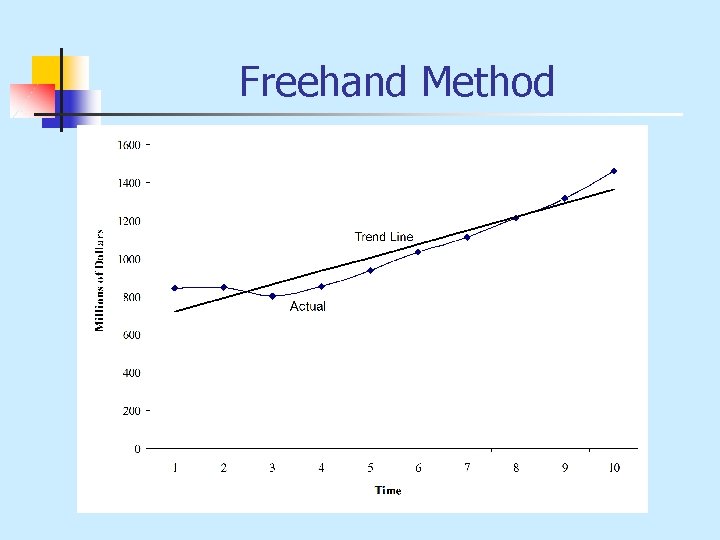

Freehand Method

Freehand Method n Now we can use this equation to make a forecast of the trend. For example, the forecast for 2006 would be:

Freehand Method n n n Based on your understanding, what are the pitfalls of using the freehand method? Simple method but not objective. Why not objective?

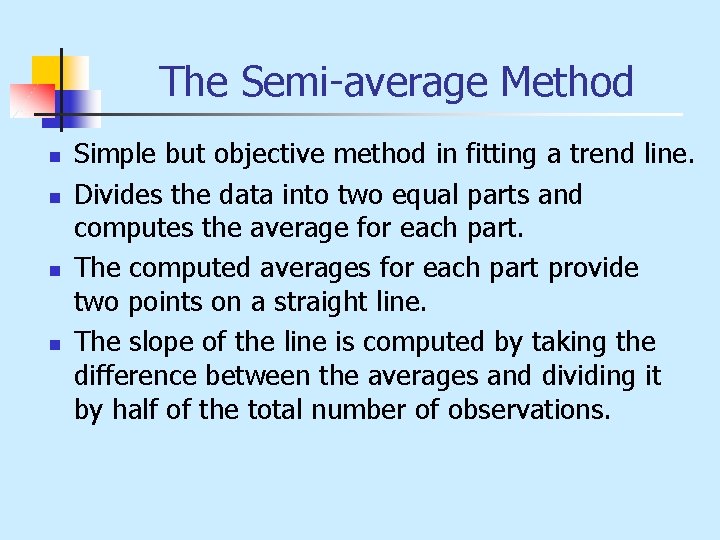

The Semi-average Method n n Simple but objective method in fitting a trend line. Divides the data into two equal parts and computes the average for each part. The computed averages for each part provide two points on a straight line. The slope of the line is computed by taking the difference between the averages and dividing it by half of the total number of observations.

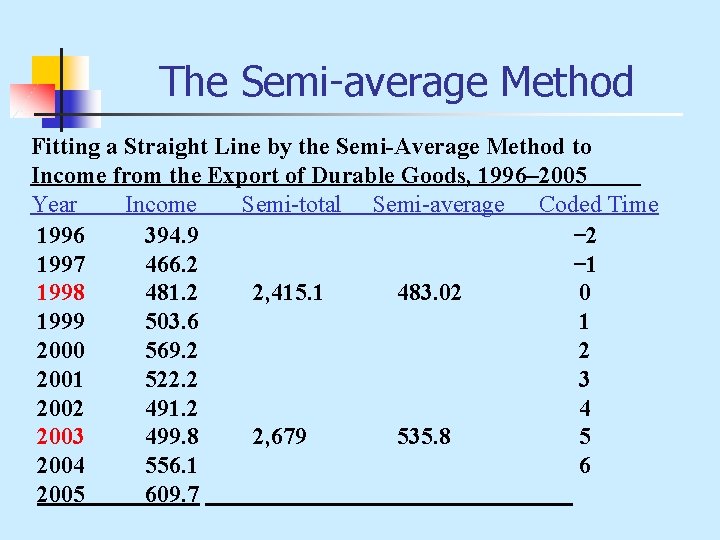

The Semi-average Method Fitting a Straight Line by the Semi-Average Method to Income from the Export of Durable Goods, 1996– 2005 Year Income Semi-total Semi-average Coded Time 1996 394. 9 − 2 1997 466. 2 − 1 1998 481. 2 2, 415. 1 483. 02 0 1999 503. 6 1 2000 569. 2 2 2001 522. 2 3 2002 491. 2 4 2003 499. 8 2, 679 535. 8 5 2004 556. 1 6 2005 609. 7

