Biophysical chemistry C 365 Understanding biological systems using

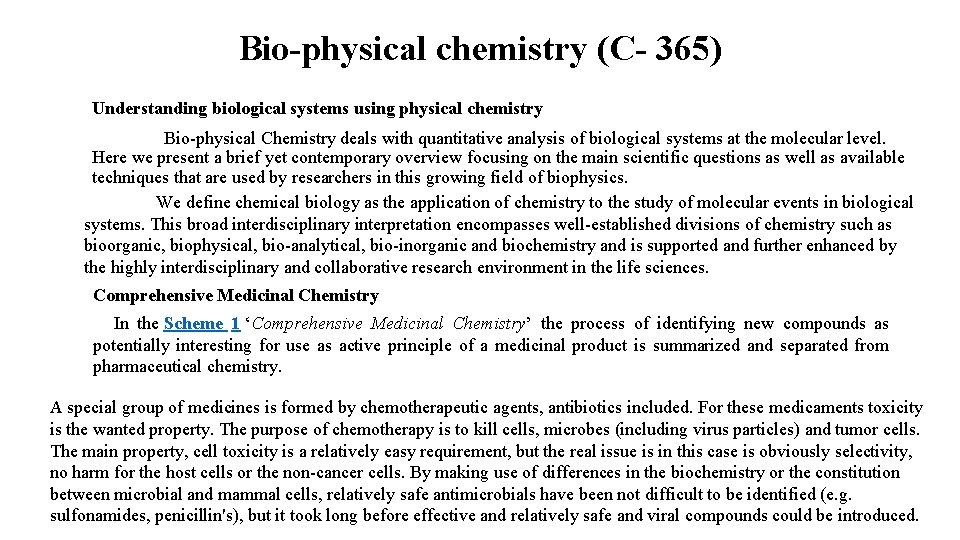

Bio-physical chemistry (C- 365) Understanding biological systems using physical chemistry Bio-physical Chemistry deals with quantitative analysis of biological systems at the molecular level. Here we present a brief yet contemporary overview focusing on the main scientific questions as well as available techniques that are used by researchers in this growing field of biophysics. We define chemical biology as the application of chemistry to the study of molecular events in biological systems. This broad interdisciplinary interpretation encompasses well-established divisions of chemistry such as bioorganic, biophysical, bio-analytical, bio-inorganic and biochemistry and is supported and further enhanced by the highly interdisciplinary and collaborative research environment in the life sciences. Comprehensive Medicinal Chemistry In the Scheme 1 ‘Comprehensive Medicinal Chemistry’ the process of identifying new compounds as potentially interesting for use as active principle of a medicinal product is summarized and separated from pharmaceutical chemistry. A special group of medicines is formed by chemotherapeutic agents, antibiotics included. For these medicaments toxicity is the wanted property. The purpose of chemotherapy is to kill cells, microbes (including virus particles) and tumor cells. The main property, cell toxicity is a relatively easy requirement, but the real issue is in this case is obviously selectivity, no harm for the host cells or the non-cancer cells. By making use of differences in the biochemistry or the constitution between microbial and mammal cells, relatively safe antimicrobials have been not difficult to be identified (e. g. sulfonamides, penicillin's), but it took long before effective and relatively safe and viral compounds could be introduced.

Comprehensive Medicinal Chemistry treated as an interactive circular process.

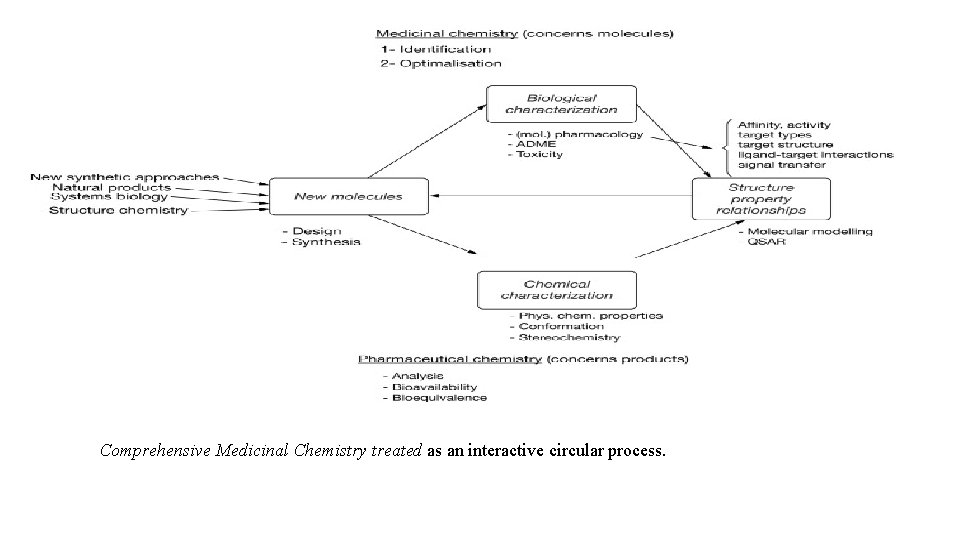

Bio-Physical Chemistry Thermodynamics The branch of physical chemistry known as thermodynamics is concerned with the study of the transformations of energy. That concern might seem remote from chemistry, let alone biology; indeed, thermodynamics was originally formulated by physicists and engineers interested in the efficiency of steam engines. However, thermodynamics has proved to be of immense importance in both chemistry and biology. Not only does it deal with the energy output of chemical reactions but it also helps to answer questions that lie right at the heart of biochemistry, such as how energy flows in biological cells and how large molecules assemble into complex structures like the cell.

