Bridging anticoagulation in patients undergoing cardiac rhythm device

Bridging anticoagulation in patients undergoing cardiac rhythm device implantation … a bridge over trouble waters… ALBERICO SORGATO Unità Operativa di Cardiologia Fondazione Poliambulanza Brescia Go, A. S. et al. JAMA 2001; 285: 2370 -2375.

… to bridge or not to bridge… • More than 35 million prescriptions for oral anticoagulation are written each year in the United States • In the most recent worldwide survey (2009), there were an estimated 1. 25 million pacemaker and 410 000 implantable cardioverter defibrillator operations. • Between 14 and 35% of patients receiving these devices require chronic OAC and their peri-procedural management may be challenging for physicians. • This is particularly true for the subset of patients with a moderate-to-high risk (≥ 5% per year) of thromboembolic (TE) events (NVAF pts with a CHA 2 DS 2 -VASc ≥ 3).

The therapeutic intent of heparin: … Bridging anticoagulation…

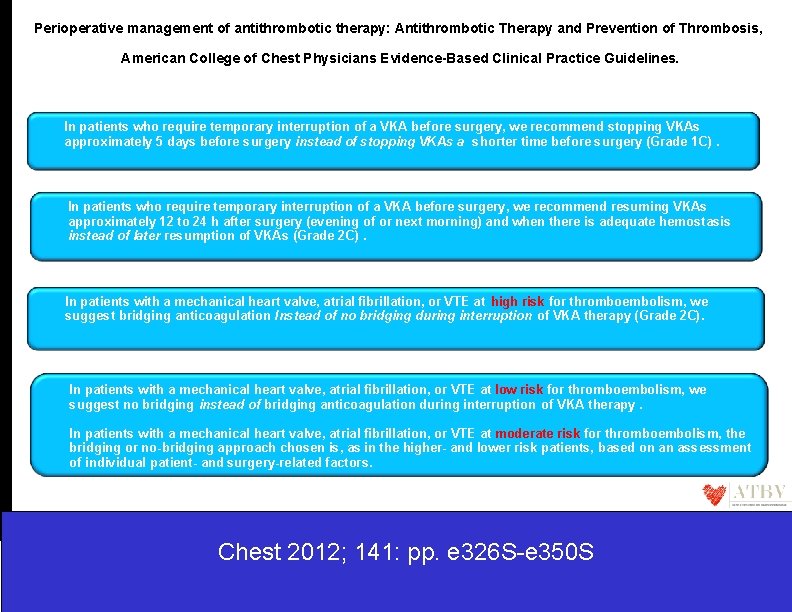

Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. In patients who require temporary interruption of a VKA before surgery, we recommend stopping VKAs approximately 5 days before surgery instead of stopping VKAs a shorter time before surgery (Grade 1 C). In patients who require temporary interruption of a VKA before surgery, we recommend resuming VKAs approximately 12 to 24 h after surgery (evening of or next morning) and when there is adequate hemostasis instead of later resumption of VKAs (Grade 2 C). In patients with a mechanical heart valve, atrial fibrillation, or VTE at high risk for thromboembolism, we suggest bridging anticoagulation Instead of no bridging during interruption of VKA therapy (Grade 2 C). In patients with a mechanical heart valve, atrial fibrillation, or VTE at low risk for thromboembolism, we suggest no bridging instead of bridging anticoagulation during interruption of VKA therapy. In patients with a mechanical heart valve, atrial fibrillation, or VTE at moderate risk for thromboembolism, the bridging or no-bridging approach chosen is, as in the higher- and lower risk patients, based on an assessment of individual patient- and surgery-related factors. Chest 2012; 141: pp. e 326 S-e 350 S

ACCP suggested risk stratification for perioperative thromboembolism J. D. Douketis Chest 2012; 141: pp. e 326 S-e 350 S Go, A. S. et al. JAMA 2001; 285: 2370 -2375.

Why is periprocedural heparin bridging recommended by the guidelines ? There are three main arguments for the use of bridging anticoagulation in the periprocedural period: 1) We didn’t have good clinical data on the peri-procedural TE risk (especially ATE risk such as stroke, transient ischaemic attack, or systemic embolism) in moderate-tohigh TE risk patients in the absence of heparin bridging. 2) The post-procedural bleed risk with bridging anticoagulation (OR 3. 6 for major bleed) may be understated especially with low bleed risk procedures 3) The consequences of ATE are more severe than those of VTE or major bleed , so that aggressive strategies to prevent post-procedural TE risk should take precedence over those that prevent bleeding. • VTE is associated with a 6% rate of death or permanent disability • Major bleeding with a 8 -9% • ATE is associated with a 70% rate of death or permanent disability in stroke

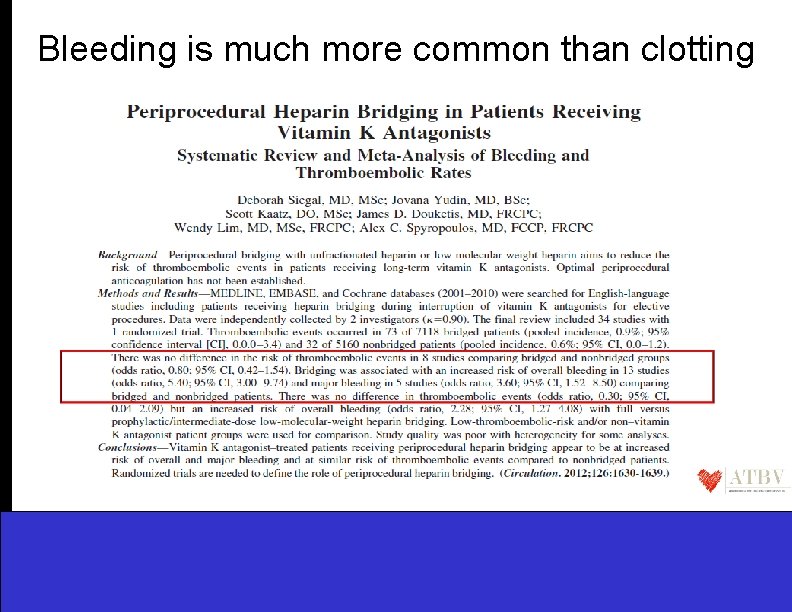

Bleeding is much more common than clotting

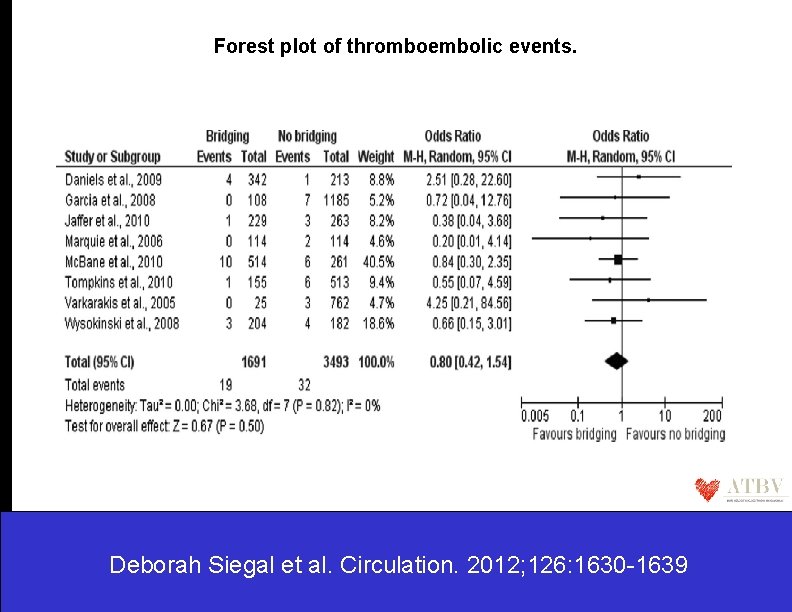

Forest plot of thromboembolic events. Deborah Siegal et al. Circulation. 2012; 126: 1630 -1639

