BiologyDriven Clustering of Microarray Data Applications to the

Biology-Driven Clustering of Microarray Data: Applications to the NCI 60 Data Set K. R. Coombes, K. A. Baggerly, D. N. Stivers, J. Wang, D. Gold, H. G. Sung, and S. J. Lee

Introduction Methods Most analyses of microarray data proceed as though it were simply a large, unstructured matrix. Such analyses ignore substantial amounts of existing biological information. In the study of cancer, we already know many important genes through their involvement in specific biological processes, and we know that reproducible chromosomal abnormalities play an important role. We see a need for developing analytic strategies that exploit this biological information. We analyzed the NCI 60 data set by first determining the chromosomal location and biological function of the genes on the microarray. We performed separate analyses using genes on individual chromosomes and genes involved in different biological processes. The fundamental advantage of this approach is that it provides results that are immediately and directly interpretable without resorting to ex post facto rationalizations.

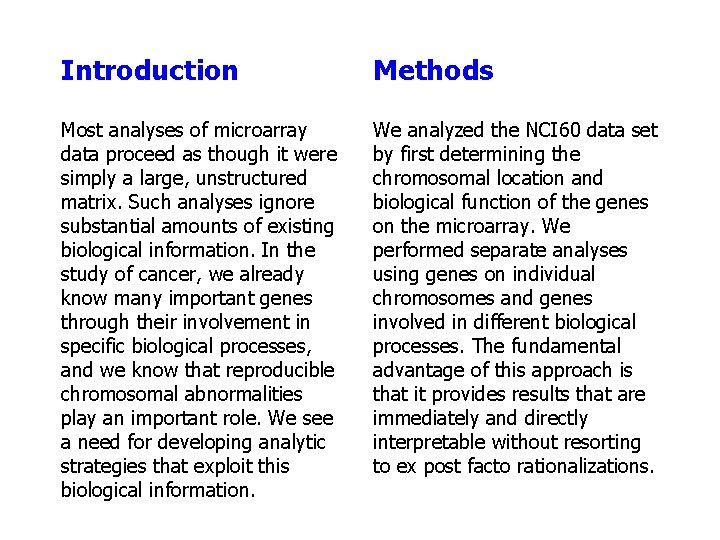

How many genes on the microarray have good annotations? • Problem: – I. M. A. G. E. clone IDs and Gen. Bank accession numbers are archival. – Uni. Gene clusters, gene names, descriptions, etc. , are changeable. • Solution: – Download the latest version of Uni. Gene (build 137) and Locus. Link (July 2001) to update annotations, using the Gen. Bank accession numbers describing both 3’ and 5’ ends of the genes spotted on the microarrays. Table 1: There are only 7478 spots (out of 10, 000) on the array with valid, matching Uni. Gene cluster IDs. Genes with unknown or conflicting annotations were eliminated before performing any further analysis.

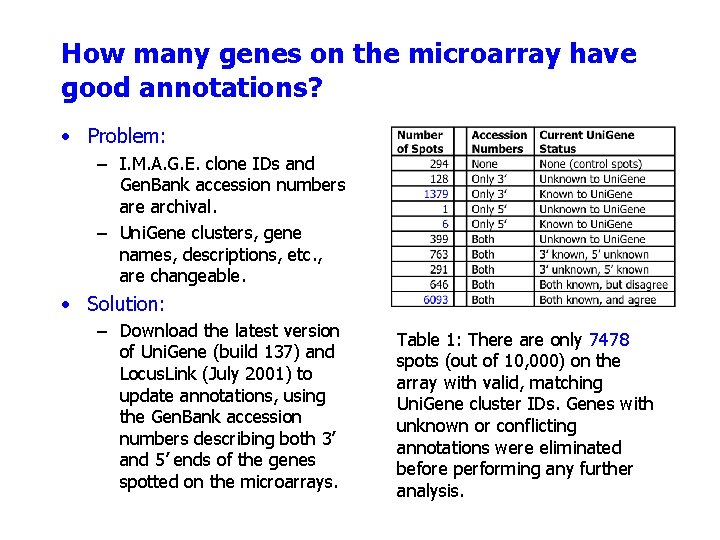

Where are the genes located? We compared the number of genes on the microarray that mapped to each chromosome with the number known to be on the chromosome, based on current figures from the NCBI. A chi-squared test was used to test whether the distribution of genes on chromosomes was uniform. Figure 1: Distribution of the genes on the array by chromosome. Chromosomes 19 and Y are substantially underrepresented when compared to the numbers known to Locus. Link; chromosomes 6 and 13 are overrepresented.

