Building a Continuing Writing Course Writing by flickr

Building a Continuing Writing Course “Writing” by flickr user Izabela Wasilewska Prepared by Joonna Smitherman Trapp, Emory University

Continuing Writing @ Emory The goal of writing-intensive courses is to improve writing skills through writing regularly in a context where mentors in the various communities of discourse encourage, guide, and communicate to students high standards of writing through instruction and example. Writing intensive classes focus not only on the product, but also on the process of writing. Writing is not an elective option but a central focus of the course. http: //catalog. college. emory. edu/academic/ger/wrt. php

Continuing Writing @ Emory Summary of facts from http: //emorywae. org/designing-a-continuing-writing-course/ • Frequent writing assignments (which may be un-graded) • At least one rigorous writing project carried out over the course of the semester under the guidance and supervision of the instructor • At least one project revised based on feedback from instructor • Centrality of writing assignments to the intellectual experience of the course • Attention given to the process of teaching writing • Significance of writing assignments in final course grade (minimum 40%) • Quantity of polished writing produced (minimum 20 pages )

Continuing Writing @ Emory Key features to keep in mind for the sub-committee: • Writing Assignments scaffolded in course http: //emorywae. org/workshops/scaffolding-writing-assignments/ • Feedback loop (peer/instructor) with revision opportunity http: //emorywae. org/workshops/peer-respose/ and http: //emorywae. org/workshops/responding-to-student-writing/ • Plans for Writing instruction evident • Writing helps in class reserves • Models of assignments for student use • Visits by Writing Center Staff • Class time for instruction/workshopping

Discussion Why does Emory have a Continuing Writing Requirement? / What is the importance of writing in your discipline? Why are you a good person to teach writing in your field?

Writing as part of Course Designing a course is challenging, so much so that tutorials have even been developed to foster good course design! http: //serc. carleton. edu/NAGTWorkshops/coursedesign/tutorial/index. html Welcome to the Cutting Edge Course Design Tutorial Developed by Barbara J. Tewksbury (Hamilton College) and R. Heather Macdonald (College of William and Mary)

Writing as part of Course Design A Syllabus can reflect course design, but course design runs more deeply than just constructing a syllabus. Effective course design begins with planning ahead by asking yourself: Who are the students? What do I want students to be able to do? How will I measure students’ abilities? By asking yourself these questions at the onset of your course design process you will be able to focus more concretely on learning outcomes, which has proven to increase student learning substantially as opposed to merely shoehorning large quantities of content into class meetings.

Stages of Backward Course Design Fig 1. 1 Stages of Backward Design, . From Wiggins and Mc. Tighe, p. 18.

Establishing Course Priorities Fig 1. 1 Stages of Backward Design, . From Wiggins and Mc. Tighe, p. 18.