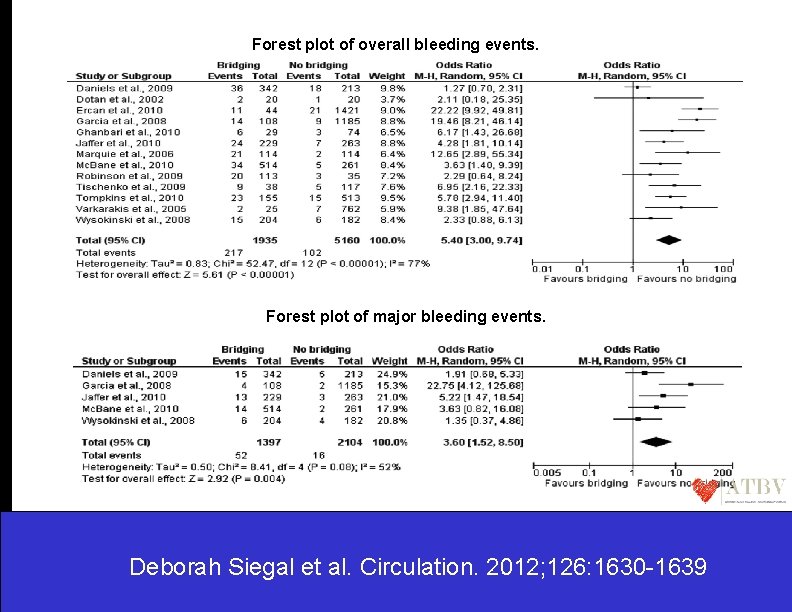

Forest plot of overall bleeding events. Forest plot of major bleeding events. Deborah Siegal et al. Circulation. 2012; 126: 1630 -1639

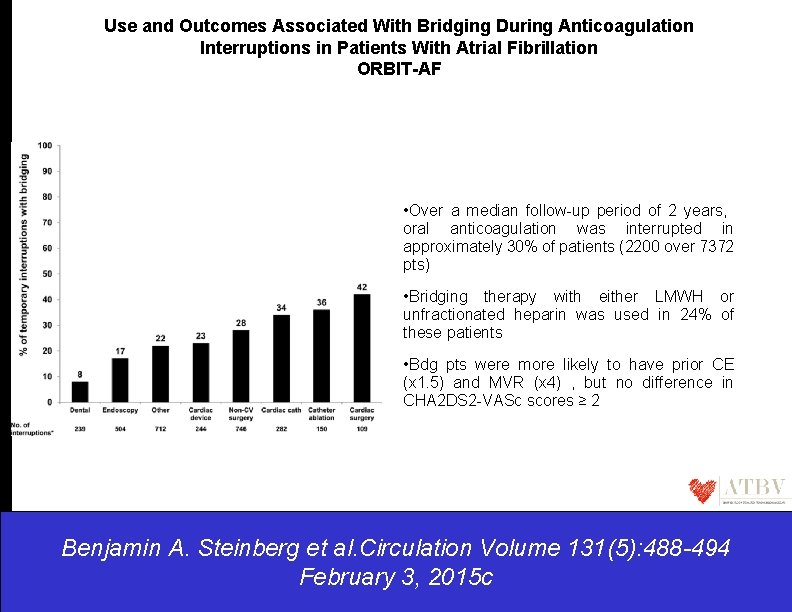

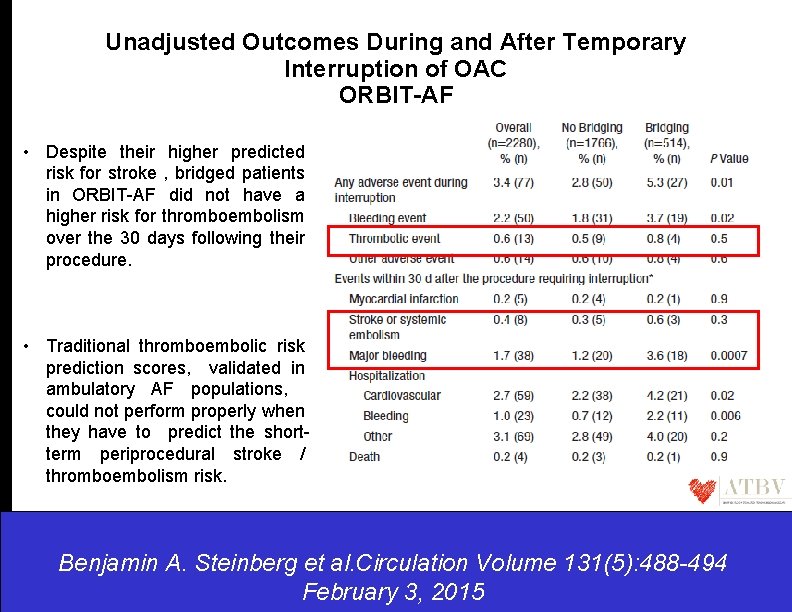

Use and Outcomes Associated With Bridging During Anticoagulation Interruptions in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation ORBIT-AF • Over a median follow-up period of 2 years, oral anticoagulation was interrupted in approximately 30% of patients (2200 over 7372 pts) • Bridging therapy with either LMWH or unfractionated heparin was used in 24% of these patients • Bdg pts were more likely to have prior CE (x 1. 5) and MVR (x 4) , but no difference in CHA 2 DS 2 -VASc scores ≥ 2 Benjamin A. Steinberg et al. Circulation Volume 131(5): 488 -494 February 3, 2015 c

Unadjusted Outcomes During and After Temporary Interruption of OAC ORBIT-AF • Despite their higher predicted risk for stroke , bridged patients in ORBIT-AF did not have a higher risk for thromboembolism over the 30 days following their procedure. • Traditional thromboembolic risk prediction scores, validated in ambulatory AF populations, could not perform properly when they have to predict the shortterm periprocedural stroke / thromboembolism risk. Benjamin A. Steinberg et al. Circulation Volume 131(5): 488 -494 February 3, 2015

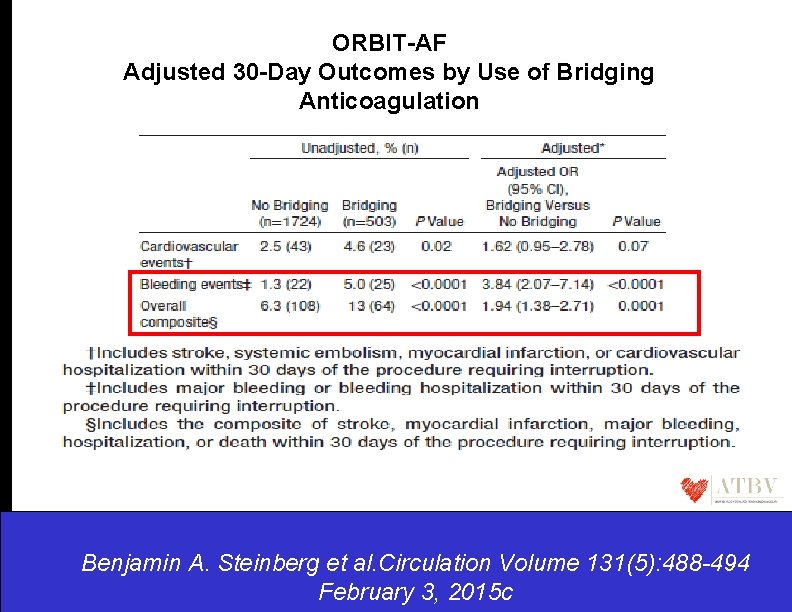

ORBIT-AF Adjusted 30 -Day Outcomes by Use of Bridging Anticoagulation Benjamin A. Steinberg et al. Circulation Benjamin A. Volume Steinberg et al. 131(5): 488 -494 Circulation. 2015; 131: 488 -494 February 3, 2015 c

