Biological processing of waste landfarming composting anaerobic digestion

Biological processing of waste (landfarming, composting, anaerobic digestion) WASTE MANAGEMENT AND TECHNOLOGY František Straka Institute of Chemical Technology in Prague

landfarming – definitions Landfarming is a bioremediation treatment process that is performed in the upper soil zone or in biotreatment cells. Contaminated soils, sediments, or sludges are incorporated into the soil surface and periodically turned over (tilled) to aerate the mixture. Landfarming of waste - a disposal process in which hazardous waste deposited on or in the soil is degraded naturally by microbes. Landfarming must not be used to dilute contaminants. If it cannot be shown that biodegradation occurs for all contaminants of concern, land farming should not be used. http: //www. ecologydictionary. org/Land_Farming

landfarming – description Wastes (contaminated soils, sludges, sediments) are mixed with soil amendments such as soil bulking agents and nutrients, and then they are tilled into the earth. The material is periodically tilled for aeration. Waste constituents are degraded, transformed, and immobilized by microbiological processes and by oxidation. Soil conditions are controlled to optimize the rate of contaminant degradation. Moisture content, frequency of aeration, and p. H are all conditions that may be controlled. Landfarming differs from composting because it actually incorporates contaminated soil into soil that is uncontaminated. Many waste constituents may be banned by regulation from being applied to soil. The depth of treatment is limited to the depth of achievable tilling (normally 18 inches). http: //www. cpeo. org/techtree/ttdescript/lanfarm. htm

landfarming – applicability Landfarming has been proven most successful in treating petroleum hydrocarbons and other less volatile, biodegradable contaminants. The more chlorinated or nitrated the compound, the more difficult it is to degrade. Many mixed products and wastes include some volatile components that transfer to the atmosphere before they can be degraded. Contaminants that have been successfully treated include diesel fuel and fuel oils, jet fuel, oily sludge, wood-preserving wastes such as pentachlorophenol (PCP), polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and creosote, and certain pesticides. Inorganic contaminants will not be biodegraded, but they may be immobilized.

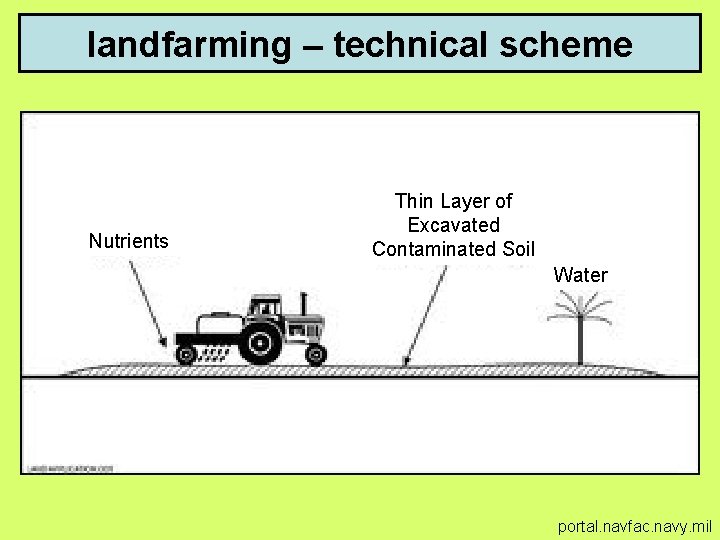

landfarming – technical scheme Nutrients Thin Layer of Excavated Contaminated Soil Water portal. navfac. navy. mil

landfarming http: //www. lra. co. uk/news/spreading-waste-to-land-6. html

composting – definitions Composting, often described as nature’s way of recycling, is the biological process of breaking up of organic waste such as food waste, manure, leaves, grass trimmings, paper, worms, and coffee grounds, etc. , into an extremely useful humus-like substance by various micro-organisms including bacteria, fungi and actinomycetes in the presence of oxygen. http: //www. benefits-of-recycling. com/definitionofcomposting. html Composting is the aerobic bio-degradation of organic materials under controlled conditions, resulting in a rich humus -like material (compost). http: //www. compostguy. com/composting-defined