How do we determine gene functions? • • • Using our updated Uni. Gene clusters, we followed the links from Uni. Gene to Locus. Link to Gene. Ontology is a structured, hierarchical vocabulary to describe gene functions in three broad areas: – biological process (why) – molecular function (what) – cellular component (where) The 7478 good spots on the array corresponded to 6614 distinct genes, of which 5074 were known to Locus. Link, and 2989 had at least one annotation in Gene. Ontology. We focused on the biological process annotations in the Gene. Ontology vocabulary, since these had the most natural interpretation for application to the study of cancer. We counted the number of genes having annotations of functions at or below each level in the hierarchy, and selected a set of categories that each contained roughly one to a few hundred genes, with the categories as a whole accounting for more than 95% of all annotations (Table 2).

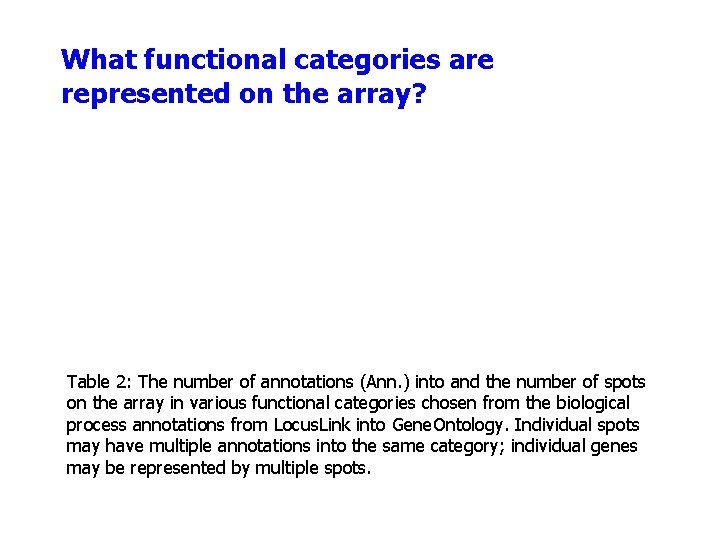

What functional categories are represented on the array? Table 2: The number of annotations (Ann. ) into and the number of spots on the array in various functional categories chosen from the biological process annotations from Locus. Link into Gene. Ontology. Individual spots may have multiple annotations into the same category; individual genes may be represented by multiple spots.