ORBIT-AF conclusions …a bridge too far… (1) OAC interruption was common (approximately half of AF patients over a 2 -year follow-up), (2) A bridging strategy was used in a significant minority (1 in 4) of ORBIT-AF participants with interrupted OAC, (3) Bridging was associated with higher rates of bleeding and overall adverse event rates. A. These results raise doubts over the dogma of a bridging strategy for AF patients undergoing procedures B. Lack of randomized studies to understand the correct periprocedural AC decision making

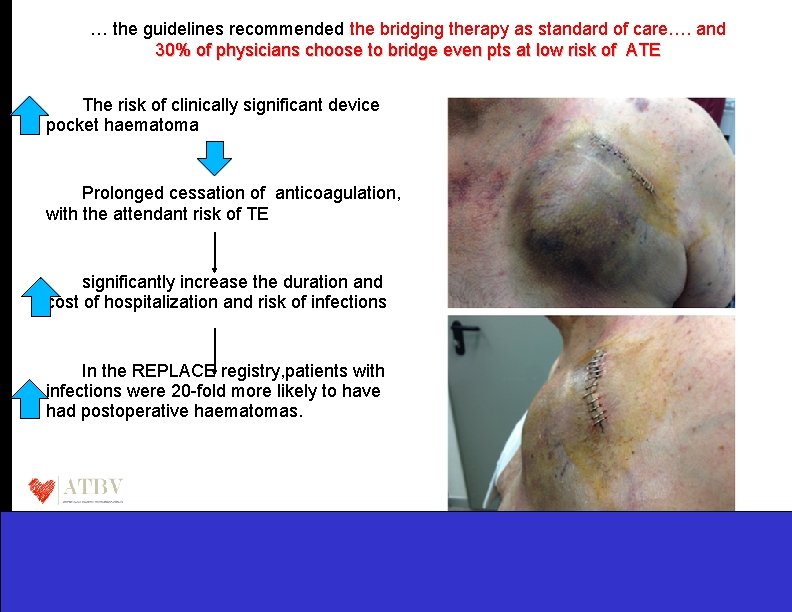

… the guidelines recommended the bridging therapy as standard of care…. and 30% of physicians choose to bridge even pts at low risk of ATE The risk of clinically significant device pocket haematoma Prolonged cessation of anticoagulation, with the attendant risk of TE significantly increase the duration and cost of hospitalization and risk of infections In the REPLACE registry, patients with infections were 20 -fold more likely to have had postoperative haematomas.

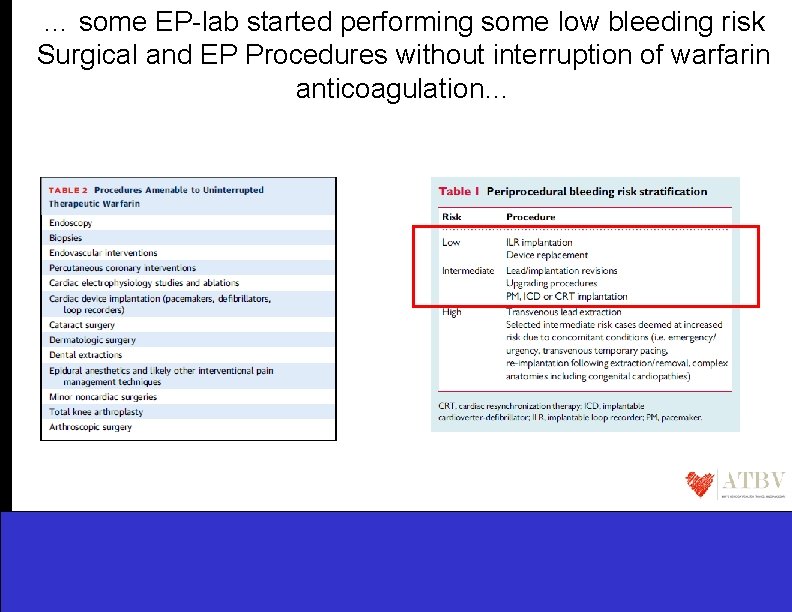

… some EP-lab started performing some low bleeding risk Surgical and EP Procedures without interruption of warfarin anticoagulation…

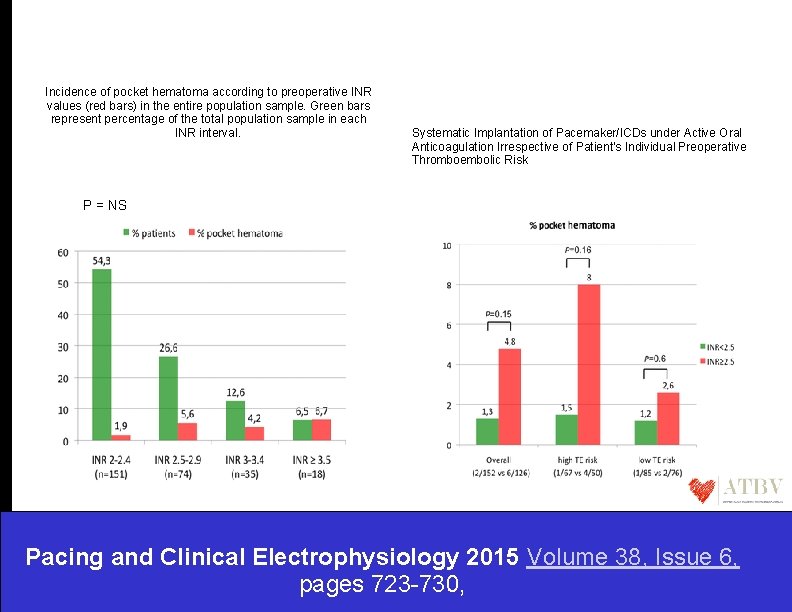

Incidence of pocket hematoma according to preoperative INR values (red bars) in the entire population sample. Green bars represent percentage of the total population sample in each INR interval. Systematic Implantation of Pacemaker/ICDs under Active Oral Anticoagulation Irrespective of Patient's Individual Preoperative Thromboembolic Risk P = NS Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology 2015 Volume 38, Issue 6, pages 723 -730,

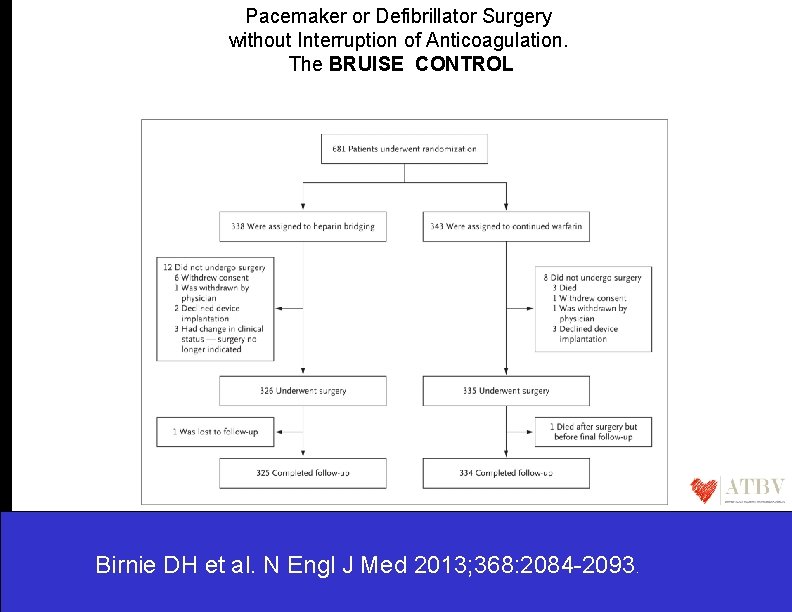

Pacemaker or Defibrillator Surgery without Interruption of Anticoagulation. The BRUISE CONTROL Birnie DH et al. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 2084 -2093.