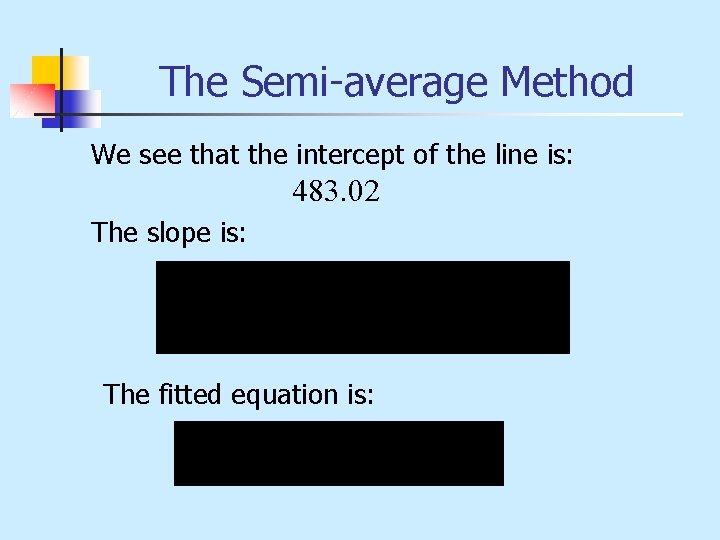

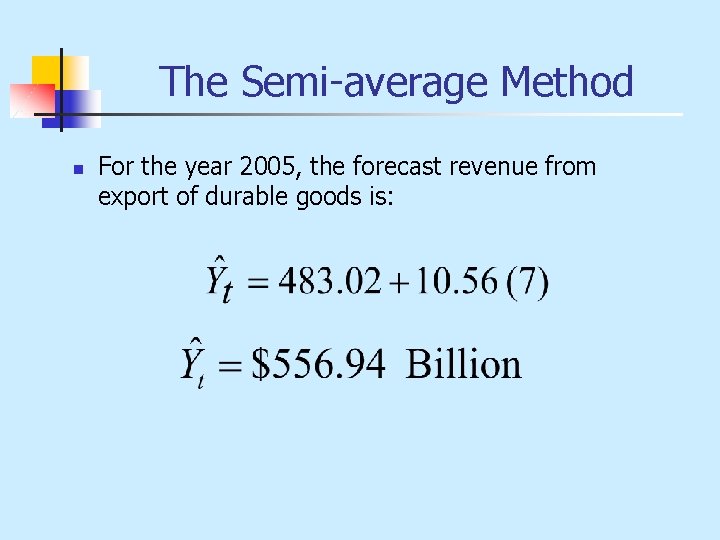

The Semi-average Method We see that the intercept of the line is: 483. 02 The slope is: The fitted equation is:

The Semi-average Method n For the year 2005, the forecast revenue from export of durable goods is:

The Least Squares Method n n Provides the best method of fitting a trend. The intercept and the slope are computed as follows:

The Least Squares Method n Using the data from the previous example, we have:

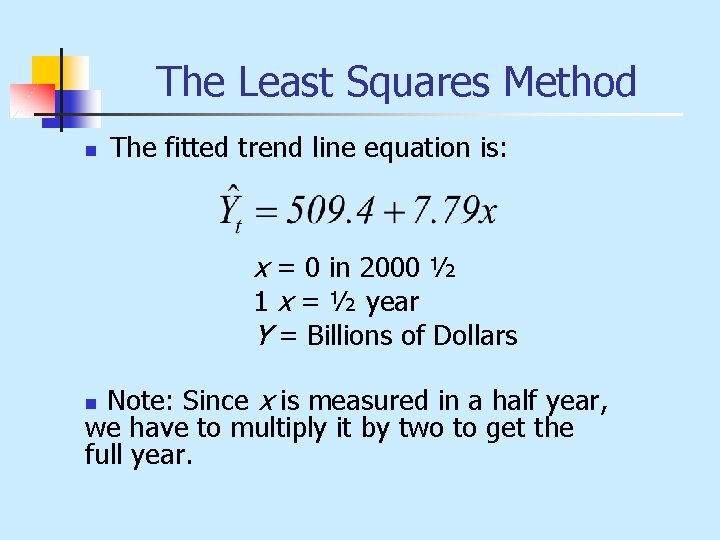

The Least Squares Method n The fitted trend line equation is: x = 0 in 2000 ½ 1 x = ½ year Y = Billions of Dollars Note: Since x is measured in a half year, we have to multiply it by two to get the full year. n

