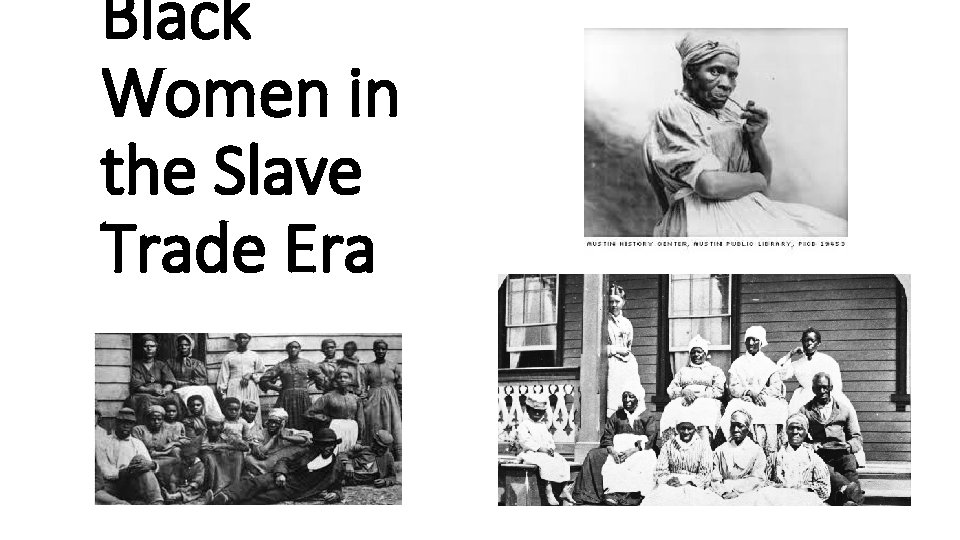

Black Women in the Slave Trade Era Background

Black Women in the Slave Trade Era

Background of the Slave Trade • The slave trade refers to the transatlantic trading patterns which were established as early as the mid-17 th century. Trading ships would set sail from Europe with a cargo of manufactured goods to the west coast of Africa. There, these goods would be traded, over weeks and months, for captured people provided by African traders. European traders found it easier to do business with African intermediaries who raided settlements far away from the African coast and brought those young and healthy enough to the coast to be sold into slavery. • In 1807, the British government passed an Act of Parliament abolishing the slave trade throughout the British Empire. Slavery itself would persist in the British colonies until its final abolition in 1838. However, abolitionists would continue campaigning against the international trade of slaves after this date. • Those who supported the slave trade argued that it made important contributions to the country's economy and to the rise of consumerism in Britain. Despite this, towards the end of the eighteenth century, people began to campaign against slavery. However, since trading was so profitable for those involved, the 'Abolitionists' (those who campaigned for the abolition of the slave trade) were fiercely opposed by a proslavery West Indian Lobby. Those who still supported slavery used persuasive arguments, or 'propaganda', to indicate the necessity of the slave trade though the abolitionists also used propaganda to further their cause.

Women in the Slave Trade • For most women who endured it, the experience of the Atlantic slave trade was one of being outnumbered by men. Roughly one African woman was carried across the Atlantic for every two men. European slave traders preferred to buy men. The captains of slave ships were usually instructed to buy as high a proportion of men as they could, because men could be sold for more in the Americas. • Women thus arrived in the American colonies as a minority. For reasons we do not fully understand, they did not stay a minority. • Before abolitionism, slaveholders showed little interest in women as mothers. Their willingness to pay more for men than for women, despite the fact that any children born to enslaved women would also be the slaveowners' property and would thus increase their wealth, suggests that they preferred to buy new enslaved people from Africa rather than bear the costs of raising children. Women who did have children, therefore, always struggled with the impossible conflict between, on the own hand, their own physical needs and their children's need for care and, on the other, the requirements forced on them by plantation work regimes. Women's inability to maintain the pace of work required by plantation managers during pregnancy, their need for recovery time after childbirth, and the needs of their young children to be fed, cleaned, loved, and integrated spiritually and socially into the human community, all brought them into conflict with the demands of the owners and managers of the plantations on which they worked.