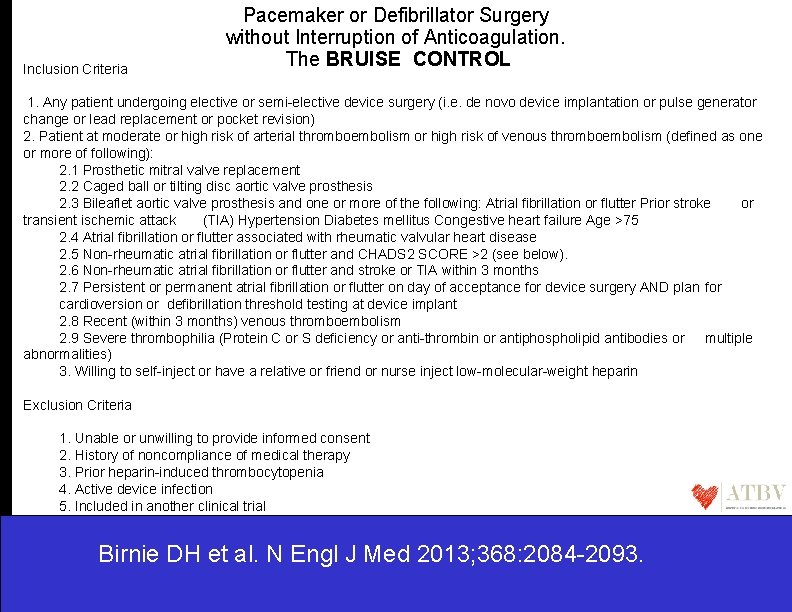

Inclusion Criteria Pacemaker or Defibrillator Surgery without Interruption of Anticoagulation. The BRUISE CONTROL 1. Any patient undergoing elective or semi-elective device surgery (i. e. de novo device implantation or pulse generator change or lead replacement or pocket revision) 2. Patient at moderate or high risk of arterial thromboembolism or high risk of venous thromboembolism (defined as one or more of following): 2. 1 Prosthetic mitral valve replacement 2. 2 Caged ball or tilting disc aortic valve prosthesis 2. 3 Bileaflet aortic valve prosthesis and one or more of the following: Atrial fibrillation or flutter Prior stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) Hypertension Diabetes mellitus Congestive heart failure Age >75 2. 4 Atrial fibrillation or flutter associated with rheumatic valvular heart disease 2. 5 Non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation or flutter and CHADS 2 SCORE >2 (see below). 2. 6 Non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation or flutter and stroke or TIA within 3 months 2. 7 Persistent or permanent atrial fibrillation or flutter on day of acceptance for device surgery AND plan for cardioversion or defibrillation threshold testing at device implant 2. 8 Recent (within 3 months) venous thromboembolism 2. 9 Severe thrombophilia (Protein C or S deficiency or anti-thrombin or antiphospholipid antibodies or multiple abnormalities) 3. Willing to self-inject or have a relative or friend or nurse inject low-molecular-weight heparin Exclusion Criteria 1. Unable or unwilling to provide informed consent 2. History of noncompliance of medical therapy 3. Prior heparin-induced thrombocytopenia 4. Active device infection 5. Included in another clinical trial Birnie DH et al. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 2084 -2093.

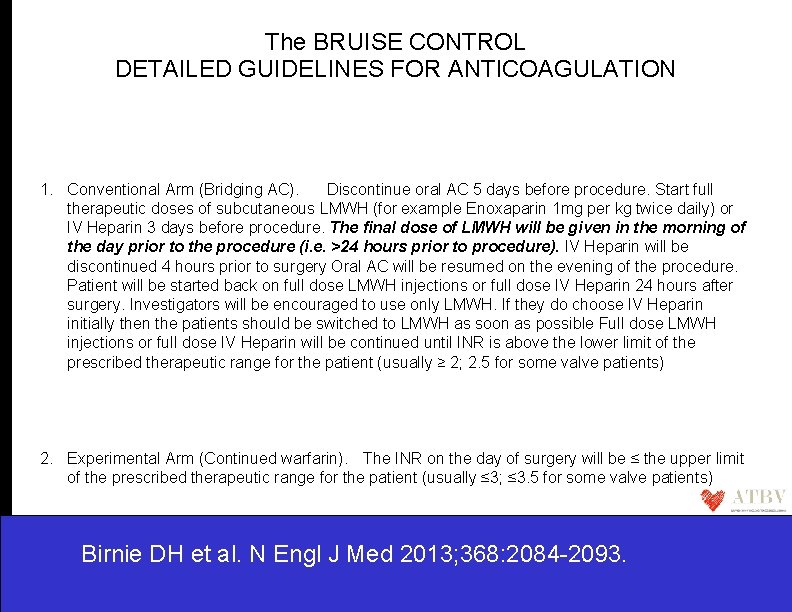

The BRUISE CONTROL DETAILED GUIDELINES FOR ANTICOAGULATION 1. Conventional Arm (Bridging AC). Discontinue oral AC 5 days before procedure. Start full therapeutic doses of subcutaneous LMWH (for example Enoxaparin 1 mg per kg twice daily) or IV Heparin 3 days before procedure. The final dose of LMWH will be given in the morning of the day prior to the procedure (i. e. >24 hours prior to procedure). IV Heparin will be discontinued 4 hours prior to surgery Oral AC will be resumed on the evening of the procedure. Patient will be started back on full dose LMWH injections or full dose IV Heparin 24 hours after surgery. Investigators will be encouraged to use only LMWH. If they do choose IV Heparin initially then the patients should be switched to LMWH as soon as possible Full dose LMWH injections or full dose IV Heparin will be continued until INR is above the lower limit of the prescribed therapeutic range for the patient (usually ≥ 2; 2. 5 for some valve patients) 2. Experimental Arm (Continued warfarin). The INR on the day of surgery will be ≤ the upper limit of the prescribed therapeutic range for the patient (usually ≤ 3; ≤ 3. 5 for some valve patients) Birnie DH et al. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 2084 -2093.

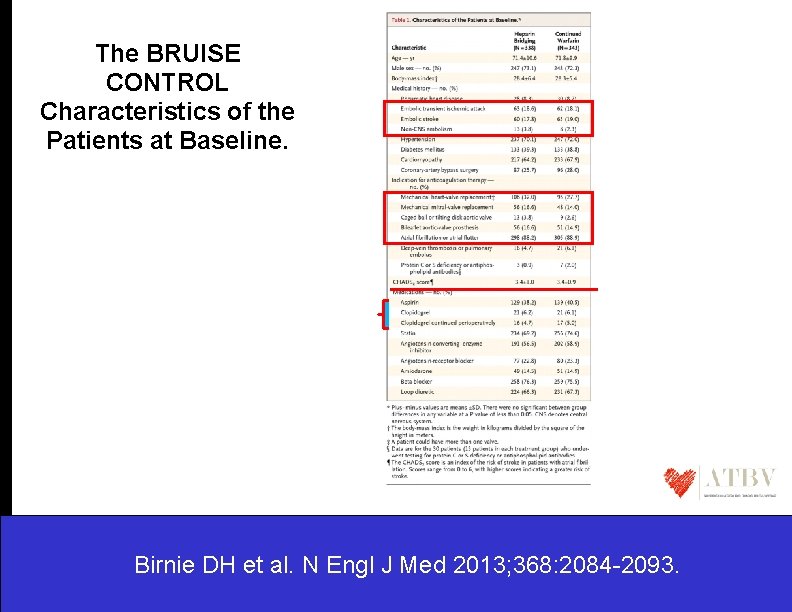

The BRUISE CONTROL Characteristics of the Patients at Baseline. Birnie DH et al. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 2084 -2093.