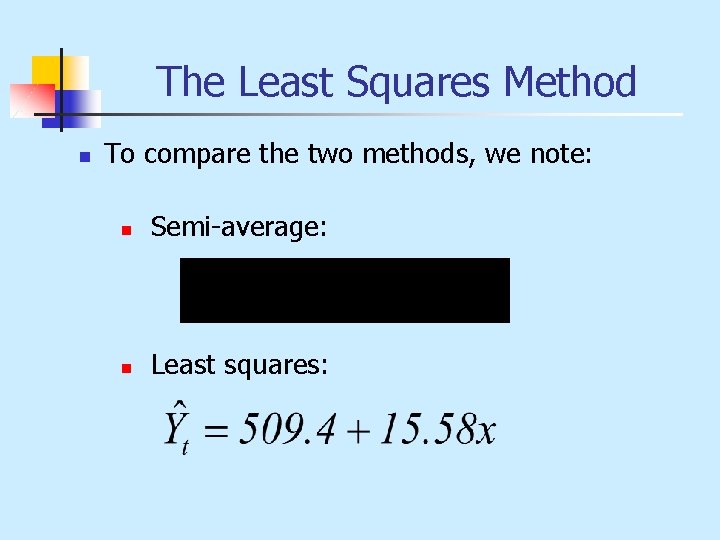

The Least Squares Method n To compare the two methods, we note: n Semi-average: n Least squares:

Nonlinear Trend n n In many business and economic environments we observe that the time series does not follow a constant rate of increase or decrease, but follows an increasing or decreasing pattern. Whenever there is dramatic change in production technology, we expect the trend line not to follow a constant linear pattern.

Nonlinear Trend n n A polynomial function best exemplifies business conditions. A second-degree parabola provides a good historical description of an increase or decrease per time period.

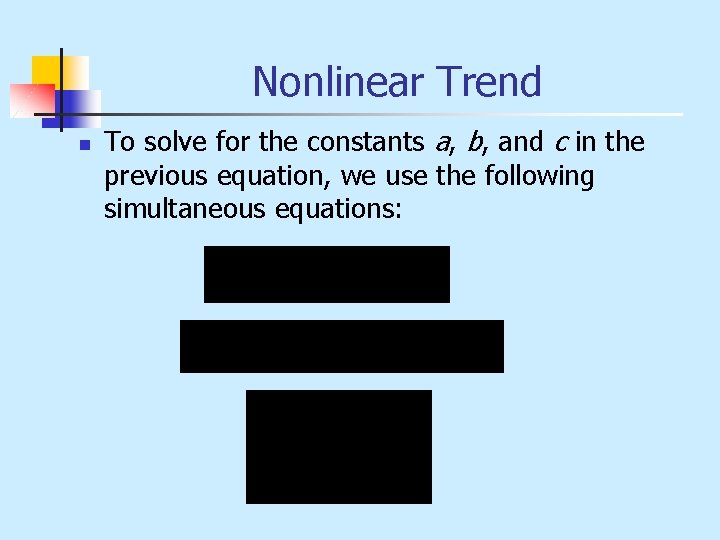

Nonlinear Trend n To solve for the constants a, b, and c in the previous equation, we use the following simultaneous equations:

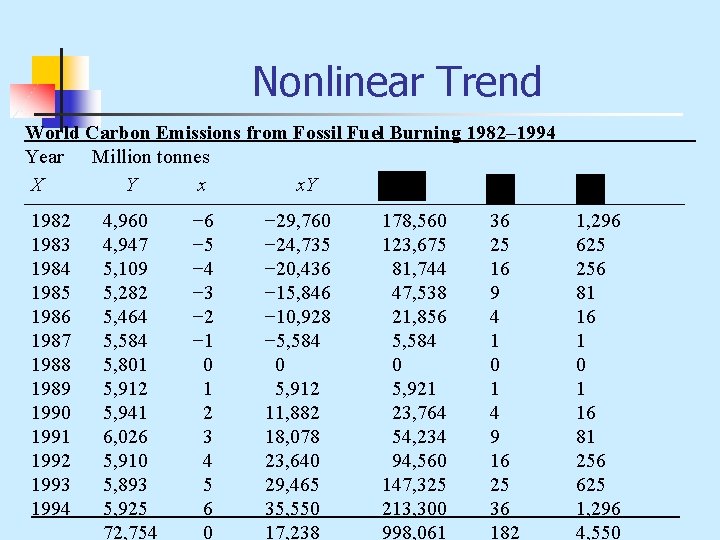

Nonlinear Trend World Carbon Emissions from Fossil Fuel Burning 1982– 1994 Year Million tonnes X Y x x. Y 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 4, 960 4, 947 5, 109 5, 282 5, 464 5, 584 5, 801 5, 912 5, 941 6, 026 5, 910 5, 893 5, 925 72, 754 − 6 − 5 − 4 − 3 − 2 − 1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 0 − 29, 760 − 24, 735 − 20, 436 − 15, 846 − 10, 928 − 5, 584 0 5, 912 11, 882 18, 078 23, 640 29, 465 35, 550 17, 238 178, 560 123, 675 81, 744 47, 538 21, 856 5, 584 0 5, 921 23, 764 54, 234 94, 560 147, 325 213, 300 998, 061 36 25 16 9 4 1 0 1 4 9 16 25 36 182 1, 296 625 256 81 16 1 0 1 16 81 256 625 1, 296 4, 550

Nonlinear Trend n The data from the table is used to compute the following: x = 0 in 1988 1 x = one year Y = million tonnes

Logarithmic Trend n n n When we wish to fit a trend line to percentage rates of change, we use the logarithmic trend line. This is more prevalent when dealing with economic growth in an environment. The logarithmic trend equation is:

Logarithmic Trend n The least squares trend is computed as:

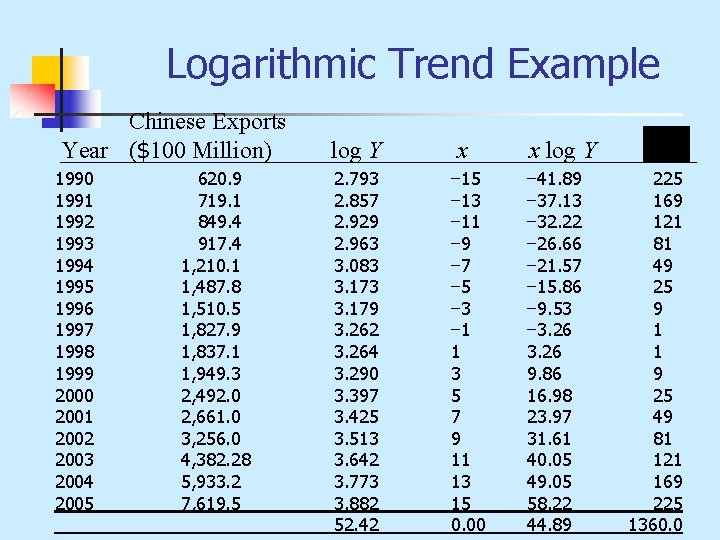

Logarithmic Trend Example Chinese Exports Year ($100 Million) 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 620. 9 719. 1 849. 4 917. 4 1, 210. 1 1, 487. 8 1, 510. 5 1, 827. 9 1, 837. 1 1, 949. 3 2, 492. 0 2, 661. 0 3, 256. 0 4, 382. 28 5, 933. 2 7, 619. 5 log Y 2. 793 2. 857 2. 929 2. 963 3. 083 3. 179 3. 262 3. 264 3. 290 3. 397 3. 425 3. 513 3. 642 3. 773 3. 882 52. 42 x − 15 − 13 − 11 − 9 − 7 − 5 − 3 − 1 1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 0. 00 x log Y − 41. 89 − 37. 13 − 32. 22 − 26. 66 − 21. 57 − 15. 86 − 9. 53 − 3. 26 9. 86 16. 98 23. 97 31. 61 40. 05 49. 05 58. 22 44. 89 225 169 121 81 49 25 9 1 1 9 25 49 81 121 169 225 1360. 0

Logarithmic Trend Example (continued)

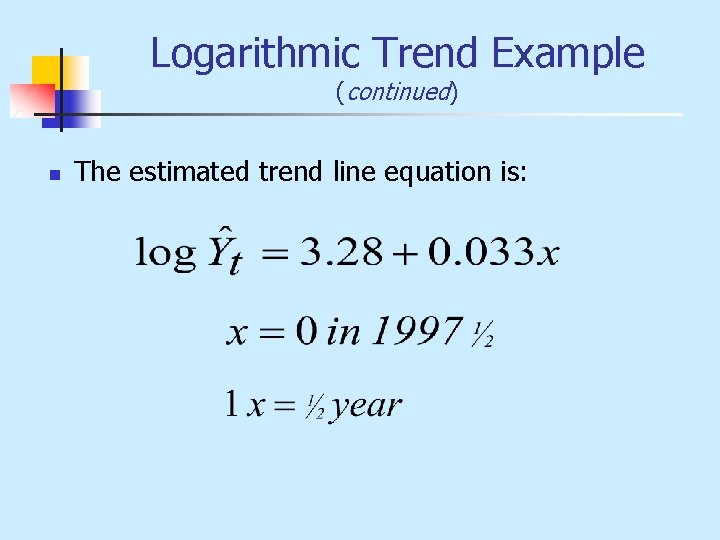

Logarithmic Trend Example (continued) n The estimated trend line equation is:

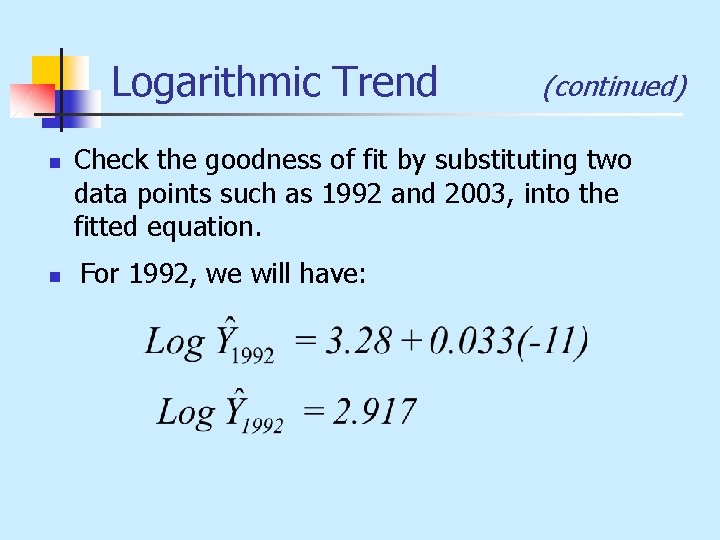

Logarithmic Trend n n (continued) Check the goodness of fit by substituting two data points such as 1992 and 2003, into the fitted equation. For 1992, we will have:

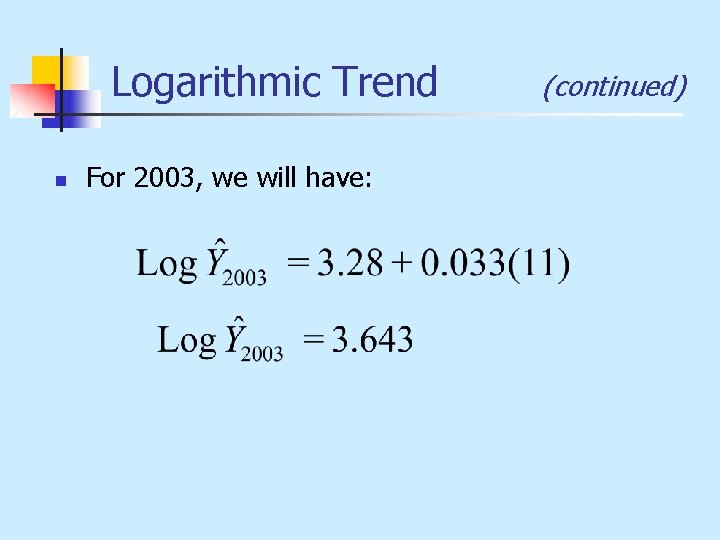

Logarithmic Trend n For 2003, we will have: (continued)

Logarithmic Trend n n Interpretation of the estimated trend line would be similar to a linear trend. However, before we can interpret the estimated values, we have to convert the log values into actual values of the data points. This is done by taking the antilog.

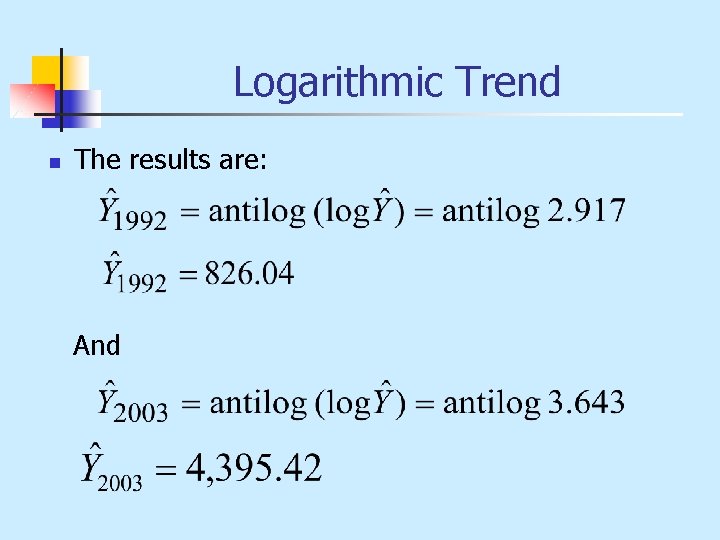

Logarithmic Trend n The results are: And

Logarithmic Trend n To determine the rate of change or the slope of the line we have: R = antilog 0. 033 = 1. 079 Since the rate of change (r) was defined as R − 1, then r = 1. 079 − 1 = 0. 079 r = 7. 9 percent per half-year Therefore the growth rate is 15. 8% or 16% per year.

Other Approaches to Trend Line n Two more sophisticated methods of determining whethere is a trend in the data: n n n Differencing Autocorrelation (Box–Jenkins Methodology) Allows the analyst to see whether a linear equation, a second-degree polynomial, or a higher-degree equation should be used to determine a trend.

Differencing n First Difference n Second Difference

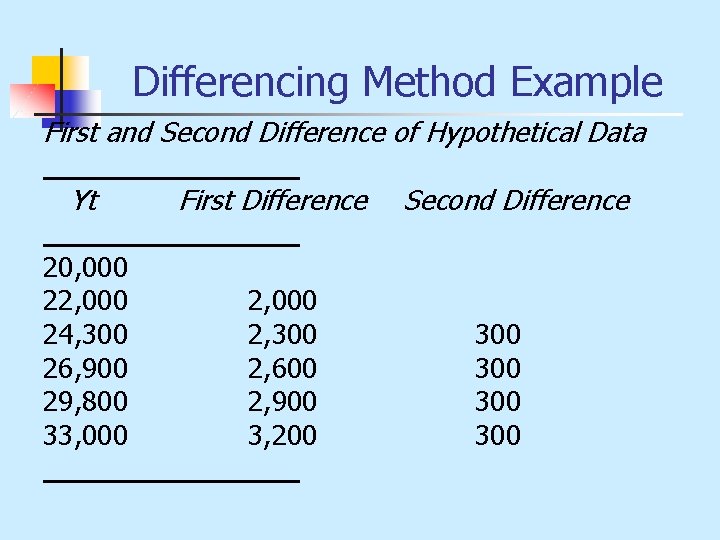

Differencing Method Example First and Second Difference of Hypothetical Data Yt 20, 000 22, 000 24, 300 26, 900 29, 800 33, 000 First Difference 2, 000 2, 300 2, 600 2, 900 3, 200 Second Difference 300 300

Seasonal Analysis n n Seasonal variation is defined as a predictable and repetitive movement observed around a trend line within a period of 1 year or less. There are several reasons for measuring seasonal variations. n When analyzing the data from a time series, it is important to be able to know how much of the variation in the data is due to the seasonal factors.