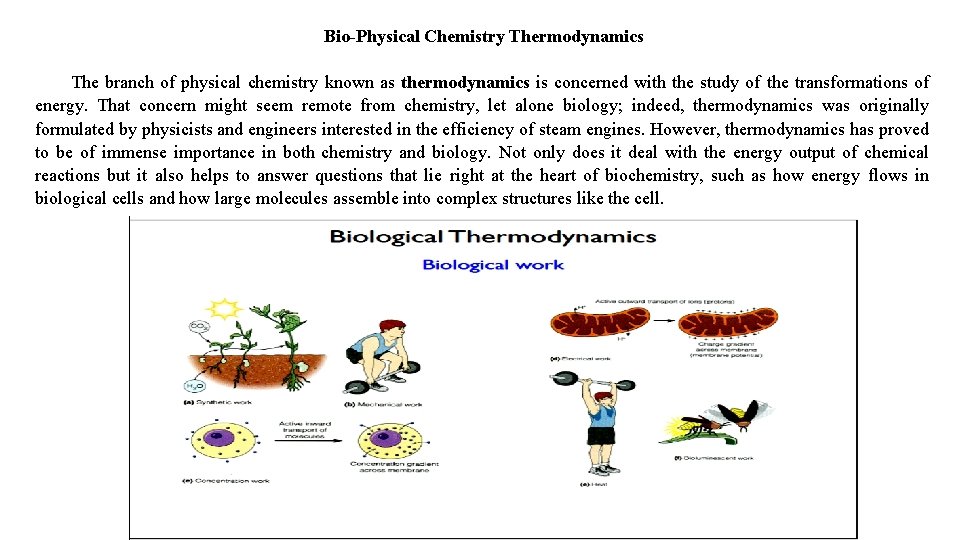

The First Law of Thermodynamics The Energy is conserved The total energy of a system and its surroundings is constant. In any physical or chemical change, the total amount of energy in the universe remains constant, although the form of the energy may change.

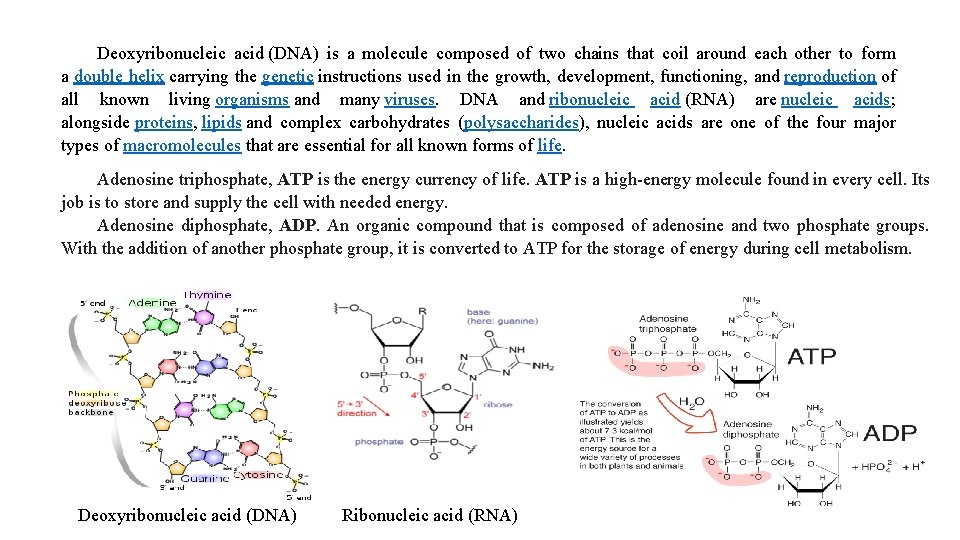

Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is a molecule composed of two chains that coil around each other to form a double helix carrying the genetic instructions used in the growth, development, functioning, and reproduction of all known living organisms and many viruses. DNA and ribonucleic acid (RNA) are nucleic acids; alongside proteins, lipids and complex carbohydrates (polysaccharides), nucleic acids are one of the four major types of macromolecules that are essential for all known forms of life. Adenosine triphosphate, ATP is the energy currency of life. ATP is a high-energy molecule found in every cell. Its job is to store and supply the cell with needed energy. Adenosine diphosphate, ADP. An organic compound that is composed of adenosine and two phosphate groups. With the addition of another phosphate group, it is converted to ATP for the storage of energy during cell metabolism. Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) Ribonucleic acid (RNA)

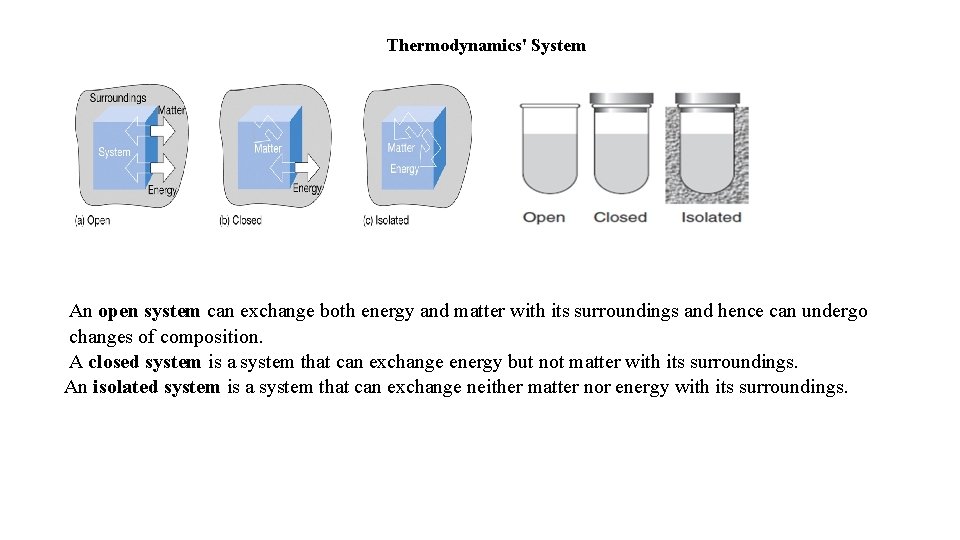

Thermodynamics' System An open system can exchange both energy and matter with its surroundings and hence can undergo changes of composition. A closed system is a system that can exchange energy but not matter with its surroundings. An isolated system is a system that can exchange neither matter nor energy with its surroundings.

Thermodynamics Process 1 - Isothermal Process Isothermal process, the process in which change in pressure and volume takes place at a constant temperature (T constant) (W = Q). 2 - Adiabatic Process Adiabatic process, the process in which change in pressure and volume and temperature takes place, without any heat entering or leaving the system (Q = 0). 3 - Isobaric Process Isobaric process, the process in which change in volume and temperature of a gas take place at a constant pressure (P constant) (W = P ∆V). 4 - Isochoric Process Isochoric process, the process in which change in pressure and temperature, take place in such a way that the volume of the system remains constant (V constant) (W = 0). 5 - Cyclic Process In a system in which the parameters acquire the original values, the process is called a cyclic process. In a cyclic process, the system starts and returns to the same thermodynamic state. 6 - Reversible and Irreversible Process The reversible process is the ideal process which never occurs, while the irreversible process is the natural process that is commonly found in nature.

