Borrowing Prior Information What to Borrow How Much

Borrowing Prior Information: What to Borrow, How Much to Borrow, and the Effective Communication between the Sponsor and FDA Laura Lu, Ph. D Division of Biostatistics, CDRH

Bayesian Statistics: Submissions to CDRH • Since 1999, at least 25 original PMAs and PMA supplements have been approved with a Bayesian analysis for the primary endpoint. – Most are for therapeutic devices – Several are for diagnostic devices • Many IDEs have also been approved with a Bayesian design, quite a few EAPs • Several applications for “substantial equivalence” (510(k)s) 2

Why Prior Information in Device Studies? • The mechanism of action of the device is often very well understood: ‒ Local as opposed to systemic ‒ Physical as opposed to pharmacokinetic ‒ Treatment effect of device is relatively easier to be predicted with pre-clinical results (e. g. , bench testing) • Devices evolve while drugs are discovered ‒ Slight changes to a device may lead to small changes in its effects ‒ Results of previous versions of device may serve as good prior information 3

http: //www. fda. gov/Medical. Devices/Device. Re gulationand. Guidance/Guidance. Documents/uc m 071072. htm 4

Considerations in Regulatory Setting • Prior planning of the design and analysis is crucial. Before the new study begins – Prior information identified – The amount of prior information borrowed to be agreed upon • Not a substitute for good science – – Need of randomization Handling of missing value Assessment of bias Adequacy of analysis population 5

Source of Prior Information RWE, e. g. data from clinical registry Pilots studies Studies conducted overseas Data of very similar devices Subgroups from a failed study Adult population to be extrapolated for pediatric population • Simulated patient outcomes based on clinical/engineering models • • • 6

Use of Prior Information • Borrow information for the same treatment ‒ Supplemental control data from historical trials or registries • Borrow information between treatment arms (treatment effect) ‒ Adult data for pediatric indication ‒ Trials for a previous generation device 7

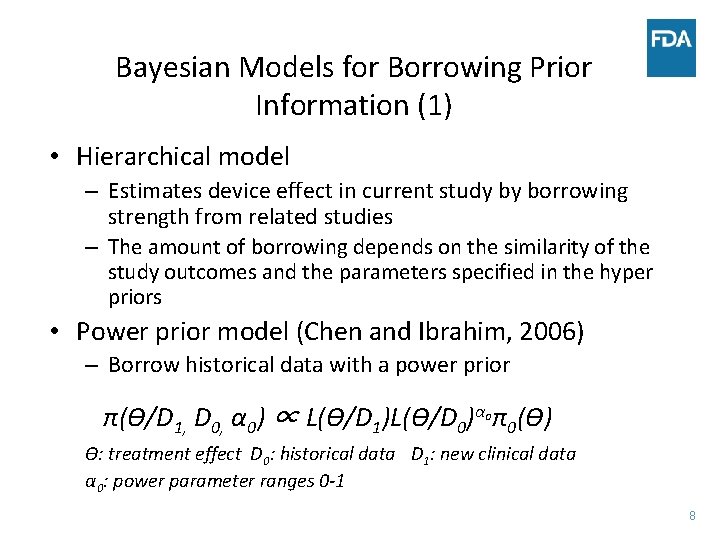

Bayesian Models for Borrowing Prior Information (1) • Hierarchical model – Estimates device effect in current study by borrowing strength from related studies – The amount of borrowing depends on the similarity of the study outcomes and the parameters specified in the hyper priors • Power prior model (Chen and Ibrahim, 2006) – Borrow historical data with a power prior π(ϴ/D 1, D 0, α 0) ∝ L(ϴ/D 1)L(ϴ/D 0)αoπ0(ϴ) ϴ: treatment effect D 0: historical data D 1: new clinical data α 0: power parameter ranges 0 -1 8

Bayesian Models for Borrowing Prior Information (2) • Both the hierarchical and power prior model could incorporate multiple prior datasets • When there is only one prior study, – Power prior approach is considered a straight forward way to borrow historical information with a discount – Power prior approach has a more intuitive interpretation for the clinicians – Challenge in choosing α 0 9