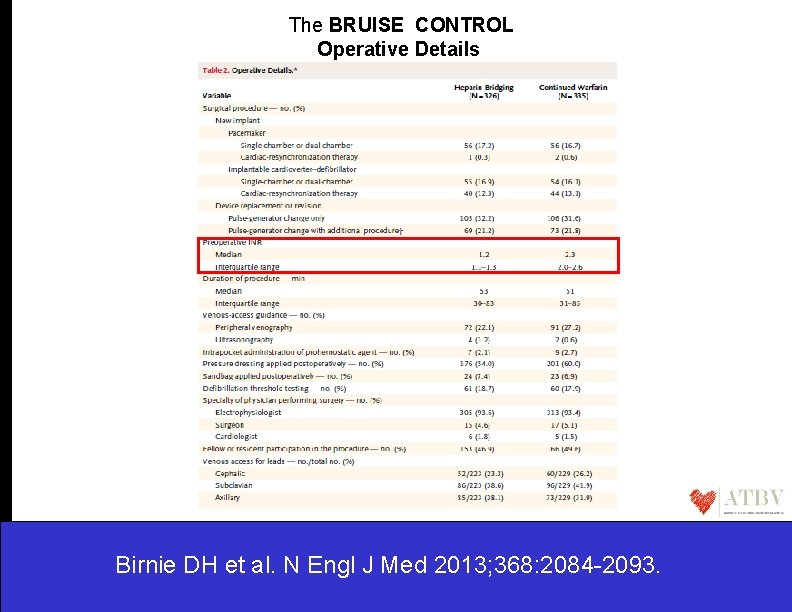

The BRUISE CONTROL Operative Details Birnie DH et al. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 2084 -2093.

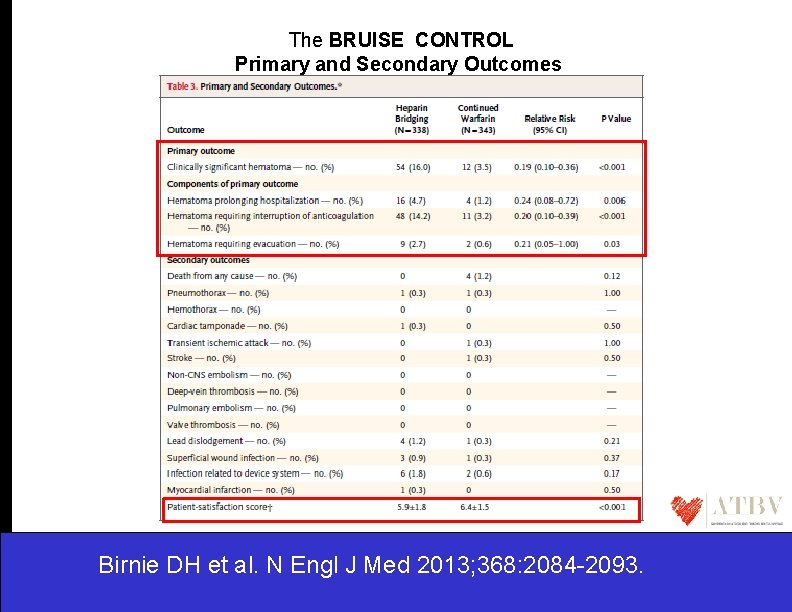

The BRUISE CONTROL Primary and Secondary Outcomes Birnie DH et al. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 2084 -2093.

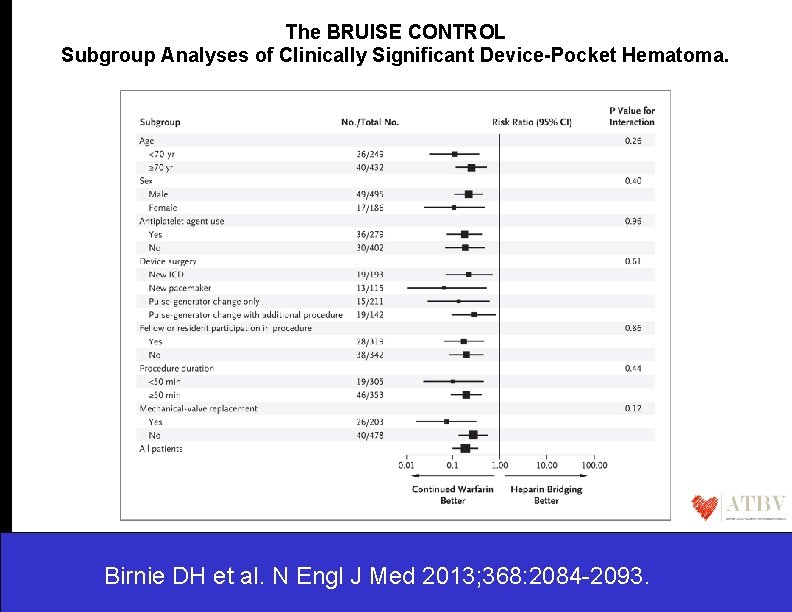

The BRUISE CONTROL Subgroup Analyses of Clinically Significant Device-Pocket Hematoma. Birnie DH et al. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 2084 -2093.

The BRUISE CONTROL …. . Therefore to perform device surgery continuing warfarin therapy (median INR of 2. 3) , • • • is associated with a significantly lower rate of pocket hematoma was not associated with any major perioperative bleeding events was associated with greater patient satisfaction ……These results suggest that continuation of warfarin during pacemaker or ICD surgery may be preferable to bridging therapy with heparin, at least for patients like those enrolled in this trial…… Birnie DH et al. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 2084 -2093.

The BRUISE CONTROL “the anticoagulant stress test ” • The significantly lower rate of device-pocket hematoma that was observed with continued warfarin may seem counterintuitive. • One explanation that has been proposed is the concept of an “anticoagulant stress test” That is, if patients undergo surgery while receiving full-dose anticoagulation therapy, any excessive bleeding will be detectable and appropriately managed by the electrophysiologist while the wound is still open. In contrast, if bridging therapy with heparin is used, such bleeding may be apparent only when full-dose anticoagulation therapy is resumed postoperatively. Birnie DH et al. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 2084 -2093.