Laws of Thermodynamics First Law: (∆U = q + w), heat (q) and work (w) are both forms of energy (∆U, internal energy). In any process, energy can be changed from one form to another (including heat and work), but it is never created or destroyed: Conservation of energy. In the first-law relation: ∆U = q + w, the quantities U, q and w are all measured in an arbitrary local frame. We can write an analogous relation for measurements in a stationary lab frame: ∆Esys. = qlab. + wlab. . Second Law: (d. S = dq(rev. ) /T), for a reversible change of a closed system; d. S > dq =Tb for an irreversible change of a closed system; where S is an extensive state function, the entropy, and dq is an infinitesimal quantity of energy transferred by heat at a portion of the boundary where thermodynamic temperature is Tb). Entropy is a measure of disorder; entropy of an isolated system increases in any spontaneous process. OR This law also predicts that the entropy of an isolated system always increases with time. Third Law: (∆S = 0, or, So =0) (for pure, perfectly-ordered crystals)) The entropy of a perfect crystal approaches zero as temperature approaches absolute zero. Work and heat As an example of these different ways of transferring energy, consider a chemical reaction that is a net producer of gas, such as the reaction between urea, (NH 2)2 CO, and oxygen to yield carbon dioxide, water, and nitrogen:

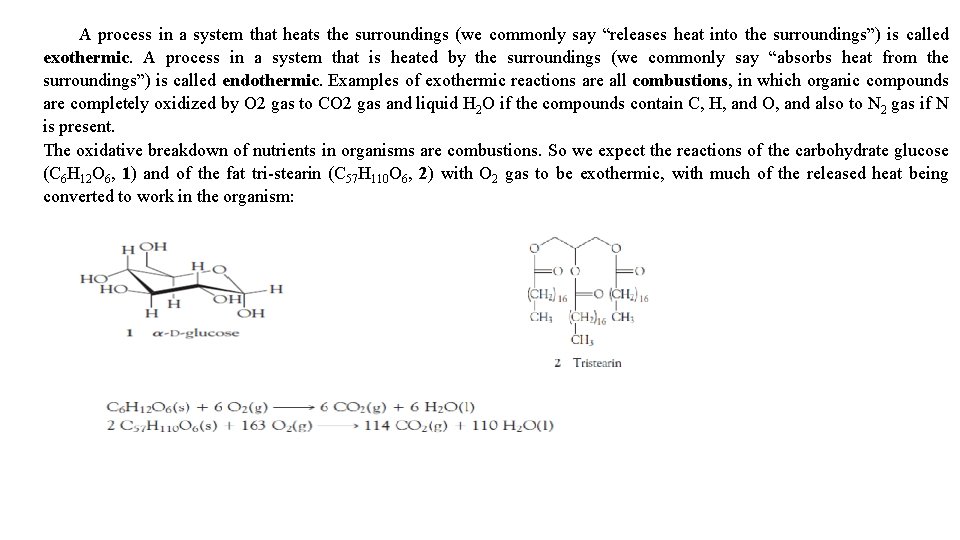

A process in a system that heats the surroundings (we commonly say “releases heat into the surroundings”) is called exothermic. A process in a system that is heated by the surroundings (we commonly say “absorbs heat from the surroundings”) is called endothermic. Examples of exothermic reactions are all combustions, in which organic compounds are completely oxidized by O 2 gas to CO 2 gas and liquid H 2 O if the compounds contain C, H, and O, and also to N 2 gas if N is present. The oxidative breakdown of nutrients in organisms are combustions. So we expect the reactions of the carbohydrate glucose (C 6 H 12 O 6, 1) and of the fat tri-stearin (C 57 H 110 O 6, 2) with O 2 gas to be exothermic, with much of the released heat being converted to work in the organism:

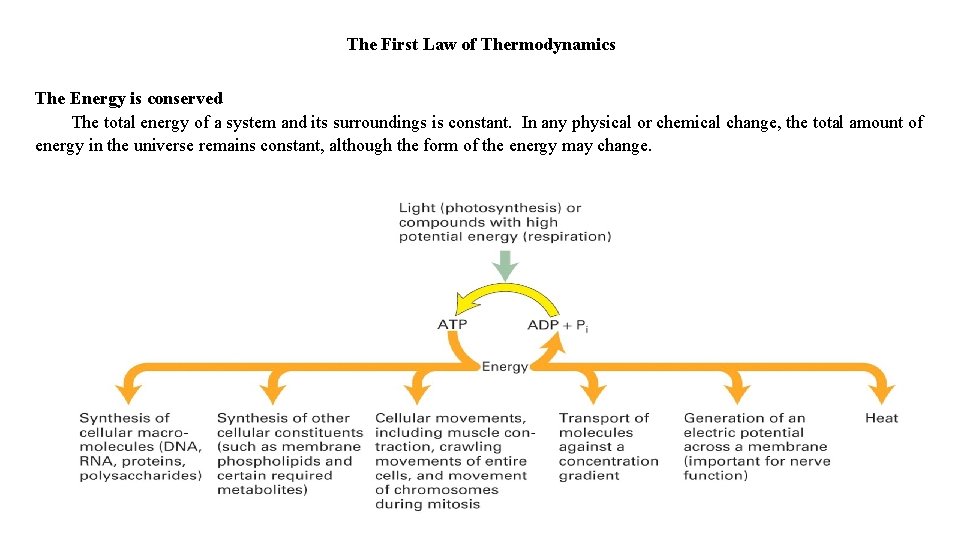

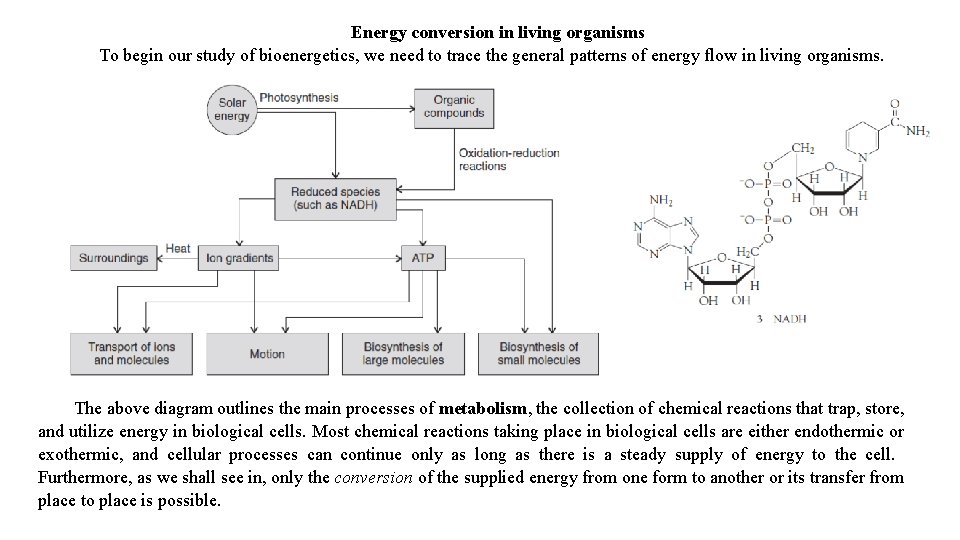

Energy conversion in living organisms To begin our study of bioenergetics, we need to trace the general patterns of energy flow in living organisms. The above diagram outlines the main processes of metabolism, the collection of chemical reactions that trap, store, and utilize energy in biological cells. Most chemical reactions taking place in biological cells are either endothermic or exothermic, and cellular processes can continue only as long as there is a steady supply of energy to the cell. Furthermore, as we shall see in, only the conversion of the supplied energy from one form to another or its transfer from place to place is possible.

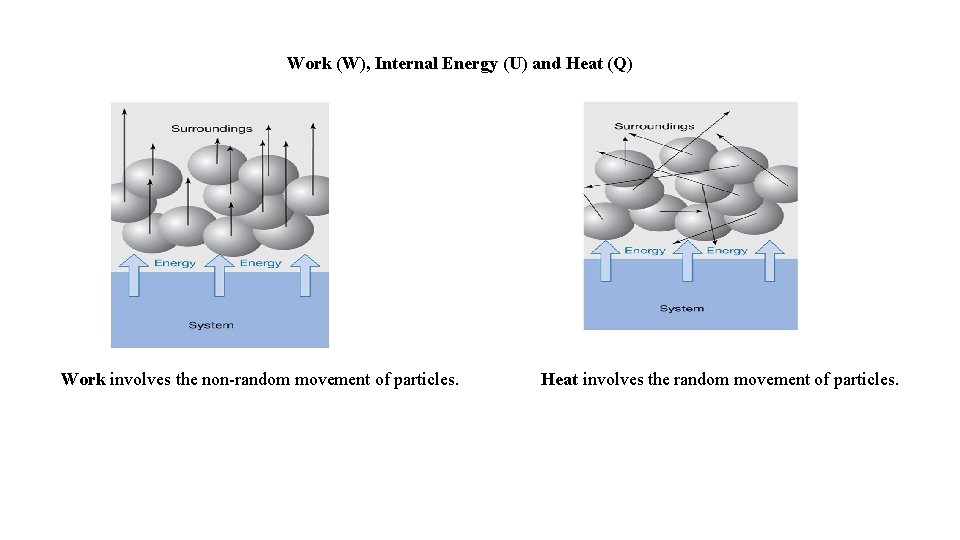

Work (W), Internal Energy (U) and Heat (Q) Work involves the non-random movement of particles. Heat involves the random movement of particles.

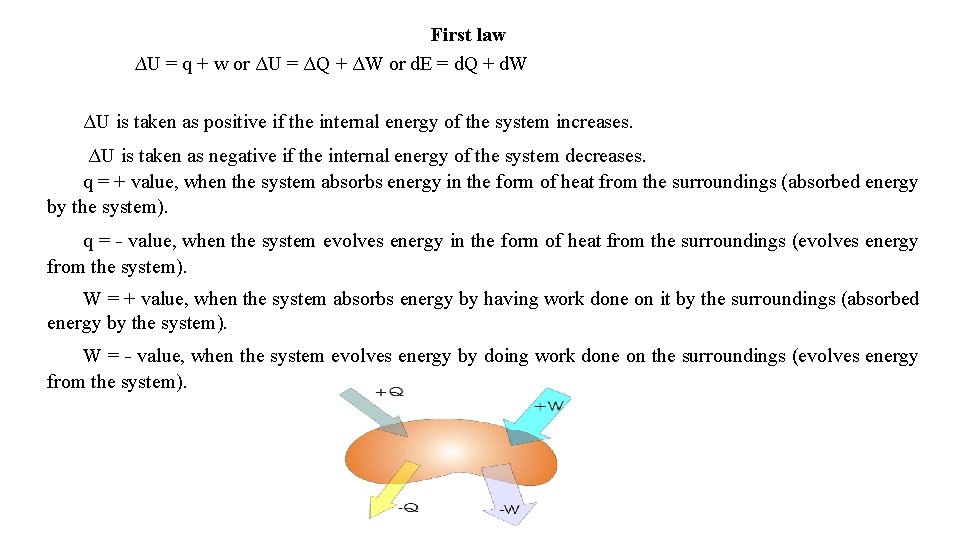

First law ∆U = q + w or ΔU = ΔQ + ΔW or d. E = d. Q + d. W ΔU is taken as positive if the internal energy of the system increases. ΔU is taken as negative if the internal energy of the system decreases. q = + value, when the system absorbs energy in the form of heat from the surroundings (absorbed energy by the system). q = - value, when the system evolves energy in the form of heat from the surroundings (evolves energy from the system). W = + value, when the system absorbs energy by having work done on it by the surroundings (absorbed energy by the system). W = - value, when the system evolves energy by doing work done on the surroundings (evolves energy from the system).

