Blockchains Lecture 3 Cryptography historically the art of

Blockchains Lecture 3

Cryptography (historically) “…the art of writing or solving codes…” • Historically, cryptography focused exclusively on ensuring private communication between two parties sharing secret information in advance (using “codes” aka private-key encryption)

Modern cryptography • Much broader scope! – Data integrity, authentication, protocols, … – The public-key setting – Group communication – More-complicated trust models – Foundations (e. g. , number theory, quantumresistance) to systems (e. g. , electronic voting, cryptocurrencies)

Modern cryptography Design, analysis, and implementation of mathematical techniques for securing information, systems, and distributed computations against adversarial attack

Modern cryptography • Cryptography is ubiquitous – Passwords, password hashing – Secure credit-card transactions over the internet – Encrypted Wi. Fi – Disk encryption – Digitally signed software updates – Bitcoin –…

Rough course outline Secrecy Integrity Private-key setting Private-key encryption Message authentication codes Public-key setting Public-key encryption Digital signatures • Building blocks – Pseudorandom functions/block ciphers (AES) – Hash functions (SHA) – Number theory (RSA, Diffie-Hellman, Discrete Logarithm, Elliptic Curve, LWE)

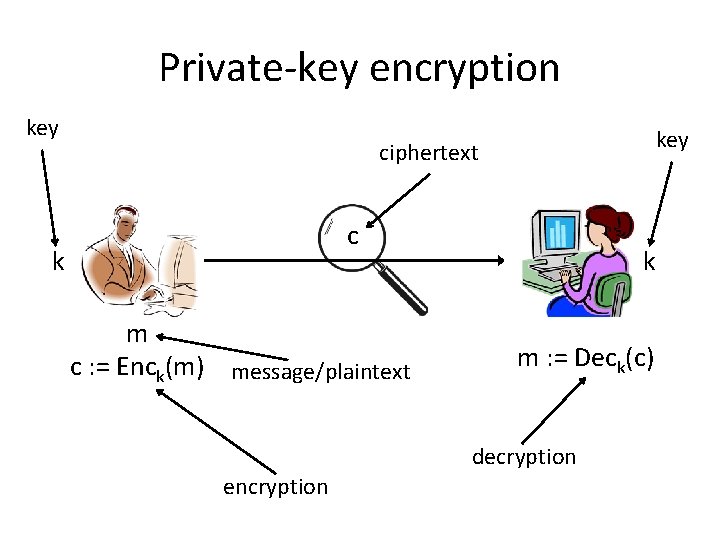

Private-key encryption key ciphertext c k m c : = Enck(m) message/plaintext k m : = Deck(c) decryption encryption

Private-key encryption k c m c : = Enck(m) c c k m : = Deck(c)

Private-key encryption • A private-key encryption scheme is defined by a message space M and algorithms (Gen, Enc, Dec): – Gen (key-generation algorithm): outputs k K – Enc (encryption algorithm): takes key k and message m M as input; outputs ciphertext c c Enck(m) – Dec (decryption algorithm): takes key k and ciphertext c as input; outputs m or “error” m : = Deck(c) For all m M and k output by Gen, Deck(Enck(m)) = m

CPA-security c 21 k m cc 12 Enck(m (m)12) m 21 k

Is the threat model too strong? • In practice, there are many ways an attacker can influence what gets encrypted – Not clear how best to model – Chosen-plaintext attacks encompass any such influence • Moreover, in some cases an attacker may have significant control over what gets encrypted

“Midway” AFWill is short attack of AF water… … Help! Fresh water needed Midway Island For more details, see: http: //www. navy. mil/midway/how. html