Seasonal Variation n n (Continued) We may use seasonal variation patterns in making projections or forecasts of a shortterm nature. By eliminating the seasonal variation from a time series, we may discover the cyclical pattern of the time series.

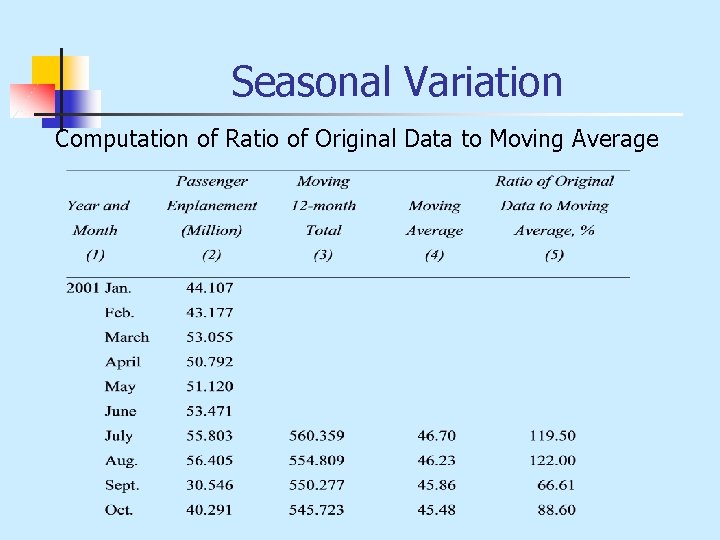

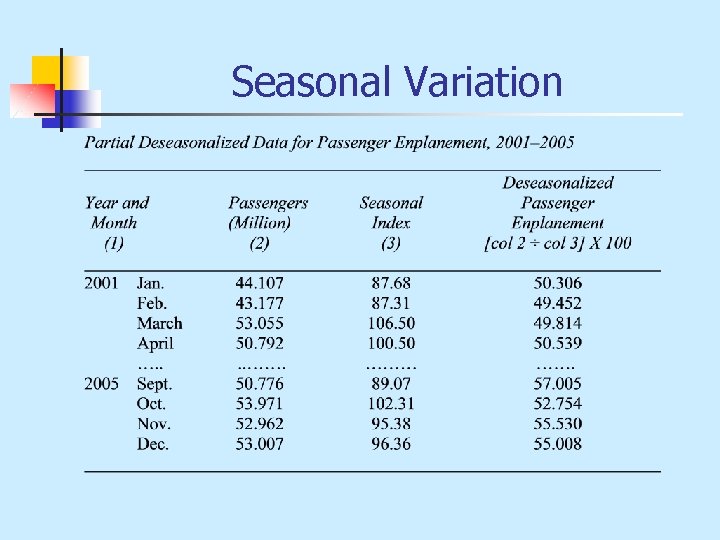

Seasonal Variation Computation of Ratio of Original Data to Moving Average

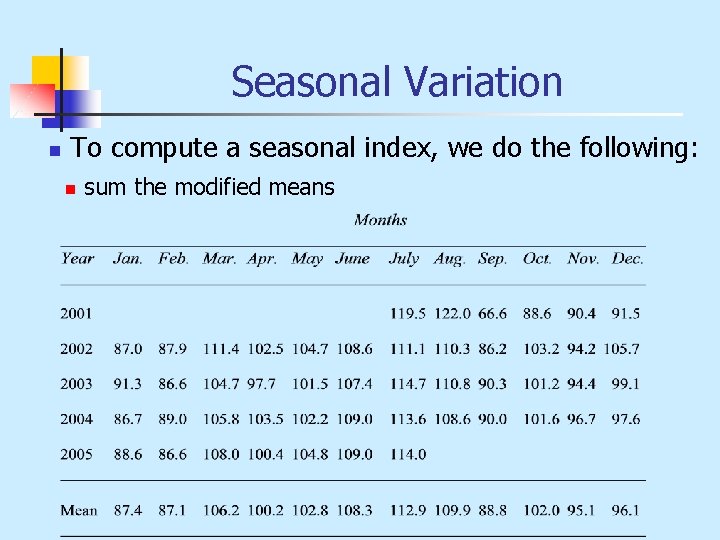

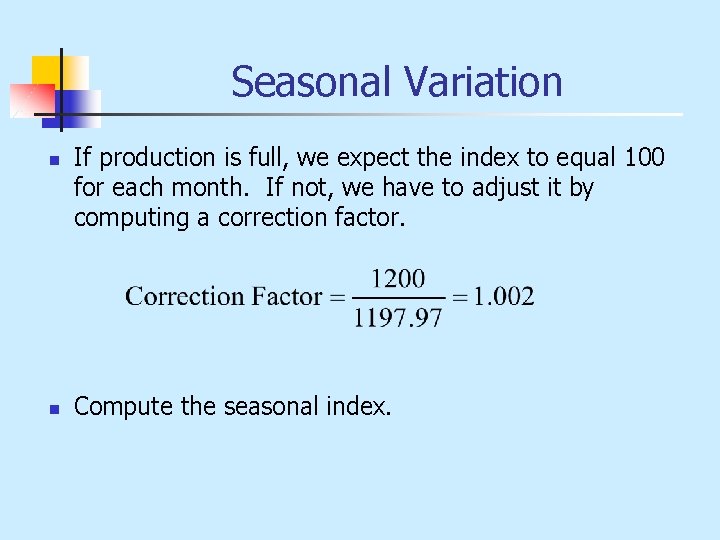

Seasonal Variation n To compute a seasonal index, we do the following: n sum the modified means

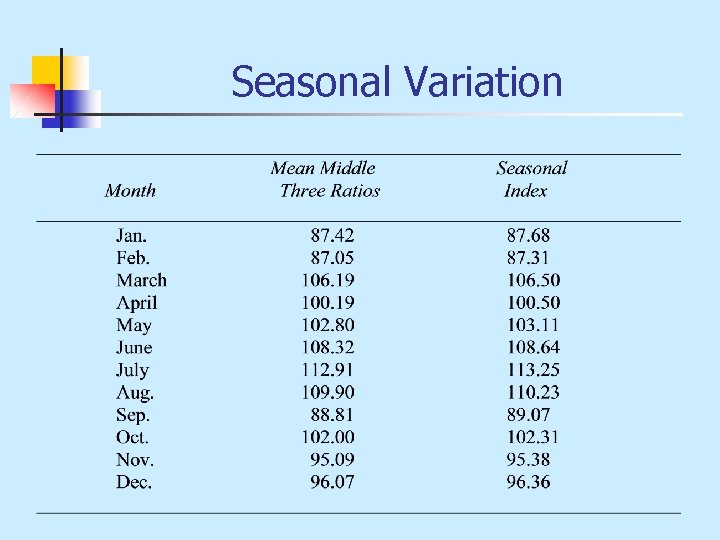

Seasonal Variation

Seasonal Variation n n If production is full, we expect the index to equal 100 for each month. If not, we have to adjust it by computing a correction factor. Compute the seasonal index.