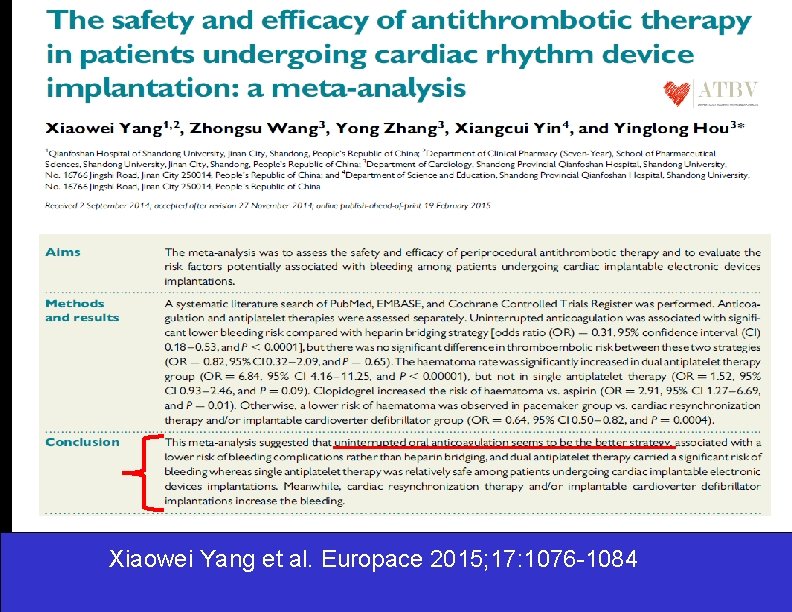

Xiaowei Yang et al. Europace 2015; 17: 1076 -1084

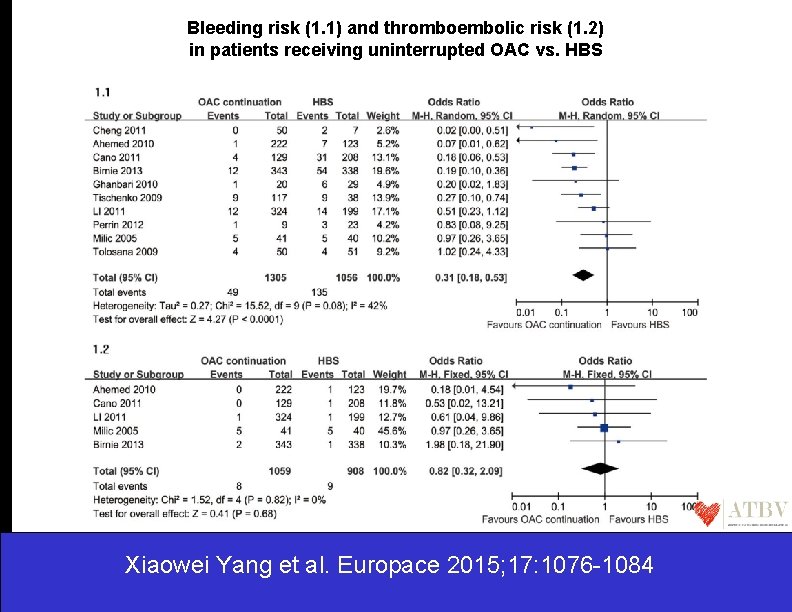

Bleeding risk (1. 1) and thromboembolic risk (1. 2) in patients receiving uninterrupted OAC vs. HBS Xiaowei Yang et al. Europace 2015; 17: 1076 -1084

We still have unanswered questions……. The BRIDGE trial • The fundamental question of whether bridging anticoagulation is necessary during perioperative warfarin interruption has remained unanswered • The BRIDGE trial was designed to address a simple question: in patients with atrial fibrillation, is heparin bridging needed during interruption of warfarin therapy before and after an operation or other invasive procedure? • The authors hypothesized that forgoing bridging altogether would be noninferior to bridging with low-molecular-weight heparin for the prevention of perioperative arterial thromboembolism and would be superior to bridging with regard to the outcome of major bleeding.

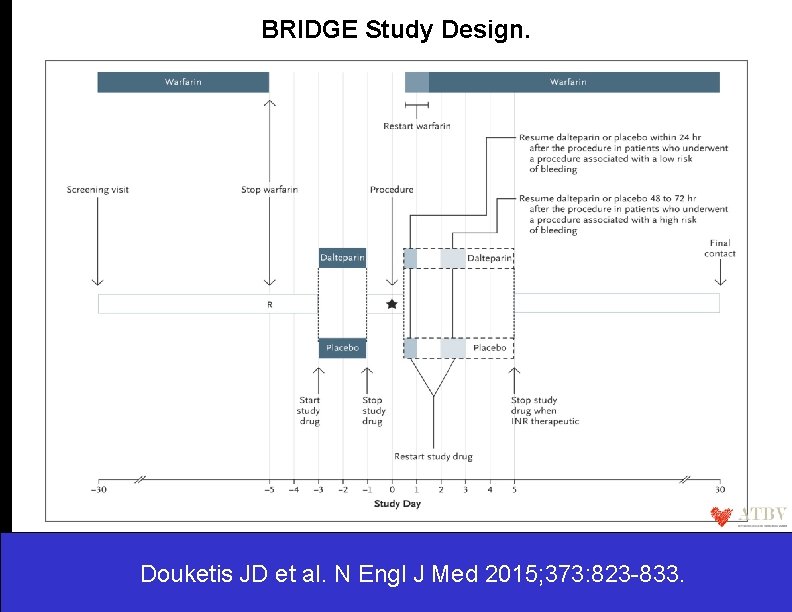

BRIDGE Study Design. Douketis JD et al. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 823 -833.

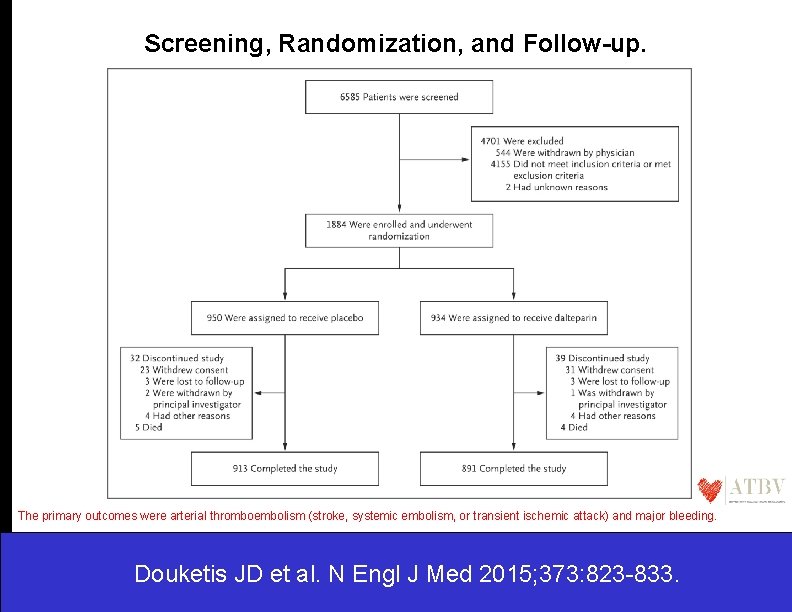

Screening, Randomization, and Follow-up. The primary outcomes were arterial thromboembolism (stroke, systemic embolism, or transient ischemic attack) and major bleeding. Douketis JD et al. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 823 -833.