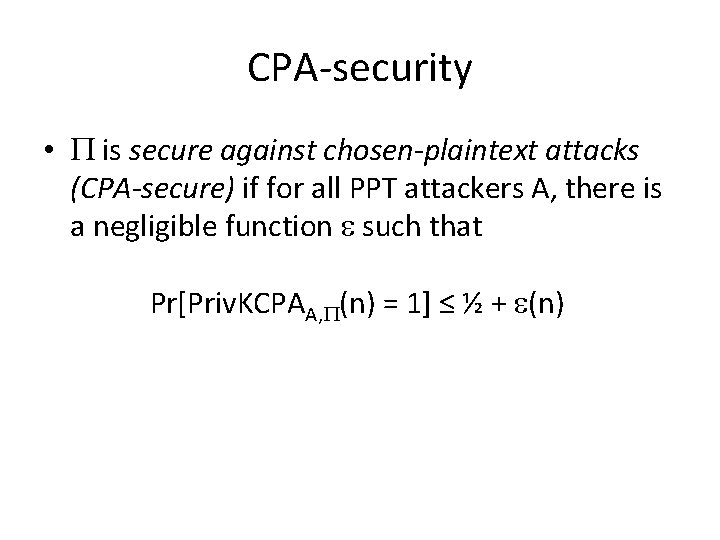

CPA-security • Fix , A • Define a randomized exp’t Priv. KCPAA, (n): 1. k Gen(1 n) 2. A(1 n) interacts with an encryption oracle Enck(·), and then outputs m 0, m 1 of the same length 3. b {0, 1}, c Enck(mb), give c to A 4. A can continue to interact with Enck(·) 5. A outputs b’; A succeeds if b = b’, and experiment evaluates to 1 in this case

CPA-security • is secure against chosen-plaintext attacks (CPA-secure) if for all PPT attackers A, there is a negligible function such that Pr[Priv. KCPAA, (n) = 1] ≤ ½ + (n)

Encryption Has to be Randomized • This attack is easy if encryption is deterministic – Moral: randomized encryption must be used!

Randomized encryption • The issue is not an artifact of our definition – It really is a problem if an attacker can tell when the same message is encrypted twice

Pseudorandom functions (AES)

Pseudorandom functions (AES) • Informally, a pseudorandom function “looks like” a random (i. e. , uniform) function • Deterministic

CBC-mode encryption IV c 0 m 1 m 2 ml Fk Fk c 1 c 2 … Fk cl 19

CBC-mode decryption c 0 m 1 m 2 ml F-1 k c 1 c 2 … F-1 k cl 20

Message integrity

Secrecy vs. integrity • So far we have been concerned with ensuring secrecy of communication • What about integrity? – I. e. , ensuring that a received message originated from the intended party, and was not modified • Even if an attacker controls the channel! – Standard error-correction techniques not enough! • The right tool is a message authentication code

m, t k m t = Mack(m) m’, t’ k Vrfyk(m’, t’) = 1?

m, t k k m

k m, t k Vrfyk(m, t)=1?

…price=10… k cookie, t k cookie

Secrecy vs. integrity • Secrecy and integrity are orthogonal concerns – Possible to have either one without the other – Sometimes you might want one without the other – Most often, both are needed • Encryption does not (in general) provide any integrity – Integrity is even stronger than non-malleability – None of the schemes we have seen so far provide any integrity

Message authentication code (MAC) • A message authentication code is defined by three PPT algorithms (Gen, Mac, Vrfy): – Gen: takes as input 1 n; outputs k. (Assume |k|≥n. ) – Mac: takes as input key k and message m {0, 1}*; outputs tag t t : = Mack(m) – Vrfy: takes key k, message m, and tag t as input; outputs. For 1 (“accept”) or 0 k output (“reject”) all m and all by Gen, Vrfyk(m, Mack(m)) = 1

Security? • Only one standard definition • Threat model – “Adaptive chosen-message attack” – Assume the attacker can induce the sender to authenticate messages of the attacker’s choice • Security goal – “Existential unforgeability” – Attacker should be unable to forge a valid tag on any message not previously authenticated by the sender

m 1, t 1 : = Mack(m 1) t 2 : = Mack(m 2) … ti : = Mack(mi) m 2, t 2 … k m i, t i m’, t’ k Vrfyk(m’, t’) ? ?

(Basic) CBC-MAC Does Not Work m 1 Fk m 2 ml Fk … Fk t

CBC-MAC vs. CBC-mode • CBC-MAC is deterministic (no IV) – MACs do not need to be randomized to be secure – Verification is done by re-computing the result • In CBC-MAC, only the final value is output • Both are essential for security – Exercise: show attacks

CBC-MAC extensions Work • Several ways to handle variable-length messages • One of the simplest: prepend the message length before applying (basic) CBC-MAC

CBC-MAC (l is the length of blocks) l Fk m 1 m 2 ml Fk Fk … Fk t

A More Popular One, However • HMAC • A MAC based on hash function

Acknowledgement • Many of the slides (and also slides for the following two lectures) from Jonathon Katz (UMD). • These slides are also simplified ones from my last semester’s offering.

- Slides: 36