Seasonal Variation

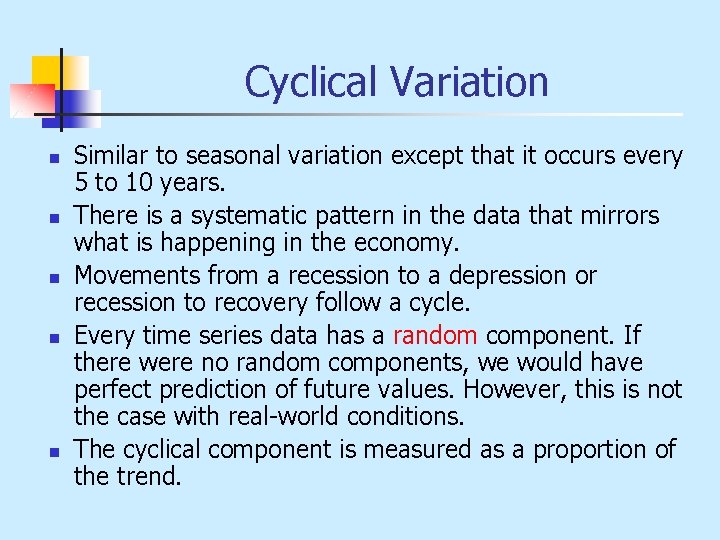

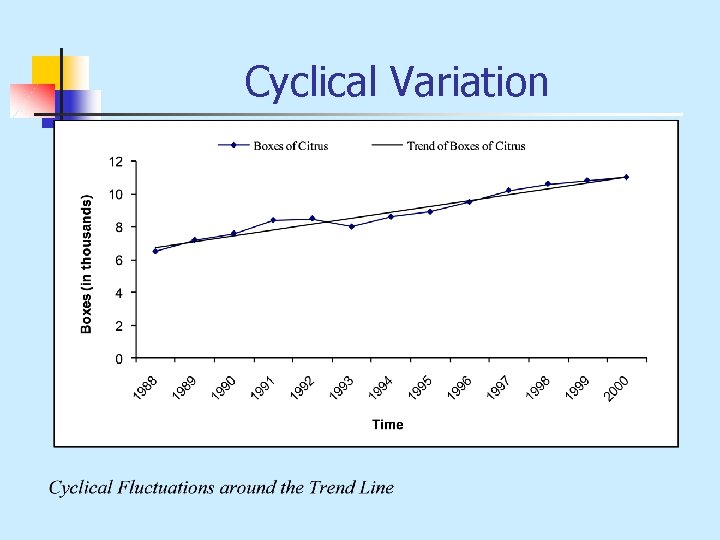

Cyclical Variation n n Similar to seasonal variation except that it occurs every 5 to 10 years. There is a systematic pattern in the data that mirrors what is happening in the economy. Movements from a recession to a depression or recession to recovery follow a cycle. Every time series data has a random component. If there were no random components, we would have perfect prediction of future values. However, this is not the