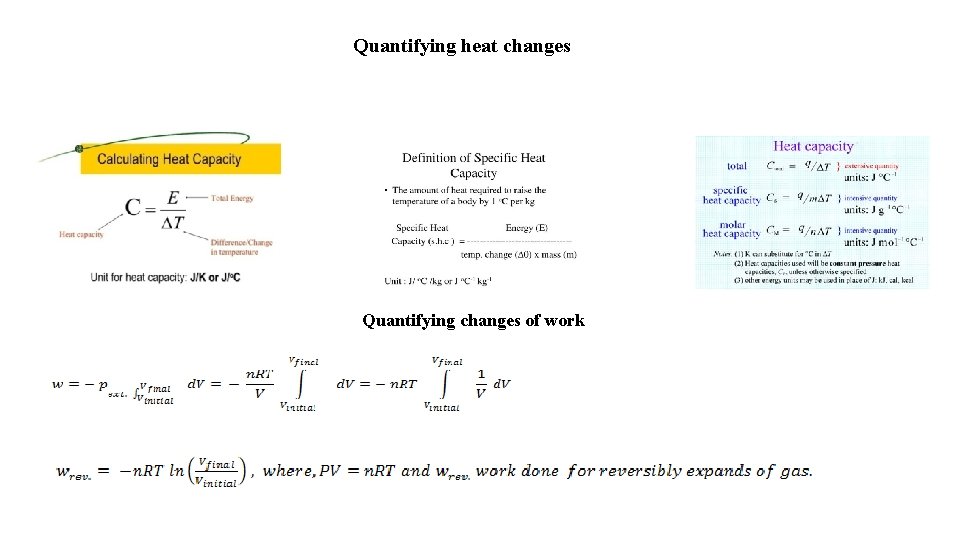

Quantifying heat changes Quantifying changes of work

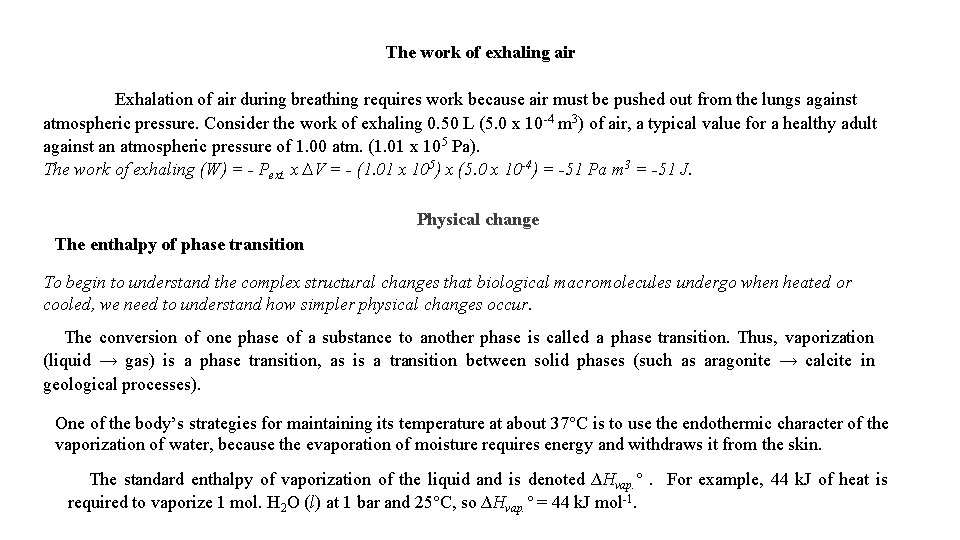

The work of exhaling air Exhalation of air during breathing requires work because air must be pushed out from the lungs against atmospheric pressure. Consider the work of exhaling 0. 50 L (5. 0 x 10 -4 m 3) of air, a typical value for a healthy adult against an atmospheric pressure of 1. 00 atm. (1. 01 x 105 Pa). The work of exhaling (W) = - Pext. x ∆V = - (1. 01 x 105) x (5. 0 x 10 -4) = -51 Pa m 3 = -51 J. Physical change The enthalpy of phase transition To begin to understand the complex structural changes that biological macromolecules undergo when heated or cooled, we need to understand how simpler physical changes occur. The conversion of one phase of a substance to another phase is called a phase transition. Thus, vaporization (liquid → gas) is a phase transition, as is a transition between solid phases (such as aragonite → calcite in geological processes). One of the body’s strategies for maintaining its temperature at about 37°C is to use the endothermic character of the vaporization of water, because the evaporation of moisture requires energy and withdraws it from the skin. The standard enthalpy of vaporization of the liquid and is denoted ∆Hvap. °. For example, 44 k. J of heat is required to vaporize 1 mol. H 2 O (l) at 1 bar and 25°C, so ∆Hvap. ° = 44 k. J mol-1.

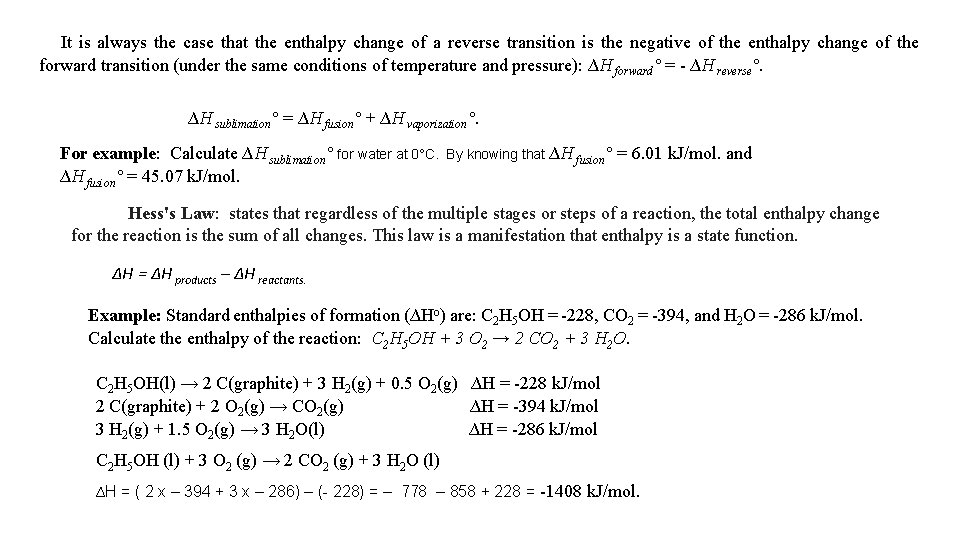

It is always the case that the enthalpy change of a reverse transition is the negative of the enthalpy change of the forward transition (under the same conditions of temperature and pressure): ∆H forward° = - ∆H reverse°. ∆H sublimation° = ∆H fusion° + ∆H vaporization°. For example: Calculate ∆H sublimation° for water at 0°C. ∆H fusion° = 45. 07 k. J/mol. By knowing that ∆H fusion° = 6. 01 k. J/mol. and Hess's Law: states that regardless of the multiple stages or steps of a reaction, the total enthalpy change for the reaction is the sum of all changes. This law is a manifestation that enthalpy is a state function. ∆H = ∆H products – ∆H reactants. Example: Standard enthalpies of formation (∆Ho) are: C 2 H 5 OH = -228, CO 2 = -394, and H 2 O = -286 k. J/mol. Calculate the enthalpy of the reaction: C 2 H 5 OH + 3 O 2 → 2 CO 2 + 3 H 2 O. C 2 H 5 OH(l) → 2 C(graphite) + 3 H 2(g) + 0. 5 O 2(g) ∆H = -228 k. J/mol 2 C(graphite) + 2 O 2(g) → CO 2(g) ∆H = -394 k. J/mol 3 H 2(g) + 1. 5 O 2(g) → 3 H 2 O(l) ∆H = -286 k. J/mol C 2 H 5 OH (l) + 3 O 2 (g) → 2 CO 2 (g) + 3 H 2 O (l) ∆H = ( 2 x – 394 + 3 x – 286) – (- 228) = – 778 – 858 + 228 = -1408 k. J/mol.