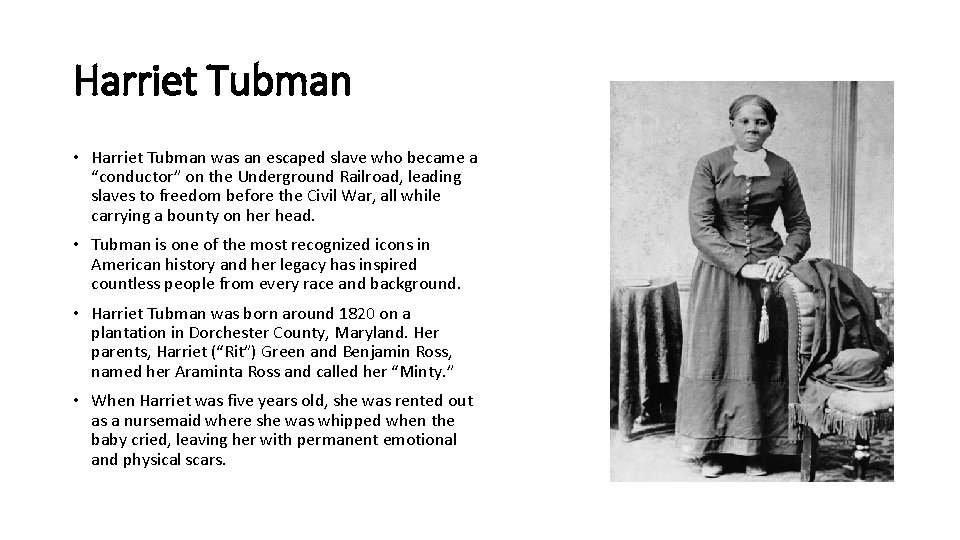

Harriet Tubman • Harriet Tubman was an escaped slave who became a “conductor” on the Underground Railroad, leading slaves to freedom before the Civil War, all while carrying a bounty on her head. • Tubman is one of the most recognized icons in American history and her legacy has inspired countless people from every race and background. • Harriet Tubman was born around 1820 on a plantation in Dorchester County, Maryland. Her parents, Harriet (“Rit”) Green and Benjamin Ross, named her Araminta Ross and called her “Minty. ” • When Harriet was five years old, she was rented out as a nursemaid where she was whipped when the baby cried, leaving her with permanent emotional and physical scars.

Harriet’s Escape from Slavery • Around 1844, Harriet married John Tubman, a free black man, and changed her last name from Ross to Tubman. The marriage was not good, and John threatened to sell Harriet further south. Her husband’s threat and the knowledge that two of her brothers—Ben and Henry—were about to be sold provoked Harriet to plan an escape. • On September 17, 1849, Harriet, Ben and Henry escaped their Maryland plantation. The brothers, however, changed their minds and went back. With the help of the Underground Railroad, Harriet persevered and traveled 90 miles north to Pennsylvania and freedom. • She soon returned to the south to lead her niece and her niece’s children to Philadelphia via the Underground Railroad. At one point, she tried to bring her husband John north, but he’d remarried and chose to stay in Maryland with his new wife. • The 1850 Fugitive Slave Act allowed fugitive and free slaves in the north to be captured and enslaved. This made Harriet’s job as an Underground Railroad conductor much harder and forced her to lead slaves further north to Canada, traveling at night, usually in the spring or fall when the days were shorter.

Harriet’s Liberation of Slaves • Over the next ten years, Harriet befriended other abolitionists such as Frederick Douglass, Thomas Garrett and Martha Coffin Wright, and established her own Underground Railroad network. It’s widely reported she emancipated 300 slaves; however, those numbers may have been estimated and exaggerated by her biographer Sarah Bradford, since Harriet herself claimed the numbers were much lower. • Nevertheless, it’s believed Harriet personally led at least 70 slaves to freedom, including her elderly parents, and instructed dozens of others on how to escape on their own. She claimed, “I never ran my train off the track and I never lost a passenger. ” • When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Harriet found new ways to fight slavery. She was recruited to assist fugitive slaves at Fort Monroe and worked as a nurse, cook and laundress. Harriet used her knowledge of herbal medicines to help treat sick soldiers and fugitive slaves. • In 1863, Harriet became head of an espionage and scout network for the Union Army. She provided crucial intelligence to Union commanders about Confederate Army supply routes and troops and helped liberate slaves to form black Union regiments.

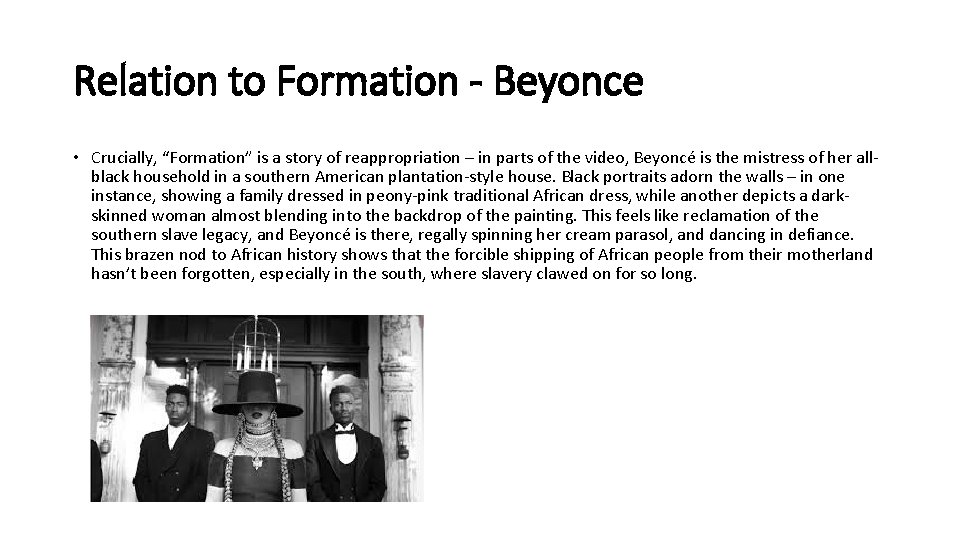

Relation to Formation - Beyonce • Crucially, “Formation” is a story of reappropriation – in parts of the video, Beyoncé is the mistress of her allblack household in a southern American plantation-style house. Black portraits adorn the walls – in one instance, showing a family dressed in peony-pink traditional African dress, while another depicts a darkskinned woman almost blending into the backdrop of the painting. This feels like reclamation of the southern slave legacy, and Beyoncé is there, regally spinning her cream parasol, and dancing in defiance. This brazen nod to African history shows that the forcible shipping of African people from their motherland hasn’t been forgotten, especially in the south, where slavery clawed on for so long.

- Slides: 7