composting – definitions Composting means the autothermic and thermophilic biological decomposition of separately collected biowaste in the presence of oxygen and under controlled conditions by the action of micro- and macro-organisms in order to produce compost. (Working document on Biological Treatment of Biowaste elaborated by working group of DG ENV. A. 2 (European Commission)). Municipal composting means a system of collection and concentration of plant residues and of maintenance of green areas and parks on the territory of the municipality, their treatment and subsequent processing/treatment into green compost. (ACT no. 185/2001 Coll. (Czech Republic))

compost Compost is a rich source of organic matter. Soil organic matter plays an important role in sustaining soil fertility, and hence in sustainable agricultural production. In addition to being a source of plant nutrient, it improves the physico-chemical and biological properties of the soil. As a result of these improvements, the soil: (i) becomes more resistant to stresses such as drought, diseases and toxicity; (ii) helps the crop in improved uptake of plant nutrients; and (iii) possesses an active nutrient cycling capacity because of vigorous microbial activity.

aerobic composting process The aerobic composting process starts with the formation of the pile. In many cases, the temperature rises rapidly to 70 -80 °C within the first couple of days. First, mesophilic organisms (optimum growth temperature range = 20 -45 °C) multiply rapidly on the readily available sugars and amino acids. They generate heat by their own metabolism and raise the temperature to a point where their own activities become suppressed. Then a few thermophilic fungi and several thermophilic bacteria (optimum growth temperature range = 50 -70 °C or more) continue the process, raising the temperature of the material to 65 °C or higher. This peak heating phase is important for the quality of the compost as the heat kills pathogens and weed seeds. The active composting stage is followed by a curing stage, and the pile temperature decreases gradually. The start of this phase is identified when turning no longer reheats the pile. At this stage, another group of thermophilic fungi starts to grow. These fungi bring about a major phase of decomposition of plant cell-wall materials such as cellulose and hemi-cellulose. Curing of the compost provides a safety net against the risks of using immature compost such as nitrogen (N) hunger, O deficiency, and toxic effects of organic acids on plants.

aerobic composting process (cont. ) Eventually, the temperature declines to ambient temperature. By the time composting is completed, the pile becomes more uniform and less active biologically although mesophilic organisms recolonize the compost. The material becomes dark brown to black in colour. The particles reduce in size and become consistent and soil-like in texture. In the process, the amount of humus increases, the ratio of carbon to nitrogen (C: N) decreases, p. H neutralizes, and the exchange capacity of the material increases.

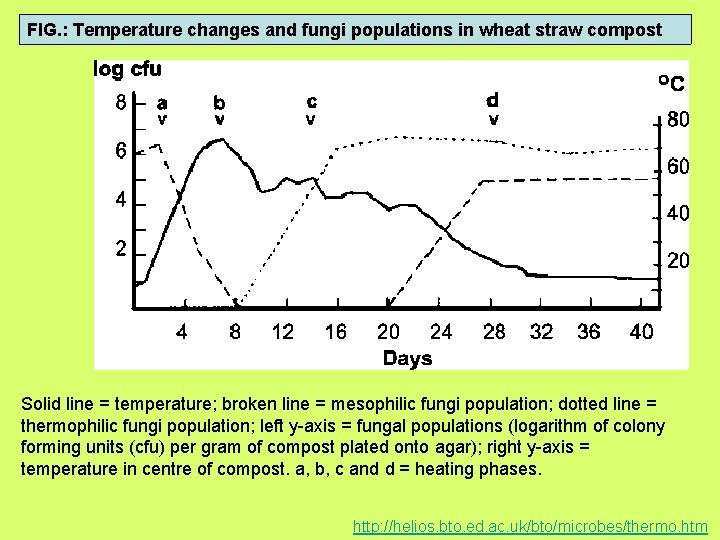

FIG. : Temperature changes and fungi populations in wheat straw compost Solid line = temperature; broken line = mesophilic fungi population; dotted line = thermophilic fungi population; left y-axis = fungal populations (logarithm of colony forming units (cfu) per gram of compost plated onto agar); right y-axis = temperature in centre of compost. a, b, c and d = heating phases. http: //helios. bto. ed. ac. uk/bto/microbes/thermo. htm

