Boolean Algebra Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications Baojian

Boolean Algebra Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications Baojian Hua bjhua@ustc. edu. cn

Outline n n Data representation Program execution Final goal: Design your own CPU n programming assignment #5

Number System n Decimal n digit 0~9 n n Binary n digit 0 or 1 n n Ex: 21 Ex: 00010101 (8 -bit representation of 21) Hexadecimal n digit 0~9, letter a~f n Ex: 15 h (or 0 x 15)

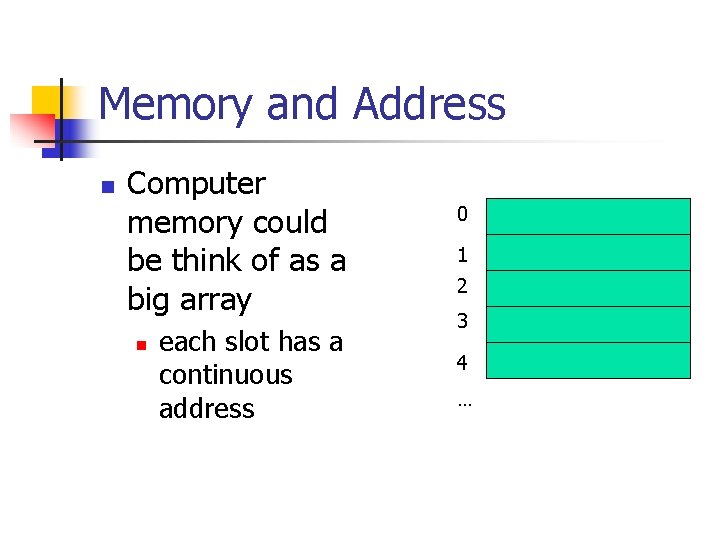

Memory and Address n Computer memory could be think of as a big array

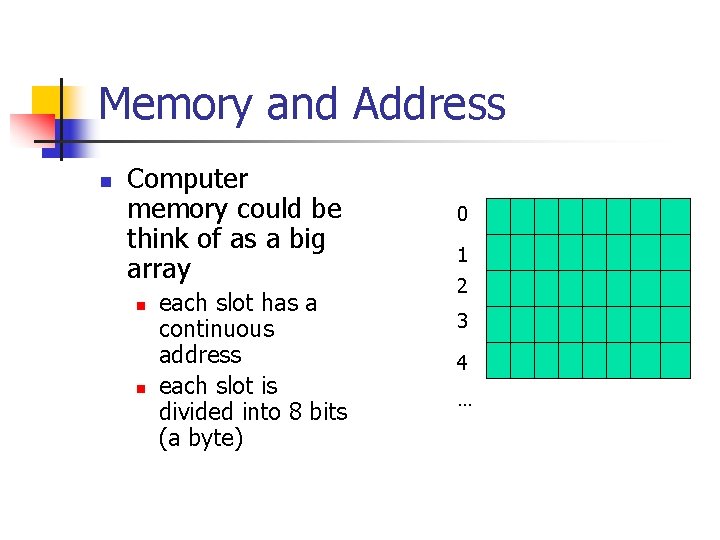

Memory and Address n Computer memory could be think of as a big array n each slot has a continuous address 0 1 2 3 4 …

Memory and Address n Computer memory could be think of as a big array n n each slot has a continuous address each slot is divided into 8 bits (a byte) 0 1 2 3 4 …