How Much to Borrow? -Clinical Judgment • Clinical judgment on the relevance of prior information – Similarity in protocol design (treatment arms, endpoints, target population, etc. ), and – Similarity of clinical practice • In many situations we do not wish the prior information to dominate the posterior distribution, especially – Patient population – A subgroup selected from a failed study without a strong clinical rationale 10

How Much to Borrow? -Statistical/Regulatory Considerations • Patient level data including baseline characteristics to assess exchangeability (similarity) between patients and studies • All information should be considered (favorable and nonfavorable) – Cherry picking favorable outcomes (instead of using clinically sound rationale) will lead to biased inferences for posterior distribution of the treatment effect • Type I error rate to keep the consistency/connection with the evidence level required for trials with frequentist design 11

Example 1 • Device A was approved in Europe • A randomized US trial was proposed for a more inclusive patient population with the same control • Plan to borrow both treatment and control information from the European study 12

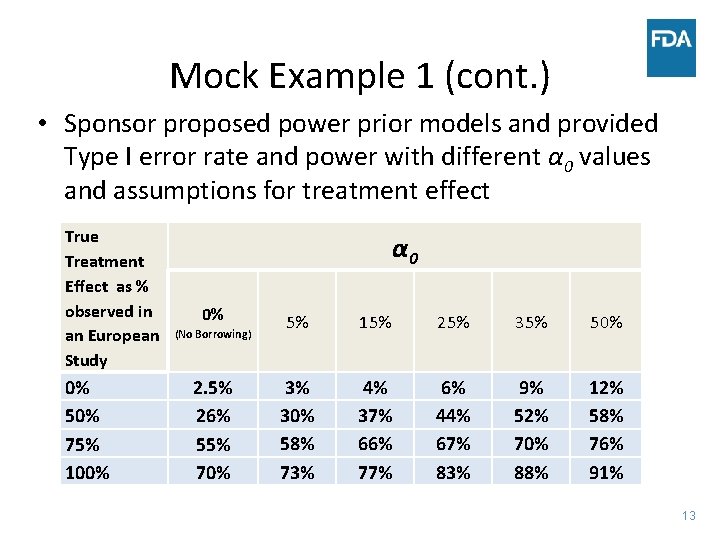

Mock Example 1 (cont. ) • Sponsor proposed power prior models and provided Type I error rate and power with different α 0 values and assumptions for treatment effect True Treatment Effect as % observed in an European Study 0% 50% 75% 100% α 0 0% (No Borrowing) 2. 5% 26% 55% 70% 5% 15% 25% 35% 50% 3% 30% 58% 73% 4% 37% 66% 77% 6% 44% 67% 83% 9% 52% 70% 88% 12% 58% 76% 91% 13

FDA’s Considerations • Due to the more inclusive patient population and potential difference in clinical practice, decision for approval should be mainly based on the information in US population • Reasonable Type I error rate • At the time of PMA submission, assess – Consistency of US data and European data – Effective sample size • A minimum number of patients should be enrolled to evaluate safety endpoints 14

Example 2 • The first study for Device B failed • Based on subgroup analyses (1 in >10 subgroups), the result was more promising in: – A secondary endpoint among patients enrolled in Subgroup A • The sponsor proposed – To enroll patients similar to those in Subgroup A – Borrow data from Subgroup A data in the first study 15

FDA’s Considerations • A better treatment effect in Subgroup A is supported by a clinical rationale. However, ‘better’ subgroups can be defined by other clinical rationales and based on different cut-points. • Could not exclude the possibility of a spurious finding among the outcomes of all subgroups and endpoints • Statistical model should appropriately take into account the relationship of results in Subgroup A and other subgroups – The number of subgroup analyses – A more convincing clinical rationale leads to relatively more borrowing from Group A and less borrowing from Group Ac – All subjects in the study should be borrowed if Group A was only a chance finding • Ongoing discussion on the amount to borrow 16

Example 3 • A very large trial is usually conducted to estimate Device C’s long term failure rate • An engineering model is proposed to predict clinical outcomes (virtual patient model) • The sample size of the new study is reduced when incorporating virtual patient data with a power prior model π(ϴ/D 1, D 0, α 0) ∝ L(ϴ/D 1)L(ϴ/D 0)αoπ0(ϴ) 17