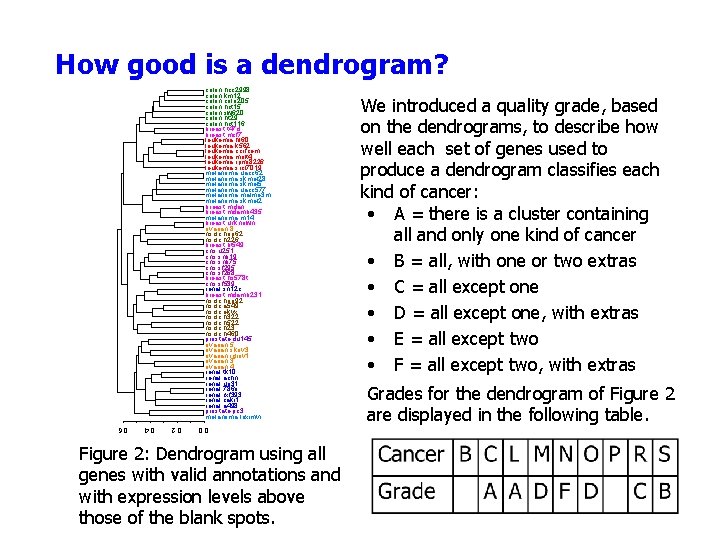

How good is a dendrogram? colon. hcc 2998 colon. km 12 colon. colo 205 colon. hct 15 colon. sw 620 colon. ht 29 colon. hct 116 breast. t 47 d breast. mcf 7 leukemia. hl 60 leukemia. k 562 leukemia. ccrfcem leukemia. molt 4 leukemia. rpmi 8226 leukemia. srcl 7019 melanoma. uacc 62 melanoma. skmel 28 melanoma. skmel 5 melanoma. uacc 577 melanoma. malme 3 m melanoma. skmel 2 breast. mdan breast. mdamb 435 melanoma. m 14 breast. unknown ovarian. 8 nsclc. hop 62 nsclc. h 226 breast. bt 549 cns. u 251 cns. snb 19 cns. snb 75 cns. sf 295 cns. sf 268 breast. hs 578 t cns. sf 539 renal. sn 12 c breast. mdamb 231 nsclc. hop 92 nsclc. a 549 nsclc. ekvx nsclc. h 322 nsclc. h 522 nsclc. h 23 nsclc. h 460 prostate. du 145 ovarian. skov 3 ovarian. igrov 1 ovarian. 3 ovarian. 4 renal. tk 10 renal. achn renal. uo 31 renal. 786 o renal. rxf 393 renal. caki 1 renal. a 498 prostate. pc 3 melanoma. loximvi 0. 0 0. 2 0. 4 0. 6 Figure 2: Dendrogram using all genes with valid annotations and with expression levels above those of the blank spots. We introduced a quality grade, based on the dendrograms, to describe how well each set of genes used to produce a dendrogram classifies each kind of cancer: • A = there is a cluster containing all and only one kind of cancer • B = all, with one or two extras • C = all except one • D = all except one, with extras • E = all except two • F = all except two, with extras Grades for the dendrogram of Figure 2 are displayed in the following table.

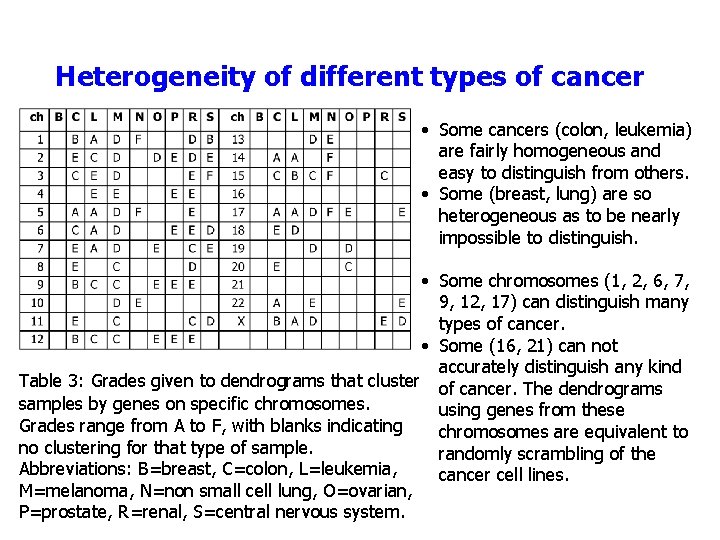

Heterogeneity of different types of cancer • Some cancers (colon, leukemia) are fairly homogeneous and easy to distinguish from others. • Some (breast, lung) are so heterogeneous as to be nearly impossible to distinguish. • Some chromosomes (1, 2, 6, 7, 9, 12, 17) can distinguish many types of cancer. • Some (16, 21) can not accurately distinguish any kind Table 3: Grades given to dendrograms that cluster of cancer. The dendrograms samples by genes on specific chromosomes. using genes from these Grades range from A to F, with blanks indicating chromosomes are equivalent to no clustering for that type of sample. randomly scrambling of the Abbreviations: B=breast, C=colon, L=leukemia, cancer cell lines. M=melanoma, N=non small cell lung, O=ovarian, P=prostate, R=renal, S=central nervous system.