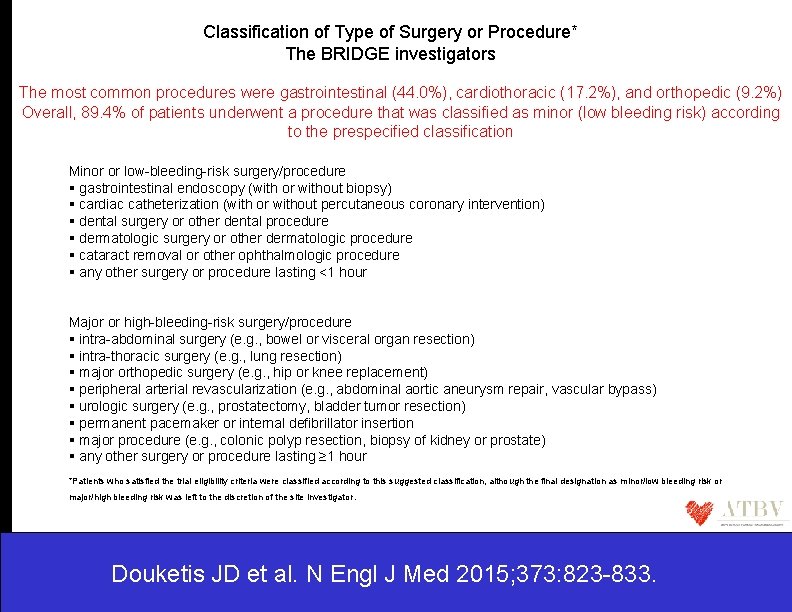

Classification of Type of Surgery or Procedure* The BRIDGE investigators The most common procedures were gastrointestinal (44. 0%), cardiothoracic (17. 2%), and orthopedic (9. 2%) Overall, 89. 4% of patients underwent a procedure that was classified as minor (low bleeding risk) according to the prespecified classification Minor or low-bleeding-risk surgery/procedure gastrointestinal endoscopy (with or without biopsy) cardiac catheterization (with or without percutaneous coronary intervention) dental surgery or other dental procedure dermatologic surgery or other dermatologic procedure cataract removal or other ophthalmologic procedure any other surgery or procedure lasting <1 hour Major or high-bleeding-risk surgery/procedure intra-abdominal surgery (e. g. , bowel or visceral organ resection) intra-thoracic surgery (e. g. , lung resection) major orthopedic surgery (e. g. , hip or knee replacement) peripheral arterial revascularization (e. g. , abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, vascular bypass) urologic surgery (e. g. , prostatectomy, bladder tumor resection) permanent pacemaker or internal defibrillator insertion major procedure (e. g. , colonic polyp resection, biopsy of kidney or prostate) any other surgery or procedure lasting ≥ 1 hour *Patients who satisfied the trial eligibility criteria were classified according to this suggested classification, although the final designation as minor/low bleeding risk or major/high bleeding risk was left to the discretion of the site investigator. Douketis JD et al. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 823 -833.

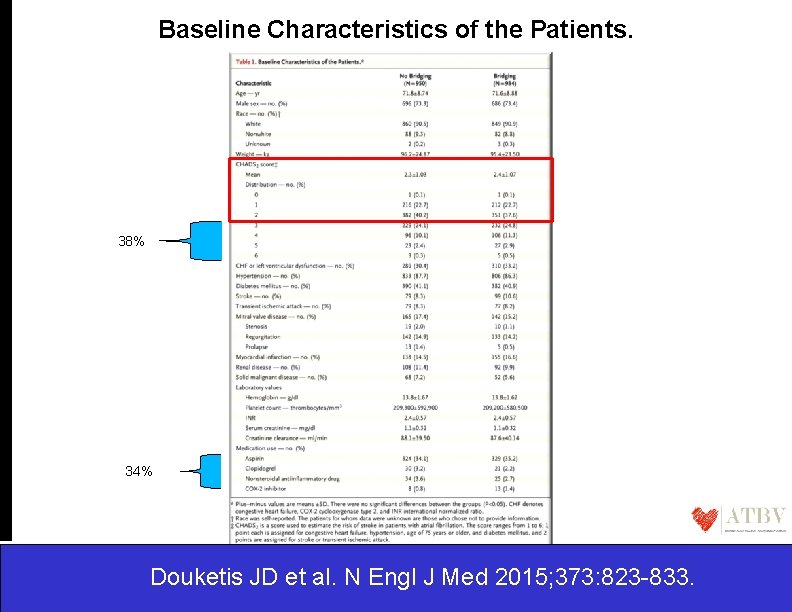

Baseline Characteristics of the Patients. 38% 34% Douketis JD et al. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 823 -833.

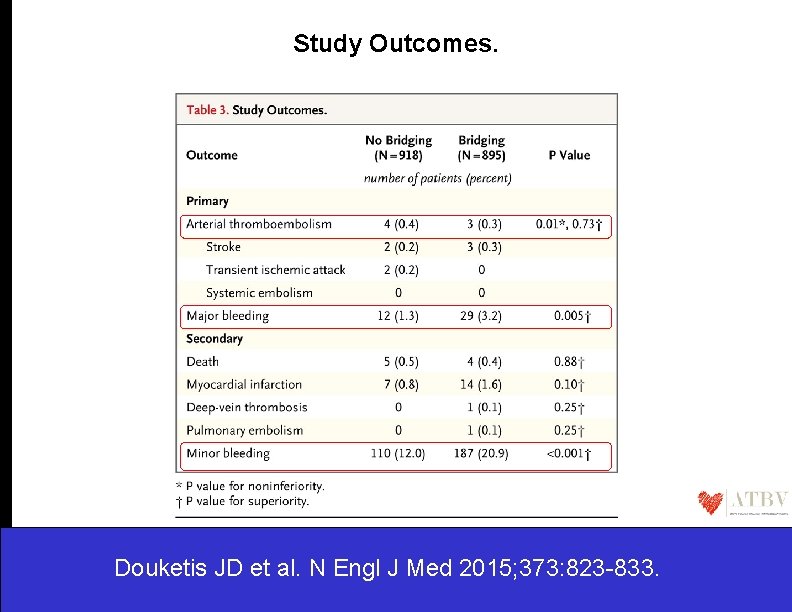

Study Outcomes. Douketis JD et al. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 823 -833.

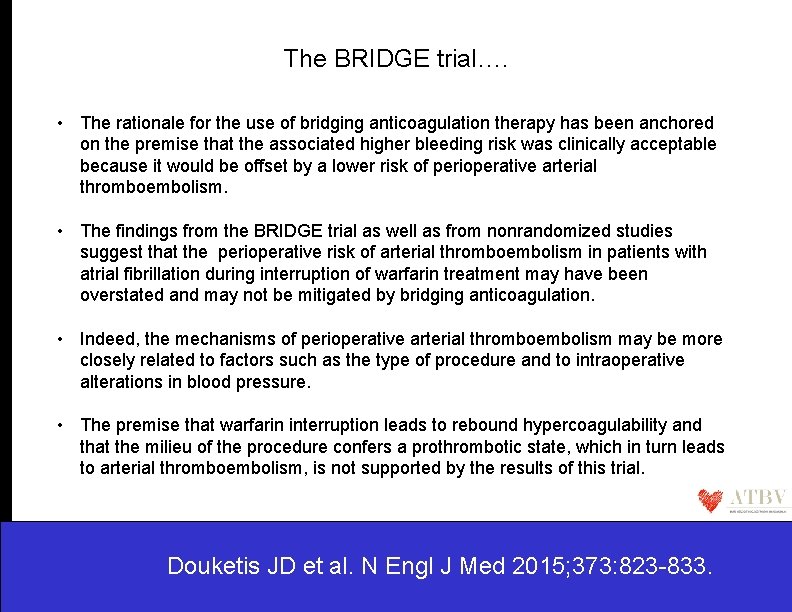

The BRIDGE trial…. • The rationale for the use of bridging anticoagulation therapy has been anchored on the premise that the associated higher bleeding risk was clinically acceptable because it would be offset by a lower risk of perioperative arterial thromboembolism. • The findings from the BRIDGE trial as well as from nonrandomized studies suggest that the perioperative risk of arterial thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation during interruption of warfarin treatment may have been overstated and may not be mitigated by bridging anticoagulation. • Indeed, the mechanisms of perioperative arterial thromboembolism may be more closely related to factors such as the type of procedure and to intraoperative alterations in blood pressure. • The premise that warfarin interruption leads to rebound hypercoagulability and that the milieu of the procedure confers a prothrombotic state, which in turn leads to arterial thromboembolism, is not supported by the results of this trial. Douketis JD et al. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 823 -833.