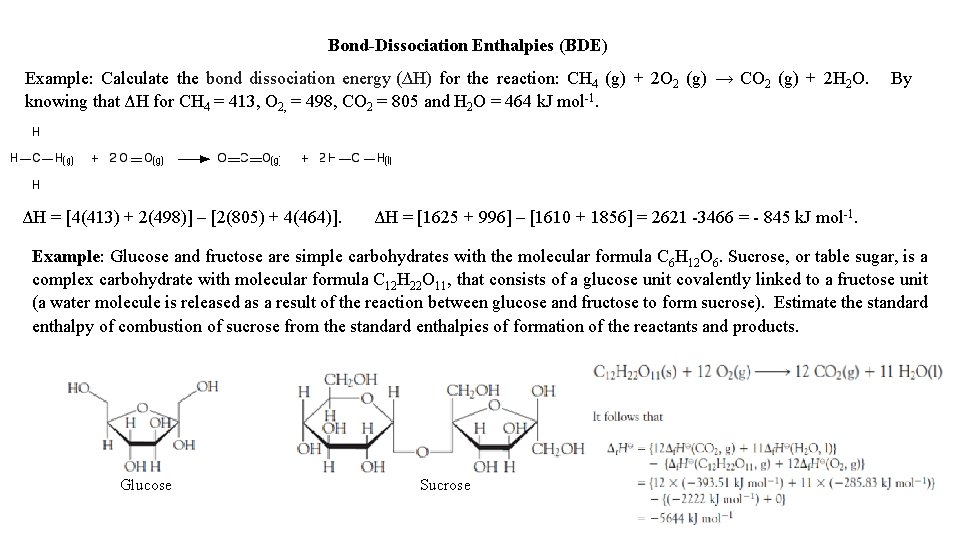

Bond-Dissociation Enthalpies (BDE) Example: Calculate the bond dissociation energy (∆H) for the reaction: CH 4 (g) + 2 O 2 (g) → CO 2 (g) + 2 H 2 O. knowing that ΔH for CH 4 = 413, O 2, = 498, CO 2 = 805 and H 2 O = 464 k. J mol-1. ΔH = [4(413) + 2(498)] – [2(805) + 4(464)]. By ΔH = [1625 + 996] – [1610 + 1856] = 2621 -3466 = - 845 k. J mol-1. Example: Glucose and fructose are simple carbohydrates with the molecular formula C 6 H 12 O 6. Sucrose, or table sugar, is a complex carbohydrate with molecular formula C 12 H 22 O 11, that consists of a glucose unit covalently linked to a fructose unit (a water molecule is released as a result of the reaction between glucose and fructose to form sucrose). Estimate the standard enthalpy of combustion of sucrose from the standard enthalpies of formation of the reactants and products. Glucose Sucrose

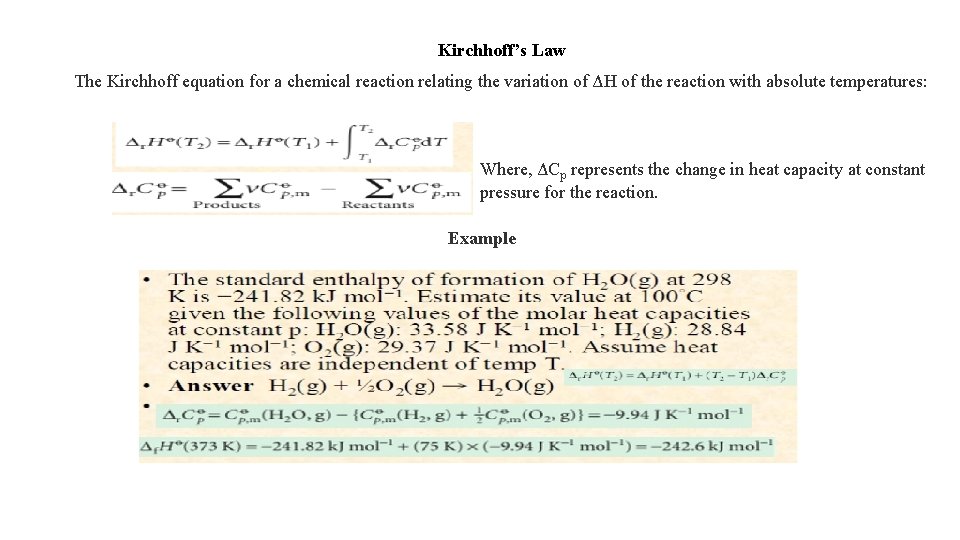

Kirchhoff’s Law The Kirchhoff equation for a chemical reaction relating the variation of ΔH of the reaction with absolute temperatures: Where, ΔCp represents the change in heat capacity at constant pressure for the reaction. Example