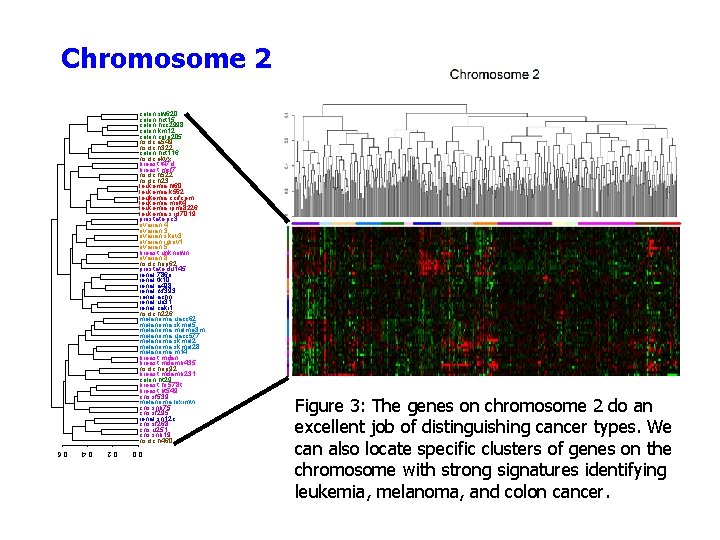

Chromosome 2 colon. sw 620 colon. hct 15 colon. hcc 2998 colon. km 12 colon. colo 205 nsclc. a 549 nsclc. h 322 colon. hct 116 nsclc. ekvx breast. t 47 d breast. mcf 7 nsclc. h 522 nsclc. h 23 leukemia. hl 60 leukemia. k 562 leukemia. ccrfcem leukemia. molt 4 leukemia. rpmi 8226 leukemia. srcl 7019 prostate. pc 3 ovarian. 4 ovarian. 3 ovarian. skov 3 ovarian. igrov 1 ovarian. 5 breast. unknown ovarian. 8 nsclc. hop 62 prostate. du 145 renal. 786 o renal. tk 10 renal. a 498 renal. rxf 393 renal. achn renal. uo 31 renal. caki 1 nsclc. h 226 melanoma. uacc 62 melanoma. skmel 5 melanoma. malme 3 m melanoma. uacc 577 melanoma. skmel 28 melanoma. m 14 breast. mdan breast. mdamb 435 nsclc. hop 92 breast. mdamb 231 colon. ht 29 breast. hs 578 t breast. bt 549 cns. sf 539 melanoma. loximvi cns. snb 75 cns. sf 295 renal. sn 12 c cns. sf 268 cns. u 251 cns. snb 19 nsclc. h 460 Figure 3: The genes on chromosome 2 do an excellent job of distinguishing cancer types. We can also locate specific clusters of genes on the chromosome with strong signatures identifying leukemia, melanoma, and colon cancer. 0. 0 0. 2 0. 4 0. 6