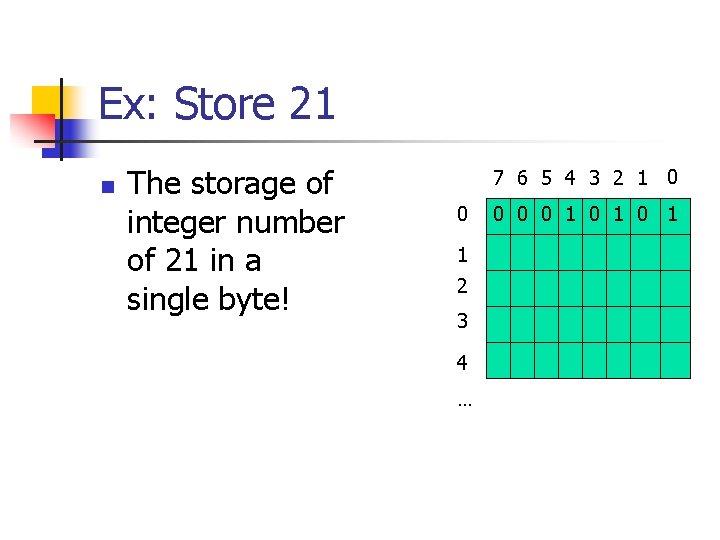

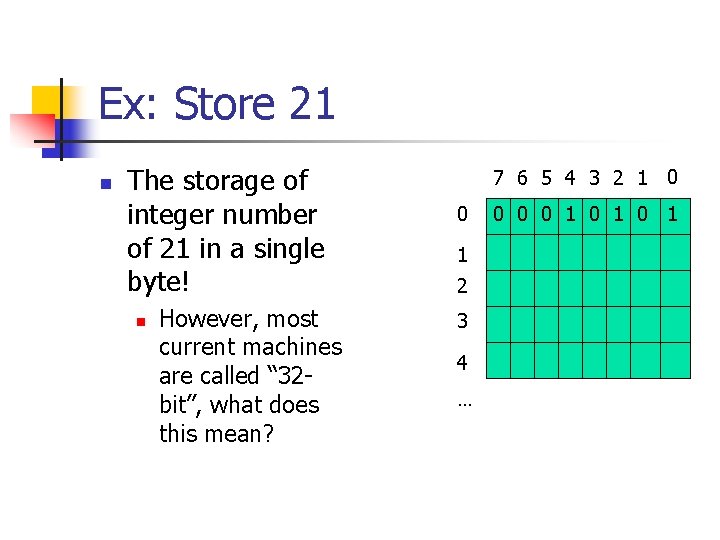

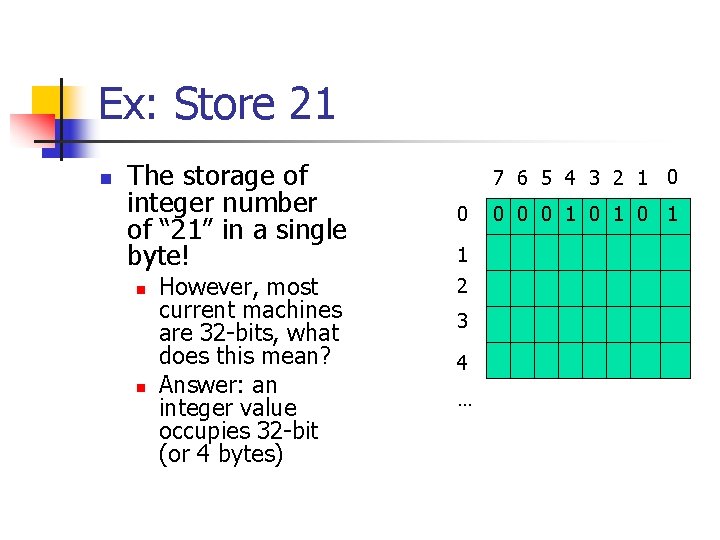

Ex: Store 21 n The storage of integer number of 21 in a single byte! 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 0 1 2 3 4 … 0 0 0 1 0 1

Ex: Store 21 n The storage of integer number of 21 in a single byte! n However, most current machines are called “ 32 bit”, what does this mean? 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 0 1 2 3 4 … 0 0 0 1 0 1

Ex: Store 21 n The storage of integer number of “ 21” in a single byte! n n However, most current machines are 32 -bits, what does this mean? Answer: an integer value occupies 32 -bit (or 4 bytes) 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 0 1 2 3 4 … 0 0 0 1 0 1

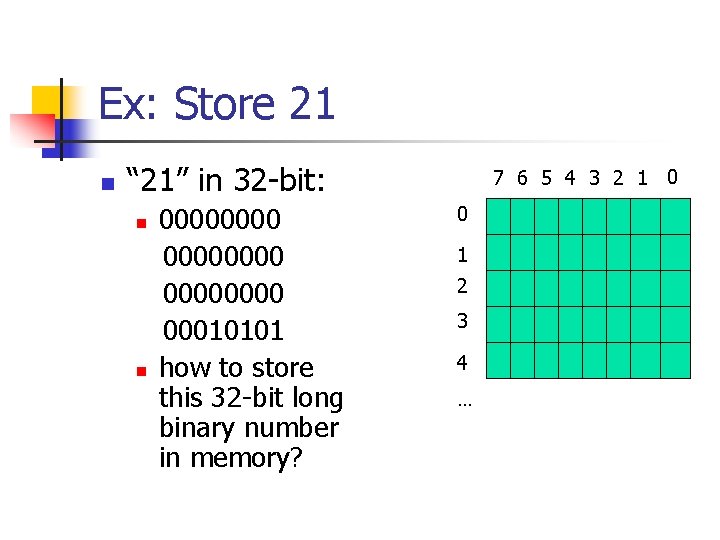

Ex: Store 21 n “ 21” in 32 -bit: n n 00000000 00010101 how to store this 32 -bit long binary number in memory? 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 0 1 2 3 4 …

Big-endian and Little-endian n n Big-endian and little-endian are named after the convention of storing multibyte data in memory Big-endian: most-significant byte at low address n n Ex: Sun Sparc Little-endian: reverse n Ex: Pentium

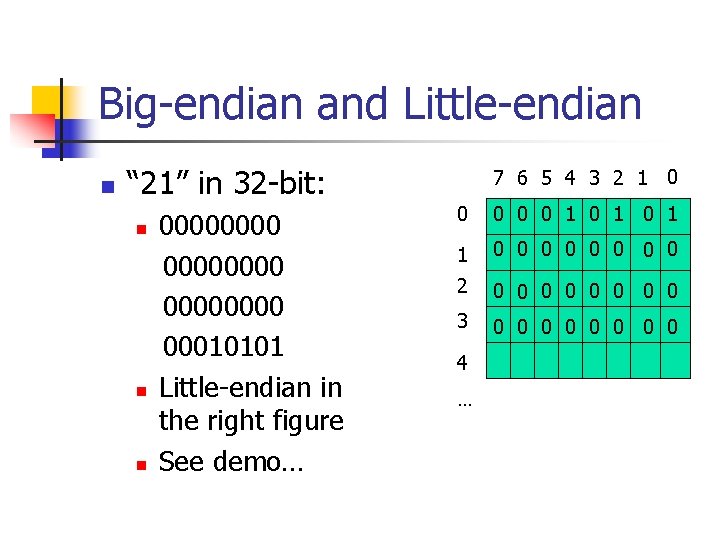

Big-endian and Little-endian n “ 21” in 32 -bit: n n n 00000000 00010101 Little-endian in the right figure See demo… 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 0 0 3 0 0 0 0 4 …

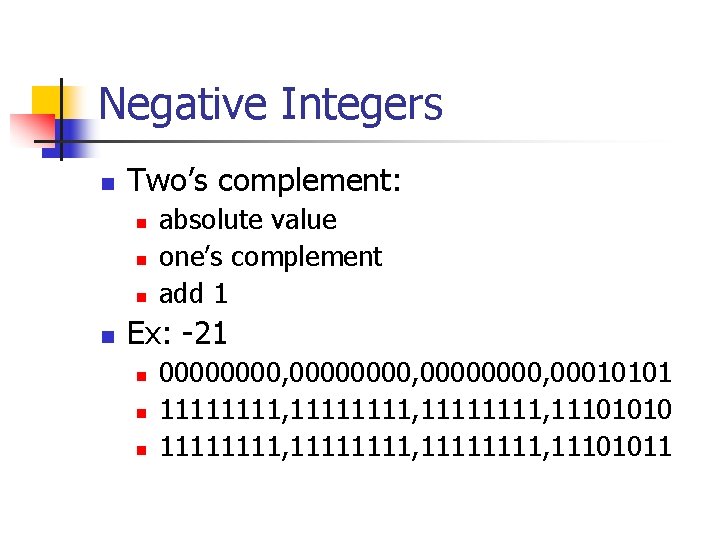

Negative Integers n Two’s complement: n n absolute value one’s complement add 1 Ex: -21 n n n 00000000, 00010101 11111111, 11101010 11111111, 11101011