Factors affecting aerobic composting Aeration Large amounts of O are required, particularly at the initial stage. Where the supply of O is not sufficient, the growth of aerobic micro-organisms is limited, resulting in slower decomposition. Moreover, aeration removes excessive heat, water vapour and other gases trapped in the pile. Heat removal is particularly important in warm climates as the risk of overheating and fire is higher. Good aeration is indispensable for efficient composting. It may be achieved by controlling the physical quality of the materials (particle size and moisture content), pile size and ventilation and by ensuring adequate frequency of turning. Moisture is necessary to support the metabolic activity of the micro-organisms. Composting materials should maintain a moisture content of 40 -65 percent. Where the pile is too dry, composting occurs more slowly, while a moisture content in excess of 65 percent develops anaerobic conditions. In practice, it is advisable to start the pile with a moisture content of 50 -60 percent, finishing at about 30 percent.

Factors affecting aerobic composting Nutrients Micro-organisms require C, N, phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) as the primary nutrients. Of particular importance is the C: N ratio of raw materials. The optimal C: N ratio of raw materials is between 25: 1 and 30: 1 although ratios between 20: 1 and 40: 1 are also acceptable. Where the ratio is higher than 40: 1, the growth of microorganisms is limited, resulting in a longer composting time. A C: N ratio of less than 20: 1 leads to underutilization Temperature The process of composting involves two temperature ranges: mesophilic and thermophilic. While the ideal temperature for the initial composting stage is 20 -45 °C, at subsequent stages with thermophilic organisms taking over, a temperature range of 50 -70 °C may be ideal. High temperatures characterize the aerobic composting process and serve as signs of vigorous microbial activities. Pathogens are normally destroyed at 55 °C and above, while the critical point for elimination of weed seeds is 62 °C. Turnings and aeration can be used to regulate temperature. http: //www. fao. org

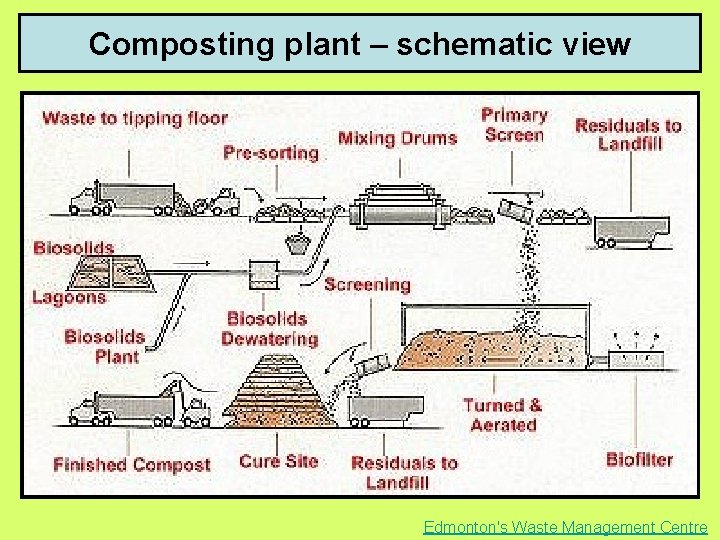

Composting plant – schematic view Edmonton's Waste Management Centre

Composting plant backtalk. tumblr. com

anaerobic digestion – definitions Anaerobic digestion is a biological process making it possible to degrade organic matter by producing biogas which is a renewable energy source and a sludge used as fertilizer. The bacteria which carry out these reactions exist in natural state in the liquid manure and the anaerobic ecosystems; it is not necessary to add more, they develop naturally in a medium without oxygen. (http: //www. biogas-renewable-energy. info) Anaerobic digestion is one of the most commonly used method for treating organic sludges generally resulting from the biological treatment of wastewaters through activated sludge processes. Under this process the organic sludge is treated in the absence of oxygen to reduce both the quantity and odor of sludges by breaking down the organic matter. The resultant sludge is rich in nutrients and organic matter which can improve the soil conditions if applied as soil supplement. (http: //www. trivenigroup. com/water/anaerobic-digester. html)