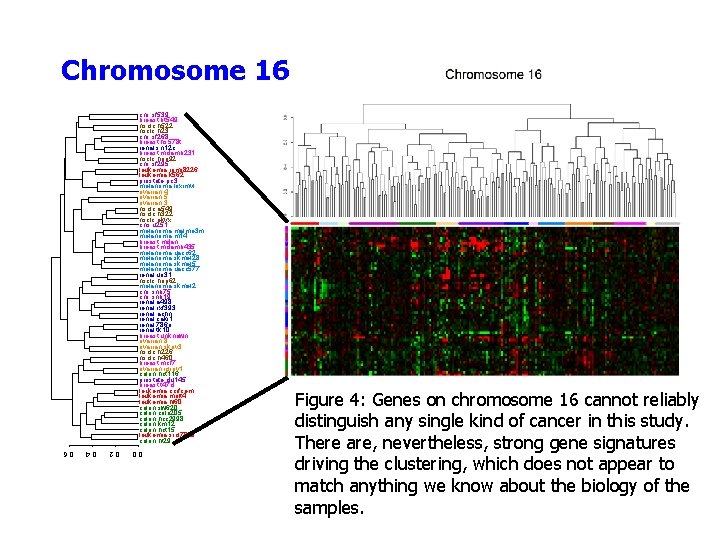

Chromosome 16 cns. sf 539 breast. bt 549 nsclc. h 522 nsclc. h 23 cns. sf 268 breast. hs 578 t renal. sn 12 c breast. mdamb 231 nsclc. hop 92 cns. sf 295 leukemia. rpmi 8226 leukemia. k 562 prostate. pc 3 melanoma. loximvi ovarian. 4 ovarian. 5 ovarian. 3 nsclc. a 549 nsclc. h 322 nsclc. ekvx cns. u 251 melanoma. malme 3 m melanoma. m 14 breast. mdan breast. mdamb 435 melanoma. uacc 62 melanoma. skmel 28 melanoma. skmel 5 melanoma. uacc 577 renal. uo 31 nsclc. hop 62 melanoma. skmel 2 cns. snb 75 cns. snb 19 renal. a 498 renal. rxf 393 renal. achn renal. caki 1 renal. 786 o renal. tk 10 breast. unknown ovarian. 8 ovarian. skov 3 nsclc. h 226 nsclc. h 460 breast. mcf 7 ovarian. igrov 1 colon. hct 116 prostate. du 145 breast. t 47 d leukemia. ccrfcem leukemia. molt 4 leukemia. hl 60 colon. sw 620 colon. colo 205 colon. hcc 2998 colon. km 12 colon. hct 15 leukemia. srcl 7019 colon. ht 29 Figure 4: Genes on chromosome 16 cannot reliably distinguish any single kind of cancer in this study. There are, nevertheless, strong gene signatures driving the clustering, which does not appear to match anything we know about the biology of the samples. 0. 0 0. 2 0. 4 0. 6

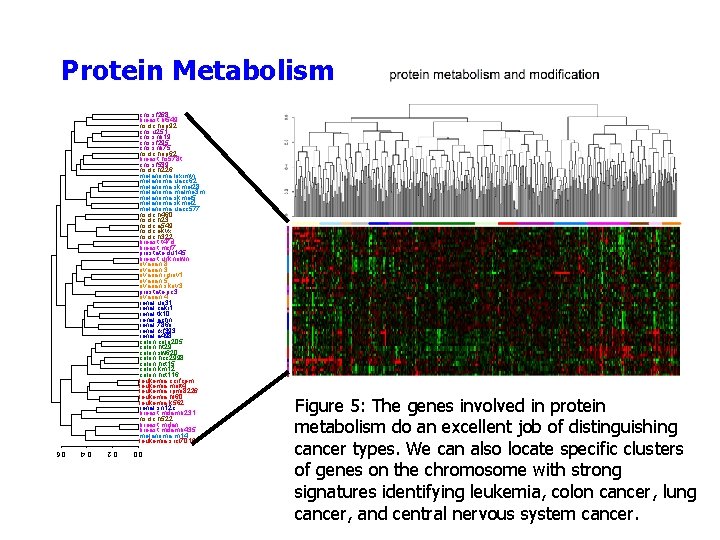

Protein Metabolism cns. sf 268 breast. bt 549 nsclc. hop 92 cns. u 251 cns. snb 19 cns. sf 295 cns. snb 75 nsclc. hop 62 breast. hs 578 t cns. sf 539 nsclc. h 226 melanoma. loximvi melanoma. uacc 62 melanoma. skmel 28 melanoma. malme 3 m melanoma. skmel 5 melanoma. skmel 2 melanoma. uacc 577 nsclc. h 460 nsclc. h 23 nsclc. a 549 nsclc. ekvx nsclc. h 322 breast. t 47 d breast. mcf 7 prostate. du 145 breast. unknown ovarian. 8 ovarian. 3 ovarian. igrov 1 ovarian. 5 ovarian. skov 3 prostate. pc 3 ovarian. 4 renal. uo 31 renal. caki 1 renal. tk 10 renal. achn renal. 786 o renal. rxf 393 renal. a 498 colon. colo 205 colon. ht 29 colon. sw 620 colon. hcc 2998 colon. hct 15 colon. km 12 colon. hct 116 leukemia. ccrfcem leukemia. molt 4 leukemia. rpmi 8226 leukemia. hl 60 leukemia. k 562 renal. sn 12 c breast. mdamb 231 nsclc. h 522 breast. mdan breast. mdamb 435 melanoma. m 14 leukemia. srcl 7019 Figure 5: The genes involved in protein metabolism do an excellent job of distinguishing cancer types. We can also locate specific clusters of genes on the chromosome with strong signatures identifying leukemia, colon cancer, lung cancer, and central nervous system cancer. 0. 0 0. 2 0. 4 0. 6