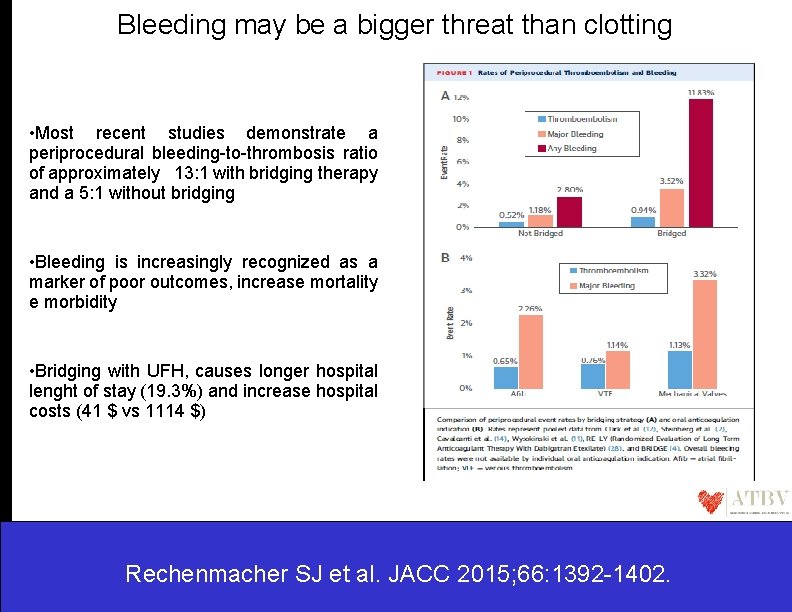

Bleeding may be a bigger threat than clotting • Most recent studies demonstrate a periprocedural bleeding-to-thrombosis ratio of approximately 13: 1 with bridging therapy and a 5: 1 without bridging • Bleeding is increasingly recognized as a marker of poor outcomes, increase mortality e morbidity • Bridging with UFH, causes longer hospital lenght of stay (19. 3%) and increase hospital costs (41 $ vs 1114 $) Rechenmacher SJ et al. JACC 2015; 66: 1392 -1402.

Device implantation in patients receiving vitamin K antagonists: EHRA POSITION PAPER • In the following patient groups with AF, it is recommended to perform device surgery without interruption of VKA. (i) Patients with non-valvular AF and a CHA 2 DS 2 -VASc score of ≥ 3. (ii) Patients with a CHA 2 DS 2 -VASc score of 2 due to stroke or TIA within 3 months. (iii) Patients with AF planned for cardioversion or defibrillation testing at device implantation. (iv) Patients with AF and rheumatic valvular heart disease. • In the following patient groups with prosthetic heart valves, it is recommended to perform device surgery without interruption of VKA. (i) Prosthetic mitral valve. (ii) Caged ball or tilting disc aortic valve. (iii) Bileaflet aortic valve prosthesis and AF and a CHA 2 DS 2 -VASc score of ≥ 2. • In patients with severe thrombophilia, it is recommended to perform device surgery without interruption of VKA. • In patients with recent venous thromboembolism (within 3 months), It is recommended to perform device surgery without interruption of VKA. . Christian Sticherling et al. Europace 2015; 17: 1197 -1214

Device implantation in patients receiving vitamin K antagonists: EHRA POSITION PAPER • The INR on the day of surgery should be under the upper limit of the prescribed therapeutic range for the patient (usually ≤ 3; ≤ 3. 5 for some valve patients). • In patients with an annual risk of TE events less then 5% either perform surgery without interruption of VKA or interrupt VKA 3– 4 days before surgery, no heparin bridging is recommended. • Interruption of VKA and bridging with an unfractionated heparin or LMWH should be avoided. Christian Sticherling et al. Europace 2015; 17: 1197 -1214

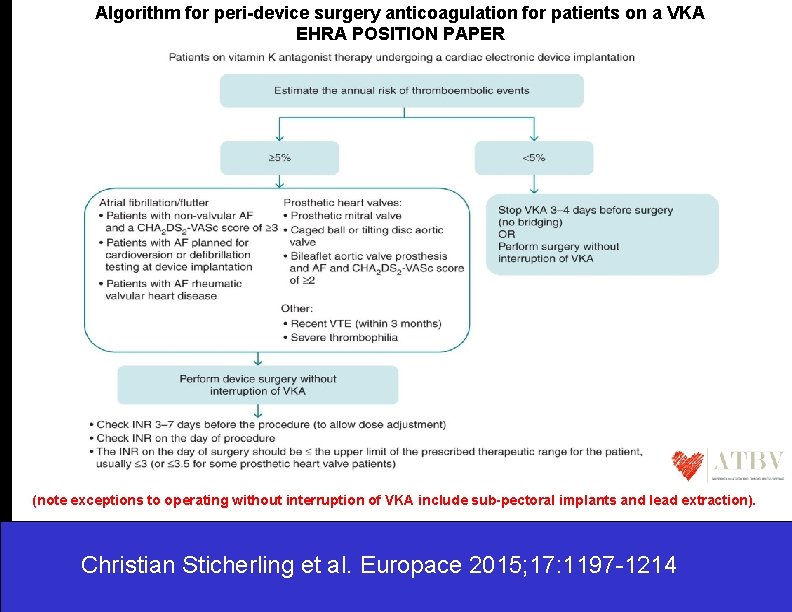

Algorithm for peri-device surgery anticoagulation for patients on a VKA EHRA POSITION PAPER (note exceptions to operating without interruption of VKA include sub-pectoral implants and lead extraction). Christian Sticherling et al. Europace 2015; 17: 1197 -1214

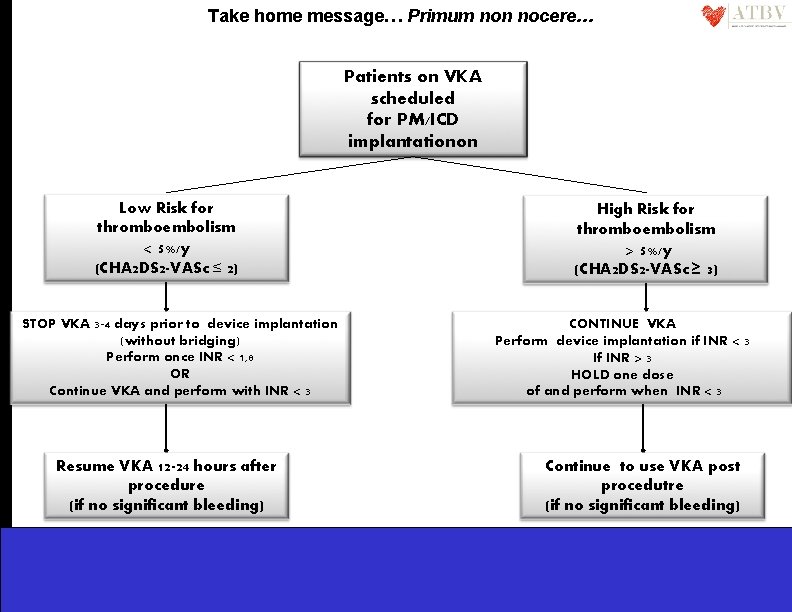

Take home message… Primum non nocere… Patients on VKA scheduled for PM/ICD implantationon Low Risk for thromboembolism < 5%/y (CHA 2 DS 2 -VASc ≤ 2) STOP VKA 3 -4 days prior to device implantation (without bridging) Perform once INR < 1, 8 OR Continue VKA and perform with INR < 3 Resume VKA 12 -24 hours after procedure (if no significant bleeding) High Risk for thromboembolism > 5%/y (CHA 2 DS 2 -VASc ≥ 3) CONTINUE VKA Perform device implantation if INR < 3 If INR > 3 HOLD one dose of and perform when INR < 3 Continue to use VKA post procedutre (if no significant bleeding)

- Slides: 39