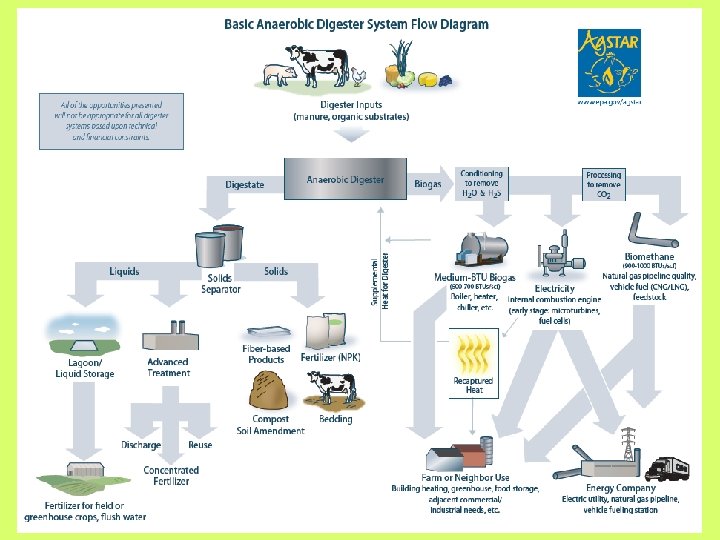

principles of anaerobic digestion Anaerobic digestion is the process by which organic materials in an enclosed vessel are broken down by micro-organisms, in the absence of oxygen. Anaerobic digestion produces biogas (consisting primarily of methane and carbon dioxide). Anaerobic digestion systems are also often referred to as "biogas systems. " Depending on the system design, biogas can be combusted to run a generator producing electricity and heat (called a co-generation system), burned as a fuel in a boiler or furnace, or cleaned and used as a natural gas replacement. The anaerobic digestion process also produces a liquid effluent (called digestate) that contains all the water, all the minerals and approximately half of the carbon from the incoming materials. http: //www. omafra. gov. on. ca

types of anaerobic digestion systems There are two general AD system configurations - completely mixed and plug flow. Completely Mixed Completely mixed systems consist of a large tank where fresh material is mixed with partially digested material. These systems are suitable for manure or other agri-food inputs with lower dry matter content (4%– 12%). Material with higher dry matter content will work in completely mixed systems by recirculating the liquid effluent. Plug Flow Plug flow systems typically consist of long channels in which the manure and other inputs move along as a plug. These systems are suitable for thicker materials such as liquid manure with 11%– 13% dry matter or higher.

anaerobic digestion - temperature ranges thermophylic (50°C– 60°C) The micro-organisms rapidly break down organic matter and produce large volumes of biogas. The quick breakdown means that the digester volume can be smaller than in other systems (average retention times in the range of 3– 5 days). Greater insulation is necessary to maintain the optimum temperature range, and more energy will be consumed in heating the system. These systems may be more sensitive to nitrogen levels in the incoming materials and to temperature variations, they are more effective in pathogen removal. Larger, centralized systems will typically run at thermophylic temperatures. mesophylic (35°C– 40°C) Longer treatment time is required (at least 15– 20 days or more) to break down organic matter. In general, these systems are reported to be more robust when considering temperature upsets. Small and mid-sized systems will typically operate in this temperature range. psychrophylic (15°C– 25°C) These systems are very stable and easy to manage, however, longer retention times are required to achieve equivalent gas production and pathogen removal.

challenges of anaerobic digestion Although the fundamentals of anaerobic digestion systems are very simple, the operation and control can be complex. Management considerations include: - mixing primarily fresh organic material (<1 week old) so that optimum organic matter is available for digestion - maintaining a narrow temperature range suitable for digestion - completing proper physical design of the system to eliminate plugging, crusting or foaming problems - installing and managing an interrelated group of systems to safely handle heating of the tank, material flow, hydrogen sulphide reduction, methane transfer, heat production, electrical production

questions to exam test - principle of landfarming - principle of composting - composting plant and its operation - principle of anaerobic digestion - anaerobic digestion plant and its operation

- Slides: 23