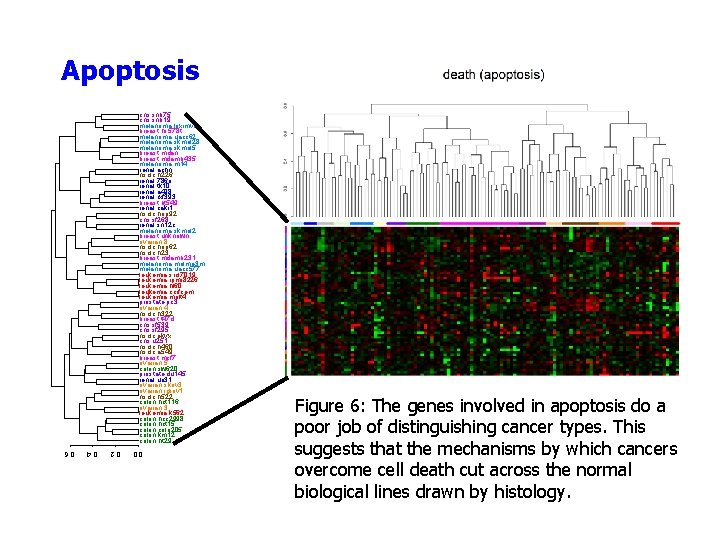

Apoptosis cns. snb 75 cns. snb 19 melanoma. loximvi breast. hs 578 t melanoma. uacc 62 melanoma. skmel 28 melanoma. skmel 5 breast. mdan breast. mdamb 435 melanoma. m 14 renal. achn nsclc. h 226 renal. 786 o renal. tk 10 renal. a 498 renal. rxf 393 breast. bt 549 renal. caki 1 nsclc. hop 92 cns. sf 268 renal. sn 12 c melanoma. skmel 2 breast. unknown ovarian. 8 nsclc. hop 62 nsclc. h 23 breast. mdamb 231 melanoma. malme 3 m melanoma. uacc 577 leukemia. srcl 7019 leukemia. rpmi 8226 leukemia. hl 60 leukemia. ccrfcem leukemia. molt 4 prostate. pc 3 ovarian. 4 nsclc. h 322 breast. t 47 d cns. sf 539 cns. sf 295 nsclc. ekvx cns. u 251 nsclc. h 460 nsclc. a 549 breast. mcf 7 ovarian. 5 colon. sw 620 prostate. du 145 renal. uo 31 ovarian. skov 3 ovarian. igrov 1 nsclc. h 522 colon. hct 116 ovarian. 3 leukemia. k 562 colon. hcc 2998 colon. hct 15 colon. colo 205 colon. km 12 colon. ht 29 Figure 6: The genes involved in apoptosis do a poor job of distinguishing cancer types. This suggests that the mechanisms by which cancers overcome cell death cut across the normal biological lines drawn by histology. 0. 0 0. 2 0. 4 0. 6

Conclusions Multiple views into the data provide substantial insight into differences in cancer types and gene sets. Cancer types differ greatly in their degree of heterogeneity, ranging from homogeneous (colon, leukemia) through moderately heterogeneous (renal, melanoma) to extremely heterogeneous (breast and lung). Homogeneous cancers exhibit strong identifying signals across most views of the data, regardless of function or chromosome. There are large difference in the ability of genes of different chromosomes to distinguish cancer types. There are similar differences for genes involved in different biological processes (data not shown). Functional categories that are good at distinguishing cancers include signal transduction, cell cycle, cell proliferation, and protein metabolism. Some differences result from the histology of the underlying tissue. Others reflect differences in the way particular kinds of cancers overcome limits on cell growth. Categories that are poor at distinguishing cancers include energy pathways and apoptosis. The latter observation has potential implications for cancer therapies designed to trigger apoptosis, since it suggests that the mechanisms by which cancer cells avoid cell death are not linked to the general type of cancer but are either common across cancers or idiosyncratic.

- Slides: 13