Moral: Data in Machine n Data at the machine level has no assumed meaning n n n Slogan: meaning = bits + context n n n Ex: 1111 255? or -1? or …? bits: the data context: how this data is interpreted used We’d see more exciting examples below

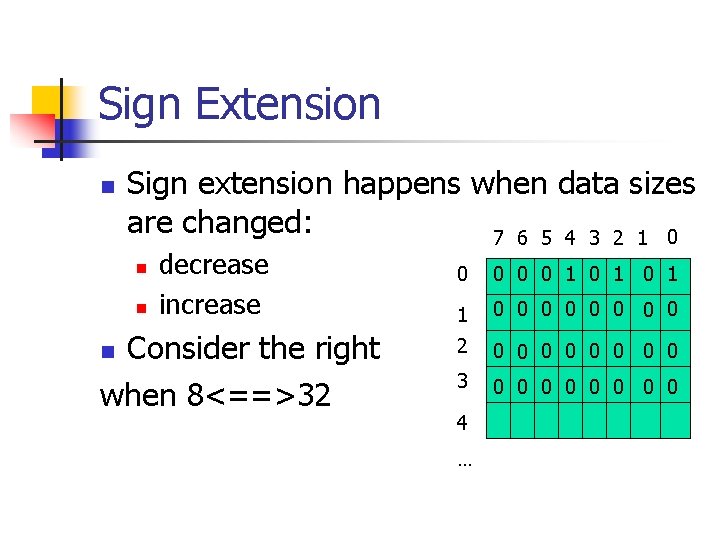

Sign Extension n Sign extension happens when data sizes are changed: 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 n n decrease increase Consider the right when 8<==>32 n 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 0 0 3 0 0 0 0 4 …

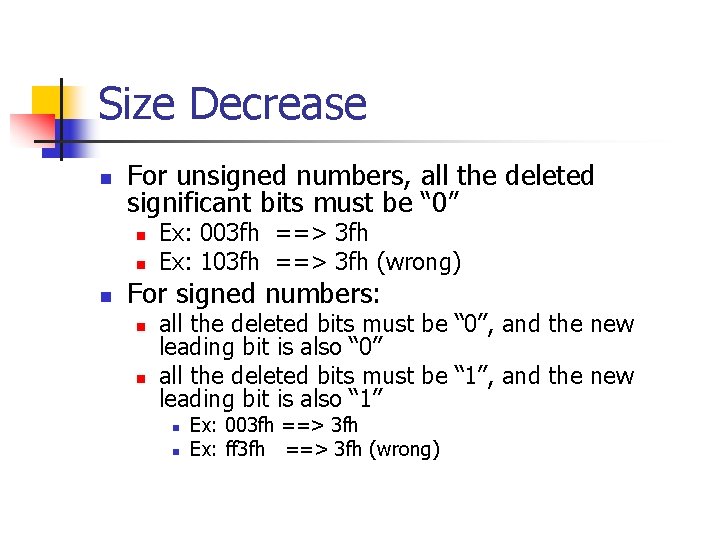

Size Decrease n For unsigned numbers, all the deleted significant bits must be “ 0” n n n Ex: 003 fh ==> 3 fh Ex: 103 fh ==> 3 fh (wrong) For signed numbers: n n all the deleted bits must be “ 0”, and the new leading bit is also “ 0” all the deleted bits must be “ 1”, and the new leading bit is also “ 1” n n Ex: 003 fh ==> 3 fh Ex: ff 3 fh ==> 3 fh (wrong)

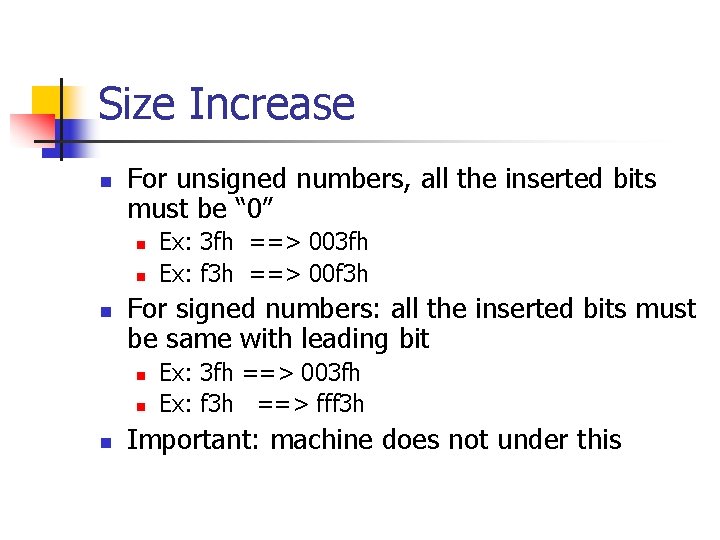

Size Increase n For unsigned numbers, all the inserted bits must be “ 0” n n n For signed numbers: all the inserted bits must be same with leading bit n n n Ex: 3 fh ==> 003 fh Ex: f 3 h ==> 00 f 3 h Ex: 3 fh ==> 003 fh Ex: f 3 h ==> fff 3 h Important: machine does not under this

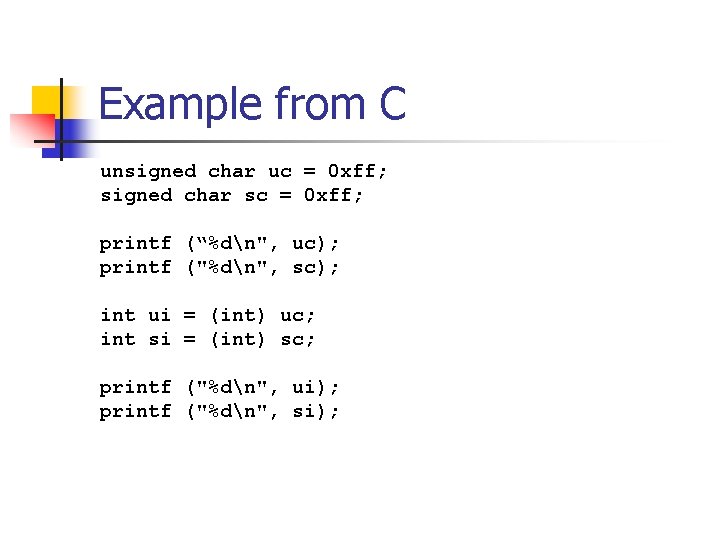

Example from C unsigned char uc = 0 xff; signed char sc = 0 xff; printf (“%dn", uc); printf ("%dn", sc); int ui = (int) uc; int si = (int) sc; printf ("%dn", ui); printf ("%dn", si);