FDA’s Considerations • Advantages: – Easy to interpret – Regret control – More powerful than hierarchical models and the power prior model with pre-specified α 0 • Challenges: – Determination of maximum sample size for D 0 (virtual patients): How reliable of the engineering model? – Determination of α 0 • Definition of the ‘similarity’ function • Double use of virtual patient data violates likelihood principle 18

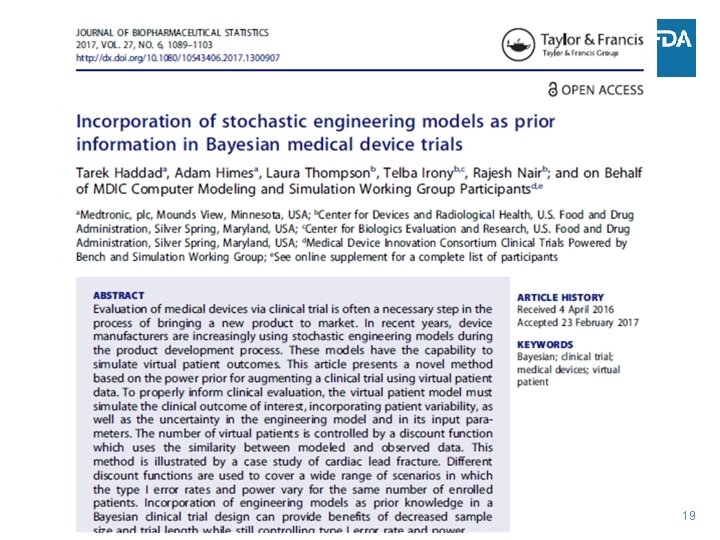

19

Challenges with Q/IDEs Submissions with Bayesian Design • A trial with Bayesian design needs more input from the agency at the beginning stage: adequacy of prior information and how much can be borrowed. • Analysis with Bayesian design often involves customized coding – leading to spending more time on writing (sponsor) and checking (FDA) the codes • Parameters in the statistical model may often change based on the Agency’s input on the winning rule and desired operating characteristics. 20

Stage/Step-Wise Submission Is Recommended • The high level features of a protocol should be discussed before the statistical details are proposed. • For complex statistical model, thorough communication between sponsor and FDA is needed to clearly understand the clinical implication of the model. • Programs and simulation codes should be started after the statistical model is agreed with FDA to avoid repetitive work. 21

Stage I (preliminary) 1 a) Determine the primary endpoint(s) and other parameters of clinical significance for study design – Treatment arms – Primary endpoints – Inclusion exclusion criteria – Follow-up schedule – Types of stopping rule – prior information (external control-historical, concurrent registry data) – Adequacy of prior 1 b) Amount and methods of borrowing – The maximum amount of prior information to borrow and new information needed – Proposal for borrowing methods (power prior, hierarchical model and others) – Winning criteria (threshold for the posterior probability) 22

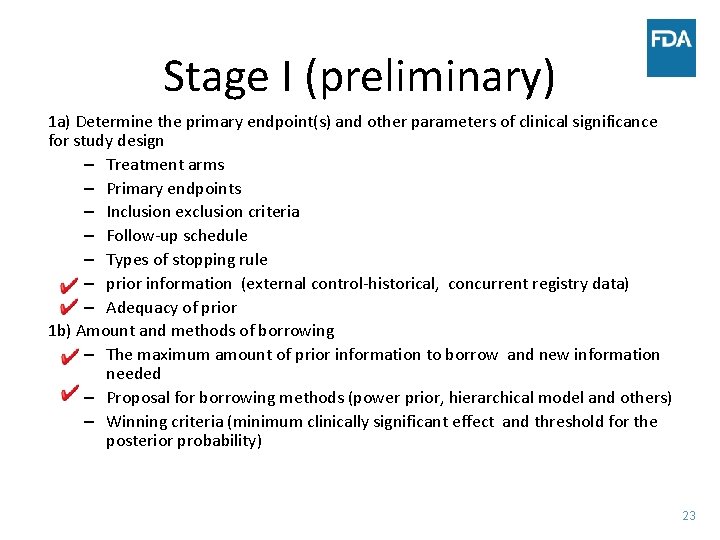

Stage I (preliminary) 1 a) Determine the primary endpoint(s) and other parameters of clinical significance for study design – Treatment arms – Primary endpoints – Inclusion exclusion criteria – Follow-up schedule – Types of stopping rule – prior information (external control-historical, concurrent registry data) – Adequacy of prior 1 b) Amount and methods of borrowing – The maximum amount of prior information to borrow and new information needed – Proposal for borrowing methods (power prior, hierarchical model and others) – Winning criteria (minimum clinically significant effect and threshold for the posterior probability) 23