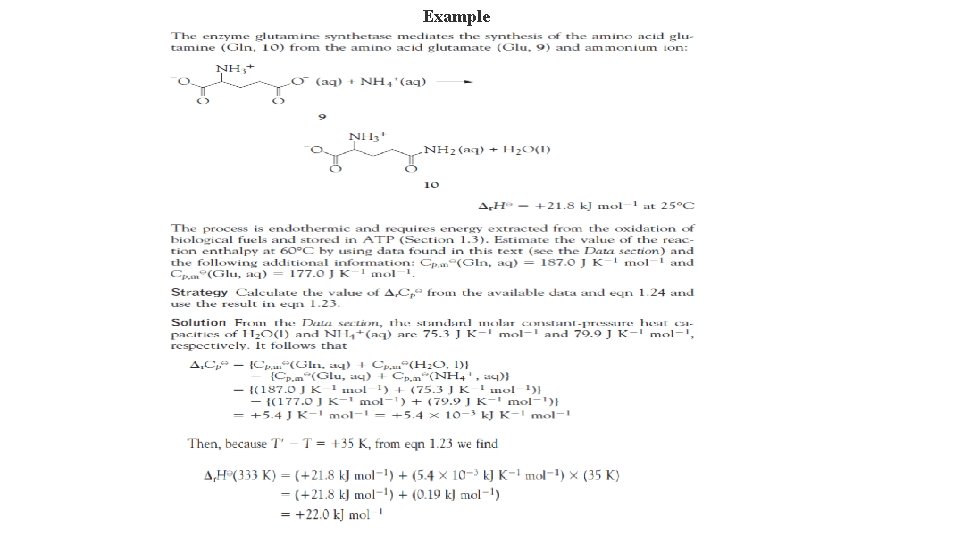

Example

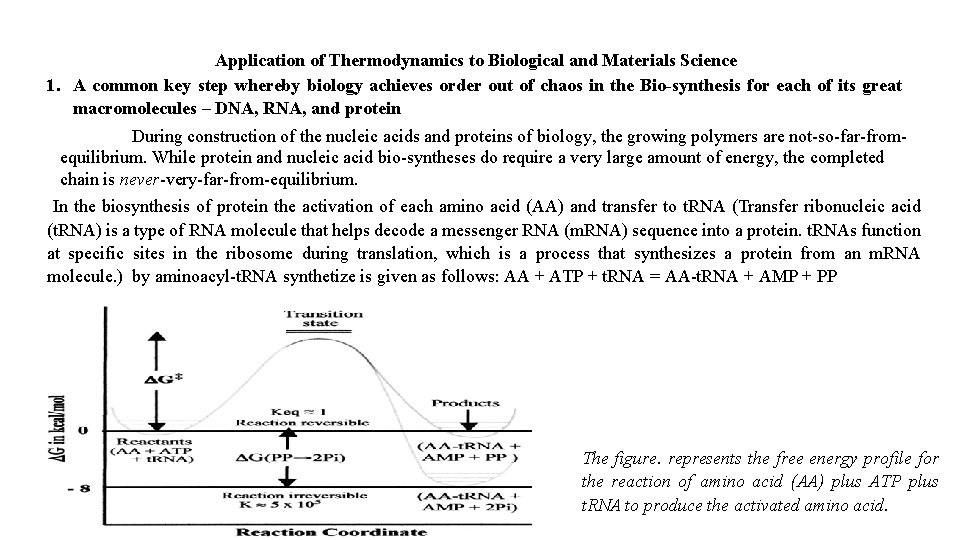

Application of Thermodynamics to Biological and Materials Science 1. A common key step whereby biology achieves order out of chaos in the Bio-synthesis for each of its great macromolecules – DNA, RNA, and protein During construction of the nucleic acids and proteins of biology, the growing polymers are not-so-far-fromequilibrium. While protein and nucleic acid bio-syntheses do require a very large amount of energy, the completed chain is never-very-far-from-equilibrium. In the biosynthesis of protein the activation of each amino acid (AA) and transfer to t. RNA (Transfer ribonucleic acid (t. RNA) is a type of RNA molecule that helps decode a messenger RNA (m. RNA) sequence into a protein. t. RNAs function at specific sites in the ribosome during translation, which is a process that synthesizes a protein from an m. RNA molecule. ) by aminoacyl-t. RNA synthetize is given as follows: AA + ATP + t. RNA = AA-t. RNA + AMP + PP The figure. represents the free energy profile for the reaction of amino acid (AA) plus ATP plus t. RNA to produce the activated amino acid.

2 - Hydration of the hydrophobic CH 2 group is exothermic Butler examined the water solubility of the series of linear alcohols – methanol (CH 3 -OH), ethanol (CH 3 -CH 2 -OH), n -propanol (CH 3 -CH 2 -OH), n-butanol (CH 3 -CH 2 -CH 2 -OH), and n-pentanol (CH 3 -CH 2 -CH 2 -OH) – and found the exothermic heat of dissolution to increase for each added CH 2, at the rate of ΔH/CH 2 = − 1. 5 kcal/mol. ΔG (dissolution) = ΔH − TΔS. Namely, the [−TΔS] term increases positively (unfavorably) for the Butler series as [−TΔS]/CH 2 = + 1. 7 kcal/mol. A positive ΔG (dissolution) means insolubility; too many CH 2 moieties exposed to water means insolubility 3 - Enthalpy, Entropy, and Volume Changes of Electron Transfer Reactions in Photosynthetic Proteins Photosynthesis involves a series of electron transfer steps to convert the sunlight energy into the chemical energy in green plants, algae, and cyanobacteria. The three–dimensional structures of photosynthetic reaction centers at the high resolution uncover the binding sites and precise orientation of cofactors and their interaction with proteins and provided an excellent model to investigate the mechanism of electron transfer reaction.