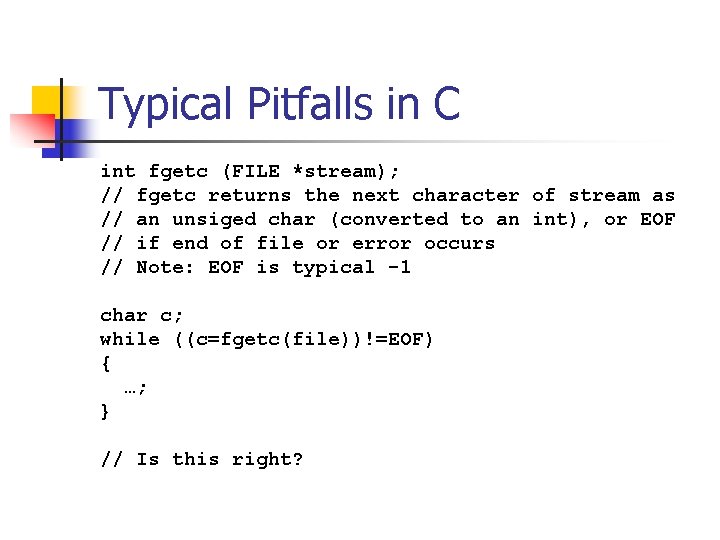

Typical Pitfalls in C int fgetc (FILE *stream); // fgetc returns the next character of stream as // an unsiged char (converted to an int), or EOF // if end of file or error occurs // Note: EOF is typical -1 char c; while ((c=fgetc(file))!=EOF) { …; } // Is this right?

Program Representation n What the binary form of program look like? n n n A program in binary form is also just a series of 0 and 1 (as we expect) typical in readable and friendly assembly form next, we turn back to our mini. Pentium language in programming assignment #2

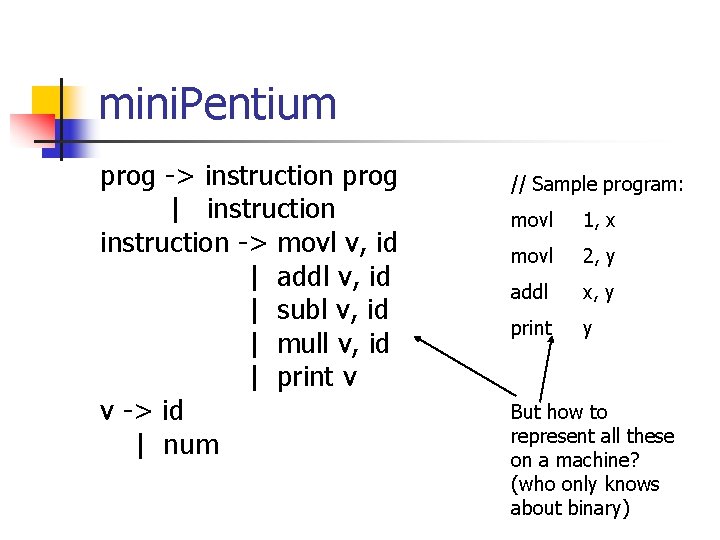

mini. Pentium prog -> instruction prog | instruction -> movl v, id | addl v, id | subl v, id | mull v, id | print v v -> id | num // Sample program: movl 1, x movl 2, y addl x, y print y But how to represent all these on a machine? (who only knows about binary)