Stage II (detailed) 2 a) • Simulation algorithm for obtaining the posterior distribution • Write module of codes for simulation – Trustable/standard software or packages – Well organized with annotated codes – Displaying intermediate output with mock data can improve readability • Other statistical aspects such as analyses population, handling of missing data, multiplicity issues, poolability of data 2 b) • Evaluate operating characteristics based on different design parameters and stopping rules – Type I error rate, power, probability of success/futility at interim analyses • Fix design parameters and stopping rule to meet desired design properties from clinical, statistical and regularity points of view. 24

Stage II (detailed) 2 a) • Simulation algorithm for obtaining the posterior distribution • Write module of codes for simulation – Trustable/standard software or packages – Well organized with annotated codes – Displaying intermediate output with mock data can improve readability • Other statistical aspects such as analyses population, handling of missing data, multiplicity issues, poolability of data 2 b) • Evaluate operating characteristics based on different design parameters and stopping rules – Type I error rate, power, probability of success/futility at interim analyses • Fix design parameters and stopping rule to meet desired design properties from clinical, statistical and regularity points of view. 25

Summary and Conclusions • Bayesian method is a useful approach in combining prior information and current information to make a inference for the treatment effect, especially in medical device trials. • Prior planning of the design and analyses is crucial. • What to borrow and how much to borrow depend on clinical, statistical and regulatory considerations. 26

Summary and Conclusions (cont. ) • Cherry picking prior information could lead to a biased inference if the Bayesian model does not take into account the relationship between the selected prior information and rest of the available data. • Extra effort is needed in communicating with the Agency due to the challenges with Bayesian design: – Decision on what and how much to borrow – The choice of Bayesian model – Complexity in writing and validating the code for analysis and simulation • Stage/step-wise submission is recommended to avoid repetitive work. 27

Acknowledgement Thanks to my colleagues Ram Tiwari, Yun-Ling Xu, and Sherry Yan for their valuable contributions to this presentation 28

Back-up Slides 29

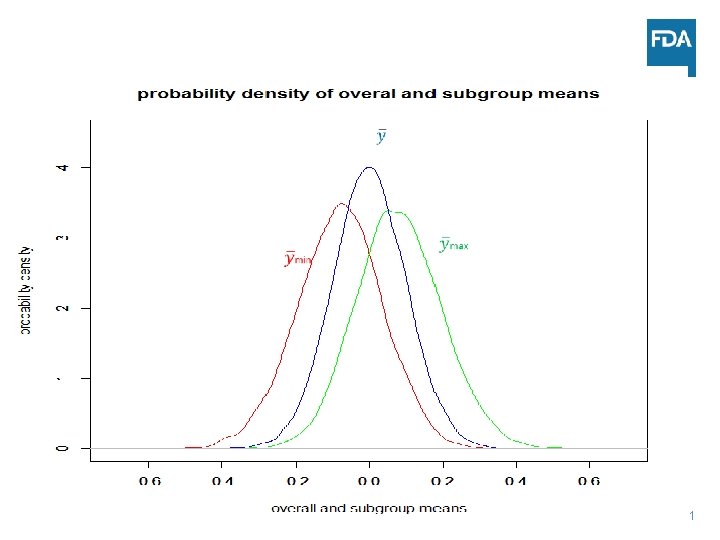

Choosing the More Promising Subgroup: Two Subgroups Situation • Paired design n=100. • Sham vehicle applied to both eyes • For each subgroup, randomly dissect the sample into two subgroups with equal number ni=50 • Yi iid ~ N(0, 1) • Group with the higher mean ymax selected as the promising group 30

31

Statistical Considerations • Biased prior information for treatment effect µmax~0. 1 • Chance of identifying a subgroup with statistical significance is 5% (number of independent subgroups x 2. 5%) instead of 2. 5% for a non-effective device • Risk of wasting resource due to the regression to the mean effect • Both groups A and Ac need to be weighed equally to correct the bias 32

- Slides: 32