case with real-world conditions. The cyclical component is measured as a proportion of the trend.

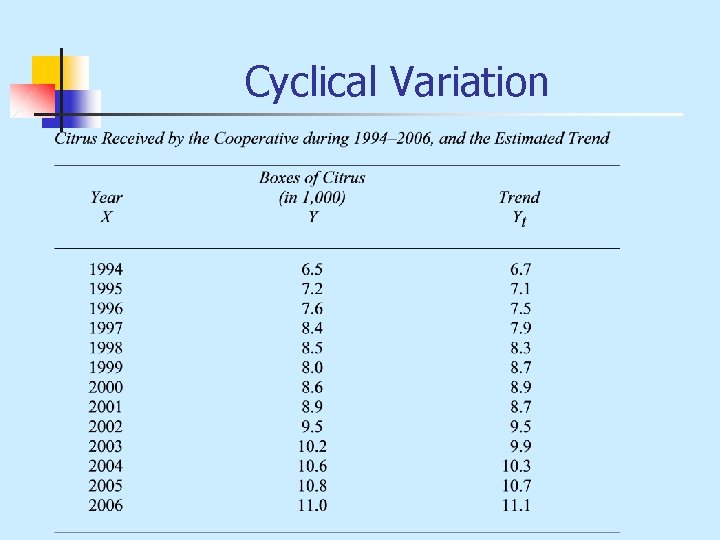

Cyclical Variation

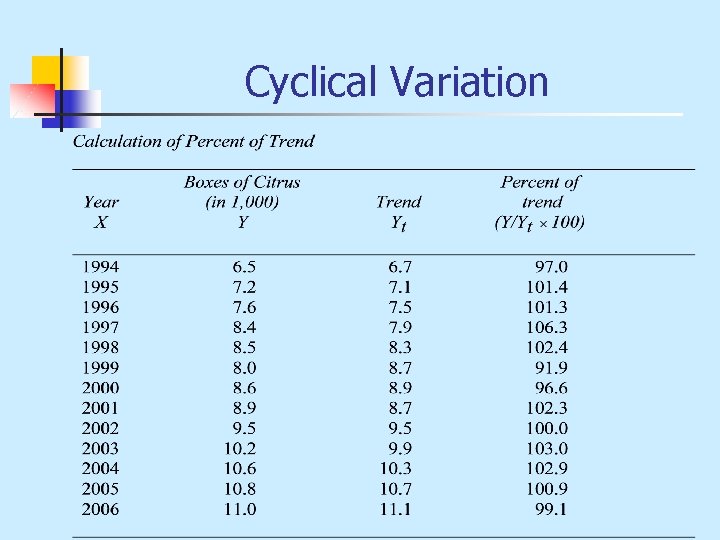

Cyclical Variation

Cyclical Variation

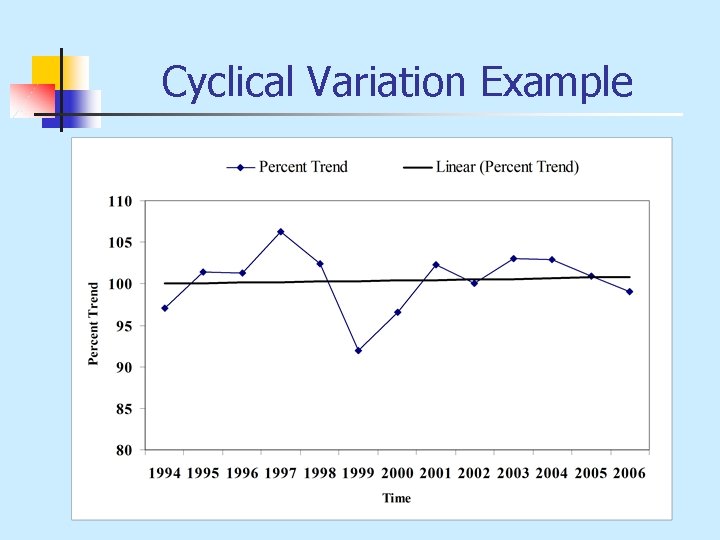

Cyclical Variation Example

Chapter Summary n Preliminary Adjustments to Data: n n n Trading Day Adjustment Price Adjustment Population Adjustment n Data Transformation n Patterns in Time Series Data n The Classical Decomposition Method

- Slides: 65