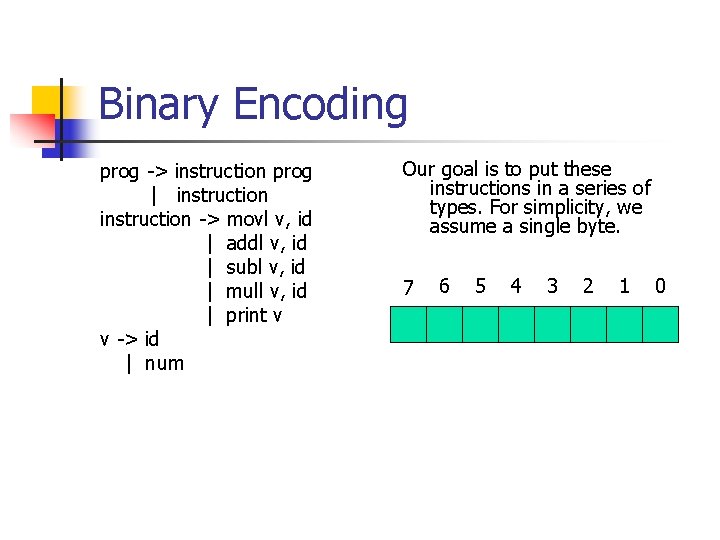

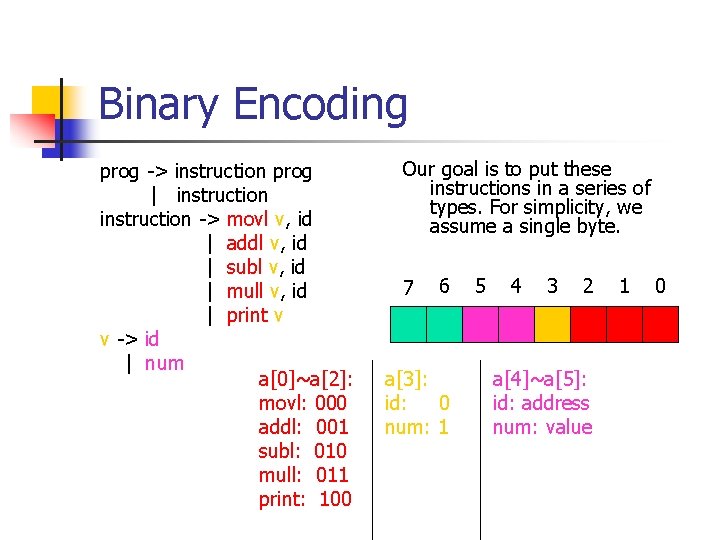

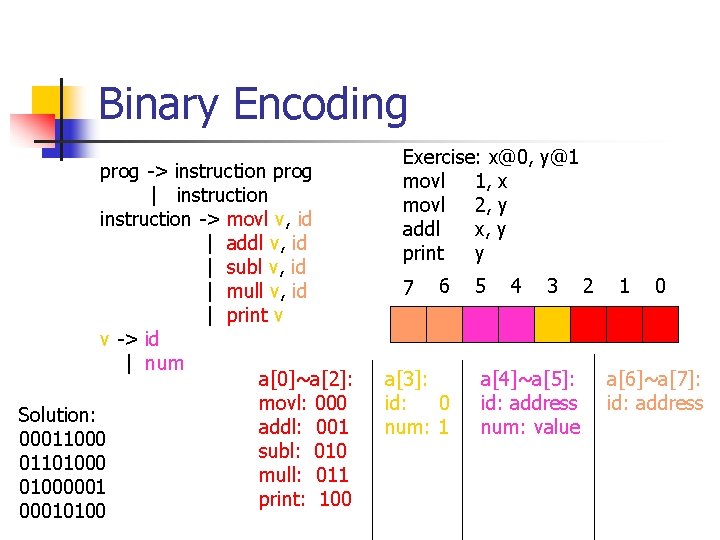

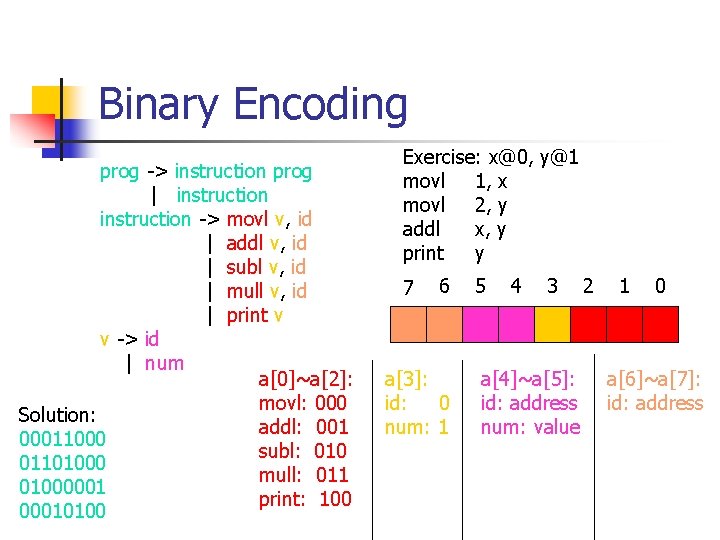

Binary Encoding prog -> instruction prog | instruction -> movl v, id | addl v, id | subl v, id | mull v, id | print v v -> id | num Our goal is to put these instructions in a series of types. For simplicity, we assume a single byte. 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0

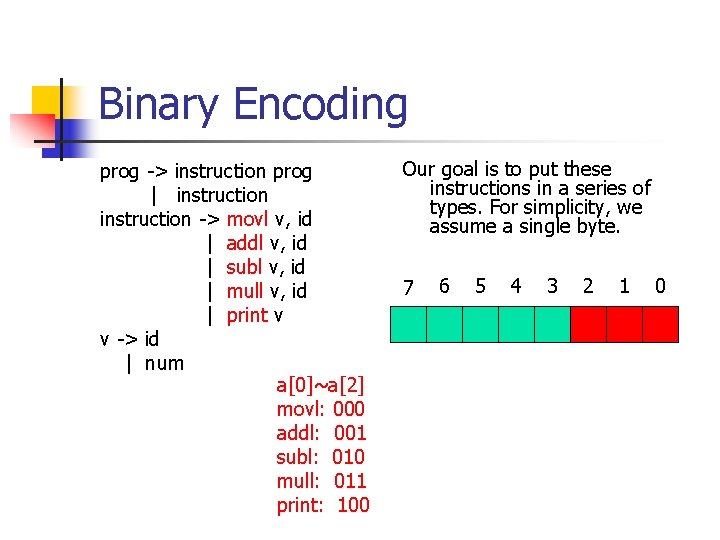

Binary Encoding prog -> instruction prog | instruction -> movl v, id | addl v, id | subl v, id | mull v, id | print v v -> id | num a[0]~a[2] movl: 000 addl: 001 subl: 010 mull: 011 print: 100 Our goal is to put these instructions in a series of types. For simplicity, we assume a single byte. 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0

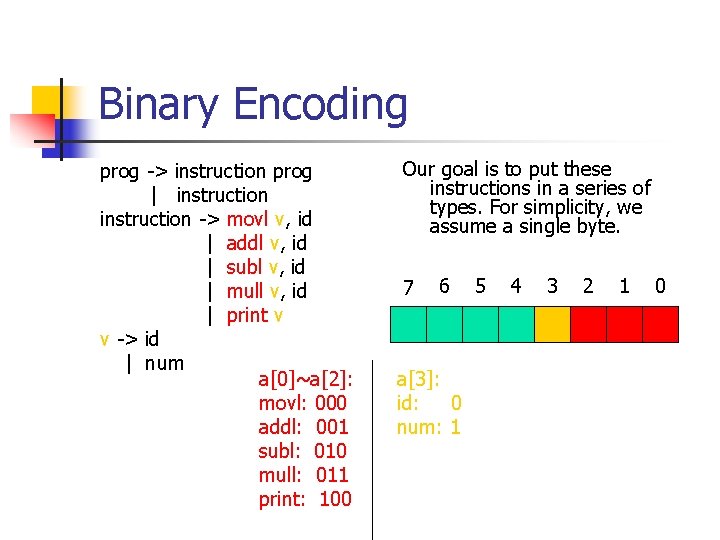

Binary Encoding prog -> instruction prog | instruction -> movl v, id | addl v, id | subl v, id | mull v, id | print v v -> id | num a[0]~a[2]: movl: 000 addl: 001 subl: 010 mull: 011 print: 100 Our goal is to put these instructions in a series of types. For simplicity, we assume a single byte. 7 6 a[3]: id: 0 num: 1 5 4 3 2 1 0