Fisher’s 3 Act Course Design

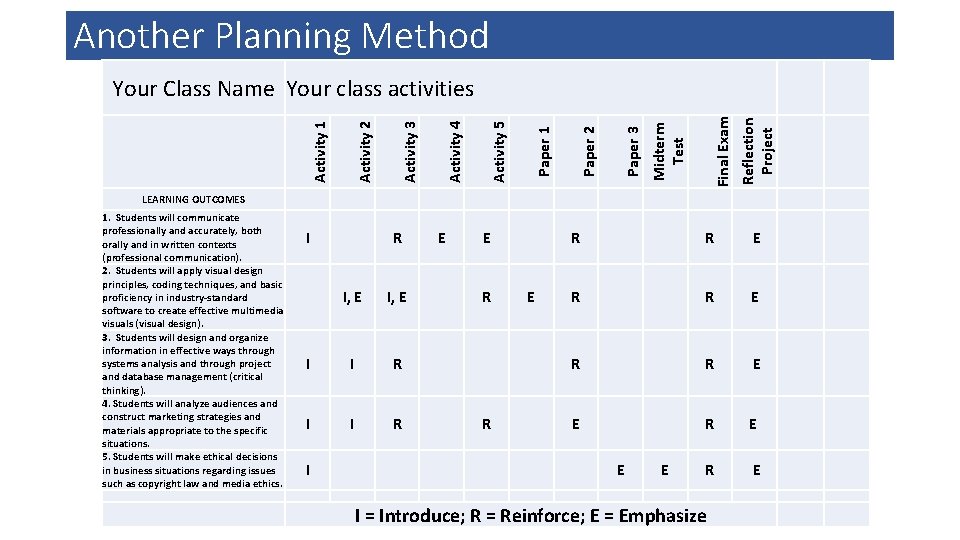

Another Planning Method LEARNING OUTCOMES 1. Students will communicate professionally and accurately, both orally and in written contexts (professional communication). 2. Students will apply visual design principles, coding techniques, and basic proficiency in industry-standard software to create effective multimedia visuals (visual design). 3. Students will design and organize information in effective ways through systems analysis and through project and database management (critical thinking). 4. Students will analyze audiences and construct marketing strategies and materials appropriate to the specific situations. 5. Students will make ethical decisions in business situations regarding issues such as copyright law and media ethics. Reflection Project Final Exam Midterm Test Paper 3 Paper 2 Paper 1 Activity 5 Activity 4 Activity 3 Activity 2 Activity 1 Your Class Name Your class activities I R E E R R E I, E R E R R E I I R R R E I I R R E I E E R E I = Introduce; R = Reinforce; E = Emphasize

The Building Blocks of a CWR Course @ Emory • Goals for your course coming from the discipline and topic • Goal(s) for the major writing project(s) in the course. These will demonstrate “centrality of writing assignments to the intellectual experience of the course” • Disciplinary content, assignments, projects, lectures, tests, discussions Picture from flickr user Michael Gauland • Scaffolding of writing throughout the course. Helping them develop the habit of thinking through writing assignments.

The Building Blocks of a CWR Course @ Emory Example Writing Goals demonstrating “centrality of writing assignments to the intellectual experience of the course” • Reflect about writing and learning processes and develop strategic thinking— the ability to apply what is learned in one rhetorical situation to quite different situations. • Analyze and reflect in writing about current research in sociology on [course topic]. • Design methods of displaying data for research in [field of study]. • Apply developing citizenship skills in a community setting through interviewing, note-taking, writing, and reflecting. • Assess in writing your team’s research and presentation using standard measures in [field of study]. • Outline the steps of the scientific method for lab experiments, leveraging examples from your team’s work this semester. Picture from flickr user Michael Gauland • Appropriately summarize, synthesize, and cite sources of historical data in making an historical argument.

What is good writing? (common features) • The writing is “voiced. ” A writer addressing us, taking responsibility for our understanding, and guiding us through the reading process. The writer uses transitions and cues consistent with discipline expectations. • The writing has authority and composure appropriate to the discipline’s expectations. • The writing makes difficult subject easier for readers to understand rather than increasing the difficulty and complexity. • The writing has organization and cohesion which sustains continuous reading without forcing rereading or disconnections.

What is good academic writing? (common features) • Clear evidence in writing that the writer has been persistent, open-minded, and disciplined in study. * has done the background reading * reflective, paid careful attention to object of study * internalizes knowledge and insight; demonstrates ability to speak about topic and generalize • Ability in writing to use reason; control of emotional responses * demonstrates fairness, carefulness * can analyze competing positions • Addresses a reader who is rational, reading for information, and seeking to form a reasoned response to the writing * addresses potential objections * creates in writing an argumentative ethos that is trustworthy

Assessing and Writing Assessing the Writing Students Do • Rubrics • Portfolio Grading • Peer Grading/Group Grading • Contract Grading Help with responding to and assessing student writing: http: //emorywae. org/workshops/responding-to-student-writing/ Using Writing as a Means of Assessing the Learning of Class Reflection on Course Learning Outcomes How reflection works in first-year writing: http: //emoryfyc. org/

Works Consulted • Wiggins, Grant, and Jay Mc. Tighe. Understanding by Design. Expanded 2 nd Ed. Pearson, 2005. “What is Backward Design” available on webpage at https: //www. fitnyc. edu/files/pdfs/Backward_design. pdf. • Gottschalk, Katherine and Keith Hjortshoj. The Elements of Teaching Writing: A Resource for Instructors in All Disciplines. Boston, MA: Bedford, 2004. • Thaiss, Chris and Terry Myers Zawacki. Engaged Writers, Dynamic Disciplines: Research on the Academic Writing Life. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook. 2006.

- Slides: 17