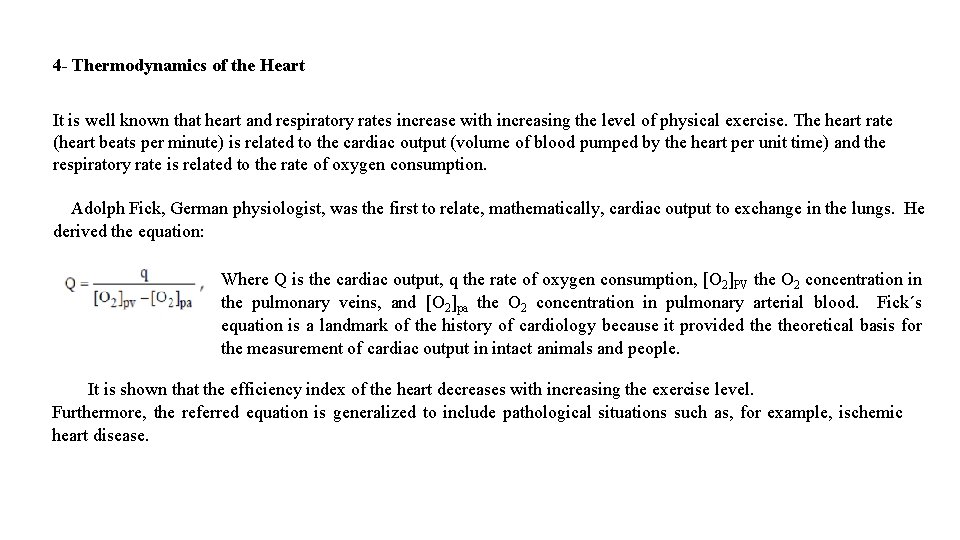

4 - Thermodynamics of the Heart It is well known that heart and respiratory rates increase with increasing the level of physical exercise. The heart rate (heart beats per minute) is related to the cardiac output (volume of blood pumped by the heart per unit time) and the respiratory rate is related to the rate of oxygen consumption. Adolph Fick, German physiologist, was the first to relate, mathematically, cardiac output to exchange in the lungs. He derived the equation: Where Q is the cardiac output, q the rate of oxygen consumption, [O 2]PV the O 2 concentration in the pulmonary veins, and [O 2]pa the O 2 concentration in pulmonary arterial blood. Fick´s equation is a landmark of the history of cardiology because it provided theoretical basis for the measurement of cardiac output in intact animals and people. It is shown that the efficiency index of the heart decreases with increasing the exercise level. Furthermore, the referred equation is generalized to include pathological situations such as, for example, ischemic heart disease.

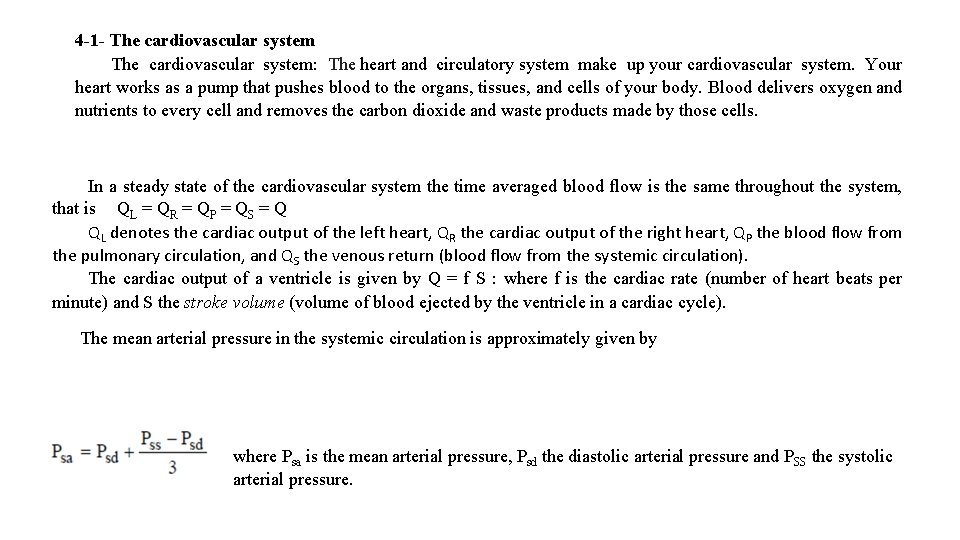

4 -1 - The cardiovascular system: The heart and circulatory system make up your cardiovascular system. Your heart works as a pump that pushes blood to the organs, tissues, and cells of your body. Blood delivers oxygen and nutrients to every cell and removes the carbon dioxide and waste products made by those cells. In a steady state of the cardiovascular system the time averaged blood flow is the same throughout the system, that is QL = QR = QP = QS = Q QL denotes the cardiac output of the left heart, QR the cardiac output of the right heart, QP the blood flow from the pulmonary circulation, and QS the venous return (blood flow from the systemic circulation). The cardiac output of a ventricle is given by Q = f S : where f is the cardiac rate (number of heart beats per minute) and S the stroke volume (volume of blood ejected by the ventricle in a cardiac cycle). The mean arterial pressure in the systemic circulation is approximately given by where Psa is the mean arterial pressure, Psd the diastolic arterial pressure and PSS the systolic arterial pressure.

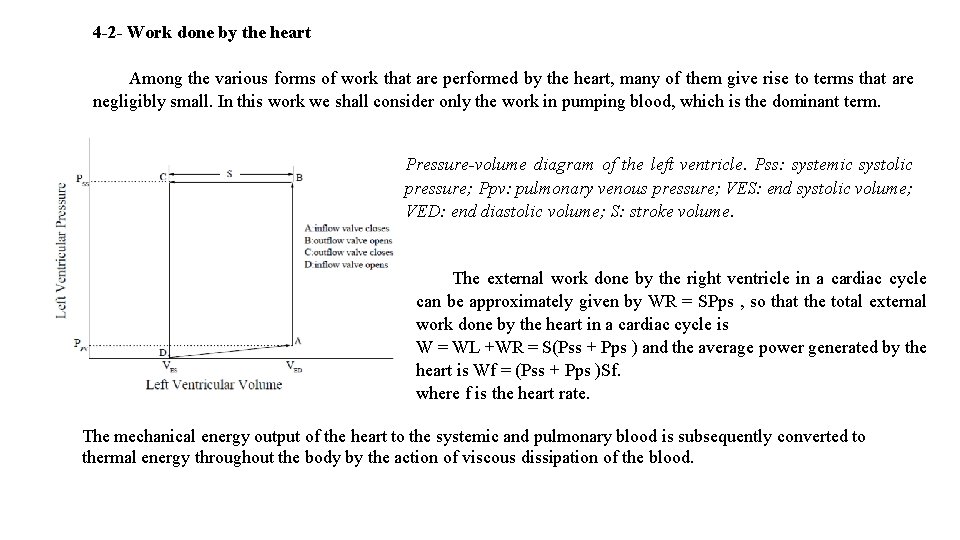

4 -2 - Work done by the heart Among the various forms of work that are performed by the heart, many of them give rise to terms that are negligibly small. In this work we shall consider only the work in pumping blood, which is the dominant term. Pressure-volume diagram of the left ventricle. Pss: systemic systolic pressure; Ppv: pulmonary venous pressure; VES: end systolic volume; VED: end diastolic volume; S: stroke volume. The external work done by the right ventricle in a cardiac cycle can be approximately given by WR = SPps , so that the total external work done by the heart in a cardiac cycle is W = WL +WR = S(Pss + Pps ) and the average power generated by the heart is Wf = (Pss + Pps )Sf. where f is the heart rate. The mechanical energy output of the heart to the systemic and pulmonary blood is subsequently converted to thermal energy throughout the body by the action of viscous dissipation of the blood.

- Slides: 24