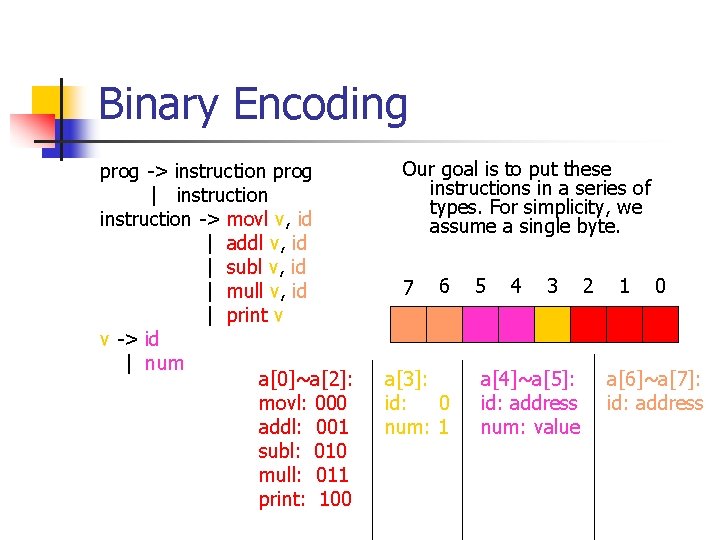

Binary Encoding prog -> instruction prog | instruction -> movl v, id | addl v, id | subl v, id | mull v, id | print v v -> id | num a[0]~a[2]: movl: 000 addl: 001 subl: 010 mull: 011 print: 100 Our goal is to put these instructions in a series of types. For simplicity, we assume a single byte. 7 6 a[3]: id: 0 num: 1 5 4 3 2 a[4]~a[5]: id: address num: value 1 0

Binary Encoding prog -> instruction prog | instruction -> movl v, id | addl v, id | subl v, id | mull v, id | print v v -> id | num a[0]~a[2]: movl: 000 addl: 001 subl: 010 mull: 011 print: 100 Our goal is to put these instructions in a series of types. For simplicity, we assume a single byte. 7 6 a[3]: id: 0 num: 1 5 4 3 a[4]~a[5]: id: address num: value 2 1 0 a[6]~a[7]: id: address

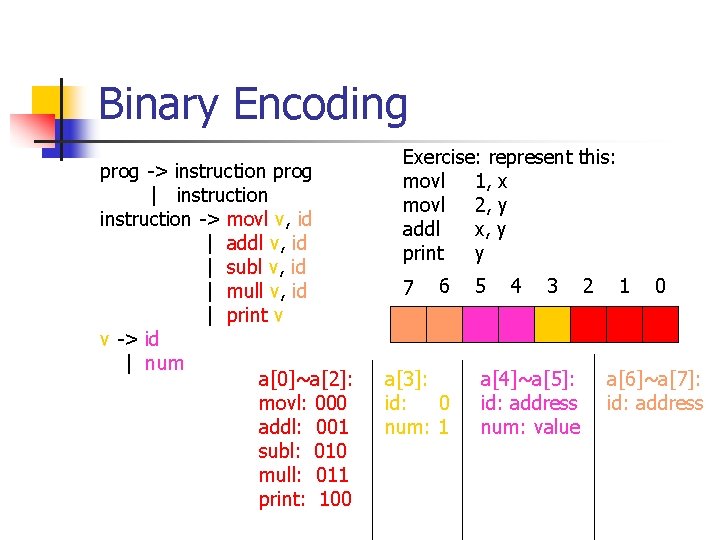

Binary Encoding prog -> instruction prog | instruction -> movl v, id | addl v, id | subl v, id | mull v, id | print v v -> id | num a[0]~a[2]: movl: 000 addl: 001 subl: 010 mull: 011 print: 100 Exercise: represent this: movl 1, x movl 2, y addl x, y print y 7 6 a[3]: id: 0 num: 1 5 4 3 a[4]~a[5]: id: address num: value 2 1 0 a[6]~a[7]: id: address

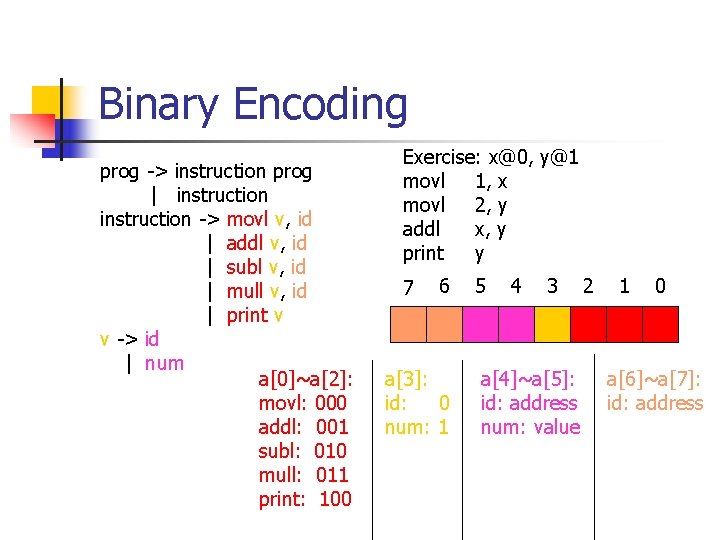

Binary Encoding prog -> instruction prog | instruction -> movl v, id | addl v, id | subl v, id | mull v, id | print v v -> id | num a[0]~a[2]: movl: 000 addl: 001 subl: 010 mull: 011 print: 100 Exercise: x@0, y@1 movl 1, x movl 2, y addl x, y print y 7 6 a[3]: id: 0 num: 1 5 4 3 a[4]~a[5]: id: address num: value 2 1 0 a[6]~a[7]: id: address

Binary Encoding prog -> instruction prog | instruction -> movl v, id | addl v, id | subl v, id | mull v, id | print v v -> id | num a[0]~a[2]: movl: 000 Solution: addl: 001 00011000 subl: 010 01101000 mull: 011 01000001 print: 100 00010100 Exercise: x@0, y@1 movl 1, x movl 2, y addl x, y print y 7 6 a[3]: id: 0 num: 1 5 4 3 a[4]~a[5]: id: address num: value 2 1 0 a[6]~a[7]: id: address

Binary Encoding prog -> instruction prog | instruction -> movl v, id | addl v, id | subl v, id | mull v, id | print v v -> id | num a[0]~a[2]: movl: 000 Solution: addl: 001 00011000 subl: 010 01101000 mull: 011 01000001 print: 100 00010100 Exercise: x@0, y@1 movl 1, x movl 2, y addl x, y print y 7 6 a[3]: id: 0 num: 1 5 4 3 a[4]~a[5]: id: address num: value 2 1 0 a[6]~a[7]: id: address

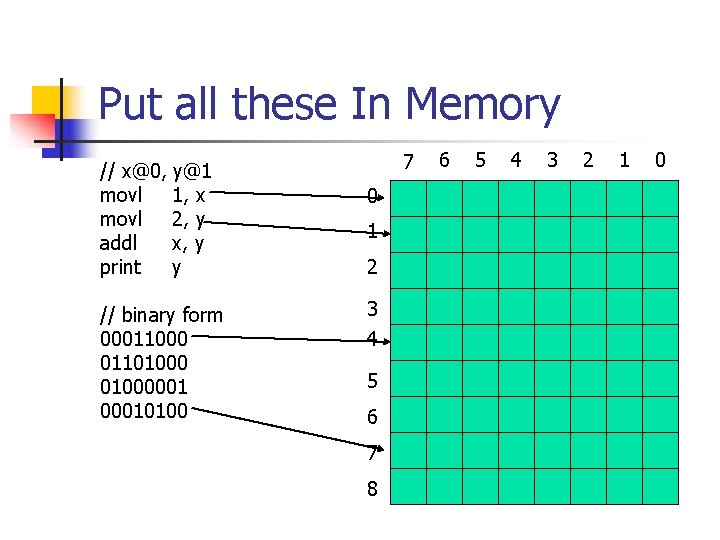

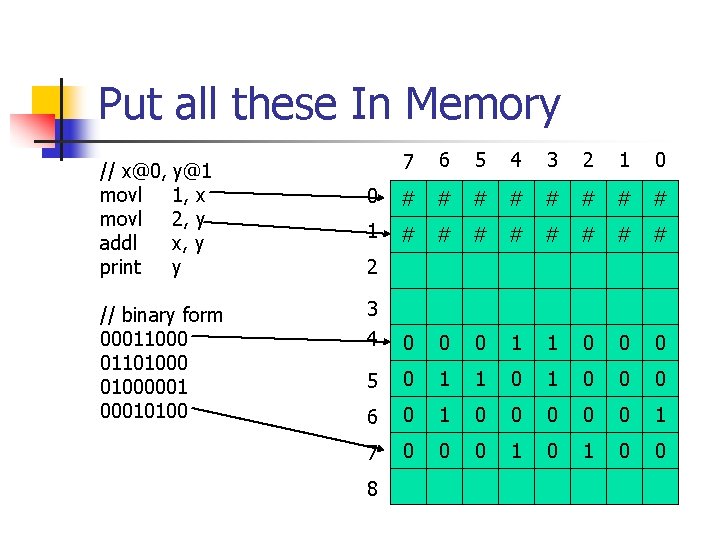

Put all these In Memory // x@0, y@1 movl 1, x movl 2, y addl x, y print y // binary form 00011000 01101000001 00010100 7 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 6 5 4 3 2 1 0

Put all these In Memory // x@0, y@1 movl 1, x movl 2, y addl x, y print y // binary form 00011000 01101000001 00010100 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 0 # # # # 1 # # # # 3 4 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 5 0 1 1 0 0 0 6 0 1 0 0 0 1 7 0 0 0 1 0 0 2 8

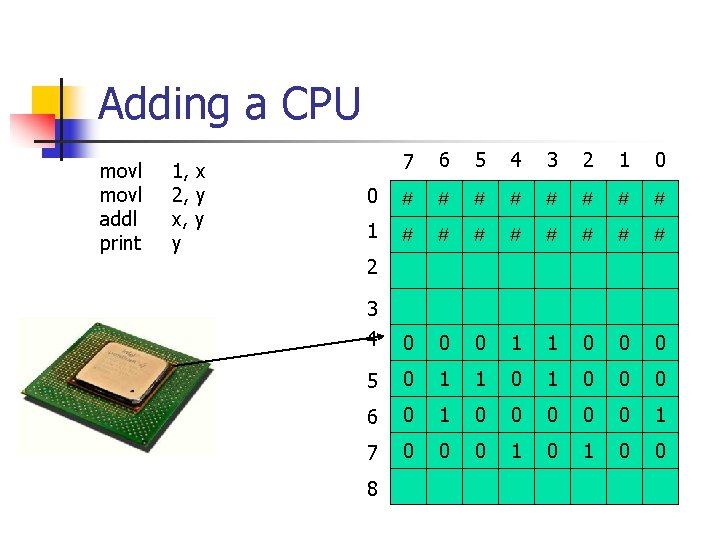

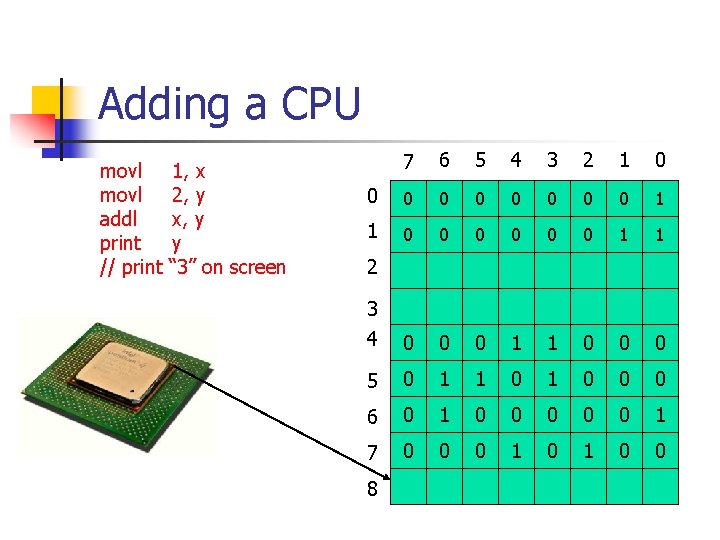

Adding a CPU movl addl print 1, x 2, y x, y y 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 0 # # # # 1 # # # # 3 4 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 5 0 1 1 0 0 0 6 0 1 0 0 0 1 7 0 0 0 1 0 0 2 8

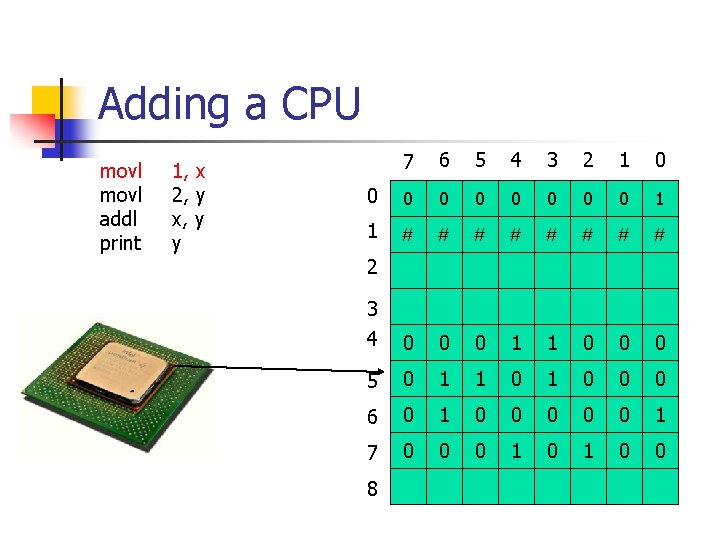

Adding a CPU movl addl print 1, x 2, y x, y y 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 # # # # 3 4 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 5 0 1 1 0 0 0 6 0 1 0 0 0 1 7 0 0 0 1 0 0 2 8

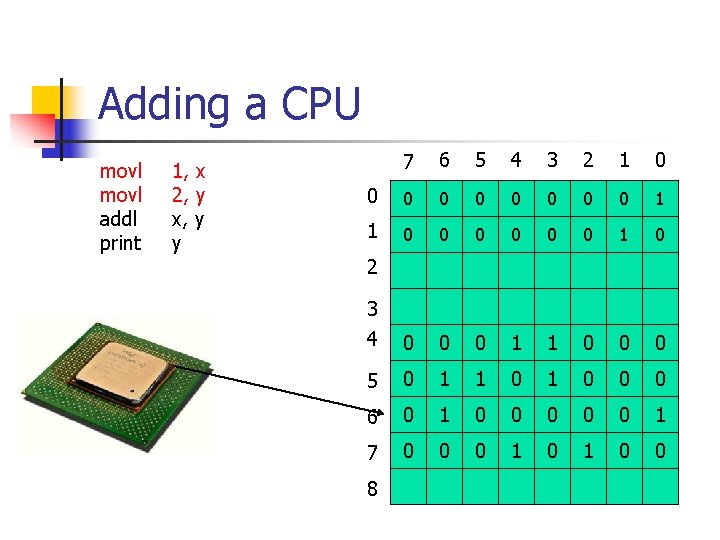

Adding a CPU movl addl print 1, x 2, y x, y y 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 3 4 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 5 0 1 1 0 0 0 6 0 1 0 0 0 1 7 0 0 0 1 0 0 2 8

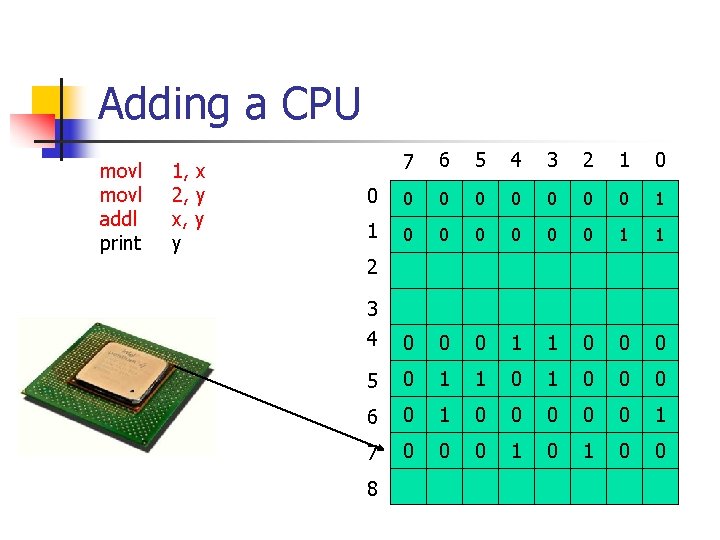

Adding a CPU movl addl print 1, x 2, y x, y y 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 3 4 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 5 0 1 1 0 0 0 6 0 1 0 0 0 1 7 0 0 0 1 0 0 2 8

Adding a CPU movl addl print // print 1, x 2, y x, y y “ 3” on screen 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 3 4 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 5 0 1 1 0 0 0 6 0 1 0 0 0 1 7 0 0 0 1 0 0 2 8

Some Real World Issues n The binary encoding strategy for mini. Pentium discussed above is far from real Pentium n n n Pentium is 32 -bit instruction is of variant-length (1 -6 bytes) more complex addressing mode abundant instructions (700+ pages) … However, the key idea is essential

CISC and RISC n Complex Instruction Set Computer: n n designed in 60’-70’ last century popular in desktop applications Ex: Intel’ Pentium Reduced Instruction Set Computer: n n n Uniform instruction representation (just as we’ve done for mini. Pentium) relatively few instructions (<100) simple addressing mode designed from 80’, popular in embedded area Ex: MIPS, ARM, etc

Programming Assignment #4: CPU Design and Implementation n n Design a binary encoding strategy to encode the mini. Pentium (in 32 -bit) Use your favorite language, implement the memory. Make the following assumption to simplify your life: n n integers unsigned memory infinite data and program isolated Write a function to make your CPU run n write some test programs (binaries by hand)

Programming Assignment #4: CPU Design and Implementation n Connect your CPU with the mini. VC compiler in the programming assignment #3 n n write programs in mini. C mini. VC compiles mini. C to mimi. Pentium write an assembler assembles into binaries run your CPU

- Slides: 41